Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

Data Source

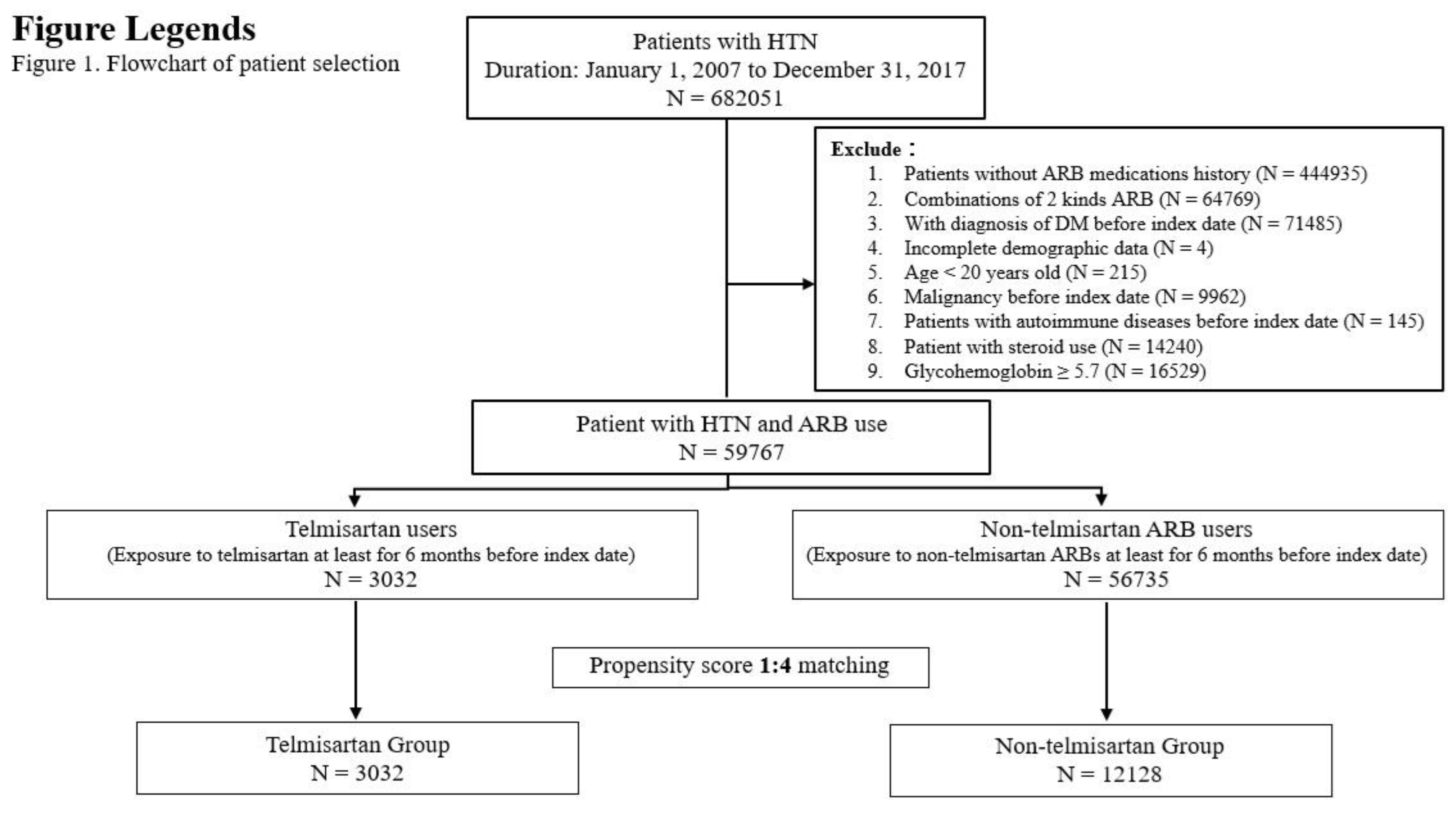

Patient Selection and Study Design

Covariates and Study Outcomes

Outcome Measurement

Statistical Analysis

Results

Subject Characteristics

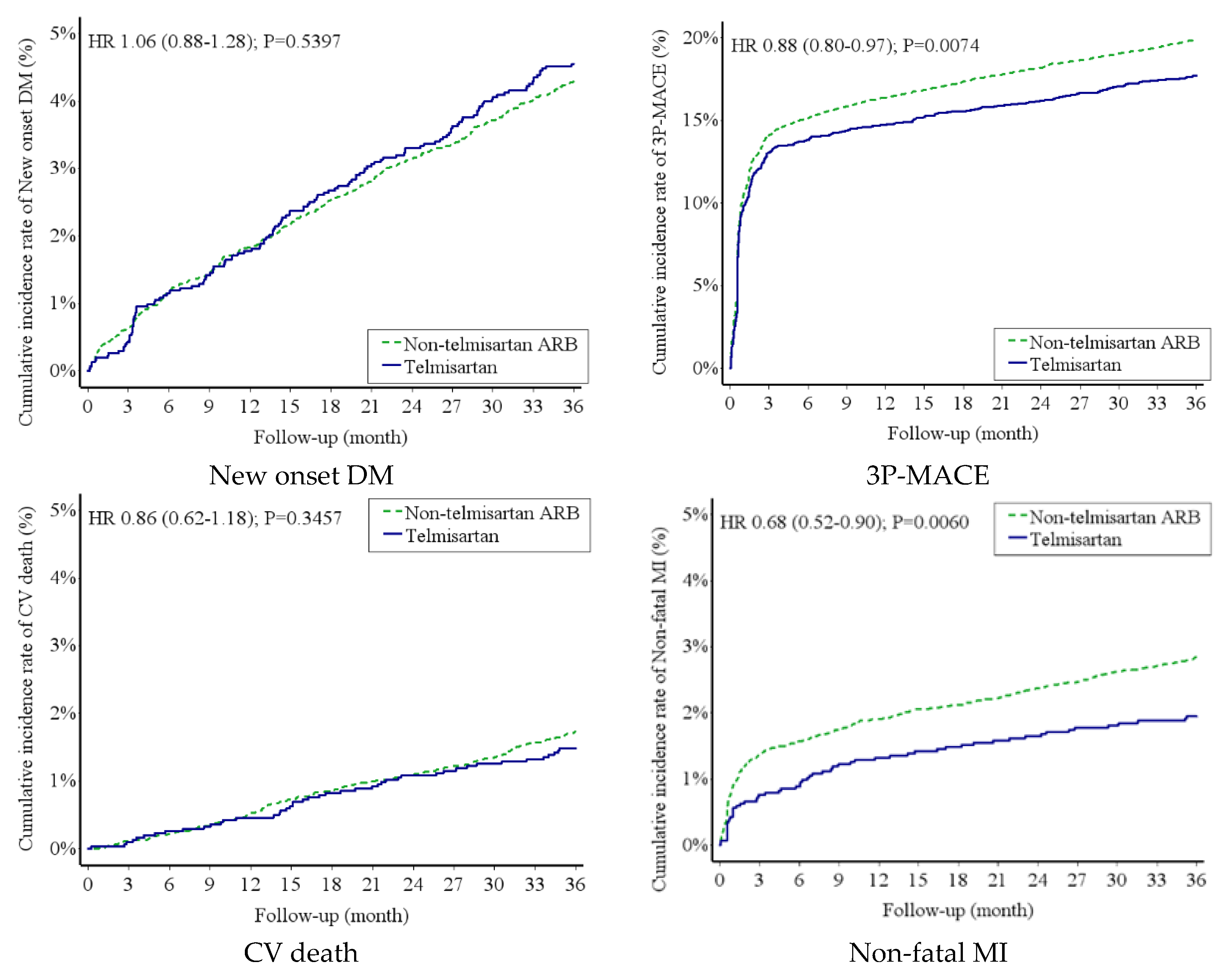

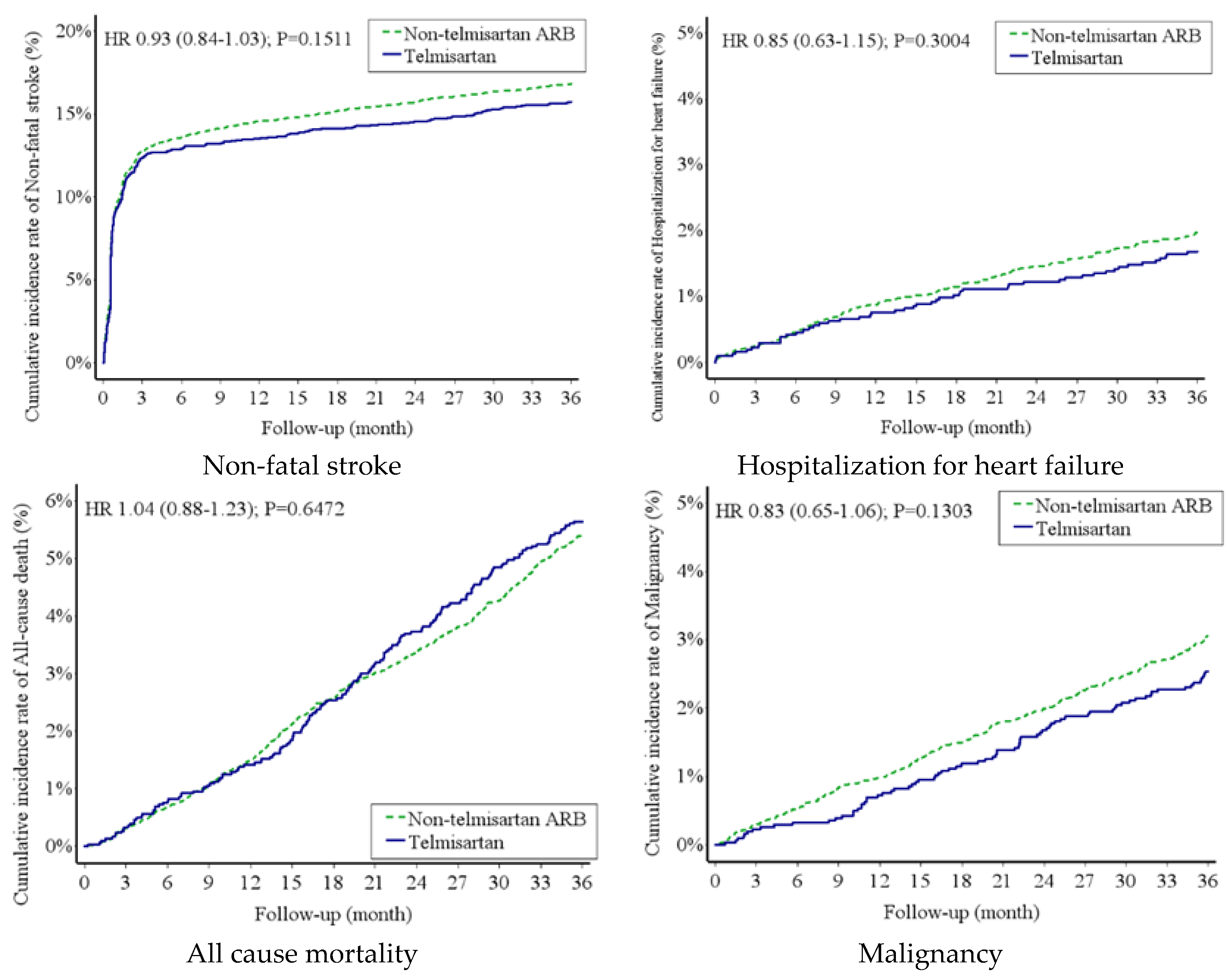

Risk of New-Onset DM and MACE Between Telmisartan Group and Non-Telmisartan ARB Group

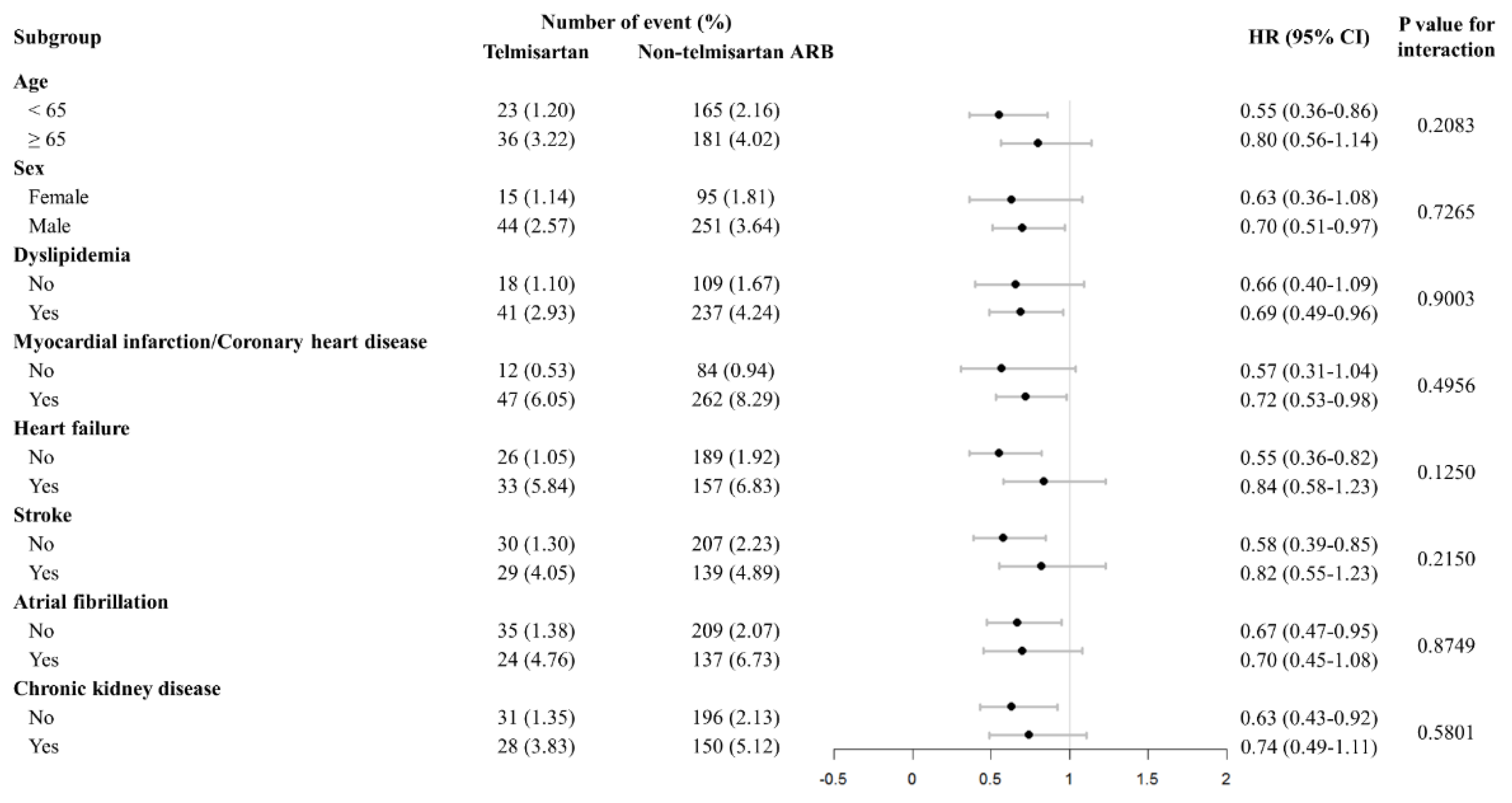

Subgroup Analysis

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, e127–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, B.M.; Cooper, M.E.; De Zeeuw, D.; Keane, W.F.; Mitch, W.E.; Parving, H.-H.; Remuzzi, G.; Snapinn, S.M.; Zhang, Z.; Shahinfar, S. Effects of Losartan on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, E.J.; Hunsicker, L.G.; Clarke, W.R.; Berl, T.; Pohl, M.A.; Lewis, J.B.; Ritz, E.; Atkins, R.C.; Rohde, R.; Raz, I.; et al. Renoprotective Effect of the Angiotensin-Receptor Antagonist Irbesartan in Patients with Nephropathy Due to Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragonesi, P.D. Effects of angiotensin II receptor blockers on insulin resistance. Hypertens. Res. 2010, 33, 778–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.L.; Pan, Y.; Jin, H.M. Adiponectin is positively associated with insulin resistance in subjects with type 2 diabetic nephropathy and effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker losartan. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamana, A.; Arita, M.; Furuta, M.; Shimajiri, Y.; Sanke, T. The angiotensin II receptor blocker telmisartan improves insulin resistance and has beneficial effects in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes and poor glycemic control. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2008, 82, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinoi, T.; Tomohiro, Y.; Kajiwara, S.; Matsuo, S.; Fujimoto, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Shichijo, T.; Ono, T. Telmisartan, an Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Blocker, Improves Coronary Microcirculation and Insulin Resistance among Essential Hypertensive Patients without Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Hypertens. Res. 2008, 31, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, T.W.; Pravenec, M. Antidiabetic mechanisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists: beyond the renin-angiotensin system. J. Hypertens. 2004, 22, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, F.; Oron, Y.; Limor, R.; Stern, N.; Rosenthal, T. Prophylactic treatment with telmisartan induces tissue-specific gene modulation favoring normal glucose homeostasis in Cohen-Rosenthal diabetic hypertensive rats. Metabolism 2012, 61, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-Q.; Luo, R.; Li, L.-Y.; Tian, F.-S.; Zheng, X.-L.; Xiong, H.-L.; Sun, L.-T. Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker Telmisartan Prevents New-Onset Diabetes in Pre-Diabetes OLETF Rats on a High-Fat Diet: Evidence of Anti-Diabetes Action. Can. J. Diabetes 2013, 37, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Niwa, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Goto, S.-N.; Umemoto, T. Telmisartan as a metabolic sartan: The first meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in metabolic syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2013, 7, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suksomboon, N.; Poolsup, N.; Prasit, T. Systematic review of the effect of telmisartan on insulin sensitivity in hypertensive patients with insulin resistance or diabetes. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2011, 37, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Han, D.-W.; Rong, X.-R.; Wang, Y.-X.; Xue, J.-J.; Yang, J. Telmisartan Improves Insulin Resistance: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Ther. 2018, 25, e642–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, W.B.; Lacourciere, Y.; Davidai, G. Effects of the angiotensin II receptor blockers telmisartan versus valsartan on the circadian variation of blood pressure impact on the early morning period. Am. J. Hypertens. 2004, 17, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The ONTARGET Investigators Telmisartan, Ramipril, or Both in Patients at High Risk for Vascular Events. New Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1547–1559. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Teo, K.; Anderson, C.S.; Pogue, J.; Dyal, L.; Copland, I.; Schumacher, H.; Dagenais, G.; Sleight, P.; The Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Chan, Y.; Yang, Y.K.; Lin, S.; Hung, M.; Chien, R.; Lai, C.; Lai, E.C. The Chang Gung Research Database—A multi-institutional electronic medical records database for real-world epidemiological studies in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2019, 28, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-S.; Lai, M.-S.; Gau, S.S.-F.; Wang, S.-C.; Tsai, H.-J. Concordance between Patient Self-Reports and Claims Data on Clinical Diagnoses, Medication Use, and Health System Utilization in Taiwan. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e112257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Lai, M.-L. Validating the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke in a National Health Insurance claims database. J. Formos. Med Assoc. 2015, 114, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Ross, C.; Raebel, M.A.; Shetterly, S.; Blanchette, C.; Smith, D. Use of Stabilized Inverse Propensity Scores as Weights to Directly Estimate Relative Risk and Its Confidence Intervals. Value Heal. 2010, 13, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, B.; Akioyamen, L.E.; Bonner, A.; Frankfurter, C.; Levine, M.; Pullenayegum, E.; Goeree, R.; O’reilly, D. Comparative Efficacy of Angiotensin II Antagonists in Essential Hypertension: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Hear. Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Kang, J.; Park, J.; Seo, W.; Lee, S.; Lim, W.; Jeon, K.; Hwang, I.; Kim, H. Long-term mortality and cardiovascular events of seven angiotensin receptor blockers in hypertensive patients: Analysis of a national real-world database: A retrospective cohort study. Heal. Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.-G.M.; Lim, M.-J.M.; Kim, J.-S.; Jeong, H.-E.; Ko, H.B.; Shin, J.-Y. Risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and cerebrovascular disease with the use of valsartan, losartan, irbesartan, and telmisartan in patients. Medicine 2023, 102, e36098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, H.M.A.; White, C.M.; White, W.B. The Comparative Efficacy and Safety of the Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in the Management of Hypertension and Other Cardiovascular Diseases. Drug Saf. 2014, 38, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, S.C.; Pershadsingh, H.A.; Ho, C.I.; Chittiboyina, A.; Desai, P.; Pravenec, M.; Qi, N.; Wang, J.; Avery, M.A.; Kurtz, T.W. Identification of Telmisartan as a Unique Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist With Selective PPARγ–Modulating Activity. Hypertension 2004, 43, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, M.; Janke, J.; Clasen, R.; Unger, T.; Kintscher, U. Angiotensin Type 1 Receptor Blockers Induce Peroxisome Proliferator–Activated Receptor-γ Activity. Circulation 2004, 109, 2054–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S.; Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W. Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature 2000, 405, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; et al. PPAR-γ agonist pioglitazone regulates dendritic cells immunogenicity mediated by DC-SIGN via the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. International immunopharmacology 41, 24-34 (2016).

- Hamblin, M.; Chang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.E. PPARs and the Cardiovascular System. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 1415–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikejima, H.; Imanishi, T.; Tsujioka, H.; Kuroi, A.; Kobayashi, K.; Shiomi, M.; Muragaki, Y.; Mochizuki, S.; Goto, M.; Yoshida, K.; et al. Effects of telmisartan, a unique angiotensin receptor blocker with selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ-modulating activity, on nitric oxide bioavailability and atherosclerotic change. J. Hypertens. 2008, 26, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.-C.; Li, X.-S.; Wen, H. Telmisartan protects against microvascular dysfunction during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.-F.; Jin, D.-M.; Wu, W.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.-F. Angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of new-onset type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of 59,862 patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 155, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Wu, L.-C.; Lin, J.-W.; Chuang, L.-M.; Lai, M.-S. Different angiotensin receptor blockers and incidence of diabetes: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 91–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Before | After Propensity Score Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telmisartan | Non-telmisartan ARB | P-value a | Telmisartan | Non-telmisartan ARB | P-value a | |

| (N = 3032) | (N = 56735) | (N = 3032) | (N = 12128) | |||

| Age, yearsb | 59.90 ± 14.14 | 62.29 ± 14.31 | <0.0001* | 59.90 ± 14.14 | 59.96 ± 14.27 | 0.8344 |

| Age group | <0.0001* | 0.7554 | ||||

| ˂65 years old | 1913 (63.09) | 31349 (55.26) | 1913 (63.09) | 7631 (62.92) | ||

| 65-74 years old | 573 (18.90) | 12342 (21.75) | 573 (18.90) | 2248 (18.54) | ||

| ≥75 years old | 546 (18.01) | 13044 (22.99) | 546 (18.01) | 2249 (18.54) | ||

| Sex (Male) | 1714 (56.53) | 32045 (56.48) | 0.9582 | 1714 (56.53) | 6888 (56.79) | 0.7931 |

| Follow up duration (years) | 5.92 ± 4.43 | 5.42 ± 4.62 | <0.0001* | 5.92 ± 4.43 | 5.89 ± 4.60 | 0.7580 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Dyslipidemia | 1400 (46.17) | 26296 (46.35) | 0.8509 | 1400 (46.17) | 5594 (46.12) | 0.9610 |

| Coronary artery disease | 777 (25.63) | 16769 (29.56) | <0.0001* | 777 (25.63) | 3162 (26.07) | 0.6170 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 504 (16.62) | 11824 (20.84) | <0.0001* | 504 (16.62) | 2037 (16.80) | 0.8194 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 483 (15.93) | 10882 (19.18) | <0.0001* | 483 (15.93) | 1940 (16.00) | 0.9294 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 732 (24.14) | 15444 (27.22) | 0.0002* | 732 (24.14) | 2929 (24.15) | 0.9924 |

| Venous thromboembolism (DVT/PE) | 449 (14.81) | 9961 (17.56) | 0.0001* | 449 (14.81) | 1822 (15.02) | 0.7673 |

| Gout | 672 (22.16) | 14214 (25.05) | 0.0003* | 672 (22.16) | 2716 (22.39) | 0.7849 |

| HBV | 441 (14.54) | 9904 (17.46) | <0.0001* | 441 (14.54) | 1787 (14.73) | 0.7919 |

| HCV | 441 (14.54) | 9942 (17.52) | <0.0001* | 441 (14.54) | 1781 (14.69) | 0.8452 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 449 (14.81) | 10091 (17.79) | <0.0001* | 449 (14.81) | 1821 (15.01) | 0.7760 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 544 (17.94) | 12536 (22.10) | <0.0001* | 544 (17.94) | 2173 (17.92) | 0.9747 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 440 (14.51) | 9841 (17.35) | <0.0001* | 440 (14.51) | 1781 (14.69) | 0.8094 |

| Dementia | 451 (14.87) | 9966 (17.57) | 0.0001* | 451 (14.87) | 1820 (15.01) | 0.8555 |

| Myocardial infarction | 456 (15.04) | 10455 (18.43) | <0.0001* | 456 (15.04) | 1837 (15.15) | 0.8829 |

| Heart failure | 565 (18.63) | 12527 (22.08) | <0.0001* | 565 (18.63) | 2298 (18.95) | 0.6934 |

| Stroke | 716 (23.61) | 16574 (29.21) | <0.0001* | 716 (23.61) | 2844 (23.45) | 0.8481 |

| Drug | ||||||

| Aspirin | 257 (8.48) | 5044 (8.89) | 0.4344 | 257 (8.48) | 1037 (8.55) | 0.8959 |

| Clopidogrel | 24 (0.79) | 600 (1.06) | 0.1603 | 24 (0.79) | 84 (0.69) | 0.5623 |

| Fibrate | 62 (2.04) | 1250 (2.20) | 0.5620 | 62 (2.04) | 250 (2.06) | 0.9544 |

| Statin | 635 (20.94) | 11855 (20.90) | 0.9496 | 635 (20.94) | 2470 (20.37) | 0.4812 |

| Beta-blockers | 773 (25.49) | 13974 (24.63) | 0.2821 | 773 (25.49) | 3095 (25.52) | 0.9777 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 1621 (53.46) | 27200 (47.94) | <0.0001* | 1621 (53.46) | 6416 (52.90) | 0.5801 |

| Diuretic(Thiazide) | 621 (20.48) | 14937 (26.33) | <0.0001* | 621 (20.48) | 2444 (20.15) | 0.6859 |

| Diuretic(Loop) | 144 (4.75) | 3989 (7.03) | <0.0001* | 144 (4.75) | 570 (4.70) | 0.9084 |

| Diuretic(K sparing) | 13 (0.43) | 888 (1.57) | <0.0001* | 13 (0.43) | 52 (0.43) | 1.0000 |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 13.43 ± 2.14 | 13.26 ± 2.06 | 0.0049* | 13.52 ± 2.01 | 13.50 ± 2.02 | 0.6477 |

| Creatinine | 1.24 ± 1.47 | 1.22 ± 1.32 | 0.5070 | 1.26 ± 1.44 | 1.27 ± 1.46 | 0.7738 |

| LDL | 115.15 ± 32.78 | 111.67 ± 32.00 | <0.0001* | 114.42 ± 32.23 | 114.10 ± 32.12 | 0.6225 |

| Cholesterol | 190.52 ± 35.27 | 186.71 ± 35.08 | <0.0001* | 189.77 ± 35.20 | 189.36 ± 35.10 | 0.5616 |

| Triglyceride | 139.98 ± 76.19 | 135.99 ± 76.74 | 0.0226* | 138.42 ± 76.50 | 138.54 ± 78.32 | 0.9418 |

| Sugar | 101.21 ± 16.42 | 103.10 ± 20.18 | <0.0001* | 102.29 ± 17.95 | 102.42 ± 19.53 | 0.7241 |

| Glycohemoglobin | 5.38 ± 0.24 | 5.40 ± 0.22 | 0.2704 | 5.40 ± 0.22 | 5.40 ± 0.22 | 0.8625 |

| Number of events (events/100 person-year) | aHR (95% CI)a | P-valuea | aHR (95% CI)b | P-valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telmisartan | Non-telmisartan ARB | |||||

| New onset DM | 138 (1.56) | 521 (1.47) | 1.06 (0.88-1.28) | 0.5397 | 1.06 (0.88-1.28) | 0.5395 |

| 3P-MACE | 537 (6.96) | 2414 (7.98) | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) | 0.0074* | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) | 0.0073* |

| CV death | 45 (0.50) | 210 (0.58) | 0.86 (0.62-1.18) | 0.3457 | 0.86 (0.62-1.18) | 0.3458 |

| Non-fatal MI (AMI+PCI+CABG+TT) | 59 (0.66) | 346 (0.97) | 0.68 (0.52-0.90) | 0.0060* | 0.68 (0.52-0.90) | 0.0059* |

| Non-fatal stroke | 477 (6.08) | 2041 (6.58) | 0.93 (0.84-1.03) | 0.1511 | 0.93 (0.84-1.03) | 0.1499 |

| All-cause mortality | 171 (1.93) | 659 (1.86) | 1.04 (0.88-1.23) | 0.6472 | - | - |

| Hospitalization for heart failure | 51 (0.57) | 239 (0.66) | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | 0.3004 | 0.85 (0.63-1.15) | 0.3004 |

| Malignancy | 77 (0.86) | 371 (1.04) | 0.83 (0.65-1.06) | 0.1303 | 0.83 (0.65-1.06) | 0.1301 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).