1. Introduction

Sustainable urban development has been seriously challenged by several unsustainable land-use practices in the last decades, like urban sprawl or the spread of derelict (and often vacant) land, the so-called brownfield sites. Brownfields, defined as previously developed land that was occupied by industrial, railway, military, institutional or commercial functions but are no longer in use and often carrying the risk of contamination, present significant challenges, but at the same time also opportunities for contemporary urban development [

1,

2,

3]. In Western Europe and the United States, the emergence of brownfields is usually linked with the post-Fordist economic transition that became especially prevalent in the 1960s and 70s. The phenomenon was driven by deindustrialization and the decline of the Fordist economy, which reshaped urban landscapes and left many industrial, transport and commercial sites abandoned [

4].

In Central and Eastern Europe, the appearance of brownfield sites in cities followed a different trajectory, as state-socialism from political purposes maintained outdated industrial production and low-quality services until the late 1980s [

5]. Only after the collapse of state-socialist system in 1989-90 could deindustrialization and economic transformation evolve in the region as an outcome of the transition from centrally planned economies to a market-based system [

6,

7,

8,

9]. At the same time, due to the dismantling of the Iron Curtain and the end of the Cold War, successive demilitarization and downsizing of the armed forces took place leaving many military sites abandoned [

10]. This was also the case in Hungary, where after World War II the socialist state designated vast areas for industrial and military purposes, mostly in major cities, resulting in large complexes dedicated to production, transportation or defense [

11]. After 1989, many of these sites became obsolete and unused, leaving behind extensive industrial, transport, and military brownfields.

Among the various types of brownfields, military brownfields deserve special attention due to their unique function, physical characteristics and related environmental challenges [

12,

13]. This is especially the case in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), in countries lying between the boundaries of the former Iron Curtain and the Soviet Union, where excessive military infrastructure was developed during the Cold War. After the end of the Cold War as part of the demilitarization process large number of military brownfields emerged, mainly in cities. In this process two distinct phases could be distinguished. The first phase was primarily between 1989 and 1995 and involved countries lying outside the Soviet Union but belonging to the Soviet sphere of influence (e.g., German Democratic Republic, Czechoslovakia, Hungary). Following the end of the Cold War and the political transformations of 1989-90, approximately 500,000 Soviet troops were withdrawn from CEE, leaving behind extensive military properties [

14,

15]. These sites, including garrisons, airbases and associated infrastructure, were taken over by the national governments.

The second phase followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 when Soviet forces were gradually withdrawn also from the newly independent states from the mid-1990s. This phase was also characterized by military restructuring undertaken by the newly independent nation-states, involving the downsizing and reorganization of their armed forces [

14]. As a result, many former military properties with well-established infrastructure were abandoned and became brownfields in the Eastern half of Europe [

16].

The cleaning up military brownfields and the conversion of former military sites into new livable areas of cities is far from easy but a rather complex process [

12,

13,

17,

18]. The main objective of this paper is to investigate the level and forms of rehabilitation of former Soviet military sites in Hungary, and to analyze the current level of investment vs. disinvestment in space, giving an answer to the question of whether these sites can be seen as a suitable tool for combating urban sprawl, or on the contrary, they rather generate further sprawl in urban areas.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses existing works that focus on the definition and main features of military brownfields in the urban studies literature with special attention to the challenges regarding their redevelopment. The third section describes the applied research methods. A section then follows with the main research findings, depicting the various types of military brownfields, their generations, and the new functions after redevelopment. Finally, we present our conclusions, discuss their wider implications, highlight the limitations of the research, and explore possible future work in the field.

2. Literature Review

According to the literature, military brownfields – encompassing former military barracks, training grounds, airfields, and other facilities – differ considerably from other types of brownfields in legal, environmental, and urban geographical terms, therefore, they deserve special attention and their potential for urban regeneration must be differentiated from other types of brownfields [

19,

20]. Many studies have demonstrated that the regeneration of military brownfields involves addressing various distinct challenges that must be carefully identified and thoroughly resolved in each case [

15,

16,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Each military brownfield is unique, and each site is likely to present distinct architectural features, sometimes with buildings that are symbolic of the history of the city and the country or region where it is located. Many of these former military sites and buildings hold not only historical significance but also possess considerable architectural and emotional value which can limit rehabilitation options and require careful consideration regarding the possible new uses [

22,

23]. The requirements towards preservation often create complexity and additional costs for regeneration, where the well-preserved buildings, as an architectural heritage site, may have the potential to become a key tourist attraction for a city [

24]. Thus, the rehabilitation of military brownfields means not only potentials for the development of a city and its region but, at the same time, causes challenges as far as the preservation of its historical or cultural elements concerned under the contemporary demands of urban growth [

21,

25].

Another challenge is that military brownfields often cover extensive areas with complex urban structures, including residential buildings, warehouses, technical facilities, or training grounds [

26,

27]. This is important to consider, because the original use of a site also significantly influences its potential future utilization after regeneration. For instance, residential buildings of former military barracks have often been designated for housing function in the future [

28]. However, many of the former residential buildings were demolished and replaced by new, upmarket housing. This phenomenon has been especially prevalent in post-socialist CEE countries, where the most common use of revitalized military brownfields is residential function, which is commonly appreciated by the public [

21,

29,

30]. On the other hand, abandoned technical facilities, training grounds and airports pose greater challenges for planners and local decision-makers in finding optimal use, which often slows down their regeneration process [

31]. According to the literature after decontamination, such sites are often transformed into industrial parks, recreational and sports venues, or even wildlife reserves, contributing to environmental conservation and improving the quality of life for the surrounding communities [

32,

33].

Abandoned military sites frequently pose significant environmental challenges because they may be contaminated with hazardous substances such as fuels, chemicals, toxic, and radioactive waste that may endanger public health, or unexploded ammunitions, which need a costly and complex remediation process that often hinders the rehabilitation and new utilization of the site [

31,

34]. The most heavily contaminated areas tend to be former airports, missile bases, and weapon and fuel storage facilities. The cleaning up of these sites is often prolonged or only partially completed, which leads to the limited interest of potential investors [

14].

The question of ownership also often arise between national governments and local municipalities when military properties become abandoned. This was especially the case in CEE countries once the Soviet troops left. Such debate and the gradual establishment of the legal, planning and administrative frameworks also slowed down the regeneration of former Soviet military sites [

35]. In addition, the rehabilitation of military brownfields often requires time consuming negotiations between defense authorities, local governments, planning authorities and private developers [

36,

37]. In CEE countries, redevelopment efforts on such brownfield sites have often been characterized by top-down initiatives, as the properties were typically transferred to central government ownership [

38].

However, regeneration plans also often fail due to the lack of alignment with local needs and priorities, highlighting the importance of incorporating community interests into the planning and decision-making processes [

39]. Over time, it has become evident that regeneration strategies of military brownfield sites are most effective if they adopt a multidisciplinary approach, involving a wide range of professions and stakeholders [

40,

41,

42]. This process involves incorporating the interests and experiences of various stakeholders in order to reach a consensus regarding the objectives of the regeneration. This collaborative framework ensures that diverse perspectives and expertise contribute to the planning and implementation processes, ultimately leading to more successful and sustainable outcomes [

25].

Best practices worldwide have shown that despite the above-mentioned challenges, military brownfields also offer great opportunities for urban development [

43,

44]. Their size and strategic locations near transportation hubs or close to the city center make them ideal for various redevelopment projects, from mixed-use neighborhoods to large-scale single-function developments [

45]. These locations often provide a unique advantage in terms of accessibility and connectivity, making them highly attractive for investors and real estate developers. Regeneration of these sites can help mitigate pressure on the surrounding greenfield areas, preserving natural landscapes while managing the growing demand for housing and commercial spaces in urban settings [

46,

47,

48]. Additionally, the redevelopment of military brownfields may offer socio-economic benefits for people, such as job creation, increased security, a livable environment, and accessibility to services [

42,

49]. Successful projects not only enhance local economies but also foster urban regeneration, reducing inequalities between urban cores and peripheries. By active community involvement and aligning redevelopment efforts with local needs, these projects can become catalysts for broader urban renewal [

50].

The challenges and opportunities raised by military brownfields also coincide with broader urban development issues, particularly the phenomenon of urban sprawl. The regeneration and redevelopment of military brownfield sites provide an opportunity and possible strategy for planners to mitigate urban sprawl, which has become dominant over the past five decades [

39], supporting more compact forms of urban development [

51,

52]. Redirecting investments away from greenfield developments and putting the emphasis on the reuse of previously developed land can pave the way for smarter, more sustainable urban growth [

53]. The strategic location of military brownfields (often near urban cores or along expanding peripheral axis) makes them key targets in managing and mitigating urban sprawl [

27,

53]. These sites offer valuable opportunities for strategies aimed at limiting urban sprawl with infill developments, providing a sustainable alternative to the limitless outward expansion of cities [

54].

2. Materials and Methods

This research aims to examine the relationship between the revitalization process of former Soviet military brownfields and urban sprawl in Hungary. The Soviet red army liberated Hungary and other CEE countries from Nazi occupation in the final stage of World War II in autumn 1944 (

Figure 1). But, due to the outbreak of the Cold War, they remained for the next nearly half a century and withdrew only in the summer 1991 [

14]. The exact number and location of Soviet military troops were not allowed to be disclosed due to confidentiality reasons, and publications that have appeared since their withdrawal provide significantly different data.

Based on archive materials, contemporary news reports the first reliable study appeared only in 2013 which provided a detailed database of former Soviet military sites in Hungary containing 349 military brownfields in the country [

55]. However, a recent study found that in some cases the exact location of Soviet military brownfields could not be identified properly (e.g., former military training grounds that became vegetated areas in the meantime) or their size was too small, and they could not be considered as independent military brownfields (e.g., smaller transmission tower) [

21]. The narrowed list of former Soviet military sites contained 135 records, which was the starting point for this research. Since the phenomenon of urban sprawl is characteristic mainly for larger cities or urban places, the database was further narrowed down and we considered only those Soviet military brownfields that are located in urban municipalities above 20,000 inhabitants. In the end, during the research, we analyzed the spatial impacts of 73 Soviet military brownfields.

After determining the geolocation and the size of the brownfield areas, the impact on urban sprawl was examined using the 1990 and 2018 CORINE Land Cover databases. The CORINE Land Cover database has been widely used to measure urban sprawl [

56]. Depending on the level of redevelopment of the former military brownfields and its relationship with urban sprawl, distinct types were defined into which all brownfields were classified. Common characteristics of the brownfield types were identified and their impacts on urban sprawl were assessed.

In addition to the quantitative methodology, in-depth interviews with local experts, decision- and/or policymakers were conducted who had an insight into the process of regeneration of the brownfields (or the lack of it), or sometimes even participated in it. The typology of sites based on land use data could be extended with a more in-depth analysis based on the qualitative information derived from the interviews. During the interviews, respondents highlighted the problems and difficulties associated with the regeneration of Soviet military brownfields, which provided an opportunity to define the main obstacles of larger redevelopment programs. Considering all these factors, the impact of the regeneration or the lack of it on the wider urban development and more specifically urban sprawl could not only quantitatively, but also qualitatively be assessed.

3. Results

The previous functions of the 73 Soviet military brownfields could be identified as former military barracks (i.e., buildings lodging soldiers and commanders extended by other facilities), warehouses (storing explosives, fuel etc.), airfields, training fields, radio stations, hospitals, and residential enclaves. The investigated military brownfields could be classified into three distinct types according to (i) the extent of regeneration, and (ii) the location of the site relative to the compact city (i.e., continuous urbanized areas). Sites that have not been redeveloped yet were labeled as ‘intact’. Those fully or partially redeveloped were divided further into two sub-groups: those lying within the boundaries of the compact city (‘compact’) or outside (‘peripheral’). The relationship of sites belonging to different categories with urban sprawl was then carefully analyzed.

3.1. Intact Sites

We identified 12 military brownfields where redevelopment has not taken place since the withdrawal of the Soviet army, and the sites have remained unattractive for potential investors. Typically, these sites still have their original buildings, but in very obsolete conditions, some parts of the infrastructure have been dismantled while the remediation of the site is still missing. A previous study showed that intact military brownfields in Hungary are concentrated mainly in smaller towns and villages, at lower levels of the settlement hierarchy, reflecting the relevance of the size of the municipality and its budgetary potential regarding redevelopment.

The geographical location of the intact sites deserves special attention, two-thirds of them are located outside the compact city (i.e., urbanized areas) far from the city center, with no or limited access to the existing transport network. Such sites were usually developed by the Soviet army in the 1960s and 70s and functioned as airfields, ammunition depots, and radar stations. This group of military brownfields has no direct impact on urban sprawl as being unattractive for investors they have not served as magnets for new developments (

Figure 2).

An example for the intact military brownfields is the ammunitions depots and training ground of the Soviet army in Csalánosi-forest near Kecskemét, a second-tier city in Hungary with ca. 115 thousand inhabitants. The area was originally used for shooting exercises, hand grenade throwing etc. and went through a clean-up program in 2002. Some part of the site is used now as a forest, but the former ammunition depots are intact and the nuances of the landscape with artificial hills still reflect the original military use.

However, we also found intact military brownfields in the densely built areas of cities, mostly in Budapest and larger cities. The indirect impact of such sites on urban sprawl is obvious, instead of their reuse and rehabilitation the cities expanded outside the continuously built-up areas and consumed greenfield areas. A good example of such sites is the Dózsa György-barracks in Szombathely, a major city in Western Hungary with around 80 thousand inhabitants (

Figure 3). The barracks were built in 1889 and hosted a section of the Hungarian cavalry regiment until the early 1950s when they were occupied by the Soviet troops. After their withdrawal in 1989 the buildings – which are part of the national cultural heritage – remained empty for decades and deteriorated visibly.

A common feature of the property relations of this type of sites is that they are owned by the local municipalities which try to sell them from time to time, but no investors are found. The main reasons behind the failed transactions are usually the high estimated costs of remediation and the strict regulations regarding the forms of regeneration set by heritage protection. To find some solutions for the utilization of such sites local governments often designate temporary functions (e.g., weekly market, car park).

3.2. Redeveloped Sites in the Compact City (‘Compact’)

We identified 33 fully or significantly redeveloped military brownfields formerly used by the Soviet army that are embedded in the continuously built-up areas of cities. These facilities were very often developed by the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in the late 19th century and were taken over by the Soviet army after WWII. When these barracks were erected they were located at the edge of the compact city, but in the subsequent half a century, they became integral part of the inner cities due to urban growth. Moreover, they possess considerable architectural and emotional value, therefore, their redevelopment was relatively easy and successful. Examples are the Frigyes-barracks in Győr Western Hungary (

Figure 4).

Frigyes-barracks shown in the Figure were completed in 1896 by the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and served the needs of the Hungarian army. After the 1956 revolution, it was confiscated by the Soviet army. After more than three decades the property was transferred to the local municipality in 1989. The Soviet troops left behind the buildings in very run-down conditions but the site became part of heritage protection in 2001. After long negotiations, the site was bought by the Austrian Leier International company specializing in building materials manufacturing in 2005. Since then the six buildings located on 3 hectares in the center of Győr have been completely renovated and converted to offices (giving home to the Hungarian headquarters of the company) and high-quality residential spaces. The project can be considered very successful and it has contributed to the extension of the city center of Győr.

The rehabilitation of former military sites in the compact city was relatively successful and their integration into the urban fabric was completed between 1990 and 2018. Nearly all of them are located in larger cities of Hungary in the upper levels of urban hierarchy including Budapest. The success of their regeneration and integration into urban life largely depends on their proximity to the city center, the architectural quality of the buildings, and the policy of the local municipality.

3.3. Redeveloped Sites Outside the Compact City (‘Peripheral’)

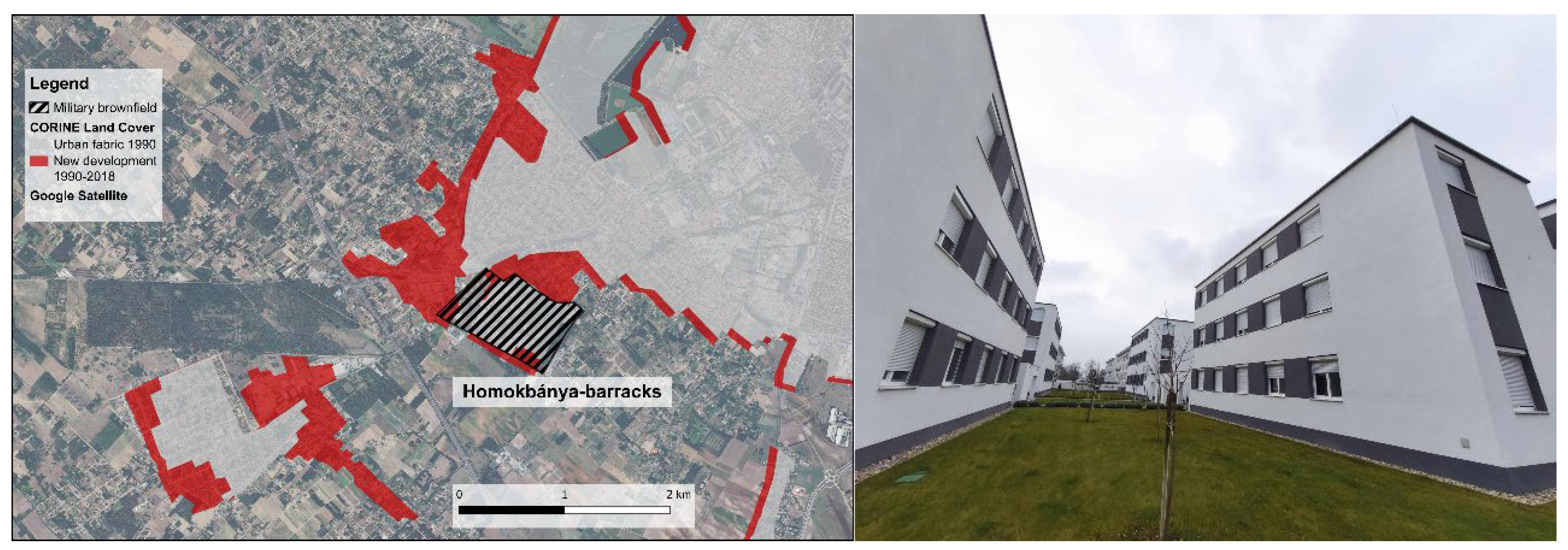

We identified 28 former Soviet military sites that were located outside the continuous urban fabric (i.e., compact city) in 1990 and became completely redeveloped by 2018. These military installations were usually developed in the 1950s outside the inhabited areas of cities along main radial roads connecting the cities to the national highway system. The 2018 CLC data confirmed that the spatial expansion of the artificial surfaces of cities reached these sites in the meantime and often overgrown them. Data confirm that 40% of the investigated military sites in our sample actively contributed to urban sprawl. Even though Budapest, the capital city of Hungary, has been characterized by rapid urban sprawl in the last three decades [

47], we have not found any military brownfield that would have contributed to the process. Military brownfields with peripheral locations generated urban sprawl mainly around second-tier cities.

An example of the military brownfields generating urban sprawl is the former Homokbánya-barracks in Kecskemét. The site was originally developed for the Hungarian People’s Army in 1950, later it was taken over and massively developed by the Soviet army. After the withdrawal of the Soviet troops, the site was gradually redeveloped by private investors due to the incentives of the local municipality. The original buildings were renovated and converted to modern housing, the newly arriving residents were supplied with public transport and communal facilities (school, kindergarten, etc.). The project attracted new investments like a gated community or the student dormitory of the local university. According to the local plans, the newly evolving Homokbánya neighborhood would serve as a community center in the future on the western side of the city with mixed land use involving also new functions (business, commerce, etc.).

Figure 5.

The former Homokbánya-barracks near Kecskemét.

Figure 5.

The former Homokbánya-barracks near Kecskemét.

A deeper analysis of the newly evolving urbanized surfaces linked to former military sites outside the compact city shows that the most common functions are residential, business, and logistics. Due to their excellent location such sites were very much favored by investors seeking locations with good accessibility for their projects. In many cases, the site was converted to an upmarket housing compound, most often a gated community, which attracted further housing developments in the nearby green areas in the form of low-rise single-family homes, just like in the case of Homokbánya-barracks. The same applies if the military brownfield was successfully converted to a business park. In the subsequent years, other firms engaged in businesses or logistics settled in the area. Thus, the former Soviet military brownfields served as magnets for urban growth and land conversion in the peripheries of cities.

3.4. Generations of Former Soviet Military Sites

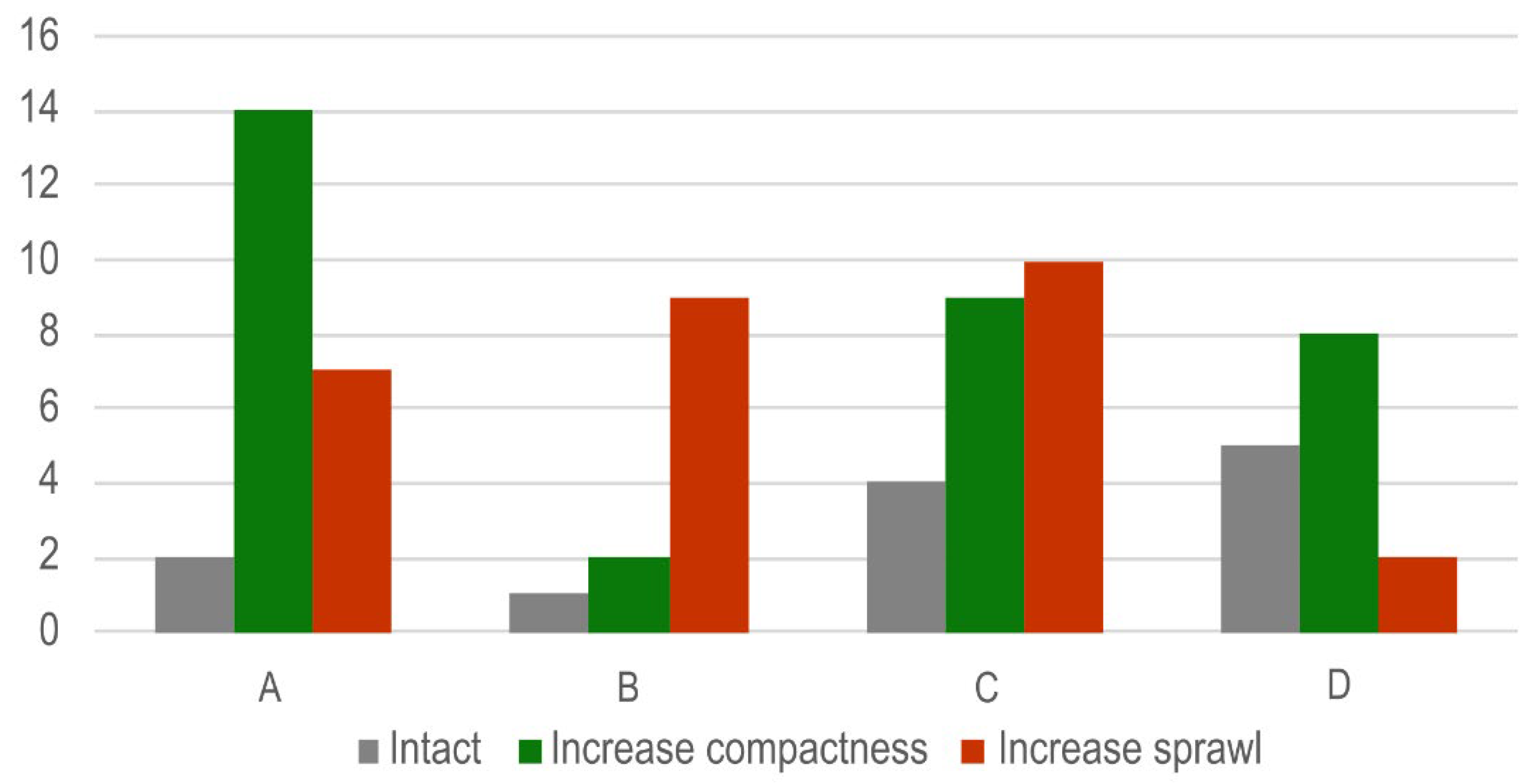

Regarding the age of their construction, geographical location and the level of transformation former Soviet military sites can be divided into four distinct types: (A) military land (mainly barracks) developed by the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy before World War I; (B) military installations originally built for the Hungarian People’s Army before the arrival of the Soviet troops; (C) military sites developed by the Soviet army after the 1950s, and (D) non-military urban facilities (e.g., hospitals, airfields, depots, residential buildings) developed by the Hungarian state and taken over by the Soviet army. The impacts of different generations of military brownfields are clearly demonstrated by

Figure 6.

Older military sites and properties designed for civic use (types A and D) rather enhanced dense development patterns and increased the compactness of cities after redevelopment, whereas military installations put in place in the early years of communism by the Hungarian state or the Soviet army (types B and C) rather generated urban sprawl. The reasons behind this are not just the more peripheral location and bigger size of the latter groups, but also the weaker planning control and the higher demand of investors for cheaper land in the urban periphery [

7,

57].

3.5. Functions of the Reuse of Soviet Military Brownfields

The development potential and the functions of the reuse of military brownfields differ considerably as do their accessibility, the architectural quality of the buildings, and the land value. Therefore, the actual use of the military brownfields lying inside (‘compact’) and outside (‘peripheral’) the compact city was analyzed separately. Only the current use of military brownfields that have gone through regeneration since they were abandoned, was captured and analyzed.

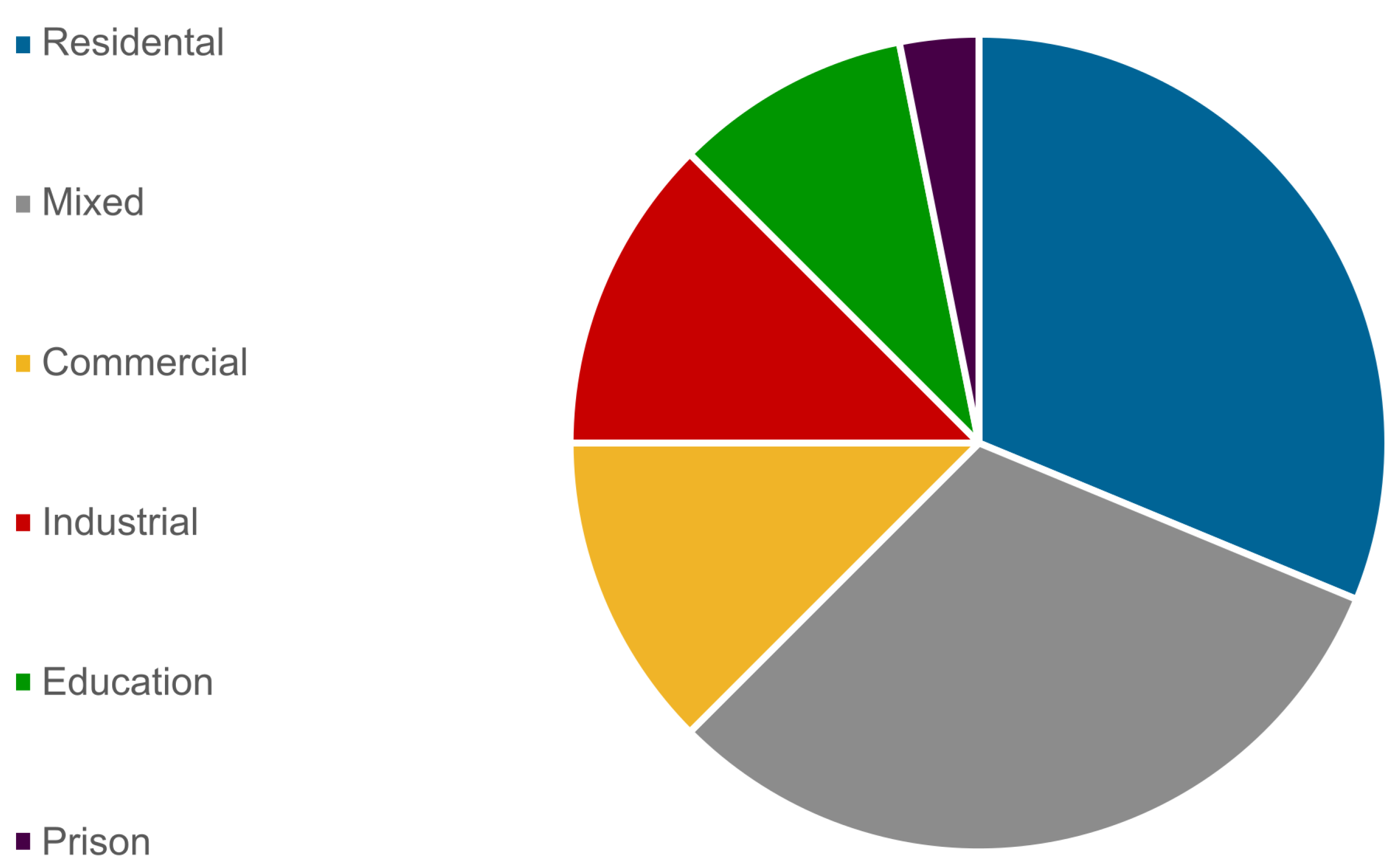

Most of the military brownfield sites embedded in the continuous urban fabric have been targets of local rehabilitation programs and they have become fully or significantly renovated by now, mainly due to their advantageous accessibility conditions, the existing urban infrastructure, and high real estate value. The dominant new functions of these sites are residential and mixed-use, followed by commercial and industrial uses (

Figure 7). Mixed-use developments usually comprise a combination of residential, commercial, and office spaces, whereas industry plays a subordinated role. The redevelopment of such sites has been successful since they have been favored by real-estate developers and various mixed-use projects of the public sector (local governments, central government). Local municipalities could use such sites as a catalyst for wider rehabilitation programs targeting specific neighborhoods or districts of a city. If the original buildings had architectural or historical values, the site could also be involved in heritage preservation programs subsidized by the national government and the EU.

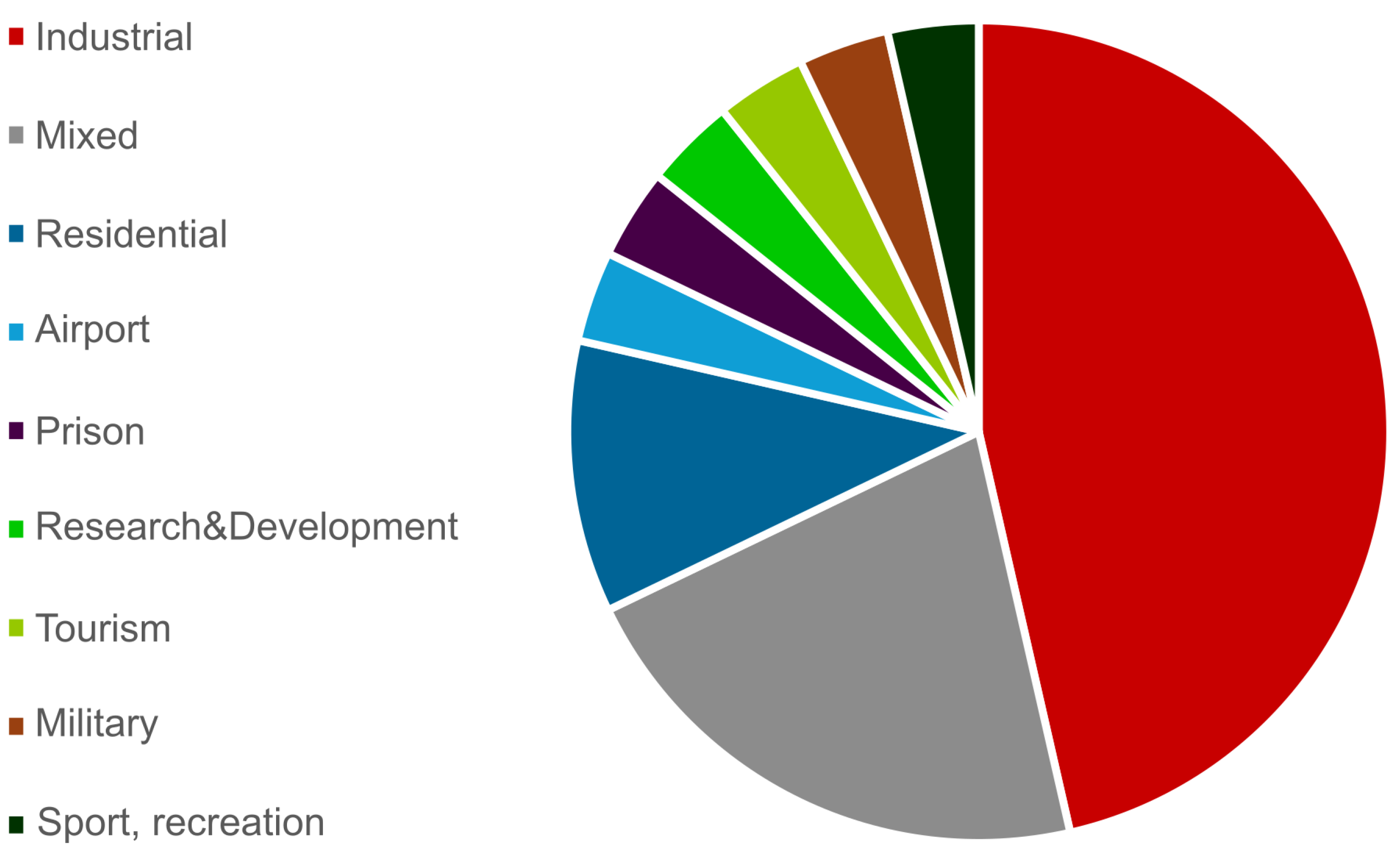

The redevelopment of ‘peripheral’ military brownfields has been less successful, many of them have been renovated only partially and are often disconnected from the wider urban environment. Also there is a high diversity of the new functions compared to the redeveloped sites in the compact city. The dominant function of their new use is industry, followed by mixed-use, usually comprising industrial and residential uses (

Figure 8). Residential function as single use only rarely comes to the fore, just like other functions, such as airport, R&D, leisure, etc. During their redevelopment industrial investors often buy additional agricultural land near the brownfield site, generating urban sprawl. This also applies to mixed-use developments where new housing projects have often been realized near new industries.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Nowadays, urban sprawl and the territorial expansion of derelict land, the so-called brownfields, are among the main challenges of sustainable urban development. This study links the two phenomena in its approach, and demonstrates the importance of brownfield regeneration in combating urban sprawl with special attention to military brownfields. Military brownfields are considered to be a special case in the wide spectrum of derelict and underused areas in cities due to their larger size, peripheral location, and contamination problems. However, military brownfields also offer unprecedented development opportunities for urban planners to restrict urban sprawl and stimulate the compact growth of cities through the otherwise complicated process of cleaning up and redevelopment [

21,

44].

Using a mix of quantitative (GIS) and qualitative (interviews) research methods this paper investigates the relationship between the redevelopment of former Soviet military sites and urban sprawl in Hungary. The country was occupied by the Soviet troops in the final phase of World War II who remained in the country until June 1991. During this period, they took away old military facilities built originally for the national army, developed new ones and confiscated properties in civilian use (e.g., hospitals, airports, office buildings). After the withdrawal of the Soviet army most of their facilities were abandoned, gradually dilapidated and became brownfields. The main question of this research was whether military brownfields can be tool for combating urban sprawl or they generate sprawl themselves.

The findings of the paper highlight the overall importance of military brownfield regeneration in urban sustainability, however, as it was shown, not all the redevelopment projects appear to be beneficial to densification objectives. Regeneration of military brownfields embedded in the built-up areas of cities can increase compactness, and attract new functions and residents to abandoned areas. They can also actively contribute to the wider regeneration strategies of local governments especially in run-down neighborhoods. However, a large number of military brownfields are located on the peripheries of urban areas. The regeneration of such sites, as it was demonstrated, may play a catalyst role in urban sprawl. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that local municipalities should make a careful strategic selection of military brownfield sites for redevelopment based upon their characteristics and location, as supported by the typology presented in this study together with socio-economic and risk factors.

The study also shed light on the relevance of local politics, how municipal governments perceive and handle the challenges caused by military brownfields. Abandoned military facilities left behind by the Soviet army were in most cases transferred from central government to municipal governments in the 1990s. The local political and budgetary conditions as well as planning objectives very often had a great influence on the success of the regeneration of military brownfield sites and their wider impact on urban land use. Cities where the municipal government actively supported the remediation and integration of military brownfields to the built-up area of the city could use the rehabilitation process to promote densification. However, when the municipal government wanted to get rid of the problems caused by the newly acquired military brownfields and sold the properties to real-estate developers the rehabilitation often failed or discontinued, and the redevelopment projects often generated new investments in nearby sites inducing urban sprawl. Not only local will, but also budgetary conditions played a role in this process, because some municipalities were in desperate financial situation.

The limitations of our study are set by its geographical scope and methodology. We used only one country, Hungary from CEE, as a case study, however, we think that the urban challenges caused by the redevelopment of former military properties are rather similar worldwide. Regarding the methodology, in a follow-up research, other types of brownfields should also be investigated from a comparative perspective. Despite these limitations, we think that the results of this study provide a reference for future policy formulations in countries with similar geopolitical heritage as Hungary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and Z.K.; methodology, B.S. and T.K.; software, B.S.; validation, B.S. and T.K.; formal analysis, B.S.; investigation, B.S.; resources, Z.K.; data curation, B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S.; writing—review and editing, T.K. and Z.K.; visualization, T.K.; supervision, T.K. and Z.K.; project administration, Z.K.; funding acquisition, Z.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA) Grant Agreement No. K135546, and the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of the Ministry of Innovation and Technology, Hungary, under the TKP2021-NVA-09 funding scheme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Jacek, G.; Rozan, A.; Desrousseaux, M.; Combroux, I. Brownfields over the Years: From Definition to Sustainable Reuse. Environmental Reviews 2022, 30, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; De Sousa, C.; Tiesdell, S. Brownfield Development: A Comparison of North American and British Approaches. Urban Studies 2010, 47, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alker, S.; Joy, V.; Roberts, P.; Smith, N. The Definition of Brownfield. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2000, 43, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunc, J.; Martinát, S.; Tonev, P.; Frantál, B. Destiny of Urban Brownfields: Spatial Patterns and Perceived Consequences of Post-Socialistic Deindustrialization. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences 2014, 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Trócsányi, A.; Karsai, V.; Pirisi, G. Formal Urbanisation in East-Central Europe. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2024, 73, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, I.; Dumitrică, C.; Dumitrașcu, M.; Mitrică, B.; Dumitrașcu, C. Urban Development and the (Re)Use of the Communist-Built Industrial and Agricultural Sites after 1990. The Showcase of Bucharest–Ilfov Development Region. Land (Basel) 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R.; Mitrică, B.; Cercleux, A.-L.; Grigorescu, I.; Hardi, T. Deindustrialization, Tertiarization and Suburbanization in Central and Eastern Europe. Lessons Learned from Bucharest City, Romania. Land (Basel) 2023, 12, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, T. A Geographic Approach to the Transformation Process in European Post-Communist Countries. In A Geographic Approach to the Transformation Process in European Post–Communist Countries; Wydawnictwo Bernardinum: Gdynia-Pelplin, 2006; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.P.; Szelényi, I. 10. Post-Communist Economic System. In The Handbook of Economic Sociology, Second Edition; Princeton University Press, 2010; pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. What Factors Guide the Recent Spanish Model for the Disposal of Military Land in the Neoliberal Era? Land use policy 2023, 134, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Relley, Z.E. From Totalitarian Central Planning to a Market Economy: Decentralization and Privatization in Hungary. Journal of Private Enterprise 2001, 17, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzini, D.; Vani, M. Planning for Military Real Estate Conversion: Collaborative Practices and Urban Redevelopment Projects in Two Italian Cities. Urban Res Pract 2014, 7, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, E.; Severcan, Y.C. Assessing User Preferences Regarding Military Site Regeneration: The Case of the Fourth Corps Command in Ankara. Cities 2022, 129, 103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrttinen, H. Base Conversion in Central and Eastern Europe 1989-2003. BICC 2003, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Glintić, M. Revitalization of Military Brownfields in Eastern and Central Europe. Strani pravni život 2015, 1, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hercik, J.; Szczyrba, Z. Post-Military Areas as Space for Business Opportunities and Innovation. Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society 2012, 19, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assylkhanova, A.; Nagy, G.; Morar, C.; Teleubay, Z.; Boros, L. A Critical Review of Dark Tourism Studies. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2024, 73, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Laprise, M.; Lufkin, S. Urban Brownfields: Origin, Definition, and Diversity. In Neighbourhoods in Transition. The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, 2022; pp. 7–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hercik, J.; Šimáček, P.; Szczyrba, Z.; Smolová, I. Military Brownfields in the Czech Republic and the Potential for Their Revitalisation, Focused on Their Residential Function. Quaestiones Geographicae 2014, 33, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka-Bogusz, M. Innovative Use in Adaptation of Post Military Barrack Complexes. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference; SGEM: Sofia, June 20 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, B.; Kovalcsik, T.; Kovács, Z. Lessons of the Regeneration of Former Soviet Military Sites in Hungary. In Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine through Military Brownfields Redevelopment; Morar, C., Berman, L., Erdal, S., Niemets, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2024; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Morar, C.; Nagy, G.; Dulca, M.; Boros, L.; Sehida, K. Aspects Regarding the Military Cultural-Historical Heritage in the City of Oradea (Romania). Annales-Anali za Istrske in Mediteranske Studije - Series Historia et Sociologia 2019, 29, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevremovic, L.; Stanojevic, A.; Djordjevic, I.; Turnsek, B. The Redevelopment of Military Barracks between Discourses of Urban Development and Heritage Protection: The Case Study of Nis, Serbia. Spatium 2021, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka-Bogusz, M. The Genius Loci Issue in the Revalorization of Post-Military Complexes: Selected Case Studies in Legnica (Poland). Buildings 2022, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemets, L.; Sehida, K.; Babichev, A.; Subiros, J.V.; Morar, C.; Grama, V.; Kravchenko, K.; Telebienieva, I. Issues of the Military Brownfields in Ukraine: A Sustainable Development Perspective. In; 2024; pp. 83–95.

- Hercik, J.; Šimáček, P.; Szczyrba, Z.; Smolová, I. Military Brownfields in the Czech Republic and the Potential for Their Revitalisation, Focused on Their Residential Function. Quaestiones Geographicae 2014, 33, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matković, I.; Jakovcic, M. Conversion and Sustainable Use of Abandoned Military Sites in the Zagreb Urban Agglomeration. Hrvatski geografski glasnik/Croatian Geographical Bulletin 2020, 82, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komár, A. The Problems of the Revitalisation and Reusing of Former Military Lands in Central and Eastern Europe. Geografie 1998, 103, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezentsev, K.; Niemets, L.; Sehida, K. Transforming Brownfields: Urban Renewal in Ukrainian Cities. In; 2024; pp. 289–299.

- Wendt, J.A.; Bógdał-Brzezińska, A. Historical Context and Political Conditions of Revitalization of Degraded Military Areas: Case Study “Garnizon” in Gdańsk. In; 2024; pp. 327–342.

- Jauhiainen, J. Conversion of Military Brownfields in Oulu. In Rebuilding the city. Managing the built environment and remediation of brownfields; Urban, V.D., Ed.; Baltic University Press, 2007; pp. 27–33.

- Havlick, D.G. Disarming Nature: Converting Military Lands to Wildlife Refuges*. Geogr Rev 2011, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.; Gallent, N.; Howe, J. Re-Use of Small Airfields: A Planning Perspective. Prog Plann 2001, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, B.; Stickel, J.; Vero, L.; Padar, I. Assessment and Remediation of Environmental Damage in the Abandoned Soviet Military Bases in Hungary. In Proceedings of the IAHS-AISH Publication; 1995; pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kádár, K. The Rehabilitation of Former Soviet Military Sites in Hungary. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2014, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaeen, S.; Clark, C. Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites; Bagaeen, S. , Clark, C., Eds.; Routledge, 2016; ISBN 9781315621784.

- Jauhiainen, J. Militarisation, Demilitarisation and Re-Use of Military Areas: The Case of Estonia. Geography 1997, 82, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seljamaa, E.-H.; Czarnecka, D.; Demski, D. “Small Places, Large Issues”: Between Military Space and Post-Military Place. Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 2017, 70, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, E.; Pesce, M.; Pizzol, L.; Alexandrescu, F.M.; Giubilato, E.; Critto, A.; Marcomini, A.; Bartke, S. Brownfield Regeneration in Europe: Identifying Stakeholder Perceptions, Concerns, Attitudes and Information Needs. Land use policy 2015, 48, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, A.; Miljus, M. The Regeneration of Military Brownfields in Serbia: Moving towards Deliberative Planning Practice? Land use policy 2021, 102, 105–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagaeen, S.G. Redeveloping Former Military Sites: Competitiveness, Urban Sustainability and Public Participation. Cities 2006, 23, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazia, C.; Catania, G.F.G.; Sortino, F. The Recovery of Disused Infrastructure and Military Areas in Spain and Italy, Contributions to the Regeneration of Territories. 2024, 107–122. [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites; Bagaeen, S. , Celia, C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Achieving Sustainability in Ukraine through Military Brownfields Redevelopment; Morar, C. , Berman, L., Erdal, S., Niemets, L., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2024; ISBN 978-94-024-2277-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hercik, J.; Szczyrba, Z. Post-Military Areas as Space for Business Opportunities and Innovation. Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society 2012, 19, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, C.A. Turning Brownfields into Green Space in the City of Toronto. Landsc Urban Plan 2003, 62, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, G.; Hutchison, N. Barriers to Affordable Housing on Brownfield Sites. Land use policy 2021, 102, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.; Craighill, P.; Mayer, H.; Zukin, C.; Wells, J. Brownfield Redevelopment and Affordable Housing: A Case Study of New Jersey. Hous Policy Debate 2001, 12, 515–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, R. Redeveloping the Redundant Defence Estate in Regions of Growth and Decline - Challenges for Spatial Planning; 2012; ISBN 9781409427414.

- Bagaeen, S. Framing Military Brownfields as a Catalyst for Urban Regeneration. In Sustainable Regeneration of Former Military Sites; Routledge, 2016; pp. 1–18.

- Csomós, G.; Szalai, Á.; Farkas, J.Z. A Sacrifice for the Greater Good? On the Main Drivers of Excessive Land Take and Land Use Change in Hungary. Land use policy 2024, 147, 107352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egedy, T.; Szigeti, C.; Harangozó, G. Suburban Neighbourhoods versus Panel Housing Estates – An Ecological Footprint-Based Assessment of Different Residential Areas in Budapest, Seeking for Improvement Opportunities. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin 2024, 73, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulić, O.; Krklješ, M. Brownfield Redevelopment as a Strategy for Preventing Urban Sprawl; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baing, A.S. Containing Urban Sprawl? Comparing Brownfield Reuse Policies in England and Germany. Int Plan Stud 2010, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, K. Funkcióváltás Szovjet Katonai Objektumok Helyén. Barnamezős Katonai Területek Újra-Hasznosítása Hat Magyar Megyeszékhelyen [Functional Change at the Location of Soviet Mili-Tary Sites. Reuse of Military Brownfields in Six Hungarian County Centers]. PhD Dissertation, University of Pécs: Pécs, 2013.

- Kovács, Z.; Farkas, Z.J.; Egedy, T.; Kondor, A.C.; Szabó, B.; Lennert, J.; Baka, D.; Kohán, B. Urban Sprawl and Land Conversion in Post-Socialist Cities: The Case of Metropolitan Budapest. Cities 2019, 92, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénzes, J.; Hegedűs, L.D.; Makhanov, K.; Túri, Z. Changes in the Patterns of Population Distribution and Built-Up Areas of the Rural–Urban Fringe in Post-Socialist Context—A Central European Case Study. Land (Basel) 2023, 12, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).