1. Introduction

Aging, female sex, and menopause are among risk factors for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [

1,

2]. These factors often combine to create a background where hypertension, metabolic alterations such as obesity or type 2 diabetes, atrial fibrillation, kidney disease, valve disease, or other anomalies can trigger the development of HFpEF [

3,

4]. The relative contribution of aging and menopause in women is difficult to study since these are interrelated.

We developed a “two-hit” murine HFpEF model combining an Angiotensin II (AngII) continuous infusion and a High-Fat Diet (HFD) for 28 days (metabolic-hypertensive stress or MHS) in C57Bl/6J young male and female mice. We also observed that this MHS regimen was efficient in inducing an HFpEF phenotype in old (19 months) ovariectomized (Ovx at the age of 6 months) female four-core genotype (FCG) mice [

5]. In this study, we used Ovx as a surrogate for menopause since the MHS was only induced a year later [

6].

Withaar and collaborators had previously developed an HFpEF model in aging mice [

7]. They treated old intact females (20 months) with an HFD for four months and added an AngII infusion during the last four weeks. In males, they observed that they evolved towards heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), suggesting that old male mice were not a useful preclinical model since this HFpEF towards HFrEF transition is seldom observed in human patients.

Since their model is more severe than ours, we felt that older male and female mice could be used to study the relative impact of aging, loss of gonadal hormones, and sex differences.

We report that aging is sufficient for the appearance of several cardiac features associated with HFpEF in mice and that Ovx in females can exacerbate these. The MHS in Ovx-aging females reproduces the expected HFpEF phenotype, whereas in males, several animals evolved towards an HFrEF phenotype. Loss of testosterone by castration completely reversed this and maintained the HFpEF phenotype in old males.

4. Discussion

We previously described the HFpEF two-hit mouse model combining AngII continuous infusion and an HFD for 28 days [

5]. In this study, we studied factors such as aging and gonadectomy that could influence cardiac remodelling and function in mice of both sexes. We used young animals as controls to highlight changes occurring with aging. We studied in parallel mice of both sexes using gonadectomy as a surrogate of menopause in aging females and to potentially explain observed differences related to biological sex.

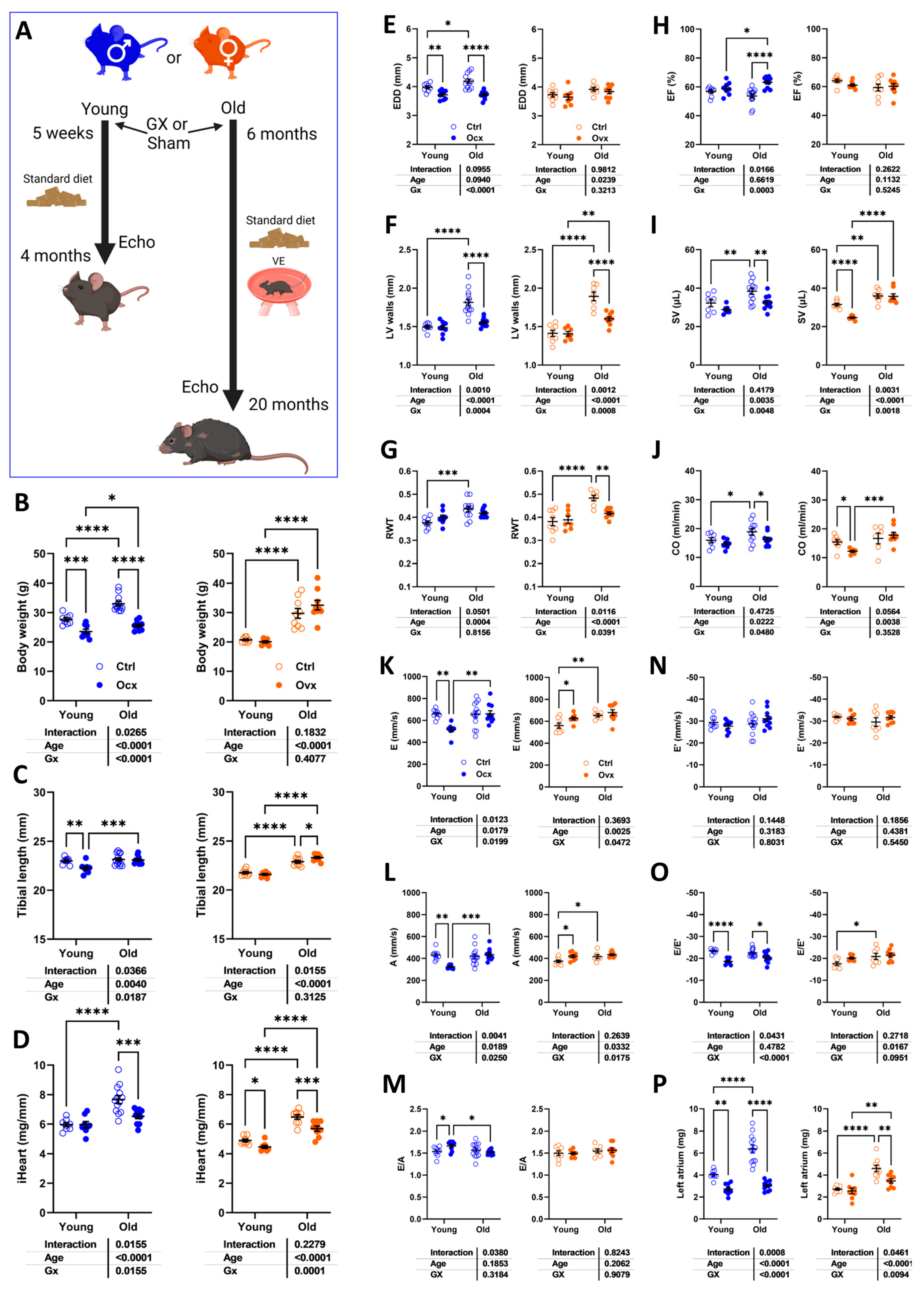

In mice of both sexes, aging was associated with cardiac hypertrophy, LV concentric remodelling, and left atrial enlargement. Ejection fraction remained stable. Diastolic function was altered only in females. We let our aging mice exercise voluntarily (VE) for 6 to 20 months, which could have helped them maintain better cardiac health. Diastolic dysfunction has been reported previously in sedentary old mice. In a recent study in old mice (24 months), we observed that they maintained relatively stable diastolic and systolic functions when left to VE, reducing unwanted and destructive behaviours (aggression, shedding…) and better reproducing their natural life in the wild [

6,

9].

Loss of gonadal hormones at 6 months and for 14 months reduced cardiac hypertrophy related to aging in male and female mice. Old Gx males were leaner than Ovx females. Gx at 6 months did not inhibit body growth. LV wall thickening decreased in gonadectomized animals. Moreover, in males, LV diameter was smaller, which resulted in smaller stroke volume and cardiac output. Diastolic function in older Gx females was similar to that of intact ones.

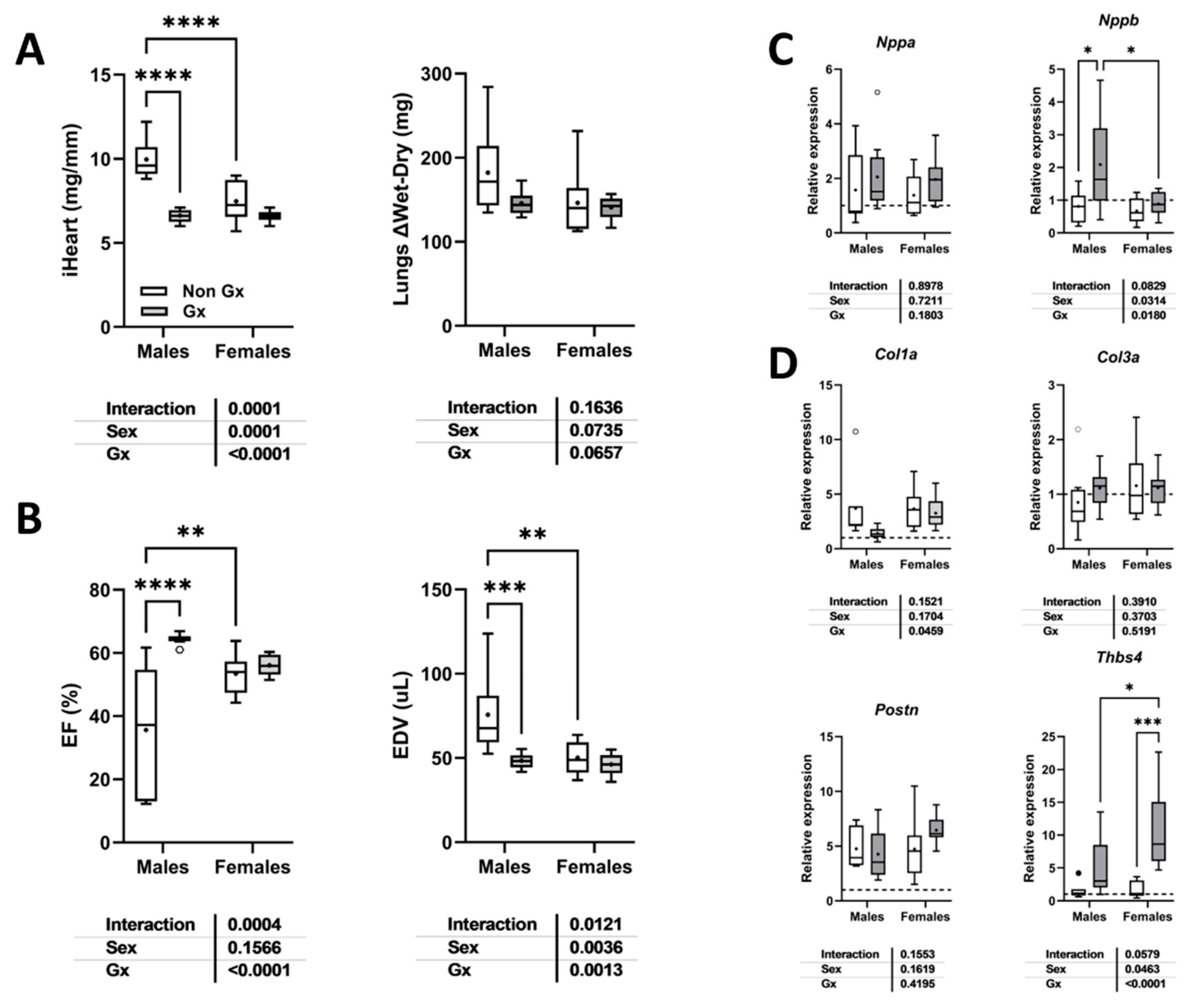

We observed in male mice that aging changed the cardiac phenotype achieved after the MHS from the expected HFpEF to HFrEF. Loss of gonadal steroids completely reversed the EF decrease and LV dilation.

Gonadectomy in older mice was associated with increased myocardial fibrosis content and higher gene expression levels of Col1, Col3, Postn, and Thbs4. In females, mRNA levels for these four genes were also increased in old Ovx mice. This was not observed in young animals. It is unclear why the loss of gonadal steroids, still after more than a year after Gx, was associated with this activation of extracellular matrix (ECM)-related genes. Moreover, Col1 (females), Col3 and Thbs4 gene expression were reduced in older intact mice compared to young controls. It is possible that myocardial remodelling during cardiac growth in young mice requires higher levels of ECM-related gene expression, which is not the case for older animals.

As mentioned, we used Gx as a surrogate for menopause in our mice. We chose to study the animals late after the surgery to concentrate on the long-term cardiac effects of aging. Two recent studies in HFpEF mice have used a chemical method (vinylcyclohexene dioxide or VCD) to induce ovarian failure (menopause) in mice [

12,

13]. One was conducted in the C57Bl6/J strain, as ours, and the other in the C57Bl6/N strain [

12]. Both used the L-NAME + HFD two-hit HFpEF murine model in young animals. These two inbred mouse strains show differences in the vulnerability of females to develop HFpEF under this regimen, the J strain being more susceptible. Troy et al. reported that ovary-intact menopause did not increase vulnerability to HFpEF, whereas Methawasin et al. observed the opposite [

13]. Differences in the mouse strains and experimental designs have been proposed to explain this discrepancy. In one study, HFpEF-causing stress was initiated during the VCD treatment, while in the other, it was after the perimenopausal period. Unfortunately, both studies were conducted in young mice to exclude aging as a confounding factor.

Interestingly, older female mice had a sex-specific plasma inflammation profile characterized by a marked increase in interleukin-17 (A and F), suggesting an involvement of T helper 17 (Th17) cells during aging. This was not observed in males. This increase in IL-17 was also present in young MHS female mice. The meaning of this sex difference is unclear and will require confirmation and additional research. It is unclear whether these changes in IL-17 plasma levels affect the heart or indicate that aging and the MHS in female mice trigger a similar response from IL-17-producing T cells. Myocardial infiltration by T cells has been reported in various murine heart disease models, but there is less literature about Th17 cells, the main producers of IL-17 [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Links between IL-17 and heart failure have been observed before, however [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In heart failure patients, the level of plasma IL-17 was higher than that in patients without heart failure. These levels were negatively correlated with the ejection fraction, suggesting that HFrEF was probably linked to this rise. In male mice with transverse aortic constriction (TAC), IL-17a circulatory and myocardial levels were increased again, linking this interleukin to the development of heart failure. In addition to raised IL-17 levels, we observed that IL-6 (interleukin-6) and TNFα (tumour necrosis factor alpha) levels were increased in older females [

22].

The MHS stress in young mice produced similar cardiac effects irrespective of the presence or absence of gonadal steroids. The main difference was that Ocx males were smaller and had a smaller heart at baseline. The influence of Ocx on cardiac growth in older males was even more evident, highlighting the role of androgens. In females, Ovx did not influence cardiac growth in young animals and cardiac hypertrophy later in life, as we previously reported [

10].

The MHS led older females toward LV concentric remodelling with maintained ejection fraction. In contrast, this stress in old males was associated with a significant loss of EF, including three animals out of 10 that did not survive the 28-day stress. This observation is similar to the one previously reported by Withaar et al [

7]. in their HFpEF model aging model; they also observed that older males developed HFrEF instead of HFpEF. Here, we show that Ocx can prevent this and return the phenotype toward HFpEF, suggesting that androgens are a critical factor in the heart's response to this type of stress. As with other cardiovascular disease animal models, sexual dimorphisms are often apparent when a component of pressure overload is present [

23]. Male animals consistently develop more severe disease symptoms in various experimental settings. Male hearts are more prone to develop eccentric cardiac hypertrophy, whereas female hearts exhibit concentric hypertrophy. For instance, this is also true in patients with aortic stenosis [

24]. This eccentric hypertrophy pattern will accompany more myocardial fibrosis and decreased contractility. In our model, fibrosis was not more important in old MHS males than in old Ovx females, but contractility was severely affected. The expression of cardiac marker genes such as Nppa, Nppb or collagens was not more modulated in old males than in females.

Observations in the L-NAME+HFD mouse model indicate that glucose utilization is partially reduced as a substrate for myocardial ATP production via downregulation of PDH activity [

25,

26]. We observed that the MHS strongly increased myocardial PDK4 content, but this translated into increased levels of PDH phosphorylation only in young animals and old females.

In the MHS model, because of the lipolytic action of AngII [

27], young mice did not gain weight after being fed a high-fat diet for 28 days. Young intact females even lost weight after MHS, not Ovx ones. Loss of estrogens is usually associated with body weight gain in mice [

6], but here, it prevented the loss due to AngII. Older mice were more obese than young animals, as expected. Still, voluntary exercise likely reduced the extent of obesity development, which could have contributed to a milder response to the MHS.

Study Limitations

Affirming that the MHS similarly impacted young male and female mice is difficult. The cardiac response was similar at the morphological and functional levels, but hidden factors must be identified to confirm this.

We did not monitor the mice's running activity since they were not housed individually. Males are expected to run less than females, and the distance covered diminishes with age. In the wild, mice cover significant daily distances to ensure their subsistence. We consider that providing a running device helps to improve their environment by allowing natural murine behaviour.

We did not include hormone replacement groups in our study. Since old Gx animals were kept for over a year, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), although possible, would have been problematic to administer. In addition, it is challenging to design HRT regimens that mimic the real situation in aging animals.

This study was conducted in the C57Bl6/J mouse strain, as are most studies in the field. Studies conducted in inbred strains potentially have a more limited translational value. It will be essential to confirm the validity in various strains or outbred mice that the MHS or other HFpEF-inducing models (27,28).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MA. and JC.; methodology, DCT, EWW, AMG and JAC.; validation, EWW and JC.; formal analysis, DCT, EWW and JC.; investigation, DCT, EWW, EAL, SET, AST.; data curation, DCT, EWW and JC.; writing—original draft preparation, DCT and JC.; writing—review and editing, MA and JC.; supervision, JC.; project administration, JC.; funding acquisition, MA and JC. Funding: The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research PJT-1665850 (to J. Couet and M. Arsenault) and from the Fondation de l’Institut universitaire de cardiologie et de pneumologie de Québec.

Figure 1.

Effects of gonadectomy (Gx) on cardiac morphology and function in young (4 months) and old (20 months) mice of both sexes. A. Schematic representation of the experimental design (Created in BioRender. Couet, J. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/4zt874x). C57Bl6/J/J male and female mice were Gx at 5 weeks or 6 months and were allowed to age until 4 and 20 months. All mice were fed a standard diet described in the Materials and Methods section. Older animals had a running device installed in their cage after Gx to prevent unwanted behaviour and as environmental enrichment. B. Body weight, C. Tibial length and D. indexed heart weight (iHeart) of male (blue) and female (orange) mice. Gx animals (Ocx or ovx) are represented as solid dots. Echocardiography data. E. End-diastolic LV diameter (EDD), F. LV wall thickness in diastole (PWd+IVSd). G. LV relative wall thickness (LV walls/EDD; RWT), H. Ejection fraction (EF). I. LV stroke volume (SV), J. Cardiac output (CO). Diastolic function. K. Pulsed-wave Doppler E wave velocity (E wave), L: A wave velocity and M: E/A ratio. N: Tissue Doppler E’ wave velocity (E’ wave), O: E/E’ ratio and P: Left atrial weight. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=8-14 mice/group).

Figure 1.

Effects of gonadectomy (Gx) on cardiac morphology and function in young (4 months) and old (20 months) mice of both sexes. A. Schematic representation of the experimental design (Created in BioRender. Couet, J. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/4zt874x). C57Bl6/J/J male and female mice were Gx at 5 weeks or 6 months and were allowed to age until 4 and 20 months. All mice were fed a standard diet described in the Materials and Methods section. Older animals had a running device installed in their cage after Gx to prevent unwanted behaviour and as environmental enrichment. B. Body weight, C. Tibial length and D. indexed heart weight (iHeart) of male (blue) and female (orange) mice. Gx animals (Ocx or ovx) are represented as solid dots. Echocardiography data. E. End-diastolic LV diameter (EDD), F. LV wall thickness in diastole (PWd+IVSd). G. LV relative wall thickness (LV walls/EDD; RWT), H. Ejection fraction (EF). I. LV stroke volume (SV), J. Cardiac output (CO). Diastolic function. K. Pulsed-wave Doppler E wave velocity (E wave), L: A wave velocity and M: E/A ratio. N: Tissue Doppler E’ wave velocity (E’ wave), O: E/E’ ratio and P: Left atrial weight. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=8-14 mice/group).

Figure 2.

Effects of aging on cardiac morphology and development of myocardial interstitial fibrosis. A. Representative M-mode echo LV tracings of young and old mice, Gx or not. B. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of male and female heart long-axis sections for each indicated group. C. Myocardial fibrosis (picrosirius red staining) Males (left) and females (right). E. The graph on the left is for females (red), and the one on the right is for males (blue). D. Col1a1, Collagen 1 α1, E. Col3a1, Collagen 3 α1, F. Postn, periostin and G. Tbsp4, thrombospondin 4. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=6-8 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 2.

Effects of aging on cardiac morphology and development of myocardial interstitial fibrosis. A. Representative M-mode echo LV tracings of young and old mice, Gx or not. B. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of male and female heart long-axis sections for each indicated group. C. Myocardial fibrosis (picrosirius red staining) Males (left) and females (right). E. The graph on the left is for females (red), and the one on the right is for males (blue). D. Col1a1, Collagen 1 α1, E. Col3a1, Collagen 3 α1, F. Postn, periostin and G. Tbsp4, thrombospondin 4. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=6-8 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 3.

Plasma protein concentration of 9 immunity-related molecules in male and female mice exposed or not to MHS. Levels of these molecules were evaluated as described in the Materials and Methods section. CCL2: C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2, Csf3: Colony Stimulating Factor 3, Ctla4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4, Cxcl9: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 9, IL-17: interleukin 17, Il6: interleukin-6, Tnf: tumor necrosis factor alpha, and Pdcd1lg2: Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2.- Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=4). F: females, and M: males. Student T-test between young and old animals. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01 and, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 3.

Plasma protein concentration of 9 immunity-related molecules in male and female mice exposed or not to MHS. Levels of these molecules were evaluated as described in the Materials and Methods section. CCL2: C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2, Csf3: Colony Stimulating Factor 3, Ctla4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4, Cxcl9: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 9, IL-17: interleukin 17, Il6: interleukin-6, Tnf: tumor necrosis factor alpha, and Pdcd1lg2: Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2.- Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=4). F: females, and M: males. Student T-test between young and old animals. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01 and, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 4.

MHS in young and old mice: impact of gonadectomy. A. Schematic representation of the experimental design. Created in BioRender. Couet, J. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/aqzg5bj). B. Body weight in young and old intact and Ovx males, C. Body weight in young and old intact and Ovx females, D. Heart weight of males, E. Heart weight of females, F. Left atrial weight of males, and G. Left atrial weight of females. Data are represented as mean +SEM (n=7-14 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 4.

MHS in young and old mice: impact of gonadectomy. A. Schematic representation of the experimental design. Created in BioRender. Couet, J. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/aqzg5bj). B. Body weight in young and old intact and Ovx males, C. Body weight in young and old intact and Ovx females, D. Heart weight of males, E. Heart weight of females, F. Left atrial weight of males, and G. Left atrial weight of females. Data are represented as mean +SEM (n=7-14 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 5.

The effects of age (males) and age + Ovx (females) on the cardiac response to MHS. A. Indexed heart weight (iHeart; Males, left and Females, right). B. iHeart gain from MHS in % (ΔHW/TL). C. Indexed left atrial weight (iLA). D. Lungs water weight (difference between wet and dry weight). Echocardiography data. E. LV wall thickness in diastole (PWd+IVSd). F. LV relative wall thickness (LV walls/EDD; RWT). G. End-diastolic LV diameter (EDD) and H. Ejection fraction (EF). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=7-14 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups. I. Representative B-mode LV tracings (diastolic and systolic) used to estimate LV volumes and ejection fraction in the represented groups.

Figure 5.

The effects of age (males) and age + Ovx (females) on the cardiac response to MHS. A. Indexed heart weight (iHeart; Males, left and Females, right). B. iHeart gain from MHS in % (ΔHW/TL). C. Indexed left atrial weight (iLA). D. Lungs water weight (difference between wet and dry weight). Echocardiography data. E. LV wall thickness in diastole (PWd+IVSd). F. LV relative wall thickness (LV walls/EDD; RWT). G. End-diastolic LV diameter (EDD) and H. Ejection fraction (EF). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=7-14 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups. I. Representative B-mode LV tracings (diastolic and systolic) used to estimate LV volumes and ejection fraction in the represented groups.

Figure 6.

Cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and myocardial interstitial fibrosis after MHS. A. Representative images of WGA-FITC staining from LV sections of the various indicated groups. B. Cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes quantified by WGA-FITC staining control (Ctrl; left) and MHS (middle) groups. CSA gain (% over control; right) from MHS. C. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of old female and male heart sections (Ctrl vs. MHS). D. Myocardial fibrosis (picrosirius red staining). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=7-8 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 6.

Cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and myocardial interstitial fibrosis after MHS. A. Representative images of WGA-FITC staining from LV sections of the various indicated groups. B. Cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes quantified by WGA-FITC staining control (Ctrl; left) and MHS (middle) groups. CSA gain (% over control; right) from MHS. C. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of old female and male heart sections (Ctrl vs. MHS). D. Myocardial fibrosis (picrosirius red staining). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=7-8 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 7.

Modulation of LV gene expression after MHS in young and old mice. A. Nppa, atrial natriuretic peptide. B. Nppb, brain natriuretic peptide. C. Col1a1, Collagen 1 α1, D. Col3a1, Collagen 3 α1, E. Postn, periostin and F. Tbsp4, thrombospondin 4. Data are represented as mean ± sem (n=7-8 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 7.

Modulation of LV gene expression after MHS in young and old mice. A. Nppa, atrial natriuretic peptide. B. Nppb, brain natriuretic peptide. C. Col1a1, Collagen 1 α1, D. Col3a1, Collagen 3 α1, E. Postn, periostin and F. Tbsp4, thrombospondin 4. Data are represented as mean ± sem (n=7-8 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 8.

The MHS inhibits myocardial energy metabolism via the inhibition of glucose utilization. A-D. Expression levels of various genes implicated in myocardial energy production. A. CD36/FAT, fatty acid transporter, B. Cpt1b, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1b, C. Glut4, glucose transporter 4, D. Pdk4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4, E. Bdh1, 3-Hydroxybutyrate Dehydrogenase 1 and F. Ampkb1, AMP kinase b1. Protein content estimated by immunoblotting. G. PDK4, H. phospho-PDH (pyruvate dehydrogenase) and I. PDH. J. Representative blots of Pdk4, p-PDH, PDH, and GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) content in young controls (CtrlY), young old controls (CtrlO) and old MHS. Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 8.

The MHS inhibits myocardial energy metabolism via the inhibition of glucose utilization. A-D. Expression levels of various genes implicated in myocardial energy production. A. CD36/FAT, fatty acid transporter, B. Cpt1b, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1b, C. Glut4, glucose transporter 4, D. Pdk4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4, E. Bdh1, 3-Hydroxybutyrate Dehydrogenase 1 and F. Ampkb1, AMP kinase b1. Protein content estimated by immunoblotting. G. PDK4, H. phospho-PDH (pyruvate dehydrogenase) and I. PDH. J. Representative blots of Pdk4, p-PDH, PDH, and GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) content in young controls (CtrlY), young old controls (CtrlO) and old MHS. Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 9.

Loss of gonadal hormones modulates the cardiac response to MHS in old mice of both sexes. A. Indexed heart weight and lung water weight (difference between wet and dry weight), B. Ejection fraction and end-diastolic LV volume (EDV). C. Nppa and Nppb LV mRNA levels. D. Col1a, Col3a Postn and Thbs4 LV mRNA levels. Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 9.

Loss of gonadal hormones modulates the cardiac response to MHS in old mice of both sexes. A. Indexed heart weight and lung water weight (difference between wet and dry weight), B. Ejection fraction and end-diastolic LV volume (EDV). C. Nppa and Nppb LV mRNA levels. D. Col1a, Col3a Postn and Thbs4 LV mRNA levels. Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.