Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Polyphenol Composition of the Raspberry Fruit Extract and Anthocyanin and Non-Anthocyanin Fractions

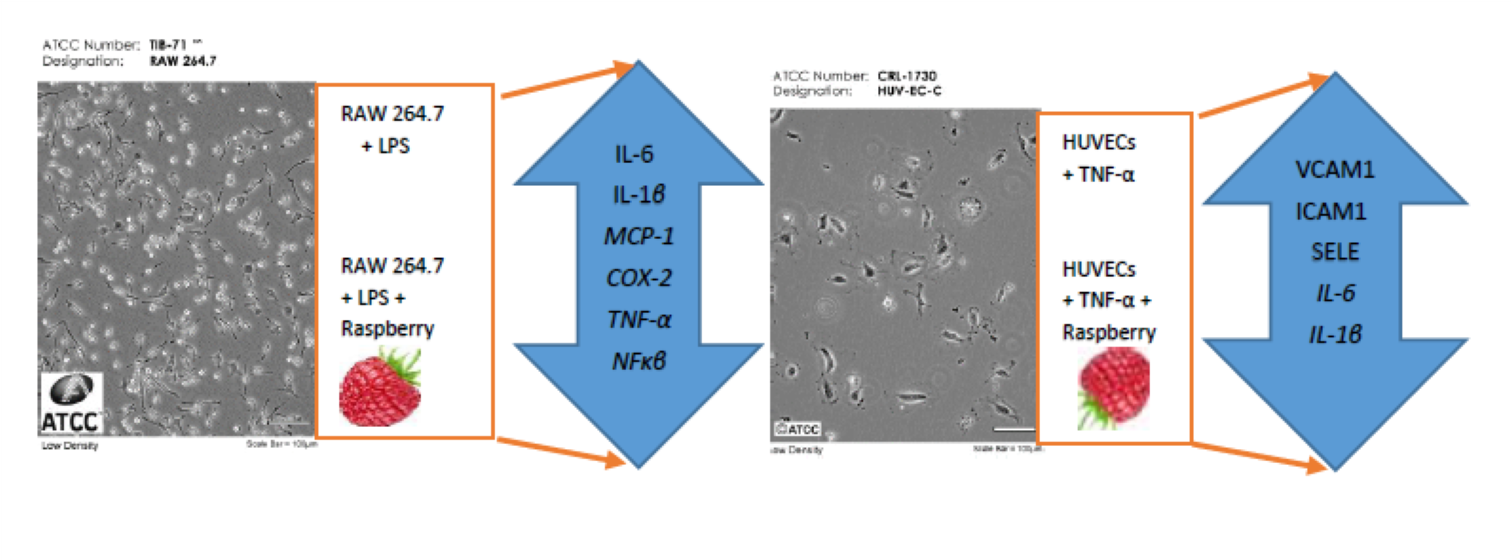

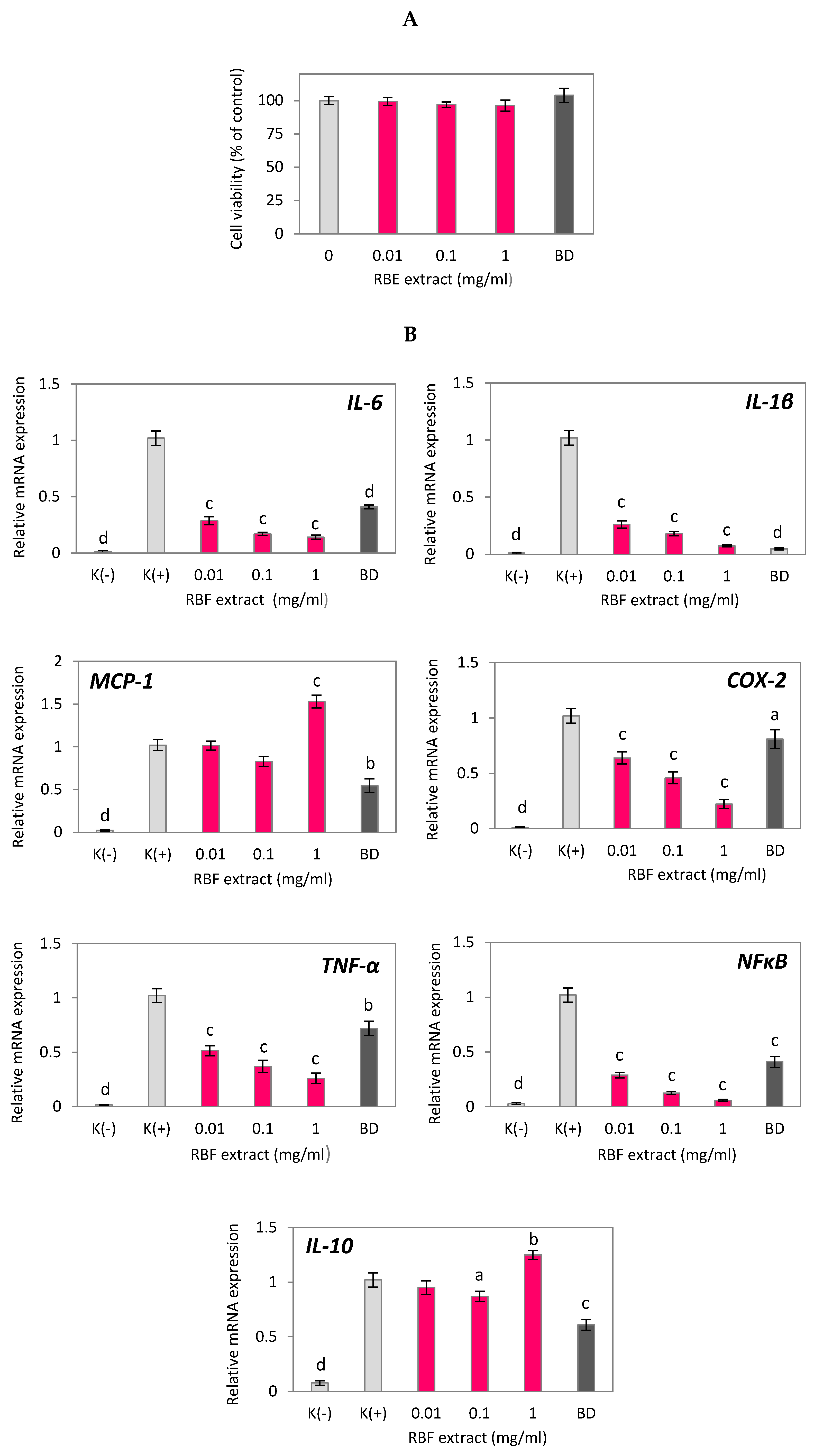

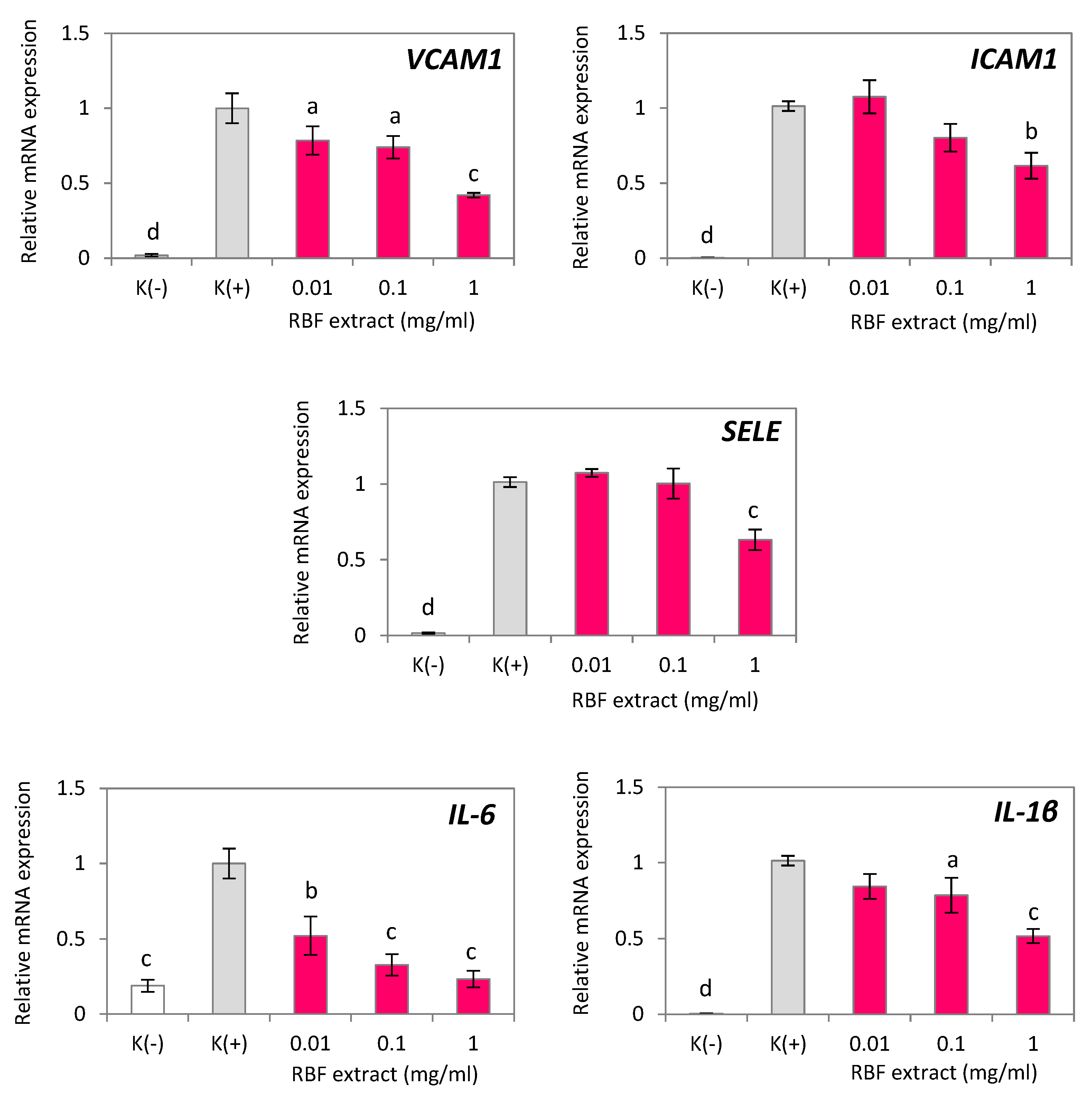

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Raspberry Fruit Extract

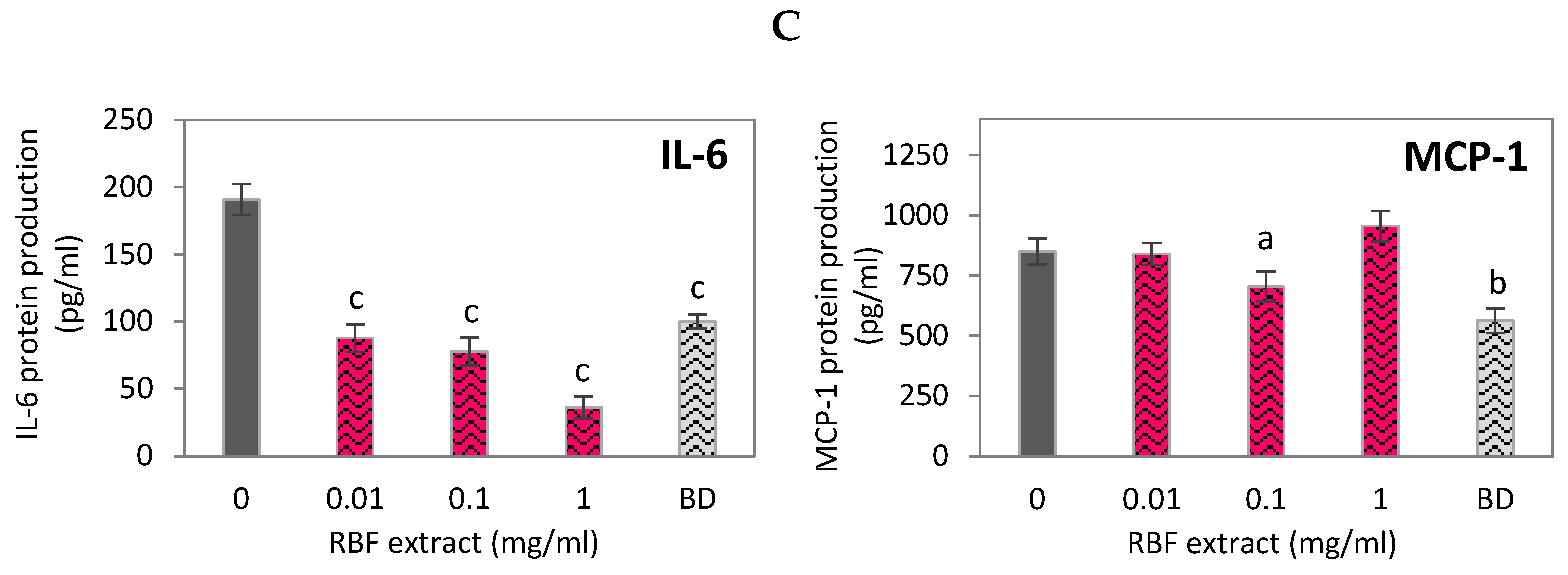

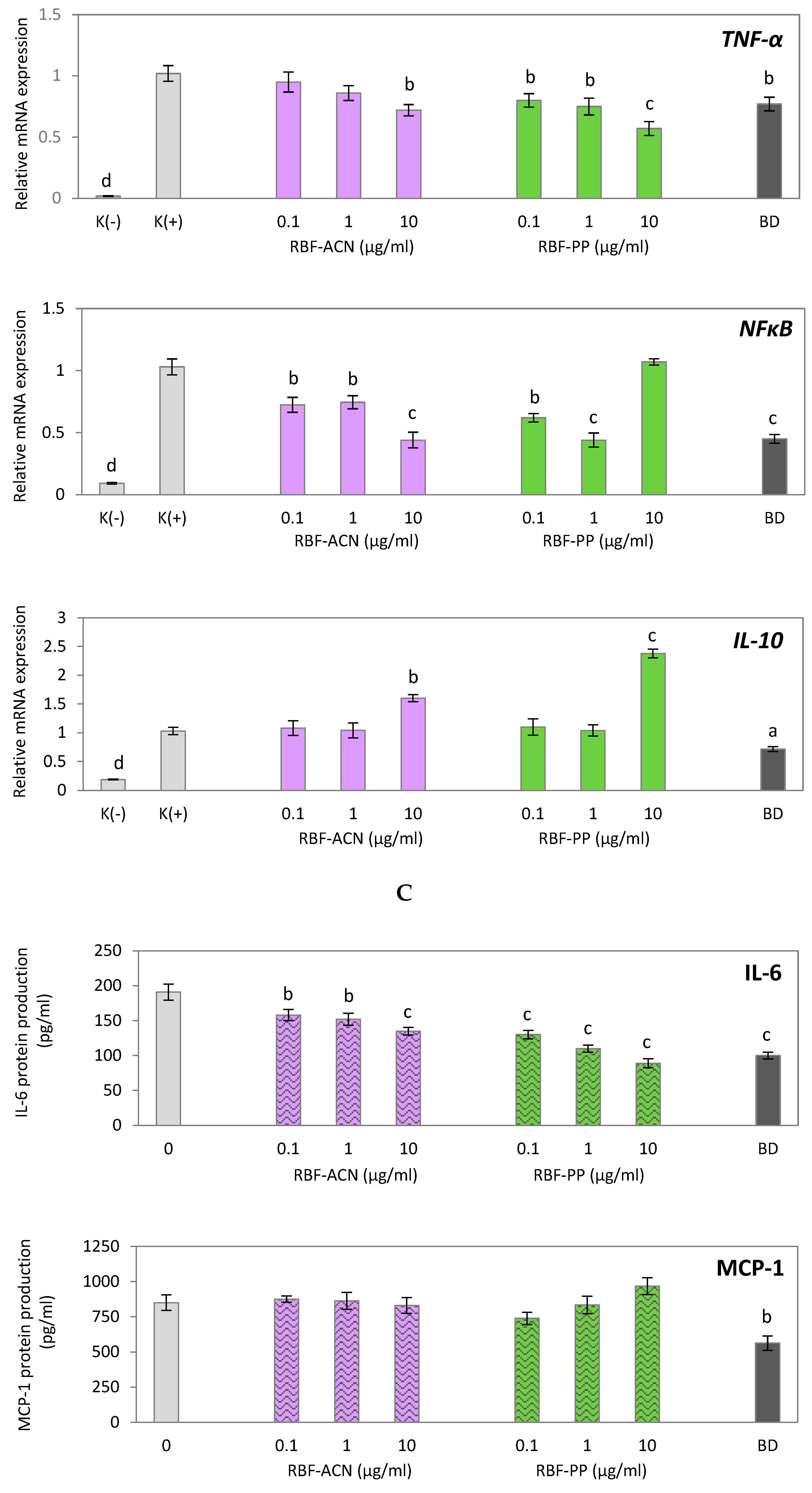

2.3. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Anthocyanin and Non-Anthocyanin Polyphenol Fractions of Raspberry Fruit Extract

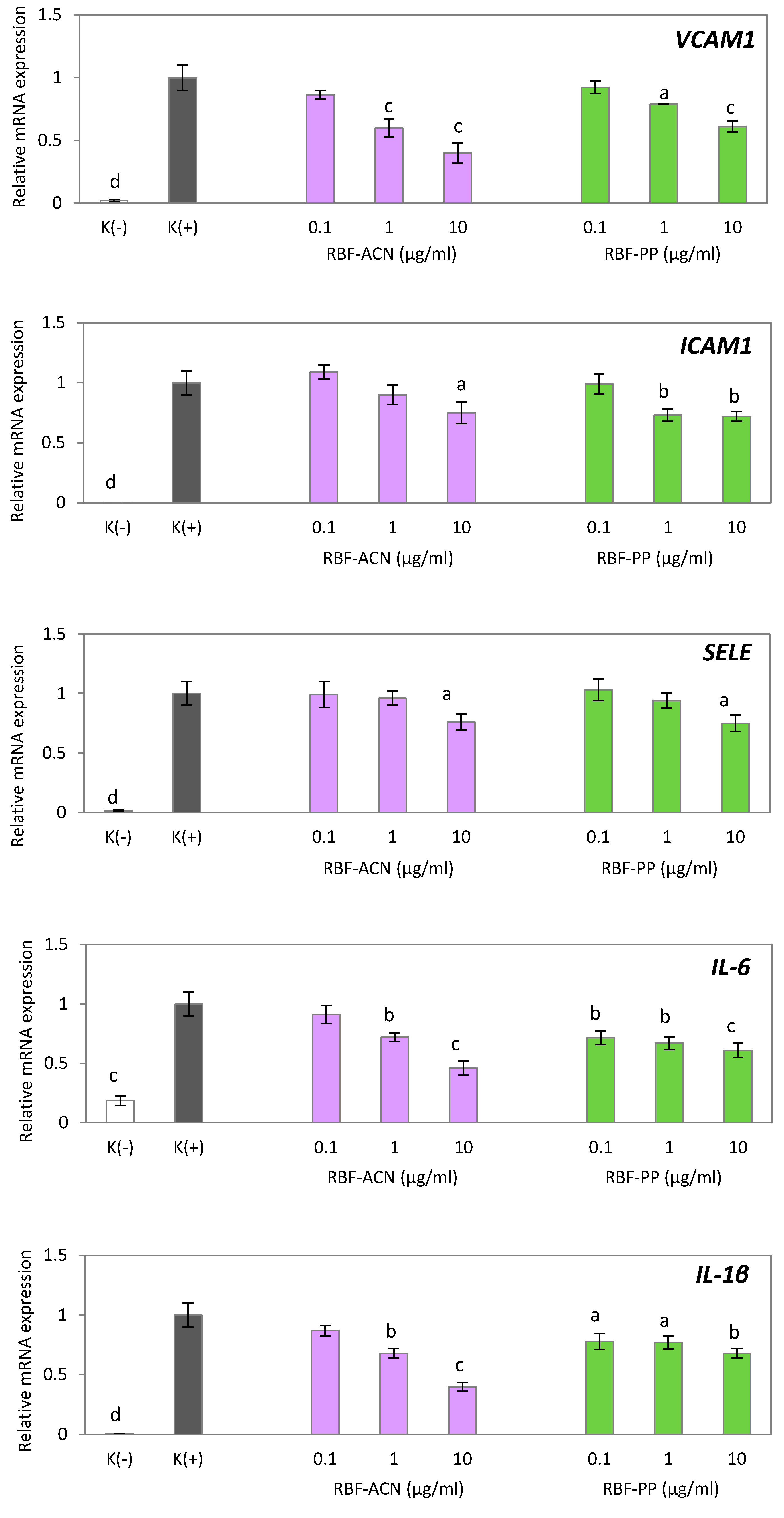

2.4. Potential of Raspberry Fruit Extract, Anthocyanin Fraction, and Non-Anthocyanin Polyphenol Fraction in Counteracting Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Preparation of Raspberry Fruit Extract and Anthocyanin and Non-Anthocyanin Polyphenol Fractions

4.3. Polyphenol Identification and Quantification

4.4. Cell Cultures and Anti-Inflammatory Experiment Procedure

4.5. Cell Viability Assay

4.6. RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.7. Determination of IL-6 and MCP-1 Production

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Susser, L.I.; Rayner, K.J. Through the layers: how macrophages drive atherosclerosis across the vessel wall. J. Clin. Invest. 2022, 132, e157011. [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.J.; Sheedy, F.J.; Fisher, E.A. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 709-721. [CrossRef]

- Auffray, C.; Fogg, D.; Garfa, M.; Elain, G.; Join-Lambert, O., Kayal, S.; Sarnacki, S.; Cumano, A.; Lauvau, G.; Geissmann, F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007, 317, 666-670. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 762–774.

- Rahman, K.; Vengrenyuk, Y.; Ramsey, S.A.; Vila, N.R.; Girgis, M.; Liu, J.; Gusarova, V.; Gromada, J.; Weinstock, A.; Moore, K.J.; Loke, P.; Fisher, E.A. Inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes and their conversion to M2 macrophages drive atherosclerosis regression. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 2904-2915.

- Libby, P.; Everett, B.M. Novel anti-atherosclerotic therapies. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 538–545.

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; An-ker, S.D.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Cornel, J.H.; Pais, P.; Pella, D.; Genest, J.; Cifkova, R.; Lorenzatti, A.; Forster, T.; Kobalava, Z.; Vida-Simiti, L.; Flather, M.; Shimokawa, H.; Ogawa, H.; Dellborg, M.; Rossi, P.R.F.; Troquay, R.P.T.; Libby, P.; Glynn, R.J.; CAN-TOS Trial Group. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119-1131.

- Martínez, G.J.; Celermajer, D.S.; Patel, S. The NLRP3 inflammasome and the emerging role of colchicine to inhibit atherosclerosis-associated inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 2017, 269, 262–271.

- Ezzati, M.; Riboli, E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for non-communicable diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 954-964.

- Cassidy, A. Berry anthocyanin intake and cardiovascular health. Mol. Aspects. Med. 2018, 61, 76-82. [CrossRef]

- Burton-Freeman, B.M.; Sandhu, A.K.; Edirisinghe, I. Red Raspberries and Their Bioactive Polyphenols: Cardiometabolic and Neuronal Health Links. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 44-65. [CrossRef]

- Suh, J. H.; Romain, C.; González-Barrio, R.; Cristol, J. P.; Teissèdre, P. L.; Crozier, A.; Rouanet, J. M. Raspberry juice consumption, oxidative stress and reduction of atherosclerosis risk factors in hypercholesterolemic golden Syrian hamsters. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 400–405.

- Jia, H.; Liu, J.W.; Ufur, H.; He, G.S.; Liqian, H.; Chen, P. (2011). The antihypertensive effect of ethyl acetate extract from red raspberry fruit in hypertensive rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2011, 7, 19–24.

- Kowalska, K.; Olejnik, A.; Zielińska-Wasielica, J.; Olkowicz, M. Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) fruit extract decreases oxidation markers, improves lipid metabolism and reduces adipose tissue inflammation in hypertrophied 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Func. Food. 2019, 62, 103568.

- Jean-Gilles, D.; Li, L.; Ma, H.; Yuan, T.; Chichester, C.O. 3rd; Seeram, N.P. Anti-inflammatory effects of polyphenolic-enriched red raspberry extract in an antigen-induced arthritis rat model. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2012, 60, 5755-5762.

- Kowalska, K.; Olejnik, A.; Rychlik, J.; Grajek, W. Cranberries (Oxycoccus quadripetalus) inhibit adipogenesis and lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Food Chem. 2014, 148, 246–252. [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, K.; Dembczyński, R.; Gołąbek, A.; Olkowicz, M.; Olejnik, A. ROS Modulating Effects of Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis idaea L.) Polyphenols on Obese Adipocyte Hypertrophy and Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 885. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Park, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Lee, S.; Yang, J.; Dellsperger, K.C.; Zhang, C. Role of TNF-alpha in vascular dysfunction. Clin. Sci. 2009, 116, 219–230.

- Speer, H.; D'Cunha, N.M.; Alexopoulos, N.I.; McKune, A.J.; Naumovski, N. Anthocyanins and Human Health-A Focus on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Disease. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 366. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, T.W;, Khalaf, F.K.; Soehnlen, S.; Hegde, P.; Storm, K.; Meenakshisundaram, C.; Dworkin, L.D.; Malhotra, D.; Haller, S.T.; Kennedy, D.J.; Dube, P. Dirty Jobs: Macrophages at the Heart of Cardiovascular Disease. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 1579. [CrossRef]

- Vendrame, S.; Klimis-Zacas, D. Anti-inflammatory effect of anthocyanins via modulation of nuclear factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 348-358. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z.; Yao, L.; Wu, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, K.; Zhou, X.; Gou, D. Anthocyanin-rich fractions from red raspberries attenuate inflammation in both RAW264.7 macrophages and a mouse model of colitis. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6234. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Kim, B.; Yang, Y.; Pham, T.X.; Park, Y.K.; Manatou, J.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K.; Lee, J.Y. Berry anthocyanins suppress the expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators in macrophages by inhibiting nuclear translocation of NF-κB independent of NRF2-mediated mechanism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 404-411.

- Zhang, Y.; Lian, F.; Zhu, Y.; Xia, M.; Wang, Q.; Ling, W.; Wang, X.D. Cyanidin-3-O-beta-glucoside inhibits LPS-induced expression of inflammatory mediators through decreasing IkappaBalpha phosphorylation in THP-1 cells. Inflamm. Res. 2010, 59, 723-730.

- Noratto, G.D.; Chew, B.P.; Atienza, L.M. Red raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) intake decreases oxidative stress in obese diabetic (db/db) mice. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 305-314. [CrossRef]

- Mykkanen, O.T.; Huotari, A.; Herzig, K.H.; Dunlop, T.W.; Mykkanen, H.; Kirjavainen, P.V. Wild blueberries (Vaccinium myrtillus) alleviate inflammation and hypertension associated with developing obesity in mice fed with a high-fat diet. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114790.

- Schell, J.; Betts, N.M.; Lyons, T.J.; Basu, A. Raspberries Improve Postprandial Glucose and Acute and Chronic Inflammation in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 165-174.

- Aboonabi, A.; Aboonabi A. Anthocyanins reduce inflammation and improve glucose and lipid metabolism associated with inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB activation and increasing PPAR-γ gene expression in metabolic syndrome subjects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 150, 30-39. [CrossRef]

- Moens, U.; Kostenko, S.; Sveinbjørnsson, B. The Role of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Activated Protein Kinases (MAP-KAPKs) in Inflammation. Genes (Basel). 2013, 4, 101-133. [CrossRef]

- Land Lail, H.; Feresin, R.G.; Hicks, D.; Stone, B.; Price, E.; Wanders, D. Berries as a Treatment for Obesity-Induced Inflammation: Evidence from Preclinical Models. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 334. [CrossRef]

- Farahi, L.; Sinha, S.K.; Lusis, A.J. Roles of Macrophages in Atherogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 785220. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ling, W.; Guo, H.; Song, F.; Ye, Q.; Zou, T.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y; Li, G.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z.; Yang, Y. Anti-inflammatory effect of purified dietary anthocyanin in adults with hypercholesterolemia: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 843–849. [CrossRef]

- Speciale, A.; Canali, R.; Chirafisi, J.; Saija, A.; Virgili, F.; Cimino, F. Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside protection against TNF-a-induced endothelial dysfunction: involvement of nuclear factor-ĸB signaling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12048–12054.

- Yang, F.; Suo, Y.; Chen, D.; Tong, L. Protection against vascular endothelial dysfunction by polyphenols in sea buckthorn berries in rats with hyperlipidemia. Biosci. Trends 2016, 10, 188–196.

- Basu, A.; Fu, D.X.; Wilkinson, M.; Simmons, B.; Wu, M.; Betts, N.M.; Du, M.; Lyons, T.J. Strawberries decrease atherosclerotic markers in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Res. 2010, 30, 462–469.

- Jeong, H.S.; Hong, S.J.; Lee, T.B.; Kwon, J.W.; Jeong, J.T.; Joo, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Ahn, C.M.; Yu, C.W.; Lim, D.S. Effects of black raspberry on lipid profiles and vascular endothelial function in patients with metabolic syndrome. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 1492-1498. [CrossRef]

| Peak No. |

RT (min) |

UV λ max (nm) | [M − H]- / / [M + H]+ (m/z) |

MS/MS (m/z) |

Tentative identification |

Concentration (mg/g)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBF | RBF-ACN | RBF-PP | ||||||

| RBF ANTHOCYANINS | ||||||||

| 1 2 3 4 |

15.77 16.44 17.18 18.20 |

280, 520 280, 520 280, 520 280, 520 |

611.1642 (+) 757.2220 (+) 449.1123 (+) 595.1734 (+) |

449.1078 287.0615 595.1663 287.0572 287.0589 287.0578 |

Cyanidin-3-O-sophoroside Cyanidin-3-O-glucosyl-rutinoside Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside |

3.07 ± 0.18 0.71 ± 0.05 1.41 ± 0.12 0.51 ± 0.04 |

520.02 ± 12.54 127.25 ± 6.23 235.26 ± 5.22 97.25 ± 3.41 |

28.29 ± 1.95 Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts |

| RBF FLAVANOLS | ||||||||

| 5 6 7 |

9.84 10.74 12.61 |

280 280 280 |

577.1355 (-) 289.1139 (-) 289.1142 (-) |

289.0712 245.1203 245.1210 |

Procyanidin B Catechin Epicatechin |

0.30 ± 0.03 0.12 ± 0.02 0.58 ± 0.04 |

- - - |

42.43 ± 2.05 26.06 ± 1.13 140.39 ± 5.97 |

| RBF HYDROXYCINNAMIC ACID DERIVATIVES | ||||||||

| 8 9 10 11 |

9.61 12.60 14.30 14.93 |

278, 320 234, 316 234, 316 235, 325 |

341.0880 (-) 325.0933 (-) 325.0933 (-) 163.0402 (-) |

161.0238 145.0294 145.0293 119.0496 |

Caffeoyl hexoside p-Coumaryl hexoside isomer 1 p-Coumaryl hexoside isomer 2 p-Coumaric acid |

0.10 ± 0.01 0.08 ± 0.01 0.07 ± 0.01 0.09 ± 0.02 |

- - Trace amounts Trace amounts |

19.98 ± 0.96 27.72 ± 1.08 Trace amounts Trace amounts |

| RBF FLAVONOLS | ||||||||

| 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

22.19 23.35 23.69 24.41 24.62 25.88 28.45 29.52 |

254, 360 262, 363 266, 354 268, 354 272, 355 266, 348 256, 360 256, 360 |

433.0417 (-) 300.9992 (-) 463.0874 (-) 463.0882 (-) 477.0679 (-) 461.0733 (-) 475.0525 (-) 475.0525 (-) |

300.9982 229.0131 301.0334 301.0354 301.0345 285.0391 300.9978 299.9904 |

Ellagic acid-O-pentoside Ellagic acid Quercetin-3-O-galactoside Quercetin-3-O-glucoside Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide Kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide Ellagic acid acetyl pentoside isomer 1 Ellagic acid acetyl pentoside isomer 2 |

Trace amounts 0.21 ± 0.03 0.14 ± 0.01 Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts |

Trace amounts Trace amounts 19.45 ± 1.37 Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts Trace amounts |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).