Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Trade Openness and Renewable Energy Consumption

2.2. The Other Determinants of Renewable Energy Consumption

3. Methods and Data

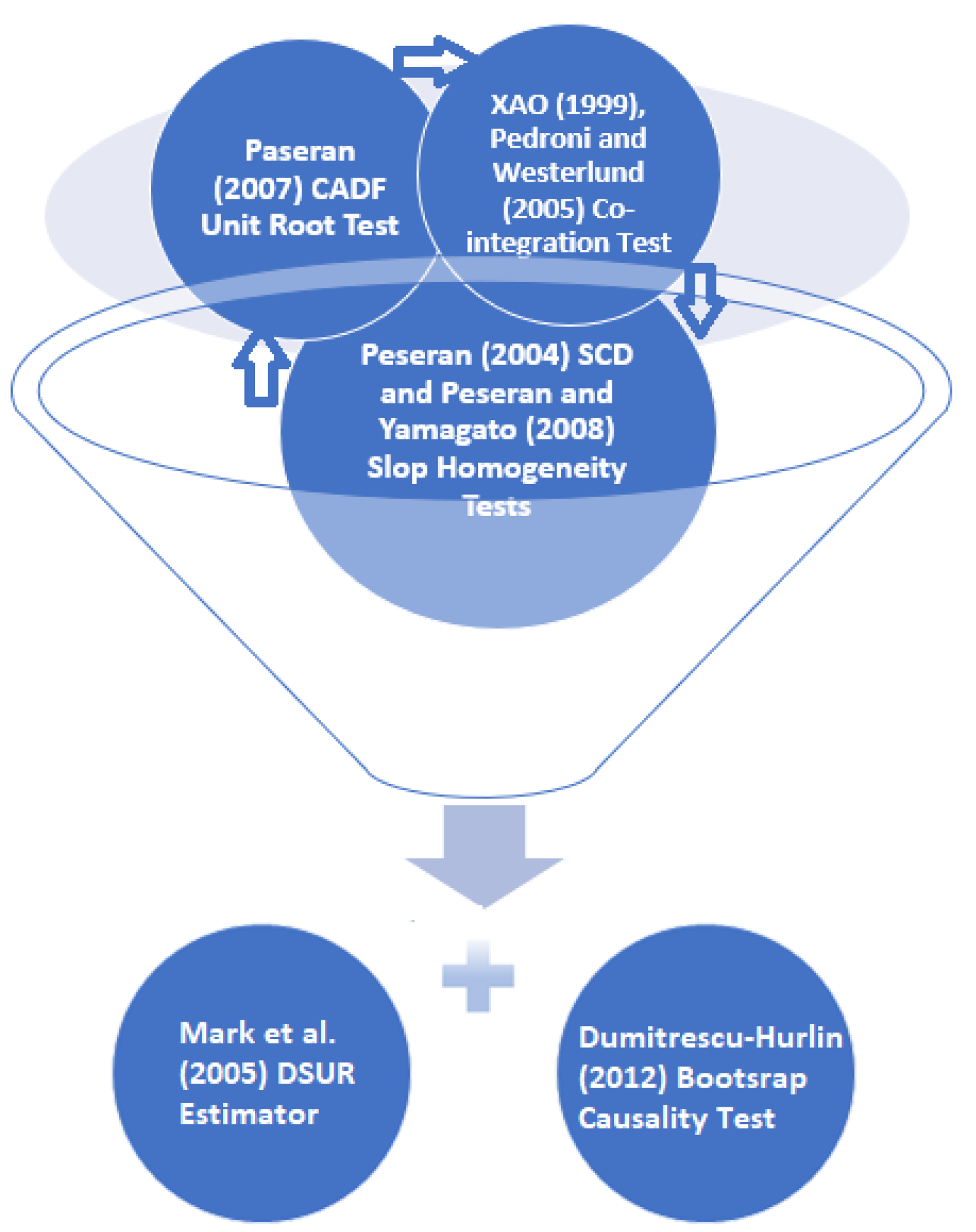

3.1. Methodological Famework

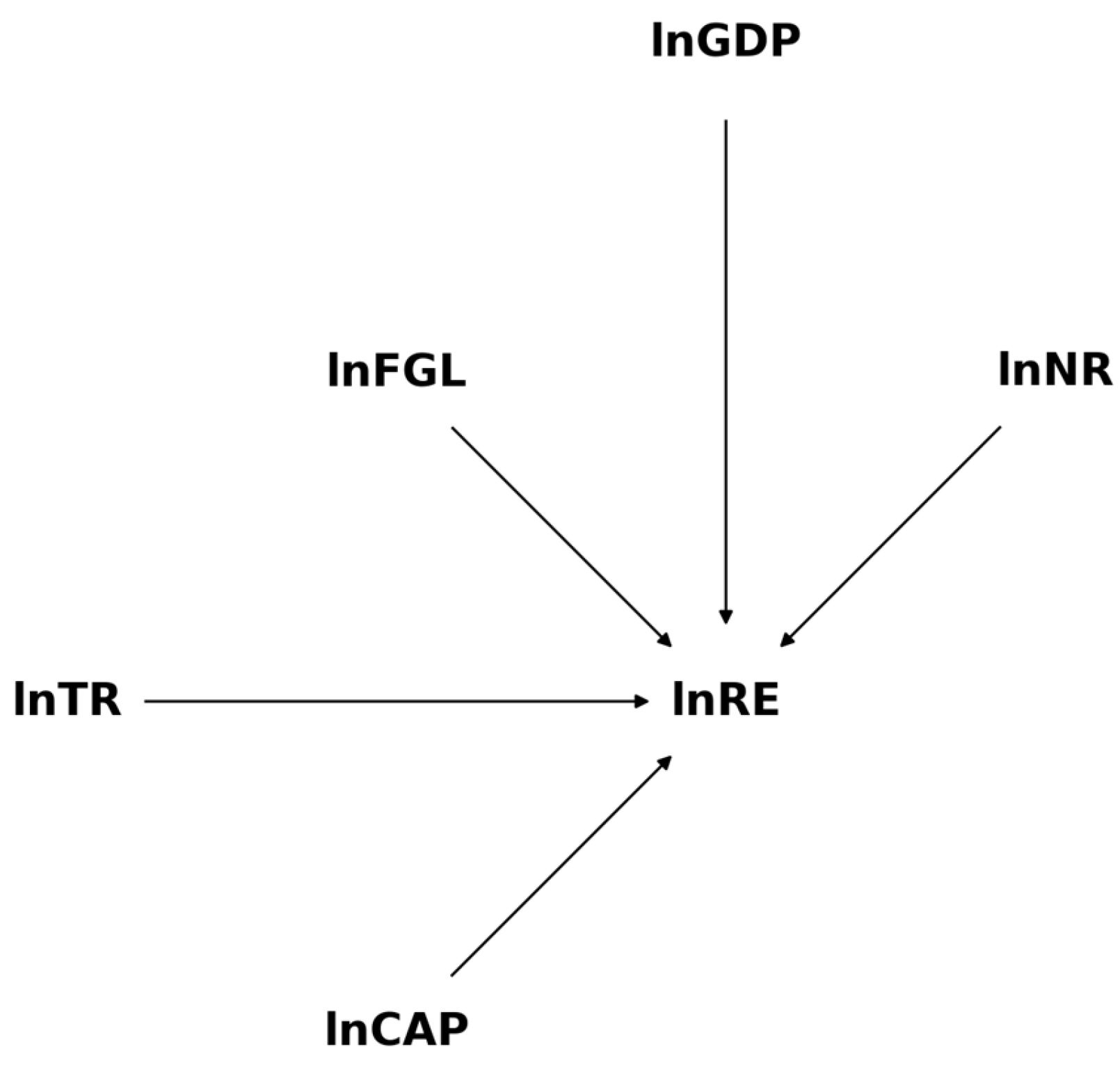

3.2. Empirical Modeling and Data

4. Results

4.1. Summary Statistics

4.2. CSD, Slope-Homogeneity and Unit Root Analyses

4.3. Cointegration Analysis

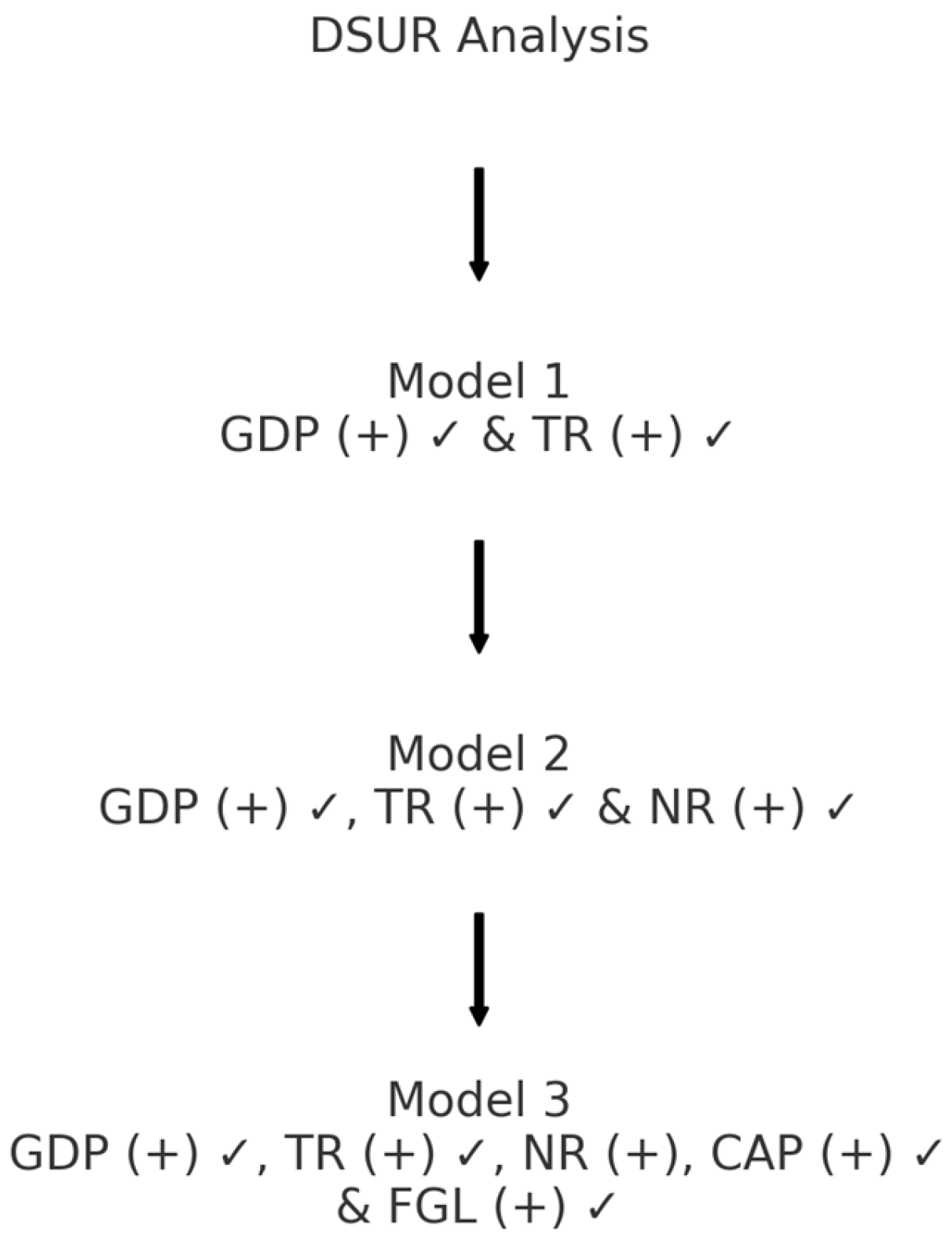

4.4. Long-Run Estimates

4.5. Bootstrap Causality Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Recommendations

6.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Guidelines

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMG | Average Marginal Gains |

| CADF | Cross-Sectionally Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| CCEMG | Common Correlated Effects Mean Group |

| CSD | Cross-Sectional Dependence |

| DOLS | Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares |

| FMOLS | Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| LSDVC | Least Squares Dummy Variable |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| PMG | Pooled Mean Group |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SUR | Seemingly Unrelated Regression |

References

- Mishra, M.; Desul, S.; Santos, C.A.G.; Mishra, S.K.; Kamal, A.H.M.; Goswami, S.; Kalumba, A.M.; Biswal, R.; Silva, R.M. da; Santos, C.A.C.D.; et al. A Bibliometric Analysis of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Review of Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Environ., Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. Sustainable Development: Meaning, History, Principles, Pillars, and Implications for Human Action: Literature Review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueres, C.; Quéré, C.L.; Mahindra, A.; Bäte, O.; Whiteman, G.; Peters, G.; Guan, D. Emissions Are Still Rising: Ramp up the Cuts. Nature 2018, 564, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Q.; Viktor, P.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Ali, B.M.; Algburi, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Al-Jiboory, A.K.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. The Renewable Energy Role in the Global Energy Transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, N.; Haščič, I.; Popp, D. Renewable Energy Policies and Technological Innovation: Evidence Based on Patent Counts. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2009, 45, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah, J.; Yao, X.; Tachega, M.A.; Hayford, I.S.; Opoku-Mensah, E. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth: New Evidence from Ghana. Energy 2022, 248, 123559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.H.; Tran, Q.; Tran, T. Economic Growth, Renewable Energy and Financial Development in the CPTPP Countries. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.M.; Murad, M.W. The Impacts of Economic Growth, Trade Openness and Technological Progress on Renewable Energy Use in Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development Countries. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzar, U. Political Economy of Renewable Energy: Does Institutional Quality Make a Difference in Renewable Energy Consumption? Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Topcu, B.A.; Sarıgül, S.S.; Vo, X.V. The Effect of Financial Development on Renewable Energy Demand: The Case of Developing Countries. Renew Energ 2021, 178, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Padhan, H.; Yan, C. Welfare Gains from International Trade and Renewable Energy Demand: Evidence from the OECD Countries. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, P.X.; Xuan, V.N.; Thu, N.T.P. Determinants of the Renewable Energy Consumption: The Case of Asian Countries. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Does Financial Globalization Promote Renewable Energy Investment? Empirical Insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 101366–101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Zakari, A.; Youn, I.J.; Tawiah, V. The Impact of Natural Resources on Renewable Energy Consumption. Resour. Polic. 2023, 83, 103692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Muniba; Kirikkaleli, D. Modeling the Dynamic Links among Natural Resources, Economic Globalization, Disaggregated Energy Consumption, and Environmental Quality: Fresh Evidence from GCC Economies. Resour. Polic. 2021, 73, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A. Does Trade Liberalization Increase National Energy Use? Econ. Lett. 2006, 92, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. NBER Working Paper Series 1991, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Baye, R.S.; Olper, A.; Ahenkan, A.; Musah-Surugu, I.J.; Anuga, S.W.; Darkwah, S. Renewable Energy Consumption in Africa: Evidence from a Bias Corrected Dynamic Panel. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Omoju, O.E.; Okonkwo, J.U. Factors Influencing Renewable Electricity Consumption in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Leung, G.C.K. The Relationship between Energy Prices, Economic Growth and Renewable Energy Consumption: Evidence from Europe. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1712–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, R.A.; Rafiq, S. Why Do Some Emerging Economies Proactively Accelerate the Adoption of Renewable Energy? Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Samreth, S. Corruption and Natural Resource Rents: Evidence from Quantile Regression. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 24, 1490–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Shahbaz, M.; Kautish, P.; Vo, X.V. Analyzing the Impact of Export Diversification and Technological Innovation on Renewable Energy Consumption: Evidences from BRICS Nations. Renew Energ 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, B.; Danish; Temiz, M. An Empirical Investigation between Renewable Energy Consumption, Globalization and Human Capital: A Dynamic Auto-Regressive Distributive Lag Simulation. Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Niroomand, F. Openness and Economic Growth: An Empirical Investigation. Appl. Econ. Lett. 1999, 6, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwik, B.; Topcu, B.A.; Doğan, M. The Impact of Nuclear Energy Consumption, Green Technological Innovation, and Trade Openness on the Sustainable Environment in the USA. Energies 2024, 17, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebli, M.B.; Youssef, S.B. Output, Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy Consumption and International Trade: Evidence from a Panel of 69 Countries. Renewable Energy 2015, 83, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F. Production of Clean Energy from Cyanobacterial Biochemical Products. Strat. Plan. Energy Environ. 2016, 36, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marhubi, F. Do Natural Resource Rents Reduce Labour Shares? Evidence from Panel Data. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 1754–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinwari, R.; Yangjie, W.; Payab, A.H.; Kubiczek, J.; Dördüncü, H. What Drives Investment in Renewable Energy Resources? Evaluating the Role of Natural Resources Volatility and Economic Performance for China. Resour. Polic. 2022, 77, 102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awijen, H.; Belaïd, F.; Zaied, Y.B.; Hussain, N.; Lahouel, B.B. Renewable Energy Deployment in the MENA Region: Does Innovation Matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F.; Elsayed, A.H.; Omri, A. Key Drivers of Renewable Energy Deployment in the MENA Region: Empirical Evidence Using Panel Quantile Regression. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2021, 57, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Irfan, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Vo, X.V. Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy Consumption in Bangladesh: The Relative Influencing Profiles of Economic Factors, Urbanization, Physical Infrastructure and Institutional Quality. Renew. Energy 2022, 184, 1130–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Sultana, N. Impacts of Institutional Quality, Economic Growth, and Exports on Renewable Energy: Emerging Countries Perspective. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafindadi, A.A.; Mika’Ilu, A.S. Sustainable Energy Consumption and Capital Formation: Empirical Evidence from the Developed Financial Market of the United Kingdom. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 35, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Rahman, Z.U.; Jóźwik, B.; Doğan, M. Determining the Environmental Effect of Chinese FDI on the Belt and Road Countries CO2 Emissions: An EKC-Based Assessment in the Context of Pollution Haven and Halo Hypotheses. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Lahiani, A.; Abosedra, S.; Hammoudeh, S. The Role of Globalization in Energy Consumption: A Quantile Cointegrating Regression Approach. Energy Econ. 2018, 71, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, S.S.; Alkawfi, M.M.; Uğural, S.; Akadiri, A.C. Towards Achieving Environmental Sustainability Target in Italy. The Role of Energy, Real Income and Globalization. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General Diagnostic Tests for Cross Section Dependence in Panels. SSRN Electron. J. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Yamagata, T. Testing Slope Homogeneity in Large Panels. J. Econ. 2008, 142, 50–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Khalid, K.; Mehdi, M.A. What Determines Environmental Deficit in Asia? Embossing the Role of Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy Utilization. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-section Dependence. J Appl Econ 2007, 22, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data. J. Econ. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. PANEL COINTEGRATION: ASYMPTOTIC AND FINITE SAMPLE PROPERTIES OF POOLED TIME SERIES TESTS WITH AN APPLICATION TO THE PPP HYPOTHESIS. Econ. Theory 2004, 20, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J.; Edgerton, D.L. A Panel Bootstrap Cointegration Test. Econ Lett 2007, 97, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. New Simple Tests for Panel Cointegration. Econ. Rev. 2005, 24, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Real Exchange Rates and Real Interest Differentials for Sectoral Data: A Dynamic SUR Approach. Econ. Lett. 2007, 97, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, N.C.; Ogaki, M.; Sul, D. Dynamic Seemingly Unrelated Cointegrating Regressions. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 797–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.-I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger Non-Causality in Heterogeneous Panels. Econ Model 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish; Baloch, M. A.; Mahmood, N.; Zhang, J.W. Effect of Natural Resources, Renewable Energy and Economic Development on CO2 Emissions in BRICS Countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 678, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bui, Q.; Zhang, B. The Relationship between Biomass Energy Consumption and Human Development: Empirical Evidence from BRICS Countries. Energy 2020, 194, 116906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y.; Sasmaz, M.U.; Ozkaya, M.H. Impact of Trade and Financial Globalization on Renewable Energy in EU Transition Economies: A Bootstrap Panel Granger Causality Test. Energies 2020, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, G. Analyzing the Impacts of Economic Growth, Pollution, Technological Innovation and Trade on Renewable Energy Production in Selected Latin American Countries. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Malik, M.Y.; Latif, K.; Jiao, Z. Heterogeneous Effect of Eco-Innovation and Human Capital on Renewable & Non-Renewable Energy Consumption: Disaggregate Analysis for G-7 Countries. Energy 2020, 209, 118405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadov, A.K.; Borg, C. van der Do Natural Resources Impede Renewable Energy Production in the EU? A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Energy Polic. 2019, 126, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.A.; Inekwe, J.; Ivanovski, K.; Smyth, R. The Environmental Kuznets Curve in the OECD: 1870-2014. Energy Economics 2018, 75, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulucak, R.; Danish; Ozcan, B. Relationship between Energy Consumption and Environmental Sustainability in OECD Countries: The Role of Natural Resources Rents. Resour. Polic. 2020, 69, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekun, F.V.; Alola, A.A.; Sarkodie, S.A. Toward a Sustainable Environment: Nexus between CO2 Emissions, Resource Rent, Renewable and Nonrenewable Energy in 16-EU Countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Renewable Energy Consumption and Income in Emerging Economies. Energy Polic. 2009, 37, 4021–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Nguyen, D.K. On the Determinants of Renewable Energy Consumption: International Evidence. Energy 2014, 72, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, E.; Altinoz, B.; Aslan, A. Global Evidence from the Link between Economic Growth, Natural Resources, Energy Consumption, and Gross Capital Formation. Resour. Polic. 2020, 66, 101622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, F. Renewable and Non-Renewable Categories of Energy Consumption and Trade: Do the Development Degree and the Industrialization Degree Matter? Energy 2019, 173, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, H.; Padhang, P.C.; Tiwari, A.K.; Ahmed, R.; Hammoudeh, S. Renewable Energy Consumption and Robust Globalization(s) in OECD Countries: Do Oil, Carbon Emissions and Economic Activity Matter? Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 32, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, H.H.; Smyth, R. CO2 Emissions, Electricity Consumption and Output in ASEAN. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1858–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Khan, A.; Zhou, K. The Impact of Natural Resource Depletion on Energy Use and CO2 Emission in Belt & Road Initiative Countries: A Cross-Country Analysis. Energy 2020, 199, 117409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T. Resource Dependence, Economic Performance, and Political Stability. J. Confl. Resolut. 2005, 49, 451–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Do Urbanization and Industrialization Affect Energy Intensity in Developing Countries? Energy Econ. 2013, 37, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, N.P.; Schinckus, C.; Thanh, S.D. The Natural Resources Rents: Is Economic Complexity a Solution for Resource Curse? Resour. Polic. 2020, 69, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damette, O.; Delacote, P.; Lo, G.D. Households Energy Consumption and Transition toward Cleaner Energy Sources. Energy Polic. 2018, 113, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Jebli, M.B.; Youssef, S.B. Renewable and Fossil Energy, Terrorism, Economic Growth, and Trade: Evidence from France. Renew. Energy 2019, 139, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Apergis, N.; Ummalla, M. Financing Clean Energy Projects through Domestic and Foreign Capital: The Role of Political Cooperation among the EU, the G20 and OECD Countries. Energy Econ. 2017, 61, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koengkan, M.; Poveda, Y.E.; Fuinhas, J.A. Globalisation as a Motor of Renewable Energy Development in Latin America Countries. GeoJournal 2019, 85, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, S.P.; Yalçiner, K.; Bekun, F.V. Assessing the Environmental Sustainability Corridor: Linking Natural Resources, Renewable Energy, Human Capital, and Ecological Footprint in BRICS. Resour. Polic. 2021, 70, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish; Ulucak, R. ; Khan, S.U.-D. Determinants of the Ecological Footprint: Role of Renewable Energy, Natural Resources, and Urbanization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riti, J.S.; Riti, M.-K.J.; Oji-Okoro, I. Renewable Energy Consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): Implications on Economic and Environmental Sustainability. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cauntries/Years | 1990 | 2000 | 2018 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| China | 0.02 | 1027 | 157 | 0.71 | 2770 | 822 | 143.50 | 13493 | 5121 |

| United States | 13.72 | 9811 | 1378 | 16.50 | 13754 | 3065 | 103.80 | 19479 | 5520 |

| Germany | 0.34 | 2342 | 825 | 3.23 | 2835 | 1521 | 47.33 | 3562 | 3240 |

| United Kingdom | 0.14 | 1801 | 345 | 1.10 | 2310 | 1053 | 23.90 | 3139 | 1834 |

| Sweden | 0.44 | 295 | 136 | 1.03 | 364 | 261 | 6.60 | 539 | 474 |

| Brazil | 0.87 | 917 | 109 | 1.80 | 1186 | 230 | 23.64 | 1797 | 517 |

| India | 0.02 | 465 | 58 | 0.74 | 800 | 194 | 27.50 | 2588 | 1132 |

| Japan | 2.57 | 3509 | 641 | 3.74 | 3986 | 953 | 23.40 | 4580 | 1718 |

| Spain | 0.13 | 737 | 212 | 1.41 | 971 | 528 | 16.00 | 1297 | 871 |

| Italy | 0.74 | 1559 | 511 | 1.51 | 1842 | 842 | 14.93 | 1908 | 1158 |

| France | 0.43 | 1661 | 514 | 0.70 | 2046 | 985 | 10.60 | 2569 | 1671 |

| Canada | 0.90 | 877 | 369 | 2.10 | 1047 | 784 | 10.30 | 1664 | 1106 |

| Australia | 0.17 | 630 | 133 | 0.24 | 872 | 274 | 7.21 | 1460 | 643 |

| Turkiye | 0.02 | 288 | 68 | 0.10 | 413 | 181 | 8.53 | 988 | 500 |

| Mexico | 1.16 | 626 | 174 | 1.44 | 876 | 463 | 4.83 | 1255 | 961 |

| Total | 20.67 | 26545 | 5630 | 36.35 | 36072 | 12156 | 466.07 | 60318 | 26466 |

| World | 27.30 | 35870 | 12330 | 49.32 | 48220 | 22820 | 561.30 | 82510 | 47360 |

| EU | 4.24 | 7973 | 3194 | 14.10 | 9961 | 6121 | 159.60 | 12427 | 11582 |

| Variables | Descriptions | Source | Expected sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| REN | Renewable Energy Consumption(million tons of oil equivalent) [57] | BP | |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product (constant 2010 US$) [58] | WB | (+) [59] |

| TR | Trade Openness (% of GDP) [53] | WB | (+) (–) [60] |

| NR | Natural Resource Rents (% of GDP) [30] | WB | (+) [30] |

| CAP | Gross Capital Formation (% of GDP) [61] | WB | (+) [62] |

| FGL | KOF Index of Financial Globalization [52] | KOF Swiss Economic Institute | (+) (–) [63] |

| Statistics/Variables | lnREN | lnGDP | lnTR | lnNR | lnCAP | lnFGL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.845 | 28.215 | 3.775 | -0.713 | 3.126 | 4.140 |

| Median | 0.916 | 28.191 | 3.868 | -0.457 | 3.103 | 4.265 |

| Std. dev. | 1.741 | 0.891 | 0.420 | 1.794 | 0.215 | 0.342 |

| Min. | -4.175 | 26.458 | 2.718 | -4.520 | 2.683 | 2.411 |

| Max. | 4.966 | 30.516 | 4.527 | 2.272 | 3.842 | 4.519 |

| Skewness | -0.390 | 0.476 | -0.542 | -0.291 | 1.080 | -1.721 |

| Kurtosis | 3.073 | 3.025 | 2.580 | 1.828 | 4.739 | 7.007 |

| Obs. | 435 | 435 | 435 | 435 | 435 | 435 |

| Correlation matrix | ||||||

| lnREN | 1.000 | |||||

| lnGDP | 0.688 | 1.000 | ||||

| lnTR | 0.100 | -0.318 | 1.000 | |||

| lnNR | -0.073 | -0.220 | -0.047 | 1.000 | ||

| lnCAP | -0.095 | 0.079 | -0.018 | 0.056 | 1.000 | |

| lnFGL | 0.338 | 0.169 | 0.586 | -0.366 | -0.156 | 1.000 |

| Variables | CD-test | P- Value | Corr | Abs (corr) | CADF test statistic | |

| L | Δ | |||||

| lnREN | 51.91*** | 0.000 | 0.941 | 0.941 | 0.657 | -3.066*** |

| lnGDP | 52.65*** | 0.000 | 0.954 | 0.954 | -1.207 | -3.096*** |

| lnTR | 39.66*** | 0.000 | 0.719 | 0.720 | -1.106 | -1.930** |

| lnNR | 25.29*** | 0.000 | 0.458 | 0.488 | -0.332 | -9.495*** |

| lnCAP | 4.17*** | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.313 | -0.391 | -7.072*** |

| lnFGL | 40.24*** | 0.000 | 0.729 | 0.732 | -0.591 | -4.382*** |

| Tests | Statistics | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Δ | 20.355*** | 0.000 |

| Δ-adjusted | 23.370*** | 0.000 |

| Cointegration tests | Statistic | P- Value |

|---|---|---|

| Pedroni | ||

| Modified Phillips&Perron t | 4.390*** | 0.000 |

| Phillips&Perron t | 1.120 | 0.131 |

| Augmented Dickey&Fuller t | 2.008** | 0.022 |

| Kao | ||

| Modified Dickey&Fuller t | -0.486 | 0.313 |

| Dickey Fuller t | -1.799** | 0.035 |

| Augmented Dickey&Fuller t | -2.033** | 0.021 |

| Unadjusted modified Dickey&Fuller t | 0.547 | 0.291 |

| Unadjusted Dickey&Fuller t | -1.163 | 0.122 |

| Westerlund | ||

| Variance-Ratio | 2.763*** | 0.002 |

| Regressors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| lnGDP | 0.049*** (03.12) |

0.064*** (3.92) |

0.048*** (2.86) |

0.069*** (4.04) |

| lnTR | 0.049** (2.00) |

0.064** (2.57) |

0.050** (2.03) |

0.143*** (4.53) |

| lnNR | 0.015*** (3.13) |

0.013*** (2.69) |

0.005 (0.99) |

|

| lnCAP | 0.135*** (3.28) |

0.091** (2.19) |

||

| lnFGL | -0.173*** (-4.60) |

|||

| Constant | -1.414*** (-2.82) |

-1.871***(-3.62) | -1.801*** (-3.52) |

-1.889*** (-3.78) |

| R2 | 0.988 | 0.989 | 0.989 | 0.989 |

| χ2-statistic | 37133.71 | 38011.72 | 38993.57 | 40975.63 |

| Prob | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| RMSE | 0.178 | 0.176 | 0.174 | 0.170 |

| Countries | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Observation | 420 | 420 | 420 | 420 |

| Hypotheses | W-Stat. | Zbar-Stat. | p-value | Causality |

| lnGDP ≠> lnREN | 4.472 | 9.510 | 0.026** | Unidirectional |

| lnREN ≠> lnGDP | 2.160 | 3.178 | 0.576 | |

| lnTR ≠> lnREN | 2.126 | 3.083 | 0.068* | Unidirectional |

| lnREN ≠> lnTR | 2.679 | 4.600 | 0.350 | |

| lnNR ≠> lnREN | 2.140 | 3.124 | 0.024** | Unidirectional |

| lnREN ≠> lnNR | 2.614 | 4.422 | 0.198 | |

| lnCAP ≠> lnREN | 2.118 | 3.062 | 0.024** | Unidirectional |

| lnREN ≠> lnCAP | 2.650 | 4.519 | 0.164 | |

| lnFGL ≠> lnREN | 5.039 | 11.062 | 0.000*** | Unidirectional |

| lnREN ≠> lnFGL | 1.322 | 0.882 | 0.842 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).