Submitted:

01 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Types of Electrohydraulic Actuators

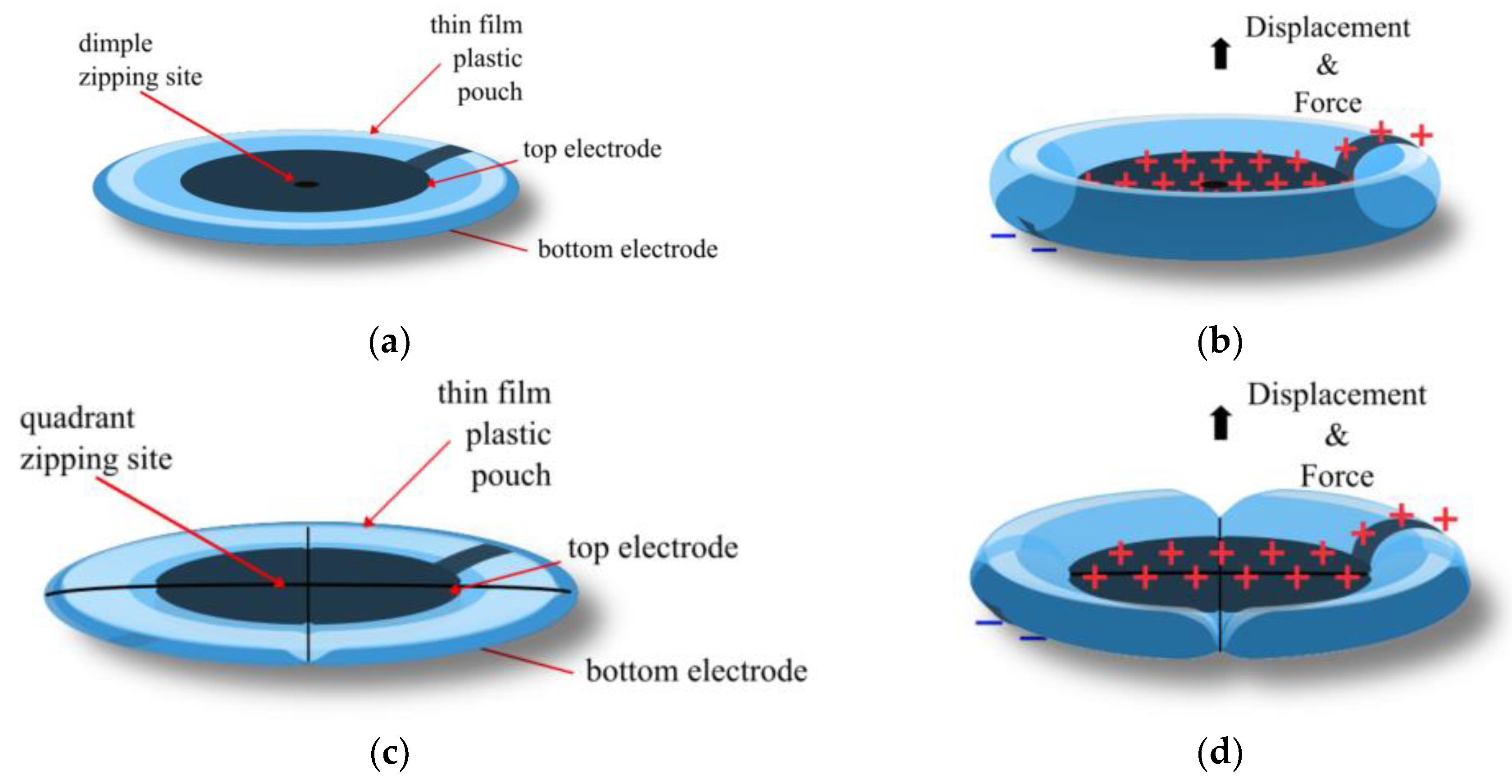

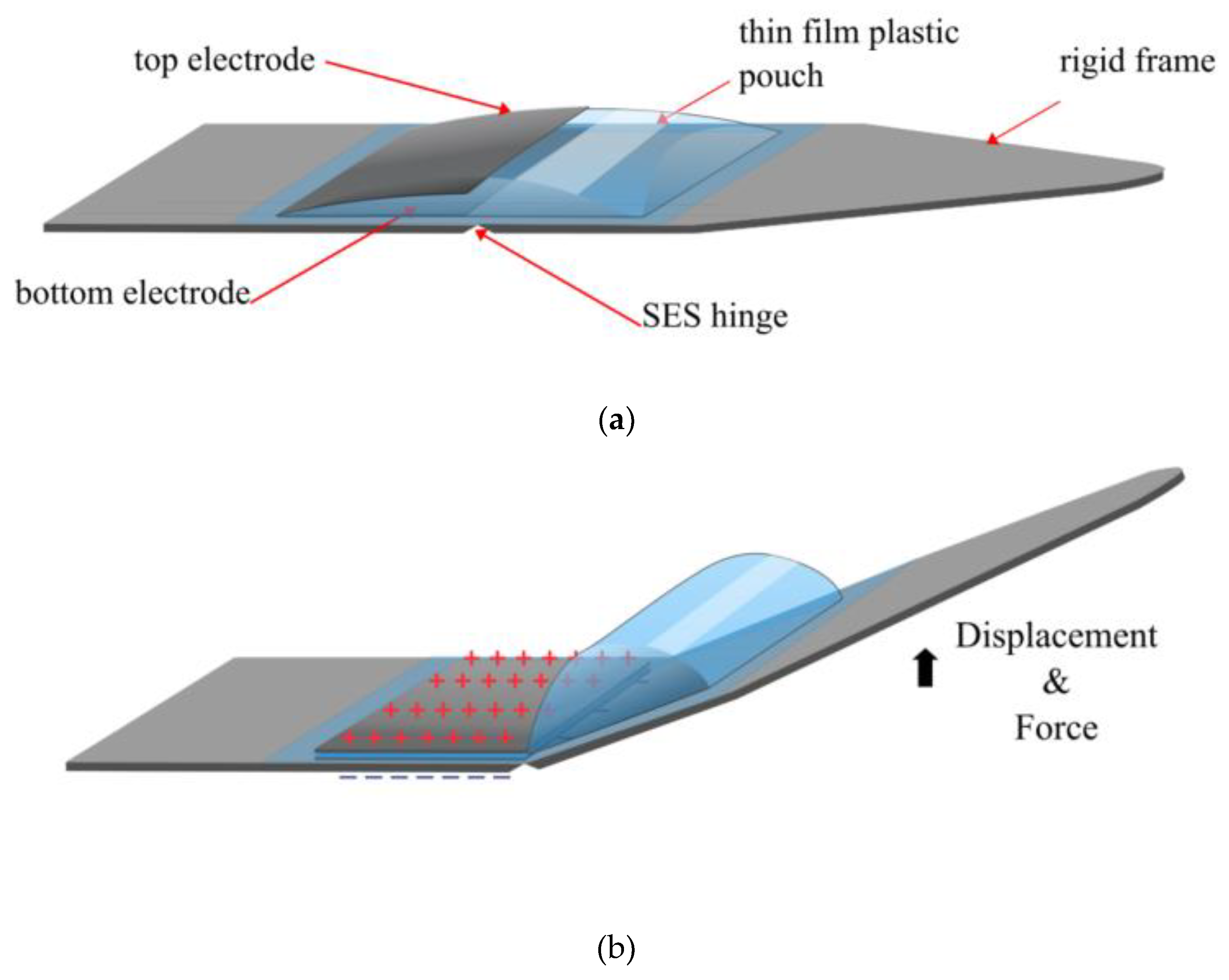

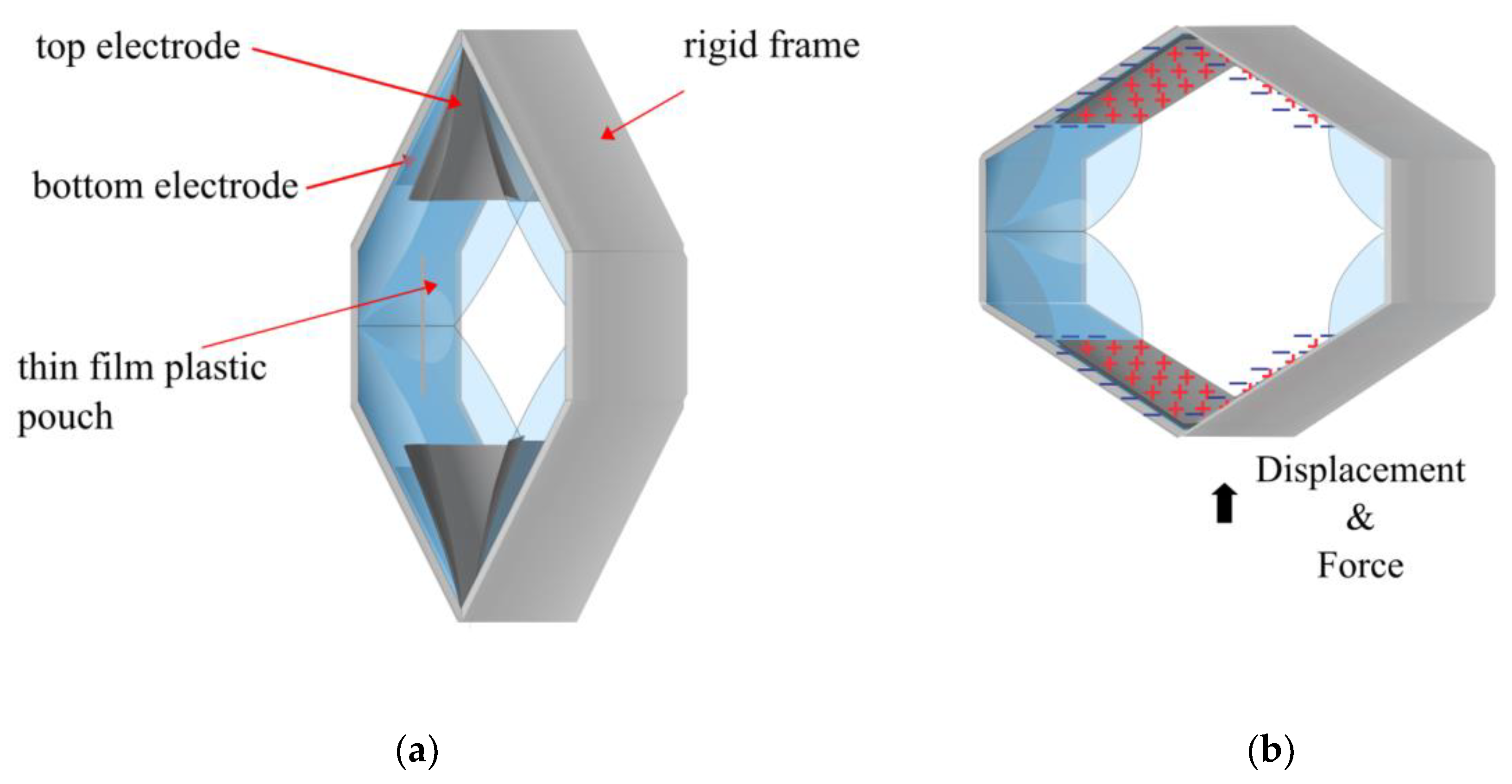

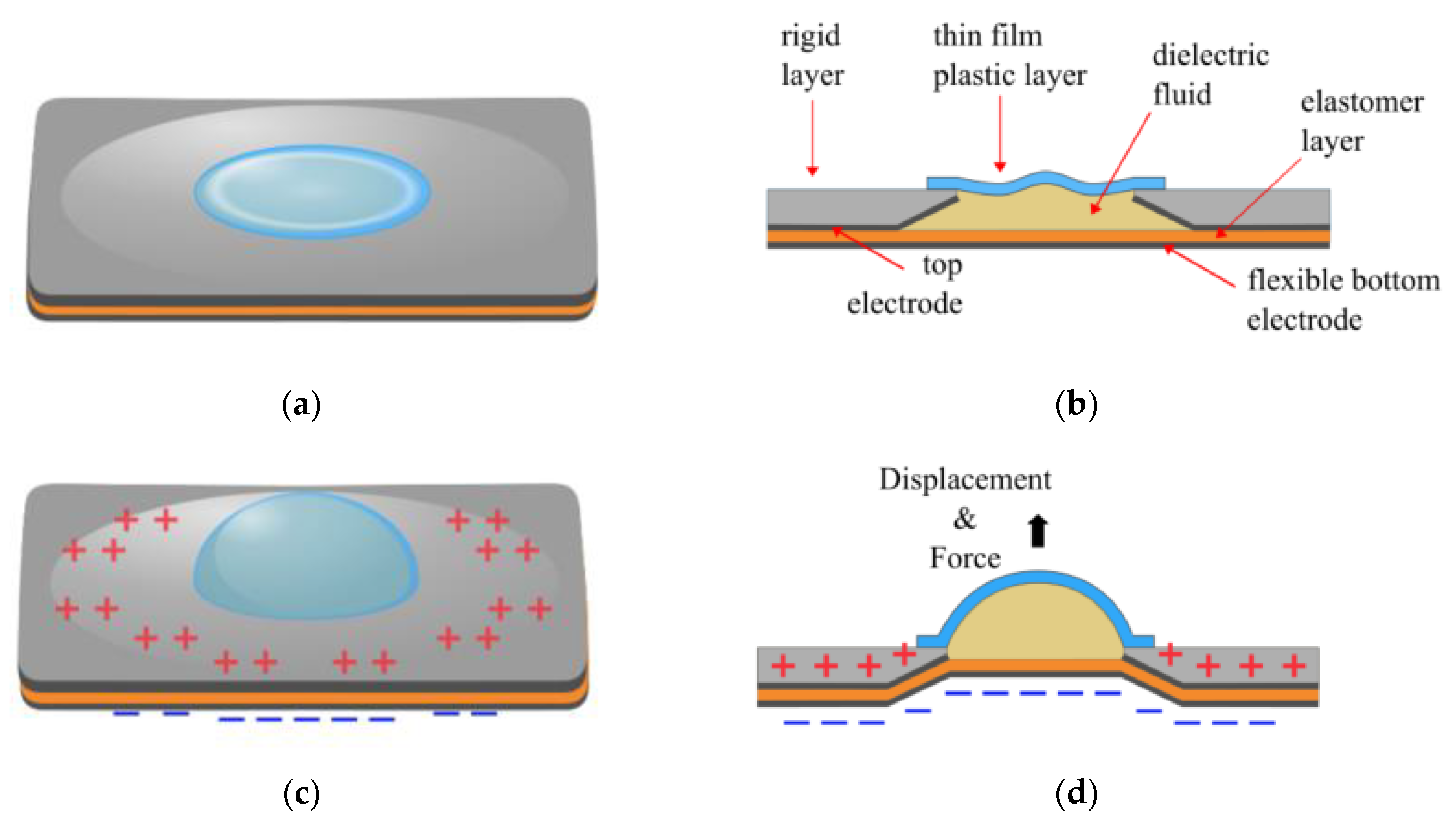

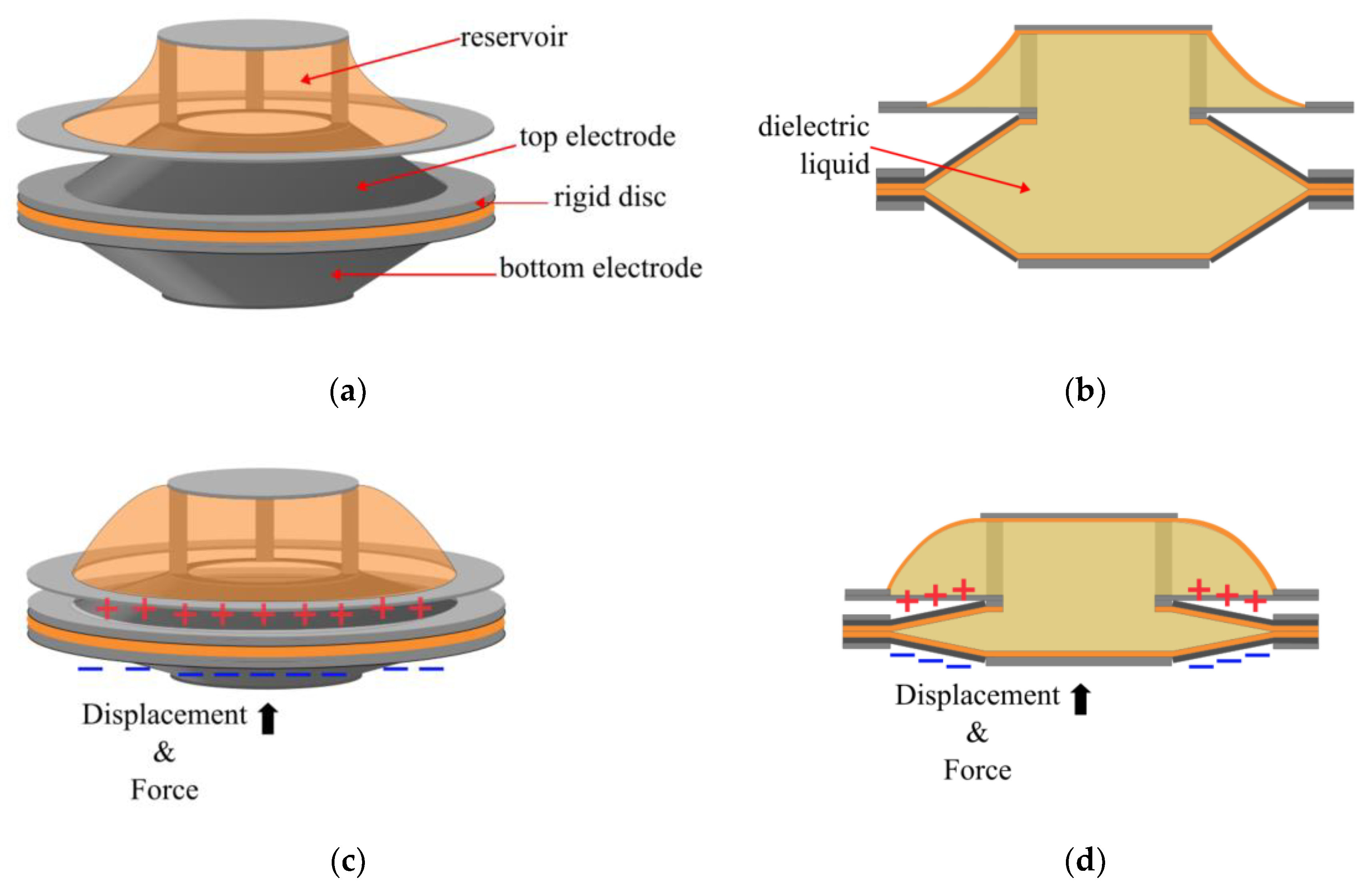

2.1. University of Colorado Boulder, USA

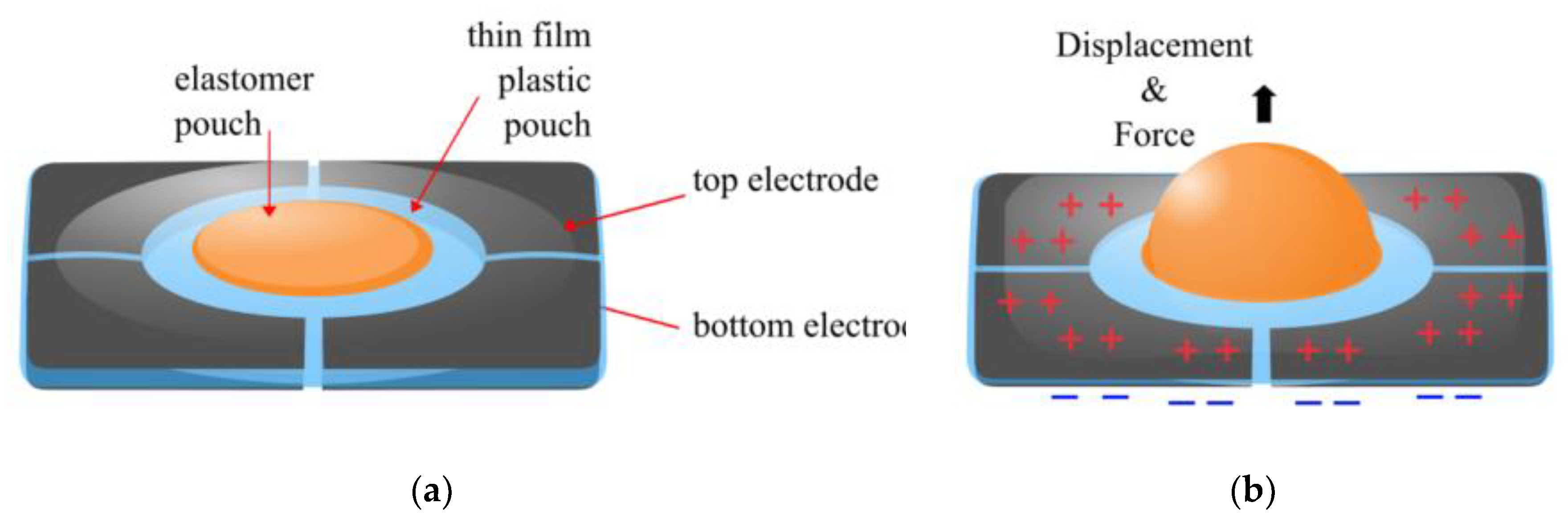

2.2. É. cole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland

2.3. University of Trento, Trento, Italy

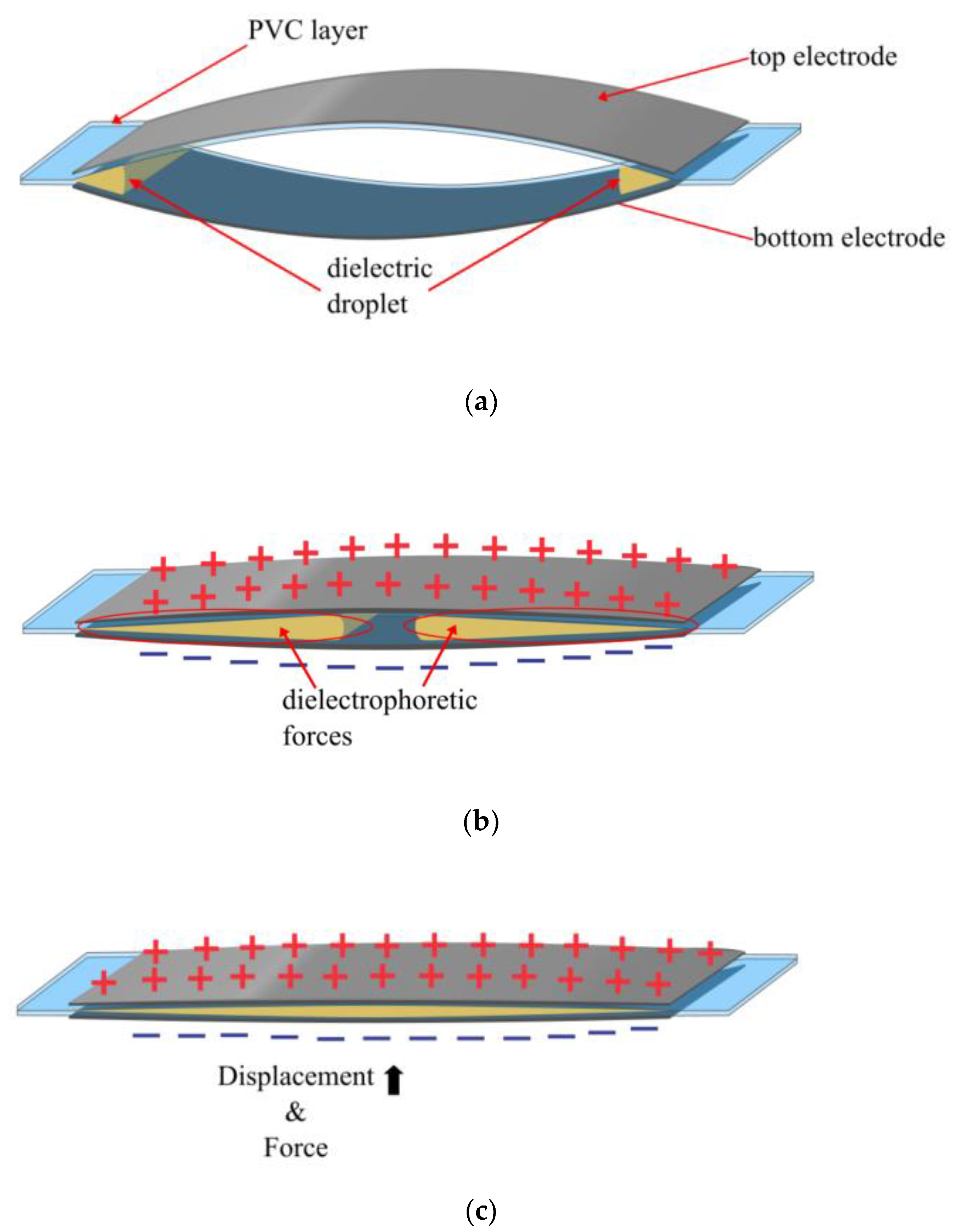

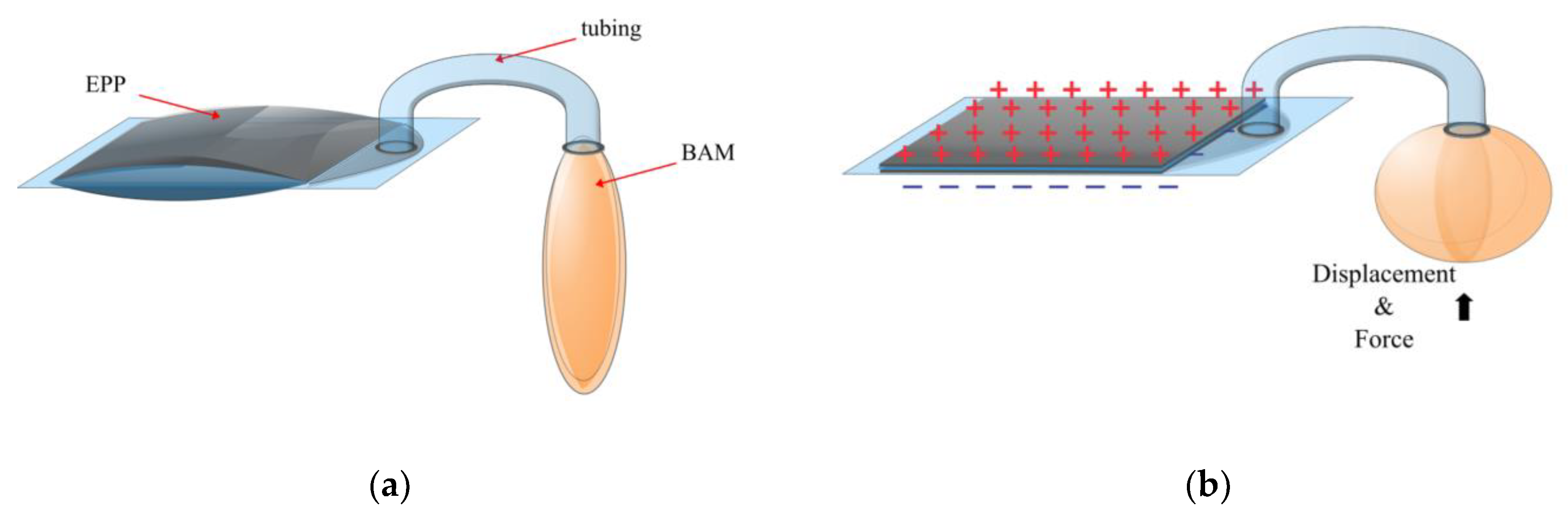

2.4. University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

2.4. ETH Zürich, Switzerland

3. Discussion

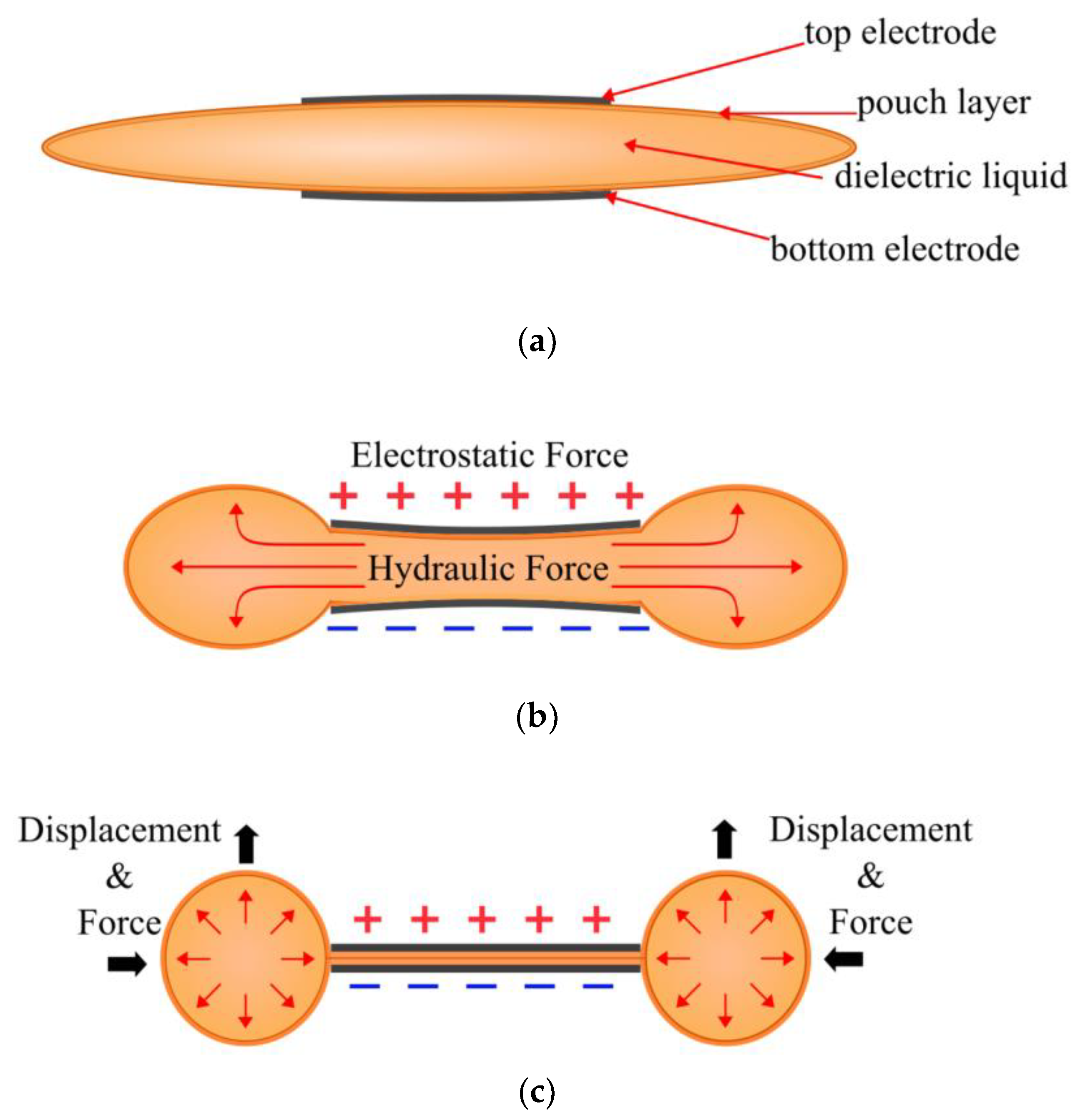

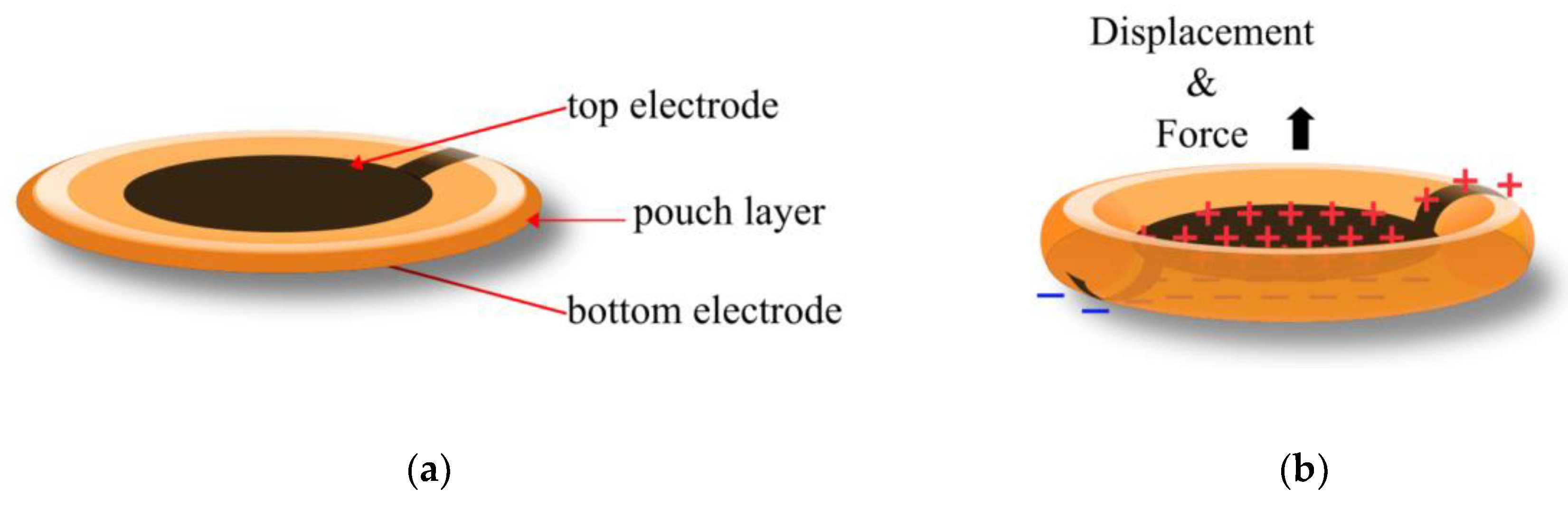

3.1. Expanding Electrohydraulic Actuators

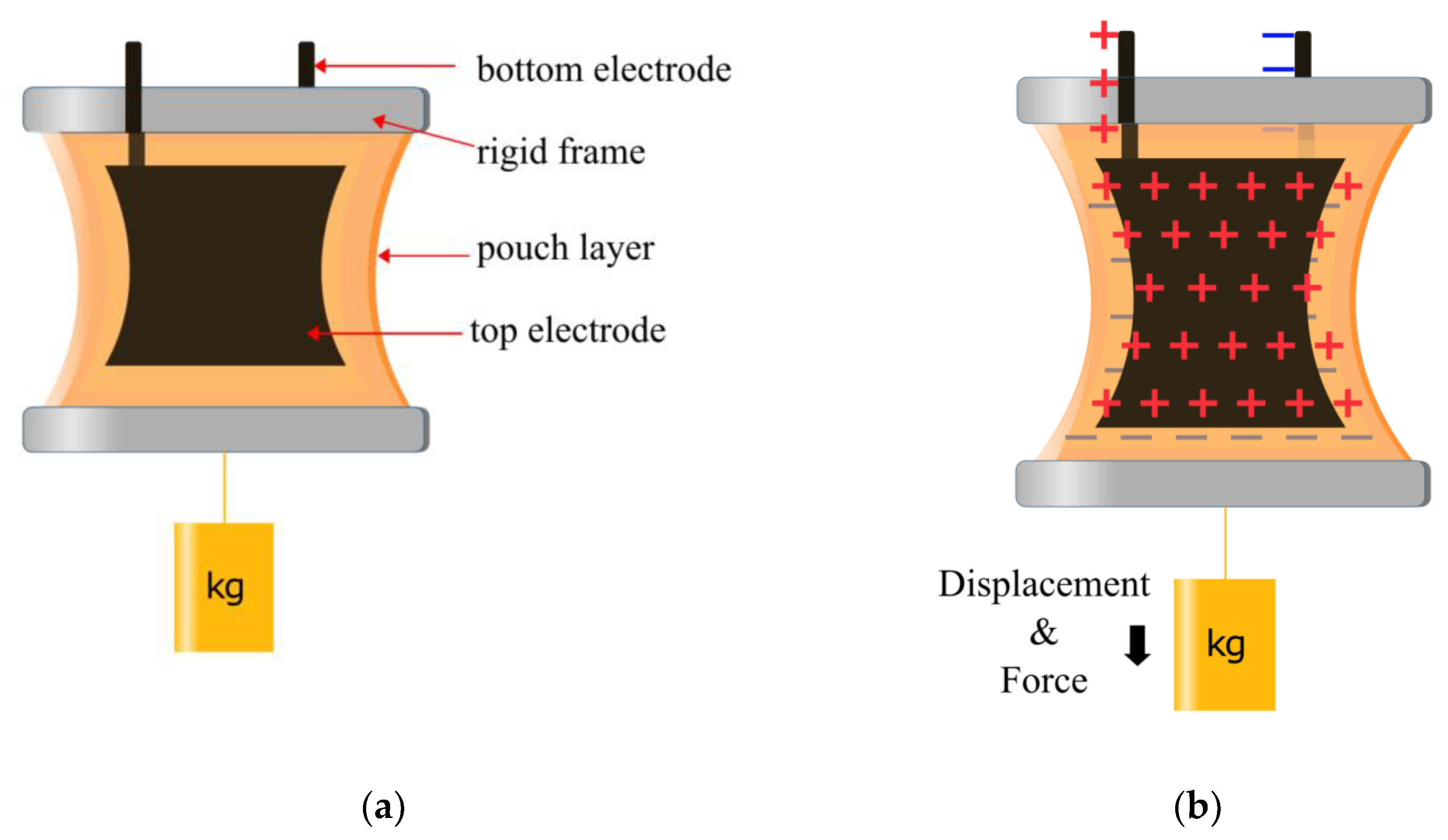

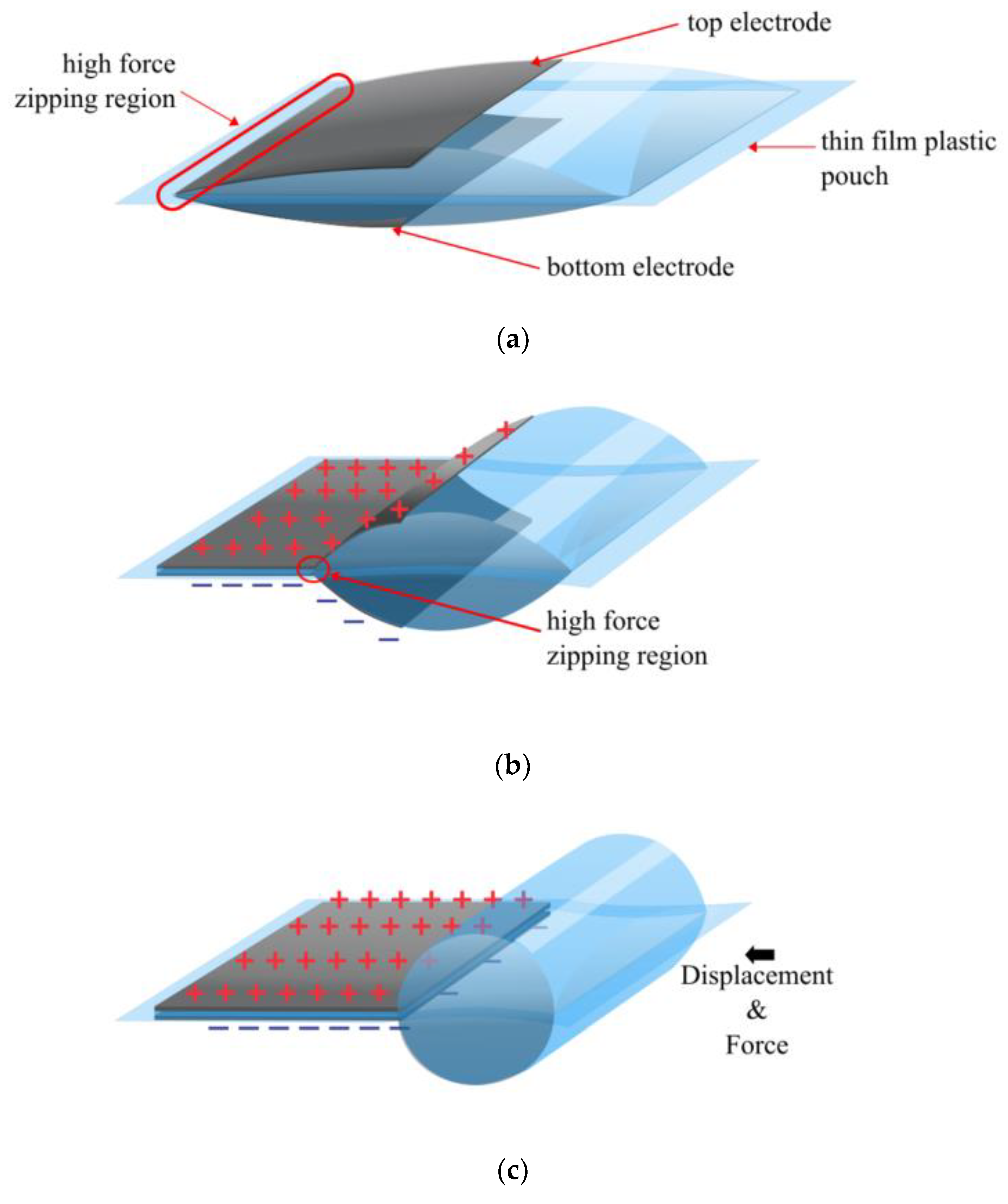

3.2. Contracting Electrohydraulic Actuators

3.2. Electrostatic Force Analysis

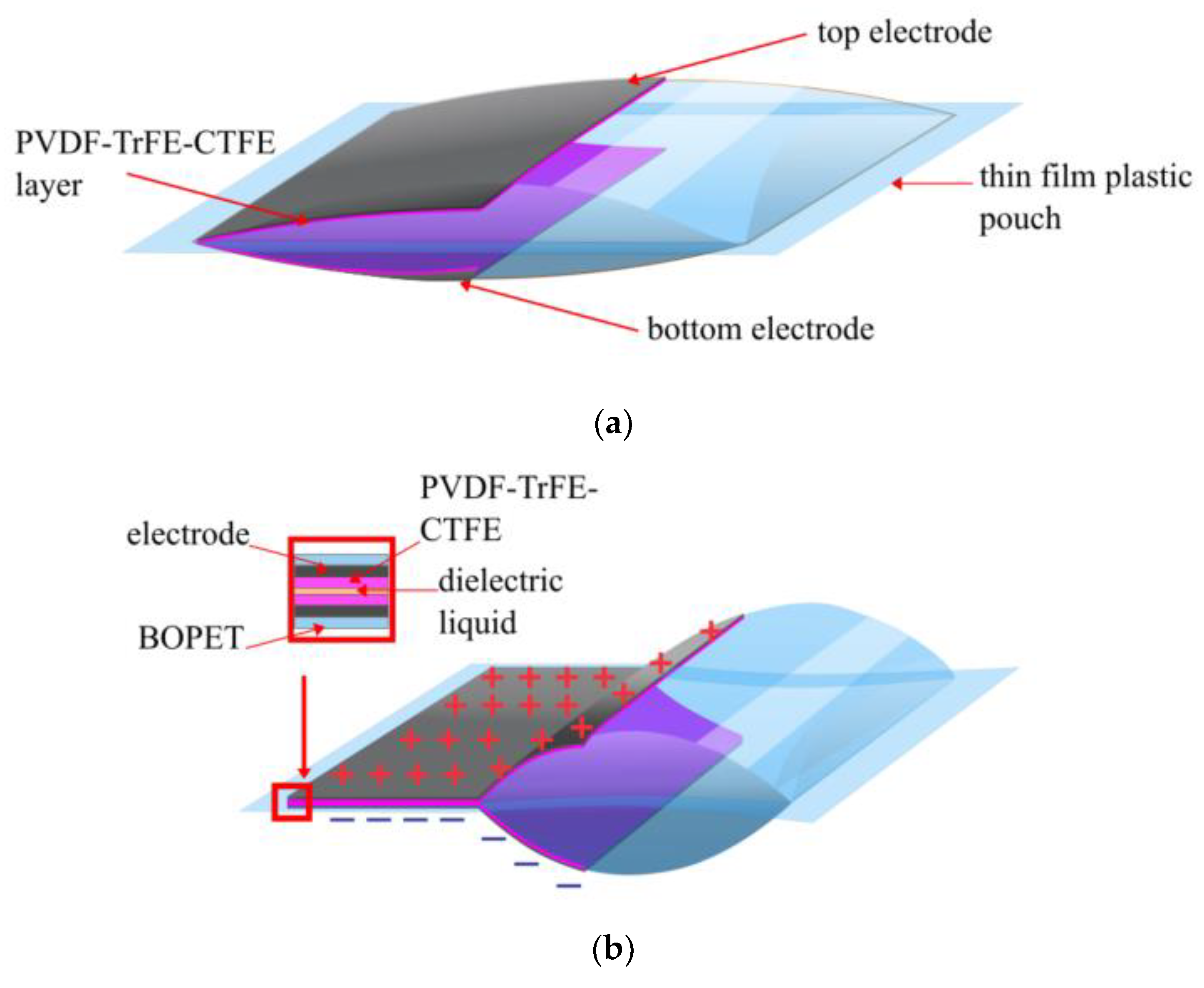

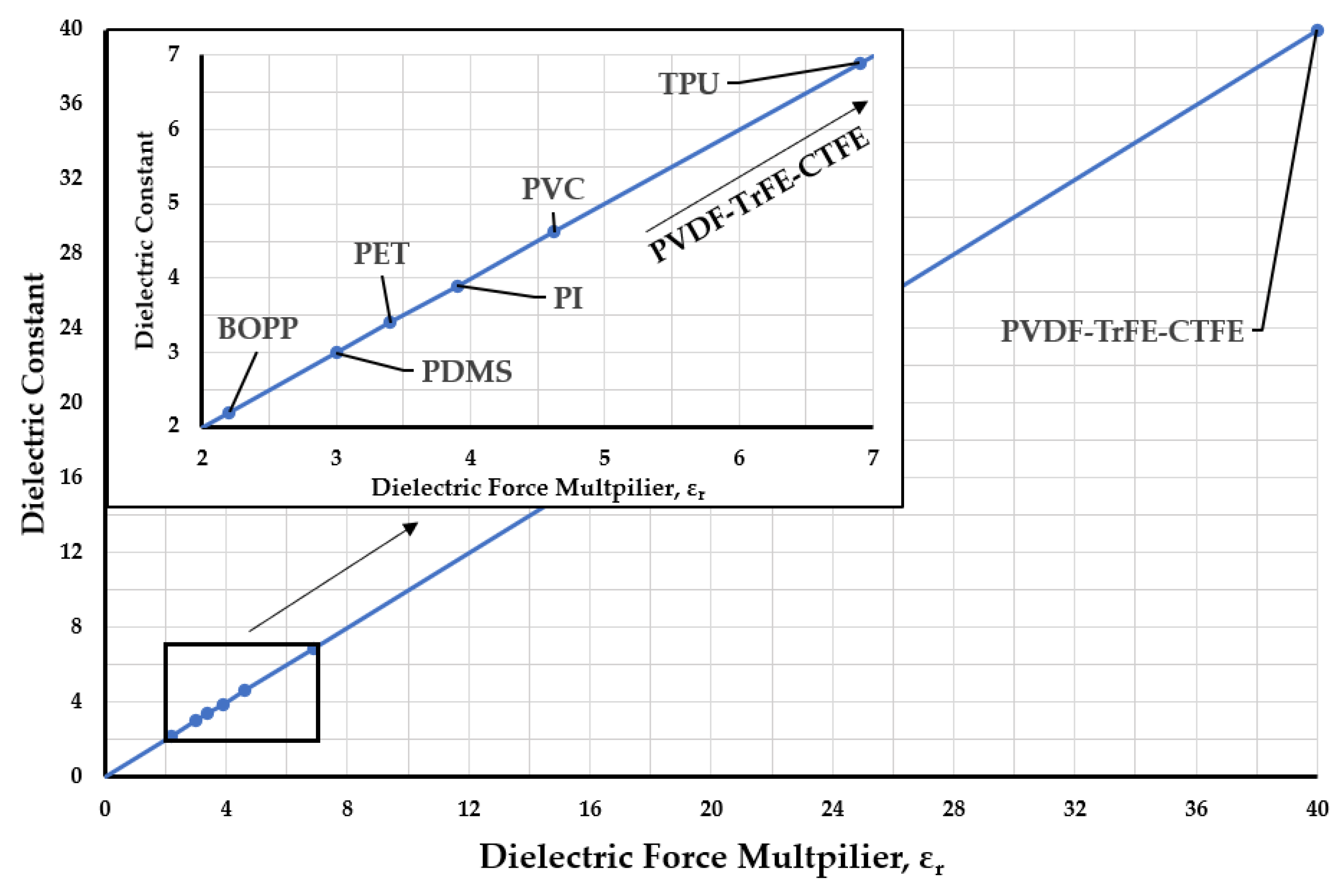

3.3. Dielectric Pouch Materials

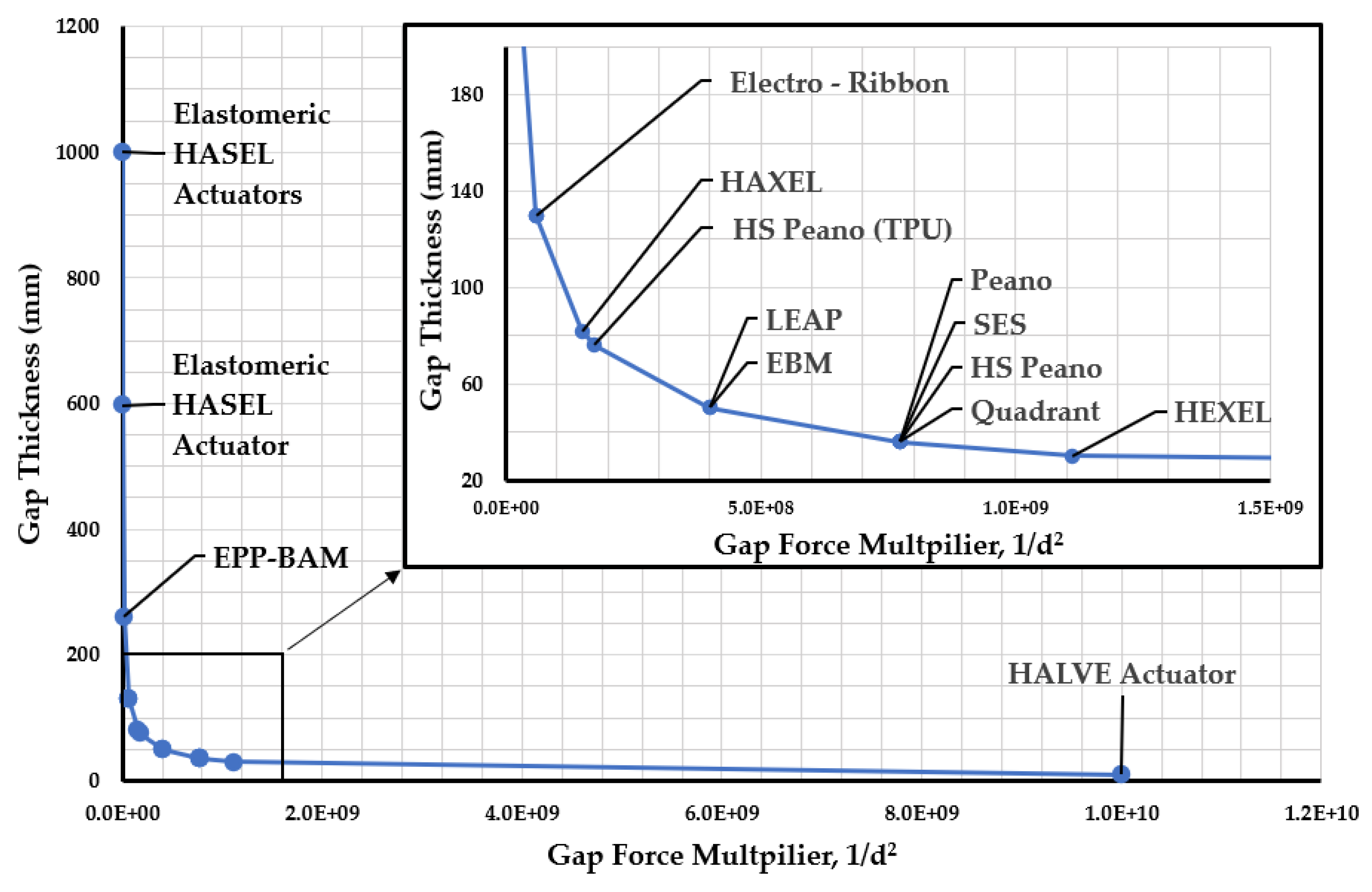

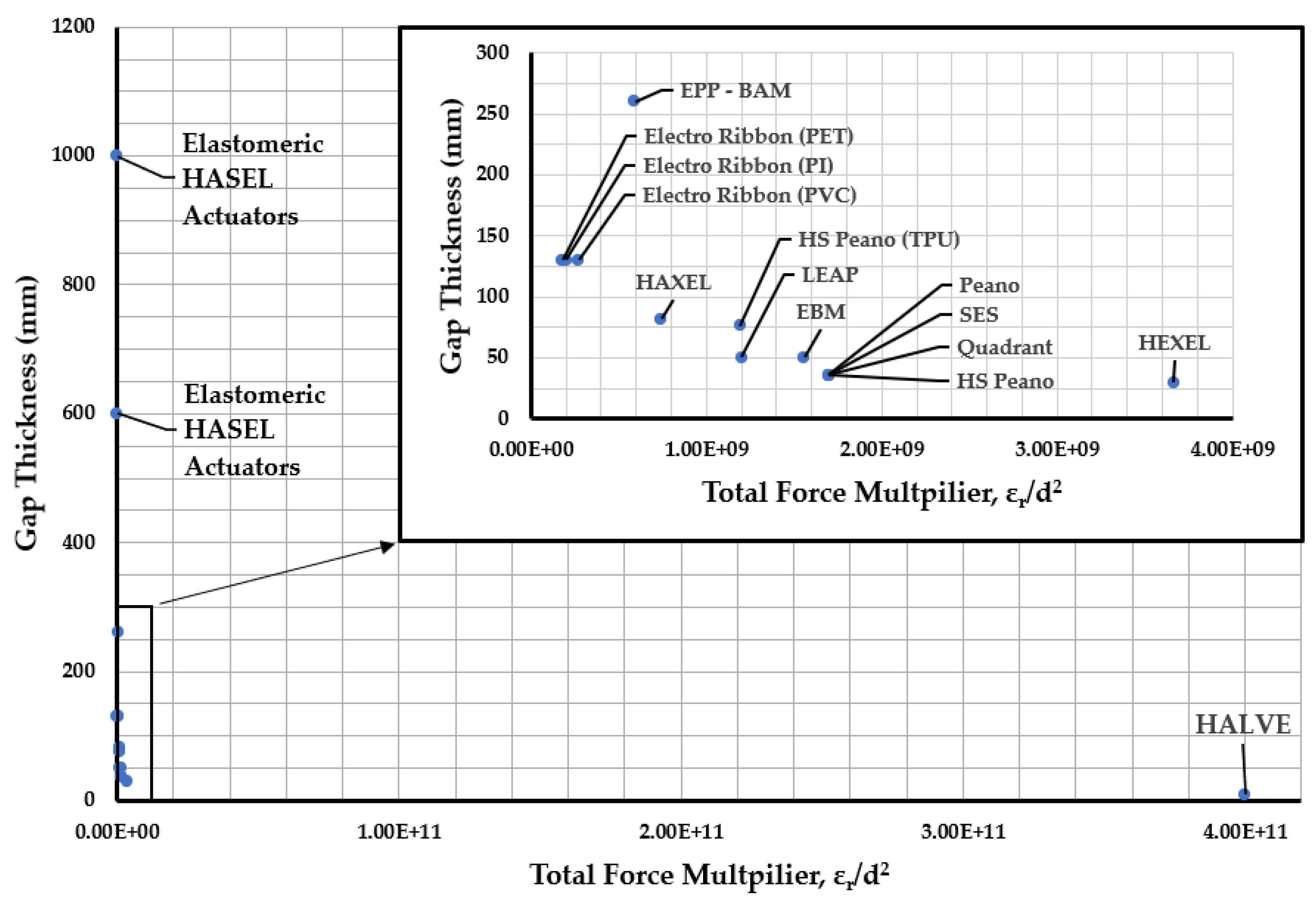

3.4. Dielectric Pouch Thickness

3.5. Electrostatic Force in Electrohydraulic Actuators

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellemare, F.; Woods, J.J.; Johansson, R.; Bigland-Ritchie, B. Motor-unit discharge rates in maximal voluntary contractions of three human muscles. Journal of neurophysiology 1983, 50, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polygerinos, P. Editorial: Influential voices in soft robotics. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AboZaid, Y.A.; Aboelrayat, M.T.; Fahim, I.S.; Radwan, A.G. Soft robotic grippers: A review on technologies, materials, and applications. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2024, 372, 115380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mushtaq, R.T.; Wei, Q. Advancements in Soft Robotics: A Comprehensive Review on Actuation Methods, Materials, and Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acome, E.; Mitchell, S.K.; Morrissey, T.G.; Emmett, M.B.; Benjamin, C.; King, M.; Radakovitz, M.; Keplinger, C. Hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic actuators with muscle-like performance. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 2018, 359, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellaris, N.; Gopaluni Venkata, V.; Smith, G.M.; Mitchell, S.K.; Keplinger, C. Peano-HASEL actuators: Muscle-mimetic, electrohydraulic transducers that linearly contract on activation. Science Robotics 2018, 3, eaar3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothemund, P.; Kim, Y.; Heisser, R.H.; Zhao, X.; Shepherd, R.F.; Keplinger, C. Shaping the future of robotics through materials innovation. Nature Materials 2021, 20, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keplinger, C.M.A., Eric Lucas; Kellaris, Nicholas Alexander; Mitchell, Shane Karl; Emmett, Madison Bainbridge. Hydraulically Amplified Self-healing Electrostatic Actuators. 2020.

- Keplinger, C.M.A., Eric Lucas; Kellaris, Nicholas Alexander; Mitchell, Shane Karl; Morrissey, Timothy G. Hydraulically Amplified Self-Healing Electrostatic Transducers Harnessing Zipping Mechanism. 2021.

- Kellaris, N.; Venkata, V.G.; Rothemund, P.; Keplinger, C. An analytical model for the design of Peano-HASEL actuators with drastically improved performance. Extreme Mechanics Letters 2019, 29, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, P.; Kellaris, N.; Keplinger, C. How inhomogeneous zipping increases the force output of Peano-HASEL actuators. Extreme Mechanics Letters 2019, 31, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mitchell, S.K.; Rumley, E.H.; Rothemund, P.; Keplinger, C. High-Strain Peano-HASEL Actuators. Advanced functional materials 2020, 30, 1908821-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keplinger, C.M.W., Xingrui; Mitchell, Shane Karl. High Strain Peano Hydraulically Amplified Self-Healing Electrostatic (HASEL) Transducers. 2021.

- Mitchell, S.K.; Wang, X.; Acome, E.; Martin, T.; Ly, K.; Kellaris, N.; Venkata, V.G.; Keplinger, C. An Easy-to-Implement Toolkit to Create Versatile and High-Performance HASEL Actuators for Untethered Soft Robots. Advanced science 2019, 6, 1900178-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellaris, N.; Rothemund, P.; Zeng, Y.; Mitchell, S.K.; Smith, G.M.; Jayaram, K.; Keplinger, C. Spider-Inspired Electrohydraulic Actuators for Fast, Soft-Actuated Joints. Advanced science 2021, 8, 2100916-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keplinger, C.M.A., Eric Lucas; Kellaris, Nicholas Alexander; Mitchell, Shane Karl; Emmett, Madison Bainbridge. HYDRAULICALLY AMPLIFIED SELF-HEALING ELECTROSTATIC (HASEL) TRANSDUCERS. 2024.

- Yoder, Z.; Rumley, E.H.; Schmidt, I.; Rothemund, P.; Keplinger, C. Hexagonal electrohydraulic modules for rapidly reconfigurable high-speed robots. Science Robotics 2024, 9, eadl3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Hinchet, R.; Shea, H. Multimode Hydraulically Amplified Electrostatic Actuators for Wearable Haptics. Advanced materials (Weinheim) 2020, 32, 2002564-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, E.; Shea, H. Hydraulically Amplified Electrostatic Taxels (HAXELs) for Full Body Haptics. Advanced Materials Technologies 2023, 8, 2300242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.S. , Herbert; Gao, Min. Hydraulically amplified dielectric actuator taxels. 2022.

- Schlatter, S.; Grasso, G.; Rosset, S.; Shea, H. Inkjet Printing of Complex Soft Machines with Densely Integrated Electrostatic Actuators. Advanced intelligent systems 2020, 2, 2000136-n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatter, S. Inkjet printing of soft machines; EPFL: 2020.

- Duranti, M.; Righi, M.; Vertechy, R.; Fontana, M. A new class of variable capacitance generators based on the dielectric fluid transducer. Smart materials and structures 2017, 26, 115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Kim, H.; Najafi, K. Electrostatically driven micro-hydraulic actuator arrays. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), 24-28 Jan. 2010; pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ion-Dan, S.; Giacomo, M.; Sandra, D.; Luca, F.; Rocco, V.; Devid, M.; Marco, F. Electrostatic actuator for tactile display based on hydraulically coupled dielectric fluids and soft structures. In Proceedings of the Proc.SPIE, 2019; p. 109662D.

- Sîrbu, I.D.; Moretti, G.; Bortolotti, G.; Bolignari, M.; Diré, S.; Fambri, L.; Vertechy, R.; Fontana, M. Electrostatic bellow muscle actuators and energy harvesters that stack up. Science Robotics 2021, 6, eaaz5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluett, S.; Helps, T.; Taghavi, M.; Rossiter, J. Self-sensing Electro-ribbon Actuators. IEEE robotics and automation letters 2020, 5, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diteesawat, R.S.; Helps, T.; Taghavi, M.; Rossiter, J. Electro-pneumatic pumps for soft robotics. Science Robotics 2021, 6, eabc3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, M.; Helps, T.; Rossiter, J. Characterisation of Self-locking High-contraction Electro-ribbon Actuators. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 31 May-31 Aug. 2020; pp. 5856–5861. [Google Scholar]

- Diteesawat, R.S.; Fishman, A.; Helps, T.; Taghavi, M.; Rossiter, J. Closed-Loop Control of Electro-Ribbon Actuators. Frontiers in robotics and AI 2020, 7, 557624–557624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghavi, M.; Helps, T.; Rossiter, J. Electro-ribbon actuators and electro-origami robots. Science Robotics 2018, 3, eaau9795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Taghavi, M. Material and Structural Improvement in Electro-Ribbon Actuators Towards Biomimetic Stacked Architecture. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), 14-17 April 2024; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar]

- Diteesawat, R.S.; Helps, T.; Taghavi, M.; Rossiter, J. Characteristic Analysis and Design Optimisation of Bubble Artificial Muscles (BAMs). Soft Robotics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravert, S.-D.; Varini, E.; Kazemipour, A.; Michelis, M.Y.; Buchner, T.; Hinchet, R.; Katzschmann, R.K. Low-voltage electrohydraulic actuators for untethered robotics. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadi9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tscholl, D.; Gravert, S.-D.; Appius, A.X.; Katzschmann, R.K. Flying Hydraulically Amplified Electrostatic Gripper System for Aerial Object Manipulation. In Proceedings of the Robotics Research, Cham, 2023//, 2023; pp. 368-383.

- Buchner, T.J.K.; Fukushima, T.; Kazemipour, A.; Gravert, S.-D.; Prairie, M.; Romanescu, P.; Arm, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.L.; et al. Electrohydraulic musculoskeletal robotic leg for agile, adaptive, yet energy-efficient locomotion. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.R.; Eberlein, M.; Christoph, C.C.; Baumann, F.; Bourquin, F.; Wende, W.; Schaub, F.; Kazemipour, A.; Katzschmann, R.K. High-Frequency Capacitive Sensing for Electrohydraulic Soft Actuators. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 14-18 Oct. 2024; pp. 8299–8306. [Google Scholar]

- Tynan, L.; Naik, G.; Gargiulo, G.; Gunawardana, U. Implementation of the Biological Muscle Mechanism in HASEL Actuators to Leverage Electrohydraulic Principles and Create New Geometries. Actuators 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Chung, J.-Y. Evaluation of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as a substrate for the realisation of flexible/wearable antennas and sensors. Micromachines 2023, 14, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.Q.; Liu, Y.; Lin, X.; Huang, E.; Lin, X.; Wu, X.; Lin, J.; Luo, R.; Wang, T. Exploration of Breakdown Strength Decrease and Mitigation of Ultrathin Polypropylene. Polymers 2023, 15, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Du, B.; Qin, Y. Dielectric property and breakdown strength performance of long-chain branched polypropylene for metallised film capacitors. Materials 2022, 15, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, G.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W. Development and research trends of a polypropylene material in electrical engineering: A bibliometric mapping analysis and systematical review. Frontiers in Energy Research 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhou, J.; Jin, L.; Long, X.; Wu, H.; Xu, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, W. Improved dielectric properties of thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer filled with core–shell structured PDA@ TiC particles. Materials 2020, 13, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulrez, S.; Ali Mohsin, M.; Shaikh, H.; Anis, A.; Poulose, A.; Yadav, M.; Qua, P.; al-zahrani, S. A review on electrically conductive polypropylene and polyethylene. Polymer Composites 2014, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Dabbak, S.Z.; Illias, H.A.; Ang, B.C.; Abdul Latiff, N.A.; Makmud, M.Z.H. Electrical properties of polyethylene/polypropylene compounds for high-voltage insulation. Energies 2018, 11, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikac, L.; Csáki, A.; Zentai, B.; Rigó, I.; Veres, M.; Tolić, A.; Gotić, M.; Ivanda, M. UV Irradiation of Polyethylene Terephthalate and Polypropylene and Detection of Formed Microplastic Particles Down to 1 μm. ChemPlusChem 2024, 89, e202300497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Kaneko, M.; Zhong, X.; Takada, K.; Kaneko, T.; Kawai, M.; Mitsumata, T. Effect of Water Absorption on Electric Properties of Temperature-Resistant Polymers. Polymers 2024, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisca, S.; Sava, I.; Musteata, V.E.; Bruma, M. Dielectric and conduction properties of polyimide films. In Proceedings of the CAS 2011 Proceedings (2011 International Semiconductor Conference), 17-19 Oct. 2011; pp. 253–256. [Google Scholar]

- Bahgat علاء الدين عبد الحميد بهجت, A.; Sayyah, S.; Shalabi, H. Electrical Properties of Pure PVC. 1998; pp. 421-428.

- P S, L.P.; Swain, B.; Rajput, S.; Behera, S.; Parida, S. Advances in P(VDF-TrFE) Composites: A Methodical Review on Enhanced Properties and Emerging Electronics Applications. Condensed Matter 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Actuator | University | Applied Voltage (kV) | Max. Free Strain (%) | Max. Blocking Force (N) | Peak Specific Power (W/kg) | Peak Average Specific Power (W/kg) |

Specific Energy (J/Kg) |

| Elastomeric Donut HASEL actuator | University of Colorado Boulder | 21 | 40 – 50 | 2.45 – 3.92 | |||

| Planar HASEL actuator | University of Colorado Boulder | ~22.5 | 79 | 2.45-14.72 | 614 | 70 | |

| Three-stack Quadrant HASEL actuator | University of Colorado Boulder | 12 | 118 | ~60* | 121 | > 60 | 12 |

| HEXEL | University of Colorado Boulder | 9.5 | 113 | >2 | 90 | ~30 | |

| HAXEL | EPFL | 2 | 60 | 0.1 – 0.8 | 102 | 0.51 | |

| LEAP | University of Trento | 4.5 | 0.017 |

| Actuator | Institution | Applied Voltage (kV) | Max. Free Strain (%) | Max. Blocking Force (N) | Peak Specific Power (W/kg) | Peak Average Specific Power (W/kg) |

Specific Energy (J/Kg) |

| Three-stack Peano HASEL actuator |

University of Colorado Boulder | 10 | 9 – 15 | 9.81 – 60 | 160 | > 50 | 4.93 |

| HS Peano HASEL actuator | University of Colorado Boulder | 10 | 24 | 18 | ~120 | ~78 | 4.03 |

| SES | University of Colorado Boulder | 9 | 230 | 110 | 10.3 | ||

| HEXEL | University of Colorado Boulder | 9.5 | 47.7 | 37.6 | 122 | 2.3 | |

| Three – Six series EBM | University of Trento | 8 | 43 | ~7* | 31 | ||

| Electro ribbon Actuator | University of Bristol | 10 | >99 | 0.172* | |||

| EPP-BAM | University of Bristol | 10 | 32.4 | 0.981* | 112.16 | 2.59 | |

| HALVE actuator | ETH Zürich | 1.1 | 9 | 5* | 50.5 |

| Actuator | Institution | Dielectric Material | Dielectric Thickness (µm) | Dielectric Layers |

Total Dielectric Gap (µm) |

Relative Permittivity |

Compliant/ Elastomeric |

| Elastomeric Donut HASEL Actuator |

University of Colorado Boulder | Ecoflex | 500 | 2 | 1000 | 2.3 – 3 | Elastomeric |

| PDMS | 300 | 2 | 600 | 2.3 – 3 | Elastomeric | ||

| Elastomeric Donut HASEL Actuator |

University of Colorado Boulder | Ecoflex | 500 | 2 | 1000 | 2.3 – 3 | Elastomeric |

| PDMS | 300 | 2 | 600 | 2.3 – 3 | Elastomeric | ||

| Peano HASEL actuator |

University of Colorado Boulder | BOPP | 18 – 21 | 2 | 42 | 2.2 | Compliant |

| HS Peano HASEL Actuator | University of Colorado Boulder | BOPP | 18 | 2 | 36 | 2.2 | Compliant |

| TPU | 38 | 2 | 76 | 6.9 | Elastomeric | ||

| Quadrant HASEL Actuator | University of Colorado Boulder | BOPP | 18 | 2 | 36 | 2.2 | Compliant |

| SES | University of Colorado Boulder | BOPP | 18 | 2 | 36 | 2.2 | Compliant |

| HEXEL | University of Colorado Boulder | PET | 15 – 30 | 2 | 30 – 60 | 3.3 | Compliant |

| HAXEL | EPFL | PET | 12 50 – 100* |

1 1 |

82 – 132 | 3.3 | Compliant |

| PVDF-TrFE-CTFE, | 5 15* |

1 1 |

38 | Compliant | |||

| LEAP | University of Trento | PDMS | 50 | 1 | 50 | 2.3 – 3 | Elastomeric |

| EBM | University of Trento | PI | 25 | 2 | 50 | 3.9 | Compliant |

| Electro ribbon Actuator | University of Bristol | PET | 130 | 1 | 130 | 3 – 3.4 | Compliant |

| PI | 130 | 1 | 130 | 3.4 – 3.5 | Compliant | ||

| PVC | 130 | 1 | 130 | 4.62 | Compliant | ||

| EPP-BAM | University of Bristol | PVDF-TrFE-CTFE | 130 | 2 | 260 | 40 | Compliant |

| HALVE Actuator | ETH Zürich | PVDF-TrFE-CTFE | 5 | 2 | 10 | 40 | Compliant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).