1. Introduction

NASA’s decision to return to the Moon and eventually journey to Mars required a thorough assessment of the potential health risks astronauts may face during long-duration missions. Space Radiation (SR) is one flight hazard that could adversely impact astronaut health [

1]; predicted SR exposure levels for astronauts on missions to Mars may be as much as 1–1.2 Sv (~200 cGy) [

1]. Ground-based rodent studies indicate that exposure to low SR doses (1–25 cGy) impairs performance in various cognitive processes (reviewed in [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]).

The Artemis missions will be particularly challenging due to the high cognitive demands placed on astronauts, who will need to make rapid, critical decisions in unfamiliar or high-pressure situations. Decision-making is a complex process involving the rapid assessment of problems, weighing options, and selecting the most appropriate action after considering potential risks and benefits. It is concerning that exposure to <10 cGy of SR has been shown to significantly impair executive functions related to decision-making, such as attentional set-shifting (ATSET) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], and task-switching [

13,

14]. Executive functions also regulate impulse control and affect, motivation, which if impaired can lead to maladaptive risk behaviors [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Therefore, SR exposure could result in both impaired decision-making and aberrant behaviors, potentially exacerbating issues stemming from challenges like confinement and isolation.

Previous research has shown that female rats exposed to SR exhibit an increased risk-taking propensity (RTP) in a rodent version of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) [

19]. In humans, performance in the BART task correlates with risk propensities in multiple situations [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Like the BART, the RTP task is a free-choice (decision making) test, where rats evaluate the risks and rewards of four available options and estimate the consequences of each [

16,

17]. SR exposure not only led to increased affective behavior, with rats choosing high-risk, well-rewarded options, but also slowed down the decision-making process.

While these rodent RTP data raise concerns about SR’s effects on decision-making, the untrained rats used in the previous study [

19] may not be an appropriate model for astronauts. NASA astronauts, by contrast, are highly trained individuals with superior decision-making skills and inherently low RTP. Furthermore, the rats in the prior study had no experience with the RTP task and had to learn its rules after being exposed to SR. Previous research suggests that SR exposure does not impact performance on tasks with which rats are already familiar [

10], but impairs performance in situations where rats must learn new rules or use transitive inference. Therefore, the increased RTP observed following SR exposure in the cognitively naive rats [

19], might reflect an inability to evaluate or apply the consequences of their choices effectively [

24].

This study was designed to investigate the impact of SR exposure on RTP in male and female rats that were preselected for low RTP prior to exposure. RTP performance was measured before and at 30, 60, and 90 days after exposure to 10 cGy of Galactic Cosmic Ray simulator (GCRsim) radiation, which mimics the primary and secondary GCR fields that human organs will be exposed to on deep-space missions [

25].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Regulatory Compliance

All procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS) and Brookhaven National Laboratories (BNL) were compliant with the National Research Council’s “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th Edition)”.

2.2. Rat Demographics, Husbandry, Experimental Timeline, and Exercise Regimen

Wistar rats (Hla®(WI)CVF®; Hilltop Lab animals, Inc. Scottsdale, PA, USA) were used in this study. Rats were ~ 3 months old upon arrival at EVMS, with an average weight of 250g. The timeline and age of the rats during various experimental procedures relative to the SR exposure are outlined in

Table 1. At the time of SR exposure, the rats were 5-6 months old, which translates to a biological equivalent human age of ~18 years old [

26].

The rats were paired-housed in individually ventilated cages (Green Line Techniplast, Italy) maintained on a reversed 12:12 light/dark cycle and given ad libitum access to Teklad 2014 chow. Rats were implanted with ID-100us RFID transponders (Trovan Ltd, United Kingdom) and maintained on an exercise regimen (30 min at 25 m/min, twice a week) for the entire duration of the study except when the rats were housed at BNL.

2.3. RTP Performance Screening

The RTP test is an appetitive assay and is thus reliant upon the motivational status of the rat to find a food reward. To increase this motivation, rats are placed on food restriction (before and during the testing process) so that an individual rat’s weight was maintained at ~85% of its pre-food restriction weight.

All RTP procedures were conducted in Bussey-Saksida rat touch screen chambers ((Model 80604), Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN). Testing was conducted during the dark cycle with the first rat being tested ~2 h into the 12 h dark cycle (Zeitgeber T+2). The time at which testing was commenced was kept constant for an individual rat.

2.3.1. Stimulus Response Training (STR)

After habituation to the touchscreen chambers, the rats were subjected to Stimulus Response (STR) training which consisted of four stages (Habituation, STR15, STR4 and STR1). In the STR15 stage, the rat gains a food reward by touching any of the 15 illuminated holes (within a 3x5 grid). In the STR4 stage, the rats can gain a food reward by selecting any of the holes within a block of four (2x2) lit holes that is randomly located at one of eight locations. The position of the block is changed after any response (i.e., correct selection of a lit hole or incorrect selection of an unlit hole).

During the STR1-timed stage, rats gain a food reward if they touch a single illuminated hole within 30 s. The location of the illuminated hole is changed after any response (correct or incorrect) to a random location within the grid. In the STR1-fast timed stage, a reward is given if the illuminated light is selected within 10 s of its appearance.

Training sessions occurred daily, with the rats given a maximum of 50 trials/session to reach criterion. Once rats reached criterion in a stage (

Table 2), they proceeded onto the next stage the following day. Rats that did not reach criterion within the permitted number of sessions (

Table 2) were removed from the study.

2.3.2. Risk Taking Propensity (RTP) Task

The RTP task used in this study [

19] differs from an established rodent gambling task [

28] by the introduction of an activation step (the rat must press a green activation light (situated in the middle hole of the 3 x 5 grid)) to activate the RTP task after each trial.

The RTP task utilizes four response lights, that each have a defined a win/loss probability, reward size and loss penalty (

Table 3). Rats have to select a hole within 10 s, failure to do so ends the trial. The rats were given a maximum of five daily sessions (50 trials per session) to reach criterion (i.e., selection of the “safe holes” (#6 or #9) in >66% trials, with a minimum number of 30 trials, in two consecutive sessions).

2.4. Irradiation Procedure

Twenty-four male and 13 female rats satisfied our inclusion criterion and were shipped to BNL. Thirteen male and eight female rats were exposed to 10 cGy “Simplified 5-ion” GCRSim at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory (NSRL), at an overall dose rate of 0.5 cGy/min (~20 min exposure).

After the rats were transported back to EVMS they were rehoused under the same conditions described above. At 30-, 60- and 90- days after irradiation, the rats were placed on a restricted diet for two days and reassessed in the RTP testing, until they reached criterion, or for a maximum of five consecutive days. Following completion of RTP testing the rats were returned to ad libitum rat chow, until the next scheduled assessment.

2.5. Statistical Methods

Data were statistically evaluated using Mann-Whitney U test (two-sided) or Fisher’s Exact test (two-sided). All statistical calculations were performed using the appropriate software program within Prism 10.2 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA).

3. Results

Two rats had to be removed from the study, one female sham rat was euthanized after the 30-day assessment due to an intestinal contortion, and one male GCRsim-exposed rat was lost prior to the 90-day post-exposure assessment due a degloving accident.

3.1. Pre-Exposure (Task Engagement and Learning Proficiency)

The prescreening process identifies rats that are both motivated to perform in the task, and can identify the most profitable hole selection strategy. On average the rats in this study reached criterion within three sessions (males: 2.87 ± 0.31; females: 2.79 ± 0.23). The selected rats were highly motivated to perform, completing >45 (out of a maximum of 64) trials across all the preselection sessions. The frequency that male and female rats selected the best rewarded options was 82.9 ± 1.32% and 77.5 ± 1.85% respectively. There were no significant differences in the learning and motivation status of the rats randomized to the sham or GCR-exposed cohorts in either sex (

Table 4).

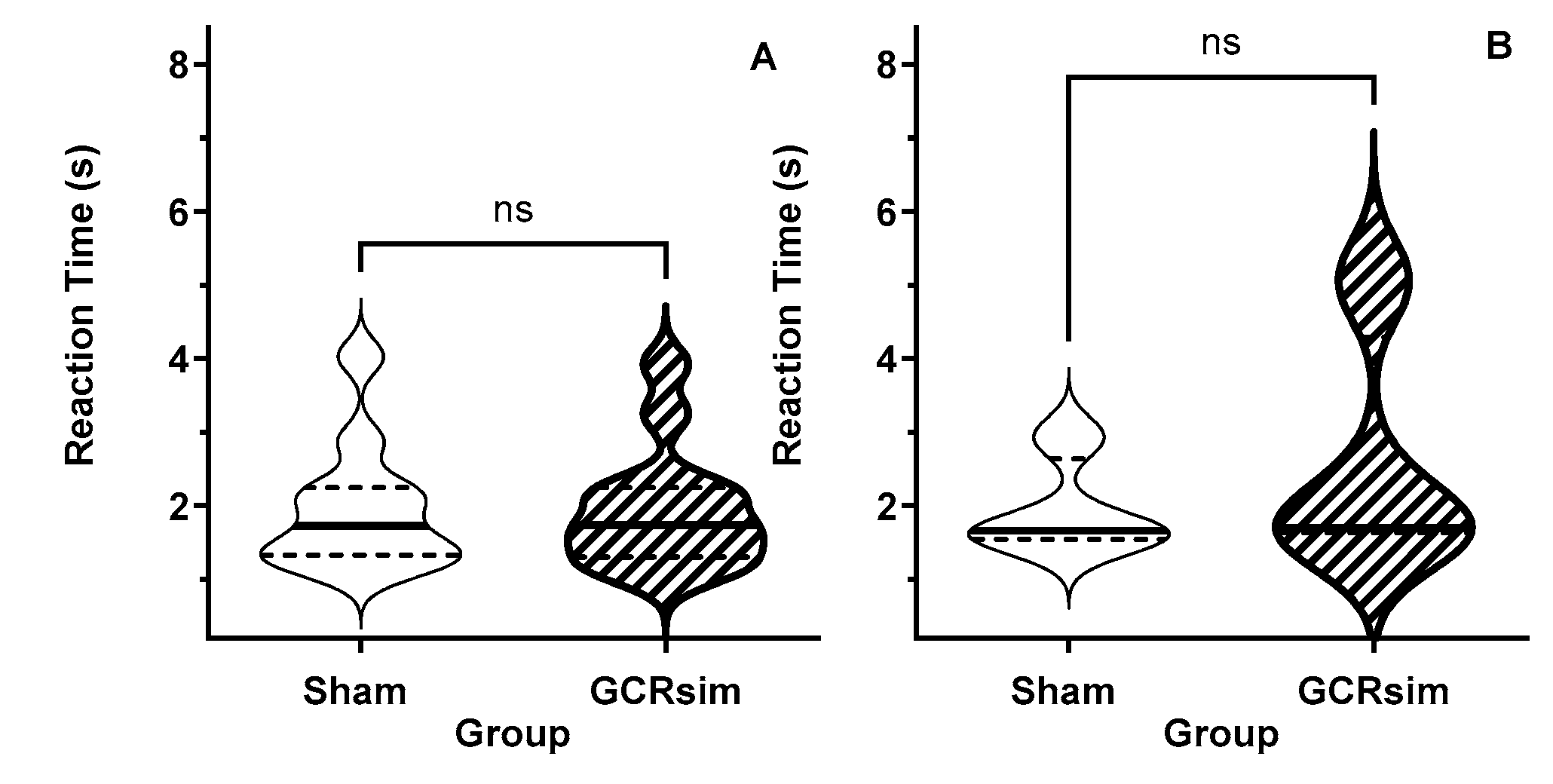

3.2. Pre-Exposure Processing Speed (Reaction Time)

The RTP used in this study requires that the rats actively restart the task after a trial, irrespective of whether the trial resulted in a loss (timeout) or win. Thus the measured reaction times reflect the processing speed of the decision-making process. There were no apparent differences in the time it took the rats to make a response in a trial between the rats assigned to the Sham- or GCRsim-exposed cohorts. (

Figure 1).

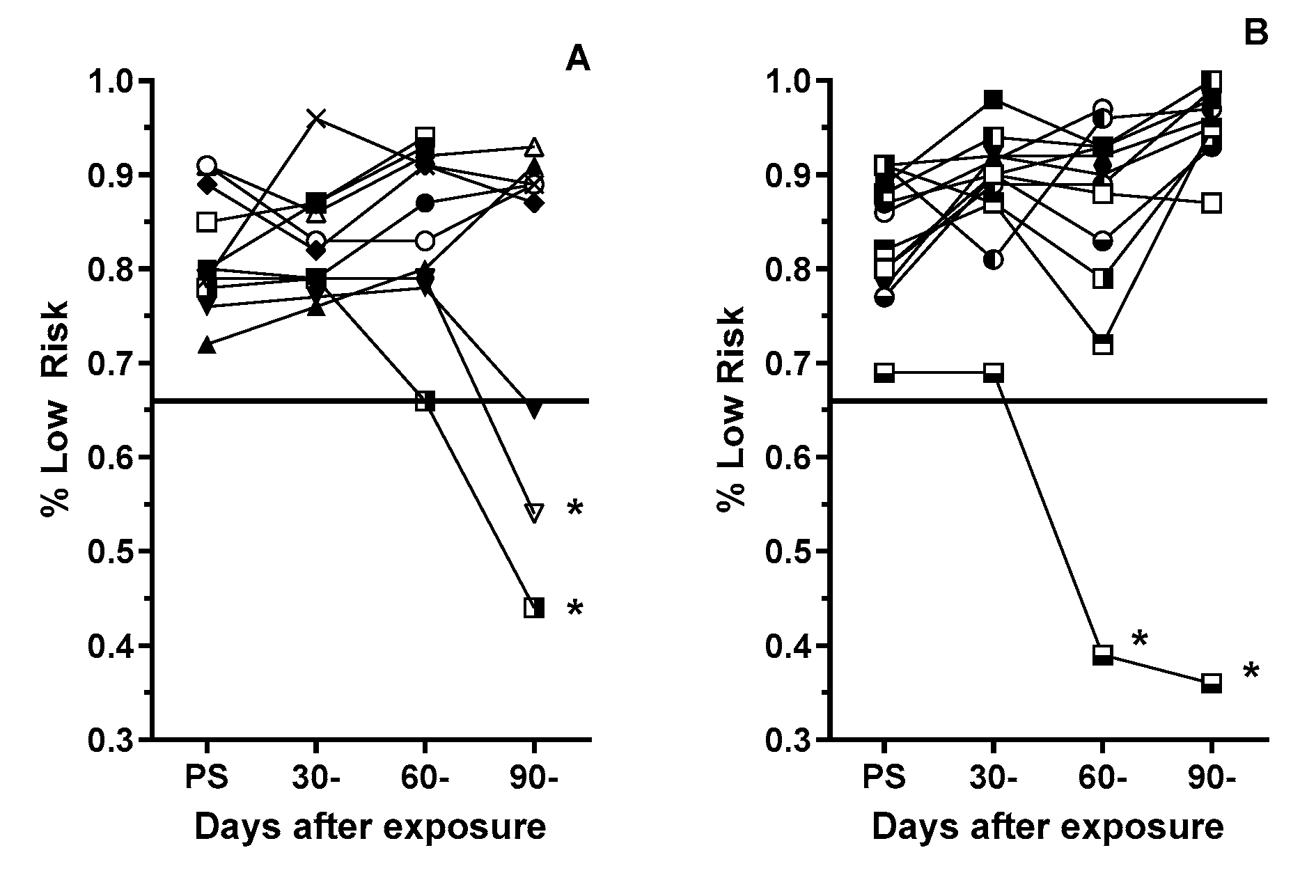

3.3. Post-Exposure Selection Choices

At 30- and 60-days post exposure, there were no significant changes in the hole selection strategy of sham male rats from that used in the prescreening sessions (

Figure 2A). All rats selected one of the low risk/profitable choices in > 65% of the trials. However, at 90 days post exposure (during the third RTP assessment) two of the 11 sham rats selected the riskier options (holes 7 and 10) at a significantly (P< 0.003, Fisher’ Exact) higher rate than they did previously.

Overall, the GCR-exposed rats did not exhibit any significant change in the hole selection strategy over the 90-day testing period. However, a single rat selected the higher risk choices at a significantly (P< 0.001, Fisher’ Exact) higher frequency (>60% of the trials) during both the 60- and 90-day assessments (

Figure 2B).

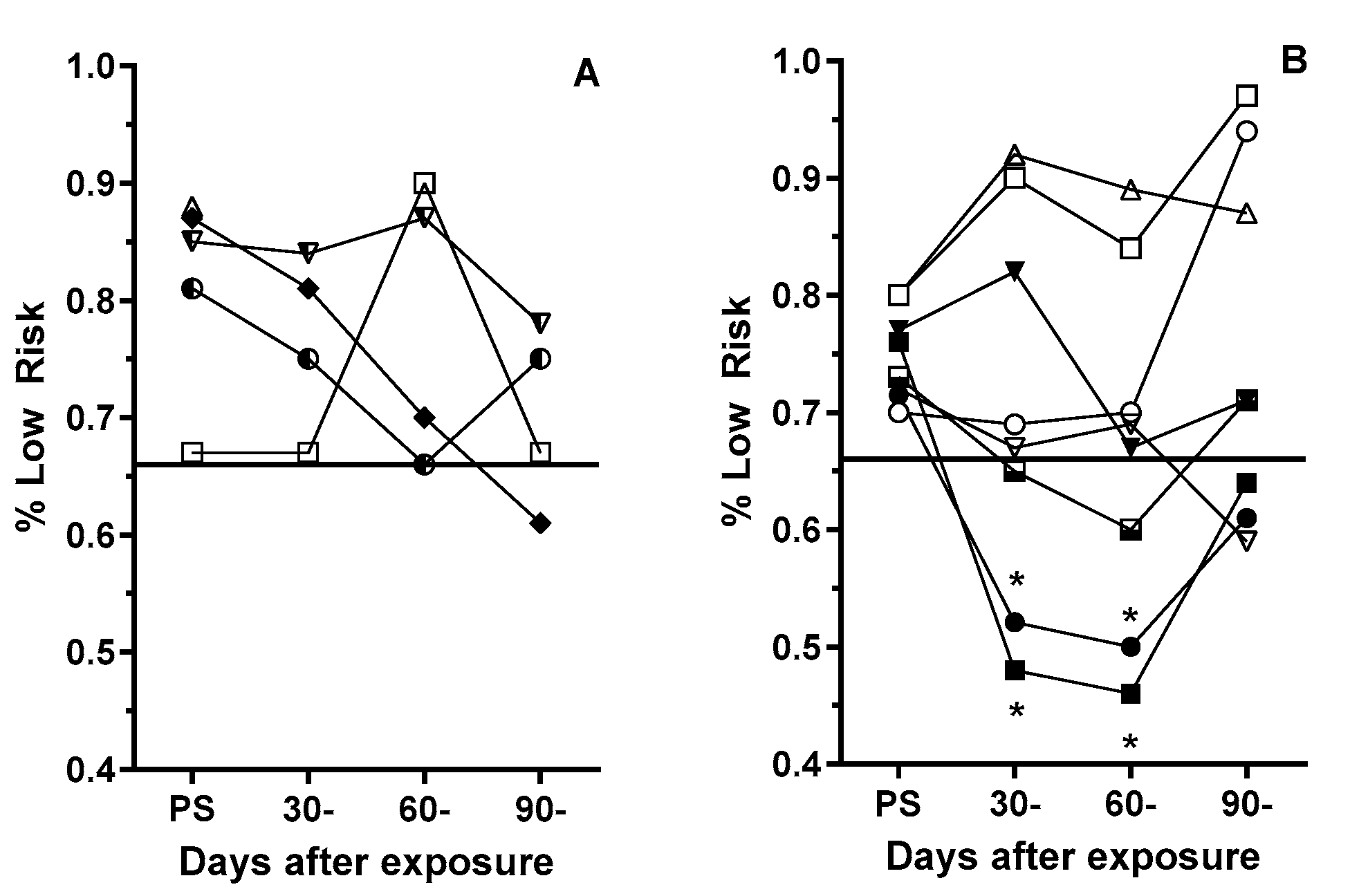

Overall, the hole selection strategy of the sham female rats remained above the pre-exposure performance threshold of ≥66% of low-risk choices (

Figure 3A). However, three of the eight GCRsim-exposed female rats had selections rates below that threshold (

Figure 3B). At 30- and 60-days post exposure two rats (25%) selected the higher risk options at an equal or higher rate than they did the profitable options, which was significantly (P< 0.01, Fisher’ Exact) lower than the threshold rate. However, during the 90-day post exposure (the third) assessment, the safe hole selection rate was close to the prescreening threshold level.

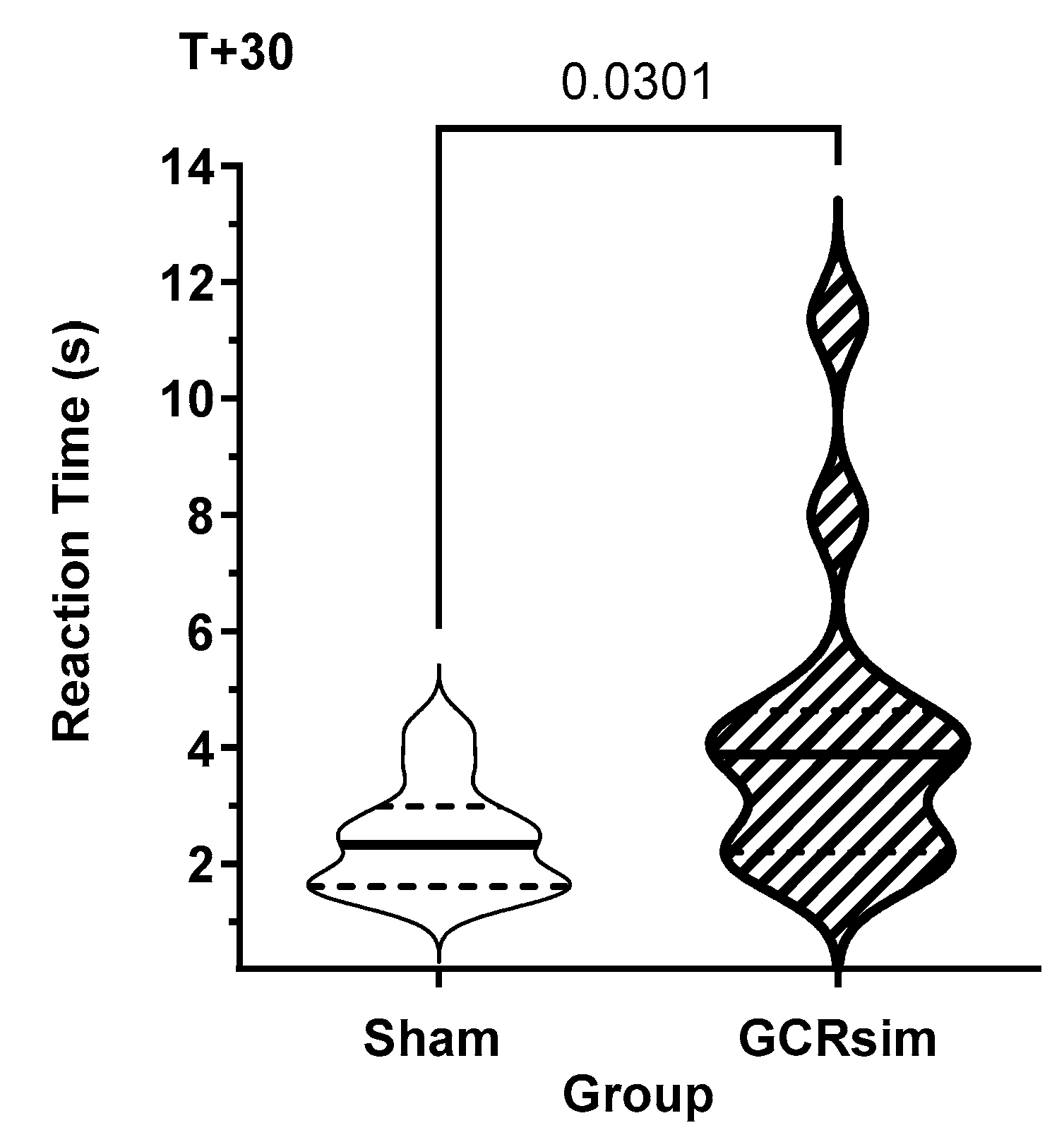

3.4. Post-Exposure Processing Speed

An analysis of the response time data from the first day of the 30-day post-assessment provides a measure of the inherent impact of SR on processing speed; subsequent assessments will be a net result of processing speed loss, possibly offset by practice effects. GCR-exposed male rats had significantly longer (Shams: 2.43 ±0.28 s; GCR: 4.38 ±0.74 s; P=0.03, Mann-Whitney) response times than Shams (

Figure 4). Due to the requirement that that rats had to actively restart the test (after either a win or a loss), this increased response time was not a manifestation of motivation of the rats to participate in the task.

A similar analysis of response time/processing speed in the female rats did not reveal any significant differences in processing speed in sham or GCR-exposed rats (data not shown).

4. Discussion

While all space flight hazards pose a potential problem to the long-term health of astronauts, the deleterious effects of SR are the least characterized. Ground based rodent studies suggest that SR exposure has a significant impact upon several cognitive processes and behaviors. The present study has extended the range of processes impacted by SR to include decision-making/RTP.

In both male and female rats exposure to 10 cGy GCRsim resulted in significant impairments in decision making in the RTP task. Within 30 days of SR exposure both male and female rats had altered performance in the RTP. In female rats this was manifested as 25% of rats making less profitable decisions than they did prior to SR exposure. In contrast, SR exposed male rats generally maintained the same low-risk selection rate but took significantly (~2-fold) longer to select than did the shams. There is an ever-growing number of studies that report different sex-dependent cognitive outcomes after SR exposure [

7,

8,

13,

14,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], and presently it would appear that the ultimate outcome of SR exposure in male and female rodents is highly dependent upon the cognitive domains being investigated.

The increased RTP of the GCR-exposed female rats (

Figure 3) is consistent with our previous studies with He-exposed rats [

19]. However, in those earlier studies, the increased RTP could have been attributed to SR impacting rule learning, as the rats had no prior experience with the RTP assay. In contrast, the present study involved rats that were not only familiar with the RTP assay but had also identified the most effective hole selection strategy. Thus, the SR-induced increase in RTP seen in the current study (

Figure 3) suggests that SR exposure impacts some aspects of decision making/evaluation process or possibly their long-term-working memory of the task. Although only 25–33% of the female rats showed impaired performance, this proportion approaches the threshold generally recognized as sufficient to compromise the combat effectiveness of a unit [

38].

While the BART is generally considered to be a valid measure to assess RTP in humans, without additional independent measures of “real life” risk taking in rats it is dangerous to speculate whether the observed SR-changes in RTP in female rats reflects a change in risk taking. Specific experiments designed to establish the relationship with decision making performance and “reckless” behavior are needed before such assumptions can be made. However, our data do suggest that SR does impact some aspect of decision making in female rats. We have previously shown that GCRsim exposure impacts ATSET performance, a critical component of decision making. Moreover, this study suggests that SR adversely affects numerosity (and possibly abstraction) since performance in the RTP requires that rats establish the probabilities and risks associated with the four presented options and estimating the consequences of each option. Rats have well developed numerosity, abstraction and metacognitive abilities [

39,

40]. However, specific experiments using the tasks employed in those studies will be required to establish the incidence and severity of SR-induced losses in those cognitive domains.

Whatever the reasons underlying these decision-making performance changes in irradiated female rats, it does seem reversible, since by 90 days post exposure (i.e., during the third post exposure testing), the RTP performance decrements were no longer considered significant. Thus, the female rats appear to have either “passively” (e.g., regained their long-term working memory of the optimum reward strategy) or “actively” (relearned/reevaluated the profitability of the various section strategies) reversed the performance decrements.

In contrast, most male rats did not exhibit any alteration in decision making strategy after GCR-exposure. However, during the first RTP assessment (at 30 days after exposure), there was a highly significant increase in the time the rats took to make a selection (

Figure 3). While most of the rats continued to make “profitable” selections during the 90-day (three test) period, one rat abandoned the profitable selection approach at 60- and 90-days and selected the high-risk options in over 70% of trials. However, this may not be related to SR exposure, since some sham rats adopted similar changes in selection strategy in the third post-exposure test, possibly due to boredom in the task.

The male data provides further evidence that SR exposure impacts processing speeds in complex tasks, like ATSET [

7,

8,

41] and task switching [

14]. The underlying cause for the SR-induced loss of processing speed is presently unclear, but is often observed in patients receiving cranial X-ray or proton therapy [

42,

43]. SR exposure results in task switching costs [

14], a phenomenon negatively correlated with processing speed [

44,

45]. Processing speed can be a reflection of working memory [

46,

47,

48,

49], which is also impaired by SR exposure [

3,

4,

5,

50]. Processing speed is also impacted by neuronal myelination levels [

51,

52], which are significantly altered by SR exposure in mice [

53].

5. Conclusions

In summary, our studies reaffirm that SR exposure affects cognitive performance in both male and female rats, though the nature of these impairments is highly context specific. These findings are particularly concerning as they indicate that SR exposure can alter RTP predisposition in rats that previously demonstrated a working knowledge of the task and a low predisposition for risk-taking. Translating ground-based rodent studies into tangible risk estimates for astronauts remains an enormous challenge, but our data raise the possibility that astronauts may need to be closely monitored for alterations on decision-making/risk taking behavior and/or loss of processing speed during cognitive loading. To mitigate these potential risks, it may be prudent for NASA to enhance training programs to ensure astronauts can effectively perform critical tasks and make sound decisions even if their executive functions are compromised by SR exposure. Training scenarios that simulate high-risk, high-pressure situations with limited decision-making time could help astronauts prepare to respond more effectively under cognitive stress.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this study. Elliot Smits: Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Formal Analysis; Faith Reid: Software; Ella Tamgue: Resources, Formal Analysis, Investigation; Paola Alvarado Arriaga: Resources, Formal Analysis, Investigation; Charles Nguyen: Formal Analysis; Richard A Britten: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a NASA-HRP IWS Student (ES, and FR) supplemental award to NASA grant NNX14AE73G.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding agency had no role in the generations of the concepts contained within this design of the study. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and not those of the funding agency or host institutes.

References

- G. A. Nelson, Space Radiation and Human Exposures, A Primer. Radiat. Res. 2016, 185, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Britten, L.L. Wellman, L.D. Sanford, Progressive increase in the complexity and translatability of rodent testing to assess space-radiation induced cognitive impairment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 126, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Cekanaviciute, S. Rosi, S. V. Costes, Central nervous system responses to simulated galactic cosmic rays. Int. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Cucinotta, E. Cacao, Risks of cognitive detriments after low dose heavy ion and proton exposures. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2019, 95, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F. Kiffer, M. Boerma, A. Allen, Behavioral effects of space radiation: A comprehensive review of animal studies. Life Sci. Sp. Res. 2019, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.W. Whoolery, S. Yun, R.P. Reynolds, M.J. Lucero, I. Soler, F.H. Tran, N. Ito, R.L. Redfield, D.R. Richardson, H. ying Shih, P.D. Rivera, B.P.C. Chen, S.G. Birnbaum, A.M. Stowe, A.J. Eisch, Multi-domain cognitive assessment of male mice reveals whole body exposure to space radiation is not detrimental to high-level cognition and actually improves pattern separation, BioRxiv. (2019). [CrossRef]

- R. A. Britten, A. Fesshaye, A. Tidmore, A.A. Blackwell, Similar Loss of Executive Function Performance after Exposure to Low (10 cGy) Doses of Single (4He) Ions and the Multi-Ion GCRSim Beam. Radiat. Res. 2022, 198, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A. Britten, A. Fesshaye, A. Tidmore, A. Liu, A.A. Blackwell, Loss of Cognitive Flexibility Practice Effects in Female Rats Exposed to Simulated Space Radiation. Radiat. Res. 2023, 200, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.K. Parihar, B.D. Allen, C. Caressi, S. Kwok, E. Chu, K.K. Tran, N.N. Chmielewski, E. Giedzinski, M.M. Acharya, R.A. Britten, J.E. Baulch, C.L. Limoli, Cosmic radiation exposure and persistent cognitive dysfunction. Sci. Rep. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Jewell, V.D. Duncan, A. Fesshaye, A. Tondin, E. Macadat, R.A. Britten, Exposure to ≤15 cgy of 600 mev/n 56 fe particles impairs rule acquisition but not long-term memory in the attentional set-shifting assay. Radiat. Res. 2018, 190, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. A. Britten, A.S. Fesshaye, V.D. Duncan, L.L. Wellman, L.D. Sanford, Sleep Fragmentation Exacerbates Executive Function Impairments Induced by Low Doses of Si Ions. Radiat. Res. 2020, 194, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. A. Burket, M. Matar, A. Fesshaye, J.C. Pickle, R.A. Britten, Exposure to Low (≤10 cGy) Doses of 4He Particles Leads to Increased Social Withdrawal and Loss of Executive Function Performance. Radiat. Res. 2021, 196, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Stephenson, A. Liu, A.A. Blackwell, R.A. Britten, Multiple decrements in switch task performance in female rats exposed to space radiation. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 449, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Stephenson, R. Britten, Simulated Space Radiation Exposure Effects on Switch Task Performance in Rats. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2022, 93, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechara, E.M. Martin, Impaired decision making related to working memory deficits in individuals with substance addictions. Neuropsychology. 2004, 18, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Brand, E. Kalbe, K. Labudda, E. Fujiwara, J. Kessler, H.J. Markowitsch, Decision-making impairments in patients with pathological gambling. Psychiatry Res. 2005, 133, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Romer, L. Betancourt, J.M. Giannetta, N.L. Brodsky, M. Farah, H. Hurt, Executive cognitive functions and impulsivity as correlates of risk taking and problem behavior in preadolescents. Neuropsychologia. 2009, 47, 2916–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. J. Smith, D.J. Cobia, L. Wang, K.I. Alpert, W.J. Cronenwett, M.B. Goldman, D. Mamah, D.M. Barch, H.C. Breiter, J.G. Csernansky, Cannabis-related working memory deficits and associated subcortical morphological differences in healthy individuals and schizophrenia subjects. Schizophr. Bull. 2014, 40, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Li, S. Phuyal, E. Smits, F.E. Reid, E.N. Tamgue, P.A. Arriaga, R.A. Britten, Exposure to low (10 cGy) doses of (4)He ions leads to an apparent increase in risk taking propensity in female rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 474, 115182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. W. Lejuez, J.P. Read, C.W. Kahler, J.B. Richards, S.E. Ramsey, G.L. Stuart, D.R. Strong, R.A. Brown, Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2002, 8, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. K. Hunt, D.R. Hopko, R. Bare, C.W. Lejuez, E. V Robinson, Construct validity of the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART): associations with psychopathy and impulsivity. Assessment. 2005, 12, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. W. Lejuez, W.M. Aklin, H.A. Jones, J.B. Richards, D.R. Strong, C.W. Kahler, J.P. Read, The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) differentiates smokers and nonsmokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 11, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. W. Lejuez, W.M. Aklin, M.J. Zvolensky, C.M. Pedulla, Evaluation of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) as a predictor of adolescent real-world risk-taking behaviours. J. Adolesc. 2003, 26, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.D. Pickering, J.A. Gray, Advances in Research on Temperament, (2001).

- T. C. Slaba, S.R. Blattnig, J.W. Norbury, A. Rusek, C. La Tessa, Reference field specification and preliminary beam selection strategy for accelerator-based GCR simulation. Life Sci. Sp. Res. 2016, 8, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. A. Andreollo, E.F. dos Santos, M.R. de Araujo, L.R. Lopes, Rat’s age versus human’s age: what is the relationship? Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2012, 1, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- No Title, Washington (DC), 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Barrus, C.A. Winstanley, Dopamine D3 Receptors Modulate the Ability of Win-Paired Cues to Increase Risky Choice in a Rat Gambling Task. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. La Tessa, M. Sivertz, I.H. Chiang, D. Lowenstein, A. Rusek, Overview of the NASA space radiation laboratory. Life Sci. Sp. Res. 2016, 11, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Alaghband, P.M. Klein, E.A. Kramár, M.N. Cranston, B.C. Perry, L.M. Shelerud, A.E. Kane, N.-L. Doan, N. Ru, M.M. Acharya, M.A. Wood, D.A. Sinclair, D.L. Dickstein, I. Soltesz, C.L. Limoli, J.E. Baulch, Galactic cosmic radiation exposure causes multifaceted neurocognitive impairments. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. E. Villasana, T.S. Benice, J. Raber, Long-term effects of 56Fe irradiation on spatial memory of mice: role of sex and apolipoprotein E isoform. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 80, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Villasana, J. Rosenberg, J. Raber, Sex-dependent effects of 56Fe irradiation on contextual fear conditioning in C57BL/6J mice. Hippocampus. 2010, 20, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Krukowski, K. Grue, E.S. Frias, J. Pietrykowski, T. Jones, G. Nelson, S. Rosi, Female mice are protected from space radiation-induced maladaptive responses. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2018, 74, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F. Kiffer, T. Alexander, J.E. Anderson, T. Groves, J. Wang, V. Sridharan, M. Boerma, A.R. Allen, Late effects of 16 O-particle radiation on female social and cognitive behavior and hippocampal physiology. Radiat. Res. 2019, 191, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V.K. Parihar, M.C. Angulo, B.D. Allen, A. Syage, M.T. Usmani, E. Passerat de la Chapelle, A.N. Amin, L. Flores, X. Lin, E. Giedzinski, C.L. Limoli, Sex-Specific Cognitive Deficits Following Space Radiation Exposure. Front. B, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Hinkle, J.A. Olschowka, T.M. Love, J.P. Williams, M.K. O’Banion, Cranial irradiation mediated spine loss is sex-specific and complement receptor-3 dependent in male mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Liu, R.G. Hinshaw, K.X. Le, M.-A. Park, S. Wang, A.P. Belanger, S. Dubey, J.L. Frost, Q. Shi, P. Holton, L. Trojanczyk, V. Reiser, P.A. Jones, W. Trigg, M.F. Di Carli, P. Lorello, B.J. Caldarone, J.P. Williams, M.K. O’Banion, C.A. Lemere, Space-like (56)Fe irradiation manifests mild, early sex-specific behavioral and neuropathological changes in wildtype and Alzheimer’s-like transgenic mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D.K. Clark, Casualties as a measure of the loss of combat effectiveness of an infantry battalion, Operations Research Office, Johns Hopkins University, 1954.

- A. Kepecs, N. Uchida, H.A. Zariwala, Z.F. Mainen, Neural correlates, computation and behavioural impact of decision confidence. Nature. 2008, 455, 227–231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. D. Muller, S.B. Fountain, Concurrent cognitive processes in rat serial pattern learning: Item memory, serial position, and pattern structure. Learn. Motiv. 2010, 41, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H.H.V. Chang, A.S. Fesshaye, A. Tidmore, L.D. Sanford, R.A. Britten, Sleep Fragmentation Results in Novel Set-shifting Decrements in GCR-exposed Male and Female Rats. Radiat. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Kahalley, R. Peterson, M.D. Ris, L. Janzen, M.F. Okcu, D.R. Grosshans, V. Ramaswamy, A.C. Paulino, D. Hodgson, A. Mahajan, D.S. Tsang, N. Laperriere, W.E. Whitehead, R.C. Dauser, M.D. Taylor, H.M. Conklin, M. Chintagumpala, E. Bouffet, D. Mabbott, Superior Intellectual Outcomes After Proton Radiotherapy Compared With Photon Radiotherapy for Pediatric Medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. -P. Huynh-Le, M.D. Tibbs, R. Karunamuni, M. Salans, K.R. Tringale, A. Yip, M. Connor, A.B. Simon, L.K. Vitzthum, A. Reyes, A.C. Macari, V. Moiseenko, C.R. McDonald, J.A. Hattangadi-Gluth, Microstructural Injury to Corpus Callosum and Intrahemispheric White Matter Tracts Correlate With Attention and Processing Speed Decline After Brain Radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 110, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Moretti, C. Semenza, A. Vallesi, General Slowing and Education Mediate Task Switching Performance Across the Life-Span. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. A. Salthouse, N. Fristoe, K.E. McGuthry, D.Z. Hambrick, Relation of task switching to speed, age, and fluid intelligence. Psychol. Aging. 1998, 13, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. A. Jacobson, M. Ryan, R.B. Martin, J. Ewen, S.H. Mostofsky, M.B. Denckla, E.M. Mahone, Working memory influences processing speed and reading fluency in ADHD. Child Neuropsychol. a J. Norm. Abnorm. Dev. Child. Adolesc. 2011, 17, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Shaw, K. Eckstrand, W. Sharp, J. Blumenthal, J.P. Lerch, D. Greenstein, L. Clasen, A. Evans, J. Giedd, J.L. Rapoport, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 19649–19654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Shaw, W.S. Sharp, M. Morrison, K. Eckstrand, D.K. Greenstein, L.S. Clasen, A.C. Evans, J.L. Rapoport, Psychostimulant treatment and the developing cortex in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009, 166, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Shaw, F. Lalonde, C. Lepage, C. Rabin, K. Eckstrand, W. Sharp, D. Greenstein, A. Evans, J.N. Giedd, J. Rapoport, Development of cortical asymmetry in typically developing children and its disruption in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009, 66, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Soler, S. Yun, R.P. Reynolds, C.W. Whoolery, F.H. Tran, P.L. Kumar, Y. Rong, M.J. DeSalle, A.D. Gibson, A.M. Stowe, F.C. Kiffer, A.J. Eisch, Multi-Domain Touchscreen-Based Cognitive Assessment of C57BL/6J Female Mice Shows Whole-Body Exposure to (56)Fe Particle Space Radiation in Maturity Improves Discrimination Learning Yet Impairs Stimulus-Response Rule-Based Habit Learning. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 722780. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Lu, G.J. Lee, E.P. Raven, K. Tingus, T. Khoo, P.M. Thompson, G. Bartzokis, Age-related slowing in cognitive processing speed is associated with myelin integrity in a very healthy elderly sample. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2011, 33, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. H. Lu, G.J. Lee, T.A. Tishler, M. Meghpara, P.M. Thompson, G. Bartzokis, Myelin breakdown mediates age-related slowing in cognitive processing speed in healthy elderly men. Brain Cogn. 2013, 81, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. L. Dickstein, R. Talty, E. Bresnahan, M. Varghese, B. Perry, W.G.M. Janssen, A. Sowa, E. Giedzinski, L. Apodaca, J. Baulch, M. Acharya, V. Parihar, C.L. Limoli, Alterations in synaptic density and myelination in response to exposure to high-energy charged particles. J. Comp. Neurol. 2018, 526, 2845–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).