1. Role of Research Evidence in International Policy Frameworks on Ageing

Evidence-informed or evidence-based policy has long been recognised as an essential foundation for addressing ageing and longevity. The natural history of international action on ageing goes back more than forty years. It has been shaped by two international policy documents: the Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing, VIPAA [

1] and the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing, MIPAA [

2]. These two landmark documents were produced within the United Nations twenty years apart and consequently have different focuses of analysis and recommendations for policy action. While the VIPAA proposed policy action in 'areas of concern to ageing individuals’, the MIPAA prioritised developmental aspects of population and individual ageing.

Both plans highlight the importance of research evidence in policy on ageing. The VIPAA underscores the role of research and data collection in the formulation, evaluation and implementation of policies and programmes to address the impact of ageing on development and the needs of older people [

1] (para 84). It calls for an emphasis on "the continuum of research from the discovery of new knowledge to its vigorous and more rapid application and transfer of technological knowledge with due consideration of cultural and social diversity” [

1] (para 85). The MIPAA emphasises the importance of research and data collection and analysis in providing the essential evidence for effective ageing policies [

2]. Research and data collection and analysis for policy planning, monitoring and evaluation are key elements of

national implementation of the MIPAA. The exchange of researchers and research findings and the collection of data to support policy and programme development have been identified as priorities for

international cooperation on ageing. Both the VIPAA and the MIPAA contain the research priorities. In the VIPAA, these priorities are formulated as “basic and applied issues” of the “developmental and humanitarian aspects of ageing” [

1] (para 85). The research priorities of the MIPAA are included in its narratives and recommendations for action [

2].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has been a major contributor to the development and implementation of international policy frameworks on ageing. The WHO policy framework on active ageing identified several determinants of active ageing and called for “more research to clarify and specify the role of each determinant, as well as the interaction between determinants, in the active ageing process” [

3]. The WHO policy framework on active ageing also called on international agencies, countries and regions to develop a research agenda for active ageing.

The research component of another WHO policy framework, the WHO Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health, is outlined in Strategic Objective 5: "Improving measurement, monitoring and research for healthy ageing" [

4]. This objective emphasises building an evidence base for policies that are effective, equitable and cost-effective, while promoting research on age-related issues and strategies for healthy ageing across the life course. It also identifies basic research questions that are essential for policy development. To achieve strategic objective 5, the strategy outlines specific tasks: agreeing on metrics for measuring and monitoring healthy ageing, strengthening research capacities and synthesising evidence. For the first phase of implementation (2016-2020), two key objectives have been set: to implement five years of evidence-based action to maximise the functional capacity of all individuals, and to build the evidence and partnerships needed to support the Decade of Healthy Ageing (2020-2030). The UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2020-2030), a key initiative of the Strategy, promotes action in four areas: changing perceptions of ageing, promoting age-friendly communities, providing person-centred care and ensuring access to long-term care [

5]. Strengthening data, research and innovation is a key enabler for these efforts, supporting the evidence-based activities of the Decade.

The research components of the major international policy frameworks on ageing, such as the VIPAA, the MIPAA and the WHO’s policy documents on ageing, promote the central role of research evidence in the design, implementation and monitoring of international and national policies on ageing. Research evidence serves as a crucial foundation for shaping social policy and practice. However, research and policy processes often operate independently, resulting in the risk of opinion-based or conviction-driven approaches rather than evidence-based strategies for developing, implementing, and monitoring policy measures. Integrating evidence into policy remains a universal challenge for global and national actions on ageing. Achieving this integration requires strong partnerships among researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to identify and address research priorities relevant to policy needs.

To ensure that research evidence underpins policy action, it is essential to bridge the gap between the often siloed processes of research and policy. This requires reciprocal efforts from key stakeholders: academic researchers on the one hand, and policy experts in legislatures, governments, business and civil society on the other. Academic researchers should focus on aligning their work with policy priorities, translating research findings into actionable policy recommendations, and improving the overall quality, reliability and robustness of their research. For policy experts in different fields, the key challenge is to move away from opinion-based approaches to policy design and implementation and to replace them with evidence-based strategies. A research agenda on ageing and longevity can serve as a useful vehicle for achieving these tasks.

2. What Is Research Agenda? What Is Research Agenda for?

In its most straightforward formulation, the research agenda can be defined as a list of research priorities. A more sophisticated definition would refer to a structured plan or framework that outlines key areas of study, questions to be addressed, and priorities for future investigation in a particular field or topic.

An advanced research agenda can be seen as a roadmap for researchers, funding organisations, policy makers and other stakeholders to guide their efforts in exploring, understanding and solving specific problems or advancing knowledge.

There is little established and fixed structure to a research agenda. Its key elements may include: purpose and aims (outline the overall goal of the research, such as to increase understanding, solve a problem or innovate in a field); research questions or hypotheses (that the agenda seeks to address); priority areas (key issues or topics that require attention or exploration); methods; stakeholders (groups or individuals, e.g. older people, researchers, funders, policy makers, involved in or affected by the research); timelines and milestones; and impacts and implications (potential outcomes, benefits or societal impacts of the research).

The establishment of a research agenda serves to provide a comprehensive overview of a specific research domain and to delineate the intended future trajectory. A meticulously formulated research agenda aspires to ensure that research endeavors are methodical, consequential, and congruent with overarching societal or scientific objectives.

A research agenda plays a pivotal role in the field of scientific research, offering a framework that guides and integrates diverse scientific initiatives. By providing a clear direction, it enables researchers and research organizations to concentrate their efforts on the most challenging and impactful issues, facilitating the allocation of resources. The agenda serves as a guide for funding decisions, ensuring that resources are directed towards the most pressing needs. Additionally, it fosters collaboration by providing a shared vision that encourages the formation of interdisciplinary partnerships. In terms of practical applications, a research agenda helps to establish benchmarks and indicators, allowing for the measurement of progress and success.

A research agenda often serves as a foundational element for evidence-based policy, providing insights that inform the formulation and implementation of policies.

3. Bridging Research and Policy on Ageing and Longevity

To effectively address the complexities of population ageing and individual longevity, research agendas can play a pivotal role in bridging research and policy. They are intended to provide structured frameworks to prioritize key areas of study, identify knowledge gaps, and guide interdisciplinary efforts that inform evidence-based policymaking in countries at different stages of demographic transition. A frequently stated intention of research agendas on ageing is to inform and inspire policy responses to ageing and longevity. Another intention of research agendas, more practical and perhaps more realistic, is to bridge the gap between research and policy and to promote collaboration between key stakeholders in action on ageing, primarily researchers, policy-makers and policy experts in the legislative, governmental, business and civil society spheres.

Several organisations and research bodies have developed comprehensive research agendas to address the multiple challenges and opportunities of ageing and longevity. Some of these research agendas provide structured frameworks to guide studies and policy development aimed at improving the well-being of older people and promoting the resilience and development of ageing societies.

For general guidance, it is helpful to distinguish between the well-structured research agendas, which are usually provided as separate documents, and the lists of priorities and/or research questions identified in the conclusion of a review publication and referred to as research agendas. This article refers to both types of research agendas. It will also present some examples of global, regional and national agendas, as well as sectoral agendas, the former referring to agendas dedicated to a particular sector (area) of research and policy, e.g. transport and older people.

4. International Research Agendas on Ageing and Longevity

Historically, one of the first international research agendas on ageing was elaborated in 2001 by the National Research Council of the US National Academy of Sciences [

6]. The National Academies of the USA, through the National Research Council, convened a panel to explore the scientific opportunities for conducting policy-relevant comparative research on ageing. The main tasks of the Panel were to provide “recommendations for an international research agenda and for the types of data needed to implement that agenda in the context of rapid demographic change” [

6] (p. 2). The Panel on a Research Agenda and New Data for an Aging World was not tasked with recommending specific policies on ageing. Instead, its mandate was “to identify the types of data and research paradigms that would enable policymakers to make better-informed decisions” [

6] (p. 22).

The diverse findings of the Panel were presented in a comprehensive report entitled “Preparing for an Aging World. The Case for cross-National Research”, which was published in 2001 [

6]. The report focused on five domains of research: work and retirement, savings and wealth, family structure and intergenerational transfers, health and disability, and well-being. The respective report chapters include specific recommendations for each of the identified topics. Additionally, the panel formulated six major overarching recommendations, deemed critical for conducting effective cross-national research and generating data relevant to policymaking:

The development and use of multidisciplinary research designs are crucial to the production of data on aging populations that can best inform public policies.

Longitudinal research should be undertaken to disentangle and illuminate the complex interrelationships among work, health, economic status, and family structure.

National and international funding agencies should establish mechanisms that facilitate the harmonization (and in some cases standardization) of data collected in different countries.

Cross-national research, organized as a cooperative venture, should be emphasized as a powerful tool that can enhance the ability of policy makers to evaluate institutional and programmatic features of policy related to aging in light of international experience, and to assess more accurately the impact of potential modifications to existing programs.

Countries should aggressively pursue the consolidation of information from multiple sources to generate linked databases.

The scientific community, broadly construed, should have widespread and unconstrained access to the data obtained through the methods and activities recommended in this report.

Nearly twenty-five years later, the five research domains highlighted in the report continue to be central to national and international studies on ageing, while the six overarching recommendations remain both relevant and timely.

In 2002, the Research Agenda on Ageing for the Twenty-First Century (RAA-21) was elaborated through a collaborative initiative of the United Nations Programme on Ageing (UNPoA) and the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG) [

7]. It was developed through a series of expert consultations organized by UNPoA and IAGG between 1999 and 2000. In April 2002, the RAA-21 was endorsed by the Valencia Forum of Researchers and Practitioners on Ageing (IAGG, 2002) and subsequently presented at the Second World Assembly on Ageing in Madrid, Spain.

The United Nations General Assembly welcomed the RAA-21 through resolution 57/177 in 2002 [

8]. In 2005, it urged governments to utilize the Research Agenda as a framework for enhancing national capacity on ageing [

9]. That same year, during the Eighteenth Congress of IAGG, the UNPoA and IAGG convened an expert workshop in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to review and update the RAA-21. The updated version of the RAA-21 was published in 2007 [

7].

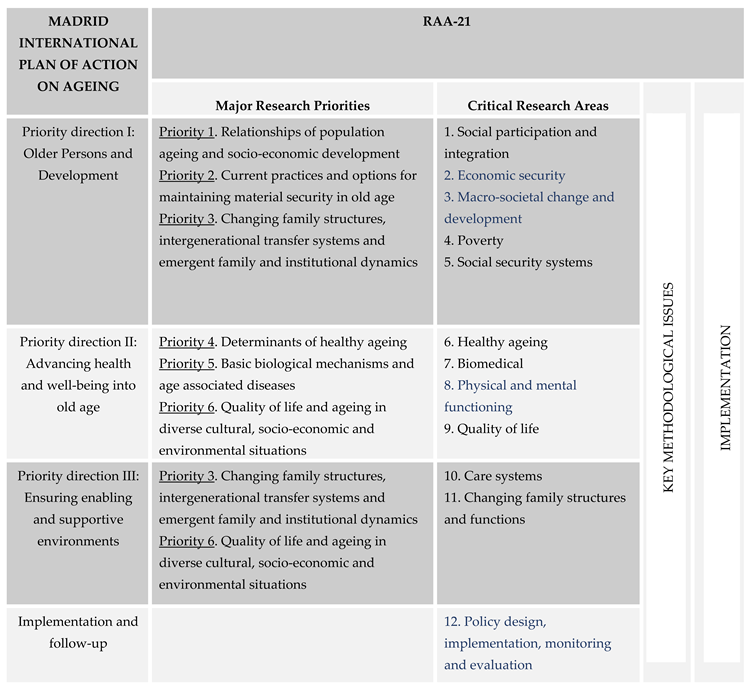

RAA-21 highlighted key priorities, critical research areas and key methodological issues related to ageing, with the aim of guiding public policy and scientific research to address the implications of global ageing.

The special feature of RAA-21 is that it is closely linked to the main international policy framework on ageing, the MIPAA. RAA-21 is specifically designed to support the implementation of the MIPAA and to inspire researchers to undertake studies in policy-related areas where findings can have practical and actionable applications for addressing ageing issues [

7]. The United Nations recognized RAA-21 as a vital tool in facilitating the implementation and monitoring of the policy actions outlined in the MIPAA [

9].

RAA-21 outlined six major priorities and twelve critical research areas, including specific topics for policy-focused research and data collection. These priorities and research areas are closely aligned with the priority directions of the MIPAA. Additionally, RAA-21 addresses key methodological considerations and provides proposals for implementation (

Table 1).

At the time of writing (early 2025), the most recent attempt to support and activate the development of research agendas on ageing and longevity to inform policy responses is the book “A Research Agenda for Ageing and Social Policy”, co-edited by the authors of this article [

10]. The book's expert contributors examined a wide range of relevant issues, culminating in the formulation of “An agenda for social policy-related research on ageing”. The agenda formulates 32 research questions grouped in eight areas:

Area 1: Population ageing and social welfare policies – the life-course perspective

Area 2: Combating ageism

Area 3: Strengthening the rights of older persons to reduce poverty and inequalities

Area 4: Establishing new types of working and learning in digitalized societies

Area 5: Transforming health, social and long-term care systems

Area 6: Enhancing social solidarity and intergenerational equity

Area 7: Designing age-friendly environments and communities

Area 8: Strengthening international policy action on ageing by involving all relevant stakeholders.

The main conceptual approach of the proposed agenda is an evolution of research and policy from a predominant focus on population ageing and individual late-life issues to research and policy on longevity. Such an evolution involves a shift (relocation) of demographic transitions and the life course to the centre of research and policy.

The RAA-21 is not the only research agenda that attempts to link the formulated research priorities and areas to the established international policy documents on ageing, such as the MIPAA in the case of the RAA-21. In 2024, a conceptual framework and agenda was proposed to address the action items of the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing in scientific research [

11]. This research agenda is based on the core concepts of near-environments (family and community), life courses and wellbeing. The authors call for addressing the knowledge gap in understanding the capacity of families to be supportive and of communities to be age-friendly, and propose four broad themes for further research and policy development, with corresponding research questions:

- 1.

Articulating beliefs about who should do what and how much in care arrangements at both societal and family levels.

- 7.

Developing more robust conceptualization of family wellbeing of families of older adults.

- 8.

Articulating beliefs about the extent to which communities should be held responsible for support of older residents.

- 9.

Developing a more robust conceptualization of community wellbeing.

5. Regional and National Research Agendas on Ageing

An example of a regional research agenda on ageing can be found in a recent publication of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine entitled “Developing an Agenda for Population Aging and Social Research in Low - and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs): Proceedings of a Workshop” [

12].

This comprehensive report presents the deliberations of an expert workshop convened to identify the most promising behavioural and social research directions and data priorities for studying health, ageing, and Alzheimer's disease and related dementias across the life course in LMICs. The discussion focused on three broad themes: inequality, family change and climate change, to better understand how inequality, changing family structures and environmental exposures affect health and well-being in older age in LMICs.

The workshop aimed to identify priorities for future research and data collection to strengthen the evidence base for policy-making. The report does not provide a structured research agenda, but outlines key challenges and perspectives for research on ageing in LMICs. It discusses the state of social and behavioural research in LMICs, its benefits, specificities and limitations, and the transferability and translation of research findings to other contexts in different countries.

Within the European Union, the European Commission (EC) supports research and innovation in various fields [

13], with particular emphasis on ageing and longevity within the Health Research Area. One of the key research areas in the Health Research Area is 'Human Development and Ageing', which includes several key research topics: biomarkers of ageing; developmental processes of long-lived organisms throughout the lifespan; the immune system in old age; developing a roadmap for ageing research in Europe; increasing the participation of older people in clinical trials; determinants of ageing and longevity, including environmental factors; and developing a consensus definition of frailty.

Over the past decade, the EU has supported numerous research and innovation programmes and projects addressing ageing-related issues, including the EU's major research and innovation funding programme Horizon 2020 [

14]; the FUTUREAGE project [

15]; the project "Mobilising the potential of active ageing in Europe" (MoPAct) [

16]; the project "Social innovation on active and healthy ageing for sustainable economic growth" (SIforAGE) [

17]; and the Joint Programming Initiative "More Years Better Lives" (JPI MYBL) [

18].

Within the JPI MYBL, the Strategic Research Agenda (SRA) was developed in 2014 “to help all participating countries, and other research funders to prioritise and design research activities related to demographic change” [

19]. The SRA establishes research and policy priorities across four domains of demographic impact on society: Quality of Life and Health; Economic and Social Production; Governance and Institutions; and Sustainability of Welfare in the EU. The SRA has highlighted priority research topics to be addressed in the short and medium term:

- 1.

Quality of life, wellbeing and health

- 10.

Learning for later life

- 11.

Social and economic production

- 12.

Participation

- 13.

Ageing and place

- 14.

A new labour market

- 15.

Integrating policy

- 16.

Inclusion and equity

- 17.

Welfare models

- 18.

Technology for living

- 19.

Research infrastructure.

The 1991 publication "Extending Life, Enhancing Life: A National Research Agenda on Aging" is another example of the deliberations of the US Academy of Sciences [

20]. The committee, convened by the National Academy's Institute of Medicine, was charged with identifying research “that would enhance the understanding of basic processes of aging and maximize function in older persons; to alert scientists to promising but neglected areas of research on aging; and to bring the importance of age-related research to the attention of government, academic institutions, industry, and the public” [

20] (p. vii). The agenda outlines 15 research priorities across five key research areas, focusing on understanding the fundamental processes of ageing and developing practical solutions to improve the quality of life for older adults (

Table 2).

Furthermore, and undeniably important, the report also identified areas where additional funding needs to be allocated to support the Research Agenda.

A Research Agenda for Aging in China in the 21st Century article addresses the health care challenges posed by China's rapidly ageing population. While it does not present a structured research agenda, it does outline research priorities to address the expected increase in the number of older adults [

21]. These priorities include:

- 1.

Collection of public health data

- 20.

Diet and food safety

- 21.

Physical exercise

- 22.

Pharmacological interventions in age-associated diseases

- 23.

Older people and geriatric care.

The Strategic Research Agenda for Ageing Well in South Australia [

22] has been developed to support the implementation of South Australia’s Plan for Ageing Well 2020-2025 [

23]. It is one of the few examples where research priorities have been specifically formulated to support a concrete

national policy document on ageing.

The purpose of the Strategic Research Agenda for Ageing Well in South Australia is to outline key priority research areas that address pressing questions of policy and community significance. It seeks to identify knowledge gaps and foster a shared understanding of the research required to tackle the social determinants of ageing well.

The research agenda contains 38 research priorities grouped under nine pillars:

Homes, housing and the built environment

Sense of community – people (interventions for enhancing community connections)

Regional and rural (future housing needs in regional/rural areas)

Arts and culture

Life course

Social inclusion

Economic participation, income and wealth

Digital inclusion

Getting around (transportation).

The agenda also proposes four enablers to strengthen future research and the speed with which research findings and recommendations are translated into practice and policy:

Knowledge translation

Community participatory research method

Policy making process and implementation

Equity (preventing discrimination)

The final section of the agenda outlines implementation actions, such as developing research priorities of particular relevance to older Aboriginal people; establishing an Impact Research Grants programme to encourage researchers to address research questions aligned with the research agenda on ageing; and establishing Learning Labs to support knowledge translation, build capacity, and develop relationships between policy and practice.

6. Sectoral Research Agendas

The multidisciplinary framework “Understanding the Aging Workforce: Defining a Research Agenda” conceptualises pathways between work and non-work across different stages of life [

24]. The report, based on a study assessing the current state of research on work in later life, identifies key areas for future research and highlights the methodological and data infrastructure required to advance this agenda. The proposed research agenda aims to significantly improve the understanding of work in later life, providing a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of older workers' employment experiences and the constraints that shape their opportunities to work in later life.

The report outlines three promising areas for future research:

- 1.

The Relationship Between Employers and Older Workers. Key topics include: implementation of workplace policies and practices; policies influencing work and retirement decisions; and the role and impact of age discrimination.

- 24.

Work and Resource Inequalities in Later Adulthood. Research should address inequalities from three perspectives: life course dynamics of inequality – examining how inequalities develop over the life course; inequality in work opportunities – investigating disparities in access to work and employment experiences; and inequality in financial security - exploring financial disparities in later life.

- 25.

The Interface Between Work, Health and Care. Suggested research directions include: enhancing measures to identify health conditions and limitations that affect work; examining the role of mental and cognitive health in later-life employment; understanding the recent decline in health status during midlife and older age and its implications for work; identifying job characteristics that enable older adults to work longer despite health challenges; evaluating workplace practices for accommodating health-related needs.

This proposed research agenda seeks to deliver a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing work in later life, helping to inform policies and practices that support older workers.

Another example of a sectoral research agenda is presented in the article “Transportation and Aging: A Research Agenda for Advancing Safe Mobility” [

25]. Published in 2007, the article reviews what was known at the time about the safety and mobility of older drivers and identifies key research needs in several critical areas. These areas are intended to advance the safety and mobility goals of older drivers, with an emphasis on practical solutions and innovative approaches to support their unique needs:

- 1.

Screening and Evaluation: Developing effective methods to assess the driving capabilities of older adults, ensuring that evaluations are accurate and reflective of an individual's ability to drive safely.

- 26.

Education and Training Interventions: Creating targeted educational programs and training interventions to improve driving skills and adapt behaviors among older drivers, promoting safer driving practices.

- 27.

In-Vehicle Technology: Exploring the design and implementation of vehicle technologies that can assist older drivers, such as advanced driver assistance systems, to enhance safety and compensate for age-related challenges.

- 28.

Transition from Driving to Non-Driving: Investigating strategies to support older adults transitioning from driving to alternative transportation modes, ensuring they maintain mobility and independence without compromising safety.

The book “A Research Agenda for Senior Tourism” [

26], part of the Elgar Research Agendas series, identifies several key research priorities in the field of senior tourism:

Behavior and Habits of Senior Tourists

Impact of Disability on Seniors' Lives and Implications for Senior Tourism

Senior Tourists' Decision Making: Constraints and Facilitators

Non-Participation in the Tourism Industry by Seniors

Identifying Senior Tourism Market Opportunities for Micro-Tourism Owner-Managers

Senior Social Tourism Policies in the COVID-19 Era and Beyond in Europe

Socio-Economic Relevance of Social Programmes for Seniors: The Case of Portugal

Senior Tourism as a Key Element for Quality of Life, Wellness, and Combating Loneliness.

These research priorities aim to deepen the understanding of senior tourism and inform policies and practices that enhance the travel experiences of older adults.

7. Conclusion

The availability of an evidence-based foundation for policy and decision making is critical, especially in the current environment where the validity of science is increasingly challenged by populist agendas that prioritise "practical" measures over science-based approaches to policy and practice, including those related to ageing. The attacks of misinformation and disinformation, particularly in the field of health, erupted during the COVID-19 pandemic and were weaponised as propaganda [

27]. The role of evidence in informing policy decisions and the whole policy process is undeniable, and research agendas can play an important role in shaping and guiding the generation of evidence and thus supporting an evidence-based policy process.

This review article has presented only a few examples of research agendas on ageing, and new research agendas on ageing are being published regularly. However, the impact of research agendas on decision making remains unclear, as there is no documented confirmation of the use of research agendas in policy on ageing and longevity. One plausible explanation is that research and policy remain two worlds apart. This situation was described masterfully and with some bitterness by Sandra Nutley more than twenty years ago: “The research and policy worlds have different priorities, use different languages, operate to different timescales and are subjected to very different reward systems. No wonder, then, that there is frequently talk of a communications gap and the need to establish better connective mechanisms.” [

28] (p. 12).

One of the possible reasons for a communication gap is that key stakeholder groups are not involved in the analytical work of designing research agendas. Too often, this process is confined to research communities, while other key stakeholders from government, business and civil society are left out. Likewise, researchers are usually not included in the processes of policy formulation, implementation and monitoring. The involvement of all stakeholders in evidence-informed policy is essential to ensure that a research agenda would help to make the future decision-making process transparent, reliable and inclusive.

Another reason for involving key stakeholders is that research evidence is only one of several types of evidence needed for policy making. While research evidence provides scientific information according to accepted research methodologies, organisational evidence provides information on the capacity available to carry out the planned tasks, and political evidence is needed to understand how the public, politicians and other stakeholders will react to, support or hinder the proposed policy measures [

29].

Specific mechanisms for bridging the gap between research and policy are summarised in the WHO Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health [

4]:

analysing the policy context, including the role of institutions, political will, ideas and interests;

facilitating the development of evidence and knowledge that is relevant and timely;

improving communication between researchers and policy experts and decision-makers;

ensuring the accessibility of research findings to all policy actors, in particular to policy makers;

promoting a political and public culture that values and accepts sound and reliable evidence. The use of this mechanism is particularly relevant at a time when scientific ignorance and populism are on the rise.

Another limitation of research agendas on ageing is that even within the research community, there are often no follow-up mechanisms for monitoring, evaluation and revision of an established agenda. Too often an established document remains unattended and practically forgotten. The notable exception is an early history of the RAA-21, which was produced in 2002 and then updated five years later. In 2003, four regional workshops were conducted by the UN programme on ageing and IAGG to formulate research priorities on ageing for Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and for Asia and the Pacific [30, 31]. No further follow-up actions have been reported.

This article is written more than forty years after the first World Assembly on Ageing, which marked the beginning of international action on ageing. During these four decades, undeniable progress has been made in addressing the challenges and opportunities of ageing and increasing longevity. However, progress has been uneven in many parts of the world and insufficient in less developed countries. There is a need to review and, where necessary, revise international and national policy frameworks on ageing in order to identify what practical tools are available to adapt to the process and impact of demographic change in a changing world. Research agendas on ageing and longevity to inform policy decisions and actions can help to find appropriate and timely solutions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease |

| EC |

European Commission |

| EU |

European Union |

| IAGG |

International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics |

| JPI MYBL |

Joint Programming Initiative "More Years Better Lives" |

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MIPAA |

Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing |

| RAA-21 |

Research Agenda on Ageing for the Twenty-First Century |

| SRA |

Strategic Research Agenda |

| UN |

United Nations |

| UNPoA |

United Nations Programme on Ageing |

| US/USA |

United States of America |

| VIPAA |

Vienna International Plan of Action on Ageing |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

References

- United Nations. Report of the World Assembly on Aging. United Nations. United Nations: Vienna, Austria, 1982. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/Resources/VIPEE-English.pdf (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- United Nations. Report of the Second World Assembly on Ageing. Madrid. 8–12 April 2002. United Nations: New York, USA. Available online https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N02/397/51/PDF/N0239751.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- WHO. Active Ageing – a Policy Framework. A Contribution of the World Health Organization to the Second United Nations World Assembly on Ageing, Madrid, Spain, April 2002. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- WHO. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- WHO. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- National Research Council. Preparing for an Aging World: The Case for Cross-National Research. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17226/10120 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- UN and IAGG (2007). Research agenda on ageing for the twenty-first century: 2007 update. UN Programme on Ageing and IAGG: New York, 2007 Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/AgeingResearchAgenda-6.pdf (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 18 December 2002. 57/177. Situation of older women in society. United Nations: New York, USA, 2002. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/57/177 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 16 December 2005. 60/135. Follow-up to the Second World Assembly on Ageing. United Nations: New York, USA, 2005. Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n05/495/70/pdf/n0549570.pdf (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Leichsenring, K., Sidorenko, A. (eds.) A Research Agenda for Ageing and Social Policy. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, USA, 2024.

- Keating, N. A research framework for the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030). European J. of Ageing, 2022, 19 (3), pp. 775–787.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Developing an Agenda for Population Aging and Social Research in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs): Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2024. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17226/27415 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- European Commission. EU research on human development and ageing. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/research-area/health-research-and-innovation/human-development-and-ageing_en (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Horizon 2020. Health, Demographic Change and Wellbeing. Available online: https://wayback.archive-it.org/12090/20220124130848/https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/health-demographic-change-and-wellbeing (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- FUTUREAGE. A Roadmap for Ageing Research. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/223679 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- MoPAct. Research Fields. Available online: https://mopact.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/research-fields (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- SIforAGE. Social Innovation on active and healthy ageing for sustainable economic growth. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/321482/reporting (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- JPI MYBL. What is JPI MYBL? Available online: https://jp-demographic.eu/background-and-goals-what-is-jpimybl/ (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- JPI MYBL. Strategic Research Agenda. Available online: https://jp-demographic.eu/background-and-goals-what-is-jpimybl/strategic-research-agenda-sra/ (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Institute of Medicine. Extending Life, Enhancing Life: A National Research Agenda on Aging. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17226/1632 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Fang E.F., Scheibye-Knudsen M., Jahn H.J., Li J., Ling L., Guo H., Zhu X., Preedy V., Lu H., Bohr V.A., Chan W.Y, Liu Y., Tzi Bun Ng T.B. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 24, pp. 197-205.

- Strategic Research Agenda for Ageing Well in South Australia. Available online: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/about+us/department+for+health+and+wellbeing/office+for+ageing+well/south+australias+plan+for+ageing+well+2020-2025/strategic+research+agenda+for+ageing+well (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- South Australia’s Plan for Ageing Well. Available online: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/about+us/department+for+health+and+wellbeing/office+for+ageing+well/south+australias+plan+for+ageing+well+2020-2025 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding the Aging Workforce: Defining a Research Agenda. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17226/26173 (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Dickerson A.E, Molnar L.J, Eby D.W., Adler G., Bédard M., Berg-Weger M., Classen S., Foley D., Horowitz A., Kerschner H., Page O., Silverstein N.M, Staplin L., Trujillo L. Transportation and Aging: A Research Agenda for Advancing Safe Mobility. The Gerontologist, 2007, vol. 47, Issue 5, pp. 578-590. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/47.5.578.

- Vila T. D. (ed.) A Research Agenda for Senior Tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, USA, 2024.

- The Lancet Editorial. Health in the age of disinformation. The Lancet, Vol 405, p. 173.

- Nutley S. Bridging the policy research divide. Reflections and Lessons from the UK. Keynote paper presented at “Facing the Future: Engaging stakeholders and citizens in developing public policy”. National Institute of Governance Conference, Canberra, Australia 23-24 April 2003.

- Klein R. From evidence-based medicine to evidence-based policy? J. of Health Services Research & Policy, 2000, 5(2), pp. 65-66.

- Andrews G., Sidorenko A. 2004; RAA-21 Regional Priorities for Asia, Europe, and Latin America, IAG Newsletter, 2004, vol. 17(4), pp. 10-12.

- Sidorenko A. Implementation of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Aging: Research dimension. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 2004, vol. 4 (Suppl.s1): S87–S89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2004.00160.x.

Table 1.

MIPAA and RAA-21: alignments.

Table 1.

MIPAA and RAA-21: alignments.

Table 2.

Extending Life, Enhancing Life: A National Research Agenda on Aging. Research Areas and Research Priorities.

Table 2.

Extending Life, Enhancing Life: A National Research Agenda on Aging. Research Areas and Research Priorities.

| Research Area |

Research Priorities |

| Basic biomedical research |

|

| Clinical research |

|

| Behavioral and social research |

Interaction of social, psychological, and biological factors in aging Changes in population dynamics; the postponement of morbidity Changes in societal structures and aging |

| Health services delivery research |

Long-term care and continuity of care Costs and financing of long-term care Medications and older persons Mental health services Disability and disease prevention and health promotion |

| Biomedical ethics Participation of older persons in research |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).