1. Introduction

Temporary water bodies are globally widespread and their prevalence is increasing with climate change, consequently enhancing their significance for biodiversity [

2]. A seasonally managed artificial lake under anthropogenic control provides an opportunity to monitor colonization patterns and evaluate the role of its faunal communities. This contributes to an enhanced understanding of faunal community formation processes in temporary water bodies. Temporary lakes can maintain high species richness due to their substantial variability in volume and persistence duration, occasionally rendering them biodiversity hotspots [

3,

4,

5]. Consequently, these systems have attracted attention in biodiversity conservation programs [

6].

Zooplankton communities are vital components of biodiversity in freshwater ecosystems, and the study of their formation mechanisms is a key topic in freshwater ecology research. Copepods constitute the primary representatives of the zooplankton community in these lakes. Different species exhibit preferences regarding the duration of the aquatic phase, establishing them as crucial ecosystem components and indicators of hydroperiod (HP) length [

7]. In natural basins, species richness correlates with HP duration and lake age, as well as predatory pressure [

8,

9,

10,

11].

The present investigation aims to characterize the origin and development of zooplankton and macrozoobenthos communities in the artificial Lake Ariana. The focus is on community structure, expressed through species composition and colonization periodicity [

2]. Additionally, factors influencing faunal community formation under anthropogenically regulated environmental conditions are investigated. The regulation of the lake's hydrological regime through its flow-through nature exerts significant influence on the structuring of zooplankton and macrozoobenthos communities.

2. Materials and Methods

The Ariana Lake is an artificial flow-through water body located in the lower section of Borisova Garden Park (42°41'22" N, 23°20'12" E) in the central part of Sofia, Bulgaria, at an altitude of 550 meters (

Figure 1).

The lake has a surface area of 1.3 hectares. It was originally constructed in 1893, and in 1899, it underwent expansion, acquiring its present morphology, which includes an island in its central part.

The lake is supplied with water from a borehole located within Borisova Garden Park, while its outflow is directed into the Perlovska River, which flows in close proximity to the park. The hydrological regime of the lake is characterized by seasonal filling at the end of May or the beginning of June, followed by annual drainage in September. The lake has a concrete bottom and walls, with an average depth of approximately 80 centimeters. Prior to each filling cycle in the spring season, the lake undergoes a mechanical cleaning process to remove accumulated sediments and pollutants.

The samples were collected from April/May to August 2013 to 2015. Two samples was collected from 2013, three from 2014, and six from 2015. Total of 22 samples were collected, of which 11 were planktonic and 11 benthic. Main physical and chemical parameters like temperature (С); dissolved oxygen content (mg/l) and oxygen saturation (%); active reaction (pH) and electroconductivity (µS/cm3), were measured in situ using a WTW Multi 1975i multi-parameter system. The nutrients recorded were: nitrate nitrogen (N-NO3); total nitrogen (TN); phosphates (P-PO4); total phosphorus (TP(PO4). Their concentrations were measured photometrically by a WTW PhotoFlex portable photometer according to WTW methodology.

The MZB samples were collected according to EN ISO 9391:1995; EN 28265:1994; EN 27828:1994 standards. The laboratory processing of the MZB materials included sorting samples by weeks, months, and years and taxonomic determination on an MBS-9 stereomicroscope. Taxonomic determination of benthos was done after Kutikova and Starobogatov [

12]. The current systematic status of the organisms is consistent with Taxonomic hierarchy ver. 4.1.

The zooplankton samples were collected by filtering a volume of 100 l of water through an Apstein plankton net, with a 76 µm mesh size. Materials with a working volume of up to 100 ml are processed in the laboratory. Quantitative processing: by counting the organisms in 10 ml in a Bogorov chamber at 16x magnification under a stereomicroscope. Quality processing: on the entire volume. An Olympus BX5 compound microscope was used for genus and species determination. The abundance was represented for m

3. Taxonomic determination of Cladocera was done according to Kutikova and Starobogatov [

12]; Copepoda – according to Bledzki and Rybak [

13].

K (Abundance-Biomass Comparison) Curves of Abundance and Biomass [

14] – A method used to compare the distribution of numerical abundance and biomass among taxa to assess ecological conditions. In k-dominance curves the cumulative relative abundances of species, ranked in decreasing order of their importance in terms of abundance (or biomass), are plotted against species rank, or more usually log species rank. The higher the curve in a k-dominance plot, and the more quickly it reaches its maximum value (of 100), the lower the evenness and richness components of diversity.

Geometric Curves of Abundance [

15] – A graphical representation of the number of taxa categorized by different abundance levels. The interpretation is based on the principle that in undisturbed or relatively less impacted sites, the number of low-abundance taxa is high.

Diversity indices (Shannon, Margalef, Pielou, and Simpson) were calculated using PRIMER 6 & PERMANOVA+. Excel 2007 was used to visualize settlement dynamics and relative abundances of different taxonomic groups.

Trophic interactions were modelled using Loop Analysis (LA) through PowerPlay software from Oregon State University. This approach classifies interactions using symbols {-, 0, +} to construct a community matrix and assess ecosystem stability via polynomial equations solved using the Euclidean algorithm and the Routh-Hurwitz theorem.

3. Results and Discussion

The stable physicochemical conditions of the lake, maintained by its flowing nature, led to small fluctuations in different years, influenced mainly by atmospheric conditions (

Table 1).

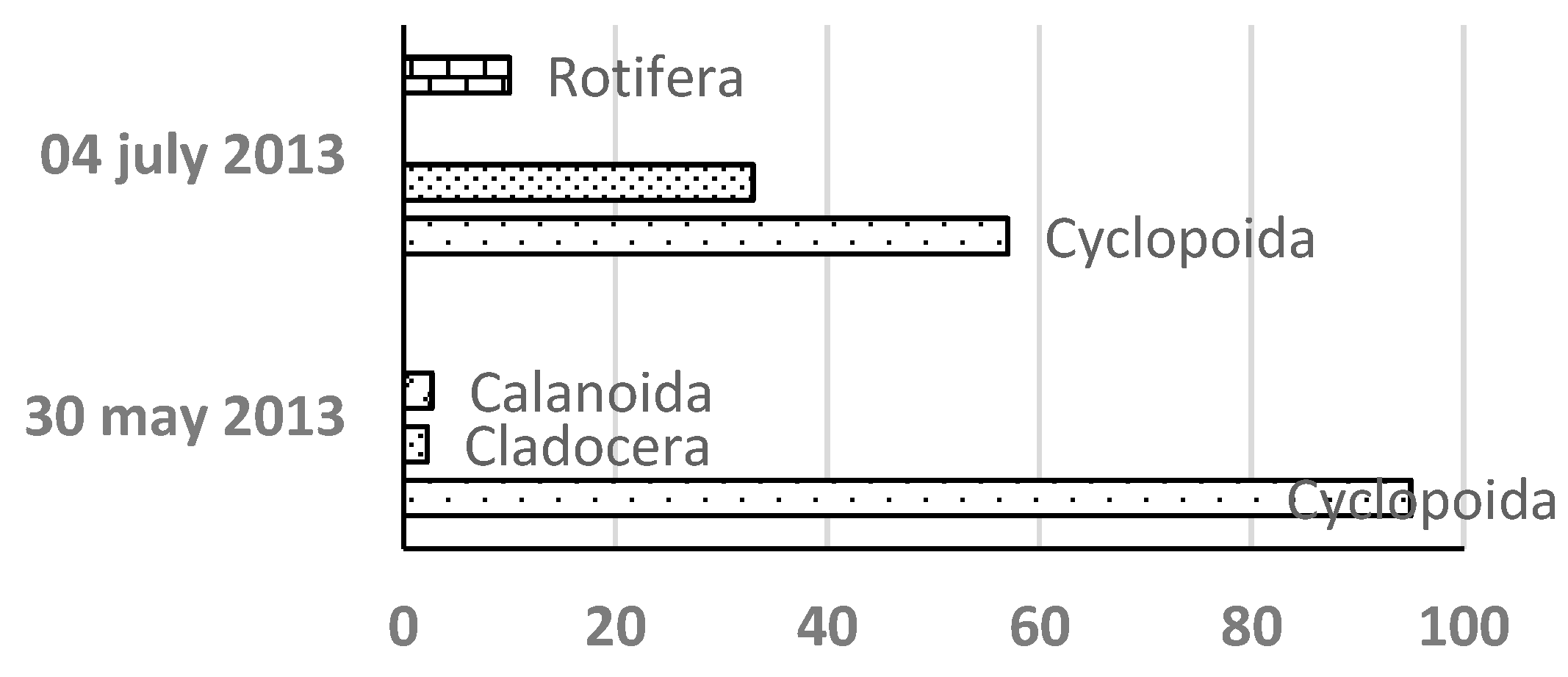

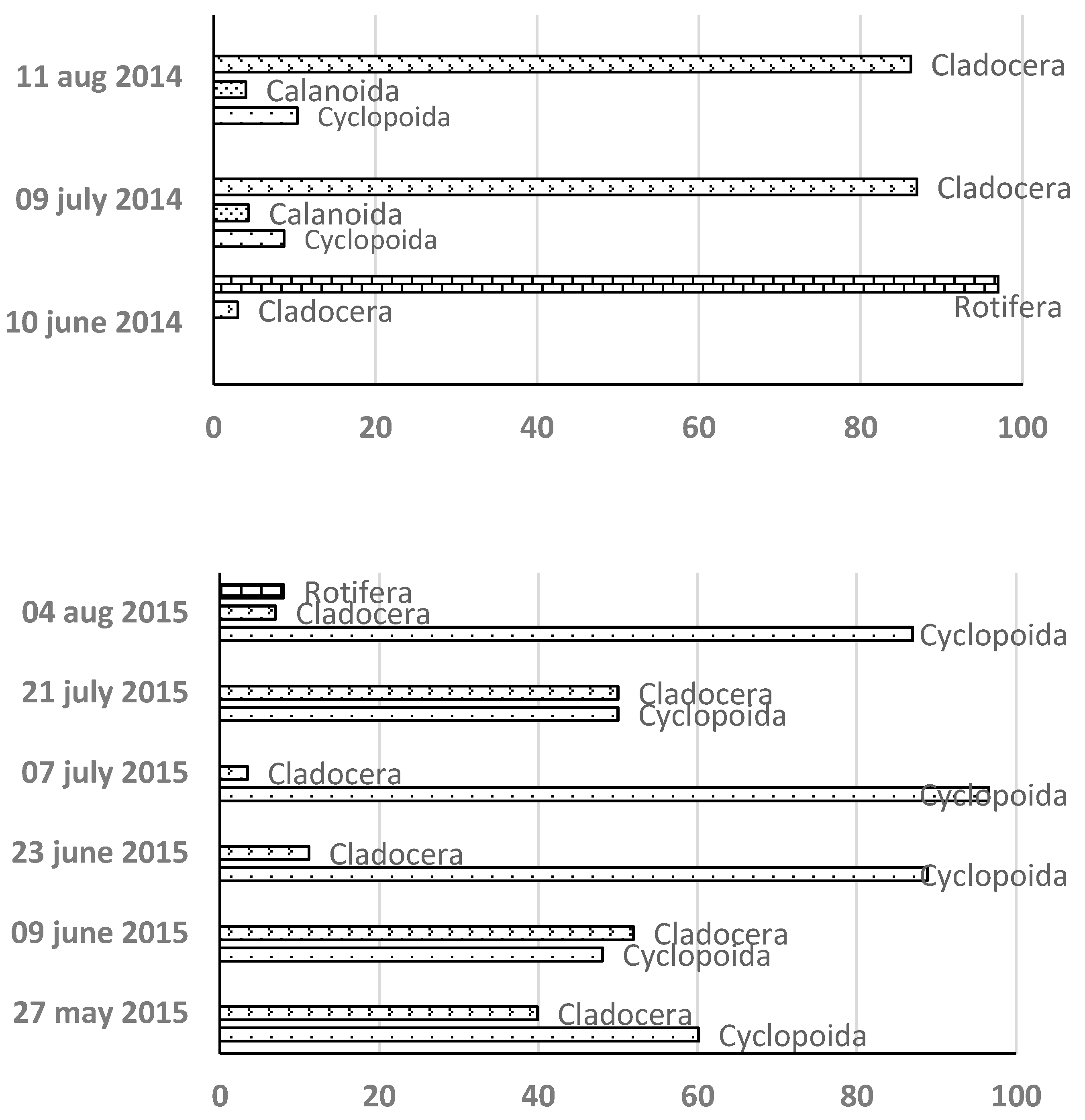

Over three years, 24 zooplankton taxa were identified: 10 in 2013, 9 in 2014, and 15 in 2015. Cyclopoid copepods were the dominant taxa, followed by cladocerans and rotifers, whereas calanoid copepods were infrequently observed.

In 2013 and 2015, cyclopoid copepods initially dominated (95% and 60%, respectively) (

Figure 2). However, in 2014, rotifers were the initial dominant group (97%), followed by cladocerans (80%), with copepods remaining a minor fraction.

Key species included

Acanthocyclops robustus (2013) and

Thermocyclops dybowskii (2015), both typical of shallow lakes. They are characteristic of reservoirs with active reaction values of about 7, which probably explains their significant presence in the first stages of the hydroperiod during these two years [

5,

6]. Cladocerans, mainly

Daphnia longispina and

Scapholeberis kingi, exhibited rapid growth and adaptability. Both species are characteristic of small lakes, fast-growing, and unpretentious to the amount of electrolytes in the water, especially

Scapholeberis kingi [

7,

8]. Rotifers were represented primarily by

Lecane Brachionus and

Platiyas genera. The 2014 community was unique with

Euchlanis and

Trichotria rotifers dominating (96%) along with cladocerans

D. longispina and

Moina rectirostris. In the later stages

Simocephalus vetulus also appeared which is characteristic of newly formed reservoirs [

9].

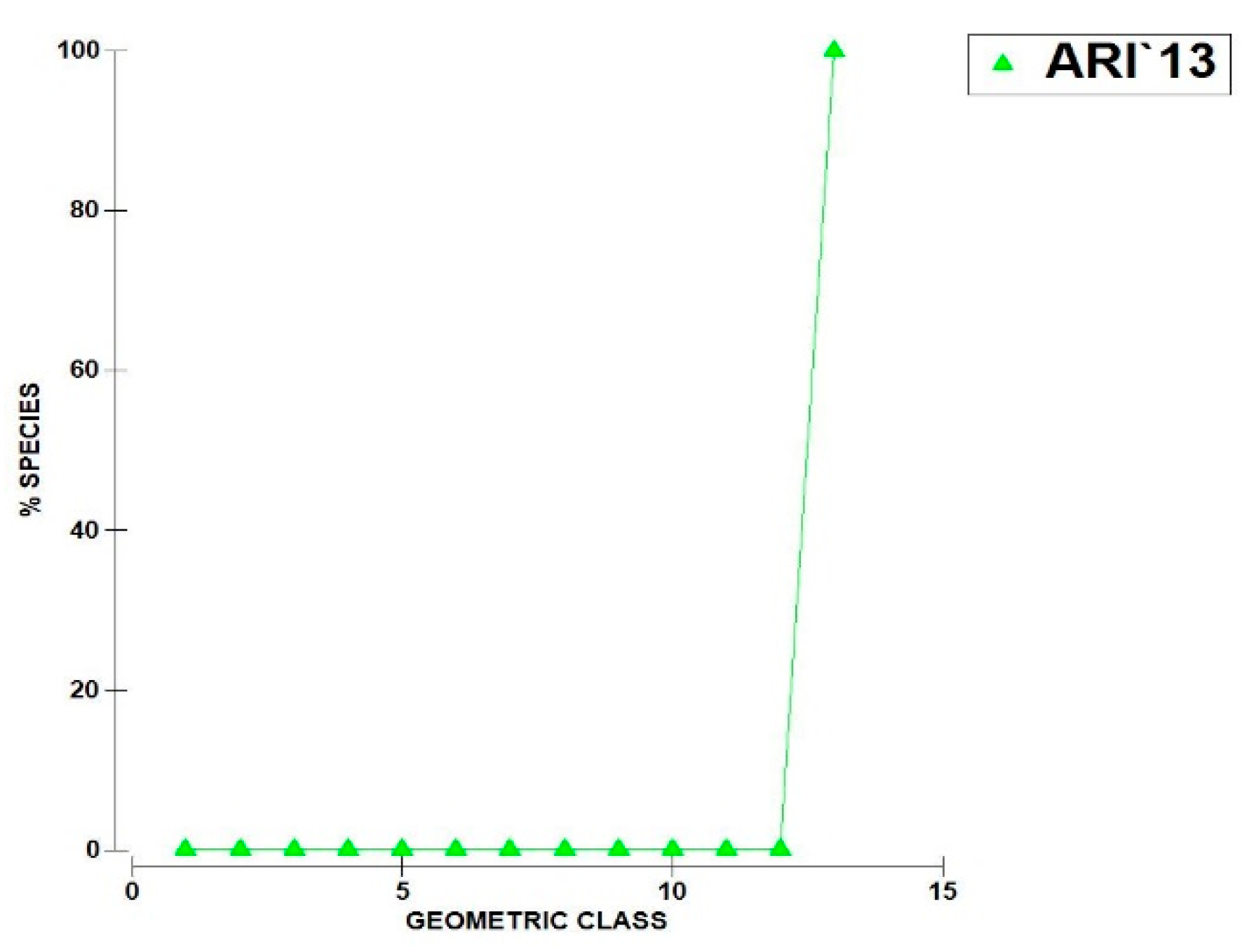

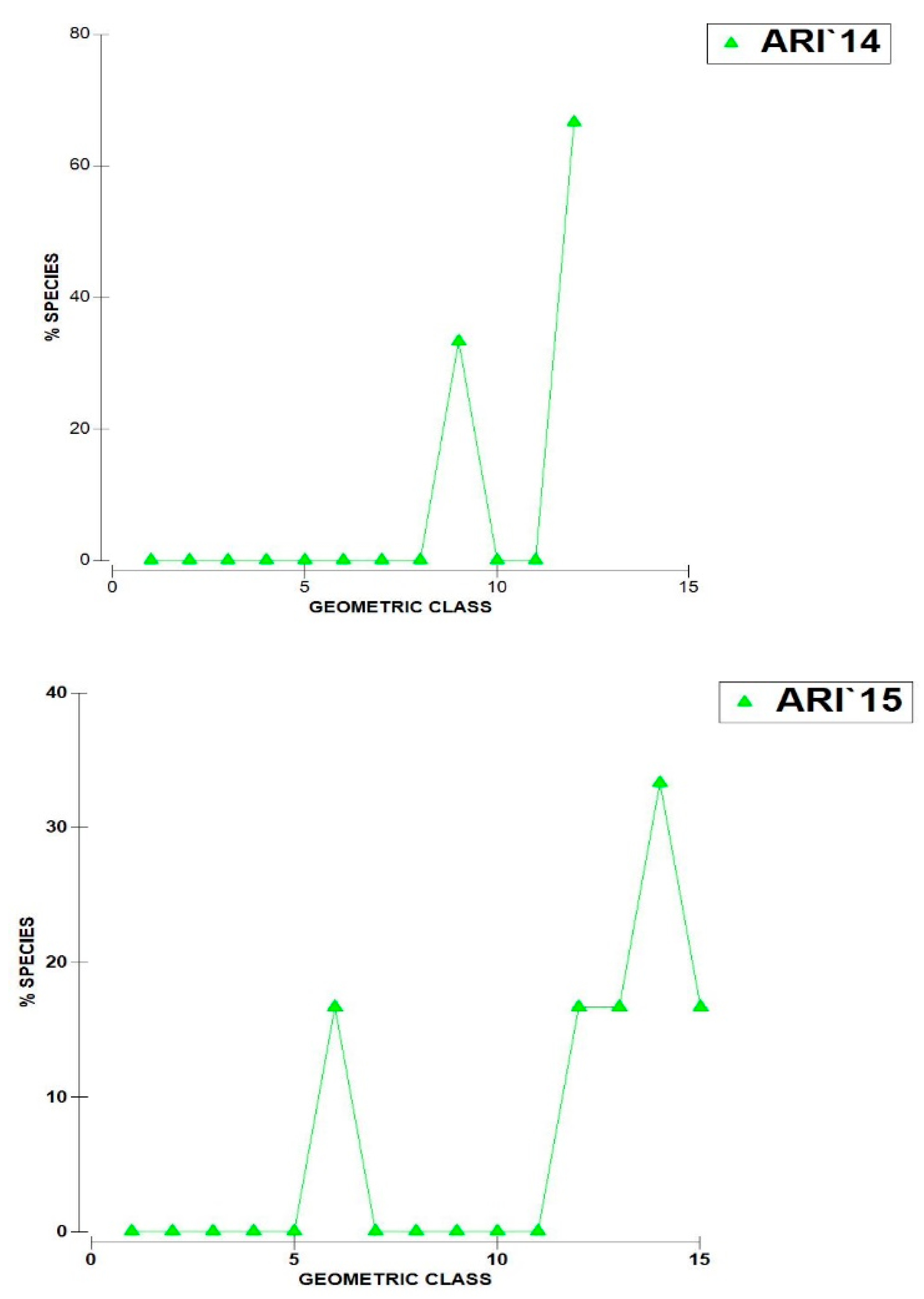

The

geometric curves of abundance (

Figure 3) indicate a relatively even distribution of a small number of rare species with only two to three taxa exhibiting peak abundance. This pattern is particularly pronounced in 2013 although it is likely influenced by the limited number of samples collected (only two).

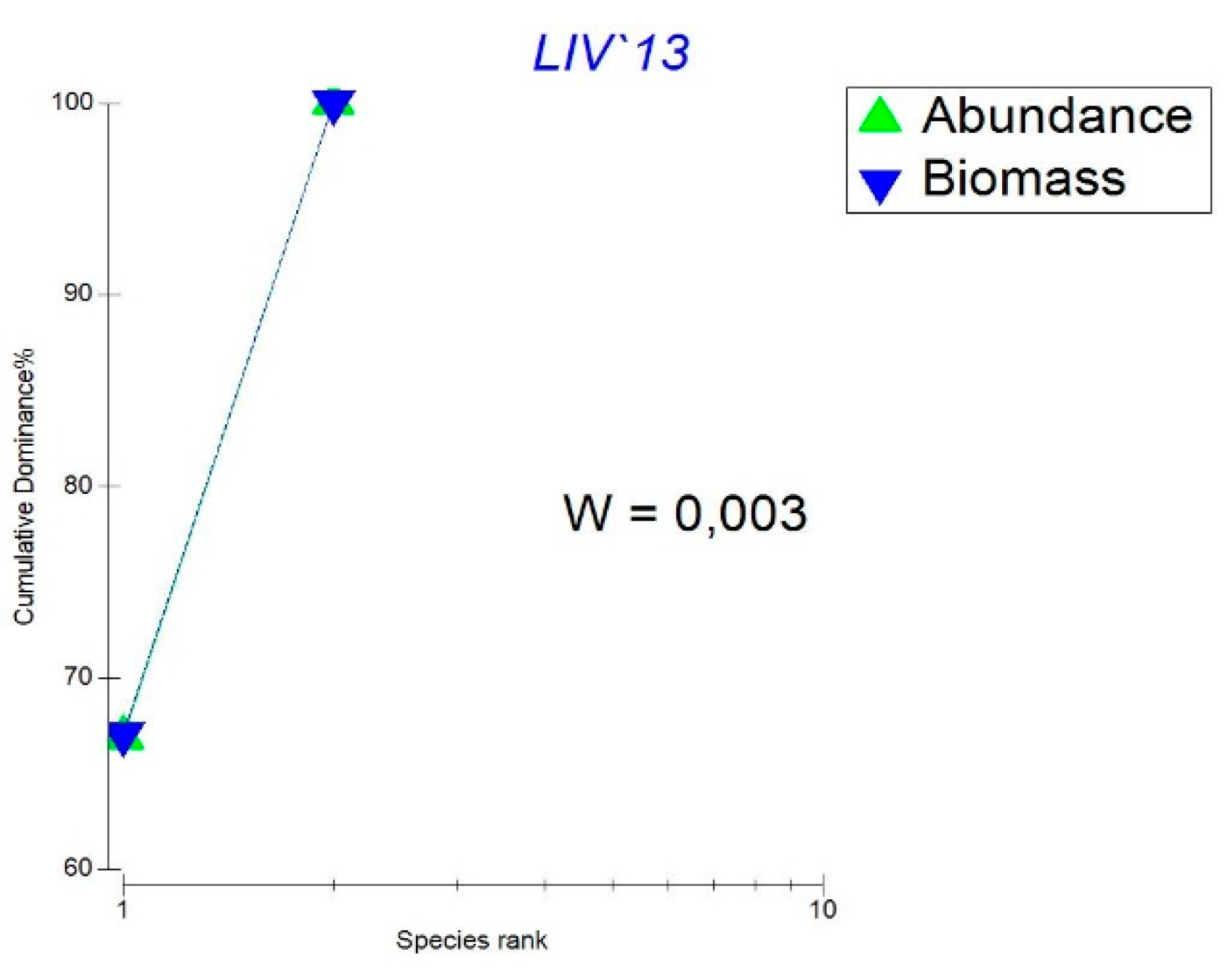

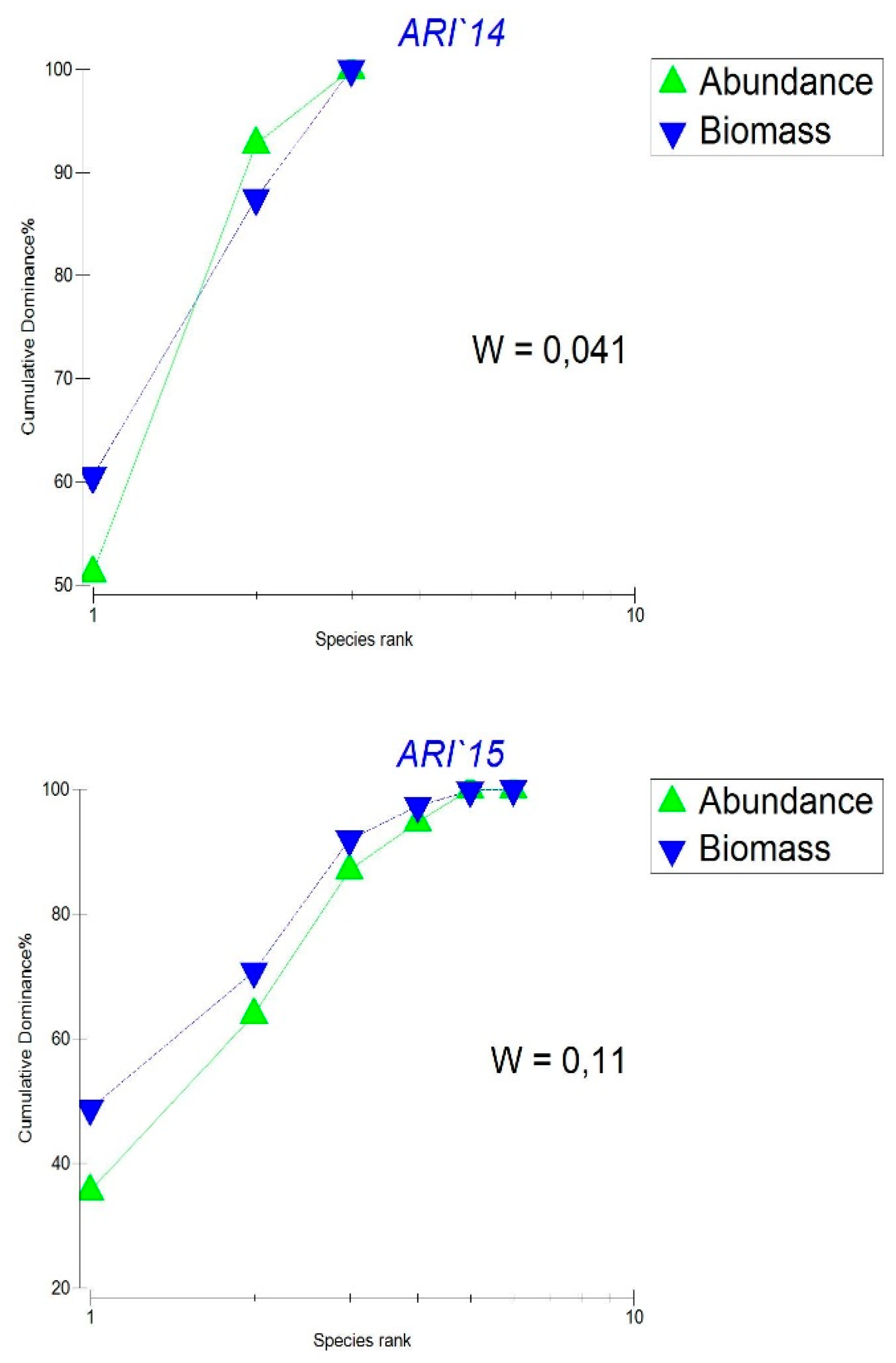

The K-dominant abundance and biomass curves in Lake Ariana (

Figure 4) as an indicator of the presence of stress in the system and/or poor ecological conditions in this case reflect a small number of taxa and their high abundance. The rapidity of the curve does not reach 100 indicates a low evenness of the distribution of taxa and a low degree of species richness. The Warwick coefficient (W) is also very low which is an indicator of stress in the message.

Figure 3.

Geometric curves of zooplankton abundance in Lake Ariana 2013 – 2015.

Figure 3.

Geometric curves of zooplankton abundance in Lake Ariana 2013 – 2015.

Figure 4.

K-dominant curves of zooplankton abundance and biomass in Lake Ariana 2013 – 2015 and Warwick coefficient (W).

Figure 4.

K-dominant curves of zooplankton abundance and biomass in Lake Ariana 2013 – 2015 and Warwick coefficient (W).

In 2013 the zooplankton biomass in Ariana Lake was dominated by Daphnia longispina (36%) with Acanthocyclops robustus as a co-dominant species (17%). Nauplii and juvenile cyclopoids accounted for 11% each. Subdominant species included Simocephalus vetulus (9%) Chidorus sphaericus (7%) Alona rectangula (5%) and members of the genus Alonella (3%).

In 2014 Simocephalus vetulus became the dominant species constituting 51% of the plankton biomass followed by Daphnia longispina (29%) and Acanthocyclops robustus (12%). Chidorus sphaericus was the only subdominant species (5%).

In 2015 Acanthocyclops robustus dominated the biomass (44%) along with juvenile cyclopoids (14%). Subdominant species included Scapholeberis kingi (8%) Thermocyclops dybowskii and Daphnia longispina (7% each) Eubosmina lamellata (6%) juvenile representatives of the genus Daphnia (5%) Chidorus sphaericus (3%) and Ceriodaphnia reticulata Simocephalus vetulus and Alona rectangula (2% each).

Overall both taxonomic abundance and biomass distribution appear relatively balanced. However the uneven distribution of dominant taxa in terms of abundance compared to biomass is the primary factor contributing to the low values of the Warwick index.

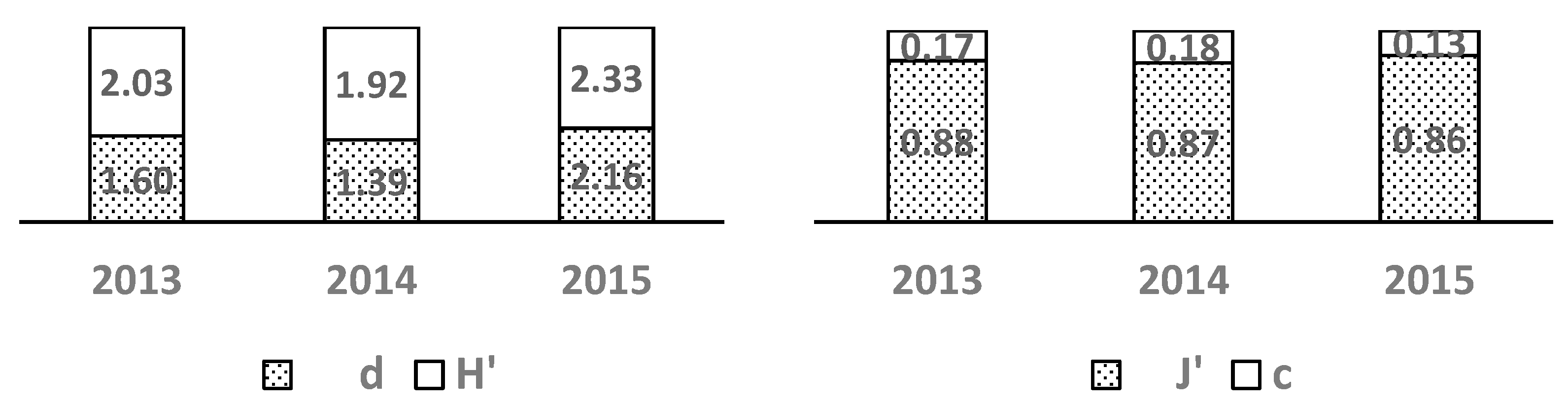

Over the three years of study the

Shannon & Weaver diversity index (H) exhibited high values (

Figure 5) which can be attributed to low population densities and high evenness. This pattern is further supported by the

Pielou evenness index (J) which also displayed high values.

The

Margalef species richness index (d) (

Figure 5) which accounts for the relationship between species number and the number of individuals per species confirmed the low overall species richness with a relatively even distribution of individuals among species. Consequently this led to low dominance values as indicated by the

Simpson dominance index (c).

In 2015 the values of H and d were slightly higher likely due to the greater number of samples collected that year. Overall the indices suggest favorable conditions for the development of the zooplankton community.

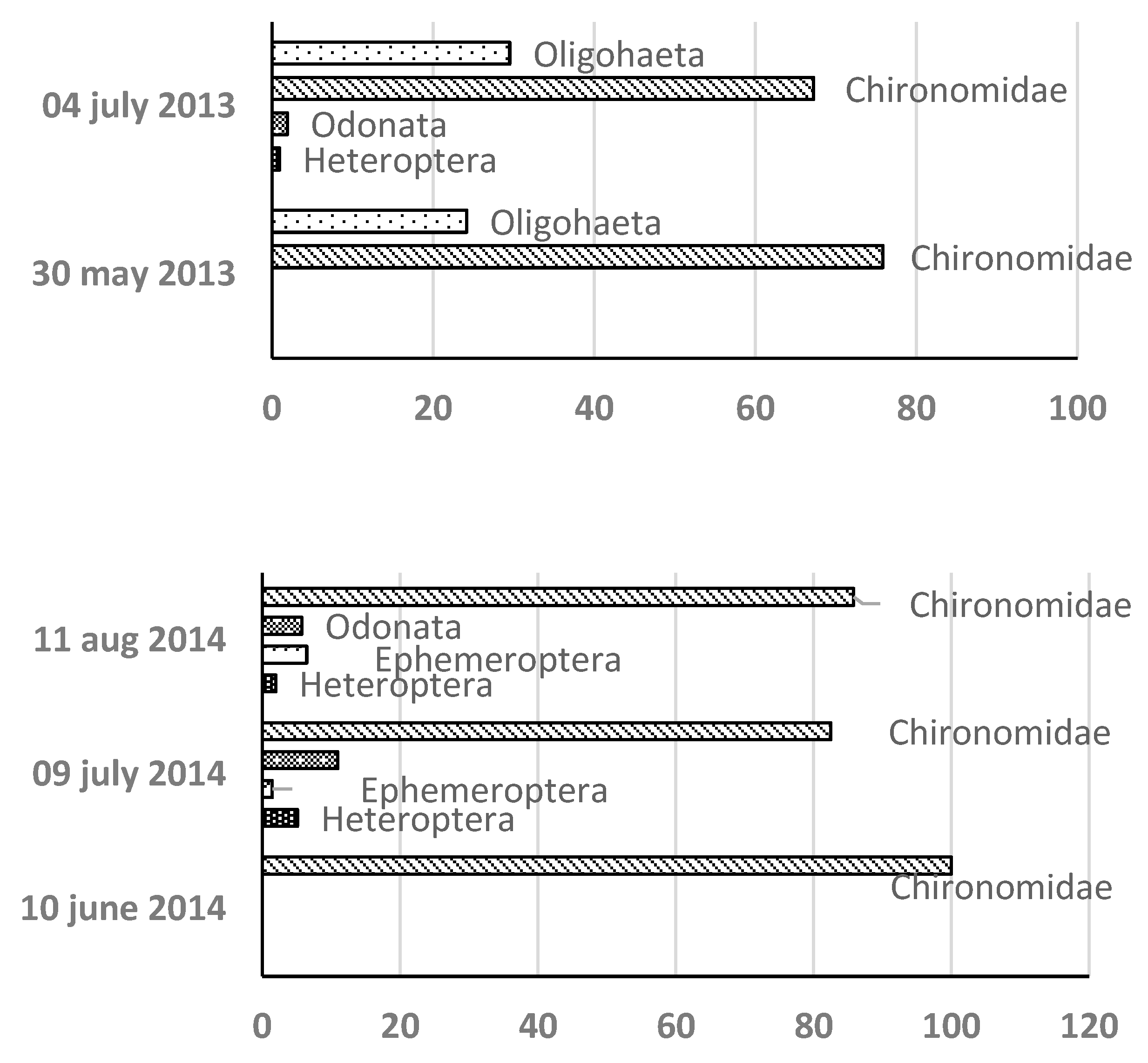

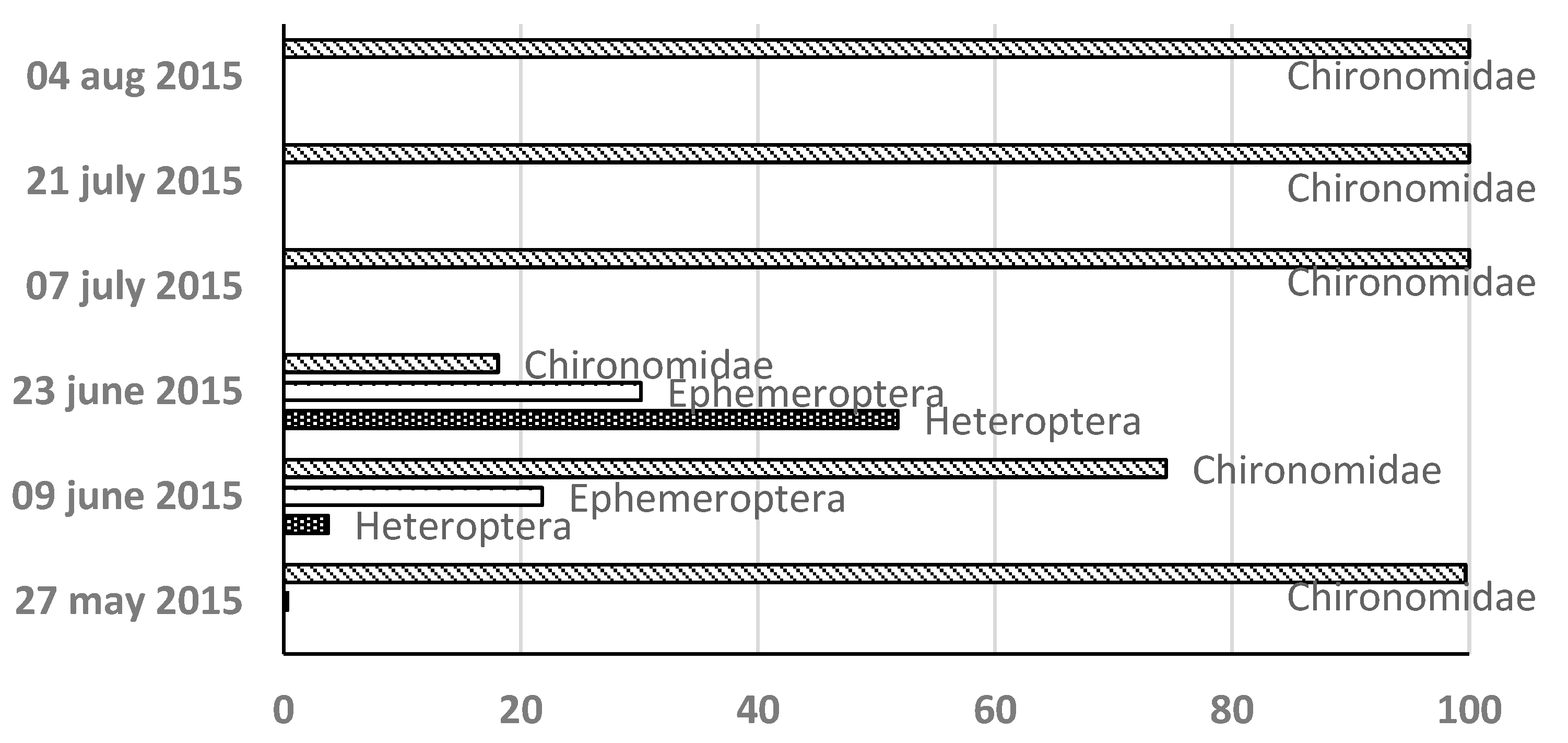

Macrozoobenthos Community Structure Over three years 23 MZB taxa were identified: 13 in 2013 11 in 2014 and 14 in 2015. Chironomidae were consistently dominant (

Figure 6.).

Figure 6.

Sequence of settlement and relative share of the abundance of individual taxa of the MZB community in Lake Ariana in 2013-2015.

Figure 6.

Sequence of settlement and relative share of the abundance of individual taxa of the MZB community in Lake Ariana in 2013-2015.

In 2013 chironomids constituted 76% of MZB retaining dominance throughout. Two species from the subclass Oligochaeta complete the composition of the community - Nais communis and Nais pardalis. In 2014 chironomids initially comprised 100% of MZB with Hemiptera Ephemeroptera and Odonata appearing later but remaining scarce. In 2015 chironomids again dominated initially with Hemiptera and Ephemeroptera briefly increasing to 52% and 30% respectively before chironomids reasserted dominance. Chironomids are represented by the species Cricotopus sylvestris Chironomus riparius Tanytarsus gregarius and Cryptochironomus defectus. From the orders Ephemeropetra - Cloeon dipterum from Odonata – family Libellulidae from Hemiptera – family Corixidae.

Here as in the zooplankton community the values of the Shannon and Margalef indices (

Figure 7) reflect the low number of individuals and the few species with even abundance. Accordingly a relatively high evenness according to the Pielou index (J) and a low value of the Simpson dominance index (c).

The zooplankton community in Lake Ariana exhibited four functional trophic groups across all three study years: omnivores (Omni) phytoplanktonophages (PHph) detritophages (DF) and predators (PR) (

Figure 8).

In 2013 and 2015 omnivores dominated throughout the study period whereas phytoplanktonophages had a more modest presence peaking at 27% in 2015. In contrast 2014 saw a dominance of phytoplanktonophages which constituted nearly 90% of the community. Detritophages emerged in the middle of the hydroperiod (HP) accounting for an 8% share. Predators maintained a relatively stable presence of approximately 9–11% across all three years.

Each year macrozoobenthic settlement in Lake Ariana begins anew due to the complete absence of deposited organic matter. All benthic organisms originate from external colonization with community structure determined by the lake’s environmental state. Three functional trophic groups were identified: scrapers (SC) deposit feeders (DF) and predators (PR) (

Figure 9).

Detritophages were consistently the dominant trophic group throughout the study period. Scrapers exhibited a comparatively significant presence only in 2013 comprising nearly 24% of the macrozoobenthic community. Predators remained underrepresented reaching a maximum of 8.5% in 2015.

Loop analysis revealed that the Hurwitz coefficient for the zooplankton community was positive (a>0) indicating a stable system. Conversely the benthic community was characterized by a negative coefficient (a<0) signifying instability. These results suggest that the ecosystem primarily functions within the pelagic zone with plankton playing a leading role in overall ecosystem productivity.

4. Conclusions

In natural temporary lakes the structure of biological communities is primarily influenced by the duration of the hydroperiod [Boix et al.; Menge and Sutherland]. Additionally the concentration of dissolved substances and the physicochemical parameters of the water tend to be more stable in lakes with longer hydroperiods [[21]. However in lakes with a controlled hydrological regime the concentrations of dissolved substances and the physicochemical parameters exhibit low variability and the hydroperiod does not influence these dynamics.

In temporary water bodies predation pressure and environmental conditions—determined by hydroperiod duration—are considered the dominant forces shaping zooplankton communities. These two factors exert the strongest influence at both ends of the hydroperiod gradient [

9,

10]. When examining primary succession in a temporary lake with a controlled hydrological regime the hydroperiod does not play a role in structuring the zooplankton community. The absence of predation pressure and the relatively stable environmental parameters maintained by the continuous water flow create favorable conditions for zooplankton development. As a result a viable community establishes itself playing a key role in the ecosystem’s productivity. This community is primarily composed of cyclopoid copepods and cladocerans which are species characterized by wide distribution short life cycles and omnivorous feeding habits.

The macrozoobenthic community fails to establish a stable population due to the absence of bottom sediments and organic deposits. As a result its development is limited to the lake’s shoreline where leaf litter accumulates. Chironomids are the primary colonizers of the benthic zone. Other insect families which typically constitute a significant component of benthic communities fail to establish viable populations and are represented by only a few isolated individuals. The lack of a suitable substrate and the short duration of the lake’s existence prevent the development of a fully functional macrozoobenthic community making it entirely dependent on colonization from surrounding areas.

The timing of lake filling is an important factor in community formation. In temporary lakes particularly those with shorter hydroperiods the first weeks or months after filling are crucial for species richness [Antón-Pardo María]. Since colonization occurs under different climatic conditions each year the resulting zooplankton community structure varies accordingly. In 2014 Ariana Lake was filled in mid-June unlike other years when filling occurred at the end of May. Higher temperatures lower oxygen concentrations and elevated pH levels (approximately 8.5) in June significantly influenced the development of copepods and cladocerans [

22]. This shift in conditions allowed rotifers to assume a dominant role in the zooplankton community [

23]. Thus in lakes with a controlled hydrological regime the timing of filling becomes a key factor in determining zooplankton community composition [

24].

Regardless of the specific community structure these assemblages remain species-poor with high evenness and low dominance. However the zooplankton community successfully establishes a viable population playing a significant role in the ecosystem’s energy flow. In contrast the macrozoobenthic community is strongly influenced by the presence of bottom sediments. In natural temporary lakes lake age is an essential factor shaping macrozoobenthic communities [

8]. In the case of Ariana Lake which is effectively reset to year zero annually the age of the lake plays a more significant role in determining macrozoobenthic community structure than hydrological stability or predation pressure.

Biotic factors such as competition and predation have less impact on the development of zooplankton and macrozoobenthic communities in temporary water bodies [

11]. These findings enhance our understanding of temporary lake ecology [

5] and contribute to informed decision-making for biodiversity conservation in such ecosystems.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no actual potential or perceived conflict of interest for this article.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

List of taxa plankton found in Lake Ariana during the years studied.

Table A1.

List of taxa plankton found in Lake Ariana during the years studied.

| 2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

| Cyclopoidae sp. juv. |

Acanthocyclops robustus |

Cyclopoidae sp. |

| Acanthocyclops robustus |

Arctodiaptomus pectinicornis |

Cyclopoidae sp. juv. |

| Calanoida sp. juv. |

Daphnia gr. longispina |

Acanthocyclops robustus |

| Daphnia gr. longispina |

Moina rectirostris |

Thermocyclops dybowskii |

| Simocephalus vetulus |

Simocephalus vetulus |

Metacyclops gracilis |

| Chydorus sphaericus |

Graptoleberis testudinaria |

Daphnia sp. juv. |

| Alona rectangula |

Chydorus sphaericus |

Daphnia gr. longispina |

| Alonella sp. |

Euchlanis sp. |

Ceriodaphnia reticulata |

| Lecane sp. |

Trichotria sp. |

Simocephalus vetulus |

| Brachionus sp. |

|

Graptoleberis testudinaria |

| nauplius |

|

Scapholeberis kingi |

| |

|

Euricercus lamelatus |

| |

|

Chydorus sphaericus |

| |

|

Alona rectangula |

| |

|

Pleuroxus aduncus |

| |

|

Platyias quadricornis |

| |

|

nauplius |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

List of taxa benthos found in Lake Ariana during the years studied.

Table A2.

List of taxa benthos found in Lake Ariana during the years studied.

| 2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

| Sigara sp. |

Sigara sp. |

Corixidae g. sp. |

| Sigara lateralis |

Sigara lateralis |

Sigara lateralis |

| Cloeon dipterum |

Sigara semistriata |

Plea minutissima |

| Libellulidae |

Cloeon dipterum |

Cloeon dipterum |

| Cricotopus sylvestris |

Libellulidae |

Planorbidae sp. |

| Chironomus gr. riparius |

Planorbidae sp. |

Cricotopus sylvestris |

| Tanytarsus gregarius |

Cricotopus sylvestris |

Chironomus gr. riparius |

| Cryptochiron. gr. defectus |

Chironomus gr. riparius |

Tanytarsus gregarius |

| Cricotopus sp. |

Cryptochiron. gr. defectus |

Cryptochiron. gr. defectus |

| Tanytarsus sp. |

Diptera sp. |

Chironomus sp. |

| Chaoborus sp. |

Hydracarina sp. |

Cricotopus sp. |

| Nais communis |

|

Tanytarsus sp. |

| Nais pardalis |

|

Criptochironomus sp. |

| |

|

Tvetenia sp. |

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

MZB Macrozoobenthos

References

- Díaz J. Settele E. Brondízio H.T. Ngo M. Guèze J. Agard Trinidad A. Arneth P. Balvanera K. Brauman S. Butchart K. Chan L. Garibaldi K. Ichii J. Liu S.M. Subramanian G. Midgley P. Miloslavich Z. Molnar D. Obura A. Pfaff S. Polasky A. Purvis J. Razzaque B. Reyers R.R. Chowdhury Y. J. Shin I. 162 VIsseren-Hamakers K. Willis C. Zayas. (2019). Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-policy. Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 2015 Bonn Germany.Pérez-Bilbao A. et al In: Biodiversity in Ecosystems-Linking Structure and Function (ed. Yueh-Hsin Lo) London: IntechOpen 642 p.

- Jeffries M.J. Modeling the incidence of temporary pond microcrustacea: The importance of dry phase and linkage between ponds. Israel Journal of Zoology 2001 47: 445–58.

- Oertli B. J. Biggs R. Ce ́re ́ghino & P. Grillas. Conservation and monitoring of pond biodiversity: introduction.Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems15: 535–540. (PDF) A comparison of Cladocera and Copepoda as indicators of hydroperiod length in Mediterranean ponds. 2005 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297161514_.

- Ce ́re ́ghino R. J. Biggs B. Oertli & S. Declerck. The ecology of European ponds: defining the characteristics of a neglected freshwater habitat. 2008 Hydrobiologia 597: 1–6. (PDF) A comparison of Cladocera and Copepoda as indicators of hydroperiod length in Mediterranean ponds.

- Qingji Zhang Yongjiu Cai Qiqi Yuan Jianghua Yang Rui Dong Zhijun Gong Thibault Datry Boqiang Qin Hydrological conditions determine the assembly processes of zooplankton in the largest Yangtze River-connected Lake in China 2024 Journal of Hydrology Volume 645 Part B 132252 ISSN 0022-1694. [CrossRef]

- 6. Yunliang Li Qi Zhang Xinggen Liu Jing Yao Water balance and flashiness for a large floodplain system: A case study of Poyang Lake China 2020 Science of The Total Environment Volume 710 135499 ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Seminara Marco & Vagaggini Daria & Stoch Fabio. A comparison of Cladocera and Copepoda as indicators of hydroperiod length in Mediterranean ponds. 2016. Hydrobiologia. 782. [CrossRef]

- Antón-Pardo María & Armengol X. & Ortells Raquel. Zooplankton biodiversity and community structure vary along spatiotemporal environmental gradients in restored peridunal ponds. 2015 Journal of limnology. 75. [CrossRef]

- Dallas Tad & Kramer Andrew & Zokan Marcus & Drake John. Ordination obscures the influence of environment on plankton metacommunity structure: Ordination obscures the influence of environment. 2016 Limnology and Oceanography Letters. 1. [CrossRef]

- Zokan Marcus & Drake John. The effect of hydroperiod and predation on the diversity of temporary pond zooplankton communities. 2015 Ecology and Evolution. 5. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov P. Pehlivanov L. Structure of zoocenoses in the ephemeral pond Lilov vir Western Bulgaria. 2024 Proceedings of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Vol. 77 No 2.

- Kutikova L.A. Starobogatov Ya.I. Keys to the Freshwater Invertebrates of the European part of USSR: Plankton and Benthos 1977 Gidrometeoizdat 318 (rus).

- Bledzki L.A. J. I. Rybak Freshwater Crustacean Zooplankton of Europe: Cladocera & Copepoda 2016 Springer 918.

- Wariwick R.M. A new method for detecting pollution effects on marine macrobenthic communities. 1986 Marine Biology 92 557-562.

- Gray J. S. Pearson T. H. Objective selection of sensitive species indicative of pollution-induced change in benthic communities. 1. Comparative methodology. 1982 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 9 111-119.

- Maier G. The Seasonal Dynamics of Thermocyclops dybowskii (Lande 1890) in a Small Pond (Copepoda Cyclopoida) 1990 Gerhard https://www.jstor.org/stable/20104571 Crustaceana Vol. 59 No. 1 (Jul. 1990) pp. 76-81 Published By: Brill.

- Walseng B. Acanthocyclops robustus has a scattered distribution and is found in all parts of the country. It occurs in waters of varying sizes being most common in small ponds. It is known as an early colonizator. 2016 Publisher Norsk institutt for naturforskning 2016a CC BY 4.0 https://www.biodiversity.no/Pages/220942/.

- Walseng B. Daphnia longispina is our most common daphniid and is distributed all over the country from sea level to the high mountains. It is found both in large clearwater lakes as well as in small nutrient rich ponds. The species is characterized by its large compound eye and long spine. 2016 Publisher Norsk institutt for naturforskning 2016b CC BY 4.0 https://www.biodiversity.no/Pages/220942/213719/.

- Walseng B. Scapholeberis mucronata O.F.M. 2016 Publisher Norsk institutt for naturforskning 2016c CC BY 4.0 https://biodiversity.no/Pages/214463/.

- Walseng B. Simocephalus vetulus O.FM. 2016 Publisher Norsk institutt for naturforskning 2016d CC BY 4.0 https://biodiversity.no/Pages/214460/.

- Magnusson A. & Williams K. The roles of natural temporal and spatial variation versus biotic influences in shaping the physicochemical environment of intermittent ponds: a case study. 2006 Archiv für Hydrobiologie Volume 165 Number 4 (2006) p. 537 - 556. [CrossRef]

- Whitman RL Nevers MB Goodrich ML Murphy PC Davis BM. Characterization of Lake Michigan coastal lakes using zooplankton assemblages. 2004 Ecol Indic 4:277-286.

- Sellami I Hamza A Bour ME Mhamdi MA Pinelalloul B Ayadi H. Succession of Phytoplankton and Zooplankton Communities Coupled to Environmental Factors in the Oligo-mesotrophic Nabhana Reservoir (Semi Arid Mediterranean Area Central Tunisia). Zool Stud. 2016 Aug 8;55:e30. PMID: 31966175; PMCID: PMC6511907. [CrossRef]

- Florencio Margarita & Fernández-Zamudio Rocío & Lozano Mayca & Díaz-Paniagua Carmen. Interannual variation in filling season affects zooplankton diversity in Mediterranean temporary ponds. 2020 Hydrobiologia. 847. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).