Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

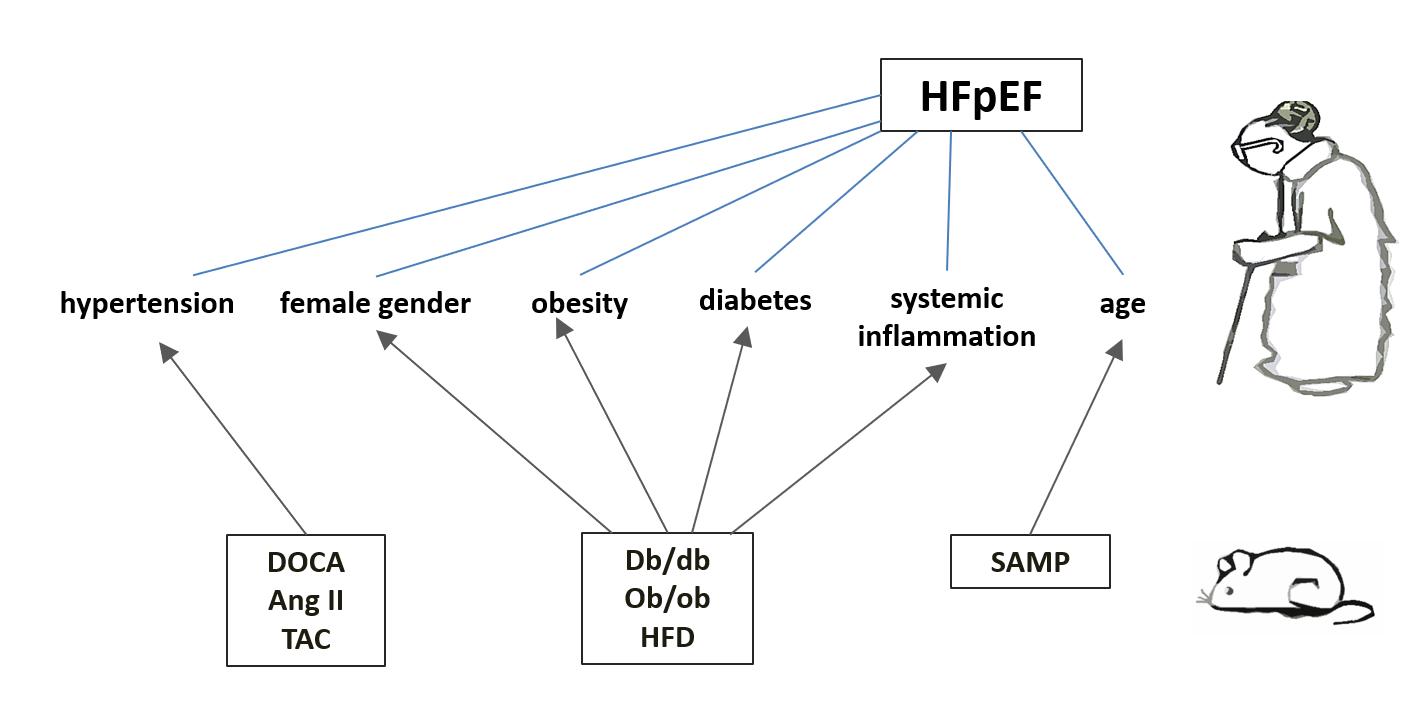

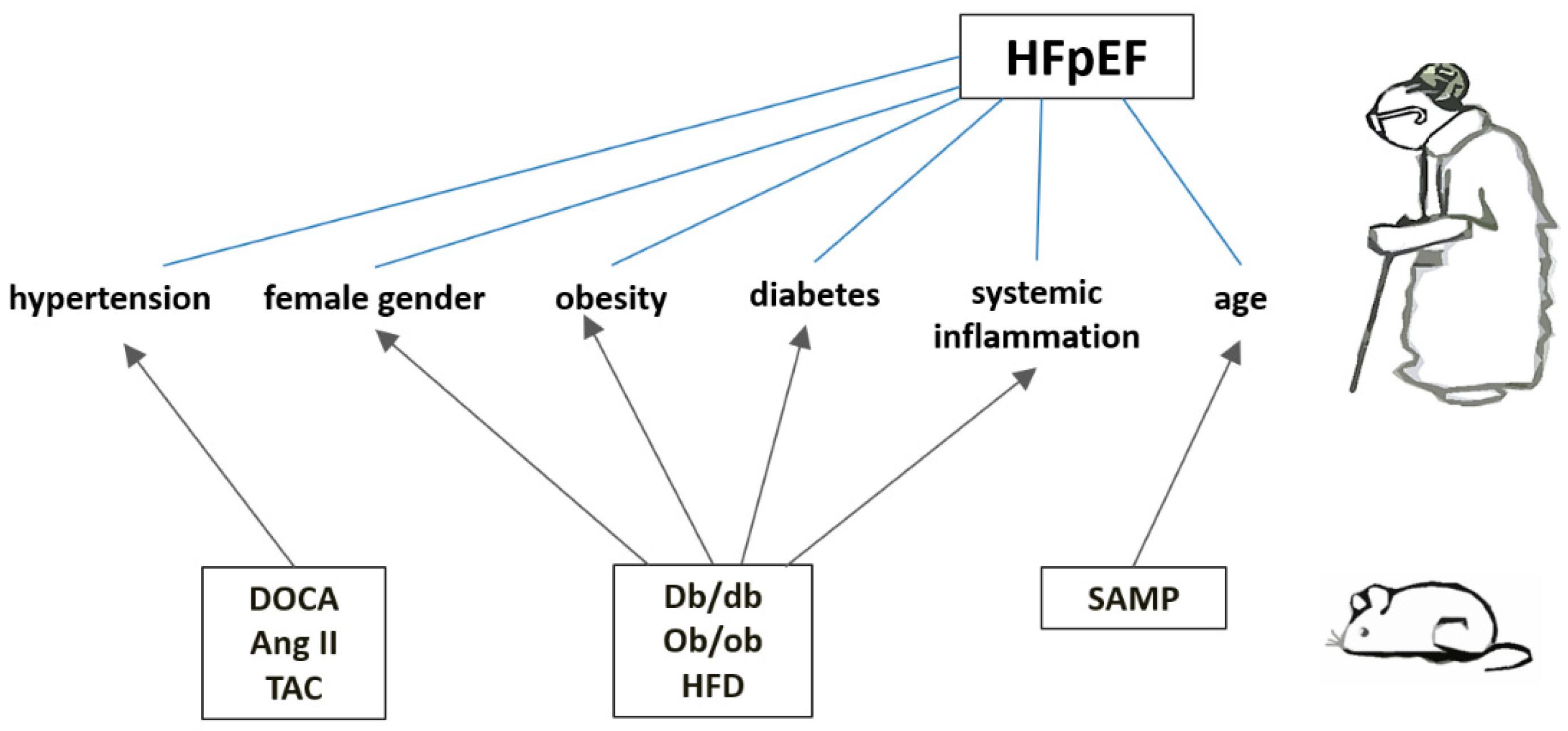

1. Introduction

1.1. Diabetic db/db and Obese ob/ob Mice

1.2. HFD

2. Hypertension-Induced HFpEF Models

2.1. DOCA + High Salt Diet + Unilateral Nephrectomy [DOCA]

2.2. Angiotensin II (Angiotensin II Infusion) [Ang II]

2.3. DOCA + High Salt Diet + Angiotensin II + Unilateral Nephrectomy [DOCA+Ang II]

2.4. Transverse Aortic Constriction (TAC)

2.5. TAC + DOCA

3. HFpEF as a Result of Accelerated Aging (The Senescence-Accelerated Mice)

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMA | Asymmetric dimethylarginine |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| Bcl-2 | anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BNP | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| cMYBP-C | Myosin-binding protein C |

| DOCA | Deoxycorticosterone acetate |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFD | High fat diet |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IRE-1 | Inositol-requiring protein-1α |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IRS-1 | Insulin receptor substrate-1 |

| IVRT | Isovolumic relaxation time |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 |

| MHC | Myosin heavy chain |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| nNOS | Neuronal nitric oxide synthase |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOX | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal fragment of brain natriuretic hormone precursor |

| PERK | Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PKG | Protein kinase G |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SAMP | Senescence-accelerated prone strain |

| SERCA | Sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase |

| SIRT | Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1 |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TAC | Transverse aortic constriction |

| TGF | Transforming growth factor |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| XOR | Xanthine oxidoreductase |

References

- Vasan, R.S.; Xanthakis, V.; Lyass, A.; Andersson, C.; Tsao, C.; Cheng, S.; Aragam, J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Larson, M.G. Epidemiology of Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure in the Framingham Study: An Echocardiographic Study Over 3 Decades. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018, 11, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, B.A.; Jensen, M.D.; Kitzman, D.W.; Lam, C.; Obokata, M.; Rider, O.J. Obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: new insights and pathophysiological targets. Cardiovasc Res. 2023, 118, 3434–3450. [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.S.; Xu, H.; Matsouaka, R.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Devore, A.D.; Yancy, C.W.; Fonarow, G.C. Heart Failure With Preserved, Borderline, and Reduced Ejection Fraction: 5-Year Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017, 70, 2476-2486. [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022, 145, e876-e894. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001062.

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599-3726. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B.; Coats, A.;Tsutsui, H.; Abdelhamid, C.M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Albert, N.; Anker, S.D.; Atherton, J.; Böhm, M.; Butler, J.; et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 352-380. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Kitzman, D.W.; Borlaug, B.A.; van Heerebeek, L.; Zile, M.R.; Kass, D.A.; Paulus, W.J. Phenotype-Specific Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Multiorgan Roadmap. Circulation. 2016, 134, 73-90. [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Choi, D.J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021, 385, 1451-1461. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2022, 387, 1089-1098. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.; Jhund, P.S.; Desai, A.S.; Henderson, A.D.; Lam, C.; Pitt, B.; Senni, M.; et al. Finerenone in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med. 2024, 391, 1475-1485. [CrossRef]

- Redfield, M.M.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Review. JAMA. 2023, 329, 827-838. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, A.G.; Arefieva, T.I.; Potekhina, A.V.; Filatova, A.Y.; Ageev, F.T.; Boytsov, S.A. The Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms Associated with a Microvascular Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Acta Naturae. 2020, 12, 40-51. [CrossRef]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Rodolico, D.; Hill, J.A. Metabolic inflammation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Res. 2021, 117, 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Alcaide P.; Condorelli, G.; Gilette, T.G.; Heymans, S.; Jones A.; Kallikourdis, M.; Lichtman, A.; Marelli-Berg, F.; Shah, S.; et al. Immunometabolic mechanisms of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature Cardiovascular Research. 2022, 1, 211–222. [CrossRef]

- Putko, B.N.; Wang, Z.; Lo, J.; Anderson, T.; Becher, H.; Dyck, J.; Kassiri, Z.; Oudit, G.Y.; Alberta HEART Investigators. Circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor 2 are increased in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction relative to heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: evidence for a divergence in pathophysiology. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e99495. [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; Khan, M.; Klip, I.T.; Meyer, S.; de Boer, R.A.; Jaarsma, T.; Hillege, H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; van der Meer, P.; Voors, A.A. Biomarker Profiles in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e003989. [CrossRef]

- Santhanakrishnan, R.; Chong, J.P.; Ng, T.P.; Ling, L.H.; Sim, D.; Leong, K.T.; Yeo, P.S.; Ong, H.Y.; Jaufeerally, F.; Wong, R.; et al. Growth differentiation factor 15, ST2, high-sensitivity troponin T, and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide in heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012, 14, 1338-1347. [CrossRef]

- Sanders-van Wijk, S.; van Empel, V.; Davarzani, N.; Maeder, M.T.; Handschin, R.; Pfisterer, M.E.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; TIME-CHF investigators. Circulating biomarkers of distinct pathophysiological pathways in heart failure with preserved vs. reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1006-14. [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; Westenbrink, B.D.; Ouwerkerk, W.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Samani, N.J.; Ponikowski, P.; Metra, M.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K; et al. Identifying Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Heart Failure With Reduced Versus Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1081-1090. [CrossRef]

- Carris, N.W.; Mhaskar, R.; Coughlin, E.; Bracey, E.; Tipparaju S.M., Halade, G.V. Novel biomarkers of inflammation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: analysis from a large prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022, 22, 221. [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, I.; Wong, M.V.; Hung, J.; Gong, M.; Waleed, K.B.; Xia, Y.; Lee, S.; Roever, L.; Liu, T.; Tse, G.; Leung, K.; Li, K. Diagnostic and prognostic value of serum C-reactive protein in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2021, 26, 1141-1150. [CrossRef]

- Alogna, A.; Koepp, K.E., Sabbah, M.; Espindola Netto, J.M.; Jensen, M.D.; Kirkland, J.L., Lam, C.; Obokata, M.; Petrie, M.C.; Ridker, P.M.; et al. Interleukin-6 in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2023, 11, 1549–1561. [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, A.; Raza, S.; Sun, J.L.; Anstrom, K.J.; Tracy, R.; Steiner, J.; VanBuren, P.; LeWinter, M.M. Pro-inflammatory biomarkers in stable versus acutely decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007385. [CrossRef]

- Chaar, D.; Dumont, B.L.; Vulesevic, B.; Neagoe, P-E.; Räkel, A.; White, M.; Sirois, M.G. Neutrophils and Circulating Inflammatory Biomarkers in Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2022, 178, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Westermann, D.; Lindner, D.; Kasner, M.; Zietsch, C.; Savvatis, K.; Escher, F.; von Schlippenbach, J.; Skurk, C.; Steendijk, P.; Riad, A.; et al. Cardiac inflammation contributes to changes in the extracellular matrix in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Franssen, C.; Chen, S.; Unger, A.; Korkmaz, H.I.; De Keulenaer, G.W.; Tschöpe, C.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Musters, R.; Niessen, H.W.; Linke, W.A.; et al. Myocardial Microvascular Inflammatory Endothelial Activation in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 312-324. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.F.; Hussain, S.F.; Mirzoev, S.A.; Edwards, W.D.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Redfield, M.M. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2015, 131, 550-559. [CrossRef]

- Srivaratharajah, K.; Coutinho, T.; deKemp, R.; Liu, P.; Haddad, H.; Stadnick, E.; Davies, R.A.; Chih, S.; Dwivedi, G.; Guo, A.; et al. Reduced Myocardial Flow in Heart Failure Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e002562. [CrossRef]

- Glezeva, N.; Voon, V.; Watson, C.; Horgan, S.; McDonald, K.; Ledwidge, M.; Baugh J. Exaggerated inflammation and monocytosis associate with diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: evidence of M2 macrophage activation in disease pathogenesis. J Card Fail. 2015, 21, 167–177. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, A.; Filatova, A.; Potekhina, A.; Arefieva, T.; Gvozdeva, A.; Ageev, F.; Belyavskiy, E. Blood Immune Cell Alterations in Patients with Hypertensive Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023, 10, 310. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, V.S.; Yanek, L.R.; Vaishnav, J.; Ying, W.; Vaidya, D.; Zhen Joan Lee, Y.; Riley, S.J., Subramanya, V.; Brown, E.; Danielle Hopkins, C.; et al. Endomyocardial Biopsy Characterization of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Prevalence of Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 712–724. [CrossRef]

- Hulsmans, M.; Sager, H.B.; Roh, J.D.; Valero-Muñoz, M.; Houstis, N.E.; Iwamoto, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wilson, R.M.; Wojtkiewicz, G.; Tricot, B.; et al. Cardiac macrophages promote diastolic dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2018, 215, 423-440. [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, G.; Schneider, C.; Wong, N.; Bredemeyer, A.; Hulsmans, M.; Nahrendorf. M.; Epelman, S.; Kreisel, D.; Liu, Y.; Itoh, A.; et al. The human heart contains distinct macrophage subsets with divergent origins and functions. Nat Med. 2018, 24, 1234-1245. [CrossRef]

- Bronzwaer, J.; Paulus, W.J. Diastolic and systolic heart failure: Different stages or distinct phenotypes of the heart failure syndrome? Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009, 6, 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A Novel Paradigm for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Katz, D.H.; Selvaraj, S.; Burke, M.A.; Yancy, C.W.; Cheorghiade, M.; Bonow, R.O.; Huang, C-C.; Deo, R.C. Phenomapping for Novel Classification of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2015, 131, 269–279. [CrossRef]

- Kao, D.P.; Lewsey, J.D.; Anand, I.S.; Massie, B.M.; Zile, M.R.; Carson, P.E.; McKelvie, R.S.; Komajda, M.; McMurray, J.; Lindenfels, J. Characterization of subgroups of heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction with possible implications for prognosis and treatment response. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 925–935. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Katz, D.H.; Deo, R.C. Phenotypic Spectrum of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 2014, 10, 407–418. [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, K.; Katherine Teng, T-H.; Chandramouli, C.; Tromp, J., Sakata, Y.; Lam C.S. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Card Fail Rev. 2022, 8, e27. [CrossRef]

- Mancuso P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. Immunotargets Ther. 2016, 5, 47-56. [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.S. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: An expression of stage B heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015, 12, 234–238. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, R.H.; Abel, E.D. Basic Mechanisms of Diabetic Heart Disease. Circ Res. 2020, 126, 1501–1525. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.M.; Rørth, R.; Liu, J.; Kristensen, S.L.; Anand, I.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Cleland, J.; Chopra, V.K.; Desai, A.S.; Ge, J.; et al. Diabetes and pre-diabetes in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Lehrke, M.; Marx, N. Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure. Am J Med. 2017, 130, S40–S50. [CrossRef]

- van Heerebeek, L.; Hamdani, N.; Handoko, M.L.; Falcao-Pires, I.; Musters, R.J.; Kupreishvili, K.; Ijsselmuiden, A.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Bronzwaer, J.; Diamant, M.; et al. Diastolic stiffness of the failing diabetic heart: importance of fibrosis, advanced glycation end products, and myocyte resting tension. Circulation. 2008, 117, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Plante, T.B.; Juraschek, S.P.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.J.; Tracy, R.P., Olson, N.C.; Judd, S.E., Mukaz D.K.; Zakai, N.A.; Long D.L.; Cushman, M. Cytokines, C-Reactive Protein, and Risk of Incident Hypertension in the REGARDS Study. Hypertension. 2024, 81, 1244–1253. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, P.; Song, X.; Li, Y. Elevated Th17 cell proportion, related cytokines and mRNA expression level in patients with hypertension-mediated organ damage: a case control study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022, 22, 257. [CrossRef]

- Cantero-Navarro, E.; Fernández-Fernández, B.; Ramos, A.M.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Rodrigues-Diez, R.R.; Sánchez-Niño, M.D.; Sanz, A.B.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ortiz, A. Renin-angiotensin system and inflammation update. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021, 529, 111254. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Harrison, D.G. Inflammation in Hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2020, 36, 635–647. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.B.; Schrauben, S.J.; Zhao, L.; Basso, M.D.; Cvijic, M.E.; Li, Z.; Yarde, M.; Wang, Z.; Bhattacharya, P.T.; Chirinos, D.A.; et al. Clinical Phenogroups in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Detailed Phenotypes, Prognosis, and Response to Spironolactone. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 172-184. [CrossRef]

- Galli, E.; Bourg, C.; Kosmala, W.; Oger, E.; Donal, E. Phenomapping Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Using Machine Learning Cluster Analysis: Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications. Heart Fail Clin. 2021, 17, 499-518. [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Donal, E.; Kraigher-Krainer, E.; Vasan, R.S. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Lam, C.; Lund, L.H.; Maurer, M.S.; Borlaug, B.A. Characterization of the inflammatory-metabolic phenotype of heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: a hypothesis to explain influence of sex on the evolution and potential treatment of the disease. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1551–1567. [CrossRef]

- Segar, M.W.; Patel, K.V.; Ayers, C.; Basit, M.; Tang, W.; Willett, D.; Berry, J.; Grodin, J.L.; Pandey, A. Phenomapping of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction using machine learning-based unsupervised cluster analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 148-158. [CrossRef]

- Woolley, R.J.; Ceelen, D.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Tromp, J.; Figarska, S.M.; Anker, S.D.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Zannad, F.; Metra, M.; et al. Machine learning based on biomarker profiles identifies distinct subgroups of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 983-991. [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Shahzeb Khan, M.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Choi, D.J.; Chopra, V.; et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the EMPEROR-Preserved trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 2383-2392. [CrossRef]

- Riehle, C.; Bauersachs, J. Small animal models of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2019, 115, 1838-1849. [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, C.; Miyamoto, T.; Kuroda, T.; Karimov, J.H.; Starling, R.C.; Fukamachi, K. Large animal models of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 2022, 27, 595-608. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, X.P.; Li, T.T.; Chen, L.; Feng, Y.P.; Wang, Y.K.; Yin, Y.J.; Little, P.J.; Wu, X.Q.; Xu, S.W.; Jiang, X.D. Animal models of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): from metabolic pathobiology to drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024, 45, 23-35. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, A.P.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Balligand, J.L.; Bauersachs, J.; Dawson, D.; de Boer, R.A.; de Windt, L.J.; Falcão-Pires, I.; Fontes-Carvalho, R.; Franz, S.; et al. An integrative translational approach to study heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a position paper from the Working Group on Myocardial Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 216-227. [CrossRef]

- Schauer, A.; Draskowski, R.; Jannasch, A.; Kirchhoff, V.; Goto, K.; Männel, A.; Barthel. P.; Augstein, A.; Winzer. E.; Tugtekin, M.; et al. ZSF1 rat as animal model for HFpEF: Development of reduced diastolic function and skeletal muscle dysfunction. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 2123-2134. [CrossRef]

- Murase, T.; Hattori, T.; Ohtake, M.; Abe, M.; Amakusa, Y.; Takatsu, M.; Murohara, T.; Nagata K. Cardiac remodeling and diastolic dysfunction in DahlS.Z-Lepr(fa)/Lepr(fa) rats: a new animal model of metabolic syndrome. Hypertens Res. 2012, 35, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzl, M.; Hamdani, N.; Seiler, S.; Alogna, A.; Manninger, M.; Reilly, S.; Zirngast, B.; Kirsch, A.; Steendijk, P.; Verderber, J.; et al. A porcine model of hypertensive cardiomyopathy: implications for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015, 309, H1407-18. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, T.E. 3rd; Scarborough, A.L.; Li, Z.; Polhemus, D.J.; Hidalgo, H.A.; Schumacher, J.D.; Matsuura, T.R.; Jenkins, J.S.; Kelly, D.P.; Goodchild, T.T.; Lefer, DJ. Novel Göttingen Miniswine Model of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Integrating Multiple Comorbidities. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021, 6, 154-170. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Halliday, G.; Huot, J.R.; Satoh, T.; Baust, J.J.; Fisher, A.; Cook, T.; Hu, J.; Avolio, T.; Goncharov, D.A.; et al. Treatment With Treprostinil and Metformin Normalizes Hyperglycemia and Improves Cardiac Function in Pulmonary Hypertension Associated With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020, 40, 1543-1558. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Ou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, Y.; et al. Targeting Mitochondria-Inflammation Circuit by β-Hydroxybutyrate Mitigates HFpEF. Circ Res. 2021, 128, 232-245. [CrossRef]

- Withaar, C.; Meems, L.; Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Boogerd, C.J.; Silljé, H.; Schouten, E.M.; Dokter, M.M.; Voors, A.A.; Westenbrink, B.D.; Lam, C.; de Boer, R.A. The effects of liraglutide and dapagliflozin on cardiac function and structure in a multi-hit mouse model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Res. 2021, 117, 2108-2124. [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, A.B.; Shakeri, H.; Leloup, A.J.; Van Hove, C.E.; De Meyer, G.; Vrints, C.J.; Lemmens, K.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M. Endothelial Senescence Contributes to Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in an Aging Mouse Model. Circ Heart Fail. 2017, 10, e003806. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kubo, H.; Yu, D.; Yang, Y.; Johnson, J.P.; Eaton, D.M.; Berretta, R.M.; Foster, M.; McKinsey, T.A.; Yu, J.; et al. Combining three independent pathological stressors induces a heart failure with preserved ejection fraction phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2023, 324, H443-H460. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.C.; Betancourt. L.; Noriega, A.M.; Brinson, S.C.; Curbelo-Bermudez, N.; Hahn, D.; Kumar, R.A.; Balazic, E.; Muscato, D.R.; Ryan, T.E.; et al. Skeletal myopathy in a rat model of postmenopausal heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Appl Physiol. 2022, 132, 106-125. [CrossRef]

- Vilariño-García, T.; Polonio-González, M.L.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Ribalta, J.; Arrieta, F.; Aguilar, M.; Obaya, J.C.; Gimeno-Orna, J.A.; Iglesias, P.; Navarro, J.; et al. Role of Leptin in Obesity, Cardiovascular Disease, and Type 2 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 2338. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Charlat, O.; Tartaglia, L.A.; Woolf, E.A.; Weng, X.; Ellis, S.J.; Lakey, N.D.; Culpepper, J.; Moore, K.J.; Breitbart, R.E.; et al. Evidence That the Diabetes Gene Encodes the Leptin Receptor: Identification of a Mutation in the Leptin Receptor Gene in db/db Mice. Cell. 1996, 84, 491–495. [CrossRef]

- Mori, J.; Patel, V.B.; Alrob, O.A.; Basu, R.; Altamimi, T.; Desaulniers, J.; Wagg, C.S.; Zamaneh, K.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Oudit, G.Y. Angiotensin 1-7 ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy and diastolic dysfunction in db/db mice by reducing lipotoxicity and inflammation. Circ Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 327–339. [CrossRef]

- Vecoli, C.; Cao, J.; Neglia, D.; Inoue, K.; Sodhi, K.; Vanells, L.; Gabrielson, K.K.; Bedja, D.; Paolocci, N.; L’abbate, A.; Abraham. N.G. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide L-4F prevents myocardial and coronary dysfunction in diabetic mice. J Cell Biochem, 2011, 112, 2616–2626. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.; Mazumder, P.K.; Hu, P.; Chakrabarti, G.; Roberts, M.W.; Jeong Yun, U.; Cooksey, R.C.; Litwin, S.E.; Dale Abel, E. Reduced Cardiac Efficiency and Altered Substrate Metabolism Precedes the Onset of Hyperglycemia and Contractile Dysfunction in Two Mouse Models of Insulin Resistance and Obesity. Endocrinology. 2005, 146, 5341–5349. [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Hu, C.; Hyodo, E.; Arai, K.; Zhou, S.; Lobdell 4th, H.; Walewski, J.L.; Homma, S.; Berk, P.D. Cardiomyocyte Triglyceride Accumulation and Reduced Ventricular Function in Mice with Obesity Reflect Increased Long Chain Fatty Acid Uptake and De Novo Fatty Acid Synthesis. J Obes. 2012, 2012, 205648. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Forte, T.M.; Taniguchi, S.; Ishida, B.Y.; Oka, K.; Chan, L. The db/db mouse, a model for diabetic dyslipidemia: Molecular characterization and effects of western diet feeding. Metabolism. 2000, 49, 22–31. [CrossRef]

- Senador, D.; Kanakamedala, K.; Irigoyen, M.C.; Morris, M.; Elased, K.M. Cardiovascular and autonomic phenotype of db / db diabetic mice. Exp Physiol. 2009, 94, 648–658.

- Bowden, M.A.; Tesch, G.H.; Julius, T.; Rosli, S.; Love, J.E.; Ritchie, R.H. Earlier onset of diabesity-Induced adverse cardiac remodeling in female compared to male mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015, 23, 1166–1177. [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Ren, J. Adiponectin improves cardiomyocyte contractile function in db/db diabetic obese mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009, 17, 262–268. [CrossRef]

- Semeniuk, L.M.; Kryski, A.J.; Severson, D.L. Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac function in diabetic db/db and transgenic db/db -hGLUT4 mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002, 283, H976–H982. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, A.; van Bilsen, M.; Janssen, B.; Brouns, A.E.; Cleutjens, J.; Roemen, T.; Schaart, G.; van der Velden J.; van der Vusse, G.J.; van Nieuwenhoven, F.A. Impaired cardiac functional reserve in type 2 diabetic db/db mice is associated with metabolic, but not structural, remodelling. Acta Physiologica. 2010, 200, 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Alex, L.; Russo, I.; Holoborodko, V.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Characterization of a mouse model of obesity-related fibrotic cardiomyopathy that recapitulates features of human heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018, 315, H934–H949. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, N.; Hervent, A-S.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Matheeussen, V.; Demolder, M.; Baerts, L.; De Meester, I.; Linke, W.A.; Paulus, W.J.; Keulenaer, G. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and myocardial stiffness in diabetic mice is attenuated by inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase 4. Cardiovasc Res. 2014, 104, 423–431. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Xie, X.; Le, K.; Li, W.; Moghadasian, M.H.; Beta, T.; Shen, G.X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic mouse or glycated LDL-treated endothelial cells: protective effect of Saskatoon berry powder and cyanidin glycans. J Nutr Biochem. 2015, 26, 1248–1253. [CrossRef]

- Koka, S.; Aluri, H.S.; Xi, L.; Lesnefsky, E.; Kukreja, R.C. Chronic inhibition of phosphodiesterase 5 with tadalafil attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetic hearts: potential role of NO/SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014, 306, H1558-68. [CrossRef]

- Monma, Y.; Shindo, T.; Eguchi, K.; Kurosawa, R.; Kagaya, Y.; Ikumi, Y.; Ichijo, S.; Nakata, T.; Miyata, S.; Matsumoto, A.; Sato, H.; Miura, M.; Kanai, H.; Shimokawa, H. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound ameliorates cardiac diastolic dysfunction in mice: a possible novel therapy for heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Res. 2021, 117, 1325–1338. [CrossRef]

- Reil, J.-C.; Honl, M.; Reil, G-H.; Granzier, H.L.; Kratz, M.T.; Kazakov, A.; Fries, P.; Müller, A.; Lenski, M.; Custodis, F.; et al. Heart rate reduction by If-inhibition improves vascular stiffness and left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in a mouse model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2013, 34, 2839–2849. [CrossRef]

- Ingalls, A.M.; Dickie, M.M.; Snell, G.D. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. J Hered. 1950, 41, 317–318. [CrossRef]

- Barouch, L.A.; Berkowitz, D.E.; Harrison, R.W.; O’Donell, C.P.; Hare, J.M. Disruption of leptin signaling contributes to cardiac hypertrophy independently of body weight in mice. Circulation. 2003, 108, 754–759. [CrossRef]

- Hammoudi, N.; Jeong, D.; Singh, R.; Farhat, A.; Komajda, M.; Mayoux, E.; Hajjar, R.; Lebeche, D. Empagliflozin Improves Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction in a Genetic Model of Type 2 Diabetes. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 233–246. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Jiang, T.; Lian, C.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, H. QKI deficiency promotes FoxO1 mediated nitrosative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress contributing to increased vulnerability to ischemic injury in diabetic heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014, 75, 131–140. [CrossRef]

- Minhas, K.M.; Khan, S.A.; Raju, S.; Phan, A.C.; Gonzalez, D.R.; Skaf, M.W.; Lee, K.; Tejani, A.D.; Saliaris, A.P.; Barouch, L.A.; et al. Leptin repletion restores depressed {beta}-adrenergic contractility in ob/ob mice independently of cardiac hypertrophy. J Physiol. 2005, 565, 463–474. [CrossRef]

- Li, S-Y.; Yang, X.; Ceylan-Isik, A.F.; Du, M.; Sreejayan, N.; Ren, J. Cardiac contractile dysfunction in Lep/Lep obesity is accompanied by NADPH oxidase activation, oxidative modification of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase and myosin heavy chain isozyme switch. Diabetologia. 2006, 49, 1434–1446. [CrossRef]

- Adingupu, D.D.; Göpel 2, S.O.; Grönros, J.; Behrendt, M.; Sotak, M.; Miliotis, T.; Dahlqvist, U.; Gan, L-M.; Jönsson-Rylander, A-C. SGLT2 inhibition with empagliflozin improves coronary microvascular function and cardiac contractility in prediabetic ob/ob-/- mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019, 18, 16. [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, C.; Bollano, E.; Lindegaard, M.; Bartels, E.D.; Goetze, J.P.; Andersen. C.B.; Nielsen, L.B. Cardiac lipid accumulation associated with diastolic dysfunction in obese mice. Endocrinology. 2003, 144, 3483–3490. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Bajaj, M.; Yang, H-C.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Birnbaum, Y. SGLT-2 Inhibition with Dapagliflozin Reduces the Activation of the Nlrp3/ASC Inflammasome and Attenuates the Development of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Further Augmentation of the Effects with Saxagliptin, a DPP4 Inhibitor. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, N.; Elks, C.M.; Sriramula, S.; Guggilam, A.; Liu, Z.; Borkhsenious, O.; Francis, J. NF-kappaB-induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction in type II diabetes. Cardiovasc Res. 2010, 85, 473–483. [CrossRef]

- Methawasin, M.; Strom, J.; Borkowski, T.; Hourani, Z.; Runyan, R.; Smith 3rd J.E.; Granzier, H. Phosphodiesterase 9a Inhibition in Mouse Models of Diastolic Dysfunction. Circ Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e006609. [CrossRef]

- Broderick, T.L.; Parrott, C.R.; Wang, D.; Jankowski, M.; Gutkowska, J. Expression of cardiac GATA4 and downstream genes after exercise training in the db/db mouse. Pathophysiology. 2012, 19, 193–203. [CrossRef]

- Belke, D.D.; Swanson, E.A.; Dillmann, W.H. Decreased sarcoplasmic reticulum activity and contractility in diabetic db/db mouse heart. Diabetes. 2004, 53, 3201–3208. [CrossRef]

- Lugnier, C.; Meyer, A.; Charloux, A.; Andrès, E.; Gény, B.; Talha, S. The Endocrine Function of the Heart: Physiology and Involvements of Natriuretic Peptides and Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases in Heart Failure. J Clin Med. 2019, 8, 1746. [CrossRef]

- Juguilon, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Enrick, M.; Jamaiyar, A.; Xu, Y.; Gadd, J.; Chen, C-L.W.; Pu, A.; Kolz, C.; et al. Mechanism of the switch from NO to H2O2 in endothelium-dependent vasodilation in diabetes. Basic Res Cardiol. 2022, 117, 2. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, R.M.; Minhas, K.M.; Zheng, M.; Pitz, E.; Treuer, A.; Gonzalez, D.; Schuleri, K.H.; Vandegaer, K.M.; Barouch, L.A.; Hare, J.M. Reduced neuronal nitric oxide synthase expression contributes to cardiac oxidative stress and nitroso-redox imbalance in ob/ob mice. Nitric Oxide. 2007, 16, 331–338. [CrossRef]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Altamirano, F.; Tong, D.; French, K.M.; Villalobos, E.; Kim, S.Y.; Luo, X.; Jiang, N.; May, H.I.; Wang, Z.V.; et al. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature. 2019, 568, 351-356. [CrossRef]

- Cantero-Navarro, E.; Fernández-Fernández, B.; Ramos, A.M.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Rodrigues-Diez, R.P.; Dolores Sánchez-Niño, M.; Sanz, A.B.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ortiz, A. Renin-angiotensin system and inflammation update. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021, 529, 111254. [CrossRef]

- van Heerebeek, L.; Borbély, A.; Niessen, H.; Bronzwaer, J.; van der Velden, J.; Stienen, G.; Linke, W.A.; Laarman, G.J.; Paulus, W.J. Myocardial Structure and Function Differ in Systolic and Diastolic Heart Failure. Circulation. 2006, 113, 1966–1973.. [CrossRef]

- Linke, W.A.; Hamdani, N. Gigantic Business: titin properties and function through thick and thin. Circ Res. 2014, 114, 1052–1068. [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Gheorghiade, M.; Borlaug, B.A.; Pieske, B.; Vaduganathan, M.; Burnett Jr, J.C.; Roessig, L.; Stasch, J-P.; Solomon, S.D.; Paulus, W.J.; Butler, J. The cGMP Signaling Pathway as a Therapeutic Target in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000536. [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Gori, T.; Keaney Jr, J.F.; Maack, C.; Daiber, A. Pathophysiological role of oxidative stress in systolic and diastolic heart failure and its therapeutic implications. Eur Heart J. 2015, 36, 2555–2564. [CrossRef]

- van Heerebeek, L.; Hamdani, N.; Falcão-Pires, I.; Leite-Moreira, A.F., Begieneman, M.; Bronzwaer, J.; van der Velden, J.; Stienen, G.; Laarman, G.J.; Somsen, A.; et al. Low myocardial protein kinase G activity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2012, 126, 830–839. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.D.; Chambers, J.B.; Roberts, L.M.; Henderson, R.P.; Overton, J.M. Diet-induced obesity and cardiovascular regulation in C57BL/6J mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2003, 30, 769–778. [CrossRef]

- Basheer, S.; Malik, I.R.; Awan F.R.; Sughra, K.; Roshan, S.; Khalil, A.; Iqbal, M.J.; Parveen, Z. Histological and Microscopic Analysis of Fats in Heart, Liver Tissue, and Blood Parameters in Experimental Mice. Genes (Basel). 2023, 14, 515.. [CrossRef]

- Benetti, E.; Mastrocola, R.; Vitarelli, G.; Cutrin. J.C.; Nigro, D.; Chiazza, F.; Mayoux, E.; Collino, M.; Fantozzi, R. Empagliflozin Protects against Diet-Induced NLRP-3 Inflammasome Activation and Lipid Accumulation. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2016, 359, 45–53. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Qi, M.; Zhao, P.; Duan, Y.; Yang, G.; Yuan, L. Brown adipose tissue-derived exosomes mitigate the metabolic syndrome in high fat diet mice. Theranostics. 2020, 10, 8197–8210. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-T.; Liu, C-F.; Tsai, T-H.; Chen, Y-L.; Chang, H-W.; Tsai, C-Y.; Leu, S.; Zhen, Y-Y.; Chai, H-T.; Chung, S-Y.; et al. Effect of obesity reduction on preservation of heart function and attenuation of left ventricular remodeling, oxidative stress and inflamma-tion in obese mice. J Transl Med. 2012, 10, 145. [CrossRef]

- Abdurrachim, D.; Ciapaite, J.; Wessels, B.; Nabben, M.; Luiken, J.; Nicolay, K.; Prompers, J.J. Cardiac diastolic dysfunction in high-fat diet fed mice is associated with lipotoxicity without impairment of cardiac energetics in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014, 1842, 1525–1537. [CrossRef]

- Steven, S.; Dib, M.; Hausding, M.; Kashani, F.; Oelze, M.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Hanf, A.; Daub, S.; Roohani, S.; Gramlich, Y.; et al. CD40L controls obesity-associated vascular inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction in high fat diet-treated and db/db mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2018, 114, 312–323. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tang, R.; Ouyang, S.; Ma, F.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. Folic acid prevents cardiac dysfunction and reduces myocardial fibrosis in a mouse model of high-fat diet-induced obesity. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2017, 14, 68. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Chung, J.; Liu, H.; Go, Y.; Gladstein, S.; Farzaneh-Far, A.; Lewandowski, E.D.; Dudley Jr, S.C. Role of Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Glucose Tolerance, Insulin Resistance, and Cardiac Diastolic Dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003046. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Mauro, A.G.; Mezzaroma, E.; Kraskauskas, D.; Marchetti, C.; Buzzetti, R.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Abbate, A.; Toldo, S. A high-sugar and high-fat diet impairs cardiac systolic and diastolic function in mice. Int J Cardiol. 2015, 198, 66–69. [CrossRef]

- Roche, C.; Besnier, M.; Cassel, R.; Harouki, N.; Coquerel, D.; Guerrot, D.; Nicol, L.; Loizon, E.; Remy-Jouet, I.; Morisseau, C.; et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition improves coronary endothelial function and prevents the development of cardiac alterations in obese insulin-resistant mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015, 308, H1020-9. [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, F.R.; Shah, S.J. The future of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Deep phenotyping for targeted therapeutics. Herz. 2022, 47, 308-323. [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Weisenburger, S.; Koch, E.; Burkart, M.; Reifenberg, G.; Förstermann, U.; Li, H. Restoration of perivascular adipose tissue function in diet-induced obese mice without changing bodyweight. Br J Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 3443–3453. [CrossRef]

- Smart, C.D.; Fehrenbach, D.J.; Wassenaar, J.W.; Agrawal, V.; Fortune, N.L.; Dixon, D.D.; Cottam, M.A.; Hasty, A.H.; Hemnes, A.R.; Doran, A.C.; Gupta, D.K.; Madhur, M.S. Immune profiling of murine cardiac leukocytes identifies triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 as a novel mediator of hyper-tensive heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2023, 119, 2312–2328. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Bi, H-L.; Liu, L-X.; Li, N-N.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, H-Z.; Li, H-H. Knockout of immunoproteasome subunit β2i ameliorates cardiac fibrosis and inflammation in DOCA/Salt hypertensive mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017, 490, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y-Y.; Huang, L.; Yao, Y.; Zhou, M-S. Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Deficiency Improves Endothelial Function and Cardiovascular Injury in Deoxycorticosterone Acetate/Salt-Hypertensive Mice. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Carretero, O.A.; Xu, J.; Rhaleb, N-E.; Wang, F.; Lin, C.; Yang, J.J.; Pagano, P.J.; Yang, X-P. Lack of inducible NO synthase reduces oxidative stress and enhances cardiac response to isoproterenol in mice with deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension. Hypertension. 2005, 46, 1355–1361. [CrossRef]

- Silberman, G.A.; Fan, T-H.M.; Liu, H.; Jiao, Z.; Xiao, H.D.; Lovelock, J.D.; Boulden, B.M.; Widder, J.; Fredd, S.; Bernstein, K.E.; et al. Uncoupled cardiac nitric oxide synthase mediates diastolic dysfunction. Circulation. 2010, 121, 519–528. [CrossRef]

- Karatas, A.; Hegner, B.; Windt, L.J.; Luft, F.C.; Schubert, C.; Gross, V.; Akashi, Y.J.; Gürgen, D.; Kintscher, U.; da Costa Goncalves, A.C.; et al. Deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt mice exhibit blood pressure-independent sexual dimorphism. Hypertension. 2008, 51, 1177–1183. [CrossRef]

- Hartner, A.; Cordasic, N.; Klanke, B.; Veelken, R.; Hilgers, K.F. Strain differences in the development of hypertension and glomerular lesions induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate salt in mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003, 18, 1999–2004. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Fu, S.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, L. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction based on aging and comorbidities. J Transl Med. 2021, 19, 291. [CrossRef]

- Schnelle, M.; Catibog, N.; Zhang, M.; Nabeebaccus, A.A.; Anderson, G.; Richards, D.A,; Sawyer, G.; Zhang, X.; Toischer, K.; Hasenfuss, G.; Monaghan, M.J.; Shah, A.M. Echocardiographic evaluation of diastolic function in mouse models of heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018, 114, 20–28. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.F.; Ohtani, T.; Korinek, J.; Lam, C.; Larsen, K.; Simari, R.D.; Valenchik, M.L.; Burnett Jr, J.C.; Redfiled, M.M. Mineralocorticoid accelerates transition to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction via “nongenomic effects”. Circulation. 2010, 122, 370–378. [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, F.; Krebs, C.; Abdulhag, U.N.; Meyer-Schwesinger, C.; Maas, R.; Helmchen, U.; Hilgers, K.F.; Wolf, G.; Stahl, R.; Wenzel, U. Rapid development of severe end-organ damage in C57BL/6 mice by combining DOCA salt and angiotensin II. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 643–650. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Euy-Myoung, J.; Liu, H.; Gu, L.; Dudley, S.C.; Yu, J. Astragaloside IV improves left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in hypertensive mice by increasing the phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Hypertens. 2016, 34, e48–e49. [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Dikalov, S.; Price, S.R.; McCann, L.; Fukai, T.; Holland, S.M.; Mitch, W.E.; Harrison, D.G. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003, 111, 1201–1209. [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T.J.; Hoch, N.E.; Brown, K.A.; McCann, L.A.; Rahman, A.; Dikalov, S.; Goronzy, J.; Weyand, C.; Harrison, D.G. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007, 204, 2449–2460. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Luo, J.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cai, R.; Zhou, M-S. Macrophage depletion protects against endothelial dysfunction and cardiac remodeling in angiotensin II hypertensive mice. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2021, 43, 699–706. [CrossRef]

- Regan, J.A.; Mauro, A.G.; Carbone, S.; Marchetti, C.; Gill, R.; Mezzaroma, E.; Raleigh, J.V.; Salloum, F.N.; Van Tassel, B.W.; Abbate, A.; Toldo, S. A mouse model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction due to chronic infusion of a low subpressor dose of angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015, 309, H771-8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, M.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Zheng, Q.; Niu, X. Aerobic exercise protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy via β3-AR-nNOS-NO activation. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0179648. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, H.; Xu, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Lu, Z.; Kwak, D.; Xu, Y.; Gunther, R.; et al. Left ventricular failure produces profound lung remodeling and pulmonary hypertension in mice: heart failure causes severe lung disease. Hypertension. 2012, 59, 1170–1178. [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, H.; Xu, D. Alpha-ketoglutarate ameliorates pressure overload-induced chronic cardiac dysfunction in mice. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102088. [CrossRef]

- Tsujita, Y.; Kato, T.; Sussman, M.A. Evaluation of left ventricular function in cardiomyopathic mice by tissue Doppler and color M-mode Doppler echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2005, 22, 245–253. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, X.; Hu, X.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, P.; van Deel. E.D.; French, J.P.; Fassett, J.T.; Oury, T.D.; Bache, R.J.; Chen, Y. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency exacerbates pressure overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction. Hypertension. 2008, 51, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Zi, M.; Stafford, N.; Prehar, S.; Baudoin, F.; Oceandy, D.; Wang, X.; Bui, T.; Shaheen, M.; Neyses, L.; Cartwright, E.J. Cardiac hypertrophy or failure? - A systematic evaluation of the transverse aortic constriction model in C57BL/6NTac and C57BL/6J substrains. Curr Res Physiol. 2019, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Baier, M.J.; Klatt, S.; Hammer, K.P.; Maier, L.S.; Rokita, A.G. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is essential in hyperacute pressure overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020, 138, 212–221. [CrossRef]

- Slater, R.E.; Strom, J.G.; Methawasin, M.; Liss, M.; Gotthardt, M.; Sweitzer, N.; Granzier, H.L. Metformin improves diastolic function in an HFpEF-like mouse model by increasing titin compliance. J Gen Physiol. 2019, 151, 42–52. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, Z.; Hua, S.; Jin, W.; Chen, Y. Catestatin Protects Against Diastolic Dysfunction by Attenuating Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029470. [CrossRef]

- Methawasin, M., Granzier, H. Experimentally Increasing the Compliance of Titin Through RNA Binding Motif-20 (RBM20) Inhibition Improves Diastolic Function In a Mouse Model of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2016, 134, 1085–1099. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, K.; Theofilis, P.; Koutsopoulos, G.; Pyrpyris, N.; Beneki, E.; Tatakis, F.; Tsioufis, P.; Chrysohoou, C.; Fragkoulis, C.; Tsioufis K. The role of coronary microcirculation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: An unceasing odyssey. Heart Fail Rev. 2025, 30, 75-88. [CrossRef]

- Marie, A.; Larroze-Chicot. P.; Cosnier-Pucheu, S.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, S. Senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 (SAMP8) as a model of age-related hearing loss. Neurosci Lett. 2017, 656, 138-143. [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.L.; Tanaka, A.; Sorescu, D.; Liu, H.; Jeong, E-M.; Strudy, M.; Walp, E.R.; Dudley Jr, S.C.; Sutliff, R.L. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with cardiac fibrosis in the senescence-accelerated mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011, 301, H824–H831. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Calvo, R.; Serrano, L.; Barroso, E.; Coll, T.; Palomer, X.; Camins, A.; Sánchez, R.M.; Alegret, M.; Merlos, M.; Pallàs, M.; et al. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Down-Regulation Is Associated With Enhanced Ceramide Levels in Age-Associated Cardiac Hypertrophy. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007, 62, 1326–1336. [CrossRef]

- Giridharan, V.V.; Karupppagounder, V.; Arumugam, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Guha, A.; Barichello, T.; Quevedo, J.; Watanabe, K.; Konishi, T.; Thandavarayan, R.A. 3,4-Dihydroxybenzalacetone (DBL) Prevents Aging-Induced Myocardial Changes in Senescence-Accelerated Mouse-Prone 8 (SAMP8) Mice. Cells. 2020, 9, 597. [CrossRef]

- Forman, K.; Vara, E.; García, C.; Kireev, R.; Cuesta, S.; Escames, G.; Tresquerres, J. Effect of a Combined Treatment With Growth Hormone and Melatonin in the Cardiological Aging on Male SAMP8 Mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011, 66A, 823–834. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Matsushita, T.; Kurozumi, M.; Takemura, K.; Higuchi, K.; Hosokawa, M. Pathobiology of the senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM). Exp Gerontol. 1997, 32, 117–127. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).