1. Introduction

The agrifood sector is essential for meeting global food needs and supporting rural livelihoods, but it now faces significant challenges due to climate change. Extreme weather and shifting seasons adversely affect agricultural production and farmers' incomes, particularly for small-scale producers who are especially vulnerable due to limited resources and infrastructure. To ensure the sector's long-term viability, it is crucial to address climate change by implementing strategies that mitigate its impacts. Enhancing resilience, reducing production risks, and improving incomes can be achieved through climate-smart innovations and sustainable practices, utilizing advancements in technology and precision agriculture to foster economic prosperity in the agrifood sector (CSA - Climate-smart Agriculture) [

1].

Technology plays a crucial role in modern agriculture, particularly as the global population is projected to exceed nine billion by 2050, necessitating a quick and safe increase in food production. Farmers aim to optimize their operations for cost and efficiency while facing challenges such as climate variability, which affects production and environmental conditions. Effective monitoring of environmental variables is essential for informed decision-making regarding agricultural practices like irrigation and harvest timing [

2,

3].

Smart Farming (SF) is highlighted as a promising solution, defined as the application of information and communication technologies to enhance agricultural productivity through spatial analysis of production characteristics. SF aims to streamline production processes while improving efficiency and safety. Various studies have proposed frameworks and platforms, such as IoT-enabled ecological monitoring and cloud-based services, to enhance agricultural practices. However, existing research often lacks comprehensive guidance on selecting the most suitable IoT technologies and managing infrastructure for crop management [

4,

5,

6].

The advancements in agriculture have brought about significant changes and improvements through the use of cutting-edge technologies. Smart technologies, including artificial intelligence, robotics, and the Internet of Things, are instrumental in boosting productivity and efficiency in farming practices [

7,

8].

Agriculture 4.0 is the fourth revolution in agriculture that utilizes digital technologies to create a more intelligent, efficient, and environmentally friendly sector. Innovations in agricultural technology have been developed to improve sustainability and optimize farming practices. This includes the integration of digitalization and automation processes, such as Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics, the Internet of Things (IoT), and virtual and augmented reality, into both business operations and everyday life.

The introduction of smart farming and precision agriculture revolutionized the agricultural sector by automating farming processes to increase both the quantity and quality of crop yield for food sustainability [

9].

Precision agriculture, also known as smart farming, has the potential to greatly enhance agricultural production in terms of both productivity and sustainability. While productivity has traditionally been the main focus of technological advancements in agriculture, the importance of sustainability cannot be overlooked. Smart agriculture aims to minimize the environmental impact of farming activities in response to the growing concern for sustainability in all aspects of human life [

10,

11].

Smart farming builds upon the foundation of precision agriculture, expanding beyond in-field management tasks to encompass a broader ecosystem. This includes incorporating new technologies such as cloud computing, Internet of Things (IoT), Geographic Information System (GIS), and utilizing data from various sources such as descriptive, vector, and remote sensing [

12].

Smart farming involves the use of technologies and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to manage farms and improve crop yield. Drones and IoT sensors are examples of tools used in smart farming to autonomously manage farms. Precision agriculture is an approach to the agricultural revolution that focuses on determining the optimal timing, location, and application of resources for maximum crop yield. The first and second agricultural revolutions were Agricultural Mechanization (using tools/machines) and the Green Revolution (improving crop seeds and animal breeds). While smart farming and precision agriculture are related concepts aimed at enhancing crop yield, they are not identical. These technologies have emerged as valuable tools for bridging the knowledge gap and improving agricultural production. The digitization of agriculture can be attributed to John Deere in 1990 when intelligent tools allowed for precision planting and fertilizer application. The primary goal of these innovative approaches is to increase agricultural production and support sustainable farming practices. In smart farming, data on soil parameters, required fertilisers, and weather conditions are collected and analyzed to optimize crop performance. Models are developed to autonomously manage farming resources based on this information. Smart farming and precision agriculture are particularly important in regions like Sicily, where traditional agricultural practices are prevalent, as they can significantly improve crop yield and overall farming efficiency [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The application of Internet of Things (IoT) technology in agriculture has revolutionized traditional farming practices in recent years, enhancing sustainability, productivity, and efficiency. This article focuses on the implementation of IoT-based intelligence systems specifically designed for agricultural applications, with an emphasis on solar drying processes. This dryer prototype collect real-time data on various environmental factors such as solar radiation intensity, temperature, humidity, and soil moisture levels.

Currently, there is a rising interest among consumers in medicinal and aromatic herbs. The quality of nutraceutical and aromatic plants from a microbiological standpoint is crucial for customers. Italian producers follow strict hygiene regulations to reduce the bacterial presence in these plants, especially focusing on the drying process between harvest and packaging [

19,

20,

21].

This drying process involves the use of devices with a heat pump, drying the products at temperatures between 20 and 50 °C with very dry air to maintain their color, aroma, and chemical composition. The aim of this study is optimizing the drying process using a dryer plant in Grotte, Italy, powered by a photovoltaic Renewable Energy Source (RES) [

22,

23,

24,

25] for nutraceutical and aromatic species like rosemary and sage. The energy for the dryer is generated by photovoltaic panels on the roof and facades of the structure, allowing on-site energy exchange and self-consumption. Real-time monitoring of the drying process enables through sensors sending data via Wi-Fi to a ThingSpeak account. The system helps in decision-making during the drying process by accurately monitoring moisture loss and drying rates for the herbs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Site

The study site is located in the inland area of southern Sicily, specifically in Grotte (37.381770° N, 13.673952° E) in the province of Agrigento, near the Morreale company. The land is situated at an altitude of about 400 meters above sea level. According to Köppen's classification, the area is characterized by a Hot temperate climate (Csa). The moisture regime of the soils is xeric, bordering on aridic, and the thermal temperature regime is also noted.

The Morreale farm’s primarily specializes in growing aromatic and nutraceutical plants, including Oregano (

Origanum vulgare L.), Rosemary (

Salvia rosmarinus Spenn.), Sage (

Salvia officinalis L.), Thyme (

Thymus vulgaris L.), and Lavender (

Lavandula angustifolia L.). A notable innovation on the farm is the cultivation of

Moringa oleifera Lam., an emerging superfood [

26]. This farm operates as an environmentally friendly, multifunctional establishment dedicated to soil preservation in Sicily [

27].

2.2. Field Data Collection

The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) has been increasing in tasks such as crop management, estimating biomass, predicting yields, and monitoring plant health. UAV imagery can be used to analyse surface models, evaluate crop height and growth rate, and extract canopy temperature and digital plant counting. This data can be used as a reference parameter for implementing spatially variable crop operations using a Decision Support System (DSS), enabling farmers to choose the right time to harvest crops such as rosemary for food and essential oil extraction.

Overall, these technological advancements can provide rapid and on-demand real-time data for smart agriculture practices, benefiting farmers and businesses in the agricultural sector [

28].

The flight mission involved the strategic planning of parameters through DJI GS Pro software (

Table 1). These parameters encompassed various aspects such as height, speed, direction, and the acquisition details of the cameras, including the sequence of shots and the frontal and lateral overlapping.

To mitigate potential disruptions like shadows and weeds, the flight was meticulously executed at noon, when the sun was positioned at the zenith. Prior to the flight, the entire plot underwent harrowing, and four ground control points (GCPs) were strategically positioned in the field. These GCPs were georeferenced using the GNSS receiver S7-G by Stonex, (Milan, Italy), equipped with a Stonex geodetic antenna. This receiver utilized multiband signals from prominent GNSS satellites, including GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and Bei Dou. Enhanced accuracy was achieved through Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) differential correction data.

The coordinates of the GCPs were acquired in RTK mode, averaging 60 measurements. Subsequently, under favorable weather conditions characterized by clear skies and low wind speed, the flight commenced along the predefined route and waypoints.

2.3. Spectral Vegetation Indices

Remote sensing techniques have demonstrated their effectiveness across a range of agricultural applications, such as crop classification, yield prediction, and monitoring plant health and nutrient deficiencies. There is a growing emphasis on precision farming and smart agricultural resource management systems aimed at enhancing productivity, profitability, and environmental sustainability.

This technology plays a critical role in sustainable farming practices, allowing farmers to assess soil and crop health at key growth stages. Early evaluations help optimize fertilizer application, while later assessments support health evaluations and yield predictions. Remote sensors deliver timely data on biophysical indicators and their spatial variations, enabling variable rate technology that customizes fertilizer usage according to specific conditions. Among the essential nutrients, nitrogen is particularly crucial for crop growth, as it affects chlorophyll content and photosynthesis. However, excessive nitrogen can lead to runoff and aquatic pollution, while inadequate levels can diminish crop yields and result in financial losses.

To tackle these challenges, accurately assessing nitrogen levels in fields is essential, particularly during the early stages of crop growth. Remote sensing of vegetation utilizes passive sensors to capture electromagnetic reflectance from plant canopies, with reflectance characteristics varying based on plant type and water content. Healthy plants typically exhibit high reflectance, whereas dry plants display lower reflectance values.

Vegetation indices obtained from reflectance data can be used to evaluate various plant characteristics, such as water content and stress levels, thereby enhancing our understanding of plant dynamics. However, interpreting remote sensing data can be complex and is often constrained by the reliance on a limited number of spectral bands. Despite these difficulties, researchers are developing advanced algorithms and techniques for assessing plant health, showing that even basic vegetation index algorithms can be effective tools for monitoring agricultural health [

29].

Remote sensing methods have proven to be valuable for assessing nitrogen status and crop health. Research shows that nitrogen deficiency leads to a decrease in leaf chlorophyll content, which increases transmittance at visible wavelengths and alters the reflectance of crop leaves. These alterations enable the estimation of chlorophyll concentration and nitrogen variability.

As a result, the optical indices employed to estimate chlorophyll levels are affected not only by these additional factors but also by the reflectance of the soil. Recent studies have increasingly concentrated on the connection between the optical properties of vegetation and the concentrations of photosynthetic pigments, especially chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, and carotenoids. These pigments display unique spectral characteristics, with specific absorption features at different wavelengths, which allows remote sensing techniques to assess their effects on vegetation reflectance [

30].

This has resulted in the creation of numerous approaches, both empirical and model-based, for estimating chlorophyll content at both the leaf and canopy levels [

31,

32].

Research has largely focused on employing optical indices to enhance sensitivity to chlorophyll content while minimizing variability from other influences. This has involved assessing reflectance in narrow spectral bands, utilizing band ratios, and analyzing the characteristics of derivative spectra. Important spectral regions for chlorophyll analysis include approximately 680 nm, which is associated with chlorophyll-a absorption, and 550 nm, where chlorophyll absorption is minimal. The existing literature offers thorough discussions on the most effective wavelengths and chlorophyll indices [

33].

A notable index is the Modified Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index (MCARI) [

34], which is an enhancement of the original Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index (CARI) [

35].

CARI seeks to address the variability in photosynthetically active radiation attributed to non-photosynthetic materials by employing reflectance data from certain wavelengths, specifically 550 nm, 670 nm (the absorption peak for chlorophyll-a), and 700 nm (the transition point between pigment absorption and structural effects). MCARI quantifies chlorophyll absorption depth at 670 nm in relation to reflectance at 550 nm and 700 nm through a defined equation.

Although MCARI is effective, it is sensitive to background reflectance, which complicates its interpretation, particularly at low leaf area indices (LAI) [

34]. Our investigation of the Modified Chlorophyll Absorption Ratio Index (MCARI) is motivated by its promising applications in remote sensing for precision agriculture. In contrast to other indices that rely heavily on multiple narrow spectral bands and have a strong correlation with chlorophyll concentration, MCARI offers greater versatility.

To overcome these limitations, the paper employs an enhanced version of the MCARI designed to improve sensitivity at low chlorophyll concentrations. Some researchers have proposed augmenting MCARI with soil-adjusted indices, such as the Optimized Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (OSAVI), to reduce the influence of background reflectance and improve the detection of leaf chlorophyll variability [

34]. OSAVI is mathematically derived from the Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) to effectively account for soil effects.

This paper presents the TCARI/OSAVI ratio as an effective approach for accurately estimating crop chlorophyll content through multispectral remote sensing imagery.

2.4. Rosemary and Sage Harvesting Time Individuation, Collecting and Drying

At the beginning of the rosemary flowering (27th April 2024) and sage before flowering (24th May 2024), measurements were carried out using a UAV DJI Phantom 4, equipped with a multispectral camera. The high-resolution multispectral images were ortho-mosaicked and thematic maps of NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) and TCARI/OSAVI ratio indices were generated to assess the right time for rosemary and sage harvesting. The harvested rosemary and sage were then dried [

19,38].

2.5. A Smart Solar Dryer WSN-Based System

The drying method used involves the application of forced hot air convection to extract moisture. Herb biomass is distributed over extensive areas in one or more layers, allowing dry air to circulate above it. Throughout the process, the temperature is maintained at 40°C and the relative humidity at 25%. This technique is designed to reduce the water content of the herbs while preserving their quality by limiting microbial and enzymatic activity (

Figure 2) [

19,39,40].

2.6. Hygienic and Safety Aspects of Rosemary and Sage

The microbiological assessment of both fresh and dried rosemary and sage was conducted using a culture-dependent approach, following a specific methodology [38]. Briefly, ten grams of each aromatic herb were homogenized in Ringer’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy), serially diluted in the same diluent, and placed on selective agar media as reported in

Table 2.

Detection of L. monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. was performed on 25 g of each herb sample, following the ISO 11290-1 (2017) and ISO 6579-1 (2017) [41,42] guidelines, respectively. All agar media were spread plated, except those used for growing members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, which were pour plated on double-layered agar. The plate counts were incubated aerobically. Analyses were performed in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

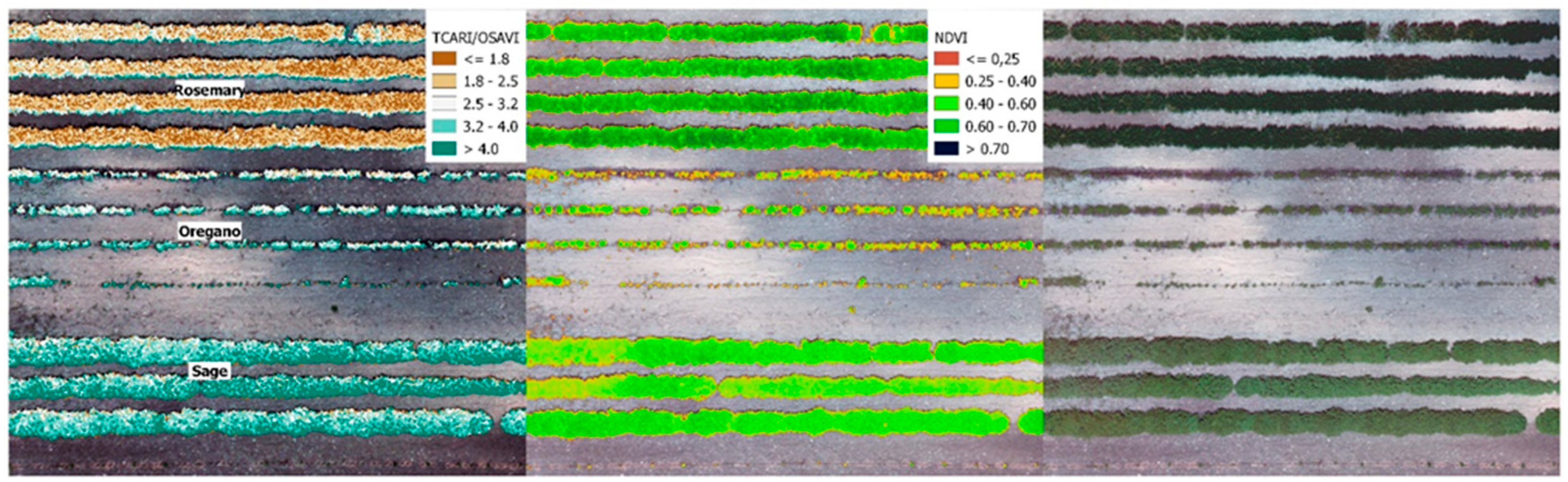

3.1. Rosemary and Sage Harvesting Time

The collected biomass was intended for the drying process, so it was necessary to identify the time of complete flowering for rosemary and before flowering for sage. The harvested plants belonged to local ecotypes characterized by considerable genotypic variability and non-uniform flowering. The NDVI index is sensitive toward crop biophysical properties like nitrogen, chlorophyll, vigor, and biomass etc. The rosemary was harvested when the NDVI values of most of the plants were equal to 0.64 and high flowering was evident from visual checks (

Figure 3). The sage was harvested when the NDVI values of the most of the plants were equal to 0.59.

The analysis demonstrates that the combined use of TCARI and OSAVI is highly effective for estimating crop photosynthetic pigments. Predictive relationships for estimating chlorophyll based on the TCARI/OSAVI ratio were established using above-canopy reflectance data [37]. These results indicate a correlation between chlorophyll content and the slope of TCARI versus OSAVI. As a result, we calculated the TCARI/OSAVI ratio and evaluated its effectiveness in accounting for the influence of soil background reflectance and crop structural development. Our goal was to establish a distinct relationship between chlorophyll content and the TCARI/OSAVI combination. The analyses provided above demonstrate that the integrated application of TCARI and OSAVI holds significant promise for estimating crop photosynthetic pigments. Predictive scaling relationships were developed to estimate chlorophyll levels based on the TCARI/OSAVI ratio obtained from above-canopy reflectance data. The TCARI/OSAVI ratio serves as a spectral indicator of pigment concentrations at the canopy level. By reducing the impact of LAI variability, it demonstrates a strong correlation and a distinct relationship with chlorophyll content.

As shown in

Figure 3, the chlorophyll values were high for the low TCARI OSAVI values and high NDVI values.

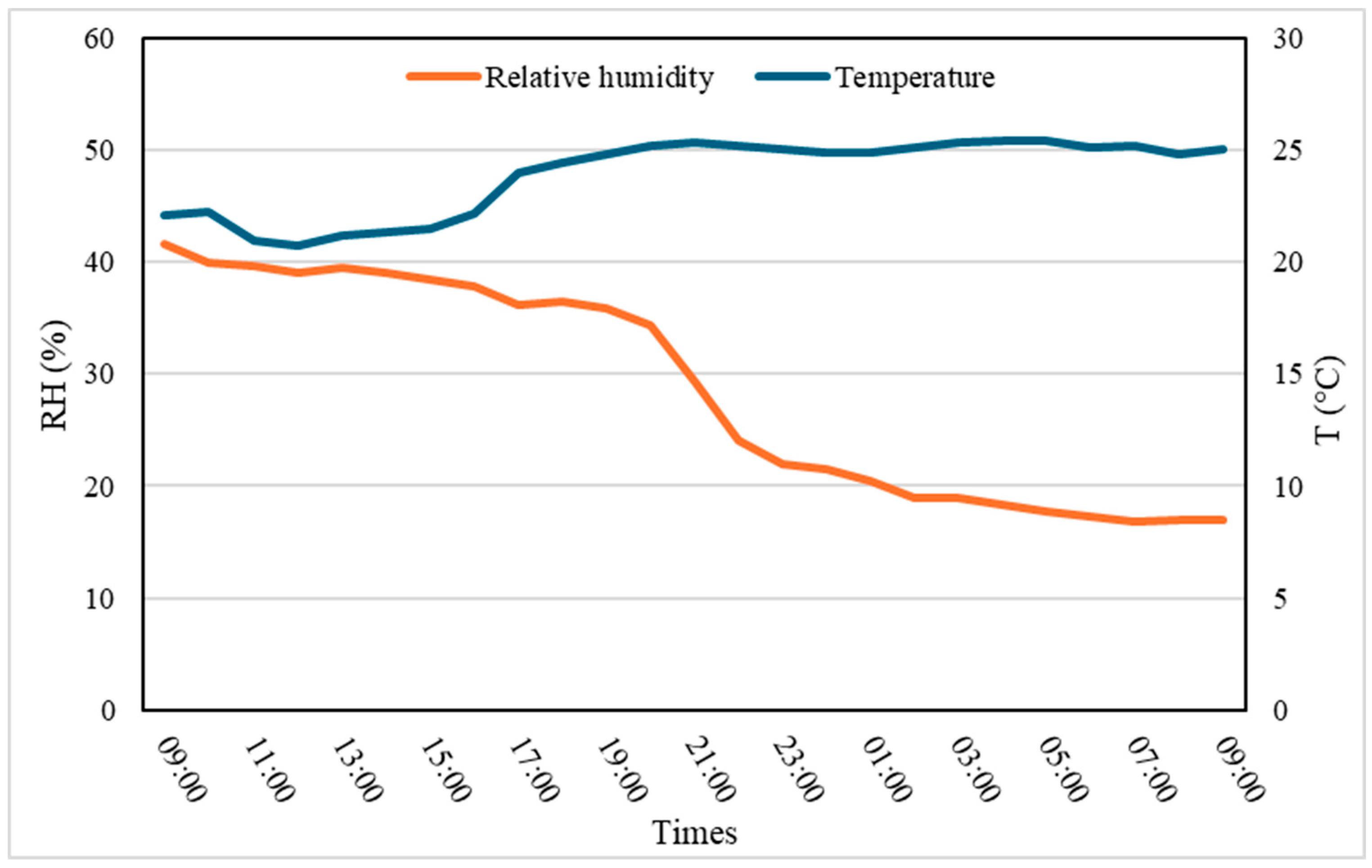

3.2. Drying Process Results

The volume of water extracted from the product during each drying cycle can be calculated [

19]. Approximately 109 Liters of water are eliminated in every full-load drying cycle. An absorption machine, with a dehumidification capacity of 52.8 kg per 24 hours, is sized according to this volume. Each drying cycle has a duration of 23.5 hours, essentially spanning one day. Alongside the absorption machine, a reversible compression heat pump rated at 9000 BTU is employed to regulate the temperature within the drying chamber, maintaining it between 10 and 30 °C. The contribution of the air conditioning unit to dehumidification is not factored into the sizing of the photovoltaic dryer.

The solar dryer is engineered to fulfil its annual energy requirements using electricity generated by photovoltaic panels installed on the roof and facades of the drying structure. The system comprises six modules on the roof and another six on the south elevation, with each module providing 500 W of power. The photovoltaic generator has an annual energy output potential of 8383 kWh, with strings 1 and 2 yielding 4407 kWh and 3976 kWh, respectively. The total electrical energy demand for each drying cycle, which includes operating temperature and humidity sensors, the PLC, and LED lighting, is 190 kWh.

In summary, the photovoltaic dryer is designed to effectively remove moisture from the product while adhering to the renewable energy constraints set by the photovoltaic generator, ensuring a sustainable operational model.

The dehumidification process commenced at 9 a.m. on May 31, 2024, and concluded at 8:30 a.m. on June 1, 2024, lasting less than a day (refer to

Figure 4). Initially, the relative humidity (RH) in the drying chamber was 41%, which dropped to 8% after approximately 24 hours, during which the door was opened for inspection. The temperature started at 22.5 °C, then decreased before gradually rising to 25 °C when the door was opened for checking.

Data collected by sensors were transmitted via Wi-Fi to a ThingSpeak account, allowing for real-time monitoring of the drying process. This data included fluctuations in product moisture content and drying rates. The Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) was instrumental in providing decision support throughout the drying process, enabling precise tracking of moisture loss and drying rates for both rosemary and sage.

At the conclusion of the drying cycle, the moisture content was measured at 15% for sage and 17% for rosemary. The fresh-to-dry weight ratio was 100/41 for sage and 100/62 for rosemary, with the final weights of the dried biomass being 32.6 kg for sage and 63.7 kg for rosemary.

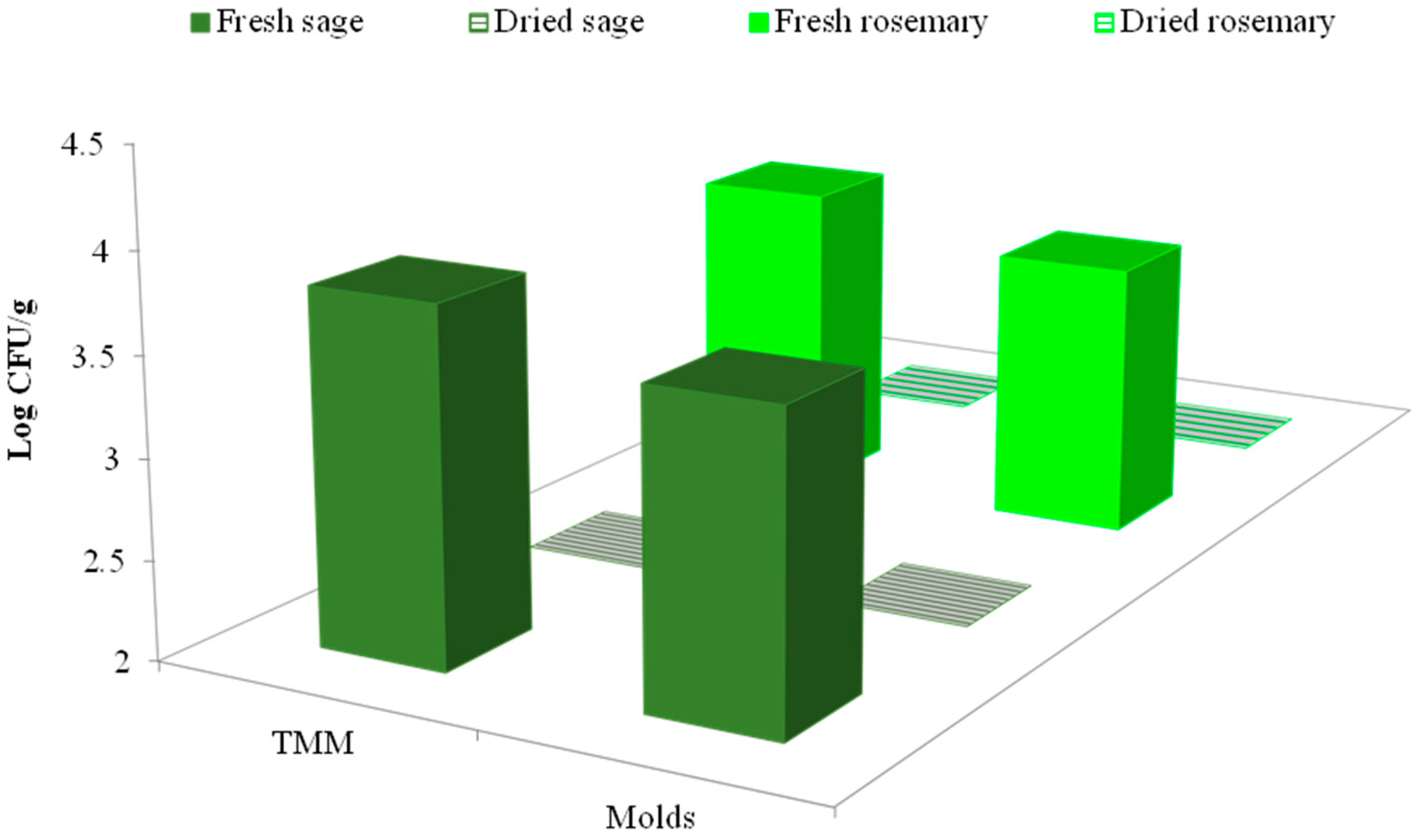

3.3. Safety Criteria for Foodstuffs

Both fresh and dehydrated rosemary and sage samples underwent microbiological analysis to assess their suitability for human consumption. This assessment is essential before using aromatic herbs and spices in food applications, as they are serve as carriers for foodborne pathogens [43,44]. The investigation specifically targeted the main bacterial pathogens, including members of the Enterobacteriaceae family,

E. coli, coagulase-positive staphylococci,

Salmonella spp., and

L. monocytogenes. These pathogens are well-known causative agents of global foodborne illness outbreaks and pose significant public health risks [45,46]. Surprisingly, none of the samples analyzed revealed detectable levels of these pathogens.

Figure 5 shows the viable counts of TMM and molds present on rosemary and sage before and after dehydration process. Fresh aromatic herbs samples consistently hosted levels between 10

3 and 10

4 Colony Forming Units (CFU)/g. The presence of TMM and mold likely originates from environmental contamination [47,48]. However, the drying process completely eradicated TMM and molds from rosemary and sage, rendering their levels were undetectable (reported as “2” in the

Figure 5). From a microbiological standpoint, the dried herbs produced in this study met the specifications set by the International Commission for Spices, Herbs, and Dried Vegetable Seasonings, which establishes a limit of 10

4 CFU/g total bacteria at 30 °C [49].

4. Conclusions

The latest advancements in medicinal and aromatic crops are changing how we perceive and utilize these plants. Sustainable farming practices, genetic enhancements, and investigations into their medicinal qualities are among the innovations driving this transformation. These breakthroughs not only benefit the environment, farmers, and consumers by providing a wider range of top-notch products but also position these crops to be key players in multiple sectors, such as agriculture and healthcare, as the global focus shifts towards sustainability and wellness.

The proposed method in this paper shows great potential for practical application in precision agriculture by accurately estimating crop photosynthetic pigments without needing prior knowledge of canopy architecture. However, its robustness must be tested in early growth stages when Leaf Area Index (LAI) is low, as this information is crucial for operational use. The method could be beneficial for various crops, and future research should aim to develop a simple index with predictive capabilities similar to the TCARI/OSAVI ratio, focusing on optimizing spectral band combinations to improve sensitivity to chlorophyll content variations while minimizing the influence of background and canopy structure.

With precision aromatic crop and smart technologies applied to these farms paving the way, the future looks promising for these versatile and valuable plants, offering new opportunities in healthcare, agriculture, and culinary arts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G. and M.M.; Methodology, R.G., C.G. and M.M.; Validation, L.S., C.G. and L.C.; Formal Analysis, R.G., L.C., C.G. and L.S.; Resources, C.G. and M.M.; Data Curation, S.O. and R.G.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.C., C.G., L.S. and S.O.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.G., S.O.; Visualization, C.G., R.G. and S.O.; Supervision, C.G. and M.M.; Project Administration, S.C. and M.M.; Funding Acquisition, M.M.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “PREVANIA - Prodotti ad elevato valore nutrizionale ed a impatto ambientale ridotto”, bando PSR Sicilia 2014-2020, sottomisura 16.1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Konfo, T. R. C., Chabi, A. B. P., Gero, A. A., Lagnika, C., Avlessi, F., Biaou, G., Sohounhloue, C. K. D. Recent climate-smart innovations in agrifood to enhance producer incomes through sustainable solutions. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2024, Volume 15, 100985, ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Choruma, D. J., Dirwai, T. L., Mutenje, M. J., Mustafa, M., Chimonyo, V. G. P., Jacobs-Mata, I., Mabhaudhi, T. Digitalisation in agriculture: A scoping review of technologies in practice, challenges, and opportunities for smallholder farmers in sub-saharan africa. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2024, Volume 18, 101286, ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Rakholia, R., Tailor, J., Prajapati, M., Shah, M., Saini, J. R. Emerging technology adoption for sustainable agriculture in India– a pilot study. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2024, Volume 17, 101238, ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P., Ganguly, A., Adhikary, S., Bhattacharya, S. Internet of Things and smart sensors in agriculture: Scopes and challenges. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2023, Volume 14, 100776, ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.P., Montoya-Munoz, A.I., Rodriguez-Pabon, C., Hoyos, J., Corrales, J.C. IoT-Agro: A smart farming system to Colombian coffee farms. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2021, Volume 190, 106442, ISSN 0168-1699. [CrossRef]

- Kwaghtyo, D.K., Eke, C.I. Smart farming prediction models for precision agriculture: a comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev, 2023, 56, 5729–5772. [CrossRef]

- Lykas, C.; Vagelas, I. Innovations in Agriculture for Sustainable Agro-Systems. Agronomy, 2023, 13, 2309. [CrossRef]

- Taoufik, B., Rhaimi, C., Alomari, S., Aljuhani, L. Design and Implementation of an Integrated IoT and Artificial Intelligence System for Smart Irrigation Management. International Journal of Advances in Soft Computing and its Applications, 2024, Volume 16, Issue 1, Pages 197 – 218. [CrossRef]

- Muhie, S. H. Novel approaches and practices to sustainable agriculture. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2022, Volume 10, 100446, Article 100446. ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Lytos, A., Lagkas, T., Sarigiannidis, P., Zervakis, M., Livanos, G. Towards smart farming: Systems, frameworks and exploitation of multiple sources. Computer Networks, 2020, Volume 172, 107147, ISSN 1389-1286. [CrossRef]

- Széles, A., Huzsvai, L., Mohammed, S., Nyéki, A., Zagyi, P., Horváth, E., Simon, K., Arshad, S., Tamás, A. Precision agricultural technology for advanced monitoring of maize yield under different fertilization and irrigation regimes: A case study in Eastern Hungary (Debrecen). Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2024, Volume 15, 100967, ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M., Haleem, A., Singh, R. P., Suman, R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Intelligent Networks, 2022, Volume 3, Pages 150-164, ISSN 2666-6030. [CrossRef]

- Kwaghtyo, D.K., Eke, C.I. Smart farming prediction models for precision agriculture: a comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev, 2023, 56, 5729–5772. [CrossRef]

- Virk, A.L., Noor, M.A., Fiaz, S., Hussain, S., Hussain, H.A., Rehman, M., Ahsan, M., Ma, W. Smart farming: an overview. In Smart Village Technology, 2020, pp 191–201.

- Mesgaran, M.B., Madani, K., Hashemi, H., Azadi, P. Iran’s land suitability for agriculture. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Balafoutis, A.T., Beck. B., Fountas, S., Tsiropoulos, Z., Vangeyte, J., van der Wal, T., Soto-Embodas, I., Gómez-Barbero, M., Pedersen, S.M. Smart Farming Technologies – Description, Taxonomy and Economic Impact, 2017, ISBN 978-3-319-68713-1, ISSN 2511-2260, p. 21-77, JRC106795. [CrossRef]

- Abhinav, S., Jain, A., Gupta, P., Chowdary, V. Machine learning applications for precision agriculture: a comprehensive review, 2021. IEEE Access 9:4843–4873. [CrossRef]

- Petrović, B., Bumbálek, R., Zoubek, T., Kuneš, R., Smutný, L., Bartoš, P. Application of precision agriculture technologies in Central Europe-review. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 2024, Volume 15, 101048, ISSN 2666-1543. [CrossRef]

- Mammano, M.M., Comparetti, A., Ciulla, S., Greco, C., Orlando, S. A prototype of photovoltaic dryer for nutraceutical and aromatic plants. In: Ferro, V., Giordano, G., Orlando, S., Vallone, M., Cascone, G., Porto, S.M.C. (eds) AIIA 2022: Biosystems Engineering Towards the Green Deal. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 2023, vol. 337. Springer, Cham.

- Al-Hamdani, A., Jayasuriya, H., Pathare, P.B., Al-Attabi, Z. Drying Characteristics and Quality Analysis of Medicinal Herbs Dried by an Indirect Solar Dryer. Foods, 2022, 11, 4103. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A., Alibas, I., Asik, B. B. The effect of drying methods on the color, chlorophyll, total phenolic, flavonoids, and macro and micronutrients of thyme plant. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2021, 45, e15915. [CrossRef]

- Campiotti, C.A., Bibbiani, C., Greco, C. Renewable energy for greenhouse agriculture. J. Sustain. Energy 2019, 20, 152–156.

- Greco, C., Campiotti, A., De Rossi, P., Febo, P., Giagnacovo, G. Energy consumption and improvement of energy efficiency for the European agricultural-food system. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità, 2020, Volume 2020, Issue 1, Pages 92 - 103. [CrossRef]

- Greco, C., Campiotti, A., Latini, A., Agnello, A., Jotautiene, E., Mammano, M.M. Innovation for the Italian agricultural and food industry sector. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità, 2019, Volume 2019, Issue 2, Pages 115 – 126. [CrossRef]

- Attard, G., Comparetti, A., Febo, P., Greco, C., Massimo Mammano, M., Orlando, S. Case study of potential production of renewable energy sources (RES) from livestock wastes in Mediterranean islands. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 2017, 58, 1-7.

- Garofalo, G., Buzzanca, C., Ponte, M., Barbera, M., D'Amico, A., Greco, C., Mammano, M.M., Franciosi, E., Piazzese, D., Guarrasi, V., Ciulla, S., Orlando, S., Di Grigoli, A., Bonanno, B., Di Stefano, V., Settanni, L., Gaglio, R. Comprehensive analysis of Moringa oleifera leaves’ antioxidant properties in ovine cheese. Food Bioscience, 2024, 61, 104974. [CrossRef]

- Mammano, M.M., Comparetti, A., Greco, C., Orlando, S. A model of Sicilian environmentally friendly multifunctional farm for soil protection. In: Ferro, V., Giordano, G., Orlando, S., Vallone, M., Cascone, G., Porto, S.M.C. (eds) AIIA 2022: Biosystems Engineering Towards the Green Deal. AIIA 2022. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 2023, vol 337. Springer, Cham.

- Greco, C., Catania, P., Orlando, S., Vallone, M., Mammano, M.M. Assessment of Vegetation Indices as Tool to Decision Support System for Aromatic Crops. In: Berruto, R., Biocca, M., Cavallo, E., Cecchini, M., Failla, S., Romano, E. (eds) Safety, Health and Welfare in Agriculture and Agro-Food Systems. SHWA 2023. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 2024, vol 521. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., Su, B., Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. Journal of Sensors, 2017, 1353691, 17 pages. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R., Jr., Daughtry, C.S.T., Eitel, J.U.H., Long, D.S. Remote Sensing Leaf Chlorophyll Content Using a Visible Band Index. Agronomy Journal, 2011, 103: 1090-1099. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Gitelson, A. A. Application of chlorophyll-related vegetation indices for remote estimation of maize productivity. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2011, Volume 151, Issue 9, 2011, Pages 1267-1276, ISSN 0168-1923. [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P. J., Miller, J. R., Mohammed, G. H., Noland, T. L., Sampson, P. H. Estimation of chlorophyll fluorescence under natural illumination from hyperspectral data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2001, Volume 3, Issue 4, 2001, Pages 321-327, ISSN 1569-8432. [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J., Miller, J.R., Mohammed, G. H. Noland, T.L. Chlorophyll fluorescence effects on vegetative apparent reflectance: I. Leaf-level measurements and model simulation. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2000, 74, 582-595. [CrossRef]

- Daughtry, C., Walthall, C., Kim, M., Colstoun, E.B., McMurtrey, J.E. Estimating Corn Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration from Leaf and Canopy Reflectance. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2000, 74, 229-239. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S., Daughtry, C.S., Chappelle, E.W., McMurtrey, J.E., Walthall, C.L. The use of high spectral resolution bands for estimating absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (A par), 1994.

- Zarco-Tejada, P. J., Miller, J. R., Mohammed, G. H., Noland, T. L., Sampson, P. H. Estimation of chlorophyll fluorescence under natural illumination from hyperspectral data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2001, Volume 3, Issue 4, Pages 321-327, ISSN 1569-8432. [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D., Miller, J.R., Tremblay, N., Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Dextraze, L. Integrated Narrow-Band Vegetation Indices for Prediction of Crop Chlorophyll Content for Application to Precision Agriculture. Remote Sensing of Environment, 2002, 81, 416-426. [CrossRef]

- Catania, P., Gaglio, R., Orlando, S., Settanni, L., Vallone, M. Design and Implementation of a Smart System to Control Aromatic Herb Dehydration Process. Agriculture, 2020, 10(8), 332. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G., Greco, G., Salsi, G., Garofalo, G., Gaglio, R., Barbera, M., Greco, C., Orlando, S., Fascella, G., Mammano, M.M. Effect of the gellanbased edible coating enriched with oregano essential oil on the preservation of the ‘Tardivo di Ciaculli’ mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco cv. Tardivo di Ciaculli). Front. Sustain. Food Syst., 2024, 8:1334030. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1334030.

- Saini, R. K., Saini, D. K., Gupta, R., Verma, P., Thakur, R., Kumar, S., Ali wassouf, A. Technological development in solar dryers from 2016 to 2021-A review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2023, Volume 188, 2023, 113855, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- ISO 11290-1. Microbiology of the food chain — Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp. Part 1: Detection method, 2017. International Organization for Standardization.

- ISO 6579–1. Microbiology of the Food Chain–Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella–Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp., 2017. International Organization for Standardization.

- Sagoo, S.K., Little. C.L., Greenwood. M., Mithani, V., Grant, K.A., McLauchlin, J., de Pinna, E., Threlfall, E.J. Assessment of the microbiological safety of dried spices and herbs from production and retail premises in the United Kingdom. Food Microbiol., 2009 Feb;26(1):39-43. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.07.005.

- World Health Organization. Microbiological hazards in spices and dried aromatic herbs: meeting report, 2022, Vol. 27. Food & Agriculture Org.

- European Food Safety Authority, & European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA Journal, 2022, 20(12), e07666.

- Lee, H., Yoon, Y. Etiological agents implicated in foodborne illness worldwide. Food science of animal resources, 2021, 41(1), 1.

- Gerba, C. P., Pepper, I. L. Microbial contaminants. Environmental and pollution science, 2019, 191-217.

- Kostecka, M., Bojanowska, M. Mold contamination of commercially available herbal products and dietary supplements of plant origin. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering. A, 2013, 20(11), 1369-1379.

- International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods (were in compliance with the). Spices, herbs, and vegetable seasonings. Microorganisms in foods, microbial ecology of food commodities, 360-372.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).