1. Introduction

The administration of anesthesia plays a pivotal role in modern medicine by enabling pain-free surgical procedures and ensuring patient safety. Anesthetics can be categorized into general, regional, and local types, each tailored to the specific needs of surgical interventions. Drugs like propofol, pancuronium, and atracurium serve critical roles in maintaining unconsciousness and facilitating muscle relaxation during surgeries. Despite advancements in pharmacology, accurate dosing remains challenging, particularly for pediatric patients, due to their developing organs and metabolic variability. Technological advancements in anesthesia delivery have enhanced the understanding of propofol’s mechanisms, optimizing its pharmacodynamics for faster and safer outcomes. However, its use necessitates careful dosing and monitoring to balance efficacy with safety, especially in vulnerable pediatric populations [

1,

2].

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing clinical care by acting as a supportive tool for healthcare professionals rather than replacing them, as noted by [

3]. In particular, Machine Learning (ML), a branch of AI, is proving to be a game-changer, especially in resource-constrained settings. ML enables computers to learn and improve over time by analysing training data, as described by) [

4]. This technology encompasses machine learning and deep learning (DL), with ML functioning as a way for systems to enhance their performance through experience.

Machine learning (ML) techniques can be broadly categorized into supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning, all of which have shown great potential in healthcare. These methods are being applied to areas like drug development and personalized treatment plans. However, there remains a significant gap between AI research and its practical use in clinical anesthesia.

In the field of anesthesia, AI models are being developed to improve dosage prediction, ensuring that treatments are tailored to individual patients. These models use patient data derived from large-scale population studies to predict the optimal amount of anesthesia and its likely effects. Advanced ML techniques play a key role in this process. For example, supervised learning is used to train models on labeled datasets, while feature selection identifies the most important patient attributes for accurate predictions. Ensemble learning further enhances the performance of these tools by combining multiple models. To maintain reliability across different scenarios, methods like cross-validation are employed, helping the models perform consistently well on varied datasets and conditions.

The integration of AI into anesthesia represents a significant step forward, narrowing the gap between innovative research and practical, real-world applications. This progress has the potential to improve patient outcomes on a global scale.

Administering anesthesia is a critical component of patient care, requiring precision and flexibility to address individual needs. Traditional approaches often struggle to predict the ideal drug type and dosage due to the wide variability in how patients respond to anesthesia. This challenge is even more pronounced in pediatric cases, where the complexity of developing organs adds another layer of difficulty. Such unpredictability can increase risks, extend recovery times, and escalate healthcare costs. AI-driven solutions offer a promising way to address these challenges and enhance the safety and efficiency of anesthesia administration.

Machine learning (ML) offers a promising solution to these challenges by enabling the creation of predictive models tailored to each patient. These models improve safety and outcomes by providing more accurate drug and dosage recommendations, as highlighted by [

5].

Ensuring the correct dosage of anesthesia medication during surgery is essential for a safe and effective anesthetic experience. Traditionally, anesthesiologists rely on their expertise, training, and clinical judgment to determine the appropriate dose. However, with advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and its integration into medical practices, this process is poised to evolve, as highlighted by [

6]. AI-driven models have the potential to support anesthesiologists by providing data-driven insights and recommendations, improving precision, and enhancing patient safety during surgical procedures.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has shown immense potential in healthcare, transforming areas such as diagnosis, treatment recommendations, and predictive. For instance a machine learning model capable of analyzing data to classify individuals suffering from depression, providing valuable insights for mental health management. Similarly, neural network model was designed to aid in the diagnosis of schizophrenia, demonstrating AI’s growing role in advancing precision and efficiency in mental health care. These developments highlight the expanding possibilities of AI in supporting and enhancing clinical decision-making [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Techniques like machine learning, fuzzy logic, and neural networks are essential for training models that can execute complex calculations and emulate brain functions, paving the way for AI to support anesthesia management. Although the use of AI in anesthesia is still emerging, there is a growing interest in exploring its diverse applications [

11,

12,

13].

Different machine learning (ML) models are suited to specific types of applications, and selecting the most effective model for a given task is not straightforward. Testing and fine-tuning every possible ML algorithm is rarely feasible, as this process can be both complex and extremely time-consuming.

This is where Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) systems become valuable. AutoML systems streamline the process of finding the most effective ML model and configuring it optimally by automatically tuning hyperparameters and identifying the best model architecture within defined time limits.

AutoML systems automate the entire ML pipeline, covering four main phases: data preparation, feature engineering, model generation, and model evaluation. Users only need to provide their data, and the AutoML system will identify and implement the optimal approach for their specific application.

2. Related Works

Various machine learning techniques were compared to multiple linear regression (MLR) for predicting stable tacrolimus doses in renal transplant recipients. Tang and colleagues employed eight machine learning algorithms, including Support Vector Regression (SVR), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Regression Tree (RT), Random Forest Regression (RFR), Boosted Regression Tree (BRT), and Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART). Their findings showed that the Regression Tree model performed best, providing both high accuracy and clinical interpretability, their study also highlighted the advantages of machine learning techniques over traditional statistical models, such as MLR, in pharmacogenetic studies. Machine learning models demonstrated a higher power to manage non-linear data and interpret complex interactions within large datasets, including genetic data, which is often crucial in personalized medicine. It was also observed that the ideal dosing rate of the Regression Tree was 4% higher than MLR, illustrating the potential for machine learning models to improve clinical outcomes through better dose prediction [

14].

ML algorithms can be categorized into three main types: supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning. Among these, supervised learning is frequently used to classify or label new data based on previously labeled datasets [

15]. Furthermore, ML can uncover complex, nonlinear interactions between variables, minimizing errors in predictions by aligning them closely with actual measured values [

16].

For instance, algorithms like decision trees and random forest (SVMs) are employed prediction of a continuous trait using machine learning techniques with application to warfarin dose prediction [

17]. Additionally, ML models assist healthcare practitioners in selecting appropriate therapies by analyzing large, complex datasets, such as electronic health records and medical imaging data [

18]. Several studies have demonstrated the potential of ML in anesthesia. Similarly, neural networks was utilized to predict the depth of anesthesia, achieving high classification accuracy [

19]. Other researchers, focused on pain assessment, using ML to enhance post-anesthesia care by predicting patient responses to analgesia. This study supports the Incorporation of machine learning in clinical settings for dose optimization. By leveraging patient-specific factors, machine learning models like Regression Tree can enhance precision in dosing, which is essential in minimizing risks and improving patient safety in immunosuppressive therapy [

20].

ML models to predict anesthetic infusion events, while [

21] introduced time-delay estimation for predictive control in general anesthesia. These studies highlight the effectiveness of ML in optimizing anesthesiologist decisions and improving patient care. ML algorithms can process clinical charts more efficiently and accurately than manual review processes, enabling healthcare providers to uncover hidden risk factors and healthcare gaps, enhance risk score accuracy, and make better-informed decisions for improved patient care, [

22]. Moreover, ML can automate various healthcare operations, such as claims processing, revenue cycle management, and clinical documentation, thereby increasing the efficiency of healthcare workflows. Machine learning (ML) has demonstrated substantial potential in anesthesia, particularly in optimizing personalized anesthesia dosage. Multiple studies have explored the use of AI-driven algorithms to enhance the precision of anesthesia delivery, improve patient safety, and support anesthesiologists in making data-driven decisions [

23].

The study titled “Prediction of Pharmacokinetic Parameters Using a Genetic Algorithm Combined with an Artificial Neural Network for a Series of Alkaloid Drugs” highlights the application of artificial intelligence, specifically genetic algorithms (GA) and artificial neural networks (ANN), in pharmacokinetics. The research emphasizes the development of predictive models for systemic clearance, volume of distribution, and plasma protein binding of alkaloid drugs. These models utilize molecular descriptors derived from three-dimensional structural data to enhance prediction accuracy.

The integration of GA with ANN addresses the limitations of each technique: GA optimizes the selection of molecular descriptors, while ANN constructs robust predictive models. This combined approach demonstrates acceptable efficiency, as evidenced by normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) values, and aligns with advancements in machine learning for healthcare applications, such as personalized drug dosing and predictive analytics discussed earlier. The findings underscore the role of AI in enhancing pharmacokinetic predictions and its broader potential in improving clinical outcomes, particularly through tailored therapeutic strategies. [

24]

The study, Predicting Anaesthetic Infusion Events Using Machine Learning, addresses the shortcomings of manual anaesthetic dosage methods by leveraging machine learning models like Linear Regression, Decision Tree Regression, and Gradient Boosting Regression. Gradient Boosting Regression emerged as the most effective, offering superior accuracy and reducing medication errors. A user-friendly interface was designed to aid healthcare practitioners, enhancing clinical decision-making.

Key system features include personalised dosage recommendations, automation for efficiency, error reduction, data-driven insights, and adaptability through continuous learning. Future directions include expanding datasets, refining features, and exploring ensemble methods to improve predictive capabilities. This work underscores the potential of machine learning to enhance patient safety and streamline clinical workflows in anaesthesia management. [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]

3. Materials

The project leveraged a robust computational setup, featuring an HP system equipped with an Intel Core i5 processor and 8 GB RAM. Central to the analysis were Python and the Anaconda Integrated Development Environment (IDE), with Python’s simplicity and versatile libraries playing a critical role in handling data and building models. Jupyter Notebook, part of the Anaconda ecosystem, was the preferred interface for coding, visualisation, and text-based exploration.

Data Collection and Augmentation

The dataset, sourced from Lagos State Teaching Hospital (LUTH), included 606 anonymised records of paediatric patients under anaesthesia. Data points ranged from age and weight to drug types and dosages. To enrich the dataset and ensure better model performance, synthetic data augmentation expanded the records to 1,200 samples while maintaining realistic distributions.

Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Data preparation entailed meticulous cleaning, including handling missing values, outliers, and normalisation of features such as age and weight. These factors were the key predictors for determining dosages of drugs like propofol and atracurium. Additionally, a correlation matrix revealed strong relationships between patient features and drug dosages, guiding model development. The dataset was scaled using the `StandardScalerKey.

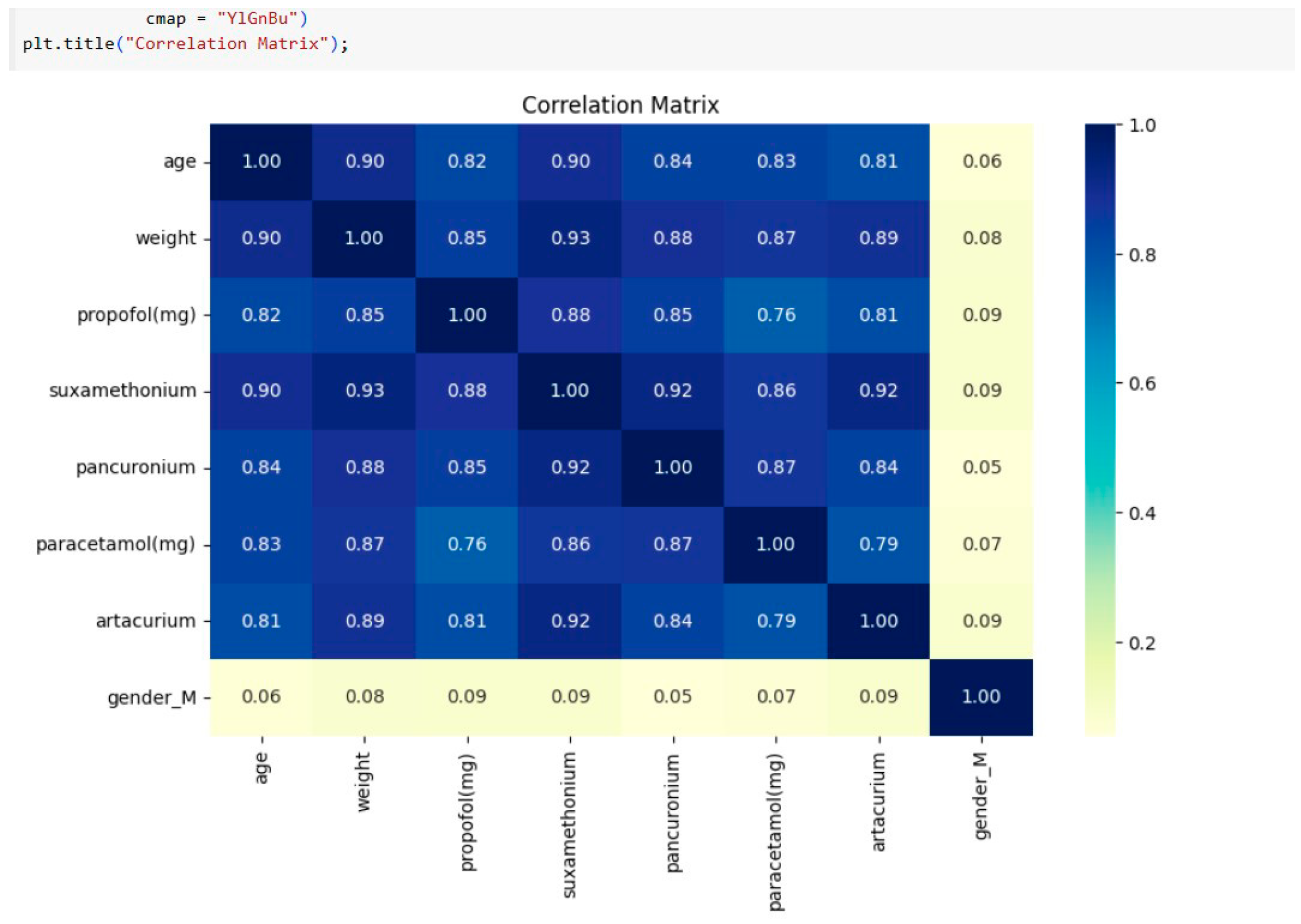

Correlation matrix of the features: The correlation matrix below reveals several important relationships between patient characteristics as shown in

Figure 1 (age, weight and gender) and the administered drug dosages. Drugs like

propofol, suxamethonium,

pancuronium and

atracurium exhibit stronger positive correlations with age, gender and weight.

- -

Data Splitting: An 80-20 split was used for training and testing datasets to enhance model generalisation.

Machine Learning Models: The study utilized machine learning algorithms including linear regression, decision trees, and gradient boosting. Data from healthcare records were preprocessed to address missing values and normalize features. Models were trained using an 80/20 train-test split, and hyperparameters were optimized via genetic programming. Evaluation metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-squared values were employed to assess performance. Several regression models were developed to predict anaesthetic drug dosages, including:

Building a Model:

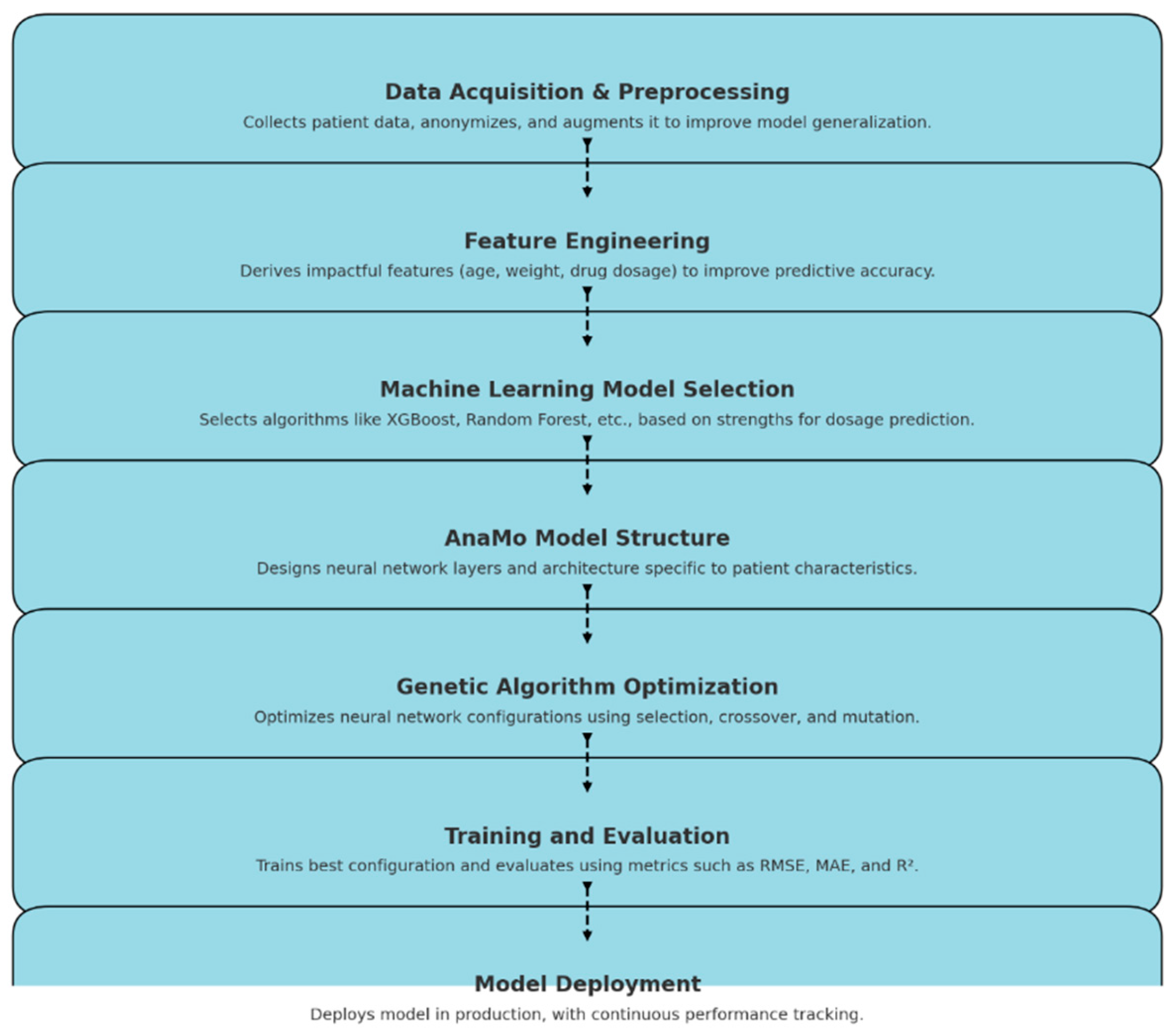

This process involves building various machine learning models as shown in

Figure 2.0 starting from data collection to model deployment, predicting the dosage based on patient features such as age and weight. The models utilized include Random Forest Regressor, Linear Regression, XGBoost, and and AnaMo (Automated Neural Architecture Model Optimiser), was implemented. AnaMo stood out due to its innovative use of genetic programming to optimise neural network configurations. Through evolutionary cycles involving selection, crossover, and mutation, AnaMo refined its predictive accuracy.Models were evaluated using metrics such as:

- -

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

- -

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- -

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- -

R-squared (R2)

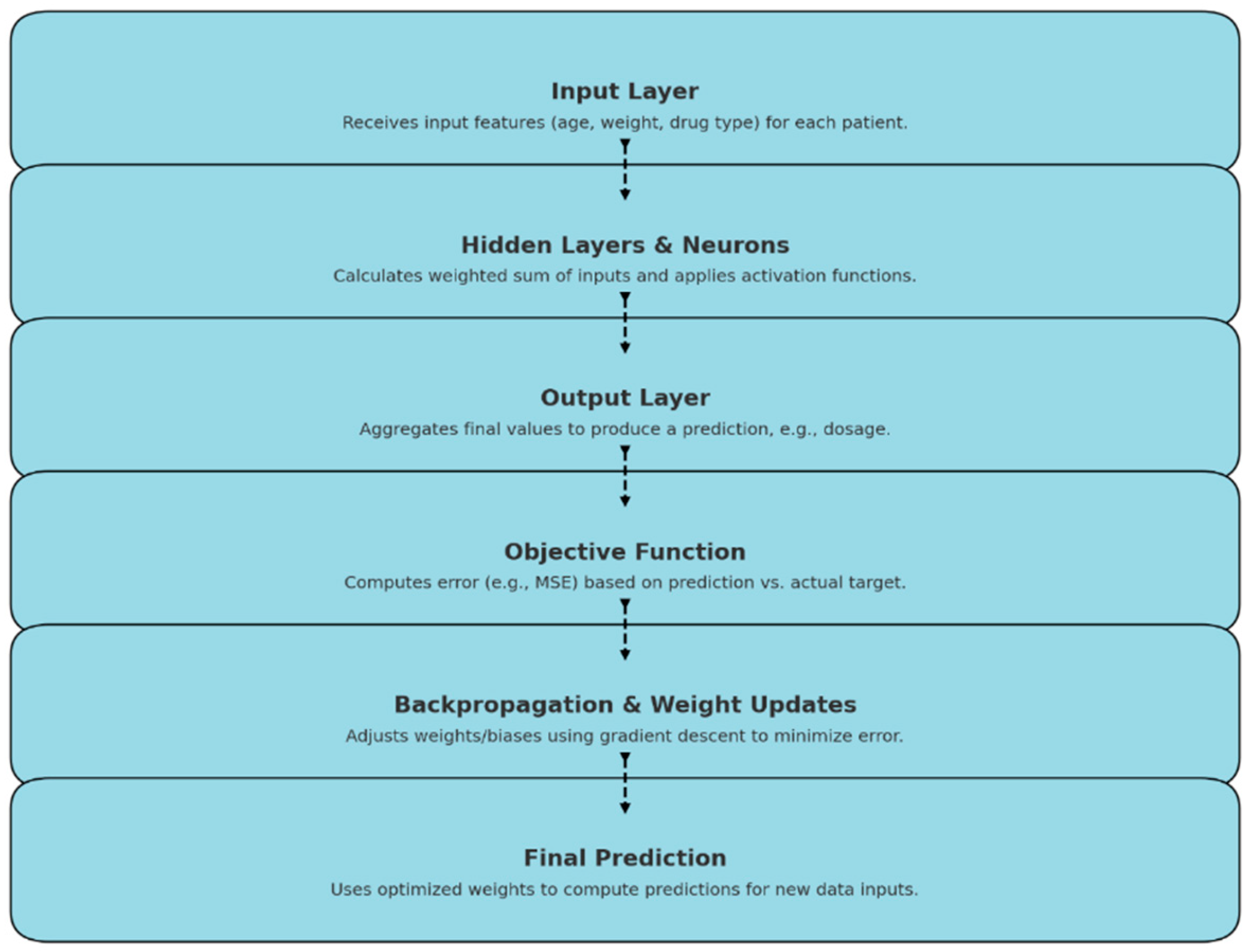

An (Automated Neural Architecture Model Optimizer): AnaMo was designed which applies genetic programming to the hyperparameter optimization of neural networks. The AnaMo model, based on a neural network architecture, computes its output through a sequence of forward propagation steps as shown in

Figure 3.0 the AnaMo model’s output computation involves processing inputs through layered transformations and applying weights, biases, and activations to produce accurate predictions tailored to the specific features of each patient

- 1.

Neural Network Architecture

The core of the AnaMo model is a neural network where each layer is defined by:

- -

Layer configuration: The number of neurons in each layer of the network.

- -

Activation functions: The activation function for each layer (e.g., ReLU, Tanh, Sigmoid).

For a given input

, the network’s prediction

is calculated by forward propagation:

where:

is the output of layer

,

and are the weights and biases for layer ,

is the total number of layers.

The final layer’s output gives the model prediction:

Evaluation Metrics

After selecting the best configuration, the model is evaluated using metrics beyond MSE:

The model aims to minimize the Mean Squared Error (MSE) on the training dataset, defined as:

where:

is the actual target value,

is the model’s predicted value,

is the number of samples.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

1. R-Squared (Coefficient of Determination):

where

is the mean of actual values

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval (ADM/DSCST/HREC/APP/6639) was obtained, and patient confidentiality was maintained. All procedures adhered to ethical guidelines for human data usage in research.

Model Deployment

Finalised models were deployed using Visual Studio Code, ensuring reproducibility through serialisation using tools like `joblib`. Deployment processes enabled real-world dosage predictions.

4. Results and Discussion

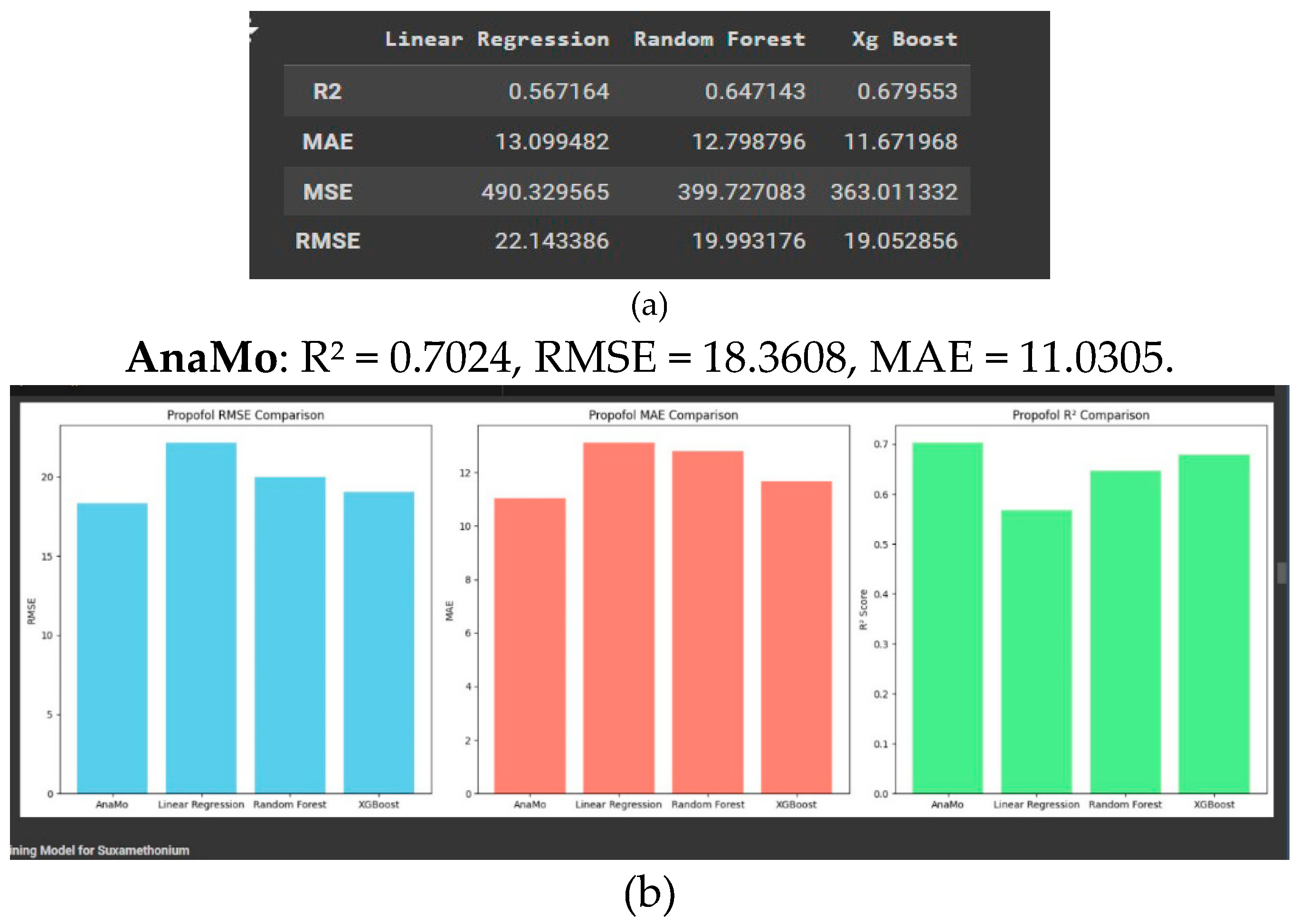

The study evaluates four machine learning models AnaMo, Linear Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost on their ability to predict the concentrations of various anaesthetic drugs. The performance of each model was assessed using key metrics: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R2.

This report presents a comparative analysis of four machine learning models Linear Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost as shown in

Figure 4a and 4.b showing machine learning result, evaluated on their ability to predict propofol concentration. The comparison is based on three performance metrics: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R

2 score as shown in figure. These metrics provide insights into each model’s prediction accuracy, error consistency, and ability to capture variance in the data.

- 1.

Propofol Prediction

AnaMo’s optimised architecture demonstrated its capability to handle the complexity of propofol dosage predictions better than Linear Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost.

- 2.

Suxamethonium Prediction

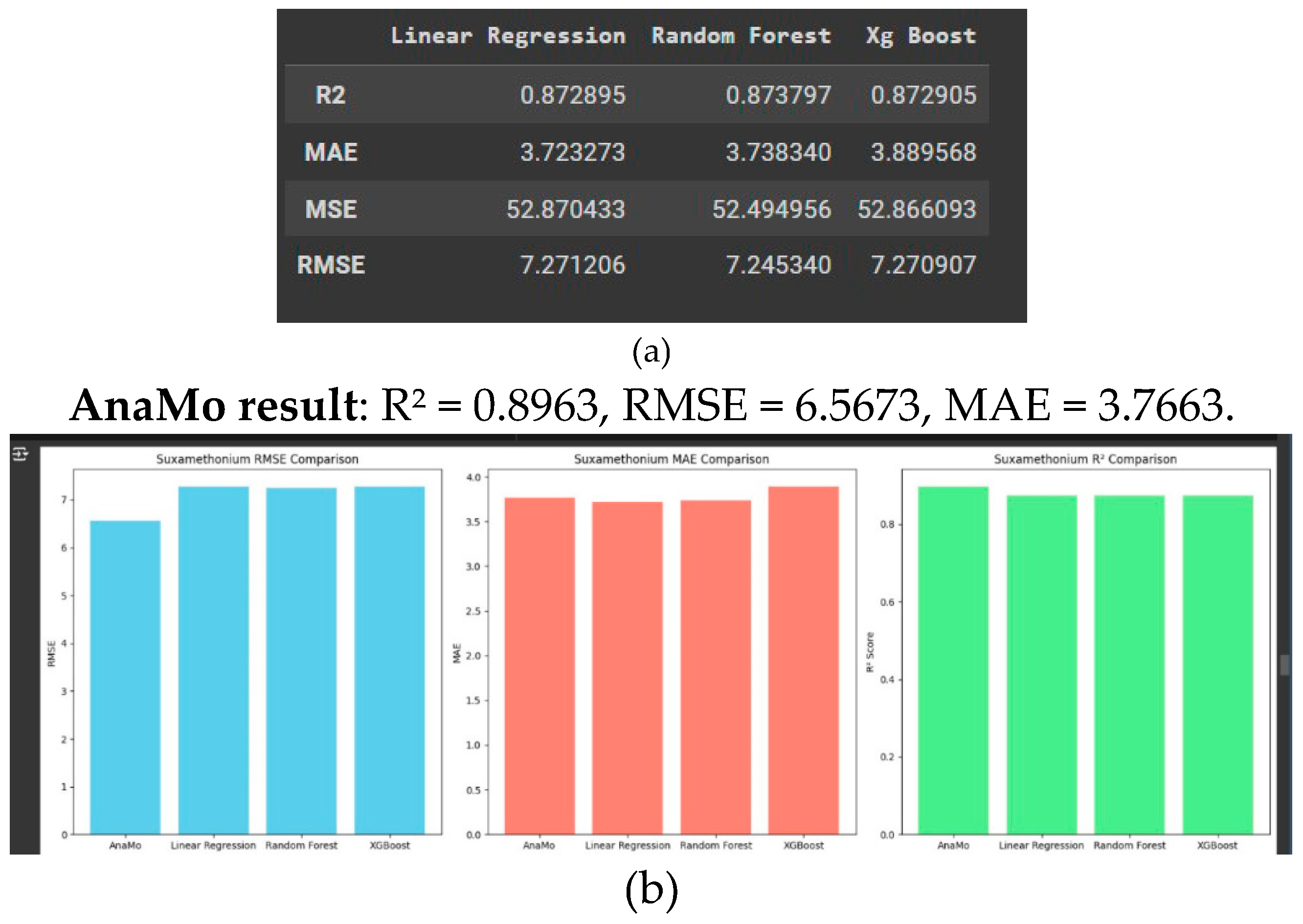

This report provides a comparative analysis of the four models as shown in

Figure 5a, 5b. Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and R

2 score, which collectively provide insights into each model’s prediction accuracy, error consistency, and capability to explain the variance in the dataset.

AnaMo excelled with a high R2, indicating strong reliability and precision for predicting suxamethonium concentrations.

The low RMSE and MAE highlight AnaMo’s ability to handle variance and minimise prediction errors.

- 3.

Artacurium Prediction

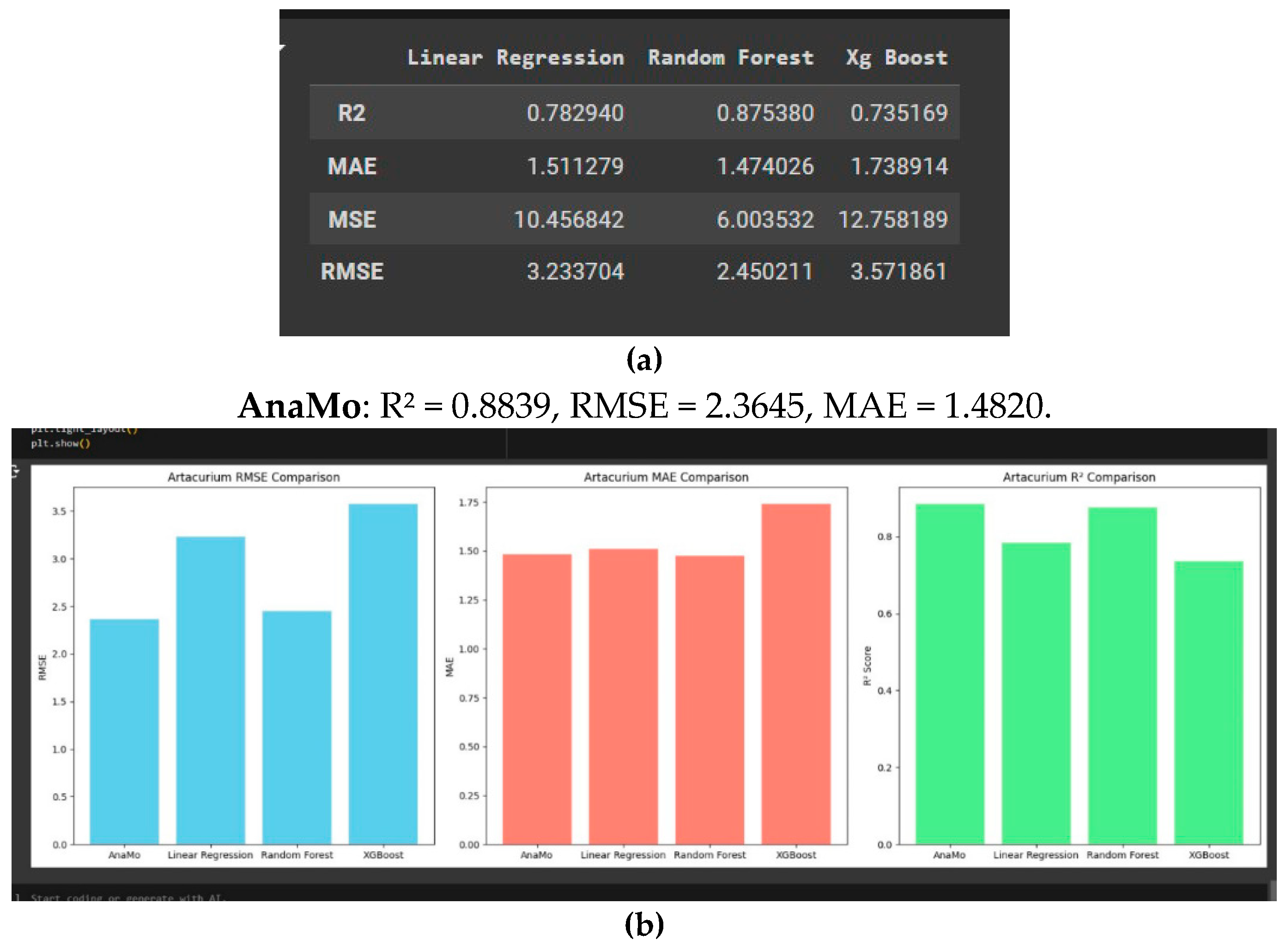

This analysis compares the models AnaMo, Linear Regression, Random Forest, and as shown in

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b. Linear Regression and Random Forest show comparable, moderate performance, making them viable alternatives but less precise than AnaMo. XGBoost shows the highest RMSE and MAE with the lowest R

2 score, indicating it is the least suitable model for artacurium prediction. AnaMo is the most accurate and reliable model for predicting artacurium concentration, while XGBoost is less effective for this task.

- -

Results: AnaMo again emerged as the top performer, with an R2 of 0.8839, an RMSE of 2.36, and an MAE of 1.48. Linear Regression and Random Forest were moderate alternatives, while XGBoost exhibited the weakest performance with higher error rates and lower explanatory power.

- -

The results underscore AnaMo’s dominance in predicting atracurium concentration, attributed to its genetic programming-based optimisation

- 4.

Pancuronium Prediction

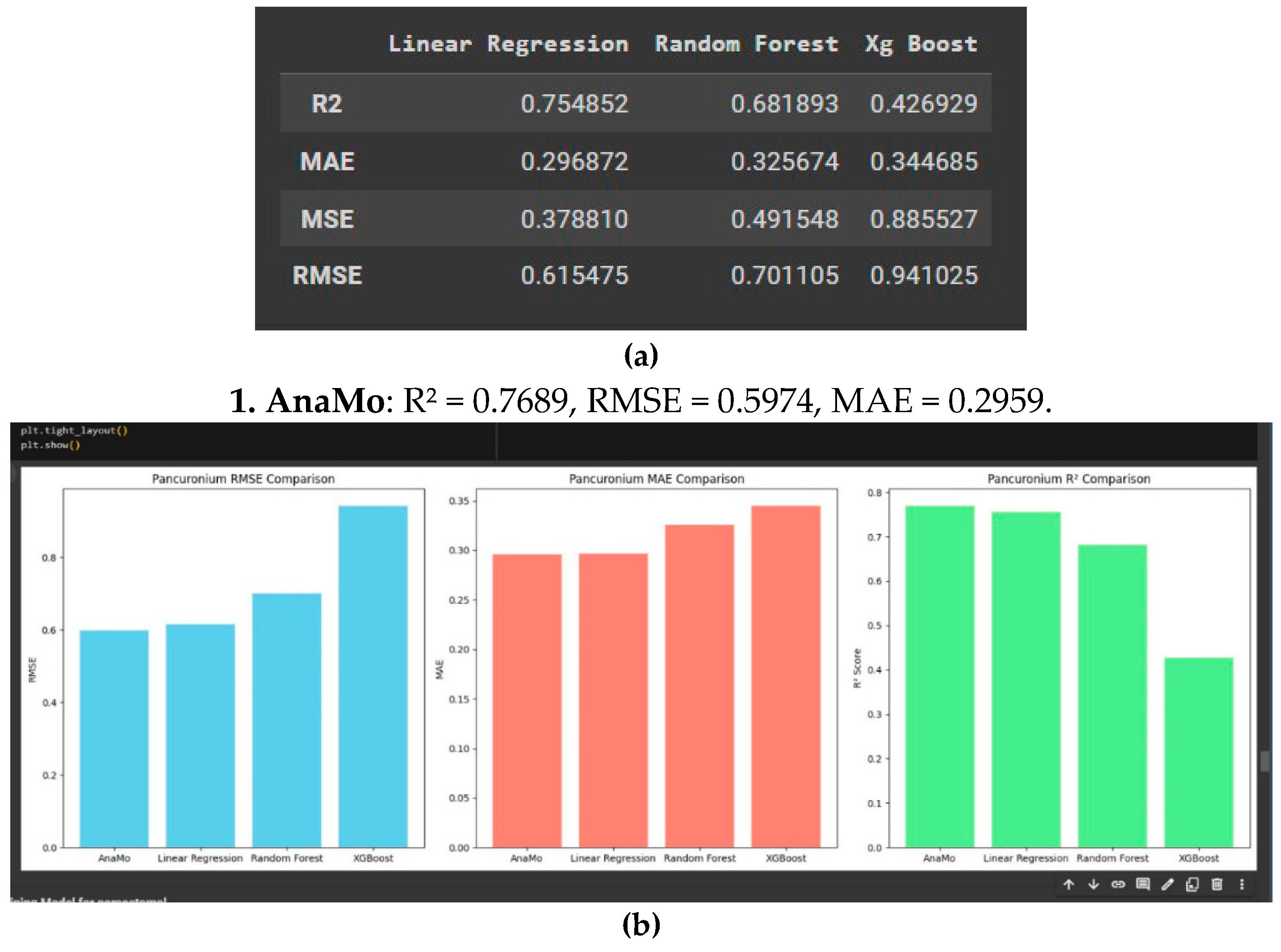

As shown in

Figure 7a and 7b

AnaMo and Linear Regression are the most effective models for predicting pancuronium concentration, displaying the lowest errors and highest explanatory power.

Random Forest can be considered a viable option, though slightly less consistent, while

XGBoost performs poorly and is less reliable for this application. AnaMo’s genetic programming-based optimization likely contributes to its superior performance, result is shown in Table 4.4, making it a strong choice for accurate pancuronium concentration predictions.

2. AnaMo and Linear Regression were the most effective models, demonstrating strong predictive accuracy and low error rates, with AnaMo achieving an R2 of 0.7689, an RMSE of 0.597, and an MAE of 0.296. Random Forest was a viable option but less consistent, while XGBoost struggled to perform well.

3. AnaMo’s ability to adapt and optimise parameters for pancuronium predictions was evident, providing precise and consistent results.Random Forest performed reasonably well but less consistently than AnaMo, while XGBoost lagged significantly.

Discussion

AnaMo consistently outperformed traditional models (Linear Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost) due to its use of genetic programming for hyperparameter optimisation. This enabled AnaMo to adapt to different data distributions and provide precise dosage predictions. It particularly excelled in predicting suxamethonium and artacurium concentrations, with high R2 scores and low error metrics AnaMo’s robustness and adaptability as the leading model for predicting anaesthetic drug concentrations. Its ability to handle diverse datasets and maintain low error rates across various drugs makes it the most reliable choice. Other models, while useful in simpler scenarios, lagged behind in predictive power, especially for complex drugs like propofol and atracurium. These findings set a solid foundation for applying AnaMo in real-world medical contexts.

Key Findings and Contributions

This study evaluates machine learning (ML) models for predicting drug concentrations in pediatric anesthesia and highlights the AnaMo model as the most effective due to its genetic programming-based hyperparameter optimization. The analysis provides a comprehensive comparison of models and benchmarks their performance metrics, such as RMSE, MAE, and R2, offering insights into predictive modeling in healthcare.

Challenges in Personalized Medicine

Data Privacy and Security: Pediatric data management involves ethical concerns and securing consent from guardians.

Data Integration: Combining diverse data sources, including medical records, genetic profiles, and real-time physiological data, presents logistical complexities.

Clinical Implications

AI-powered models like AnaMo can:

Enhance Precision: Provide accurate, real-time dosage predictions, particularly important for pediatric patients with rapidly changing physiological conditions.

Improve Workflow Efficiency: Reduce time and effort for anesthesiologists while allowing real-time adjustments during procedures.

Retain Human Oversight: Serve as decision-support tools, aiding but not replacing clinical judgment.

Conclusions

The study validates AnaMo as the most accurate and reliable model for drug concentration predictions in pediatric anesthesia. Its potential to enhance patient safety and clinical efficiency is significant but requires addressing challenges in data quality, generalizability, and ethical compliance for broader adoption.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans.

Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Chidambaran, V.; Costandi, A.; D’Mello, A. Propofol: A Review of its Role in Pediatric Anesthesia and Sedation. CNS Drugs. 2015, 29, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA). Safety of Anaesthesia: A Review of Anaesthesia-Related Mortality Reporting in Australia and New Zealand 2015-2017; ANZCA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, I.S.; Burns, M.; Kendale, S.; Wanderer, J.P. Realistically integrating machine learning into clinical practice: A road map of opportunities, challenges, and a potential future. Anesth Analg. 2020, 130, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamet, P.; Tremblay, J. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Metabolism 2017, 69S, S36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinoth, M.; Ramana, M.; Lordson, S.R.B. Anesthesia prediction using machine learning. Int Res J Eng Technol (IRJET) 2024, 11, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, B.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendale, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Rosenberg, A.D.; Wang, J. Supervised machine-learning predictive analytics for prediction of postinduction hypotension. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 675–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwoye, E.O.; Fidelis, O.P.; Zacchaeus, J.E. Application of neural network algorithm for schizophrenia diagnosis. Nig J Technol. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Bihorac, A.; Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T.; Ebadi, A.; Motaei, A.; Madkour, M.; Pardalos, P.M. MySurgeryRisk: Development and validation of a machine-learning risk algorithm for major complications and death after surgery. Ann Surg. 2019, 269, 652–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchaeus, J.E.; Ige, E.O.; Ugo, H.C.; Fadipe, B.; Nwoye, E.O. A patient-centered text-derived neural paradigm for diagnosis of schizophrenia. IETA 2023, 37, 531–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Cong, C.; Yuanfeng, D.; Ding, W.; Li, J.; Yongfeng, S.; et al. Multidata analysis based on an artificial neural network model for long-term pain outcome and key predictors of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, e271–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.J.; Ku, T.H.; Jan, R.H.; Wang, K.; Tseng, Y.C.; Yang, S.F. Decision tree-based learning to predict patient-controlled analgesia consumption and readjustment. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, J.S.; Fan, S.Z.; Chang, L.W.; Liu, C.C. Hierarchical rule-based monitoring and fuzzy logic control for neuromuscular blocks. J Clin Monit Comput. 2000, 16, 583–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.L.; Liu, M.Z.; Hu, Y.F.; Shao, M.J.; Zhang, W. Application of machine-learning models to predict tacrolimus stable dose in renal transplant recipients. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 42192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goecks, J.; Jalili, V.; Heiser, L.M.; Gray, J.W. How machine learning will transform biomedicine. Cell 2020, 181, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Yamashita, T.; Sakama, T.; Arita, T.; Yagi, N.; Otsuka, T.; et al. Comparison of risk models for mortality and cardiovascular events between machine learning and conventional logistic regression analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0221911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgun, E.; Limdi, N.A.; Duarte, C.W. High-dimensional pharmacogenetic prediction of a continuous trait using machine learning techniques with application to warfarin dose prediction in African Americans. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1384–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Q.; Zhu, Y. Differentiation of bone metastasis in elderly patients with lung adenocarcinoma using multiple machine learning algorithms. Cancer Control. 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, M.I.; Saadeh, W. Monitoring level of hypnosis using stationary wavelet transform and singular value decomposition entropy with feedforward neural network. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2023, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghita, M.; Birs, I.R.; Copot, D.; Muresan, C.I.; Neckebroek, M.; Ionescu, C.M. Parametric modeling and deep learning for enhancing pain assessment in postanesthesia. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, B.; Wang, Y. Estimating the time-delay for predictive control in general anesthesia. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), 15-18 Dec 2021; pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Amponsah, A.A.; Adekoya, A.F.; Weyori, B.A. A novel fraud detection and prevention method for healthcare claim processing using machine learning and blockchain technology. Decision Analytics Journal 2022, 4, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaguchi, N.; Takeuchi, K.; Kashima, H.; Morita, M.; Morimatsu, H. Predicting anesthetic infusion events using machine learning. Sci Rep. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandkarimi, M.; Shafiei, M.; Hadizadeh, F.; Darbandi, M.A.; Tabrizian, K. Prediction of pharmacokinetic parameters using a genetic algorithm combined with an artificial neural network for a series of alkaloid drugs. Sci Pharm. 2014, 82, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, S.; Rajalaxmi, R.R. A data mining model for predicting the coronary heart disease using random forest classifier. Proc Int Conf Recent Trends Comput Methods Commun Controls. 2012, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Alkeshuosh, A.H.; Moghadam, M.Z.; Al Mansoori, I.; Abdar, M. Using PSO algorithm for producing best rules in diagnosis of heart disease. Proc Int Conf Comput Appl (ICCA) 2017, 306–11. [Google Scholar]

- Al-milli, N. Backpropagation neural network for prediction of heart disease. J Theor Appl Inf Technol. 2013, 56, 131–5. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, C.A.; Rajamhoana, S.P.; Umamaheswari, K.; Kiruba, R.; Karunya, K.; Deepika, R. Analysis of neural networks based heart disease prediction system. Proc 11th Int Conf Hum Syst Interact (HSI) 2018, 233–9. [Google Scholar]

- Anooj, P.K. Clinical decision support system: Risk level prediction of heart disease using weighted fuzzy rules. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2012, 24, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).