The digitalization of administrative processes has emerged as a crucial component of the transformation of public institutions. This shift, driven by conceptual frameworks rooted in the Post-New Public Management paradigm (Osborne, 2006) and further catalyzed by the pandemic, was implemented not only to enhance administrative efficiency but also to bolster public health governance (Bertoli & Blatrix, 2015).

A review of doctoral research from the past three decades underscores the significance of digitalization as a central theme in public management (Dupuis, 2020). McIlvenny et al. (2016) have demonstrated how a novel form of governmentality has gradually taken shape through the implementation of e-government, thereby reshaping the institutional power dynamics. In this context, Grave (2013) argues that both the tools and the methodologies for controlling economic resources and actors have become standardized, now embedded within the daily management of urban governance. Supiot (2015), in his critique of “governance by numbers,” highlights the prevailing emphasis on efficiency, which often obscures the qualitative aspects of public reform evaluations (Le Goff, 2015). The evaluation of public performance, as a result, is increasingly called into question, with a growing focus on the value of co-designed and co-constructed transformations (Matyjasik & Guenoun, 2020).

Despite its critical importance, Bezes (2007) identifies a significant gap in the literature, referring to the “blind spot” of Weberian administration during the era of New Public Management, which remains insufficiently explored in scientific research (2007, p. 5). In a similar vein, Goter and Khenniche (2022) highlight the paradoxical nature of public performance evaluation methods, advocating for a rethinking of stakeholder integration within collaborative frameworks of public action. Echoing this perspective, Moore and Khagram (2004) conceptualize the public manager as an “entrepreneur” of performance, whose actions produce immediate and tangible impacts (Matyjasik & Guenoun, 2020).

This research contributes a critical perspective to the study of administrative reform in a developing country undergoing democratic transition—specifically, Tunisia—by drawing on value creation theory. More precisely, we examine the case of Tunisia’s participation in the “Open Government Partnership” (OGP), a pivotal reform initiative that aims to facilitate the implementation of public sector reforms (OECD, 2020). The OGP’s mission is to secure concrete commitments from governments to promote transparency, empower citizens, combat corruption, and harness technological innovations to strengthen governance (Clarke & Francoli, 2014). In the wake of the fall of the Ben Ali regime and the onset of democratic governance, the reform of Tunisia’s public institutions has been subject to intense scrutiny, particularly as civil society began to challenge the legitimacy of public actors and their decisions.

As Tunisia’s civil society increasingly demands greater transparency through the digitalization of public administration, it has emerged as a pivotal stakeholder in both the democratic transition and the reform of public governance. In this context, the digitization of administrative processes is viewed not only as an opportunity for reform but also as a means to foster broader organizational transformations focused on “coordination, interoperability, efficiency, and effectiveness” (Mergel, 2020, p. 7). However, the rise of new “interest groups” has also provoked resistance from entrenched actors, long accustomed to exclusive decision-making power. Moreover, the change in regime has prompted new political actors to seek control over administrative processes, aiming to capitalize on the opportunities presented by democratization.

In this regard, Moore’s strategic framework (1995) offers a useful synthesis of the policy implementation process, highlighting three key elements: the legitimacy of political decisions, their operationalization, and the pursuit of public value creation (Moore & Khagram, 2004). With Moore, the public manager is repositioned as both a leader and facilitator of public policy co-construction, transcending the limitations of purely quantitative evaluations.

Our research examines the conditions necessary for the emergence of a value-driven, citizen-led form of governance capable of influencing the direction of the Open Government Partnership within the Tunisian public administration.

This study aims to explore the processes involved in the co-construction of a public policy focused on transparency and open government. This co-construction process entails collaboration among the public administration, civil society, and foreign “technical and financial partners” (TFPs). Beyond examining the practical aspects of implementing such co-construction, the study will specifically focus on the following key areas:

- -

The evolution of this co-construction process and its adaptation to the political and institutional changes characteristic of the “democratic transition” period;

- -

The tensions between the need for flexibility and contextual adaptation of the open government policy to the Tunisian environment, and the standardized “one best way” approach often advocated by TFPs;

- -

The conflicts of legitimacy and leadership arising between a civil society that is increasingly expert and committed, eager to access international funding, and an administration that, paradoxically, progresses hesitantly and in a fragmented manner.

This research will develop three core propositions. The first proposition asserts that transparency, accountability, and citizen participation are fundamental components in the co-creation of public reforms.

The second proposition contends that both citizens and administrative leadership are influenced by the reform framework, as well as the underlying interests and values that drive the adoption of the co-construction model of public policy in Tunisia.

The third proposition suggests that institutional mimicry, alongside the expectations of technical and financial partners and other external stakeholders, ultimately undermines both the co-construction process and the sovereignty of public policy.

To analyze these dynamics, we draw on the theory of public value (Moore, 1995), which helps illuminate the logics driving actors’ actions and the interrelationship of roles within the context of an evolving bureaucratic experience.

Our approach will be grounded in collaborative action research conducted in partnership with the e-government unit, which was responsible for implementing the OGP Tunisia program. We will critically analyze the discourses and underlying logics that shape this form of public “innovation,” within the broader context of the “co-creation” of public policies (Pestoff et al., 2006).

1. Contributions of Public Value Creation Theory to the Analysis of Public Service Reform

The evolution of management sciences in the early twentieth century, alongside the rationalization of Weberian administration, introduced the concepts of “control,” “planning,” and “scientific” organization. However, these innovations failed to produce a single, unified definition of managerial reform (Armandy & Rival, 2021; Osborne, 2006, p. 3777; Hudon & Mazouz, 2014). These sciences have traditionally maintained a distinction between administration and politics. From the perspectives of Wilson (1887) and Goodnow (1900) (cited by Agulhon & Mueller, 2022), politics is defined by its role in managing “the expression of politics,” while public administration is seen as ”the execution of the will of politics” (Pesqueux, 2020).

In more recent scholarship, Hibou (2020) observes that “rationalization has been supplanted by a desire for calculability and predictability, a quest for neutrality, objectivity, and impersonality.” She argues that Weberian administration endures, even beyond the “semantic” innovations associated with New Public Management (NPM). Similarly, Lorino (1999) frames the legitimacy of public administration performance and management in terms of the “need” and “cost” of services as perceived by beneficiaries, including “users,” “citizens,” and “customers.”

For much of history, the state has conceptualized and assessed the utility of its actions from a position of self-regulation, simultaneously acting as both judge and party in evaluating public performance. It is only in more recent times that the modernization of the administration has been accompanied by the introduction of accountability measures for both “politicians” and “civil servants,” particularly through frameworks such as “public service quality management” (Bouckaert, 2003).

The digitization and digital transformation of public administration not only reflect evolving societal perceptions of the State’s role but, more importantly, offer a significant opportunity to foster new organizational paradigms that contribute to the emergence of Digital Era Governance (Mergel, 2020). This transformation, however, does not enjoy universal agreement. Managerial perspectives on “New Public Management” often interpret it as a manifestation of a broader ideological shift. In this context, Burlaud et al. (2019) critically examine the fragmentation of sovereignty resulting from institutional reforms that, in their view, further erode the state’s role and engagement (2019, p. 349). The challenges amplified by two years of pandemic-induced disruption have prompted a reevaluation of public service efficiency and managerial innovation, encouraging more dynamic approaches to state intervention and facilitating new managerial interpretations that extend beyond the confines of “New Public Management” (Matyjasik & Guenoun, 2020).

Bouckaert (2003) contends that the legitimacy of public policies is undermined when the state undertakes reforms in a simplistic, one-dimensional manner. Hirschman’s (1970) framework of “Loyalty, Voice, and Exit” offers a useful lens for understanding this dynamic: “loyalty” represents the commitment of supporters, “voice” encompasses the expressions of beneficiaries, hesitant allies, disillusioned critics, and passionate adversaries, while “exit” reflects the choices of those who feel marginalized or excluded (2003, p. 44). In this context, the establishment of a “voice” channel, through which the state can both guide reform and address civil society’s demands, has increasingly gained legitimacy. This approach is being realized through the co-creation of public policies and enhanced citizen participation. Building on and expanding this notion, Moore (2015) asserts that the public manager must assume the role of an entrepreneur, where value creation involves actively engaging all stakeholders to contribute to the development of public services, thus shaping the collective understanding of their effectiveness and relevance.

Emphasizing a single governance instrument—whether “transparency,” “co-construction,” or “anti-corruption”—does not necessarily produce the same outcomes, even though these concepts are integral to the foundational principles of “good governance” (Osborne, 2006). The balancing act between these core principles is described as “the main role of reformers” (Osborne, 2006, p. 10). The discretionary power to prioritize one governance mechanism over another represents a form of governmental “freedom,” which inevitably raises questions about the “arbitrariness” of public policy decisions made in the name of “the common good” (Hudon & Mazouz, 2014).

2. The Interplay of Stakeholder Roles in the Co-Creation of Public Policy

Mergel (2020) recently highlights that, as part of the strategy for the digital transformation of public administration, the establishment of a dedicated digital department represents a third approach that mediates between traditional service delivery and modern information systems. Advancing this “third way” requires a comprehensive examination of the processes involved in implementing managerial innovations centered on “co-creation” (Rival & Bordalan, 2017, p. 8). Within this context, quality management becomes a foundational element in integrating the “voice” of “citizen-customers,” while the public manager, envisioned as an entrepreneur of public value, serves to “instrumentalize” the values introduced by citizen leadership, which is recognized for its expertise and in-depth understanding of the field (Moore, 2015). However, this process of co-constructing public policies may give rise to conflicts over the “legitimacy” or “values” of the various actors involved in public action.

For Féral (2022), conflict situations depend on the assessments that actors make based on the values they defend and through which they operate their reading grid of the co-construction of public action or policy. This primacy of values in the definition and resolution of conflicts, and in the co-construction of public policies, must not lead to a static conception of the latter. Indeed, the “conscientization” of public values is a necessary phase in the recognition of the values of citizens involved in the co-construction of public policies. Proceeding in stages and in a dynamic way, the prioritization of values and the readings proposed by citizens are of paramount importance in order to understand the real motivations of engaged citizens and the role of citizen leadership in the value-creation process.

In the following sections, we will try to build on this conception of values and public value defended by Moore to implement collaborative research that analyzes the phases of a steering committee’s involvement in Tunisia’s open government program.

3. Research Methodology

Our research is grounded in a collaborative approach that was implemented as part of the e-government unit’s work, which is attached to the Tunisian presidency (Prime Ministry). This initiative was conducted within the framework of the fourth phase of the Open Gov 2021-2023 program. The overarching goal of the Tunisian government’s reform is to enhance the quality of public services, particularly through the digitization of administration. The aim of our research is to critically analyze the public value embedded within the citizen participation framework in Tunisia’s open government initiative. To achieve this, we focus on three key elements that act as catalysts for value creation: the legitimacy of actors and stakeholders, the operationalization of public policy co-creation, and the conceptualization of “public value” (Carassus & Balde, 2020).

To better understand the dynamics of co-creating public value, we chose to immerse ourselves in the supervisory institution responsible for managing the Open Government program—the “Presidency of the Government,” the official designation of the Tunisian Prime Ministry. This approach aligns with the principles of collaborative research and adheres to an “inductive” methodology (Yu, 2020). It is important to note that “collaborative research” differs from both “action research” and “intervention research” (Mucchielli, 2005; Morrissette, 2013).

Our approach involves a partnership negotiation focused on driving change and producing co-constructed knowledge between stakeholders and the researcher (Clarke & Francolli, 2014). Established early in the implementation of the fourth Open Gov 2021-2023 plan, the balanced “practitioner-researcher” relationship fosters a redefinition of roles, where both the practitioner and the researcher acknowledge the “complementarity” of their respective knowledge. This allows for the pooling of conceptual insights and practical field expertise (Vinatier & Morissette, 2015; Morrissette, 2013). Our access to the “field” was facilitated through a competitive process, in which we were selected to represent the university component on the steering committee for the fourth OGP plan.

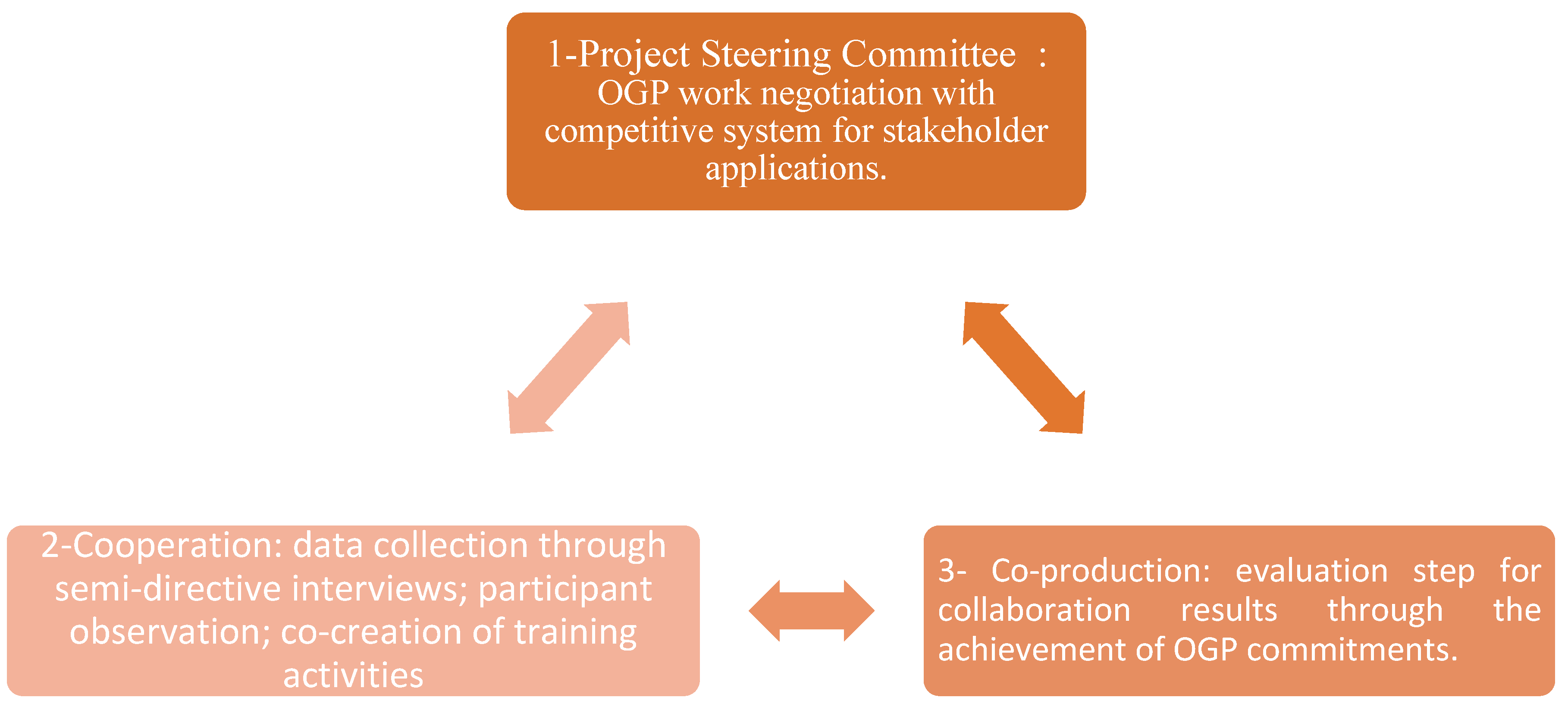

In addition to the data gathered through our involvement in this action and observation structure, we conducted a qualitative survey that included semi-structured interviews with various stakeholders of the program. This was complemented by a content analysis of the verbatim transcripts, documents produced by the general management of the e-government unit, as well as our own meeting minutes and the official records from the Project Steering Committee meetings, which are published in Arabic on the national OGP portal. The following diagram outlines the collaborative research process that we were able to implement, facilitated by our participation in the program’s Steering Committee:

Figure 1.

The collaborative research process undertaken to generate a research protocol.

Figure 1.

The collaborative research process undertaken to generate a research protocol.

The qualitative interview survey involved engaging with members of the “Project Steering Committee” for the 2021-2023 term, representatives from eight associations representing Tunisian civil society, managers within the e-government unit overseeing the initiative, and representatives from the ministries and institutions involved in the OGP process (see

Table 1 in the appendix). Primary and secondary data were collected from three key sources: semi-structured interviews, documentary analysis, and attendance at meetings and seminars organized by the program. The use of multiple data sources enabled triangulation, enhancing the verification and internal validity of the findings (Yin, 2000). With the collected primary and secondary data, we conducted a content analysis using a qualitative approach to data processing (Miles & Huberman, 2003). The semi-structured interviews followed interview guides structured around the themes outlined in

Table 2.

As a key stakeholder, we facilitated workshops during “OGP Week May 2022” and participated in discussions organized by the Ministry of Finance, particularly in relation to the enhancement of the “Open Budget Boost II” platform. We also engaged in strategic discussions during Project Steering Committee meetings (see

Table 3). The 23 semi-structured interviews with stakeholders from various backgrounds provided an opportunity to compare and validate the discourses collected (Miles, 1993). Transcribing these 23 interviews resulted in a verbatim text of 38,837 words. Using N’vivo 14 software, we analyzed the most frequently occurring words and identified linguistic and semantic associations among the actors (Weick, 1994). We also performed redundancy frequency queries to examine the reference grid and the coding within the theme dictionary, focusing on the frequency of key terms and the mapping of the semantic field of the actors, considering the contexts and interdependencies inherent in our research model. This internal analysis allowed us to organize keywords into thematic groups (Mucchielli, 1999).

Finally, we categorized the themes according to the three major stakeholders identified in our analysis: the creation of public value through the construction of an “ideal-type” of citizen leadership; political and institutional turnover; and the sovereignty of public policies. In line with our rigorous data collection process, the exploitation of the empirical material proceeded in two phases. The first phase involved selecting units and conducting a semantic analysis based on the “concepts” developed in our literature. In the second phase, we grouped verbatim excerpts line by line according to the thematic codes established in our framework (Bardin, 2013). The table below illustrates the axes of our research model, as identified in the literature review, alongside the coding used for the content analysis:

Table 4.

A review of the research activities and materials produced for the collaborative research protocol.

Table 4.

A review of the research activities and materials produced for the collaborative research protocol.

PSC stakeholders

2021-2023 |

Semi-structured interviews and verbatim analysis

Participatory observation of activities |

Production of data and research materials |

Dominant themes in the creation of public value |

|

-Semi-structured interviews

Co-creation and organization of a BMP awareness workshop in municipalities

-Advocacy for an open municipal budget

-Media coverage and use of social networks. |

-Verbatim

-Logbook

-Mapping of project stakeholders

-Innovation partnership

-Co-creating public policy |

-Citizen Budget

-Opening up public data

-Mapping cities and regions

Impact on public awareness of accountability and accountability

|

- 2.

Representatives of Ministries committed to the 4th plan through a commitment from December 2021 to December 2023 through “Commitment No. 4: To enshrine financial transparency”. |

Ministry of Finance and consultation workshops on the redesign of the national budget digital platform called “Myzanouyatina”4 with the support of the World Bank “BOOST II”.

- Observation and participation in meetings and discussions as part of the advocacy for a law to “regulate/close the Tunisian state budget for the 2020 financial year”. |

-PV Meeting in December 2021 to co-participate in the draft version of the specifications for the new version of the “BOOST I/II” open budget platform.

-PV June 2022 meeting, discussion of the final version of the Boost II platform draft with the World Bank and World Bank consultants |

-State budget platform: opening up public data

-Accountability

-Citizen participation in the public administration modernization program. |

- 3.

Representative association members of the PSC |

-Semi-structured interviews

Participation in online and face-to-face PSC meetings

Participation in the activities of OGP associations outside the PSC and “e-government” unit premises. |

-Verbatim

-TOT Training Content - Communication and Advocacy OGP

-Co-writing of minutes of PSC 2021-2023 meetings |

-A plea for open government

-Popularizing concepts and issues for citizens |

- 4.

Members of the general management “OGP” project focal point |

-Semi-structured interviews

-Interview guide

-Documentary analysis of legislative decrees and legal texts produced by the Presidency of the Government 2021-2023. |

-Verbatim

-Administrative documents

E-mail exchanges

-Minutes |

-Co-creating public policy

-Opening up public administration to its stakeholders. |

- 5.

International technical support and donors: OECD, NDI, UNDP, Expertise France, AFD Tunisia, World Bank. |

-Observations and participation in training days

-Observations and participation in discussions on a funding program for strategic studies and on the specifications for a new version of an open budget portal. |

- Meeting minutes

-Summary documents: specifications for the new version of the “BOOST II” portal |

-Participate in the referencing of expert contracts and specifications.

-Participation in the selection of experts

-Sovereignty and the national public policy agenda |

- 6.

Sample of stakeholders surveyed |

1-Top Manager- electronic administration

2- PSC members - institutional part

3- PSC’s associative component

4- Municipal component and stakeholders outside PSC

5- Technical partners |

-23 verbatims from semi-structured interviews

-Corpus analyzed: 38837 words

-Dictionary of terms |

-Participate in the referencing of expert contracts and specifications.

-Participation in the selection of experts

-Sovereignty and the national public policy agenda |

Table 5.

Coding grid (Bardin, 2013; Thietart, et al., 2003).

Table 5.

Coding grid (Bardin, 2013; Thietart, et al., 2003).

| Level 1 code |

Level 2 code |

How the code was drawn up |

| Theme 1: The Steering Committee and its stakeholders |

| Expertise/institution/ leadership/ experience |

Diversity of profiles |

Codes identified from OGP literature |

| Relationship with institutions/ availability/ legitimacy/ recognition |

Nature of interests and values |

Codes taken from management literature |

| Theme 2: Steering Committee follow-up and stakeholders |

| Agenda/ commitments made at the beginning of the term/ institutional recognition/ common objectives. |

Vision

Commune or not |

Codes emerging from interview verbatims |

| Joint activities/ coordination/ meetings/ drafting of commitments |

Operating structure |

Codes emerging from interview verbatims |

| Mission to share knowledge of the field/ legitimacy at local level/ relations with foreign technical partners/ training or empowerment |

Knowledge

broadcast or not |

Codes from observations |

| Theme 3: Steering committee operations and stakeholders |

| Minutes exchanged/ strategy development/ commitment follow-up/ advocacy activities |

Installation techniques |

Codes emerging from interview verbatims |

| Conflicts of “values”/Lack of institutional recognition/absenteeism of institutional stakeholders/political turn-over or political support |

The obstacles |

Codes emerging from interview verbatims |

4. Thematic Analysis of Results

4.1. Citizen Expertise and Local Knowledge: Fostering Citizen Leadership

Our research highlights that the establishment of the steering committee set a significant precedent by launching a call for “interest,” which allowed for the inclusion of a broad range of complementary and diverse profiles. This committee underwent a selection process to identify civil society representatives with expertise and established connections within the Tunisian associative landscape. The committee played an active role in drafting long-term goals, referred to as “commitments,” and in organizing and conducting advocacy and training workshops for local authorities and municipalities in Tunisia. Its activities included advocacy on the theme of “open budgeting for municipalities,” supported by media and social network engagement.

All interviewees, whether from institutional or associative backgrounds within the steering committee, emphasized that the involvement of civil society lent new legitimacy to the process. However, citizen participation in the OGP framework also required an active presence during the development of the committee’s work agenda. Initially, this “citizen” presence was seen as a temporary phase, as there was no formal call for applications or expressions of interest. This lack of formalization led to concerns regarding the sustainability and potential for standardization of the experiment. The e-government unit, attached to the presidency of the government, was designated as the focal point for the OGP project to oversee its progress and coordinate with technical partners involved in the project’s empowerment and financing. For the purposes of this research, we refer to this unit as the “administration lead.” Interviewees confirmed that the formal nature of the Project Steering Committee’s selection process was critical to their candidacy and to the legitimacy of their involvement.

“The impact was that government and civil society were working together in a joint commission was completely innovative. It’s uncommon in public management processes, the only comparable experience was the joint commission at the Ministry of Finance (a joint commission which no longer exist). The selection process has been respected this time, it’s a competitive, transparent process for the current Project Steering Committee. I’m proud of this selection requirement, as it lends credibility to our work as a civil society”.

Verbatim Excerpt 1: Member of the Project Steering Committee Representing Civil Society

The institutional managers interviewed assert that the selection procedure represented a “qualitative” improvement, as it helped legitimize the choices made for the steering committee, particularly those representing civil society. In contrast, the remaining institutional members of the Project Steering Committee, namely the ministries and agencies involved, were responsible for making “commitments” or “proposals” to digitalize public services within their respective sectors.

However, the absence of ministry representatives—despite the possibility of remote meetings—highlighted the limitations of their institutional commitment. Civil society members of the Project Steering Committee attributed this to a lack of recognition for the co-creation methodology upon which the OGP was founded. Indeed, meetings were seldom followed by official “minutes” from the ministries, and these representatives never extended invitations for Project Steering Committee members to meet at their offices (although Project Steering Committee members and associated organizations did organize meetings at their own premises).

The associations that formed part of the Project Steering Committee were well-trained in the OGP’s assessment mechanisms and possessed a wealth of skills and knowledge. As a result, the administration could no longer claim a monopoly on information or expertise, which fostered the development of a collaborative relationship for the co-creation of public value.

“Our administration knowledge is a component of our involvement in the Project Steering Committee, which is a forum for exchange between peers to share experiences and best practices in terms of governance, transparency and the fight against corruption. We have successfully advocated and lobbied for the Access to Information Act and the Whistleblower Protection Act. Indeed, we were even consulted in the drafting of the law act. We can also edit a shadow report, like a veto, to the decision-making process”.

Verbatim Excerpt 2: Representative of an Association on the Project Steering Committee.

Previously overlooked in past programs, the institutional innovation in this case lies in the Ministry of Finance’s initiative to organize meetings aimed at fostering citizen participation in the collaborative development of specifications for the “open and participatory budget” digital platform. Representatives from the most active associations in Tunisia were invited to contribute to the drafting of the specifications for the “BOOST II” website. Commissioned by the Ministry of Finance, this effort to open up data to citizens is viewed by the Ministry’s representative as a “delicate” process.

4.2. The Role of the Project Steering Committee in the “Co-Construction” of Public Policies

The co-creation of the public policy process allows for the recognition of each stakeholder’s capacity to contribute to the implementation of commitments. Although the ministerial side was acknowledged as legitimate, interviewees did not perceive it as having the most significant impact in the process

“The success of OGP lies in the working approach, which is a new way of developing public policies, a participative approach, a new culture, and a broader spectrum for drafting commitments. We are aware about these transparency challenges and to make us opening up our administration data to civil society.”

Verbatim Excerpt n°3: Director or Manager, Member of the Project Steering Committee.

The co-creation of public policy serves as a form of pedagogical training for all stakeholder entities. Paradoxically, the institutional component of the steering committee is viewed by the lead administration as the one most in need of fully embracing the values and becoming more aware of the resources at its disposal.

“Quite often the correspondence we send to the ministries is not followed up, there is no focal point with whom we can follow up the correspondence or the assessment of the ministries concerned. There’s a great lack of understanding in the collaboration even between ministries, sometimes the commitments put forward are outside the scope of the OGP, which underlines our feeling of frustration, there’s definitely a lack of understanding of this initiative.”

Verbatim Excerpt No. 4: Top Manager 1 from the Steering Committee

“We even have partners who make a commitment with the expectation that we will carry out the project, finance it and implement it as “a form of institutional subcontracting”. However, open gov (OGP) is not about grafting itself onto institutional administrative structures and acting as a financial backer or technical service provider. It’s about actors creating their own digitization tools”.

Verbatim Excerpt No. 5: Top Manager 2 from the Steering Committee

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a notable acceleration in the establishment of electronic and digital administrative processes was observed, particularly to facilitate Tunisia’s receipt of international aid for strategic sectors such as health and social welfare (Amour et al., 2021). The social cash transfer program was officially launched on June 29, 2021, following the enactment of Law No. 2021-28 on June 22, 2021, which ratified the loan agreement signed on April 2, 2021, between the Republic of Tunisia and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The actions taken by the Ministry of Social Affairs exemplify the swift integration and verification of citizen data, enabling the government to efficiently coordinate efforts across various ministries and with international donors. This initiative was significantly supported by the public and private mobile telecommunications sectors, which played a crucial role in communicating with and verifying the status of individuals affected by COVID-19 and in need of social assistance.

The efforts to expedite the development of legal frameworks enabling “data interoperability” were not coordinated by the general management of the “e-government unit.” Instead, it was the Ministry of New Technologies and Digital Transformation that assumed responsibility for this task. Moreover, the lead agency for the Open Government Partnership (OGP) was not recognized by the Presidency of the Government as the primary entity overseeing the digitization project, a role that was instead attributed to the Ministry of New Technologies and Digital Transformation.

“The legal framework quickly promulgated as a decree-law Decree-law of the Head of Government No. 2020-17 of May 12, 2020, relating to exclusive social code attribution for each citizen: on May 12, 2020, and the act quickly have been adopted by parliament on May 15, 2020giving by the way the mission to the Ministry of Local Affairs new functionalities and digital operability upgrade in order to coordinate the various public programs. Since 2010, our ambition has been to have a unique social code that goes beyond the count of social funds “CNRPS or CNSS” as coming from public institution (CNRPS affiliation) or private sector (CNSS).”

Verbatim Excerpt No. 6: Institutional Manager and Member of the Project Steering Committee

4.3. Sovereignty of Public Policies in Relation to Donors and Technical Partners: Competing/Conflicting Values and Expertise

Tunisia’s “democratic transition” has been marked by frequent changes in government, which have significantly impacted the continuity of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) program. Each transition has led to interruptions in the program’s implementation until a new ministerial cabinet was formed and new directives were issued. With a change in government approximately every eighteen months, maintaining continuity in political and public actions has proven challenging. New teams of politically connected “top managers” have been appointed to ministries, raising concerns about the erosion of the Weberian distinction between administration and politics. The resulting politicization of the public administration, compounded by the turnover of political personnel, has contributed to the deterioration of public value (Carassus & Balde, 2020).

Each ministerial departure has been accompanied by a decline in efficiency and a erosion of the credibility of commitments made. This has led to growing doubts about the strategy and action plan collaboratively developed by the partners during the current term.

“The lack of political support is one of the main handicaps of OGP. Lack of political lobbying and intervention means that commitments are not fulfilled while reforms are not implemented quickly. The example of the Energy EI initiative5make us figure out the issue. If we had had political support, we could have joined the initiative. The civil society report is ready, everything is ready for joining the international initiative, but we need political support to join EITI. The limit of OGP is political leadership, which is at the heart of the process. Why not include ministers in the Project Steering Committee?

Verbatim Excerpt No. 7: Representative of the Association on the Project Steering Committee

“Frustrations are explained by governmental changes and political instability, as long as we start to convince, to recognize institutional partners that very quickly we are stopped in the process: we even have ministries that disappear from one government to another, the most obvious example is the Ministry of Local Affairs that disappeared another time and becomes again a secretariat affiliated to the Ministry of Interior.”

Verbatim Excerpt No. 8: Top Manager 3, Member of the Project Steering Committee

Sovereignty issues become particularly evident in the context of developing the strategy for the fourth plan, where the involvement of a technical partner was required to ensure the quality of the consultancy’s expertise. However, the allocated budget was insufficient to cover such expenses. Contrary to expectations, civil society was neither consulted in the selection of the expert nor involved in the conditions under which the strategy was developed.

While the use of technical cooperation in formulating commitments within the framework of the OGP is within the rights of the administering entity, members of the Project Steering Committee express reservations about relying on the technical support provided by the funding agency. They observe that such support often undermines the principles of co-creation and collective decision-making.

“The UNDP has turned to the OGP in recent months out of spite, as has the NDI. The World Bank is not as involved in Tunisia as it is in other countries. The OECD, on the other hand, is one of the first to sign up to recommendations and the production of a strategy that we’re finding hard to achieve.”

Verbatim Excerpt No. 9: Manager and Member of the Project Steering Committee

“The OECD offered to help us draw up a strategy, but the expert was chosen in consultation with the donor, without any real definition of the strategy’s challenges.

Verbatim Excerpt No. 10: Institutional Manager of the Project Steering Committee

5. Analysis of Field Observations

The findings of this study align with the theoretical framework outlined earlier. Initially, we sought to explore the foundations of the legitimacy of the actors involved in the OGP program. It is evident that citizen leadership plays a crucial role as a source of legitimacy, being leveraged to underscore the quality of proposals put forward by civil society members and to enhance the overall value of the program. Furthermore, the creation of public value involves a strategic approach to selecting actors who contribute to the co-creation of public policies. This approach is validated by a civil society that asserts itself at the local level, particularly through leadership grounded in substantial social capital (Carassus & Balde, 2020). Citizen leadership emerges as a pivotal element in mobilizing support and raising awareness around the OGP reform program.

The absence of representatives from the ministries responsible for the commitments during the 2021-2023 term—who were formally designated as members of the steering committee—highlighted a significant weakness in the political support for the OGP project. The co-construction methodology, however, facilitated overlapping roles, enabling civil society actors to engage in lobbying, organize media campaigns, and present policy papers to parliament.

In this context, political “turnover” has been identified as a primary obstacle to the effective implementation of public policies, particularly within a political transition that demands public scrutiny and innovation (Bair, 2022; Rafidinarivo et al., 2017). Moreover, the political ties of administrative personnel have reinforced a form of clientelism, a phenomenon observed in the aftermath of the revolution (Ben Mansour & Ben Kahla, 2022).

Finally, the findings from the field survey emphasize the issue of ownership, allowing for a reassessment of the sovereignty of public policies in Tunisia, particularly in relation to the OGP program. Specifically, the commitments made under the program should be reflected in the budgeting process by the Ministry of Finance, which is designated as the lead ministry for the project. Furthermore, the financing of OGP program activities by technical partners and donors raises concerns about the coherence of e-government agendas and the activities proposed.

6. Conclusions

This research highlights the essential roles of transparency, accountability, and citizen participation in the co-creation of public reforms. As Tunisia moves forward with its fourth Open Government Partnership (OGP) plan for 2021-2023, efforts have been made to strengthen its planning processes by establishing a participatory steering committee open to civil society.

Focusing on the “creation of public value,” this committee aimed to distance itself from executive power by co-constructing public decision-making within the framework of the OGP. Through a collaborative approach, this research has uncovered two key paradoxes and a fundamental tension within the OGP program.

The first paradox involves the co-construction process, which often leads to the adoption of imported solutions, treated as “one best ways,” detached from the country’s institutional realities. This creates a disconnection between the technical and financial partners’ recommendations—often framed as best practices—and the co-creation dynamics desired by the steering committee.

The second paradox highlights the leadership competition that emerges despite the supposed collaboration among partners. The increasing influence of civil society often stands in contrast to the perceived passive role of public administration. This dual movement is closely tied to the divergent interests of the various partners and the lack of political support. The co-construction of public value is both a prerequisite and a consequence of the problematic transfer of competencies to civil society. Furthermore, it appears to be both a cause and an effect of the weakening role of public administration, which is further exacerbated by political instability.

Our field survey also identifies a fundamental tension between local (municipal) and national levels in the implementation of the OGP at the local authority level. Municipalities are invited to apply for international funds linked to national programs, with the national Project Steering Committee tasked with providing necessary support for their selection. However, once selected, municipalities face significant challenges, primarily due to uncertainties surrounding the national decentralization policy. These challenges include:

Difficulty in financing development projects, with local decision-makers forced to seek or create alternative solutions through institutional “bricolage.”

The Project Steering Committee’s provision of technical support without financial resources, intensifying frustration among local actors involved in the project.

Local governance instability, with municipalities lacking Council Presidents or Municipal Councils, exacerbating the skills deficit. While civil society has succeeded in assuming some of the public sector’s roles at the national level, municipalities remain the weakest link in the knowledge dynamics within the OGP field.

Through participant observation, we have gained new insights into the evolution of public policy in Tunisia. However, the study’s primary limitation lies in the difficulty of addressing the “time” variable, as our research was conducted during a specific phase of the OGP program’s implementation (2021-2023). We were unable to capture all stages of the co-construction process, particularly the initial creation phase (2013-2021). The evolving composition of the steering committee, both in terms of numbers and qualifications, suggests that a longitudinal study, extended over a longer period, would be beneficial. A historical analysis of the OGP process in Tunisia, especially within the broader context of the “democratic transition,” could further strengthen our findings.

Moreover, it would be valuable to explore whether our results can be generalized to other levels or forms of public planning, particularly in relation to the preparation of the national five-year development plan. An additional area of study could involve examining dynamics within civil society, particularly the emergence of “leaders” within this sector. This dynamic is both supported and influenced by foreign funding, as national associations, after training municipalities and local civil society actors in the principles of the OGP, find themselves competing for access to international funds. This rivalry among civil society organizations plays a significant role in its professionalization, acting as a springboard for former activists to transition into business, either by offering expert services or taking on roles within international institutions.

Finally, the question of transitioning from planning to the actual implementation of plans, and the resistance to change encountered on the ground, warrants further analysis.

| 1 |

INAI: Instance Nationale d'Accès à l'information (the right of access to information is article no. 9 in the Tunisian constitution of January 24, 2014). |

| 2 |

INDP: Instance de Protection des données publiques (Public Data Protection Authority), instituted by organic law no. 2004-63 of July 27, 2004 on the protection of personal data. |

| 3 |

INLUCC: Instance Nationale de Lutte Contre la Corruption, established by framework decree-law no. 2011-120 of November 14, 2011. |

| 4 |

The development of a new open budget platform "Myzanouyatina" (Our budget in Arabic) in line with Tunisia's commitment to the OGP through organic law n°2019-15, on the organic law of the budget open to citizens and all stakeholders. |

| 5 |

|

References

- Agulhon, S.; Mueller, T.M. How the Drafting of the Clayton Antitrust Act Helped Spread the Managerial Approach to Efficiency. Adm. Soc. 2022, 55, 591–612. [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, T.; Khalifa, R. Researching the lived experience of corporate governance. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2013, 10, 4–30. [CrossRef]

- Allard-Poesi, F. (2003). Coding data, in Giordano, Y. Conduire un projet de recherche dans une perspective qualitative, EMS, Caen.

- Albercht, S.L. (2002). “Perceptions of Integrity, Competence and Trust in Senior Management as Determinants of Cynicism toward Change.” Public Administration & Management, 7 (4), 320-343.

- Alter, N. (2006). Sociologie du monde du travail. Presses universitaires de France, Paris.

- Altintas, G. & Royer, I. (2009). Building resilience through post-crisis learning: a longitudinal study of two periods of turbulence. Management, 12(4), Special Issue, 266-293.

- Covid, W., Dashboard. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/.

- Argyris, C. Action science and organizational learning. J. Manag. Psychol. 1995, 10, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Armandy, A. & Rival, M. (2021). Public innovation and new forms of public management. [Online]: https://ideas.repec.org/s/hal/journl.html, consulted on 20/12/2021.

- Baillette, P.; Barlette, Y.; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, A. Bring your own device in organizations: Extending the reversed IT adoption logic to security paradoxes for CEOs and end users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 76–84. [CrossRef]

- Bair, A. (2022). The challenges of spatial planning in Tunisia: from government to governance? Revue Gouvernance / Governance Review, 19(1), 79-102.

- Bardin, L. (2013). L’analyse de contenu, Presse Universitaires de France, Quadrige, Paris.

- Bastiège, M. & Favreau, F. (2019). Natural resource management, the return of the regal state? Politiques & management public, 36(4), 353-370.

- Ben Hassine, A. et al., (2020). Citizen participation and e-participation in the context of democratic transition in Tunisia, the emperor’s new clothes? Annales des Mines-Gérer et comprendre.13-24.

- Ben Mansour, K. & Ben Kahla, K. (2021). The Island of integrity as an anti-corruption approach : a Tunisian case study. Journal of Economics and International Business Management, 9, 145. [CrossRef]

- Ben Mansour, K. (2020). Middle management versus top management: How to enhance the whistleblowing mechanism for detecting corruption and political connection. A case of international donor funds in Tunisia. Social Business Westburn, 10 (3), 231-245.

- Bezes, P. (2007). Construire des bureaucraties wébériennes à l’ère du New Public Management Revue Critiques Internationales.2 (35), 9-29.

- Bozeman, B. Public-Value Failure: When Efficient Markets May Not Do. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 145–161. [CrossRef]

- Bouckeart, G. (2003). La réforme de la gestion publique change-t-elle les systèmes administratifs. Revue française d’administration publique, 1(1), 39-54.

- Bourrassa, B. et, al. 2017.Accompanying collaborative research groups: what does this “doing with” entail? Phronesis, 1-2(6), 60-73.

- Bryson, J.M.; Ackermann, F.; Eden, C. Putting the Resource-Based View of Strategy and Distinctive Competencies to Work in Public Organizations. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 702–717. [CrossRef]

- Burlaud, A. et al., (2019). Editorial Managing sovereignty: the regal in all its states! Politiques & management public, 36(4), 349-351.

- Burlaud, A. & Gibert, P. (1984). L’analyse des coûts dans les organisations publiques: Le jeu et l’enjeu. Politiques et management public, 2(1), 93-117.

- Cappelletti, et al., (2015). Contribution au pilotage de la masse salariale par la fonction RH dans les établissements publics de santé: premiers résultats d’une recherche collaborative. Revue de gestion des ressources humaines, (4), 58-73.

- Carassus, D. et al., (2016). Compte rendu de la table ronde” La définition d’un projet stratégique : comment évaluer ses politiques et déterminer les priorités”-Entretiens de l’innovation Territoriale. ID efficience territoriale, (29).

- Carassus, D. & Balde, K. (2020). Analysis of local public governance: proposal of a reading grid and exploratory characterization of French intercommunality practices. Finance Contrôle Stratégie, 7.

- Charreire, S. & Durieux, F. (1999). Exploring and testing. Méthodes de recherche en management, 57, 80.

- Chérif, F. & M. (2012). Revolution, elections and the evolution of the Tunisian political field. Confluences Méditerranée, (3), 107-116.

- Clarke, A. & Francoli, M. (2014). What’s in a name? A comparison of ’open government’definitions across seven open government partnership members. JeDEM-eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government, 6(3), 248-266.

- Crowley, J. (2003). Uses of governance and governmentality. Critique internationale, (4), 52-61.

- Dupuis, J. (2020). “1990-2020: 30years of theses in public management. Recognition and legitimization of a disciplinary field”. Gestion et management public, 8(2), 6-19.

- De Vaujany, F.X. (2006). Pour une théorie de l’appropriation des outils de gestion: vers un dépassement de l’opposition conception-usage. Management & Avenir 3 (9). 109-26.

- Dudézert, A. (2018). The digital transformation of companies. La Découverte. Repères.Paris.

- Dumez, H. (2011). What is qualitative research? Le Libelliod’Aegis, 7(4-Winter), 47-58.

- Easterly, W. (2003). Can foreign aid buy growth? Journal of economic Perspectives, 17(3), 23-48.

- Favoreu, C. et al., (2020). The determinants of different types of local public innovation: a national multi-factor analysis. International Management 24 (4). 34-47.

- Féral, B. (2022, June). L’évaluation à l’épreuve des valeurs. In Colloque annuel de la revue” Politiques et Management Public” : La relation Savoir-Pouvoir dans l’action publique face à l’incertitude.

- Frucquet, P. et al. (2022). Numérique et nouveaux modes de production de valeur publique dans les collectivités locales. In Colloque annuel de la revue Politiques et Management Public, CNAM.

- Foucault, M. (1963). Preface to transgression. Critique, n° 195-196. Quarto-Gallimard. Paris. 261-278.

- Goter, F. & Khenniche, S. (2022). Évaluation des politiques publiques : vers une pratique intégrée au pilotage de l’action publique. Revue Gestion & Management Public, vol°10, n°3, p.35-57.

- Grave, C. (2015). Ideas in Public Management Reform for the 2010s. Digitalization, Value Creation and Involvement. Public Organization Review, 15, 49-65.

- Grossi, G. (2020). A Public Management Perspective on Smart Cities: ’UrbanAuditing’ for Management, Governance and Accountability. Public Management Review22 (5), 633-647.

- Hadaya, P. et al., (2019). Digital transformation projects: five pitfalls to avoid. Gestion,44 (3): 94-110.

- Hartley, J.; Alford, J.; Knies, E.; Douglas, S. Towards an empirical research agenda for public value theory. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 670–685. [CrossRef]

- Hatchuel, A.; Molet, H. Corrigendum to “Rational modelling in understanding and aiding human decision-making: About two case studies” [European Journal of Operational Research 24 (1986) 178–186]. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 252, 349. [CrossRef]

- Henriot, C. et al., (2018). Asian perspectives on Smart Cities. Flux 114 (4): 1. [Online]: accessed on 31/01/2022. [CrossRef]

- Hibou, B. (2020). Reading neo-liberal bureaucracy with Weber, in En finir avec le New Public Management, Management International, 24(4), 183-184.

- Hudon, P. A. & Mazouz, B. (2014). Le management public entre “tensions de gouvernance publique” et “obligation de résultats”: Vers une explication de la pluralité du management public par la diversité des systèmes de gouvernance publique. Gestion et management public, (4), 7-22.

- Lorino, P. (1999). In search of lost value: building value-creating processes in the public sector. Politiques et management public, 17(2), 21-34.

- Mabkhout, A. & Ben Kahla, K. (2013). Modernization of public administration. Evaluation report of the UNDP Tunisia project.

- Martins, J. et, al. (2021). The use of scoring systems during COVID-19. Southern African Journal of Public Health incorporating Strengthening Health Systems, 5(1), 3-9.

- Matyjasik, N. & Guenoun, M. (2020). En finir avec le New Public Management. Management international/International Management/GestiònInternacional. 24(4), 183-184.

- Mergel, I. (2022). The co-creation of public value by digital departments: an international comparison. Action publique- Recherche et pratiques, (6), 7-16.

- McIlvenny, & al. “New perspectives on discourse and governmentality”. Studies of Discourse and Governmentality: New perspectives and methods, edited by Paul McIlvenny, Julia Zhukova Klausen and Laura Bang Lindegaard, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2016, pp. 1-70. [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (2003). Analyzing qualitative data. De Boeck Supérieur.

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard university press.

- Moore, M. H. & Khagram, S. (2004). On creating public value. What Businesses Might Learn from Government about Strategic Management.Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative WorkingPaper, 3.

- Morrissette, J. (2013). Action research and collaborative research: what relationship to knowledge and knowledge production? Nouvelles pratiques sociales. 25(2), 35-49.

- Mucchielli, A. (2005). Qualitative research and knowledge production. Le développement des méthodes qualitatives et l’approche constructiviste des phénomènes humains, Recherches qualitatives, Hors-série, 1, 7-40.

- Mulgan, G. & Albury, D. (2003). Innovation in the public sector. Strategy Unit, Cabinet Office, 1(1), 40.

- Nesti, G. (2020). Defining and assessing the transformational nature of smart city governance: observations from four European cases. Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives86 (1): 23-35.

- Osborne, S. (2006). The New Public Governance? Public Management Review,8 (3): 377-387.

- Osborne, S.P. From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation?. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 225–231. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S. et al., (2016). Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A Suitable Case for Treatment? Public Management Review 18 (5): 639-53.

- Pardo-Bosch, F.; Pujadas, P.; Morton, C.; Cervera, C. Sustainable deployment of an electric vehicle public charging infrastructure network from a city business model perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71. [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, V. et al., (2006). Patterns of co-production in public services: Some concluding thoughts. Public management review, 8(4), 591-595.

- Park, C.H.; Kim, K. Exploring the Effects of the Adoption of the Open Government Partnership: A Cross-Country Panel Data Analysis. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2022, 45, 229–253. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.; Parycek, P.; Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Smart governance in the context of smart cities: A literature review. Inf. Polity 2018, 23, 143–162. [CrossRef]

- Pesqueux, Y. (2020). New Public Management (NPM) and Nouvelle Gestion Publique (NGP). [Online]: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-02506340, accessed on 20/11/2021.

- Piotrowski, S.J. (2017). The “Open Government Reform” Movement: The Case of the Open Government Partnership and U.S. Transparency Policies. [Online] accessed 20/01/2022. [CrossRef]

- Porter M.E.& Kramer R. M. (2011). “Creating shared value”, Harvard Business Review, January-February, p.62-77.

- Purwanto, A. et al., (2020). Citizen Engagement WithOpen Government Data: A Systematic Literature Review of Drivers and Inhibitors. International Journal of Electronic Government Research (IJEGR), 16(3), 1-25.

- Refle, J-E. (2019). Civil society and democratic framing in Tunisia. How democracy is framed and its influence on state, PhdUniversité de Lausanne. [Online]http://serval.unil.ch, accessed 20/01/2022.

- Revel, J. (2002). Résistance/Transgression, in Le Vocabulaire des Philosophes. Philosophie contemporaine (XXe siècle), coordinated by Zarader, J.-P. 2002. Ellipses, Paris, 888-889.

- Rey, O. (2014). A question of size. Stock, Paris.

- Rival, M. & Ruano-Borbalan, J. C. (2017). The making of co-constructed public policies: ideology and innovative practices. Politiques et management public, 34(1-2), 5-16.

- Roussel, P. & Wacheux, F. (2005). Management des ressources humaines: Méthodes de recherche en sciences humaines et sociales. De Boeck Supérieur.

- Supiot, A. (2015). Governance by numbers. Cours au collège de France (2012-2014). Editions Fayard, Collection “ Poids et Mesures du Monde “.

- Wacheux, F. (1996). Qualitative methods and management research. Economica, Collection Gestion. Paris.

- Rafidinarivo, H. C. et al., (2017). Political transition and humanitarian transition: Comparative political analysis of financial transition. Humanitarian transition: states of research, French Red Cross Fund.

- Sen, A. (2000). A new economic model: development, justice, freedom. Odile Jacob. Paris.

- Thietart, R. A., et al., (2003). Méthodes de recherche en management. Dunod.

- Vinatier, I. & Morrissette, J. (2015). Collaborative research: issues and perspectives. Carrefours de l’éducation, (1), 137-170.

- Yu, H.H. (2020). Effectiveness of collaborative gender research between researchers and practitioners in federal law enforcement authorities: the value of a co-production process. Revue Internationale des Sciences Administratives, 86 (3), 591-606.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).