Submitted:

04 August 2024

Posted:

05 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis

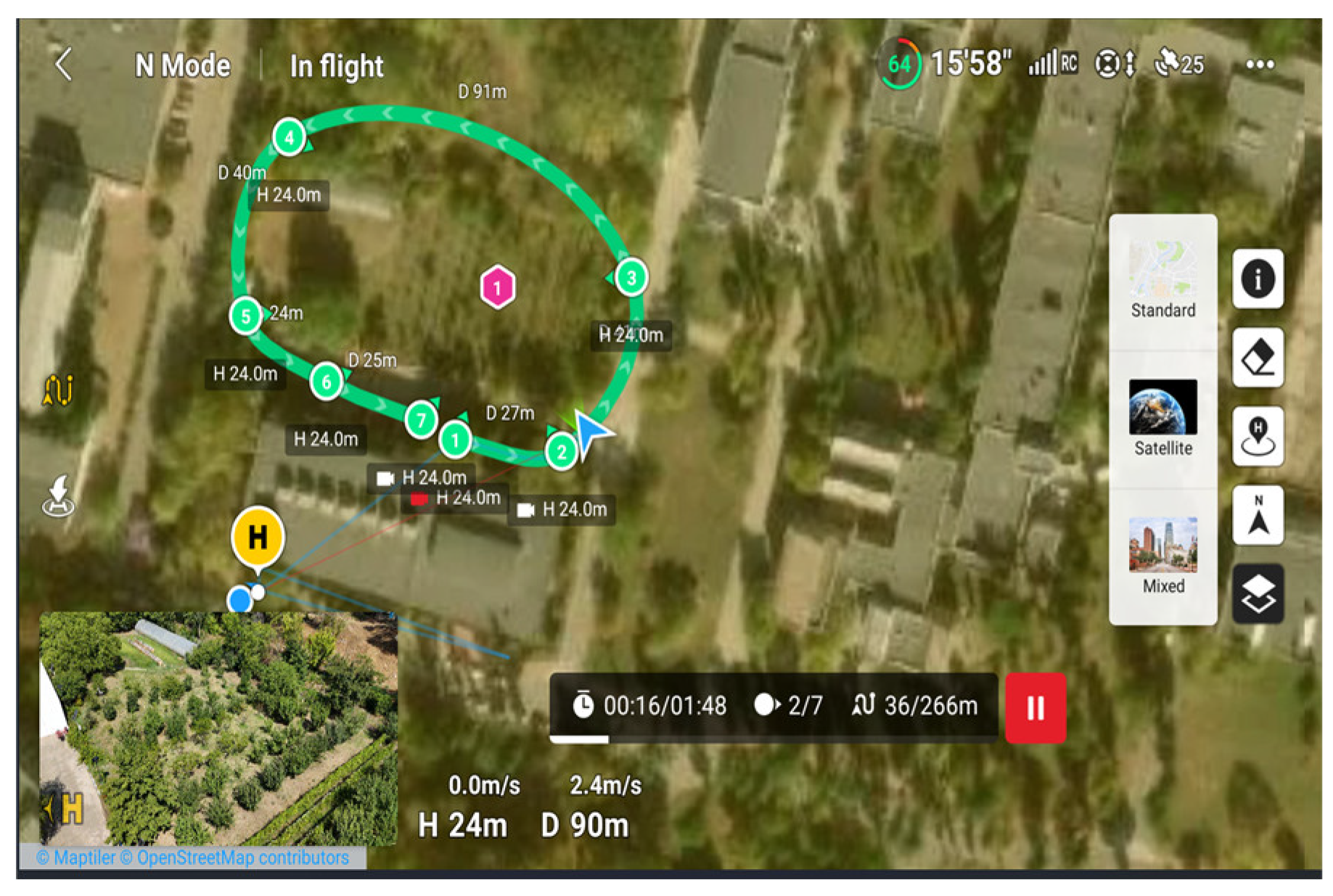

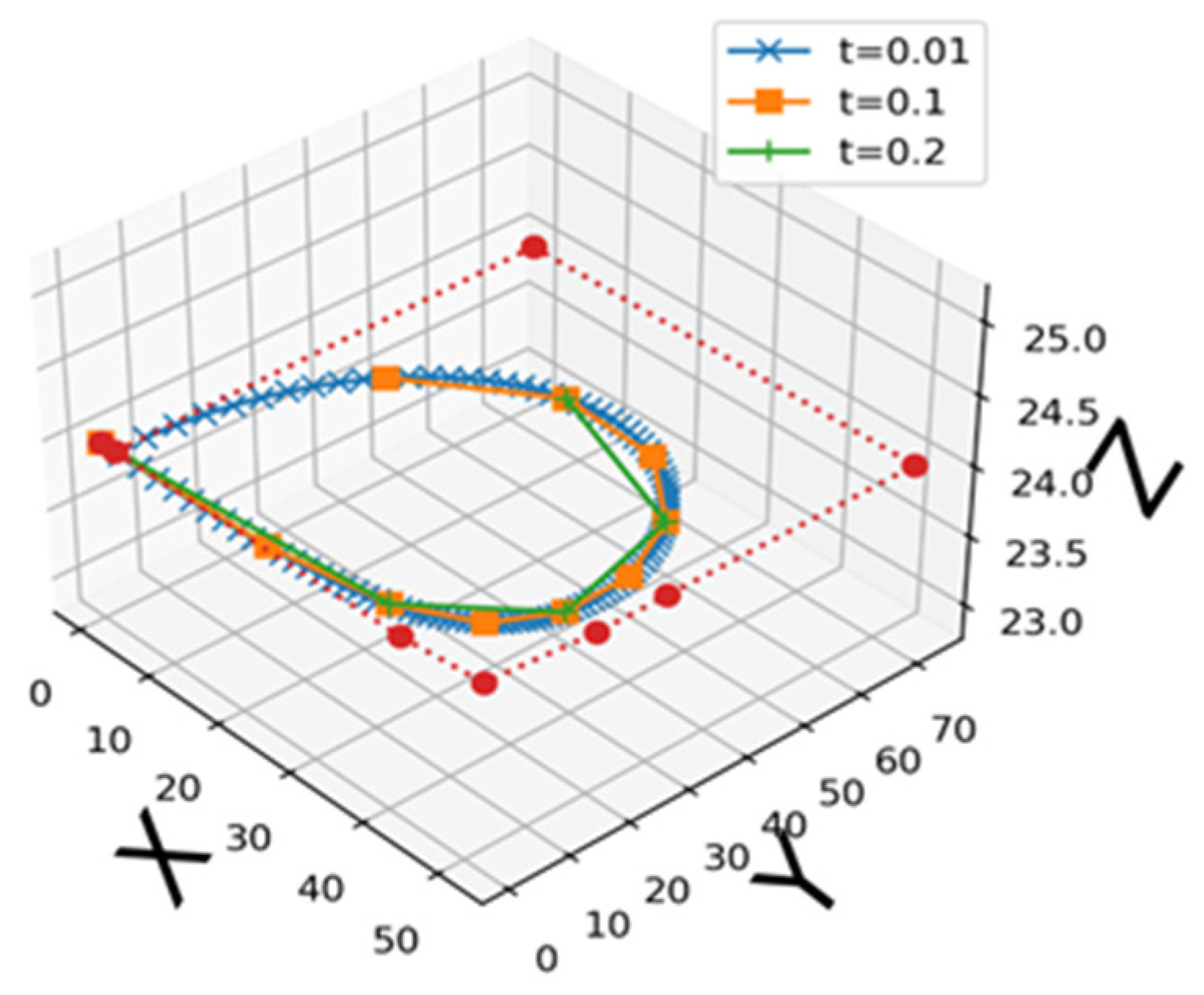

2.2. Route Planning

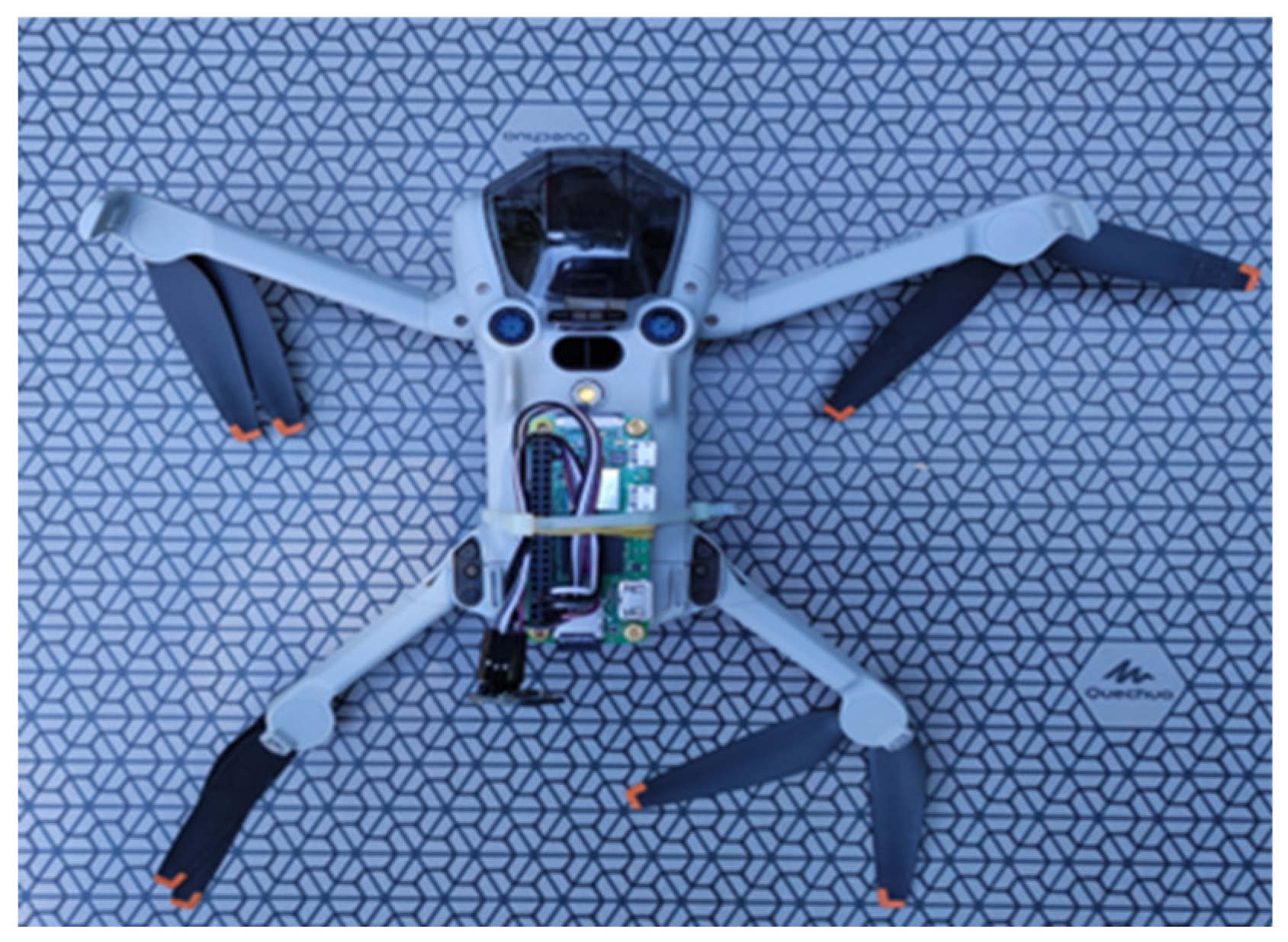

2.3. Hardware Components

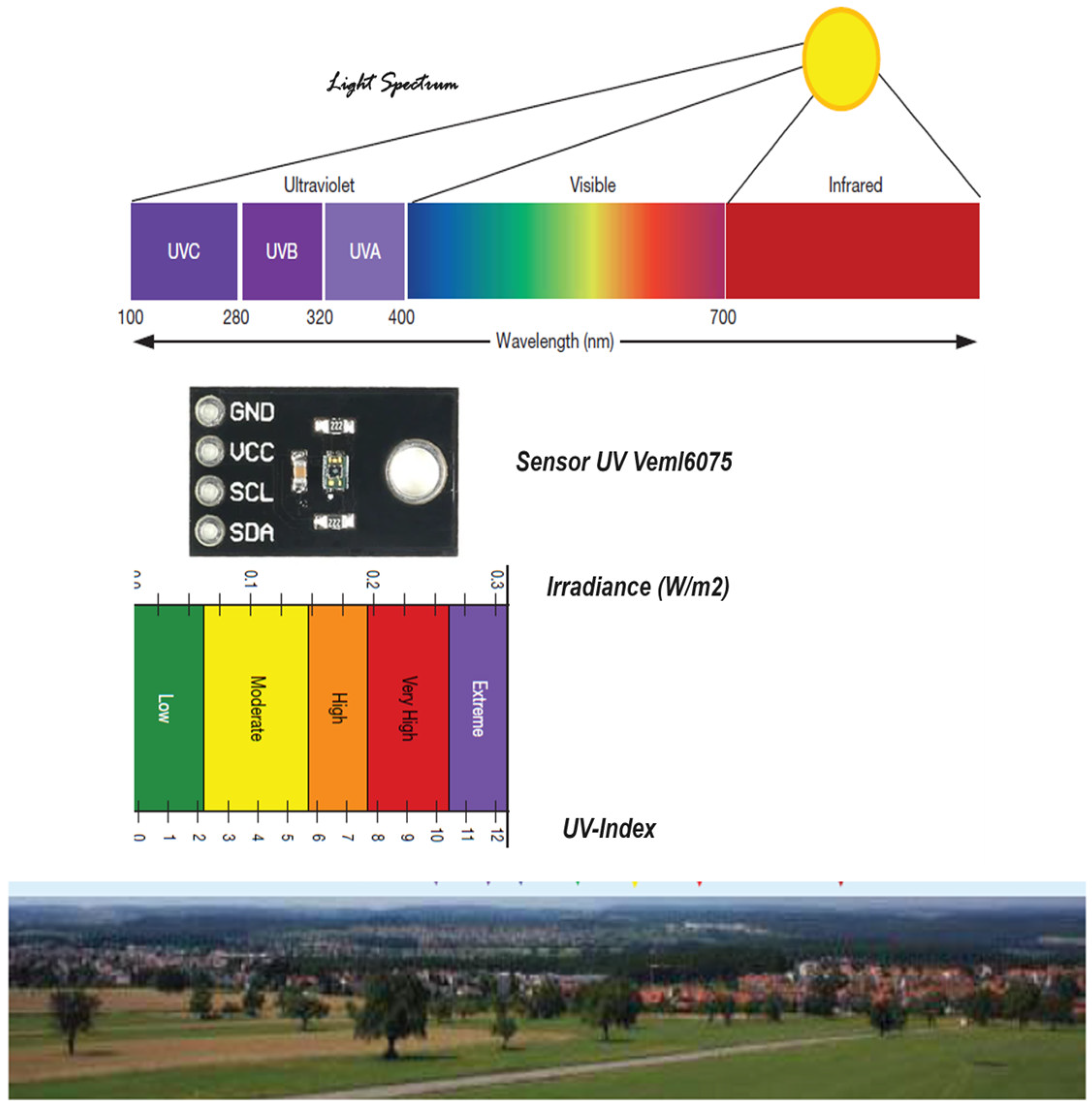

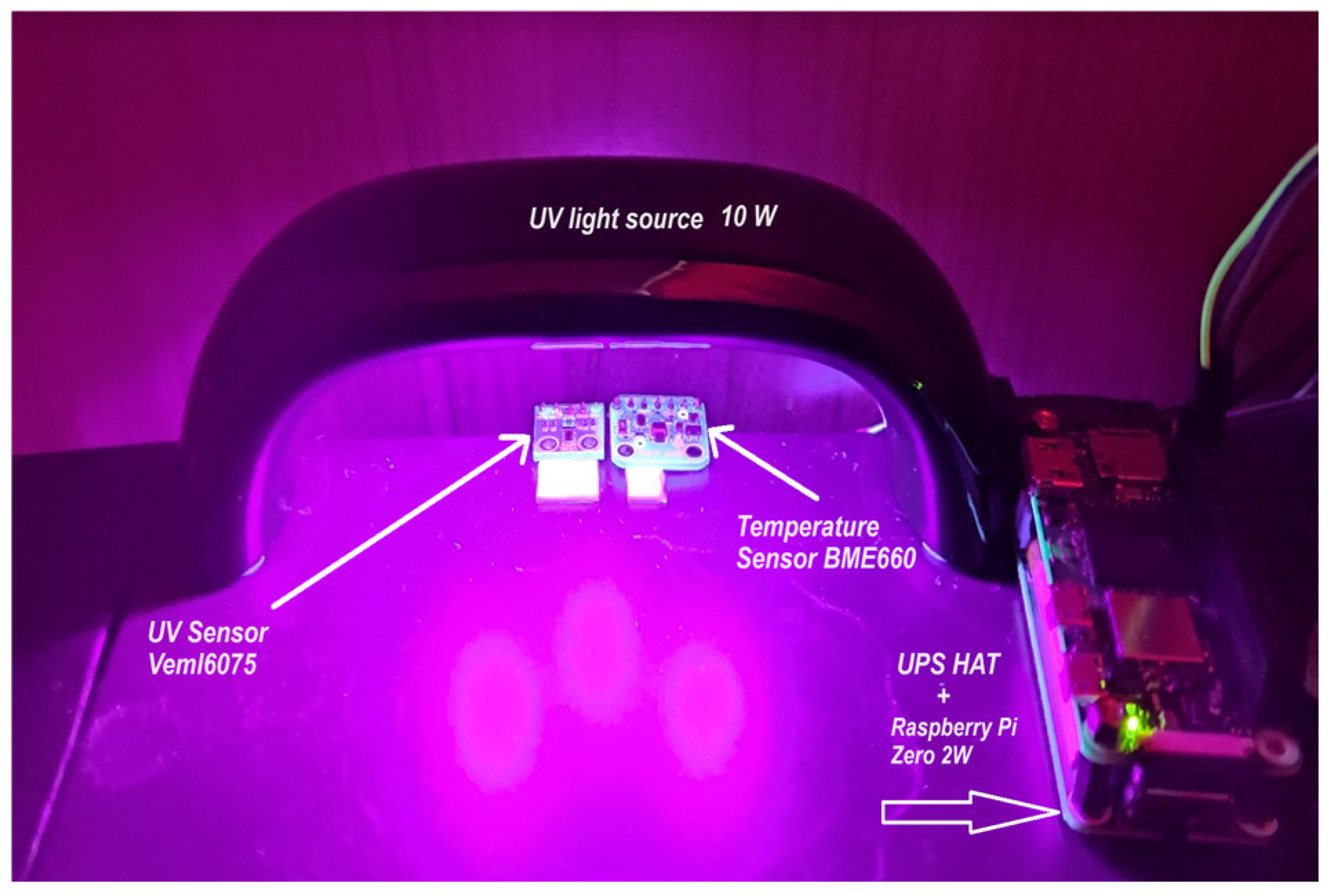

2.3.1. The VEML6075 sensor

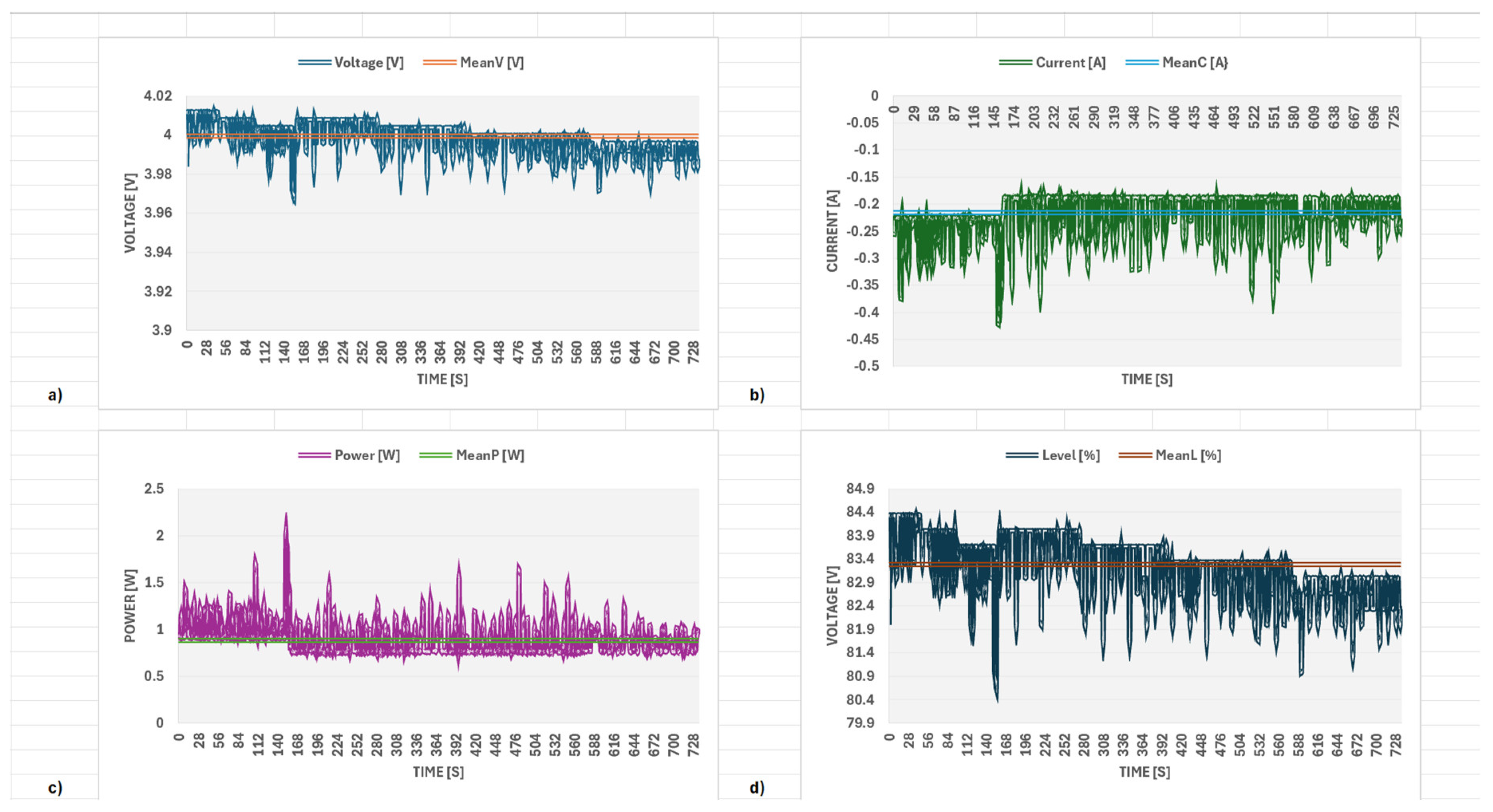

2.3.2. UPS HAT Waveshare 19739

2.3.3. The Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W

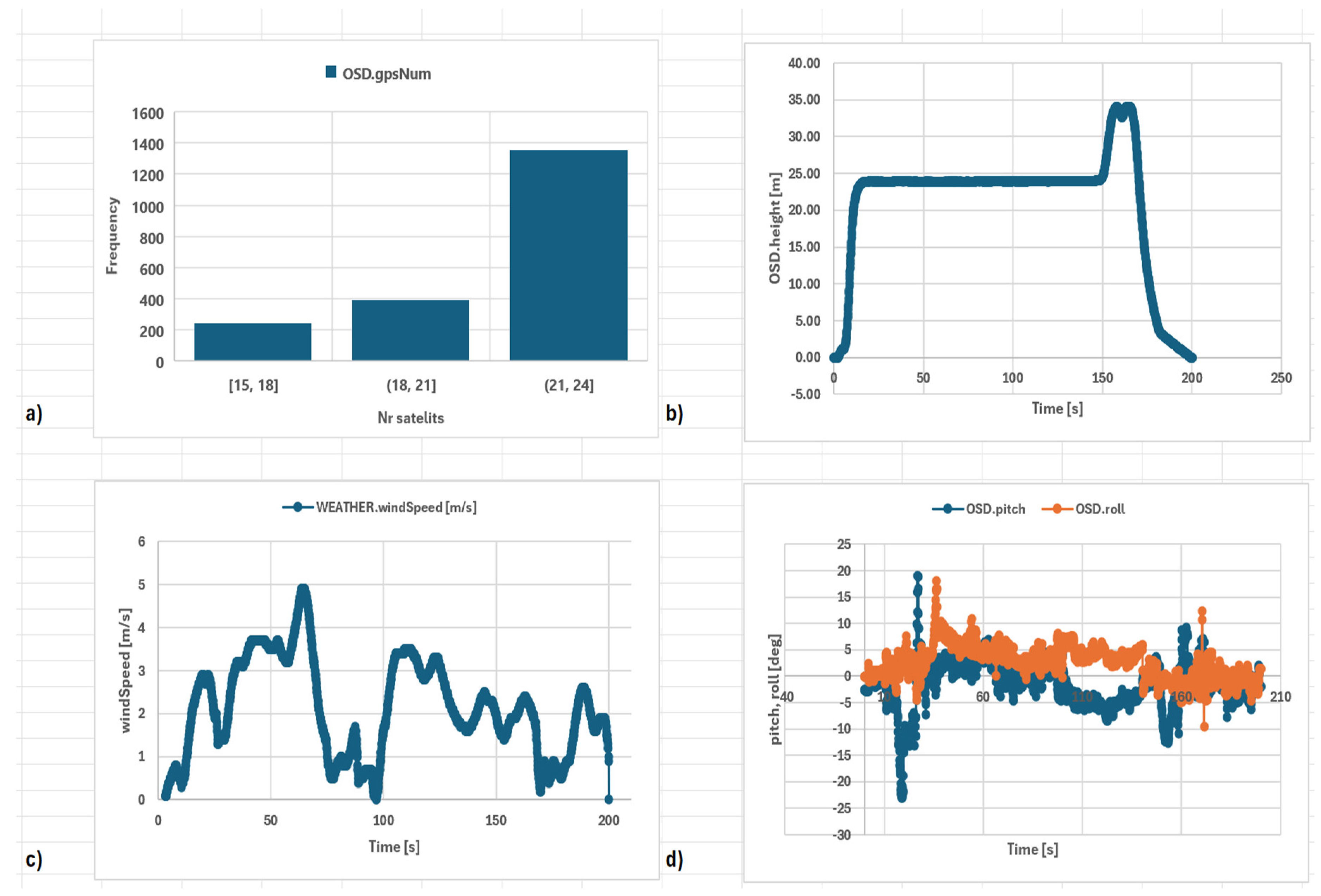

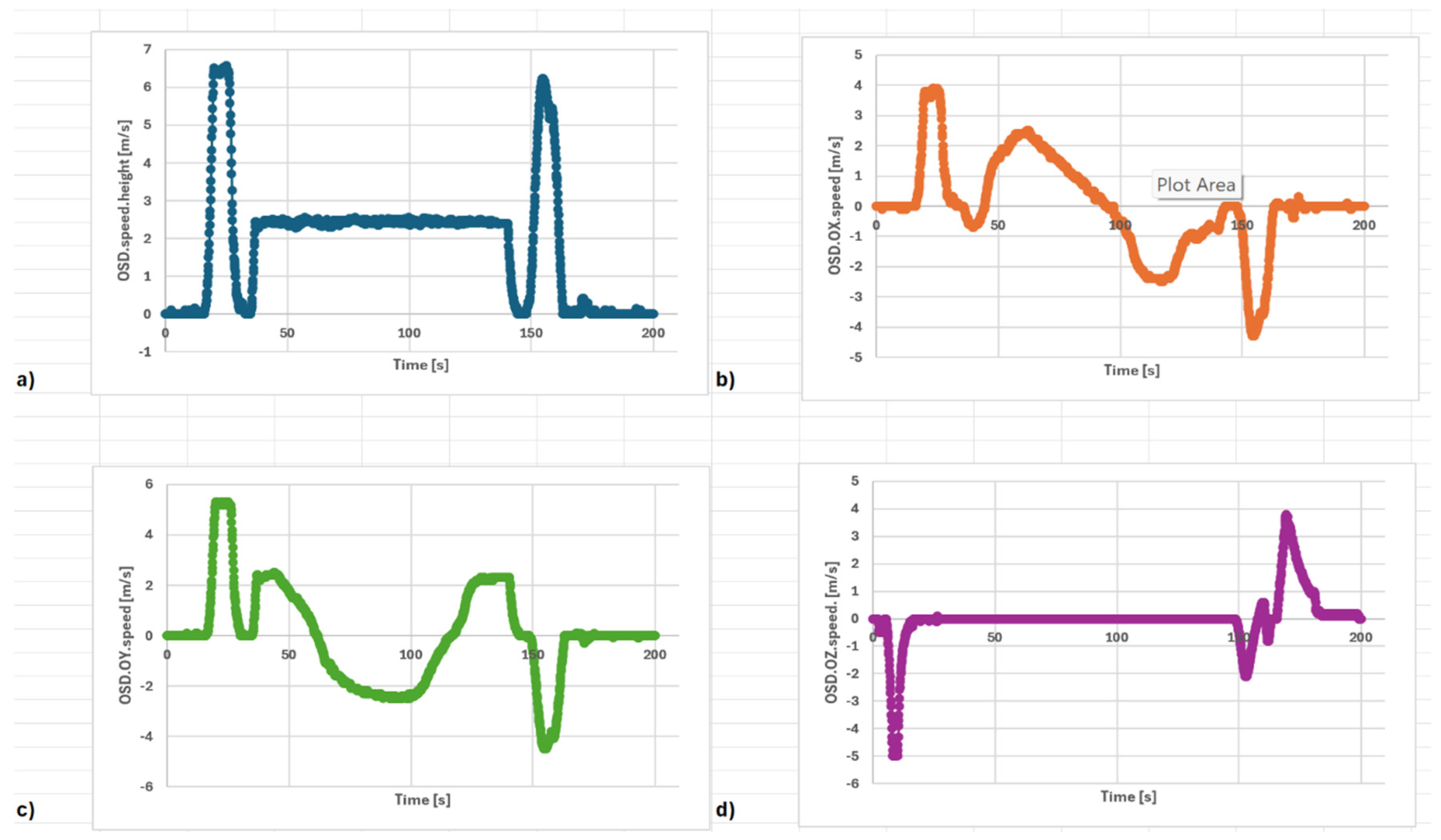

2.3.4. The DJI Mini 4 Pro

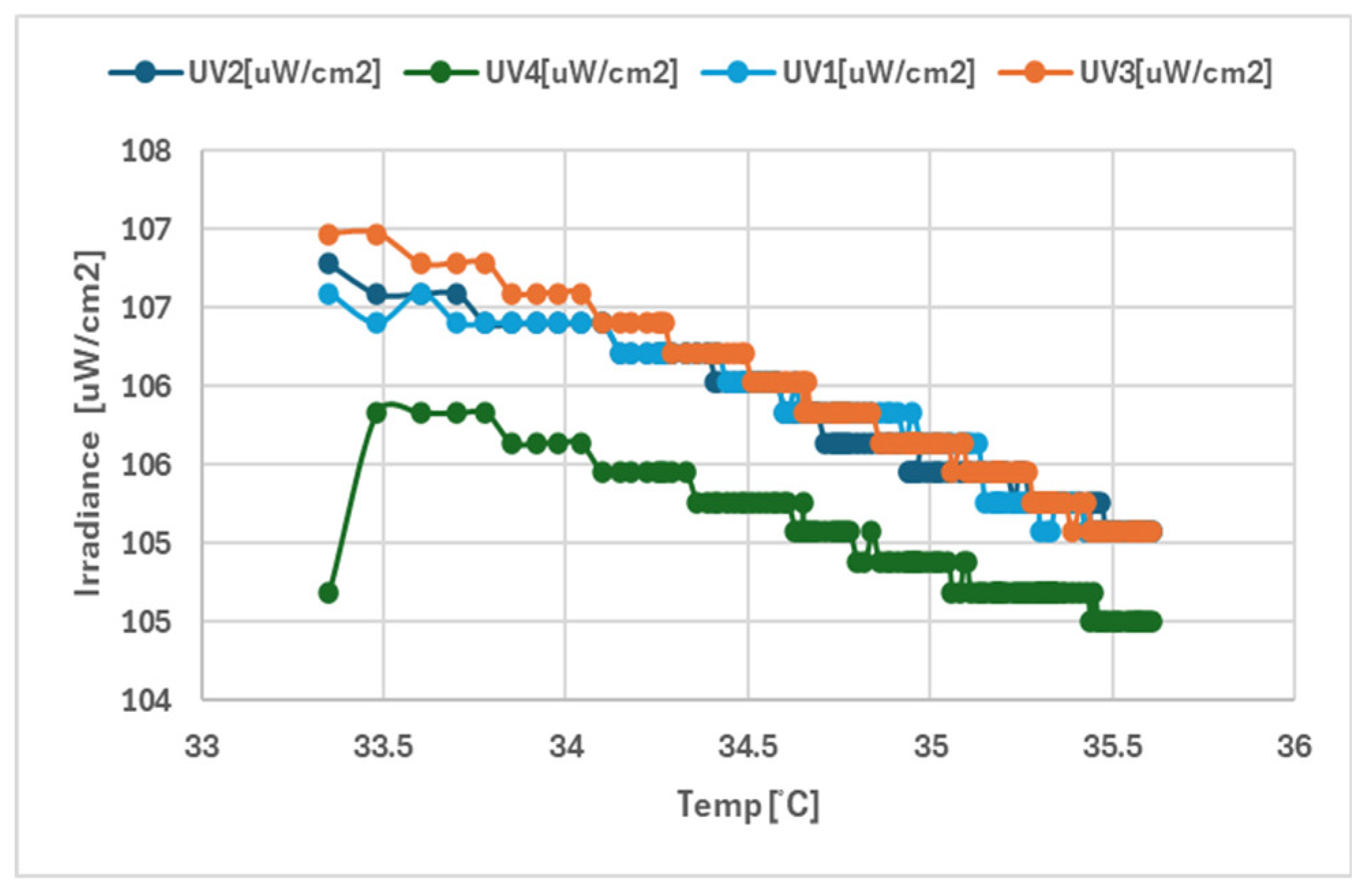

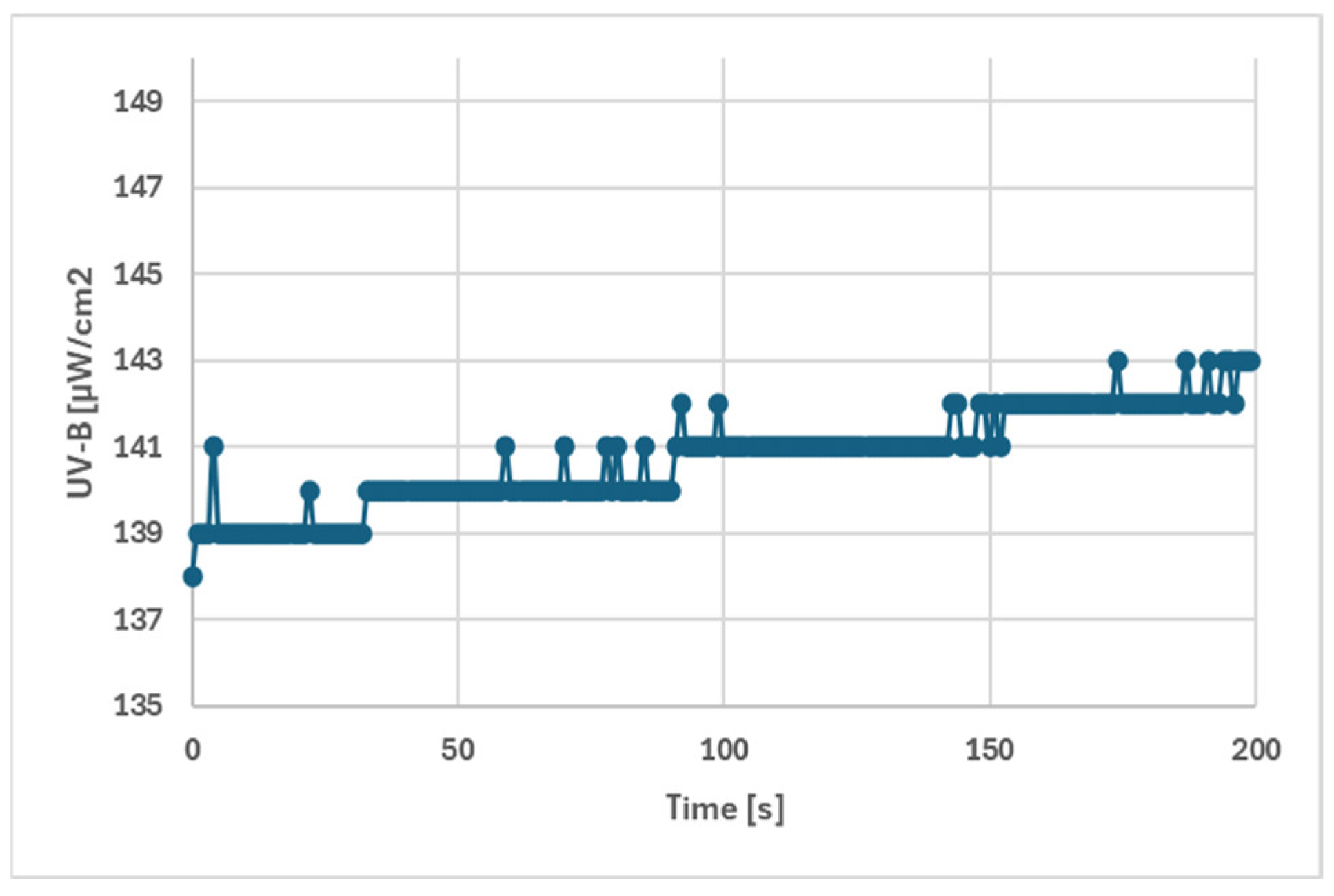

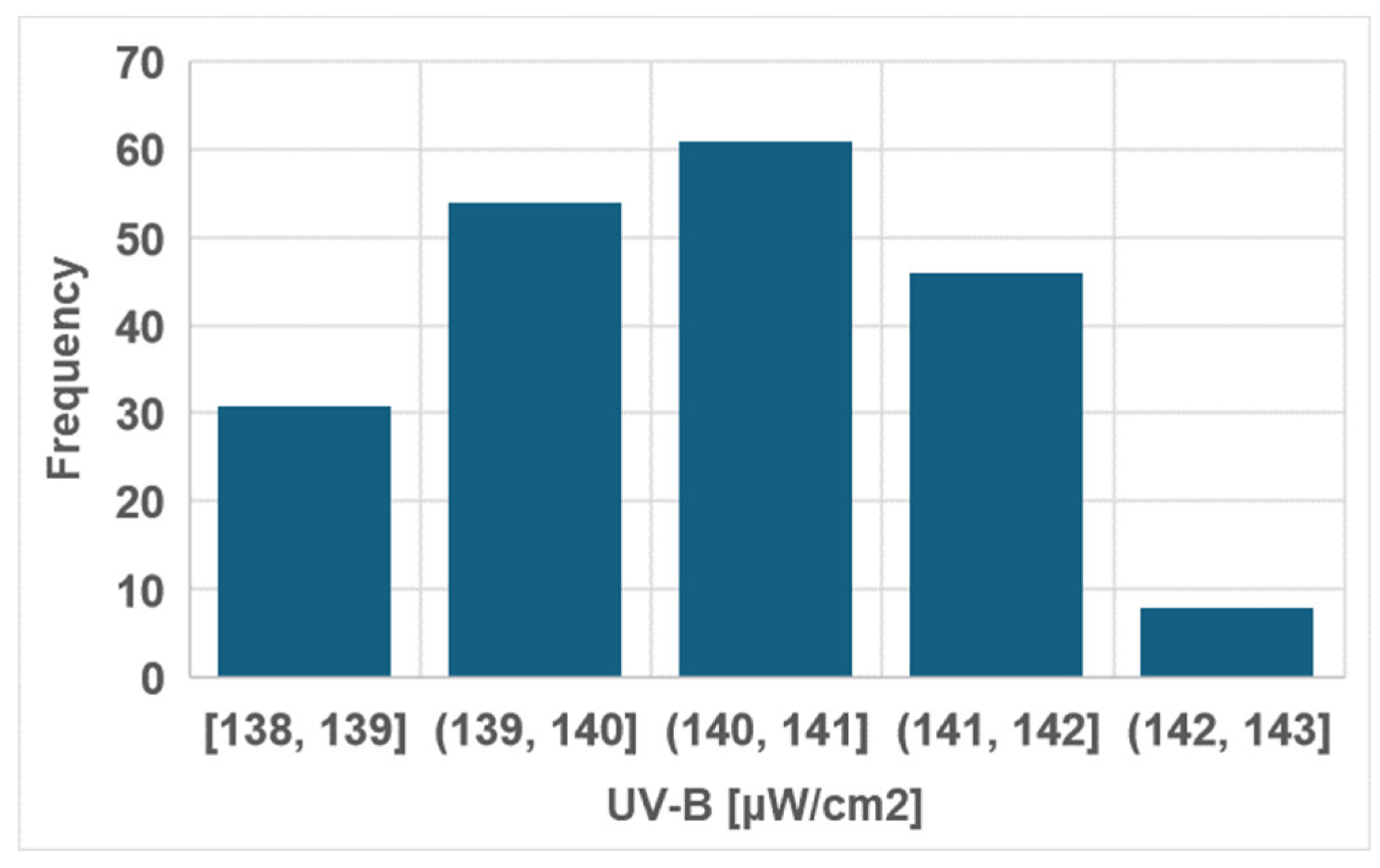

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hung, C. , Xu Z., Sukkarieh S., Feature learning based approach for weed classification using high resolution aerial images from a digital camera mounted on a UAV. Remote Sensing 2014, 6, 12037–12054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malveaux, C. , Hall S.G., Price R., Using drones in agriculture: unmanned aerial systems for agricultural remote sensing applications, Paper number 141911016, 2014 Montreal, Quebec Canada July 13 – July 16, 2014. @2014. [CrossRef]

- Aasen, H. , Honkavaara E., Lucieer A., Zarco-Tejada P. J., Quantitative remote sensing at ultra-high resolution with UAV spectroscopy: a review of sensor technology, measurement procedures, and data correction workflows. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipate, G. , Voicu G., Dinu I., Research on the use of drones in precision agriculture. University Politehnica of Bucharest Bulletin Series 2015, 77, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, D. , Vlasceanu E., Dima M., Stoican F., Ichim L., Hybrid sensor network for monitoring environmental parameters. 28th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED) 2020, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamate, M.A. , Pupaza C., Nicolescu F.A., Moldoveanu, C.E., Improvement of Hexacopter UAVs Attitude Parameters Employing Control and Decision Support Systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digulescu, A. , Despina-Stoian C., Popescu F., Stanescu D.; Nastasiu D.; Sburlan D, UWB Sensing for UAV and Human Comparative Movement Characterization. Sensors 2023, 23, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, D. , Ichim L., Stoican F., Orchard monitoring based on unmanned aerial vehicles and image processing by artificial neural networks: a systematic review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1237695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signing, V.R.F. , Taamte J.M., Noube M.K., Abanda Z.S.O., Abba H.Y., Real-time environmental radiation monitoring based on locally developed low-cost device and unmanned aerial vehicle. Journal of Instrumentation 2023, 18, P05031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.Y. , Min B.I., Suh K.S., Joung S., Kim K.P., Park J.H., Technical Status of Environmental Radiation Monitoring using a UAV and Its Field Application to the Aerial Survey. Journal of Korea Society of Industrial Information Systems 2020, 25, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezoudi, M. , Keleshis C., Antoniou P., Biskos G., Bronz M., Constantinides C., Sciare J., The Unmanned Systems Research Laboratory (USRL): A new facility for UAV-based atmospheric observations. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H. , Niu G., Gu M., Pre-harvest UV-B radiation and photosynthetic photon flux density interactively affect plant photosynthesis, growth, and secondary metabolites accumulation in basil (Ocimum basilicum) plants. Agronomy 2019, 9, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrolle, J. , García J.L., Ocete R., Figueroa M. E., Cantos M., Growth and photosynthetic responses to copper in wild grapevine. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, V.; Campoverde, B. , Yoo S.G., A Systematic Literature Review of LoRaWAN: Sensors and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, M. , Sharma A., Abrol Y.P., Sengupta U.K., Exclusion of UV-B radiation from normal solar spectrum on the growth of mung bean and maize Agriculture. Ecosystems & Environment 1997, 61, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramura, A.H. , Effects of ultraviolet-B radiation on the growth and yield of crop plants. Physiologia Plantarum 1983, 58, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G.F. , Krizek D.T., Mirecki R.M., Influence of photosynthetically active radiation and spectral quality on UV-B-induced polyamine accumulation in soybean. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R. , Gupta D.K., Sharma G.K., Chapter: Chemical stress on plants, In book: New frontiers in stress management for durable agriculture, Publisher: Springer 2020, 101-128. [CrossRef]

- Mirecki, R.M. , Teramura A.H., Effects of ultraviolet-B irradiance on soybean: V. The dependence of plant sensitivity on the photosynthetic photon flux density during and after leaf expansion. Plant physiology 1984, 74, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo-Minnolo, G. , Consoli S., Vanella D., Guarrera S., Manetto G., Cerruto E., Appraising the stem water potential of citrus orchards from UAV-based multispectral imagery, IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), Pisa, Italy, 2023, 120-125. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Chaves, F.F. , Palos-Sánchez, P.R. Exploring the evolution of human resource analytics: a bibliometric study. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mayyahi, A. , Aldair A.A., Rashid, A.T., Intelligent Control of Mobile Robot Via Waypoints Using Nonlinear Model Predictive Controller and Quadratic Bezier Curves Algorithm. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2020, 15, 1857–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. , Elkaim G.H., Bezier Curve for Trajectory Guidance, Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2008, WCECS 2008, October 22 - 24, 2008, San Francisco, USA.

- Elhoseny, M. , Tharwat A., Hassanien, A.E., Bezier Curve Based Path Planning in a Dynamic Field using Modified Genetic Algorithm. Journal of Computational Science 2018, 25, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R. , Wu Z., Liu X., Zeng N., Fusion Algorithm of the Improved A* Algorithm and Segmented Bézier Curves for the Path Planning of Mobile Robots. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. , High Altitude Balloon, PhD diss., Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2020.

- Hassani, S. , Dackermann, U.A., Systematic Review of Advanced Sensor Technologies for Non-Destructive Testing and Structural Health Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Giesen, N.; Steele-Dunne, S.C. , Jansen, J., Hoes, O., Hausner, M.B., Tyler, S., Selker, J., Double-Ended Calibration of Fiber-Optic Raman Spectra Distributed Temperature Sensing Data. Sensors 2012, 12, 5471–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D. , Zhou G., Estimation of Soil Moisture from Optical and Thermal Remote Sensing: A Review. Sensors 2016, 16, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicioni, G. , De Angelis A., Janeiro F.M., Ramos P.M., Carbone, P., Battery Impedance Spectroscopy Embedded Measurement System. Batteries 2023, 9, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. , Qu M., Liu X., Cui Y., Hu H., Li Q., Jin M., Xian J., Nie Z., Zhang C., Three-in-One Portable Electronic Sensory System Based on Low-Impedance Laser-Induced Graphene On-Skin Electrode Sensors for Electrophysiological Signal Monitoring. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2201735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. , Yang D., Li M., Ren X., Yuan X., Tang L., Wang X., Liu S., Yang M., Liu Y., Yang M., Design and Verification of Piano Playing Assisted Hand Exoskeleton Robot. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J. , Monahan R., Casey K., Power Consumption Profiling of a Lightweight Development Board: Sensing with the INA219 and Teensy 4.0 Microcontroller. Electronics 2021, 10, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroşan, A. , Constantin G., Gîrjob C.E., Chicea A.L., Crenganis, M. Real time data acquisition of low-cost current sensors acs712-05 and ina219 using raspberry pi, daqcplate and node-red. Proceedings in Manufacturing Systems 2023, 18, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K. , Li Z. Yang C., Design of Battery System of Emergency Power Supply for Auxiliary Fan in the Coal-Mine, International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems Engineering (CASE), Singapore 2011, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Guo C-Y., Lin T-L., Hsieh T-L., A Solar-Rechargeable Radiation Dosimeter Design for Radiation Hazard Zone Located with LoRa Network. Quantum Beam Sci. 2022, 6, 27. [CrossRef]

- Stoica, D. , Gmal Osman M., Strejoiu C. V., Lazaroiu G., Exploring Optimal Charging Strategies for Off-Grid Solar Photovoltaic Systems: A Comparative Study on Battery Storage Techniques. Batteries 2023, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanoor, N.S. , Yamanoor S., High quality, low cost education with the Raspberry Pi, IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), San Jose, CA, USA, 2017, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Sunehra, D. , Jhansi B., Sneha R., Smart Robotic Personal Assistant Vehicle Using Raspberry Pi and Zero UI Technology, 6th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Maharashtra, India, 2021, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Schwart, M. , Building Smart Homes with Raspberry Pi Zero, Packt Publishing Ltd. 2016.

- Alarcón-Paredes, A. , Francisco-García V., Guzmán-Guzmán I.P., Cantillo-Negrete J., Cuevas-Valencia R.E., Alonso-Silverio G.A., An IoT-based non-invasive glucose level monitoring system using raspberry pi. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, G. The official Raspberry Pi Beginner’s Guide: How to use your new computer, 5th Edition, Raspberry Pi Press 2023.

- Janakiram, S. , Babu M., Jain S., Rai R., Mohan R., Safonova M., Murthy J., Development Of Raspberry Pi-based Processing Unit for UV Photon-Counting Detectors. Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation arXiv:2401.01443 or arXiv:2401.01443v2. 2024, 01443v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sona,G. Sona,G., Passoni D., Pinto L., Pagliari D., Masseroni D., Ortuani B., Facchi A., UAV multispectral survey to map soil and crop for precision farming applications. The international archives of the photogrammetry. remote sensing and spatial information sciences 2016, 41, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alganci, U. , Besol B., Sertel E., Accuracy Assessment of Different Digital Surface Models. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. , Rhee S., Kim T., Digital Surface Model Interpolation Based on 3D Mesh Models. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. , Deng L., Lu H., An improved LAI estimation method incorporating with growth characteristics of field-grown wheat. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanyapraneedkul, J. , Muramatsu K., Daigo M., Furumi S., Soyama N., Nasahara K.N., Muraoka H., Noda H.M., Nagai S., Maeda T., Mano M., Misoguchi Y., A Vegetation Index to Estimate Terrestrial Gross Primary Production Capacity for the Global Change Observation Mission-Climate (GCOM-C)/Second-Generation Global Imager (SGLI) Satellite Sensor. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 3689–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.L.A. , Macie, G.M., Siquieroli A.C.S., Luz J.M.Q., Gallis R.B.d.A., Assis P.H.d.S., Catão H.C.R.M., Yada R.Y., Vegetation Indices for Predicting the Growth and Harvest Rate of Lettuce. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo Thi, D. , Ha N.T.T., Tran Dang Q., Koike K., Mai Trong N., Effective band ratio of landsat 8 images based on VNIR-SWIR reflectance spectra of topsoils for soil moisture mapping in a tropical region. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z. , Chen S., Yin T., Chavanon E., Lauret N., Guilleux J., Gastellu-Etchegorry J.P., Using the negative soil adjustment factor of soil adjusted vegetation index (SAVI) to resist saturation effects and estimate leaf area index (LAI) in dense vegetation areas. Sensors 2021, 21, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H. , Cheng T., Li D., Zhou X., Yao X., Tian Y., Zhu, Y., Evaluation of RGB, color-infrared and multispectral images acquired from unmanned aerial systems for the estimation of nitrogen accumulation in rice. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornacca, D. , Re, G., Xiao W. Evaluating the best spectral indices for the detection of burn scars at several post-fire dates in a mountainous region of Northwest Yunnan, China. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A. , Qing S., Bao Y., Na L., Bao Y., Liu X., Wang C., Short-term effects of fire severity on vegetation based on sentinel-2 satellite data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, A.I. , Zhao A., Li L., Sakiliba S.K., Low-cost IoT-based sensor system: A case study on harsh environmental monitoring. Sensors 2020, 21, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goumopoulos, C. , A high precision, wireless temperature measurement system for pervasive computing applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiyadi, E. , Wati A., Hamzah Y., Umar L. Simple IV acquisition module with high side current sensing principle for real time photovoltaic measurement. Journal of Physics: Conference Series IOP Publishing. 2020, 1528, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyawati, F.Y., Harjunowibowo, D., Fauzi, A., Utomo, B., Harmanto, D., Calibration and Validation of INA219 as Sensor Power Monitoring System using Linear Regression. AIUB Journal of Science and Engineering (AJSE) 2023, 22, 240–249. [CrossRef]

- Athanasadis, C. , Doukas D., Papadopoulos T., Chrysopoulos A., A scalable real-time non-intrusive load monitoring system for the estimation of household appliance power consumption. Energies 2021, 14, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudhair, A.B. , Hussein F.I., Obeidi M.A., Creating a LabVIEW Sub VI for the INA219 sensor for detecting extremely low-level electrical quantities. Al-Khwarizmi Engineering Journal 2023, 19, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, J. , Rawat A., Deb D., Multiple drone navigation and formation using selective target tracking-based computer vision. Electronics 2021, 10, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. , Lu H., Hwang S.H., Three-Dimensional Indoor Positioning Scheme for Drone with Fingerprint-Based Deep-Learning Classifier. Drones 2024, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamate, M.A. , Pupaza C., Nicolescu F.A., Moldoveanu C.E., Improvement of hexacopter UAVs attitude parameters employing control and decision support systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, T. , Starek M. J., Berryhill J., Quiroga C., Pashaei M., Simulation and characterization of wind impacts on UAS flight performance for crash scene reconstruction. Drones 2021, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroftei D., De Cubber G., Bue S L., De Smet H., Quantitative Assessment of Drone Pilot Performance, preprints.org 2024, 2024071957. [CrossRef]

| Database | Period | |||

| 2010-2015 | 2015-2020 | 2020-2024 | Papers | |

| Google scholar1 | 85 | 362 | 1190 | 1470 |

| IEEE Xplore | 0 | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Springer Link | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| ACM Digital Library | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Description | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Output voltage | 5 V |

| Charger | 5 V |

| Control bus | I2C |

| Battery | 803040 Li-po 1000mAh 3.7 V |

| Mounting hole size | 3 mm |

| Dimensions | 65x30 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).