Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

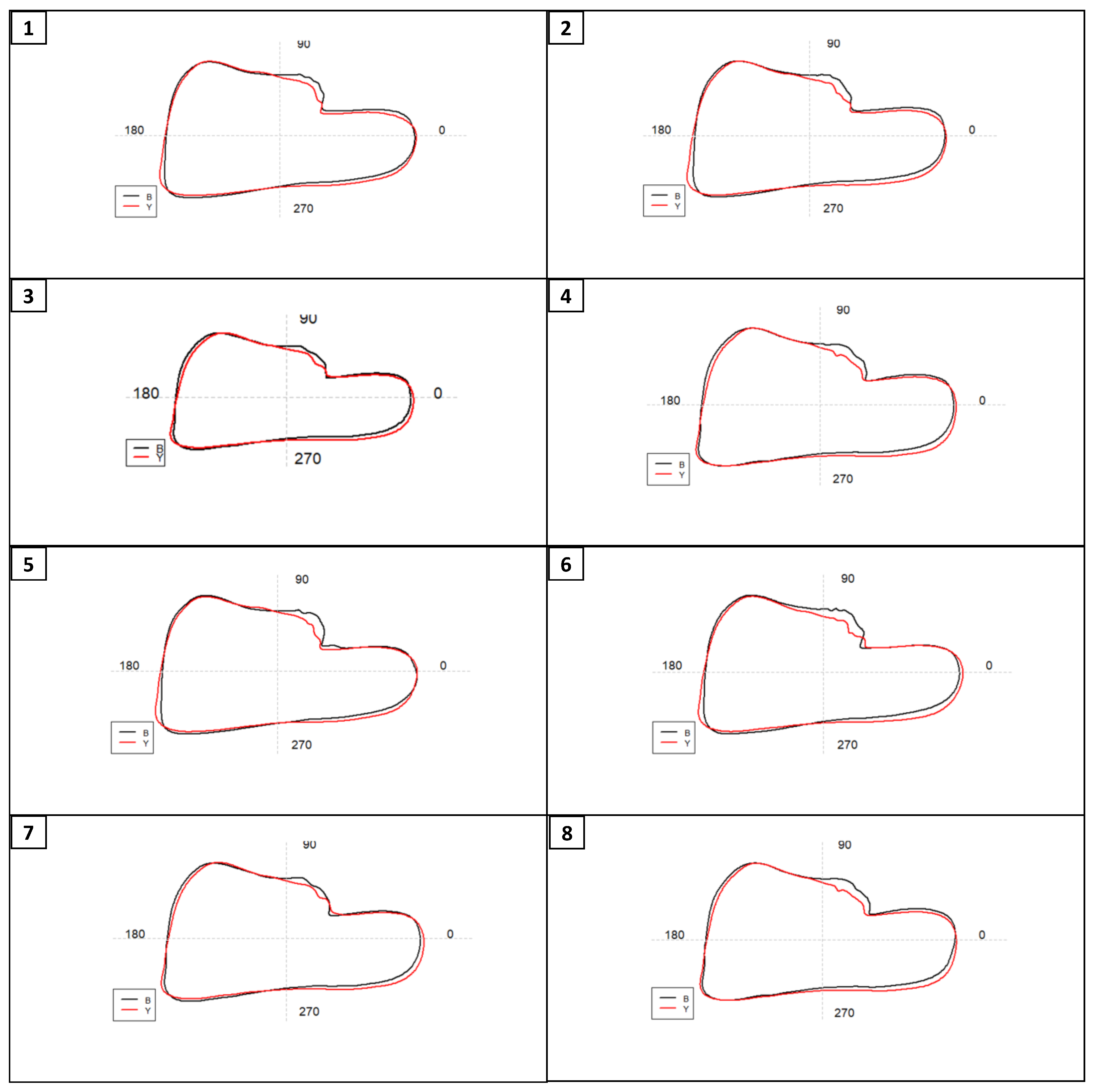

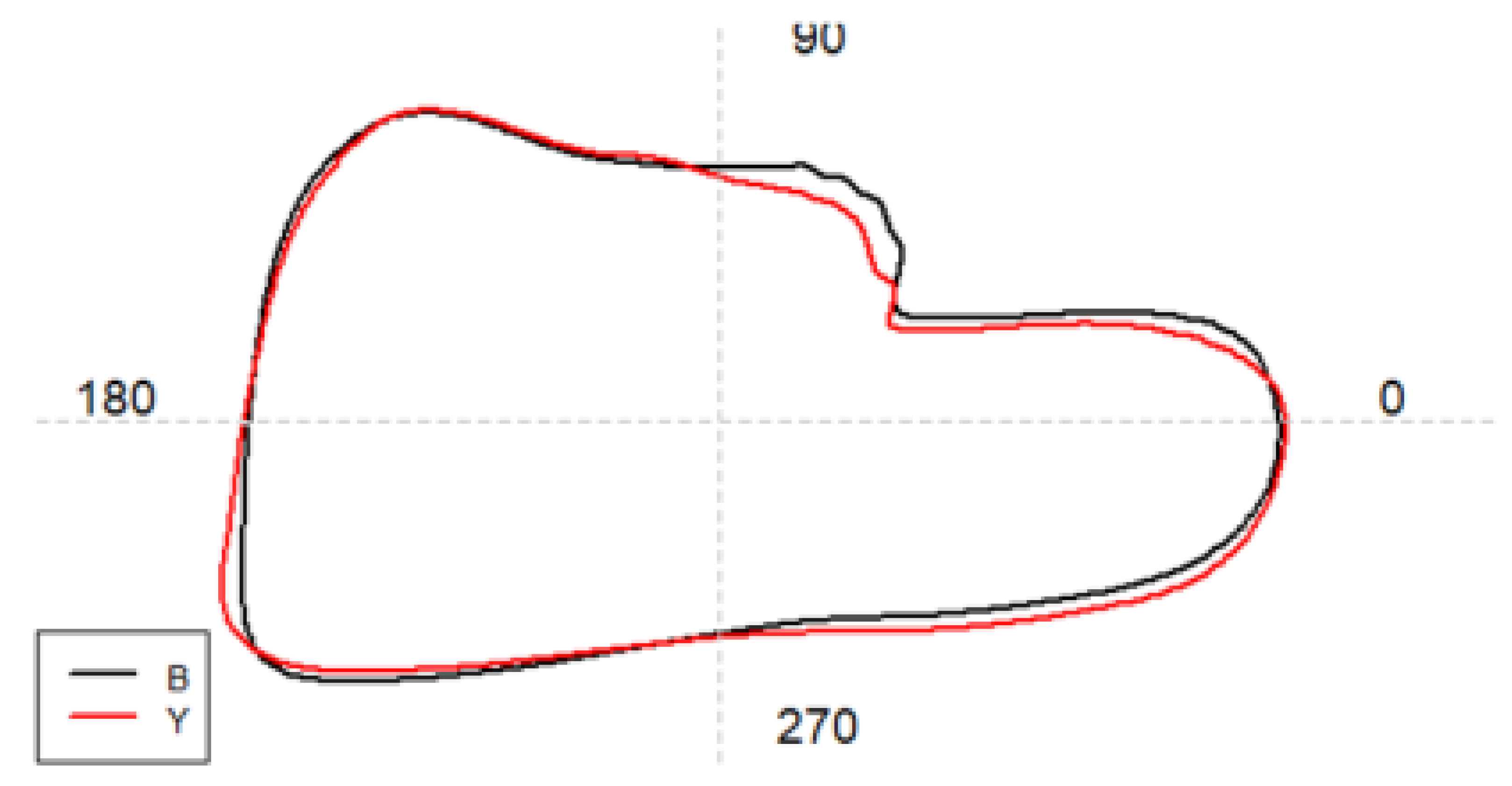

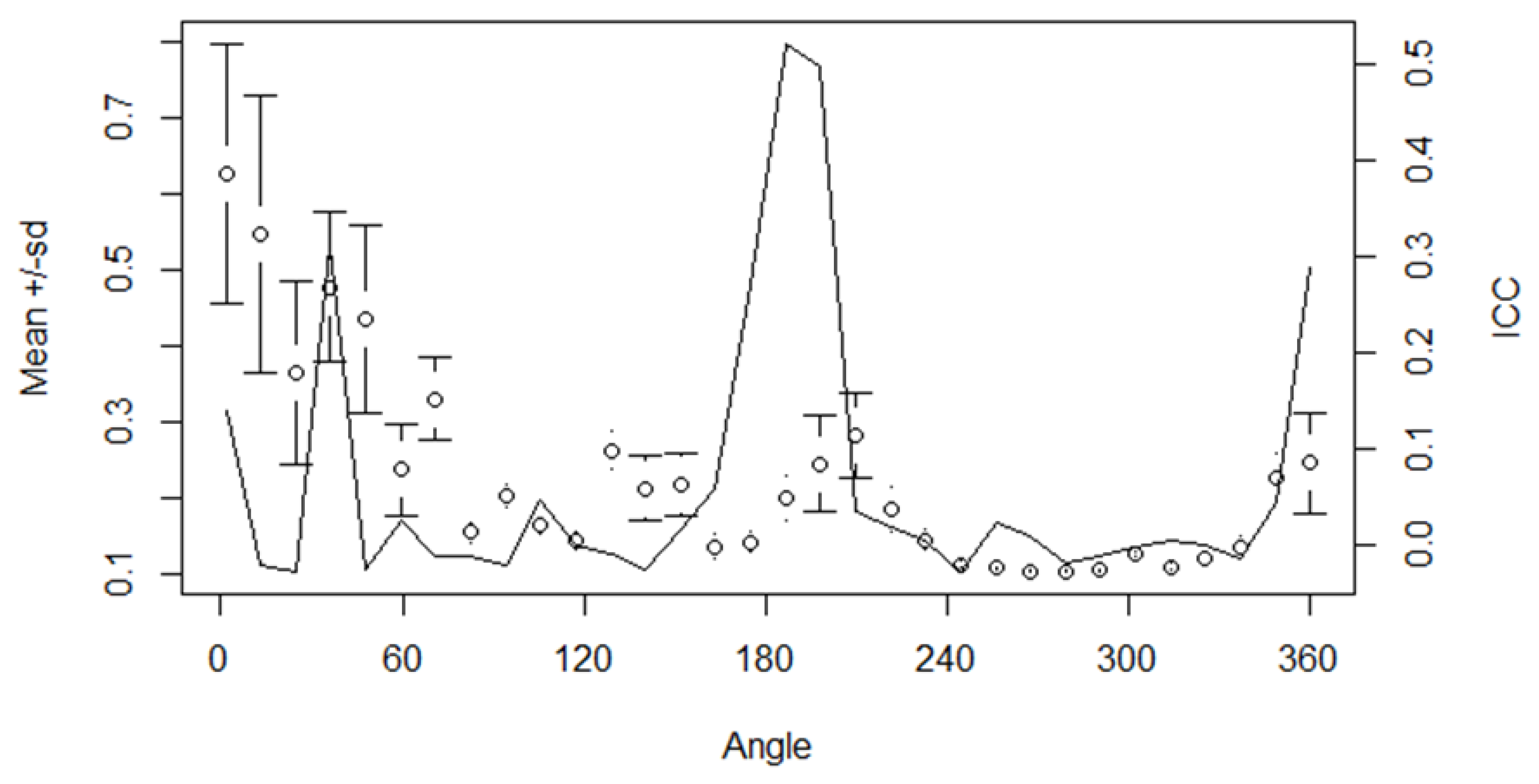

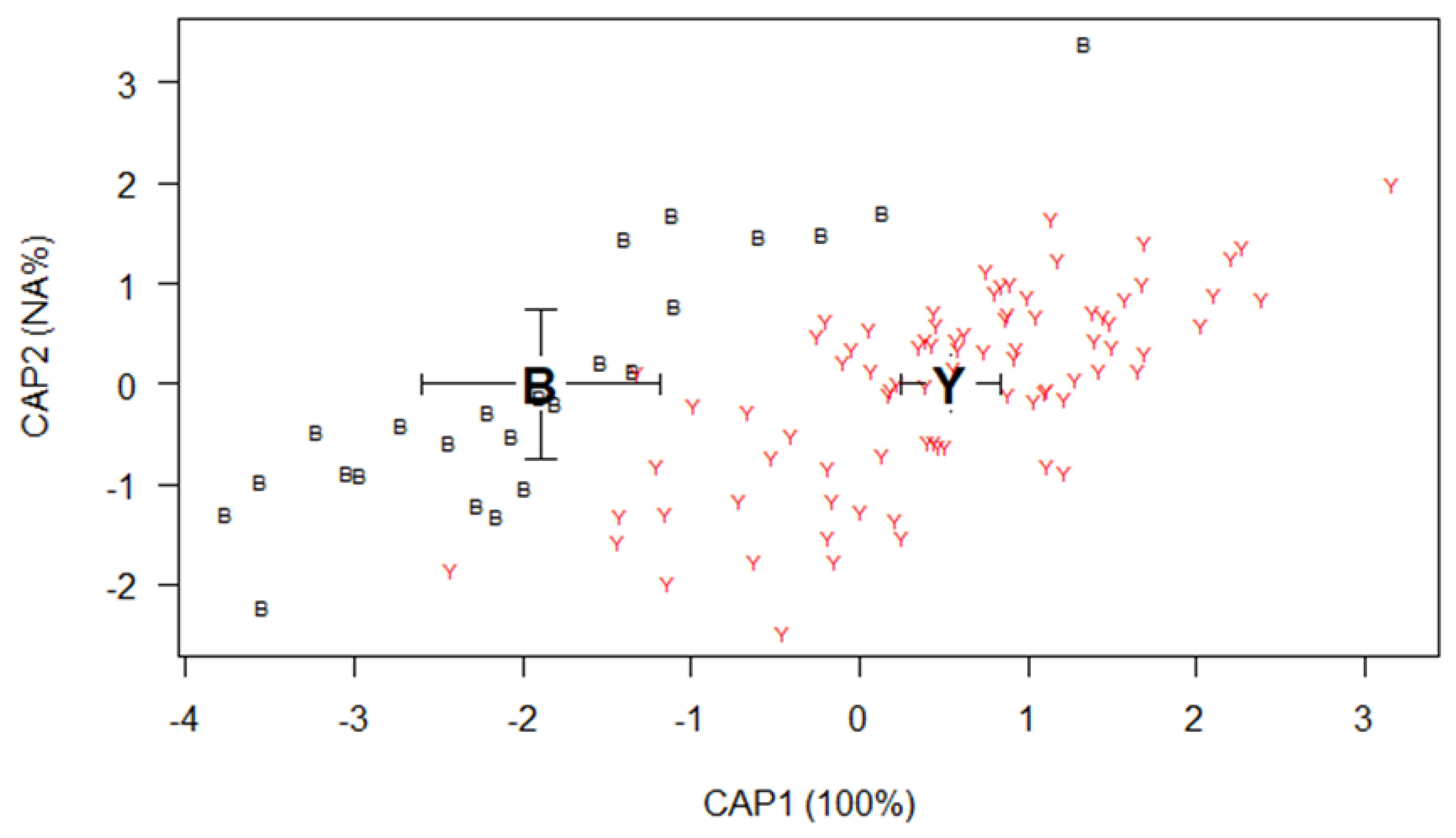

Context. Fish identification is one of the important aspects in fisheries management. This process is occasionally challenging for small/juvenile bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) and yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) due to their similar characteristics in size and external appearance. One method to identify fish quickly and cheaply is by otolith shape analysis. Aims. This study aims to identify small bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna using otolith shape analysis. Methods. A total of 115 bigeye tuna otoliths and 186 yellowfin tuna otoliths were collected from several fishing ports in Indonesia. Statistical analysis of the otolith shape using multivariate analysis in eight classifications based on locations and length class. Key results. There is a significant difference between the shape of otolith bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna in all eight classifications (p<0.05). The difference in the otolith shape of this otolith is detected in the rostrum and antirostrum. This difference be present in all locations, particular locations, and in several length classes. Conclusion. Otolith shape analysis can be used for distinguishing between bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna. Implications. The results of this study indicate that otolith shape analysis had potential to use as a method to identify small bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

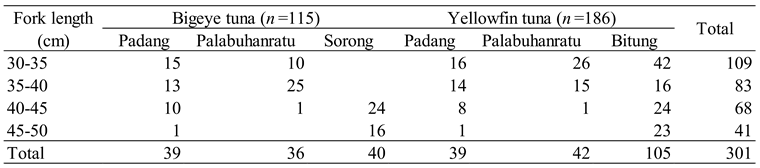

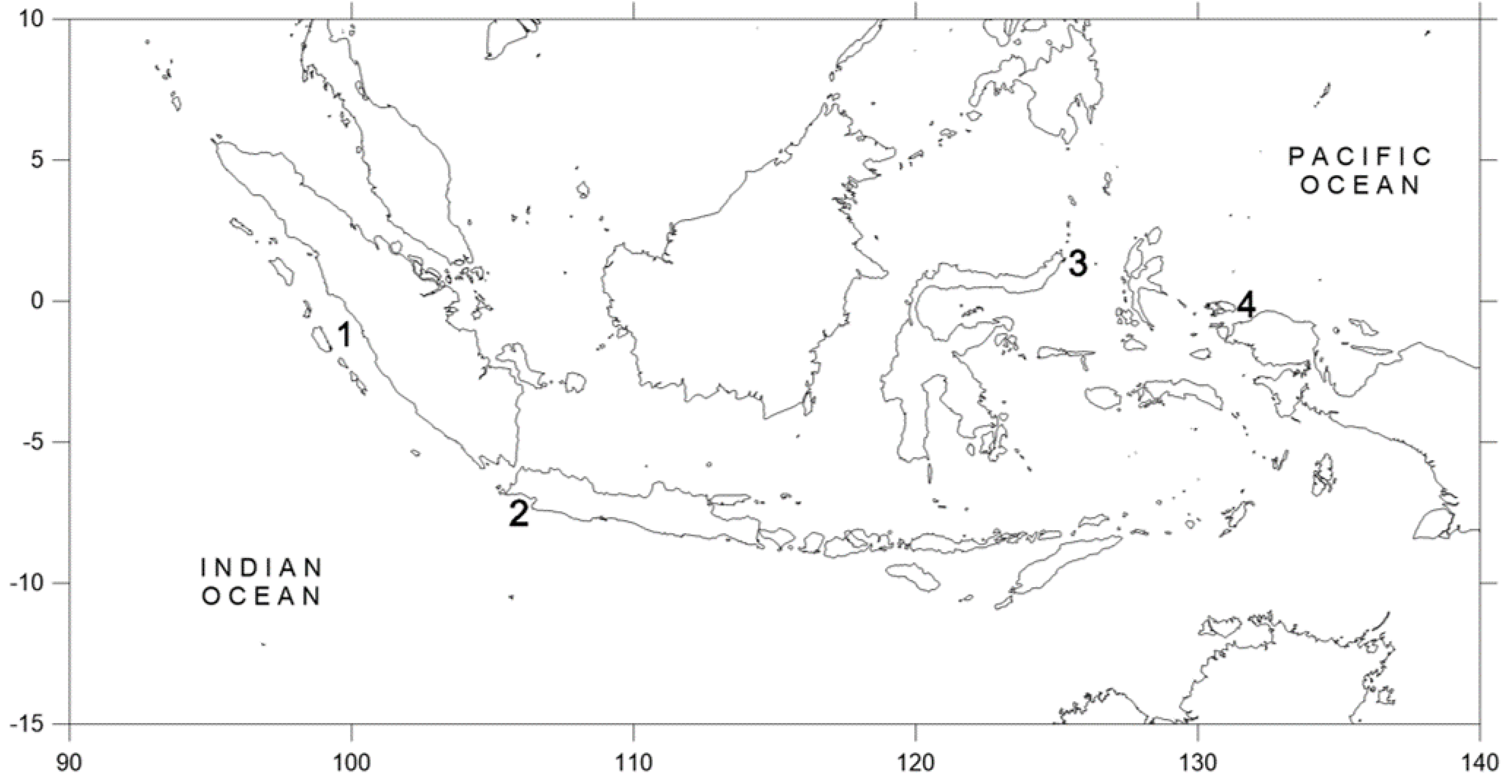

Data collection

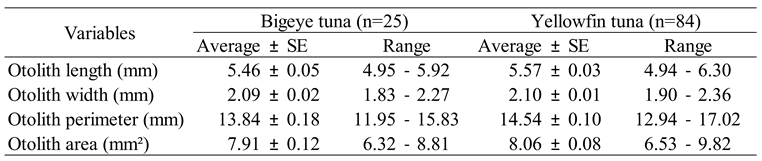

Otolith shape analysis

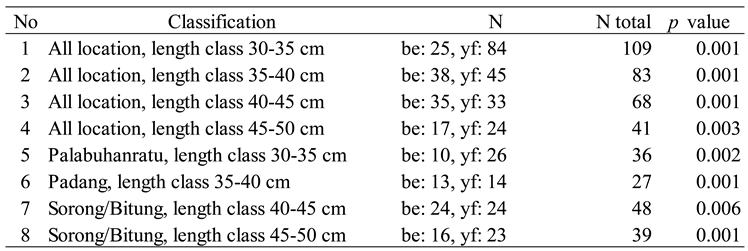

Statistical analysis

Results

|

|

|

Discussion

Shape analysis

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IOTC. Report of the 22nd Session of the IOTC Working Party on Tropical Tunas, Stock Assessment Meeting; Indian Ocean Tuna Commission: Mahe, Seychelles, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alimina, N.; Wiryawan, B.; Monintja, D.R.O.; Nurani, T.W.; Taurusman, A.A. Comparing different small-scale tuna fishery suppliers: a case study on trolling line and pole and line in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation 2015, 8, 500–506. [Google Scholar]

- Wiranthi, P.E.; Aminudin, I.; Dewi, E.R. A Gravity Model for Indonesian Canned Tuna Exports to The European Union Market: An Application of PPML Estimator. SRIWIJAYA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF DYNAMIC ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS 2019, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleonart, J.; Taconet, M.; Lamboeuf, M. Integrating information on marine species identification for fishery purposes. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2006, 316, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillett, B.J.; Field, I.C.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Johnson, G.; Buckworth, R.C.; Meekan, M.G.; Ovenden, J.R. Accuracy of species identification by fisheries observers in a north Australian shark fishery. Fisheries Research 2012, 127, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vazquez, E.; Machado-Schiaffino, G.; Campo, D.; Juanes, F. Species misidentification in mixed hake fisheries may lead to overexploitation and population bottlenecks. Fisheries Research 2012, 114, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiryanti, J.; Glynn, G.F.; Limpus, L.G. Improved quality control for the handling and processing of fresh and frozen tuna at sea and on shore; Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Centre (SEAFDEC): Singapore, 1997; p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Fukofuka, S.; Itano, D.G. Handbook for the Identification of Yellowfin and Bigeye Tunas in Fresh, but Less Than Ideal Condition (v6); Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission: Noumea, New Caledonia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Afanasyev, P.K.; Orlov, A.M.; Rolsky, A.Y. Otolith Shape Analysis as a Tool for Species Identification and Studying the Population Structure of Different Fish Species. Biology Bulletin 2017, 44, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănaru, D.; Morat, F.; Creteanu, M. Otolith shape analysis of three gobiid species of the Northwestern Black Sea and characterization of local populations of Neogobius melanostomus. Cybium : Revue Internationale d’Ichtyologie 2017, 41, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Al-Abdulkader, K. Identification of fish families and species from the western Arabian Gulf by otolith shape analysis and factors affecting the identification process. Marine and Freshwater Research 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.; Lester, R.; Clear, N.; Grewe, P.; Moore, B.; Eveson, J.; Lestari, P.; Wujdi, A.; Taufik, M. ; Wudianto; et al. Population structure of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and bigeye tuna (T. obesus) in the Indonesian region; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IOTC. IOTC Online Data Querying Service. Indian Ocean Tuna Commission: 2020.

- Duggan, D.E.; Kochen, M. Small in scale but big in potential: Opportunities and challenges for fisheries certification of Indonesian small-scale tuna fisheries. Marine Policy 2016, 67, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, M.E.; Bailey, M. A tale of two standards: A case study of the Fair Trade USA certified Maluku handline yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) fishery. Marine Policy 2019, 100, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, E. GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF STRADDLING AND HIGHLY MIGRATORY FISH STOCKS - THE NONSUSTAINABLE NATURE OF HIGH SEAS FISHERIES. Ocean Development and International Law 1994, 25, 255–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reygondeau, G.; Maury, O.; Beaugrand, G.; Fromentin, J.M.; Fonteneau, A.; Cury, P. Biogeography of tuna and billfish communities. Journal of Biogeography 2012, 39, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, K.A.; Hampton, J.; Miyabe, N. Application of a habitat-based model to estimate effective longline fishing effort and relative abundance of Pacific bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus). Fisheries Oceanography 2002, 11, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagorn, L.; Bach, P.; Josse, E. Movement patterns of large bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) in the open ocean, determined using ultrasonic telemetry. Marine Biology 2000, 136, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, J.; Krusic-Golub, K.; Eveson, P.; Clear, N.; Roupsard, F.; Sanchez, C.; Nicol, S.; Hampton, J. Age and growth of yellowfin and bigeye tuna in the western and central Pacific Ocean from otoliths. Age 2020, 11, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, J.; Williams, P. A description of tag-recapture data for bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) in the western and central Pacific Ocean. Inter. Comm. Conser. Atlan. Tunas, Coll. Vol. Sci. Pap 2005, 57, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Da Fontoura Costa, L.; Cesar Jr, R.M. Shape Analysis and Classification. 2010, 10. 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Liao, T.; Liu, D.; Luo, Q.; Xu, R.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Feng, F.; Zhang, C. Amygdala Changes in Chronic Insomnia and Their Association with Sleep and Anxiety Symptoms: Insight from Shape Analysis. Neural Plasticity 2019, 2019, 8549237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheas, A.C.; Neil, I.F.; Lack, S.A.; Wikle, C.K. Cell identification and verification of QPF ensembles using shape analysis techniques. Journal of Hydrology 2007, 343, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.; Verma, V.; Zeglinski, J.; Bannigan, P.; Rasmuson, Å. Face indexing and shape analysis of salicylamide crystals grown in different solvents. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 2648–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaraner, M.; Cetinkaya, S. SHAPE ANALYSIS OF MULTI-SCALE BUILDING FEATURES. Proceedings of 7th International Conference on Cartography and GIS, Sozopol, BULGARIA, Jun 18-23; pp. 426–433.

- Koca, A.O.; Moradi, M.G.; Deliklitas, O.; Ucan, A.; Kandemir, I. Discrimination of dwarf honey bee (Apis florea, Fabricius 1876) populations in Iran using elliptic Fourier wing cell shape analysis. Journal of Apicultural Research 2018, 57, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, P.; Ludwig, J. Shape Analysis of Otoliths—a Tool for Indirect Ageing of Eel,Anguilla anguilla (L.)? Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie 1990, 75, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, S.G.; Szedlmayer, S.T. The use of otolith shape analysis for ageing juvenile red snapper, Lutjanus campechanus. Environmental Biology of Fishes 2010, 89, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.J.; Zhang, C.; Panhwar, S.K.; Li, Z.G.; Wan, R. Ageing Belanger's croaker, Johnius belangerii (Cuvier, 1830), based on otolith shape analysis. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2015, 31, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, G.A.; Brown, R.W. Stock identification of haddock Melanogrammus aeglefinus on Georges bank based on otolith shape analysis. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 2000, 129, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenius, M.A.J.; Begg, G.A.; Mapstone, B.D. The use of otolith morphology to indicate the stock structure of common coral trout (Plectropomus leopardus) on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Fishery Bulletin 2006, 104, 498–511. [Google Scholar]

- Leguá, J.; Plaza, G.; Pérez, D.; Arkhipkin, A. Otolith shape analysis as a tool for stock identification of the southern blue whiting, Micromesistius australis. Latin american journal of aquatic research 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stransky, C.; Murta, A.G.; Schlickeisen, J.; Zimmermann, C. Otolith shape analysis as a tool for stock separation of horse mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) in the Northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean. Fisheries Research 2008, 89, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.M.; Gangan, S.S.; Raut, S.; Raghavan, R.; Kumar, A.P.; Singh, L.K.; Jaiswar, A.K. Otoliths as taxonomic tool to identify catfishes of the genus Mystus (Teleostei: Bagridae) from India. Indian Journal of Fisheries 2021, 68, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.; Malara, D.; Romeo, T.; Andaloro, F. Relationships between otolith size and fish size in some mesopelagic and bathypelagic species from the Mediterranean Sea (Strait of Messina, Italy). Scientia Marina 2010, 74, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremm, C.; Schulz, U. Otolith atlas of fish of the Sinos River. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2014, 74, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanci, D.; Polat, N.; Kurucu, G.; Yedier, S.; Kontaş, S.; Darçin, M. Using otolith shape and morphometry to identify four Alburnus species (A. chalcoides, A. escherichii, A. mossulensis and A. tarichi) in Turkish inland waters. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 2015, 31, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, I.; Vieira, A.R.; Gordo, L.S.; Figueiredo, I. Otolith shape analysis as a tool for stock discrimination of the black scabbardfish, Aphanopus carbo Lowe, 1839 (Pisces: Trichiuridae), in Portuguese waters. Scientia Marina 2009, 73, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randon, M.; Le Pape, O.; Ernande, B.; Mahé, K.; Volckaert, F.A.; Petit, E.J.; Lassalle, G.; Le Berre, T.; Réveillac, E. Complementarity and discriminatory power of genotype and otolith shape in describing the fine-scale population structure of an exploited fish, the common sole of the Eastern English Channel. PloS one 2020, 15, e0241429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, S.R.; Lyle, J.M.; Duhamel, G. Application of elliptical Fourier analysis of otolith form as a tool for stock identification. Fisheries Research 2006, 77, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadrin, S.X.; Kerr, L.; Mariani, S. Stock identification methods : applications in fishery science, 2nd edition / edited by Steven Cadrin, Lisa A. Kerr, Stefano Mariani. ed.; Academic Press: 2013.

- de Astarloa, J.M.D.; Bezzi, S.I.; Castro, M.G.; Mabragana, E.; Hernandez, D.; Delpiani, S.M.; Figueroa, D.E.; Cousseau, M.B.; Antoni, M.Y.D.; Tringali, L. Morphological, morphometric, meristic and osteological evidence for two species of hake (Actinopterygii: Gadiformes: Merluccius) in Argentinean waters. Journal of Fish Biology 2011, 78, 1336–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, M.A.; Abiya, J.S.; Milton, J.; Ramesh, K.; Bhat, A.A.; Chelliah, A. Morphometric, meristic and ISSR marker systems for species identification and evolutionary analysis in five Indian Channids. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2014, 55, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quist, M.C.; Bower, M.R.; Hubert, W.A.; Parchman, T.L.; McDonald, D.B. Morphometric and Meristic Differences among Bluehead Suckers, Flannelmouth Suckers, White Suckers, and Their Hybrids: Tools for the Management of Native Species in the Upper Colorado River Basin. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 2009, 29, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amandè, M.J.; Ariz, J.; Chassot, E.; de Molina, A.D.; Gaertner, D.; Murua, H.; Pianet, R.; Ruiz, J.; Chavance, P. Bycatch of the European purse seine tuna fishery in the Atlantic Ocean for the 2003–2007 period. Aquatic Living Resources 2010, 23, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, G.A.; Keenan, C.P.; Sellin, M.J. Genetic variation and stock structure of school mackerel and spotted mackerel in northern Australian waters. Journal of Fish Biology 1998, 53, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojolly, D.; Doyen, P.; Le Fur, B.; Christaki, U.; Verrez-Bagnis, V.; Grard, T. Development of a qPCR Method for the Identification and Quantification of Two Closely Related Tuna Species, Bigeye Tuna (Thunnus obesus) and Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares), in Canned Tuna. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2017, 65, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).