Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

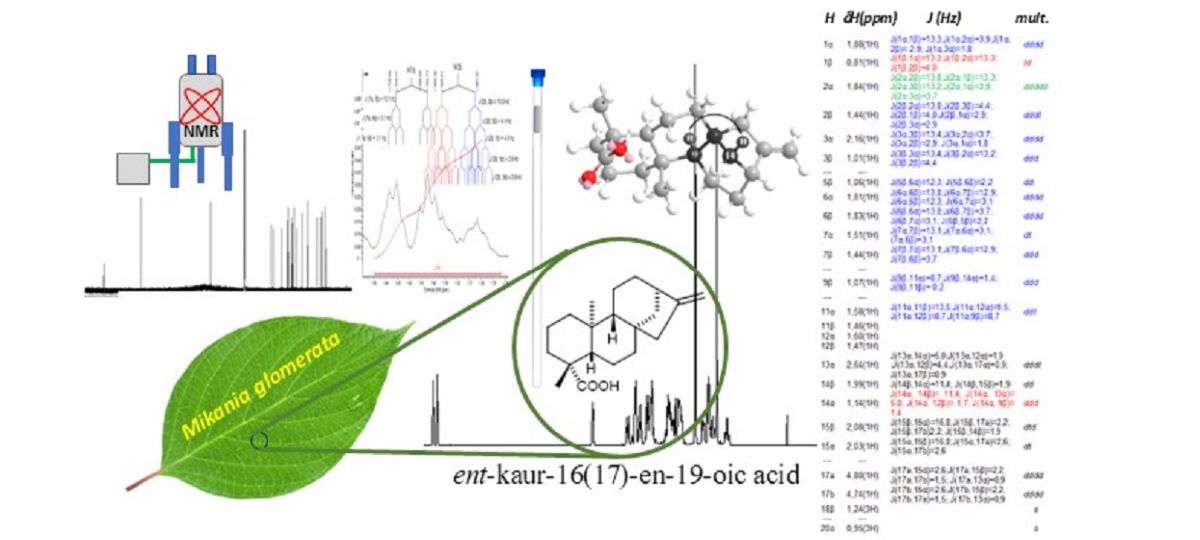

Isolation of ent-Kaurenoic Acid

NMR Experiments

NMR Spectra Processing

NMR Signal Simulations

Dataset Comparison to Structure

3. Results and Discussion

| C |

H |

CDCl3 δH (ppm) |

C6D6 δH (ppm) |

Coupling Constants (Hz) | Multiplicity |

| 1 | 1α | 1.88 (1H) | 1.74 (1H) | J(1α,1β)=13.3;J(1α,2α)=3.9;J(1α,2β)=2.9; J(1α,3α)=1.8 | dddd |

| 1β | 0.80 (1H) | 0.65 (1H) | J(1β,1α)=13.3;J(1β,2α)=13.3; J(1β,2β)=4.0 | td | |

| 2 | 2α | 1.85 (1H) | 2.06 (1H) | J(2α,2β)=13.8;J(2α,1β)=13.3; J(2α,3β)=13.2;J(2α,1α)=3.9; J(2α,3α)=3.7 | ddddd |

| 2β | 1.43 (1H) | 1.41 (1H) | J(2β,2α)=13.8;J(2β,3β)=4.4; J(2β,1β)=4.0;J(2β,1α)=2.9; J(2β,3α)=2.9 | dddt | |

| 3 | 3α | 2.17 (1H) | 2.34 (1H) | J(3α,3β)=13.4;J(3α,2α)=3.7;J(3α,2β)=2.9; J(3α,1α)=1.8 | dddd |

| 3β | 1.00 (1H) | 0.88 (1H) | J(3β,3α)=13.4;J(3β,2α)=13.2; J(3β,2β)=4.4 | ddd | |

| 4 | --- | ||||

| 5 | 5β | 1.03 (1H) | 0.85 (1H) | J(5β,6α)=12.3; J(5β,6β)=2.2 | dd |

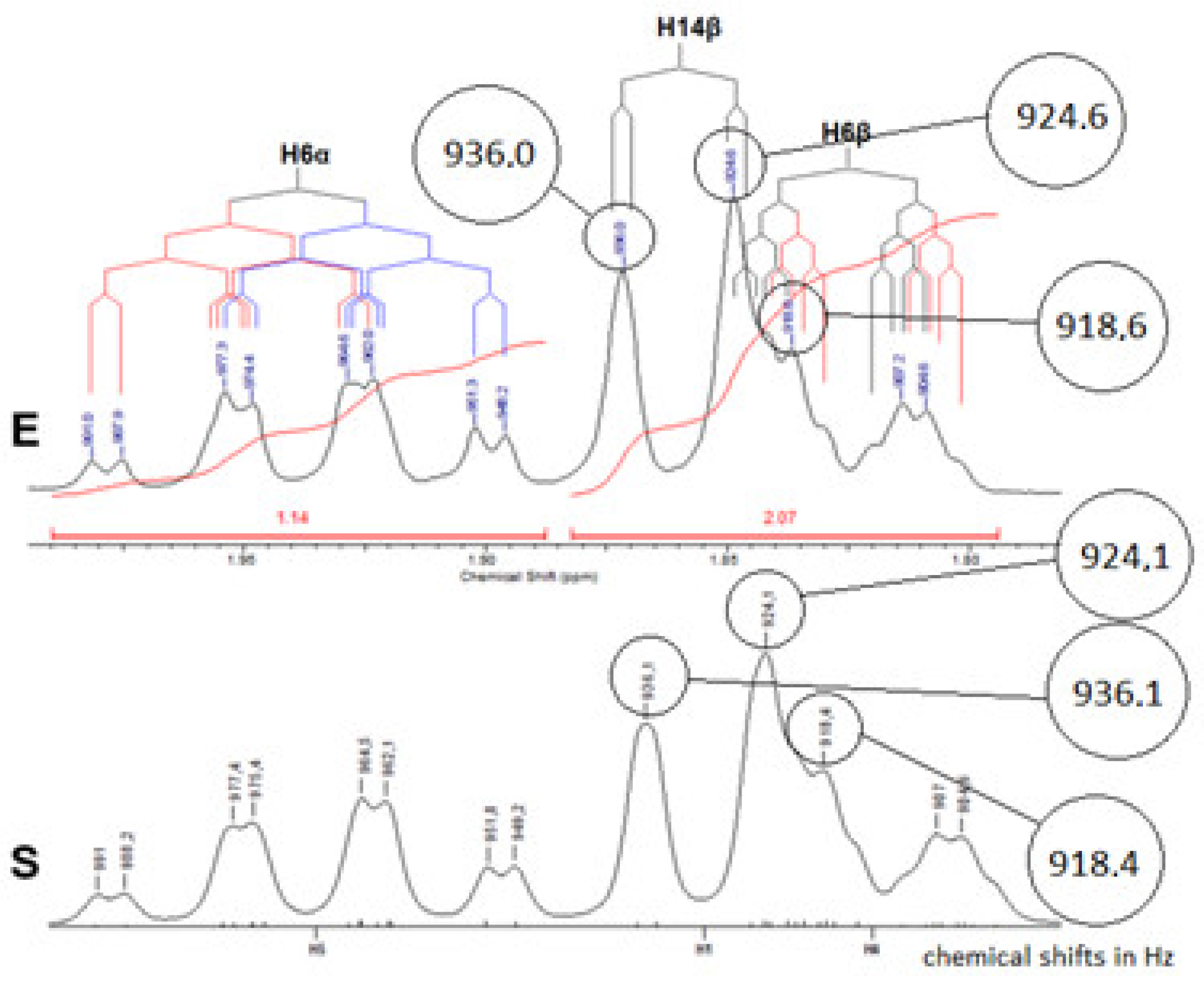

| 6 | 6α | 1.81 (1H) | 1.86 (1H) | J(6α,6β)=13.8;J(6α,7β)=12.9;J(6α,5β)=12.3; J(6α,7α)=3.1 | dddd |

| 6β | 1.75 (1H) | 1.84 (1H) | |||

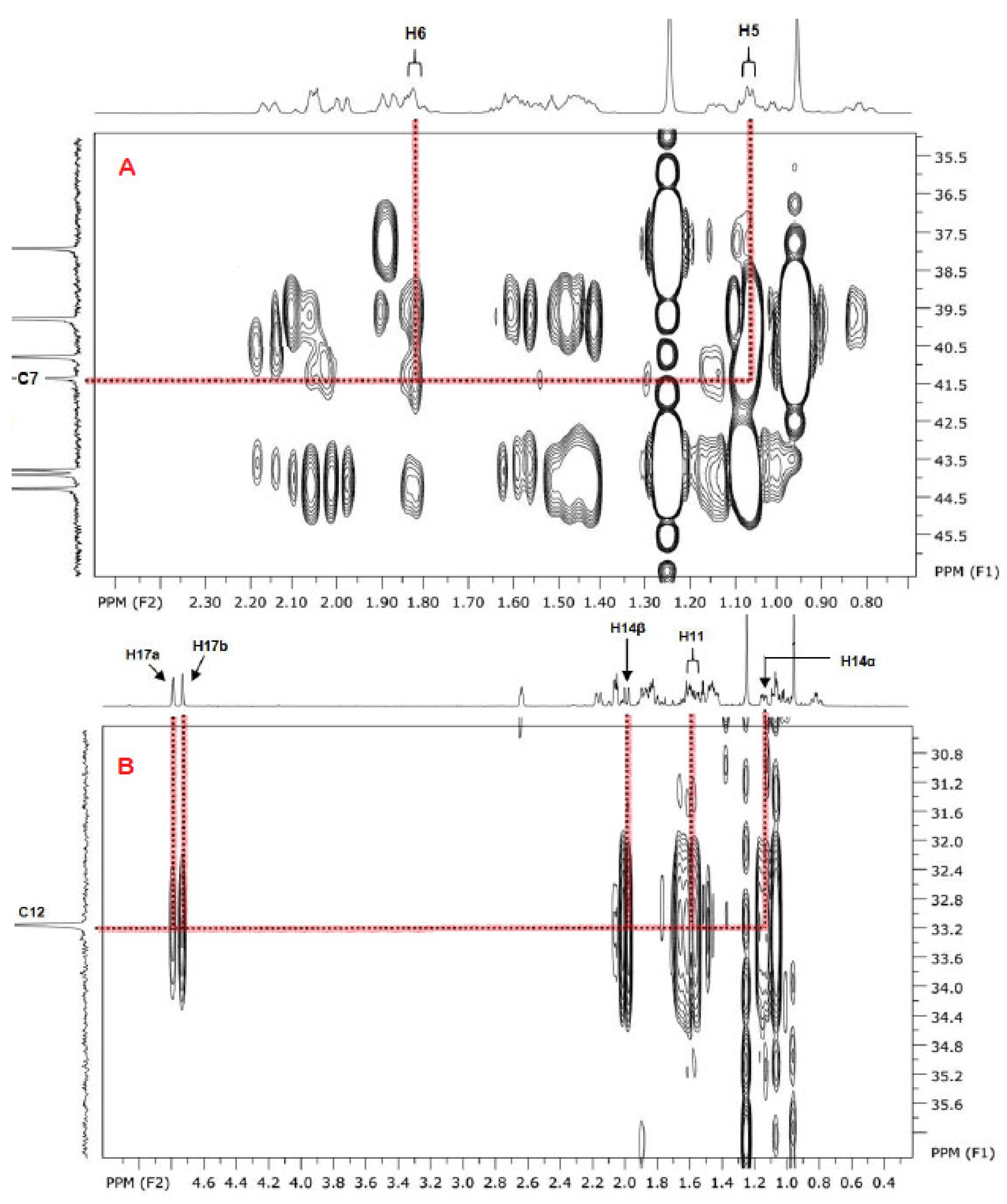

| 7 | 7α | 1.52 (1H) | 1.45 (1H) | J(7α,7β)=13.1;J(7α,6α)=3.1; (7α,6β)=3.1 | dt |

| 7β | 1.45 (1H) | 1.32 (1H) | |||

| 8 | --- | ||||

| 9 | 9β | 1.06 (1H) | 0.92 (1H) | J(9β,11α)=8.7; J(9β,11β)= 1.6; J(9β,14α)=1.4 | ddd |

| 10 | --- | ||||

| 11 | 11α | 1.58 (1H) | 1.68 (1H) |

J(11α,11β)=13.5;J(11α;12α)=9.5; J(11α;12β)=8.7;J(11α;9β)=8.7 |

ddt |

| 11β | 1.47 (1H) | ||||

| 12 | 12α | 1.63 (1H) | 1.52 (1H) | ||

| 12β | 1.45 (1H) | 1.49 (1H | |||

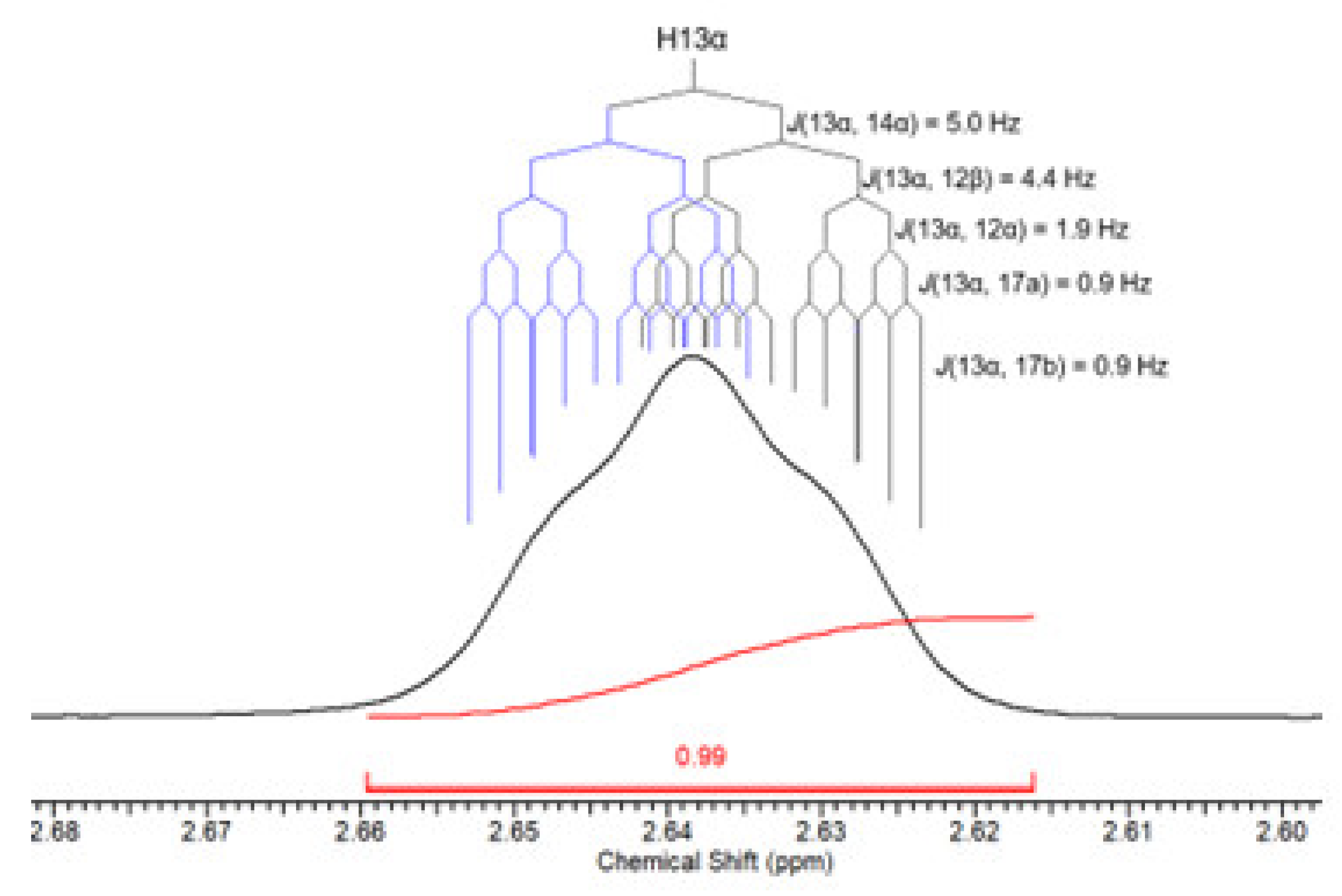

| 13 | 13α | 2.64 (1H) | 2,64 (1H) | J(13α,14α)=5.0;J(13α,12α)=1.9 ;J(13α,12β)=4.4,J(13α,17α)=0.9; J(13α,17β)=0.9 | dddt |

| 14 | 14β | 1.97 (1H) | 1.91 (1H) | J(14β,14α)=11.4; J(14β,15β)=1.9 | dd |

| 14α | 1.13 (1H) | 1.09 (1H) | J(14α, 14β)= 11.4; J(14α, 13α)= 5.0; J(14α, 12β)= 1.7; J(14α, 9β)= 1.4 | ddd | |

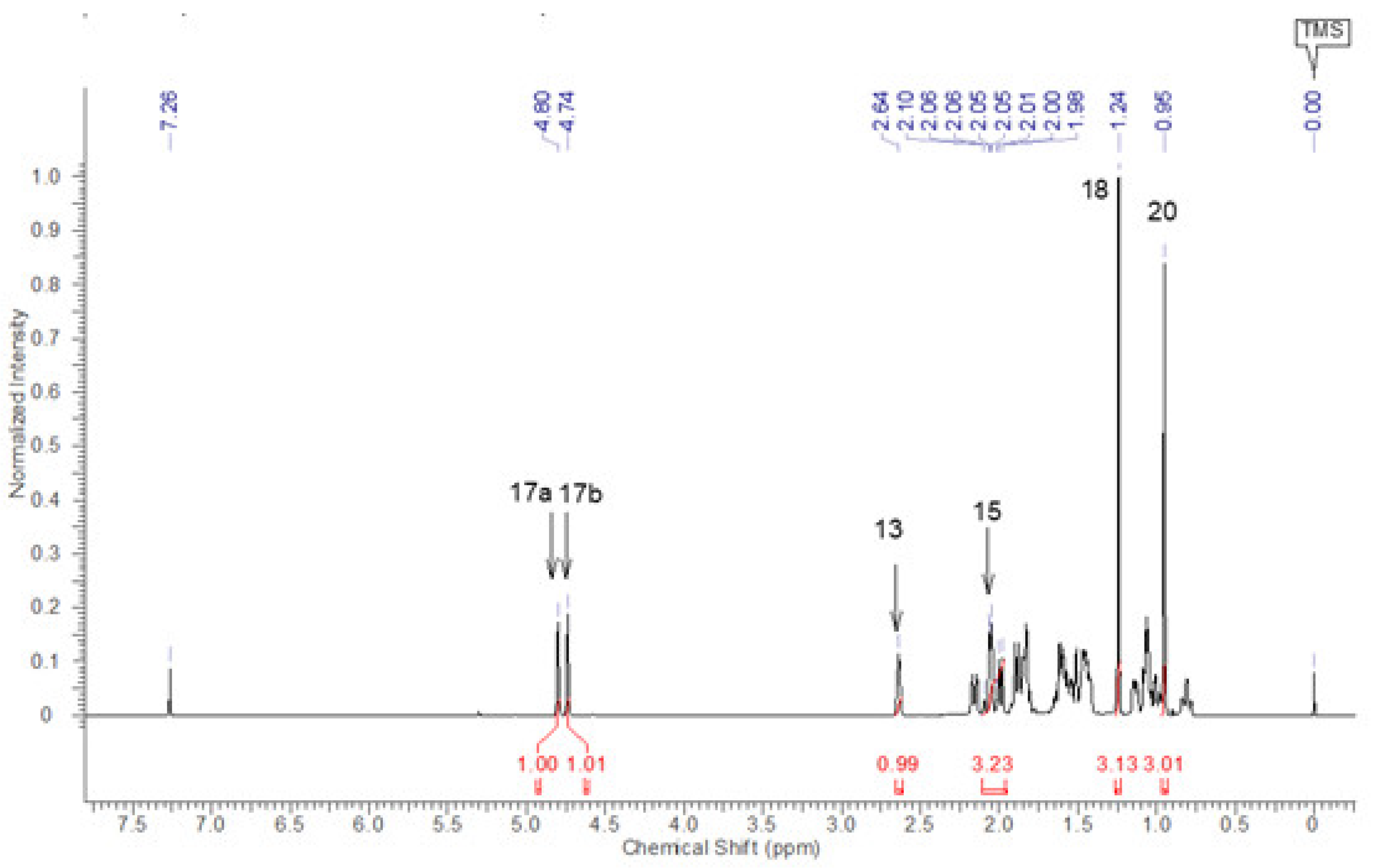

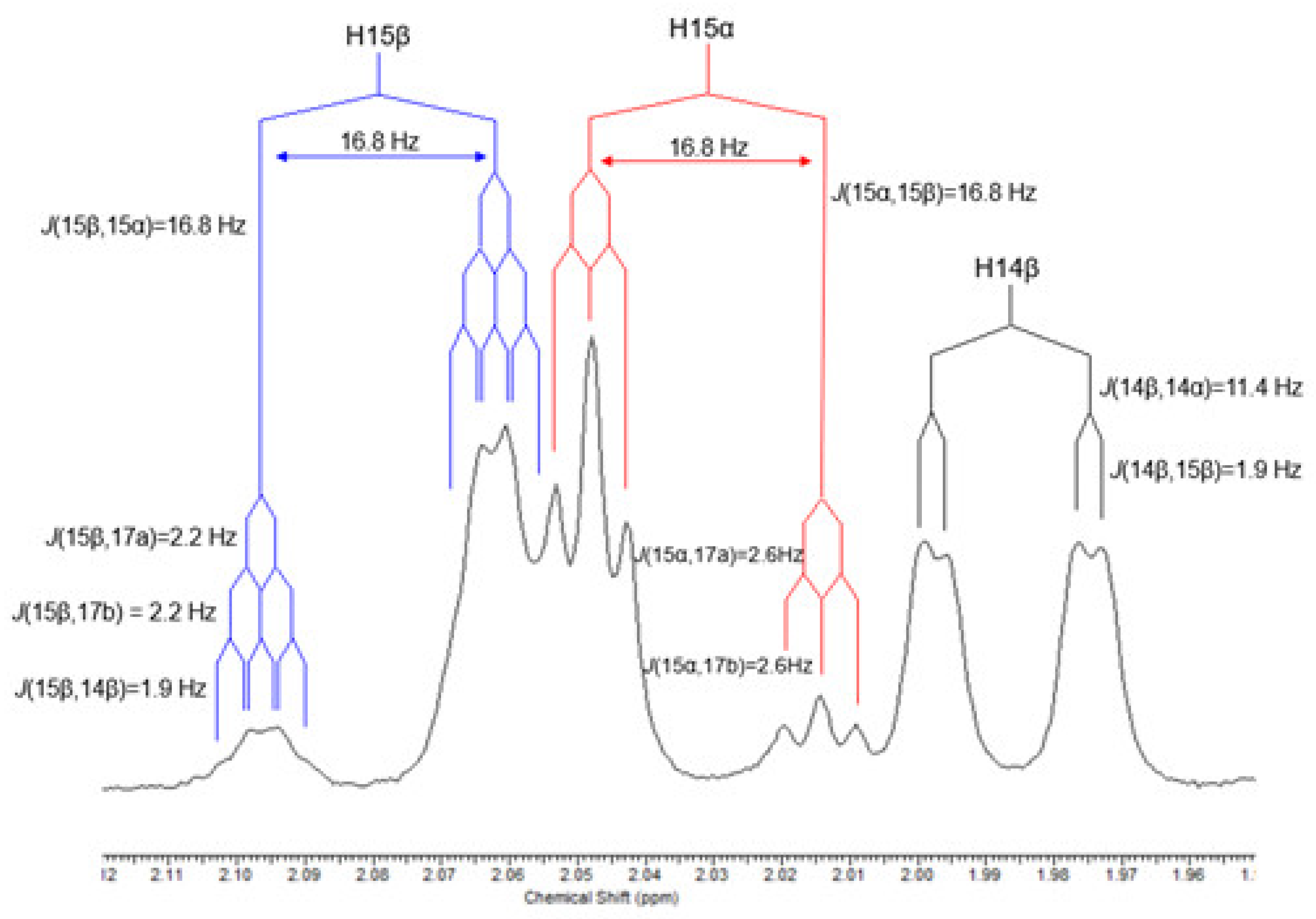

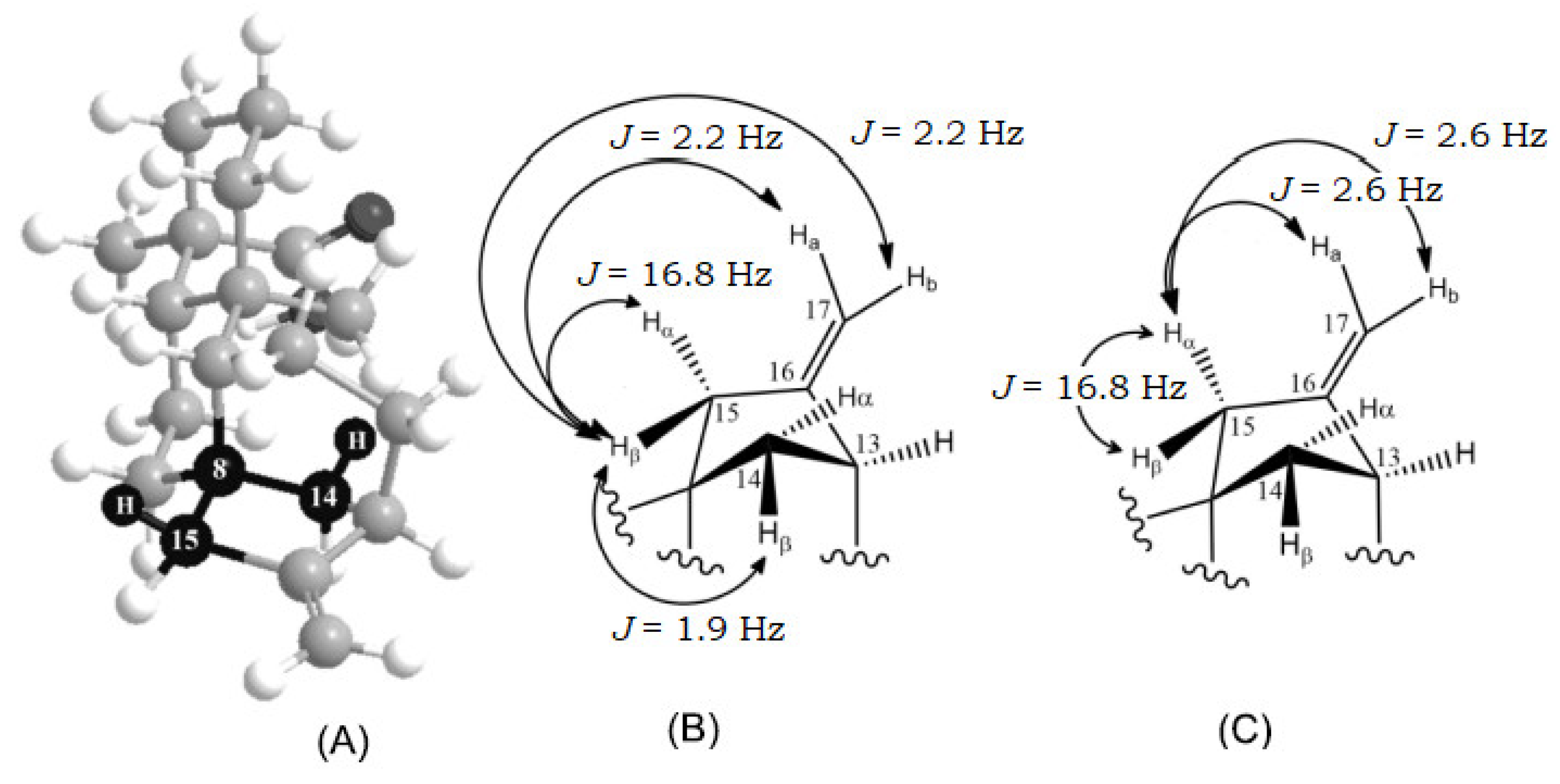

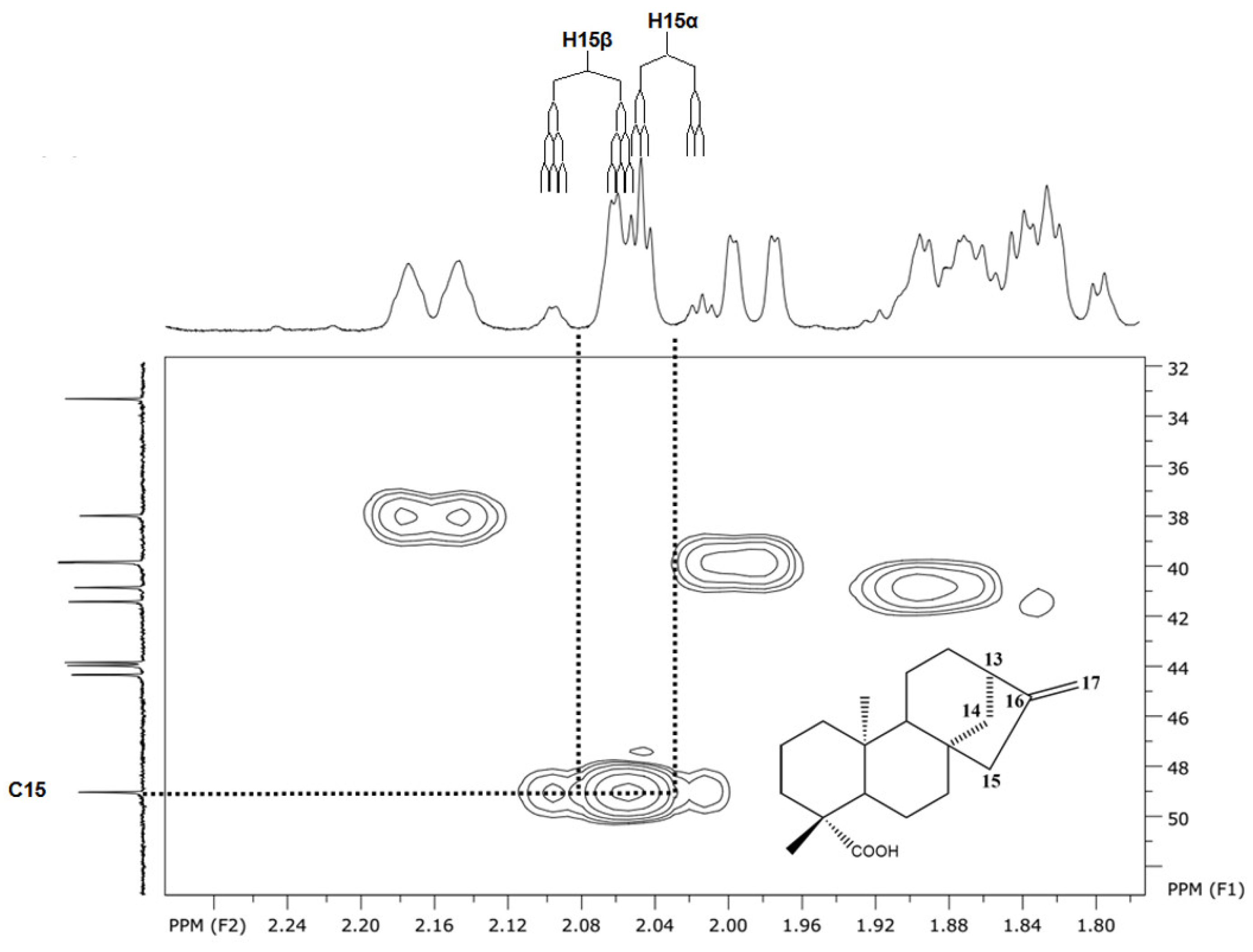

| 15 | 15β | 2.08 (1H) | 2.07 (1H) | J(15β,15α)=16.8;J(15β,17a)=2.2;J(15β,17b)2.2; J(15β,14β)=1.9 | dtd |

| 15α | 2.02 (1H) | 2.02 (1H) | J(15α,15β)=16.8;J(15α,17a)=2.6; J(15α,17b)=2.6 | dt | |

| 16 | --- | ||||

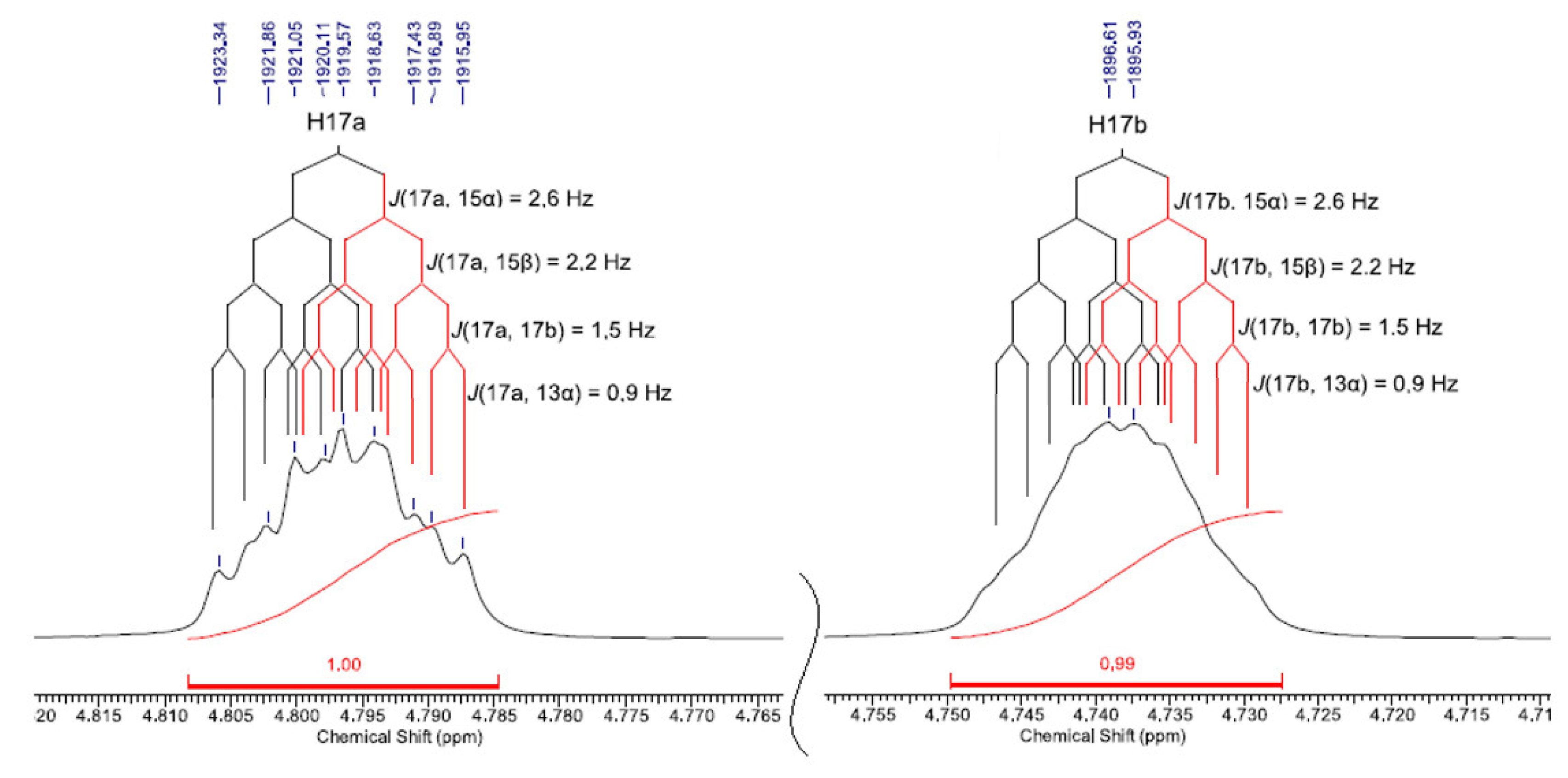

| 17 | 17a | 4.79 (1H) | 4.98 (1H) | J(17a,15α)=2.6;J(17a,15β)=2.2;J(17a,17b)=1.5; J(17a,13α)=0.9 | dddd |

| 17b | 4.74 (1H) | 4.93 (1H) | J(17b,15α)=2.6;J(17b,15β)=2.2;J(17b,17a)=1.5; J(17b,13α)=0.9 | dddd | |

| 18 | 18β | 1.17 (3H) | 1.11 (3H) | s | |

| 19 | --- | ||||

| 20 | 20α | 0.83 (3H) | 0.85 (3H) | s | |

| 21 | 21α | 3.64 (3H) | 3.35 (3H) | s |

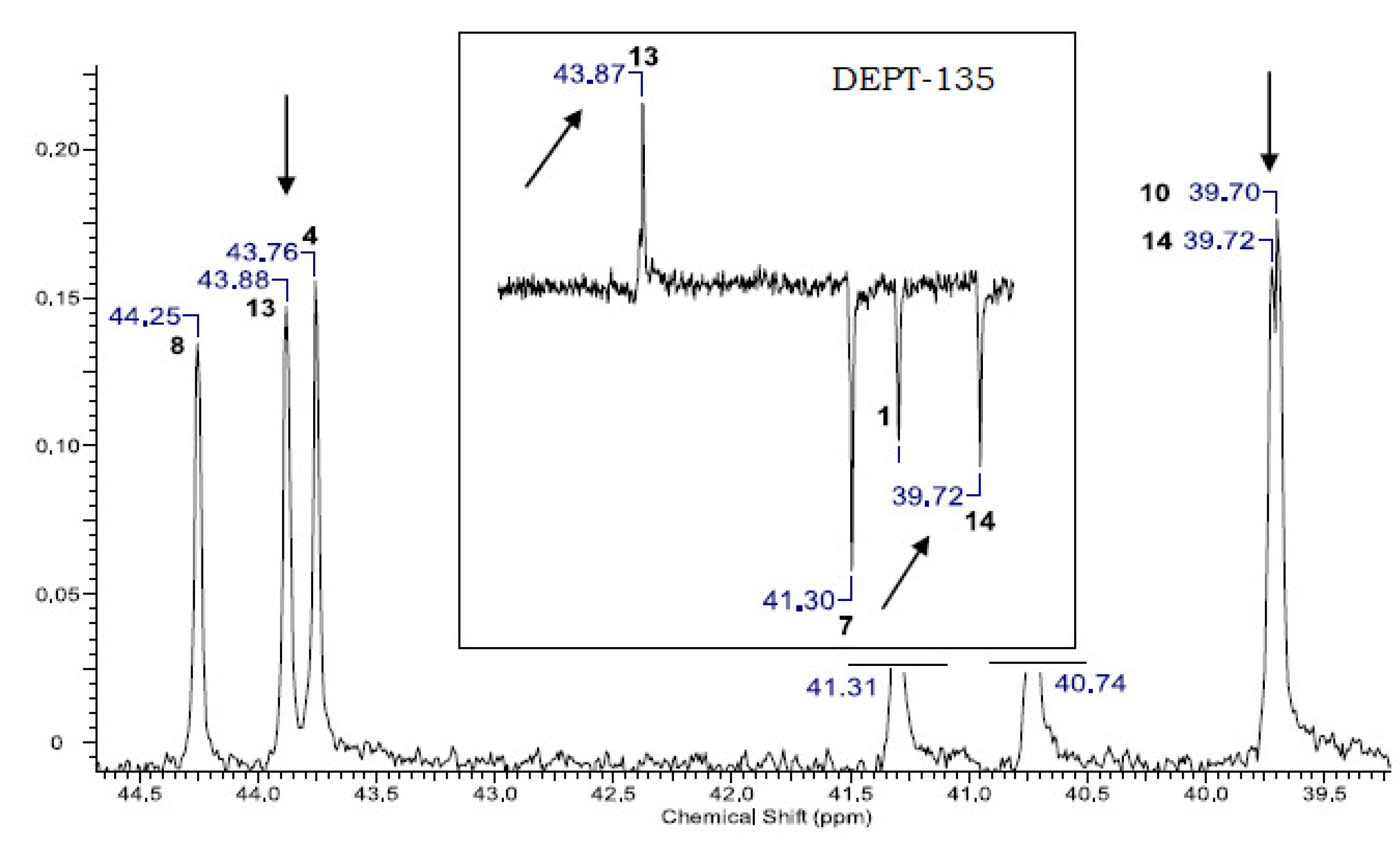

| C | CDCl3 δC (ppm) |

C6D6 δC (ppm) |

| 1 | 40.7 | 41.3 |

| 2 | 19.1 | 20.0 |

| 3 | 38.1 | 38.7 |

| 4 | 43.9 | 44.3 |

| 5 | 57.1 | 57.5 |

| 6 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| 7 | 41.2 | 41.9 |

| 8 | 44.2 | 44.7 |

| 9 | 55.1 | 55.7 |

| 10 | 39.4 | 40.0 |

| 11 | 18.3 | 19.1 |

| 12 | 33.1 | 33.8 |

| 13 | 43.8 | 44.8 |

| 14 | 39.6 | 40.3 |

| 15 | 48.8 | 49.7 |

| 16 | 155.8 | 156.0 |

| 17 | 103.1 | 103.9 |

| 18 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| 19 | 178.1 | 177.7 |

| 20 | 15.2 | 16.1 |

| 21 | 51.0 | 51.0 |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| 1H-NMR | Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| 13C-NMR | Carbon Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| COSY | Correlation Spectroscopy |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence |

| HMBC | Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation |

| g | Stands for “gradient” |

| FOMSC3 | First Order Multiplet Simulator/Checker - program |

| NMR_MultSim | NMR Multiplet Simulator - program |

| NP | Natural Products |

| KA | Kaurenoic acid |

| KAMe | Kaurenoic acid methyl ester |

| FFCLRP/USP | Philosophy, Science and Letters Faculty of Ribeirão Preto – University of São Paulo. |

References

- Zhang, F.-L.; Feng, T. Diterpenes Specially Produced by Fungi: Structures, Biological Activities, and Biosynthesis (2010–2020). Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, P.; Xia, J.; Zhang, H.; Lin, D.; Shao, Z. A Review of Diterpenes from Marine-Derived Fungi: 2009–2021. Molecules 2022, 27, 8303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, J.R. Diterpenoids. Nat Prod Rep 2009, 26, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniuk, O.; Maranha, A.; Salvador, J.A.R.; Empadinhas, N.; Moreira, V.M. Bi- and Tricyclic Diterpenoids: Landmarks from a Decade (2013–2023) in Search of Leads against Infectious Diseases. Nat Prod Rep 2024, 41, 1858–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Rahman, F.I.; Hussain, F.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Rahman, M.M. Antimicrobial Diterpenes: Recent Development From Natural Sources. Front Pharmacol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Lou, Y.; Mao, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, X. Plant Terpenoids: Biosynthesis and Ecological Functions. J Integr Plant Biol 2007, 49, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.C.F.S.; Morais, G.O.; da Silva, M.M.; Kovatch, P.Y.; Ferreira, D.S.; Esperandim, V.R.; Pagotti, M.C.; Magalhães, L.G.; Heleno, V.C.G. In Vitro Anti-Trypanosomal Potential of Kaurane and Pimarane Semi-Synthetic Derivatives. Nat Prod Res 2022, 36, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.S.; Castro-Pinto, D.B.; Machado, G.C.; Maciel, M.A.M.; Echevarria, A. Antileishmanial Activity and Trypanothione Reductase Effects of Terpenes from the Amazonian Species Croton Cajucara Benth (Euphorbiaceae). Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-J.; Sun, Y.; Sun, B.; Wang, X.-N.; Liu, S.-S.; Zhou, J.-C.; Ye, J.-P.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Lee, K.-H.; et al. Phytotoxic Cis-Clerodane Diterpenoids from the Chinese Liverwort Scapania Stephanii. Phytochemistry 2014, 105, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.-S.; Shao, L.-D.; Fu, L.; Xu, J.; Zhu, G.-L.; Peng, X.-R.; Li, X.-N.; Li, Y.; Qiu, M.-H. One-Step Semisynthesis of a Segetane Diterpenoid from a Jatrophane Precursor via a Diels–Alder Reaction. Org Lett 2016, 18, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardají, D.K.R.; da Silva, J.J.M.; Bianchi, T.C.; de Souza Eugênio, D.; de Oliveira, P.F.; Leandro, L.F.; Rogez, H.L.G.; Venezianni, R.C.S.; Ambrosio, S.R.; Tavares, D.C.; et al. Copaifera Reticulata Oleoresin: Chemical Characterization and Antibacterial Properties against Oral Pathogens. Anaerobe 2016, 40, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Kang, J.; Cao, X.; Sun, X.; Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; Guo, Y. Characterization of Diterpenes from Euphorbia Prolifera and Their Antifungal Activities against Phytopathogenic Fungi. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 5902–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa-Linares, V.C.; Brand, Y.M.; Agudelo-Gomez, L.S.; Tangarife-Castaño, V.; Betancur-Galvis, L.A.; Gallego-Gomez, J.C.; González, M.A. Anti-Herpetic and Anti-Dengue Activity of Abietane Ferruginol Analogues Synthesized from (+)-Dehydroabietylamine. Eur J Med Chem 2016, 108, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmistrova, O.; Perdomo, J.; Simões, M.F.; RiJo, P.; Quintana, J.; Estévez, F. The Abietane Diterpenoid Parvifloron D from Plectranthus Ecklonii Is a Potent Apoptotic Inducer in Human Leukemia Cells. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.C.F.; Matos, P.M.; Dias, H.J.; Aguiar, G. de P.; dos Santos, E.S.; Martins, C.H.G.; Veneziani, R.C.S.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Heleno, V.C.G. Variability of the Antibacterial Potential among Analogue Diterpenes against Gram-Positive Bacteria: Considerations on the Structure–Activity Relationship. Can J Chem 2019, 97, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. The Therapeutic Potential of Rosemary ( Rosmarinus Officinalis ) Diterpenes for Alzheimer’s Disease. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeda-Hirschmann, G.; Rodríguez, J.; Theoduloz, C.; Valderrama, J. Gastroprotective Effect and Cytotoxicity of Labdeneamides with Amino Acids. Planta Med 2011, 77, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Guo, Q.; Tu, P.; Chai, X. The Genus Casearia: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview. Phytochemistry Reviews 2015, 14, 99–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, M.J.; Reyes, C.P.; Jiménez, I.A.; Hayashi, H.; Tokuda, H.; Bazzocchi, I.L. Ent-Rosane and Abietane Diterpenoids as Cancer Chemopreventive Agents. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALVARENGA, S.A. V.; FERREIRA, M.J.P.; RODRIGUES, G. V.; EMERENCIANO, V.P. A General Survey and Some Taxonomic Implications of Diterpenes in the Asteraceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 2005, 147, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cacherat, B.; Hu, Q.; Ma, D. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Ent -Kaurane Diterpenoids. Nat Prod Rep 2022, 39, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, V.C.S.; Rocha, E.C.S.; Pavan, J.C.S.; Heleno, V.C.G.; de Lucca, E.C. Selective Oxidations in the Synthesis of Complex Natural Ent -Kauranes and Ent -Beyeranes. J Org Chem 2022, 87, 10462–10466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, Á.; Quílez del Moral, J.F.; Galisteo, A.; Amaro, J.M.; Barrero, A.F. Bioinspired Synthesis of Platensimycin from Natural Ent -Kaurenoic Acids. Org Lett 2023, 25, 5401–5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chagas-Paula, D.A.; Oliveira, R.B.; Rocha, B.A.; Da Costa, F.B. Ethnobotany, Chemistry, and Biological Activities of the Genus Tithonia (Asteraceae). Chem Biodivers 2012, 9, 210–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, C.; Aldana Mejía, J.A.; Ribeiro, V.P.; Gambeta Borges, C.H.; Martins, C.H.G.; Sola Veneziani, R.C.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Bastos, J.K. Occurrence, Chemical Composition, Biological Activities and Analytical Methods on Copaifera Genus—A Review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 109, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufatto, L.C.; Gower, A.; Schwambach, J.; Moura, S. Genus Mikania: Chemical Composition and Phytotherapeutical Activity. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 2012, 22, 1384–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.S.; Khongorzul, P.; Muyaba, M.; Alolga, R.N. Ent-Kaurane Diterpenoids from the Annonaceae Family: A Review of Research Progress and Call for Further Research. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, R.; García, P.A.; Castro, M.Á.; Del Corral, J.M.M.; Feliciano, A.S.; Oliveira, A.B. de Iso-Kaurenoic Acid from Wedelia Paludosa D.C. An Acad Bras Cienc 2010, 82, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Sim, S.S.; Whang, W.K.; Kim, C.J. Inhibitory Effects of Diterpene Acids from Root of Aralia Cordata on IgE-Mediated Asthma in Guinea Pigs. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2010, 23, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatino, A.; Salatino, M.L.F.; Negri, G. Traditional Uses, Chemistry and Pharmacology of Croton Species (Euphorbiaceae). J Braz Chem Soc 2007, 18, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalenogare, D.P.; Ferro, P.R.; De Prá, S.D.T.; Rigo, F.K.; de David Antoniazzi, C.T.; de Almeida, A.S.; Damiani, A.P.; Strapazzon, G.; de Oliveira Sardinha, T.T.; Galvani, N.C.; et al. Antinociceptive Activity of Copaifera Officinalis Jacq. L Oil and Kaurenoic Acid in Mice. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, K.; Hwang, S.; Lee, H.-J.; Jo, E.; Kim, J.N.; Cha, J. Identification of the Antibacterial Action Mechanism of Diterpenoids through Transcriptome Profiling. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, V.C.; Pereira, S.I.V.; Coppede, J.; Martins, J.S.; Rizo, W.F.; Beleboni, R.O.; Marins, M.; Pereira, P.S.; Pereira, A.M.S.; Fachin, A.L. The Epimer of Kaurenoic Acid from Croton Antisyphiliticus Is Cytotoxic toward B-16 and HeLa Tumor Cells through Apoptosis Induction. Genetics and Molecular Research 2013, 12, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotoras, M.; Folch, C.; Mendoza, L. Characterization of the Antifungal Activity on Botrytis Cinerea of the Natural Diterpenoids Kaurenoic Acid and 3β-Hydroxy-Kaurenoic Acid. J Agric Food Chem 2004, 52, 2821–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichnewski, W.; Sarti, S.J.; Gilbert, B.; Herz, W. Goyazensolide, a Schistosomicidal Heliangolide from Eremanthus Goyazensis. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, J. NMR Shift Data of Neo -clerodane Diterpenes from the Genus Ajuga. Phytochemical Analysis 2002, 13, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro Barros, M.C.; Sousa Lima, M.A.; Braz-Filho, R.; Rocha Silveira, E. 1 H and 13 C NMR Assignments of Abietane Diterpenes from Aegiphila Lhotzkyana. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 2003, 41, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.G.; Du, X.; Li, X.N.; Yan, B.C.; Zhou, M.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhan, R.; Dong, K.; Pu, J.X.; Sun, H.D. Four New Diterpenoids from Isodon Eriocalyx Var. Laxiflora. Nat Prod Bioprospect 2013, 3, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.B.; Saúde, D.A.; Perry, K.S.P.; Duarte, D.S.; Raslan, D.S.; Boaventura, M.A.D.; Chiari, E. Trypanocidal Sesquiterpenes FromLychnophora Species. Phytotherapy Research 1996, 10, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.M. do; Oliveira, D.C.R. de Kaurene Diterpenes and Other Chemical Constituents from Mikania Stipulacea (M. Vahl) Willd. J Braz Chem Soc 2001, 12, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, K.S.B.; Guedes, M.L.S.; Silveira, E.R. Abietane Diterpenes from Hyptis Crassifolia Mart. Ex Benth. (Lamiaceae). J Braz Chem Soc. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Shang, K.; Wang, J.; Xu, C.-S.; Cai, Z.; Yuan, P.; Wang, C.-G.; Gu, M.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Z.-X. Identification, Structural Revision and Biological Evaluation of the Phyllocladane-Type Diterpenoids from Callicarpa Longifolia Var. Floccosa. Tetrahedron 2024, 167, 134304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovatch, P.Y.; Ferreira, A.E.; Ghizonni, G.M.L.; Ambrósio, S.R.; Crotti, A.E.M.; Heleno, V.C.G. Detailed 1 H and 13 C NMR Structural Assignment of Ent -polyalthic Acid, a Biologically Active Labdane Diterpene. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry 2022, 60, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.E.; Rocha, A.C.F.S.; Bastos, J.K.; Heleno, V.C.G. Software-Assisted Methodology for Complete Assignment of 1H and 13C NMR Data of Poorly Functionalized Molecules: The Case of the Chemical Marker Diterpene Ent-copalic Acid. J Mol Struct 2021, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, M.G. LSO - NMR Webpage Available online:. Available online: http://artemis.ffclrp.usp.br/NMR.htm (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- ACD Labs ACD Spectrus Processor Available online:. Available online: https://www.acdlabs.com/products/spectrus-platform/spectrus-processor/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Kirk Marat SpinWorks Available online:. Available online: https://umanitoba.ca/science/research/chemistry/nmr (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Revvity Signals ChemDraw Trials Available online:. Available online: https://revvitysignals.com/trials (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Enriquez, R.G.; Barajas, J.; Ortiz, B.; Lough, A.J.; Reynolds, W.F.; Yu, M.; Leon, I.; Gnecco, D. Comparison of Crystal and Solution Structures and 1 H and 13 C Chemical Shifts for Grandiflorenic Acid, Kaurenoic Acid, and Monoginoic Acid. Can J Chem 1997, 75, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Available online: https://www.stenutz.eu/conf/haasnoot.php (accessed on 17 January 2025).

| C |

H |

CDCl3 δH(ppm) |

CD3OD δH(ppm) |

C6D6 δH(ppm) |

C5D5N δH(ppm) |

Coupling constants (Hz) | Mult. |

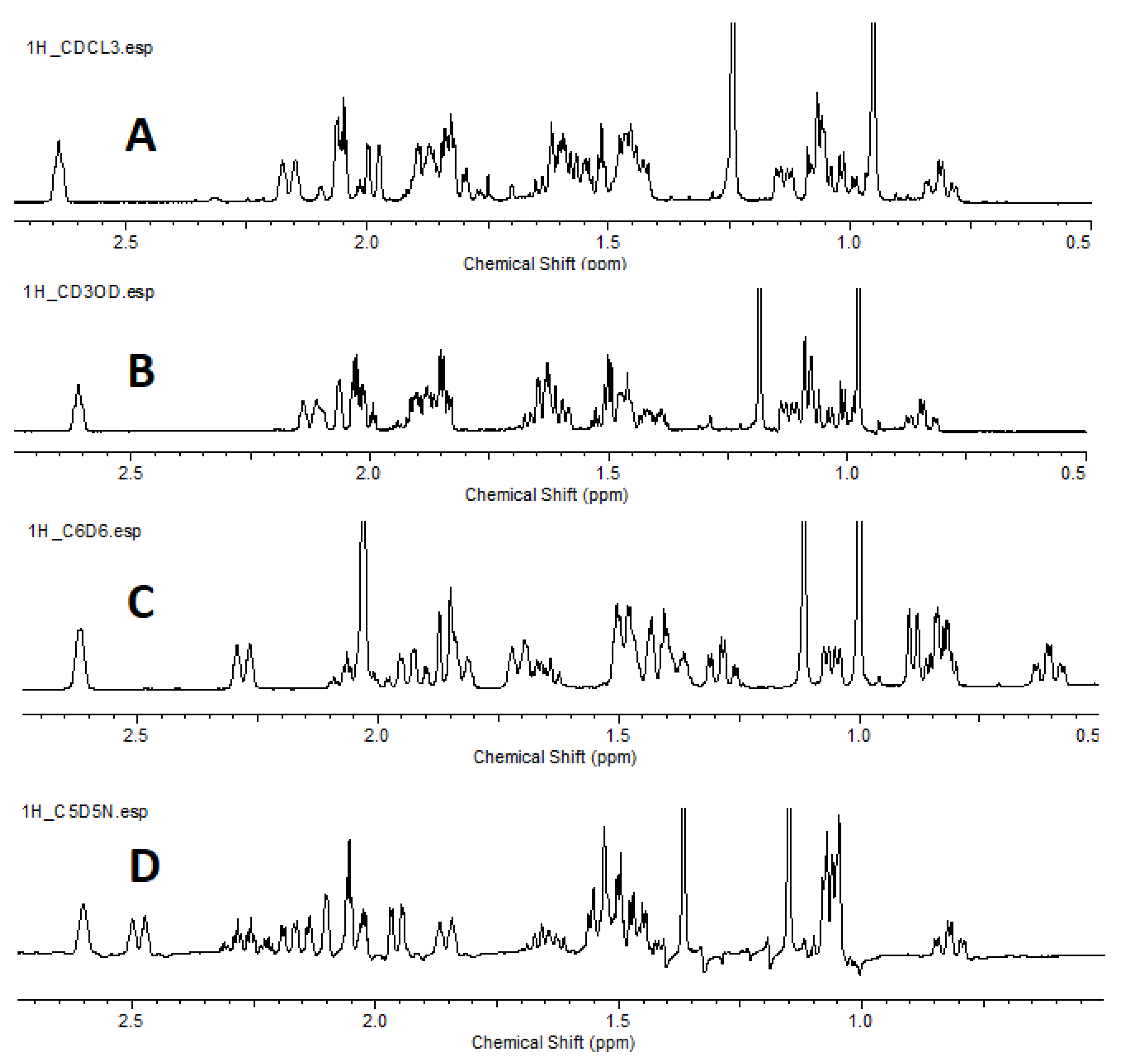

| 1 | 1α | 1.88(1H) | 1.89(1H) | 1.71(1H) | 1.85(1H) | J(1α,1β)=13.3;J(1α,2α)=3.9;J(1α,2β)=2.9; J(1α,3α)=1.8 | dddd |

| 1β | 0.81(1H) | 0.84(1H) | 0.60(1H) | 0.82(1H) | J(1β,1α)=13.3;J(1β,2α)=13.3; J(1β,2β)=4.0 | td | |

| 2 | 2α | 1.84(1H) | 1.93(1H) | 2.05(1H) | 2.27(1H) | J(2α,2β)=13.8;J(2α,1β)=13.3; J(2α,3β)=13.2;J(2α,1α)=3.9; J(2α,3α)=3.7 | ddddd |

| 2β | 1.44(1H) | 1.46(1H) | 1.38(1H) | 1.52(1H) | J(2β,2α)=13.8;J(2β,3β)=4.4; J(2β,1β)=4.0;J(2β,1α)=2.9; J(2β,3α)=2.9 | dddt | |

| 3 | 3α | 2.16(1H) | 2.13(1H) | 2.28(1H) | 2.48(1H) | J(3α,3β)=13.4;J(3α,2α)=3.7;J(3α,2β)=2.9; J(3α,1α)=1.8 | dddd |

| 3β | 1.01(1H) | 1.01(1H) | 0.83(1H) | 1.08(1H) | J(3β,3α)=13.4;J(3β,2α)=13.2; J(3β,2β)=4.4 | ddd | |

| 4 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 5 | 5β | 1.06(1H) | 1.07(1H) | 0.83 (1H) | 1.06(1H) | J(5β,6α)=12.3; J(5β,6β)=2.2 | dd |

| 6 | 6α | 1.81(1H) | 1.85(1H) | 1.94 (1H) | 2.18(1H) | J(6α,6β)=13.8;J(6α,7β)=12.9;J(6α,5β)=12.3; J(6α,7α)=3.1 | dddd |

| 6β | 1.83(1H) | 1.89(1H) | 1.83 (1H) | 2.04(1H) | J(6β,6α)=13.8;J(6β,7β)=3.7;J(6β,7α)=3.1; J(6β,5β)=2.2 | dddd | |

| 7 | 7α | 1.51(1H) | 1.52(1H) | 1.42(1H) | 1.52(1H) | J(7α,7β)=13.1;J(7α,6α)=3.1;J(7α,6β)=3.1 | dt |

| 7β | 1.44(1H) | 1.46(1H) | 1.28(1H) | 1.45(1H) | J(7β,7α)=13.1;J(7β,6α)=12.9;J(7β,6β)=3.7 | ddd | |

| 8 | --- | --- | --- | --- | |||

| 9 | 9β | 1.07(1H) | 1,08(1H) | 0.89(1H) | 1.05(1H) | J(9β,11α)=8.7;J(9β,11β)=1.6;J(9β,14α)=1.4 | ddd |

| 10 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 11 | 11α | 1.58(1H) | 1.62(1H) | 1.66(1H) | 1.65(1H) |

J(11α,11β)=13.5;J(11α;12α)=9.5; J(11α;12β)=8.7;J(11α;9β)=8.7 |

ddt |

| 11β | 1.46(1H) | 1.42(1H) | 1.45(1H) | 1.54(1H) | J(11β,11α)=13.5;J(11β,12β)=3.4; J(11β,12α)=2.6;J(11β,9β)=1.6 | dddd | |

| 12 | 12α | 1.60(1H) | 1.64(1H) | 1.50(1H) | 1.53(1H) |

J(12α,12β)=14.3; J(12α,11α)=9.5; J(12α,11β)=2.6;J(12α,13)=1.9 |

dddd |

| 12β | 1.47(1H) | 1.62(1H) | 1.47(1H) | 1.49(1H) | J(12β,12α)=14.3;J(12β,11α)=8.7; J(12β,11β)=3.4;J(12β,13α)=4.4;J(12β,14α)= 1.7 | ddddd | |

| 13 | 13α | 2.64(1H) | 2.61(1H) | 2.62(1H) | 2.60(1H) | J(13α,14α)=5.0;J(13α,12β)=4.4; J(13α,12α)=1.9;J(13α,17a)=0.9; J(13α,17b)=0.9 | dddt |

| 14 | 14β | 1.99(1H) | 2.01(1H) | 1.86(1H) | 1.96(1H) | J(14β,14α)=11.4; J(14β,15β)=1.9 | dd |

| 14α | 1.14(1H) | 1.12(1H) | 1.06(1H) | 1.06(1H) | J(14α,14β)=11.4;J(14α,13α)=5.0; J(14α,12β)= 1.7; J(14α, 9β)=1.4 | dddd | |

| 15 | 15β | 2.08(1H) | 2.08(1H) | 2.03(1H) | 2.12(1H) | J(15β,15α)=16.8;J(15β,17a)=2.2; J(15β,17b)2.2; J(15β,14β)=1.9 | dtd |

| 15α | 2.03(1H) | 2.05(1H) | 2.03(1H) | 2.04(1H) | J(15α,15β)=16.8;J(15α,17a)=2.6; J(15α,17b)=2.6 | dt | |

| 16 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 17 | 17a | 4.80(1H) | 4.78(1H) | 4.97(1H) | 4.92(1H) | J(17a,15α)=2.6;J(17a,15β)=2.2; J(17a,17b)=1.5; J(17a,13α)=0.9 | dddd |

| 17b | 4.74(1H) | 4.72(1H) | 4.93(1H) | 4.88(1H) | J(17b,15α)=2.6;J(17b,15β)=2.2; J(17b,17a)=1.5; J(17b,13α)=0.9 | dddd | |

| 18 | 18β | 1.24(3H) | 1.18(3H) | 1.11(3H) | 1.36(3H) | s | |

| 19 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| 20 | 20α | 0.95(3H) | 0.98(3H) | 1.00(3H) | 1.15(3H) |

s |

| C | CDCl3 δC(ppm) |

CD3OD δC(ppm) |

C6D6 δC(ppm) |

C5D5N δC(ppm) |

| 1 | 40.7 | 42.2 | 40.8 | 41.1 |

| 2 | 19.1 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 19.9 |

| 3 | 37.8 | 39.4 | 38.0 | 38.7 |

| 4 | 43.8 | 44.8 | 44.4 | 44.0 |

| 5 | 57.1 | 58.4 | 57.1 | 57.1 |

| 6 | 21.9 | 23.3 | 22.2 | 22.6 |

| 7 | 41.3 | 42.7 | 41.5 | 41.7 |

| 8 | 44.3 | 45.6 | 44.1 | 44.5 |

| 9 | 55.2 | 56.7 | 55.3 | 55.3 |

| 10 | 39.7 | 41.0 | 39.9 | 40.0 |

| 11 | 18.4 | 19.6 | 18,7 | 18.7 |

| 12 | 33.1 | 34.4 | 33.4 | 33.4 |

| 13 | 43.9 | 45.4 | 44.3 | 44.2 |

| 14 | 39.7 | 40.9 | 39.9 | 39.9 |

| 15 | 49.0 | 50.3 | 49.4 | 49.3 |

| 16 | 155.9 | 157.0 | 155.7 | 156.0 |

| 17 | 103.0 | 103.8 | 103.6 | 103.5 |

| 18 | 29.0 | 29.7 | 29.0 | 29.4 |

| 19 | 184.1 | 181.9 | 185.1 | 180.1 |

| 20 | 15.6 | 16.5 | 16.0 | 16.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).