1. Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) constitutes approximately 15% of all lung cancer cases and remains a formidable challenge due to its aggressive behavior and strong association with tobacco smoking [

1]. Despite initial responsiveness to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, SCLC often recurs quickly, leading to a particularly low five-year survival rate. Until recently, standard treatments had remained largely unchanged for decades, and while they offer temporary control, the rapid development of treatment resistance is a persistent obstacle [

2] Novel strategies such as incorporation of immunotherapy into the first-line management of both LS and ES-SCLC have markedly enhanced survival as compared to the chemotherapy-based strategies used for decades. This review seeks to provide a comprehensive update on current management and the future directions in the multidisciplinary management of patients with SCLC. Through these advancements, there is potential to transform patient outcomes and address the substantial unmet needs in the management of this aggressive disease.

1.1. Epidemiology of SCLC

The incidence of small cell lung cancer has been declining globally in recent years, primarily due to reductions in smoking rates [

3]. . However, this is not seen uniformly across the globe or genders. In North America and most countries there has been a decline in smoking prevalence and SCLC incidence in males except for countries in eastern Europe, People’s Republic of China, Southeast Asia and Latin American Countries. Females on the other hand, have higher smoking prevalence and SCLC incidence in north America, western Europe and Latin America than the rest of the world. The age adjusted incidence of SCLC in males has been at a steady decline with an annual change of 3.4% since 1998. Females experienced a much slower decline with annual rate of 1.3% between 2000-2007, and since 2007 the decline in rate increased to 2.8% annually [

4]

However, SCLC continues to account for a significant portion of lung cancer-related deaths. SCLC predominantly affects older adults with a history of heavy smoking and is characterized by rapid tumor growth and early metastasis. The disease tends to progress swiftly, often metastasizing by the time of diagnosis, which contributes to its poor prognosis.

Understanding the epidemiological trends of SCLC is crucial for developing targeted therapy [

2], prevention, screening, and treatment strategies, particularly in populations at high risk. While efforts to reduce smoking have contributed to lowering SCLC incidence, the ongoing burden of the disease in smokers and former smokers underscores the importance of ongoing public health initiatives and advances in treatment.

1.2. Staging of SCLC

Staging is critical for determining prognosis and selecting appropriate treatment strategies. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system and the Veterans Administration Lung Study Group (VALSG) classification are both used for SCLC staging. The AJCC system employs the Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) classification also used for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), while the VALSG categorizes SCLC into two main stages: limited-stage (LS-SCLC) and extensive-stage (ES-SCLC) [

5]. Notably, the criteria for classifying SCLC into these two categories differ slightly between the VALSG and the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) guidelines, with the IASLC including patients without distant metastasis in the limited-stage category, thereby potentially influencing treatment approaches and individual outcomes [

6]

LS-SCLC is confined to one hemithorax and may involve regional lymph nodes, including mediastinal, ipsilateral supraclavicular, or hilar nodes, but does not extend beyond what can be treated within a tolerable thoracic radiation plan. This stage represents approximately 30% of cases and is potentially curable with aggressive multimodal treatment, including chemotherapy and concurrent thoracic radiotherapy. Recent updates by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) further advocate the use of the TNM staging system for SCLC, aligning it with updates proposed in the eighth edition of the TNM classification, which enables more precise prognostication by refining T, N, and M descriptors [

7].

ES-SCLC accounts for the remaining 70% of cases and indicates disease that is not amenable to a tolerable thoracic radiation field. This includes distant metastases to sites such as the liver, bones, brain, and contralateral lung or distant lymph nodes. ES-SCLC has a poorer prognosis, and treatment primarily focuses on systemic therapy, typically involving platinum-based chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy, aimed at extending survival and managing symptoms [

8] .

Advancements in imaging techniques, including whole body fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)-computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, have improved the precision of SCLC staging, allowing for better differentiation between LS-SCLC and ES-SCLC [

9] .

In addition, the use of the TNM classification has gained traction, particularly in clinical trial settings, as it provides more detailed information on tumor burden, lymph node involvement, and metastasis, which is essential for assessing treatment response and outcomes [

10] .

1.3. Challenges in Treating SCLC

SCLC poses significant challenges in terms of both treatment and management. The aggressive nature of the disease, coupled with its high proliferation rate, means that many patients are diagnosed at advanced stages where curative options are limited. While the initial response to standard treatments, such as platinum-based chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy, is often favorable, relapse is common and typically occurs within months. Following recurrence, SCLC becomes more resistant to further treatment, and survival rates drop dramatically. Moreover, SCLC has shown a limited response to targeted therapies that have revolutionized the treatment of other cancers. The disease’s genetic heterogeneity, rapid mutation rates, and early development of treatment resistance make it difficult to identify and develop effective long-term therapies. These challenges highlight the urgent need for new therapeutic approaches that can extend survival and improve the quality of life for patients with SCLC [

2].

1.4. Review Objectives

This review aims to critically assess the most recent advances in systemic therapy for SCLC, focusing on emerging personalized therapeutic approaches and innovative treatment modalities. By synthesizing the latest evidence, we seek to highlight new therapeutic opportunities that hold the potential to improve patient outcomes. Additionally, this review will identify critical knowledge gaps and propose directions for future research that could inform clinical practice and lead to the development of more effective treatments. Specifically, we will explore the role of biomarkers in predicting response to therapy, assess the impact of immunotherapy and targeted therapies, and discuss the potential for combining novel agents to overcome resistance and extend survival in SCLC patients.

2. Current Status of Limited Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer (LS-SCLC)

2.1. Impact of Lung Cancer Screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends annual low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening for lung cancer in individuals aged 50 to 80 years with a 20 pack-year smoking history, an update from their previous recommendation for those aged 55 to 80 with a 30 pack-year history [

11]. Although LDCT has shown promise in detecting NSCLC at earlier stages, its effectiveness in improving SCLC outcomes remains limited [

12,

13].

Previous trials reported that the proportion of SCLC cases detected through LDCT ranged from only 0.7% to 15% of all lung cancer cases, with an incidence rate between 22 and 97 per 100,000 person-years [

13] . Research, including findings from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), further highlights this limitation. In the NLST, 86% of SCLC cases detected through LDCT were diagnosed at stage III or IV, compared to only 36% of NSCLC cases [

12] . Consequently, survival outcomes for SCLC remained poor; among those detected, three-year cancer-specific survival was 15.3%, only marginally higher than the 12.8% observed in unscreened patients [

13]

. . Additionally, Silva et al. found that even when SCLC was detected early through LDCT, survival outcomes did not significantly improve, with no survivors at three years post-diagnosis [

13]

. . The sensitivity of LDCT for early-stage SCLC is notably lower compared to other types of lung cancer, with detection rates of 8.8% for stage IA SCLC, compared to 56.6% for adenocarcinoma and 31.0% for squamous cell carcinoma [

14].Despite the potential of LDCT to identify LS-SCLC earlier, its current application does not substantially alter survival statistics, which is further hampered by low uptake of LDCT and various clinical and socioeconomic barriers [

15,

16,

18]. Low survival rates and the high proportion of late-stage diagnoses underscore the urgent need for innovative screening methods and advanced therapeutic interventions to detect and treat SCLC at earlier stages. With the addition of consolidation immunotherapy (IO) to standard treatments, there is hope that therapeutic outcomes for LS-SCLC may become more favorable.

2.2. Current Standard of Care in LS-SCLC

The standard treatment for most LS-SCLC patients currently is thoracic radiotherapy (RT) with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy, followed by consolidation IO [

17,

18,

19] in addition to PCI versus consideration for cranial MRI Surveillance. Current data showed significant benefit with consolidation durvalumab versus placebo leading to the improvement of median overall survival from 55.9 months [95% confidence interval {CI}, 37.3 to not reached] vs. 33.4 months [95% CI, 25.5 to 39.9]; hazard ratio for death, 0.73; 98.321% CI, 0.54 to 0.98; P=0.01), as well as to significantly longer progression-free survival (median 16.6 months [95% CI, 10.2 to 28.2] vs. 9.2 months [95% CI, 7.4 to 12.9]; hazard ratio for progression or death, 0.76; 97.195% CI, 0.59 to 0.98; P=0.02). LS-SCLC accounts for approximately 30% of SCLC diagnoses and the prognosis remains poor despite curative-intent treatment with standard-of-care concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT). Though most patients with LS-SCLC have an initial response to chemoradiation, recurrence and metastatic disease are common, with five-year OS approximately 30% [

18,

19,

21].

2.3. Multimodal Treatment Approaches

2.3.1. Role of Surgery

The aggressive nature of SCLC has traditionally limited the use of surgical intervention in its treatment [

22]. Standard care has focused on platinum-based chemotherapy (CT), thoracic RT, and prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) [

23,

24,

25] . Older randomized trials, conducted over two decades ago, supported this non-surgical approach by showing no significant survival advantage with surgery; however, these studies are now viewed as outdated and biased by modern standards [

26,

27,

28] . Recent advances in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques have led to renewed discussions on the potential benefits of surgery, especially for early-stage (T1-2, node negative) patients [

23,

29].

Recent retrospective studies and cancer registries indicate that surgical resection, when combined with modern CT, may benefit select patients with early-stage SCLC [

23,

29]. Specifically, emerging evidence suggests that surgery, particularly in stage I SCLC, can offer improved survival outcomes when incorporated into a multimodality treatment approach when followed by systemic therapy. For instance, lobectomy, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, may enhance survival rates in patients with very limited disease [

30]. JCOG9101 was a single arm, prospective phase II trial enrolling 42 patients treated with complete resection for stage I-IIIA LS-SCLC followed by 4 cycles cisplatin/etoposide. The investigators found a 3-year OS of 68% for stage I patients, but only 13% for stage IIIA patients, suggesting that surgical approaches should be reserved for node negative, early-stage patients [

31]. No randomized trials comparing surgical to non-surgical management have been completed in LS-SCLC. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Lung Cancer Staging Project analyzed 349 cases of early-stage SCLC managed with resection, reporting 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of 48%, 39%, and 15% for stages I, II, and III, respectively [

32]. A SEER database analysis identified a 5-year OS of 50.3% in 247 resected stage I cases [

33]. Additionally, Yang et al. found that 1,574 patients from the National Cancer Database who underwent complete R0 resection had a 5-year survival rate of 47%, consistent with other studies reporting a 5-year survival range of 37–76% for resected stage I SCLC [

34,

35]. Guidelines still recommend a non-surgical approach for most LS-SCLC due to its metastatic potential, advocating concurrent CRT, with surgery followed by chemotherapy reserved for highly localized cases without lymph node involvement or distant metastases [

36,

37,

38]. However, these findings underscore that, for early-stage disease, surgery, particularly when paired with chemotherapy, may offer survival benefits when used in a carefully selected patient population [

33,

39] .

2.3.2. Advances in Concomitant Radiation Therapy

Thoracic radiation with concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy is the standard of care for all but the earliest stage LS-SCLC patients. In 1999, publication of a landmark Intergroup trial demonstrated the superiority of a regimen of 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy twice daily (BID) fractions as compared to once daily 1.8 Gy fraction [

40]. Among 417 randomized patients, median survival was 19 months for the once daily group and 23 months for patients treated with twice daily radiation. Grade 3 esophagitis was higher with BID treatment (27% versus 11%, p<0.001). Despite the compelling survival benefit to BID radiation, clinical implementation in the United States has been modest, with the majority of patients receiving once daily radiation schedules [

41].

The selection of 45 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions as the daily radiation arm was a major criticism of the Intergroup Trial. Subsequently, two large trials compared higher dose once daily radiation to 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID. The CONVERT trial randomized 547 patients with LS-SCLC between the Intergroup regimen of 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID fractions and a daily schedule of 66 Gy over 33 daily fractions of 2 Gy each [

42]. The study was designed to detect a 12% improvement in overall survival with the once-daily regimen. Median overall survival was 30 months in the BID group and 25 months in the once daily group (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.95-1.45; p=0.14). The study did not meet the primary endpoint of demonstrating superior overall survival with higher dose once daily radiation, and the authors concluded that twice daily radiation remained the standard of care. Contemporaneously, CALGB 30610/RTOG 0538 randomized 638 evaluable LS-SCLC patients between three radiation schedules: 70 Gy in 35 fractions of 2 Gy each, 61.2 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions with a concomitant boost i.e., twice daily for the final nine treatment days, and 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID fractions [

19]. The trial was powered to detect an improvement in median survival from 23 months with BID radiation to 29.9 months in one of the experimental arms. Following a planned interim analysis, the concomitant boost arm was closed, and randomization continued between the daily and BID arms. At a median follow up of 4.7 years, median OS was 28.5 months for the BID arm and 30.1 months for the daily radiation arm (p=0.498), failing to meet the trial’s primary endpoint of improved OS with once daily radiation.

With two large, randomized phase 3 trials failing to demonstrate a benefit to higher dose, once daily radiation as compared to 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID fractions, interest has been renewed in alternate, dose escalated twice daily schedules. Gronberg et al conducted a randomized phase 2 comparison of 45 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID fractions to 60 Gy in 1.5 Gy BID fractions [

42] . 176 patients were randomized. With 49 months median follow-up, two-year OS was 74.2% in the 60 Gy arm and 48.1% in the 45 Gy arm (OR 3.09; 95% CI 1.62-5.89; p=0.0005). The very promising results suggest that a confirmatory randomized phase 3 trial should be conducted.

Over the past two decades, technological advances in radiation therapy have also improved the targeting of tumors and sparing of critical structures, reducing the toxicity of thoracic radiation. The introduction of intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) allows the sculpting of radiation dose around concave and convex structures. Retrospective cohort studies suggest use of IMRT for LS-SCLC reduces toxicity as compared to three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy [

43] . . The availability of better pre-treatment staging imaging and the widespread use of IMRT have led to adoption of the approach of treating only involved nodes, without elective irradiation of uninvolved mediastinal nodal regions. This reduction in target volume has been demonstrated to reduce toxicity without compromising local/regional disease control [

43,

44].

2.4. Future of Consolidation Therapies in LS-SCLC

The longstanding standard treatment for LS-SCLC involves the combination of cisplatin and etoposide as detailed above administered concurrently with thoracic radiation therapy. Despite numerous clinical trials exploring novel agents and alternative radiation schedules, this approach remains the gold standard, as noted by Noronha et al., with ongoing research aimed at enhancing treatment efficacy while reducing toxicity [

45].

With standard concurrent chemoradiotherapy, the median overall survival is 25 to 30 months, and 5-year overall survival is 29 to 34% [

11], [

45]

-[

49] . The ADRIATIC trial compared consolidation durvalumab to durvalumab/tremelimumab to placebo as consolidation therapy for up to 24 months following CRT. An interim analysis demonstrated an overall survival benefit at 3 years of 56.5% with adjuvant durvalumab therapy, while the durvalumab/tremelimumab arm remained blinded. In contrast, the 3-year overall survival was 47.6% in the placebo group, and the median overall survival was 33.4 months, which exceeded that reported in previous phase 3 trials [

18,

20,

42,

50]. Following publication of the ADRIATIC trial, consolidation durvalumab has been incorporated into guidelines for treatment of LS-SCLC as a standard treatment [

51].

In contrast to the ADRIATIC trial, concurrent treatment with atezolizumab and chemoradiotherapy did not improve survival rates compared with standard care. NRG LU-005 randomized patient with LS-SCLC to either concurrent chemoradiation with concurrent and consolidation atezolizumab Q3 week for up to 1 year. After 1-year, overall survival for patients receiving chemoradiation alone was 82.6%, compared with 80.2% with concurrent chemoradiation and atezolizumab. Two years after treatment, the rates were 62.9% and 58.6%, respectively, and after 3 years, they were 50.3% and 44.7%. Median overall survival for patients on the standard treatment arm was 39.5 months, compared with 33.1 months for those who also received immunotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.1, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 11.3–18.2) [

52]. The lack of survival benefit when giving immunotherapy concomitantly with chemoradiotherapy, rather than following chemoradiation, indicates a possible reduced benefit of immunotherapy when administered concomitantly with thoracic radiation. Similar findings have been noted in locally advanced, unresectable NSCLC. This phenomena is not fully understood, but suggests a possible immunologic interplay between radiation to often large nodal volumes and the timing of immunotherapy.

2.5. Smoking Cessation and Supportive Care

Smoking cessation is a crucial component in managing SCLC, as it significantly influences treatment outcomes and OS. Continuing to smoke after an SCLC diagnosis is linked to worse outcomes, including increased recurrence rates, lower tolerance to treatment, and reduced survival [

53]

-[

56]. Quitting smoking not only lowers the risk of developing additional malignancies but also improves the effectiveness of treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [

53]

-[

56]. Furthermore, supportive care measures like nutritional support and symptom management are integral to a comprehensive care plan, enhancing patient well-being and adherence to treatment protocols [

57]. Studies demonstrate the substantial survival benefits of quitting smoking at the time of, or shortly after, an SCLC diagnosis. For instance, Chen et al. reported that patients who quit smoking at or after diagnosis reduced their mortality risk by 45%, regardless of treatment timing [

58].

A meta-analysis by Caini et al. supports these findings, indicating a significantly improved OS in patients who quit smoking compared to those who continued [

58,

59]. This evidence suggests that smoking cessation should be a critical, integrated component of treatment plans. [

60]

-[

62] .

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of lung cancer (LC) cases, including both SCLC and NSCLC, consistently highlight the survival advantages linked with smoking cessation. A meta-analysis covering over 10,000 lung cancer patients showed that quitting smoking at or around diagnosis correlates with a marked reduction in mortality rates across different cancer subtypes [

53,

58]. Such findings reinforce the necessity of incorporating structured smoking cessation programs into the care of SCLC patients. Physicians should proactively promote smoking cessation, providing the necessary resources and support to help patients quit and maintain abstinence, ultimately enhancing treatment outcomes and prolonging survival [

53,

60]

-[

62].

3. Current Status of Extensive Stage SCLC (ES-SCLC)

3.1. Current First-Line Systemic Therapy

Current first-line systemic therapy for ES-SCLC has evolved from the long-standing use of platinum-based chemotherapy combined with etoposide, a regimen that has demonstrated high initial response rates between 60–80% but is often followed by rapid disease progression [

56,

61,

62].Historically, the median OS for patients receiving this regimen has been approximately 10 months, with fewer than 15% of patients surviving beyond two years [

63,

64] Carboplatin, due to its favorable toxicity profile, is now more commonly used than cisplatin in clinical practice [

62,

65] .Historically, CAV has been used as initial therapy[

66], however this has not been in use currently due to the toxicity profile of this triplet therapy.

3.2. Concurrent, Maintenance and Consolidation Immunotherapy for ES-SCLC

IMpower133 and CASPIAN demonstrated that incorporating ICIs into the first-line treatment improves overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone, with median OS increasing to approximately 12–13 months [

63,

67]

-[

69]. Notably, the benefits of adding ICIs appear consistent regardless of whether carboplatin or cisplatin is used, and their safety profile remains manageable, with immune-related adverse events ranging from 20% to 40%. This chemoimmunotherapy approach has shown promise in extending survival outcomes, marking a significant advance in the management of ES-SCLC [

63,

67]

-[

69].

In ES-SCLC, the maintenance approach has been explored extensively, yet studies have consistently shown limited overall survival benefits, even when immunotherapy is incorporated. The 22.5 month increased in OS noted on the ADRIATIC trial in LS-SCLC markedly exceeds the 2.7-month median OS benefit noted on the CASPIAN trial in ES-SCLC. This suggests that immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may be more beneficial when applied early in the disease course rather than in later stages, such as ES-SCLC [

67]

-[

69]. The improved outcomes in LS-SCLC may be attributable to a higher prevalence of the SCLC-I subtype, which appears more responsive to ICIs [

70,

71].

The minimal clinical impact observed suggests that a substantial benefit might be confined to a small subset of patients. For instance, combination therapies, such as tiragolumab with atezolizumab and chemotherapy, have not succeeded in reaching primary endpoints in interim analyses [

72]. IMforte, a multicenter phase III study of maintenance therapy in ES-SCLC with lurbinectedin plus atezolizumab compared with atezolizumab alone after first-line induction with carboplatin, etoposide and atezolizumab is still accruing patients [

73]. A recent topline finding from the ongoing phase 3 IMforte trial revealed that combination of lurbinectedin, an inhibitor of DNA transcription factors and repair pathways, and atezolizumab produced statistically significant overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) benefits vs atezolizumab monotherapy. The addition of ICIs, specifically anti-PD-L1 agents such as atezolizumab or durvalumab, to the standard platinum-based chemotherapy has shifted the treatment paradigm, becoming the new standard of care [

63,

67]

-[

69].

3.3. Role of Radiation Therapy in ES-SCLC

3.3.1. The Status of Consolidation Radiation Therapy

Many investigators have noted that uncontrolled thoracic disease in ES-SCLC often leads to morbidity and mortality and have hypothesized that thoracic radiation may improve outcomes. Several randomized trials have explored the benefit of consolidative thoracic radiation therapy following frontline chemotherapy for ES-SCLC. Jeremic et al enrolled 210 patients with ES-SCLC. All patients received three cycles of platinum/etoposide. 109 patients with a complete response in the chest and at least a partial response at distant sites were randomized between consolidative thoracic radiation to 54 Gy in 36 fractions over 18 days with concurrent chemotherapy versus four additional chemotherapy cycles alone. The median survival with thoracic radiation was improved (17 versus 11 months) as was the 5-year OS (9.1% versus 3.7%; p=0.041) [

74] . More recently, a large European trial randomized 498 patients with ES-SCLC between consolidative thoracic radiation to 30 Gy in 10 daily fractions or no thoracic radiation [

75]. Although the study did not meet the primary endpoint of demonstrating an improvement in one-year OS, 2-year OS favored the thoracic radiation group (13% versus 3%; p=0.004). RTOG 0937 was a randomized phase II trial that compared consolidative radiation to both intrathoracic and residual extrathoracic disease [

76]. . Both arms received PCI. Ninety-seven patients were enrolled and randomized before the study was closed after an interim analysis suggested futility. OS was similar between the two arms (60.1% versus 50.8%), while time to progression favored the use of radiation (HR 0.53; 95% CI: 0.32-0.87; p=0.01).

All three trials were conducted prior to the use of front line chemoimmunotherapy. In the immunotherapy era, the RAPTOR phase II/III trial (NCT04402788) randomizes patients with ES-SCLC and stable disease or a partial response following 4-6 cycles platinum/etoposide/atezolizumab to either atezolizumab maintenance alone or atezolizumab with consolidative radiation to both thoracic and extra-thoracic sites of residual disease. The study is currently accruing. Currently, the use of consolidative thoracic radiation with immunotherapy is somewhat controversial.

3.4. Why and how personalized therapies may be useful

3.4.1. SLFN11

Schlafen 11 (SLFN11), a putative DNA/RNA helicase that induces irreversible replication block, is emerging as an important regulator of cellular response to DNA damage [

81]. SLFN11 has been associated with sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, and its expression may identify patients who could benefit from therapies like poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors [

78]. . The phase II clinical trial NCT04334941 investigated whether adding talazoparib, a PARP inhibitor, to atezolizumab as maintenance therapy can enhance PFS in patients with SLFN11-positive ES-SCLC compared to atezolizumab alone. By targeting DNA damage repair mechanisms specifically in SLFN11-positive tumors, the trial aims to boost the efficacy of immunotherapy and delay disease progression, potentially offering a new maintenance strategy for this patient subgroup[

78]. The SWOG S1929 trial demonstrated that SLFN11 can be a predictive biomarker for improved PFS in patients with ES-SCLC receiving maintenance therapy with a combination of atezolizumab and talazoparib[

78] . This study highlights the growing impact of biomarker-driven treatment strategies in SCLC, especially SLFN11's role in identifying patients who may benefit from the addition of PARP inhibitors to immune checkpoint inhibitors [

79]. However, these findings require further validation through larger, prospective clinical trials [

80]. S1929 study met its primary endpoint; however, with a modest difference [

85]. , implicating the need to further develop both the predictive biomarker and the currently available targeted therapies.

3.4.2. DLL3

DLL3, a ligand involved in Notch signaling, is commonly found in SCLC cells. Research indicates that elevated DLL3 levels contribute to the growth and spread of SCLC cells, with a connection to the neuroendocrine system[

82] .

DLL3, is expressed in neuroendocrine cells and has limited expression in normal tissues, is a target for emerging therapies, including antibody-drug conjugates and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies[

83] . However, currently approved DLL3 targeted therapy is approved for SCLC in the relapsed or refractory status regardless of their DLL3 status.

3.4.3. Molecular Subtypes and Treatment Implications

Molecular profiling has identified distinct SCLC subtypes based on the expression levels of key transcription factors, including ASCL1 (SCLC-A), NEUROD1 (SCLC-N), POU2F3 (SCLC-P), and YAP1 (SCLC-Y) [

80,

84] . Each subtype is characterized by unique biological and clinical traits, with ASCL1 and NEUROD1 subtypes generally exhibiting higher neuroendocrine features, while POU2F3 and YAP1 subtypes show lower neuroendocrine differentiation, often correlating with aggressive or treatment-resistant forms of SCLC [

84]

-[

86]. These subtypes have become a focus of research as they provide insights into SCLC’s diverse tumor biology, suggesting that personalized therapeutic approaches could be developed based on transcriptional profiles [

80]. Others describe I (inflammatory subtype) [

87]. However the clinical implications of either the YAP subtype or the I subtype is yet to be established through prospective clinical trials.

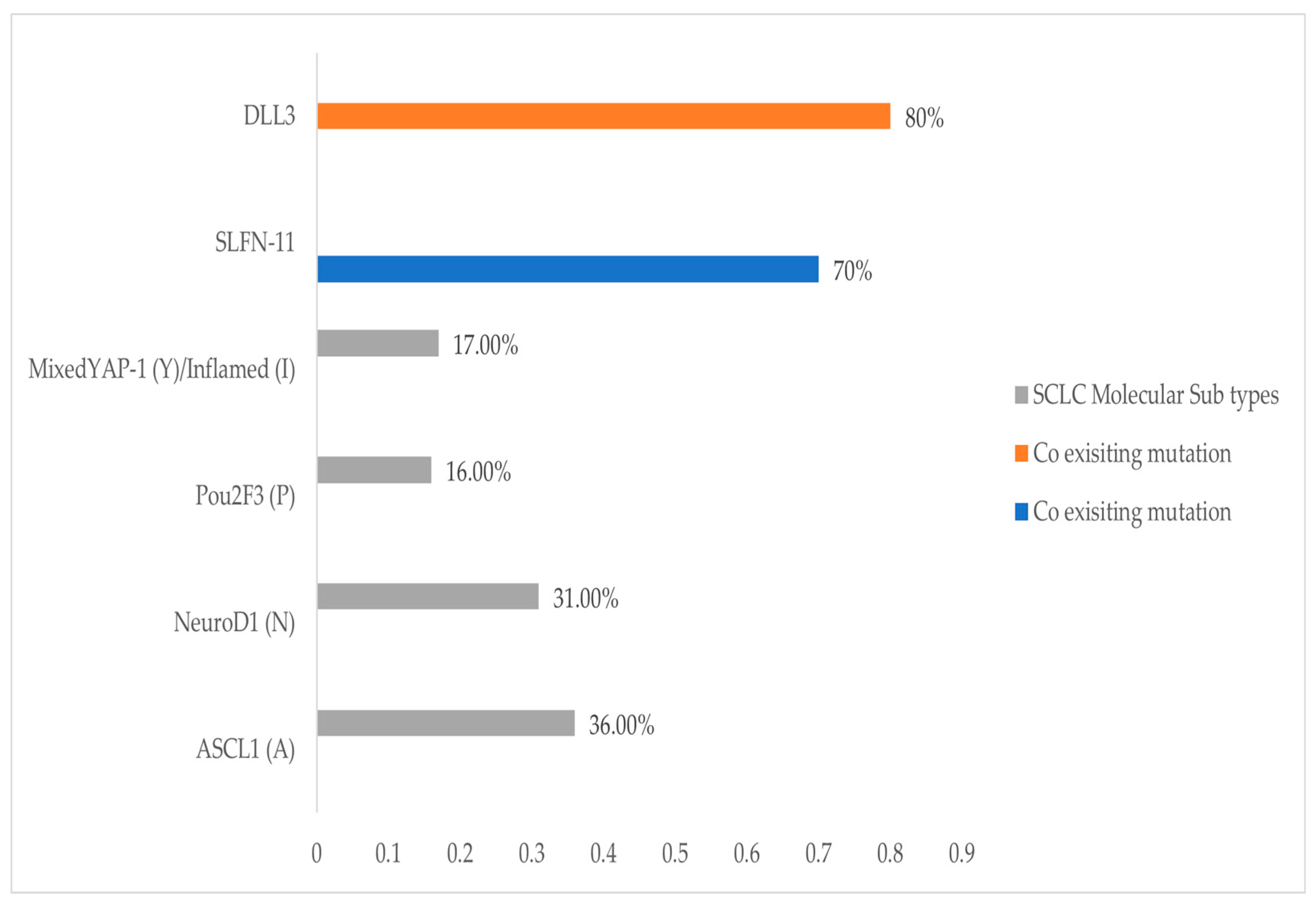

Figure 1 describes a preliminary distribution of the SCLC subtypes in relevance to SLFN11 and DLL3, where more correlative studies are needed.

Figure 1).

The SCLC-A and SCLC-N subtypes, which are neuroendocrine (NE) in nature, tend to express neuroendocrine markers such as TTF-1 and DLL3. These subtypes are generally more responsive to conventional chemotherapy and targeted agents like BCL2 or DLL3 inhibitor [

80], [

88,

89]. In contrast, SCLC-P and SCLC-Y, which are non-neuroendocrine (non-NE) variants, exhibit increased immune infiltration, making them more suitable for immune checkpoint inhibitors [

89,

90].

Recent studies highlight that the non-NE subtypes, particularly SCLC-Y, benefit from Aurora kinase inhibitors when MYC amplification is present [

90]. This reflects a shift in treatment strategies, emphasizing the importance of integrating molecular subtyping to refine therapy. Moreover, SCLC-P, characterized by the expression of POU2F3, shows sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, which align with its distinct signaling pathways involving ASCL2 and MYC [

89,

90]. This precision-targeted approach is crucial as it enables personalized treatment regimens that align with the molecular and genetic landscape of each subtype [

88,

90]. . Furthermore, the recognition of these molecular subtypes has implications for ongoing and future clinical trials, particularly in exploring combination therapies. For example, the SCLC-IM subtype, which lacks ASCL1, NEUROD1, and POU2F3 expression, demonstrates high immune infiltration and thus may derive significant benefit from immunotherapies, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors like PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [

89,

90]. Additionally, combination approaches that incorporate novel agents, like immune checkpoint inhibitors and DDR inhibitors, are under investigation to enhance therapeutic efficacy and overcome resistance mechanisms [

83,

91]. These personalized and combinatory strategies reflect a more refined approach to SCLC management, aiming to address the genetic complexity and adaptability of the disease [

91,

92].

However, the heterogeneity and plasticity of these molecular subtypes, as demonstrated by single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies, indicate that these biomarkers may not be uniformly predictive across all SCLC cases [

84,

85]. This molecular heterogeneity underscores the need for further research to optimize subtype-specific treatment protocols, ultimately aiming to improve patient outcomes [

90].

3.4.4. Molecular Biomarkers

ES-SCLC poses significant challenges in the identification of effective predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy. Traditional biomarkers, such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutation burden (TMB), have shown limited success in predicting outcomes for ES-SCLC patients. For instance, clinical trials like IMpower133 and CASPIAN demonstrated that PD-L1 expression, which is a reliable predictor in NSCLC, does not accurately correlate with improved survival in ES-SCLC patients treated with ICI. [

63], [

64,

67,

68].

The low PD-L1 expression rates in SCLC cells, along with the non-mandatory biopsy procedures in these studies, have contributed to these inconclusive results [

93]. Similarly, TMB, both tissue-based (tTMB) and blood-based (bTMB), has been found to be an inconsistent predictor, possibly due to the influence of chemotherapy on TMB values [

94]. Despite these limitations, there is growing interest in molecular subtypes based on transcription factors such as ASCL1, NEUROD1, and POU2F3, which show potential in identifying patient populations that may respond better to immunotherapy [

80].

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a promising molecular biomarker in ES-SCLC, offering a non-invasive alternative to tissue biopsies for monitoring disease progression and therapeutic response [

95]. Studies have shown that ctDNA has a higher positivity rate in SCLC compared to other cancers, making it a valuable tool for assessing dynamic changes in tumor burden[

96] . For instance, ctDNA dynamics have been correlated with OS and PFS outcomes, suggesting that patients exhibiting a molecular response, characterized by the complete elimination of ctDNA, tend to have better clinical outcomes [

104]. Additionally, ctDNA could be integrated with other biomarkers, such as TMB, to enhance predictive accuracy[

98]. This combined approach may improve the identification of patients who are more likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors. Despite its potential, the application of ctDNA as a predictive tool in clinical practice for SCLC remains under-explored and necessitates further research through larger, well-structured clinical studies to confirm its efficacy and optimize its usage in patient stratification[

99] .

Liquid biopsies are an emerging minimally invasive strategy for diagnosis, monitoring therapeutic efficacy, and guiding therapy. Liquid biopsy approaches include detection and monitoring of circulating tumor cells, cfDNA, ctDNA, and extracellular vesicles [

100] . CtDNA show promise in monitoring disease progression and efficacy of therapeutics. Different miRNAs has been shown to have tumor suppression or promoting effect that allow for a great potential for development and monitoring efficacy. The optimal use of many of these liquid biopsy strategies remains poorly understood in the context of SCLC and additional studies are needed [

101,

102].

The role of microRNAs (miRNA) is an emerging field in understanding SCLC and in developing new therapeutics. MiRNA are non-coding RNA and play a critical role in various stages of disease. They are known regulators of epigenetic control of either oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. They play important roles in the tumor microenvironment through modulation, metastasis, angiogenesis, metabolism and apoptosis. As a result they could serve role in diagnostic, prognostics, and in therapeutics. MicroRNA 1 (miR-1) is an example of miRNA that was detected in patient serum samples with promising therapeutic role. MiR-1 is down regulated in tumor tissue samples when compared to control. In addition, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown gain of function of miR-1 results in decreased cell growth in SCLC lines, and decreased distant organ metastasis in mouse models. On the contrary, loss of function potentiated cell growth and distant metastasis. By targeting CXCR4/FOXM1/RRM2 axis, miR-1 has a high potential of developing new SCLC therapeutics. Other tumor suppressor miRs that could play a role in novel therapeutic strategies include miR17a, miR184, and miR5745p. miR1827 is an example of tumor promoting miR, which could possibly be another avenue for targeted therapy 08,[

101,

103].

A recent study that explores SCLC biology showed that the primary genetic changes involved the inactivation of TP53 and RB1. A proteogenomic analysis enabled us to examine the immune environment of SCLC, revealing that increased DDR activity could contribute to immune suppression by diminishing the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. Clinical evidence suggested that ZFHX3 mutations might serve as a potential predictive biomarker for SCLC patients undergoing immunotherapy. Additionally, we found that NMF4 subtype tumors were more responsive to alisertib. This study advances the comprehension of SCLC cancer biology beyond what genomic analysis alone can reveal and identifies subtypes that could inform precision medicine approaches. The overexpression of HMGB3 enhanced the migration of SCLC cells by modulating the transcription of genes associated with cell junctions[

104].

These newly identified subgroups are most clearly characterized in SCLC, a disease once considered a single biological entity but now recognized as highly heterogeneous. Advancing targeted treatments will require a thorough understanding of the unique biological drivers within each subgroup [

105].

3.5. The Role of Prophylactic Cranial Radiation

Small cell lung cancer has a high propensity for development of brain metastases [

106,

107]. As a result, many studies have sought to reduce that risk by delivering prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI). A meta-analysis published in 1999 including individual data for 987 SCLC patients concluded that use of PCI conferred a 5.4% increase in 3-year OS [

24]. Both LS-SCLC and ES-SCLC patients were included in the analysis. Based on that result, PCI became a standard of care option for SCLC patients. Due to concerns around the potential cognitive side effects of PCI, however, considerable interest has remained in identifying more precisely which patients benefit and exploring alternative strategies.

Two large, randomized phase 3 trials conducted in ES-SCLC have resulted in conflicting results around the benefits of PCI. EORTC 22993 randomized 286 patients with ES-SCLC and any response to 4-6 cycles front line chemotherapy [

108]. Importantly, brain MRI was not mandated for staging. The 1-year OS favored the PCI arm at 27.1% (95% CI 19.4-35.5) as compared to 13.3% (95% CI 8.1-19.9) in the control arm. However, a more recent randomized trial in ES-SCLC conducted in Japan suggested that the use of staging and surveillance brain MRI negated the benefit of PCI [

109]. Takahashi and colleagues randomized 224 patients with ES-SCLC to either PCI or MRI surveillance. The study required a re-staging brain MRI following frontline chemotherapy prior to enrollment. The study closed following a planned interim analysis suggesting futility. Median OS was 11.6 months for the PCI arm and 13.7 months for the MRI surveillance arm. A recent meta-analysis of both LS-SCLC and ES-SCLC patients published in 2023 also suggested that the benefit of PCI was limited to patients without MRI staging, suggesting a therapeutic rather than prophylactic benefit [

110]. Currently, the role of PCI for SCLC remains controversial. An ongoing randomized phase 3 trial, MAVERICK/SWOG S1827 is randomizing between PCI and MRI surveillance in both LS-SCLC and ES-SCLC (NCT04155034).

Other efforts have focused on reducing the toxicity of PCI with hippocampal sparing using IMRT. The PREMOR trial randomized 150 patients (71.3% LS-SCLC) between standard PCI or hippocampal avoidance PCI [

111]. The investigators found that sparing the hippocampus resulted in less decline in delayed free recall as compared to standard PCI (5.8% versus 23.5%; p=0.003). Other metrics of cognitive function were also improved with hippocampal avoidance, while OS, quality of life, and brain failure were similar between the two arms.

3.6. Second Line Therapeutic Options:

Approved second line and salvage therapies for ES-SCLC have shown modest efficacy, with a need for more effective treatment options.

Tarlatamab, a recently FDA-approved second-line therapy, demonstrated promising results in a phase II study, particularly for patients with previously treated brain metastases, where it showed favorable control [

112,

113,

114].

Lurbinectedin, specifically approved for relapsed ES-SCLC, has shown a median overall survival of 5.1 months in second-line therapy and 5.6 months in later lines. Despite manageable adverse effects, its outcomes are less favorable in patients with shorter chemotherapy-free intervals and central nervous system metastases [

115].

Sacituzumab govitecan, targeting TROP2, has been recently FDA approved as a second line therapy for patients with SCLC following disease progression. Sacituzumab govitecan-hziy (Trodelvy) was granted breakthrough therapy designation for patients wit

h extensive-stage SCLC on 12/18/2024 based on several studies, recently the Phase 2 Open-Label Study of Sacituzumab Govitecan as Second-Line Therapy in Patients with ES-SCLC: Results From TROPiCS-03 showing ORR of 41.9% (95% CI: 27.0%-57.9%), with 18 confirmed partial responses; median (95% CI) DOR, PFS, and OS were 4.73 (3.52-6.70), 4.40 (3.81-6.11), and 13.60 (6.57-14.78) months, respectively [

116,

117,

118].

Platinum-based rechallenge has been considered for patients with relapsed SCLC who progressed after 6 months of front-line therapy. This has demonstrated superior survival outcomes compared to lurbinectedin and other platinum-free regimens in a large French multicenter study, although the overall prognosis for ES-SCLC remains poor [

119].

Irinotecan-based regimens also remain a viable option, with a response rate of 27.1% and manageable side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and myelosuppression, providing an acceptable safety profile [

120]. Irinotecan single agent has also been shown to be an effective subsequent therapy with overall response rates (ORR) range of 16-17% with one additional study reporting a 47% ORR. Likewise, median survival was similar in 3 studies at 5-6 months, but Sevinc observed an impressive 13-month OS in addition to potential activity in patients with active brain metastases[

121]

-[

125].

Other second-line therapies include Topotecan, which provides modest benefits for relapsed ES-SCLC patients. Oral topotecan has shown a survival benefit compared to best supportive care alone and has similar efficacy to the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine (CAV) regimen, offering improved symptom control but with a higher incidence of hematologic toxicity [

126,

127].

4. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Future Directions in SCLC

4.1. Advances in ES-SCLC Therapies: Immunotherapy and Targeted Treatment Advances

Emerging therapies for ES-SCLC have shown significant potential in advancing beyond traditional chemotherapy. ICIs such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab have become crucial in improving clinical outcomes for SCLC patients. For instance, the IMpower133 trial demonstrated that the addition of atezolizumab to standard chemotherapy significantly enhanced OS, setting a new standard for first-line treatment in ES-SCLC [

63]. Supporting these findings, a meta-analysis by Zheng et al. compared ICIs combined with chemotherapy (ICIs+ChT) to chemotherapy alone as a first-line option and found that ICIs+ChT significantly improved OS and PFS. However, it also increased the incidence of grade 3-5 immune-related adverse events, highlighting the balance between efficacy and toxicity associated with this approach [

128]. Similarly, lurbinectedin, a novel cytotoxic agent targeting RNA polymerase II, has shown a notable objective response rate of 39.3% in recurrent cases, earning orphan drug status from the FDA [

129] .

In addition to immunotherapy, emerging targeted therapies are demonstrating promise. Anlotinib, a multikinase inhibitor targeting pathways such as VEGFR, improved PFS in the phase II ALTER 1202 trial, extending median PFS to 4.3 months versus 0.7 months for placebo [

130]. Veliparib, a PARP inhibitor used alongside temozolomide, also displayed increased objective response rates, particularly in patients positive for the SLFN11 biomarker [

131]. The growing understanding of SCLC as a heterogeneous disease with molecular subtypes, as emphasized by Aliaga et al., further supports the development of personalized approaches [

132] . These efforts address therapeutic resistance and genetic variability, providing a foundation for integrating targeted therapies and immunotherapy with conventional treatments to optimize outcomes in ES-SCLC. Ongoing clinical trials are necessary to validate these strategies and to establish predictive biomarkers that guide patient selection and treatment customization [

133].

4.2. Clinical Trials and Investigational Agents

Participation in clinical trials is crucial for advancing therapeutic strategies in SCLC, offering patients access to innovative treatments that may not yet be available outside research settings. Improving diversity representation especially in lung cancer clinical trials is of critical need [

134].

Patients enrolled in clinical trials contribute to a growing body of knowledge, informing personalized medicine approaches based on individual tumor characteristics. Recent studies frequently focus on investigational agents targeting specific molecular pathways involved in SCLC progression, with the goal of improving survival outcomes and quality of life for patients. Such agents include immune checkpoint inhibitors, targeted therapies, and novel drug combinations designed to enhance the efficacy of existing treatment regimens or introduce entirely new approaches. By enrolling in these studies, participants contribute to a growing body of knowledge that informs the development of personalized medicine approaches, ultimately aiming to optimize therapy based on individual tumor characteristics This dynamic research environment is essential for addressing the unmet clinical needs in SCLC and identifying the next generation of therapeutic options [

135].

4.2.1. Evolving therapies in LS-SCLC

LS-SCLC has shown responsiveness to multimodal treatment approaches, including chemoradiotherapy and emerging immunotherapies. Recent actively enrolling Phase III clinical trials (

Table 1) focus on integrating novel agents into standard treatment protocols to enhance survival outcomes [

136].

Additionally, phase II clinical trial NCT06295926 is evaluating the efficacy and safety of serplulimab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, in combination with cCRT as a first-line treatment for patients with LS-SCLC [

136]. The study aims to determine PFS and OS as primary endpoints while also exploring tumor-related biomarkers to predict the response to immunotherapy. Participants receive four cycles of chemotherapy combined with thoracic radiotherapy and serplulimab, followed by up to one year of serplulimab consolidation therapy, which seeks to enhance the immune response and sustain remission [

137].

These trials highlight the ongoing efforts to incorporate novel immunotherapeutic agents into the treatment landscape for LS-SCLC, with the goal of improving long-term outcomes and addressing the aggressive nature of this disease stage.

4.2.2. Evolving therapies in ES-SCLC

ES-SCLC presents a more challenging treatment landscape due to its aggressive and widespread nature at diagnosis. Current clinical trials (

Table 2) focus on integrating targeted therapies and novel combinations to extend survival and improve quality of life for patients with ES-SCLC [

136].

These efforts underscore the importance of targeted approaches and novel maintenance therapies in improving the prognosis for patients with ES-SCLC, particularly those with specific molecular profiles that may predict better responses to such treatments.

4.3. Novel Therapeutic Approaches

4.3.1. Immunotherapy Beyond First Line

In the evolving landscape of second line (2L) treatment for ES-SCLC, the role of IO after progression on first-line chemo-immunotherapy is under active investigation. Recent evidence suggests that the efficacy of subsequent therapies is closely tied to the platinum-free interval (PFI), which serves as a predictor of response. In patients classified as "platinum-sensitive" (PFI ≥ 90 days), platinum-based rechallenge has shown significantly improved outcomes compared to platinum-free options, such as lurbinectedin or other chemotherapy regimens. For instance, platinum rechallenge has been associated with a median OS of 8.1 months compared to 4.9 months for lurbinectedin and 5.1 months for other non-platinum regimens [

119]. However, the effectiveness of lurbinectedin, a selective transcription inhibitor, when used post-IO, did not demonstrate superiority over these alternatives, suggesting that previous IO exposure might not enhance the efficacy of lurbinectedin-based therapies in this cohort [

137]. Rossi et al. summarize the state of second-line treatments for SCLC, noting that while topotecan remains the standard-of-care for platinum-sensitive cases and amrubicin is approved only in Japan, emerging immunotherapies like ipilimumab and nivolumab show promising preliminary results, with ongoing trials investigating their efficacy in relapsed SCLC [

138].

The impact of prior immunotherapy on subsequent lines of treatment remains complex, as its influence on the tumor microenvironment and response patterns, particularly in platinum-resistant cases (PFI < 90 days), is not yet fully understood. The median OS for platinum-resistant patients was significantly shorter at 5.0 months compared to 6.8 months for platinum-sensitive patients, indicating that timing from the last platinum administration remains critical for therapy selection. Additionally, exploratory analyses using a 75-day cut-off instead of the traditional 90-day threshold have shown that patients relapsing earlier may experience significantly worse outcomes, emphasizing the need for precise categorization in treatment planning. Although ongoing trials are exploring the combination of lurbinectedin with immunotherapy to potentially enhance outcomes, further studies are essential to optimize 2L strategies for patients with varying degrees of platinum sensitivity [

137]

-[

140].

4.3.2. Antibody-Drug Conjugates

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) emerging as pivotal therapies in lung cancer, particularly in SCLC, where conventional treatments often face significant limitations due to aggressive tumor behavior and rapid disease progression [

141,

142]. ADCs operate by linking a cytotoxic drug to a monoclonal antibody that targets tumor-specific antigens, allowing for precise delivery of potent chemotherapeutic agents directly to cancer cells. This approach minimizes off-target effects and enhances the therapeutic window. Prominent ADC targets in lung cancer include HER2, HER3, TROP2, CEACAM5, MET, and DLL3, with DLL3 being particularly relevant in SCLC [

143]. By focusing on these proteins, ADCs have shown improved response rates and survival outcomes, making them a promising addition to the therapeutic arsenal against lung cancer [

141].

The development of ADCs such as ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) and trastuzumab deruxtecan has demonstrated their effectiveness in targeting HER2-positive lung cancers. These compounds utilize different linker and payload mechanisms to optimize drug delivery and minimize systemic toxicity[

144]. Recent studies have shown that innovative payloads like topoisomerase inhibitors and microtubule disruptors can enhance the efficacy of ADCs while reducing adverse effects [

145]. Similarly, the incorporation of more efficient linker systems, such as protease-cleavable or acid-sensitive linkers, ensures the selective release of cytotoxic agents within tumor cells, thus improving the safety profile of these therapies [

83]

.

Sacituzumab govitecan-hziy (Trodelvy) was granted breakthrough therapy designation for patients with extensive-stage SCLC on 12/18/2024 based on the global, phase 2 TROPiCS-03 study (NCT03964727) where treatment with sacituzumab govitecan led to promising antitumor activity in both platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive disease when used as a second-line treatment for patients with ES-SCLC. In that study, investigator-assessed overall response rate was 41.9% (95% CI, 27.0%-57.9%) a median follow-up of 12.3 months (range, 8.1-20.1). All the responses were confirmed partial responses, and other best overall responses consisted of stable disease (41.9%) and progressive disease (9.3%). Among these patients, the disease control rate was 83.7% (95% CI, 69.3%-93.2%). The median duration of response was 4.7 months (95% CI, 3.5-6.7), and 48.2% of patients (95% CI, 23.9%-68.9%) continued to respond at 6 months. Additionally, the median time to response was 1.4 months (range, 1.2-4.2) [

116,

117].

Ongoing research is also focusing on enhancing the effectiveness of ADCs in SCLC by exploring novel targets like DLL3, a protein expressed on the surface of tumor-initiating cells, and TROP2, which is overexpressed in various epithelial cancers [

79,

138,

139]

.

Rovalpituzumab tesirine, targeting DLL3, another ADC undergoing clinical trials, with promising preliminary results suggesting potential improvements in patient outcomes[

146] . Moreover, advancements such as increasing the drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) and utilizing novel cytotoxic payloads are being investigated to further enhance the potency and reduce the resistance mechanisms associated with these therapies [

147].

4.4. Special Populations

4.4.1. Patients with Brain Metastases

Patients with SCLC often develop brain metastases, occurring in up to 50% of cases throughout the disease course [

148,

149]

. These metastases present significant clinical challenges due to cognitive impairment risks and the blood-brain barrier limiting the efficacy of systemic therapies [

150].

Traditionally, whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) has been the standard first-line treatment for brain metastases in SCLC, particularly in patients with ES-SCLC. More recently, hippocampal sparing IMRT has been used in well selected patients to attempt to reduce the possible neurocognitive sequelae of WBRT [

111]. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has typically been reserved as a salvage option for recurrence after WBRT. However, recent data support the safe use of SRS as a primary treatment option for many patients. The FIRE-SCLC Cohort study, which pooled data from 710 patients treated across 28 centers, demonstrated promising outcomes with SRS as a frontline treatment for brain metastases in SCLC. In this study, the median overall survival (OS) was 8.5 months, the median time to central nervous system (CNS) progression was 8.1 months, and the median CNS progression-free survival (PFS) was 5.0 months. These results indicate that SRS can be a reasonable frontline choice, offering a potentially less neurotoxic alternative to WBRT in suitable patients [

151].

Systemic therapies seem to play a pivotal role in control of brain metastases in patients with SCLC. Most recently, the BiTE (bispecific T-cell engager) immunotherapy targeting delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3), tarlatamab, has been assessed in 186 patients (ECOG PS: 0–1; median prior lines of therapy: 2; median follow-up: 13.6 months) of whom 29% (54/186) had treated and stable brain metastases at baseline. Most patients (91%) with brain metastases had received prior local radiotherapy; 6% each had received surgery only or both radiotherapy and surgery. ORR was 45.3% in patients with brain metastases and 32.6% in patients without brain metastases. Tarlatamab showed a favorable benefit-risk profile in patients with previously treated SCLC and stable brain metastases [

106].

Furthermore, the DeLLphi-306 trial (NCT06117774) is currently underway to assess the efficacy of tarlatamab in a broader SCLC population. This phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examines tarlatamab in patients with LS-SCLC who have not progressed following initial concurrent chemoradiotherapy. The trial’s primary endpoint is PFS, with secondary endpoints including OS. This study aims to evaluate whether tarlatamab can effectively maintain disease control and prolong survival, offering a potential maintenance therapy option for patients who respond to initial treatment [

105,

106].

Smaller studies and case series suggest intracranial response rates from other systemic therapies for SCLC brain metastases, including irinotecan and temozolomide [

121], [

144].

4.4.2. Patients with Borderline Performance Status

Patients with borderline performance status (ECOG 3–4) in SCLC frequently experience significant psycho emotional distress, such as anxiety and depression, which complicates therapeutic management and diminishes quality of life [

154]. These individuals often require palliative care and continuous hospitalization, conditions that show strong correlations with heightened levels of anxiety and depression (PC = 0.78, p = 0.04; PC = 0.86, p = 0.03)[

154]. For these patients, less intensive treatment regimens, such as reduced chemotherapy or supportive care, may be considered to balance treatment efficacy with the goal of preserving quality of life [

155]. While immunotherapy is associated with improved emotional stability due to optimism about outcomes, those undergoing chemotherapy and palliative interventions report higher psycho emotional distress. Early psychological assessments and interventions are essential in managing these symptoms effectively and enhancing overall patient management [

156,

157]

.

4.4.3. Elderly

Although, there is no specific chronological age consistently used to define an individual to be elderly for purposes of lung cancer treatment, often Medicare coverage eligibility age of 65 years has been considered as elderly. In practice, organ function is believed more relevant than age [

158].

The treatment of SCLC in elderly patients is challenging due to age-related declines in organ function and the presence of comorbidities, which can exacerbate treatment-related toxicity. Although cCRT is the standard for younger and healthier patients with LS-SCLC, elderly patients often experience increased rates of severe hematologic and pulmonary toxicity. Nonetheless, carefully selected elderly patients, particularly those with good performance status and minimal comorbidities, can still benefit from standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimens, as recent studies have shown a survival advantage of cCRT over chemotherapy alone in this population [

159],. A subgroup analysis of the CONVERT trial explored outcomes in elderly patients [

46,

47,

48] . Results showed that older patients could still benefit from concurrent chemoradiotherapy, with similar rates of radiation-related toxicities compared to younger patients, although older individuals experienced more hematological side effects. However, most available data come from retrospective analyses with small sample sizes, highlighting the need for prospective, elderly-specific trials to provide clearer guidance on optimizing therapy for this growing patient group [

159,

160,

161]..

4.4.4. Patients with SCLC transformation and previous EGFR Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosis

Following an initial response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, EGFR mutated adenocarcinoma patients may become resistant to therapy. In about 5-10% of those will develop histologic transformation to SCLC [

162]. This SCLC transformation has a unique histological, molecular, and clinical profile over multiple time points, with heterogeneity noted and knowledge gap about the clinical outcomes over time for this EGFR TKI resistant subtype[

163].

Improving the relevant biomarkers will likely lead to the prediction of treatment responses, enabling the advancement of personalized and effective therapeutic strategies. In SCLC, recent studies have identified four biologically distinct subtypes, each with unique therapeutic vulnerabilities. These findings are significant for the development of targeted therapies, with the potential to enhance patient outcomes through more precise treatment selection[

167].

Combining

SLFN11 with other critical biomarkers may be a future direction, further refining patient stratification and therapeutic alignment. Emerging biomarkers, such as ASCL1, NEUROD1, POU2F3, and various inflammatory markers, have shown promise in guiding the use of novel therapeutic options, including PARP inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors. The identification and validation of these biomarkers could pave the way for a more individualized approach to SCLC management, optimizing therapeutic efficacy and minimizing adverse effects[

167].

4.4.5. Paraneoplastic Syndromes with Neurologic Manifestations

SCLC frequently manifests neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes, such as Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), subacute sensory neuropathy, and limbic encephalitis, which are driven by autoimmune processes involving onconeural antibodies that cause significant neuronal damage and disability [

164]. These syndromes occur in approximately 3-5% of SCLC cases and present significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Onconeural antibodies, such as anti-Hu, cross-react with neuronal antigens, leading to inflammation and tissue damage in the central and peripheral nervous systems. LEMS, the most commonly associated syndrome, presents with proximal muscle weakness, autonomic symptoms, and improved strength with repetitive activity.

The presence of these neurological syndromes can precede traditional cancer symptoms, making early recognition crucial for prompt SCLC diagnosis. Neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes require multidisciplinary management, including immunotherapy and symptomatic treatments, to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

However, the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in this patient population poses additional risks, as these treatments can potentially exacerbate autoimmune responses, worsening neurologic symptoms and leading to severe complications [

165]. Despite treatment efforts, outcomes vary depending on the specific antibodies involved, highlighting the need for timely intervention and tailored therapeutic approaches [

166].

4.4.6. Paraneoplastic Syndromes without Neurologic Manifestations

Endocrine paraneoplastic syndromes, including the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) and ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, are commonly seen in SCLC patients, where tumor cells produce ectopic hormones that result in severe metabolic disturbances. SIADH occurs in up to 45% of SCLC cases and is characterized by hyponatremia and water retention, requiring prompt recognition and management to prevent serious complications and facilitate optimal cancer treatment. Ectopic Cushing's syndrome (ECS), while less common, is associated with a poor prognosis due to complications like metabolic alkalosis, hypercoagulability, and resistance to standard therapies. Managing these non-neurologic syndromes involves targeting the underlying malignancy through chemotherapy or radiation, alongside symptomatic treatments such as vasopressin receptor antagonists for SIADH and cortisol-lowering agents for ECS. Early intervention and control of these endocrine disturbances are crucial for improving patient outcomes, emphasizing the importance of integrating paraneoplastic syndrome management with cancer therapy strategies [

164].

4.5. Supportive Care and Quality of Life

Integrating palliative care early in the treatment course has been shown to alleviate symptoms, enhance quality of life, and may even contribute to improved survival outcomes. Holistic approaches to palliative care address the comprehensive needs of the patient, including physical, emotional, and social dimensions, to optimize overall well-being.

Evidence supporting these benefits is demonstrated in clinical trials. For instance, a Phase III trial evaluated the effects of best supportive care (BSC) alone versus BSC combined with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed SCLC. The findings indicated that the addition of oral topotecan not only provided a survival advantage but also led to a marked improvement in quality-of-life metrics [

126]. Patients receiving topotecan exhibited slower deterioration in quality of life and better symptom management, particularly in critical areas such as shortness of breath, sleep disruption, and fatigue, when compared to those receiving only BSC. Furthermore, a Cochrane review reinforced these findings, highlighting that second-line chemotherapy, including topotecan, offers modest survival benefits over BSC alone, albeit with increased toxicity [

165].

These findings underscore the importance of integrating supportive therapies and palliative care interventions to enhance quality of life, even when modest survival benefits are accompanied by increased treatment-related toxicity.

In aggregate, a broad range of trials evaluating novel, personalized strategies for both LS and ES-SCLC are ongoing. Special attention to key patient populations including those with borderline performance status, the elderly and patients with paraneoplastic syndrome or other comorbidities is warranted as these patients are often underrepresented or excluded from clinical trials.

5. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

5.1. Biomarker Development

The development of reliable biomarkers is crucial for patient stratification and the prediction of treatment responses, enabling the advancement of personalized and effective therapeutic strategies. In SCLC, recent studies have identified four biologically distinct subtypes, each with unique therapeutic vulnerabilities. These findings are significant for the development of targeted therapies, with the potential to enhance patient outcomes through more precise treatment selection[

167].

5.2. Overcoming Drug Resistance

Overcoming drug resistance in SCLC remains a significant challenge due to the aggressive nature of the disease and its tendency to rapidly develop resistance to conventional therapies. Research into the mechanisms underlying this resistance is critical, as it may uncover new therapeutic targets and inform strategies aimed at prolonging treatment efficacy [

168].

Recent advances in the field have introduced promising strategies that focus on integrating molecular biomarkers and novel therapeutic agents to specifically target drug-resistant SCLC. For example, molecular biomarkers such as SLFN11 and DLL3 have shown potential in guiding treatment decisions and enhancing therapeutic responses. Additionally, innovative agents like PARP inhibitors and antibody-drug conjugates are being explored for their ability to circumvent resistance mechanisms [

81].

Collectively, these approaches offer hope for developing more personalized and effective treatment modalities tailored to the unique molecular profile of drug-resistant SCLC, thereby improving patient outcomes [

169].

Emerging therapeutic approaches for SCLC are revolutionizing treatment landscapes, with a significant focus on immunotherapy and targeted therapies. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, including atezolizumab and durvalumab, have demonstrated promising survival benefits, particularly when used in combination with standard chemotherapy regimens. This advancement represents a pivotal shift in the first-line treatment paradigm for extensive-stage SCLC, highlighting the integration of immunotherapy as a foundational component [

63,

67,

170].

Beyond immunotherapy, targeted therapies are gaining traction, aiming to address the complex biology and high mutational burden associated with SCLC. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) that target B7-H3, such as HS-20093; ifinatamab derutecan (I-DXd) [

159], or those targeting TROP-2, such as sacituzumab govitecan, are among the promising systemic therapies for the future. I-DXd is a humanized anti-B7-H3 IgG1 monoclonal antibody, a tetrapeptide-based cleavable linker that covalently bonds antibody and payload a topoisomerase I inhibitor payload (an exatecan derivative, DXd) [

171]

.

An interim analysis of the dose-optimization portion of the study, a confirmed objective response rate (ORR) of 54.8% (95% CI, 38.7%-70.2%) was observed in patients receiving the 12 mg/kg dose (n = 42), with 23 partial responses (PRs). An ORR of 26.1% (95% CI, 14.3%-41.1%) was reported in the 8 mg/kg cohort (n = 46), with 11 PRs and 1 complete response (CR). The median duration of response of 4.2 months (95% CI, 3.5-7.0) was reported in the 12 mg/kg group and 7.9 months (95% CI, 4.1-not estimable) in the 8 mg/kg group. Additionally, the disease control rate was 90.5% (95% CI, 77.4%-97.3%) and 80.4% (95% CI, 66.1%-90.6%) for the 12 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg groups, respectively[

171]

.

New agents such as WEE1 inhibitors are also under investigation to overcome intrinsic drug resistance mechanisms in SCLC. These targeted therapies aim to exploit vulnerabilities within the tumor’s molecular structure, paving the way for more personalized and combination-based treatment strategies. By leveraging these novel targeted approaches, there is hope for improved outcomes in SCLC management [

172]

.

5.3. Cost-Effectiveness and Biomarker-Driven Therapies

As personalized medicine continues to evolve in the treatment of SCLC, the integration of biomarkers such as SLFN11 and DLL3 holds promise for optimizing therapeutic outcomes by predicting patient responses to specific treatments. Despite these advancements, the cost-effectiveness of emerging therapies, particularly ICIs, remains a crucial factor, especially in resource-limited settings.

A recent cost-effectiveness analysis conducted in China evaluated several ICI regimens, including atezolizumab, durvalumab, and locally produced agents like serplulimab, when combined with chemotherapy for ES-SCLC. While these therapies demonstrated survival benefits, their high costs often surpassed the financial thresholds of the healthcare system. Among the options studied, the combination of serplulimab with chemotherapy proved to be the most cost-effective, delivering the highest quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at a relatively lower expense.

These findings highlight the significance of biomarker-driven strategies in SCLC. By identifying patients who are more likely to respond positively—such as those with SLFN11 expression—healthcare providers can enhance the cost-effectiveness of treatments. Targeted approaches not only maximize therapeutic efficacy but also reduce unnecessary expenditures, thereby improving both patient outcomes and economic sustainability [

173]

6. Conclusions

Recent advancements in systemic therapy for SCLC have started to reshape the treatment landscape for this aggressive and challenging disease. The integration of immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors like atezolizumab and durvalumab, into first-line treatment regimens has demonstrated significant survival benefits for patients with both LS and ES-SCLC. Refinements in radiation techniques, dose, and fractionation have also yielded promising improvements to outcomes, as has the integration of surgical management for highly select, node negative patients. These developments signal a promising shift toward more personalized therapeutic strategies, especially with the growing use of biomarkers such as SLFN11 and DLL3 to guide treatment decisions and improve outcomes. The exploration of novel agents like lurbinectedin and the ongoing investigation into multimodal approaches, including the use of consolidation and maintenance therapies, offer hope for extending survival, even in the recurrent setting [

85].

However, SCLC remains a formidable challenge, with treatment resistance and disease relapse still major hurdles. The genetic heterogeneity and rapid mutation rate of SCLC contribute to these obstacles, underscoring the need for further innovation in targeted therapies. While the use of molecular subtyping and biomarker-driven approaches provides a pathway for more personalized treatments, these strategies are still in the early stages of clinical application. Ongoing clinical trials are crucial in validating these approaches and ensuring that they translate into broad clinical practice.

Future research should focus on overcoming the persistent issue of drug resistance, potentially through combination therapies that target multiple pathways simultaneously. Additionally, there is a need for continued exploration of immune checkpoint inhibitors beyond the first-line setting, as well as the development of new targeted therapies, including antibody-drug conjugates and other biologics. Addressing the unique challenges faced by special populations, such as those with brain metastases, elderly patients, and individuals with paraneoplastic syndromes, will also be critical in optimizing treatment strategies for all SCLC patients.

The potentially proposed predictive biomarkers in SCLC are complex at this point compared to the status of currently available predictive biomarkers in NSCLC. The potentially proposed biomarkers for SCLC are still investigational as they are being incorporated as a part of new clinical trials. S1929 study has shown the feasibility of utilizing one of the emerging predictive biomarkers “SLFN11” to select patients for systemic therapy. However, improving a panel of predictive biomarkers along with the development of potent novel therapies will subsequently yield improvement in the clinical outcome for SCLC patients.

In conclusion, while significant strides have been made, there remains an urgent need for further research and clinical trials to refine these therapeutic approaches, overcome resistance mechanisms, and ultimately improve long-term survival rates for SCLC patients. Collaborative efforts across the research and clinical communities will be essential in translating these advancements into widespread clinical practice, thus providing better outcomes for patients with this aggressive form of lung cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.K. and M.D.; methodology, N.A.K. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.K. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, N.A.K. D.M, FM, O.M and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. There are no conflicts in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Govindan, R.; Page, N.; Morgensztern, D.; Read, W.; Tierney, R.; Vlahiotis, A.; Spitznagel, E.L.; Piccirillo, J. Changing Epidemiology of Small-Cell Lung Cancer in the United States Over the Last 30 Years: Analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiologic, and End Results Database. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 4539–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietanza, M.C.; Byers, L.A.; Minna, J.D.; Rudin, C.M. Small Cell Lung Cancer: Will Recent Progress Lead to Improved Outcomes? Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2244–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]