Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Soil Chemical Characterisation

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Fungi Strains

2.3. Lipid Extraction and FAME Production

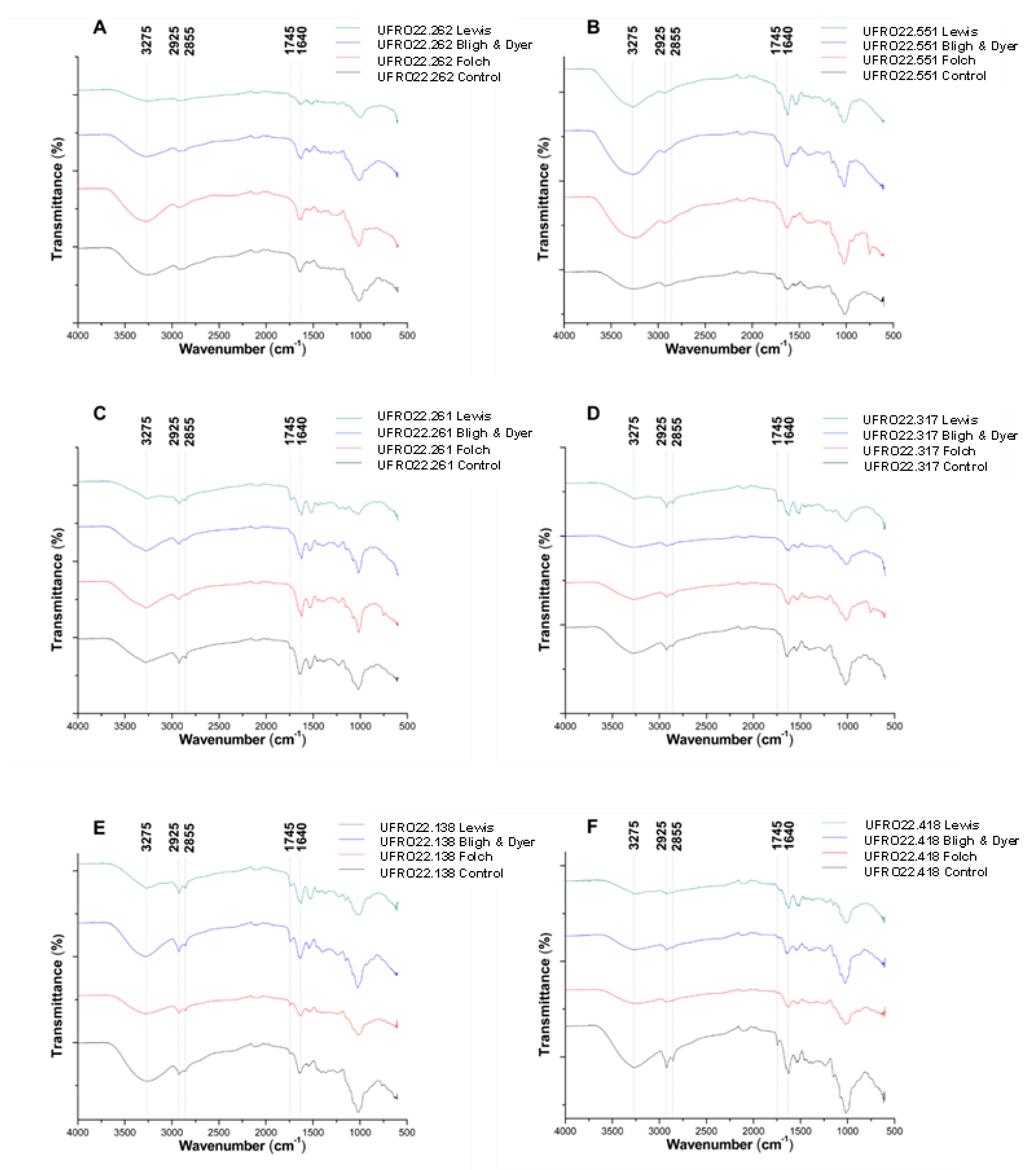

2.4. Monitoring Lipid Extraction with Infrared Spectroscopy

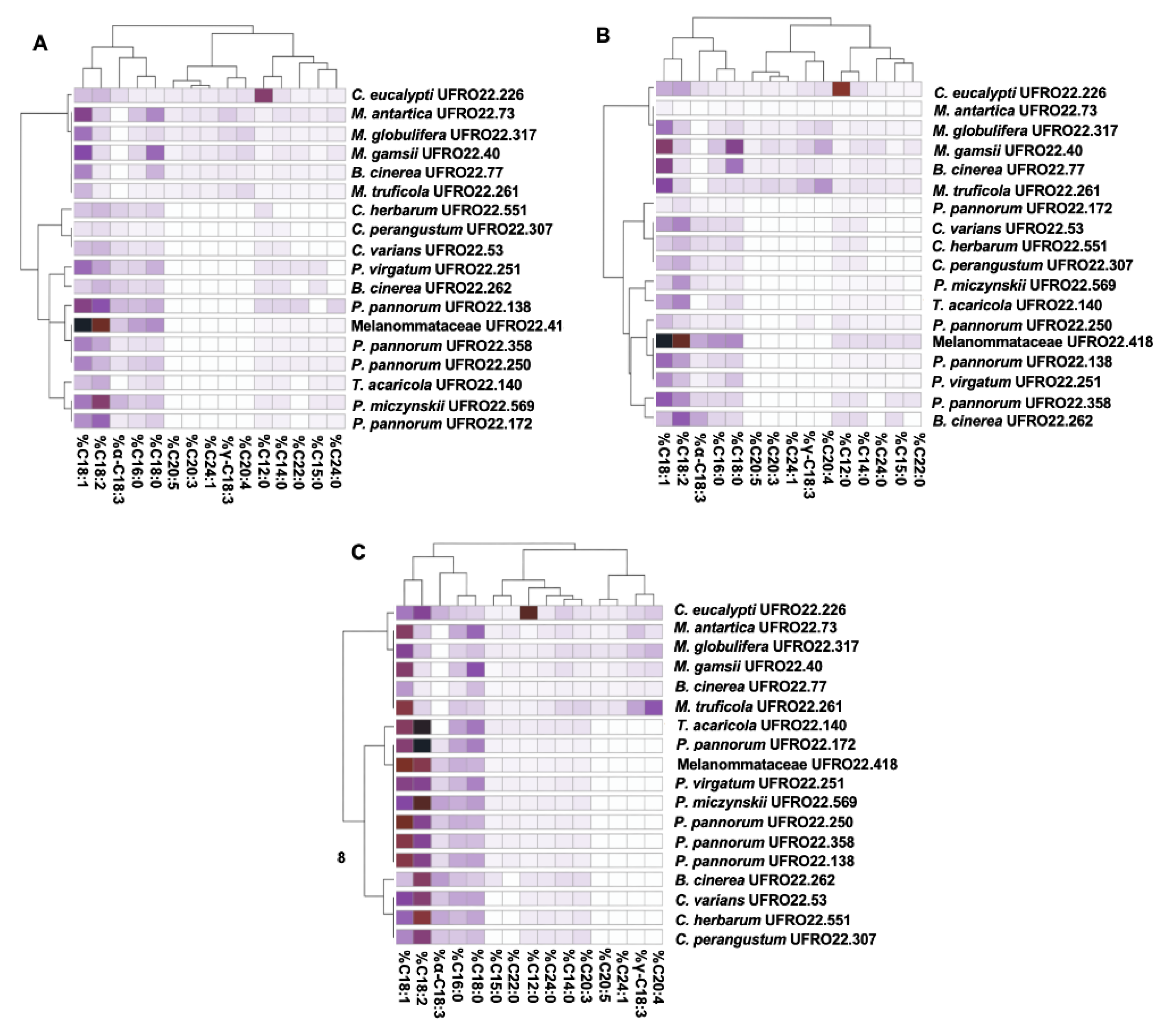

2.5. Fatty Acid Identification and Quantification

3. Materials and Methods

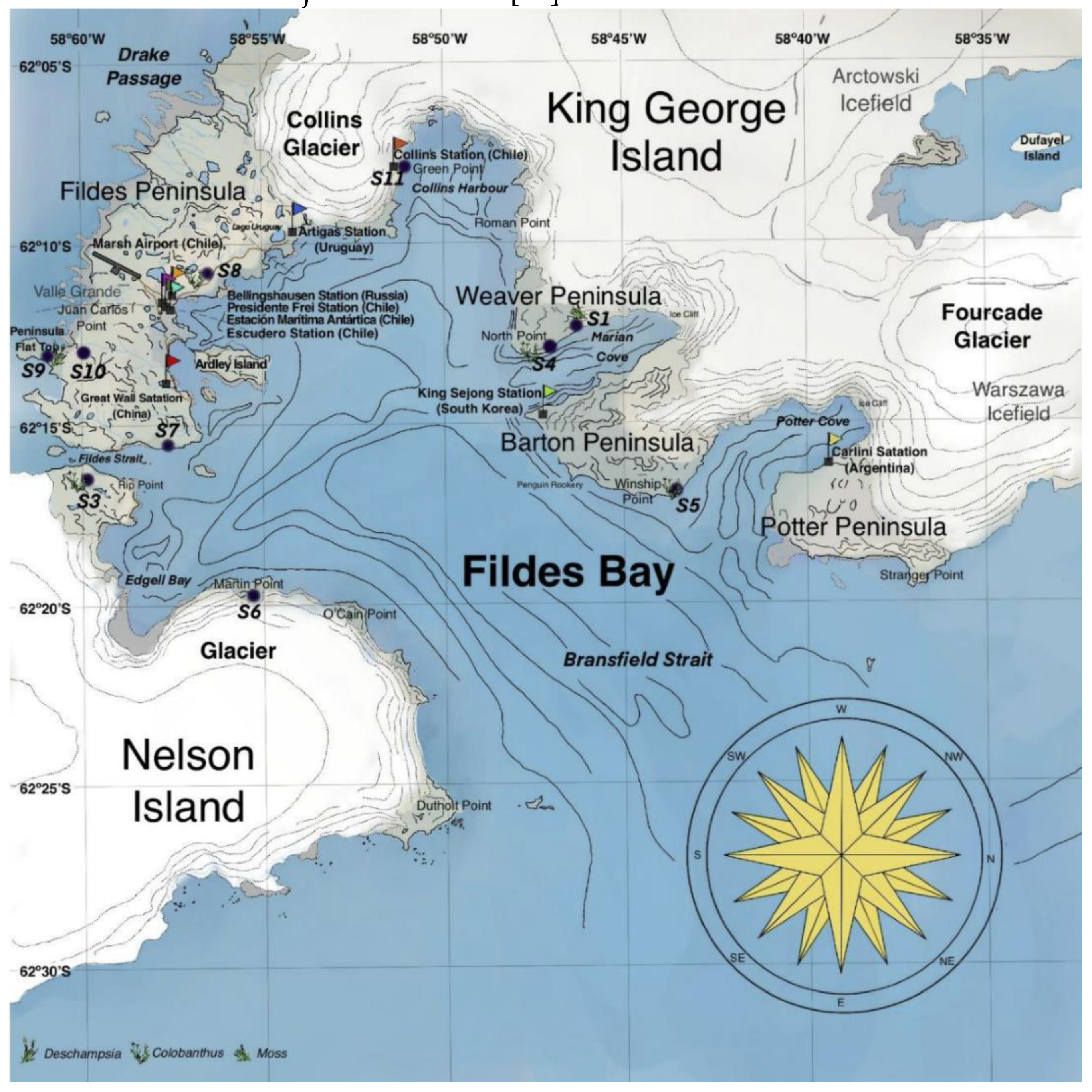

3.1. Soil Sampling

3.1.2. Soil Chemical Characterisation

3.2. Fungi Isolation

3.3. Fungi Identification Based on Morphological Analysis

3.4. Fungi Identification Based on Molecular Biology Analysis

3.5. Fungi Cultivation for Biomass Production

3.6. Lipid Extraction from Fungal Biomass

3.6.1. Folch Extraction Method

3.6.2. Bligh & Dyer Extraction Method

3.6.3. Lewis Direct Transesterification Extraction

3.7. Monitoring Lipid Extraction with Infrared Spectroscopy

3.8. Chemical Characterisation and Quantification of Lipids by GC-MS and GC-FID

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pearce, D.A. Extremophiles in Antarctica: Life at low temperatures. In: Adaption of Microbial Life to Environmental Extreme, 2nd ed.; Stan-Lotter, H., Fendrihan, S. Eds. Springer, Vienna, Italy, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Coleine, C.; Stajich, J. E.; Selbmann, L. Fungi are key players in extreme ecosystems. TREE 2022, 37, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, V.; Sepúlveda, M.; Costa, J.; Galeano, P.; Cornejo, P.; Santos, C. Distribución geográfica y potencial biotecnológico de hongos filamentosos cultivables en suelos de la Bahía de Fildes (Antártica). Bol. Micol. 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, V. M.; Furbino, L. E.; Santiago, I. F.; Pellizzari, F. M.; Yokoya, N. S.; Pupo. D.; et al. Diversity and bioprospecting of fungal communities associated with endemic and cold-adapted macroalgae in Antarctica. ISME 2013, 7, 1434–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, A.; Convey, P.; Gonzalez, M.; Smykla, J.; Alias, S. A. Effects of temperature on extracellular hydrolase enzymes from soil microfungi. Polar Biol. 2017, 41, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weete, J. D. Lipid biochemistry of fungi and other organisms, 1st ed.; Springer, New York, USA, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Caramujo, M. The Various Roles of Fatty Acids. Molecules 2018, 23, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapaval, V.; Afseth, N.; Vogt, G.; Kohler, A. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for the prediction of fatty acid profiles in Mucor fungi grown in media with different carbon sources. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forfang, K.; Zimmermann, B.; Kosa, G.; Kohler, A.; Shapaval, V. FTIR Spectroscopy for evaluation and monitoring of lipid extraction efficiency for oleaginous fungi. Dawson TL, editor. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0170611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passoth, V. (2017). Lipids of Yeasts and Filamentous Fungi and Their Importance for Biotechnology. In: Biotechnology of Yeasts and Filamentous Fungi, 1ed; Sibirny, A. Springer, Cham. 2017, 149–204. [CrossRef]

- Athenaki, M.; Gardeli, C.; Diamantopoulou, P.; Tchakouteu, S. S.; Sarris, D.; Philippoussis, A.; et al. Lipids from yeasts and fungi: physiology, production and analytical considerations. J Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 336–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Tyagi, R. D. Lipids produced by filamentous fungi. In: Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals, 1st ed.; Soccol, C.R, Pandey, A., Carvalho, J.C., Tyagi, R. D.; 2022, 135–159. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, G. C. A.; Porto, B. A.; Amorim, S. S.; Zani, C. L.; de Almeida Alves, T. M.; Junior, P. A. S.; et al. Fungi in glacial ice of Antarctica: diversity, distribution and bioprospecting of bioactive compounds. Extremophiles 2020, 24, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhaseelan, H; Dinakaran, V. T.; Dahms, H-U.; Ahamed, J.M.; Murugaiah, S.G.; Krishnan M, et al. Recent Antimicrobial responses of halophilic microbes in clinical pathogens. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloor, W. R. The determination of small amounts of lipid in blood plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 1928, 77, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R. K.; Prasad, P.; Shang, X.; Keum, Y-S. Advances in lipid extraction methods—A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, T.; Nichols, P. D.; McMeekin, T. A. Evaluation of extraction methods for recovery of fatty acids from lipid-producing microheterotrophs. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2000, 43, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockheim, J. G. Antarctic soil properties and soilscapes. Ant. Terr. Microbiol. 2014, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L. H. Fungi of Antarctica. 1st ed.; Springer Cham, 2019; pp. 1–345. [CrossRef]

- Smykla, J.; Drewnik, M.; Szarek-Gwiazda, E.; Hii, Y. S.; Knap, W.; Emslie, S. D. Variation in the characteristics and development of soils at Edmonson Point due to abiotic and biotic factors, northern Victoria Land, Antarctica. CATENA. 2015, 132, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Gan, P.; Chen, A. Environmental controls on soil pH in planted forest and its response to nitrogen deposition. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza-Kasprzyk, J.; Paiva, T. de C.; Convey, P.; da Cunha, L. S. T.; Soares, T. A.; Zawierucha, K.; et al. Influence of marine vertebrates on organic matter, phosphorus and other chemical element levels in Antarctic soils. Polar Biol. 2022, 45, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.C.; Convey, P.; Newsham, K. K.; Hayward, S. A. L. Ecological consequences of a single introduced species to the Antarctic: terrestrial impacts of the invasive midge Eretmoptera murphyi on Signy Island. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2023, 180, 108965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, K. K.; Misiak, M.; Goodall-Copestake, W. P.; Dahl, M. S.; Boddy, L.; Hopkins, D. W.; et al. Experimental warming increases fungal alpha diversity in an oligotrophic maritime Antarctic soil. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1050372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, K. K. Diurnal temperature fluctuation inhibits the growth of an Antarctic fungus. Fungal Biol. 2023, 128, 2365–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L. M. D.; Lirio, J. M.; Coria, S.H.; Lopes, F. A. C.; Convey, P.; Carvalho-Silva, M.; et al. Diversity, distribution and ecology of fungal communities present in Antarctic lake sediments uncovered by DNA metabarcoding. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante, S. B.; da Silva, A. F.; Pradi, L.; Lacerda, J. W. F.; Tizziani, T.; Sandjo, L. P.; et al. Antarctic fungi produce pigment with antimicrobial and antiparasitic activities. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, D.S.; Thambugala, K. M.; de Silva, N. I.; Song, H-Y. ; Suwannarach, N.; Chen, F-S.; et al. An overview of Melanommataceae (Pleosporales, Dothideomycetes): Current insight into the host associations and geographical distribution with some interesting novel additions from plant litter. MycoKeys. 2024, 106, 43–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iverson, S. J.; Lang, S. L. C.; Cooper, M. H. Comparison of the Bligh and Dyer and Folch methods for total lipid determination in a broad range of marine tissue. Lipids. 2001, 36, 1283–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonaurio, R.; Della Torre, G.; Bellezza, G. Lipid composition of dicarboximide-sensitive and -resistant strains of Botrytis cinerea Pers. Phytopathol Mediterr. 1989, 28, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, L. L. D.; Oliver, J. E.; De Vilbiss, E. D.; Doss, R. P. Lipid composition of the extracellular matrix of Botrytis cinerea germlings. Phytochemistry. 2000, 53, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R. G.; Dancer, J.; O’Neill, E.; Harwood, J. L. Lipid composition of Botrytis cinerea and inhibition of its radiolabelling by the fungicide iprodione. New Phytol. 2003, 160, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. L.; Lin, Q.; Li, X. R.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y. X.; Qiao, D. R.; et al. Biodiversity of the oleaginous microorganisms in Tibetan Plateau. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, M. G.; Singh, J. Component fatty acids of Cladosporium herbarum fat. JCTB. 1985, 35, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Etten, J. L.; Gottlieb, D. Biochemical Changes During the Growth of Fungi II. Ergosterol and fatty acids in Penicillium atrovenetum. J. Bacteriol. 1965, 89, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, S.; Khan, S. A.; Saeed, M.; Bhatty, M. K.; Iqbal, M. Z. Studies on the lipid production by Penicillium lilacinum. Lipid / Fett. 1987, 89, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, B.; Hasmi, K.; Khan, F.; Shikh, D.; Mehmood, Z. Production of lipids by fermentation preliminary report. MJIAS. 1997, 10, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, B.; Lu, H.; Cao, Y.; Chen, R.; Yuan, Y. Phospholipid profiles of Penicillium chrysogenum in different scales of fermentations. Eng. Life Sci. 2013, 13, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T. H.; El-Gamal, M. S.; El-Ghonemy, D. H.; Awad, G. E.; Tantawy, A. E. Improvement of lipid production from an oil-producing filamentous fungus, Penicillium brevicompactum NRC 829, through central composite statistical design. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, B.; Kuncham, R.; Azeem, M. A.; et al. Screening and identification of oleaginous moulds for lipid production. J. Environ. Biol. 2017, 38, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langseter, A. M.; Dzurendova, S.; Shapaval, V.; Kohler, A.; Ekeberg, D.; Zimmermann, B. Evaluation and optimisation of direct transesterification methods for the assessment of lipid accumulation in oleaginous filamentous fungi. Microb. Cell Fact. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Fernando, L. D.; Fang, W.; Dickwella Widanage, M. C.; Wei, P.; Jin, C.; et al. A molecular vision of fungal cell wall organization by functional genomics and solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, P. D.; Klug, M.J. Characterization and differentiation of filamentous fungi based on Fatty acid composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 4136–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rossi, P.; Ambrico, A.; Del Fiore, A.; Trupo, M.; Blasi, L.; Beccaccioli, M.; et al. Antarctic fungi: A bio-source alternative to produce polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). bioRxiv. 2022, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.; Tian, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X. The Destructive fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea—Insights from genes studied with mutant analysis. Pathogens. 2020, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latvala, S.; Haapalainen, M.; Karisto, P.; Kivijärvi, P.; Jääskeläinen, O.; Suojala-Ahlfors, T. Changes in the prevalence of fungal species causing post-harvest diseases of carrot in Finland. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2024, 185, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, L.; Igarashi, Y.; Xie, D.; Li, N. Metabolomic differential analysis of interspecific interactions among white rot fungi Trametes versicolor, Dichomitus squalens and Pleurotus ostreatus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havaux, X.; Zeine, A.; Dits, A.; Denis, O. A new mouse model of lung allergy induced by the spores of Alternaria alternata and Cladosporium herbarummolds. CEI. 2004, 139, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G, A. ; Kendall, S. J.; Burden, R. S.; James, C. S.; Clark, T. The lipid compositions of two isolates of Cladosporium cucumerinum do not explain their differences in sensitivity to fungicides which inhibit sterol biosynthesis. Pestic. Sci. 1989, 26, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Behrendt, J.; Sutherland, A. J.; Griffiths, G. Synthetic molecular mimics of naturally occurring cyclopentenones exhibit antifungal activity towards pathogenic fungi. Microbiology. 2011, 157, 3435–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M. M.; Andolfi, A.; Nicoletti, R. The genus Cladosporium: A rich source of diverse and bioactive natural compounds. Molecules. 2021, 26, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinrucken, T. V.; Vitelli, J. S. Biocontrol of weedy Sporobolus grasses in Australia using fungal pathogens. BioControl. 2023, 68, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H-T. ; Chen, J-W.; Rathod, J.; Jiang, Y-Z.; Tsai, P-J.; Hung, Y-P.; et al. Lauric acid is an inhibitor of Clostridium difficile growth in vitro and reduces inflammation in a mouse infection model. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, M. V. S.; da Costa Sousa, N.; Paixão, P. E. G.; dos Santos Medeiros, E.; Abe, H. A.; Meneses, J. O.; et al. Is there antimicrobial property of coconut oil and lauric acid against fish pathogen? Aquaculture. 2021, 545, 737234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nie, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, T-Y. ; Liu, X-Y. Comparative genomics of Mortierellaceae provides insights into lipid metabolism: Two novel types of fatty acid synthase. J. Fungi. 2022, 8, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, C.; Kang, L.; Hang, B.; Yan, M.; Li, S.; et al. A subchronic toxicity study, preceded by an in utero exposure phase, with refined arachidonic acid-rich oil (RAO) derived from Mortierella alpina XM027 in rats. RTP. 2014, 70, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardhan, P.; Gohain, M.; Daimary, N.; Kishor, S.; Chattopadhyay, P.; Gupta, K.; et al. Microbial lipids from cellulolytic oleaginous fungus Penicillium citrinum PKB20 as a potential feedstock for biodiesel production. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, J. C.; Samson, R. A. Taxonomy of Penicillium section Citrina. Stud. Mycol. 2011, 70, 53–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houbraken, J.; Kocsubé, S.; Visagie, C. M.; Yilmaz, N.; Wang, X-C. ; Meijer, M.; et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 95, 5–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazanova, K. V.; Senik, S. V.; Kirtsideli, I. Yu.; Shavarda A., L. Metabolomic profiling and lipid composition of Arctic and Antarctic strains of micromycetes Geomyces pannorum and Thelebolus microsporus grown at different temperatures. Microbiology. 2019, 88, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotti, E.; Paolino, C.; Lancia, B.; Mercantini, R. Metabolic differences between two Antarctic strains of Geomyces pannorum. Curr. Microbiol. 1996, 32, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, RN.; Montiel, P. O.; Johnstone, K. Influence of growth temperature on lipid and soluble carbohydrate synthesis by fungi isolated from fellfield soil in the maritime Antarctic. Mycologia. 2000, 92, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konova IV, Sergeeva YaE, Galanina LA, Kochkina GA, Ivanushkina NE, Ozerskaya SM. Lipid synthesis by Geomyces pannorum under the impact of stress factors. Microbiol. 2009, 78, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannkuk, E. L.; Blair, H. B.; Fischer, A. E.; Gerdes, C. L.; Gilmore, D. F.; Savary, B. J.; et al. Triacylglyceride composition and fatty acyl saturation profile of a psychrophilic and psychrotolerant fungal species grown at different temperatures. Fungal Biol. 2014, 118, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.; Kafkewitz, D.; Somberg, E. W. Eucaryote thermophily: role of lipids in the growth of Talaromyces thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 156, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, J.; Fritsche, K. Linoleic acid. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, F.; Agostoni, C.; Borghi, C.; Catapano, A. L.; Cena, H.; Ghiselli, A.; et al. Dietary linoleic acid and human health: Focus on cardiovascular and cardiometabolic effects. Atherosclerosis. 2020, 292, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, R.; Santos, C.; Silva de Lima, J.; Aparecida Moreira, K.; de Souza-Motta M., C. Diversity of Penicillium in soil of Caatinga and Atlantic forest areas of Pernambuco, Brazil: an ecological approach. Nova Hedwig. 2013, 97, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, D.; Machuca, Á.; Fuentes-Ramirez, A.; Fernandez, N.; Cornejo, P. Shifts in soil traits and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis represent the conservation status of Araucaria araucana forests and the effects after fire events. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S. R, Sommers, L. E. Phosphorus. Agronomy Monographs. 1982, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Plaza, P.; Navas, M. J.; Wybraniec, S.; Michałowski, T.; Asuero, A. G. An overview of the Kjeldahl method of nitrogen determination. Part II. Sample Preparation, Working Scale, Instrumental Finish, and Quality Control. CRC. 2013, 43, 224–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J. I. A laboratory guide to common Penicillium species. Mycologia. 1987, 79, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, Z. Ornamentation types of conidia and conidiogenous structures in fasciculate Penicillium species using scanning electron microscopy. Bot. J. Linn. 1989, 99, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R. A.; Frisvad, J. C. Penicillium subgenus Penicillium: new taxonomic schemes and mycotoxins and other extrolites. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 49, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, M. F.; Pereira, L.; Santos, C. , Lima, N. Polyphasic identification and preservation of fungal diversity: Concepts and applications. Manag. Micro. Res. Environ 2013, 91–117. [CrossRef]

- Hoog, G. S.; Guarro, J.; Gené, J.; Ahmed, S. A. Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 4th edition. Publisher: Westerdijk Institute/Universitat Rovira i Virgili. Utrecht/Reus. 2019. http://atlasclinicalfungi.org.

- Rodrigues, P.; Venâncio A, Lima N. Toxic reagents and expensive equipment: are they really necessary for the extraction of good quality fungal DNA? Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 66, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T. J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols. 1990, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Pearce, M.; Tivey, A. R. N.; Basutkar, P.; Lee, J.; Edbali, O.; et al. Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W276–W279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L-T. ; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B. Q. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–W235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, K.; Groenewald, J. Z.; Braun, U.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Starink, M.; Hill, C. F.; et al. Biodiversity in the Cladosporium herbarum complex (Davidiellaceae, Capnodiales), with standardisation of methods for Cladosporium taxonomy and diagnostics. Stud. Mycol. 2007, 58, 105–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Stielow, B.; Hoffmann, K.; Petkovits, T.; Papp, T.; Vágvölgyi, C.; et al. A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the Mortierellales (Mortierellomycotina) based on nuclear ribosomal DNA. Mol. Phyl. and Evol. of Fungi. 2013, 30, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houbraken, J.; Visagie, C. M.; Meijer, M.; Frisvad, J. C.; Busby, P. E.; Pitt, J. I.; et al. A taxonomic and phylogenetic revision of Penicillium section Aspergilloides. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 373–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Denis, M.; Gené, J.; Sutton, D. A.; Wiederhold, N. P.; Cano-Lira, J. F.; Guarro, J. New species of Cladosporium associated with human and animal infections. Mol. Phyl. and Evol. of Fungi. 2016, 36, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, N.; Visagie, C. M.; Frisvad, J. C.; Houbraken, J.; Jacobs, K.; Samson, R. A. Taxonomic re-evaluation of species in Talaromyces section Islandici, using a polyphasic approach. Mol. Phyl. and Evol. of Fungi. 2016, 36, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beenken, L.; Gross, A.; Queloz, V. Phylogenetic revision of Petrakia and Seifertia (Melanommataceae, Pleosporales): new and rediscovered species from Europe and North America. Mycol Prog. 2020, 19, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Q.; Wen, Z.H.; Bai, B.; Jing, Z. Q.; Wang, X. W. Botrytis polygoni, a new species of the genus Botrytis infecting Polygonaceae in Gansu, China. Mycologia. 2020, 113, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, P.; Vásquez, G.; Gil-Durán, C.; Oliva, V.; Díaz, A.; Henríquez, M.; et al. Description of the first four species of the genus Pseudogymnoascus from Antarctica. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 713189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y-C. ; Wei, C-L.; Chen, C-Y.; Chen, C-C.; Wu, S-H. Three new species of Cylindrobasidium (Physalacriaceae, Agaricales) from East Asia. Mycol. Prog. 2021, 10, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosa, G.; Zimmermann, B.; Kohler, A.; Ekeberg, D.; Afseth, N. K.; Mounier, J.; et al. High-throughput screening of Mucoromycota fungi for production of low- and high-value lipids. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G. H. S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Sinha, S.; Bandyopadhyay, K. K.; Lawrence, M.; Paul, D. Triauxic growth of an oleaginous red yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides on waste ‘extract’ for enhanced and concomitant lipid and β-carotene production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E. G.; Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranilla, L. G.; Zolla, G.; Afaray-Carazas, A.; Vera-Vega, M.; Huanuqueño, H.; Begazo-Gutiérrez, H.; et al. Integrated metabolite analysis and health-relevant in vitro functionality of white, red, and orange maize (Zea mays L.) from the Peruvian Andean race Cabanita at different maturity stages. Front. nutr. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Na | K | Ca | Mg | P | pH | C/N | %Nt | %OC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | |||||||||

| S1 | 74.4 | 149.3 | 476.4 | 476.4 | 71.4 | 6.5 | 43.7 | 0.1 | 3.0 |

| S3 | 256.2 | 147.8 | 2067.5 | 2067.5 | 125.8 | 6.4 | 20.5 | 0.4 | 7.8 |

| S4 | 254.5 | 138.8 | 757.6 | 757.6 | 274.2 | 6.6 | 26.7 | 0.4 | 9.7 |

| S5 | 180.6 | 136.8 | 4363.4 | 4363.4 | 370.7 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| S6 | 164.2 | 132.6 | 457.1 | 32.8 | 81.2 | 7.5 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| S7 | 194.3 | 153.5 | 974.4 | 54.9 | 26.1 | 7.2 | 54.3 | 0.2 | 11.9 |

| S8 | 300.0 | 145.8 | 1058.3 | 1058.3 | 186.7 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 0.4 | 2.7 |

| S9 | 454.0 | 175.5 | 1152.7 | 1152.7 | 62.4 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 5.8 |

| S10 | 726.2 | 265.2 | 1886.2 | 155.5 | 3.6 | 7.4 | 25.4 | 0.2 | 5.9 |

| S11 | 188.3 | 161.0 | 1354.5 | 71.0 | 31.6 | 7.1 | 15.6 | 0.7 | 11.4 |

| UFRO accesses | Taxonomy |

|---|---|

| UFRO22.77 | Botrytis cinerea |

| UFRO22.262 | Botrytis cinerea |

| UFRO22.551 | Cladosporium herbarum complex herbarum |

| UFRO22.307 | Cladosporium perangustum complex cladosporioides |

| UFRO22.53 | Cladosporium varians complex cladosporioides |

| UFRO22.226 | Cylindrobasidium eucalypti |

| UFRO22.73 | Mortierella antartica |

| UFRO22.40 | Mortierella gamsii |

| UFRO22.317 | Mortierella globulifera |

| UFRO22.261 | Mortierella truficola |

| UFRO22.569 | Penicillium miczynskii |

| UFRO22.251 | Penicillium virgatum |

| UFRO22.138 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum |

| UFRO22.172 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum |

| UFRO22.250 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum |

| UFRO22.358 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum |

| UFRO22.140 | Talaromyces acaricola sect. Islandici |

| UFRO22.418 | Melanommataceae family |

| Bligh & Dyer | Folch | Lewis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | SD | L | X | SD | L | X | SD | L | ||||

| TLE% | 3.83% | ± | 4.25 | b | 8.64% | ± | 8.36 | a | 7.54% | ± | 3.86 | A |

| FAME | 0.89% | ± | 1.11 | c | 1.13% | ± | 1.62 | b | 4.01% | ± | 1.86 | A |

| UFRO accesses | Taxonomy | Bligh & Dyer | Folch | Lewis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFRO22.77 | Botrytis cinerea | 16.46% | 15.87% | 20.70% |

| UFRO22.262 | Botrytis cinerea | 13.92% | 13.18% | 45.73% |

| UFRO22.551 | Cladosporium herbarum complex herbarum | 12.29% | 6.94% | 53.58% |

| UFRO22.307 | Cladosporium perangustum complex cladosporioides | 5.33% | 6.80% | 42.73% |

| UFRO22.53 | Cladosporium varians complex cladosporioides | 11.26% | 9.74% | 50.06% |

| UFRO22.226 | Cylindrobasidium eucalypti | 28.28% | 19.86% | 79.80% |

| UFRO22.73 | Mortierella antartica | 30.68% | 1.25% | 51.93% |

| UFRO22.40 | Mortierella gamsii | 26.65% | 23.42 | 46.76% |

| UFRO22.317 | Mortierella globulifera | 19.58% | 11.30% | 45.71% |

| UFRO22.261 | Mortierella truficola | 11.75% | 18.25% | 60.34% |

| UFRO22.569 | Penicillium miczynskii | 28.62% | 6.52% | 65.85% |

| UFRO22.251 | Penicillium virgatum | 22.24% | 7.90% | 51.01% |

| UFRO22.138 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum | 34.42% | 10.60% | 55.19% |

| UFRO22.172 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum | 18.09% | 2.63% | 74.00% |

| UFRO22.250 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum | 17.88% | 6.41% | 59.59% |

| UFRO22.358 | Pseudogymnoascus pannorum | 15.50% | 13.16% | 51.00% |

| UFRO22.140 | Talaromyces acaricola sect. Islandici | 11.55% | 8.04% | 76.23% |

| UFRO22.418 | Melanommataceae family | 55.30% | 37.86% | 63.70% |

| Fatty acid | Chain length | Time retention (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Lauric acid | C12:0 | 12.008 |

| Myristic acid | C14:0 | 12.790 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | C15:0 | 13.215 |

| Palmitic acid | C16:0 | 13.710 |

| Palmitoleic acid | C16:1 | 14.166 |

| Margaric acid | C17:0 | 14.166 |

| Stearic acid | C18:0 | 14.861 |

| Oleic acid | C18:1 | 15.411 |

| Linoleic acid | C18:2 | 16.262 |

| γ-Linolenic acid | γ-C18:3 | 17.381 |

| α-Linolenic acid | α-C18:3 | 17.381 |

| Behenic acid | C22:0 | 18.201 |

| Dihomo-γ-Linolenic acid | C20:3 | 19.188 |

| Arachidonic acid | C20:4 | 20.096 |

| Lignoceric acid | C24:0 | 21.009 |

| 5,8,11,14,17-Eicosapentaenoic acid | C20:5 | 22.185 |

| Nervonic acid | C24:1 | 22.379 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).