Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

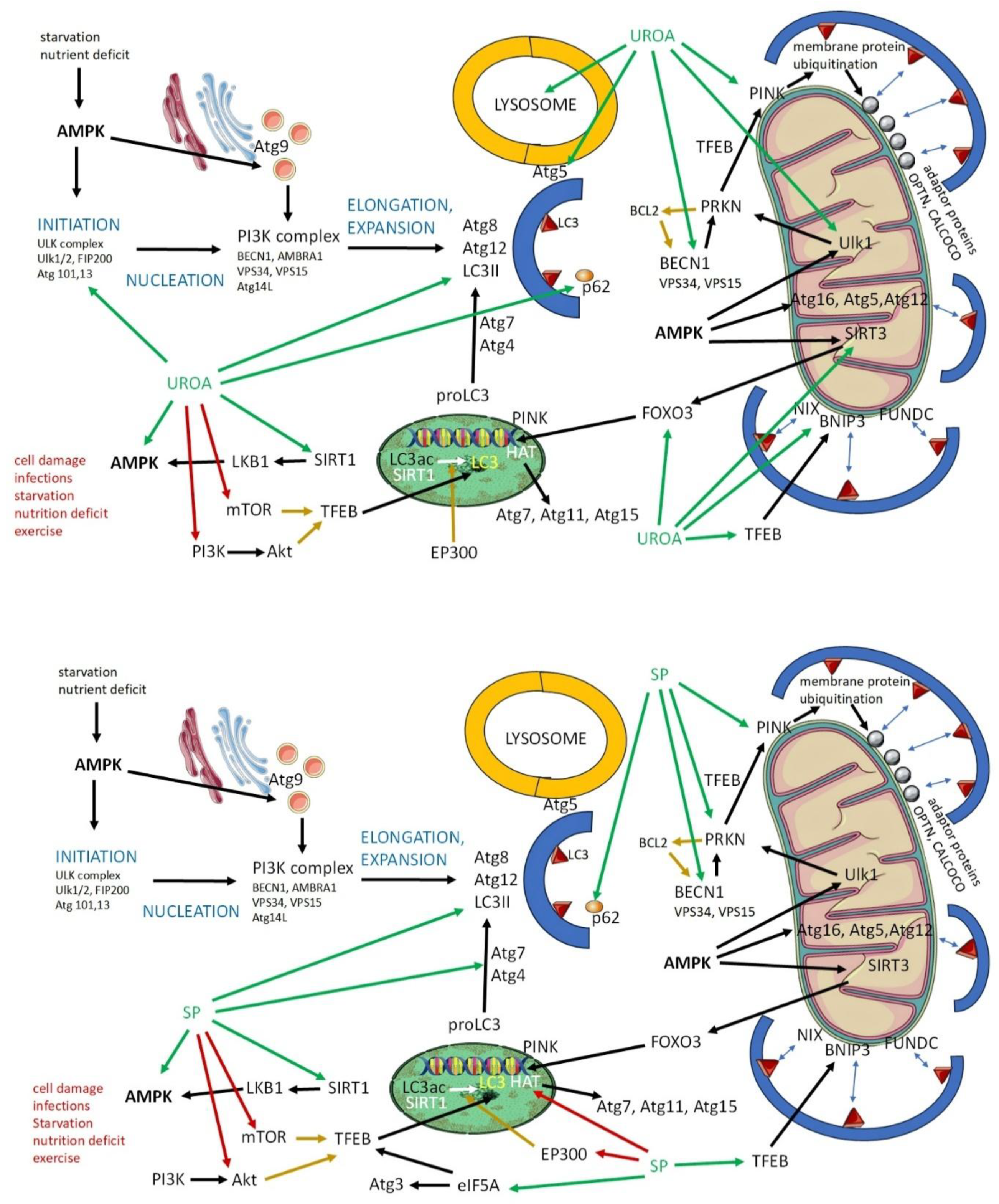

The increasing focus on longevity and cellular health has brought into the spotlight two key compounds, urolithin A (UroA) and spermidine, for their promising roles in autophagy and mitophagy. UroA, a natural metabolite derived from ellagitannins, stimulates mitophagy through pathways such as PINK1/PRKN, leading to improved mitochondrial health and enhanced muscle function. On the other hand, spermidine, a polyamine found in various food sources, induces autophagy by regulating key signaling pathways such as AMPK and SIRT1, thus mitigating age-related cellular decline and promoting cardiovascular and cognitive health. While both UroA and spermidine target cellular maintenance, they affect overlapping as well as distinct signaling pathways. Thus, they do not have completely identical effects, although they overlap in many ways, and offer varying benefits in terms of metabolic function, oxidative stress reduction, and longevity. This review article aims to describe the mechanisms of action of UroA and spermidine not only on the maintenance of cellular health, which is mediated by the induction and maintenance of autophagy and mitophagy, but also on their potential clinical relevance. The analysis presented here suggests that although both compounds are safe and offer substantial health benefits and are involved in both autophagy and mitophagy, the role of UroA in mitophagy places it as a targeted intervention for mitochondrial health, whereas the broader influence of spermidine on autophagy and metabolic regulation may provide more comprehensive anti-aging effects.

Keywords:

Introduction

Urolithin A: Sources, Dosage, and Mechanism of Action

Spermidine: Sources, Dosage, and Mechanism of Action

Urolithin A and Spermidin in Autophagy and Mitophagy: Studies In Vitro

In Vivo Studies on Urolithin A and Spermidine

Urolithin A: In Vivo Studies

Spermidine: In Vivo Studies

| Animal model | Intervention | Dose | Effect | Mechanism |

| C57BL/6 mice | High fat diet (20 weeks); mitophagy and mitochondrial function | 50 mg/kg/day, 4 weeks; p.o. | ↑ Mitophagy ↑ Cardiac diastolic function ↓ Cardiac remodeling |

↑ PINK1/PRKN-dependent mitophagy ↓ Mitochondrial defects [55] |

| C. elegans | Lifespan Mitochondria |

50 µM ad libitum, 10 days; p.o. | ↑ Mitophagy ↑ Mobility ↑ Pharyngeal pumping rate ↑ Lifespan |

↑ LC3II/LC3I ↑ PINK1 ↓ p62 [10] |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Muscle Mitochondria |

25 mg/kg/day, 7 days; p.o. | ↑ Endurance ↑ Grip strength ↑ Mitophagy ↑ Muscle function |

↑ LC3II/LC3I ↑ PINK1 ↓ p62 [10] |

| mdx mice | mdx + mdx/Utr−/− (DKO), muscular dystrophy | 50 mg/kg/day, 10 weeks; p.o. | ↑ Grip strength ↑ Tetanic force ↑ Running activity ↑ Cardiac diastolic function |

↑ PINK1/PRKN-dependent mitophagy ↓ Mitochondrial defects [52] |

| SOD1G93A transgenic mice | Motor dysfunction after administration of copper | 50 mg/kg/day, 6 weeks after a 7-week Cu exposure; p.o. | ↓ Muscle atrophy and fibrosis ↑ Motor neurons, astrocytes, and microglia |

↓ p62 ↑ PRKN ↑ PINK1 ↑ LAMP1 [53] |

| C57BL/6J mice | Age-related hearing loss |

0.5 g/kg UroA mixed with diet; p.o. | Prevented mitochondrial function decline and age-related hearing loss | ↑ Mitophagy-related RNAs (Pink1, Parkin, Bnip3, Ambra1, Nix, Bcl2, Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg12, and Atg13) and proteins (PINK1, PRKN, BNIP, LC3B), in the cochleae ↑ OXPHOS complex I, II, III, IV, in the cochleae [54] |

| C57BL/6J mice | Traumatic brain injury, neural pain |

2.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg UroA; groups: sham, sham + vehicle, TBI + vehicle, TBI + UroA; i.p. | ↓ Blood-brain barrier permeability ↓ Neuronal apoptosis in injured cortex ↑ Neurological function |

↑ p62 ↑ LC3 ↓ Akt ↓ mTOR [61] |

| C57BL/6J mice | CCI injury/traumatic brain injury |

2.5 mg/kg; groups: sham, TBI + vehicle, TBI + UroA; administered immediately after CCI injury and every 24 h for 3 days; i.p. | ↓ NSS score ↓ Brain edema |

↓ TUNEL+/NeuN+ cells ↓ Caspase-3 ↑ BCL2 ↑ LC3II/LC3I ↓ p62 ↓ p-Akt/Akt ↓ p-mTOR/mTOR ↓ p-IKKα/IKKα ↓ p-NFκB/NFκB, in the hippocampus [62] |

| 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice | STZ-induced model of type 2 diabetes |

50 mg/kg/day, 8 weeks; oral gavage | ↓ Fasting blood glucose ↓ Glycated hemoglobin ↓ Plasma C-peptide ↑ Glucose tolerance ↓ Malondialdehyde ↓ IL-1β ↑ IL-10 ↑ Reduced glutathione ↓ Inflammation ↑ Metabolic health |

↑ LC3II/LC3I ↑ Beclin1 ↑ ATG5 ↓ Mitochondrial swelling ↓ p62 ↑ p-Akt ↑ p-mTOR [67] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Obesity induced cardiomyopathy, high fat diet (20 weeks) |

50 mg/kg/day, 4 weeks; gavage | ↑ Cardiac diastolic function ↓ Cardiac remodeling | ↑ PINK1/PRKN-dependent mitophagy [55] |

| C57BL mice | Cardiac I/R model | 1 mg/kg UroA; groups: sham, sham + UroA, cardiac I/R, cardiac I/R + UroA; administered 24 h prior to surgery; i.p. | Cardiac tissue protection | ↓ Oxidative stress ↑ Nrf2 pathway ↓ Tissue damage [58] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Middle cerebral artery occlusion | 2.5 or 5.0 mg/kg UroA, 24 h and 1 h prior to surgery; i.p. | Neuroprotection | ↑ LC3 ↓ p62 [57] |

| C57BL/6 male mice | I/R injury, kidney | 50 mg/kg, 3 days prior and 30 min before surgery; i.p. |

Pretreatment attenuated kidney dysfunction in IRI | ↑ TFEB ↑ LAMP1 ↑ Atp6ap1 ↑ Beclin1 [56] |

| 1-week-old C57BL/6 | Pediatric pneumonia | 2.5 and 5 mg/kg, 1 h before LPS; i.p. | Alleviated lung inflammation | ↑ LC3II ↑ Beclin ↓ p62 [63] |

| C57BL/6 mice | IBD model (colitis induced by 2.5% DSS) | 4 mg/kg UroA, orally administered on day 4, 6, and 8; groups: inflammation-targeting nanoparticles (ITNP), ITNP-UroA, free UroA; p.o. | ↓ Inflammation ↑ Barrier functions |

↓ Shortening of colon ↓ Myeloperoxidase (neutrophil marker) ↓ Inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) [64] |

|

pp2r1aflox/flox, Vill-Cre mice, and C57BL/6-Rosa26/tdTomato mice |

Intestinal damage, hexavalent chromium | 20 mg/kg; p.o. | ↓ Epithelial damage ↑ Barrier functions ↑ Reparation |

↑ Phosphorylation of YAP1 ↑ Proliferation/repair defects in intestinal epithelium [65] |

| APP/PS1 mouse 3xTgAD and 3xTgAD/Polβ+/− |

Alzheimer disease model | 200 mg/kg/day, 5 months; gavage |

↑ Brain function ↑ Learning and memory ↓ Inflammation |

↓ Aβ and tau protein deposition ↑ Lysosomal functions ↓ IL-β ↑ Sirtuin ↑ Mitophagy ↓ DNA damage [44] |

| APP/PS1 mouse, 3×TgAD mouse | Alzheimer disease model | 200 mg/kg/day; p.o. | ↓ Brain function decline ↓ Aβ plaque |

↑ PINK1 [60] |

| 3xTg-AD mice, female B6129SF2/J (#101,045), and male C57BL/6NJ | Alzheimer disease model | 25 mg/kg, alternate weeks (1 week on, 1 week off), 9-10 months; p.o. | ↑ Removing Aβ Prevents the onset of cognitive deficits |

↑ LC3 ↓ p62 [59] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Hyperosmotic stress and corneal epithelial injury | UroA eye drops, 10 drops/day, 7 days | ↓ Accumulation of senescent cells in corneal epithelial wounds ↑ Wound healing |

↓ Oxidative stress ↓ Lipid peroxidation ↓ Malondialdehyde ↓ Ferroptosis [66] |

| Animal model | Intervention | Dose | Effect | Mechanism |

| Bees | Longevity | 0.1 and 1 mM, 17 days; p.o. | ↑ Longevity | ↑ Autophagy-related genes (Atg3, Atg5, Atg9, Atg13) ↑ Genes associated with epigenetic changes (HDAC1, HDAC3, SIRT1, KAT2A, KAT6B, P300, DNMT1A, DNMT1B) [39] |

| C. elegans | Longevity | 1–20 mM; ad libitum | ↑ Lifespan ↑ Healthspan ↓ Memory loss ↓ Loss of locomotor capacity |

↑ PINK-PDR-1 pathway [73] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Longevity | 0.3 and 3 mM, 200 days; p.o. | ↑ Longevity | ↑ Mitochondrial function ↓ Acetylation of histone H3 ↓ HAT activity ↑ Atg7 [16] |

| Mouse-8 (SAMP8) | Senescence accelerated | 0.78 mg/kg/day, spermidine, spermine, rapamycin, or saline, 8 weeks; i.g. | ↑ Memory retention ↑ Synaptic plasticity ↑ Neurotrophic factors ↓ Oxidative stress |

↑ AMPK ↑ LC3 ↑ Beclin1 ↑ p62 [18] |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Aging | 25 mg/kg/day, from 18 months old until death; p.o. | ↓ Inflammation ↓ Neurodegeneration |

↑ MAP1B-LC3a ↑ LAMP1 [72] |

| Young rats (4 months) | D-galactose induced senescence |

10 mg/kg, 6 weeks; p.o |

↓ Aging ↓ Oxidative stress |

↓ ROS production ↓ Lipid and protein oxidation ↑ Antioxidants ↑ Plasma membrane redox system in erythrocyte membrane [68] |

| Zebrafish embryos | Machado-Joseph disease, also known as spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 | Single administration of spermidine (62.5 µM, 125 µM and 250 µM, solubilized in E3 medium) | ↓ Neurological deficit | ↑ LC3 ↑ p62 [42] |

| CMVMJD135 mouse model | Machado-Joseph disease, also known as spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 | 3 mM; p.o. | ↑ Neurological score ↑ Balance ↑ Coordination |

↑ p-ULK1 ↑ LC3 ↑ p62 [42] |

| Mice | Collagen type VI-related myopathies | 30 mM, 60 or 100 days; p.o. | Rescue muscle strength (↑ Absolute and normalized contractile force, 100 days administration; ↑ Hanging performance, 60 and 100 days administration) | ↑ LC3II ↑ p62 ↑ BNIP3 ↑ OPTN [77] |

| APPPS1+/− mice | Alzheimer disease model | 3 mM, 90 or 260 days; p.o. | ↑ Brain function | ↑ SIRT3 ↑ Aβ degradation ↑ Autophagy [70] |

| C57BL/6*GFP-LC3 transgenic mice | Alzheimer disease model | 0.3 mM + PQ and 3 mM + PQ, every 3 days for 3 weeks; i.p. | ↓ Neuronal toxicity of paraquat | ↑ Autophagic flux ↑ LC3 [69] |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Parkinson disease model | 5 mM spermidine; p.o. | ↓ Brain function | ↓ α-synuclein ↑ Atg8 [71] |

| Wistar rats | Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) model induced by isoproterenol injections | Before AMI induction, 2.5 mg/kg/day, 7 days; i.p. | ↓ Dysfunction and cardiac enzymes | ↑ LC3II ↑ TFEB ↑ p62 [75] |

| C57BL/6J mice | High-salt diet myocardial injury |

3 mM, 4 weeks; p.o. | ↓ Systemic blood pressure ↓ Cardiac hypertrophy ↓ Decline in diastolic function ↑ Titin phosphorylation |

↑ Cardiomyocyte autophagic flux ↑ LC3II [74] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Ischemia-reperfusion injury | 3mM, 4 weeks before IR; gavage | ↓ I/R-induced apoptosis in the liver ↓ Loss of liver function |

↑ Beclin1 ↑ LC3II/LC3I (AMPK-mTOR-ULK1 pathway) [76] |

| C57B/L6 mice | Arterial aging (cardiovascular disease) | 3 mM, 4 weeks; p.o. | Normalized aortic pulse wave velocity ↓ Nitrotyrosine ↓ Superoxide ↓ AGEs ↓ Collagen in arterial wall |

↓ Acetylation of histone H3 ↑ Atg3 ↑ LC3II ↓ p62 in old mice [79] |

| C57BL/6J mice | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 3 mmol/L, on the day of or 3 days after PPE infusion, continued until euthanasia; p.o. | Prevented aneurysm development ↓ Inflammation in aorta and systemic ↑ Autophagy |

↑ LC3II/LC3I ↑ Beclin1 ↓ mTOR ↓ p62 [78] |

| Lupus-prone (MRL/lpr) mice | Model of systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 M aqueous stock solution, every 3–4 days, 8 weeks; p.o. |

Prevented endothelial dysfunction | ↓ Inflammation ↓ Autoantibodies ↑ Mitophagy ↑ Vasorelaxation [81] |

| BALB/c mice | Model of infections (MRSA) |

3 mmol in drinking water, 2 weeks, with antibiotic treatment and fecal microbiota transplantation | ↓ Bacterial load | ↑ PTPN2 expression ↑ M2 macrophages [83] |

| Sows | Placentogenesis, gravidity | 10 or 20 mg/kg, at day 60 of gestation | ↑ Placental functions ↑ Healthy offsprings ↓ Mummified litter ↓ Weak offsprings |

↑ Expression PECAM-1 ↑ Density of placental stromal vessels ↑ Amino acid transporters, glucose transporters [80] |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Osteoarthritis model | 2.5 mg/kg and 5.0 mg/kg; i.p. |

Counteract the disease progression | ↓ Inflammation ↓ Pyroptosis ↓ IL-1β ↑ AhR-spermidine binding ↓ AhR/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling pathways [82] |

Clinical Studies on Urolithin A and Spermidine

Urolithin A: Clinical Studies

Spermidine: Clinical Studies

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Consent for publication

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

List of Abbreviations

| Akt | protein kinase B |

| AMI | acute myocardial infarction |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| Atg | autophagy-related genes |

| BECN1 | beclin 1 |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BNIP3 | BCL2 interacting protein 3 |

| eIF5A | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 |

| EP300 | histone acetyltransferase p300 |

| HAT | histone acetyltransferase |

| MRSA | methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| LC3 | microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NIX | NIP3-like protein X |

| OPTN | optineurin |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α |

| PRKN | parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase |

| PINK1 | PTEN induced kinase 1 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SIRT | sirtuin |

| ULK1 | unc-51 like kinase 1 |

| UroA | urolithin A |

| TFEB | transcription factor EB |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor α |

References

- Palmer JE, Wilson N, Son SM, Obrocki P, Wrobel L, Rob M, et al. Autophagy, aging, and age-related neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2025;113(1):29-48.

- Picca A, Faitg J, Auwerx J, Ferrucci L, D’Amico D. Mitophagy in human health, ageing and disease. Nature Metabolism. 2023;5(12):2047-61. [CrossRef]

- Kuerec AH, Lim XK, Khoo AL, Sandalova E, Guan L, Feng L, et al. Targeting aging with urolithin A in humans: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;100:102406. [CrossRef]

- Arthur R, Jamwal S, Kumar P. A review on polyamines as promising next-generation neuroprotective and anti-aging therapy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;978:176804. [CrossRef]

- Kothe B, Klein S, Petrosky SN. Urolithin A as a Potential Agent for Prevention of Age-Related Disease: A Scoping Review. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42550. [CrossRef]

- Hofer SJ, Daskalaki I, Bergmann M, Friščić J, Zimmermann A, Mueller MI, et al. Spermidine is essential for fasting-mediated autophagy and longevity. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(9):1571-84. [CrossRef]

- Hua Z, Wu Q, Yang Y, Liu S, Jennifer TG, Zhao D, et al. Essential roles of ellagic acid-to-urolithin converting bacteria in human health and health food industry: An updated review. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2024;151:104622. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, D’Amico D, Andreux PA, Dunngalvin G, Kern T, Blanco-Bose W, et al. Direct supplementation with Urolithin A overcomes limitations of dietary exposure and gut microbiome variability in healthy adults to achieve consistent levels across the population. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2022;76(2):297-308. [CrossRef]

- Andreux PA, Blanco-Bose W, Ryu D, Burdet F, Ibberson M, Aebischer P, et al. The mitophagy activator urolithin A is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans. Nature Metabolism. 2019;1(6):595-603. [CrossRef]

- Ryu D, Mouchiroud L, Andreux PA, Katsyuba E, Moullan N, Nicolet-dit-Félix AA, et al. Urolithin A induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nature Medicine. 2016;22(8):879-88. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, D'Amico D, Shankland E, Bhayana S, Garcia JM, Aebischer P, et al. Effect of Urolithin A Supplementation on Muscle Endurance and Mitochondrial Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2144279.

- Singh A, D'Amico D, Andreux PA, Fouassier AM, Blanco-Bose W, Evans M, et al. Urolithin A improves muscle strength, exercise performance, and biomarkers of mitochondrial health in a randomized trial in middle-aged adults. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3(5):100633. [CrossRef]

- Madeo F, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Kepp O, Kroemer G. Spermidine delays aging in humans. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(8):2209-11. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz C, Horn N, Benson G, Wrachtrup Calzado I, Wurdack K, Pechlaner R, et al. Spermidine intake is associated with cortical thickness and hippocampal volume in older adults. Neuroimage. 2020;221:117132. [CrossRef]

- Senekowitsch S, Wietkamp E, Grimm M, Schmelter F, Schick P, Kordowski A, et al. High-Dose Spermidine Supplementation Does Not Increase Spermidine Levels in Blood Plasma and Saliva of Healthy Adults: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Pharmacokinetic and Metabolomic Study. Nutrients. 2023;15(8). [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Büttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nature Cell Biology. 2009;11(11):1305-14. [CrossRef]

- Jeong JW, Cha HJ, Han MH, Hwang SJ, Lee DS, Yoo JS, et al. Spermidine Protects against Oxidative Stress in Inflammation Models Using Macrophages and Zebrafish. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2018;26(2):146-56. [CrossRef]

- Xu TT, Li H, Dai Z, Lau GK, Li BY, Zhu WL, et al. Spermidine and spermine delay brain aging by inducing autophagy in SAMP8 mice. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(7):6401-14. [CrossRef]

- Aman Y, Schmauck-Medina T, Hansen M, Morimoto RI, Simon AK, Bjedov I, et al. Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nature Aging. 2021;1(8):634-50. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Chen Y, Tooze SA. Autophagy pathway: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Autophagy. 2018;14(2):207-15. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann A, Madeo F, Diwan A, Sadoshima J, Sedej S, Kroemer G, et al. Metabolic control of mitophagy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2024;54(4):e14138. [CrossRef]

- Lamark T, Johansen T. Mechanisms of Selective Autophagy. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2021;37:143-69. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Long H, Hou L, Feng B, Ma Z, Wu Y, et al. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023;8(1):304. [CrossRef]

- Velagapudi R, Lepiarz I, El-Bakoush A, Katola FO, Bhatia H, Fiebich BL, et al. Induction of Autophagy and Activation of SIRT-1 Deacetylation Mechanisms Mediate Neuroprotection by the Pomegranate Metabolite Urolithin A in BV2 Microglia and Differentiated 3D Human Neural Progenitor Cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63(10):e1801237. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Zhuge J, Zheng X, Wu Y, Zhang Z, Xu T, et al. Urolithin A-induced mitophagy suppresses apoptosis and attenuates intervertebral disc degeneration via the AMPK signaling pathway. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2020;150:109-19. [CrossRef]

- Hofer SJ, Daskalaki I, Bergmann M, Friščić J, Zimmermann A, Mueller MI, et al. Spermidine is essential for fasting-mediated autophagy and longevity. Nature Cell Biology. 2024;26(9):1571-84. [CrossRef]

- Kriebs A. Spermidine controls autophagy during fasting. Nature Aging. 2024;4(9):1172-. [CrossRef]

- Holzer E, Martens S, Tulli S. The Role of ATG9 Vesicles in Autophagosome Biogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2024;436(15):168489. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Chen S, Zhang Y, Lin X, Song Y, Xue Z, et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine is neuroprotective via inhibition of caspase 3-mediated Beclin 1 cleavage. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(4):e2738. [CrossRef]

- Lubas M, Harder LM, Kumsta C, Tiessen I, Hansen M, Andersen JS, et al. eIF5A is required for autophagy by mediating ATG3 translation. EMBO Rep. 2018;19(6). [CrossRef]

- Prasher P, Sharma M, Singh SK, Gulati M, Chellappan DK, Rajput R, et al. Spermidine as a promising anticancer agent: Recent advances and newer insights on its molecular mechanisms. Front Chem. 2023;11:1164477. [CrossRef]

- Niu C, Jiang D, Guo Y, Wang Z, Sun Q, Wang X, et al. Spermidine suppresses oxidative stress and ferroptosis by Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 and Akt/FHC/ACSL4 pathway to alleviate ovarian damage. Life Sci. 2023;332:122109.

- Zhang Y, Jiang L, Su P, Yu T, Ma Z, Liu Y, et al. Urolithin A suppresses tumor progression and induces autophagy in gastric cancer via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Drug Dev Res. 2023;84(2):172-84. [CrossRef]

- Sahashi H, Kato A, Yoshida M, Hayashi K, Naitoh I, Hori Y, et al. Urolithin A targets the AKT/WNK1 axis to induce autophagy and exert anti-tumor effects in cholangiocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:963314. [CrossRef]

- Hofer SJ, Simon AK, Bergmann M, Eisenberg T, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Mechanisms of spermidine-induced autophagy and geroprotection. Nature Aging. 2022;2(12):1112-29. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Pang J, Tripathi M, Ho JP, Widjaja AA, Shekeran SG, et al. Spermidine-mediated hypusination of translation factor EIF5A improves mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and prevents non-alcoholic steatohepatitis progression. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1):5202. [CrossRef]

- Zhao W, Shi F, Guo Z, Zhao J, Song X, Yang H. Metabolite of ellagitannins, urolithin A induces autophagy and inhibits metastasis in human sw620 colorectal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57(2):193-200. [CrossRef]

- Satarker S, Wilson J, Kolathur KK, Mudgal J, Lewis SA, Arora D, et al. Spermidine as an epigenetic regulator of autophagy in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;979:176823. [CrossRef]

- Kojić D, Spremo J, Đorđievski S, Čelić T, Vukašinović E, Pihler I, et al. Spermidine supplementation in honey bees: Autophagy and epigenetic modifications. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0306430. [CrossRef]

- Liu WJ, Ye L, Huang WF, Guo LJ, Xu ZG, Wu HL, et al. p62 links the autophagy pathway and the ubiqutin–proteasome system upon ubiquitinated protein degradation. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters. 2016;21(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Viedma-Poyatos Á, Gómez-Sintes R, Boya P. Urolithin A promotes p62-dependent lysophagy to prevent acute retinal neurodegeneration. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2024;19(1):49. [CrossRef]

- Watchon M, Wright AL, Ahel HI, Robinson KJ, Plenderleith SK, Kuriakose A, et al. Spermidine treatment: induction of autophagy but also apoptosis? Mol Brain. 2024;17(1):15.

- de Wet S, Du Toit A, Loos B. Spermidine and Rapamycin Reveal Distinct Autophagy Flux Response and Cargo Receptor Clearance Profile. Cells. 2021;10(1).

- Hou Y, Chu X, Park JH, Zhu Q, Hussain M, Li Z, et al. Urolithin A improves Alzheimer's disease cognition and restores mitophagy and lysosomal functions. Alzheimers Dement. 2024;20(6):4212-33.

- Wang S, Chen Y, Li X, Zhang W, Liu Z, Wu M, et al. Emerging role of transcription factor EB in mitochondrial quality control. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128:110272. [CrossRef]

- Faitg J, D'Amico D, Rinsch C, Singh A. Mitophagy Activation by Urolithin A to Target Muscle Aging. Calcif Tissue Int. 2024;114(1):53-9. [CrossRef]

- Zheng B, Wang Y, Zhou B, Qian F, Liu D, Ye D, et al. Urolithin A inhibits breast cancer progression via activating TFEB-mediated mitophagy in tumor macrophages. Journal of Advanced Research. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fairley LH, Lejri I, Grimm A, Eckert A. Spermidine Rescues Bioenergetic and Mitophagy Deficits Induced by Disease-Associated Tau Protein. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6). [CrossRef]

- Jayatunga DPW, Hone E, Khaira H, Lunelli T, Singh H, Guillemin GJ, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Mitophagy-Inducing Microflora Metabolite, Urolithin A for Alzheimer's Disease. Nutrients. 2021;13(11). [CrossRef]

- Jang JS, Hong SJ, Mo S, Kim MK, Kim YG, Lee Y, et al. PINK1 restrains periodontitis-induced bone loss by preventing osteoclast mitophagy impairment. Redox Biol. 2024;69:103023. [CrossRef]

- Cho SI, Jo E-R, Song H. Urolithin A attenuates auditory cell senescence by activating mitophagy. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):7704. [CrossRef]

- Luan P, D’Amico D, Andreux PA, Laurila P-P, Wohlwend M, Li H, et al. Urolithin A improves muscle function by inducing mitophagy in muscular dystrophy. Science Translational Medicine. 2021;13(588):eabb0319. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Gao C, Yang D, Nie L, He K, Chen C, et al. Urolithin a Improves Motor Dysfunction Induced by Copper Exposure in SOD1(G93A) Transgenic Mice Via Activation of Mitophagy. Mol Neurobiol. 2024.

- Cho SI, Jo ER, Jang HS. Urolithin A prevents age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6J mice likely by inducing mitophagy. Exp Gerontol. 2024;197:112589. [CrossRef]

- Huang JR, Zhang MH, Chen YJ, Sun YL, Gao ZM, Li ZJ, et al. Urolithin A ameliorates obesity-induced metabolic cardiomyopathy in mice via mitophagy activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44(2):321-31.

- Wang Y, Huang H, Jin Y, Shen K, Chen X, Xu Z, et al. Role of TFEB in autophagic modulation of ischemia reperfusion injury in mice kidney and protection by urolithin A. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2019;131:110591. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan A, Zheng YR, Wu XL, Tang WD, Liu MR, Ma SJ, et al. Urolithin A-activated autophagy but not mitophagy protects against ischemic neuronal injury by inhibiting ER stress in vitro and in vivo. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25(9):976-86. [CrossRef]

- Su Z, Li P, Ding W, Gao Y. Urolithin A improves myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by attenuating oxidative stress and ferroptosis through Nrf2 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143(Pt 2):113394. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Álvarez J, Nguyen W, Sivapatham R, Rane A, Andersen JK. Urolithin A reduces amyloid-beta load and improves cognitive deficits uncorrelated with plaque burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Geroscience. 2023;45(2):1095-113. [CrossRef]

- Fang EF, Hou Y, Palikaras K, Adriaanse BA, Kerr JS, Yang B, et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Neuroscience. 2019;22(3):401-12. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Wang Z, Xue S, Zhu Y, Jin J, Ren Q, et al. Urolithin A alleviates neuropathic pain and activates mitophagy. Mol Pain. 2023;19:17448069231190815. [CrossRef]

- Gong QY, Cai L, Jing Y, Wang W, Yang DX, Chen SW, et al. Urolithin A alleviates blood-brain barrier disruption and attenuates neuronal apoptosis following traumatic brain injury in mice. Neural Regen Res. 2022;17(9):2007-13. [CrossRef]

- Cao X, Wan H, Wan H. Urolithin A induces protective autophagy to alleviate inflammation, oxidative stress, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in pediatric pneumonia. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2022;50(6):147-53.

- Ghosh S, Singh R, Goap TJ, Sunnapu O, Vanwinkle ZM, Li H, et al. Inflammation-targeted delivery of Urolithin A mitigates chemical- and immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22(1):701. [CrossRef]

- Guo P, Yang R, Zhong S, Ding Y, Wu J, Wang Z, et al. Urolithin A attenuates hexavalent chromium-induced small intestinal injury by modulating PP2A/Hippo/YAP1 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2024;300(9):107669. [CrossRef]

- Guo XX, Chang XJ, Pu Q, Li AL, Li J, Li XY. Urolithin A alleviates cell senescence by inhibiting ferroptosis and enhances corneal epithelial wound healing. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1441196.

- Tuohetaerbaike B, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Zhang NN, Kang J, Mao X, et al. Pancreas protective effects of Urolithin A on type 2 diabetic mice induced by high fat and streptozotocin via regulating autophagy and AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;250:112479. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Verma AK, Garg G, Singh AK, Rizvi SI. Spermidine protects cellular redox status and ionic homeostasis in D-galactose induced senescence and natural aging rat models. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lumkwana D, Peddie C, Kriel J, Michie LL, Heathcote N, Collinson L, et al. Investigating the Role of Spermidine in a Model System of Alzheimer's Disease Using Correlative Microscopy and Super-resolution Techniques. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:819571. [CrossRef]

- Freitag K, Sterczyk N, Wendlinger S, Obermayer B, Schulz J, Farztdinov V, et al. Spermidine reduces neuroinflammation and soluble amyloid beta in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):172. [CrossRef]

- Büttner S, Broeskamp F, Sommer C, Markaki M, Habernig L, Alavian-Ghavanini A, et al. Spermidine protects against α-synuclein neurotoxicity. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(24):3903-8. [CrossRef]

- Filfan M, Olaru A, Udristoiu I, Margaritescu C, Petcu E, Hermann DM, et al. Long-term treatment with spermidine increases health span of middle-aged Sprague-Dawley male rats. Geroscience. 2020;42(3):937-49. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Zhang M, Dai Y, Sun Y, Aman Y, Xu Y, et al. Spermidine inhibits neurodegeneration and delays aging via the PINK1-PDR1-dependent mitophagy pathway in C. elegans. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(17):16852-66. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg T, Abdellatif M, Schroeder S, Primessnig U, Stekovic S, Pendl T, et al. Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nature Medicine. 2016;22(12):1428-38. [CrossRef]

- Omar EM, Omar RS, Shoela MS, El Sayed NS. A study of the cardioprotective effect of spermidine: A novel inducer of autophagy. Chin J Physiol. 2021;64(6):281-8.

- Liu H, Dong J, Song S, Zhao Y, Wang J, Fu Z, et al. Spermidine ameliorates liver ischaemia-reperfusion injury through the regulation of autophagy by the AMPK-mTOR-ULK1 signalling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;519(2):227-33.

- Gambarotto L, Metti S, Corpetti M, Baraldo M, Sabatelli P, Castagnaro S, et al. Sustained oral spermidine supplementation rescues functional and structural defects in COL6-deficient myopathic mice. Autophagy. 2023;19(12):3221-9. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Huang T, Liu R, Cai H, Pan B, Liao M, et al. Spermidine Suppresses Development of Experimental Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(8):e014757. [CrossRef]

- LaRocca TJ, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Hearon CM, Jr., Seals DR. The autophagy enhancer spermidine reverses arterial aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134(7-8):314-20. [CrossRef]

- Duan B, Ran S, Wu L, Dai T, Peng J, Zhou Y. Maternal supplementation spermidine during gestation improves placental angiogenesis and reproductive performance of high prolific sows. J Nutr Biochem. 2024;136:109792. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Massett MP. Effect of Spermidine on Endothelial Function in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18). [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Feng X, Yang Y, Zhang H, Bai L. Spermidine attenuates chondrocyte inflammation and cellular pyroptosis through the AhR/NF-κB axis and the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pathway. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1462777.

- Li Q, Tian P, Guo M, Liu X, Su T, Tang M, et al. Spermidine Associated with Gut Microbiota Protects Against MRSA Bloodstream Infection by Promoting Macrophage M2 Polarization. ACS Infect Dis. 2024;10(11):3751-64. [CrossRef]

- Bookheimer SY, Renner BA, Ekstrom A, Li Z, Henning SM, Brown JA, et al. Pomegranate juice augments memory and FMRI activity in middle-aged and older adults with mild memory complaints. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:946298. [CrossRef]

- Siddarth P, Li Z, Miller KJ, Ercoli LM, Merril DA, Henning SM, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled study of the memory effects of pomegranate juice in middle-aged and older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(1):170-7. [CrossRef]

- Torregrosa-García A, Ávila-Gandía V, Luque-Rubia AJ, Abellán-Ruiz MS, Querol-Calderón M, López-Román FJ. Pomegranate Extract Improves Maximal Performance of Trained Cyclists after an Exhausting Endurance Trial: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2019;11(4). [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Zhu H, Yun H, Liu J, Song G, Teng J, et al. Assessment of Urolithin A effects on muscle endurance, strength, inflammation, oxidative stress, and protein metabolism in male athletes with resistance training: an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2024;21(1):2419388. [CrossRef]

- Bellone JA, Murray JR, Jorge P, Fogel TG, Kim M, Wallace DR, et al. Pomegranate supplementation improves cognitive and functional recovery following ischemic stroke: A randomized trial. Nutr Neurosci. 2019;22(10):738-43.

- Liu H, Birk JW, Provatas AA, Vaziri H, Fan N, Rosenberg DW, et al. Correlation between intestinal microbiota and urolithin metabolism in a human walnut dietary intervention. BMC Microbiol. 2024;24(1):476. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz C, Benson GS, Horn N, Wurdack K, Grittner U, Schilling R, et al. Effects of Spermidine Supplementation on Cognition and Biomarkers in Older Adults With Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2213875.

- Pekar T, Bruckner K, Pauschenwein-Frantsich S, Gschaider A, Oppliger M, Willesberger J, et al. The positive effect of spermidine in older adults suffering from dementia : First results of a 3-month trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(9-10):484-91.

- Kiechl S, Pechlaner R, Willeit P, Notdurfter M, Paulweber B, Willeit K, et al. Higher spermidine intake is linked to lower mortality: a prospective population-based study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(2):371-80. [CrossRef]

- Wirth M, Benson G, Schwarz C, Köbe T, Grittner U, Schmitz D, et al. The effect of spermidine on memory performance in older adults at risk for dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Cortex. 2018;109:181-8. [CrossRef]

- Félix J, Díaz-Del Cerro E, Baca A, López-Ballesteros A, Gómez-Sánchez MJ, De la Fuente M. Human Supplementation with AM3, Spermidine, and Hesperidin Enhances Immune Function, Decreases Biological Age, and Improves Oxidative-Inflammatory State: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13(11).

- Rhodes CH, Hong BV, Tang X, Weng CY, Kang JW, Agus JK, et al. Absorption, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and cardioprotective impacts of a novel fasting mimetic containing spermidine, nicotinamide, palmitoylethanolamide, and oleoylethanolamide: A pilot dose-escalation study in healthy young adult men. Nutr Res. 2024;132:125-35. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Li N, Zeng Y. Protective effects of spermidine levels against cardiovascular risk factors: An exploration of causality based on a bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis. Nutrition. 2024;127:112549. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Cai P, Hu A, Li J, Li X, Dang Y. The role of 1400 plasma metabolites in gastric cancer: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study and metabolic pathway analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(48):e40612. [CrossRef]

- Iorio-Siciliano V, Marasca D, Mauriello L, Vaia E, Stratul SI, Ramaglia L. Treatment of peri-implant mucositis using spermidine and calcium chloride as local adjunctive delivery to non-surgical mechanical debridement: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2024;28(10):537. [CrossRef]

- Keohane P, Everett JR, Pereira R, Cook CM, Blonquist TM, Mah E. Supplementation of spermidine at 40 mg/day has minimal effects on circulating polyamines: An exploratory double-blind randomized controlled trial in older men. Nutr Res. 2024;132:1-14.

| Patients | Trial | Treatment | Effect | Finding |

| N = 32 (N = 28 completers) (54–72 y), self-reported age-related memory complaints |

Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | 240 mL/day of pomegranate juice (N = 15) or placebo drink (N = 13), 4 weeks | ↓ Anti-age-related memory decline | ↑ fMRI activity during verbal and visual memory tasks ↑ Memory ability ↑ Plasma antioxidant status (84) |

| N = 261 (50–75 y), age-related memory decline |

Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | 236.5 mL/day of pomegranate juice (N = 98) or placebo drink (N = 102), 12 months |

↓ Anti-age-related memory decline | ↑ Visual memory ↑ Visual learning and recall ↑ Verbal memory, words recall (85) |

| N = 60 (single ascending dose N = 24, multiple ascending dose N= 36) (60-80 y) | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | 250 mg, 1000 mg, or 2000 mg of UroA, 28 days | ↑ Mitochondria health | 1,000 mg modulated plasma acylcarnitines and skeletal muscle mitochondrial gene expression (9) |

| N = 88 (40-65 y), overweight | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | 500 mg (N = 29), 1,000 mg (N = 30) of UroA or placebo, 4 months | ↓ Inflammation ↑ Condition |

↑ Muscle strength, endurance, physical performance ↓ Acylcarnitines, CRP, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFNγ in plasma (12) |

| N = 66 (65- 90 y), healthy | Randomized, placebo-controlled | 1000 mg/day of UroA, assessments at 2 and 4 months | ↓ Inflammation ↑ Condition |

↑ Muscle endurance, physical performance ↓ Acylcarnitines, ceramides, and CRP in plasma (11) |

| N = 16, patients with stroke | Parallel, block-randomized | 1 g of polyphenols derived from whole pomegranate/twice a day, 7 days | Neuroprotection | ↑ Neuropsychological and functional improvement ↓ Time in the hospital (88) |

| N = 26 (34.9 ± 10.0 y), trained cyclists | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, balanced, cross-over trial with two arms | 750 mg/day of POMANOX® P30 (225 mg punicalagins α + β), 15 days | ↑ Condition | ↑ Total time to exhaustion ↓ Time to reach ventilatory threshold (86) |

| N = 39, healthy adults | Dietary intervention study | 2 oz of walnuts/day, 21 days | Changes in microbiota | ↑ UroA metabolites (89) |

| Patients | Trial | Treatment | Effect | Finding |

| N = 85 (60-96 y) | Randomized, two-group, double-blind, multicentric and longitudinal | 3.3 mg/day of spermidine (roll A) or 1.9 mg/day of spermidine (roll B), 6 times/week, 3 months | ↑ Brain function | ↑ Test performance in the mini mental state examination ↑ Phonematic fluidity (91) |

| N = 30 (60-80 y) | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIa | 1.2 mg/day of spermidine (750 mg spermidine-rich plant extract + 510 mg cellulose), 3 months | ↑ Brain function | ↑ Memory performance ↑ Mnemonic discrimination ability (93) |

| N = 100 (60-90 y) | Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled phase IIb | 0.9 mg/day of spermidine (750 mg plant extract including 0.5 mg spermine, 0.2 mg putrescine, <0.004 mg cadaverine, and 0.12 mg L-ornithine), 12 months | ↑ Brain function | ↑ Mnemonic discrimination performance (90) |

| N = 137 (60–90 y) | Cross-sectional study | Dietary spermidine intake assessed via self-reported FFQ | ↑ Brain morphology | ↑ Hippocampal volume ↑ Mean cortical thickness (14) |

| N = 829 (45–84 y) | Prospective community-based cohort study, follow-up of 20 y | Dietary spermidine intake estimated from 20-year cumulative FFQ data | ↓ All causes mortality | ↓ Vascular, cancer, non-vascular, non-cancer mortality (92) |

| N = 41 (30-60 y) | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | Total daily dose: 1.2 mg spermidine, 300 mg AM3 (20%), 100 mg hesperidin, 598.14 mg calcium phosphate dihydrate, 16.66 mg zinc sulfate, 50 mg talcum powder, 2 months | ↑ Immune functions that constitute the Immunity Clock ↓ Biological age by 11 years ↓ Oxidative-inflammatory state |

↓ Biological age ↑ Phagocytic index and efficacy ↑ Neutrophil and lymphocyte chemotaxis ↑ Lymphoproliferation in response to phytohemagglutinin and lipopolysaccharide ↑ Antioxidant activities of glutathione reductase and peroxidase ↓ Concentration of oxidized glutathione ↓ Oxidative lipid damage (TBARs) (94) |

| N = 5 (20-40 y), healthy men | Pilot dose-escalation study |

Low dose: 5 mg spermidine, 250 mg nicotinamide, 300 mg PEA, 200 mg OEA; medium dose: 2×, high dose: 3×; 1 week per dose arm, 1-week washouts, total 4 weeks. | ↓ Inflammation ↓ Oxidative stress |

↓ TNF-α concentration ↓ ROS (95) |

| N = 40 (52.9 ± 7.8 y), peri-implant mucositis |

Superiority, parallel arm, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial | Single application of gel A (spermidine, sodium alginate, sodium hyaluronate) followed by gel B (calcium chloride), assessments at 1 and 3 months | Non-significant results in healing of implant mucositis | 85% with spermidine and 70% of control implants resulted in disease resolution (98) |

| Samples (over 500,000 participants from UK Biobank datasets) | Bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis |

No treatment; spermidine blood levels measured | ↓ Risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases | ↓ Risk of hypertension ↓ Risk of elevated blood glucose ↓ LDL-C, HDL-C (96) |

| 8299 European individuals | Bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis |

No treatment; spermidine blood levels measured | ↓ Risk of gastric cancer | (97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).