1. Introduction

The state of Rio Grande do Sul (RS) is known nationwide for its quality of life, but also for its budgetary and financial difficulties. The aging population, as already pointed out by the social security system, presents an additional challenge. In the context of the climate crisis, recurring droughts significantly affect RS and, consequently, the national economy, given the state’s substantial agricultural output. A study on the impact of droughts in RS found that economic activity in 75% of the affected municipalities typically recovers within three months. This rapid recovery may contribute to a sense of complacency in implementing preventive measures, despite the substantial losses [

1]. In 2012, Brazil identified 821 municipalities at risk of flooding, flash floods and landslides, including 31 municipalities in RS. The rising frequency of extreme weather events has necessitated a review of public policies addressing these risks. In 2023, the criteria and indicators for identifying at-risk municipalities were updated, resulting in the creation of the Municipal Capacity Indicator (ICM). This indicator assesses the ability of municipalities to manage risks and disasters. Following the update, the number of priority municipalities increased from 821 to 1972, of which only 33 demonstrated high capacity, while 324 exhibited intermediate capacity. This underscores the magnitude of the challenge facing Brazil [

2]. In RS, the new criteria identified 142 priority municipalities, with 313,335 people living in high-risk areas. In May 2024, the state experienced the largest flood in its history, surpassing the catastrophic event of 1941. An assessment conducted by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the World Bank, estimated the total effects of the floods in RS at BRL 88.9 billion, with the private sector bearing 78% of this total in terms of losses and damages. A public calamity was declared for 95 municipalities and a state of emergency for 323. The disaster directly affected 876,565 people; an estimate based on the flood area. There were also 183 deaths and 806 people were injured. 77,000 rescues were carried out by public authorities alone, with the involvement of volunteers being notable, which would significantly increase this number if calculated. Approximately 600,000 people were displaced, with 81,000 being assisted in 980 shelters in 117 municipalities. This is one of the largest disasters ever recorded in RS, where rainfall significantly exceeded historical averages, with some areas recording up to 300 mm of rain in a single day [

3].

The economic impact of the floods is substantial. Despite a prompt response by the federal and local governments, the state’s GDP is projected to decline by 1.3%. Pre-flood economic growth estimates of 6% for 2024 have been revised to 4.7% [

3]. The effects of heavy rains are not limited to RS. For example, in Santa Catarina in 2008, a synthetic control analysis indicated a 5.13% drop in monthly industrial production over two years due to similar events [

4]. In a country that operates under the principle of fiscal federalism, addressing environmental disasters of such magnitude requires administrative and fiscal cooperation to achieve effective and efficient solutions. Brazilian republican federalism is marked by tensions and conflicts, advances and setbacks, alternating between periods of greater centralization and periods of greater decentralization, which grant more autonomy to subnational entities. The main challenge is addressing a definitive format, due to conflicting interests, choices and ideas [

5].

Regional inequalities and the strong municipalist tradition have shaped Brazilian fiscal federalism, particularly under 1988 Constitution [

6]. Since the late 20th century, there has been a global trend toward decentralizing public spending to subnational levels (state and local). This trend is not limited to federations but has also influenced traditionally centralized unitary states. This is due to the political evolution toward more democratic and participatory forms of government, which aim to improve the responsiveness of public policies to the preferences and expectations of their beneficiaries [

7]. An example of an effective subnational policy that involves both the taxation and public spending is the experience of the Devolve-ICMS program, implemented in Rio Grande do Sul, where part of the tax burden on low-income families is returned to mitigate the regressiveness of the consumption tax [

8]. Currently, the experience has been incorporated into the ongoing tax reform in Brazil and is expected to be extended to nationwide with the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (IBS).

This study aims to analyze the natural disaster of the floods that hit Rio Grande do Sul in May 2024 and mainly to identify the fiscal response capacity of the municipalities of RS, and especially those in a state of calamity. It also proposes a public policy framework offering financial solution for the prevention and mitigation of future disasters. The methodology employed involved an exploratory analysis of fiscal data from municipalities contained in the Brazilian Public Sector Accounting and Fiscal Information System (SICONFI). An indicator was developed, based on current revenue to evaluate the fiscal space available to municipalities. This article consists of this introduction, followed by

Section 2, which provides an overview of Brazilian fiscal federalism, including the financial challenges faced by the state of Rio Grande do Sul. It also reviews federalism in the context of climate change and examines measures taken to mitigate the effects of floods.

Section 3 describes the methodology applied in the study.

Section 4 presents and discusses the results, with a focus on the budgetary and financial capacity of municipalities in Rio Grande do Sul to respond to natural disasters. The final section offers conclusions and suggests potential public policy recommendations in the fiscal and budgetary sphere to prepare for and respond to future climate disasters.

2. Fiscal Federalism

The finances of Brazilian municipalities are not as fragile as is often perceived. Since the Federal Constitution of 1988, their share of their own and available tax revenue has increased considerably, though their responsibilities have also expanded. Over the last decade, the overall tax burden has remained stable, with consumption taxes continuing to be the largest source of revenue for the Brazilian state, accounting for 12.68% of revenue. However, their relative importance has been declining. Notably, taxes on income, profits, and capital gains have grown in significance, increasing their share from 6.65% in 2010 to 8.66% in 2013 [

9]. The Brazilian tax burden of 32.44% (2023) is higher than the Latin American average of 21.65% (2021), and slightly lower than the OECD average of 34.04% (2022).

Table 1 illustrates the evolution of the gross tax burden (GTB) by federated entity.

Regarding available revenue, the Independent Fiscal Institution [

10] reported an increase in the municipal share to 6.6% of GDP in 2017, compared to 5.7% in 2002. Over the same period, the states’ share remained stable at 8.6%, while the federal share declined to 15.9%. Consequently, the distribution of the tax burden in 2017 was as follows: 51% for the Union, 28% for the States, and 21% for the Municipalities.

Despite the increase in municipal revenue, it is important to note that municipal obligations have grown significantly. Municipalities are subject to the same minimum spending requirements as the states, including 25% of revenue allocated to education. However, in the health sector, municipalities must allocate a minimum of 15% of their revenue, exceeding the states’ required minimum of 12%. This rigidity in expenditure, driven by mandated minimum percentages, constrains municipalities’ ability to address extraordinary situations. In addition to these financial obligations, municipalities are responsible for numerous essential services that directly impact citizens’ lives. These include primary education, family health care, basic sanitation, public transportation, and waste management, among other critical areas.

According to the Financial Bulletin of Subnational Entities [

11], Brazilian capital cities allocate a median of 54.4% of their total expenses to operating expenses. Across all Brazilian municipalities, positive budgetary results are a consistent trend, contributing to the country’s overall financial health. In 2021, municipalities collectively reported a budget surplus of 92 billion reais, followed by a surplus of 53 billion reais in 2022. Municipal debt levels are also relatively low. Among the 5565 municipalities in Brazil, only 22 exceed the debt limit of 120% of Net Current Revenue (RCL), with none located in Rio Grande do Sul. In RS, out of 497 municipalities, only 28 have debts exceeding 20% of their respective RCL (Transparent Treasury). However, not all municipalities have balanced pension systems, which could pose significant fiscal challenges in the future. Additionally, local economies are being influenced by emerging factors, such as the expansion of large e-commerce platforms and regional distribution centers. Despite these shifts, many municipalities benefit from the presence of family farming and small agribusinesses, which not only meet local needs but also serve as key drivers of resilience for local economies.

2.1. The finances of the State of Rio Grande do Sul

The last few decades in Rio Grande do Sul (RS) have been characterized by persistent budgetary imbalances and short-lived adjustment efforts. Stability only began to emerge in 2020 with the adoption of the Fiscal Recovery Regime (RRF) and a series of prior fiscal adjustment measures. To address recurring deficits, the state relied heavily on funds from the unified accounting system (SIAC) and Court Deposits, authorized in 2004 by Law 12,069/04. From 2004 to 2013, the state achieved a sustained cycle of positive primary results. However, starting in 2015, RS faced one of its most severe financial crises. During this period, the single cash flow system had limited availability, investments were negligible, and payroll payments were consistently delayed for nearly five years. Over the past two decades, the state’s economic growth has ranked as the second lowest in Brazil. A consistent recovery in primary results only began in 2020.

In 2019, the state implemented a series of structural reforms, including pension and administrative reforms, which successfully curbed the automatic growth of the payroll. The State Revenue Service also underwent significant changes, emphasizing taxpayer compliance and investing heavily in digital technologies and sector monitoring. As part of these efforts, programs such as Devolve-ICMS [

8] and Receita Certa [

12] were launched, returning taxes to society. Additionally, the Menor Preço and Menor Preço Brasil apps were introduced, helping citizens of RS and beyond find lower-priced products, reducing travel costs and risks, particularly during the pandemic [

13]. By 2021, the state resumed paying salaries and suppliers on time, and in 2022 it successfully joined the Fiscal Recovery Regime (RRF). This program allows for a gradual resumption of public debt payments over a 10-year period. As of 2023, RS’s public debt stock had reached BRL 92.8 billion, equivalent to 185% of its Net Current Revenue [

14]. Recent fiscal discipline and revenues from privatizations have significantly strengthened the single cash system, which reached BRL 12.2 billion in 2023, according to the State General Balance Sheet. Investment capacity has also been restored, remaining consistently at around BRL 3 billion over the past two years—exceeding 5% of the state’s Net Current Revenue (RCL).

The Impact of flooding on revenue collection

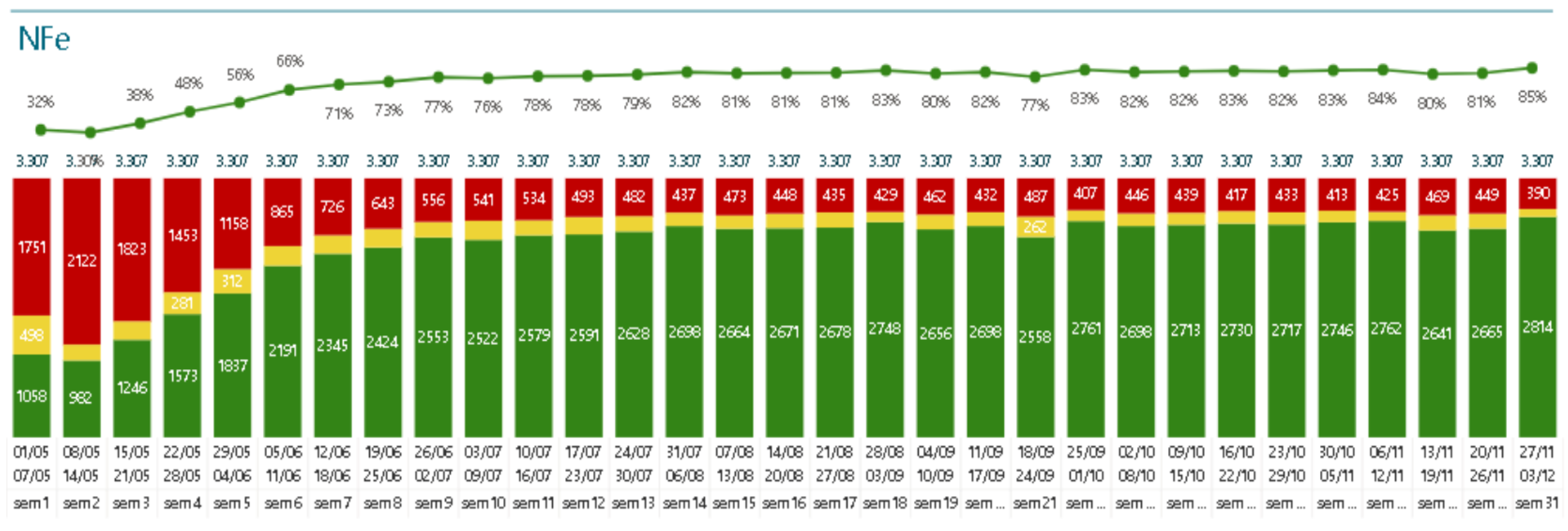

Using data from electronic invoices, we can see at a highly detailed level the evolution of the recovery of the RS economy after the flood. Regarding the 40,233 establishments under the General ICMS Regime throughout the state, the 12/09/24 snapshot shows that 91% of the companies are operating at a high level, 2% at a medium level and 7% at a low level six months after the flood. In the flooded areas, which have 3307 establishments under the general regime, the evolution of the level of activity measured by the issuance of the NFe shows that only 32% were operating normally in the first week of the event, reaching 66% in the sixth week [

15]. As of the third month, it reached 82%, a level close to the current 85% (

Figure 1). Around 12% of the companies continue to operate at a low level. In the same area, practically identical numbers were recorded in the 5106 companies under the Simples Nacional (85% and 13%).

It is possible to observe the rapid economic recovery on a week-to-week basis. The hardest-hit regions needed a little more time for economic activity to return to normal. During the peak of the crisis in the first 10 days of May 2024, the average number of invoices issued over a 7-day period dropped by 84% for consumer invoices and 78% for business-to-business invoices. Business-to-business invoices recovered more rapidly, and thanks to the extraordinary financial support from federal and state governments, both types of invoices returned to near-normal levels by the end of the year [

15].

As for ICMS revenue, the sharp drop in revenue that was expected at the beginning of the catastrophe did not occur, and over the three-month period, the actual revenue collected was 4% lower than the forecast. The revenue collected from May 1 to November 30 was 4.9% above the projection, representing an additional BRL 1.4 billion in revenue [

15,

16]. As expected, a rapid recovery was observed, even stronger than that which occurred at the time of COVID-19. In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was found that the first 3 months had the greatest negative impact, followed by a return to normality in the following 3 months and a period of significant growth soon after. The issuance of Electronic Invoices (NF-e + NFC-e) recorded its worst result in April (−16.7%), followed by May (−10.2%) and in June it showed a variation of +3.4, always in relation to the same month of the previous year. The best performance occurred in December with a variation of +14.6%. ICMS collection is the main source of revenue for the state, and the share belonging to the municipalities of RS corresponds, on average, to 15% of their current revenues. In 2020, ICMS collection ended slightly lower than in 2019, 2.9% lower in real terms. During 2020, and immediately after the start of the pandemic, there was a sequence of five months of negative variations, and in August, a strong recovery was already established [

17].

2.2. Federalism and climate change

Climate change is in the spotlight around the world. From wildfires in Canada and Greece to torrential rains and floods in Libya, Spain, and Guatemala, these events are causing human and material losses and overwhelming governments at all levels of administration. There are at least two reasons why subnational governments should act in mitigation and adaptation to climate change. The first is that the costs and benefits of climate change vary within different territories, across various regions and localities. The second is that, in general, subnational entities are exclusively responsible for, in some cases share with other spheres the expenses and main regulatory functions involving the issue. Confronting climate change requires increased investment and intergovernmental cooperation, with an alignment of the entities’ policies [

18].

Public actions regarding climate change often occur in a centralized manner, with few countries sharing responsibilities with subnational governments. The most effective practices include the use of taxes or fees as a source of financing for adaptation activities that tend to be more local, intergovernmental transfers for specific purposes, and green bonds. The principle of subsidiarity is worth highlighting, stating that the responsibility for providing services should preferably be assigned to the lowest possible level of government. This is expected to make governments more accountable to residents [

19].

According to Tiebout, the ideal model for subnational governments is based on competition between them, along the lines of a market system, resulting in efficiency gains, as public goods would be offered in the quantity and quality desired by citizens [

20]. The Brazilian model has adopted this type of vision in the fiscal competition between states in the tax collection, but in the area of expenditure, whether on education or health, pluralism and cooperation remain the focus. Defining the responsibilities between the levels of government in a federation for provision of public goods is more difficult to resolve than defining taxation powers. There are several challenges, including the type of goods provided, such as merit goods, the asymmetry of preferences between jurisdictions, individual mobility, and the need to observe economies of scale, among others [

21].

In general, subnational governments oversee and perform well in terms of land use management, housing codes, public water and energy services, waste disposal, or transportation systems [

18,

19].

In situations involving natural disasters, the efficiency of various levels of government undergoes significant changes. A study conducted across 36 countries found that decentralizing spending and granting higher levels of authority to regional governments improve public sector efficiency. However, this effect diminishes in the context of extreme natural disasters, suggesting that decentralized fiscal responses are less effective during such crises [

22]. In China, county-level emergency management plays a crucial role in bridging urban and rural areas. A governance study highlights the positive influence of normative constraints, followed by charismatic policies. It underscores the necessity for governance that integrates both traditional and modern characteristics [

23].

Another option to address the climate issue is green taxation. It is worth noting that only a few countries have the level of green taxation necessary to offset environmental damage. If local governments were to assume the increase in revenue necessary to meet climate demands, there could be excessive taxation and the consequent incentive for the migration of companies and people [

19].

IPEA’s Regional, Urban and Environmental Bulletin emphasizes that federalism is constantly evolving along with the country’s agenda. It highlights that the integration between federalism and environmental sustainability is a promising area of research [

24]. Brazilian fiscal federalism has its own nuances, which makes it difficult to directly import external models. Fiscal education is considered fundamental to its understanding in the context of the socioeconomic function of taxes, as well as public management, and their impacts in terms of equity and efficiency [

25]. Brazil is the 7th largest emitter of GHG, and many countries are already developing long-term plans to decarbonize their economies. Due to deforestation, Brazil is still far from being a low-carbon economy, and per capita emissions exceed 10t CO2e/inhab. (2018), well above the global average. Livestock farming has also been contributing to emissions. The states of Pará and Mato Grosso account for a significant portion of the country’s emissions. In terms of vulnerability to climate change, Brazil is in an intermediate position compared to other countries (92/181). Brazilian federalism presents a favorable context for the formulation of decentralized and even experimental policies, which can generate a process of learning and sharing. In Brazil, all levels of government have some responsibility for the issue, with different powers. In the event of inaction by one entity, there may be some compensation from the action of others, with some states and municipalities taking the lead on the issue, but this is not widespread yet. One positive factor is the engagement of different sectors of society and the existence of several forums [

26]. In recent decades, the United States has experienced a notable increase in catastrophic disasters. Research conducted in states and territories participating in the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program has evaluated the extent to which climate change considerations have been integrated into State Plans. Findings indicate that while integration has indeed taken place, the most frequently reported barriers to comprehensive integration include insufficient funding and competing risk mitigation priorities [

27].

2.3. Measures implemented to support floods

The Federal Government played a significant role in addressing the flooding crisis by temporarily establishing an Extraordinary Secretariat of the Presidency for Support for the Reconstruction of Rio Grande do Sul, granting it the status of a Ministry. Drawing from strategies utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic, measures included the Reconstruction Aid of BRL 5100 for affected families, the Calamity Withdrawal of FGTS funds, and the early disbursement of benefits such as Bolsa Família. Additionally, large-scale credit provisions were made available through BNDES, Banco do Brasil, and Caixa Econômica Federal [

28]. A notable initiative, Pronampe Solidário, subsidized 40% of credit for businesses with revenues of up to BRL 4.8 million in fiscal year 2023, targeting Individual Microentrepreneurs, Microenterprises, and Small Businesses.

Employment retention measures ensured two minimum wages for affected workers, provided they remained employed—a policy widely regarded in economic literature as highly impactful. In the tax domain, payments were deferred for three months, while payroll and real estate loans for affected individuals were postponed and rescheduled. The measure with the greatest impact was the suspension of public debt payments for three years, with the debt balance adjusted solely by the IPCA. The payments that would have been made to the Union during this period will instead contribute to a state reconstruction fund, estimated at BRL 11 billion. At the state level, the Secretariat of Partnerships and Concessions was restructured into the Secretariat for the Reconstruction of Rio Grande do Sul to manage the newly established fund. Additional measures included BRL 2100 in aid for affected individuals, the deferral of loans issued by the State Bank of Rio Grande do Sul, and a tax subsidy of up to BRL 1000 for purchasing essential appliances such as refrigerators, stoves, and washing machines, with ICMS tax refunds provided through the Devolve-ICMS program.

3. Methodology

Many studies and practices have adopted indicators to verify the fiscal capacity of states and municipalities. The National Treasury Secretariat uses CAPAG to assess the fiscal situation of subnational entities that wish to take out new loans guaranteed by the Union [

29]. CAPAG assesses the entity’s indebtedness (DC) in relation to its net current revenue, its current savings (PC) represented by the relationship between current expenses and revenue, and relative liquidity (LR) which reveals the level of financial obligations in relation to the municipality’s cash availability.

Table 2 reveals that indebted municipalities are rare, however the credit operation process is long and will certainly not be an immediate source to face the climate crisis.

The savings indicator (PC) reveals that only 721 municipalities (13%) have current expenses below 85% of current revenue. In other words, they have the capacity to face the extra costs of climate occurrence in terms of expenses. The DC and LR indicators use the Executive Branch’s Fiscal Management Report for the third four-month period as a source of information, while the PC indicator uses data from the last 3 years (

Table 2).

It is very common to use relevant transfers such as the Municipal Participation Fund (FPM) and the ICMS share, as indicators of municipal management. These transfers are tied to economic cycles: the FPM reflects national economic trends, while the ICMS share is more closely aligned with the local economy. To assess the autonomy of a municipality to meet its expenses, there is the indicator of its own savings capacity, which divides municipal revenues by current expenses. The incorporation of state transfers and the ICMS share in the calculation of its own savings capacity significantly changes the indicator. As for the indicator of the degree of dependence of investments on transfers, this will incorporate transfers from other entities into the municipal revenues in the numerator and denominator, while maintaining the reduction in current expenses before the division in the numerator. Ultimately, this indicator reflects the percentage of revenue available for investment. Generally, smaller municipalities tend to be more reliant on national and state transfers [

30].

In another study, the fiscal situation of Brazilian municipalities was explored through panel data from 2002 to 2016. This analysis explored the relationship between revenues, personnel expenses, size strata, economic activity, and municipal wealth, considering variations in national GDP. A Financial Execution Result Quotient (QREF) was used to measure the fiscal situation of municipalities. The study showed that high personnel expenses negatively impact results. The best results were found in more prosperous economies, with higher GDP per capita [

31].

Fiscal federalism affects the behavior of firms, households, and governments, influencing how they save, spend, or invest. Both firms and households can be attracted by local policies, particularly by the efficiency of the public sector in providing services [

32]. Investments drive local development by improving urban infrastructure, such as local roads and highways, as well as schools and, in some cases, hospitals. This enhances the quality of life and also increases tax collection, thereby generating fiscal sustainability. In OECD countries, the degree of decentralization varies significantly. In 2011, the subcentral share of total spending averaged around 31%, with values ranging from 12% in Israel to 66% in Canada. Expenditure is clearly more decentralized than revenue, resulting in a greater vertical fiscal imbalance and increasing transfers. Studies show that decentralization is positively associated with levels of GDP per capita. Intergovernmental fiscal structures are positively associated with economic activity, human capital, and productivity [

32].

To quantify and assess the response and recovery capabilities after extreme natural events at the country level, the Recovery Gap Index is utilized. This index synthesizes data from three other indices, including sociodemographic, governance, and economic resilience factors. The study revealed that European countries demonstrate strong recovery capacity, while countries in Africa and Asia face substantial challenges. It suggests the adoption of early warning systems and insurance coverage as potential improvements [

33].

The Fiscal Responsibility Law introduced a range of indicators to enhance fiscal management. In addition to those focused on debt- as we have seen, is not a significant factor at the municipal level, other indicators highlight the level of government investment and the capacity to generate savings, reflecting the reductions made in current expenditures. These expenditures have several calculation formats that involve current revenues and current expenditures [

34]. There are four critical factors in management performance through indicators: debt, revenue, public investment, and dependence on constitutional transfers [

34].

In this article, we adopt a method the combination of three indicators: current savings, investment as a percentage of current revenues and the degree of dependence measured by the share of current transfers in current revenues. All these indicators share a common the use of denominator- current revenues. The following equations describe the indicators:

Finally, municipalities are classified as sustainable and capable of taking fiscal action to address climate contingency or not. Note that having a high percentage of investment denotes the capacity to execute expenditure and a long-term vision, since these are not daily expenses. To be classified as suitable, the municipality must commit less than 85% of its current revenues to current expenditures, a criterion similar to CAPAG, and cumulatively it would need to have an investment greater than 10%, a criterion opposite to that applied by the STN in its previous methodology, where investment and financial investments were limited to a percentage of real net revenue for purposes of the fiscal adjustment program. This is justified because, in addition to demonstrating good execution capacity, it shows remaining room for fiscal adjustment. In general, investment is the first expenditure to be subject to budget contingencies due to its flexibility in execution and long-term nature. Finally, as the last criterion, current transfers should account for less than 80% of current revenues, thus measuring the tax autonomy of the entity and its capacity to generate revenues.

4. Results and discussion

The Decree 57,596 of 1 May 2024, declared a state of public calamity in Rio Grande do Sul due to the intense rainfall events that occurred on or after 24 April 2024. The decree also highlights the classification as Level III disasters—characterized by high damage and losses [

35]. Based on SICONFI data, it was possible to evaluate 453 municipalities out of 497, due to the lack of data and a single case due to inconsistency. Of the municipalities in a state of calamity, only 8 (10%) showed aptitude in terms of fiscal sustainability to face climate events, and 79 would not be able to do so (90%). Of those that did not declare a state of calamity, only 77 had adequate budgetary conditions (27%). Of the 453 municipalities evaluated, only 85 would be able to do so, representing 19% (

Table 3).

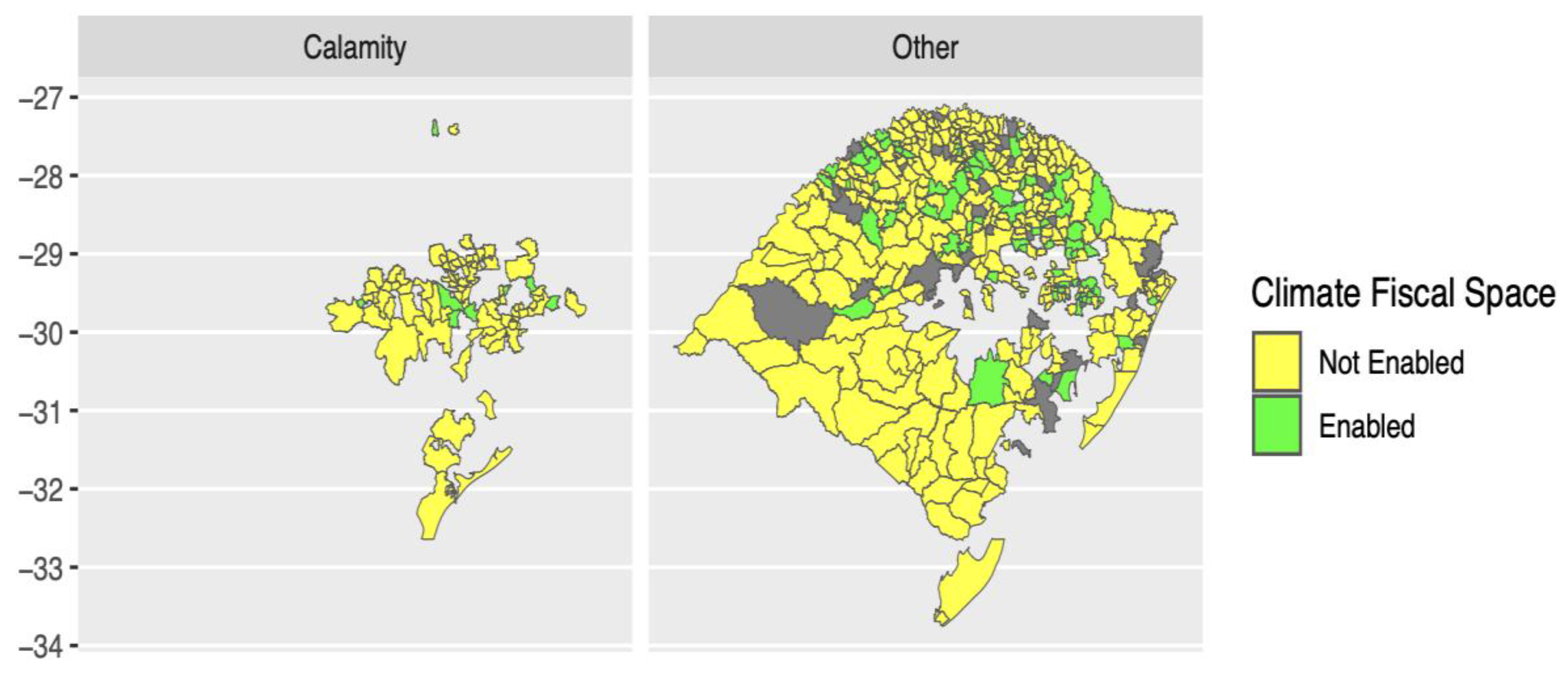

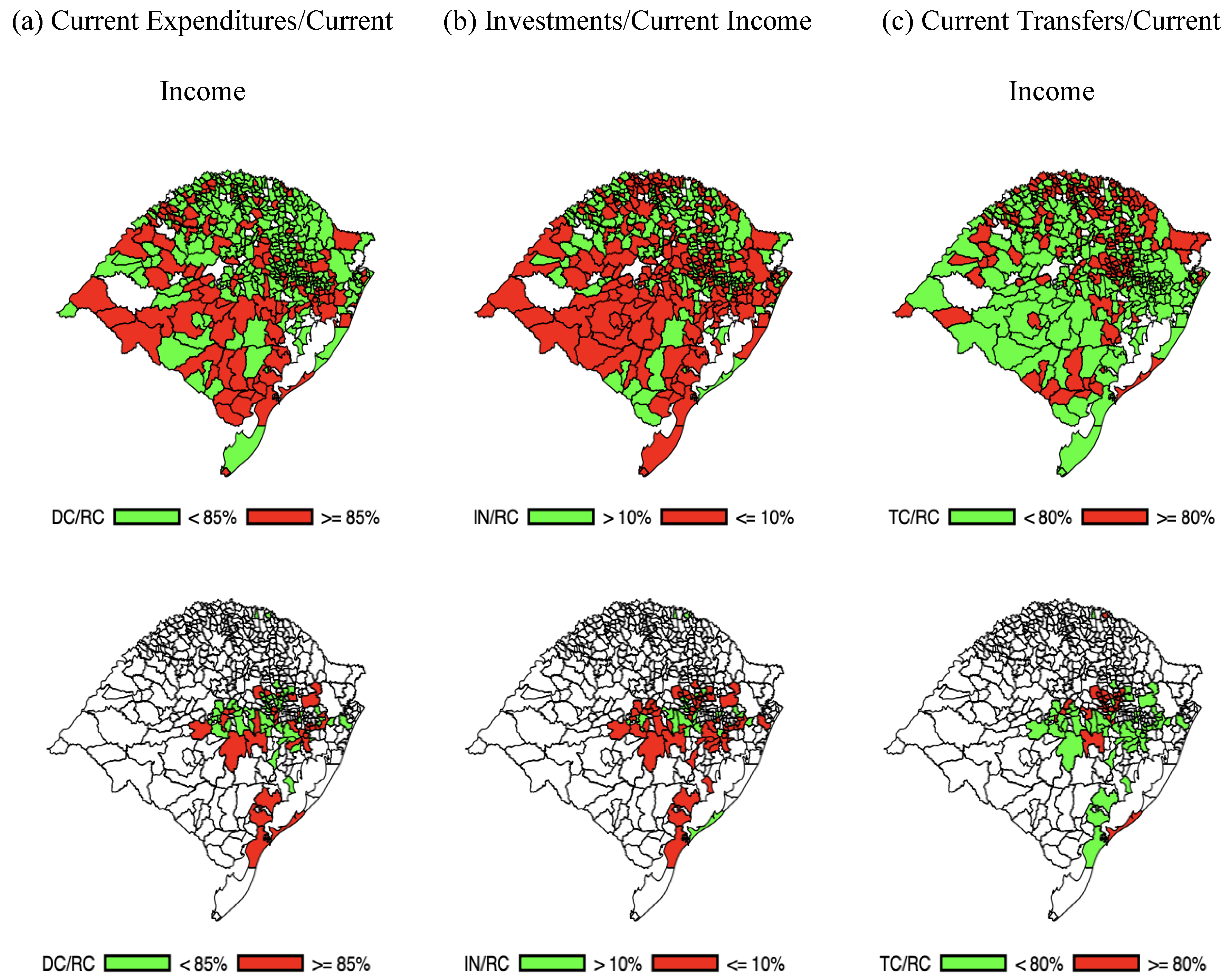

Clearly, this is a limited response capacity given the magnitude of the losses caused by this type of natural disaster. The average investment by municipalities in RS in 2023 was just over BRL 12.3 million, with the largest investment being BRL 512 million from the state capital, Porto Alegre. The maps in

Figure 2 present the fiscal situation of municipalities in RS spatially measured by the proposed indicator and reveal that in fiscal terms the most sustainable municipalities are in the north of the state.

The average current expenditure is 82.3% for all municipalities in RS, with current expenses of 84% in those that are not enabled and 77% in those that are enabled. Another characteristic of enabled municipalities is an average investment of 15%, which is 50% higher than the average for the others, and a lower dependence on transfers (73%). Regarding the percentage of investments, there is no significant difference between municipalities in a state of emergency and the others. The degree of dependence on transfers in general terms is 77%, being lower in both enabled and calamity municipalities (73%). In terms of fiscal characteristics, municipalities in a state of emergency show a low current savings capacity, an average investment slightly below the general level, but a lower dependence on transfers, which indicates a more structured local economy.

Analyzing the fiscal capacity of the 87 out of the 95 municipalities listed in Decree No. 57,646 of 30 May 2024, which reiterates the state of public calamity in the territory of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, we can gain a better view of the possibilities of municipal responses to extreme climate events, which we can call climate fiscal space. These 87 municipalities together have more than 6 million inhabitants, which is equivalent to 55% of the state’s population, which is of 10.8 million inhabitants according to the 2022 census.

The maps in

Figure 3 show the relationship between the commitment of current revenues to current expenditures and, subsequently, the relationship between investments and current transfers in relation to the same reference, which is current revenues. The municipal response capacity will always depend on how much it commits from its current revenues, its main source of resources, and only occasionally receives credit operations or sell assets. It is very common at the municipal level to use its own-source resources to fund investments. The investment grade, in addition to demonstrating a commitment to the future, also represents an additional capacity to implement public policies. The third map provides a visualization of the dependence on transferred resources. It is worth noting that the low percentage of investment in relation to RCL also suggests operational difficulty in its implementation. A high percentage of current transfers shows a significant dependence on transfers from the Union and the State.

The maps show a more favorable situation regarding the criterion of dependence on current transfers, which is somewhat homogeneous throughout the state. However, the performance of current expenses and investments is more favorable in the north. Overall, they illustrate a high commitment to expenditures and a low investment capacity, which can also translate into a limited ability to execute projects.

In relation to the municipalities declared in a state of calamity, 50% of the municipalities recorded expenses committed to investments exceeding 8.8% of Current Revenue. While this is a relevant percentage, it may not translate into a significant amount. Regarding the receipt of transfers from the Union and the State, 25% of the municipalities received transfers above 84.2% of their total current revenue. As for current expenditures, these represent an average 85.1% of current revenue and have a median of 83.4%. If we use the combination of the three criteria as a criterion for fiscal space, where a sustainable municipality would need to not commit more than 85% of its current revenues to current expenses, and cumulatively would need to maintain a minimum investment of 10%, with a dependence on current transfers of no more than 80%, we would have as a result that only the municipalities of Taquari, Vale Verde, Barra do Rio Azul, Rolante, Silveira Martins, Feliz, Venâncio Aires and Gramado would meet the requirements. In short, 8 municipalities out of 87. Some cities do not fully leverage their own tax potential, and unfavorable economic conditions further limit revenue generation due to the economic concentration effects driven by economies of scale. The introduction of the IBS, a new consumption tax, is expected to increase the revenues available to municipalities by adopting the destination principle and broad-based taxation, while also putting an end to tax wars.

Some cities fail to fully leverage their tax potential, but this is compounded by unfavorable economic conditions driven by the natural economic concentration associated with economies of scale. The implementation of the IBS, a new consumption-based tax, is expected to increase municipal revenues through the adoption of the destination principle and broad-based taxation, while also putting an end to the “tax war” between the states. A key challenge, however, lies in the limited capacity for urban planning in many cities. Very small municipalities, in particular, struggle to maintain adequate planning structures. In such cases, it would be beneficial for the state to provide expertise. There is a variety of topics, from urban transportation, solid waste, environmental aspects, sanitation and rainwater.

Both state and municipal schools could also enhance environmental education programs, just as they already participate in tax literacy initiatives. Nevertheless, significant progress is still needed to improve the prevention and response capabilities of civil defense systems at the state and municipal levels. The introduction of the Civil Defense payment card, which can be used at accredited establishments, has already contributed to greater operational efficiency in this process.

In addition to the irreparable loss of life, there are significant economic losses. In the 2008 tragedy in Santa Catarina, with floods and landslides that killed 110 people, the cost was BRL 5.32 billion, with damage to the Port of Itajaí and the Brazil-Bolivia gas pipeline. In a similar event in 2011 in Rio de Janeiro, the death toll was approximately 1000 people in 7 municipalities, at a cost of BRL 4.78 billion, apparently not as significant for the state (1.35% of GDP), but with an impact of 36% of the regional GDP of the mountainous region. In 2010, floods also occurred in Pernambuco and Alagoas, with losses of 4.3% of GDP and 8.7%, equivalent to BRL 3.37 billion and BRL 1.85 billion respectively [

36]. In RS, losses are estimated at BRL 88.9 billion, with a 1.3% reduction in GDP performance [

3]. The evaluation of the BNDES Emergency Program for the Reconstruction of Municipalities Affected by Natural Disasters showed a negative impact on GDP per capita in most of the affected municipalities, lasting up to three years after the events [

37]. As demonstrated, these costs are unsustainable for subnational governments to bear, and it is expected that the costs of catastrophes will be borne mainly by the federal government due to their scale and impact. When such extreme events occur, their destructive power is mitigated—or exacerbated—by the prevention and response capacities of institutions and society. In the context of insurance, “damages” refer to the value of physical assets lost, while “losses” pertain more to the financial consequences of the natural event, such as the interruption of commercial activities.

There is currently no tax dedicated to the prevention of or response to natural disasters. On the contrary, tax exemptions have usually been a form of relief for those affected. The use of specific funds has been adopted, but it is not widespread and faces operational challenges at the local level. A comprehensive solution would require a series of alternative funding sources with different objectives to meet the needs of both prevention and reconstruction. The ex-ante allocation of financial protection can rely on budgetary reserves across all three levels of government entities, contingency credit operations and even insurance. It can rely on the issuance of catastrophe bonds.

There is no comprehensive understanding of how disasters affect government budgets. The Brazilian government relies primarily on ex-post financing mechanisms [

36]. Brazil has opted for the budgetary approach. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, a special Development Policy Loan was approved and disbursed for the reconstruction of the mountainous region.

The World Bank’s risk stratification approach is based on the frequency and severity of the event, and for medium-risk events such as floods or small earthquakes, the use of contingent credit is recommended. In high-risk scenarios, insurance solutions or catastrophe bonds can be developed to mitigate potential losses [

36]. An event like the one in Rio Grande do Sul, lasting over a month, would likely require at least a first line of defense: a budget supported by a dedicated financial fund, potentially shared among the states and municipalities of the affected region. This would be supplemented by a contingent reconstruction credit to address recovery needs.

In Rio Grande do Sul (2010), Santa Catarina (1990), and Minas Gerais (1977), specific disaster funds have been established, as they also have at the federal level. Additionally, cities like Belo Horizonte, Florianópolis, Blumenau, Itajaí, São Leopoldo, Caxias do Sul, and Novo Hamburgo, among others, maintain their own funds, though these cases remain the exception rather than the norm [

36].

The year 2023 was a historic milestone for Brazil, as it aligned bond issuances with sustainability. First, the guidelines for sovereign debt issuances were presented. These initiatives support public expenditures that promote sustainability, mitigate climate change, conserve natural resources, and contribute to social development. On 13 November 2023, the National Treasury issued the first sustainable sovereign bond on the international market worth USD 2.0 billion and announced plans to maintain a regular presence in the sustainable bond market according to the 2023 Annual Public Debt Report. Issuances by national and supranational entities reached USD 405 billion in 2023, an increase of 15.3% compared to 2022 [

38].

5. Conclusions

The issue of disasters is not new to many countries that face hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, droughts, tsunamis, earthquakes, and occasionally human-induced nuclear disasters. This article evaluates the fiscal sustainability through budgetary indicators of municipalities in Rio Grande do Sul (RS), aiming to explore the concept of climate fiscal space. To do so, we use an indicator that examines the allocation of current revenues to current expenses and investments, as well as the degree of fiscal autonomy. The results reveal the limited availability of local governments to fully bear the responsibility for adapting to and mitigating climate disasters. For example, only 10% of municipalities severely affected by the 2024 floods have some budgetary capacity, albeit highly constrained. At the state level, just 19% of municipalities in RS exhibit any fiscal space.

In 2023, the total committed investment across 453 evaluated municipalities amounted to approximately BRL 5.6 billion. As for the finances of the state of RS, while there are evident improvements in its fiscal position, uncertainty remains regarding the sustainability of budgetary balance in the medium term. Additionally, the state’s debt burden remains significant, leaving little room for further borrowing. RS currently allocates annual investments equivalent to about 5% of its Net Current Revenue (RCL), amounting to BRL 3.0 billion [

39]. However, these amounts provide limited capacity to respond to disasters, which typically require resources equivalent to 1% to 5% of GDP. For RS, this translates to a range of BRL 6.4 billion to BRL 32 billion (2023). In summary, while the allocated amounts are substantial, they fall short of the necessary levels. The fiscal constraints faced by municipalities is also mirrored in the state’s financial limitations.

The data suggest that economic activity and revenue recovery at a rapid pace. However, the associated disruptions—loss of human lives, psychological trauma, damage to public infrastructure, and destruction of private assets—must be prevented. Drawing on the literature and specialized reports, we propose two distinct sources of financing to support permanent prevention efforts and the transformation of Rio Grande do Sul (RS) into an urban and rural structure that promotes economic, social, and environmental sustainability.

The first source, focused on prevention and rapid mitigation, would fund the development of planning, monitoring, and ongoing actions for reconstruction, adaptation, and infrastructure maintenance. It would also support the integration of civil defense systems, personnel training, and the simulation of disaster scenarios by public entities. This fund would be financed through contributions from all three levels of government, allocated based on their share of national revenues: 50% from the federal government, 30% from the state, and 20% from municipalities. Management of the fund would be integrated along these three contributors, while its execution would be carried out by state and local authorities. To strengthen the fund, existing resources from privatizations deposited in the State Reform Fund and in the Rio Grande Plan Fund (FUNRIGS), established under Law No. 16,134/2004 [

40], both could be utilized.

The second funding source would focus on addressing extreme events, which remain a persistent global issue that transcends territorial boundaries. This fund would finance large-scale investments in the prevention and response to severe crises. It would be anchored in sustainable bonds issued by the federal government, leveraging its participation in this market since 2023. Execution of these resources would be managed within the federal budget, with the option for delegation. The second fund would function as a sovereign climate event fund, capable of receiving additional resources from multilateral organizations and incorporating risk-mitigation mechanisms such as insurance. Establishing a dedicated state agency for urban development planning and the prevention of extreme events is critical for ensuring long-term preparedness and resilience. The main limitation of this study is the short time frame since the event. Future research could explore the effects of flooding on business survival and economic sectors, as well as conduct demographic and productivity analyses to better understand the long-term impacts.