1. Introduction

Acrocomia aculeata (Macauba), a palm native to tropical and subtropical regions of Latin America, has great potential for bioeconomy. It is widely distributed across various regions of Brazil, where it is known by different names such as bocaiúva, macaíba, coco-baboso, and coco-de-espinho. In addition to the traditional use of its fruits, the utilization of Macauba includes production chains related to the production of vegetable oils, biofuels, cosmetics, and health-promoting foods [

1,

9].

The sustainable cultivation of Macauba not only contributes to economic development, but also offers significant environmental benefits, such as reducing pressure on native forests and vegetation areas, regeneration of degraded lands, recovery of soils, and protection of associated fauna and flora. However, efficient processing of Macauba faces challenges related to variations in the maturation stages of the fruits, as immature fruits have lower oil content and inappropriate chemical composition for processing, which compromises the yield and quality of the product [

11]. This mixture of fruits at different maturation stages complicates the standardization and control of oil quality, resulting in less-homogeneous products with lower commercial value [

9].

In this context, artificial intelligence (AI) techniques based on the recognition of phytobiometric patterns present promising solutions for optimizing Macauba processing [

11]. The application of advanced algorithms enables the identification and separation of fruits based on visual characteristics such as color, texture, and size, facilitating the distinction between maturation stages and improving product quality control [

4].

In family farming, this technology has the potential to increase productivity and improve product quality, providing small farmers with the opportunity to expand their businesses and generate more jobs in the rural sector [

5]. The development of these tools may also foster the emergence of startups and strengthen companies specializing in Macauba processing, thereby promoting a technological innovation ecosystem for R&D [

2].

In postharvest processes, the adoption of AI systems contributes to the optimization of processing, allowing greater accuracy in separating fruit batches according to their maturation stages. This reduces the costs associated with product normalization and results in oils of higher quality and commercial value .

This study is pioneering in proposing the use of trained neural networks for the recognition of phytobiometric patterns of Macauba with the creation of open image databases of fruits at different maturation stages. These databases can foster collaboration between universities and companies, both national and international, and open a new research field focused on this under-explored native species.

To develop the algorithm, it is essential to clearly define maturation criteria, such as color, texture, and size, and to record images of fruits from different angles to capture natural variations. Providing an open database has the potential to encourage academic and technological advancements, thereby expanding the knowledge and applications of macaques in the bioeconomic context.

Thus, the goal is to develop an artificial intelligence-based system with deep convolutional neural networks, aimed at recognizing phytobiometric patterns, to identify the maturation stage of Macauba fruits through images, thereby improving the quality and competitiveness of the product resulting from the processing of Macauba fruits using various methods.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted in the municipality of Lavras, at the Limeira farm, near the BR 265 highway (21° 15’6.24” S, 44° 55’27” W, 846 m altitude) in the southern part of Minas Gerais. A. aculeata (jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart. were collected. The plants were approximately seven–eight meters tall and located in a cattle pasture area. The palm trees from which the bunches were extracted grew spontaneously on private property and were made available for scientific research with prior authorization. The collection was performed with the help of a steel ladder using appropriate PPE for working at height. Before cutting, tarps were placed at the base of the palm tree to collect the fruits and prevent loose fruits from falling into the pasture, which was approximately 10-20 cm tall.

The bunches were placed in plastic bags before being cut using a pruning saw to cushion the fall and minimize mechanical damage to the fruits. Random samples consisting of 50 fruits from selected bunches were chosen. For the information bank, fruit biometrics were measured using a digital caliper, which measured the diameter of all samples taken from the bunch and had an average lateral diameter of 4.8 cm.

Visual analysis of the epicarp color of the fruit, combined with an understanding of the fruiting seasonality of the palms in the region, allowed the collection of fruit samples before the physiological maturity stage (slightly greenish color and strongly attached to the bunches), followed by maturation stages 6 and 7 of the visual texture pattern described by [

10] (Figure

Figure 1). After collection, fruits were removed from the bunches and randomly selected from a batch of 50. They were then washed with running water to remove dirt and debris, and temporarily stored in a metal bucket with a nylon mesh screen with openings of approximately 0.6 mm. The fruits were left for 48 h in a ventilated, shaded area to avoid accelerating the maturation process and to maintain their visual appearance until the beginning of photography.

The collected fruits constituted components of the first VIC01 database. Photographs were taken in different environments and lighting conditions to capture images that more comprehensively and accurately reflected the appearance of the Macauba fruits. For this purpose, a tripod with a fixed position was used to ensure that the camera remained in the same position for image capture. The distance between the camera and the fruit ranged from 30 to 50 cm, and this distance was determined based on the perspectives of different applications of the algorithm.

A white base and background were used to isolate the fruit characteristics more effectively, allowing an enhanced focus on texture, color, and shape. The camera resolution was set to 3456 × 3456 pixels, and each image was processed individually. The selected file format was the PNG. A total of 1,600 photographs of immature fruits (green tone) were taken to compose the VIC01 database. These photographs were taken at six different positions for each fruit, rotating them 90° three times around their axes and photographing the two flattened poles of the fruit.

Five hundred photographs were taken without local artificial lighting, and 500 with local artificial lighting. In addition, 500 initial photographs of unwashed fruits were taken, and 500 photographs were taken after washing with running water to remove dust, dirt, and debris from the surface. Images were captured with and without background for analysis. Preprocessing was not applied to remove noise or imperfections from the images, and no artificial lighting adjustments were made.

The database was structured and stored on Google Drive, allowing centralized and secure access to the files. The images were cataloged in folders organized according to specific categories, and each file was named according to a standard naming convention that identifies its key characteristics. In addition, a shared txt document details the metadata of each image, facilitating the search and cross-referencing of the relevant information. This structure and cataloging of data provide greater robustness to the methodology, ensuring efficiency in the analysis process and ease of replication of the project in different scenarios. Once the database was built, 1,200 images were designated for training, 300 for validation, and 100 for random inference testing. All photographs were randomly reordered during the database creation.

The native back-end environment used in this project was Linux Ubuntu 22.04 LTS, providing optimizations for native bash scripting, C, and Python (3.10.12). With the adoption of YOLO v8, Darknet was replaced with the PyTorch framework. The openCV library was used for image visualization and manipulation, which is recognized for its extensive portfolio of functions, including the visualization and conversion of color channels. This study also used LabelImg, an image annotation tool widely employed in the field of computer vision, and Segment Anything Model 2 (SAM 2), developed by Meta, for semantic segmentation of Macauba fruits. For validation, a precision-recall curve was generated using formulas to calculate precision and recall (

1) and (

2).

Where TP is the true-positive rate, FP is the false-positive rate, and FN is the false-negative rate. The data were processed and compared in detail, considering the methodological approach and tools used in the study from the theoretical foundation to neural network management.

3. Results

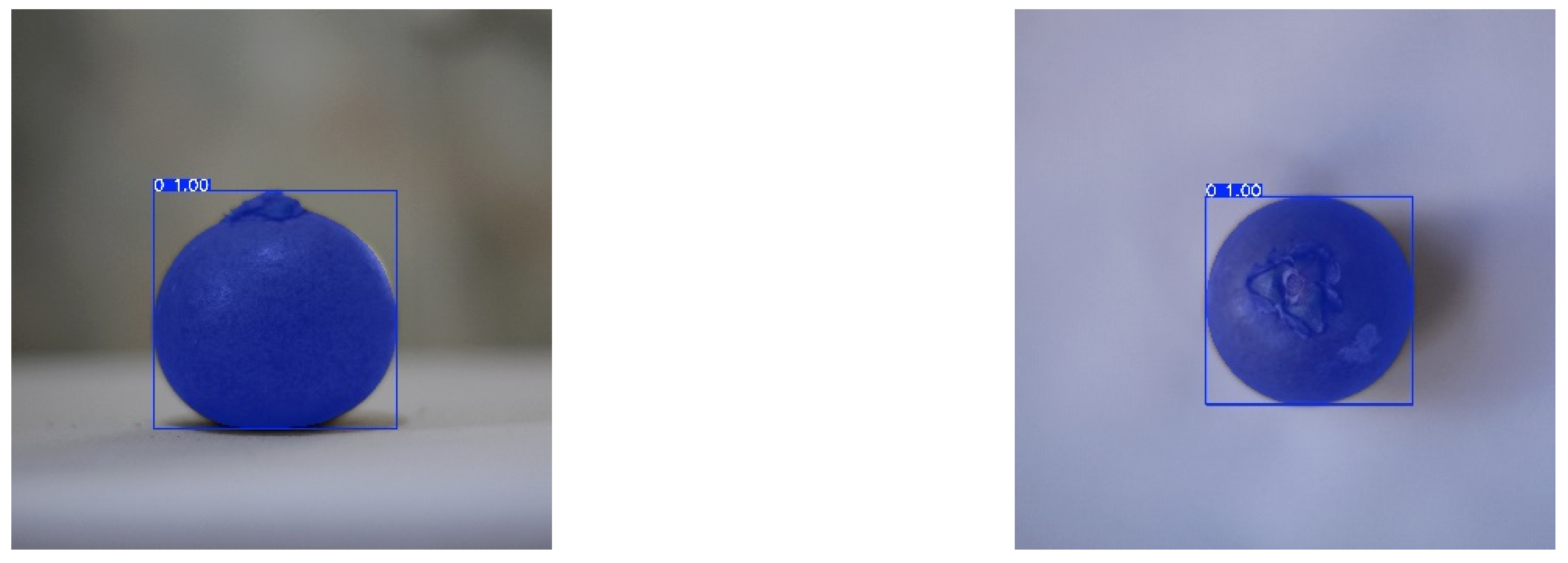

The application of image classifiers and detectors based on the YOLO algorithm to identify Macauba fruit in background-free image models represents a significant advancement in computer vision. It was possible to identify and classify Macauba fruits in images where the background was removed, simplifying visual analysis and reducing interference from distracting elements.

The results obtained with this implementation for the detection and classification of Macauba fruits in background-free images demonstrated a considerable increase in precision. Models trained using this approach can identify fruit more quickly and provide real-time data.

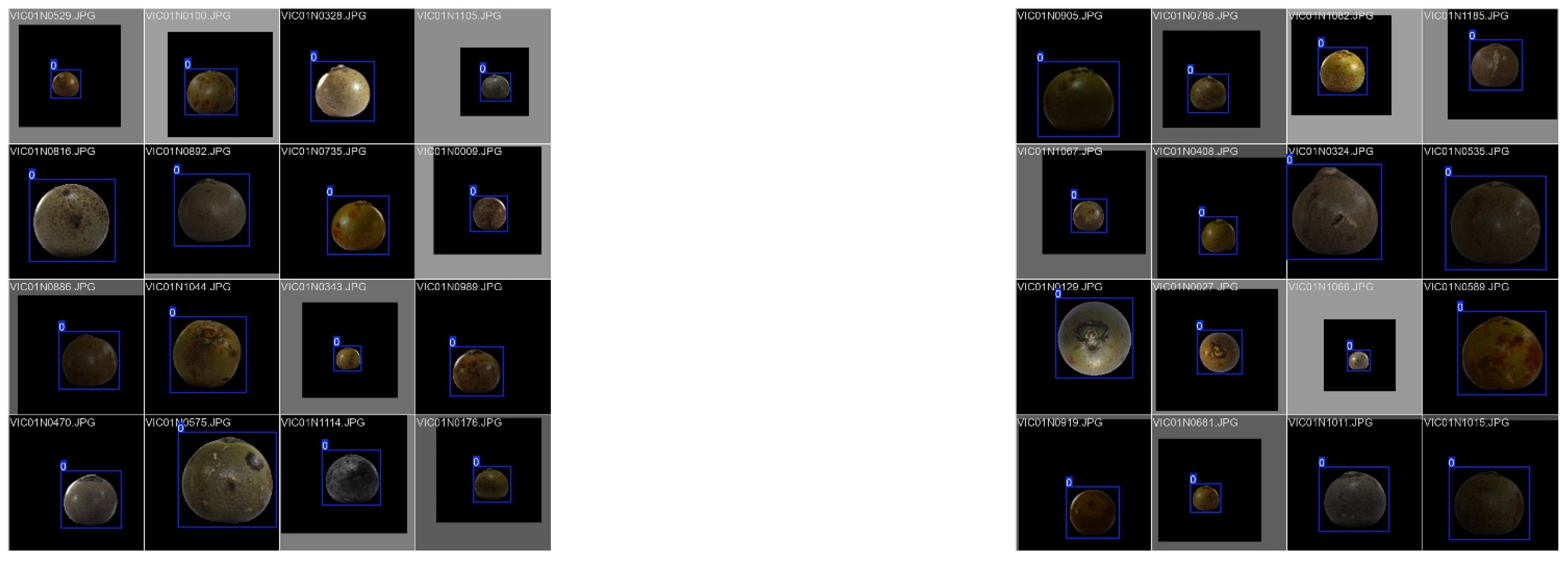

Figure 2 shows the development applied to batches of 16 images for training on background-free images (batches 751 and 752), which were used as inputs in the convolutional layers of the algorithm.

Figure 3 shows the development applied to batches of 16 images for classification and prediction of background-free images. The dependencies of ultralytics (8.3.31) on Python (3.10.12), Torch (2.5.1), and CU121 (CUDA:0 for NVIDIA A100 SMX4 40 GB, 40.514 MB) were used for classification results. Similar work in agriculture has also been successful with this type of model, such as the detection of apple inflorescences in the field as well as the detection and counting of tomato and strawberry growth [

3,

7,

12].

The batches obtained resulted from the execution of the task (detect) in (train) mode using the yolo11x.pt model over 200 epochs.

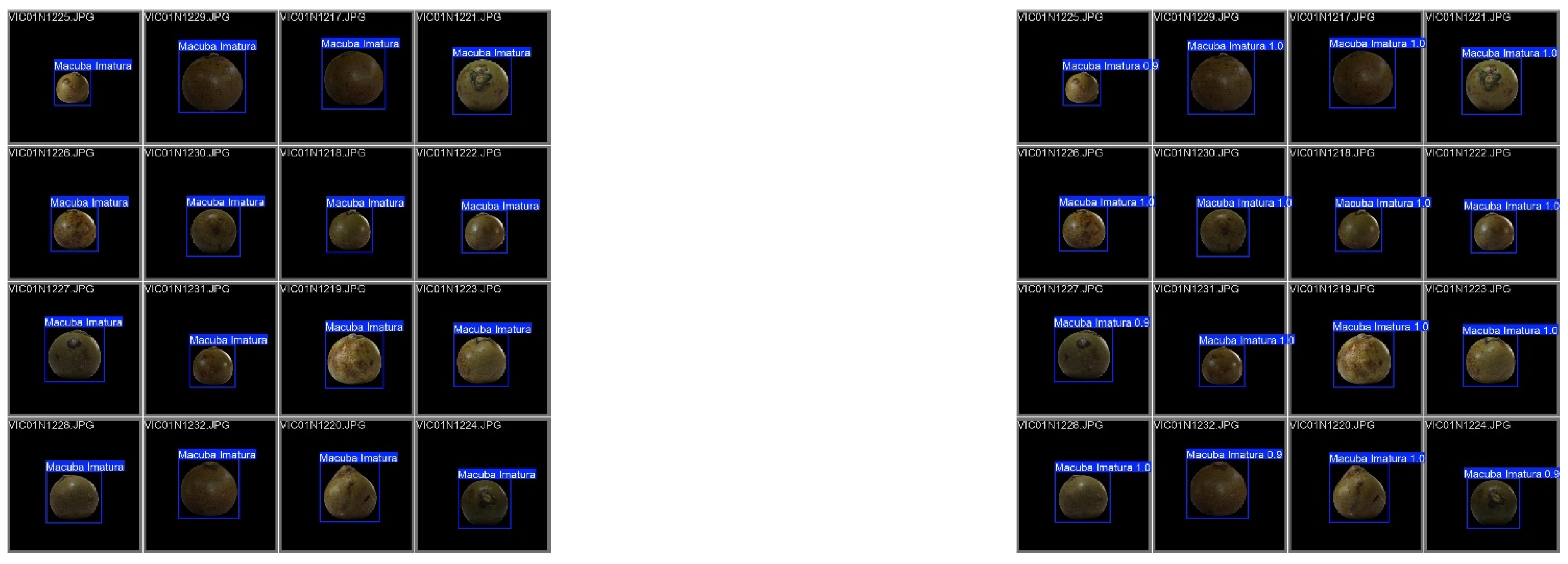

Table 1 and

Table 2 present the results obtained after the validation of the training, which were obtained for the class Immature Macauba ("Macuba Imatura"), and highlight the exceptional performance of the developed model. With 300 images and 300 instances analyzed, the model achieved perfect precision (precision) and recall (recall), both equal to 1.0.

where "C" is the class, "Im" is the number of images, "In" is the number of instances, "P" is Precision, "R" is Recall, "mAP" is the mean average precision for 50% and 95% confidence levels.

This performance indicates that the model made no errors in identifying instances of this class and detected all occurrences without generating false positives or negatives. Additionally, the mAP50 and mAP50-95 values reached 0.995 and 0.968, respectively, reflecting high consistency in detection at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds. These metrics suggest that the model is not only highly accurate under ideal conditions (mAP50), but also maintains superior performance even when the evaluation criteria are stricter (mAP50-95). These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the model and its ability to identify instances accurately.

[

8], when using the YOLO-V4 model for yield estimation in an orange orchard, an mAP of 0.908 was observed, indicating a simple, practical, and effective method for detecting and estimating orange fruit yield in an orchard. Similarly, the results of [

6], who evaluated the detection efficiency of apples at harvest in the field, corroborated the findings of this study, where their network showed an mAP of 0.9713.

Unlike background-free images, background images (with background) contain various elements that can interfere with detection accuracy, requiring the model to be sufficiently robust to distinguish Macauba fruits in different contexts and background scenarios.

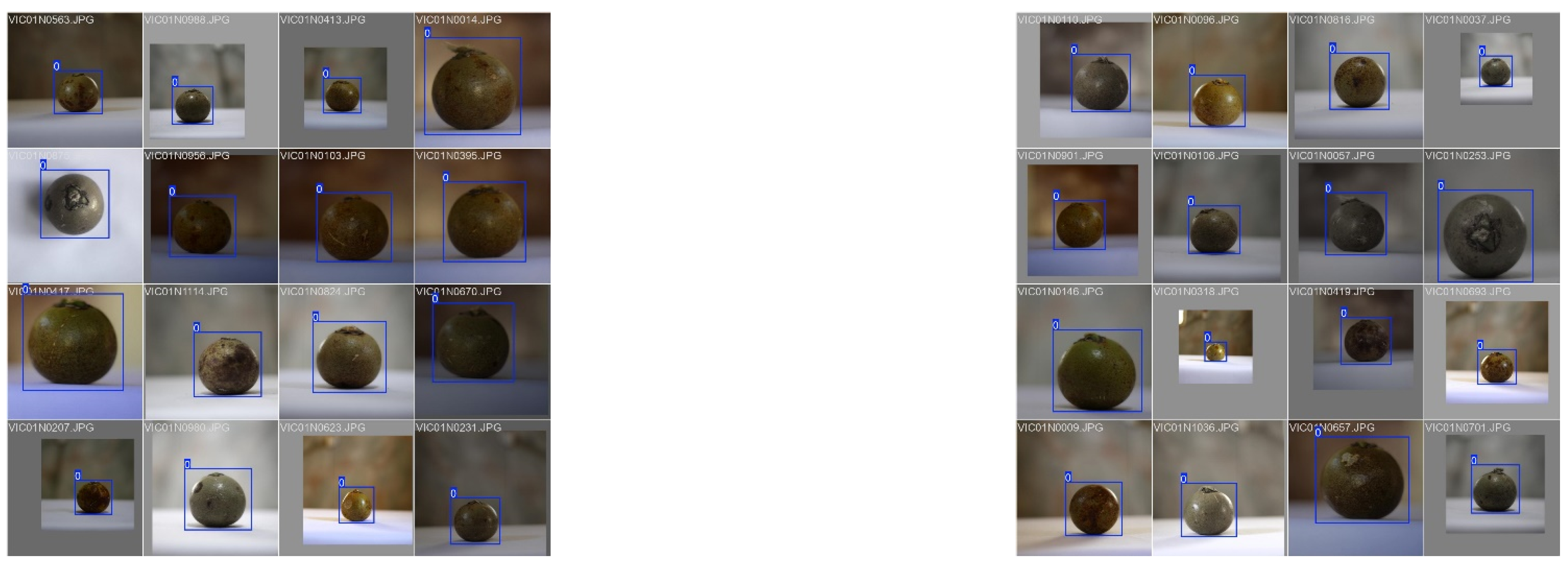

Figure 4 shows the development applied to batches of 16 images for training on the background images (batches 14251 and 14252) used as inputs in the convolutional layers of the algorithm.

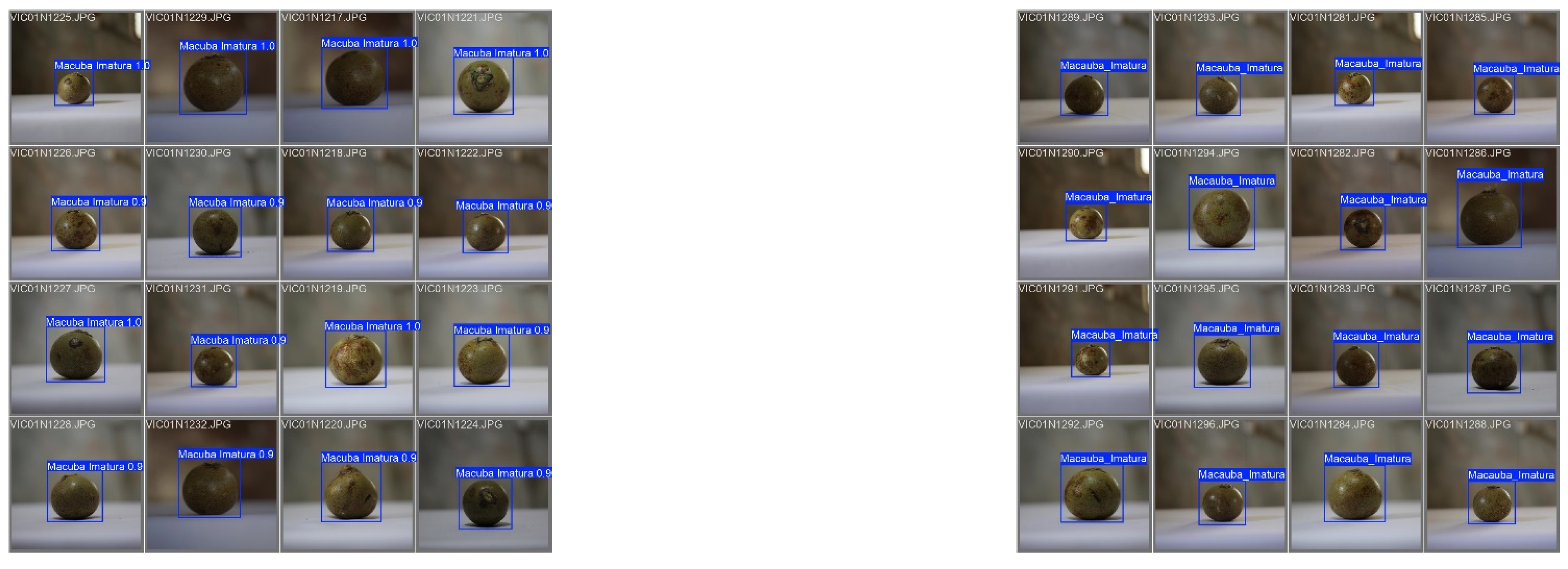

Figure 5 shows the development applied to batches of 16 images for the classification and prediction of on-background images.

The obtained batches resulted from the execution of the detection task (detect) in training mode (train) using the yolo11x.pt model over 200 epochs.

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the results obtained after training validation. The performances observed for the Immature Macauba ("Macuba Imatura") class demonstrated the exceptional performance of the evaluated models. Both the background-free model and new on-background model analyzed 300 images and instances, achieving ideal precision and recall, both equal to 1.0. However, the new model showed a slight advantage in terms of the mAP50-95 values, reaching 0.973. These higher values reflect greater consistency and robustness in detection at different intersections over union (IoU) thresholds. Therefore, the results confirmed the enhanced effectiveness of the new model in consistently identifying class instances in various scenarios.

The application of semantic segmentation techniques for the identification and analysis of Macauba fruit is highly effective. In this context, segmentation enabled the precise distinction of fruits in images of different resolutions, both low (500 × 500) and high quality (3456x3456), even under adverse lighting and background conditions.

The process showed high fidelity in delimiting fruit boundaries and minimizing overlap and fragmentation errors in segmented regions. The generated visualizations presented enhanced clarity and detail, facilitating quantitative and qualitative analyses of the morphological characteristics of Macauba fruits. Based on the results obtained, the final model can be implemented in systems for counting, distribution, and size estimation of fruits.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the results.

The comparison between the two models using distinct datasets with resolutions of 500×500 pixels without backgrounds and 3456×3456 pixels with backgrounds revealed significant differences in the detection performance. Both the models achieved high levels of precision and recall when identifying the target class. However, the model trained with high-resolution images and backgrounds exhibited a slight advantage in terms of mAP50-95 metrics.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the condensed results of the predictions.

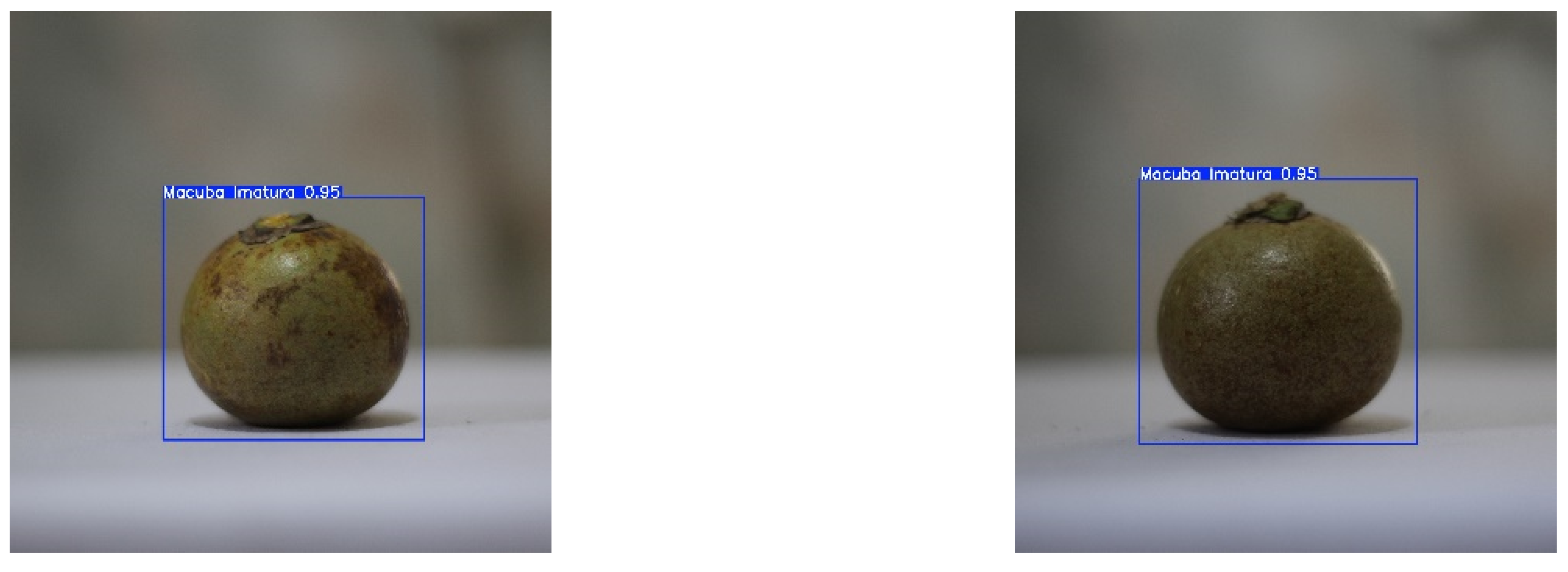

The model’s performance analysis revealed a significant reduction in the metric, which decreased from 0.9 to approximately 0.2 throughout the training process. The metric is crucial for evaluating accuracy of the bounding box (BB) predictions in the detected images, representing the discrepancy between the boxes predicted by the model and the ground truth boxes present in the training images. The drop from 0.9 to 0.2 indicated a substantial improvement in the ability of the model to locate and delimit objects of interest with greater accuracy.

Initially, a of 0.9 suggests there was a considerable margin of error in predicting the BB, possibly due to outdated initialization of the model parameters or the complexity of the dataset images. As the training progressed, a continuous reduction in this metric was observed, reflecting the greater effectiveness of the developed algorithm, as well as the adequacy of the regularization strategies adopted to prevent overfitting. Upon reaching a of 0.2, the model demonstrated a remarkable ability to generalize and adapt robustly to variations in the neural network input data.

The decrease in from 1.4 to 0.1 indicated a significant improvement in the model’s ability to correctly classify. Initially, a of 1.4 suggests that the model encountered considerable difficulties in defining the "Macauba Imatura" class. This was possibly due to improper parameter initialization, high class complexity, or the overlap of intraclass features in the dataset. As the training progressed, the continuous reduction of this metric reflected the effectiveness of the algorithm and adequacy of the parameter regularization strategies.

Upon reaching a of approximately 0.1, the model demonstrated remarkable accuracy in classifying object classes, indicating that the predictions were in good agreement with the actual classes. This improvement suggests that the model can be generalized to intraclass variations in neural network input data, such as changes in lighting, viewing angles, and background noise (on-background). Moreover, the significant reduction in contributed to an overall improvement in model performance, complementing the initial reduction observed in the metric. Together, these reductions indicate that the model is highly optimized and ready for both object localization and fruit classification for future applications.

The decrease in

from 1.4 to 0.8 indicated a slight improvement in the ability of the model to predict the locations and dimensions of the detected fruit BB more accurately. Initially, a

of 1.4 suggested that the model faced considerable challenges in capturing the precise distributions of the image coordinates. This was possibly due to the significant variations in the scale and proportion of fruits in the dataset. As the training progressed, the continuous reduction in this metric reflected a slight optimization of the algorithm. The drop in this metric demonstrated that the model improved its ability to adjust the BB predictions closer to the actual distributions, with greater accuracy at the locations of the fruits. The reduction in

directly contributed to a slight overall improvement in model performance, complementing the reductions observed in the

and

metrics. Together, these three improvements indicate that the model is becoming more effective and its robustness is gradually increasing. The performance metrics are graphically shown in

Figure 10. Overall, the model showed a decreasing trend toward minimum values close to zero, indicating completion of its primary training phase. The same analysis can be extended to the validation metrics (

,

, and

) following this concept.

The presence of high false-positive values indicates that the model is experiencing failures, thus requiring modifications for optimization. In the present study, for 300 validations of immature fruits, the neural network achieved a 100% success rate, as evidenced by the True Positives (TP). All correct predictions were aligned along the main diagonal of the confusion matrix, with the first cell highlighted to represent absolute correct predictions. This flawless performance suggests that in the initial phase of detecting a single class, the model demonstrates high efficacy in correctly identifying the target instances, eliminating the occurrence of FP and FN. These results corroborate the robustness of the proposed model, establishing a solid foundation for subsequent stages of the project, which involves the classification and segmentation of secondary classes.

Figure 11 shows the results for the raw and normalized matrices.

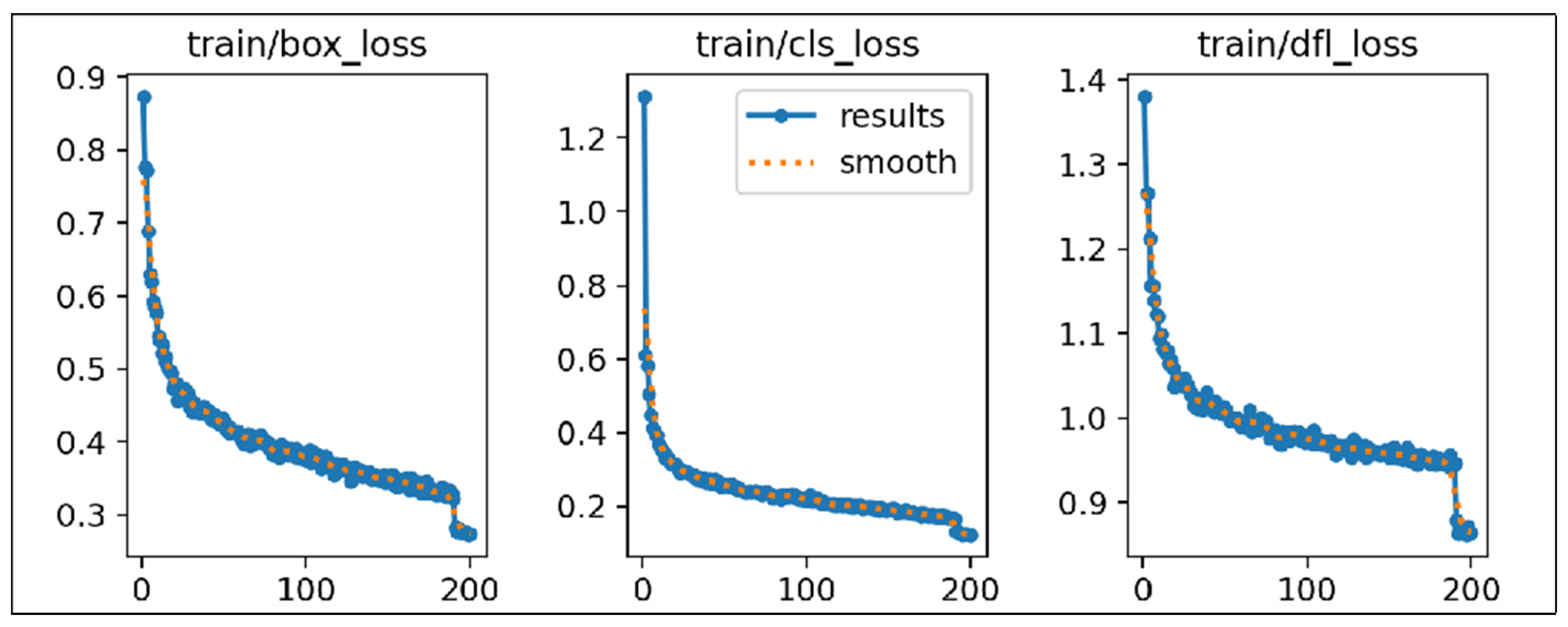

The results obtained from the analysis of the PR graph revealed the optimized performance of the model, with both Precision and Recall values close to 1.0. This result indicates that all positive predictions made by the model were correct, with no False Positives (FP), and that all true instances of the target class were identified, eliminating False Negatives (FN). In the PR graph, the points corresponding to precision = 1 and recall = 1 reflect a perfect match between the model’s predictions and the actual classes present in the test dataset. The absence of False Positives and False Negatives demonstrates the absolute effectiveness of the model in detecting and classifying instances of the analyzed class. This ideal performance suggests that the model has exceptional generalization capabilities, adapting precisely to variations in the input data such as different lighting conditions, viewing angles, and possible occlusions.

However, it is important to highlight that, despite the exceptional performance observed, continuous validation of the model on different datasets and operational conditions is necessary to ensure its generalization and applicability in real-world scenarios. The consistency of these results in various environments strengthens the reliability of the model and its suitability for practical applications that require high precision and reliability for object detection. The dynamics of the PR graph are shown in

Figure 12.

4. Conclusions

A comprehensive analysis of the model performance metrics in this study has revealed significant advancements in the detection and classification of Immature Macauba ("Macuba Imatura") instances. The model showed a substantial reduction in the metric from 0.9 to 0.2, from 1.4 to 0.1, and from 1.4 to 0.8, indicating notable improvements in the accuracy of image localization and classification. The achievement of perfect Precision and Recall (1.0) values in the PR curve demonstrates the effectiveness of the model in eliminating FP and FN, ensuring a perfect match between intraclass predictions. A comparison between models trained with different resolutions and backgrounds showed that the high-resolution model (3456 × 3456 pixels) had a slight advantage in terms of mAP50-95 metrics, reflecting greater robustness. These optimized results not only validate the effectiveness of the preprocessing techniques, neural network architecture, and training strategies used but also establish a solid foundation for the subsequent stages of the project. Thus, a promising initial foundation has been established for the incorporation of new classes, simultaneously contributing to the continuous optimization of sustainability and improved productivity in Macauba cultivation.

Funding

This work was supported by CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel).

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- G. C. M. Aires and R. N. de Carvalho, “Junior., “Potential of supercritical Acrocomia aculeata oil and its technology trends,”,” Appl. Sci. (Basel), vol. 13, no. 15, p. 8594, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Ampese, L. S. L. C. Ampese, L. S. Buller, J. Myers, M. T. Timko, G. Martins, and T. Forster-Carneiro, “Valorization of macauba husks from biodiesel production using subcritical water hydrolysis pretreatment followed by anaerobic digestion,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., vol. 9, no. 4, p. 105656, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. An, K. Q. An, K. Wang, Z. Li, C. Song, X. Tang, and J. Song, “Real-time monitoring method of strawberry fruit growth state based on YOLO improved model,” IEEE Access, vol. 10,124363–124372, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Biesdorf, S. P. E. M. Biesdorf, S. P. Fávaro, L. D. H. C. S. da Conceição, S. F. de Sá, and L. D. Pimentel, “Production and quality of leaf biomass from Acrocomia aculeata for bioenergy,” Ind. Crops Prod., vol. 214, p. 118501, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Casanova-Pérez, P. L. Casanova-Pérez, P. Cruz-Bautista, A. San Juan-Martínez, F. García-Alonso, and F. Barrios, “Underutilized food plants and their potential contribution to food security: Lessons learned from the local context,” Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst., vol. 48, no. 9, pp. 1265–1288, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, J. W. Chen, J. Zhang, B. Guo, Q. Wei, and Z. Zhu, “An apple detection method based on Des-YOLO v4 algorithm for harvesting robots in complex environment,” Math. Probl. Eng., vol. 2021, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ge, S. Y. Ge, S. Lin, Y. Zhang, Z. Li, H. Cheng, J. Dong, et al., “Tracking and counting of tomato at different growth period using an improving YOLO-deepsort network for inspection robot,” Machines (Basel), vol. 10, no. 6, p. 489, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Mirhaji, M. H. Mirhaji, M. Soleymani, A. Asakereh, and S. Abdanan Mehdizadeh, “Fruit detection and load estimation of an orange orchard using the YOLO models through simple approaches in different imaging and illumination conditions,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 191, p. 106533, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Monteiro-Alfredo, J. M. T. Monteiro-Alfredo, J. M. Dos Santos, K. Á. Antunes, J. Cunha, D. da Silva Baldivia, A. S. Pires, et al., “Acrocomia aculeata associated with doxorubicin: Cardioprotection and anticancer activity,” Front. Pharmacol., vol. 14, p. 1223933, Aug. 16 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Montoya, S. Y. S. G. Montoya, S. Y. Motoike, K. N. Kuki, and A. D. Couto, “Fruit development, growth, and stored reserves in macauba palm (Acrocomia aculeata), an alternative bioenergy crop,” Planta, vol. 244, no. 4, pp. 927–938, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. T. Resende, K. N. R. T. Resende, K. N. Kuki, T. R. Corrêa, Ú. R. Zaidan, P. H. S. Mota, L. A. A. Telles, et al., “Data-based agroecological zoning of Acrocomia aculeata: GIS modeling and ecophysiological aspects into a Brazilian representative occurrence area,” Ind. Crops Prod., vol. 154, p. 112749, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, F. C. Zhang, F. Kang, and Y. Wang, “An improved apple object detection method based on lightweight YOLOv4 in complex backgrounds,” Remote Sens. (Basel), vol. 14, no. 17, p. 4150, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).