Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials for SERS Substrate Fabrication

2.2. Characterization

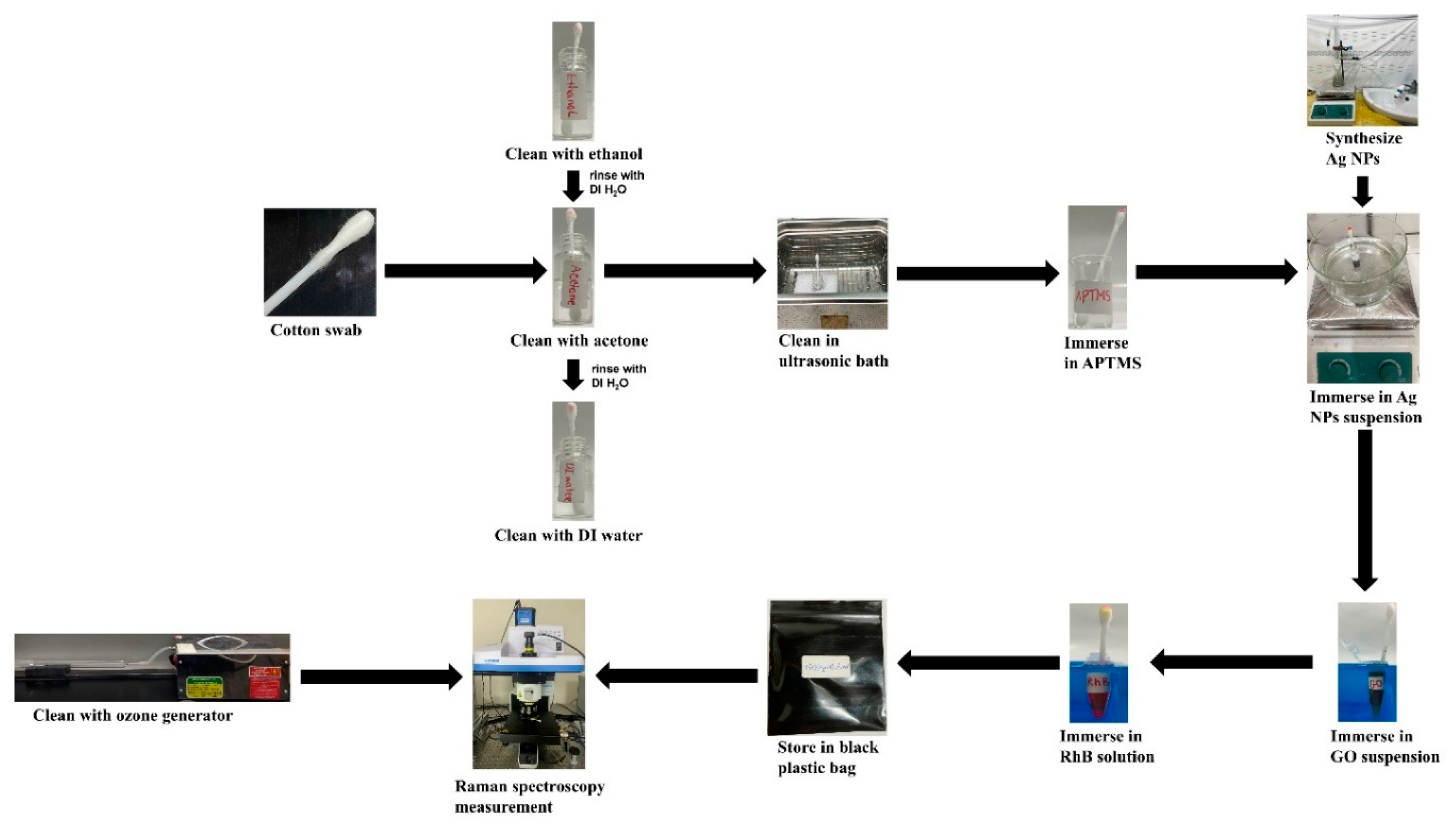

2.3. Methods of SERS Substrate Fabrication

2.4. Performance Tests of SERS Substrates

3. Results and Discussion

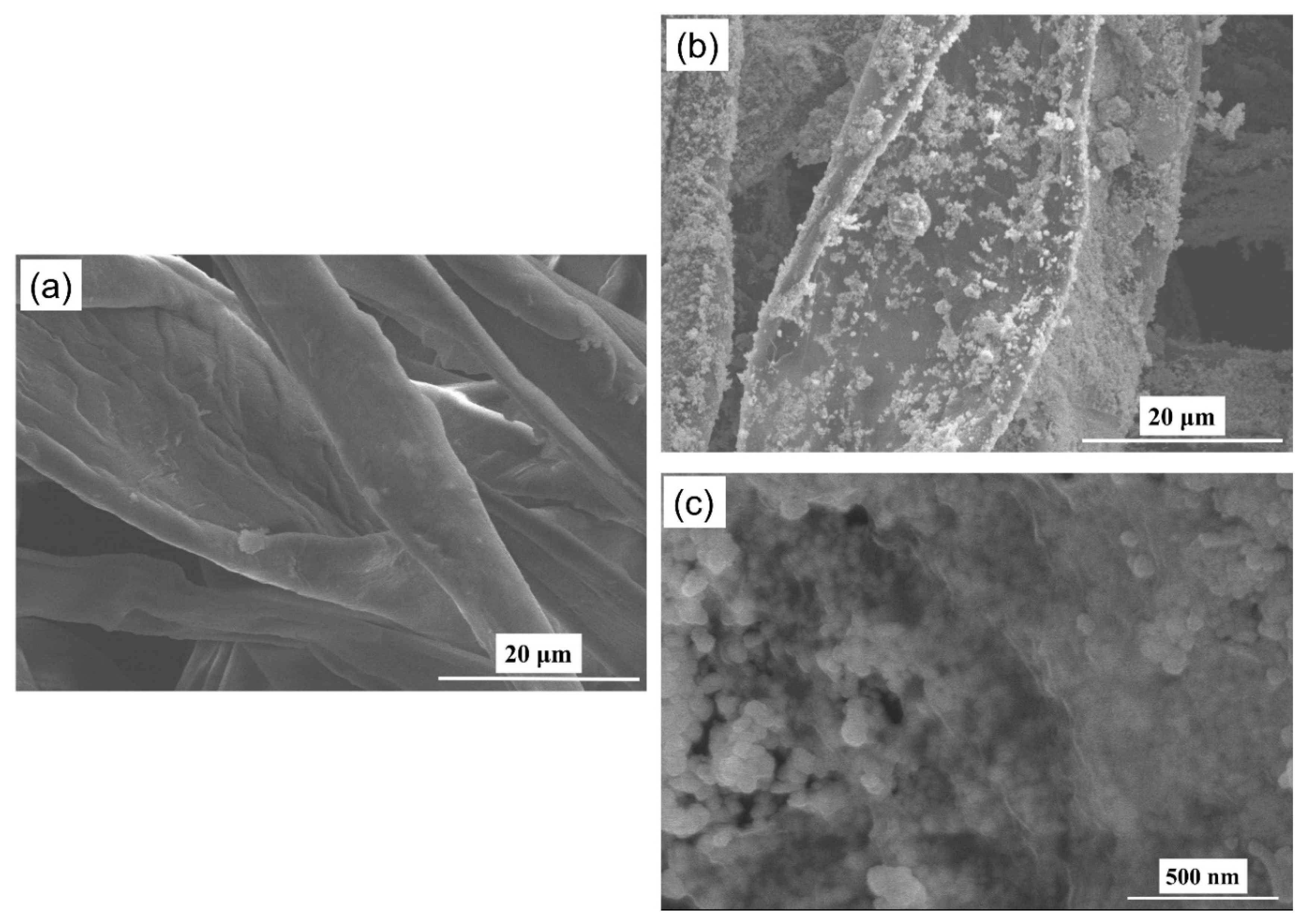

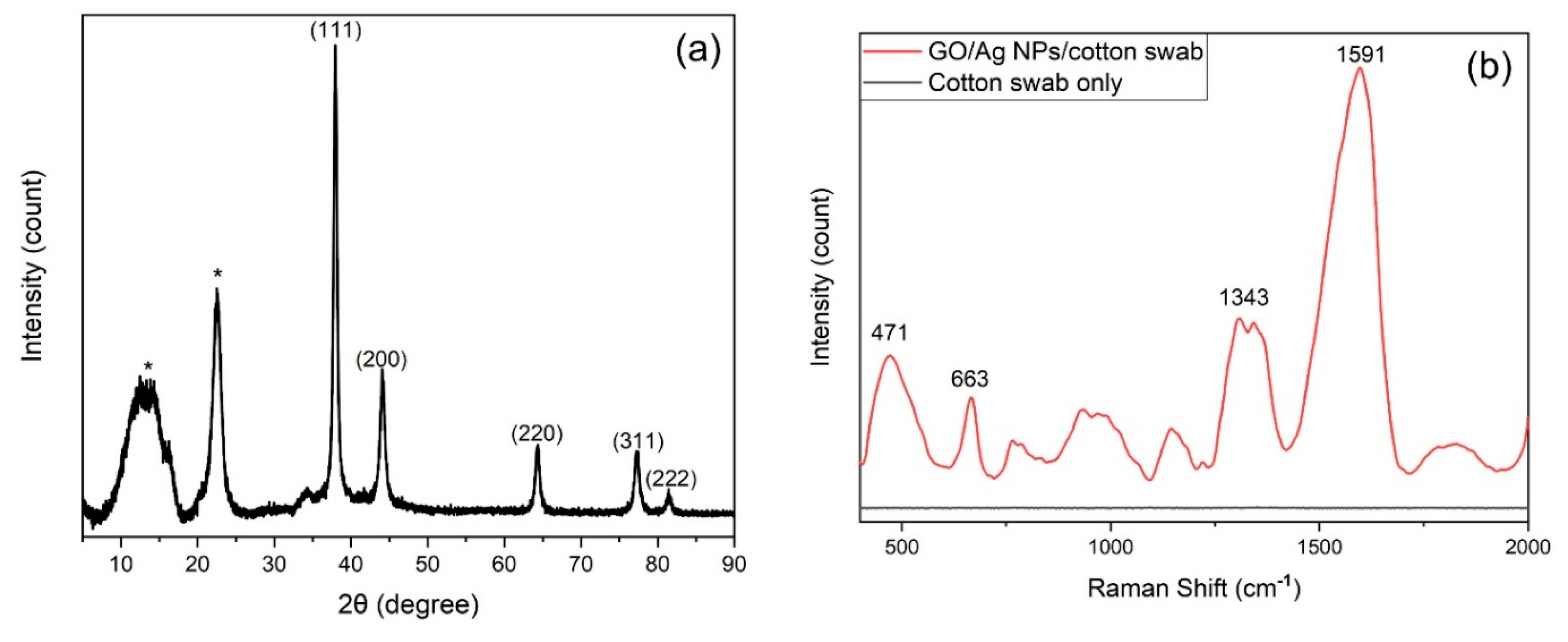

3.1. Characterization of Cotton-Swab Based SERS Substrates

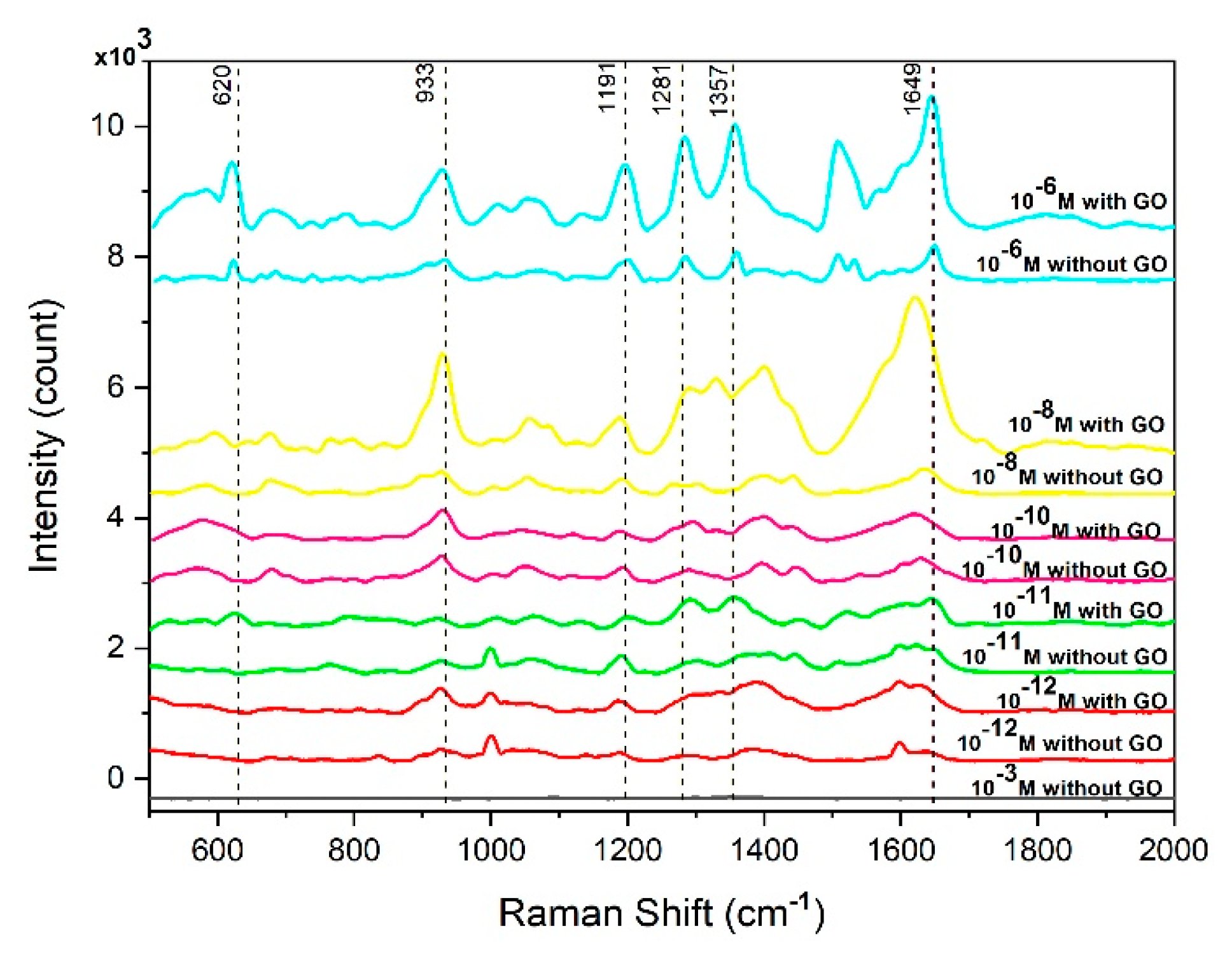

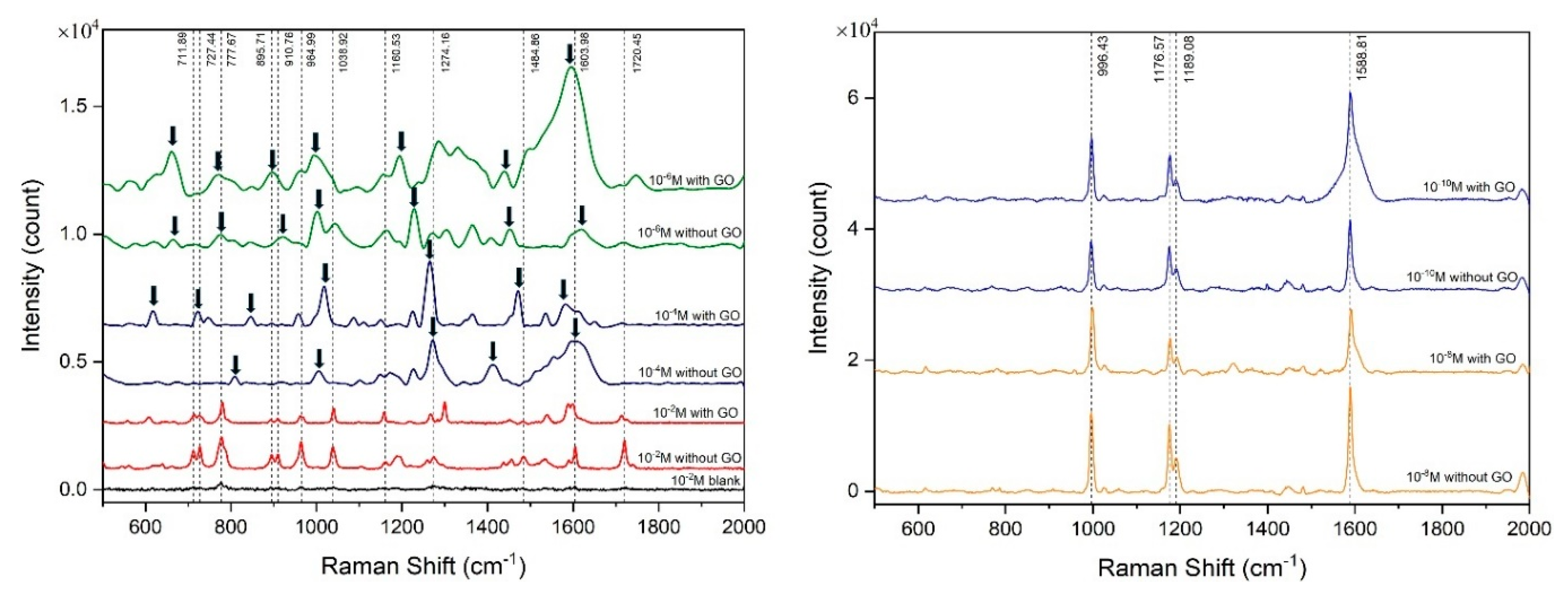

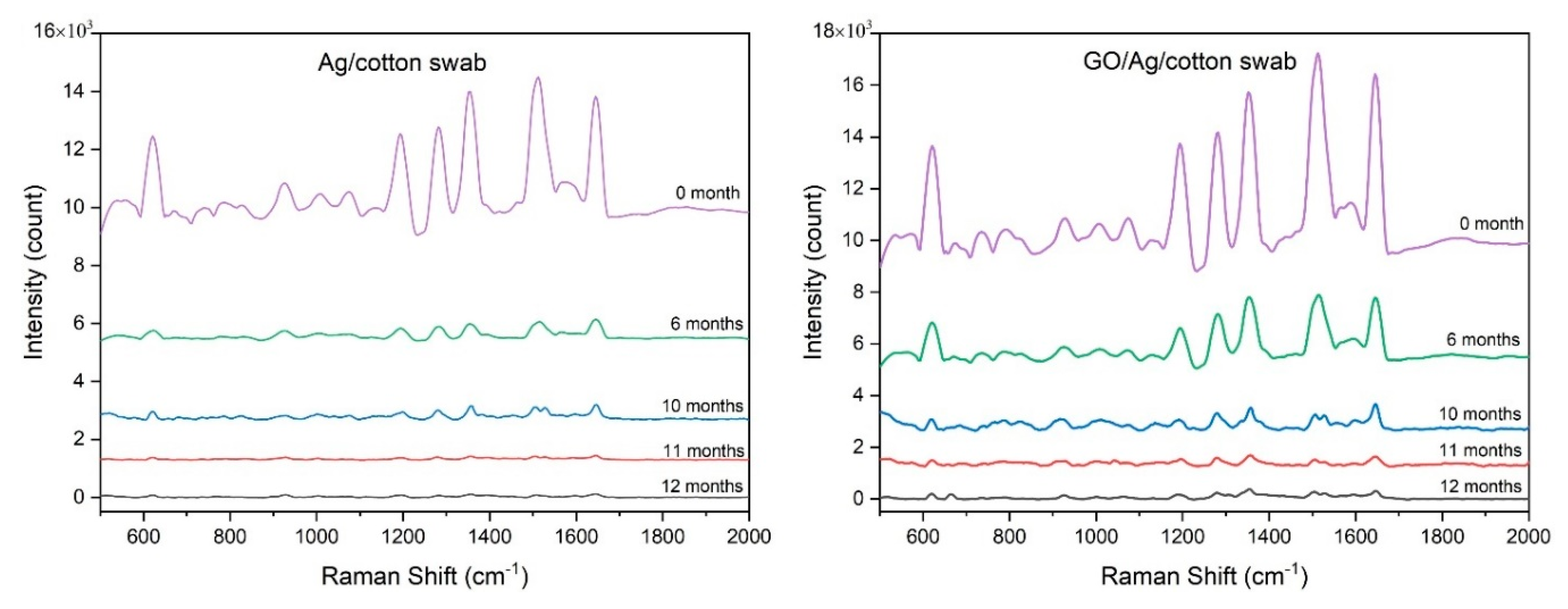

3.2. Performance of Cotton-Swab Based SERS Substrates in Detecting RhB and Thiophanate Methyl

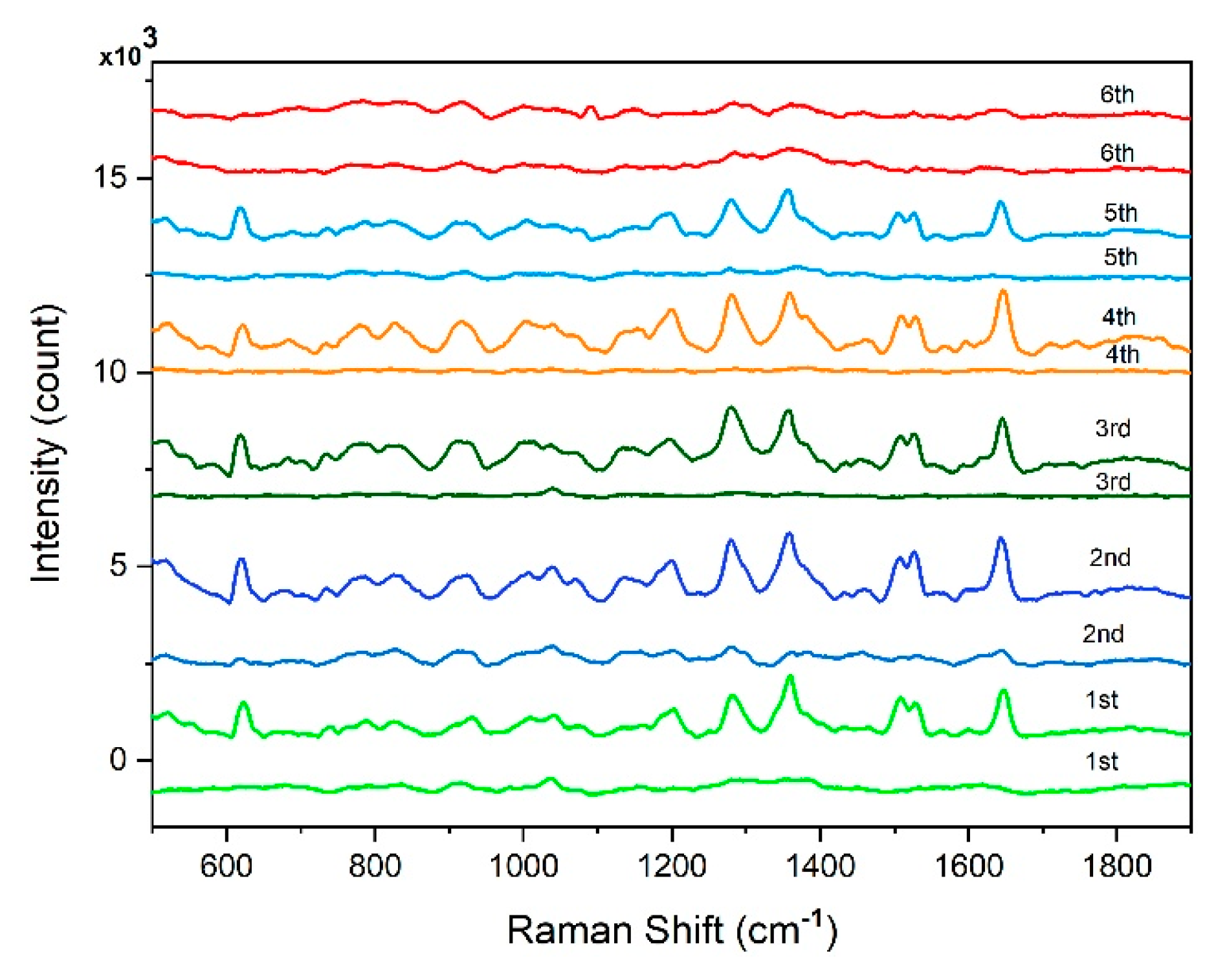

3.3. Investigation Based SERS Substrates

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perez-Jimenez, A.I.; Lyn, D.; Lu, Z.; Liu, G.; Ren, B. Chem Sci 2020, 11(18), 4563-4577.

- Aragay, G.; Pino, F.; Merkoci, A. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5317-5338.

- Xie, W.; Xu, A.; Yeung, E. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 1280-1284.

- Reisch, A.; Elpeleg, O.; Pon, L.; Schon, E. Methods Cell Biol. 2007, 80, 199-222.

- Patra, D.; Mishra, A. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 80, 278-282.

- Hill, H.; Simpson, G. Field Anal. Chem. Technol. 1997, 1, 119-134.

- Hoppmann, E.P.; Yu, W.W.; White, I.M. Methods 2013, 63, 219-224.

- Zhang, X.Y.; Young, M.A.; Lyandres, O.; van Duyne, R.P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4484-4489.

- Nie, S.M.; Emory, S.R. Science 1997, 275, 1102-1106.

- Pieczonka, N.P.W.; Aroca, R.F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 946-954.

- Sharma, B.; Frontiera, R.R.; Henry, A.I.; Ringe, E.; Van Duyne, R.P. Mater. Today 2012, 15(1-2), 16-25.

- Tran, M.; Roy, S.; Kmiec, S.; Whale, A.; Martin, S.; Sundararajan, S.; Padalkar, S. Nanomaterials 2020, 10(4), 644.

- Dao, C.T.; Luong, N.T.Q.; Cao, A.T.; Kieu, M.N. Comm. Phys. 2019, 29(4), 521-526.

- Tran, M.; Whale, A.; Padalkar, S. Sensors 2018, 18(1), 147.

- Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Cui, L.; Ren, B.; Tian, Z. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 1770–1775.

- Yu, X.; Cai, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Pan, N.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Hou, J.G. ACS Nano 2011, 5(2), 952-958.

- Ling, X.; Xie, L.; Fang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Kong, J.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 553-561.

- Liu, Z.M. ; Li, S.X. ; Hu, C.F. ; Zhang, W. ; Zhong, H.Q. ; Guo, Z.Y. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2013, 44, 75-80.

- He, R.; Lai, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, T.; Xie, F.; Chen, Q.; Liu, P.; Chen, J.; Xie, W. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 507, 145116.

- Kim, J.; Jang, Y.; Kim, N.J.; Kim, H.; Yi, G.C.; Shin, Y.; Kim, M.H.; Yoon, S. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 582.

- Sun, L.; Hu, H.; Zhan, D.; Yan, J.; Liu, L.; Teguh, J.S.; Yeow, E.K.L.; Lee, P.S.; Shen, Z. Small 2014, 10(6), 1090-1095.

- Mahmoud, A.Y.F.; Rusin, C.T.; McDermott, M.T. Analyst 2020, 145, 1396-1407.

- Im, H.; Bantz, K.; Lindquist, N.; Haynes, C.; Oh, S. Nano Letters 2010, 10 (6), 2231-2236.

- Wu, Y.; Hang, T.; Komadina, J.; Ling, H.; Li, M. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9720-9726.

- Jiang, X.; Qin, X.; Yin, D.; Gong, M.; Yang, L.; Zhao, B.; Ruan, W. Spectrochimica Acta Part a-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2015, 140, 474-478.

- Huang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Chen, W.; Zhou, P.; Chen, X.; Roy, V. Small 2014, 10 (22), 4645-4650.

- Tran, M.; Fallatah, A.; Whale, A.; Padalkar, S. Sensors 2018, 18(8), 2444.

- Gong, Z.; Du, H.; Cheng, F.; Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Fan, M. Applied Materials & Interfaces 2014, 6, 21931-21937.

- Hoang, M.D.; Nguyen, T.D., Nguyen, C.T.L; Luong, A.D.; Le, L.N.; Tran, K.V.; Huynh, K.C.; Nguyen, K.D.; Tran, M.H. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11(2), 025002.

- Kavitha, C.; Bramhaiah, K.; John, N.S.; Ramachandran, B.E. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2015, 629, 81-86.

- Sun, S.; Wu, P. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 21116-21120.

- Ngo, D.X.; Tran, H.Q.; Le, V.V.; Le, T.T.; Le, T.A. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Devices 2016, 1, 84-89.

- Tran, H.T.; Nguyen, H.M.; Mai, H.H.; Pham, T.V.; Sai, D.C.; Nguyen, B.T.; Pham, H.N.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ho, H.K.; Nguyen, T.V. VNU Journal of Science: Mathematics-Physics 2020, 36(1), 1-6.

- Fang, H.; Zhang, C.X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.M.; Xu, H.J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 64, 434-441.

- Kumar, S.; Lodhi, D.K.; Singh, J.P. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 45120-45126.

- Xu, S.C.; Zhang, Y.X.; Luo, Y.Y.; Wang, S.; Ding, H.L.; Xu, J.M.; Li, G.H. Analyst 2013, 138, 4519-4525.

- Pham, T.N.; Le, H.X.; Dao, T.N.; Nguyen, L.T.; Binard, G.; de Marcillac, W.D.; Maitre, A.; Nguyen, L.Q.; Coolen, L.; Pham, N.T. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 337.

- Gong, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, W.; Quan, J.; Wang, N. Carbon 2015, 87, 385-394.

- Xu, S.; Man, B.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, H.; Gao, S.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Qiu, H. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7(20), 10977-10987.

- Sun, L.; He, J.; An, S.; Zhang, J.; Ren, D. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1046, 74-81.

- He, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 2014(14), 2432-2439.

- Weng, X.; Feng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Feng, J.J.; Hudson, S.P.; Zheng, J.; Ruan, Y.; Laffir, F.; Pita, I. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 5238-5244.

- Lee, P.C.; Meisel, D. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1982, 86 (17), 3391-3395.

- Khai, T.V.; Long, L.N.; Khoi, N.H.T.; Thang, N.H. Crystals 2023, 12, 1825.

- Priya, P.S.; Nandhini, P.P.; Vaishnavi, S.; Pavithra, V.; Almutairi, M.H.; Almutairi, B.O.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Pachaiappan, R.; Arockiaraj, J. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 280, 109898.

- Wang, Y.; Ji, W.; Sui, H.; Kitahama, Y.; Ruan, W.; Ozaki, Y.; Zhao, B. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 10191-10197.

- Zhixun, L.; Yan, F.; Jiannian, Y. Trends in Applied Sciences Research 2007, 2(4), 295-303.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Codex Pesticides Residues in Food Online Database.” Codex Alimentarius – International Food Standards, https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/dbs/pestres/en/. Accessed 12 December 2024.

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Stair, P.C. Catal. Today 2006, 113, 40-47.

- Muehlethaler, C.; Lombardi, J.R.; Leona, M. J. Raman. Spectrosc. 2017, 48(5), 647-652.

- Nguyen, H.T.N; Le, T.N.T.; Nguyen, P.T.P; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, T.L.M. Sensors 2020, 20, 2229.

- Li, J.L.; Sun, D.W.; Pu, H. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 543-552.

- Lim, S.; Shi, J.L.; von Gunten, U.; McCurry, D.L. Water Res. 2022, 213, 118053.

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Assignment |

| 1644 | Aromatic C-C stretch |

| 1591 | C-H stretch |

| 1551 | Aromatic C-C stretch |

| 1528 | C-H stretch |

| 1508 | Aromatic C-C stretch |

| 1426 | C-H stretch |

| 1360 | Aromatic C-C stretch |

| 1284 | Aromatic C-C stretch |

| 1199 | C-H in-plane bend |

| 1130 | C-H stretch |

| 932 | C-H stretch |

| 773 | C-H stretch |

| 622 | C-C-C stretch |

| 355 | |

| 278 | |

| 240 | Ag-N stretch |

| 213 |

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Assignment |

| 325 | C-C stretching |

| 465 | C-O-C deformation |

| 613 | -N-C=S deformation |

| 717 | C-H deformation, N-H bending |

| 726 | N-H wagging |

| 779 | C=S stretching, N-H deformation, C-H deformation |

| 898 | C-S stretching, C-H deformation |

| 959 | C=S stretching, C-H deformation |

| 1039 | C-H deformation, C-O stretching |

| 1154 | N-C-N asymmetric stretching, -CH3 deformation, C-C stretching |

| 1267 | C-O stretching, N-H deformation, C-H deformation |

| 1298 | C-O-C stretching, N-H deformation, C-H deformation |

| 1538 | C-N stretching, N-H deformation |

| 1601 | C=C stretching, N-H deformation, C-H deformation |

| 1708 | C=O stretching, N-H stretching, N-H deformation, -CH3 deformation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).