Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

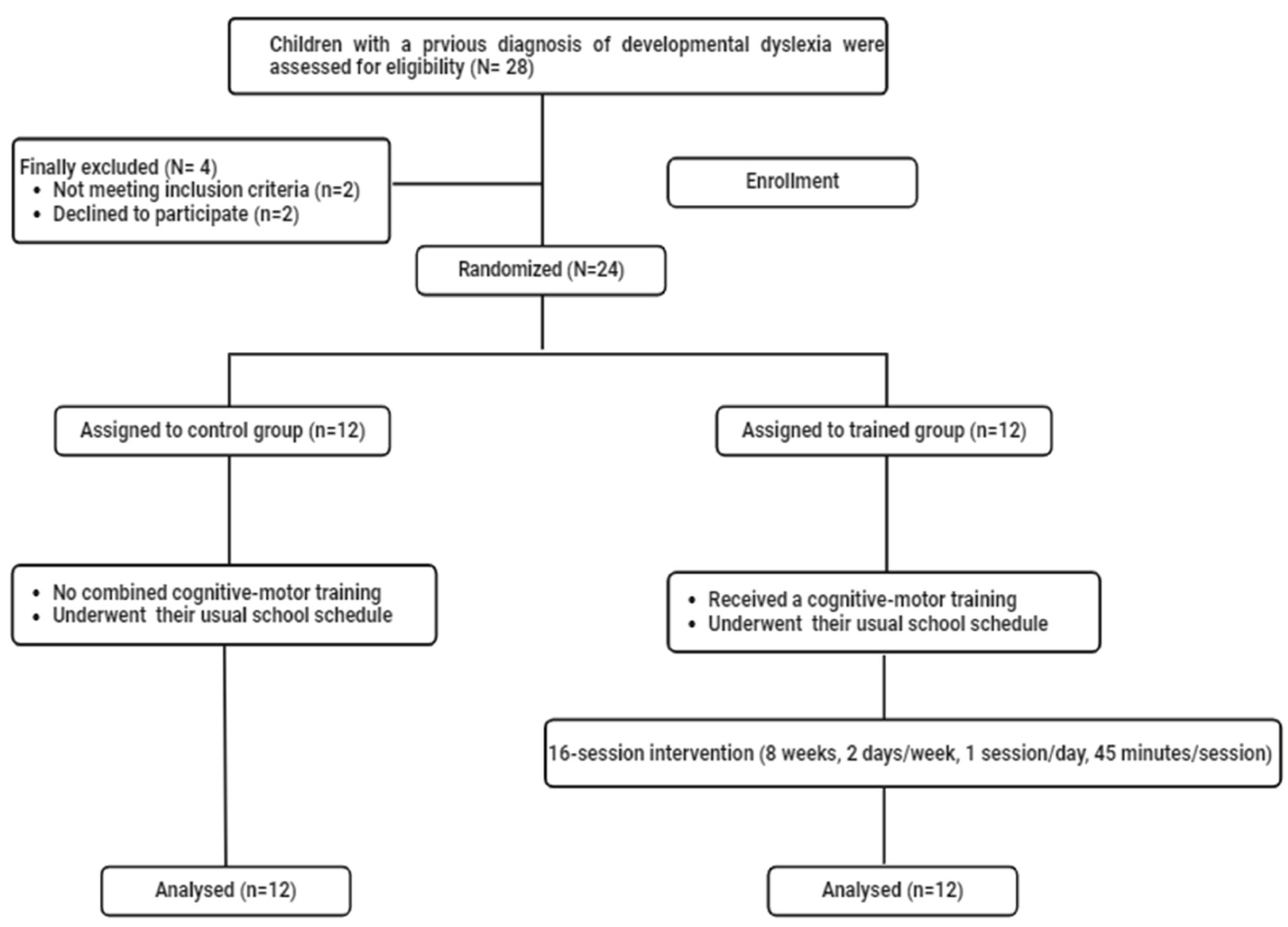

2.1. Sample Size and Participants

2.2. Cognitive evaluation

2.2.1. Reading Test

2.2.2. Writing Test

2.2.3. Combined Cognitive and Motor training program

2.3. Motor evaluation

2.3.1. Visuospatial Orientation Test

2.3.2. Upper Limb Coordination Test

2.4. Experimental Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cognitive abilities

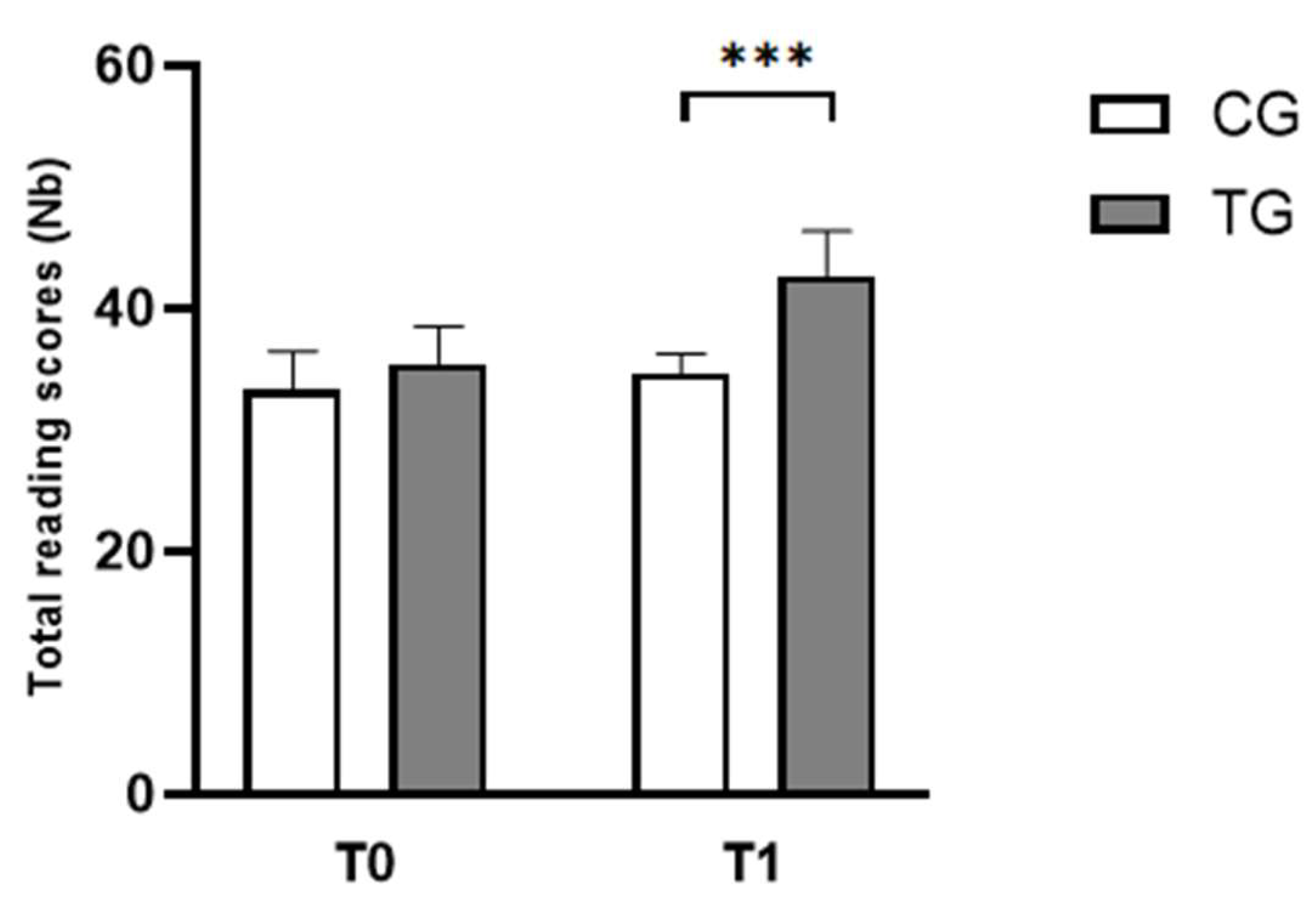

3.1.1. Reading Test

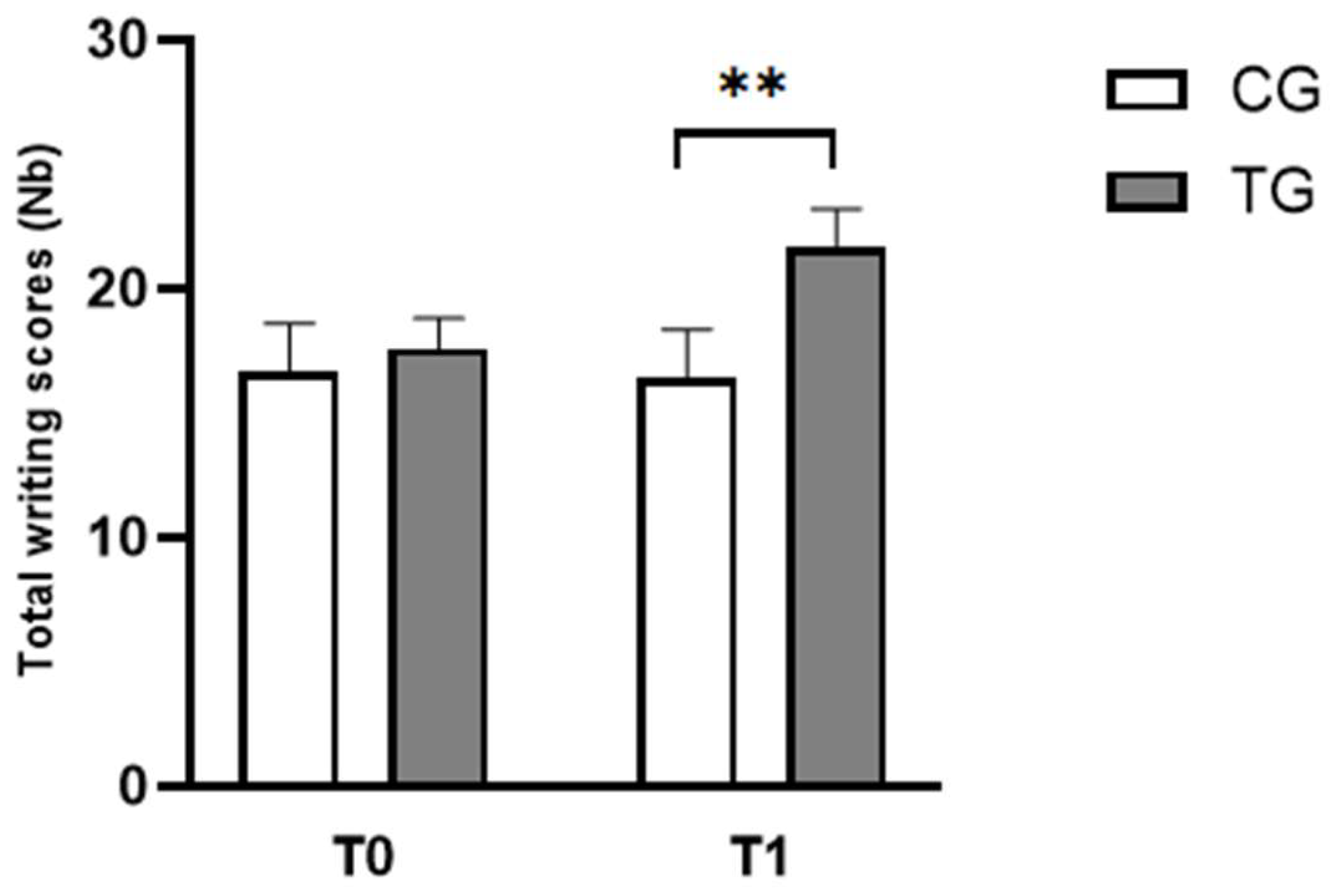

3.1.2. Writing Test

3.2. Motor abilities

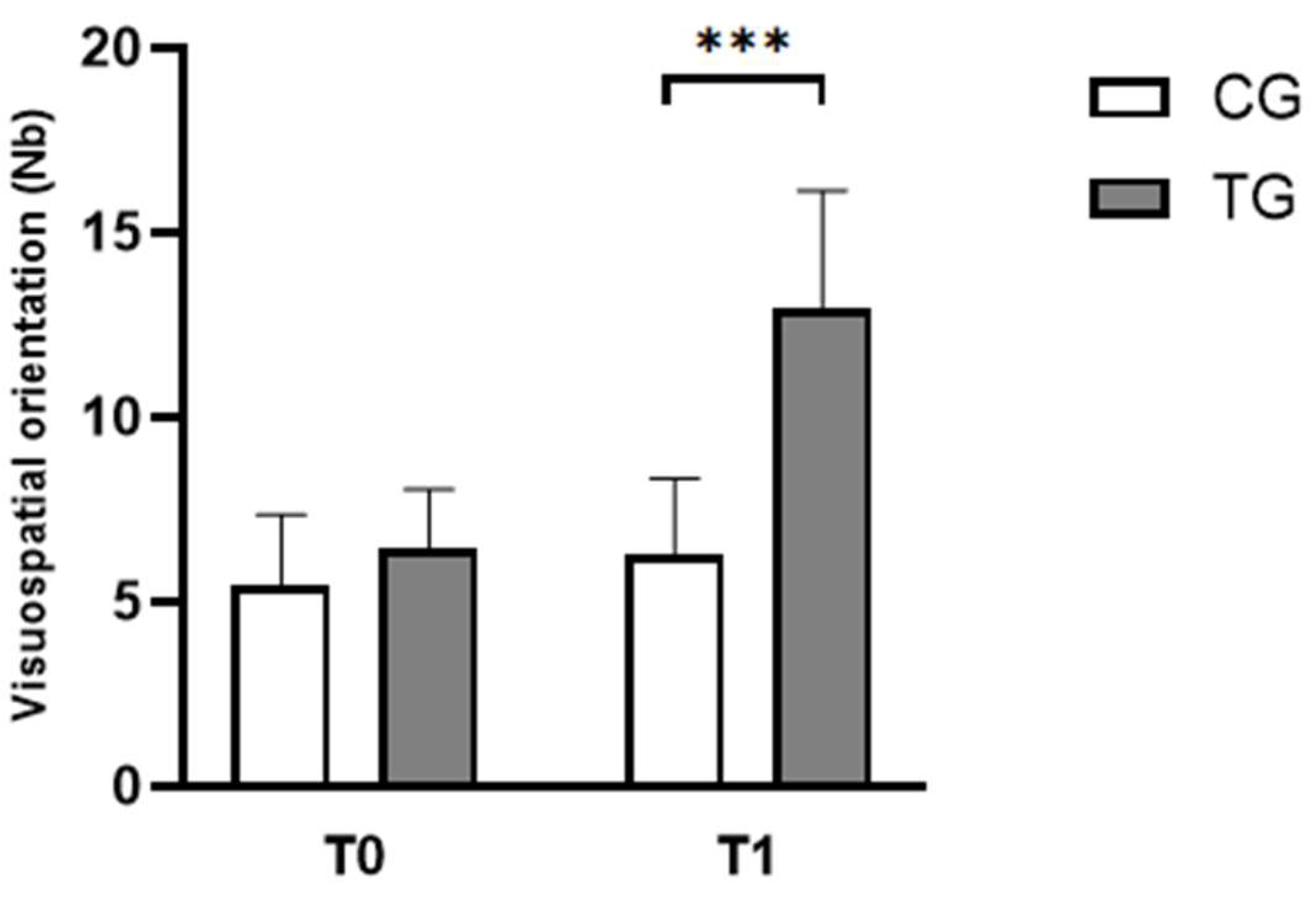

3.2.1. Visuospatial Orientation Test

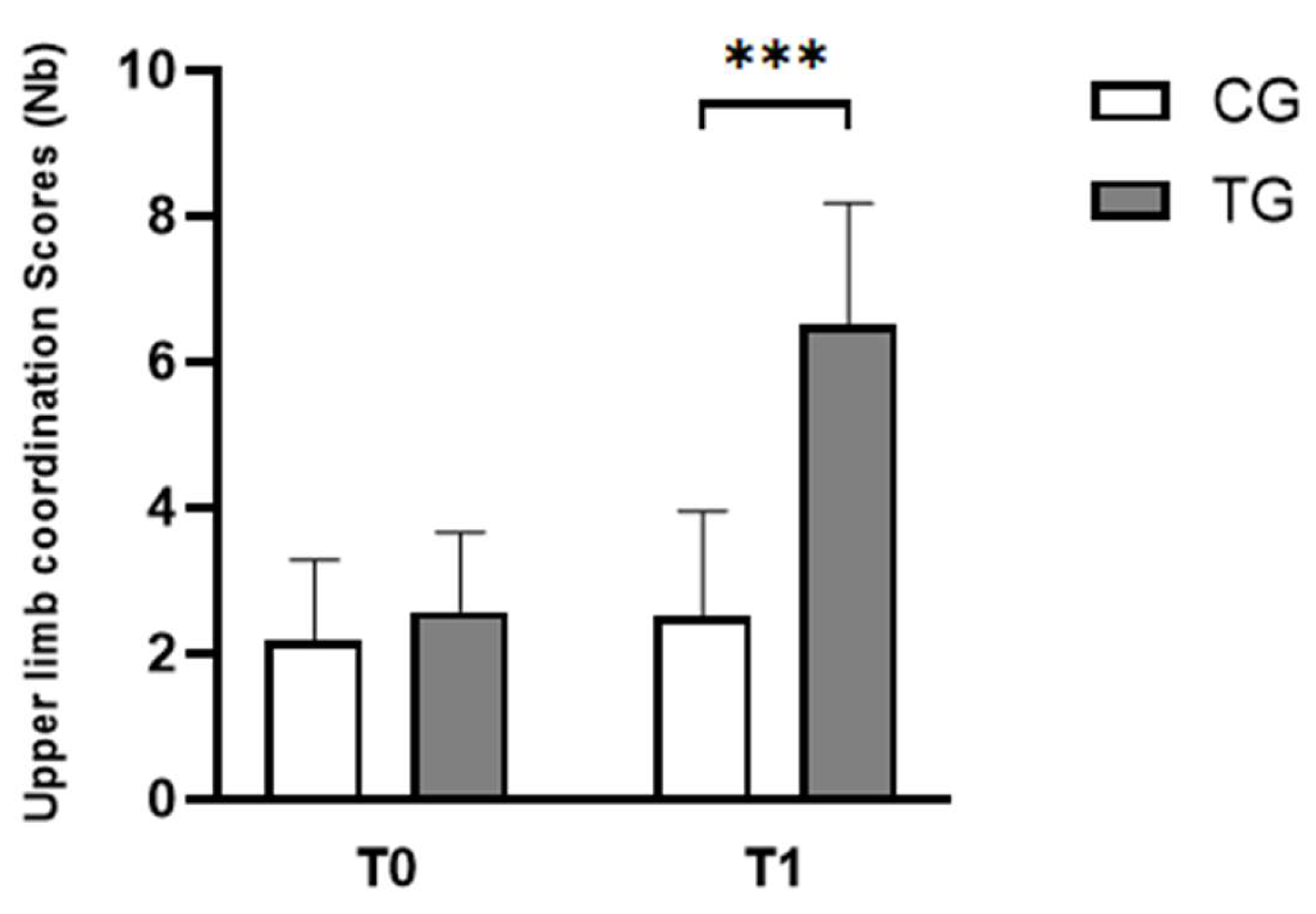

3.2.2. Upper Limb Coordination Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognitive Performances

4.2. Motor Performances

4.3. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DD | Developmental dyslexia |

| ACE | America's Children and the Environment |

| WISC-IV | Wechsler intelligence scale for children, fourth edition |

| BALE | Batterie Analytique du Langage Ecrit |

| ODÉDYS 2 | Outil de DÉpistage des DYSlexies Version 2 |

| JLOT | Judgment of Line Orientation Test |

| BOT-2 SF | Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition, Short Form |

| ELFE | Évaluation de la Lecture en FluencE |

| VWM | Verbal Working Memory |

| VWM-B | Verbal Working Memory Balance |

References

- Gu, C.; Bi, H.-Y. Auditory Processing Deficit in Individuals with Dyslexia: A Meta-Analysis of Mismatch Negativity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2020, 116, 396–405. [CrossRef]

- Ashburn, S. M.; Flowers, D. L.; Napoliello, E. M.; Eden, G. F. Cerebellar Function in Children with and without Dyslexia during Single Word Processing. Human brain mapping 2020, 41 (1), 120–138.

- US EPA, O. Key Findings of America’s Children and the Environment. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/americaschildrenenvironment/key-findings-americas-children-and-environment (accessed 2025-01-28).

- Bishop, D. V. M. The Interface between Genetics and Psychology: Lessons from Developmental Dyslexia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 282 (1806), 20143139. [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.; Shankweiler, D.; Mann, V. Speech Perception and Memory Coding in Relation to Reading Ability. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 1983, 35 (2), 345–367. [CrossRef]

- Bruck, M. Persistence of Dyslexics’ Phonological Deficits. Developmental Psychology - DEVELOP PSYCHOL 1992, 28, 874–886. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.874.

- Snowling, M. J. Phonological Processing and Developmental Dyslexia. Journal of Research in Reading 1995, 18 (2), 132–138.

- Stein, J. What Is Developmental Dyslexia? Brain Sciences 2018, 8 (2), 26. [CrossRef]

- Hampson, M.; Tokoglu, F.; Sun, Z.; Schafer, R. J.; Skudlarski, P.; Gore, J. C.; Constable, R. T. Connectivity–Behavior Analysis Reveals That Functional Connectivity between Left BA39 and Broca’s Area Varies with Reading Ability. NeuroImage 2006, 31 (2), 513–519. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Hoeft, F.; Zhang, L.; Shu, H. Neuroanatomical Anomalies of Dyslexia: Disambiguating the Effects of Disorder, Performance, and Maturation. Neuropsychologia 2016, 81, 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, M.; Demetre, J.; Hamill, S.; Robson, K.; Shepherd, H.; Cody, G. Executive Functioning in Adults and Children with Developmental Dyslexia. Neuropsychologia 2002, 40 (12), 2144–2155. [CrossRef]

- Facoetti, A.; Lorusso, M. L.; Paganoni, P.; Cattaneo, C.; Galli, R.; Mascetti, G. G. The Time Course of Attentional Focusing in Dyslexic and Normally Reading Children. Brain and Cognition 2003, 53 (2), 181–184. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, R. I.; Fawcett, A. J. Automaticity: A New Framework for Dyslexia Research? Cognition 1990, 35 (2), 159–182. [CrossRef]

- Stein, J. F.; Riddell, P. M.; Fowler, S. Disordered Vergence Control in Dyslexic Children. Br J Ophthalmol 1988, 72 (3), 162–166. [CrossRef]

- Tallal, P. Auditory Temporal Perception, Phonics, and Reading Disabilities in Children. Brain and Language 1980, 9 (2), 182–198. [CrossRef]

- Le Floch, A.; Ropars, G. Left-Right Asymmetry of the Maxwell Spot Centroids in Adults without and with Dyslexia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 284 (1865), 20171380. [CrossRef]

- Blythe, H.; Kirkby, J.; Liversedge, S. Comments on: “What Is Developmental Dyslexia?” Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 26. The Relationship between Eye Movements and Reading Difficulties. Brain Sciences 2018, 8 (6), 100. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, R. I.; Fawcett, A. J.; Dean, P. Developmental Dyslexia: The Cerebellar Deficit Hypothesis. Trends in Neurosciences 2001, 24 (9), 508–511. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, R. I.; Fawcett, A. J. Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, Procedural Learning and the Cerebellum. Cortex 2011, 47 (1), 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Hebert, M.; Kearns, D. M.; Hayes, J. B.; Bazis, P.; Cooper, S. Why Children With Dyslexia Struggle With Writing and How to Help Them. LSHSS 2018, 49 (4), 843–863. [CrossRef]

- Berninger, V. W.; Nielsen, K. H.; Abbott, R. D.; Wijsman, E.; Raskind, W. Writing Problems in Developmental Dyslexia: Under-Recognized and Under-Treated,. J Sch Psychol 2008, 46 (1), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, C.; Afonso, O.; Cuetos, F.; Suárez-Coalla, P. Handwriting Production in Spanish Children with Dyslexia: Spelling or Motor Difficulties? Reading & Writing 2021, 34 (3), 565–593.

- Iversen, S.; Berg, K.; Ellertsen, B.; Tønnessen, F.-E. Motor Coordination Difficulties in a Municipality Group and in a Clinical Sample of Poor Readers. Dyslexia 2005, 11 (3), 217–231. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. J. Identifying and Teaching Children and Young People with Dyslexia and Literacy Difficulties: An Independent Report from Sir Jim Rose to the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families; Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2009.

- Barela, J. A.; Dias, J. L.; Godoi, D.; Viana, A. R.; De Freitas, P. B. Postural Control and Automaticity in Dyslexic Children: The Relationship between Visual Information and Body Sway. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2011, 32 (5), 1814–1821. [CrossRef]

- Goulème, N.; Gérard, C.-L.; Bucci, M. P. The Effect of Training on Postural Control in Dyslexic Children. PLoS ONE 2015, 10 (7), e0130196. [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, A.; Khalid, S. The Association of Abnormal Cerebellar Function in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder and Reading Difficulties. Dyslexia 2002, 8 (4), 234–248. [CrossRef]

- Stoodley, C. J.; Fawcett, A. J.; Nicolson, R. I.; Stein, J. F. Impaired Balancing Ability in Dyslexic Children. Exp Brain Res 2005, 167 (3), 370–380. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.; Quercia, P.; Michel, C.; Pozzo, T.; Bonnetblanc, F. Cognitive Demands Impair Postural Control in Developmental Dyslexia: A Negative Effect That Can Be Compensated. Neuroscience Letters 2009, 462 (2), 125–129. [CrossRef]

- Yap, R. L.; Leij, A. van der. Testing the Automatization Deficit Hypothesis of Dyslexia Via a Dual-Task Paradigm. J Learn Disabil 1994, 27 (10), 660–665. [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M. Neuroanatomical Markers for Dyslexia: A Review of Dyslexia Structural Imaging Studies. Neuroscientist 2004, 10 (4), 362–371. [CrossRef]

- Kibby, M. Y.; Fancher, J. B.; Markanen, R.; Hynd, G. W. A Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis of the Cerebellar Deficit Hypothesis of Dyslexia. J Child Neurol 2008, 23 (4), 368–380. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, C.; Kuldau, J.; Maron, L.; Ricciuti, N.; Mahoney, B.; Bengtson, M.; Debose, C. Identical Neural Risk Factors Predict Cognitive Deficit in Dyslexia and Schizophrenia. Neuropsychology 2008, 22, 147–158. [CrossRef]

- Rae, C.; Harasty, J. A.; Dzendrowskyj, T. E.; Talcott, J. B.; Simpson, J. M.; Blamire, A. M.; Dixon, R. M.; Lee, M. A.; Thompson, C. H.; Styles, P.; Richardson, A. J.; Stein, J. F. Cerebellar Morphology in Developmental Dyslexia. Neuropsychologia 2002, 40 (8), 1285–1292 . [CrossRef]

- Boets, B.; de Beeck, H. O.; Vandermosten, M.; Scott, S. K.; Gillebert, C. R.; Mantini, D.; Bulthé, J.; Sunaert, S.; Wouters, J.; Ghesquière, P. Intact but Less Accessible Phonetic Representations in Adults with Dyslexia. Science 2013, 342 (6163), 1251–1254. [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Lardy, C.; Desiles, T.; Commeiras, C.; Chobert, J.; Besson, M. Music and Dyslexia: A New Musical Training Method to Improve Reading and Related Disorders. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Caldani, S.; Gerard, C.-L.; Peyre, H.; Bucci, M. P. Visual Attentional Training Improves Reading Capabilities in Children with Dyslexia: An Eye Tracker Study During a Reading Task. Brain Sciences 2020, 10 (8), 558. [CrossRef]

- Caldani, S.; Moiroud, L.; Miquel, C.; Peiffer, V.; Florian, A.; Bucci, M. P. Short Vestibular and Cognitive Training Improves Oral Reading Fluency in Children with Dyslexia. Brain Sciences 2021, 11 (11), 1440. [CrossRef]

- Bonacina, S.; Cancer, A.; Lanzi, P. L.; Lorusso, M. L.; Antonietti, A. Improving Reading Skills in Students with Dyslexia: The Efficacy of a Sublexical Training with Rhythmic Background. Front Psychol 2015, 6, 1510. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Fawcett, A. J. Cognitive-Motor Training Improves Reading-Related Executive Functions: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study in Dyslexia. Brain Sciences 2024, 14 (2), 127. [CrossRef]

- Serdar, C. C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; Serdar, M. A. Sample Size, Power and Effect Size Revisited: Simplified and Practical Approaches in Pre-Clinical, Clinical and Laboratory Studies. Biochem. med. (Online) 2021, 31 (1), 27–53. [CrossRef]

- Crocq, M.-A.; Guelfi, J.-D. DSM-5: manuel diagnostique et statistique des troubles mentaux, 5e éd.; Elsevier Masson: Issy-les-Moulineaux, 2015.

- Wechsler, D.; Kodama, H. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children; Psychological corporation New York, 1949; Vol. 1.

- Jacquier-Roux, M.; Lequette, C.; Pouget, G.; Valdois, S.; Zorman, M. BALE: Batterie Analytique Du Langage Écrit; Groupe Cogni-Sciences, Laboratoire de Psychologie et NeuroCognition, 2010. Available online: https://www1.ac-grenoble.fr/article/cognisciences-121593.

- Jacquier-Roux, M.; Valdois, S.; Zorman, M. ODÉDYS 2 : Outil de Dépistage des DYSlexies, Version 2, Groupe Cogni-Sciences, Laboratoire de Psychologie et NeuroCognition, 2005. Available online: https://www1.ac-grenoble.fr/article/cognisciences-121593.

- Benton, A. L.; Varney, N. R.; Hamsher, K. D. Visuospatial Judgment. A Clinical Test. Arch Neurol 1978, 35 (6), 364–367. [CrossRef]

- Calamia, M.; Markon, K.; Denburg, N. L.; Tranel, D. Developing a Short Form of Benton’s Judgment of Line Orientation Test: An Item Response Theory Approach. Clin Neuropsychol 2011, 25 (4), 670–684. [CrossRef]

- Bruininks, R. H.; Bruininks, B. D. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition, 2005.

- Radanović, D.; Đorđević, D.; Stanković, M.; Pekas, D.; Bogataj, Š.; Trajkovic, N. Test of Motor Proficiency Second Edition (BOT-2) Short Form: A Systematic Review of Studies Conducted in Healthy Children. Children 2021, 8 (9), 787. [CrossRef]

- Clark-Carter, D. Doing Quantitative Psychological Research: From Design to Report. 1997.

- Hopkins, W. G. A Scale of Magnitudes for Effect Statistics. A new view of statistics 2002, 502 (411), 321.

- Mersin, Y.; Çebi, M. An In-Depth Examination of Visuospatial Functions in a Group of Turkish Children with Dyslexia. The Journal of Neurobehavioral Sciences 2021, 8 (2), 114–118. [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, R. H. An Assessment of the Motor Performance Skills of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Gulf Region. Brain Sci 2020, 10 (9), 607 . [CrossRef]

- Cognisciences. Site de l’académie de Grenoble. Available online: https://www1.ac-grenoble.fr/article/cognisciences-121593.

- Moroso, A.; Ruet, A.; Lamargue-Hamel, D.; Munsch, F.; Deloire, M.; Coupé, P.; Ouallet, J.-C.; Planche, V.; Moscufo, N.; Meier, D. S.; Tourdias, T.; Guttmann, C. R. G.; Dousset, V.; Brochet, B. Posterior Lobules of the Cerebellum and Information Processing Speed at Various Stages of Multiple Sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017, 88 (2), 146–151. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Behzadipour, S.; Fawcett, A. J.; Joghataei, M. T. Verbal Working Memory-Balance Program Training Alters the Left Fusiform Gyrus Resting-State Functional Connectivity: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study on Children with Dyslexia. Dyslexia 2023, 29 (3), 264–285. [CrossRef]

- Giovagnoli, G.; Vicari, S.; Tomassetti, S.; Menghini, D. The Role of Visual-Spatial Abilities in Dyslexia: Age Differences in Children’s Reading? Front. Psychol. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bourke, L.; Davies, S. J.; Sumner, E.; Green, C. Individual Differences in the Development of Early Writing Skills: Testing the Unique Contribution of Visuo-Spatial Working Memory. Read Writ 2014, 27 (2), 315–335. [CrossRef]

- Olive, T.; Passerault, J.-M. The Visuospatial Dimension of Writing. Written Communication 2012, 29, 326–344. [CrossRef]

- Rival, C.; Olivier, I.; Ceyte, H.; Bard, C. Age-Related Differences in the Visual Processes Implied in Perception and Action: Distance and Location Parameters. Journal of experimental child psychology 2004, 87, 107–124. [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, M.; Czaplewska, E.; Wysocka, A. Visuospatial Deficits of Dyslexic Children. Med Sci Monit 2011, 17 (4), CR216–CR221. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanowicz, M.; Adryjanek, A.; Rożyńska, M. Uczeń z Dysleksją w Domu: Poradnik Nie Tylko Dla Rodziców; Wydawnictwo Pedagogiczne Operon, 2007.

- Bogdanowicz, M.; Kalka, D.; Krzykowski, G. Ryzyko Dysleksji: Problem i Diagnozowanie; Wydawnictwo. Harmonia, 2003.

- Przekoracka-Krawczyk, A.; Brenk-Krakowska, A.; Nawrot, P.; Rusiak, P.; Naskrecki, R. Unstable Binocular Fixation Affects Reaction Times But Not Implicit Motor Learning in Dyslexia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58 (14), 6470–6480. [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Z. A.; Abdel-Aty, S. A.-R.; Elmeniawy, G. H.; Mahgoub, E. A.-M. Defects of Motor Performance in Children with Different Types of Specific Learning Disability. Drug Invention Today 2020, 14 (2).

- Stošljević, M.; Adamović, M. Hand-Eye Coordination Ability in Students with Dyslexia. 2012.

- Macdonald, K.; Milne, N.; Orr, R.; Pope, R. Associations between Motor Proficiency and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Reading in Year 1 School Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Pediatrics 2020, 20 (1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, K.; Milne, N.; Orr, R.; Pope, R. Relationships between Motor Proficiency and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Reading in School-Aged Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. IJERPH 2018, 15 (8), 1603. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Gu, X. The Role of Executive Function in Linking Fundamental Motor Skills and Reading Proficiency in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Kindergarteners. Learning and Individual Differences 2018, 61, 250–255. [CrossRef]

- Aadland, K. N.; Ommundsen, Y.; Aadland, E.; Brønnick, K. S.; Lervåg, A.; Resaland, G. K.; Moe, V. F. Executive Functions Do Not Mediate Prospective Relations between Indices of Physical Activity and Academic Performance: The Active Smarter Kids (ASK) Study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, T.; Hillman, C.; Kalaja, S.; Liukkonen, J. The Associations among Fundamental Movement Skills, Self-Reported Physical Activity and Academic Performance during Junior High School in Finland. Journal of Sports Sciences 2015, 33 (16), 1719–1729. [CrossRef]

- Nilukshika, K. V. K.; Nanayakkarawasam, P. P.; Wickramasinghe, V. P. The Effects of Upper Limb Exercises on Hand Writing Speed. Indian Journal of Physiotherapy & Occupational Therapy 2012, 6 (3).

| Clinical characteristics | Mean (± SD) | |

| CG (n=12) | TG (n=12) | |

| Girls / Boys (Nb) | 6 / 6 | 6 / 6 |

| Chronological age (years) | 9.25 ± 0.45 | 9.42 ± 0.51 |

| Weight (kg) | 30.08 ± 1.65 | 30.33 ± 1.63 |

| Height (cm) | 130.67 ± 2.02 | 130.58 ± 1.73 |

| IQ (WISC-IV) | 103.92 ± 5.20 | 104.42 ± 4.19 |

| Activity Stage | Performed Exercises |

| Warm-Up (10 minutes) | Arm circles (forward/backward) |

| Cross-body Arm swings | |

| Shoulder rolls | |

| Upper limb coordination (15 minutes) | 1. Ball Toss and Call-Out (5 minutes) |

| Toss a ball against a wall or with a partner, catching it with one or both hands. | |

| 2. Ball Passing (5 minutes) | |

| Pass a ball from one hand to the other, while calling out confusions' letters (e.g., "b / d" or "m/n" or "p/q"). | |

| 3. Hand-ball Juggling (5 minutes) | |

| Hold a tennis ball in each hand and throw them in the air alternately, catching them with the same hand. Gradually increase the height and speed. | |

| Visuospatial Orientation (15 minutes) | 1. Direction Changes (5 minutes) |

| Change direction through different orientations (e.g., "left" or "right" or "forward" or "backward") according to verbal or visual instructions. | |

| 2. Draw and Follow (5 minutes) | |

| Draw a line representation of confusions' letters (e.g., "b / d" or "m/n" or "p/q"). Follow the representation's direction to reach the destination. | |

| Ball dribbling following a path drawn that represented confusion among letters (e.g., "b / d" or "m/n" or "p/q"). | |

| 3. Mirror Exercises (5 minutes) | |

| A partner calls out or demonstrates movements (e.g., “step right, turn left”) while you mirror them. | |

| Cool-Down (5 minutes) | Stretch arms overhead and across the chest. |

| Deep breathing with arm raises. |

| Title 2 | Title 3 | |

| Reading scores (Nb) | 33.96 ± 2,60 | 55.19 ± 4.42 44 |

| Writing scores (Nb) | 16,54 ± 1,89 | 26.28 ± 3.65 45 |

| Visuospatial orientation scores (Nb) | 5.92 ± 1.82 | 21.60 ± 2.89 52 |

| Upper limb coordination scores (Nb) | 2.38 ± 1.10 | 10.20 ± 1.73 53 |

| Cognitive parameters | Groups | Means values (±SD) | |

| T0 | T1 | ||

| Reading scores (Nb) | CG | 33.25 ± 3.22 | 35.42 ± 3.09 |

| TG | 34.67 ± 1.61 | 42.67 ± 3.70 *** | |

| Writing scores (Nb) | CG | 16.67 ± 1.92 | 17.58 ± 1.24 |

| TG | 16.42 ± 1.93 | 21.67 ± 1.44** | |

| Motor parameters | Groups | Means values (±SD) | |

| T0 | T1 | ||

| Visuospatial orientation scores (Nb) | CG | 5.42 ± 1.93 | 6.25 ± 2.09 |

| TG | 6.42 ± 1.62 | 12.92 ± 3.23*** | |

| Upper limb coordination scores (Nb) | CG | 2.17 ± 1.11 | 2.50 ± 1.45 |

| TG | 2.58 ± 1.08 | 6.50 ± 1.68 *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).