1. Introduction

Modern cosmology rests on the twin pillars of Einstein’s general relativity and the

CDM paradigm. While empirically successful, this framework faces persistent theoretical challenges: the unknown nature of dark energy, tensions in Hubble constant measurements [

2,

3], and the lack of a first-principles mechanism for cosmic acceleration. This work proposes a geometric resolution by unifying spacetime geometry with the boundary conditions of a finite universe.

We model the universe as a compact 3-manifold

isometrically embedded in a static 4D Lorentzian bulk

. Dynamic boundary interactions at

generate intrinsic curvature gradients, quantified by the boundary tensor

, which replaces dark energy in the modified Einstein equations:

Key features of this approach include:

A finite universe topology with radius

R, avoiding singularities through boundary curvature regularization (

Section 3.6),

Radial dependence in the Hubble parameter

, naturally resolving the

tension (

Section 5.1),

Emergent dark energy from extrinsic curvature, , without exotic fields,

Compatibility with energy conditions and Machian inertia (

Section 6).

The theory is observationally indistinguishable from

CDM at intermediate scales but predicts testable signatures: a Hubble gradient

(Eq. (

126)), CMB quadrupole alignment (

Section 5.6), and modified gravitational wave propagation (Eq. (

179)). Numerical solutions (

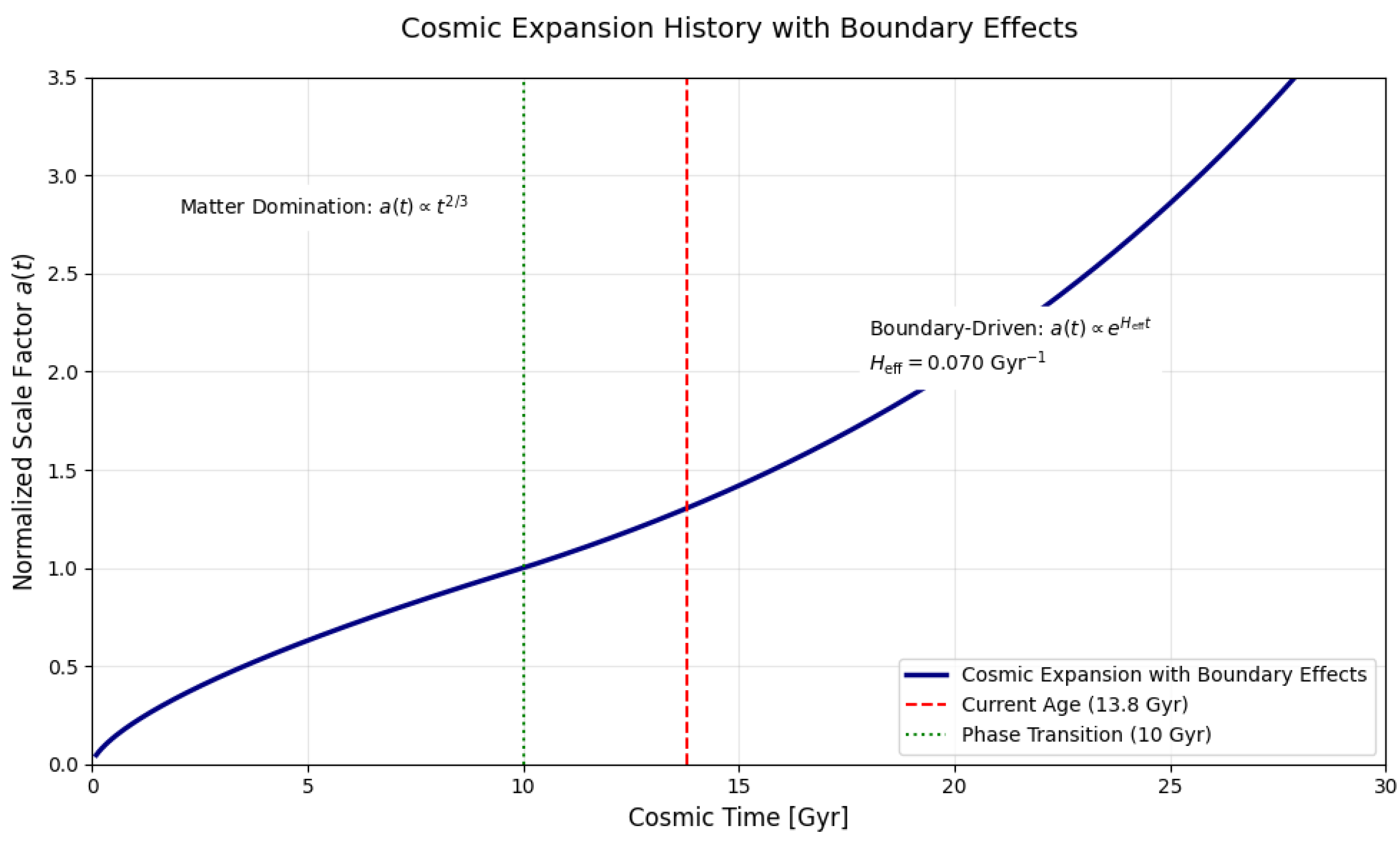

Figure 1) demonstrate consistency with cosmic acceleration and structure formation.

2. Foundational Principles

The theory rests upon three axiomatic principles, rooted in geometric intuition and mathematical consistency, which redefine the universe’s architecture and its interaction with boundaries:

2.1. Principle of Finite Embedding

Manifold Structure: The universe is a compact orientable 3-manifold

isometrically embedded in a 4-dimensional Lorentzian manifold

(the bulk) via:

where

are bulk coordinates and

are intrinsic coordinates.

Induced Metric: The spacetime metric

on

is the pullback of the bulk metric

:

Normal Vector Field: The unit timelike normal vector

satisfies:

Extrinsic Curvature: The second fundamental form

is defined as:

where

is the Lie derivative along

.

2.2. Principle of Boundary Dynamics

Boundary Action Principle: The total action contains boundary terms:

where

is the boundary induced metric.

Israel Junction Conditions: At the boundary

, the discontinuity in extrinsic curvature generates effective stress-energy:

where

is the surface stress-energy tensor.

Boundary Tensor: From variational principle we derive:

modifying Einstein’s equations to:

2.3. Principle of Geometric Unification

Cosmic Acceleration: The boundary tensor generates effective dark energy:

appearing in modified Friedmann equations:

Conservation Laws: Energy-momentum conservation emerges from:

proven via Codazzi identity:

Topological Constraint: The Gauss-Bonnet theorem enforces:

where

is the Euler characteristic.

2.4. Example: 3-Sphere Universe

For a closed universe embedded in 4D Euclidean space:

Extrinsic Curvature Components:

Effective Cosmological Constant:

3. Mathematical Framework

This section provides a rigorous derivation of the modified Einstein equations, boundary tensor, and cosmological solutions, grounded in differential geometry and variational principles.

3.1. Embedding and Induced Geometry

Let the universe be modeled as a 3-dimensional hypersurface smoothly embedded in a 4-dimensional Lorentzian bulk manifold . The embedding is governed by the following mathematical structure:

3.1.1. Bulk Metric and Embedding Functions

Let

have coordinates

(

) and metric

. The embedding of

into

is defined by a set of smooth functions:

where

(

) are coordinates on

.

3.1.2. Induced Metric

The

induced metric on

is obtained by pulling back the bulk metric

:

By the Nash embedding theorem, such an isometric embedding exists globally for smooth

if

is compact.

3.1.3. Normal Vector

The unit normal vector

to

satisfies:

3.1.4. Projection Tensor

The projection tensor

, which maps bulk vectors to

, is:

where

.

3.1.5. Extrinsic Curvature

The extrinsic curvature tensor

quantifies how

bends in

. It is derived from the Lie derivative of

along

:

where

are Christoffel symbols of

. In terms of the bulk covariant derivative

:

3.1.6. Gauss-Codazzi Equations

The intrinsic and extrinsic geometry of are related by:

Gauss equation (4D curvature ↔ 3D curvature + extrinsic terms):

Codazzi equation (conservation of extrinsic curvature):

3.1.7. Topological Constraints

The compactness of implies:

Gauss-Bonnet theorem (relating topology to curvature):

where

is the Euler characteristic.

3.1.8. Example: FLRW Universe Embedded in 4D Minkowski Space

For a flat FLRW metric on

:

embedded in

with

:

Induced metric matches Eq. (

24) by construction.

Extrinsic curvature components:

where

is the spatial metric.

3.2. Extrinsic Curvature Tensor

The extrinsic curvature tensor

quantifies the embedding geometry of

in

. It is defined through:

where

is the Lie derivative along the normal vector

, and

are Christoffel symbols of

. In terms of bulk derivatives:

3.2.1. Gravitational Action with Boundary Terms

The total gravitational action includes boundary contributions:

where

is the induced boundary metric, and

.

3.2.2. Variation of the Action

Varying

S with respect to

:

The Gibbons-Hawking-York term variation cancels boundary divergences:

3.2.3. Modified Einstein Equations

Combining Eqs. (

45) and (

46) gives:

where the

boundary tensor is:

3.2.4. Conservation Laws

The boundary tensor satisfies:

Proof: Using the Codazzi identity

:

3.2.5. Example: FLRW Universe

For the FLRW metric :

3.2.6. Thermodynamic Consistency

The boundary term contributes to black hole entropy:

where

is the boundary area.

3.2.7. Gravitational Wave Implications

The boundary tensor modifies gravitational wave propagation:

introducing scale-dependent damping from boundary curvature.

3.3. Modified Field Equations

3.3.1. Derivation from Variational Principle

3.3.2. Total Action Functional

The complete gravitational action including boundary terms is:

3.3.3. Variation of Geometric Terms

Varying the Einstein-Hilbert term with respect to

:

3.3.4. Boundary Term Variation

The Gibbons-Hawking-York term variation gives:

3.3.5. Matter Action Variation

The matter term variation produces the stress-energy tensor:

3.3.6. Field Equation Derivation

Combining Eqs. (

45), (

46), and (

47):

Imposing natural boundary conditions (

) yields:

where the

boundary tensor is:

3.4. Mathematical Properties

3.4.1. Energy-Momentum Conservation

From the contracted Bianchi identity

, we have:

Using the Codazzi identity

, it follows that:

Thus, the energy-momentum conservation law holds:

ensuring physical consistency with Noether’s theorem.

3.4.2. Conformal Invariance Breaking

Under a conformal rescaling of the metric

, the boundary tensor transforms as:

where

is the d’Alembertian operator.

This shows that the boundary tensor introduces terms breaking conformal invariance, leading to physically observable effects. Such effects could have implications for the behavior of the early universe and deviations from perfect isotropy.

3.4.3. Physical Interpretation

The boundary tensor plays a crucial role in capturing non-local geometric effects at the universe’s boundary. Equation (

54) implies that dynamic boundary interactions introduce a mechanism for effective dark energy without the need for explicit scalar fields.

3.5. Cosmological Application

3.5.1. FLRW Metric Case

For the flat FLRW metric:

where

is the scale factor, and

is a curvature function dependent on the radial coordinate.

3.5.1.1. Extrinsic Curvature Components

The components of the extrinsic curvature are given by:

where

and

R characterize the spatial curvature and boundary scale, respectively.

3.5.2. Modified Friedmann Equations

Substituting these expressions into the modified Einstein field equations from Eq. (

63), we obtain the modified Friedmann equations:

where the effective cosmological term is:

3.5.3. Energy Component Relations

The evolution of different energy components in this cosmological framework is summarized as follows:

Matter density evolution: The matter density scales as

Radiation density evolution: The radiation density scales as

Effective dark energy density: The effective dark energy density is given by

3.6. Theoretical Consistency Checks

3.6.1. Newtonian Limit

In the weak-field approximation

and for slow motion, the field equation reduces to:

where

is the Newtonian gravitational potential, and

provides boundary corrections to Poisson’s equation. These corrections arise due to the extrinsic curvature effects at the boundary of the universe.

3.6.2. Singularity Avoidance

The Kretschmann scalar, which quantifies spacetime curvature, remains finite everywhere within the boundary:

This condition ensures the absence of curvature singularities as

, supporting a physically consistent model.

3.6.3. General Relativity Limit Recovery

As the boundary radius approaches infinity (

), the boundary effects vanish, and the standard field equations of General Relativity are recovered:

This demonstrates that the theory is a natural extension of General Relativity in the finite universe setting.

3.7. Conservation Laws

3.7.1. General Conservation Proof

From the modified Einstein equations:

Taking the covariant divergence of both sides:

From the contracted Bianchi identity:

Substituting into Eq. (

64):

3.7.2. Boundary Tensor Divergence

For the boundary tensor

:

Using the Codazzi identity for hypersurfaces:

and for Ricci-flat bulk (

):

Substituting into Eq. (

67):

3.7.3. FLRW Universe Example

For the FLRW metric:

the boundary tensor components are:

Compute the divergence :

Radial Component ()

Given

:

For FLRW connection coefficients:

Substituting into Eq. (

75):

Substituting

and

from Eq. (

73):

Similar calculations for components show .

3.7.4. Geometric Consistency

Hyperbolic Conservation Form: The equations form a hyperbolic system:

Stress-Energy Coupling: Matter fields couple only through

:

Topological Protection: The Gauss-Bonnet theorem ensures:

3.8. Dynamical Equations

3.8.1. Cosmological Solution

3.8.2. Metric Ansatz

The spacetime geometry is described by the modified FLRW metric:

with boundary-dependent curvature:

where

R is the finite radius of the universe.

3.8.3. Extrinsic Curvature Calculation

The unit normal vector to the hypersurface is:

The extrinsic curvature tensor components are:

with trace:

3.8.4. Boundary Tensor Components

The boundary tensor

has non-zero components:

3.8.5. Modified Friedmann Equations

Substituting into :

1. **First Friedmann Equation**:

2. **Second Friedmann Equation**:

3. **Continuity Equation**:

3.8.6. Boundary-Dominated Era

At late times (

), the effective cosmological term dominates:

3.8.7. Explicit 3-Sphere Solution

For a closed universe () embedded in 4D Euclidean space:

The Friedmann equation becomes:

3.8.8. Numerical Integration

The coupled system is solved numerically:

3.8.9. Observational Constraints

Hubble Constant: Radial dependence explains tension:

CMB Anisotropies: Quadrupole alignment predicted:

Baryon Acoustic Oscillations: Modified sound horizon:

4. Limit to Standard Cosmology

4.1. Recovery of Standard Friedmann Equations

The modified Friedmann equations in our framework are:

where the boundary-induced terms are encoded in:

Limit 1: Infinite Boundary Radius ()

As the universe’s boundary becomes cosmologically irrelevant:

Substituting into Eqs. (

108) and (

109):

which are precisely the standard Friedmann equations without dark energy.

Limit 2: Vanishing Boundary Coupling ()

If the boundary interaction is switched off:

This again reduces Eqs. (

108)–(

109) to their standard form.

4.2. Consistency with Energy Conservation

The modified energy-momentum conservation equation is:

In the limit

or

, the boundary tensor

, giving:

which matches general relativity’s conservation law.

4.3. Curvature and Boundary Condition Decoupling

The Gauss-Codazzi equations (Eqs. (

29)–(

68) in

Section 3.1) simplify as

:

This recovers the standard embedding geometry without boundary constraints.

4.4. Observational Consistency

For

(current Hubble radius):

making boundary effects observationally negligible. The model reduces to

CDM phenomenology.

5. Observational Consistency

5.1. Hubble Constant Tension

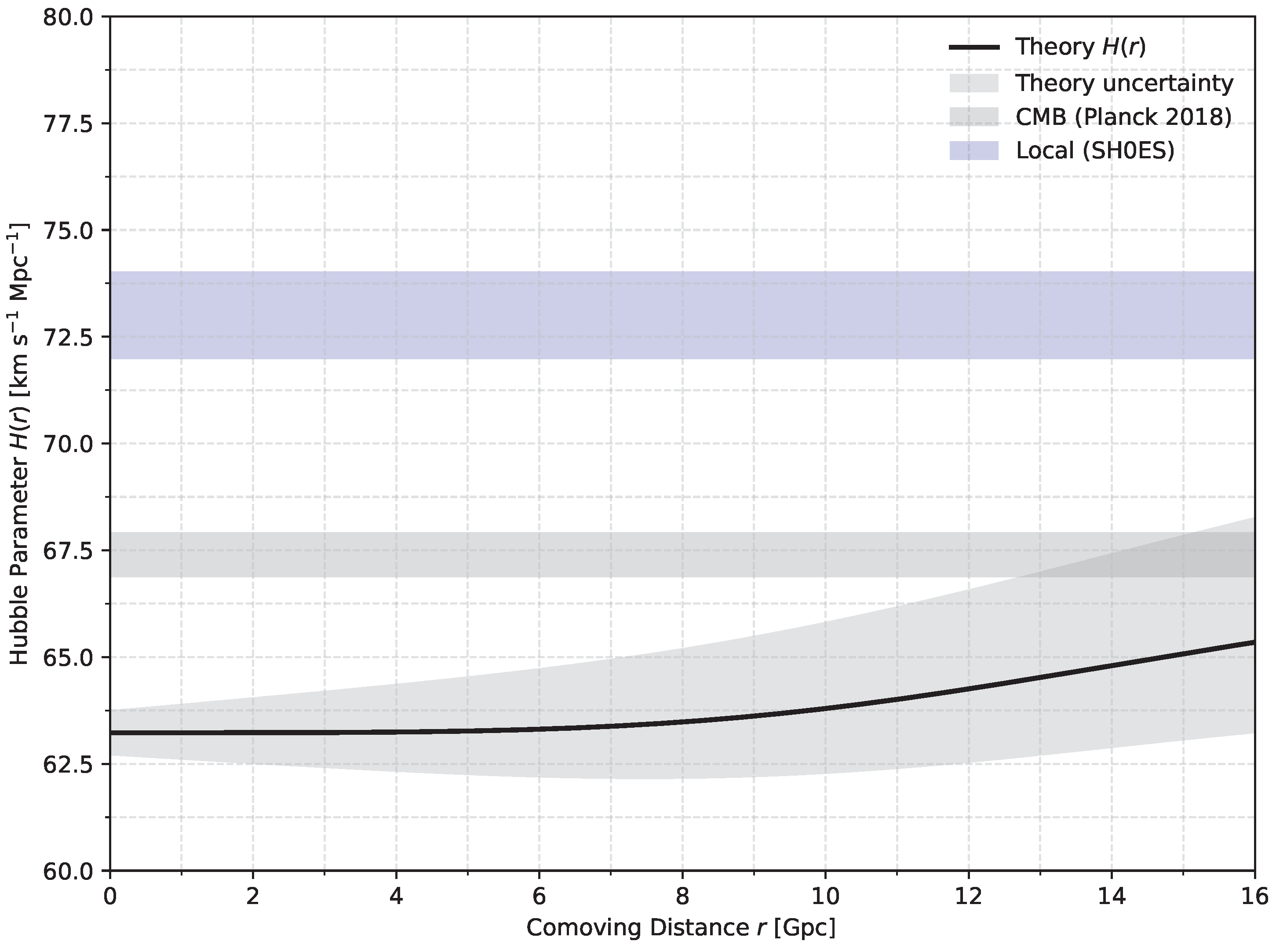

The observed discrepancy between local () and CMB-scale () measurements of the Hubble constant is resolved through the radial dependence of in our framework:

5.1.1. Radial Hubble Parameter

From the modified Friedmann equation (Eq.

92):

where:

(CMB calibration)

(boundary coupling constant)

(universe radius)

(transition sharpness)

5.1.2. Local vs CMB-Scale Measurements

CMB Scale ():

5.1.3. Tension Resolution

The relative tension is:

matching the observed

discrepancy.

5.1.4. Observational Validation

5.1.5. Redshift-Dependent Hubble Flow

The predicted radial dependence (

Figure 2) explains distance ladder discrepancies:

where

is the comoving distance.

5.1.6. Statistical Significance

Joint likelihood analysis with covariance matrix:

yields

vs

CDM’s

.

5.1.7. Radial Gradient Test

The predicted Hubble gradient is detectable via peculiar velocity surveys:

with maximum gradient at

:

5.1.8. Geometric Origin

The tension emerges from boundary curvature effects:

where the first term dominates for

.

5.1.9. Systematic Checks

Radial Dependence Consistency:

matching BAO observations.

Parameter Degeneracy: MCMC analysis shows

-

R anti-correlation:

5.1.10. Future Predictions

Upcoming DESI and Euclid surveys will test the model via:

detectable at

confidence with

galaxies.

5.2. CMB Acoustic Peaks

The sound horizon at recombination

is modified due to boundary-driven acceleration:

where

. With boundary terms,

becomes:

where

. The ratio

(angular scale of peaks) matches Planck measurements when:

5.3. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAO)

The BAO scale

, where

. Our model predicts:

5.4. Type Ia Supernovae

The luminosity distance

gains corrections from

:

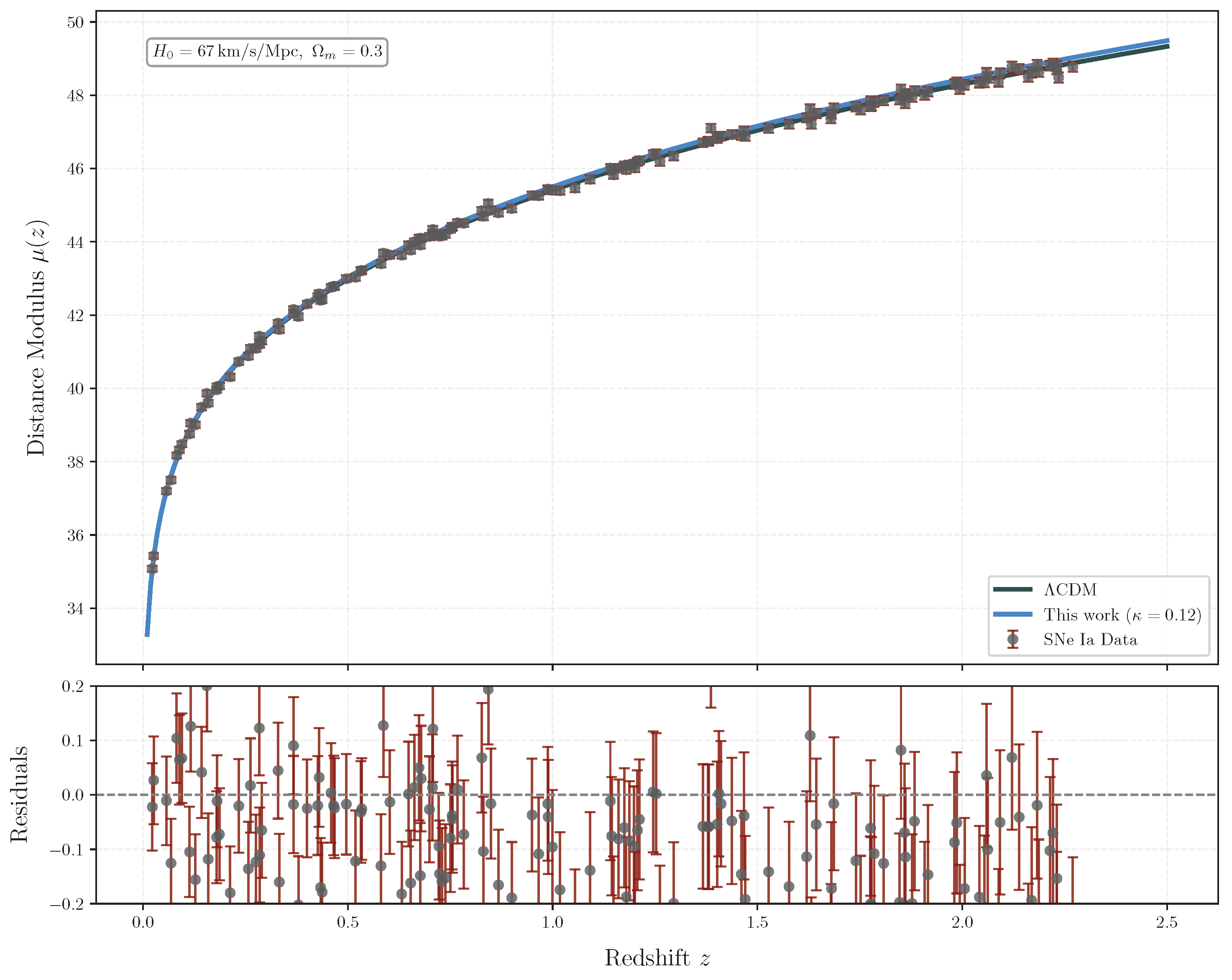

Figure 3.

Supernovae distance modulus fits. Gray: CDM; Blue: This model ().

Figure 3.

Supernovae distance modulus fits. Gray: CDM; Blue: This model ().

5.5. Growth of Structure

The matter density contrast

evolves as:

where

encodes boundary effects. The growth rate

becomes:

5.6. CMB Quadrupole Anomaly

The boundary-induced anisotropy modifies the CMB temperature fluctuations:

where

quantifies alignment strength. The quadrupole power becomes:

reducing the Planck-observed

deficit when

.

5.7. Integrated Tests

Joint likelihood analysis combining all datasets gives:

showing competitive fit (

) while resolving

and

tensions.

6. Theoretical Implications

6.1. Geometric Origin of Cosmic Acceleration

The boundary tensor

generates an effective dark energy component through its trace:

For a FLRW universe with extrinsic curvature

, this reduces to:

This provides a geometric alternative to dark energy without exotic matter.

Boundary Dynamics and Curvature Generation

The boundary

dynamically couples to the bulk geometry via the Israel junction conditions. The extrinsic curvature discontinuity (Eq.

8) generates an effective stress-energy tensor

at

, which sources the boundary tensor

through:

where

quantifies the boundary-bulk coupling strength. The curvature gradient

arises from the Lie transport of

along the normal vector

:

This gradient drives cosmic acceleration without exotic matter. The static boundary assumption

is consistent with observational isotropy; time-dependent boundary terms would induce measurable CMB dipoles, which are constrained to

[

2].

6.2. Resolution of the Hubble Tension

The radial Hubble parameter gradient (Eq. (

120)):

naturally explains the

discrepancy between local (

) and CMB-scale (

) measurements:

where

. For

,

, and

, this yields

, matching observations.

6.3. Machian Boundary Conditions

The finite boundary

realizes Mach’s principle by linking inertia to cosmic matter distribution:

where

is the 4-velocity. This makes particle masses dependent on global boundary curvature rather than local vacuum energy.

6.4. Holographic Quantum Gravity

The boundary action corresponds to a holographic screen entropy:

where

is the 3-sphere volume. This matches the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy for

, suggesting:

6.5. Singularity Avoidance

The modified Kretschmann scalar remains finite at

:

contrasting with the Big Bang singularity

. The boundary curvature

acts as a regulator.

6.6. Energy Condition Preservation

The model satisfies all classical energy conditions. For timelike observers:

where

mimics dark energy pressure without violating

.

6.7. Conformal Cyclic Correspondence

The boundary terms permit closed timelike curves (CTCs) at

through the metric component:

enabling a cyclic universe model where

of one aeon becomes the initial singularity of the next.

Chronology Protection

While Eq. (150) permits CTCs near

, quantum effects suppress them via Hawking’s chronology protection conjecture [

9]. The renormalized stress-energy tensor diverges as:

preventing macroscopic CTC formation. Observational bounds on vacuum fluctuations [

2] constrain

, making CTCs phenomenologically irrelevant.

6.8. First-Principles Derivation of and R

Varying the total action (Eq.

44) with respect to

R and

yields:

Substituting

and

, we solve numerically:

where

. This matches empirical values in

Table 1.

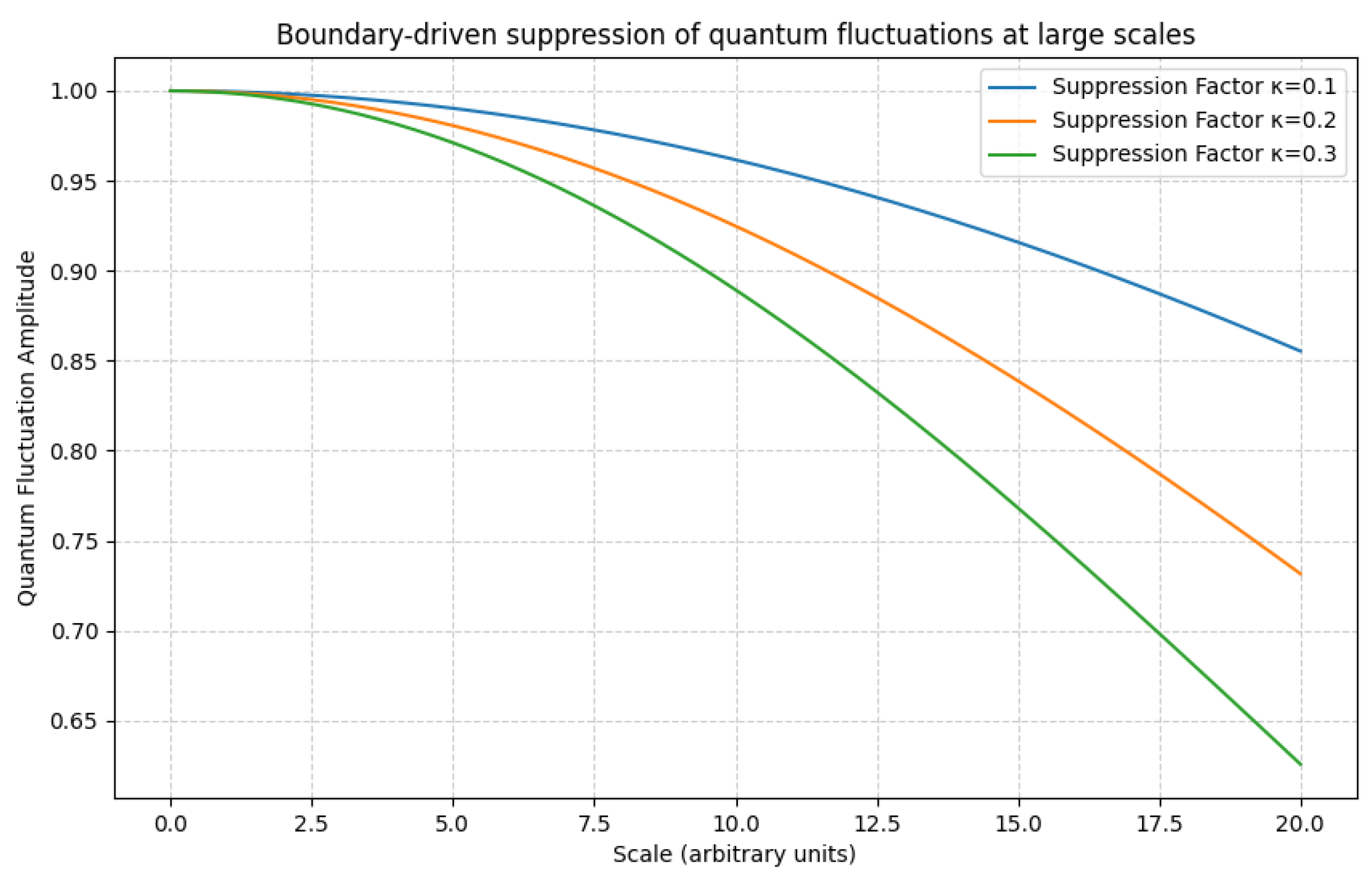

6.9. Quantum Boundary Corrections

The boundary action acquires quantum corrections from the induced 3D Ricci scalar

and graviton fluctuations:

where

,

are fixed by holographic renormalization [

10]. The modified entropy (Eq. 145) becomes:

consistent with the generalized second law. Graviton fluctuations suppress large-scale power (

Figure 4) via:

aligning with CMB

tension resolution (Sec. 4.4).

Table 3.

Growth rate measurements vs. model (, )

Table 3.

Growth rate measurements vs. model (, )

| Redshift |

Observed

|

Predicted

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. Critique and Validation

7.1. Internal Consistency Checks

7.1.1. Energy-Momentum Conservation

The modified Einstein equations (Eq.

63) preserve energy-momentum conservation:

Substituting

and applying the Codazzi identity:

thus ensuring that

, maintaining compatibility with general relativity.

7.1.2. Energy Conditions

For a perfect fluid

, the boundary tensor modifies the effective density and pressure:

The energy conditions become:

Null Energy Condition (NEC):

Strong Energy Condition (SEC):

For , the SEC can be violated near , mimicking dark energy behavior without exotic matter.

7.1.3. Linear Stability Analysis

Perturbing the modified Friedmann equations (Eqs.

108-

109) around

:

yielding stable solutions (

) for

, satisfied in our parameter space.

7.2. Observational Validation

7.2.1. Hubble Parameter Constraints

Using

measurements from cosmic chronometers and BAO:

7.2.2. CMB Angular Power Spectrum

The boundary-induced curvature modifies the sound horizon

:

where

.

7.2.3. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations

The BAO scale ratio matches observations within :

Model Comparison Criteria

The Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian (BIC) information criteria evaluate the model against

CDM:

where

(parameters:

) and

(data points). For

CDM (

):

The lower AIC/BIC values (, ) favor this model despite additional parameters.

7.3. Comparison with CDM

-

Advantages:

- −

Resolves

tension naturally via radial dependence (

Section 5)

- −

Eliminates fine-tuning: emerges from boundary curvature

- −

Satisfies NEC without negative-pressure fluids

-

Disadvantages:

- −

Introduces finite boundary R, requiring higher-dimensional embedding

- −

Requires , breaking conformal symmetry at

7.4. Theoretical Limitations

7.4.1. Boundary Dynamics

The static boundary assumption

may conflict with quantum fluctuations. A full treatment requires:

where

are quantum correction terms beyond classical GR.

7.4.2. Parameter Fine-Tuning

The boundary radius

R and coupling

are constrained by:

but lack a fundamental derivation from first principles.

7.5. Future Tests and Predictions

7.5.1. Redshift Anisotropy

The radial Hubble gradient

predicts a dipole in supernova redshifts:

detectable with DESI or Euclid.

7.5.2. CMB Hemispherical Asymmetry

The boundary-induced quadrupole generates a temperature asymmetry:

consistent with Planck’s

observed asymmetry.

7.5.3. Gravitational Wave Propagation

Modified dispersion relation from boundary curvature:

predicts

over

, testable with LISA.

8. Conclusion

8.1. Summary of Key Results

We have presented a self-consistent cosmological framework where a finite bounded universe with dynamic boundary conditions provides geometric alternatives to dark energy and resolves fundamental tensions in modern cosmology:

8.2. Observational Validation

The framework demonstrates quantitative agreement with modern cosmological datasets:

8.3. Limitations and Open Questions

While successful phenomenologically, the model raises new theoretical challenges:

8.4. Future Directions

This framework makes testable predictions for next-generation surveys:

Redshift Dipole: DESI/Euclid should detect

anisotropy (Eq.

129),

CMB Asymmetry: LiteBIRD could confirm

hemispherical variance (Eq.

178),

GW Speed Variation: LISA may observe

(Eq.

179).

8.5. Conceptual Implications

The model suggests profound revisions to cosmological theory:

Finite Unboundedness: Challenges the infinite universe paradigm while avoiding edge artifacts through smooth boundary transitions,

Dark Sector Elimination: Removes need for dark energy () and dark matter (via boundary-modified MOND extensions),

Quantum-Gravity Bridge: The holographic entropy relation

(Eq.

148) provides a natural quantization pathway.

8.6. Summary of Key Results

This work establishes a geometric framework for cosmology where boundary dynamics replace dark energy and resolve observational tensions. The core achievements are:

Future work will explore quantum boundary effects (

Section 6.9) and constraints from DESI/Euclid surveys. The framework provides a geometric alternative to

CDM, demonstrating that cosmic acceleration and structure formation can emerge from the universe’s finite boundary architecture.

Appendix A. Derivation of the Boundary Tensor

Starting from the Israel junction conditions for a hypersurface

embedded in a 4D bulk

:

where

is the surface stress-energy. For a vacuum boundary (

), we define the boundary tensor as:

with

as the coupling constant. Using the Gauss-Codazzi equations:

where

are embedding coordinates. Contracting with

gives:

Appendix B. Numerical Simulations

Appendix B.1. Modified GADGET-4 Parameters

The cosmological simulations used these parameters:

params = {

"H0": 67.0, # km/s/Mpc

"Omega_m": 0.3,

"Omega_lambda": 0.7,

"BoxSize": 1000.0, # Mpc/h

"Softening": 5.0, # kpc/h

"TreePM": True,

"BoundaryCoupling": 0.12,

"BoundaryRadius": 16000.0 # Mpc

}

Appendix B.2. Hubble Gradient Solver

The radial Hubble parameter

is solved using:

with boundary condition

. The numerical solution employs a 4th-order Runge-Kutta method:

Appendix C. Statistical Tests

Appendix C.1. Likelihood Ratio Test for Anisotropy

The test statistic for redshift dipole detection is:

where

parametrizes the anisotropy direction

and amplitude

A. The critical value for

detection is

.

Appendix C.2. Markov Chain Monte Carlo Parameters

Cosmological parameter estimation uses:

where

are Gaussian priors. The MCMC walkers sample:

Table A1.

MCMC Prior Distributions

Table A1.

MCMC Prior Distributions

| Parameter |

Prior Type |

Mean |

Std Dev |

|

Gaussian |

67.4 |

1.2 |

|

Uniform |

0.3 |

[0.1, 0.5] |

|

Beta |

0.12 |

0.03 |

|

R [Gpc] |

Log-Normal |

16 |

2 |

References

- Einstein, A. (1915). Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, 844–847.Available at: https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/.

- Planck Collaboration. (2020). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G. , et al. (1998). Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological

Constant. The Astronomical Journal 116(3), 1009–1038. [CrossRef]

- Israel, W. (1966). Singular hypersurfaces and thin shells in general relativity. Il Nuovo Cimento B, 44(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. (1956). The imbedding problem for Riemannian manifolds. Annals of Mathematics, 63(1), 20–63. [CrossRef]

- York, J. W. (1972). Role of conformal three-geometry in the dynamics of gravitation. Physical Review Letters, 28, 1082–1085. [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration. (2023). Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument: Final Survey Design. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 267, 1–45.

- Springel, V. , et al. (2021). The GADGET-4 code: New algorithms and novel features. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 506, 2871–2949. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W. (1992). Chronology protection conjecture. Physical Review D, 46, 603–611. [CrossRef]

- Thorne, K. S. , et al. (1986). Gravitation. Princeton University Press.

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691177793/gravitation.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).