1. Introduction

The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) is increasingly recognized as a vital component of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), driving advancements in efficiency and intelligence [

1]. At the core of IoV are in-vehicle networks (IVNs), which comprise numerous Electronic Control Units (ECUs) that communicate through the Controller Area Network (CAN). The CAN protocol, widely adopted for its broadcast capabilities, efficient data transmission, and cost-effectiveness, forms the backbone of these networks. However, despite its widespread use, the CAN protocol is frequently criticized for its inherent lack of security mechanisms, such as authentication, encryption, and segmentation. These limitations expose it to significant vulnerabilities, making it a prime target for cyberattacks [

2]. Attackers can exploit various interfaces, including USB ports, Bluetooth connections, and onboard diagnostic (OBD)-II ports, to gain unauthorized access to IVNs. Once an entry point is compromised, they can inject malicious messages into the network, facilitating a range of attacks that threaten both vehicle safety and user privacy [

3].

Intrusion detection systems (IDSs) have demonstrated their effectiveness in addressing these challenges [

4]. While traditional IDSs rely heavily on regular updates to databases of known attacks, a limitation that is well recognized, recent research has increasingly shifted towards machine learning-based IDSs. These systems offer high accuracy and adaptability to a wide range of attack types [

5,

6]. However, most existing works fail to address the need for rapid adaptability across diverse attack scenarios. They typically rely on models trained on large, static datasets, which hinders their ability to adapt quickly to new or evolving attack environments [

7,

8].

Quickly adapting to various attack scenarios for intrusion detection can be framed as a few-shot learning problem. Meta-learning has emerged as an effective approach to address it [

9]. Among the various meta-learning frameworks, Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML), introduced by Finn et al., is an optimization-based method that has been successfully applied to classification, regression, and other tasks in few-shot scenarios [

10]. MAML aims to learn an optimal set of initial model parameters (meta-parameters), which enables rapid adaptation to new tasks through a dual optimization process involving inner-level and outer-level updates [

15]. To mitigate the high computational and memory overhead associated with the second-order gradient calculations in MAML, we employ First-Order MAML in this work.

While meta-learning provides a promising approach for enabling IDSs to quickly adapt to various attack scenarios, it faces limitations when applied across data from different vehicle manufacturers, potentially hindering its generalization to more complex attack scenarios. Beyond business considerations, manufacturers may be reluctant to share their data due to stringent data protection regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), introduced in 2017. These regulations impose strict constraints on data aggregation and usage [

12]. Specifically, as vehicle owner information collected by manufacturers may include sensitive details, aggregating communication traffic data raises significant privacy concerns, often resulting in data silos. Additionally, differences in vehicle configurations and communication protocols across manufacturers can lead to non-independent and identically distributed (Non-IID) data, further complicating the application of traditional meta-learning techniques [

13].

To address these challenges, we propose the Personalized Federated Meta-Learning Intrusion Detection System (PFMeta-IDS). At the core of this system is a novel personalized federated meta-learning algorithm, PFMetaSWR, which employs a similarity-weighted aggregation mechanism. This algorithm aggregates personalized global meta-parameters for each manufacturer by weighting updates uploaded by manufacturers to a central aggregator. Within this framework, the aggregator orchestrates the process, while each manufacturer functions as a client, updating its local meta-parameters using First-Order Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning. A regularized loss function is introduced to enable the local models, to partially learn from the personalized global model and its corresponding global meta-parameters. This design effectively balances personalization and generalization. Additionally, each local model is capable of rapidly adapting to diverse attack scenarios through few-shot learning on training datasets tailored to those scenarios. Beyond addressing the challenge of quick adaptation to various attack scenarios in IDSs for IVNs, PFMeta-IDS further enhances the generalization capabilities of IDSs while maintaining data privacy across different manufacturers. The main contributions of our work are summarized as follows:

- 1)

We propose a Personalized Federated Meta-Learning Intrusion Detection System (PFMeta-IDS) designed to rapidly adapt to diverse attack scenarios and accurately detect intrusions, all while preserving data privacy across different manufacturers.

- 2)

We introduce a novel Personalized Federated Meta-Learning algorithm, FedSWR, which enables the central aggregator to aggregate personalized global models for each client and facilitates the training of personalized local models at each client. These local models learn partially from the personalized global models, ensuring a balance between generalization and personalization.

- 3)

We propose a novel feature engineering method, KMCS-IG, which integrates k-means-based cluster sampling (KMCS) with the Information Gain (IG) method to enhance feature selection and representation.

- 4)

We evaluate the performance of PFMeta-IDS using a novel fundamental model that we constructed, LDwCBN, conducting experiments on the state-of-the-art dataset, Car-Hacking dataset. The results demonstrate its quick adaptability to various attack scenarios, achieving high accuracy and F1-score compared with existing works.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the related work.

Section 3 presents the detailed design of PFMeta-IDS,

Section 4 shows experimental results, followed by conclusions in

Section 5.

2. Related Works

The field of IDS for automotive has seen significant advancements in recent years. This section aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the key areas related to our research. We first review the state-of-the-art works in machine learning-based intrusion detection systems tailored for automotive networks. Next, we explore the application of federated learning within Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS). Finally, we discuss the role of meta-learning in enabling rapid adaptation to diverse scenarios and summarize its limitations.

2.1. Machine Learning-Based IDSs for Automotive

With the advancements in Machine Learning (ML) techniques, research on ML-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) has seen significant growth in recent years due to their remarkable performance [

16]. ML-based IDSs can generally be categorized into traditional ML-based IDSs and Deep Learning (DL)-based IDSs.

Traditional ML-based IDSs often employ fundamental algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs), tree-based models, gradient boosting, and probabilistic classifiers like Naive Bayes. Al-Saud et al. [

17] proposed an OCSVM-based Anomaly Detection Model (ADM), which optimizes the parameter settings for SVM and uses ID frequencies as features for detection. Kalkan et al. [

18] demonstrated the excellent performance of a Decision Tree (DT)-based model on the Car-Hacking dataset. Similarly, Anjum et al. [

19] employed Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) to classify unexpected events in CAN data payloads, achieving high accuracy across different attack scenarios. Islam et al. [

20] introduced the Graph-Based Gaussian Naive Bayes (GGNB) algorithm, which incorporates graph properties and PageRank-related features to identify a wide range of attack types. Nair et al. [

21] utilized blockchain to store traffic data in a decentralized manner while employing the Gaussian Naive Bayes algorithm to analyze CAN traffic properties, classifying communication windows as normal or abnormal.

Deep Learning (DL)-based IDSs have shown significant potential to achieve superior performance compared to traditional methods. Baldini et al. [

22] employed a bag-of-words methodology to identify intrusions in in-vehicle networks (IVNs), leveraging the sequential patterns of CAN data to detect atypical behavior. Song et al. [

5] introduced a Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN)-based IDS, which utilized specific properties to protect the CAN bus against cyber threats. Their results demonstrated that the DCNN model outperformed baseline methods across all attack types. Boumiza et al. [

23] proposed an IDS using Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) with Rectified Linear Units (ReLU) activation functions. This approach avoids saturation and promotes better gradient flow, enhancing the model’s learning capabilities. Their evaluation showed superior performance compared to existing algorithms. Fenzl et al. [

24] presented a continuous field classification algorithm to detect misaligned payload values, followed by a DL methodology to identify atypical fields. Their work highlighted the effectiveness of genetic programming for capturing complex relationships between sensor values, which are critical for classifying targeted attacks. Additionally, Kang et al. [

25] proposed the NaDS framework, which combines Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). Synthetic frames generated by the GAN were used to train the LSTM. Their experimental results demonstrate that NaDS significantly enhances abnormal message detection accuracy compared to existing methods.

2.2. Federated Learning in ITS

The development of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) has significantly enhanced urban traffic information, improving daily convenience, road efficiency, and sustainable urban living. However, many existing ITS applications rely on a centralized training approach that requires a cloud server with substantial computing power for management and centralized training [

26]. This centralized framework faces several limitations, including poor real-time performance, data silos, and challenges in ensuring data privacy.

To address these issues, federated learning (FL) has emerged as a promising alternative, gaining widespread attention due to its strong privacy-preserving capabilities and scalability. Jallepalli et al. [

27] demonstrated through simulations that the FL architecture can identify detection targets that are unrecognizable through local training on a single vehicle. Zhou et al. applied the hierarchical structure of FL within ITS to achieve superior training results in vehicle object recognition scenarios supported by 6G technology. Liu et al. [

28] utilized FL for power line image detection tasks using the YOLO v5 model, showing that FL training across multiple power companies produces models with higher detection accuracy compared to locally trained models. Additionally, Gao et al. [

29] proposed an FL-based method for vehicle position inference in closed areas, leveraging GPS data trained in open environments. Zou et al. [

30] introduced a novel approach for urban UAV charging services by integrating FL with LSTM and stochastic game theory. Their findings highlight the superiority of this combined method, which achieved the lowest mean squared error and the highest energy satisfaction compared to benchmark approaches.

2.3. Application of Meta-Learning

Traditional AI learning methods often require large volumes of data to solve specific tasks, which can be impractical in scenarios where quick adaptation is crucial. To address these challenges, approaches like meta-learning and transfer learning have emerged as promising solutions. However, as demonstrated by Howard et al. [

31], transfer learning via fine-tuning may not always be effective, especially when the target task dataset is very small or significantly different from the source tasks. In contrast, meta-learning offers the ability to learn a set of meta-parameters that enable efficient adaptation to new tasks with limited data by leveraging prior knowledge from related tasks [

32].

Meta-learning has been applied successfully across diverse domains. Ruswurm et al. [

33] implemented few-shot land cover classification using the Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) algorithm on classification and segmentation tasks with globally and regionally distributed datasets. Their findings demonstrated that few-shot model adaptation outperforms standard pre-training with gradient descent and fine-tuning, particularly when the source and target domains differ. Wu et al. [

34] proposed PROTOTRANSFORMER, where a meta-learner provides feedback to student code on new programming questions with only a few annotated examples. Nguyen et al. [

35] explored the transferability of graph neural network (GNN) initializations learned via meta-learning for chemical property and activity prediction tasks. Their results showed that meta-learned initializations performed comparably to or better than multi-task pre-training baselines across most in-distribution tasks and all out-of-distribution tasks. In another application, Yu et al. [

36] utilized a meta-learning algorithm to develop a highly transferable driving speed prediction model based on the visual road environment. Their experimental results demonstrated significantly high prediction accuracy, even with small sample sizes or when applied to new scenarios. However, the meta-learning methods used in existing works lack collaborative learning and data privacy protection.

Although existing Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) for vehicular networks have demonstrated high detection accuracy, they predominantly rely on learning methods trained on large datasets. This reliance limits their ability to quickly adapt to dynamic and evolving attack scenarios. To address these limitations, we proposed PFMeta-IDS, a system that integrates meta-learning with FL to enable rapid adaptation to various attack scenarios while maintaining strong generalization and ensuring data privacy across manufacturers.

3. Proposed PFMeta-IDS Framework

This section introduces the PFMeta-IDS framework, starting with an overview of its system architecture, followed by the FedSWR algorithm, data preprocessing, and the LDwCBN network. At its core, PFMeta-IDS relies on meta-models, defined by meta-parameters optimized for rapid adaptation across diverse tasks. Both global and local models are trained and updated based on these meta-parameters.

3.1. System Architechture

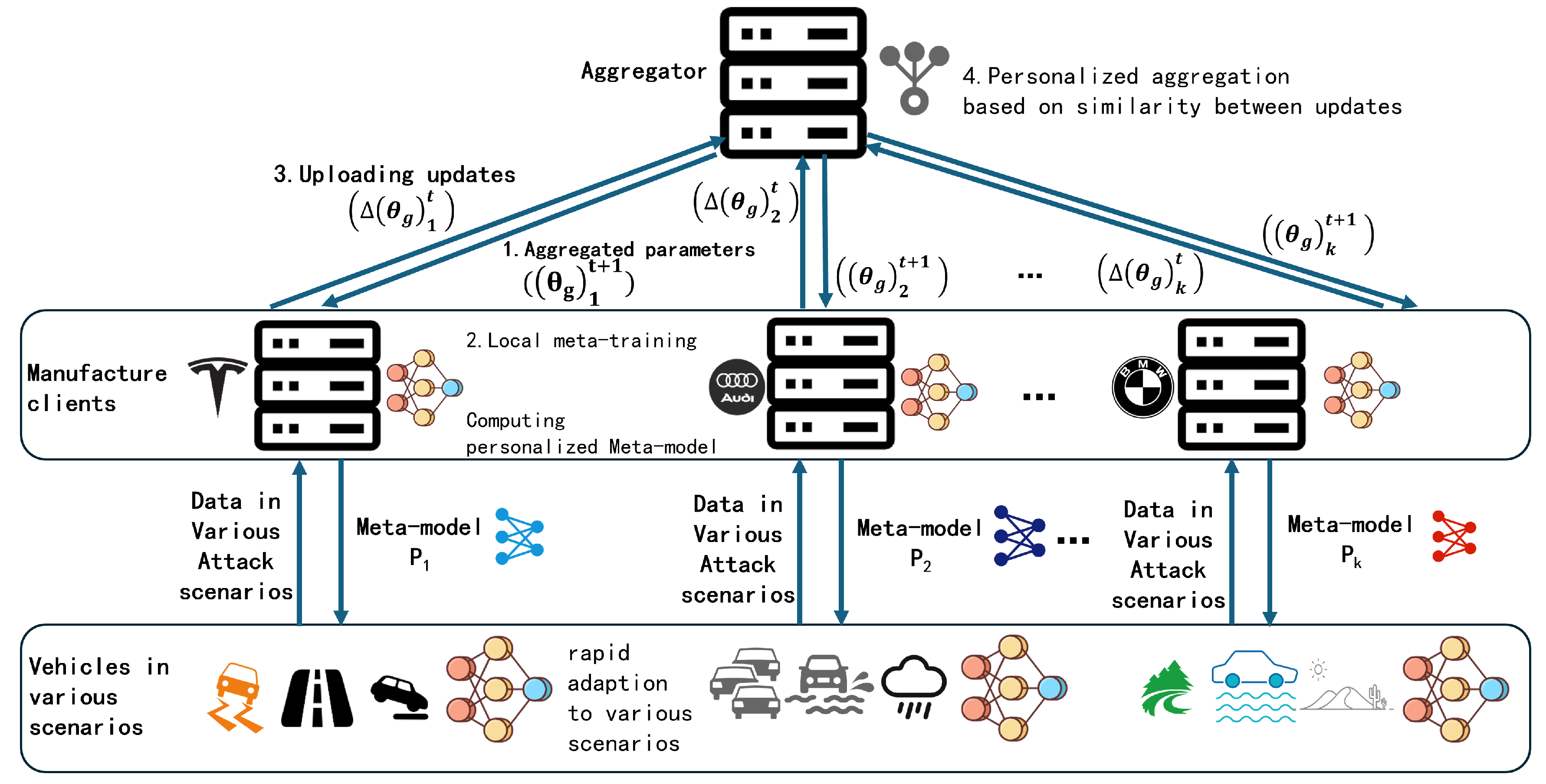

The proposed PFMeta-IDS architecture, illustrated in

Figure 1, comprises three interconnected layers: the central aggregator layer, the manufacturer client layer, and the vehicle layer. This multi-layered design facilitates collaborative learning while ensuring data privacy and adaptability in intrusion detection.

At the Aggregator layer, the central aggregator layer serves as the coordination hub for the federated meta-learning process. Using the FedSWR algorithm, the aggregator performs similarity-weighted aggregation of meta-model updates received from manufacturer clients. The resulting personalized global meta-models are then distributed back to the clients, enabling them to enhance their local training processes. This layer promotes cross-client knowledge sharing while preserving data privacy, thereby improving the generalization capability of the models.

The Manufacturer Client layer represents manufacturers such as Tesla, Audi, and BMW. Each client retains its local data and computational resources, conducting local meta-training on task sets derived from its Non-IID dataset. These local meta-models partially learn from the personalized global meta-model, creating personalized local meta-models specific to the unique vehicular scenarios of each manufacturer. This personalized approach addresses the diversity in vehicular communication protocols and attack patterns across manufacturers.

The vehicle layer represents individual vehicles operating in diverse environments, including highways, urban traffic, and extreme weather conditions. Vehicles employ the updated local meta-models for scenario-specific intrusion detection, adapting rapidly to various attack scenarios through few-shot learning on relevant datasets. This layer ensures that intrusion detection systems remain effective in dynamic and evolving real-world contexts.

3.2. FedSWR Algorithm

The

Federated Similarity-Weighted Regularization (FedSWR) algorithm is a core component of the proposed PFMeta-IDS framework. It integrates principles of federated learning with a similarity-based weighting mechanism to balance personalization and generalization. The iterative process of the algorithm is outlined in Algorithm 1, executed collaboratively by a central aggregator and multiple distributed clients. This approach ensures data privacy while facilitating effective model updates.

|

Algorithm 1 PFMetaSWR |

- 1:

Server Executes: - 2:

for do

- 3:

for each client do

- 4:

- 5:

end for

- 6:

compute similarity-based weighting matrix according to Eqs. (6), (7), (8) - 7:

for each client do

- 8:

- 9:

The server aggregates the personalized models based on the similarity weights and distributes them to client k

- 10:

end for

- 11:

end for - 12:

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ - 13:

ClientUpdate

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

for epoch do

- 17:

for each batch of tasks from task distribution do

- 18:

for each task do

- 19:

Split data for task into support set and query set

- 20:

Evaluate task-specific loss on support set

- 21:

Compute gradients on support set

- 22:

Update task-specific parameters:

- 23:

Evaluate task-specific loss on query set

- 24:

Compute gradients w.r.t. parameters on the query set

- 25:

Sum batch gradients:

- 26:

end for

- 27:

Update meta-parameters using total batch gradients: - 28:

- 29:

for each task do

- 30:

Split data for task into support set and query set

- 31:

Evaluate task-specific loss on support set

- 32:

Compute gradients on support set

- 33:

Update task-specific parameters:

- 34:

Evaluate task-specific loss on query set

- 35:

Compute gradients w.r.t. parameters on the query set

- 36:

Sum batch gradients:

- 37:

end for

- 38:

Update meta-parameters using total batch gradients: - 39:

- 40:

end for

- 41:

end for - 42:

- 43:

return

|

At each communication round, the central aggregator receives updates from all clients and aggregates them using a similarity-weighted matrix

S, computed with Equations

1,

2,

3. The matrix quantifies the similarity between client updates using cosine similarity, which measures the alignment of update directions. These similarity scores are normalized into weights

, determining each client’s contribution to the personalized global meta-model parameters. The central server applies these weights to update the global meta-parameters, as described by Equation

4, where

(is set to 0.01) represents the learning rate. Once updated, the personalized global meta-models are distributed back to the clients to enhance their local training processes.

Each client performs local training using its private dataset, which is typically Non-IID. The training involves a bi-level optimization process:

- 1)

Global Meta-Model Update: The global meta-parameters

are optimized using the loss function

defined in Equation

5. This process enables task-specific learning from a global perspective.

- 2)

Personalized Local Meta-Model Update: Clients update their local meta-parameters

using the loss function

, defined in Equation

6. This function includes a regularization term controlled by

, which dictates the extent to which the local meta-model learns from the global meta-model.

After completing local training, clients compute the updates for global meta-parameters and personalized local meta-parameters . These updates are then sent back to the aggregator for the next communication round.

The personalized local meta-models are deployed to vehicles, enabling rapid adaptation to diverse attack scenarios through few-shot learning on small datasets. This ensures efficient and dynamic intrusion detection tailored to specific vehicular environments.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

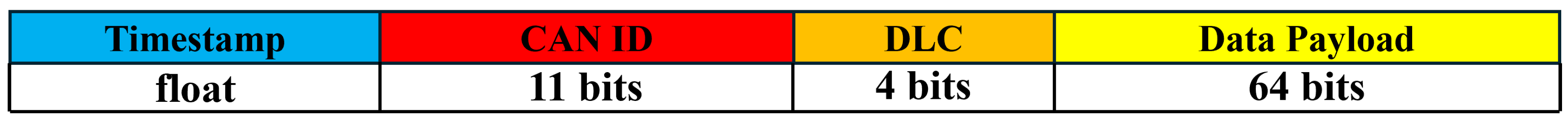

Effective data preprocessing is essential for the success of intrusion detection systems in automotive networks. As shown in

Figure 2, each CAN message in the dataset consists of four fields: Timestamp, CAN ID, DLC, and Data Payload. The CAN ID determines the priority of the message, where smaller values represent higher priority. The DLC field indicates the length (in bytes) of the Data Payload, which contains the actual information exchanged between nodes.

This section outlines the preprocessing methods employed to optimize the raw CAN messages for intrusion detection tasks. Specifically, we describe the Frame Converting approach used to transform raw data into an analyzable format and the Feature Engineering techniques designed to extract and select meaningful features for improved detection performance.

3.3.1. Frame Converting

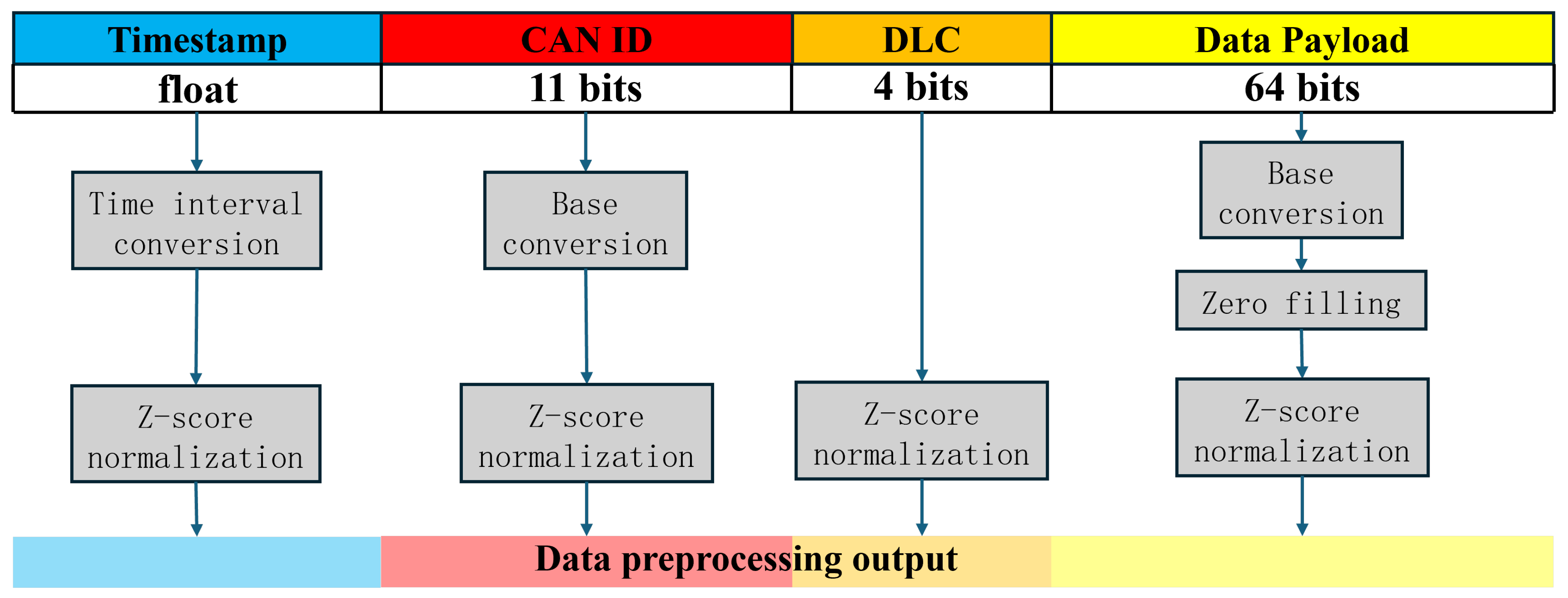

The conversion process for each CAN message in the dataset is illustrated in

Figure 3. The raw data is preprocessed to remove biases and inconsistencies, ensuring its suitability for intrusion detection tasks. This process involves the following steps:

- 1)

Timestamp Transformation: To eliminate the potential bias introduced by the strong correlation between the timestamp and the attack cycle, each message’s timestamp is replaced with the time interval between the current and the previous message. This transformation focuses on relative timing rather than absolute values, enhancing the robustness of the detection model.

- 2)

CAN ID Conversion: The CAN ID, which determines the priority of the message (with smaller IDs having higher priority), is converted from hexadecimal to decimal format. This conversion simplifies numerical computations and ensures consistency across the dataset.

- 3)

-

Data Payload Processing: The Data Payload, containing the transmitted information, undergoes two critical preprocessing steps:

- 4)

Z-score Normalization: Finally, all features of each message in the dataset are normalized using the Z-score method. Normalization plays a critical role in standardizing the dataset, ensuring that features are on a consistent scale. By rescaling data to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, normalization reduces the influence of varying feature scales on model performance and accelerates the convergence of learning algorithms. The normalization formula is given by Equation

7:.

where

denotes the original feature value,

is the mean of the feature values, and

is their standard deviation.

3.3.2. Feature Engineering

Effective feature engineering plays a critical role in improving the quality of datasets, enabling more accurate and efficient model learning. To achieve this, the proposed system employs a comprehensive feature engineering method, KMCS-IG, which combines K-Means Clustering Sampling (KMCS) and Information Gain (IG). This approach eliminates irrelevant, redundant, and noisy features while retaining the most important ones.

Analyzing large-scale network traffic data is often impractical due to the computational cost, especially during hyperparameter tuning, which involves processing multiple large datasets from diverse attack scenarios [

38]. To enhance efficiency, data sampling is applied to reduce the dataset’s size without losing critical information.

The proposed system employs a

k-means-based cluster sampling (KMCS) method to obtain a highly representative subset of the original dataset. Cluster sampling groups data points into clusters, and a proportion of data is sampled from each cluster to form a subset. Unlike random sampling, which selects samples with equal probability, cluster sampling focuses on retaining diverse and representative data points, discarding mostly redundant ones. Among clustering algorithms,

k-means is widely used due to its simplicity and computational efficiency [

39].

In k-means clustering, data points are grouped into

k clusters based on distance metrics such as Euclidean, Manhattan, or Mahalanobis distance. The algorithm minimizes the sum of squared distances between data points and their cluster centroids, as shown in Equation

8:

where

is the data matrix,

is the centroid of cluster

, and

is the total number of points in

.

After clustering, random sampling is applied to each cluster, selecting 10% of the data as the representative subset. This percentage can be adjusted based on the dataset’s scale and resource constraints.

To refine the dataset further, the

Information Gain (IG) method is used to select the most important features. IG quantifies the amount of information a feature contributes to predicting the target variable by measuring the change in entropy [

41]. IG is computationally efficient, with a complexity of

, making it suitable for large datasets. The IG value for a feature

X with respect to the target variable

T is calculated as:

where

is the entropy of the target

T, and

is the conditional entropy of

T given

X.

The IG value represents the importance of feature X in predicting T. A feature X is considered more important than another feature Y if .

To implement the IG-based feature selection:

- 1)

The importance of each feature is calculated using Equation

9.

- 2)

The importance values are normalized to sum to 1.0, representing their relative significance.

- 3)

Features are ranked by their importance, and the top features are selected until their cumulative importance reaches a correlation threshold , set to 0.9 in this work.

- 4)

Features with a total importance less than are discarded as less relevant.

By combining KMCS and IG, the KMCS-IG method ensures that the feature-reduced dataset remains both representative and informative, enabling efficient and accurate meta-model training.

3.3.3. Class Balancing in Task

Class imbalance is a common issue in network traffic data, as normal samples often significantly outnumber attack samples in real-world scenarios. This imbalance can result in biased models and poor accuracy when detecting minority class samples [

43]. To address this, the

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) is employed, as it is widely regarded as an effective method for handling class imbalance [

44,

45]. SMOTE generates high-quality synthetic instances based on the k-nearest neighbors (KNN) of existing minority class samples.

In the proposed IDS, SMOTE is applied to handle class imbalance for every client at two levels:

- 1)

Across the entire dataset for each training task.

- 2)

Within the training dataset for each test task.

For a minority class instance

, SMOTE generates a new synthetic instance

by selecting a sample

randomly from the

k-nearest neighbors of

. The new instance

is calculated using Equation

10:

3.4. LDwCBN Network Structure

The

Lightweight Depthwise Convolutional Bottleneck Network (LDwCBN) is a 1D deep learning architecture derived from the LW-CNN structure [

42], designed to process preprocessed 1D data frames for anomaly detection tasks. While preserving the lightweight nature of LW-CNN, LDwCBN incorporates key enhancements, such as

Batch Normalization (BN) and

ReLU6 activation layers, to improve training stability and generalization without significantly increasing computational complexity. These design considerations were driven by the need to deploy the model in automotive environments, where computational and storage resources are highly constrained.

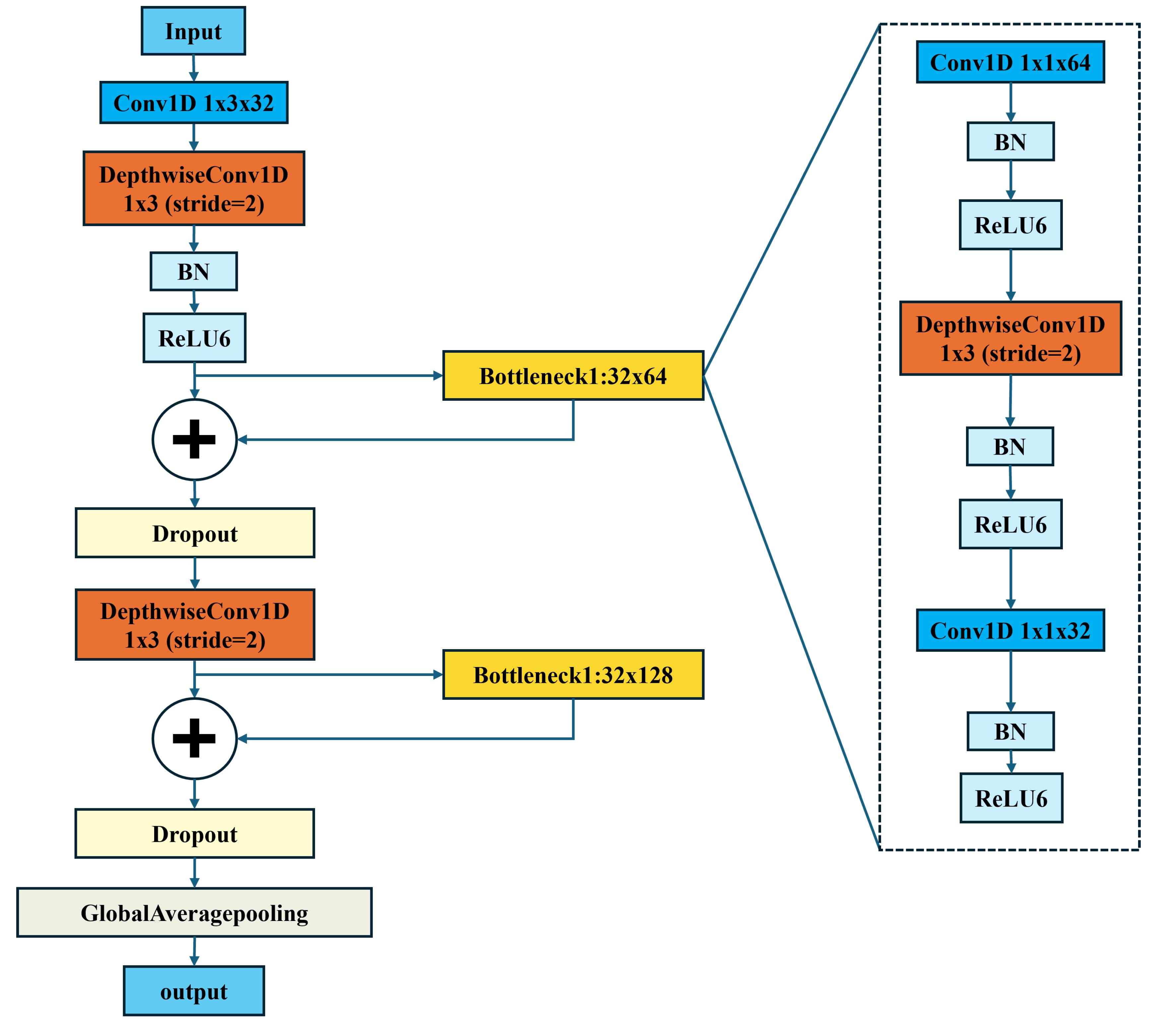

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the LDwCBN network backbone consists of a standard 1D convolutional layer, two depthwise convolutional layers, and two bottleneck structures with residual connections. These residual connections enhance trainability and mitigate the degradation problem commonly encountered in deep networks.

To ensure consistency and efficiency, all computational units produce an output with 32 channels. The network starts with a 1D standard convolutional layer, which expands the channel dimension to 32. Depthwise convolution with a stride of 2 is used to reduce feature dimensions. The first depthwise convolutional layer (dwconv1) is enhanced with BN and ReLU6 layers, stabilizing training and accelerating convergence. Subsequent bottleneck structures consist of two pointwise convolutions and one depthwise convolution, interleaved with BN and activation layers. These bottleneck structures handle channel dimension transitions, specifically from 64 to 32 and from 128 to 32.

ReLU6 activation is used throughout the network due to its limited output range, making it particularly well-suited for resource-constrained embedded platforms. Additionally, global average pooling (GAP) replaces fully connected layers, efficiently summarizing feature information by computing the global average of each channel. GAP significantly reduces the number of parameters and computational overhead, making it ideal for real-time classification tasks. Finally, the network employs a Sigmoid function for binary classification to detect attacks.

4. Performance Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Settings and Datasets

To implement the proposed PFMeta-IDS framework, data processing and meta-learning algorithms were developed using the Pandas [

46], Scikit-learn [

47], and PyTorch [

48] libraries in Python.

1 The experiments were conducted on a server equipped with an AMD EPYC 7542 (32-Core, 2.90 GHz) CPU, 256 GB of memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU.

The experiments utilized the established Car-Hacking dataset [

5], a benchmark dataset in vehicular network security. This dataset, extensively used in automotive security research, includes four types of attacks: DoS, Fuzzy, RPM Spoofing, and Gear Spoofing [

49]. The dataset is based on real-world traffic data, offering practical insights and enabling direct comparison with existing works using the same dataset.

Each CAN message in the dataset contains valuable attributes: Timestamp, CAN ID, DLC, Data Payload, and a flag indicating whether the message is normal or an attack. The features used (Timestamp, CAN ID, DLC, Data Payload) are described in

Section 3.3.

Table 1 summarizes the statistics for each traffic type.

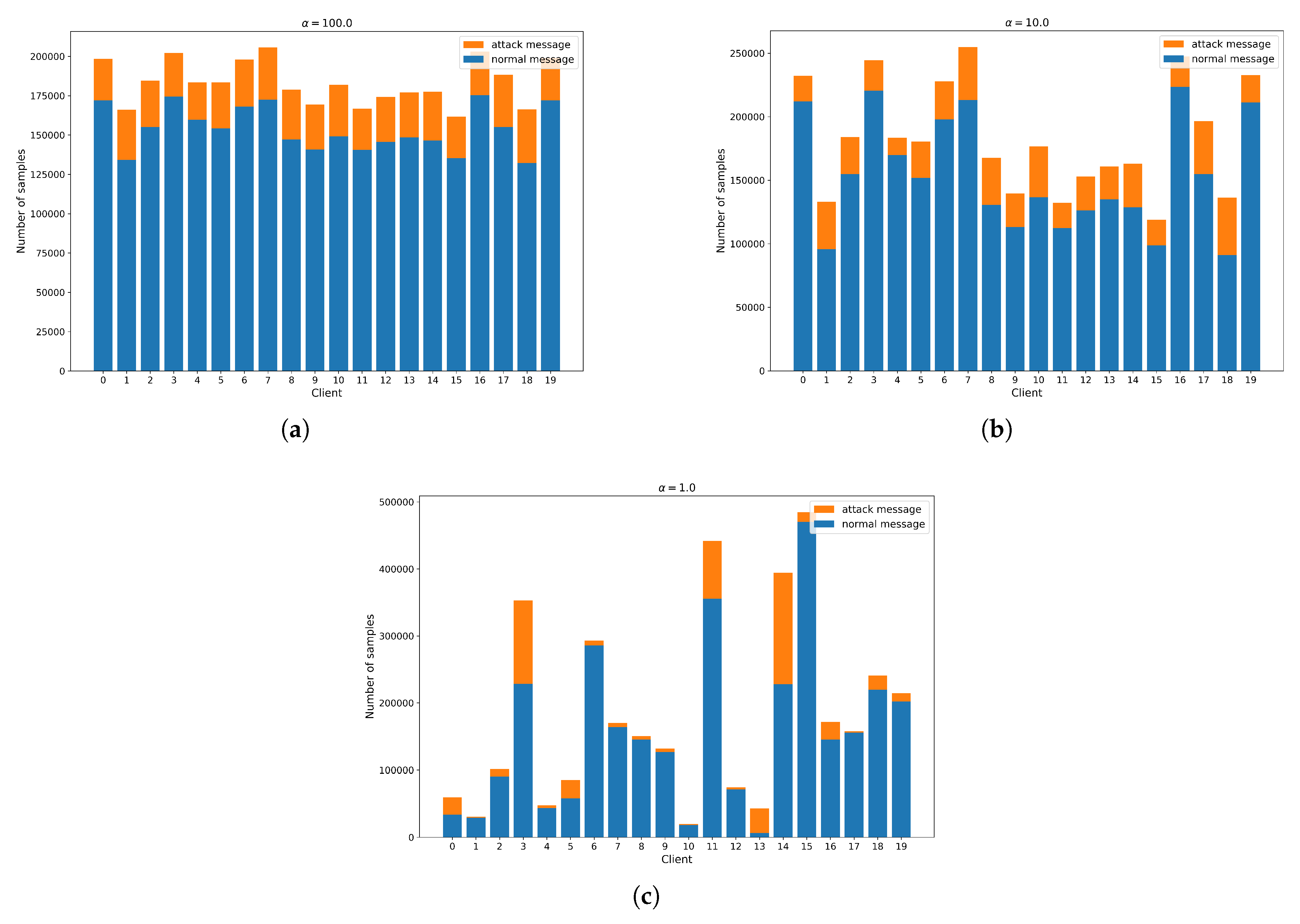

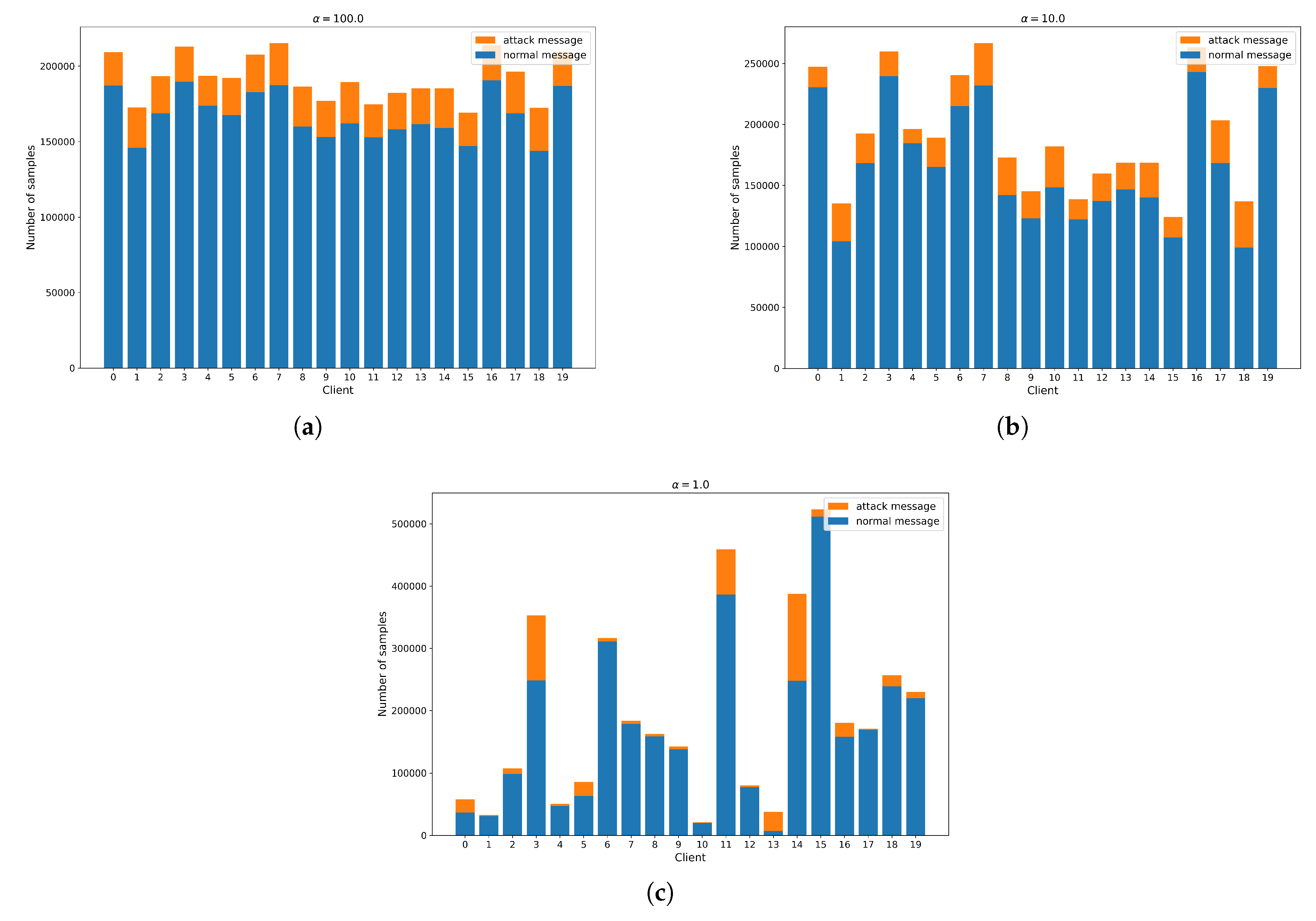

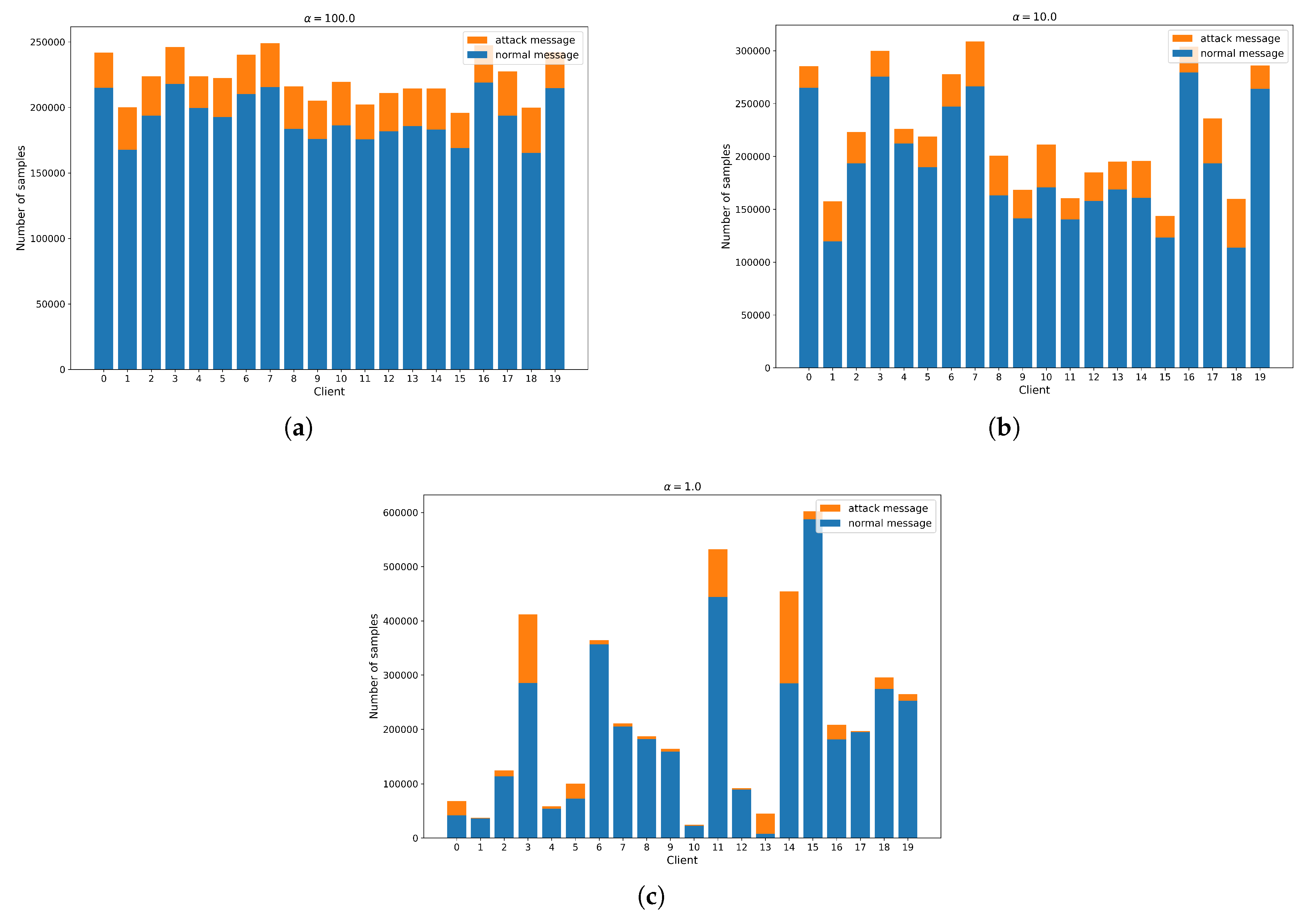

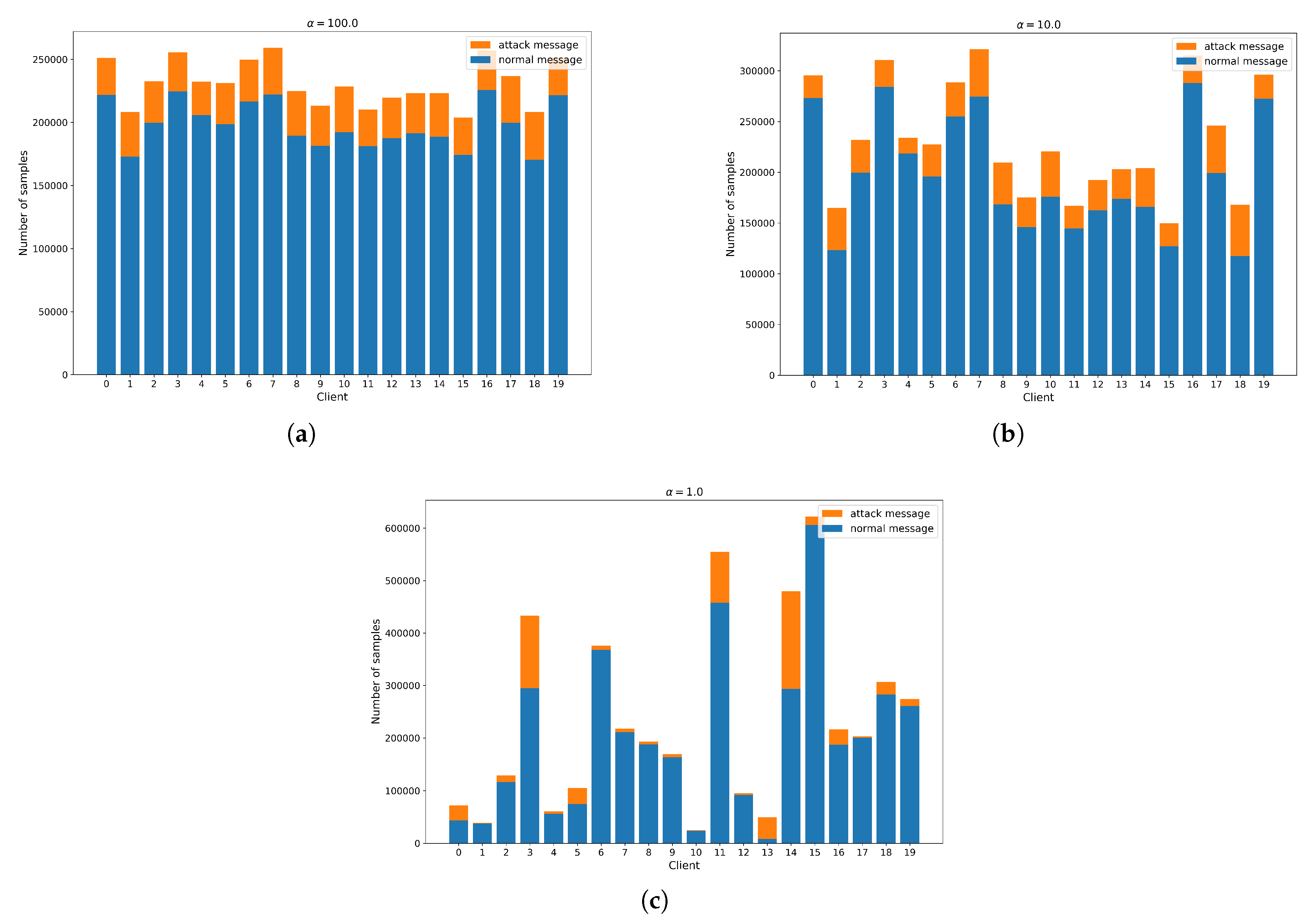

4.2. Partitioning of Non-IID Data

To experiment in a cross-manufacturer environment with Non-IID data distribution, the Dirichlet distribution was employed, following the approach in previous works [

50]. Specifically,

was sampled to allocate

proportion of the instances of class

m to device

i.

The concentration parameter was set to for every attack type:

- 1)

: Represents a nearly IID context.

- 2)

: Represents a moderately Non-IID context.

- 3)

: Represents a significantly Non-IID context.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of PFMeta-IDS was evaluated using standard metrics: accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score. These metrics were calculated based on true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) values, as defined below:

4.4. The Performance of PFMeta-IDS

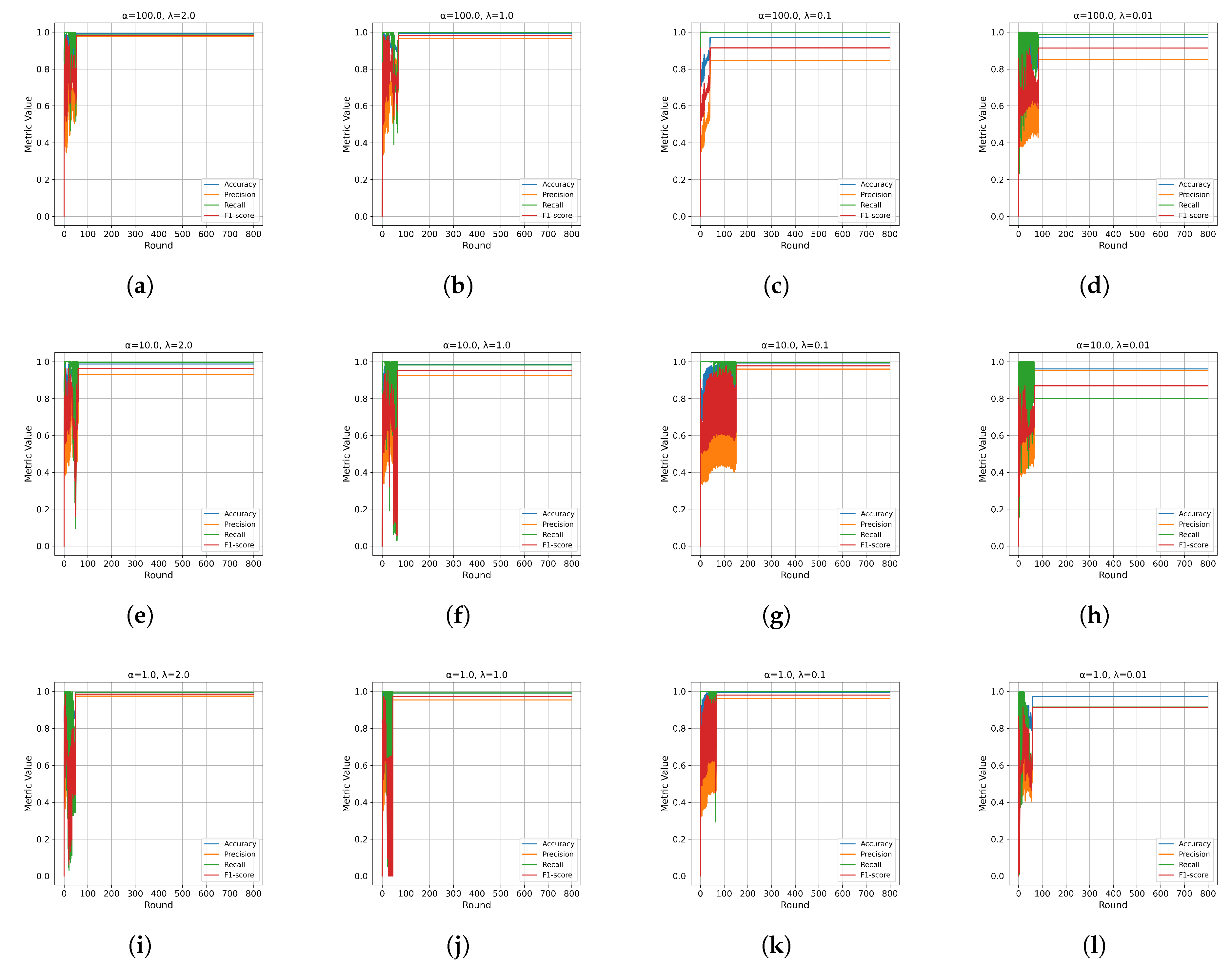

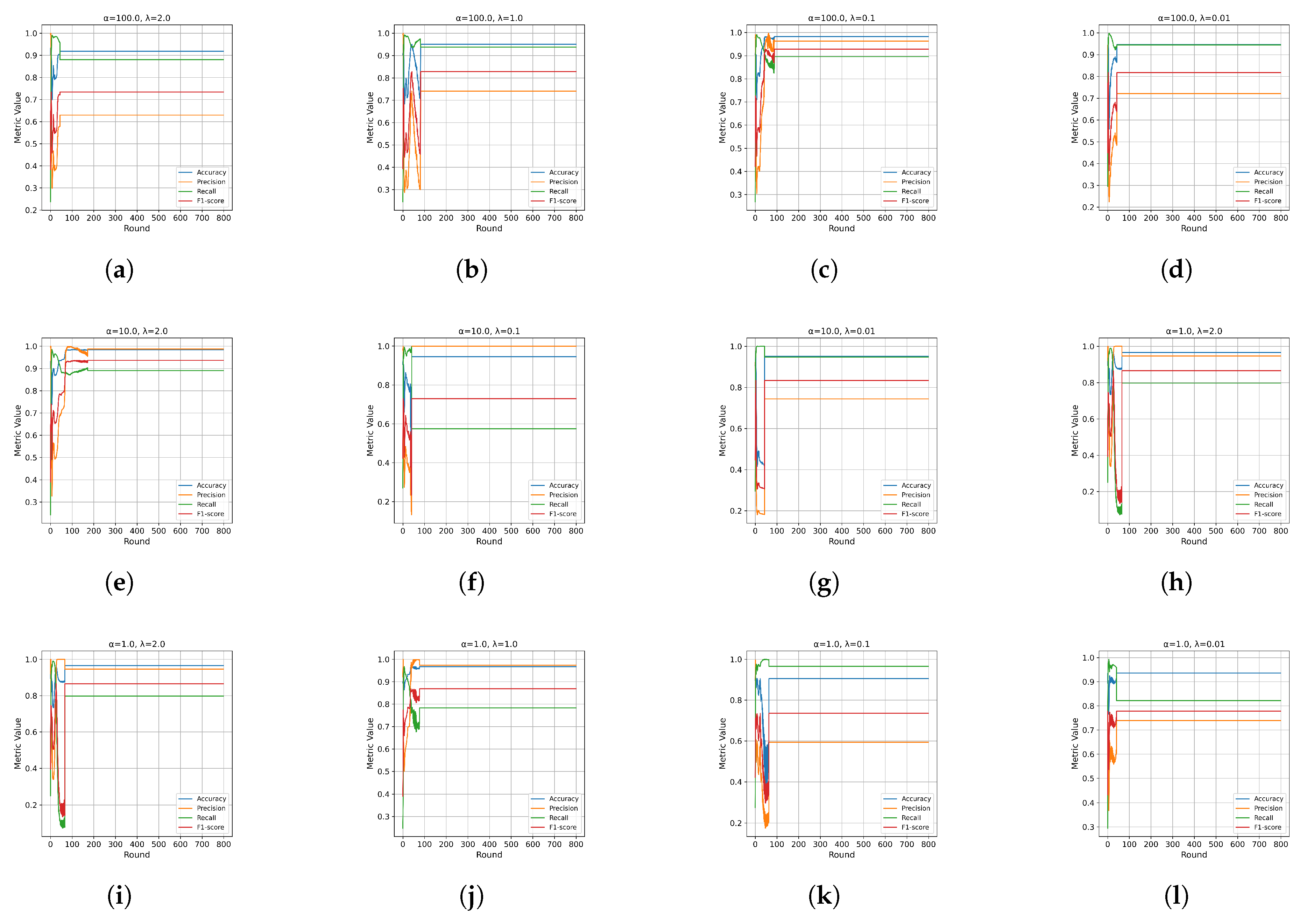

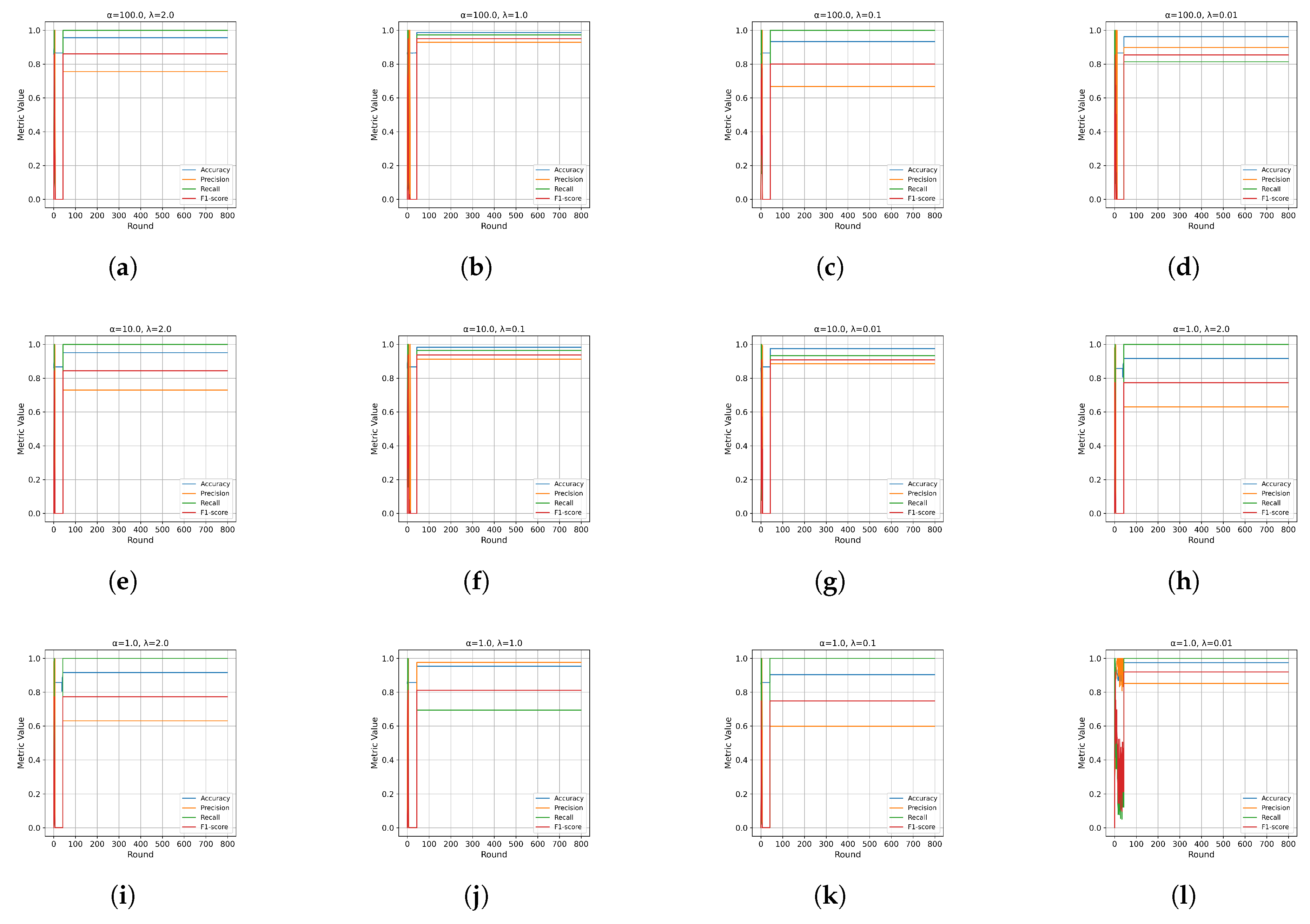

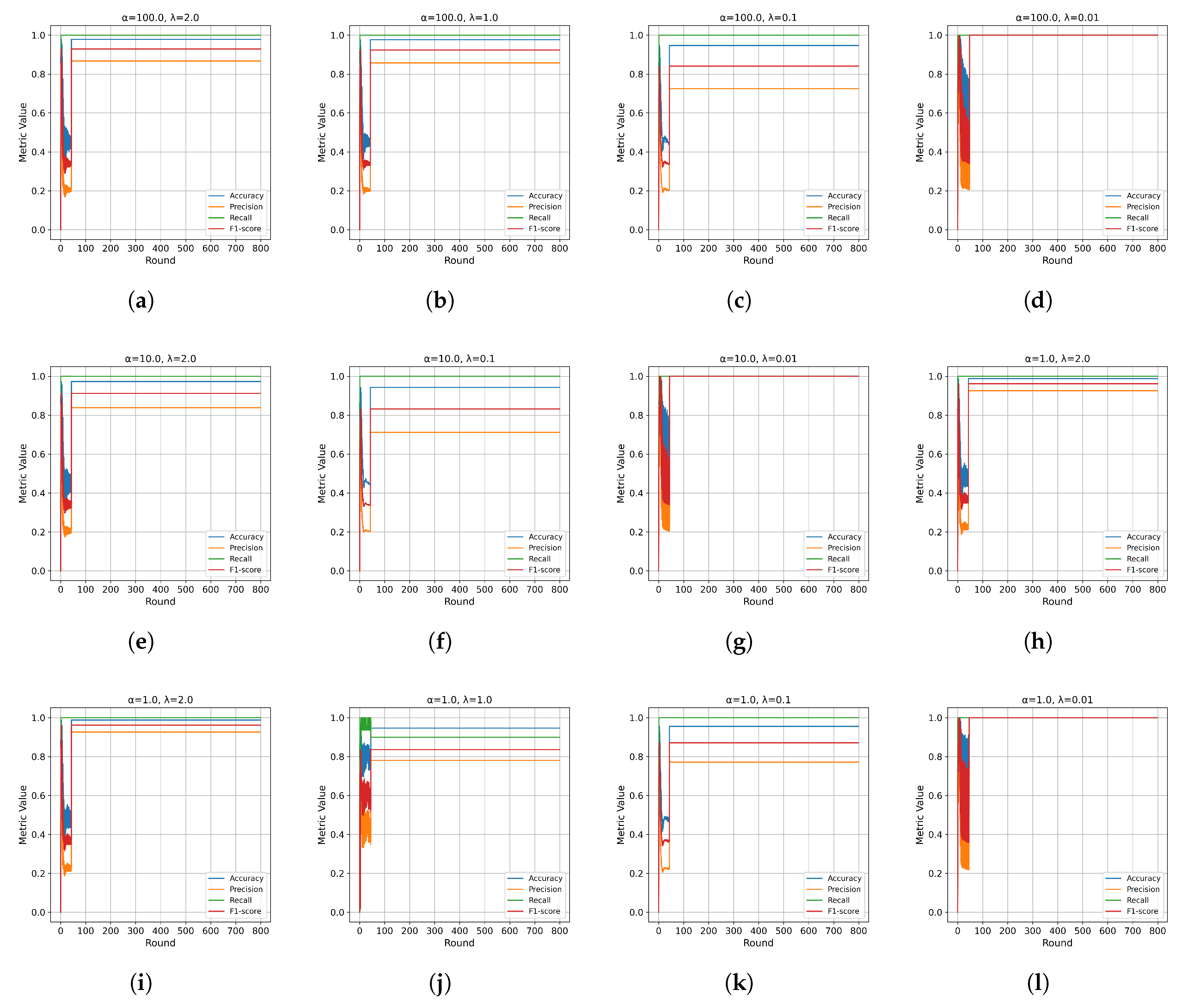

4.4.1. Convergence Performance

In the initial experiment, we evaluated the convergence performance of PFMeta-IDS by training and testing it under varying

and

settings.

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate the results with

and

.

The results show distinct convergence patterns under varying levels of data heterogeneity:

- 1)

DoS Attack: For , convergence stabilizes after 51 rounds at the optimal F1-score (). When , stabilization occurs after 151 rounds (). For , stabilization is observed after fewer rounds ().

- 2)

Fuzzy Attack: With , performance stabilizes after 88 rounds (). For , stabilization takes 172 rounds (). In the highly Non-IID context (), stabilization occurs after 66 rounds ().

- 3)

Gear Spoofing Attack: Convergence stabilizes as early as 44 rounds for both () and (). For , stabilization occurs after 43 rounds ().

- 4)

RPM Spoofing Attack: For , convergence is reached after 48 rounds (). For , stabilization occurs after 44 rounds (), while for , it takes 46 rounds ().

These findings confirm the robustness and adaptability of PFMeta-IDS across varying levels of data heterogeneity and attack scenarios, with convergence influenced by both and . However, for the RPM Spoofing attack,the convergence performance remains stable across different values. This may be because the features affected by RPM Spoofing attacks are relatively consistent across different clients. In such scenarios, the impact of on the convergence process diminishes, as the model can efficiently aggregate gradients without significant conflicts, resulting in stable performance regardless of the value. Furthermore, RPM Spoofing attacks might primarily target a narrower range of network behaviors or message types, simplifying the task of model adaptation and convergence.

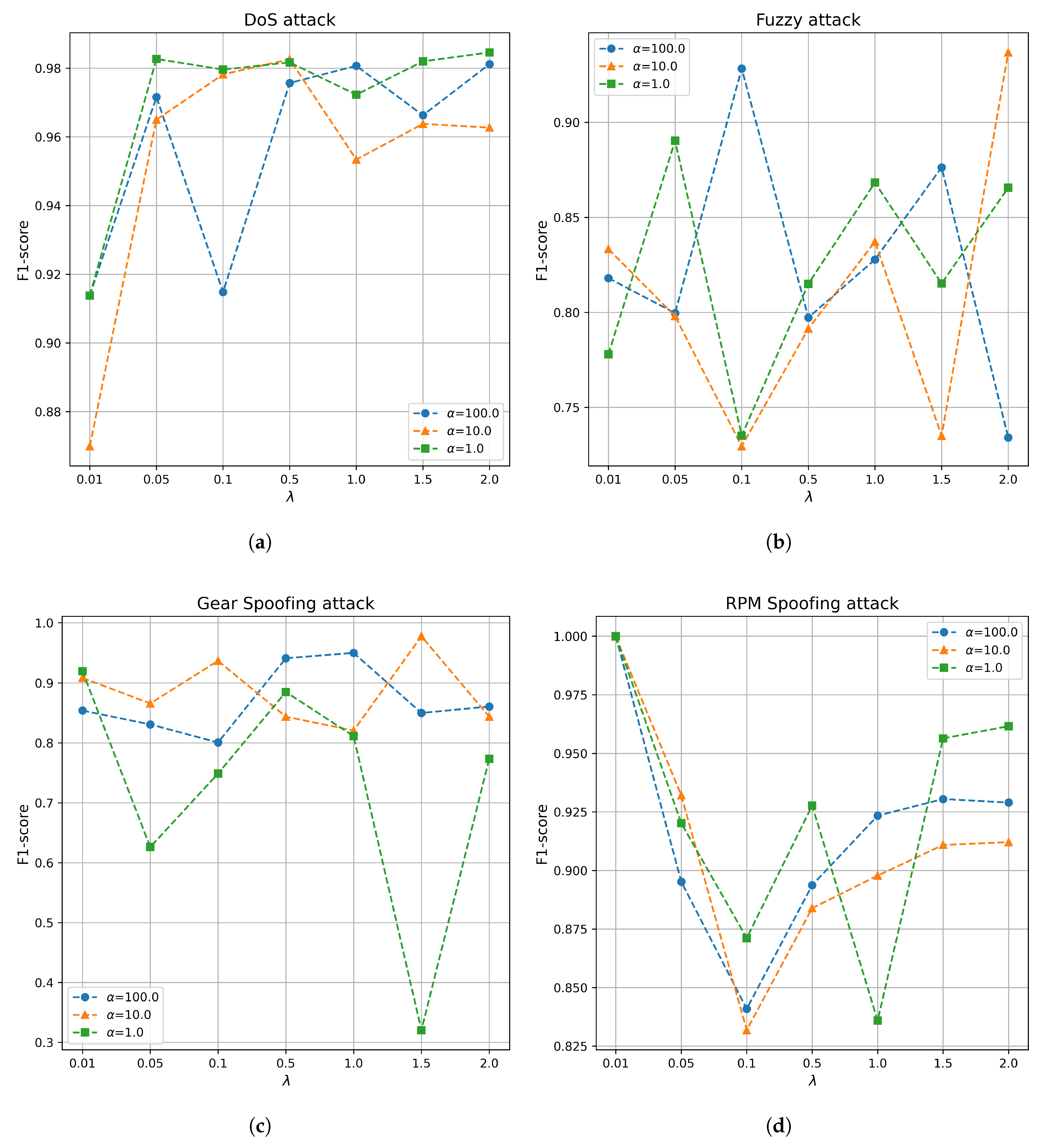

4.4.2. Effect of Personalization

To evaluate the effect of personalization on the performance of PFMeta-IDS, we conducted experiments under varying values of

and

. Here,

controls the degree to which the local meta-model learns from the global meta-model, influencing the level of personalization, while

defines the level of data heterogeneity across clients. The experimental results are summarized in

Figure 13, which illustrates the F1-scores for different attack scenarios, including DoS, fuzzy, Gear Spoofing, and RPM Spoofing attacks.

The results indicate the following trends:

- 1)

DoS Attacks: PFMeta-IDS achieves the highest F1-scores with for most settings, suggesting that higher levels of global knowledge transfer are beneficial for detecting DoS attacks. For and , the performance stabilizes at over 0.98, demonstrating robustness in both high and low data heterogeneity. In contrast, at , the F1-score varies more, indicating a stronger dependence on personalization under moderate heterogeneity.

- 2)

Fuzzy Attacks: The performance exhibits significant variations with changing , suggesting that fuzzy attacks, being more context-dependent, benefit from fine-tuned personalization.

- 3)

Gear Spoofing Attacks: The highest F1-scores are achieved under for both high and low heterogeneity ( and ). Even in moderate heterogeneity (), the F1-score remains relatively high at . This suggests that the patterns of Gear Spoofing attacks tend to be more personalized, making lower levels of global knowledge transfer more effective.

- 4)

RPM Spoofing Attacks: PFMeta-IDS achieves the highest F1-scores with across all settings, indicating that the patterns of RPM Spoofing attacks are highly personalized.

These findings demonstrate the importance of balancing global knowledge transfer and personalization in PFMeta-IDS, with the optimal varying depending on the type of attack and level of data heterogeneity.

4.5. Comparison with Existing Works

To evaluate the effectiveness of PFMeta-IDS, we compare it with several state-of-the-art IDS for vehicular networks. The comparison focuses on three four aspects:

- 1)

Training Data Volume: We categorize the training datasets used in each work as low , medium , or high based on the number of samples.

- 2)

Data Privacy Measures: We examine whether the methods provide mechanisms to preserve the privacy of training data during the learning process.

- 3)

Collaborative Learning: We evaluate whether the methods utilize collaborative learning approaches to leverage data from multiple parties.

- 4)

Performance (F1-Score): We analyze the detection performance under different attack types to highlight the adaptability and robustness of each approach.

As shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3, PFMeta-IDS demonstrates clear advantages over existing works.

Table 2 compares PFMeta-IDS with other IDSs based on training data volume, data privacy measures, and collaborative learning. Most existing works rely on large datasets (high training data volume) to achieve high detection performance, which limits their applicability in scenarios with restricted data availability or need quick adaptability. Additionally, none of these methods incorporate data privacy measures or collaborative learning mechanisms, leaving sensitive data exposed during the training process. In contrast, PFMeta-IDS operates effectively with low training data volumes due to its meta-learning framework, which facilitates rapid adaptation to new scenarios. It also ensures data privacy through federated learning, where raw data remains local to participants. Furthermore, PFMeta-IDS employs a collaborative learning approach, enabling it to leverage multi-party data while maintaining privacy. As shown in

Table 3, PFMeta-IDS achieves competitive F1-scores compared to existing works. For DoS attacks, its score of 0.9846 is comparable to the highest score (0.9926) but surpasses other methods like CNN (0.9471). In fuzzy attacks, it achieves 0.9368, outperforming most methods except Anjum et al. (0.9963). For Gear Spoofing attacks, PFMeta-IDS delivers 0.9780, significantly higher than others. Notably, in RPM Spoofing attacks, PFMeta-IDS achieves a perfect score of 1.0000, outperforming all other works. These results demonstrate its exceptional adaptability and robustness with privacy-preserving capabilities.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we proposed PFMeta-IDS, a personalized federated meta-learning IDS tailored for vehicular networks. By integrating meta-learning with federated learning, PFMeta-IDS addresses the challenges of rapid adaptability, data heterogeneity, and data privacy. It proposed the FedSWR algorithm for balancing personalization and generalization, the lightweight LDwCBN network optimized for resource-constrained environments, and novel preprocessing techniques, KMC-IG, to enhance data processing. Experimental results on the Car-Hacking dataset demonstrate PFMeta-IDS’s superior performance across various attack scenarios, achieving high F1-scores while preserving data privacy and enabling collaborative learning across multiple parties. These findings highlight PFMeta-IDS as a scalable and secure solution for real-world applications. However, this work is limited by its evaluation in environments with relatively moderate heterogeneity, fixed client numbers, and static client participation. Future work will focus on exploring PFMeta-IDS’s effectiveness under more heterogeneous data distributions, larger and dynamically changing client populations, further enhancing its scalability and robustness in real-world applications.

Author Contributions

Wang: Hong-Quan Wang conceptualizing the research question, designing and conducting the experiments, analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. Li: Jin Li provided guidance and advice in the modification of the content. Tao: Yao-Dong Tao provided professional technical guidance. Huang: Dong-Hua Huang contributed to the final version of the manuscript by reviewing and editing the text for intellectual content and coherence.

Funding

This work was supported by the High-Quality Development Special Project of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) of China under Grant No. CEIEC-2023-ZM02-0106.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAN |

Controller Area Network |

| IDS |

Intrusion detection system |

| IoV |

Internet of Vehicles |

| ITS |

Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| IVN |

In-vehicle network |

| ECU |

Electronic Control Units |

| OBD |

onboard diagnostic |

| MAML |

Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| Non-IID |

Non-independent and identically distributed |

| PFMeta-IDS |

Personalized Federated Meta-Learning Intrusion Detection System |

| KMCS |

K-means-based cluster sampling |

| IG |

Information Gain |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| FL |

Federated learning |

| FedSWR |

Federated Similarity-Weighted Regularization |

| SMOTE |

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| LDwCBN |

Lightweight Depthwise Convolutional Bottleneck Network |

| BN |

Batch Normalization |

| TP |

True positive |

| TN |

True negative |

| FP |

False positive |

| FN |

False negative |

References

- Aljabri, W.; Abdul Hamid, Md.; Mosli, R. Enhancing Real-Time Intrusion Detection System for in-Vehicle Networks by Employing Novel Feature Engineering Techniques and Lightweight Modeling. Ad Hoc Networks 2025, 169, 103737. [CrossRef]

- Alfardus, A.; Rawat, D.B. Evaluation of CAN Bus Security Vulnerabilities and Potential Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2023 Sixth International Conference of Women in Data Science at Prince Sultan University (WiDS PSU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023; pp. 90–97. [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Zambreno, J.; Olufowobi, H.; Bloom, G. Survey of Automotive Controller Area Network Intrusion Detection Systems. IEEE Design & Test 2019, 36, 48–55. [CrossRef]

- Lampe, B.; Meng, W. A Survey of Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection in Automotive Applications. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 221, 119771. [CrossRef]

- Song, H.M.; Kim, H.K. Self-Supervised Anomaly Detection for In-Vehicle Network Using Noised Pseudo Normal Data. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 1098–1108. [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Wang, B.; Dai, X.; Li, L.; He, F. A Novel Intrusion Detection Model for the CAN Bus Packet of In-Vehicle Network Based on Attention Mechanism and Autoencoder. Digital Communications and Networks 2023, 9, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, S.; Kalutarage, H.; Al-Kadri, M.O.; Petrovski, A.; Madzudzo, G.; Cheah, M. AI-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for In-Vehicle Networks: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, A.; Sun, H.; Wang, B. Analysis of Recent Deep-Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Methods for In-Vehicle Network. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Lu, C.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Ji, T.; Li, X.; Sheng, Y. Application of Meta-Learning in Cyberspace Security: A Survey. Digital Communications and Networks 2023, 9, 67–78. [CrossRef]

- Hospedales, T.M.; Antoniou, A.; Micaelli, P.; Storkey, A.J. Meta-Learning in Neural Networks: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Huisman, M.; Van Rijn, J.N.; Plaat, A. A Survey of Deep Meta-Learning. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 54, 4483–4541. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xian, R.; Xian, M.; Wang, H.; Ni, L. A Comprehensive Intrusion Detection Method for the Internet of Vehicles Based on Federated Learning Architecture. Computers & Security 2024, 147, 104067. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Lin, X.; Li, S.; Peng, H.; Zhang, B. Global or Local Adaptation? Client-Sampled Federated Meta-Learning for Personalized IoT Intrusion Detection. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2025, 20, 279–293. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.Z.; Yu, H.; Cui, L.; Yang, Q. Towards Personalized Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 34, 9587–9603. [CrossRef]

- Vettoruzzo, A.; Bouguelia, M.R.; Rögnvaldsson, T. Meta-Learning from Multimodal Task Distributions Using Multiple Sets of Meta-Parameters. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Gold Coast, Australia, 2023; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Nandy, T.; Md Noor, R.; Kolandaisamy, R.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Bhattacharyya, S. A Review of Security Attacks and Intrusion Detection in the Vehicular Networks. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2024, 36, 101945. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saud, M.; Eltamaly, A.M.; Mohamed, M.A.; Kavousi-Fard, A. An Intelligent Data-Driven Model to Secure Intravehicle Communications Based on Machine Learning. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2020, 67, 5112–5119. [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, S.C.; Sahingoz, O.K. In-Vehicle Intrusion Detection System on Controller Area Network with Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kharagpur, India, 2020; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Agbaje, P.; Hounsinou, S.; Olufowobi, H. In-Vehicle Network Anomaly Detection Using Extreme Gradient Boosting Machine. In Proceedings of the 2022 11th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO), Budva, Montenegro, 2022; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Devnath, M.K.; Samad, M.D.; Jaffrey Al Kadry, S.M. GGNB: Graph-based Gaussian Naive Bayes Intrusion Detection System for CAN Bus. Vehicular Communications 2022, 33, 100442. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.R.; Jadav, N.K.; Gupta, R.; Tanwar, S. AI-empowered Secure Data Communication in V2X Environment with 6G Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2022 - IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Baldini, G. Intrusion Detection Systems in In-Vehicle Networks Based on Bag-of-Words. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th Cyber Security in Networking Conference (CSNet), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021; pp. 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Boumiza, S.; Braham, R. In-Vehicle Network Intrusion Detection Using DNN with ReLU Activation Function. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW), Sousse, Tunisia, 2023; pp. 410–416. [CrossRef]

- Fenzl, F.; Rieke, R.; Dominik, A. In-Vehicle Detection of Targeted CAN Bus Attacks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Vienna Austria, 2021; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Shen, H. A Transfer Learning Based Abnormal CAN Bus Message Detection System. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Smart Systems (MASS), Denver, CO, USA, 2021; pp. 545–553. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Mao, J.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Cheng, X.; Yang, L. A Survey on Federated Learning in Intelligent Transportation Systems. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024, pp. 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Jallepalli, D.; Ravikumar, N.C.; Badarinath, P.V.; Uchil, S.; Suresh, M.A. Federated Learning for Object Detection in Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Seventh International Conference on Big Data Computing Service and Applications (BigDataService), Oxford, United Kingdom, 2021; pp. 107–114. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhong, L. Object Detection of UAV Power Line Inspection Images Based on Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Nangjing, China, 2022; pp. 2372–2377. [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, S.; Xing, W.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Ma, L.; Chai, H. Glow in the Dark: Smartphone Inertial Odometry for Vehicle Tracking in GPS Blocked Environments. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 12955–12967. [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Munir, M.S.; Tun, Y.K.; Hassan, S.S.; Aung, P.S.; Hong, C.S. When Hierarchical Federated Learning Meets Stochastic Game: Toward an Intelligent UAV Charging in Urban Prosumers. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 10438–10461. [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Ruder, S. Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification, 2018, [arXiv:cs/1801.06146]. [CrossRef]

- Vettoruzzo, A.; Bouguelia, M.R.; Vanschoren, J.; Rögnvaldsson, T.; Santosh, K. Advances and Challenges in Meta-Learning: A Technical Review. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024, 46, 4763–4779. [CrossRef]

- Ruswurm, M.; Wang, S.; Korner, M.; Lobell, D. Meta-Learning for Few-Shot Land Cover Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 2020; pp. 788–796. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Goodman, N.; Piech, C.; Finn, C. ProtoTransformer: A Meta-Learning Approach to Providing Student Feedback, 2021, [arXiv:cs/2107.14035]. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.Q.; Kreatsoulas, C.; Branson, K.M. Meta-Learning GNN Initializations for Low-Resource Molecular Property Prediction, 2020, [arXiv:cs/2003.05996]. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Feng, X.; Kong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Bao, S. Using Meta-Learning to Establish a Highly Transferable Driving Speed Prediction Model from the Visual Road Environment. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 130, 107727. [CrossRef]

- Kiflay, A.; Tsokanos, A.; Fazlali, M.; Kirner, R. Network Intrusion Detection Leveraging Multimodal Features. Array 2024, 22, 100349. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Moubayed, A.; Shami, A. MTH-IDS: A Multitiered Hybrid Intrusion Detection System for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 616–632. [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-Means Clustering Algorithms: A Comprehensive Review, Variants Analysis, and Advances in the Era of Big Data. Information Sciences 2023, 622, 178–210. [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Xumin, L.; Yong, G. Research on k-means Clustering Algorithm: An Improved k-means Clustering Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 Third International Symposium on Intelligent Information Technology and Security Informatics, 2010, pp. 63–67. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, H. Efficiently handling feature redundancy in high-dimensional data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Ninth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Association for Computing Machinery, 2003, KDD ’03, p. 685–690. [CrossRef]

- Huan, S.; Zhang, X.; Shang, W.; Cao, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W. T-Shaped CAN Feature Integration With Lightweight Deep Learning Model for In-Vehicle Network Intrusion Detection. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 25, 21183–21196. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, S.A.; Foh, C.H.; Carrez, F.; Moessner, K. SMOTE-Stack for Network Intrusion Detection in an IoT Environment. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Rhodes, Greece, 2022; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah Alfrhan, A.; Hamad Alhusain, R.; Ulah Khan, R. SMOTE: Class Imbalance Problem In Intrusion Detection System. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computing and Information Technology (ICCIT-1441), Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 2020; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Widodo, A.O.; Setiawan, B.; Indraswari, R. Machine Learning-Based Intrusion Detection on Multi-Class Imbalanced Dataset Using SMOTE. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 234, 578–583. [CrossRef]

- pandas development team, T. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. Zenodo, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32; Curran Associates, Inc., 2019; pp. 8024–8035.

- Althunayyan, M.; Javed, A.; Rana, O. A Robust Multi-Stage Intrusion Detection System for in-Vehicle Network Security Using Hierarchical Federated Learning. Vehicular Communications 2024, 49, 100837. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yurochkin, M.; Sun, Y.; Papailiopoulos, D.; Khazaeni, Y. Federated Learning with Matched Averaging, 2020, [arXiv:cs.LG/2002.06440].

- Purohit, S.; Govindarasu, M. ML-based Anomaly Detection for Intra-Vehicular CAN-bus Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), Rhodes, Greece, 2022; pp. 233–238. [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.; Alqahtani, H.; Thakur, K.; Almadhor, A.; Chander, S.; Kumar, G. A Hybrid Deep Learning Based Intrusion Detection System Using Spatial-Temporal Representation of in-Vehicle Network Traffic. Vehicular Communications 2022, 35, 100471. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).