Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Development of CFE

1.1.1. Common Law and the Eighth Amendment

1.1.2. Landmark Supreme Court Cases

1.2. Empirical Legal Studies

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample Size

2.2. Data Collection, Coding, and Validation

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Case Background

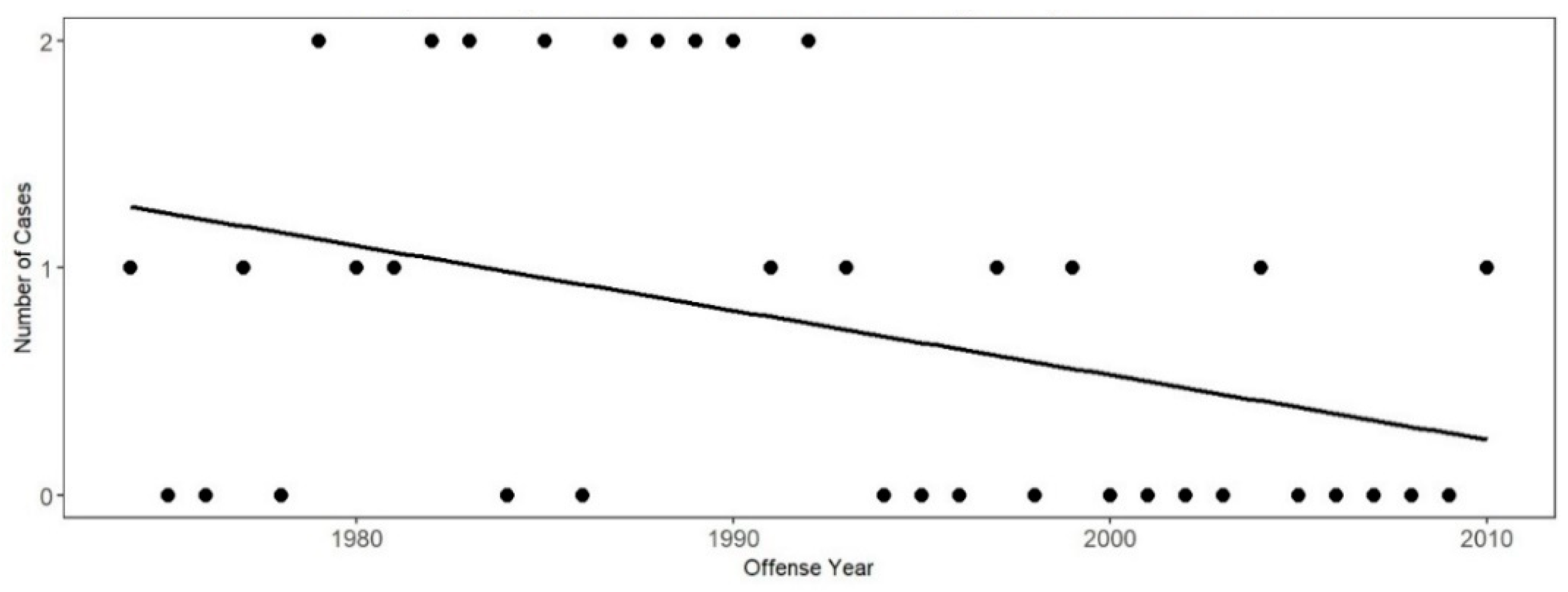

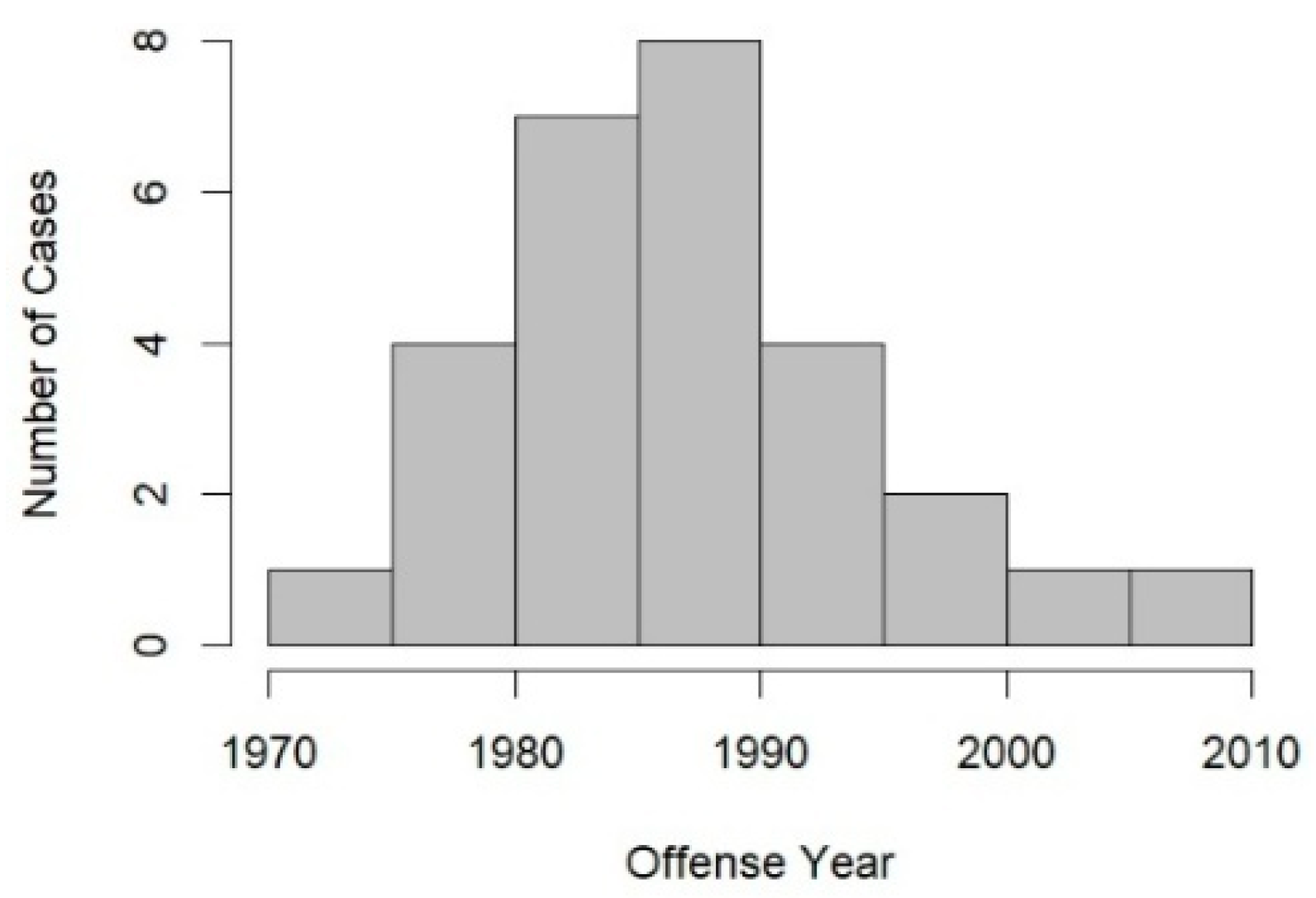

3.1.1. Offense Year

3.1.2. State

3.2. Claimant Demographics

3.2.1. Gender

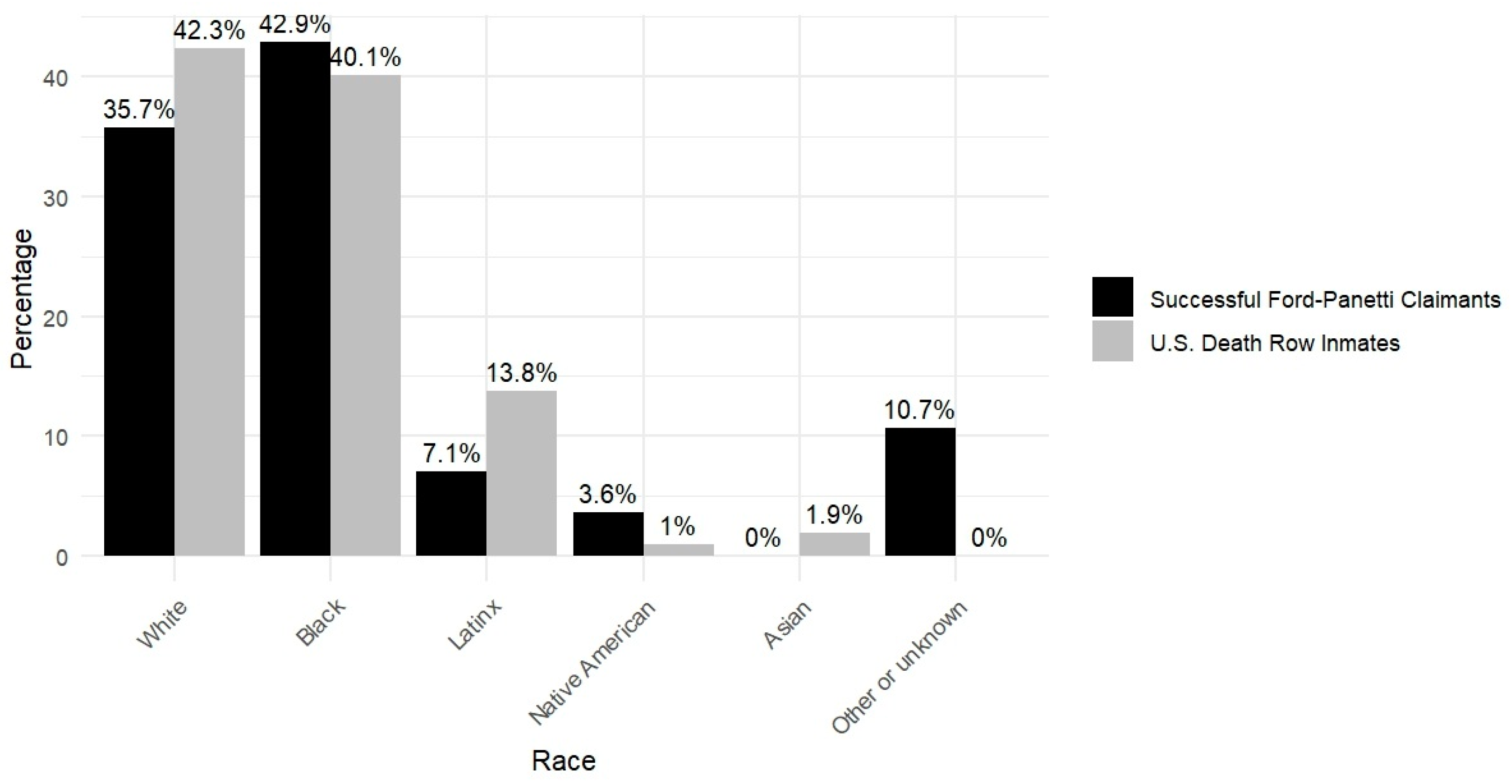

3.2.2. Race

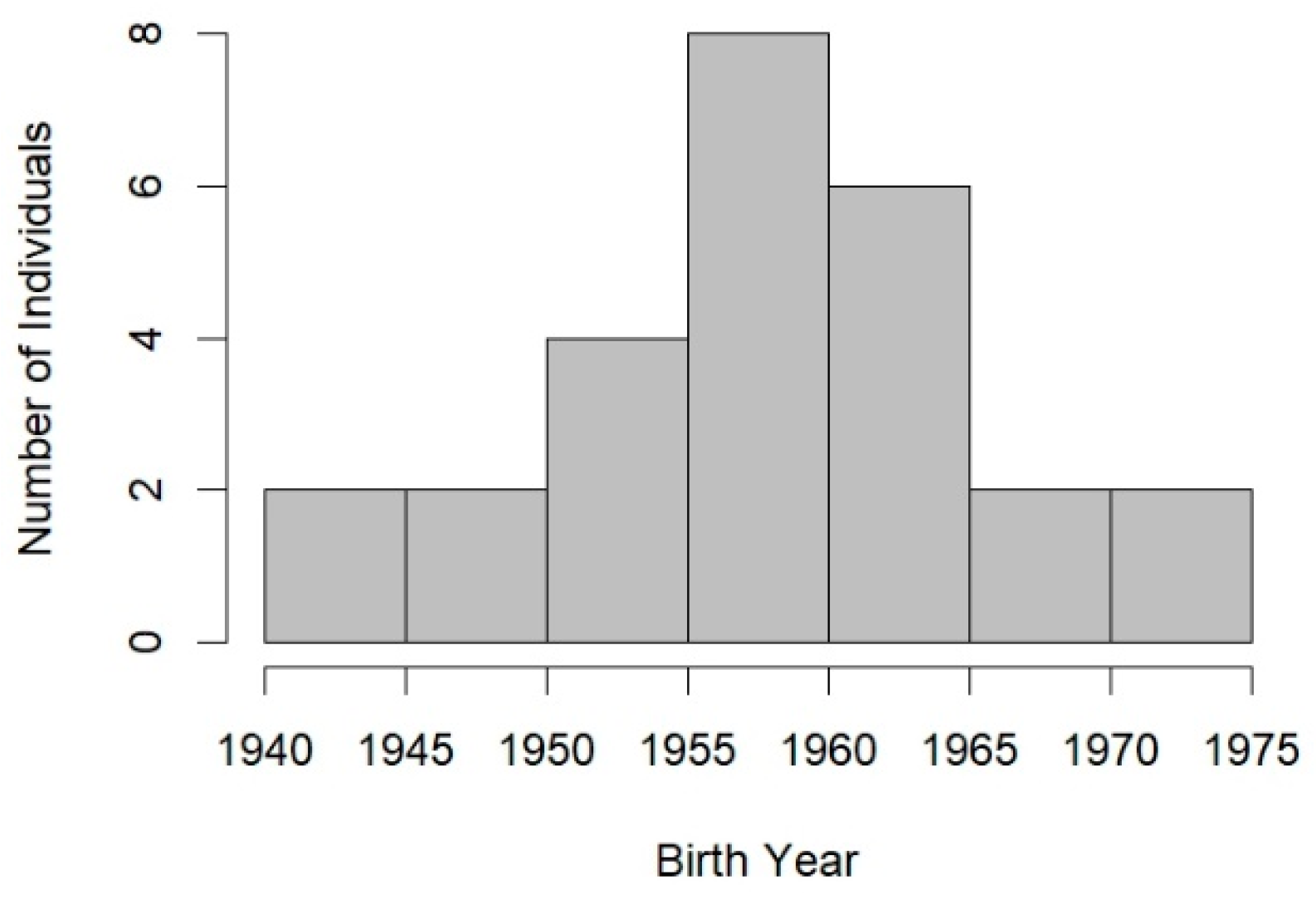

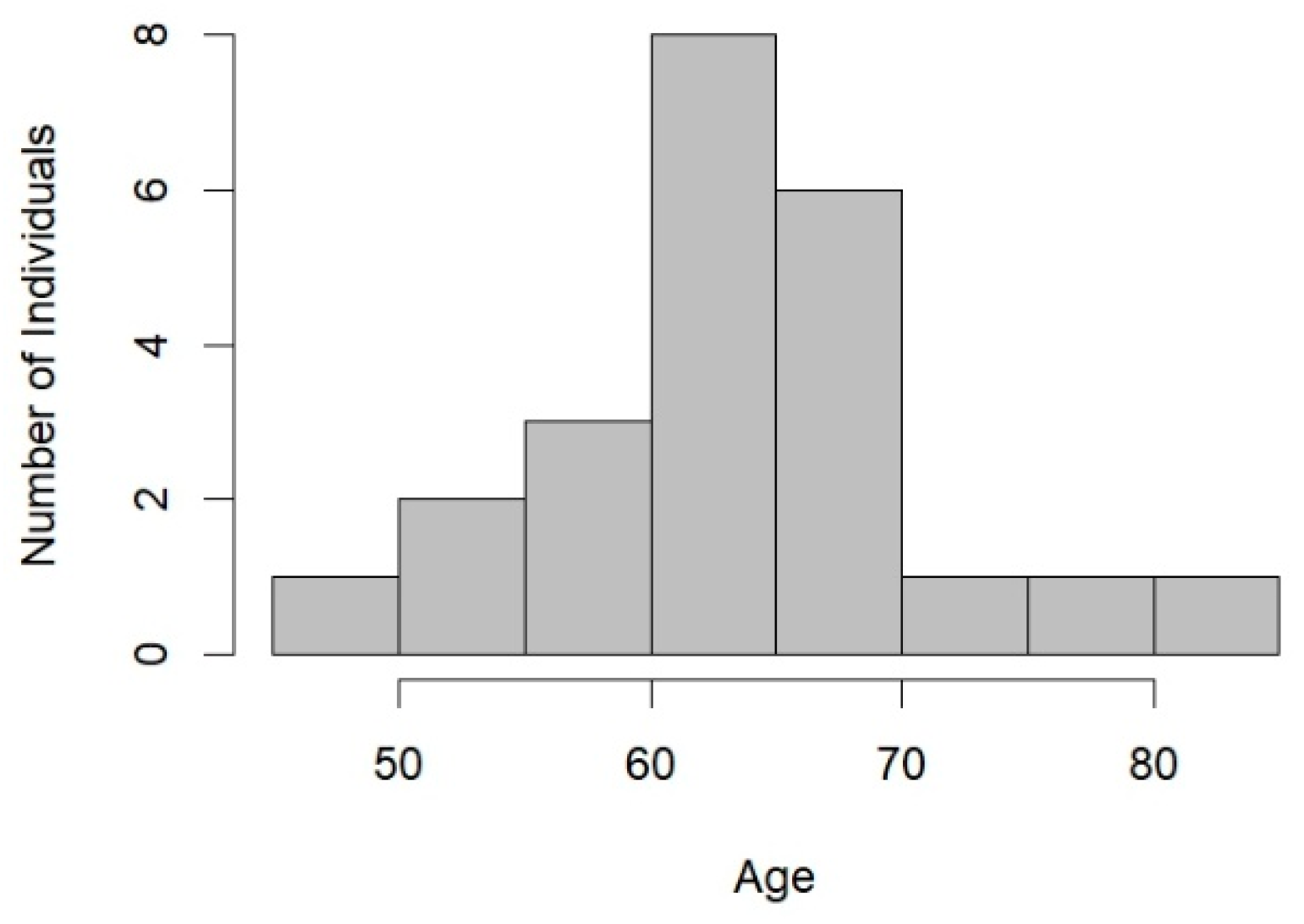

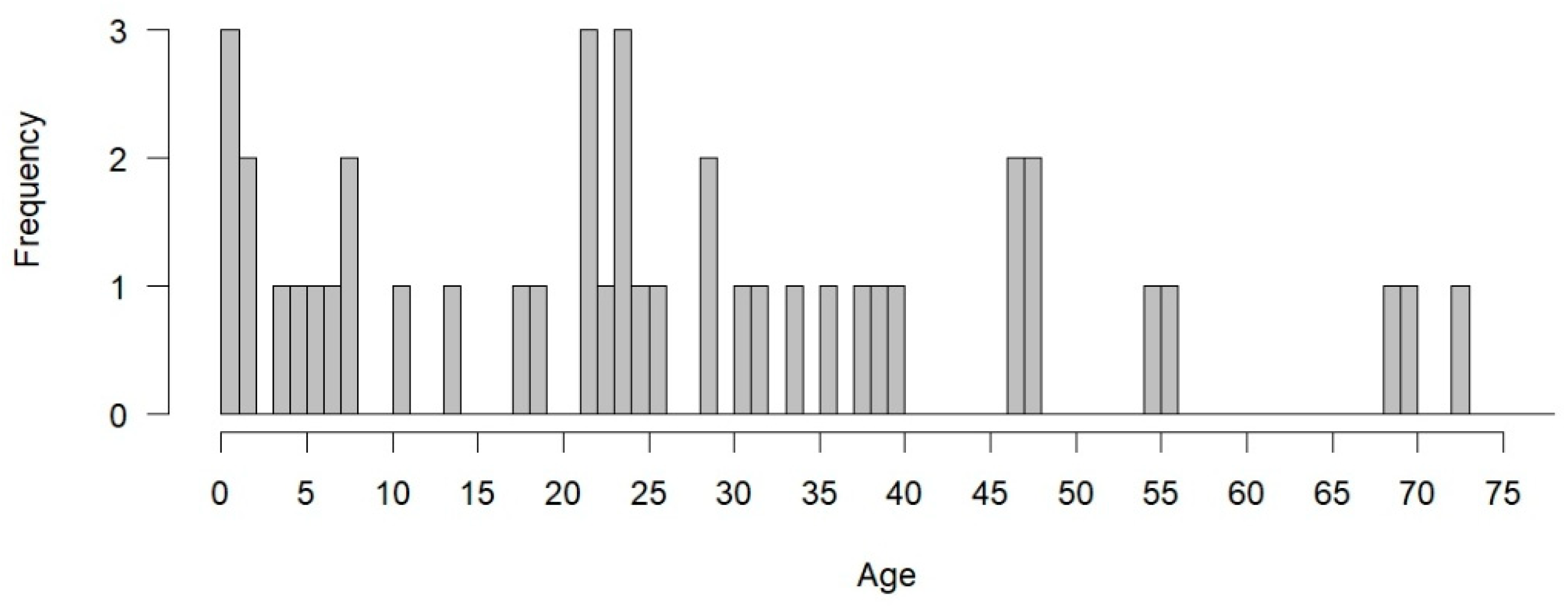

3.2.3. Age, Time on Death Row, and Current Status

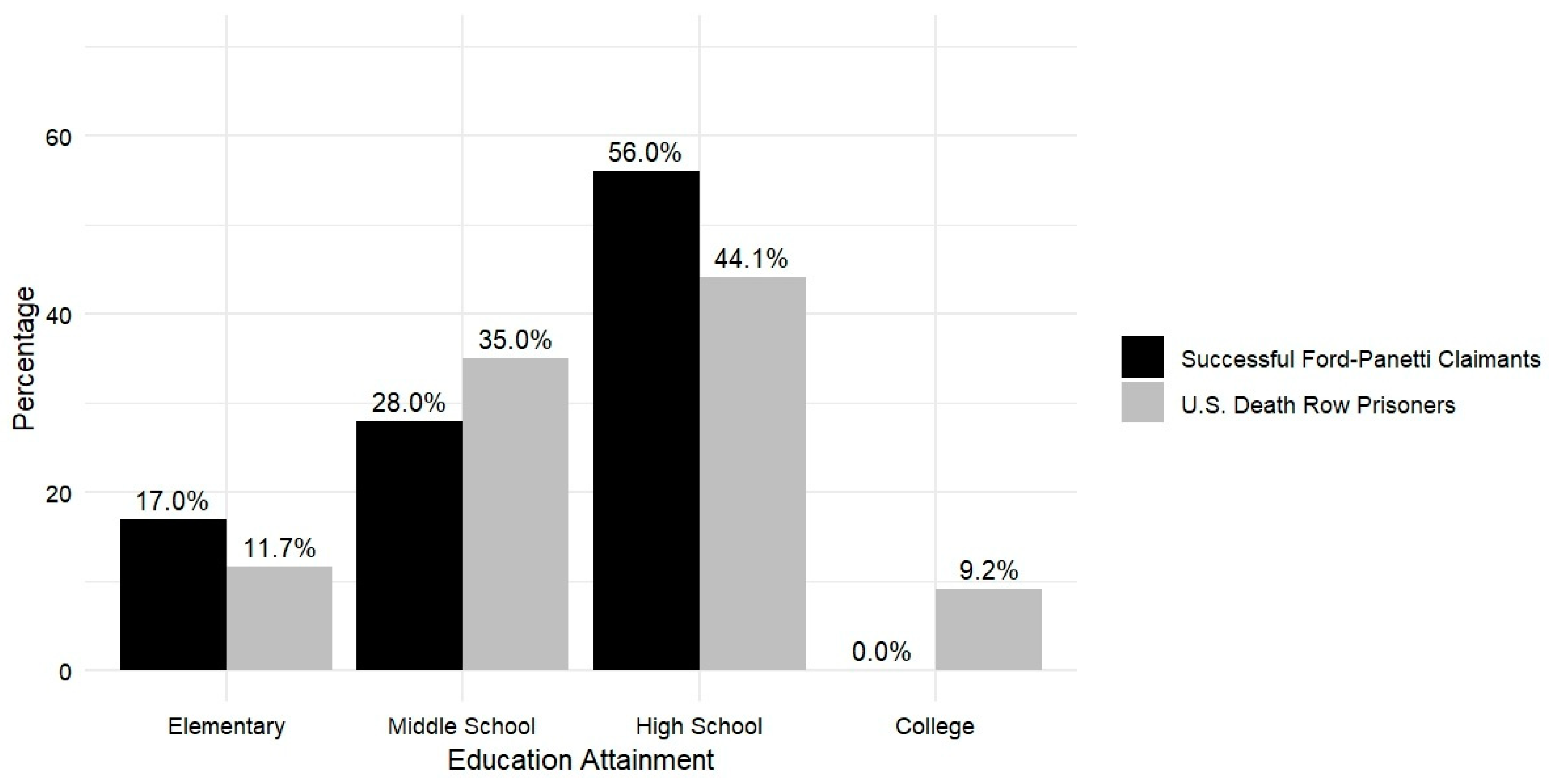

3.2.4. Education

3.2.5. Employment

3.2.6. Prior Criminal Record

3.3. Victim Demographics and Claimant-Victim Relationship

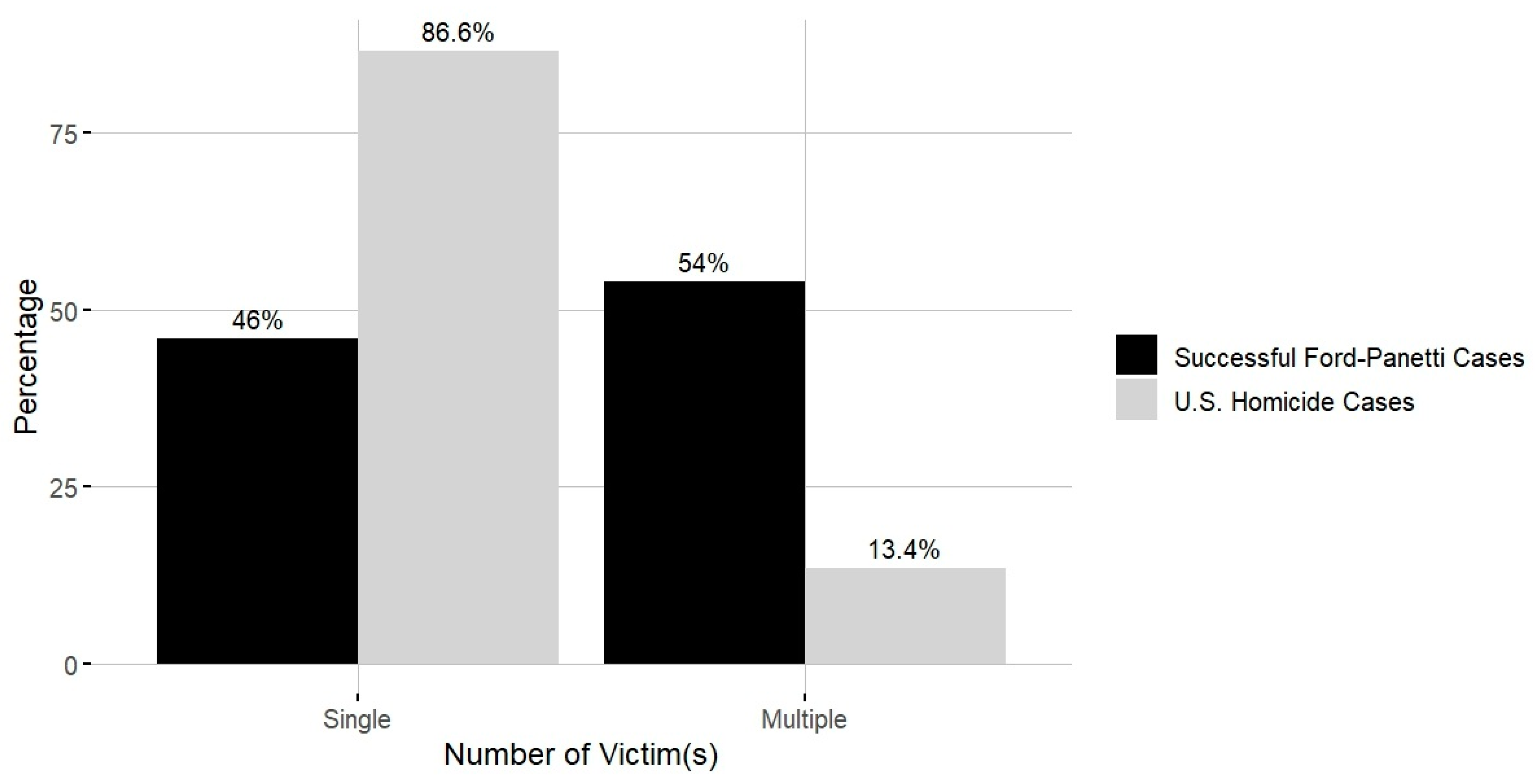

3.3.1. Number of Victims

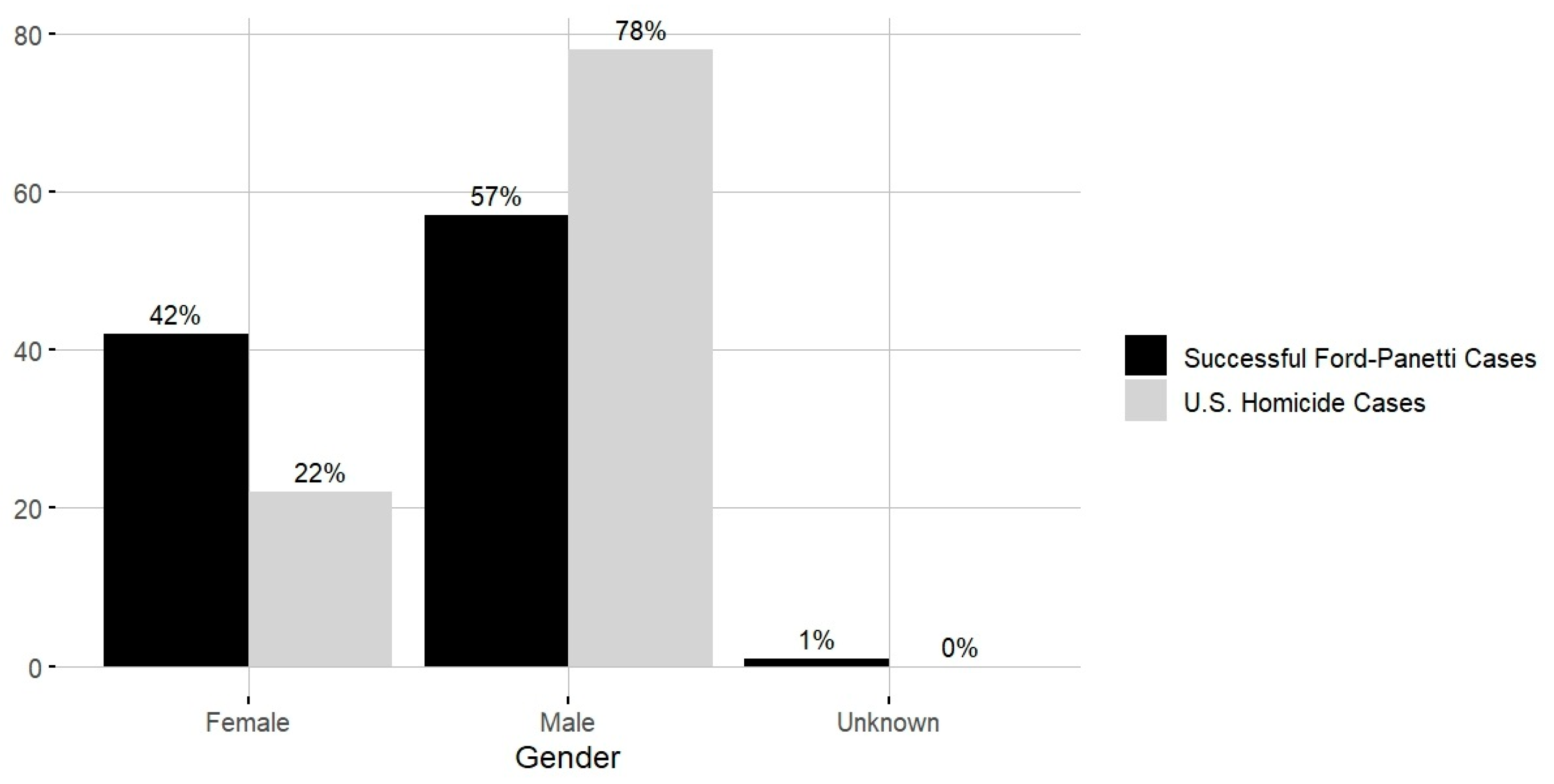

3.3.2. Victim Gender

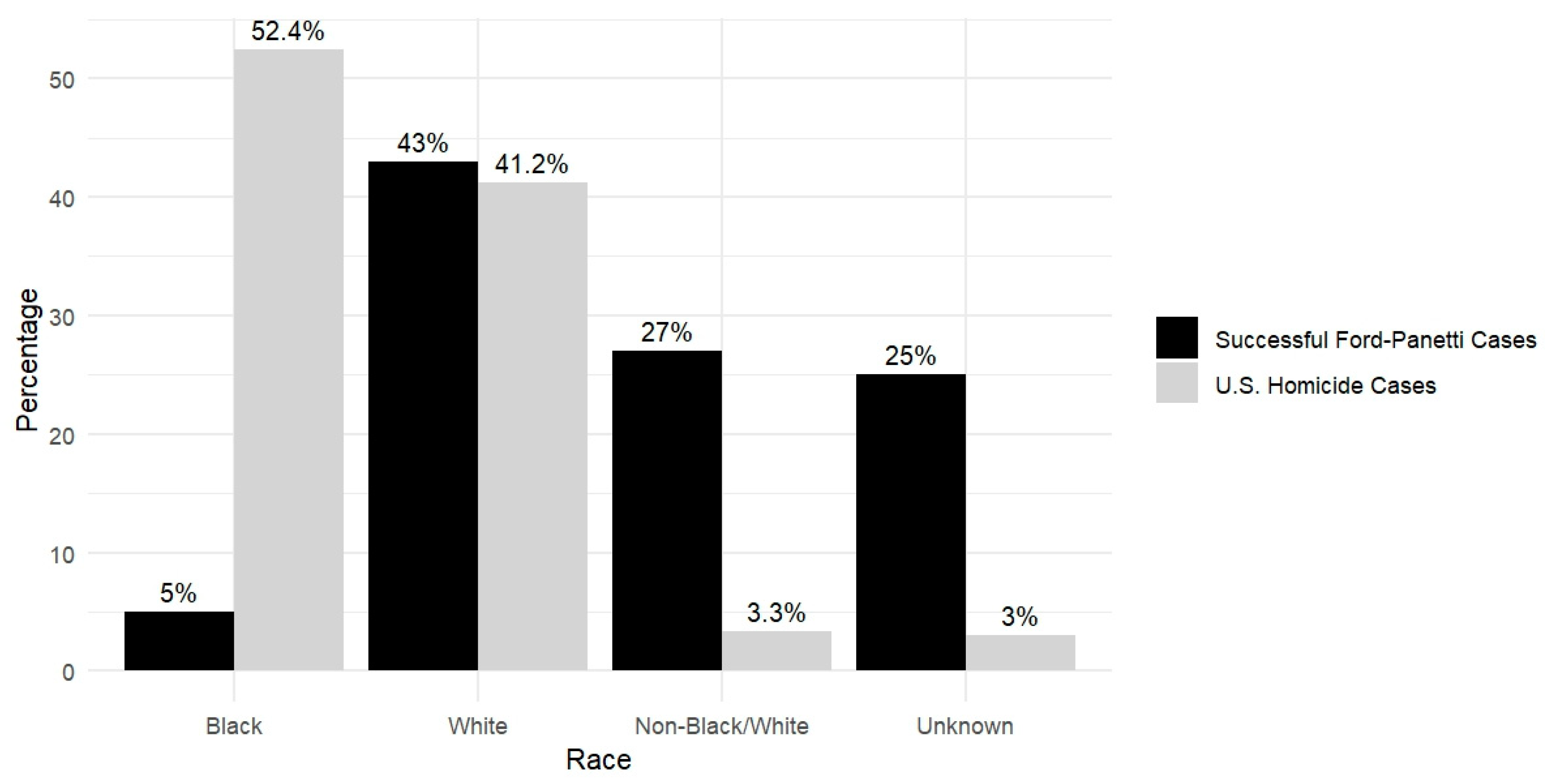

3.3.3. Victim Race

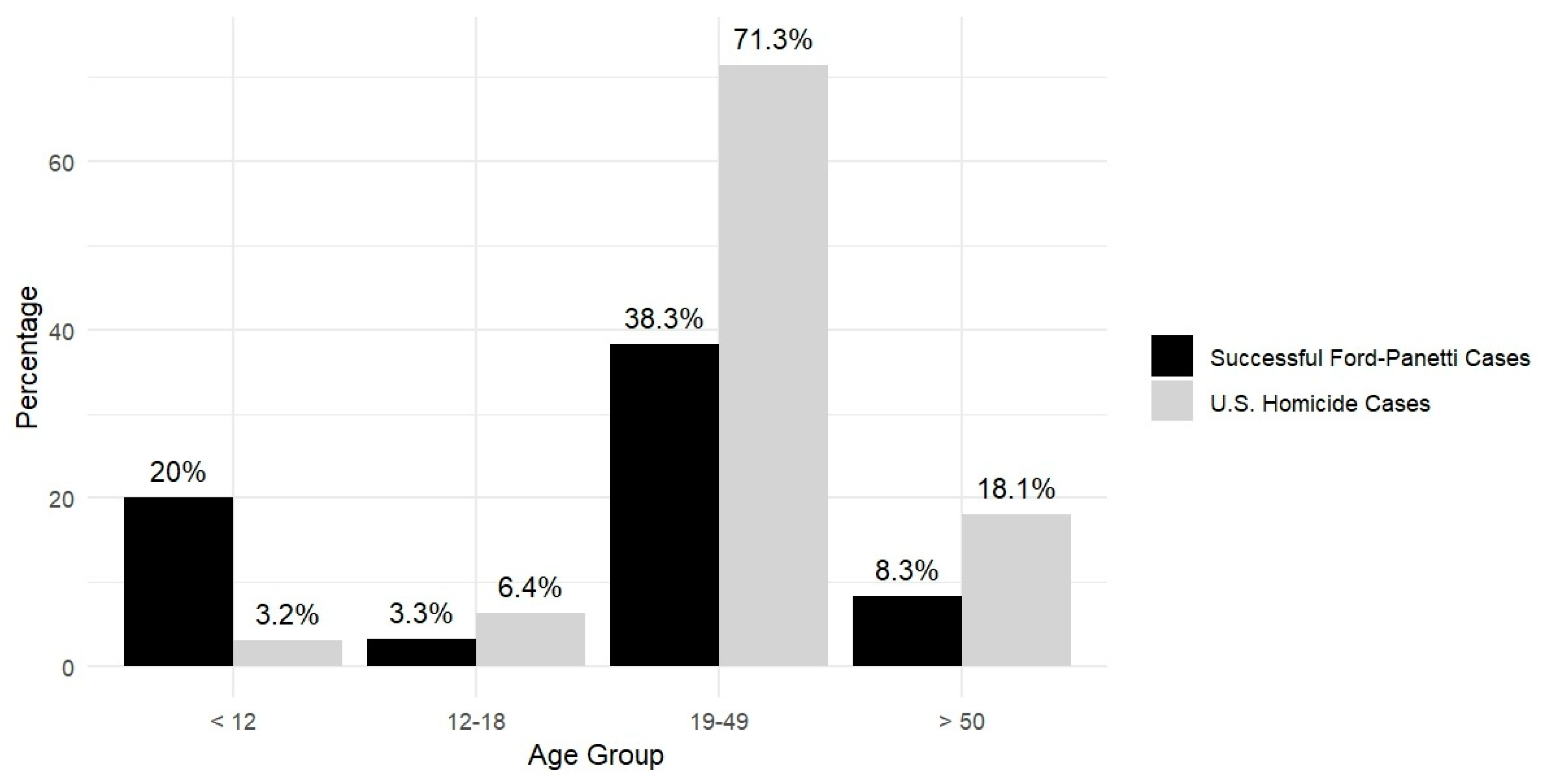

3.3.4. Victim Age

3.3.5. Claimant-Victim Relationship

3.4. Claimant Mental Illness

3.4.1. Serious Mental Illness

3.4.2. Intellectual Disability

3.4.3. Onset of Mental Illness

3.4.4. Treatment

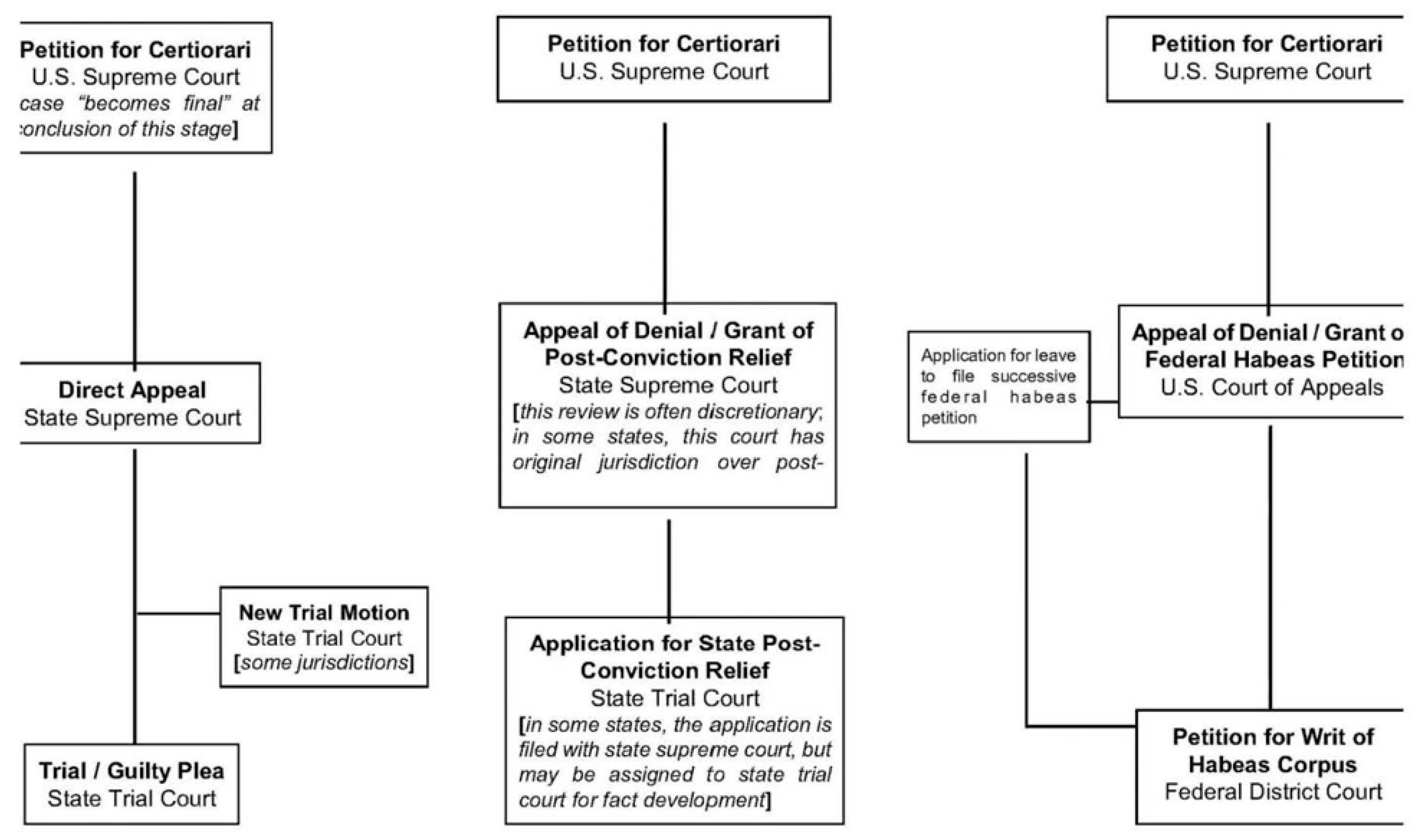

3.5. Litigation and Legal Activities

3.5.1. Mental Health Evidence Presentation Histories

3.5.2. Malingering

3.5.3. Competence Litation Histories

3.5.4. CFE Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Case Background

4.2. The First “Who” Question: Profiles of Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants

4.3. The Second “Who” Question: Profiles of the Victim and Claimant-Victim Relationship

4.4. The First “What” Question: Claimant Mental Illness

4.5. The Second “What” Question: Litigation and Legal Activities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Asadi, A. M.; Klein, B.; Meyer, D. Multiple comorbidities of 21 psychological disorders and relationships with psychosocial variables: A study of the online assessment and diagnostic system within a web-based population. Journal of medical Internet research 2015, 17(3), e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. What is intellectual disability? March 2024. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/intellectual-disability/what-is-intellectual-disability.

- American Psychiatric Association. What is schizophrenia? March 2024. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/schizophrenia/what-is-schizophrenia#section_1.

- American Psychiatric Association. What is a substance use disorder? April 2024. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/addiction-substance-use-disorders/what-is-a-substance-use-disorder.

- American Psychiatric Association. What is mental illness? November 2002. Available online: https://ychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness.

- American Psychiatric Association. What are personality disorders? November 2024. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/personality-disorders/what-are-personality-disorders.

- 7.Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 2002.

- Bedaso, A.; Ayalew, M.; Mekonnen, N.; Duko, B. Global estimates of the prevalence of depression among prisoners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression Research and Treatment 2020, 2020(1), 3695209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9.Blume, J. H. Johnson, J.H.S., Ed.; Nine steps of direct and collateral review in the U.S. In Blume. In LAW 4051 Death Penalty in America; Cornell Law School., 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, J. H.; Johnson; Lynn, Sheri; Ensler, K. E. Killing the oblivious: An empirical study of competency to be executed litigation. UMKC Law Review 2014, 82(2), 335–358. [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, S. L.; Zapf, P. A.; Boccaccini, M. T. The last competency: An examination of legal, ethical, and professional ambiguities regarding evaluations of competence for execution. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 2001, 1(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2006. Available online: https://biblioteca.cejamericas.org/bitstream/handle/2015/2829/Mental_Health_Problems_Prison_Jail_Inmates.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Female murder victims and victim-offender relationship, 2021. United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/female-murder-victims-and-victim-offender-relationship-2021.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Capital punishment, 2021–statistical tables. United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/cp21st.pdf.

- Ceci, S. J.; Scullin, M.; Kanaya, T. The difficulty of basing death penalty eligibility on IQ cutoff scores for mental retardation. Ethics & Behavior 2003, 13(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosed developmental disabilities in children aged 3–17 years: United States;Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db473.pdf.

- Dawson, P. A.; Putnal, J. D. Ford v. Wainwright: Eighth Amendment prohibits execution of the insane. Mercer Law Review 1986, 38, 949–968. [Google Scholar]

- Death Penalty Information Center. New resource: Bureau of Justice Statistics Reports 2021 showed 21st consecutive year of death row population decline. 2023. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/new-resource-bureau-of-justice-statistics-reports-2021-showed-21st-consecutive-year-of-death-row-population-decline.

- 19.Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402, 1960.

- Fazel, S.; Yoon, I. A.; Hayes, A. J. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction 2017, 112(10), 1725–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States annual reports: Expanded homicide tables. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2024. Available online: https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#.

- Wainwright, Ford v. 1986, 477 U.S. 399.

- French, L. A. Early trauma, substance abuse and crime: A clinical look at violence and the death sentence. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 1994, 10(2), 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgenti, A. A. The intersection of victim race and gender: The “Black Male Victim Effect” and the death penalty. Race and Justice 2015, 5(4), 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, L.; Kois, L. E.; Chen, C.; López-Aybar, L.; McCullough, B.; McLaughlin, K. J. Reliability of the term “serious mental illness”: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services 2022, 73(11), 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K.; Tamony, A. Death row phenomenon, death row syndrome and their affect on capital cases in the US. Internet Journal of Criminology 1 2010, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin, D. S.; O’Brien, C. P.; Auriacombe, M.; Borges, G.; Bucholz, K.; Budney, A.; Compton, W. M.; Crowley, T.; Ling, W.; Petry, N. M.; Schuckit, M.; Grant, B. F. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry 2013, 170(8), 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrington, V. Assessing the prevalence of intellectual disability among young male prisoners. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2009, 53(5), 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J. E.; Williams, M. R.; Demuth, S. White female victims and death penalty disparity research. Justice Quarterly 2004, 21(4), 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hritz, A. C.; Johnson, S. L.; Blume, J. H. Death by expert: Cognitive bias in the diagnosis of mild intellectual disability. Law & Psychology Review 2019, 44, 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger, M. F.; Lane, M. C.; Loranger, A. W.; Kessler, R. C. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry 2007, 62(6), 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. W. A time-sensitive analysis of the work-crime relationship for young men. Social Science Research 84 2019, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison v. Alabama, 586 U.S. ___, 2019.

- McCutcheon, R. A.; Marques, T. R.; Howes, O. D. Schizophrenia—an overview. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77(2), 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittenberg, W.; Patton, C.; Canyock, E. M.; Condit, D. C. Base rates of malingering and symptom exeggeration. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 2002, 24(8), 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. L., III. Ford v. Wainwright: A Coda in the executioner’s song. Iowa Law Review 1986, 72, 1461–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Murrie, D. C.; Gowensmith, W. N.; Kois, L. E.; Packer, I. K. Evaluations of competence to stand trial are evolving amid a national “competency crisis”. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 2023, 41(5), 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Death row U.S.A. 2022. Available online: https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/DRUSAWinter2022.pdf.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Mental illness. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. September 2024. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Personality disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. n.d. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/personality-disorders.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. n.d. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia.

- 42.Panetti, v. Quarterman, 551 U.S. 930, 2007.

- Perlin, M. L.; Harmon, T. R. “Insanity is smashing up against my soul”: The Fifth Circuit and competency to be executed cases after Panetti v. Quarterman. University of Louisville Law Review 2021, 60, 557–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlin, M. L.; Harmon, T. R.; Geiger, M. “The timeless explosion of fantasy’s dream”: How state courts have ignored the Supreme Court’s decision in Panetti v. Quarterman. American Journal of Law & Medicine 2023, 49(2-3), 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlin, M. L.; Harmon, T. R.; Kubiniec, H. ’The world of illusion is at my door’: Why Panetti v. Quarterman is a legal mirage. New York Law School Legal Studies Research Paper 2022, 4172316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirelli, G.; Gottdiener, W. H.; Zapf, P. A. A meta-analytic review of competency to stand trial research. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 2011, 17(1), 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, S. J. Prevalence of mental illnesses in US state prisons: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services 2014, 65(7), 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radelet, M. L. Racial characteristics and the imposition of the death penalty. American Sociological Review 1981, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radelet, M. L.; Miller, K. S. The aftermath of Ford v. Wainwright. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 1992, 10(3), 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, M.; Way, B.; Steinbacher, M.; Sawyer, D.; Smith, H. Personality disorders in prison: Aren’t they all antisocial? Psychiatric Quarterly 2002, 73, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, C. E.; Hritz, A. C.; Hans, V. P.; Eisenberg, T.; Wells, M. T.; Blume, J. H.; Johnson, S. L. Victim gender and the death penalty. UMKC Law Review 2014, 82, 429–464. [Google Scholar]

- Simeone, J. C.; Ward, A. J.; Rotella, P.; Collins, J.; Windisch, R. An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990─ 2013: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobogin, C. Mental illness and the death penalty. Mental & Physical Disability Law Reporter 2000, 24, 667–682. [Google Scholar]

- Somers, J. M.; Goldner, E. M.; Waraich, P.; Hsu, L. Prevalence studies of substance-related disorders: A systematic review of the literature. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2004, 49(6), 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanziani, M.; Cox, J.; Bownes, E.; Carden, K. D.; DeMatteo, D. S. Marking the progress of a “maturing” society: Madison v. Alabama and competency for execution evaluations. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 2020, 26(2), 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, H. J.; Osher, F. C.; Robbins, P. C.; Case, B.; Samuels, S. Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatric Services 2009, 60(6), 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, J. T.; Kramer, J. H.; Zajac, G. The race of defendants and victims in Pennsylvania death penalty decisions: 2000–2010. Justice Quarterly 2020, 37(5), 955–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. R.; Demuth, S.; Holcomb, J. E. Understanding the influence of victim gender in death penalty cases: The importance of victim race, sex-related victimization, and jury decision making. Criminology 2007, 45(4), 865–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | n |

|---|---|

| Death-Sentenced Cases * | 5724 |

| Executions ** | 1280 |

| Ford Claims | 141 |

| Ford Claims on the Merits | 92 |

| Unsuccessful Ford Claims | 120 |

| Unsuccessful Ford Claims on the Merits | 71 |

| Unsuccessful Ford Claims on the Procedural Grounds | 49 |

| Successful Ford Claims | 21 |

| Year | n |

|---|---|

| 1974-1980 | 5 |

| 1981-1990 | 15 |

| 1991-2000 | 6 |

| 2001-2010 | 2 |

| 2011-2024 | 0 |

| State |

n |

State | n | State | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 0 | Kentucky | 0 | Oregon* | 0 |

| Arizona | 1 | Louisiana | 2 | Oklahoma | 3 |

| Arkansas | 2 | Mississippi | 1 | Pennsylvania* | 2 |

| California* | 1 | Missouri | 1 | South Carolina | 2 |

| Florida | 0 | Montana | 0 | South Dakota | 0 |

| Georgia | 0 | Nebraska | 0 | Tennessee* | 0 |

| Idaho | 2 | Nevada | 0 | Texas | 9 |

| Indiana | 0 | North Carolina | 1 | Utah | 0 |

| Kansas | 0 | Ohio* | 1 | Wyoming | 0 |

| State | Successful Ford-Panetti Casesn | Prisoners on Death Row n |

Ratio of Successful Ford-Panetti Cases to Death Row Inmates % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 1 | 114 | 0.9% |

| Arkansas | 2 | 28 | 7.1% |

| California | 1 | 665 | 0.2% |

| Idaho | 2 | 8 | 25.0% |

| Louisiana | 2 | 63 | 3.2% |

| Mississippi | 1 | 36 | 2.8% |

| Missouri | 1 | 18 | 5.6% |

| North Carolina | 1 | 140 | 0.7% |

| Ohio | 1 | 129 | 0.8% |

| Oklahoma | 3 | 40 | 7.5% |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 123 | 1.6% |

| South Carolina | 2 | 36 | 5.6% |

| Texas | 9 | 192 | 4.7% |

| State | Successful Ford-Panetti Cases n |

Executions n |

Ratio of Successful Ford-Panetti Cases to Executions % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 1 | 40 | 2.5% |

| Arkansas | 2 | 31 | 6.5% |

| California | 1 | 13 | 7.7% |

| Idaho | 2 | 3 | 66.7% |

| Louisiana | 2 | 28 | 7.1% |

| Mississippi | 1 | 23 | 4.3% |

| Missouri | 1 | 99 | 1.0% |

| North Carolina | 1 | 43 | 2.3% |

| Ohio | 1 | 56 | 1.8% |

| Oklahoma | 3 | 124 | 2.4% |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 3 | 66.7% |

| South Carolina | 2 | 43 | 4.7% |

| Texas | 9 | 587 | 1.5% |

| Case No. | Schizophrenia | Substance Use Disorder | Personality Disorder | Other SMIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | - | + | + |

| 2 | + | + | - | + |

| 3 | + | + | - | + |

| 4 | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | + | - | + | + |

| 6 | + | - | - | + |

| 7 | + | + | + | - |

| 8 | + | - | + | + |

| 9 | + | - | + | + |

| 10 | + | - | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | - | + |

| 12 | + | - | + | + |

| 13 | + | + | - | + |

| 14 | + | - | + | + |

| 15 | + | + | - | + |

| 16 | + | - | - | + |

| 17 | + | - | + | - |

| 18 | - | + | - | + |

| 19 | + | - | - | + |

| 20 | + | - | - | + |

| 21 | + | - | - | - |

| 22 | + | - | + | - |

| Phase | Mental Health Evidence n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Missing Data | |

| Trial | 17 (61%) | 7 (25%) | 4 (14%) |

| Post-Conviction Relief (PCR) | 18 (64%) | 1 (4%) | 9 (32%) |

| Habeas Corpus | 26 (93%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) |

| Case No. | Mental Health Professionals | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrists n |

Psychologists n; Details |

Others n; Details |

|

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

5 2 6 > 1 1 2 - 1 1 1 1 1 1 - > 1 > 1 1 - 1 3 - 1 1 1 1 - 1 - |

- 1 1; Unlicensed 1 1 1 - 1 - - - 2 1 - - > 1 - - 1 1 - - - 1; Forensic Psychologist 1; Clinical Psychologist 1; Psychologist (Ed.D.) 1 - 1 1 |

- - - - - - 1; State Hospital Personnel 1; Social Worker 1; Neurologist - - - - 2; General Practitioners - - 1; Counselor 1; Psychology Expert > 1; Mental Health Professional - 1; Neurologist - - - - - - - |

| Age | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Death Row Prisoners |

|---|---|---|

| 18-49 | 4% | 39.7% |

| 50-59 | 20% | 33.8% |

| 60 or older | 76% | 26.5% |

| Race | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Death Row Prisoners |

|---|---|---|

| White | 35.7% | 42.3% |

| Black | 42.9% | 41.0% |

| Latinx | 7.1% | 13.8% |

| Native American | 3.6% | 1.0% |

| Asian | 0% | 1.9% |

| Other or unknown | 10.7% | 0.0% |

| Education Attainment | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Death Row Prisoners |

|---|---|---|

| Elementary school | 17.0% | 11.7% |

| Middle School | 28.0% | 35.0% |

| High School | 56.0% | 44.1% |

| College | 0.0% | 9.2% |

| Number of Victim(s) | Successful Ford-Panetti Cases | U.S. Homicide Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Single victim | 46% | 86.6% |

| Multiple victims | 54% | 13.4% |

| Gender | Successful Ford-Panetti Cases | U.S. Homicide Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 42% | 22% |

| Male | 57% | 78% |

| Unknown | 1% | 0% |

| Race | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Homicide Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 5% | 52.4% |

| White | 43% | 41.2% |

| Non-Black/White | 27% | 3.3% |

| Unknown | 25% | 3.1% |

| Age Group (in Years) | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Homicide Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Under 12 | 20% | 3.2% |

| 12-18 | 3.3% | 6.4% |

| 19-49 | 38.3% | 71.3 |

| 50 and older | 8.3% | 18.1 |

| Unknown | 30% | 1.1 |

| Race | Successful Ford-Panetti Cases | U.S. Homicide Cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offender | Victim | |||

| Intraracial | Black | Black | 0% | 89% |

| White | White | 18% | 79% | |

| Transracial | Black | White | 36% | 17% |

| White | Black | 5% | 8% | |

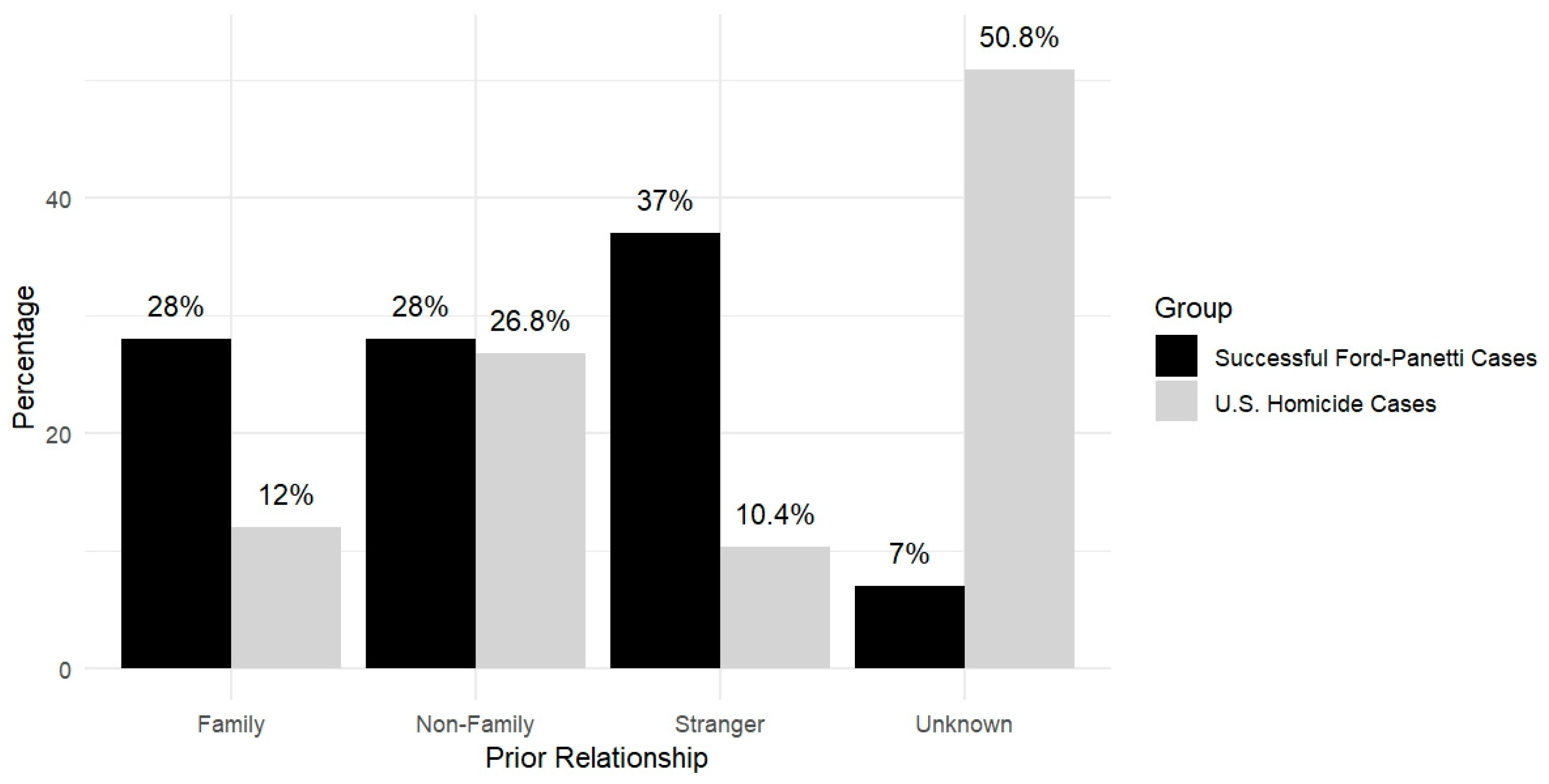

| Prior Relationship | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Homicide Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Stranger | ||

| Family Member | 28% | 12.0% |

| Non-Family Member | 28% | 26.8% |

| Stranger | 37% | 10.4% |

| Unknown | 7% | 50.8% |

| Successful Ford-Panetti Cases | U.S. Homicide Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victim Gender | ||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Non-Stranger | ||||

| Family Member | 28% | 24% | 50% | 16% |

| Non-Family Member | 40% | 18% | 26% | 40% |

| Stranger | 28% | 44% | 12% | 21% |

| Unknown | 4% | 0% | 20% | 33% |

| Serious Mental Illness | Successful Ford-Panetti Claimants | U.S. Incarcerated Population | U.S. General Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | 86% | 2-6.5% | 0.33-0.48% |

| Personality Disorders | 39% | 21% | 9.1% |

| Intellectual Disability | 21% | 10% | 1.65% |

| Substance Use Disorders | 29% | 30% | 6.6-13.2% |

| Depressive Disorders | 29% | 36.9% | 8.3% |

| Overall SMI | 100% | 10-16.7% | 6% |

| 1 | As mentioned in the Supreme Court cases section, Scott Panetti was once again found incompetent for execution in September 2024, after our analysis had concluded (at the stopping point). If Panetti is included, this would add one additional case to the year 2024. However, in total, only 28 cases are included in the analysis |

| 2 | While operational definitions of SMI vary (Gonzales et al., 2022), they are broadly understood as a “mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment that substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities” (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2024). |

| 3 | The neurocognitive disorders encompass cases historically referred to as mild organic brain disorder, organic brain dysfunction, organic brain damage, organic brain syndrome, or brain injury, reflecting changes in diagnostic terminology over time. |

| 4 |

We also examined whether the successful Ford-Panetti claimants filed for other competency challenges, such as competency to plead guilty and competency to waive counsel. Unfortunately, due to a substantial portion of missing data, we could not report meaningful results. However, the following findings emerged:

Competency to Plead Guilty

Among the successful Ford-Panetti claimants, 16 had missing data. Only one individual was ever deemed competent to plead guilty. Notably, in 14 cases, a competency evaluation to plead guilty was not conducted—either because it was not applicable to the case or due to unwillingness.

Competency to Waive Counsel

Of the successful Ford-Panetti claimants, 17 had missing data. Only three individuals were deemed competent to waive counsel, while one case involved a claimant being deemed incompetent to waive counsel on at least two occasions. Additionally, in a subset of seven cases, no competency evaluation to waive counsel was conducted, primarily due to unwillingness.

|

| 5 | Although it is valid to suggest that cases involving female victims are more likely to result in the death penalty (Holcomb et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2007; Royer et al., 2014), which could help explain the difference between the successful Ford-Panetti cases and the national pool of homicide data, it is also important to consider that these cases may present a distinct picture of gendered homicide. Factors such as the presence of sexual victimization, the method of killing, the relationship between the victim and the defendant, and whether the victim had family responsibilities (Royer et al., 2014) may differentiate these cases from other homicide cases, warranting further exploration. |

| 6 | Similar to the previous footnote, although it has long been found that victim race plays a role in the death penalty—particularly with a racial disparity in killings of whites versus blacks, where killings of whites are more likely to result in the death penalty (Radelet, 1981; Holcomb et al., 2004; Ulmer et al., 2020) and, conversely, the 'black male victim effect' (Girgenti, 2015) is associated with being deemed less cruel and less likely to result in the death penalty—our database shows that the number of white victims is similar across the successful Ford-Panetti cases and the national homicide pool. However, there may still be potential differences in the dynamics at play, suggesting that these killings could differ from the national pool of homicide cases. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).