Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

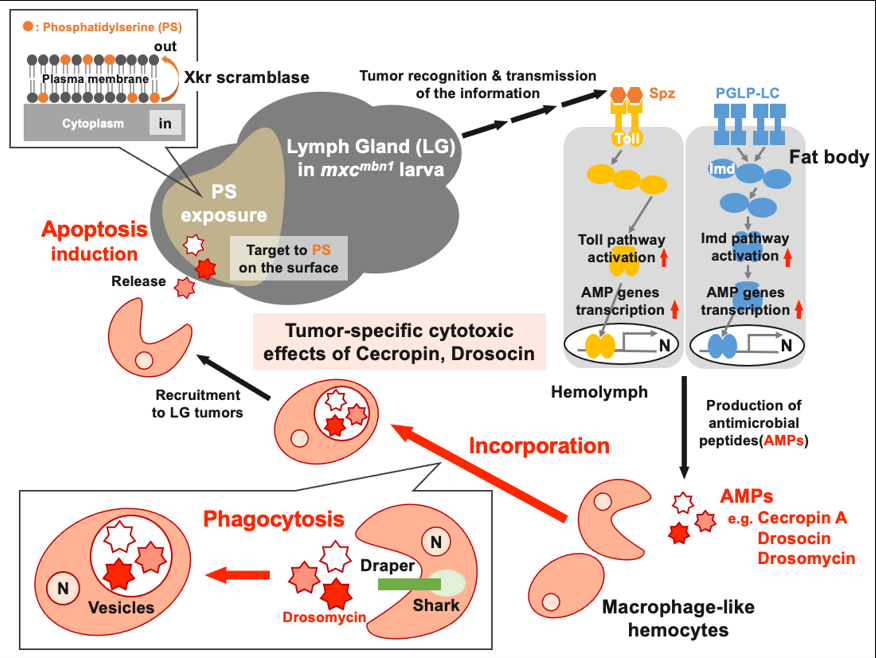

Five major antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in <i>Drosophila</i> are induced in <i>multiple sex combs</i> (<i>mxc</i>) mutant larvae harboring lymph gland (LG) tumors and exhibit anti-tumor effects. The effects of the other well-known AMPs, Cecropin A and Drosocin, remain unelucidated. We investigated the tumor-elimination mechanism of these AMPs. A half-dose reduction of either <i>Toll</i> or <i>Imd</i> gene reduced the AMPs’ induction in the fat body and enhanced tumor growth in <i>mxc<sup>mbn1</sup></i> mutant larvae, indicating that their anti-tumor effects depend on the innate immune pathway. Overexpression of these AMPs in the fat body suppressed tumor growth without affecting cell proliferation. Apoptosis was significantly promoted in the mutant LGs but not in normal tissues. Conversely, their knockdown inhibited apoptosis and enhanced tumor growth. Therefore, these AMPs inhibit LG tumor growth by inducing apoptosis. The AMPs from the fat body were incorporated into hemocytes of mutant but not normal larvae. Another AMP, Drosomycin, was taken up via phagocytosis factors. Enhanced phosphatidylserine signals were observed on the tumor surface. Inhibition of the cell-surface exposed signals impeded tumor growth suppression. AMPs may target phosphatidylserine in the tumors for apoptosis induction to execute tumor-specific effects. AMPs are potentially beneficial anti-cancer drugs with minimal side effects for clinical development.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drosophila stocks

2.2. Germline transformation

2.3. Visualization of AMP gene expression in Drosophila larvae using Green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter

2.4. Preparation of fixed samples to measure LG size

2.5. LG immunostaining

2.6. Detection of Phosphatydilserine (PS) exposed on the cell membrane surface in LG

2.7. Immunostaining of circulating hemocytes

2.8. Microinjection of synthetic cecropin A peptides

2.9. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

2.10. Statistical analysis

3. Results

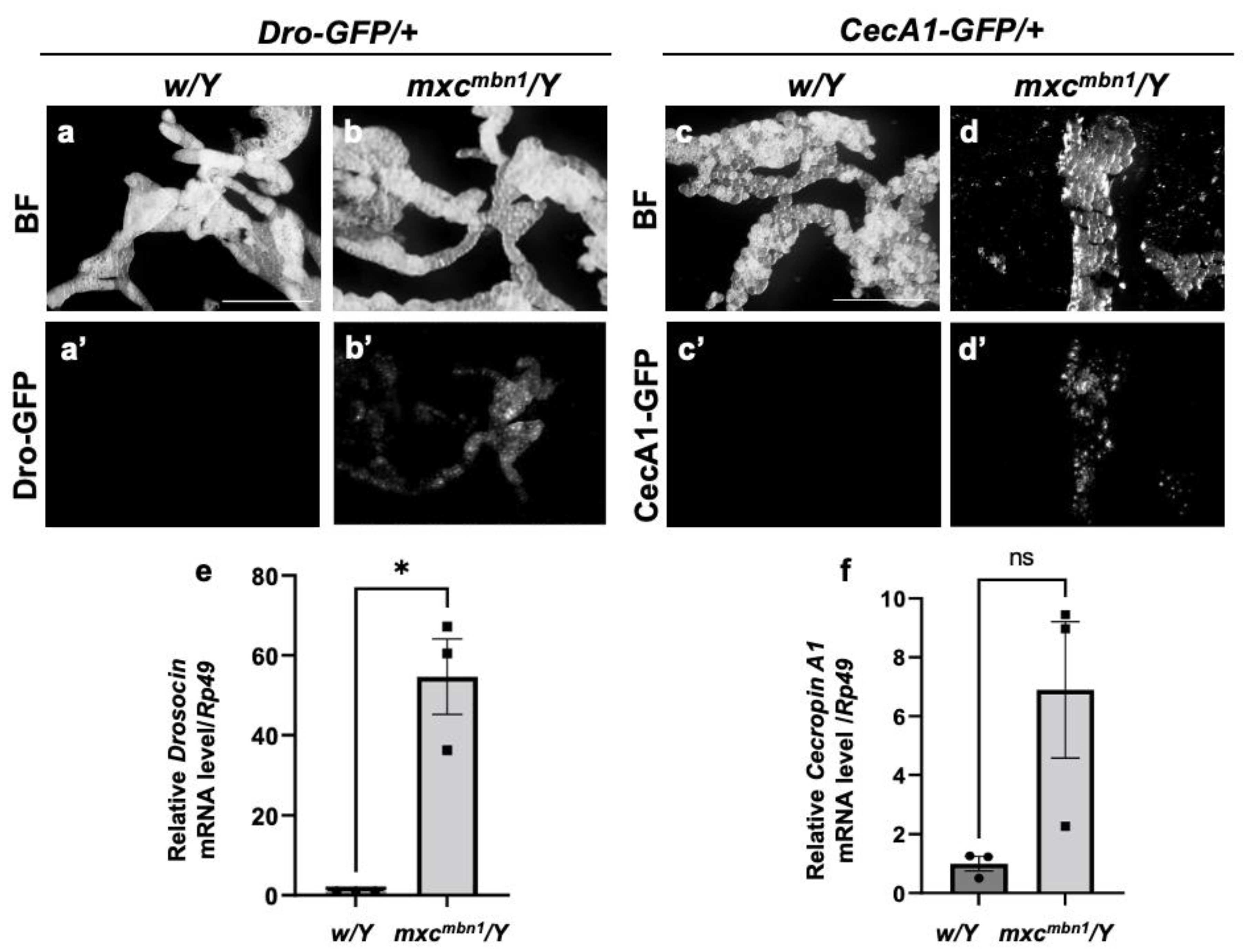

3.1. Induction of AMP genes encoding Drosocin and Cecropin A in the fat body of mxcmbn1 mutant larvae

3.2. Dro and CecA1 mRNA level declines and LG hyperplasia enhancement in mxcmbn1 larvae by half-dose reduction of the genes encoding the innate immune pathway factors

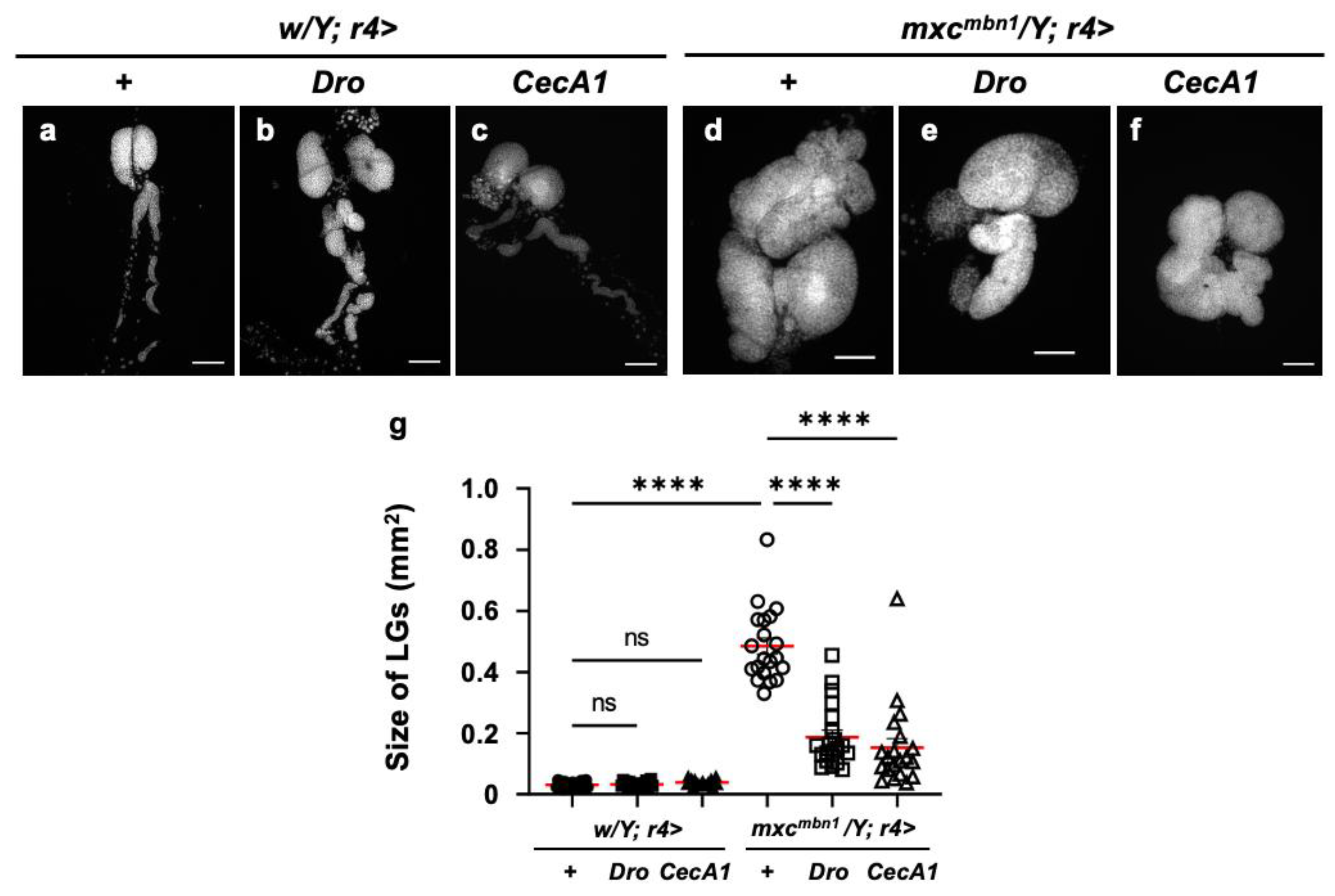

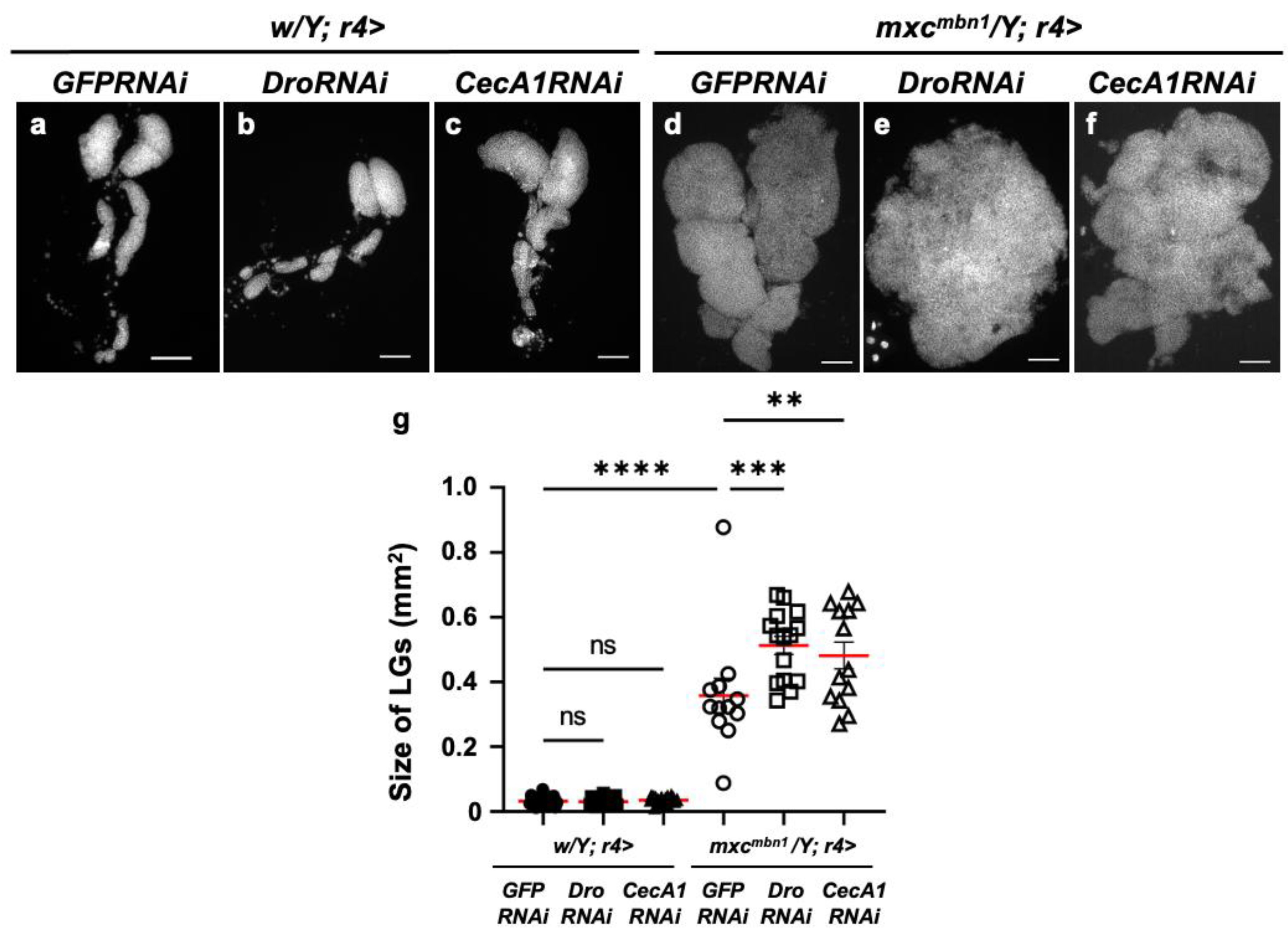

3.3. LG hyperplasia suppression in mxcmbn1 larvae by overexpression of Dro or CecA1 gene in the fat body

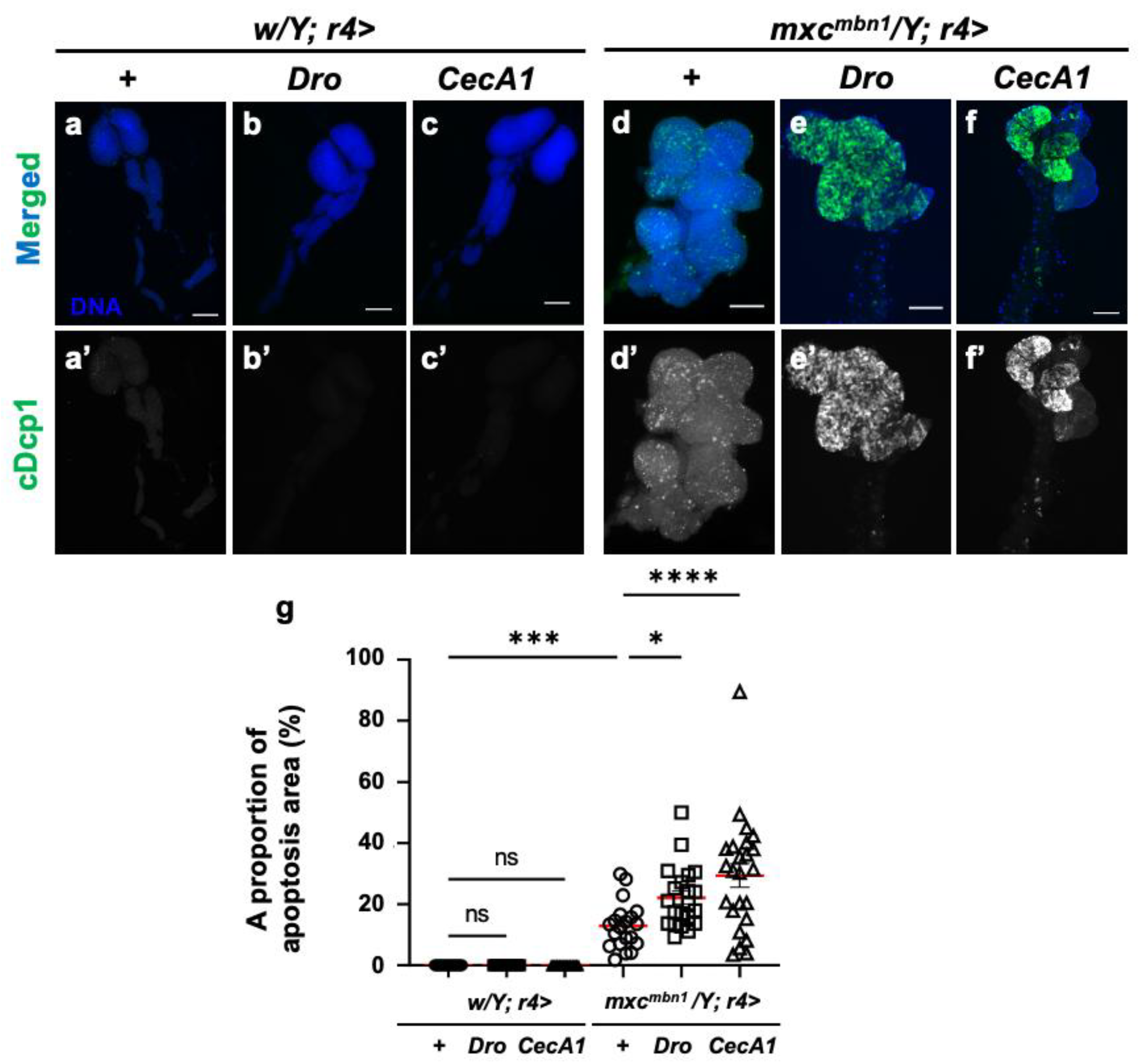

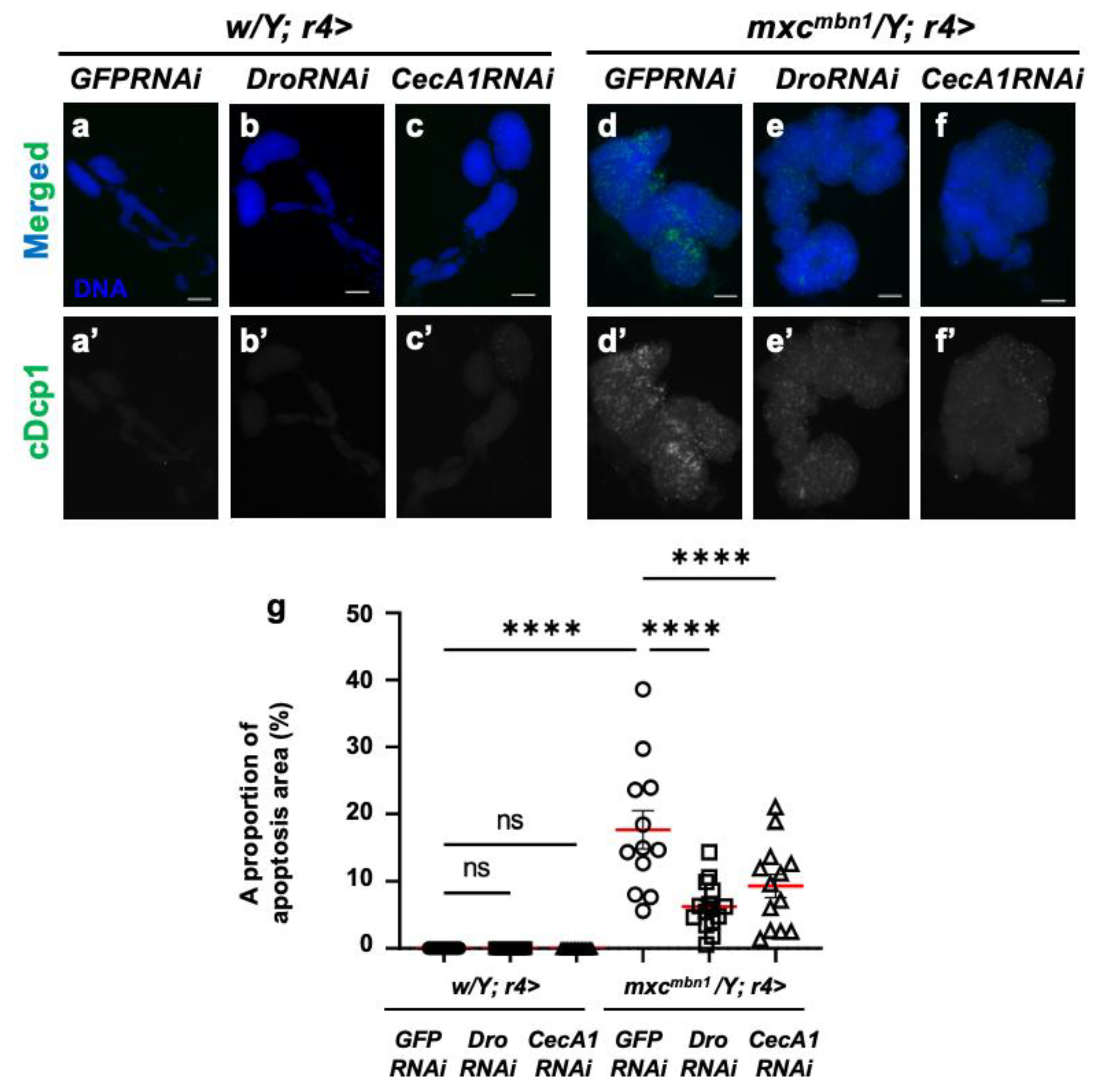

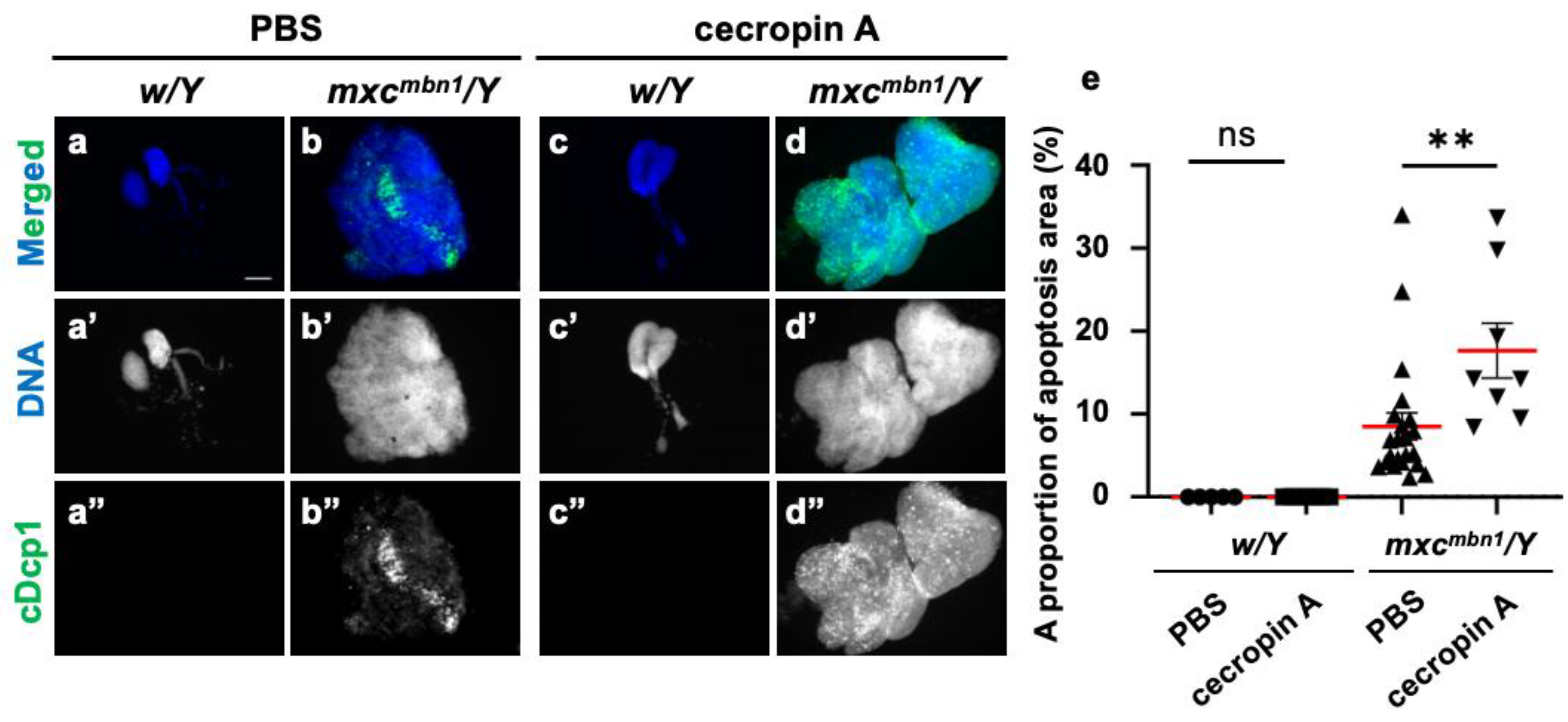

3.4. Dro or CecA1 overexpression in the fat body enhanced apoptosis in the LG tumors of mxcmbn1 larvae

3.5. Dro or CecA1 knockdown in the fat body enhanced LG hyperplasia and suppressed apoptosis in LG tumors in mxcmbn1 larvae

3.6. Dro or CecA1 overexpression in the fat body did not affect cell proliferation in the LGs of mxcmbn1 larvae

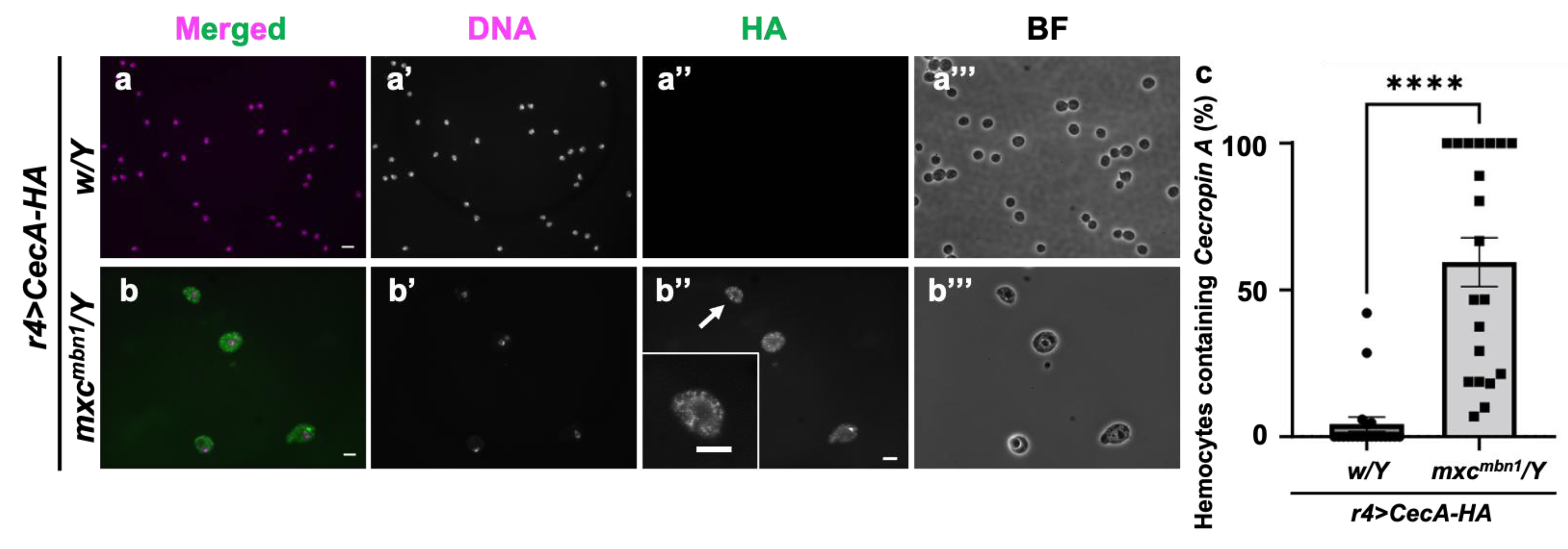

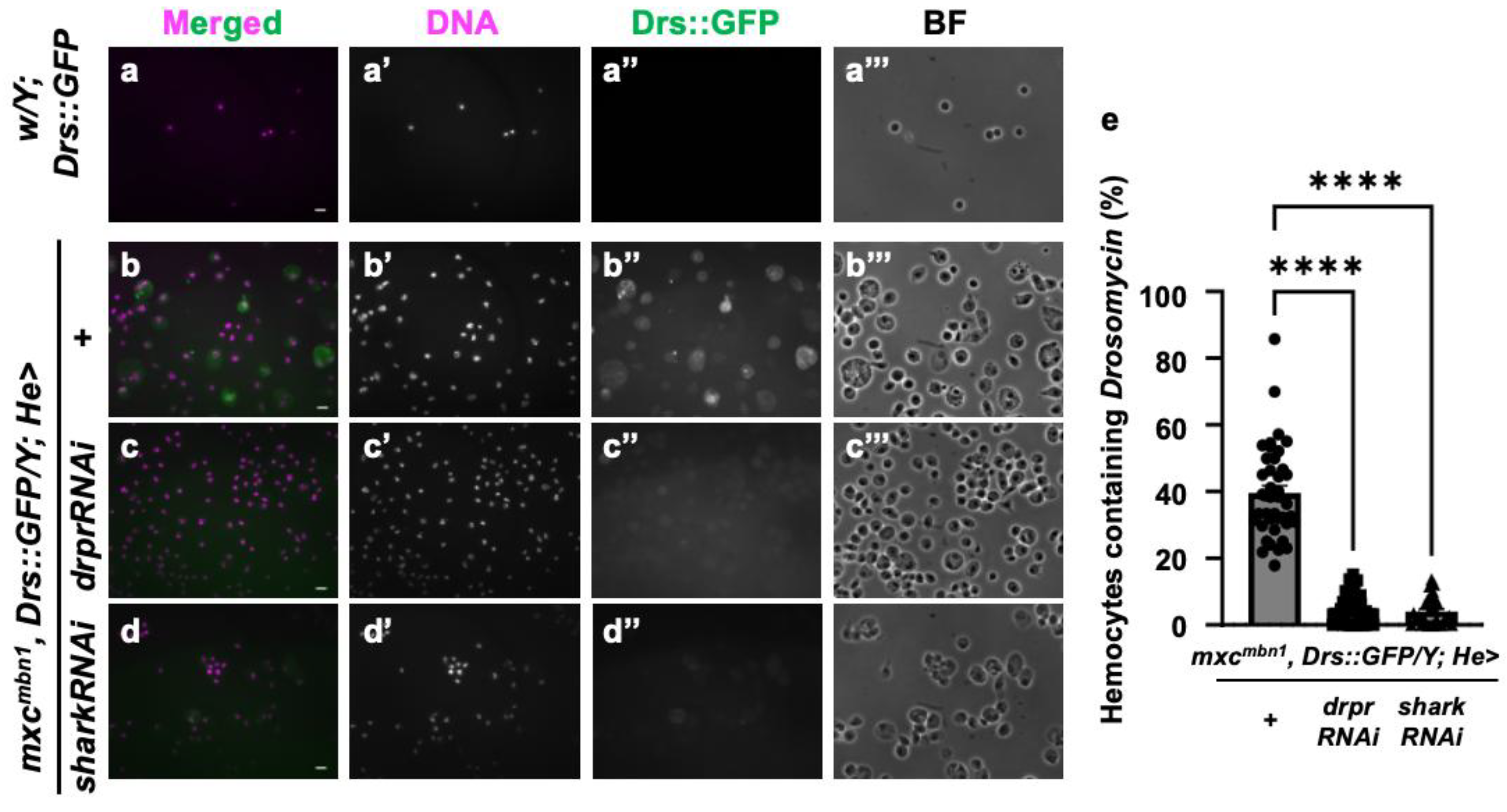

3.7. Incorporation of Cecropin A into the circulating hemocytes in tumor-bearing mxcmbn1 but not in control larvae

3.8. Drosomycin incorporation into the hemocytes required Draper signaling in mxcmbn1 larvae

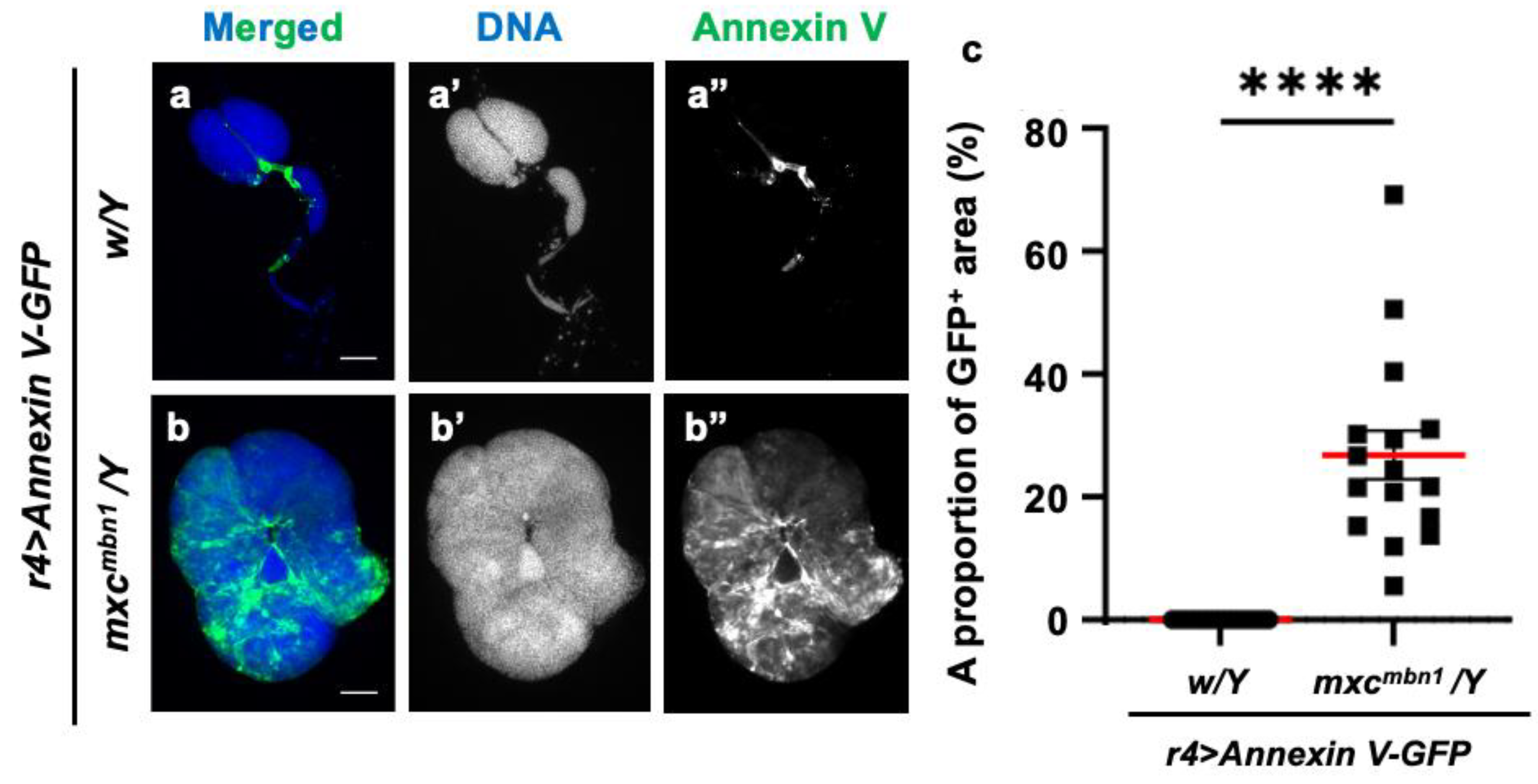

3.9. Phosphatidylserine localization on the plasma membrane surface in LG tumors

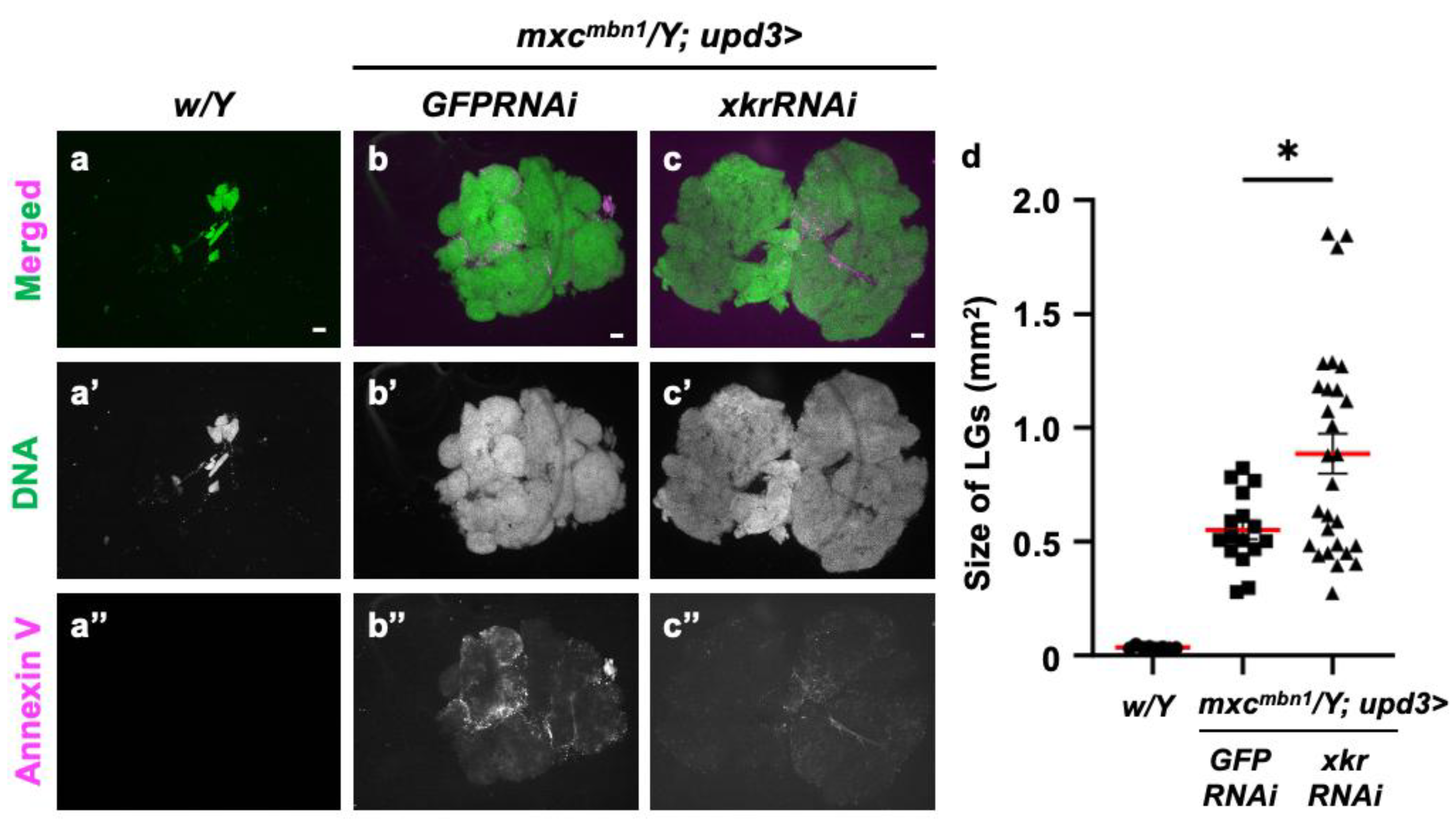

3.10. Xkr scramblase knockdown canceled PS localization on the surface of LG cells and led to LG hyperplasia enhancement in mxcmbn1

4. Discussion

4.1. Cecropin A and Drosocin induction via the innate immune pathways in the fat body of mxcmbn1 mutant larvae bearing the LG tumors

4.2. Cytotoxic effects of Cecropin A and Drosocin on tumors in Drosophila larvae

4.3. Tumor-specific effect of Cecropin A and Drosocin on LG tumors in mxcmbn1 larvae may be determined by the circulating hemocytes that take up AMPs

4.4. Restrictive anti-cancer effects of AMPs on the LG tumor cells in which PS was exposed on the plasma membrane surface

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lemaitre, B.; Hoffmann, J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 697–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.; Kupper, T. Old meets new: The interaction between innate and adaptive immunity. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willermain, F.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; Bodaghi, B.; Rosenzweig, H.L.; Childers, S.; Behrend, T.; Wildner, G.; Dick, A.D. Interplay between innate and adaptive immunity in the development of non-infectious uveitis. Prog. Retin. Eye. Res. 2012, 31, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, E.; Reichhart, J.M.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Lemaitre, B. In vivo regulation of the IκB homologue Cactus during the immune response of Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 10463–10469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, A.; Anderson, V. Drosophila: the genetics of innate immune recognition and response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 22, 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.A. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature 2003, 426, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, V. , and Reichhart, J.-M. The immune response of Drosophila melanogaster. Immunol. Rev. 2004, 198, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.A.; Reichhart, J.-M. Drosophila innate immunity: an evolutionary perspective. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, P.; Reichhart, J.-M.; Lemaitre, B. Constitutive expression of a single antimicrobial peptide can restore wild-type resistance to infection in immunodeficient Drosophila mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002, 99, 2152–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, B.; Reichhart, J.-M.; Hoffmann, J.A. Drosophila host defense: Differential induction of antimicrobial peptide genes after infection by various classes of microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 14614–14619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.A.; Wasserman, S.A. Conventional and non-conventional Drosophila Toll signaling. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 42, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobert, V.; Gottar, M.; Matskevich, A.A.; Rutschmann, S.; Royet, J.; Belvin, M.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Ferrandon, D. Dual activation of the Drosophila Toll pathway by two pattern recognition receptors. Science 2003, 302, 2126–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottar, M.; Gobert, V.; Matskevich, A.A.; Reichhart, J.-M.; Wang, C.; Butt, T.M.; Belvin, M.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Ferrandon, D. Dual detection of fungal infections in Drosophila via recognition of glucans and sensing of virulence factors. Cell 2006, 127, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valanne, S.; Wang, J.-H.; Rämet, M. The Drosophila Toll signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Bristow, B.N.; Qu, G.; Wasserman, S.A. A heterotrimeric death domain complex in Toll signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 12871–12876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottar, M.; Gobert, V.; Michel, T.; Belvin, M.; Duyk, G.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Ferrandon, D.; Royet, J. The Drosophila immune response against Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by a peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature 2002, 416, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleino, A.; Silverman, N. The Drosophila IMD pathway in the activation of the humoral immune response. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 42, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchon, N.; Silverman, N.; Cherry, S. Immunity in Drosophila melanogaster — from microbial recognition to whole-organism physiology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk-Hasdemir, D.; Broemer, M.; Leulier, F.; Lane, W.S.; Paquette, N.; Hwang, D.; Kim, C.-H.; Stöven, S.; Meier, P.; Silverman, N. Two roles for the Drosophila IKK complex in the activation of Relish and the induction of antimicrobial peptide genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 9779–9784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleino, A.; Silverman, N. The Drosophila IMD pathway in the activation of the humoral immune response. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 42, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanji, T.; Ip, Y.T. Regulators of the Toll and Imd pathways in the Drosophila innate immune response. Trends Immunol. 2005, 26, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultmark, D.; Steiner, H.; Rasmuson, T.; Boman, H.G. Insect immunity. purification and properties of three inducible bactericidal proteins from hemolymph of immunized pupae of Hyalophora cecropia. Eur. J. Biochem. 1980, 106, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.M.; Wang, W.; Smith, D.; Chan, S.C. Effects of the anti-bacterial peptide cecropin B and its analogs, cecropins B-1 and B-2, on liposomes, bacteria, and cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997, 1336, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.C.; Hui, L.; Chen, H.M. Enhancement of the cytolytic effect of anti-bacterial cecropin by the microvilli of cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 1998, 18, 4467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.J.; Devine, D.A.; Bibby, M.C. Preliminary experimental anticancer activity of cecropins. Pept. Res. 1994, 7, 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Araki, M.; Kurihara, M.; Kinoshita, S.; Awane, R.; Sato, T.; Ohkawa, Y.; Inoue, Y.H. Anti-tumour effects of antimicrobial peptides, components of the innate immune system, against hematopoietic tumors in Drosophila mxc mutants. Dis. Model. Mech. 2019, 12, dmm037721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, B.; Kunc, M.; Krautz, R.; Theopold, U. The immune phenotype of three Drosophila leukemia models. G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 2017, 7, 2139–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, F.; Stefanatos, R.K.; Strathdee, K.; Yu, Y.; Vidal, M. Transformed epithelia trigger non-tissue-autonomous tumor suppressor response by adipocytes via activation of Toll and Eiger/TNF signaling. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvy, J.-P.; Yu, Y.; Dostalova, A.; Kondo, S.; Kurjan, A.; Bulet, P.; Lemaître, B.; Vidal, M.; Cordero, J.B. The antimicrobial peptide Defensin cooperates with Tumour Necrosis Factor to drive tumor cell death in Drosophila. eLife 2019, 8, e45061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebestky, T.; Chang, T.; Hartenstein, V.; Banerjee, U. Specification of Drosophila hematopoietic lineage by conserved transcription factors. Science 2000, 288, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanche Bosch, P.; Makhijani, K.; Herboso, L.; Gold, KS.; Baginsky, R.; Woodcock, KJ.; Alexander, B.; Kukar, K.; Corcoran, S.; Jacobs, T.; Ouyang, D.; Wong, C.; Ramond, EJV. ; Rhiner, C.; Moreno, E.; Lemaitre, B.; Geissmann, F.; Brückner, K. Adult Drosophila lack hematopoiesis but rely on a blood cell reservoir at the respiratory epithelia to relay infection signals to surrounding tissues. Dev. Cell 2019, 51, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, J.; Kinoshita, Y.; Nomura, T.; Inoue, Y.H. Macrophage-like blood cells are involved in inter-tissue communication to activate JAK/STAT signaling, inducing antitumor Turandot proteins in Drosophila fat body via the TNF-JNK pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, J.B.; Macagno, J.P.; Stefanatos, R.K.; Strathdee, K.E.; Cagan, R.L.; Vidal, M. Oncogenic Ras diverts a host TNF tumor suppressor activity into tumor promoter. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S.; Takarada, K.; Kinoshita, Y.; Inoue, Y.H. Drosophila hemocytes recognize lymph gland tumors of mxc mutants and activate the innate immune pathway in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Biol. Open 2022, 11, bio059523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Pareja, J.C.; Wu, M.; Xu, T. An innate immune response of blood cells to tumors and tissue damage in Drosophila. Dis. Model. Mech. 2008, 1, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, M.; Komatsu, K.; Awane, R.; Inoue, Y.H. Loss of histone locus bodies in the mature hemocytes of larval lymph gland result in hyperplasia of the tissue in mxc mutants of Drosophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remillieux-Leschelle, N. , Santamaria, P., and Randsholt, N.B. Regulation of larval hematopoiesis in Drosophila melanogaster: a role for the multi sex combs gene. Genetics 2002, 162, 1259–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takarada, K.; Kinoshita, J.; Inoue, Y.H. Ectopic expression of matrix metalloproteinases and filopodia extension via JNK activation are involved in the invasion of blood tumor cells in Drosophila mxc mutant. Genes. Cells. 2023, 28, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzou, P.; Ohresser, S.; Ferrandon, D.; Capovilla, M.; Reichhart, J.-M.; Lemaitre, B.; Hoffmann, J.A.; Imler, J.-L. Tissue-specific inducible expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Drosophila surface epithelia. Immunity 2000, 13, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, Y.; Lim, Y.-M.; Tsuda, L.; Nishida, Y. fat facets induce polyubiquitination of Imd and inhibits the innate immune response in Drosophila. Genes Cells. 2013, 18, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnorrer, F.; Schönbauer, C.; Langer, C.C.; Dietzl, G.; Novatchkova, M.; Schernhuber, K.; Fellner, M.; Azaryan, A.; Radolf, M.; Stark, A.; Keleman, K.; Dickson, B.J. Systematic genetic analysis of muscle morphogenesis and function in Drosophila. Nature. 2010, 2010. 464, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, A.; Tatsutomi, I.; Saito, K.; Murata, M.; Hattori, I.; Kajita, H.; Muraki, N.; Oda, Y.; Satoh, S.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Kimura, S.; Onoue, K.; Yonemura, S.; Arakawa, S.; Kato, H.; Hirashima, T.; Kawane, K. Apoptotic extracellular vesicle formation via local phosphatidylserine exposure drives efficient cell extrusion. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 1282–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Beach, M.G.; Porpiglia, E.; Sheehan, A.E.; Watts, R.J.; Freeman, M.R. The Drosophila cell corpse engulfment receptor Draper mediates glial clearance of severed axons. Neuron 2006, 50, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badinloo, M.; Nguyen, E.; Suh, W.; Alzahrani, F.; Castellanos, J.; Klichko, VI.; Orr,WC. ; Radyuk, SN. Overexpression of antimicrobial peptides contributes to aging through cytotoxic effects in Drosophila tissues. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 98, e21464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapar, M.L.; Ji, H.; Wang, B.; Poe, A.R.; Dubey, K.; Ren, X.; Ni, J.Q.; Han, C. Phosphatidylserine externalization results from and causes neurite degeneration in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 2273–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, S.; Hirai, J.; Yasukawa, T.; Nakahara, Y.; Inoue, Y.H. A correlation of reactive oxygen species accumulation by depletion of superoxide dismutases with age-dependent impairment in the nervous system and muscles of Drosophila adults. Biogerontol. 2015, 16, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimels, TA.; Pfleger, CM. Methods to examine the lymph gland and hemocytes in Drosophila larvae. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 117, 54544. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C.J.; Hartenstein, V.; Banerjee, U. Thicker than blood: conserved mechanisms in Drosophila and vertebrate hematopoiesis. Dev. Cell 2003, 5, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-H.; Evans, C.J.; Uemura, C.; Banerjee, U. The Drosophila lymph gland as a developmental model of hematopoiesis. Development 2005, 132, 2521–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, R.; Jitaru, D.; Bădescu, L.; Bădescu, M.; Ciocoiu, M. The cytotoxic effect of magainin II on the MDA-MB-231 and M14K tumour cell lines. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 831709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiomi, A.; Nagao, K.; Yokota, N.; Tsuchiya, M.; Kato, U.; Juni, N.; Hara, Y.; Mori, MX.; Mori, Y.; Ui-Tei, K.; Murate, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Nishino, Y.; Miyazawa, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Suzuki, R.; Kaufmann, S.; Tanaka, M.; Tatsumi, K.; Nakabe, K.; Shintaku, H.; Yesylevsky, S.; Bogdanov, M.; Umeda, M. Extreme deformability of insect cell membranes is governed by phospholipid scrambling. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diefenbach, A.; Tomasello, E.; Lucas, M.; Jamieson, A.M.; Hsia, J.K.; Vivier, E.; Raulet, D.H. Selective associations with signaling proteins determine stimulatory versus costimulatory activity of NKG2D. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Pagès, F.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012, 12, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, R.D. ; Old. L.J.; Smyth, M.J. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011 331, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbasi, A.; June, C.H.; Haas, N.; Vapiwala, N. Radiation and immunotherapy: A synergistic combination. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, T.-J.; Sup Shim, M.; Bang, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Jae Lee, B. SPS1 deficiency-triggered PGRP-LC and Toll expression controls innate immunity in Drosophila S2 Cells. Biol. Open 2022, 11, bio059295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, Y.; Shiratsuchi, N.; Araki, M.; Inoue, Y.H. Anti-tumor effect of Turandot proteins induced via the JAK/STAT pathway in the mxc hematopoietic tumor mutant in Drosophila. Cells, 2023, 12, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Mei, H.; Li, X.; Ma, Y. ; Zeng AH, Wang, Y. Apoptosis-inducing activity of the antimicrobial peptide Cecropin of Musca domestica in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line BEL-7402 and the possible mechanism. Acta. Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2010, 259–265.

- Sang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhuge, Q. Selective cytotoxicity of the antibacterial peptide ABP-dHC-Cecropin A and its analog towards leukemia cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 803, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gallo, R.L. Antimicrobial peptides. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, R14–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.; Grapputo, A.; Romoli, O.; Sandrelli, F. Insect Cecropins, antimicrobial peptides with potential therapeutic applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaja, M.; Dziedzic, A.; Szafraniec, K.; Piastowska-Ciesielska, A. Cecropins in cancer therapies-where we have been? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 882, 173317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskin, D.W.; Ramamoorthy, A. Studies on anticancer activities of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2008, 1778, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serizier, S.B.; Peterson, J.S.; McCall, K. Non-autonomous cell death induced by the Draper phagocytosis receptor requires signaling through the JNK and SRC pathways. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs250134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacino, J.S.; Glick, B.S. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 2004, 116, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandala, T.; Brooks, D.A. Innate immunity and exocytosis of antimicrobial peptides. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2012, 5, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, M.J.; Lindsay, A.J. The endosomal recycling pathway-at the crossroads of the cell. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, P.; Zorec, R.; Rettig, J.; Keating, D.J. Exocytosis in non-neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 2016, 137, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, F. Cationic amphiphilic peptides with cancer-selective toxicity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 625, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daleke, D.L. Phospholipid flippases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevers, E.M.; Williamson, P.L. Phospholipid scramblase: an update. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2724–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Ishibashi, J.; Tanaka, H.; Sato, M.; Asaoka, A.; Taylor, D.; Yamakawa, M. Selective cancer cell cytotoxicity of enantiomeric 9-Mer peptides derived from beetle Defensins depends on negatively charged phosphatidylserine on the cell surface. Peptides 2009, 30, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mader, J.S.; Hoskin, D.W. Cationic antimicrobial peptides as novel cytotoxic agents for cancer treatment. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2006, 15, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, S.; Rinner, B.; Asslaber, M.; Schaider, H.; Walzer, S.; Novak, A.; Lohner, K.; Zweytick, D. In Search of a Novel Target — Phosphatidylserine exposed by non-apoptotic tumor cells and metastases of malignancies with poor treatment efficacy. Biochimi. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2011, 1808, 2638–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Ding, J.; Liao, C.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, W. Defensins: The natural peptide antibiotic. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 179, 114008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).