Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

African swine fever (ASF) has had a devastating impact on Vietnam’s swine industry since its emergence in 2019, leading to the culling of six million pigs. This paper aimed to review the epidemiological dynamics of ASF in Vietnam and measures applied to control the disease. ASF progressed through an initial epidemic phase (2019-2020) and has transitioned into a more endemic phase (2021-2024). The disease spread rapidly during the epidemic phase, driven by human-mediated transmission routes and inadequate biosecurity practices, particularly on smallholder farms. To control ASF, the Vietnamese government endorsed a national control plan including biosecurity enhancements, disease surveillance, establishing ASF-free compartments, developing ASF vaccines, and strengthening the capacity of veterinary services. While these measures have helped reduce the number of outbreaks, challenges persist, including the emergence of recombinant ASF strains, limited vaccine adoption, and gaps in veterinary infrastructure. ASF has substantially changed Vietnam’s swine industry, shifting toward reducing small-scale household farming and increasing professional households and large-scale farms. As ASF has transitioned into an endemic phase, sustainable strategies focusing on continuous monitoring, improved vaccination coverage, and education programs are essential to mitigate its impacts and ensure the resilience of Vietnam’s swine industry.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Source and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Overview of the Epidemiological Situation of ASF in Vietnam

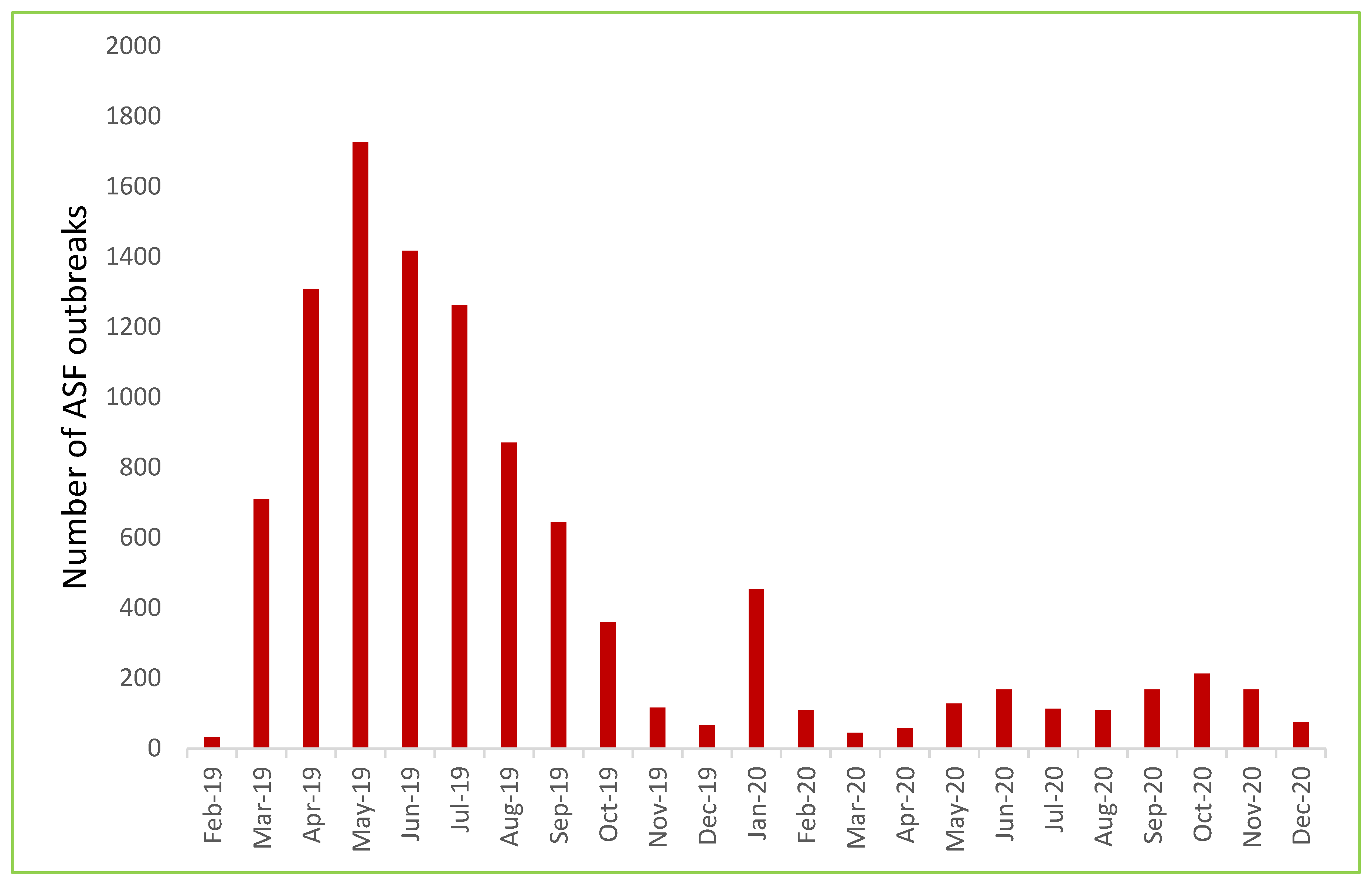

3.1. Initial Introduction and Epidemic Situation (February 2019-December 2020)

3.2. The Second Phase of the Outbreak: From Epidemic to Endemic Stage (January 2021 to December 2023)

3.3. Current Situation of ASF in Vietnam (2024)

4. Transmission Dynamics and Epidemiological Factors Affecting Disease Spread

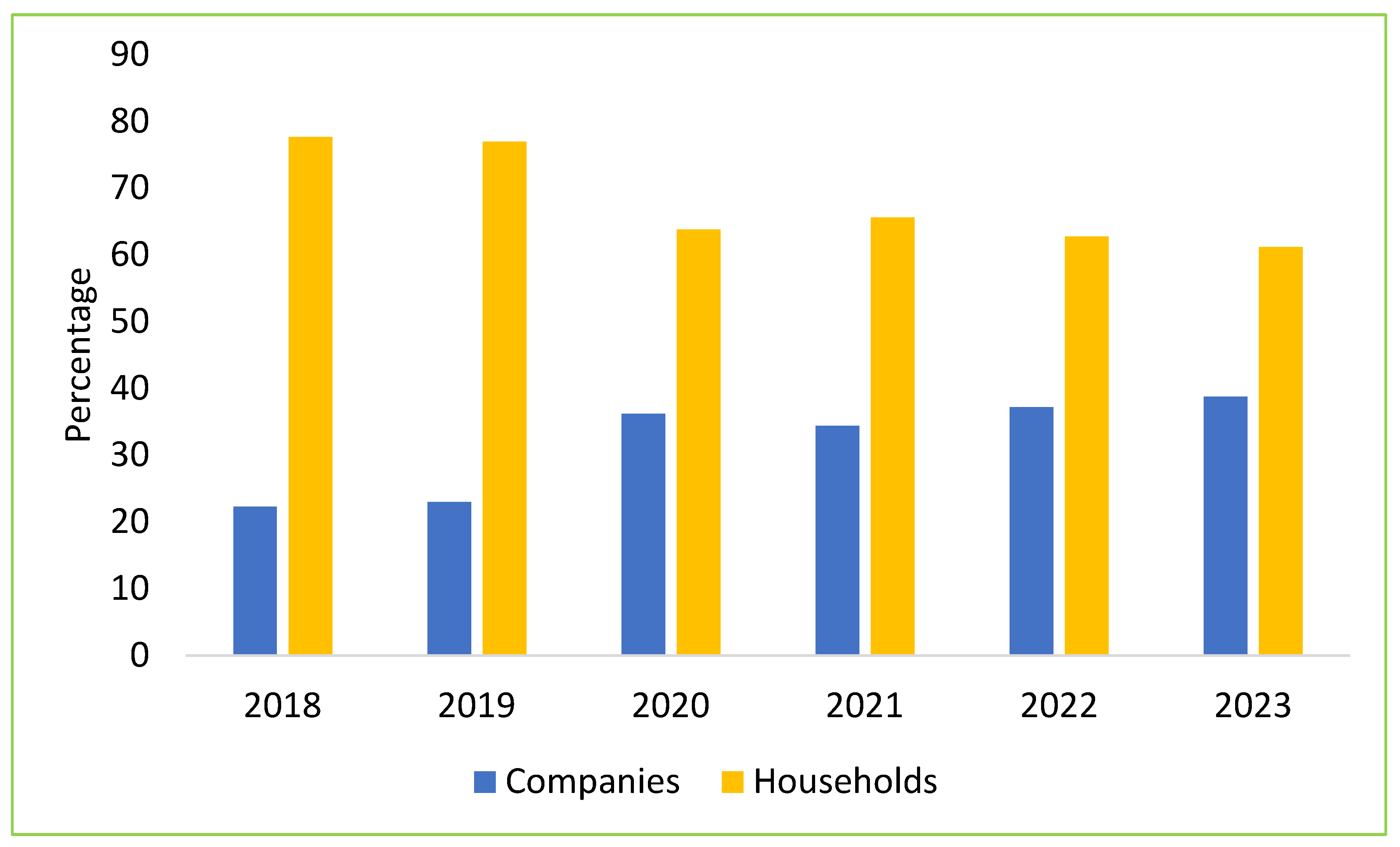

5. Impact of ASF on the Structure of Vietnam’s Swine Industry

6. Strategies Implemented to Mitigate the Impacts of ASF

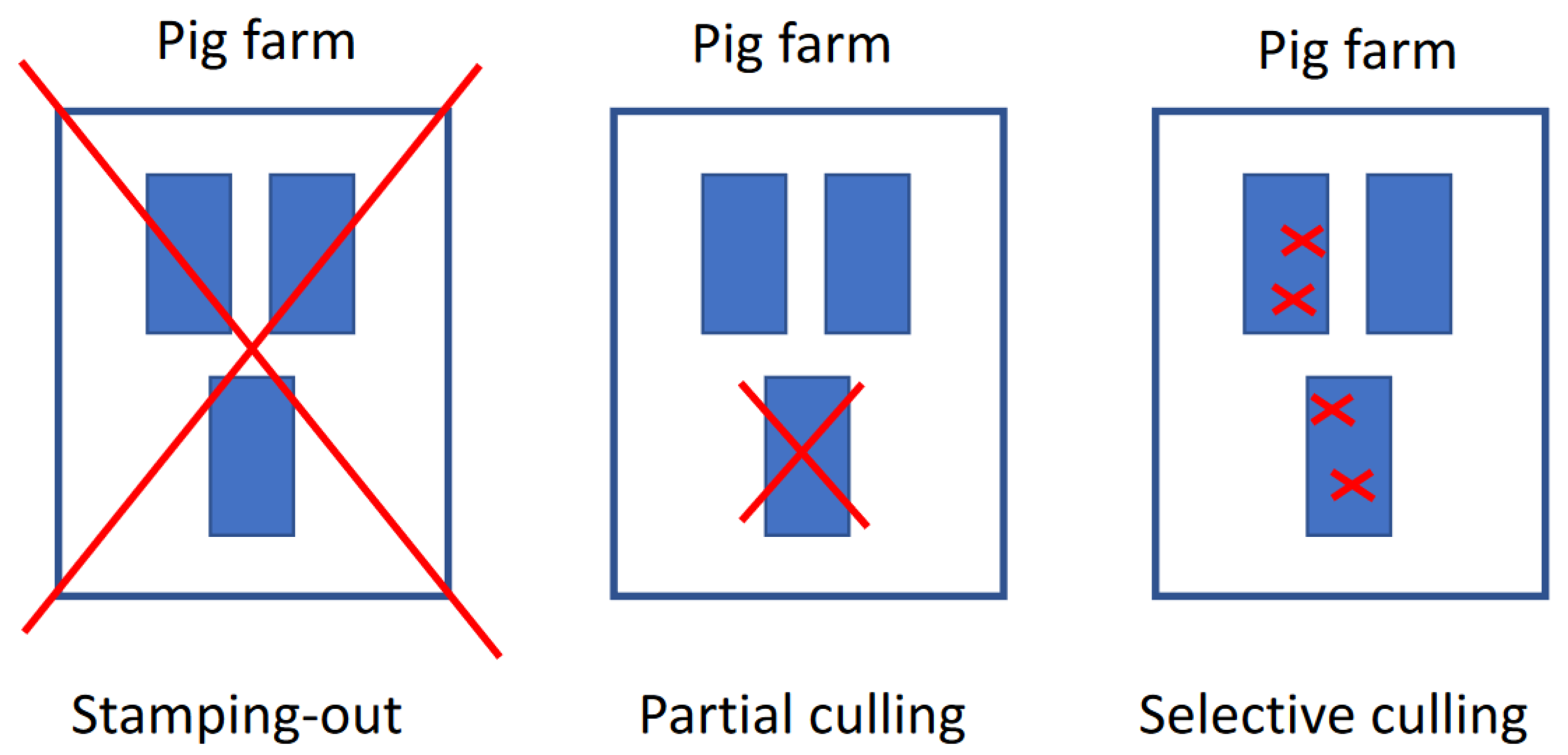

6.1. Initial Response to ASF

6.2. Ongoing Management of ASF

6.3. Vaccine Development and Use in Vietnam

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quembo, C.J.; Jori, F.; Vosloo, W.; Heath, L. Genetic Characterization of African Swine Fever Virus Isolates from Soft Ticks at the Wildlife/Domestic Interface in Mozambique and Identification of a Novel Genotype. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, M.; De la Torre, A.; Dixon, L.; Gallardo, C.; Jori, F.; Laddomada, A.; Martins, C.; Parkhouse, R.M.; Revilla, Y.; Rodriguez, F. and J.-M.; et al. Approaches and Perspectives for Development of African Swine Fever Virus Vaccines. Vaccines 2017, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, A.D.S.; Penrith, M.-L.; Crucière, C.; Edrich, J.L.; Hutchings, G.; Roger, F.; Couacy-Hymann, E.; R. Thomson, G. Genotyping Field Strains of African Swine Fever Virus by Partial P72 Gene Characterisation. Arch. Virol. 2003, 148, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, C.; Reis, A.L.; Kalema-Zikusoka, G.; Malta, J.; Soler, A.; Blanco, E.; Parkhouse, R.M.E.; Leitão, A. Recombinant Antigen Targets for Serodiagnosis of African Swine Fever. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.R.; Bevins, S.N. A Review of African Swine Fever and the Potential for Introduction into the United States and the Possibility of Subsequent Establishment in Feral Swine and Native Ticks. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrage, T.G. African Swine Fever Virus Infection in Ornithodoros Ticks. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.K.; Sun, H.; Roberts, H. African Swine Fever. Antiviral Res. 2019, 165, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costard, S.; Wieland, B.; de Glanville, W.; Jori, F.; Rowlands, R.; Vosloo, W.; Roger, F.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Dixon, L.K. African Swine Fever: How Can Global Spread Be Prevented? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costard, S.; Mur, L.; Lubroth, J.; Sanchez-Vizcaino, J.M.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Epidemiology of African Swine Fever Virus. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.C.; Le, H.N.T.; Nga, B.T.T.; Do, D.T. Facing the Challenges of Endemic African Swine Fever in Vietnam. CABI Rev. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, S.; Gabriel, C.; Beer, M. Pathogenesis of African Swine Fever in Domestic Pigs and European Wild Boar. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- African Swine Fever - WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. Available online: https://www.woah.org/en/disease/african-swine-fever/#ui-id-2 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Li, X.; Tian, K. African Swine Fever in China. Vet. Rec. 2018, 183, 300–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Li, N.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Miao, F.; Chen, T.; Zhang, S.; Cao, P.; Li, X.; Tian, K.; et al. Emergence of African Swine Fever in China, 2018. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 1482–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASF Situation in Asia & Pacific Update. Available online: https://www.fao.org/animal-health/situation-updates/asf-in-asia-pacific/en (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Bui, N.; Gilleski, S. Vietnam African Swine Fever Update; United States Department of Agriculture: Hanoi, 2020; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, N. Vietnam African Swine Fever Update; United States Department of Agriculture: Hanoi, 2021; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Le, V.P.; Nguyen, V.T.; Le, T.B.; Mai, N.T.A.; Nguyen, V.D.; Than, T.T.; Lai, T.N.H.; Cho, K.H.; Hong, S.-K.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. Detection of Recombinant African Swine Fever Virus Strains of P72 Genotypes I and II in Domestic Pigs, Vietnam, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blome, S.; Franzke, K.; Beer, M. African Swine Fever – A Review of Current Knowledge. Virus Res. 2020, 287, 198099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, V.P.; Jeong, D.G.; Yoon, S.-W.; Kwon, H.-M.; Trinh, T.B.N.; Nguyen, T.L.; Bui, T.T.N.; Oh, J.; Kim, J.B.; Cheong, K.M.; et al. Outbreak of African Swine Fever, Vietnam, 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1433–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Thakur, K.K.; Bui, V.N.; Pham, T.L.; Bui, A.N.; Dao, T.D.; Thanh, V.T.; Wieland, B. A Stochastic Simulation Model of African Swine Fever Transmission in Domestic Pig Farms in the Red River Delta Region in Vietnam. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mighell, E.; Ward, M.P. African Swine Fever Spread across Asia, 2018-2019. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 2722–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Q.; Li, R.; Han, Y.; Han, D.; Qiu, J. Temporal and Spatial Evolution of the African Swine Fever Epidemic in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Ngoc Que; Pham Thi Ngoc Linh; Tran Cong Thang; Nguyen Thi Thuy; Nguyen Thi Thinh; Karl M. Rich; Hung Nguyen-Viet Economic Impacts of African Swine Fever in Vietnam Available online:. Available online: https://www.ilri.org/knowledge/publications/economic-impacts-african-swine-fever-vietnam (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Lee, H.S.; Thakur, K.K.; Pham-Thanh, L.; Dao, T.D.; Bui, A.N.; Bui, V.N.; Quang, H.N. A Stochastic Network-Based Model to Simulate Farm-Level Transmission of African Swine Fever Virus in Vietnam. PloS One 2021, 16, e0247770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, B.T.T.; Tran Anh Dao, B.; Nguyen Thi, L.; Osaki, M.; Kawashima, K.; Song, D.; Salguero, F.J.; Le, V.P. Clinical and Pathological Study of the First Outbreak Cases of African Swine Fever in Vietnam, 2019. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hop Q., Nguyen; Duyen M. T., Nguyen; Nam M., Nguyen; Dung N. T., Nguyen; Han Q. T., Luu; Duy, T. Do Genetic Analysis of African Swine Fever Virus Based on Major Genes Encoding P72, P54 and P30. J. Agric. Dev. 2021, 20, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, M.T.; Thi My Le, H.; Xuan Dang, V.; Thi Bich Ngoc, T.; Phan, L.V.; Thi Hoa, N.; Quang Lam, T.; Thi Lan, N.; Notsu, K.; Sekiguchi, S.; et al. Development of a Highly Sensitive Point-of-Care Test for African Swine Fever That Combines EZ-Fast DNA Extraction with LAMP Detection: Evaluation Using Naturally Infected Swine Whole Blood Samples from Vietnam. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.N.; Ngo, T.T.N.; Nguyen, D.M.T.; Lai, D.C.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Lee, J.Y.; Nguyen, T.T.; Do, D.T. Genetic Characterization of African Swine Fever Virus in Various Outbreaks in Central and Southern Vietnam During 2019-2021. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.T.T.; Truong, A.D.; Dang, A.K.; Ly, D.V.; Nguyen, C.T.; Chu, N.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Dang, H.V. Genetic Characterization of African Swine Fever Viruses Circulating in North Central Region of Vietnam. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1697–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietnam Department of Animal Health. Available online: https://vahis.vn/home/login.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Quang Minh Phan; Nguyen Van Long; Nguyen Thi Diep Report at the Conference on Animal Disease Prevention and Control, Slaughterhouse Management, and Ensuring Food Safety during the Tết Ất Tỵ 2025. Presented at the Hội nghị phòng, chống dịch bệnh động vật và kiểm soát giết mổ, bảo đảm an toàn thực phẩm dịp Tết Nguyên đán Ất Tỵ năm 2025, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2025.

- Mai, N.T.; Tuyen, L.A.; Van Truong, L.; Huynh, L.T.M.; Huong, P.T.L.; Hanh, V.D.; Anh, V.V.; Hoa, N.X.; Vui, T.Q.; Sekiguchi, S. Early-Phase Risk Assessments during the First Epidemic Year of African Swine Fever Outbreaks in Vietnamese Pigs. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 1993–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Dao, T.D.; Huyen, L.T.T.; Bui, V.N.; Bui, A.N.; Ngo, D.T.; Pham, U.B. Spatiotemporal Analysis and Assessment of Risk Factors in Transmission of African Swine Fever Along the Major Pig Value Chain in Lao Cai Province, Vietnam. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 853825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, L.; Thuy, N.N.; Beaulieu, A.; Hanh, T.M.D.; Anh, H.H. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Swine Farmers Related to Livestock Biosecurity: A Case Study of African Swine Fever in Vietnam. J. Agric. Sci. – Sri Lanka 2023, 18, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.D.; Nguyen, L.T.; Isoda, N.; Sakoda, Y.; Hoang, L.T.; Stevenson, M.A. Descriptive Epidemiology and Spatial Analysis of African Swine Fever Epidemics in Can Tho, Vietnam, 2019. Prev. Vet. Med. 2023, 211, 105819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, T.N.; Sekiguchi, S.; Huynh, T.M.L.; Cao, T.B.P.; Le, V.P.; Dong, V.H.; Vu, V.A.; Wiratsudakul, A. Dynamic Models of Within-Herd Transmission and Recommendation for Vaccination Coverage Requirement in the Case of African Swine Fever in Vietnam. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, N.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Vu, V.A.; Vu, T.N.; Huynh, T.M.L. Estimation of the Herd-Level Basic Reproduction Number for African Swine Fever in Vietnam, 2019. Vet. World 2022, 15, 2850–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, N.T.A.; Trinh, T.B.N.; Nguyen, V.T.; Lai, T.N.H.; Le, N.P.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Ambagala, A.; Do, D.L.; Le, V.P. Estimation of Basic Reproduction Number (R0) of African Swine Fever (ASF) in Mid-Size Commercial Pig Farms in Vietnam. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 918438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.-I.; Bui, N.A.; Bui, V.N.; Dao, D.T.; Cho, A.; Lee, H.G.; Jung, Y.-H.; Do, Y.J.; Kim, E.; Bok, E.-Y.; et al. Pathobiological Analysis of African Swine Fever Virus Contact-Exposed Pigs and Estimation of the Basic Reproduction Number of the Virus in Vietnam. Porc. Health Manag. 2023, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.; Nguyen, T.M.; Ngo, T.T.N.; Thinh, D.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Do, L.D.; Do, D.T. Long-Term Follow-up of Convalescent Pigs and Their Offspring after an Outbreak of Acute African Swine Fever in Vietnam. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 3194–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phân tích và dự báo thị trường AgroMonitor. Available online: http://agromonitor.vn/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Phạm Kim Đăng Báo cáo thực trạng chăn nuôi lợn và giải pháp phát triển bền vững trong tình hình mới. Presented at the Hội nghị “Thực trạng phát triển chăn nuôi lợn và giải pháp phát triển bền vững trong tình hình mới,” 2024.

- Nguyen Thi Thuy, M.; Dorny, P.; Lebailly, P.; Le Thi Minh, C.; Nguyen Thi Thu, H.; Dermauw, V. Mapping the Pork Value Chain in Vietnam: A Systematic Review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 2799–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nga, N.T.D.; Hung, P.V.; Vy, L.T.L.; Huyen, N.T.T.; Ha, D.N.; Huong, G. Swine Production and Challenges in Vietnam after African Swine Fever: A Case Study in Peri-Urban Hanoi, Vietnam. Vietnam J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 4, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Thi, T.; Pham-Thi-Ngoc, L.; Nguyen-Ngoc, Q.; Dang-Xuan, S.; Lee, H.S.; Nguyen-Viet, H.; Padungtod, P.; Nguyen-Thu, T.; Nguyen-Thi, T.; Tran-Cong, T.; et al. An Assessment of the Economic Impacts of the 2019 African Swine Fever Outbreaks in Vietnam. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 686038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Le, K.T. The Spatiotemporal Epidemiology of African Swine Fever in the Mekong Delta and the Review of Vaccine Development in Vietnam. J. Vet. Epidemiol. 2023, 27, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woonwong, Y.; Do Tien, D.; Thanawongnuwech, R. The Future of the Pig Industry After the Introduction of African Swine Fever into Asia. Anim. Front. Rev. Mag. Anim. Agric. 2020, 10, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietnam Department of Animal Health Daily Report on Animal Diseases to Minister of MARD;

- Nga, B.T.T.; Auer, A.; Padungtod, P.; Dietze, K.; Globig, A.; Rozstalnyy, A.; Hai, T.M.; Depner, K. Evaluation of Selective Culling as a Containment Strategy for African Swine Fever at a Vietnamese Sow Farm. Pathogens 2024, 13, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nga, B.T.T.; Padungtod, P.; Depner, K.; Chuong, V.D.; Duy, D.T.; Anh, N.D.; Dietze, K. Implications of Partial Culling on African Swine Fever Control Effectiveness in Vietnam. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 957918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borca, M.V.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Silva, E.; Vuono, E.; Rai, A.; Pruitt, S.; Holinka, L.G.; Velazquez-Salinas, L.; Zhu, J.; Gladue, D.P. Development of a Highly Effective African Swine Fever Virus Vaccine by Deletion of the I177L Gene Results in Sterile Immunity against the Current Epidemic Eurasia Strain. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10.1128–jvi.02017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta Hoang Long Summary of Information African Swine Fever Vaccine in Vietnam. 2023.

- Nguyen Van Long; Le Toan Thang; Nguyen Van Diep VIET NAM’S EXPERIENCE ON THE DEPLOYMENT OF ASF VACCINES. Presented at the FAO Consultation Conference on ASF, 2023.

- Chu Duc Huy VIET NAM’S EXPERIENCE ON THE DEPLOYMENT OF ASF VACCINES.

- Nguyen Van Diep CẬP NHẬT TÌNH HÌNH PHÁT TRIỂN, SẢN XUẤT VÀ CUNG ỨNG VẮC XIN DỊCH TẢ LỢN CHÂU PHI AVAC ASF LIVE. Presented at the Hội nghị triển khai các giải pháp phòng, chống dịch bệnh gia súc, gia cầm các tháng cuối năm 2024, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024.

- Truong, Q.L.; Wang, L.; Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Tran, S.D.; Vu, A.T.; Le, A.D.; Nguyen, V.G.; Hoang, P.T.; Nguyen, Y.T.; et al. A Cell-Adapted Live-Attenuated Vaccine Candidate Protects Pigs against the Homologous Strain VNUA-ASFV-05L1, a Representative Strain of the Contemporary Pandemic African Swine Fever Virus. Viruses 2023, 15, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Q.L.; Wang, L.; Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Le, A.D.; Nguyen, G.V.; Vu, A.T.; Hoang, P.T.; Le, T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; et al. A Non-Hemadsorbing Live-Attenuated Virus Vaccine Candidate Protects Pigs against the Contemporary Pandemic Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus. Viruses 2024, 16, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Le, T.T.; Vu, S.D.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Le, M.T.T.; Pham, V.T.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Ho, T.T.; Hoang, H.T.T.; Tran, H.X.; et al. A Plant-Based Oligomeric CD2v Extracellular Domain Antigen Exhibits Equivalent Immunogenicity to the Live Attenuated Vaccine ASFV-G-∆I177L. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. (Berl.) 2024, 213, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos: ASF Vaccine Procurement Underway, Rollout by Midyear Available online:. Available online: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1223224 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Ambagala, A.; Goonewardene, K.; Kanoa, I.E.; Than, T.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Lai, T.N.H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Erdelyan, C.N.G.; Robert, E.; Tailor, N.; et al. Characterization of an African Swine Fever Virus Field Isolate from Vietnam with Deletions in the Left Variable Multigene Family Region. Viruses 2024, 16, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep, N.V.; Duc, N.V.; Ngoc, N.T.; Dang, V.X.; Tiep, T.N.; Nguyen, V.D.; Than, T.T.; Maydaniuk, D.; Goonewardene, K.; Ambagala, A.; et al. Genotype II Live-Attenuated ASFV Vaccine Strains Unable to Completely Protect Pigs against the Emerging Recombinant ASFV Genotype I/II Strain in Vietnam. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duc Hien, N.; Trung Hoang, L.; My Quyen, T.; Phuc Khanh, N.; Thanh Nguyen, L. Molecular Characterization of African Swine Fever Viruses Circulating in Can Tho City, Vietnam. Vet. Med. Int. 2023, 2023, 8992302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Cho, K.-H.; Mai, N.T.A.; Park, J.-Y.; Trinh, T.B.N.; Jang, M.-K.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Vu, X.D.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, V.D.; et al. Multiple Variants of African Swine Fever Virus Circulating in Vietnam. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ganges, L.; Dixon, L.K.; Bu, Z.; Zhao, D.; Truong, Q.L.; Richt, J.A.; Jin, M.; Netherton, C.L.; Benarafa, C.; et al. 2023 International African Swine Fever Workshop: Critical Issues That Need to Be Addressed for ASF Control. Viruses 2023, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Luo, R.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, H.-J. Current Efforts towards Safe and Effective Live Attenuated Vaccines against African Swine Fever: Challenges and Prospects. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SHIC Reports on African Swine Fever Vaccines Approved in Vietnam – Swine Health Information Center Available online:. Available online: https://www.swinehealth.org/shic-reports-on-african-swine-fever/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Global African Swine Fever Research Alliance: Fighting African Swine Fever Together Available online:. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/GARA/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Mulumba-Mfumu, L.K.; Saegerman, C.; Dixon, L.K.; Madimba, K.C.; Kazadi, E.; Mukalakata, N.T.; Oura, C.A.L.; Chenais, E.; Masembe, C.; Ståhl, K.; et al. African Swine Fever: Update on Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1462–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Number of outbreaks | Number of ASF-affected provinces/cities | Number of pigs dead/culled (heads) |

| 2019 | 8,500 | 63/63 | 6,000,000 |

| 2020 | 1,596 | 50/63 | 86,462 |

| 2021 | 3,029 | 59/63 | 279,910 |

| 2022 | 1,229 | 53/63 | 59,000 |

| 2023 | 952 | 46/63 | 44,390 |

| 2024 | 1,669 | 48/63 | 92,707 |

| Total | 16,975 | 6,652,469 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).