Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

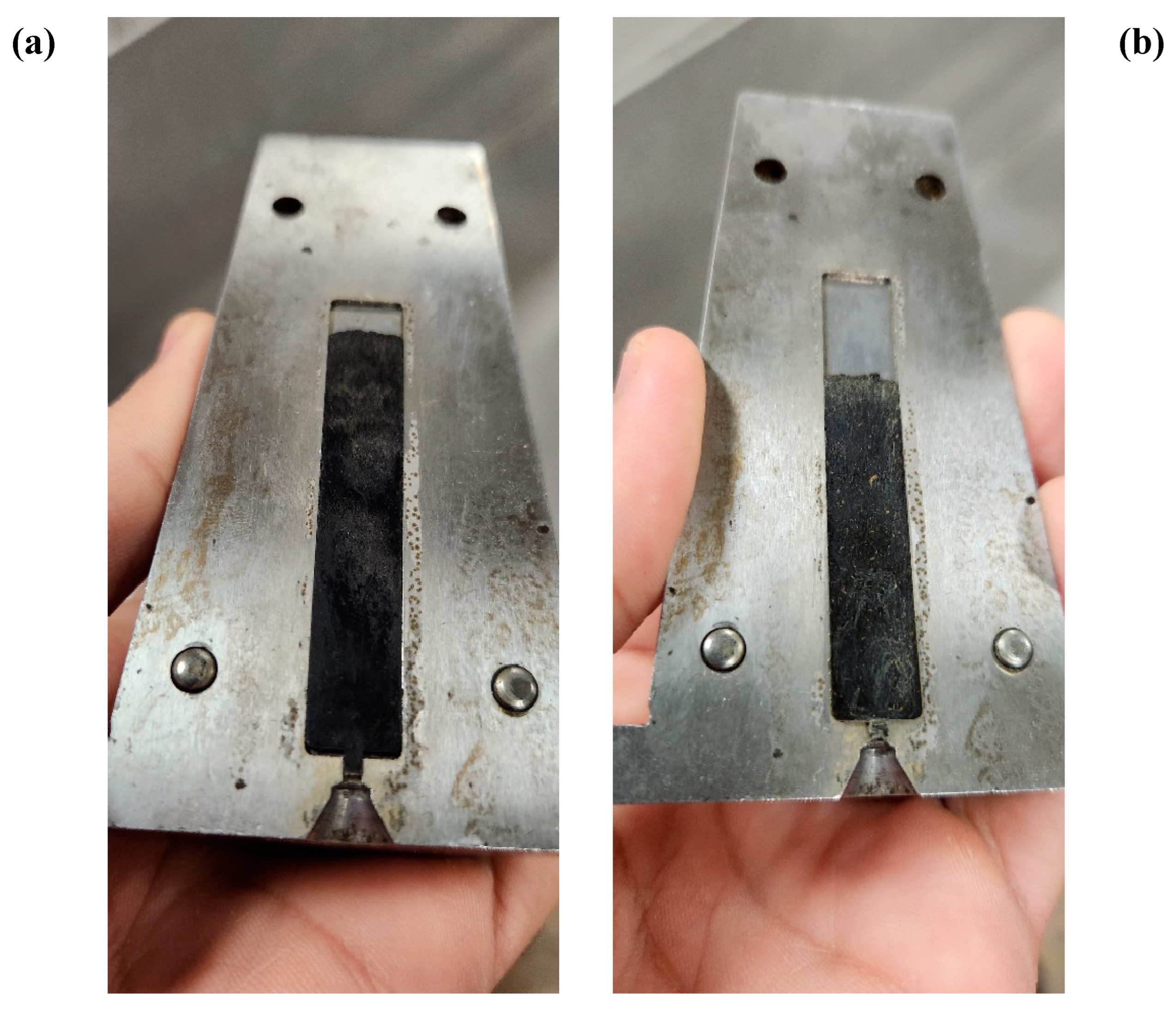

2.2. Preparation of Specimens

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Isothermal Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.3.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.3.3. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

2.3.4. Tensile Tests

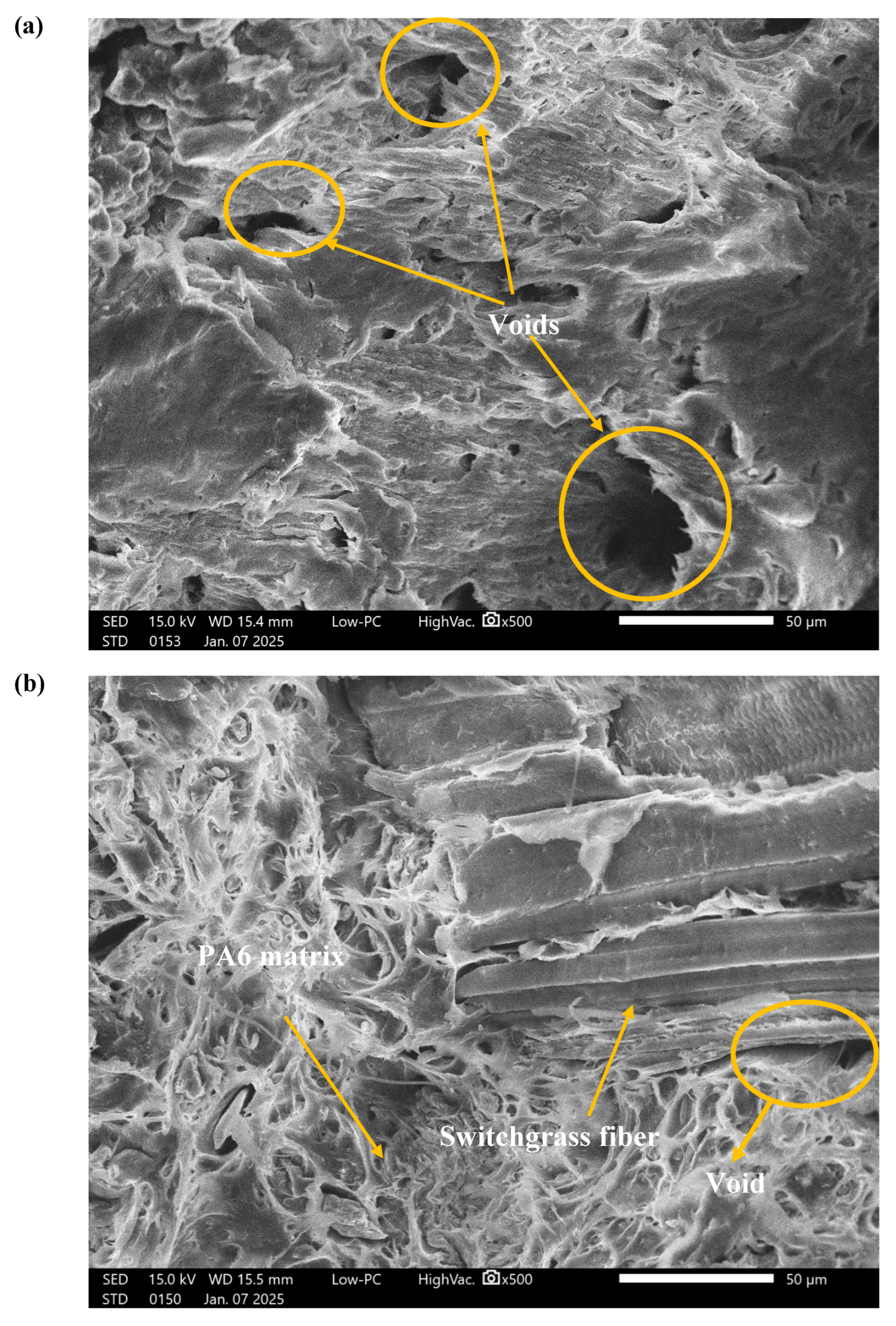

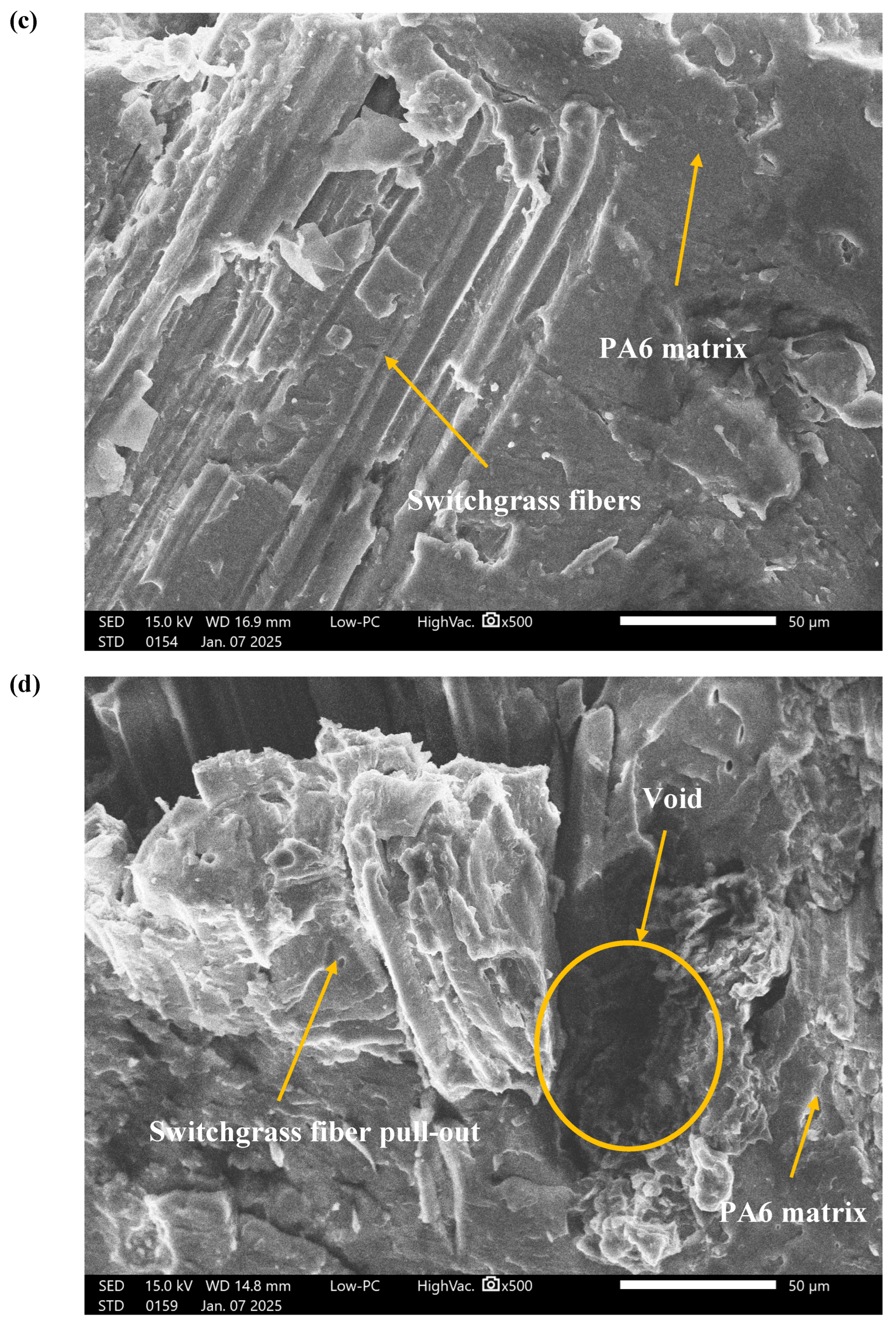

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.6. Melt Flow Rate (MFR)

3. Results

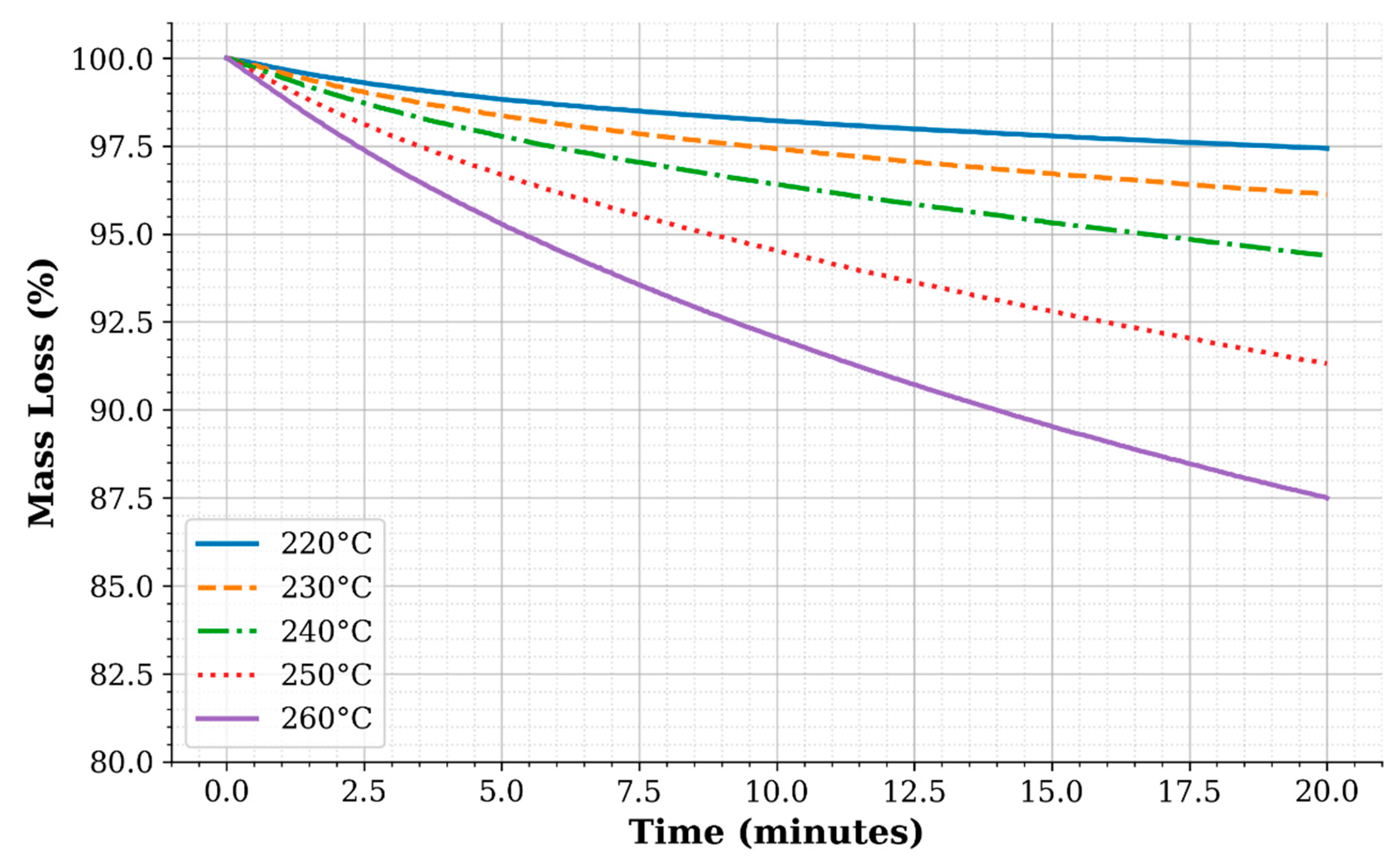

3.1. Isothermal TGA

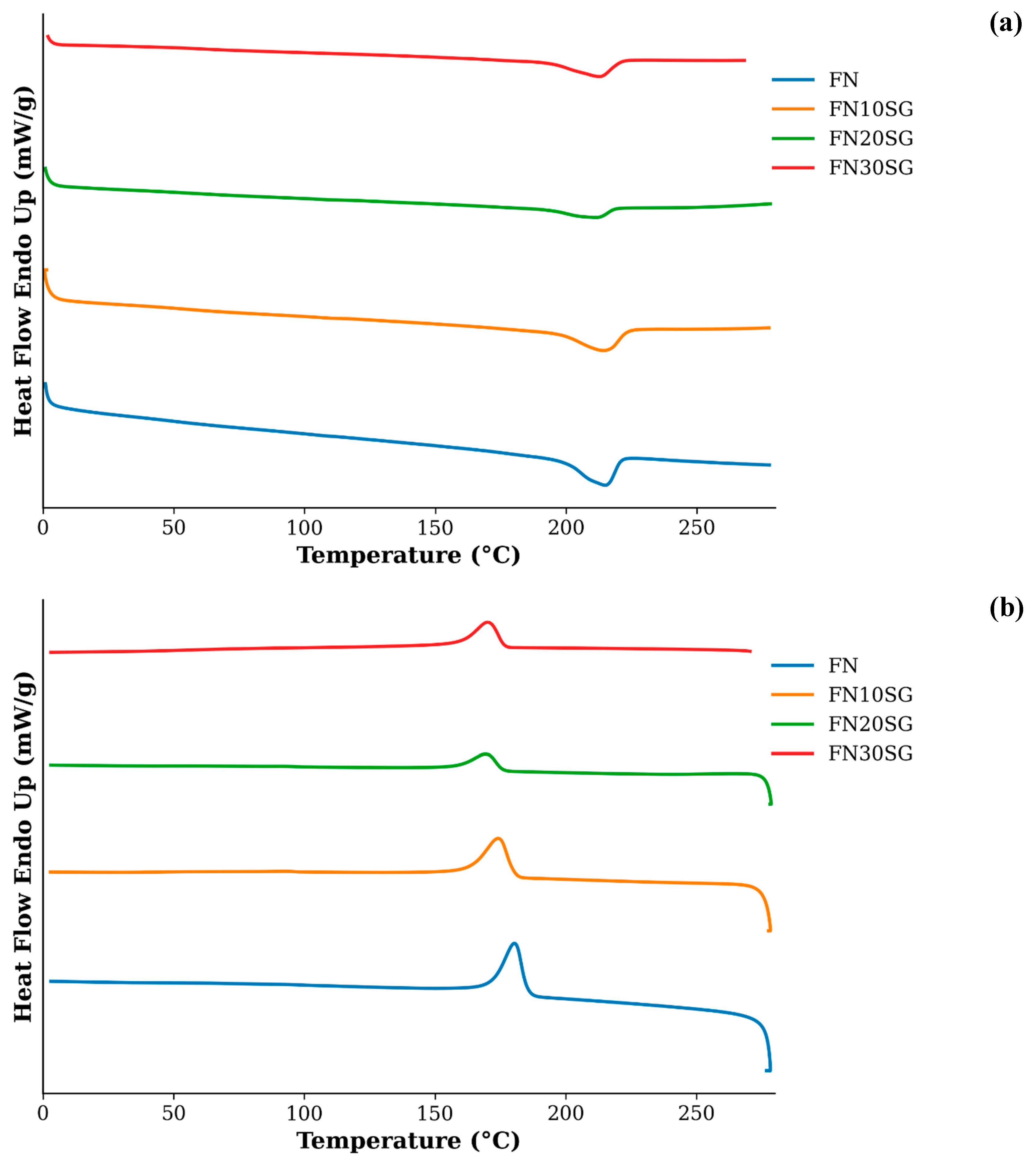

3.2. DSC

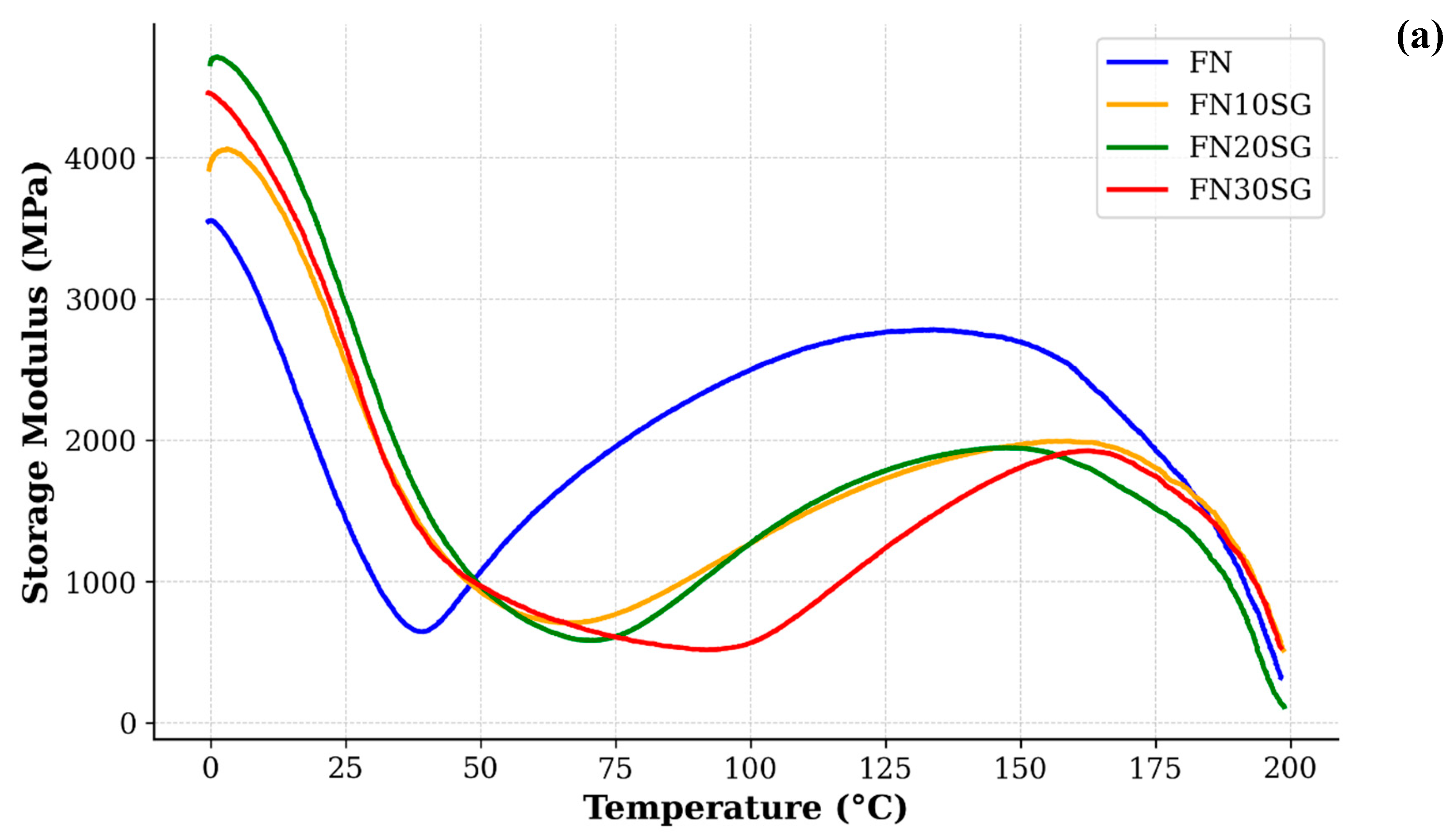

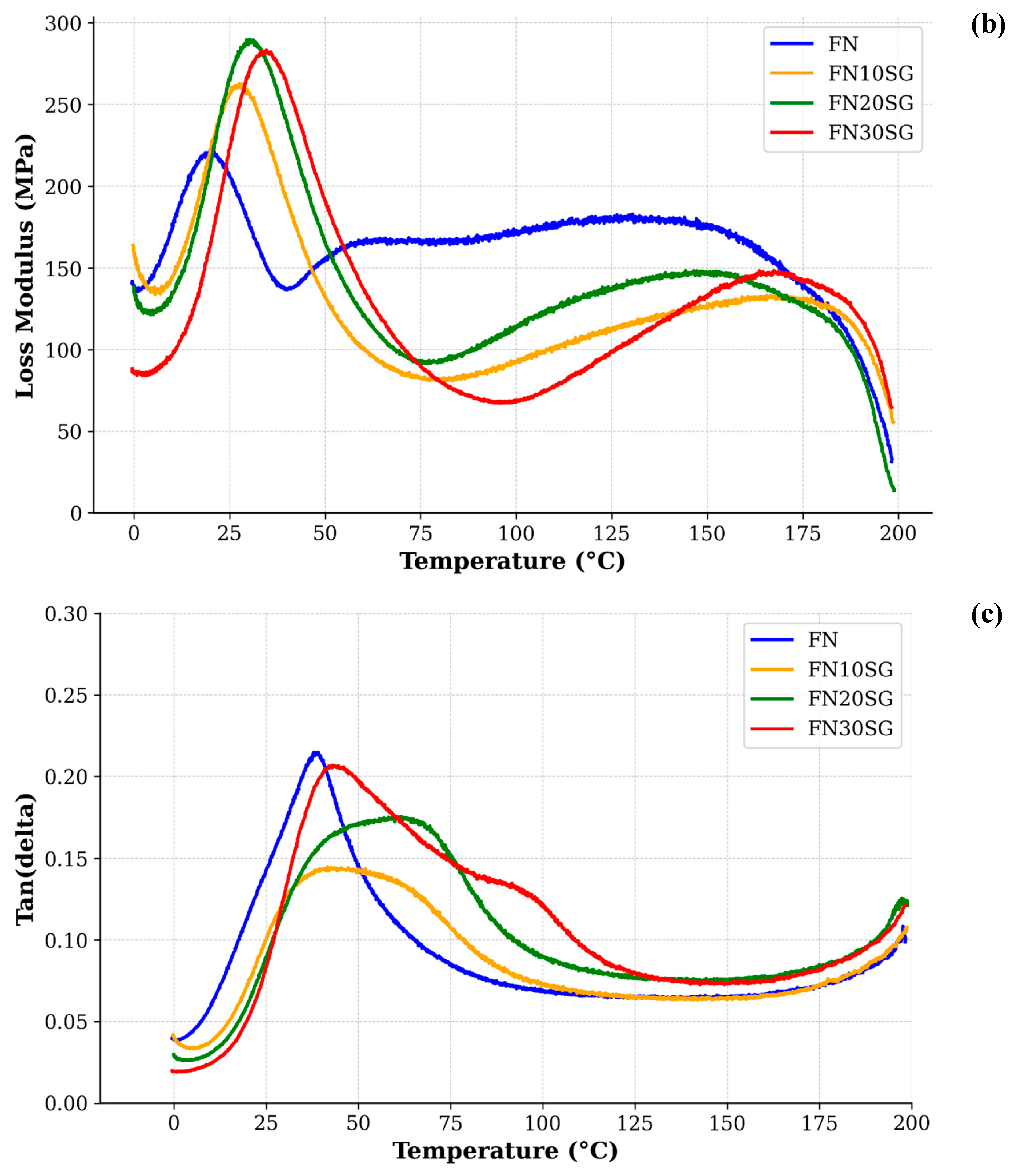

3.3. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

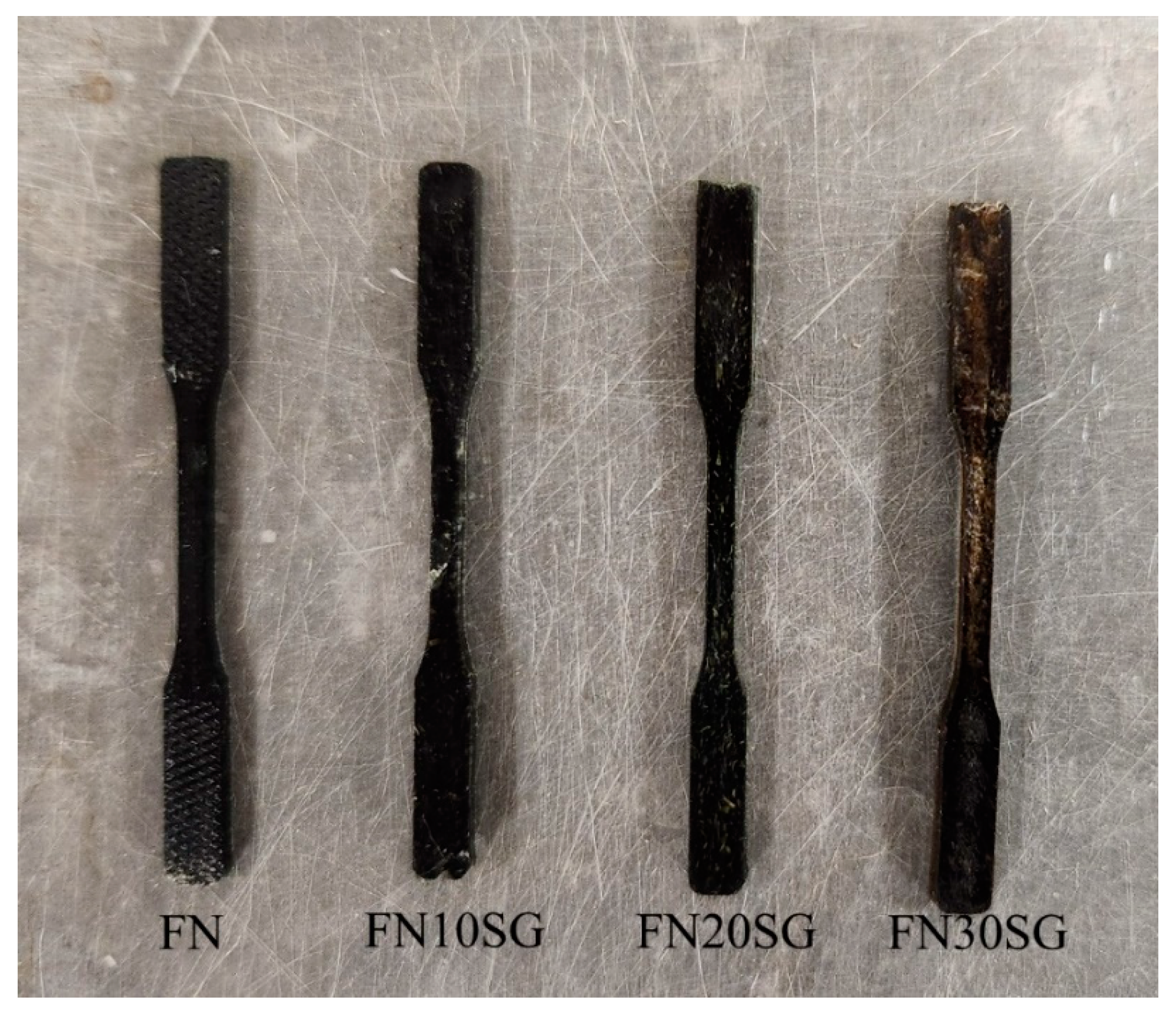

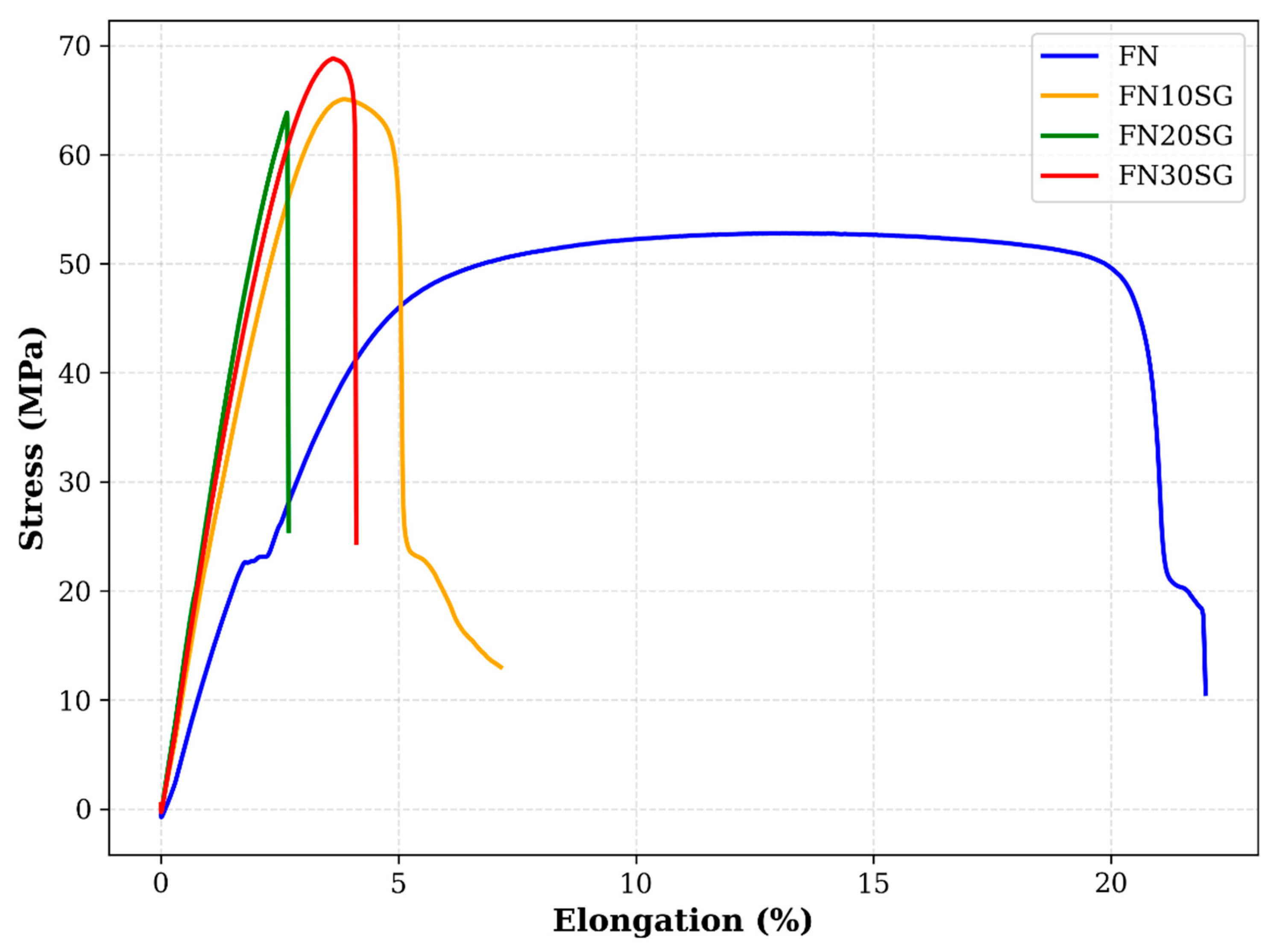

3.4. Tensile Tests

3.5. Melt Flow Rate

4. Conclusions

References

- Macfadyen, G.; Huntington, T.; Cappell, R. Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear. In UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No. 185; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 523; UNEP/FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242491383_Abandoned_Lost_or_Otherwise_Discarded_Fishing_Gear. (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy (2004) - "U.S. Ocean Action Plan: The Bush Administration's Response to the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy.". Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/data/oceans/coris/library/NOAA/other/us_ocean_action_plan_2004.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- L. Lebreton et al. Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- K. Richardson, B.D. Hardesty, and C. Wilcox, “Estimates of fishing gear loss rates at a global scale: A literature review and meta-analysis. Fish and Fisheries. 2019; 20, 1218–1231. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Breen, “Report of the working group on ghost fishing. in Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Marine Debris, R.S. Shomura and M. L. Godfrey, Eds., NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-154, 1990, pp. 571–599.

- M. Y. Kondo et al. Recent advances in the use of Polyamide-based materials for the automotive industry. Polímeros 2022, 32. [CrossRef]

- H.-D. Nguyen-Tran, V.-T. Hoang, V.-T. Do, D.-M. Chun, and Y.-J. Yum. Effect of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes on the Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide-6/Polypropylene Composites for Lightweight Automotive Parts. Materials. 2018; 11, 429. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. CO₂ Emission Performance Standards for Cars and Vans. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/transport/road-transport-reducing-co2-emissions-vehicles/co2-emission-performance-standards-cars-and-vans_en?u. (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- “ Multi-Pollutant Emissions Standards for Model Years 2027 and Later Light-Duty and Medium-Duty Vehicles. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-04-18/pdf/2024-06214.pdf. (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- V. Chauhan, T. Kärki, and J. Varis. Review of natural fiber-reinforced engineering plastic composites, their applications in the transportation sector and processing techniques. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials. 2022; 35, 1169–1209. [CrossRef]

- H. Uematsu et al. Relationship between crystalline structure of polyamide 6 within carbon fibers and their mechanical properties studied using Micro-Raman spectroscopy. Polymer (Guildf). 2021; 223, 123711. [CrossRef]

- N. Zaldua et al. Nucleation and Crystallization of PA6 Composites Prepared by T-RTM: Effects of Carbon and Glass Fiber Loading. Polymers (Basel). 2019; 11, 1680. [CrossRef]

- S. Mosey, F. Korkees, A. Rees, and G. Llewelyn. Investigation into fibre orientation and weldline reduction of injection moulded short glass-fibre/polyamide 6-6 automotive components. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials. 2020; 33, 1603–1628. [CrossRef]

- F. Caputo, G. Lamanna, A. De Luca, and E. Armentani. Thermo-Mechanical Investigation on an Automotive Engine Encapsulation System Made of Fiberglass Reinforced Polyamide PA6 GF30 Material. Macromol Symp 2020, 389. [CrossRef]

- T. Güler, E. Demirci, A.R. Yıldız, and U. Yavuz. Lightweight design of an automobile hinge component using glass fiber polyamide composites. Materials Testing. 2018; 60, 306–310. [CrossRef]

- T. Ishikawa et al. Overview of automotive structural composites technology developments in Japan. Compos Sci Technol. 2018; 155, 221–246. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Joshi, L.T. Drzal, A.K. Mohanty, and S. Arora. Are natural fiber composites environmentally superior to glass fiber reinforced composites?. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2004; 35, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- M. Patel, C. Bastioli, L. Marini, and E. Würdinger. Life-cycle Assessment of Bio-based Polymers and Natural Fiber Composites. in Biopolymers Online, A. Steinbüchel, Ed., Wiley, 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. Corbière-Nicollier, B. Gfeller Laban, L. Lundquist, Y. Leterrier, J.-A. E. Månson, and O. Jolliet. Life cycle assessment of biofibres replacing glass fibres as reinforcement in plastics. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2001; 33, 267–287. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Foulk, D.E. Akin, and R. B. Dodd. New Low Cost Flax Fibers for Composites. Mar. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Thomason and J. L. Rudeiros-Fernández. Thermal degradation behaviour of natural fibres at thermoplastic composite processing temperatures. Polym Degrad Stab. 2021; 188, 109594. [CrossRef]

- N. Abdullah, K. Abdan, M.H.M. Roslim, M.N. Radzuan, A.R. Shafi, and L. C. Hao. Properties of kenaf fiber-reinforced polyamide 6 composites. e-Polymers 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- E. Erbas Kiziltas, H.-S. Yang, A. Kiziltas, S. Boran, E. Ozen, and D. J. Gardner. Thermal Analysis of Polyamide 6 Composites Filled by Natural Fiber Blend. Bioresources 2016, 11. [CrossRef]

- S. FALASCA, S. Pitta-Alvarez, and C. MIRANDA DEL FRESNO. Possibilities for Growing Switch-grass (Panicum virgatum) as Second Generation Energy Crop in Dry-subhumid, Semiarid and Arid Regions of the Argentina. Journal of Central European Agriculture. 2017; 18, 95–116. [CrossRef]

- S. Sahoo, M. Misra, and A. K. Mohanty. Biocomposites From Switchgrass and Lignin Hybrid and Poly(butylene succinate) Bioplastic: Studies on Reactive Compatibilization and Performance Evaluation. Macromol Mater Eng. 2014; 299, 178–189. [CrossRef]

- M. J. A. van den Oever, H.W. Elbersen, E.R.P. Keijsers, R.J.A. Gosselink, and B. de Klerk-Engels. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatumL.) as a reinforcing fibre in polypropylene composites. J Mater Sci. 2003; 38, 3697–3707. [CrossRef]

- Ford. Ford Bronco Sport Becomes First Vehicle to Feature Parts Made of 100% Recycled Ocean Plastic. Available online: https://media.ford.com/content/fordmedia/fna/us/en/news/2021/12/08/ford-bronco-sport-recycled-ocean-plastic.html. (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- BMW. Recycled fishing nets for the Neue Klasse. Available online: https://www.bmwgroup.com/en/news/general/2022/recycled-plastics.html. (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Blaine, R.L. Polymer Heats of Fusion; Thermal Applications Note TN048; TA Instruments: New Castle, DE, USA, 1990; Available online: https://www.tainstruments.com/pdf/literature/TN048.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- “Standard Test Method for Melt Flow Rates of Thermoplastics by Extrusion Plastometer, ASTM D1238. West Conshohocken, PA.

- S. Liang, H. Nouri, and E. Lafranche. Thermo-compression forming of flax fibre-reinforced polyamide 6 composites: influence of the fibre thermal degradation on mechanical properties. J Mater Sci. 2015; 50, 7660–7672. [CrossRef]

- J. Cui et al. Effects of Thermal Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Fiber Bundles. Materials. 2023; 16, 1239. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gao, X.-M. Wang, H. Wan, and G. Brunette. Binderless panels made with black spruce bark. Bioresources. 2011; 6, 3960–3972. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Prins, K.J. Ptasinski, and F. J. J. G. Janssen. Torrefaction of wood part 1. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2006; 77, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Prins, K.J. Ptasinski, and F. J. J. G. Janssen. Torrefaction of wood part 2. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2006; 77, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- S. Liang, H. Nouri, and E. Lafranche. Thermo-compression forming of flax fibre-reinforced polyamide 6 composites: influence of the fibre thermal degradation on mechanical properties. J Mater Sci. 2015; 50, 7660–7672. [CrossRef]

- E. Klata, K. Van de Velde, and I. Krucińska. DSC investigations of polyamide 6 in hybrid GF/PA 6 yarns and composites. Polym Test. 2003; 22, 929–937. [CrossRef]

- N. Abdullah, K. Abdan, C.H. Lee, M.H. Mohd Roslim, M.N. Radzuan, and A. R. shafi. Thermal properties of wood flour reinforced polyamide 6 biocomposites by twin screw extrusion. Physical Sciences Reviews. 2023; 8, 5153–5164. [CrossRef]

- Z. Huang, Q. Yin, Q. Wang, P. Wang, T. Liu, and L. Qian. Mechanical properties and crystallization behavior of three kinds of straws/nylon 6 composites. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017; 103, 663–668. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhu, Y. Guo, Y. Chen, and S. Liu. Low Water Absorption, High-Strength Polyamide 6 Composites Blended with Sustainable Bamboo-Based Biochar. Nanomaterials. 2020; 10, 1367. [CrossRef]

- E. Erbas Kiziltas, H.-S. Yang, A. Kiziltas, S. Boran, E. Ozen, and D. J. Gardner. Thermal Analysis of Polyamide 6 Composites Filled by Natural Fiber Blend. Bioresources 2016, 11. [CrossRef]

- D. Chukov, S. Nematulloev, M. Zadorozhnyy, V. Tcherdyntsev, A. Stepashkin, and D. Zherebtsov. Structure, Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Polyphenylene Sulfide and Polysulfone Impregnated Carbon Fiber Composites. Polymers (Basel). 2019; 11, 684. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammed Interfacial bonding mechanisms of natural fibre-matrix composites: An overview. Bioresources 2022, 17.; et al. M. Mohammed et al. Interfacial bonding mechanisms of natural fibre-matrix composites: An overview. Bioresources 2022, 17. [CrossRef]

- S. Bahlouli, A. Belaadi, A. Makhlouf, H. Alshahrani, M.K.A. Khan, and M. Jawaid. Effect of Fiber Loading on Thermal Properties of Cellulosic Washingtonia Reinforced HDPE Biocomposites. Polymers (Basel). 2023; 15, 2910. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Sreenivasan, N. Rajini, A. Alavudeen, and V. Arumugaprabu. Dynamic mechanical and thermo-gravimetric analysis of Sansevieria cylindrica/polyester composite: Effect of fiber length, fiber loading and chemical treatment. Compos B Eng. 2015; 69, 76–86. [CrossRef]

- N. Hameed, P.A. Sreekumar, B. Francis, W. Yang, and S. Thomas. Morphology, dynamic mechanical and thermal studies on poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile) modified epoxy resin/glass fibre composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2007; 38, 2422–2432. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Mofokeng, A.S. Luyt, T. Tábi, and J. Kovács. Comparison of injection moulded, natural fibre-reinforced composites with PP and PLA as matrices. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials. 2012; 25, 927–948. [CrossRef]

- J. Biagiotti, D. Puglia, and J. M. Kenny. A Review on Natural Fibre-Based Composites-Part I. Journal of Natural Fibers. 2004; 1, 37–68. [CrossRef]

- S. Rodríguez-Llamazares, A. Zuñiga, J. Castaño, and L. R. Radovic. Comparative study of maleated polypropylene as a coupling agent for recycled low-density polyethylene/wood flour composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011; 122, 1731–1741. [CrossRef]

- N. Bakar, C.Y. Chee, L.C. Abdullah, C.T. Ratnam, and N. Azowa. Effect of methyl methacrylate grafted kenaf on mechanical properties of polyvinyl chloride/ethylene vinyl acetate composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2014; 63, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- K. Panyasart, N. Chaiyut, T. Amornsakchai, and O. Santawitee. Effect of Surface Treatment on the Properties of Pineapple Leaf Fibers Reinforced Polyamide 6 Composites. Energy Procedia. 2014; 56, 406–413. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Alonso-Montemayor et al. Enhancing the Mechanical Performance of Bleached Hemp Fibers Reinforced Polyamide 6 Composites: A Competitive Alternative to Commodity Composites. Polymers (Basel). 2020; 12, 1041. [CrossRef]

- MITSUBISHI CHEMICAL GROUP. Nylatron MC 907/Ertalon 6 PLA PA6. https://www.mcam.com/mam/54356/GEP-Ertalon%E2%84%A2%206PLA%20PA6_en_US.pdf.

- Celanese Corporation. Nylon 6 Unfilled Natural NXH-01 NC. Available online: https://materials.ulprospector.com/en/document?e=235763. (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- ESTER INDUSTRIES LTD. Product Data Sheet ESTOPLAST XU150BB01 [PA6-UF] Compound. Available online: https://www.esterindustries.com/sites/default/files/ep-products/XU150BB01.pdf. (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Sinopec. Sinopec Low Viscosity Nylon 6 Chips (BL3240) with High Quality and Best Price. Available online: https://sinopecgt.en.made-in-china.com/product/gmsRyieufSWv/China-Sinopec-Low-Viscosity-Nylon-6-Chips-Bl3240-with-High-Quality-and-Best-Price.html. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Plastcom. SLOVAMID® 6 GF 10. Available online: https://materials.ulprospector.com/en/document?e=141876. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- MatWeb. Aclo Accutech Nylon 6 NY0730G10L Glass Reinforced. Available online: https://www.matweb.com/search/datasheet.aspx?matguid=38c7dc0df1f74d8092c5c8a60cf3ff00. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- MatWeb. Aclo Accutech Nylon 6 NY0730G20L Glass Reinforced. Available online: https://www.matweb.com/search/datasheet.aspx?matguid=c98f04130fdc4d529a360729abe5655d. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- MatWeb. Polyplastic Compounds Armamid® PA6 GF 20-3FR Nylon 6, 20% Glass Fiber Reinforced. Available online: https://www.matweb.com/search/datasheettext.aspx?matguid=6077e0d67eb3495999df024838db5f6f. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Ltd. Suzhou Xinyite Plastic Technology Co.. Nylon PA6 GF30 Glass Fiber 30% Material Polyamide Pellets Manufacturer. Available online: https://xinyite.en.made-in-china.com/product/ombYVnWHgzkS/China-Nylon-PA6-GF30-Glass-Fiber-30-Material-Polyamide-Pellets-Manufacturer.html. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- DuPont. DuPont Mobility and Materials Zytel® 73G30HSL NC010 Nylon 6. Available online: https://www.matweb.com/search/datasheet.aspx?matguid=e110356e70ad4f568706c84f61ccd4c9. (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- J. Li et al. Strength-plasticity synergetic CF/PEEK composites obtained by adjusting melt flow rate. Polymer (Guildf). 2024; 305, 127186. [CrossRef]

- E. Ozen, A. Kiziltas, E.E. Kiziltas, and D. J. Gardner. Natural fiber blend—nylon 6 composites. Polym Compos. 2013; 34, 544–553. [CrossRef]

| Formulation | Fishing nets | Switchgrass fibers |

|---|---|---|

| FN | 100 | 0 |

| FN10SG | 90 | 10 |

| FN20SG | 80 | 20 |

| FN30SG | 70 | 30 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Extruder used | Thermo Fischer Process 11 Twin-screw extruder (Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Extruder temperature zone | 8 zones (Zone 1-4 : 240 °C, Zone 5 : 230 °C, Zone 6-7 :215°C, Zone 8 : 210°C) |

| Die exit diameter | 2 mm |

| Screw speed | 120 RPM |

| Injection molding machine | HAAKETM MiniJet Pro (Waltham, MA, USA) |

| Molding time | 10 s |

| Molding pressure | 600 bars |

| Cylinder temperature | 245°C |

| Mold temperature | Room temperature |

| Samples | ΔHm,PA6 (J/g) | XPA6 (%) | Tm,PA6 (°C) | Tc,PA6 (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FN | 51 | 26.84 | 215 | 183 |

| FN10SG | 37 | 21.63 | 214 | 177 |

| FN20SG | 24 | 15.79 | 212 | 173 |

| FN30SG | 24 | 18.04 | 213 | 170 |

| Formulation | Tensile strength (Mpa) | Young’s modulus (Gpa) | Elongation at break (%) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental formulations | ||||

| FN | 54.58 ± 4.22 | 1.09 ± 0.28 | 49.00 ± 29.00 | - |

| FN10SG | 55.37 ± 2.41 | 2.14 ± 0.31 | 3.91 ± 1.60 | - |

| FN20SG | 56.97 ± 5.54 | 2.45 ± 0.18 | 2.38 ± 0.30 | - |

| FN30SG | 67.21 ± 3.77 | 2.46 ± 0.43 | 4.14 ± 0.44 | - |

| Neat commercial PA6 | ||||

| Nylatron MC 907/Ertalon 6 PLA PA6 | 88 | 3.6 | 25 | [54] |

| Nylon 6 Unfilled Natural NXH-01 NC | 72 | 3.1 | 60 | [55] |

| ESTOPLAST XU150BB01 | 55 | - | 10 | [56] |

| Formulation Type | Fiber Content (%) | Sample Name | Testing temperature and mass / norm | MFR (g/10 min) | Fiber Type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 0 | FN | 235 °C#break#2.16 kg | 19.35 ± 1.94 | Switchgrass | --- |

| 10 | FN10SG | 235 °C#break#2.16 kg | 15.82 ± 2.59 | Switchgrass | --- | |

| 20 | FN20SG | 235 °C#break#2.16 kg | 8.77 ± 0.71 | Switchgrass | --- | |

| 30 | FN30SG | 235 °C#break#2.16 kg | 8.63 ± 0.8 | Switchgrass | --- | |

| Commercial | 0 | SINOPEC BL3240 | 230 °C#break#2.16 kg | 32.3 | Glass | [57] |

| 10 | SLOVAMID 6 GF 10 | 270 °C#break#0.325 kg | 3 | Glass | [58] | |

| 10 | Aclo Accutech Nylon 6 NY0730G10L | ASTM D1238 | 4 | Glass | [59] | |

| 20 | Aclo Accutech Nylon 6 NY0730G20L | ASTM D1238 | 6 | Glass | [60] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).