Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods of Calculation

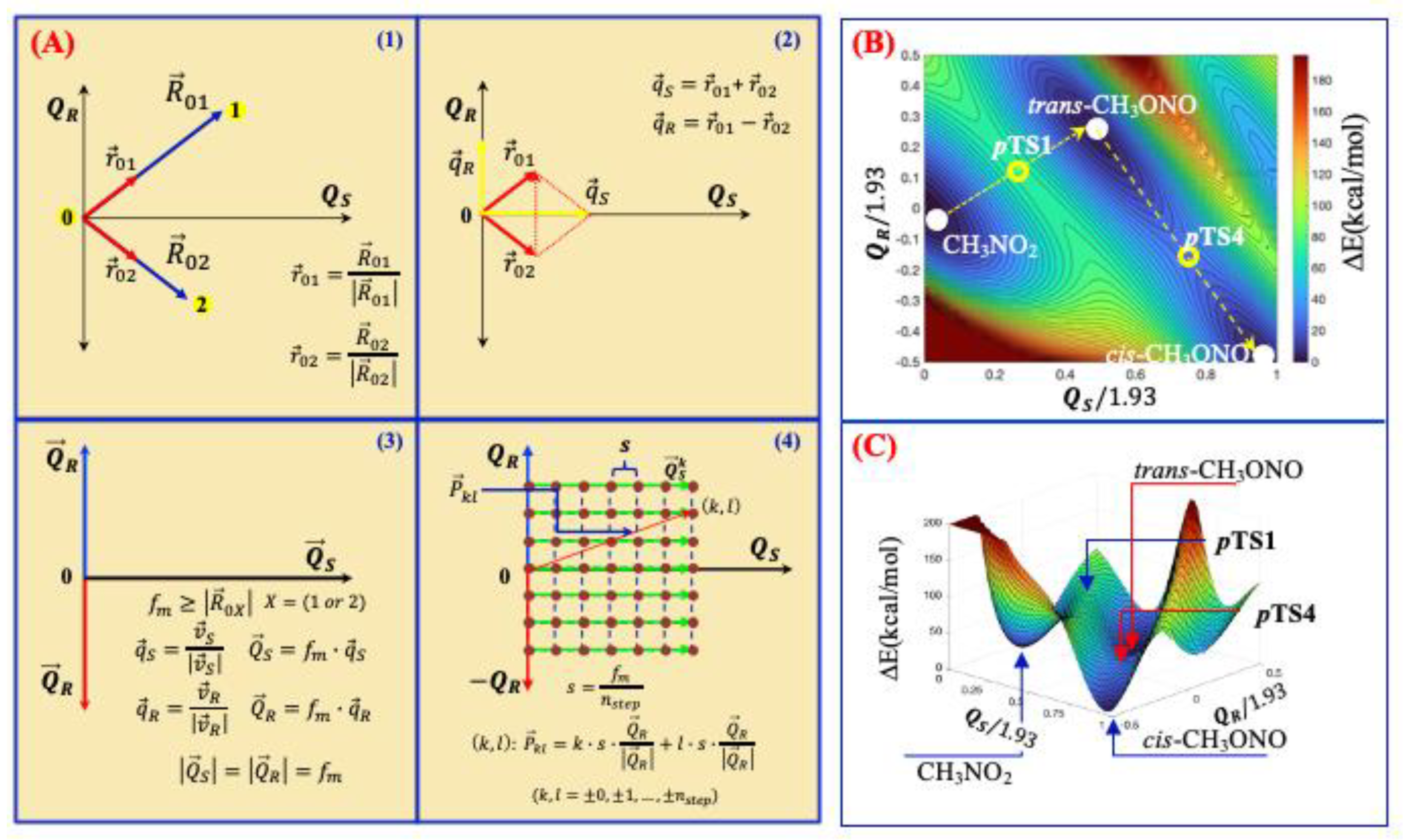

Mapping of 2D-Potential Energy Surfaces

3. Results and Discussion

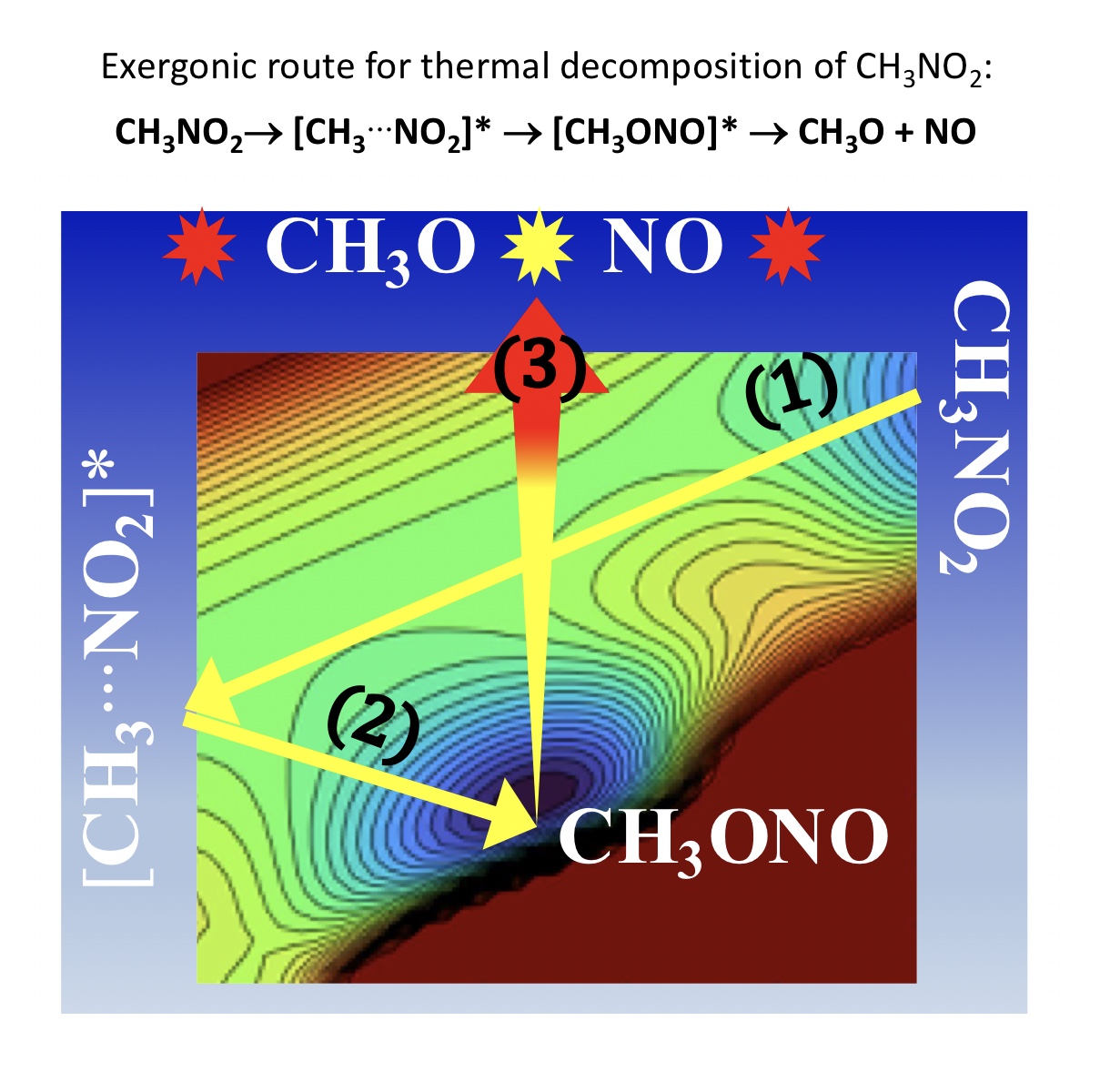

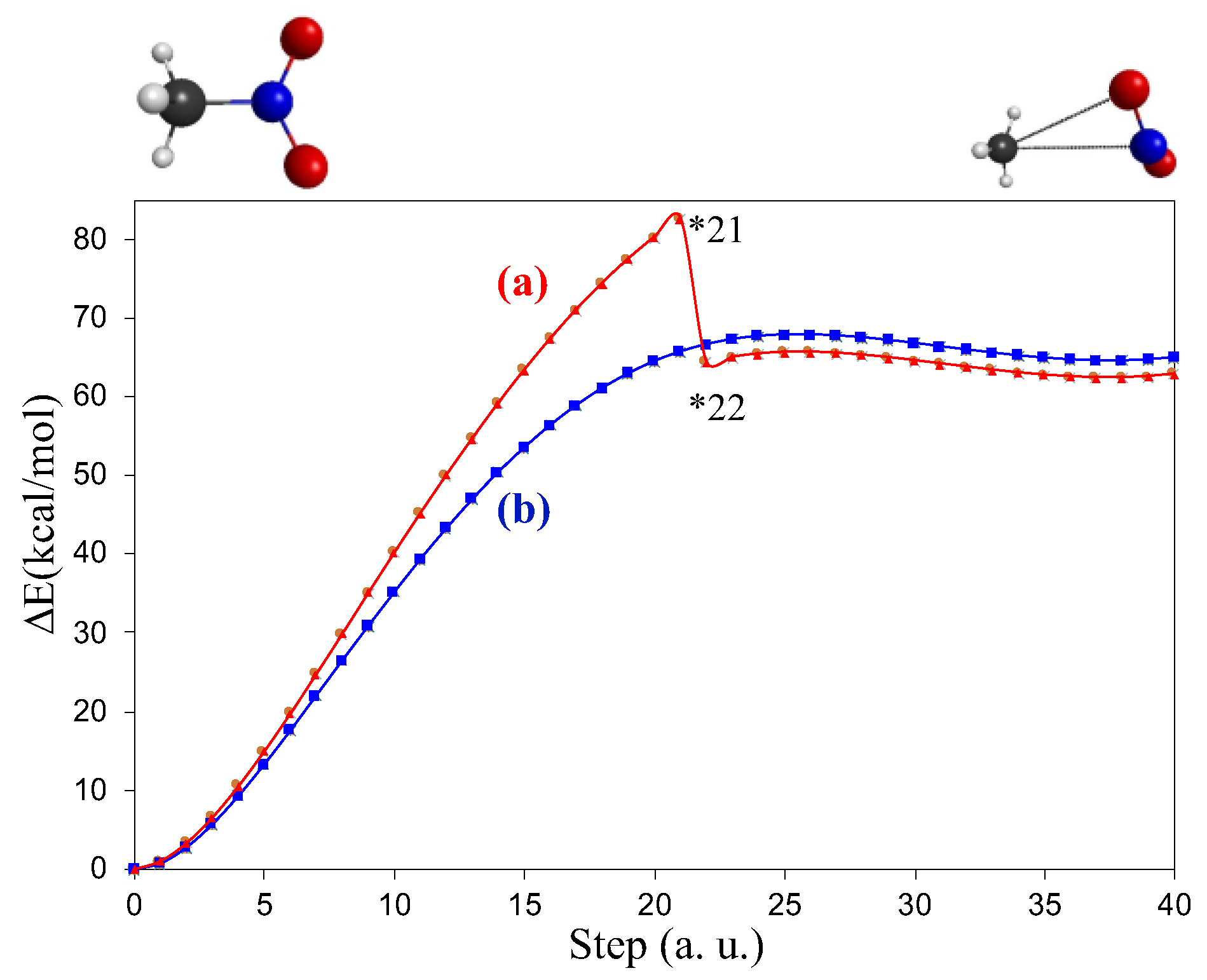

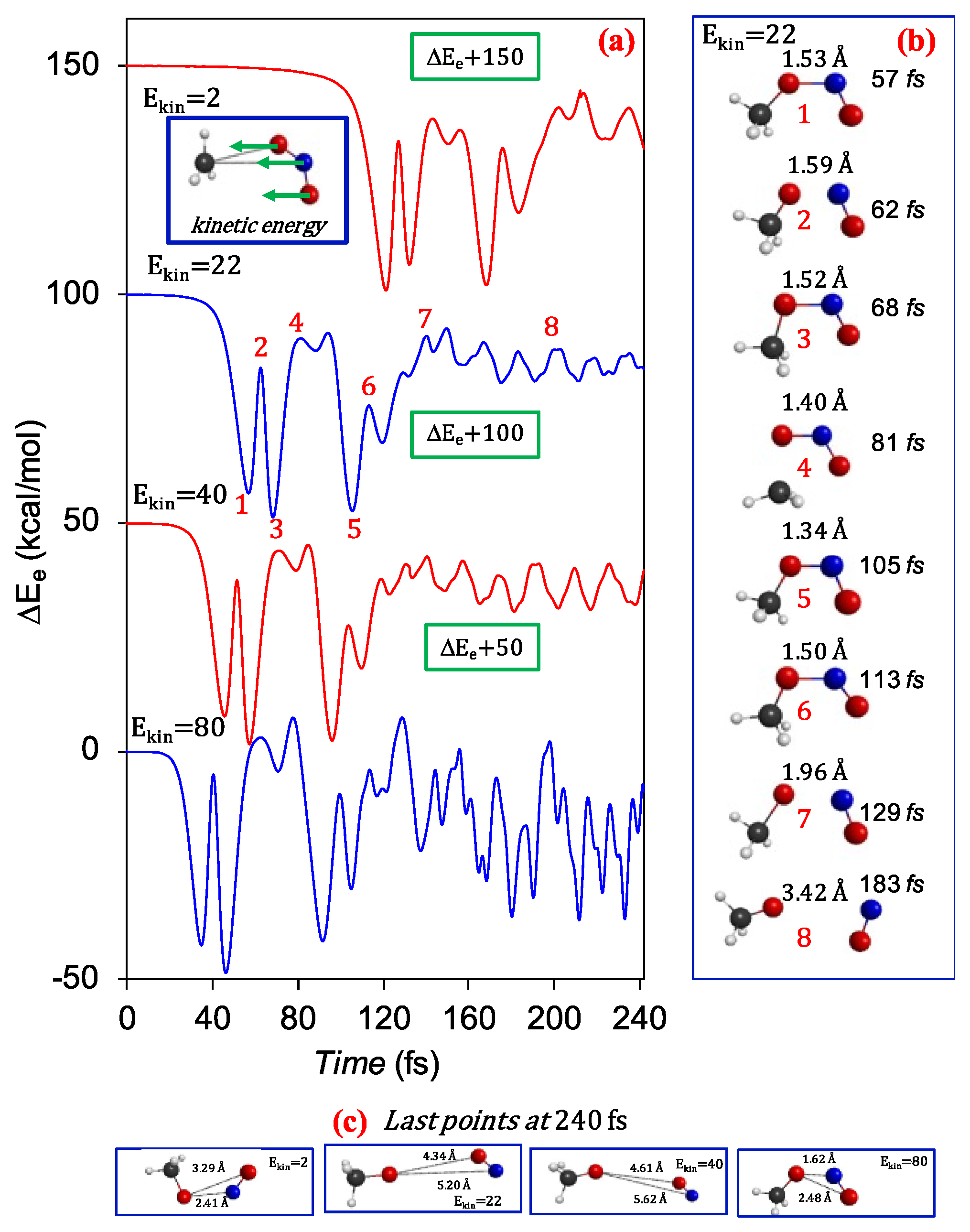

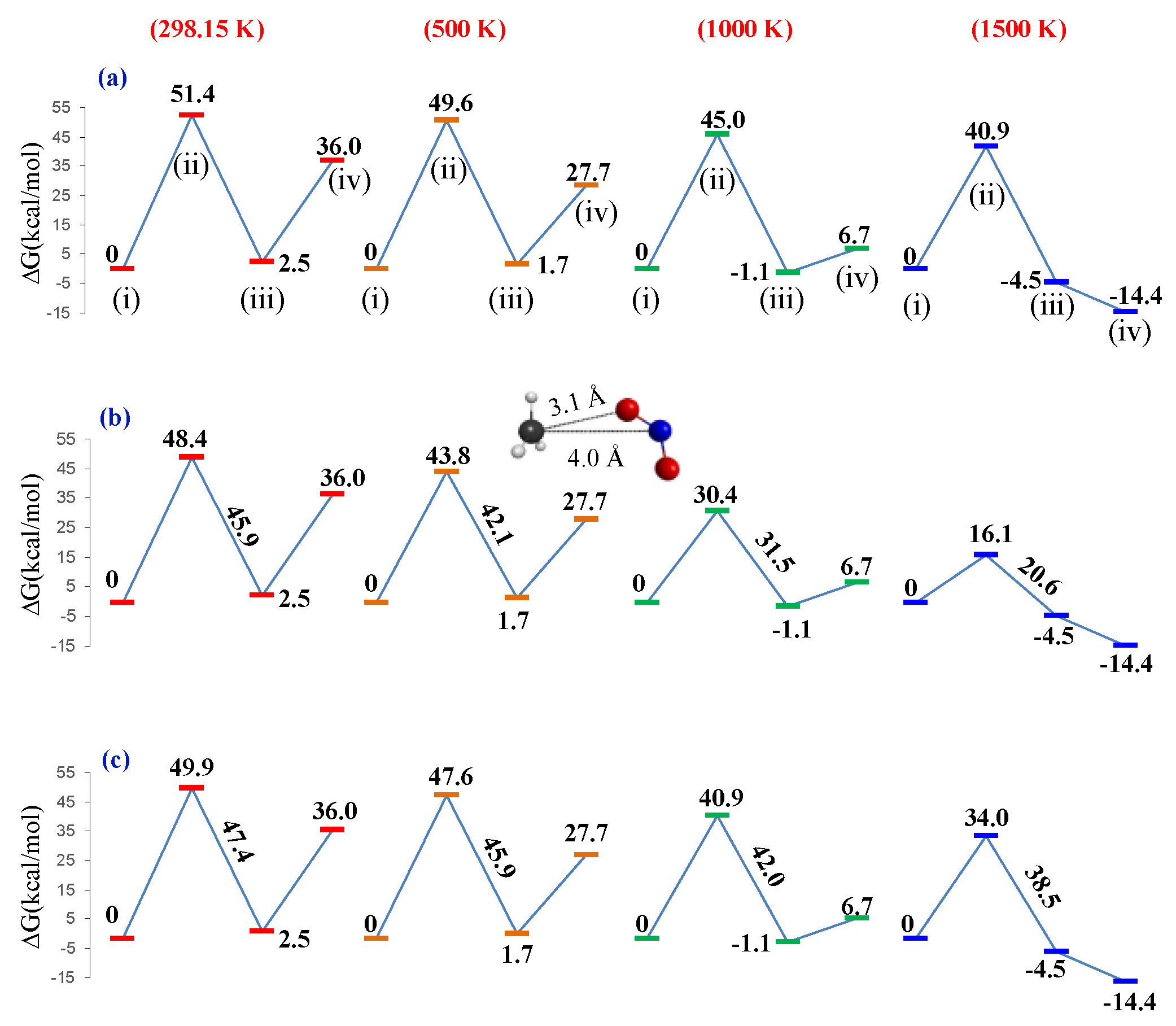

3.1. Unimolecular Reactions of Nitromethane and Methyl Nitrite

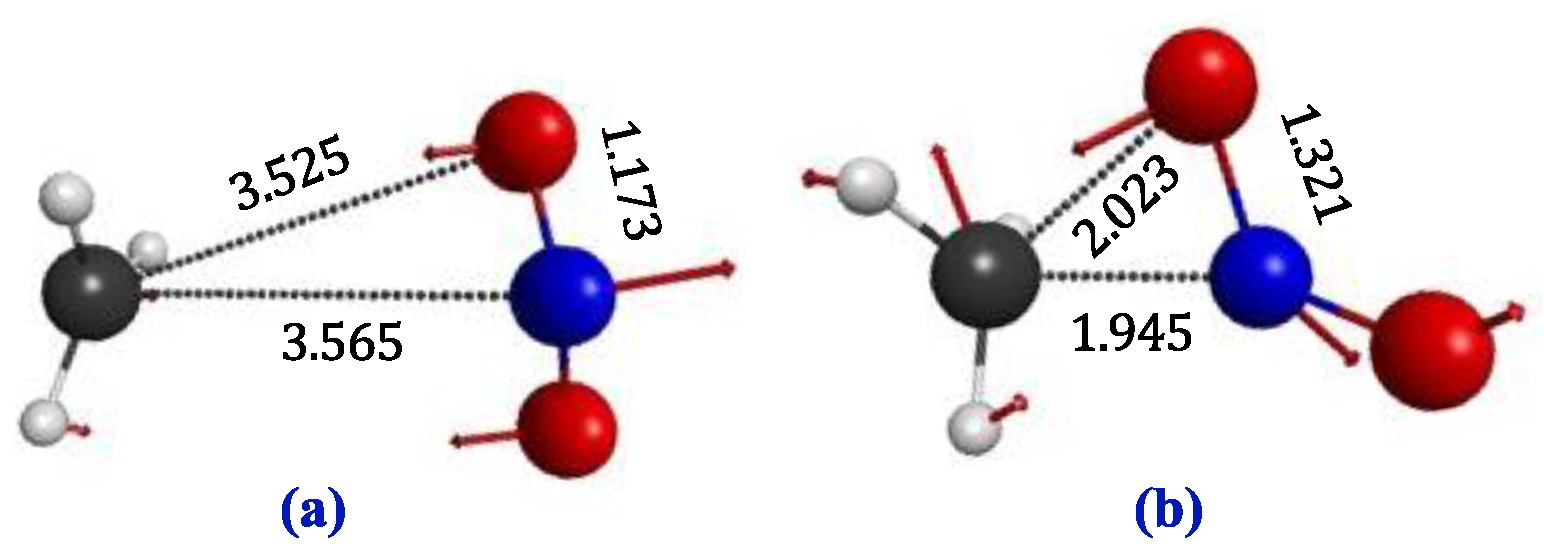

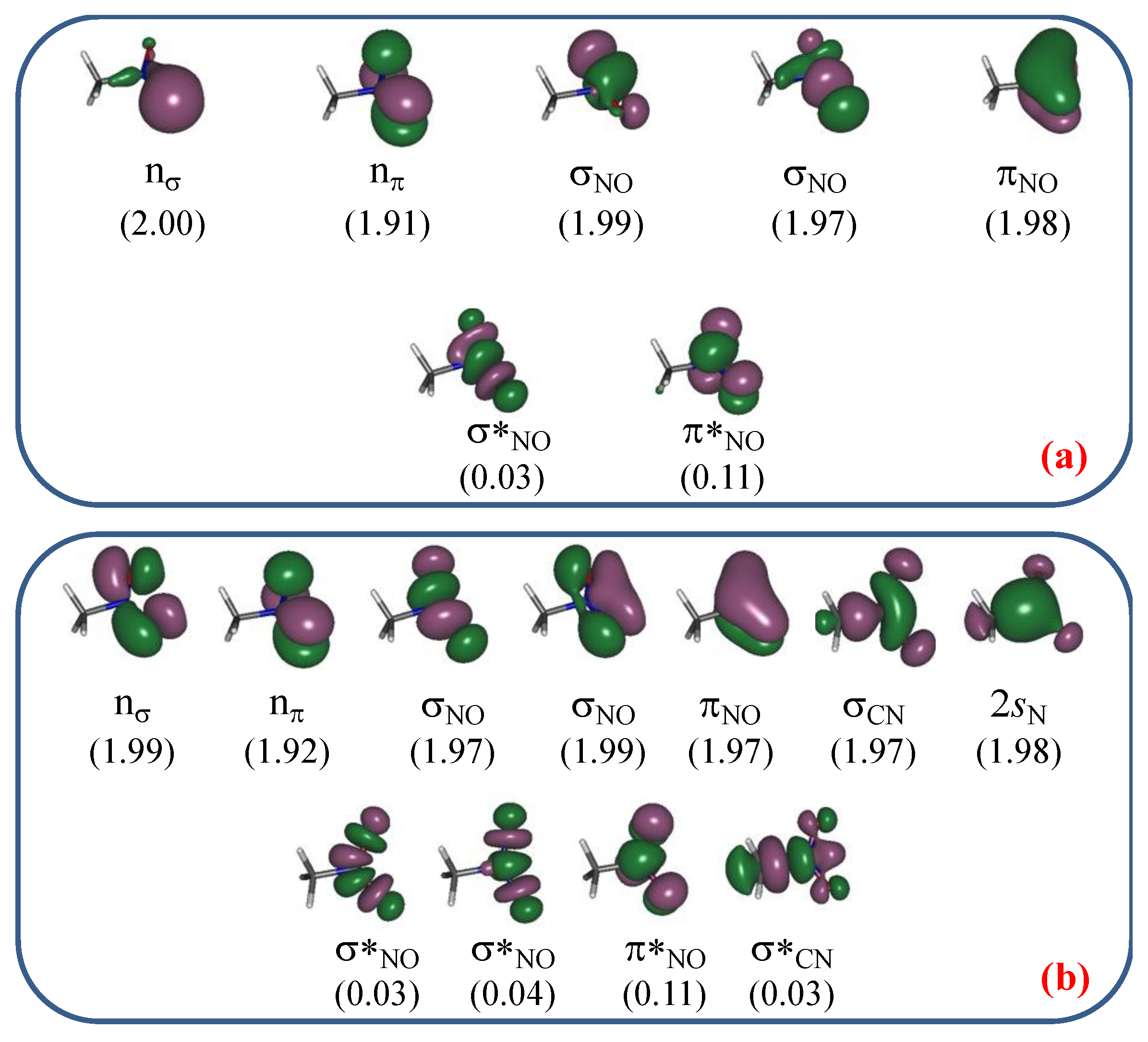

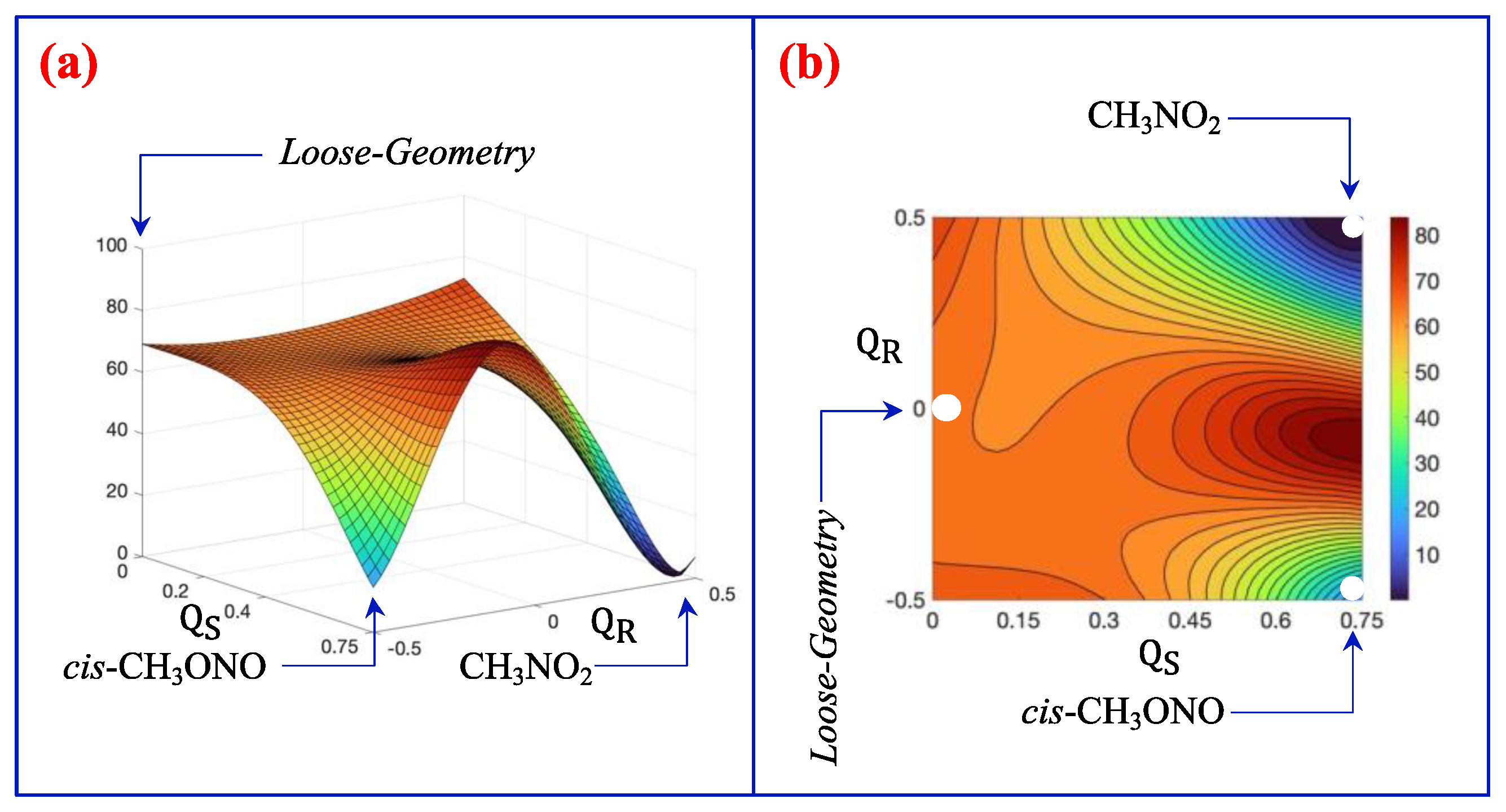

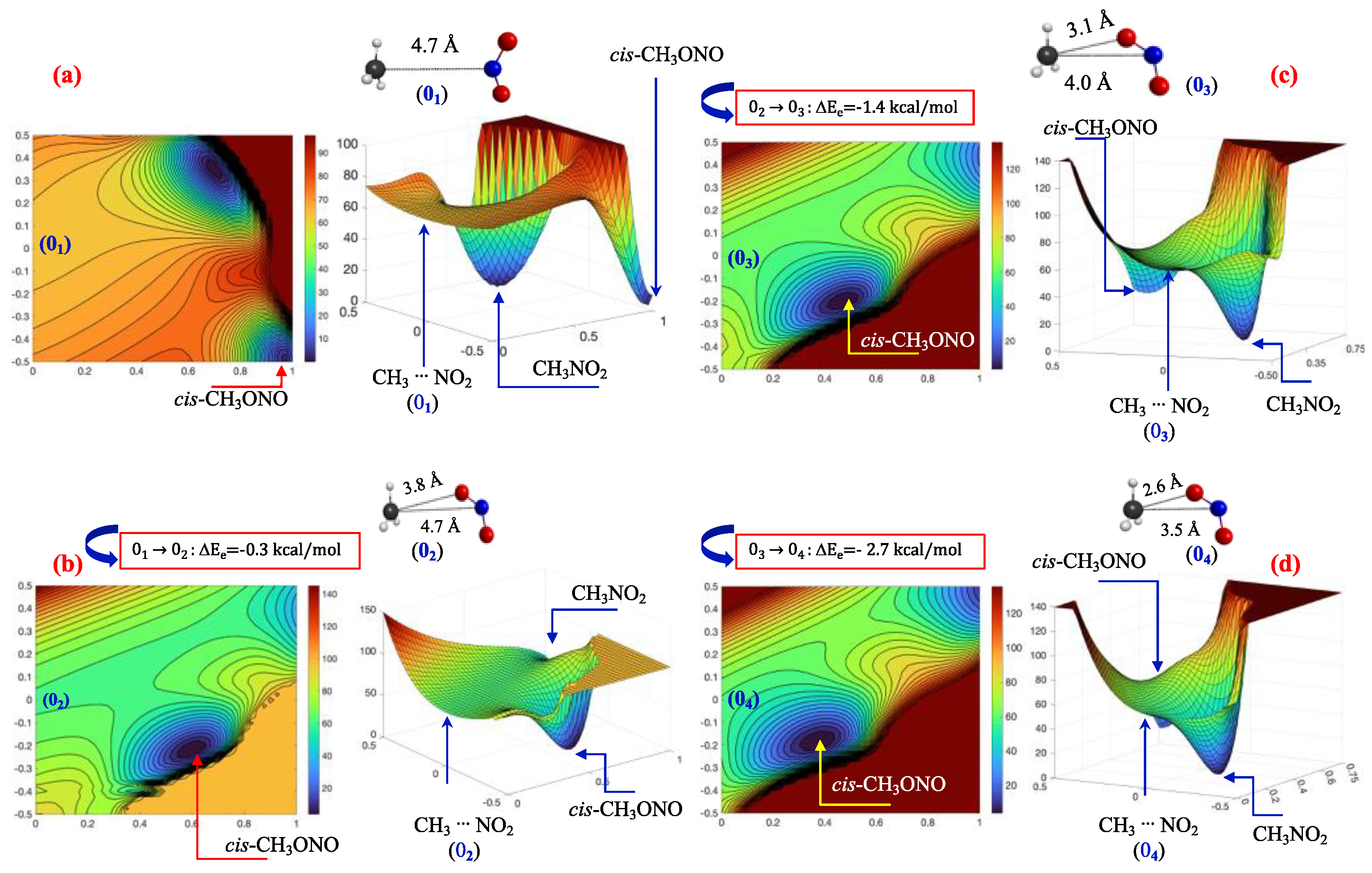

3.2. A Look at the so-Called Loose Transition State

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Word, M.D.; Lo, H.A.; Boateng, D.A.; McPherson, S.L.; Gutsev, G.L.; Gutsev, L.G.; Lao, K.U.; Tibbetts, K.M. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 879–888. [CrossRef]

- Leyva, E.; Loredo-Carrillo, S.E.; Aguilar, J. Reactions 2023, 4, 432–447. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, J.; Hu, D.; Lan, Z. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2021, 23, 25597–25611. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.L. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108, 5784–5792.; McKee, M.L.. J. Phys. Chem., 1989, 93, 7365–7369.

- Saxon, R.P.; Yuoshimi, M. Can. J. Chem., 1992, 70, 572–579. [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yin, S. Chem. Phys. Lett., 2022, 792, 139413. [CrossRef]

- Homayoon, Z.; Bowman, J.M. J. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2013, 117, 11665–11672. (b) Homayoon, Z.; Bowman, J.M.; Dey, A.; Abeysekera, C.; Fernando, R.; Suits, A.G. Z. Phys. Chem., 2013, 227, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.S.; Raghunath, P.; Lin, M.C. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2013, 117, 7308–7313. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.S.; Lin, M.C. Chem. Phys. Lett., 2009, 478, 11–16. [CrossRef]

- Isegawa, M.; Liu, F.; Maeda, S.; Morokuma, K. J. Chem. Phys., 2014, 140, 244310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Peláez, D.; Soto, J. J. Chem. Phys., 2005, 122, 084324. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Peláez, D.; Soto, J. J. Chem. Phys., 2003, 119, 7814–7823. [CrossRef]

- Sumida, M.; Kohge, Y.; Yamasaki, K.; Kohguchia, H. J. Chem. Phys., 2016, 144, 064304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.-G.; Liu, Q.-J.; Liu, F.-S.; Liu, Z.-T. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2023, 25, 5613–5618. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Liu, Q.-J.; Liu, F.-S.; Liu, Z.-T. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2023, 25, 5685–5693. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, B.M.; Sahu, S.; Owens, F.J. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem), 2002, 583, 69–72. [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Seritan, S.; Zhu, X.; Sakano, M.N.; Islam, M.M.; Strachan, A.; Martínez, T.J. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2021, 125, 1447–1460. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.; Bjorgaard, J.; Greenfield, M.; Bolme, C.; Brown, K.; McGrane, S.; Scharff, R.J.; Tretiak, S. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2016, 120, 519–526. [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Fernando, R.; Abeysekera, C.; Homayoon, Z.; Bowman, J.M.; Suits, A.G. J. Chem. Phys., 2014, 140, 054305. [CrossRef]

- Annesley, C.J.; Randazzo, J.B.; Klippenstein, S.J.; Harding, L.B.; Jasper, A.W.; Georgievskii, Y.; Ruscic, B.; Tranter, R.S. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2015, 119, 7872–7893. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodtke, A.M.; Hintsa, E.J.; Lee, Y.T. J. Phys. Chem., 1986, 90, 3549–3558. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Guo, Y.Q.; Bernstein, E.R. J. Chem. Phys., 2012, 136, 024321. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.Q.; Bhattacharya, A.; Bernstein, E.R. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2009, 113, 85–96. [CrossRef]

- Matsugi, A.; Shiina, H. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2017, 121, 4218–4224. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, D.; Lahankar, S.A.; Lee, S.K.; Chambreau, S.D.; Suits, A.G.; Zhang, X.; Rheinecker, J.; Harding, L.B.; Bowman, J.M. Science, 2004, 306, 1158–1161. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, N.; Suits, A.G. J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2011, 2, 642–647. [CrossRef]

- Suits, A.G. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., 2020, 71, 77–100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, J.G.; Vayner, G.; Lourderaj, U.; Addepalli, S.V.; Kato, S.; W. A. deJong; Windus, T.L.; Hase, W.L. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2007, 129, 9976–9985. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz, A.E.; Camden, J.P.; Chiou, A.S.; Ausfelder, F.; Chawla, N.; Hase, W.L.; Zare, R.N. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 127, 16368–16369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourderaj, U.; Park, K.; Hase, W.L. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem., 2008, 27, 361–403. [CrossRef]

- Suits, A.G. Acc. Chem. Res., 2008, 41, 873–881. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.M.; Shepler, B.C. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., 2011, 62, 531–553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, J.M.; Houston, P.L. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2017, 46, 7615–7624. [CrossRef]

- Houston, P.L.; Kable, S.H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2006, 103, 16079–16082. [CrossRef]

- Harding, L.B.; Klippenstein, S.J.; Jasper, A.W. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2007, 9, 4055–4070. [CrossRef]

- Heazlewood, B.R.; Jordan, M.J.T.; Kable, S.H.; Selby, T.M.; Osborn, D.L.; Shepler, B.C.; Braams, B.J.; Bowman, J.M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2008, 105, 12719–12724. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, B.O., in Advances in Chemical Physics; Ab initio Methods in Quantum Chemistry II, ed. K. P. Lawley, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 1987, ch. 69, p. 399. The Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field Method and Its Applications in Electronic Structure Calculations.

- Roos, B.O.; Taylor, P.R.; Siegbahn, P.E.M. Chem. Phys., 1980, 48, 157–173. [CrossRef]

- Roos, B.O. Int. J. Quantum Chem., 1980, 18, 175–189. [CrossRef]

- Siegbahn, P.E.M.; Almlo, J.; Heiberg, A.; Roos, B.O. J. Chem. Phys., 1981, 74, 2384–2396. [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.-J.; Meyer, W. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 73, 2342–2356. [CrossRef]

- Werner, H.-J.; Meyer, W. J. Chem. Phys., 1981, 74, 5794–5801. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J. Int. J. Quantum. Chem., 2011, 111, 3267–3272. [CrossRef]

- Roos, B.O.; Andersson, K.; Fu, M.P.; P. Å. Malmqvist; Serrano-Andre, L.; Pierloot, K.; Mercha, M. Adv. Chem. Phys., 1996, 93, 219–331. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, J.; Malmqvist, P.-Å.; Roos, B.O.; Serrano-Andrés, L. Chem. Phys. Lett., 1998, 288, 299–306. [CrossRef]

- MOLCAS 8. 4; Veryazov, V.; Widmark, P.-O.; Serrano-Andrés, L.; Lindh, R.; Roos, B.O. Int. J. Quantum Chem., 2004, 100, 626–635. [Google Scholar]

- MOLCAS 8. 4; Aquilante, F.; Autschbach, J.; Carlson, R.K.; Chibotaru, L.F.; Delcey, M.G.; De Vico, L.; Galván, I.F.; Ferré, N.; Frutos, L.M.; Gagliardi, L.; Garavelli, M.; Giussani, A.; Hoyer, C.E.; Manni, G.L.; Lischka, H.; Ma, D.; Malmqvist, P.Å.; Müller, T.; Nenov, A.; Olivucci, M.; Pedersen, T.B.; Peng, D.; Plasser, F.; Pritchard, B.; Reiher, M.; Rivalta, I.; Schapiro, I.; Segarra-Martí, J.; Stenrup, M.; Truhlar, D.G.; Ungur, L.; Valentini, A.; Vancoillie, S.; Veryazov, V.; Vysotskiy, V.P.; Weingart, O.; Zapata, F.; Lindh, R. J. Comp. Chem. 2016, 37, 506–541. [Google Scholar]

- Galván, I.F.; et al. OpenMolcas: From Source Code to Insight. J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2019, 15, 5925–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquilante, F.; et al. J. Chem. Phys., 2020, 152, 214117.

- Roos, B.O.; Lindh, R.; Malmqvist, P.-Å.; Veryazov, V.; Widmark, P.-O. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2004, 108, 2851–2858. [CrossRef]

- Roos, B.O.; Lindh, R.; Malmqvist, P.-Å.; Veryazov, V.; Widmark, P.-O. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2005, 109, 6575–6579. [CrossRef]

- Møller, C.; Plesset, M.S. Phys. Rev., 1934, 46, 618–622. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. Theor Chem Account, 2008, 120, 215–241. [CrossRef]

- Gaussian 16, Revision C.02, Frisch, M.J. et al. Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Weigend, F. . Ahlrichs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.; Algarra, M. J. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 9431–9437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Peláez, D.; Soto, J.; Serrano-Andrés, L. J. Chem. Phys., 2004, 121, 4127–4132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Peláez, D.; Soto, J. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2005, 109, 7172–7180. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.; Peláez, D.; Otero, J.C.; Avila, F.J.; Arenas, J.F. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2009, 11, 2631–2639. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Peng, J.W.; Zhu, Y.F.; Hu, D.P.; Lan, Z.G. J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2023, 14, 6542–6549. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Peng, J.W.; Hu, D.P.; Xu, C.; Lan, Z.G. Chin. J. Chem. Phys., 2022, 35, 451–460. [CrossRef]

- Verlet, L. Phys. Rev., 1967, 159, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Swope, W.C.; Andersen, H.C.; Berens, P.H.; Wilson, K.R. J. Chem. Phys., 1982, 76, 637–649. [CrossRef]

- Schaftenaar, G.; Noordik, J.H. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des., 2000, 14, 123–134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allouche, A.R. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 174–182. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, B.M.; Gordon, M.S. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 1998, 16, 133–138. [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.; Peláez, D.; Algarra, M. J. Chem. Phys. 2023, 158, 204301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, D.; Avila, F.J.; López-Tocón, I.; Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Soto, J. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 7764–7771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.; Otero, J.C.; Avila, F.J.; Peláez, D. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 2389–2396. [CrossRef]

- Soto, J. J. Phys. Chem. A, 2022, 126, 8372–8379. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peláez, D.; Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Soto, J. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 164311. [CrossRef]

- Soto, J.; Arenas, J.F.; Otero, J.C.; Peláez, D. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 8221–8226. [CrossRef]

- Ruscic, B.; Pinzon, R.E.; Morton, M.L.; von Laszevski, G.; Bittner, S.J.; Nijsure, S.G.; Amin, K.A.; Minkoff, M.; Wagner, A.F. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 9979–9997. [CrossRef]

- Ruscic, B.; Pinzon, R.E.; von Laszewski, G.; Kodeboyina, D.; Burcat, A.; Leahy, D.; Montoy, D.; Wagner, A.F. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2005, 16, 561–570. [CrossRef]

- Ruscic, B.; Bross, D.H. Active Thermochemical Tables (ATcT), values based on ver. 1.124 of the Thermochemical Network (2022). Available online: https://atct.anl.gov/Thermochemical Data/version 201.124/ version 1.124/.

- Cox, A.P.; Waring, S. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. II 1972, 68, 1060–1071. [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.H.; Corkill, M.J.; Cox, A.P. J. Phys. Chem. 1979, 83, 1473–1482; Veken, B.J.; Maas, R.; Guirgis, G.A.; Stidham, G.A.; Sheehan, T.G.; Durig, J.R.. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 4029–4039.

- Turner, P.H.; Cox, A.P. . Dipole Moment of Acetaldehyde. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. II 1978, 74, 533–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 9781–9786. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.; Peláez, D.; Otero, J.C. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 044307. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.K.; Li, J.; Li, Q.S.; Li, Z.S. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 6266–6273. [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Li, Q.S. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 8074–8081. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.L.; Migani, A.; Li, Q.S.; Li, Z.S.; Blancafort, L. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 1181–1188. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, J.; Algarra, M.; Peláez, D. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 5109–5115. [CrossRef]

- Arenas, J.F.; Marcos, J.I.; López-Tocón, I.; Otero, J.C.; Soto, J. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 2282–2289. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Blahous III; Yates, B.F.; Xie, Y.; Schaefer, H.F., III. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 93, 8105–8109. [Google Scholar]

| Reaction | Method | ΔdGa | ΔdEe,b | ΔdHc |

| CH3NO2(g) → CH3(g) + NO2(g) | CASPT2 | 65.95 | ||

| (0 K) | 58.76 | 58.76 | ||

| [59.16]d | ||||

| (298.15 K) | 50.83 | 60.10 | ||

| [61.00] | ||||

| MP2/HF | 66.61 | |||

| (0 K) | 63.71 | 63.71 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 56.70 | 65.06 | ||

| M06-2X | 67.93 | |||

| (0 K) | 60.51 | 60.51 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 53.35 | 61.93 | ||

| t-CH3ONO(g) →CH3O(g)+NO(g) | CASPT2 | 46.48 | ||

| (0 K) | 42.60 | 42.60 | ||

| [41.11] | ||||

| (298.15 K) | 33.13 | 43.99 | ||

| [42.32] | ||||

| MP2/HF | 51.10 | |||

| (0 K) | 49.28 | 49.28 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 39.79 | 50.69 | ||

| M06-2X | 42.63 | |||

| (0 K) | 37.86 | 37.86 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 28.31 | 39.40 | ||

| CH3NO2(g)→CH3NO(g)+O(3P)(g) | CASPT2 | 99.53 | ||

| (0 K) | 95.32 | 95.32 | ||

| [92.83] | ||||

| (298.15 K) | 88.19 | 96.47 | ||

| [94.35] | ||||

| MP2/HF | 104.88 | |||

| (0 K) | 100.44 | 100.44 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 93.46 | 101.57 | ||

| M06-2X | 96.82 | |||

| (0 K) | 92.53 | 92.53 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 85.47 | 93.68 |

| Reaction | ΔaGa | ΔaEeb | ΔaHc | ΔrHd | |

| CH3NO2(g) t-CH3ONO(g) | CASPT2 | 69.25 | |||

| (0 K) | 66.31 | 66.31 | 2.55 | ||

| [1.99]e | |||||

| (298.15 K) | 66.66 | 66.42 | 2.66 | ||

| [2.45] | |||||

| MP2 | 71.84 | ||||

| (0 K) | 69.19 | 69.19 | 6.10 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 69.91 | 69.12 | 5.91 | ||

| M06-2X | 73.15 | ||||

| (0 K) | 70.77 | 70.77 | 2.10 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 71.33 | 70.77 | 2.44 | ||

| CH3NO2(g) CH2N(O)OH(g) | CASPT2 | 66.54 | |||

| (0 K) | 63.01 | 63.01 | 12.88 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 64.98 | 62.54 | 12.76 | ||

| MP2 | 66.35 | ||||

| (0 K) | 62.86 | 62.86 | 16.32 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 62.86 | 62.95 | 16.20 | ||

| M06-2X | 65.66 | ||||

| (0 K) | 62.19 | 62.19 | 12.52 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 63.25 | 61.77 | 12.33 | ||

| t-CH3ONO(g) CH2O(g) + HNO(g) | CASPT2 | 43.80 | |||

| (0 K) | 38.76 | 38.76 | 14.34 | ||

| [13.62] | |||||

| (298.15 K) | 38.90 | 38.68 | 15.97 | ||

| [14.85] | |||||

| MP2 | 41.94 | ||||

| (0 K) | 37.69 | 37.69 | 13.42 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 37.27 | 37.99 | 15.06 | ||

| M06-2X | 49.92 | ||||

| (0 K) | 45.88 | 45.88 | 14.92 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 46.73 | 45.54 | 16.06 | ||

| t-CH3ONO(g) c-CH3ONO(g) | CASPT2 | 12.12 | |||

| (0 K) | 11.62 | 11.62 | -0.86 | ||

| [-0.74] | |||||

| (298.15 K) | 11.47 | 12.28 | -0.60 | ||

| [-0.70] | |||||

| MP2 | 11.26 | ||||

| (0 K) | 10.63 | 10.63 | -1.11 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 10.42 | 10.75 | -0.94 | ||

| M06-2X | 10.95 | ||||

| (0 K) | 10.48 | 10.48 | -1.29 | ||

| (298.15 K) | 11.46 | 9.99 | -1.66 |

| ||||||

| Internal Coord.a,b,c |

CAS1 Loose |

CAS2 Tight |

CASPT2 Tight |

Ld CAS1 |

Td CAS2 |

Td CASPT2 |

| R2,1 | 3.565 | 1.945 | 1.890 | 3426 | 3435 | 3300 |

| R3,2 | 1.173 | 1.321 | 1.317 | 3425 | 3405 | 3258 |

| A3,2,1 | 78.6 | 73.8 | 72.0 | 3245 | 3263 | 3126 |

| R4,2 | 1.173 | 1.202 | 1.202 | 1921 | 1592 | 1531 |

| A4,2,1 | 92.5 | 151.2 | 144.0 | 1524 | 1558 | 1506 |

| Dh4,2,1,3 | -134.0 | 121.1 | 114.1 | 1523 | 1538 | 1461 |

| R5,1 | 1.070 | 1.069 | 1.077 | 1479 | 1360 | 1280 |

| A5,1,2 | 107.4 | 99.6 | 98.9 | 819 | 1118 | 1106 |

| Dh5,1,2,4 | 42.3 | -149.2 | -148.3 | 236 | 960 | 933 |

| R6,1 | 1.070 | 1.071 | 1.082 | 106 | 919 | 916 |

| A6,1,2 | 76.3 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 80 | 711 | 721 |

| Dh6,1,2,5 | 117.6 | 115.7 | 115.0 | 65 | 461 | 494 |

| R7,1 | 1.070 | 1.069 | 1.081 | 38 | 178 | 214 |

| A7,1,2 | 88.8 | 117.6 | 120.7 | 13 | 131 | 143 |

| Dh7,1,2,5 | -121.2 | -125.8 | -126.9 | 52 i | 1066 i | 990 i |

| R3,1 | 3.525 | 2.023 | 1.942 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).