Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

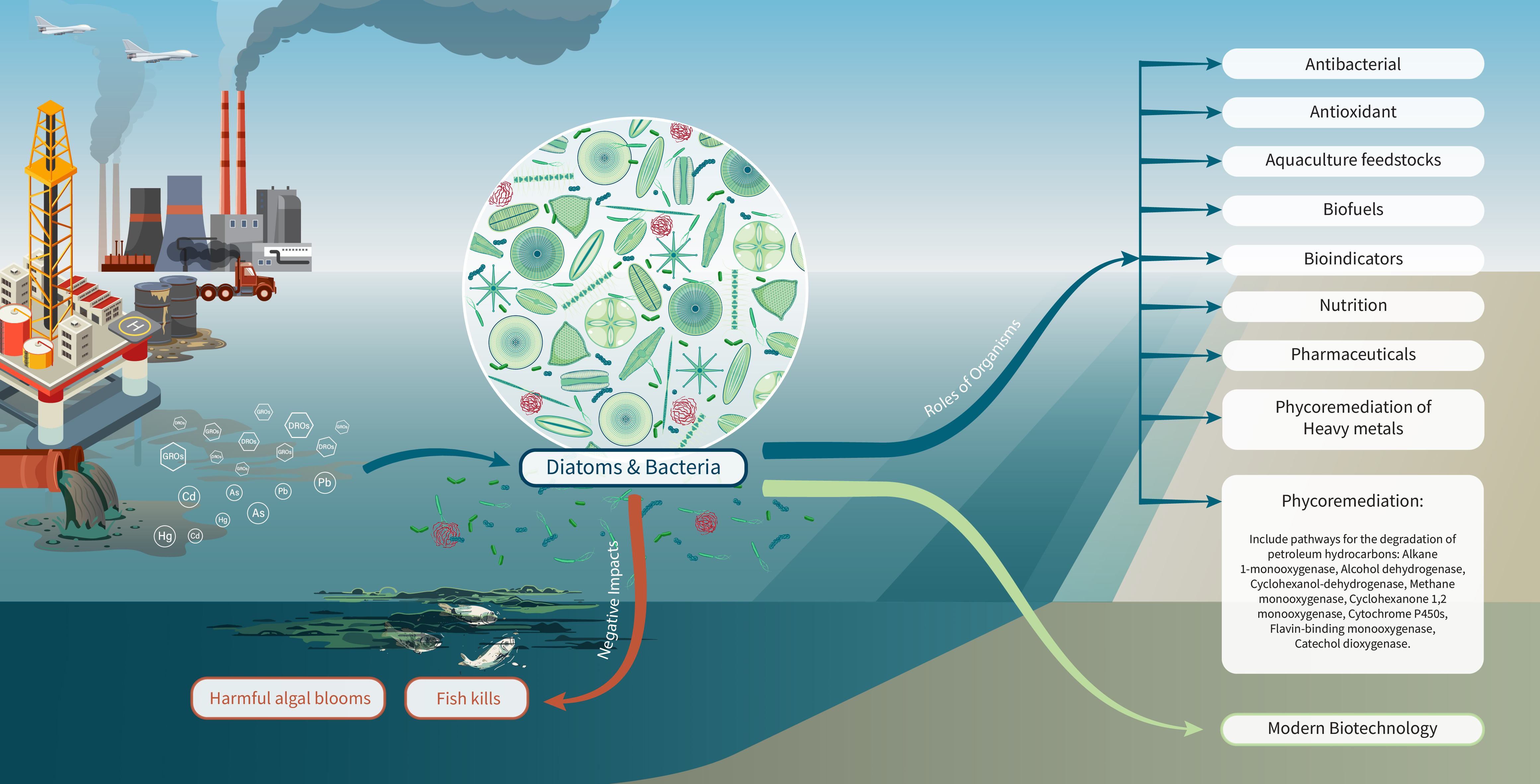

Diatoms in the Arabian Gulf region contribute to various biological carbon pumps, playing crucial ecological roles and producing bioactive compounds beneficial to both humans and marine animals. Despite their significance, some diatoms pose risks to human health and the economy; however, research on their roles in Qatar remains limited. This review explores the roles of diatoms in the Arabian Gulf, highlighting their potential for remediating polluted seawater and their applications in pharmacology, biofuel production, and detoxification of chemical waste and hazardous metals. Among the 242 diatom species identified along the coastline of the Gulf and Qatar, several genera represent 50% of the identified species and have demonstrated notable efficiency in phycoremediation and bioactive compounds production. These include antibacterial agents with therapeutic potential, antioxidants to neutralize harmful free radicals, compounds that degrade toxic substances, and agents for remediating heavy metals. Additionally, diatoms contribute to the production of biofuels, nutritional agents, dyes, and extracellular polymeric substances, and some species serve as bioindicators of pollution stress. To fully utilize their potential requires significant efforts and comprehensive research. This review explores the reasons behind the current lack of such initiatives and highlights the importance of conducting targeted studies to address the environmental challenges facing the Arabian Gulf.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Roles Played by Diatoms in the Marine Ecosystem

2. General Findings on Diatom Research in the Arabian Gulf Region

2.1. Phycoremediation and Its Bioactive Applications

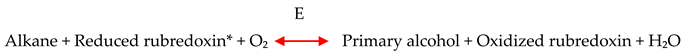

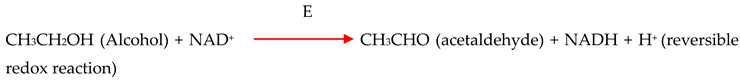

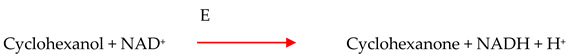

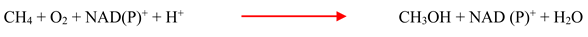

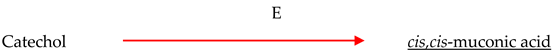

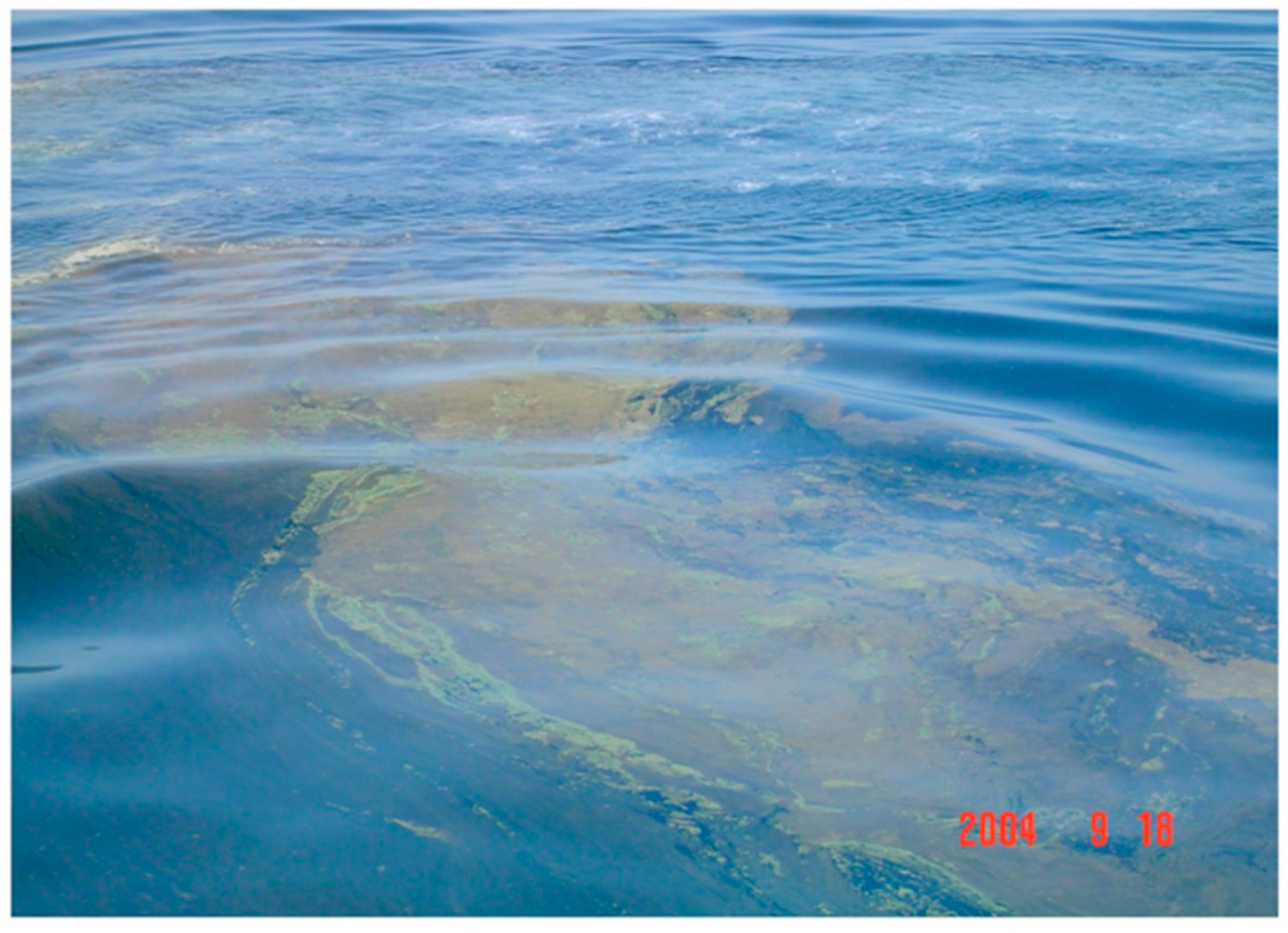

2.2. Pathways for Phycoremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons Using Diatom

| Production and applications | Genera | Remarks* |

| Antibacterial | Actinoptychus, Chaetoceros, Rhizosolenia | Chaetoceros comprises about 34 species that require modern research to develop antibacterial products |

| Antioxidants | Amphora, Cerataulina, Raphoneis | Some chemicals are produced under extreme stress conditions, such as those caused by pollution from oil and gas activities. These chemicals are unstable and can damage cell membranes and other structures. Diatoms under such conditions may produce antioxidants as a protective response |

| Aquaculture feedstocks | Cocconeis, Coscinosira, Podocystis | Aquaculture feedstocks are raw materials used to feed aquatic organisms in aquaculture, including fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants |

| Biofuels | Amphiprora, Climacodium, Cocconeis, Coscinosira, Guinardia, Gyrosigma, Navicula, Podocystis | Biofuels are fuels made from renewable biological sources. Many types of biofuels are known, including ethanol, biodiesel, biogas, biojet kerosene, and sustainable aviation fuel |

| Bioindicators | Cocconeis, Corethron, Coscinosira, Dactyliosolen, Fragilaria, Paralia, Planktoniella, Schroederella, Skeletonema, Trachyneis | A bioindicator is a living organism that reflects the health of an environment. Bioindicators can exhibit changes in various aspects, such as physiology, chemistry, or behavior. Phytoplankton responds quickly to environmental changes, making it an effective indicator of water pollution |

| Dyes | Nitzschia, Pinnularia | Dyes refer to a variety of pigments and related components, such as carotenoids, chlorophylls, polyphenols, and marennine, a blue-green pigment produced by certain diatoms |

| EPS production | Plagiogramma, Stauroneis, Thalassiothrix, Tropidoneis | EPS, or extracellular polymeric substances, are produced by microorganisms and have potential applications in wastewater sludge treatment |

| Phycoremediation: phyto-mining (heavy metals), and green liver model (degradation of organic compounds) | Asterolampra, Asteromphalus, Auliscus, Bacillaria, Bacteriastrum, Campylodiscus, Cerataulina, Climacodium, Climacosphenia, Cocconeis, Corethron, Coscinosira, Cyclotella (HM: Ti), Cylindrotheca, Cymbella, Dactyliosolen, Diatoma, Diploneis, Ditylum, Gossleriella, Grammatophora, Guinardia, Gyrosigm, Hemiaulus, Hemidiscus, Hydrosilicon, Lauderia, Mastogloia, Navicula, Nitzschia, Paralia, Pinnularia, Planktoniella, Podocystis, Raphoneis, Schroederella, Streptotheca, Striatella, Synedra, Thalassionema, Thalassiothrix, Trachyneis, Triceratium, Tropidoneis | Most diatoms can remediate heavy metals, a topic that requires in-depth research to understand their roles in polluted seawater. The remediation of heavy metals includes detoxification and testing, while organic compounds from oil and gas activities primarily involve petroleum hydrocarbons |

| Production and applications | Genera | Remarks* |

| Nutritional | Bellerochea, Biddulphia, Climacodium | Diatoms are among the most sustainable sources of nutrients for humans. They are a major source of oxygen, serve as a key food source for higher organisms, and remove significant amounts of CO₂ while synthesizing various metabolites. Diatoms produce a wide range of primary metabolites, including proteins, peptides, fatty acids, sterols, and polysaccharides. Their secondary metabolites include carotenoids, polyphenols, high-value molecules, and silica nanoparticles |

| Pharmaceuticals | Bellerochea, Climacodium, Cocconeis, Coscinosira, Podocystis | Chrysolaminarin, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, omega fatty acids, fucoxanthin, and biosilica are all substances with potential anticancer properties |

| Various applications | Amphora (against toxicities of other organisms), Chaetoceros (various applications), Climacodium (biofertilizers), Cyclotella (accumulates titanium), Gossleriella (smart nanocontainer for various agents), Hemiaulus (nitrogen fixation, food production, climate change), Skeletonema (production of vitamins, pigments, polyunsaturated fatty acids), Tropidoneis (resistant against pollution) | Several roles and applications have been reported |

3. Challenges and Future Work

4. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bach, L. T., Taucher, J. CO2 effects on diatoms: A synthesis of more than a decade of ocean acidification experiments with natural communities. Ocean Sci. 2019, 15, 1159–1175. [CrossRef]

- Marella, T. K., Pacheco, I. Y. L., Parra, R., Dixit, S., Tiwari, A. Wealth from waste: Diatoms as tools for phycoremediation of wastewater and for obtaining value from the biomass. The Science of The Total Environment 2020, 724 (80), 137960. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R. F., Yasseen, B. T. Methods using marine aquatic photoautotrophs along the Qatari coastline to remediate oil and gas industrial water. Toxics 2024, 12 (9), 625. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R. F., Yasseen, B.T. Cyano-remediation of Polluted Seawater in the Arabian Gulf: Risks and Benefits to Human Health. Processes 2024, 12 (12), 2733. https:// doi.org/10.3390/pr12122733.

- Dorgham, M. M., Al-Muftah, A. M. Plankton studies in the Arabian Gulf. I. Preliminary list of phytoplankton species in Qatari waters. Arab Gulf J. Scient. Res. Agric. Biol. Sci. 1986, 4 (2), 421-436.

- Polikarpov, I., Saburova, M., Al-Yamani, F. Diversity and distribution of winter phytoplankton in the Arabian Gulf and the Sea of Oman. Continental Shelf Research 2016, 119, 85-99. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, R. B. An Introduction to the Microscopical Study of Diatoms, edited by Delly, J. G., Gill, S. http://www.microscopy-uk.org.uk/diatomist/rbm_US_Royal.pdf, 2012. (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Al-Yamani, F. A., Saburova, M. A. Marine Phytoplankton of Kuwait’s Waters, Diatoms, Vol. 2. Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, Kuwait. Waves Press. ISBN 978-99966-37-20-0, 2019. (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Johnston, J. E., Lim, E., Roh, H. Impact of upstream oil extraction and environmental public health: A review of the evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Calderon, J. L., Sorensen, C., Lemery, J., Workman, C. F., Linstadt, H., Bazilian, M. D. Managing upstream oil and gas emissions: A public health-oriented approach. Journal of Environmental Management. 2022. 310, 114766. [CrossRef]

- B-Béres, V., Stenger-Kovács, C., Buczkó, K., Padisák, J., Selmeczy, G. B., Lengyel, E., Tapolczai, K. Ecosystem services provided by freshwater and marine diatoms. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 2707–2733. [CrossRef]

- Kusk, K. O. Effects of crude oil and aromatic hydrocarbons on the photosynthesis of the diatom Nitzschia palea. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 43(1), 1-6. doi.10.1111/j.1399-3054.1978. tb 01558.x.

- Kamalanathan, M., Mapes, S., Hillhouse, J., Claflin, N., Leleux, J., Hala, D., Quigg, A. Molecular mechanism of oil induced growth inhibition in diatoms using Thalassiosira pseudonana as the model species. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19831. [CrossRef]

- Benoiston, A-S., Ibarbalz, F. M., Bittner, L., Guidi, L., Jahn, O., Dutkiewicz, S., Bowler, C. The evolution of diatoms and their biogeochemical functions. Philosophical Transactions B 2017, 372(1728), 20160397. [CrossRef]

- Sethi, D., Butler, T. O., Shuhaili, F., Vaidyanathan, S. Diatoms for carbon sequestration and bio-based manufacturing. Biology (Basel) 2020, 9 (8), 217. [CrossRef]

- Neeti, K.; Singh, R.; Sakshi.; Kumar, A.; Ahmad, S.; Diatoms for value-added products: challenges and opportunities. In Multidisciplinary Applications of Marine Resources; Rafatullah, M., Siddiqui, M. R., Khan, M. A., Kapoor, R. T.; Springer, Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd, 2024. Gateway East, Singapore, 2024; 189721. [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., Wichuk, K., Brynjólfsson S. Developing diatoms for value-added products: challenges and opportunities. N. Biotechnol. 2015, 32(6), 547-51. [CrossRef]

- Elling, F. J., Hemingway, J. D., Kharbush, J. J., Becker, K. W., Polik, C. A., Pearson, A. Linking diatom-diazotroph symbioses to nitrogen cycle perturbations and deep-water anoxia: Insights from Mediterranean sapropel events. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2021,571, 117110. [CrossRef]

- Smayda, T. J., Trainer, V. L. Dinoflagellate blooms in upwelling systems: Seeding, variability, and contrasts with diatom bloom behavior. Progress in Oceanography 2010, 85 (1-2), 92-107. [CrossRef]

- https://themeaningofwater.com/2023/05/14/when-diatoms-bloom-in-spring/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Chowdhury, M., Biswas, H., Mitra, A., Silori, S., Sharma, D., Bandyopadhyay, D., Shaik, A. U. R., Fernandes, V., Narvekar, J. Southwest monsoon-driven changes in the phytoplankton community structure in the central Arabian Sea (2017–2018): After two decades of JGOFS. Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 197, 102654. [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S., Madhupratap, M. Seasonality and composition of phytoplankton. Curr. Sci. 1996, 71(11), 869–873.

- Pandey, M., Biswas, H., Birgel, D., Burdanowitz, N., Gaye, B. Sedimentary organic matter signature hints at the phytoplankton-driven biological carbon pump in the central Arabian Sea. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 4681–4698. [CrossRef]

- Rixen, T., Gaye, B., Emeis, K-C. The monsoon, carbon fluxes, and the organic carbon pump in the northern Indian Ocean. Progress in Oceanography 2019, 175, 24-39. [CrossRef]

- Weirich, C. A., Miller, T. R. Freshwater harmful algal blooms: toxins and children's health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2014, 44 (1), 2-24. [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E., Fleming, L. E., Gowen, R., Davidson, K., Hess, P., Backer, L. C., Moore, S. K., Hoagland, P., Enevoldsen, H. Marine harmful algal blooms, human health, and wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK. 2015, 2015. (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Whalen, J. K., Cai, C., Shan, K., Zhou, H. Harmful cyanobacteria-diatom/dinoflagellate blooms and their cyanotoxins in freshwaters: A nonnegligible chronic health and ecological hazard. Water Research 2023, 233, 119807. [CrossRef]

- Amin, S. A., Parker, M. S., Armbrust, E. V. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76 (3), 667-84. [CrossRef]

- Di Costanzo, F., Di Dato, V., Romano, G. Diatom-bacteria interactions in the marine environment: Complexity, heterogeneity, and potential for biotechnological Applications. Microorganisms 2023, 11(12), 2967. [CrossRef]

- Sterling, A. R., Holland, L. Z., Bundy, R. M., Burns, S. M., Buck, K. N., Chappell, P. D., Jenkins, B. D. Potential interactions between diatoms and bacteria are shaped by trace element gradients in the Southern Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Ashraf, S. S. Harnessing microalgae: Innovations for achieving UN Sustainable Development Goals and climate Resilience. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 68, 106506. [CrossRef]

- Sprynskyy, M., Monedeiro, F., Monedeiro-Milanowski, M., Nowak, Z., Krakowska-Sieprawska, A., Pomastowski, P., Gadzała-Kopciuch, R., Buszewski, B. Isolation of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid - EPA and docosahexaenoic acid - DHA) from diatom biomass using different extraction methods. Algal Research 2022, 62, 102615. [CrossRef]

- Dorgham, M. M., Muftah, A., EI-Deeb, K. Z. Plankton studies in the Arabian Gulf II. The autumn phytoplankton in the Northwestern Area. Arab Gulf J. Scient. Res. Agric. Biol. Sci. 1987, 85 (2), 215-235.

- Dorgham, M. M., Moftah, A. Environmental conditions and phytoplankton in the Arabian Gulf and Gulf Oman, September 1986. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. India 1989, 31 (1&2), 36-53.

- Marella, T. K., Saxena, A., Tiwari, A. Diatom mediated heavy metal remediation: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 305, 123068. [CrossRef]

- Chugh, M., Kumar, L., Shah, M. P. Bharadvaja, N. Algal bioremediation of heavy metals: An insight into removal mechanisms, recovery of by-products, challenges, and future opportunities. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100129. [CrossRef]

- Paniagua-Michel, J., Banat, I. M. Unravelling diatoms’ potential for the bioremediation of oil hydrocarbons in marine environments. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 93–115. [CrossRef]

- Jamali, A. A., Akbari, F., Ghorakhlu, M. M., de la Guardia, M., Yari Khosroushahi, A. Applications of diatoms as potential microalgae in nanobiotechnology. Bioimpacts 2012, 2(2), 83-89. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. K. Residual Contamination and Environmental Effects at the Former Vanda Station, Wright Valley, Antarctica. Waterways Centre for Freshwater Management, University of Canterbury, New Zealand, 2015.

- Zatarain-Palacios, R., Scheggia, S. I. Q., Gaytán-Hinojosa, M. A., Parra-Delgado, H., Salas-Marias, N., Dagnino-Acosta, A., Ceballos-Magaña, S. G., Muñiz-Valencia, R. Morphology and potential antibacterial capability of Actinoptychus octonarius Ehrenberg (Bacillariophyta) isolated from Manzanillo, Colima, in the Mexican Pacific coast. Revista Bio Ciencias 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Elgazali, A., Althalb, H., Elmusrati, I., Ahmed, H. M., Banat, I. M. Remediation approaches to reduce hydrocarbon contamination in petroleum-polluted soil. Microorganisms 2023, 11: 2577. [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, A. D., Kafarov, V. Microalgae based biorefinery: Evaluation of oil extraction methods in terms of efficiency, costs, toxicity, and energy in lab-scale. Revista ION 2013, 26(1), 27-39.

- Jayakumar, S., Bhuyar, P., Pugazhendhi, A., Ab. Rahim, M. H., Maniam, G. P., Govindan, N. Effects of light intensity and nutrients on the lipid content of marine microalga (diatom) Amphiprora sp. for promising biodiesel production. The Science of The Total Environment 2021, 768(1), 145471. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., He, W., Du, M., Zheng, J., Du, X., Li, Y. Design of a microbial remediation inoculation program for petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated sites based on degradation pathways. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(16), 8794. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. E., El-Sayed, A-E. B., Abdel-Wahhab, M. A. Screening of the bioactive compounds in Amphora coffeaeformis extract and evaluating its protective effects against deltamethrin toxicity in rats. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 15185-15195. (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Khumaidi, A., Muqsith, A., Wafi, A., Mardiyah, U., Sandra, L. Phytochemical screening and potential antioxidant of Amphora sp. in different extraction methods. 4TH-ICFAES-2022IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2023, 1221: 012056IOP. (accessed on 14 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mantzorou, A., Navakoudis, E., Paschalidis, K., Ververidis, F. Microalgae: A potential tool for remediating aquatic environments from toxic metals. International journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2018, 15(8). (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Salih, L. I. F., Rasheed, R. O., Muhammed, S. M. Raoultella ornithinolytica as a potential candidate for bioremediation of heavy metal from contaminated environments. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33(7), 895-908. [CrossRef]

- Koolivand, A., Saeedi, R., Coulon, F., Kumar, V., Villaseñor, J., Asghari, F., Faezeh Hesampoor, F. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons by vermicomposting process bioaugmentated with indigenous bacterial consortium isolated from petroleum oily sludge. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2020, 198, 110645. [CrossRef]

- Alabssawy, A. N., Hashem, A. H. Bioremediation of hazardous heavy metals by marine microorganisms: A recent review. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206 (3), 103. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Zhang, Y., Xiong, Z., Chen, X., Sha, A., Xiao, W., Peng, L., Zou, L., Han, J., Li, Q. Peptides used for heavy metal remediation: A promising approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(12), 6717. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., Xiang, G., Xiao, W., Yang, Z., Zhao, B. Microbial mediated remediation of heavy metals toxicity: Mechanisms and prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15-2024. (accessed on 27 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Razaviarani, V., Arab, G., Lerdwanawattana, N., Gadia, Y. Algal biomass dual roles in phycoremediation of wastewater and production of bioenergy and value-added products. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 20, 8199–8216. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, D., Bharadvaja, N. Phycoremediation of effluents containing dyes and its prospects for value-added products: A review of opportunities. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2021, 41, 102080. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, R., Marella, T. K., Kumar, M., Kumar, V., Tiwari, A. Diatom-assisted aquaculture: Paving the way towards sustainable economy. Reviews in Aquaculture 2024, 16 (1), 491-507. (accessed on 28 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Nieri, P., Carpi, S., Esposito, R., Costantini, M., Zupo, V. Bioactive molecules from marine diatoms and their value for the nutraceutical industry. Nutrients 2023, 15 (2), 464. [CrossRef]

- Min, K. H., Kim, D. H., Youn, S., Pack, S. P. Biomimetic diatom biosilica and its potential for biomedical applications and prospects: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(4), 2023. (accessed on 18August 2014). [CrossRef]

- Sisman-Aydin, G. Comparative study on phycoremediation performance of three native microalgae for primary-treated municipal wastewater. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28, 102932. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R. K., Choudhury, A. K. Diatoms: Miniscule biological entities with immense importance in synthesis of targeted novel bioparticles and biomonitoring. J. Biosci. 2021, 46,102. [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi, S., Nguyen-Deroche, N., Caruso, A., Ayadi, H., Morant-Manceau, A., Tremblin, G., Bertrand, M., Schoefs, B. Cadmium, copper, sodium, and zinc effects on diatoms: From heaven to hell – A review. Algologie 2013, 34 (2), 185-225. [CrossRef]

- Soeprobowati, T. R., Hadisusanto, S., Gell, P. The diatom stratigraphy of Rawapening Lake, implying eutrophication history. American Journal of Environmental Science 2012, 8 (3), 334-344. [CrossRef]

- Soeprobowati, T. R., Hariyati, R. The Potential Used of Microalgae for Heavy Metals Remediation. Proceeding The 2nd International Seminar on New Paradigm and Innovation on natural Sciences and Its Application, Diponegoro University, Semarang Indonesia, 72-87, 3 October 2012.

- Mishra, B., Saxena, A., Tiwari, A. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from marine diatoms Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., Thalassiosira sp., and their antibacterial study. Biotechnology Reports 2020, 28, e00571. [CrossRef]

- Barra, L. Greco, S. The potential of microalgae in phycoremediation. In: Aydin S., Microalgae-Current and Potential Application. Intech Open 2023. (accessed on 3 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Das, N., Chandran, P. Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants: An overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011,941810. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A., Tiwari, A., Kaushik, R., Iqbal, H. M. N., Parra-Saldivar, R. Diatoms recovery from wastewater: Overview from an ecological and economic perspective. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2021, 39 (11). [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, K. K., Mishra, L. C., Singh, C. K., Kumar, M. Perspective on the heavy metal pollution and recent remediation strategies. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100166. [CrossRef]

- Melzi, A., Zecchin, S., Gomarasca, S., Abruzzese, A., Lucia Cavalca, L. Ecological indicators and biological resources for hydrocarbon rhizoremediation in a protected area. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12,1379947. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Osman, A. I., Rooney, D. W., Oh, W-D., Yap, P-S. Remediation of heavy metals in polluted water by immobilized algae: Current applications and future perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15 (6), 5128. [CrossRef]

- Karydis, M. Uptake of hydrocarbons by the marine diatom Cyclotella cryptica. Microb. Ecol. 1980, 5, 287-293.

- Elumalai, S., Gopal, R. K., Damodharan, R., Thirumurugan, T., Mahendran, V. Bioaccumulation of Titanium in diatom Cyclotella atomus Hust. Biometals 2024, 37 (1), 71-86. (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Garrido, I., Hampel, M., Lubián, L. M., Blasco, L. J. Sediment toxicity tests using benthic marine microalgae Cylindrotheca closterium (Ehremberg) Lewin and Reimann (Bacillariophyceae). Totoxicology and Environmental Safety 2003, 54 (3), 290-295. [CrossRef]

- Kingston, M. B. Growth and mobility of the diatom Cylindrotheca closterium: Implications for commercial applications. Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science 2009, 125 (4), 138-142.

- Jacques, N. R., McMartin, D. W. Evaluation of algal phytoremediation of light extractable petroleum hydrocarbons in subarctic climates. Remediation Journal 2009, 20(1), 119-132. (accessed on 13 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ding, T., Lin, K., Bao, L., Yang, M., Li, J., Yang, B., Gan, J. Bio-uptake, toxicity and biotransformation of triclosan in diatom Cymbella sp. and the influence of humic acid. Environmental Pollution 2018, 234, 231-242. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, L., Stark, J. S., Snape, I., McMinn, A., Riddle, M. J. Effects of metal and petroleum hydrocarbon contamination on benthic diatom communities near Casey station, Antarctica: An experimental approach. Journal of Phycology 2003, 39 (3), 490-503. [CrossRef]

- Morin, S., Duong, T. T., Dabrin, A., Coynel, A., Herlory, O., Baudrimont, M., Delmas, F., Durrieu, G., Schäfer, J., Winterton, P., Blanc, G., Coste, M. Long-term survey of heavy-metal pollution, biofilm contamination and diatom community structure in the Riou Mort watershed, South-West France. Environmental Pollution 2008, 151 (3), 532-542. [CrossRef]

- Koshlaf, E., Ball, A. S. Soil bioremediation approaches for petroleum hydrocarbon polluted environments. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3(1), 25-49. [CrossRef]

- Cerniglia, C.E.; Gibson, D.T.; Van Baalen, C. Naphthalene metabolism by diatoms isolated from the Kachemak Bay region of Alaska. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1982, 128, 987-990.

- Khan, M. J., Rai, A., Ahirwar, A., Sirotiya, V., Mourya, M., Mishra, S., Schoefs, B., Marchand, J., Bhatia, S. K., Varjani, S., Vinayak, V. Diatom microalgae as smart nanocontainers for biosensing wastewater pollutants: recent trends and innovations. Bioengineered 2021, 12(2), 9531-9549. [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, M., Davis, A. K., Smith, S. R., Traller, J. C., Abbriano, R. The place of diatoms in the biofuels industry. Biofuels 2012, 3(2), 221–240. [CrossRef]

- Polmear, R., Stark, J. S., Roberts, D., McMinn, A. The effects of oil pollution on Antarctic benthic diatom communities. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 90, 33-40. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M. T., Bhaskar, M. V., Tiwari, A. Phycoremediation of eutrophic lakes using diatom algae, Chapter 6. In: Rashed, M. N. (Ed.), Lakes Science and Climate Change. INTECH, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, N., Hamim, H., Sulistyaningsih, Y. C. Phytoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon using three mangrove species applied through tidal bioreactor. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity 2018, 19 (3), 736-742. [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, C., Leflaive, J., Eulin, A., Ten-Hage, L. Bioindicators in marine waters: Benthic diatoms as a tool to assess water quality from eutrophic to oligotrophic coastal ecosystems. Ecological Indicators 2013, 32, 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, S. D.; Cheah, W.; Waiho, K.; Salleh, S.; Fazhan, H.; Manan, H.; Kasan, N. A.; Lam, S. S. Aquatic role of diatoms: From primary producers and aquafeeds. in: Diatoms, CRC Press. pp. 87–104, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Netzer, R., Henry, I. A., Ribicic, D., Brönner, U., Bratstad, O. G. Petroleum hydrocarbon and microbial community structure successions in marine oil-related aggregates associated with diatoms relevant for Arctic conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2018, 135, 759-768 . [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P. K.; Ranjan, S.; Gupta, S. K. Phycoremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon-Polluted Sites: Application, Challenges, and Future Prospects. In: Application of Microalgae in Wastewater Treatment. Springer, 2019. (accessed on 19 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, B. A., Aragaw, T. A., Genet, M. B. Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated soil: A review on principles, degradation mechanisms, and advancements. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12-2024: (accessed on 16 August 20240). [CrossRef]

- Cherifi, O., Sbihi, K., Bertrand, M., Cherifi, K. The removal of metals (Cd, Cu and Zn) from the Tensift riverusing the diatom Navicula subminuscula Manguin: A laboratory study. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 2016, 3 (10), 177-18. (accessed on 24 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. J., Das, S., Vinayak, V., Pant, D., Ghangrekar, M. M. Live diatoms as potential biocatalyst in a microbial fuel cell for harvesting continuous diafuel, carotenoids and bioelectricity. Chemosphere 2022, 291 (1), 132841. [CrossRef]

- González-Dávila, M. The role of phytoplankton cells on the control of heavy metal concentration in seawater. Marine Chemistry 1995, 48 (3-4), 215-236. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Tu, T., Li, S., Cai, M., Huang, X., Zheng, F. Relationship between plankton-based β-carotene and biodegradable adaptability to petroleum-derived hydrocarbon. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124430. [CrossRef]

- Chasapis, C. T., Peana, M., Bekiari, V. Structural identification of metalloproteomes in marine diatoms, an efficient algae model in toxic metals bioremediation. Molecules 2022, 27(2), 378. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H. Y., Grema, M. N., Isa, M. A., Allamin, I. A., Bukar, U. A., Adamu, A., Fardami, A. Y. Petroleum hydrocarbon contamination: Its effects and treatment approaches-A mini review. Arid Zone Journal of Basic and Applied Research 2022, 1 (6), 81-93. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ávila, J., Salinas-Rodríguez, E., Cerecedo-Sáenz, E., Reyes-Valderrama, Ma. I., Arenas-Flores, A., Román-Gutiérrez, A. D., Rodríguez-Lugo, V. Diatoms and their capability for heavy metal removal by cationic exchange. Metals 2017, 7 (5), 169: . [CrossRef]

- Truskewycz, A., Gundry, T. D., Khudur, L. S., Kolobaric, A., Taha, M., Aburto-Medina, A., Ball, A. S., Shahsavari, E. Petroleum hydrocarbon contamination in terrestrial ecosystems-fate and microbial responses. Molecules 2019, 24(18), 3400. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M-S., Huang, C-Y., Lin, Y-C., Lin, S-L., Hsiao, Y-H., Tu, P-C., Cheng, P-C., Cheng, S. F. Green remediation technology for total petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil. Agronomy 2022, 12(11), 2759; [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S., Maddela, N. R., Megharai, M., Venkateswarlu, K. Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons – Environmental Fate, Toxicity, and Remediation. Springer, 2020. ISBN 978-3-030-24034-9 ISBN 978-3-030-24035-6 (eBook). [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, R., Ramalingam, K., Periyanayagi, R., Sasikala, V., Balasubramanian, T. Antibacterial activity of marine diatom Rhizosolenia alata (Brightwell.1958) against human pathogen. Research Journal of Environmental Toxicology 2007, 2(1), 98-100. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Garcia, S., Pande, P., Seguin, A., St-Arnaud, M., Yergeau, E. Rhizoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons: a model system for plant microbiome manipulation. Microbial Biotechnology 2018, 11(5), 819-832. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Wang, X., Liu, S., Kong, X., Wang, P., Xu, T. Long-term petroleum hydrocarbons pollution after a coastal oil spill. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10 (10), 1380; [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. A.; Sridhar, S.; Jayappriyan, K. R.; Raja, R. Applications of microalgae in aquaculture feed, Chapter 33. In: Handbook of Food and Feed from Microalgae, Production, Application, Regulation, and Sustainability, 2023. pp.421-433 . [CrossRef]

- Shishlyannikov, S., Nikonova, A. A., Klimenkov, I. V., Gorshkov, A. Accumulation of petroleum hydrocarbons in intracellular lipid bodies of the freshwater diatom Synedra acus subsp. Radians. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24(1), 275–283. [CrossRef]

- Parab, S. R., Pandit, R., Kadam, A. N., Indap, M. Effect of Bombay high crude oil and its water-soluble fraction on growth and metabolism of diatom Thalassiosira sp. Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences 2008, 37(3), 251-255.

- Nurachman, Z., Hartati, Anita, S., Anward, E. E., Novirani, G., Mangindaan, B., Gandasasmita, S., Syah, Y. M., Panggabean, L. M. G., Suantika, G. Oil productivity of the tropical marine diatom Thalassiosira sp. Bioresource Technology 2012, 108, 240-244. [CrossRef]

- Kamalanathan, M., Chiu, M. H., Bacosa, H., Schwehr, K., Tsai, S. M., Doyle, S., Yard, A., Mapes, S., Vasequez, C., Bretherton, L., Sylvan, J. B., Santschi, P., Chin, W. C., Quigg, A. Role of polysaccharides in diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana and its associated bacteria in hydrocarbon presence. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180(4), 1898-1911. [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, T., Boyce, C. P. Cleanup standards for petroleum hydrocarbons, part 1. Review of methods and recent developments. Journal of Soil Contamination 1993, 2(2), 109-124. [CrossRef]

- Alaidaroos, B. A. Advancing eco-sustainable bioremediation for hydrocarbon contaminants: Challenges and solutions. Processes 2023, 11(10), 3036. [CrossRef]

- Shniukova, E. I., Zolotareva, E. K. Diatom exopolysaccharides: A review. International Journal on Algae 2015, 17(1), 50-67. [CrossRef]

- Chernikova, T. N., Bargiela, R., Toshchakov, S. V., Shivaraman, V., Lunev, E. A., Yakimov, M. M., Thomas, D. N., Golyshin, P. N. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria Alcanivorax and Marinobacter associated With Microalgae Pavlova lutheri and Nannochloropsis oculata. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 572931. [CrossRef]

- Soeprobowati, T. R., Hariyati, R. Phycoremediation of Pb+2, Cd+2, Cu+2, and Cr+3 by Spirulina platensis (Gomont) Geitler. American Journal of BioScience 2014, 2 (4), 165-170. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R. F., Yasseen, B. T. Phytoremediation of polluted soils and waters by native Qatari plants: Future perspectives. Environmental Pollution 2020, 259, 113694. [CrossRef]

- Yasseen, B. T., Al-Thani, R. F. Endophytes and halophytes to remediate industrial wastewater and saline soils: Perspectives from Qatar. PLANTS 2022, 11(11), 1497. https:// doi.org/10.3390/plants1111149.

- Yasseen, B. T. Phytoremediation of industrial wastewater from oil and gas fields using native plants: The research perspectives in the State of Qatar. Scholars Research Library, Central European Journal of Experimental Biology 2014, 3 (4), 6-23.

- Al-Thani, R. F., Yasseen, B. T. Possible future risks of pollution consequent to the expansion of oil and gas operations in Qatar. Environment and Pollution 2023, 12 (1), 12-52.

- Xu, X., Liu, W., Tian, S., Wang, W., Qi, Q., Jiang, P., Gao, X., Li, F., Li, H., Yu, H. Petroleum hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria for the remediation of oil pollution under aerobic conditions: A perspective analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2885. [CrossRef]

- Cerniglia, C. E. Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Biodegradation 1992, 3, 351–368.

- Bagi, A., Knapik, K., Baussant, T. Abundance and diversity of n-alkane and PAH-degrading bacteria and their functional genes – Potential for use in detection of marine oil pollution. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 810, 152238. [CrossRef]

- Brott, S., Nam, K. H., Thomas, F., Dutschei, T., Reisky, L., Behrens, M., Grimm, H. C., Michel, G., Schweder, T., Bornscheuer, U. T. Unique alcohol dehydrogenases involved in algal sugar utilization by marine bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107 (7-8), 2363-2384. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H., Furtmann, C., Lenz, F., Srinivasamurthy, V., Bornscheuer, U. T., Jose, J. Enzyme cascade converting cyclohexanol into ε-caprolactone coupled with NADPH recycling using surface displayed alcohol dehydrogenase and cyclohexanone monooxygenase on E. coli. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15(8), 2235-2249. [CrossRef]

- Lisicki, D., Orlińska, B., Marek, A. A., Bińczak, J., Krzysztof Dziuba, K., Martyniuk, T. Oxidation of cyclohexane/cyclohexanone mixture with oxygen as alternative method of adipic acid synthesis. Materials 2023, 16(1), 298. [CrossRef]

- Witthoff, S., Mühlroth, A., Marienhagen, J., Bott, M. C1 metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum: An endogenous pathway for oxidation of methanol to carbon dioxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79 (22), 6974-83. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y., Hopkinson, B. M., Nakajima, K., Dupont, C. L., Tsuji, Y. Mechanisms of carbon dioxide acquisition and CO2 sensing in marine diatoms: A gateway to carbon metabolism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372 (1728), 20160403. [CrossRef]

- https://www.mpg.de/20293586/0512-terr-formic-acid-carbon-dioxide-neutrality-153410-x. (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- https://www.metlink.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FAQ6_2.pdf. (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Singh, R., Guzman, M. S., Bose, A. Anaerobic oxidation of ethane, propane, and butane by marine microbes: A mini review. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2056. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R. F., Yasseen, B. T. Perspectives of future water sources in Qatar by phytoremediation: Biodiversity at ponds and modern approach. International Journal of Phytoremediation 2021, 23 (8), 866-889. [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, P. W. Cyclohexanone 1,2-monooxygenase from Acinetobacter NCIMB 9871, Chapter 12. Methods in Enzymology 1990, 188, 70-77. [CrossRef]

- Barclay, S. S. The Production and Use of Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase for Baeyer-Villiger Biotransformation. Ph. D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2017.

- Kelly, S. L., Kelly, D. E. Microbial cytochromes P450: Biodiversity and biotechnology. Where do cytochromes P450 come from, what do they do and what can they do for us? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2013, 368 (1612), 20120476. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Shephard, E. A. Mutation, polymorphism, and perspectives for the future of human flavin-containing monooxygenase 3. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2006, 612 (3), 165-171. [CrossRef]

- De Gonzalo, G., Coto-Cid, J. M., Lončar, N., Fraaije, M. W. Asymmetric sulfoxidations catalyzed by bacterial flavin-containing monooxygenases. Molecules 2024, 29 (15), 3474. [CrossRef]

- Widdel, F., Rabus, R. Anaerobic biodegradation of saturated and aromatic HCs. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2001, 12 (3), 259-76. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, R. F., Yasseen, B. T. Microbial ecology of Qatar, the Arabian Gulf: Possible roles of microorganisms. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 697269. [CrossRef]

- Marella, T. K.; Bhaskar, M. V.; Tiwari, A. Phycoremediation of eutrophic lakes using diatom algae. In: Lake Sciences and Climate Change, 2016. (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kalia, A., Sharma, S., Semor, N., Babele, P. K., Sagar, S., Bhatia, R. K., Walia, A. Recent advancements in hydrocarbon bioremediation and future challenges: A review. 3 Biotech. 2022, 12(6), 135. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K. M. Barriers to horizontal gene transfer by natural transformation in soil bacteria. APMIS 1998, 106, 77-84.

- Beiko, R. G., Harlow, T. J., Ragan, M. A. Highways of gene sharing in prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 14332–14337.

- Hanin, M., Ebel, C., Ngom, M., Laplaze, L., Masmoudi, K. New insights on plant salt tolerance mechanisms and their potential use for breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1787. [CrossRef]

- Suchanova, J. Z., Bilcke, G., Romanowska, B., Fatlawi, A., Pippel, M., Skeffington, A., Schroeder, M., Vyverman, W., Vandepoele, K., Kröger, N., Poulsen, N. Diatom adhesive trail proteins acquired by horizontal gene transfer from bacteria serve as primers for marine biofilm formation. New Phytologist 2023, 240, 770–783. [CrossRef]

- Zhaxybayeva, O., Gogarten, J. P., Charlebois, R. L., Doolittle, W. F., Papke, R. T. Phylogenetic analyses of cyanobacterial genomes: Quantification of horizontal gene transfer events. Genome Res. 2006, 16, 1099–108.

- Das, N., Das, A., Das, S., Bhatawadekar, V., Pandey, P., Choure, K., Damare, S., Pandey, P. Petroleum hydrocarbon catabolic pathways as targets for metabolic engineering strategies for enhanced bioremediation of crude-oil-contaminated environments. Fermentation 2023, 9(2), 196; [CrossRef]

| Genus | No. of species | Remediation of organic and inorganic components | Remarks and other possible roles | References** |

| Achnanthes | 1 | * | Needs testing; some roles have been reported | [38,39] |

| Actinoptychus | 1 | * | Needs testing; shows antibacterial activity | [40,41] |

| Amphiprora | 4 | * | Needs testing; biofuels and oil production have been reported | [42,43,44] |

| Amphora | 7 | * | Needs testing; produces bioactive compounds such as antioxidants, and against toxicities of some living organisms | [44,45,46] |

| Asterolampra | 1 | * | Needs testing; might remediate heavy metals | [44,47,48] |

| Asteromphalus | 3 | * | Needs testing; might remediate heavy metals | [4,44,49,50] |

| Auliscus | 1 | * | Needs testing; might remediate heavy metals | [2,35,51,52] |

| Bacillaria | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; degradation, speciation, and detoxification of chemical wastes and hazardous metals | [2,35,53] |

| Bacteriastrum | 6 | * | Needs more investigation; possesses sustainable metabolic efficacy to remediate diverse wastewater | [2,35,54] |

| Bellerochea | 1 | * | More studies are needed; produces nutritional agents, bioactive molecules lipids, polysaccharides, proteins, pigments, vitamins, bio-pharmacological activities, and nutraceutical applications; promotes the health and survival of aquatic species like fish, bivalves, and shrimp | [2,35,55,56,57] |

| Biddulphia | 6 | * | More studies are needed as many bioactive compounds are produced and nutritional values were reported | [2,35,56,58] |

| Campylodiscus | 3 | * | More studies are needed; can reduce the toxicity of heavy metals by enhancing extracellular adsorption; might be used in improving water quality | [2,35,41,59] |

| Cerataulina | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; activates defense mechanisms such as the production of antioxidants and metal chelators | [2,35,60] |

| Chaetoceros | 34 | * | Variety of applications and silver nanoparticles (Ag NP) that hold immense therapeutic potential against pathogenic microbes; other applications of a least toxicity and biodegradable nature; remediate heavy metals such as Cd, Cu, and Pb | [61,62,63] |

| Climacodium | 1 | * | More investigation needed; reduces heavy metal toxicity, wastewater treatment, biomass can be turned into biofuels, biofertilizers, nutritional supplements for animal production;used for pharmaceutical applications | [2. 35, 41, 57, 64] |

| Climacosphenia | 1 | * | Further investigation is needed, as it might identify various peptides that facilitate the accumulation of heavy metals and contribute to mechanisms that defend against them | [52,65] |

| Genus | No. of species | Remediation of organic and inorganic components | Remarks and other possible roles | References** |

| Cocconeis | 1 | * | Survive polluted seawater and removal of heavy metals; pollution bioindicator; production of some important bioactive agents at various aspects, such as energy, pharmaceuticals, and aquaculture feedstocks | [57,66,67,68] |

| Corethron | 2 | * | More investigation is needed; could remove heavy metals by adsorption and bioaccumulation; bioindicator for heavy metal pollution | [44,59,60] |

| Coscinodiscus | 10 | * | Needs testing; possible roles in maintaining marine ecosystems; might have direct and indirect benefits for humans | [11,41] |

| Coscinosira | 1 | * | Needs testing; might survive polluted seawater and remediate and remove heavy metals, pollution bioindicators; production of some important bioactive agents for various aspects, such as energy, pharmaceuticals, and aquaculture feedstocks | [41,57,67,69] |

| Cyclotella | 2 | Uptake petroleum hydrocarbons and heavy metals | More research needed; accumulates titanium, detoxication of heavy metals | [70,71] |

| Cylindrotheca | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; one species, C. closterium, proved suitable for sediment heavy metal toxicity tests | [41,72,73] |

| Cymbella | 1 | * | More research needed; can be used to remediate some pollutants in sewage sludge such as triclosan | [44,74,75] |

| Dactyliosolen | 1 | * | Needs confirmation; possible removal of heavy metals by adsorption, and bioaccumulation; bioindicator for heavy metal pollution | [59,65] |

| Diatoma | 1 | * | Needs confirmation; possible role in heavy metal remediation | [65,68] |

| Diploneis | 9 | * | Needs testing; possible remediation candidate for heavy metals | [44] |

| Ditylum | 2 | * | Needs testing; possible heavy metal remediation | [41] |

| Epithemia | 1 | * | Needs testing and more investigation | [65] |

| Ethmodiscus | 1 | * | Needs testing and more investigation | [ 41, 65] |

| Eucampia | 2 | * | Needs testing and more investigation | [41,65] |

| Fragilaria | 4 | * | Needs testing; benthic diatoms are sensitive to sediment contamination; can be used to monito, resist, and accumulate Cd and Zn | [68,76,77] |

| Genus | No. of species | Remediation of organic and inorganic components | Remarks and other possible roles | References** |

| Glyphodesmis | 1 | * | Needs testing and more investigation | [41,78] |

| Gossleriella | 1 | * | Requires further testing and investigation; acts as smart nanocontainers capable of adsorbing various trace metals, dyes, polymers, and drugs, some of which are hazardous to human and aquatic life | [57,79,80] |

| Grammatophora | 1 | * | Needs testing and more investigation; may play a role in degradation, speciation, and detoxification of chemical waste and hazardous metals | [2,35,65] |

| Guinardia | 1 | * | Needs testing and more investigation; can reduce the toxicity of heavy metals by enhancing extracellular adsorption | [2,35,65] |

| Gyrosigma | 2 | Promising role in phyco-remediation and as a pollution indicator | More investigation is needed; can be used as agent for wastewater treatment and biofuels research | [81,82,83,84] |

| Hemiaulus | 3 | * | Further investigation is needed into possible role in metal pollution and its impact on essential processes, such as nitrogen fixation, food production, and climate change mitigation through CO2 utilization | [59,85,86] |

| Hemidiscus | 2 | * | Needs more investigation; possible remediation of heavy metals | [ 2, 35, 74,] |

| Hydrosilicon | 1 | * Possible role in industrial effluents |

Needs more investigation; phycoremediation proved in some diatoms | [74,80] |

| Lauderia | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; phycoremediation of heavy metals is possible | [2,35,65] |

| Leptocylindrus | 1 | * Possible candidate for phycoremediation of industrial effluents |

Needs a proof; possible role in heavy metal remediation | [2,35,59,87] |

| Licmophora | 2 | Possible candidate for phycoremediation | Needs testing; possible roles in maintaining marine ecosystems | [11,74,88] |

| Mastogloia | 1 | * | More investigation is needed; possible detoxification of chemical wastes and hazardous metals from polluted sites; might remediate heavy metals | [2,35,65,89] |

| Melosira | 1 | * | More investigation is needed; possible role in heavy metal remediation | [68,74] |

| Navicula | 8 | Remediates petroleum hydrocarbons | More investigation is needed; proved efficient in removing Cd, Cu, and Zn from polluted sites; production of biofuels is very possible | [42,74,76,90] |

| Nitzschia | 14 | Remediates petroleum hydrocarbons | More investigation is needed; could remediate heavy metals and dyes | [2,35,36,74,91] |

| Genus | No. of species | Remediation of organic and inorganic components | Remarks and other possible roles | References** |

| Paralia | 1 | * | Needs testing; indicator of pollution; could be potent metal bioremediation agent | [2,35,36,37] |

| Pinnularia | 1 | * | Needs more testing; can remediate various pollutants, such as heavy metals, dyes, and hydrocarbons detected in wastewater | [37,80] |

| Plagiogramma | 1 | * | Needs testing; increases the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)#, which bind to the metal nanoparticles outside the cell | [37,59] |

| Planktoniella | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; might assimilate heavy metals, tolerate heavy metals; biological pollution indicator of water quality; efficient model in assimilation and detoxification of toxic metal ions | [92,93,94,95] |

| Pleurosigma | 9 | * | Needs more investigation; possible heavy metal remediation | [2,35,41,96] |

| Podocystis | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; might survive polluted seawater and remediate heavy metals; produces some bioactive agents in various aspects of energy, pharmaceuticals, and aquaculture feedstocks | [69,97,98] |

| Podosira | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; possible role in heavy metal remediation | [2,35,49] |

| Rhabdonema | 2 | * | Needs more investigation; possible role in heavy metal remediation | [41,59,97] |

| Raphoneis | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; might activate defense mechanisms, such as the production of antioxidants and/or metal chelators; possible metal remediation | [60,96,99] |

| Rhizosolenia | 22 | * | Needs further investigation; extracts of these species might have antibacterial activity against human pathogens | [37,68,100] |

| Rhoicosigma | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; might remediate heavy metals | [67,101,102] |

| Schroederella | 1 | * | Needs testing; can reduce the toxicity of heavy metals; possible biosensing pollution; might be ideal bioindicators | [2,35,41,80] |

| Skeletonema | 1 | * | Needs further investigation; contains some important bioactive compounds, such as vitamins, polyunsaturated fatty acids, polysaccharides, and pigments; biological indicators; can reduce the toxicity of heavy metals | [44,94,103] |

| Genus | No. of species | Remediation of organic and inorganic components | Remarks and other possible roles | References** |

| Stauroneis | 2 | * | Needs more investigation; might remediate heavy metals; could increase the production of EPS# to bind metal nanoparticles outside the cell | [44,49,59] |

| Streptotheca | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; can reduce the toxicity of heavy metals by enhancing extracellular adsorption | [2,35,41] |

| Striatella | 2 | * | Needs more investigation; might play a role in detoxification of heavy metals | [49,65,67,101] |

| Surirella. | 8 | * | Needs more investigation; might remediate heavy metals | [44,80] |

| Synedra | 3 | * Remediate hydrophobic hydrocarbons from aquatic systems |

More investigation is needed; might produce potent metal bioremediation | [2,35,104] |

| Thalassionema | 1 | * | Needs more investigation; might remediate heavy metals | [2,35,44] |

| Thalassiosira | 2 | Degrade and remediate petroleum hydrocarbons | More investigation is needed to study the phycoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons of oil and gas activities; has been used for genetic manipulation to study many physiological activities including silica biomineralization; Possible biofuel production | [13,105,106,107] |

| Thalassiothrix | 4 | * | Needs further investigation; might help to maintain and stabilize heavy metals, and increase the production of EPS | [44,59,97] |

| Trachyneis | 1 | Little work has been done | Needs testing and investigation; might be useful for heavy metal remediation and bioindicators | [98,108] |

| Triceratium | 5 | * | Needs more investigation; might offer several advantages as potent metal bioremediation agent | [2,35,44,49] |

| Tropidoneis | 1 | * | Further investigation is needed as it might be capable of heavy metal remediation and could increase the production of EPS, boosting resistance against various environmental stresses, including pollution | [41,59,109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).