Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

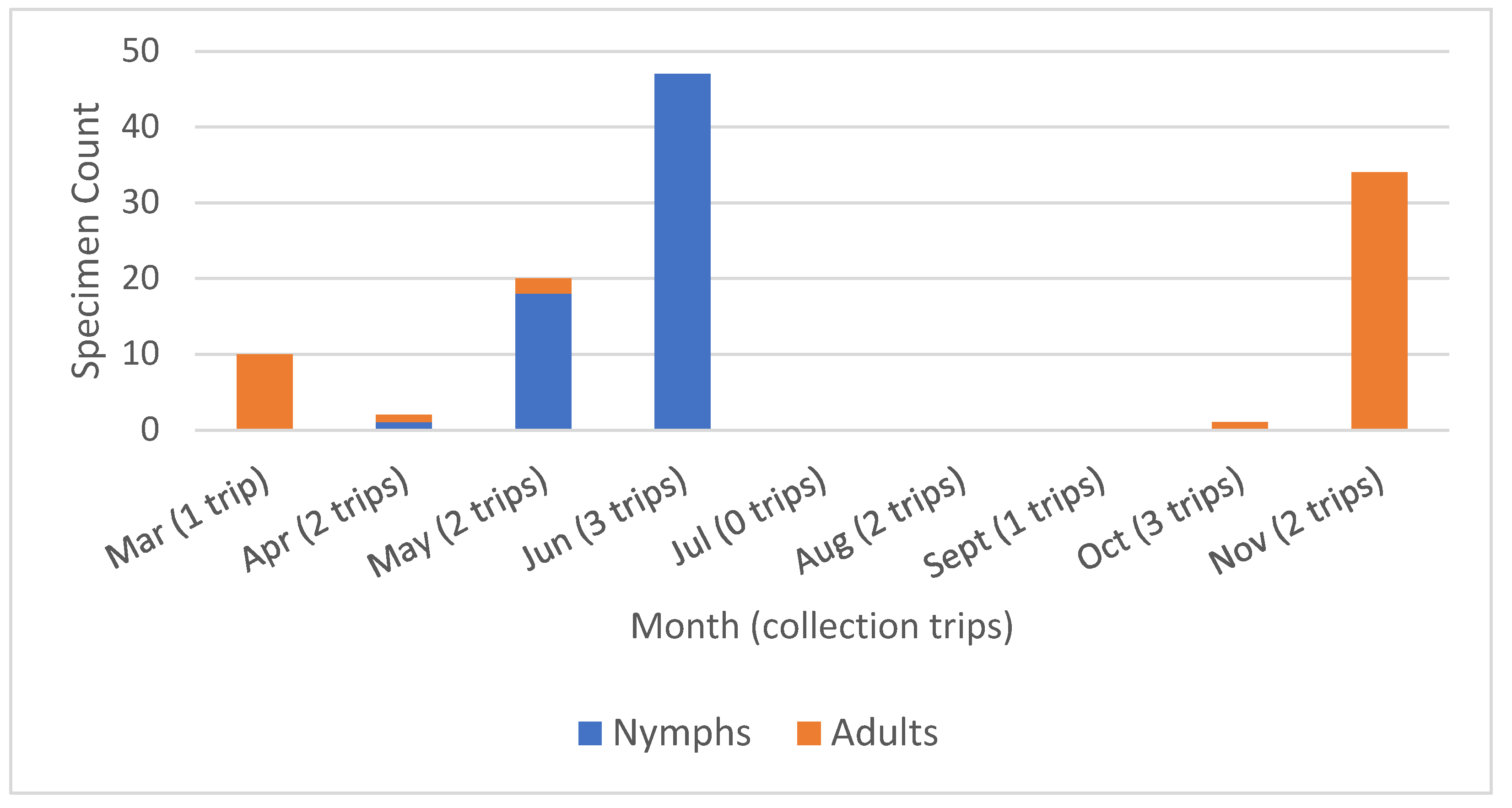

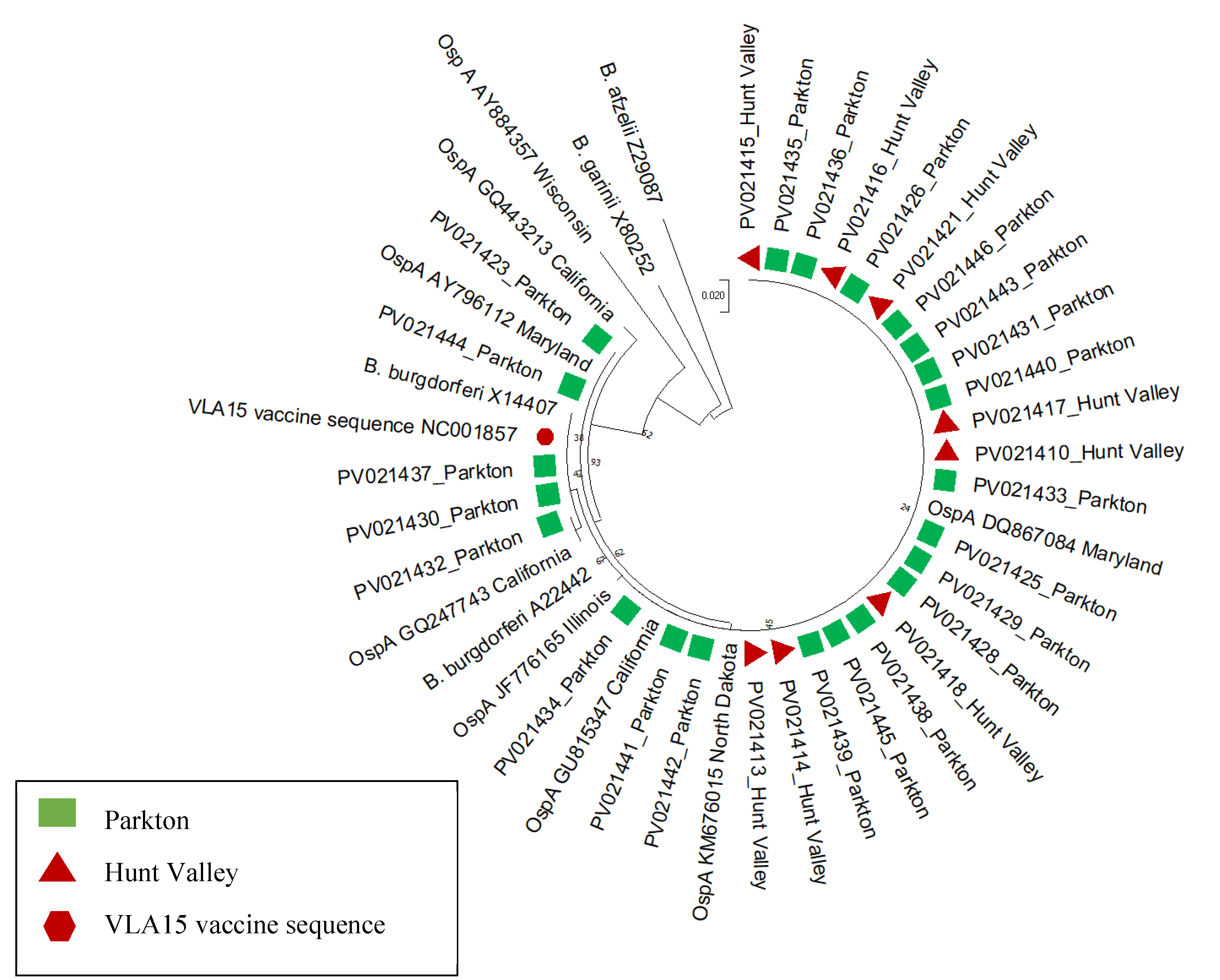

Reports of tick-borne diseases are on the rise globally, with Lyme disease as the most prevalent vector-borne disease in the United States. Tick and tick-borne pathogen distributions have been expanding, increasing the populations at risk for tick-vectored pathogens. In endemic regions, such as Maryland in the eastern United States, individuals and homeowners are concerned about the personal risk of exposure to these vectors and pathogens. In response, we carried out a pilot study at two residential properties in Baltimore County, Maryland. Tick drag collections were carried out March-December 2023 and resulted in the capture of 139 ticks. Collections were comprised of 114 Ixodes scapularis, 7 Dermacentor variabilis, and 18 invasive Haemaphysalis longicornis. Pathogen screening of the Ix. scapularis using qPCR and PCR revealed 42 (36.8%) infected with Borrelia burgdorferi and 3 infected with Anaplasma phagocytophilum. One tick was co-infected with both pathogens. Phylogenetic analysis of OspA genetic variability of B. burgdorferi revealed little variation both between samples and with reference sequences. The overall B. burgdorferi infection rate was higher than has been previously reported in Maryland. Whether this reflects an increase, represents variability between regional studies or is biased by relatively small sample sizes is unknown. The findings of this pilot study highlight the need for more robust tick and tick-borne pathogen surveillance in the mid-Atlantic region.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites and Collections

2.2. Nucleic Acid Extraction

2.3. Pathogen Detection

2.4. Amplification and Gel Visualization of ospA

2.5. Sequence Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Specimen Collection

3.2. Pathogen Detection, Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenberg, R.; Lindsey, N.P.; Fischer, M.; Gregory, C.J.; Hinckley, A.F.; Mead, P.S.; et al. Vital Signs: Trends in reported vectorborne disease cases - United States and Territories, 2004-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018, 2018. 67, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease Surveillance Data 2024 [updated December 17, 2024; cited 2025 January 26, 2025]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/data-research/facts-stats/surveillance-data-1.html#cdc_data_surveillance_section_2-dashboard-data-files.

- Kugeler, K.J.; Schwartz, A.M.; Delorey, M.J.; Mead, P.S.; Hinckley, A.F. Estimating the frequency of Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, A.M.; Kugeler, K.J.; Nelson, C.A.; Marx, G.E.; Hinckley, A.F. Use of commercial claims data for evaluating trends in Lyme disease diagnoses, United States, 2010-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021, 27, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrion, E.R.; Aucott, J.; Lemke, K.W.; Weiner, J.P. Health care costs, utilization and patterns of care following Lyme disease. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0116767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac, S.; da Silva, S.R.; Sander, B. The economic burden of Lyme disease and the cost-effectiveness of Lyme disease interventions: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0210280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.F.; Burgdorfer, W.; Barbour, A.G. Bacteriophage in the Ixodes dammini spirochete, etiological agent of Lyme disease. J Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 1436–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, S.J.; Allan, B.F.; Miller, J.R. The role of Ixodes scapularis, Borrelia burgdorferi and wildlife hosts in Lyme disease prevalence: A quantitative review. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018, 9, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, L.; Eisen, R.J. Changes in the geographic distribution of the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis, in the United States. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2023, 14, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorfer, W.; Lane, R.S.; Barbour, A.G.; Gresbrink, R.A.; Anderson, J.R. The western black-legged tick, Ixodes pacificus: a vector of Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985, 34, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.; Kelly, P.H.; Davis, J.; Major, M.; Moisi, J.C.; Stark, J.H. Historical summary of tick and animal surveillance studies for Lyme disease in Canada, 1975-2023: A Scoping Review. Zoonoses Public Health. 2025, 72, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.E.; Winter, J.M.; Cantoni, J.L.; Cozens, D.W.; Linske, M.A.; Williams, S.C.; et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of Ixodes scapularis and tick-borne pathogens across the northeastern United States. Parasit Vectors. 2024, 17, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilbert, W.; Matella, A. Tick-borne diseases. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2024, 42, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadori, A.; Ritz, N.; Zimmermann, P. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease in children. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2023, 108, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Vicente, S.; Tokarz, R. Tick-borne co-infections: Challenges in molecular and serologic diagnoses. Pathogens. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.P.; Wilkinson, M.M.; Niesobecki, S.; Rutz, H.; Meek, J.I.; Niccolai, L.; et al. Barriers to the uptake of tickborne disease prevention measures: Connecticut, Maryland 2016-2017. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2025, 31, E52–E60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, D.; Sulik, A.; Raciborski, F.; Krasnodebska, M.; Gebarowska, J.; Stalewska, A.; et al. Barriers and predictors of Lyme disease vaccine acceptance: A cross-sectional study in Poland. Vaccines (Basel). 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigrovic, L.E.; Thompson, K.M. The Lyme vaccine: a cautionary tale. Epidemiol Infect. 2007, 135, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comstedt, P.; Schuler, W.; Meinke, A.; Lundberg, U. The novel Lyme borreliosis vaccine VLA15 shows broad protection against Borrelia species expressing six different OspA serotypes. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0184357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, S.K.; Schneider, M.; Dubischar, K.; Wagner, L.; Kadlecek, V.; Obersriebnig, M.; et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an 18-month booster dose of the VLA15 Lyme borreliosis vaccine candidate after primary immunisation in healthy adults in the USA: results of the booster phase of a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comstedt, P.; Hanner, M.; Schuler, W.; Meinke, A.; Lundberg, U. Design and development of a novel vaccine for protection against Lyme borreliosis. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e113294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, T.R.; LaQuier, F.W.; Barbour, A.G. Organization of genes encoding two outer membrane proteins of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi within a single transcriptional unit. Infect Immun. 1986, 54, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, T.R.; Mayer, L.W.; Barbour, A.G. A single recombinant plasmid expressing two major outer surface proteins of the Lyme disease spirochete. Science. 1985, 227, 645–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman, D.S.; Wang, P.W.; Wang, I.N.; Bosler, E.M.; Luft, B.J.; Dykhuizen, D.E. Multiple infections of Ixodes scapularis ticks by Borrelia burgdorferi as revealed by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996, 34, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.M.; Norris, D.E. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in Peromyscus leucopus, the primary reservoir of Lyme disease in a region of endemicity in southern Maryland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72, 5331–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlin, I.; Toledo, A. Emerging tick-borne pathogens of public health importance: a mini-review. J Med Microbiol. 2020, 69, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, R.J.; Eisen, L. The blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis: An increasing public health concern. Trends Parasitol. 2018, 34, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, L. Tick species infesting humans in the United States. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022, 13, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merten, H.A.; Durden, L.A. A state-by-state survey of ticks recorded from humans in the United States. J Vector Ecol. 2000, 25, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Milholland, M.T.; Eisen, L.; Nadolny, R.M.; Hojgaard, A.; Machtinger, E.T.; Mullinax, J.M.; et al. Surveillance of ticks and tick-borne pathogens in suburban natural habitats of central Maryland. J Med Entomol. 2021, 58, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, K.A.; Connally, N.P.; Hojgaard, A.; Jones, E.H.; White, J.L.; Hinckley, A.F. Abundance and infection rates of Ixodes scapularis nymphs collected from residential properties in Lyme disease-endemic areas of Connecticut, Maryland, and New York. J Vector Ecol. 2015, 40, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, T.C.; Orr, J.M.; Smith, J.D.; Arias, J.R.; Norris, D.E. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in multiple hard tick species from Fairfax County, Virginia. Vector-borne Zoon Dis. 2014, 14, 482-485. [CrossRef]

- Hojgaard, A.; Lukacik, G.; Piesman, J. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia microti, with two different multiplex PCR assays. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014, 5, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massung, R.F.; Slater, K.; Owens, J.H.; Nicholson, W.L.; Mather, T.N.; Solberg, V.B.; et al. Nested PCR assay for detection of granulocytic ehrlichiae. J Clin Microbiol. 1998, 36, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.I.; Norris, D.E. Co-circulating microorganisms in questing Ixodes scapularis nymphs in Maryland. J Vector Ecol. 2007, 32, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.M.; Swanson, K.I.; Schwartz, T.R.; Glass, G.E.; Norris, D.E. Mammal diversity and infection prevalence in the maintenance of enzootic Borrelia burgdorferi along the western Coastal Plains of Maryland. Vector-borne Zoon Dis. 2006, 6, 411-422. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008, 25, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryland Division of Natural Resources. First Confirmed Longhorned Tick Found in Maryland 2018 [updated August 7, 2018; cited 2025 January 26, 2025]. Available from: https://news.maryland.gov/dnr/2018/08/07/first-confirmed-longhorned-tick-found-in-maryland/.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Asian Longhorned Ticks 2024 [updated September 11, 2024; cited 2025 January 26, 2025]. Available from: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/asian-longhorned.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for babesiosis—United States, 2019 annual summary. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2021.

| Hunt Valley No. Collected | No. Positive at Hunt Valley | Parkton No. Collected | No. Positive at Parkton | Total Tick Counts | Total Positive Ticks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nymphs | 32 | 15 (46.9%) | 33 | 7 (21.2%) | 65 | 22 (33.8%) |

| Adults | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 47 | 19 (40.4%) | 49 | 20 (40.8%) |

| Total | 34 | 16 (47.1%) | 80 | 26 (32.5%) | 117 | 42 (36.8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).