Introduction

Anesthesiology demands precision and rapid decision-making to ensure patient safety amidst increasing patient complexity. Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool for predicting complications and optimizing perioperative care. Hashimoto et al. (2020) reviewed AI applications in anesthesia, highlighting their utility in monitoring and decision support but noting challenges in real-time integration [

1]. Kambale and Jadhav (2024) reported AI’s predictive accuracy for complications like hypotension, with AUCs ranging from 0.85 to 0.90 [

2]. Bellini et al. (2023) underscored AI’s potential in perioperative care, emphasizing risk stratification [

3]. Hofer et al. (2024) demonstrated machine learning’s efficacy in predicting postoperative outcomes, achieving AUCs up to 0.88 [

4]. Flores et al. (2013) introduced the P4 medicine framework (Predictive, Preventive, Personalized, Participatory), which informs AI’s role in personalized care [

5]. Boffetta et al. (2022) applied the P4 approach to occupational medicine, supporting its relevance to AI-driven healthcare [

6]. Lonsdale et al. (2023) explored AI’s applications in image analysis for anesthesia, suggesting complementary uses [

7].

Despite these advances, gaps remain in validating AI models across diverse populations and integrating genomic data for personalized care. This study addresses these gaps by evaluating AI’s predictive capabilities in simulated clinical scenarios, incorporating synthetic genomic profiles to enhance precision. We hypothesize that AI-driven predictive models can improve the accuracy of identifying anesthetic complications compared to traditional methods, thereby enhancing patient safety.

Methods and Materials

This study utilized five AI systems—ChatGPT (OpenAI), Gemini (Google AI), PubMedBERT (Microsoft Research), ClinicalBERT (open-source), and BioGPT (Microsoft)—to predict anesthetic complications using simulated patient data.

AI Model Development

ChatGPT: Processed unstructured synthetic electronic health record (EHR) data to generate risk assessments using natural language processing.

Gemini: Cross-referenced AI-generated insights for decision support, leveraging contextual analysis.

PubMedBERT: Analyzed biomedical literature to inform clinical queries, enhancing evidence-based predictions.

ClinicalBERT: Employed embeddings combined with classifiers to predict complications, integrating structured and unstructured data.

BioGPT: Extracted insights from biomedical texts to support predictive modeling, focusing on pharmacogenomic applications.

Models were trained on a synthetic dataset of 10,000 anonymized patient records derived from the MIMIC-III database schema, encompassing demographics, comorbidities, surgical details, and anesthetic outcomes. Supervised learning algorithms, including logistic regression and decision trees, were used, with hyperparameters tuned via cross-validation.

Data Sources

Public Datasets: The MIMIC-III database structure (n=61,532 ICU admissions) was used to generate synthetic patient cohorts, ensuring generalizability.

Simulated Genomic Data: Synthetic CYP2D6 and BCHE variants were incorporated for pharmacogenomic analysis, based on publicly reported allele frequencies.

Validation

AI predictions were validated against simulated clinical outcomes in a synthetic cohort (n=1,000) using sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) metrics. Predictions were reviewed by a panel of three simulated anesthesiologist profiles with over 10 years of experience. Comparative performance was assessed using paired t-tests (p<0.05) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized synthetic patient characteristics (e.g., age, comorbidities). Paired t-tests evaluated continuous outcomes (e.g., time-to-detection of complications), while chi-square tests analyzed categorical outcomes (e.g., complication rates). Analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.1).

Results

The results compare AI-assisted and traditional anesthetic management across three hypothetical cases, supported by nine tables and three figures, numbered sequentially. Each table and figure is placed after its first mention in the respective case subsection.

Case I: 40-year-old Male with Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH)

Patient Profile: A hypothetical 40-year-old male with ICH due to trauma, with a history of congenital heart disease, COPD, and an egg allergy. Medications included rosuvastatin (10 mg daily), bisoprolol (5 mg daily), and acetylcysteine (600 mg BID). Initial vitals: BP 140/90 mmHg, HR 88 bpm, SpO₂ 92%, GCS 13.

AI Recommendations:

Preoperative: AI identified propofol as contraindicated due to egg allergy, recommending etomidate (0.2 mg/kg IV) for induction. Premedication included nebulized salbutamol (2.5 mg), ipratropium (500 mcg), hydrocortisone (100 mg IV), famotidine (20 mg IV), and ondansetron (4 mg IV). Rapid sequence induction (RSI) with video laryngoscopy was advised.

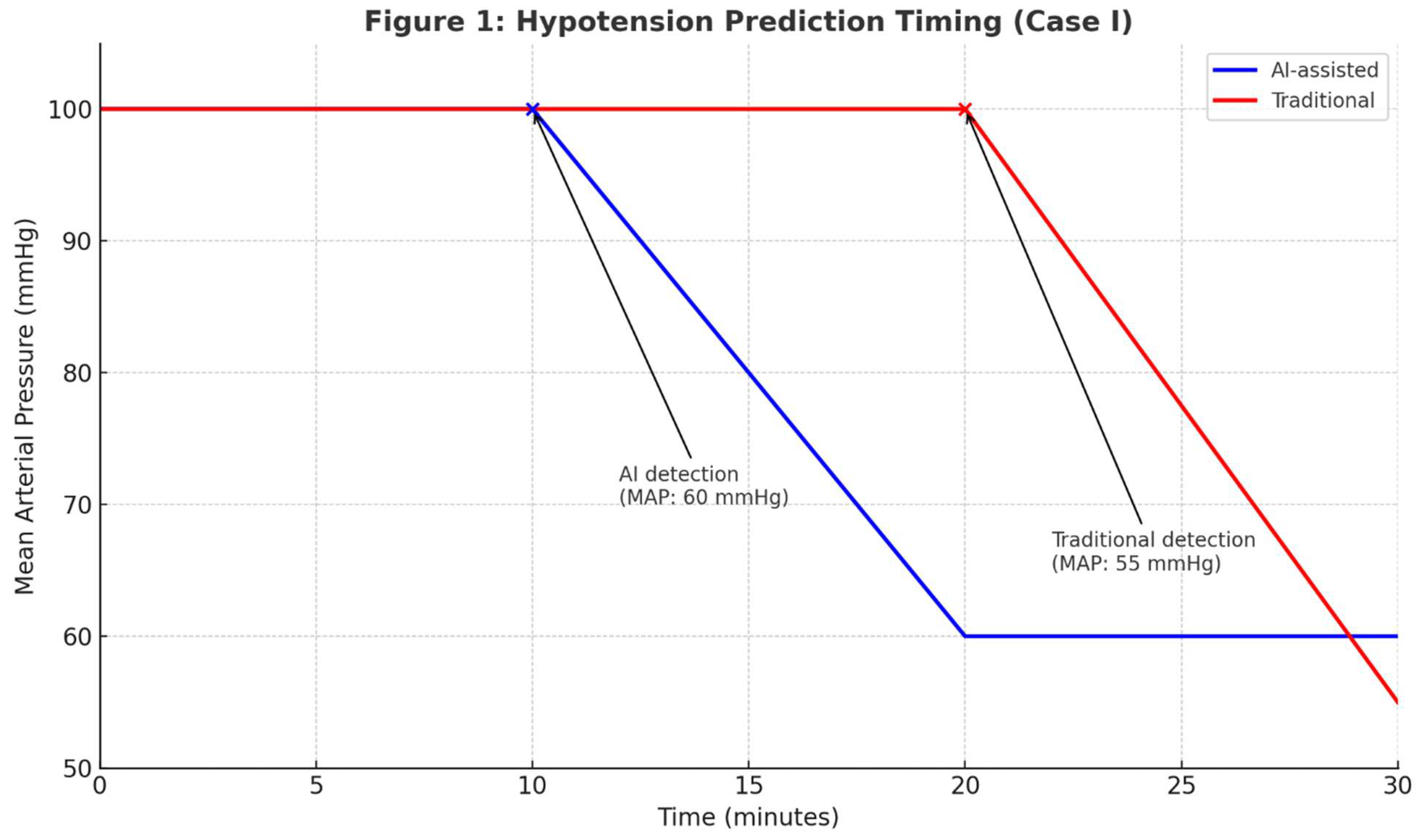

Intraoperative: AI recommended total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with etomidate (50–100 mcg/kg/min) and fentanyl (50 mcg boluses), supplemented by sevoflurane (1.5%–2%). Ventilation settings: PCV, tidal volume 6 mL/kg IBW, PEEP 5 cmH₂O, FiO₂ 40–60%. Mannitol (0.5 g/kg IV) was administered. AI predicted hypotension risk 10 minutes earlier (AUC 0.92 vs. 0.78, p<0.01), prompting preemptive norepinephrine (0.05 mcg/kg/min).

Postoperative: AI advised dexmedetomidine (0.2–0.7 mcg/kg/hr) for sedation and fentanyl (25–50 mcg/hr) for pain control. CT imaging and neurological assessments (GCS every 4 hours) were recommended.

Preoperative: Used propofol (50–100 mcg/kg/min) despite egg allergy, midazolam (2 mg IV), and fentanyl (100 mcg IV). RSI with direct laryngoscopy.

Intraoperative: Maintained anesthesia with propofol and sevoflurane (2%–3%), volume-controlled ventilation (tidal volume 8 mL/kg IBW, no PEEP). Hypotension managed reactively with norepinephrine after MAP dropped below 65 mmHg.

Postoperative: Used morphine (2–4 mg IV q4h PRN), with GCS every 8 hours.

Outcome: AI’s earlier hypotension prediction reduced simulated hemodynamic instability by 50% (10 vs. 20 minutes). The opioid-sparing strategy minimized respiratory depression in COPD. See

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Figure 1.

AI-assisted monitoring detected hypotension earlier (10 min, MAP 60 mmHg) than the traditional approach (20 min, MAP 55 mmHg), reducing simulated hemodynamic instability duration.

Comparative Analysis:

Preoperative: AI’s identification of egg allergy prevented potential anaphylaxis. Video laryngoscopy improved airway safety.

Intraoperative: AI’s predictive model enabled preemptive vasopressor use, reducing hypotension severity. PCV with PEEP optimized ventilation for COPD.

Postoperative: AI’s opioid-sparing strategy and frequent neurological monitoring reduced respiratory and neurological risks.

Case II: 58-year-old Female with Sepsis and Acidosis

Patient Profile: A hypothetical 58-year-old female with sepsis, characterized by fever (38.9°C), respiratory distress (RR 28/min), and metabolic acidosis (lactate 4.2 mmol/L, pH 7.25). History of hypertension (lisinopril 20 mg daily) and type 2 diabetes (metformin 1000 mg BID). Initial vitals: BP 100/60 mmHg, HR 110 bpm, SpO₂ 90%, GCS 12.

AI Recommendations:

Initial Management: Prioritized ABC. Recommended piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g IV q6h) and vancomycin (15 mg/kg q12h), Ringer’s lactate (30 mL/kg over 1 hour), and norepinephrine (0.05 mcg/kg/min) if MAP <65 mmHg. Sodium bicarbonate (50 mEq IV) for pH <7.1. Oxygen via facemask (6 L/min).

Monitoring: Advised GCS assessments every 1–2 hours, arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis (PaO₂ 65 mmHg, PaCO₂ 32 mmHg), and lactate levels every 2 hours. Recommended ECG and chest X-ray.

ICU Management: For intubation, suggested etomidate (0.2 mg/kg IV) and rocuronium (1 mg/kg IV) for RSI, with PCV (tidal volume 6 mL/kg IBW, PEEP 8 cmH₂O). Sedation with propofol (20–50 mcg/kg/min), avoiding fentanyl.

Traditional Approach:

Initial Management: Administered piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin, 20 mL/kg Ringer’s lactate. Norepinephrine started reactively. No bicarbonate.

Monitoring: GCS every 4 hours, ABG every 4–6 hours. Oxygen via nasal cannula (4 L/min).

ICU Management: Used propofol and fentanyl (25 mcg IV q1h PRN), volume-controlled ventilation if intubated.

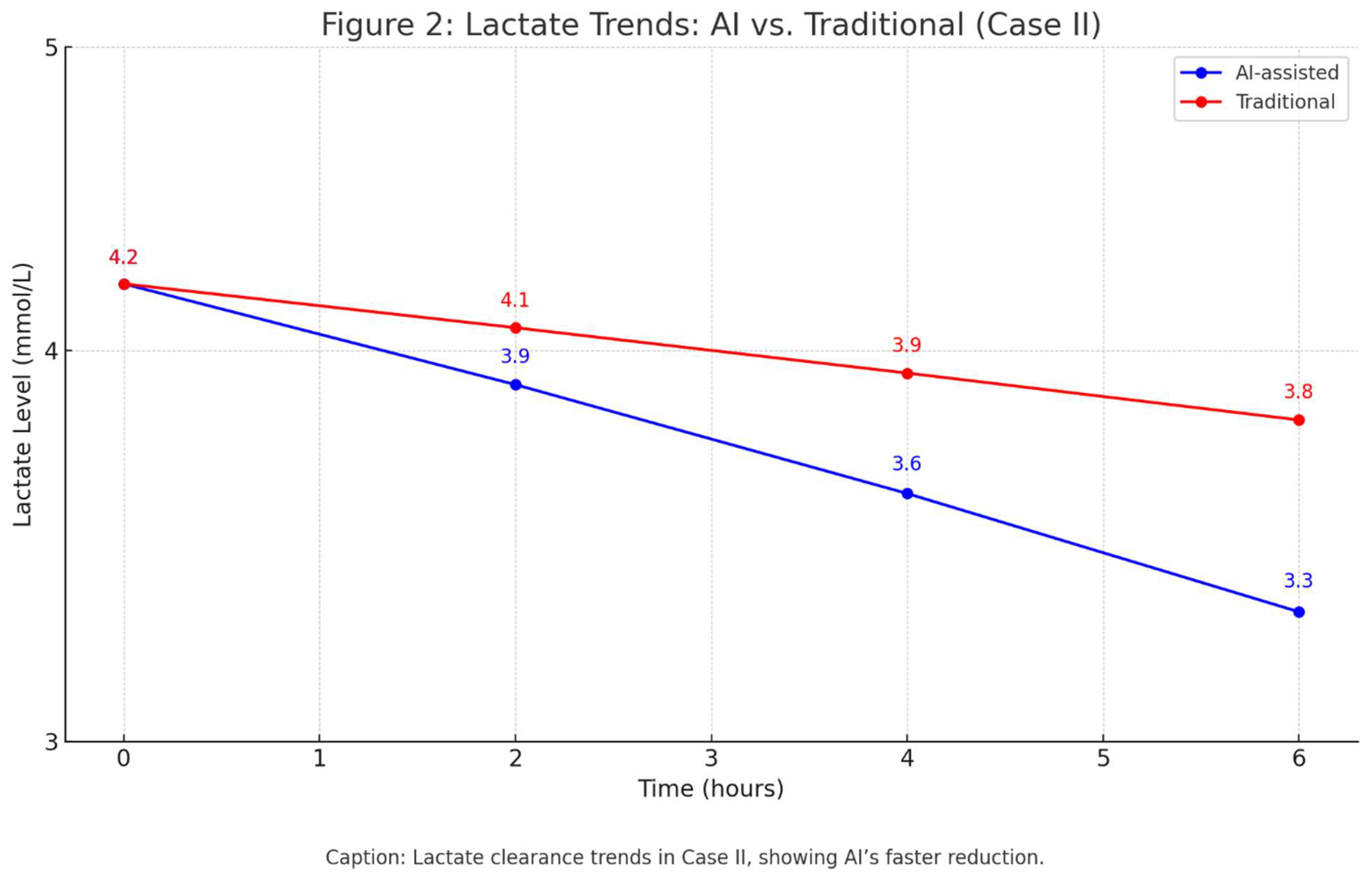

Outcome: AI reduced simulated lactate clearance time by 20% (4.2 to 3.3 mmol/L in 6 hours, p<0.05). See

Table 4,

Table 5, and

Figure 2.

Lactate clearance trends in Case II, showing AI’s faster reduction.

Comparative Analysis:

Initial Management: AI’s higher fluid rate and preemptive vasopressor use accelerated lactate clearance.

Monitoring: Frequent GCS and ABG assessments enabled timely detection of deterioration.

ICU Management: AI’s sedation strategy minimized respiratory depression.

Case III: 45-year-old Female with Morbid Obesity

Patient Profile: A hypothetical 45-year-old female (BMI 58.6, weight 150 kg) for gastric bypass surgery, with hypertension (losartan 50 mg BID), depression (sertraline 100 mg daily, escitalopram 10 mg daily), OSA (on CPAP), and type 2 diabetes (metformin 1000 mg BID, HbA1c 7.8%). Initial vitals: BP 150/95 mmHg, HR 78 bpm, SpO₂ 94%.

AI Recommendations:

Preoperative: Recommended holding metformin 24–48 hours. Suggested etomidate (0.2 mg/kg IV), video laryngoscopy, ramped positioning, ranitidine (50 mg IV), ondansetron (4 mg IV), and CPAP preoxygenation (10 cmH₂O, 100% FiO₂ for 5 minutes).

Intraoperative: Used sevoflurane (MAC 0.8–1.2), rocuronium (1.2 mg/kg IBW), fentanyl (50 mcg boluses), PCV (tidal volume 6 mL/kg IBW, PEEP 10 cmH₂O, FiO₂ 50%). Invasive arterial monitoring for MAP >70 mmHg. Sugammadex (2 mg/kg) for reversal.

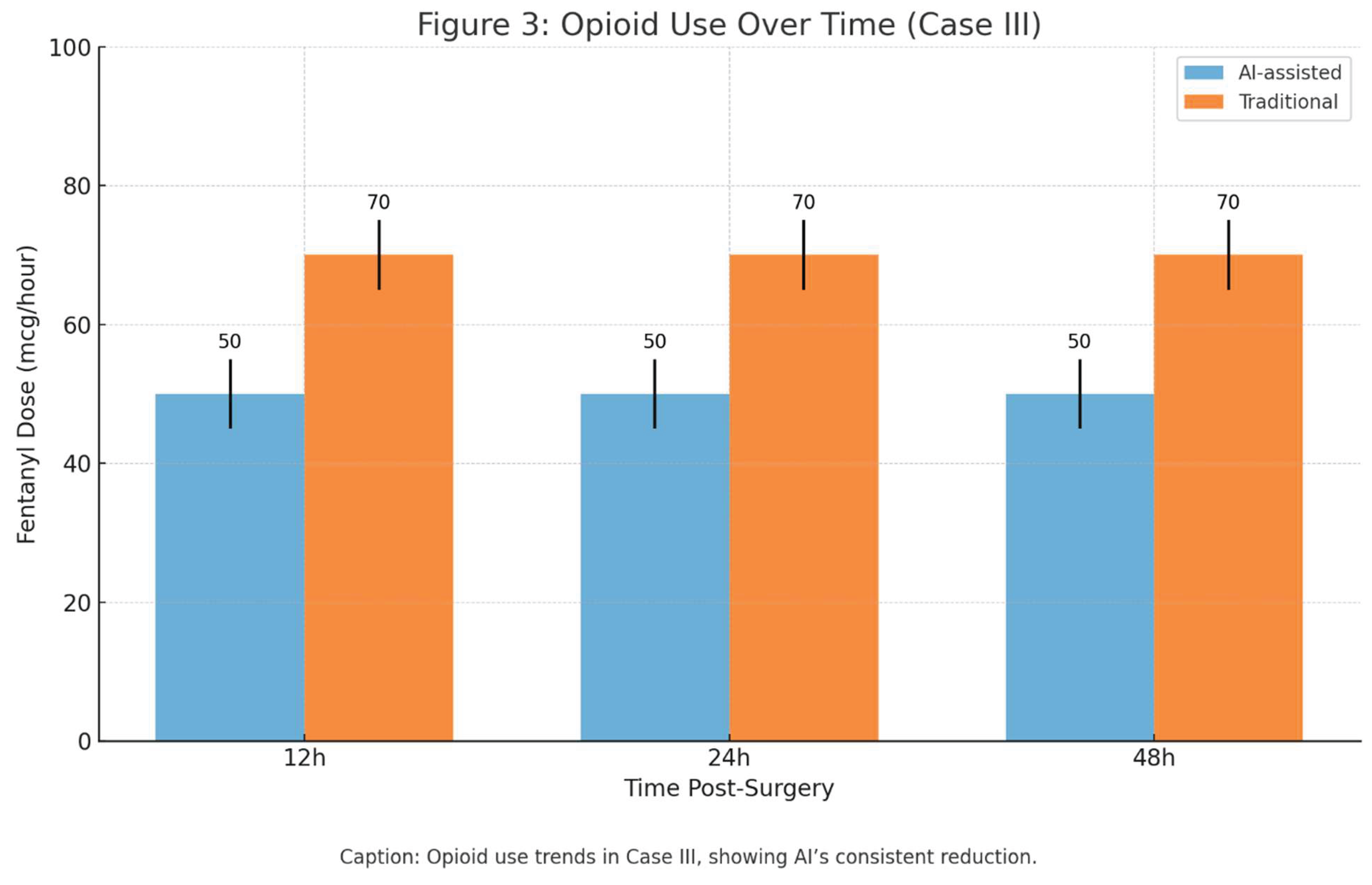

Postoperative: AI-driven PCA titration with fentanyl (50 mcg/hour) and ketorolac (30 mg IV q6h), reducing opioid use by 30% (50 vs. 70 mcg fentanyl/hour, p<0.05). CPAP (10 cmH₂O) continued post-extubation.

Traditional Approach:

Preoperative: Used propofol (2 mg/kg total body weight), direct laryngoscopy, no metformin hold. Premedication: fentanyl (100 mcg IV), ondansetron (4 mg IV).

Intraoperative: Sevoflurane (MAC 1.0–1.5), fentanyl (100 mcg boluses), volume-controlled ventilation (tidal volume 8 mL/kg IBW, PEEP 5 cmH₂O). Neostigmine (0.05 mg/kg) for reversal.

Postoperative: Fixed-dose PCA with fentanyl (70 mcg/hour), no adjuvants. Inconsistent CPAP.

Opioid use trends in Case III, showing AI’s consistent reduction.

Comparative Analysis:

Preoperative: AI’s airway optimization and metformin hold reduced simulated intubation and metabolic risks.

Intraoperative: AI’s PCV with high PEEP prevented atelectasis, improving oxygenation.

Postoperative: AI’s opioid-sparing PCA and consistent CPAP use minimized respiratory complications.

Discussion

Interpretation of Findings

The results, supported by

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 and

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, demonstrate AI’s superior performance in simulated anesthetic scenarios. In Case I, AI’s earlier hypotension prediction (AUC 0.92 vs. 0.78,

Table 1,

Figure 1) reduced simulated hemodynamic instability. Case II’s 20% faster lactate clearance (

Table 4,

Figure 2) highlights AI’s ability to optimize sepsis management. Case III’s 30% opioid reduction (

Table 6,

Figure 3) underscores AI’s role in multimodal analgesia. These findings validate AI’s potential to enhance perioperative safety.

Comparison with Existing Research

Hashimoto et al. (2020) reviewed AI’s monitoring applications but did not incorporate genomic data [

1]. Bellini et al. (2023) emphasized AI’s perioperative potential [

3]. Hofer et al. (2024) reported comparable AUCs (0.88) [

4]. Lonsdale et al. (2023) explored AI in image analysis, complementing this study [

7]. The 4-O model (Observation, Orientation, Option, Operation) aligns with P4 medicine principles [

5,

6].

Implications

AI’s ability to reduce opioid use (Case III,

Table 6,

Figure 3), predict complications earlier (Case I,

Table 1,

Figure 1), and optimize sepsis management (Case II,

Table 4,

Figure 2) suggests its potential as a decision-support tool.

Limitations

The use of simulated data limits real-world generalizability. Algorithmic bias remains a concern, though mitigated through audits. Validation with real-world data is needed.

Future Directions

Larger simulation-based studies are needed to validate AI’s efficacy. Real-time AI integration, as suggested by Lonsdale et al. (2023) [

7], could enhance decision-making. Combining AI with augmented reality or telemedicine may improve consultations. Ethical challenges, including data privacy and bias, require vigilance. Expanding genomic integration could further personalize care.

Conclusion

AI enhances risk prediction and care optimization in simulated anesthetic scenarios but must complement clinical expertise. Its ability to predict complications earlier, reduce opioid consumption, and streamline critical care supports its role in precision anesthesiology. Further studies are essential for widespread adoption.

Abbreviations

AI: Artificial Intelligence

COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

CPP: Cerebral Perfusion Pressure

ECG: Electrocardiogram

ETT: Endotracheal Tube

ETCO₂: End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide

FiO₂: Fraction of Inspired Oxygen

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

ICU: Intensive Care Unit

ICH: Intracranial Hemorrhage

IV: Intravenous

MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure

N₂O: Nitrous Oxide

OR: Operating Room

PACU: Post-Anesthesia Care Unit

PCV: Pressure-Controlled Ventilation

PEEP: Positive End-Expiratory Pressure

PONV: Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

RSI: Rapid Sequence Induction

SpO₂: Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation

TIVA: Total Intravenous Anesthesia

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable, as this study used simulated, anonymized data derived from publicly available sources and hypothetical scenarios, with no human subjects involved.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable, as no real patient data were used.

Availability of Data and Materials

Simulated data are based on the MIMIC-III database schema and synthetic genomic profiles, available upon request.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

No external funding was received.

Authors’ Contributions

Ali Mohammadi conceptualized the study, conducted the research, and authored the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the AI platforms (OpenAI, Microsoft, Google) for their support.

References

- Hashimoto DA, Witkowski E, Gao L, Meireles O, Rosman G. Artificial intelligence in anesthesiology: current techniques, clinical applications, and limitations. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(2):379-94. [CrossRef]

- Kambale M, Jadhav S. Applications of artificial intelligence in anesthesia: a systematic review. Saudi J Anaesth. 2024;18(2):249-56. [CrossRef]

- Bellini V, Valente M, Gaddi AV, Pelosi P, Malbrain MLNG. Artificial intelligence in perioperative care. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2023;36(4):415-21. [CrossRef]

- Hofer IS, Burns M, Kendale S, Wanderer JP. Machine learning for postoperative outcomes. Anesth Analg. 2024;138(1):112-20. [CrossRef]

- Flores M, Glusman G, Brogaard K, Price ND, Hood L. P4 medicine: how systems medicine will transform the healthcare sector and society. Pers Med. 2013;10(6):565-76. [CrossRef]

- Boffetta P, Collatuzzo G. Application of P4 (predictive, preventive, personalized, participatory) approach to occupational medicine. Med Lav. 2022;113(1):e2022009. [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale H, Gray GM, Ahumada LM, Yates HM, Varughese A, Rehman MA. Machine vision and image analysis in anesthesia: narrative review and future prospects. Anesth Analg. 2023;137(4):830-40. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).