Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Materials and Methods

2.1. Cloning

2.2. Recombinant Protein Production and Purification

2.3. Determination of Recombinant Protein Concentration

2.4. In Vitro Fusion Reactions and Complex Purification

2.5. Nitrocefin Cleavage Assay

2.6. Sodium Dodecyl-Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.7. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Based Assay

3. Results

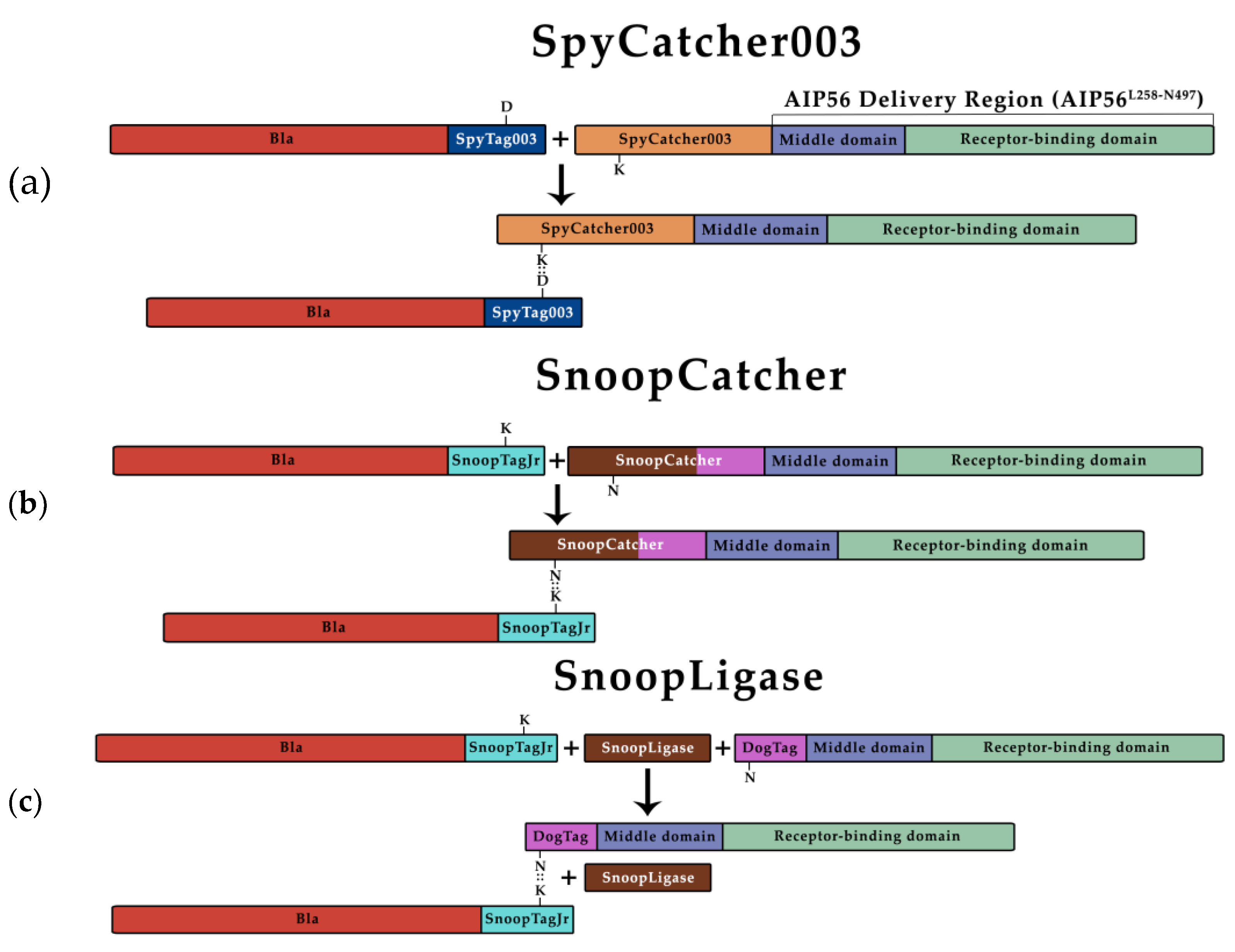

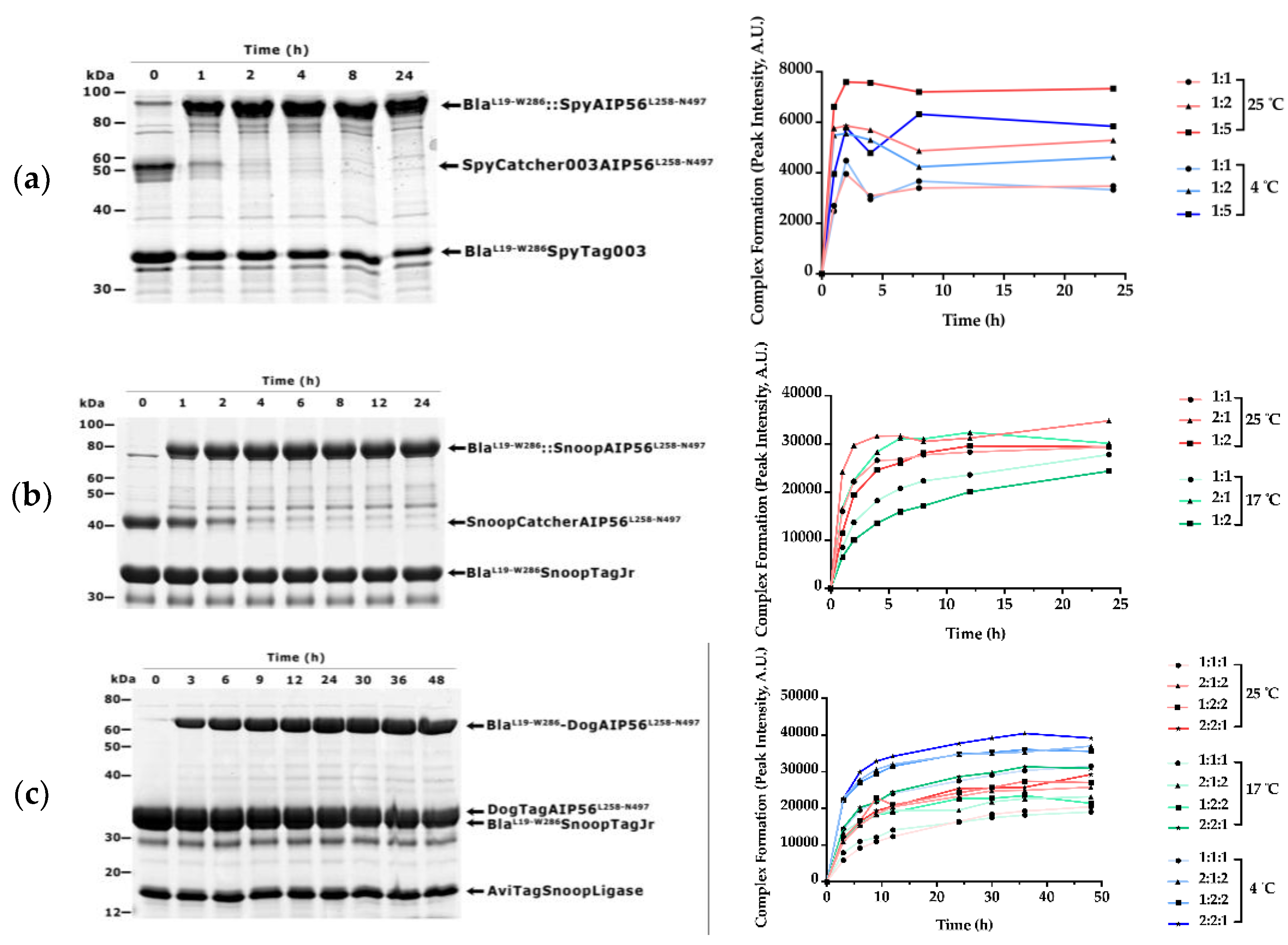

3.1. β-Lactamase Can Be Efficiently Coupled to AIP56 Delivery Region Using Biochemical Approaches

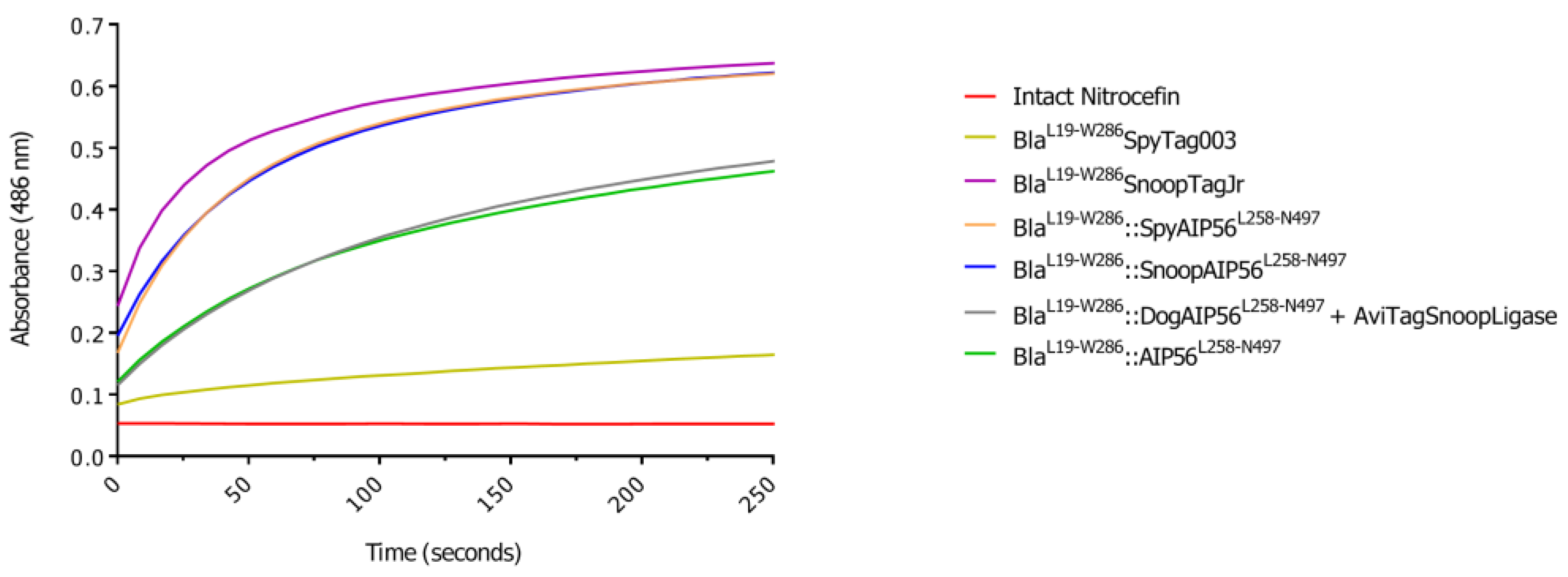

3.2. BlaL19-W286::SpyAIP56L258-N497, BlaL19-W286::SnoopAIP56L258-N497 and BlaL19-W286::DogAIP56L258-N497 + AviTagSnoopLigase Retain β-Lactamase Activity

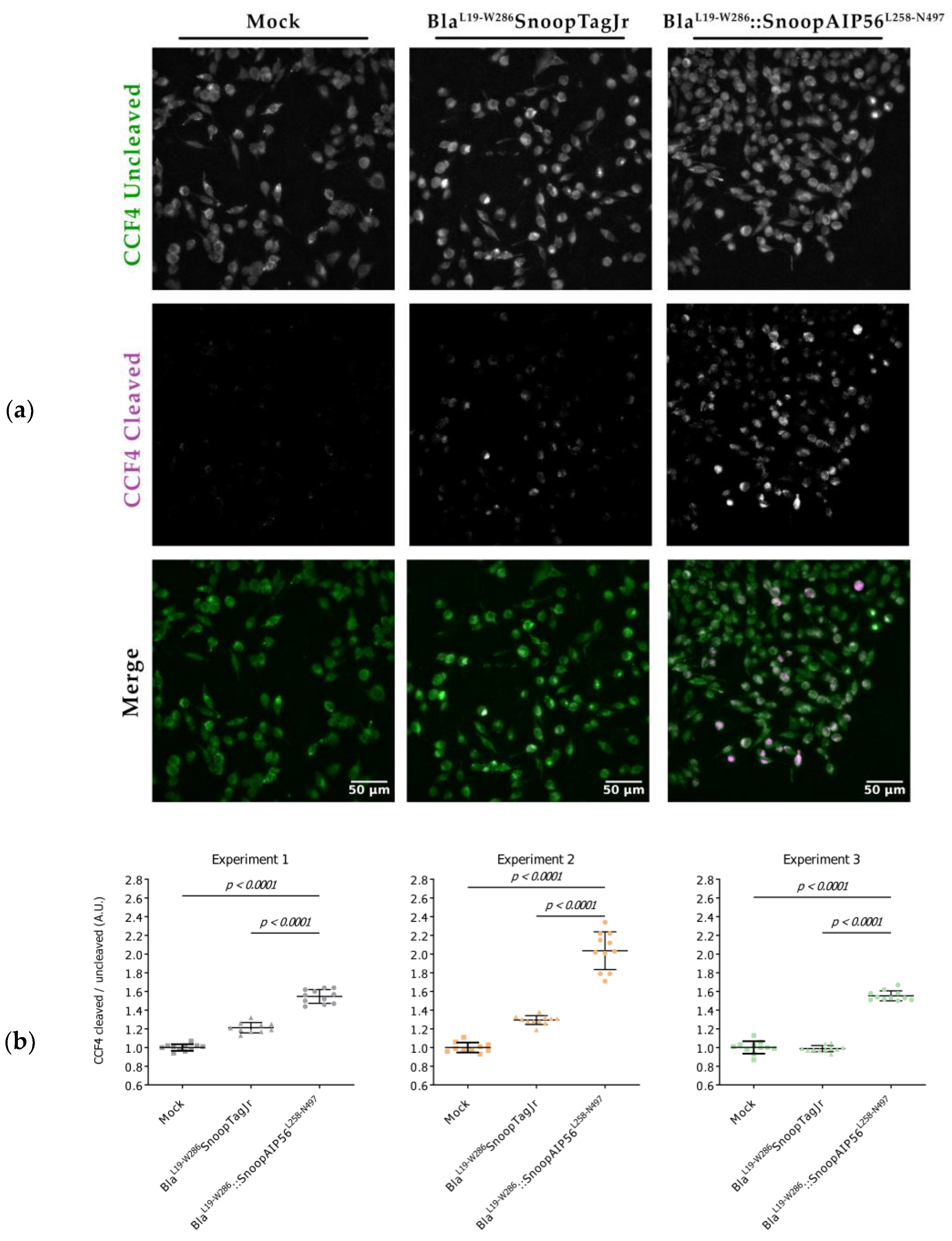

3.3. BlaL19-W286::SnoopAIP56L258-N497 Transports β-Lactamase into the Cytosol of Macrophages

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biopharmaceuticals Market Size Report, 2022-2027 Available online: https://www.industryarc.com/Report/9586/biopharmaceutical-market.html (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 122–128. [CrossRef]

- Basak, D.; Arrighi, S.; Darwiche, Y.; Deb, S. Comparison of Anticancer Drug Toxicities: Paradigm Shift in Adverse Effect Profile. Life 2021, 12, 48. [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, K.; Rengstl, B.; Oehm, P.; Michel, K.; Billmeier, A.; Hayduk, N.; Klein, O.; Kuna, K.; Ouchan, Y.; Wöll, S.; et al. An RNA vaccine drives expansion and efficacy of claudin-CAR-T cells against solid tumors. Science 2020, 367, 446–453. [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Gao, G.F. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 21, 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Cervantes, J.; Ramírez-Jarquín, J.O.; Vaca, L. Interaction Between Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) and Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) From Dendritic Cells (DCs): Toward Better Engineering of VLPs. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1100. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Filipczak, N.; Torchilin, V.P. Cell penetrating peptides: A versatile vector for co-delivery of drug and genes in cancer. J. Control. Release 2020, 330, 1220–1228. [CrossRef]

- Gessner, I.; Klimpel, A.; Klußmann, M.; Neundorf, I.; Mathur, S. Interdependence of charge and secondary structure on cellular uptake of cell penetrating peptide functionalized silica nanoparticles. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 2, 453–462. [CrossRef]

- Yetisgin, A.A.; Cetinel, S.; Zuvin, M.; Kosar, A.; Kutlu, O. Therapeutic Nanoparticles and Their Targeted Delivery Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 2193. [CrossRef]

- Beilhartz, G.L.; Sugiman-Marangos, S.N.; Melnyk, R.A. Repurposing bacterial toxins for intracellular delivery of therapeutic proteins. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 142, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Piot, N.; van der Goot, F.G.; Sergeeva, O.A. Harnessing the Membrane Translocation Properties of AB Toxins for Therapeutic Applications. Toxins 2021, 13, 36. [CrossRef]

- Falnes, P.Ø.; Sandvig, K. Penetration of protein toxins into cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000, 12, 407–413. [CrossRef]

- Geny, B.; Popoff, M.R. Bacterial protein toxins and lipids: role in toxin targeting and activity. Biol. Cell 2006, 98, 633–651. [CrossRef]

- Geny, B.; Popoff, M.R. Bacterial protein toxins and lipids: pore formation or toxin entry into cells. Biol. Cell 2006, 98, 667–678. [CrossRef]

- Márquez-López, A.; Fanarraga, M.L. AB Toxins as High-Affinity Ligands for Cell Targeting in Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11227. [CrossRef]

- Odumosu, O.; Nicholas, D.; Yano, H.; Langridge, W. AB Toxins: A Paradigm Switch from Deadly to Desirable. Toxins 2010, 2, 1612–1645. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Fredriksson, M.; Nordström, I.; Holmgren, J. Cholera Toxin and Its B Subunit Promote Dendritic Cell Vaccination with Different Influences on Th1 and Th2 Development. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 1740–1747. [CrossRef]

- Batisse, C.; Dransart, E.; Ait Sarkouh, R.; Brulle, L.; Bai, S.-K.; Godefroy, S.; Johannes, L.; Schmidt, F. A New Delivery System for Auristatin in STxB-Drug Conjugate Therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 95, 483–491.

- Ladant, D. Bioengineering of Bordetella pertussis Adenylate Cyclase Toxin for Vaccine Development and Other Biotechnological Purposes. Toxins 2021, 13, 83. [CrossRef]

- Chenal, A.; Ladant, D. Bioengineering of Bordetella pertussis Adenylate Cyclase Toxin for Antigen-Delivery and Immunotherapy. Toxins 2018, 10, 302. [CrossRef]

- Falahatgar, D.; Farajnia, S.; Zarghami, N.; Tanomand, A.; Khosroshahi, S.A.; Akbari, B.; Farajnia, H. Expression and Evaluation of HuscFv Antibody -PE40 Immunotoxin for Target Therapy of EGFR-Overexpressing Cancers. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 241–247. [CrossRef]

- Weldon, J.E.; Xiang, L.; Chertov, O.; Margulies, I.; Kreitman, R.J.; FitzGerald, D.J.; Pastan, I. A protease-resistant immunotoxin against CD22 with greatly increased activity against CLL and diminished animal toxicity. Blood 2009, 113, 3792–3800. [CrossRef]

- Do Vale, A.; Silva, M.T.; Santos, N.M.S. dos; Nascimento, D.S.; Reis-Rodrigues, P.; Costa-Ramos, C.; Ellis, A.E.; Azevedo, J.E. AIP56, a Novel Plasmid-Encoded Virulence Factor of Photobacterium Damselae Subsp. Piscicida with Apoptogenic Activity against Sea Bass Macrophages and Neutrophils. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 58, 1025–1038.

- Silva, D.S.; Pereira, L.M.G.; Moreira, A.R.; Ferreira-Da-Silva, F.; Brito, R.M.; Faria, T.Q.; Zornetta, I.; Montecucco, C.; Oliveira, P.; Azevedo, J.E.; et al. The Apoptogenic Toxin AIP56 Is a Metalloprotease A-B Toxin that Cleaves NF-κb P65. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003128. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.M.G.; Pinto, R.D.; Silva, D.S.; Moreira, A.R.; Beitzinger, C.; Oliveira, P.; Sampaio, P.; Benz, R.; Azevedo, J.E.; dos Santos, N.M.S.; et al. Intracellular Trafficking of AIP56, an NF-κB-Cleaving Toxin from Photobacterium Damselae Subsp. Piscicida. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 5270–5285.

- Do Vale, A.; Pereira, C.; R. Osorio, C.; MS dos Santos, N. The Apoptogenic Toxin AIP56 Is Secreted by the Type II Secretion System of Photobacterium Damselae Subsp. Piscicida. Toxins 2017, 9, 368.

- Lisboa, J.; Pereira, C.; Pinto, R.D.; Rodrigues, I.S.; Pereira, L.M.G.; Pinheiro, B.; Oliveira, P.; Pereira, P.J.B.; Azevedo, J.E.; Durand, D.; et al. Unconventional Structure and Mechanisms for Membrane Interaction and Translocation of the NF-κB-Targeting Toxin AIP56. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7431.

- Pereira, C.; Rodrigues, I.S.; Pereira, L.M.; Lisboa, J.; Pinto, R.D.; Araújo, L.; Oliveira, P.; Benz, R.; dos Santos, N.M.S.; Vale, A.D. Role of AIP56 disulphide bond and its reduction by cytosolic redox systems for efficient intoxication. Cell. Microbiol. 2019, 22, e13109. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, I.L.; Macedo, F.; Oliveira, L.; Oliveria, P.; do Vale, A.; dos Santos, N.M.S. AIP56, an AB Toxin Secreted by Photobacterium Damselae Subsp. Piscicida, Has Tropism for Myeloid Cells. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15.

- Rodrigues, I.S.; Pereira, L.M.G.; Lisboa, J.; Pereira, C.; Oliveira, P.; Santos, N.M.S. dos; Vale, A. do Involvement of Hsp90 and Cyclophilins in Intoxication by AIP56, a Metalloprotease Toxin from Photobacterium Damselae Subsp. Piscicida. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9019.

- Rabideau, A.E.; Pentelute, B.L. Delivery of Non-Native Cargo into Mammalian Cells Using Anthrax Lethal Toxin. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1490–1501. [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, S.-I.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Shoemaker, C.B.; Dong, M. Delivery of single-domain antibodies into neurons using a chimeric toxin–based platform is therapeutic in mouse models of botulism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Bin Lee, H.; Kang, S. Development of plug-and-deliverable intracellular protein delivery platforms based on botulinum neurotoxin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129622. [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, B.; Fierer, J.O.; Celik, E.; Chittock, E.C.; Schwarz-Linek, U.; Moy, V.T.; Howarth, M. Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E690–7. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fierer, J.O.; Rapoport, T.A.; Howarth, M. Structural Analysis and Optimization of the Covalent Association between SpyCatcher and a Peptide Tag. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 426, 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Veggiani, G.; Nakamura, T.; Brenner, M.D.; Gayet, R.V.; Yan, J.; Robinson, C.; Howarth, M. Programmable polyproteams built using twin peptide superglues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1202–1207. [CrossRef]

- Izoré, T.; Contreras-Martel, C.; El Mortaji, L.; Manzano, C.; Terrasse, R.; Vernet, T.; Di Guilmi, A.M.; Dessen, A. Structural Basis of Host Cell Recognition by the Pilus Adhesin from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Structure 2010, 18, 106–115. [CrossRef]

- Buldun, C.M.; Jean, J.X.; Bedford, M.R.; Howarth, M. SnoopLigase Catalyzes Peptide–Peptide Locking and Enables Solid-Phase Conjugate Isolation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3008–3018. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fierer, J.O.; Rapoport, T.A.; Howarth, M. Structural Analysis and Optimization of the Covalent Association between SpyCatcher and a Peptide Tag. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 426, 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Keeble, A.H.; Banerjee, A.; Ferla, M.P.; Reddington, S.C.; Anuar, I.N.A.K.; Howarth, M. Evolving Accelerated Amidation by SpyTag/SpyCatcher to Analyze Membrane Dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 16521–16525. [CrossRef]

- Keeble, A.H.; Turkki, P.; Stokes, S.; Anuar, I.N.A.K.; Rahikainen, R.; Hytönen, V.P.; Howarth, M. Approaching infinite affinity through engineering of peptide–protein interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 26523–26533. [CrossRef]

- Keeble, A.H.; Wood, D.P.; Howarth, M. Design and Evolution of Enhanced Peptide–Peptide Ligation for Modular Transglutaminase Assembly. Bioconjugate Chem. 2023, 34, 1019–1036. [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- Kaderabkova, N.; Bharathwaj, M.; Furniss, R.C.D.; Gonzalez, D.; Palmer, T.; Mavridou, D.A. The biogenesis of β-lactamase enzymes. Microbiology 2022, 168, 001217. [CrossRef]

- Zlokarnik, G. Fusions to Beta-Lactamase as a Reporter for Gene Expression in Live Mammalian Cells. Methods Enzymol. 2000, 326, 221–244.

- Moore, J.T.; Davis, S.T.; Dev, I.K. The Development of β-Lactamase as a Highly Versatile Genetic Reporter for Eukaryotic Cells. Anal. Biochem. 1997, 247, 203–209. [CrossRef]

- Zlokarnik, G.; Negulescu, P.A.; Knapp, T.E.; Mere, L.; Burres, N.; Feng, L.; Whitney, M.; Roemer, K.; Tsien, R.Y. Quantitation of Transcription and Clonal Selection of Single Living Cells with β-Lactamase as Reporter. Science 1998, 279, 84–88. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.E. Realization of β-lactamase as a versatile fluorogenic reporter. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 208–211. [CrossRef]

- O'Callaghan, C.H.; Morris, A.; Kirby, S.M.; Shingler, A.H. Novel Method for Detection of β-Lactamases by Using a Chromogenic Cephalosporin Substrate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1972, 1, 283–288. [CrossRef]

- Zuverink, M.; Barbieri, J.T. From GFP to β-lactamase: advancing intact cell imaging for toxins and effectors. Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, B.; Farajnia, S.; Ahdi Khosroshahi, S.; Safari, F.; Yousefi, M.; Dariushnejad, H.; Rahbarnia, L. Immunotoxins in cancer therapy: Review and update. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 36, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Beddoe, T.; Paton, A.W.; Le Nours, J.; Rossjohn, J.; Paton, J.C. Structure, biological functions and applications of the AB5 toxins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 411–418. [CrossRef]

- Kenworthy, A.K.; Schmieder, S.S.; Raghunathan, K.; Tiwari, A.; Wang, T.; Kelly, C.V.; Lencer, W.I. Cholera Toxin as a Probe for Membrane Biology. Toxins 2021, 13, 543. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Choi, B.; Bae, Y.; Lee, Y.G.; Park, S.A.; Chae, Y.C.; Kang, S. Selective and Effective Cancer Treatments using Target-Switchable Intracellular Bacterial Toxin Delivery Systems. Adv. Ther. 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Wernick, N.L.B.; Chinnapen, D.J.-F.; Cho, J.A.; Lencer, W.I. Cholera Toxin: An Intracellular Journey into the Cytosol by Way of the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Toxins 2010, 2, 310–325. [CrossRef]

- Young, J.A.; Collier, R.J. Anthrax Toxin: Receptor Binding, Internalization, Pore Formation, and Translocation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 243–265. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, V.M.; Leppla, S.H. Proteolytic activation of bacterial toxins: role of bacterial and host cell proteases. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 333–40. [CrossRef]

- Uribe, K.B.; Etxebarria, A.; Martín, C.; Ostolaza, H. Calpain-Mediated Processing of Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Generates a Cytosolic Soluble Catalytically Active N-Terminal Domain. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e67648. [CrossRef]

- Carr, W.W.; Jain, N.; Sublett, J.W. Immunogenicity of Botulinum Toxin Formulations: Potential Therapeutic Implications. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 5046–5064. [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Fang, T.; Liu, S.; Song, X.; Yu, C.; Li, J.; Fu, L.; Hou, L.; Xu, J.; Chen, W. Comparative Immunogenicity of the Tetanus Toxoid and Recombinant Tetanus Vaccines in Mice, Rats, and Cynomolgus Monkeys. Toxins 2016, 8, 194. [CrossRef]

- Elson, C.O. Cholera Toxin and Its Subunits as Potential Oral Adjuvants. In Proceedings of the New Strategies for Oral Immunization; Mestecky, J., McGhee, J.R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1989; pp. 29–33.

- Mazor, R.; Pastan, I. Immunogenicity of Immunotoxins Containing Pseudomonas Exotoxin A: Causes, Consequences, and Mitigation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1261. [CrossRef]

| Plasmid | Purpose | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| p327 | Template to amplify the coding sequence of BlaL19-W286 | A gift from Dr. Panagiotis Papatheodorou, Ulm University |

| pET28a_BlaL19-W286SnoopTagJr | Expression of BlaL19-W286 in frame with SnoopTagJr and 6x HisTag in the C-terminal | This work |

| pET28a_BlaL19-W286SpyTag003 | Expression of BlaL19-W286 in frame with SpyTag003 and 6x HisTag in the C-terminal | This work |

| pET28a_BlaL19-W286AIP56L258-N497 | Expression of BlaL19-W286 fused to AIP56L258-N497 in frame with a 6x HisTag in the C-terminal | Rodrigues et al, 2019 [30] |

| pET28a–SnoopCatcher | Template to amplify the coding sequence of SnoopCatcher | Addgene plasmid #72322; Veggiani et al, 2016 [36] |

| pDEST14-SpyCatcher003 | Template to amplify the coding sequence of SpyCatcher003 | Addgene plasmid # 133447; Keeble et al, 2019 [41] |

| pET28AIP56H+ | Template to amplify the coding sequence of AIP56L258-N497 | do Vale et al, 2005 [23] |

| pET28a_AIP56L258-N497 | Backbone to insert SnoopCatcher/SpyCatcher003 coding sequence in frame with AIP56L258-N497 | This work |

| pET28a_SnoopCatcherAIP56L258-N497 | Expression of SnoopCatcher fused to AIP56L258-N497 in frame with a 6x HisTag in the C-terminal | This work |

| pET28a_ SpyCatcher003AIP56L258-N497 | Expression of SpyCatcher003 fused to AIP56L258-N497 in frame with a 6x HisTag in the C-terminal | This work |

| pET28a_DogTagAIP56L258-N497 | Expression of DogTag fused to AIP56L258-N497 in frame with a 6x HisTag in the C-terminal | This work |

| pET28a–His6-AviTagSnoopLigase | Expression of AviTag fused to SnoopLigase in frame with a 6x HisTag in the N-terminal | Addgene plasmid #105626; Buldun et al [38] |

| Protein | Slope (ΔAbs.min-1) |

|---|---|

| BlaL19-W286SpyTag003 | 0.77 × 10-3 |

| BlaL19-W286SnoopTagJr | 7.66 × 10-3 |

| BlaL19-W286::SpyAIP56L258-N497 | 7.38 × 10-3 |

| BlaL19-W286::SnoopAIP56L258-N497 | 6.43 × 10-3 |

| BlaL19-W286::DogAIP56L258-N497+AviTagSnoopLigase | 3.58 × 10-3 |

| BlaL19-W286::AIP56L258-N497 | 3.54 × 10-3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).