1. Background

Occupational mental health is a continuous and dynamic state of internal balance between job demands and the mental resources available to manage the occupational environment [

1,

2]. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated workplace demands and significantly impacted the mental health of healthcare professionals, resulting in high prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, insomnia, and substance abuse [

3].

Healthcare workers in Africa experienced mental health disorders [

4,

5,

6,

7], with additional challenges such as staff shortages, underfunding, and inadequate infrastructure [

8,

9,

10]. Evidence highlights that nurses, women, and workers with less experience were particularly affected by mental health disorders during the pandemic [

5,

11]. Additionally, high rates of mental health issues were reported in countries like Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, and Kenya [

12,

13,

14,

15].

The literature reveals a gap regarding the mental health of healthcare professionals in Angola and interventions aimed at supporting these professionals. However, research by Miguel (2022) [

16], conducted in a public hospital in the southern region of the country, reported significant psychological distress among Angolan healthcare professionals even before the first confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Angola faces a critical shortage of mental health professionals, with only 0.06 psychiatrists and 0.18 psychologists per 100,000 inhabitants [

17,

18], alongside a healthcare workforce far below WHO standards [

19]. Poor working conditions, inadequate remuneration, and professional undervaluation represent significant psychosocial risks, especially for public-sector nurses [

20,

21].

1.1. Consequences of the Impact on Healthcare Professionals’ Mental Health

Healthcare professionals are particularly vulnerable to mental disorders such as burnout, depression, anxiety, and substance abuse [

22,

23,

24], with PTSD emerging as a more recent concern [

25]. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these conditions, increasing tendencies toward suicide, sleep disturbances, and acute stress (11,26–30).

These mental health challenges impact not only workers but also healthcare organizations and systems. Burnout, for instance, is associated with reduced patient safety, lower quality of care, and increased medical errors [

31,

32,

33]. Presenteeism, defined as the condition in which professionals continue to work despite being unwell, reduces productivity may compromise care quality and is associated with burnout [

34,

35]. Depressive disorders contribute to absenteeism [

36], presenteeism, and turnover, which further affect the quality of care [

37,

38]. Additionally, substance abuse increased during the pandemic [

39,

40], with significant prevalence in certain African countries [

41].

The economic costs of mental health disorders are substantial. For example, burnout among healthcare professionals in the U.S. leads to annual losses estimated at

$4.6 billion due to turnover and reduced working hours [

44]. These findings underline the importance of prioritizing mental health management in healthcare organizations, particularly in the post-pandemic context.

1.2. Digital Transformation and Healthcare Professionals’ Mental Health – Telemedicine as a Resource for Angola

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital technologies in healthcare, particularly telemedicine, to address increasing mental health demands and resource shortages [

42,

43]. Telemedicine extends beyond technology adoption, aiming to add value, to improve access, optimize processes, and enhance the patient-provider relationship [

44]. Within this framework, telepsychiatry — a branch of telehealth — offers reliable and effective mental health care, whether conducted synchronously or asynchronously [

45,

46].

Despite its advantages, digital transformation poses ethical and operational challenges, such as privacy concerns, data protection, the need for tailored infrastructure as well as scientific, clinical, and regulatory challenges [

47]. Digital interventions, ranging from smartphone apps to computer-based therapies, have proven effective in promoting accessibility and personalization of care (45,48,49). For example, during the pandemic, initiatives like Malaysia’s Psychological First Aid protocol via WhatsApp [

50] and Mount Sinai’s symptom monitoring app in the U.S. [

51] expanded mental health care access for healthcare professionals. Similarly, digital applications in Spain and the U.K. demonstrated reductions in anxiety and depression, though further studies are needed to evaluate their long-term efficacy [

52,

53].

In Africa, digital health innovation is growing, with 14% of initiatives related to telemedicine [

54]. However, the adoption of telepsychiatry remains limited due to infrastructural and cultural challenges [

55]. In Angola, recent digital projects have focused on healthcare service delivery and information systems but have not fully explored telemedicine for mental health [

54]. A prominent private healthcare network in Angola, with a robust digital infrastructure and experience in teleconsultations during the pandemic, is well-positioned to lead advancements in telemedicine.

The integration of telemedicine into this network could address significant barriers, such as limited access to mental health care and geographical disparities. This study contributes to filling a critical gap in the literature by exploring telemedicine’s role in supporting healthcare professionals’ mental health in Angola.

1.3. Contextualization and Evaluation of Workers’ Mental Health

A prominent private healthcare network in Angola plays a significant role in the country’s healthcare landscape, operating a central tertiary hospital in Luanda and 23 partner clinics across 16 provinces. Employing approximately 3,000 workers, the network provides primary and secondary care, with referrals to its central facility.

The network includes a structured mental health circuit comprising a medical center and a Social Support Office. The medical center offers general and occupational health consultations, with referrals to mental health services based on clinical criteria. The Social Support Office provides psychological support, self-help groups, and educational lectures. However, from 2020 to 2024, only 39 psychology and 58 psychiatry consultations were conducted for workers, raising questions about the perception of these services among professionals and whether the circuit adequately addresses the needs of healthcare workers in geographically distant units. These observations underscore the necessity of implementing a specific occupational mental health program to ensure support across the network. In this context, telemedicine emerges as an opportunity to expand access and coverage of mental health care.

Although Angola has general mental health legislation, the Angolan General Labor Law does not include provisions for occupational mental health, and national policies lack targeted strategies for healthcare workers. This legislative gap further emphasizes the importance of developing structured programs tailored to the needs of healthcare professionals within the private healthcare network.

This study aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), contributing to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). It aims to address the gap in the literature on digital mental health interventions in Angola by exploring the factors influencing healthcare workers’ predisposition to adopt telemedicine as a tool for mental health support and proposing a tailored telemedicine model suited to the network’s context.

2. Methods

This observational, cross-sectional study employed a mixed-methods approach, primarily quantitative, complemented by a qualitative method. The aim was to provide an integrated approach to the phenomenon under study: the predisposition to adopt telemedicine. The quantitative approach targeted workers who may receive care, while the qualitative approach focused on professionals providing mental health care. The objective was to achieve complementarity between methods for better clarification and explanation of the results.

Research Questions:

This study aims to respond to the following questions:

Q1 - What are the main factors influencing the predisposition of healthcare workers, both at the main facility and partner units, in Angola, to adopt telemedicine as a potential approach for their mental health? (Quantitative Approach).

Q2 - What are the perceptions of mental health professionals regarding telemedicine and its adoption as a tool to support the mental health of workers in a private healthcare network in Angola? (Qualitative Approach).

2.1. Quantitative Method

This is an observational, cross-sectional, and descriptive study.

2.1.1. Study Population and Sampling

The study population included all healthcare workers directly involved in the provision of patient care within the private healthcare network. This group encompassed professionals from diverse categories, such as physicians, nurses, laboratory and imaging technicians, physiotherapists, pharmacy technicians, and administrative staff. Workers with less than three months of experience in the network and external collaborators were not included.

Participants were drawn from three regions of Angola — the capital (Luanda), eastern, and southern regions — focusing on units with the highest number of healthcare workers. Sampling followed a snowball technique, where initial participants shared the survey with their professional networks, enabling broader participation.

2.1.2. Information Sources and Data Collection

Data collection was conducted using a culturally adapted questionnaire distributed at the main facility and partner units of the private healthcare network during February and March 2024. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the data collection process. Participants provided prior consent for participation and were free to withdraw at any time. The questionnaire was distributed and completed online, with an estimated completion time of 10 minutes, accessed via a link directing to the Google Forms platform.

Questionnaire and Cultural Adaptation

The questionnaire used for quantitative data collection among professionals in the private healthcare network in Angola was developed based on the instrument by Cormi C. et al. (2021), presented in the article “Telepsychiatry to Provide Mental Health Support to Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Crisis.” The questionnaire used in this study does not evaluate indirect dimensions, and the items were intended solely for descriptive analyses without score attribution.

The original English questionnaire was culturally adapted to Portuguese, with a pre-test conducted on a sample of n=32, where 96.6% of participants found the questionnaire easy to understand (further details on cultural adaptation are provided in Supplementary Material S1.

Study Variables

The independent variables in the study include participants’ sociodemographic data (gender, age, professional category, years of work experience, and geographic area of the health unit). The dependent variables are determined by the question groups in the questionnaire. The final version of the survey is available in Supplementary Material S1.

2.1.3. Data Analysis and Processing

Data analysis was performed using statistical methods with version 29 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Descriptive statistics were calculated as absolute frequencies and percentages. Bivariate analyses were conducted using the Chi-Square test, with Fisher’s exact test applied when necessary. Statistical significance was considered at a 5% level (P<0.05).

Multivariate binary logistic regression was performed for variables with statistically significant associations in the bivariate analysis. Models were considered valid when statistically significant (P<0.05) and were assessed for fit using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The predictive capacity of the models was evaluated using the area under the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve, and the AUC values were used as an indicator of model performance. Cox & Snell and Nagelkerke R² tests were employed to assess the proportion of variability in the dependent variables explained by the independent variables. Further technical details regarding the statistical methods and models are provided in Supplementary Material S1.

2.2. Qualitative Method

The research followed an interpretivist paradigm, adopting a case study design. The phenomenon under study refers to the perception of telemedicine adoption by workers in a specific context: a private healthcare network in Angola.

2.2.1. Study Population and Sample

The target population for the study included mental health professionals within the private healthcare network. Non-probabilistic sampling was employed, with participants intentionally selected based on critical cases and the following criteria: being a physician or specialist in Psychiatry or Psychology; being an employee within the network in Luanda, male or female, regardless of years of experience in mental health; willingness and interest to participate in the study; and prior experience with telemedicine or lack thereof.

Participants were recruited through telephone contact, and mental health specialists voluntarily consented to participate in the study. A total of nine mental health professionals within the network were invited, of whom six initially agreed to participate, including three psychologists and three psychiatrists. Of these, five interviews were successfully conducted: three psychologists based in Luanda, working at the main facility and other mental health departments, representing 50% of psychologists employed within the network, and two psychiatrists based at the main facility, representing 66.6% of psychiatrists. One interview was canceled due to a language barrier, reducing the final number of valid interviews to five.

2.2.2. Data Collection

Descriptive data collection was conducted using interactive techniques, including structured interviews scheduled according to the availability of psychologists and psychiatrists. Interviews were conducted by telephone for convenience and ease of recording, with participants’ authorization. Each interview was initially estimated to last one hour.

The data collection instrument was a structured questionnaire with open-ended questions prepared by the researchers. Although less flexible and limited to the questionnaire’s items, the structured questionnaire was deemed appropriate for the investigation context and mental health professionals, offering advantages such as standardized questions for all participants, efficiency, consistency, and easier comparison of responses.

Questions included in the interview guide were generally based on the pillars of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [

56,

57]. TAM is a popular theory for assessing and predicting telemedicine acceptance and usage intention. While often used in quantitative components to study perceptions and contributing factors for technology acceptance, its structure was adapted to guide questionnaire development. Accordingly, TAM groups questions into the following: Perceived Usefulness of Telemedicine, Perceived Ease of Use, and Intention to Use, totaling 15 questions (see Supplementary Material S2).

2.2.3. Data Analysis and Processing

Primary data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis. Interview data were transcribed verbatim, with one hour allocated for every ten minutes of recording. Following transcription and participant anonymization, a pre-analysis phase began, involving data familiarization through repeated reading and note-taking with keywords for coding.

In the coding phase, codes were captured based on semantic meaning with potential for latent analytical significance from participants’ excerpts. Codes were assigned according to the predetermined organization of questions and question groups for deductive analysis, as well as based on interesting units identified in the text for potential inductive analysis.

Subsequently, themes and subthemes were defined for the inference phase, refined to ensure internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity. Analysis and result reporting involved data segment extraction and conceptual mapping. All thematic analysis steps were performed using MAXQDA, 2022 qualitative analysis software.

Regarding reflexivity during data collection and analysis, reflective notes were maintained throughout the study to document and analyze thoughts, emotions, and potential biases arising during interviews and data analysis, aiming to recognize and mitigate researchers’ subjectivity.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

To conduct the study within the healthcare network, a request was submitted to the chairman of the management board and the Ethics Committee, which issued favorable opinions for the study, as well as to the management of partner units.

Participation in this study was voluntary and anonymous. Survey participants provided prior consent through the Google Forms questionnaire, acknowledging that the collected data would be used exclusively for scientific purposes. Similarly, interview participants consented to the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and verbally consented to interview recording, knowing the recordings would be transcribed for data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Method

3.1.1. Sample Characterization

From the sampling universe across three regions of Angola, including ten units within the private healthcare network and an estimated 2,721 workers, a participation of n=280 (10%) workers was obtained during February and March 2024. Of these, 0.7% (n=2) declined to participate, and 1.1% (n=3) were excluded due to having less than three months of experience within the network, resulting in a final sample of n=275 workers.

The sample included a slightly higher participation of men (57.1%) than women (42.9%). The 25-34 age group was the most represented, accounting for 52.0% (n=143). Although the professional categories were relatively balanced, physicians stood out slightly, representing 28.7% (n=79). Additionally, 73.8% of participants (n=203) had more than three years of experience within the network (

Appendix A,

Table A1 - Participant Characterization).

Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption

In general, the collected sample highlighted that 83% of participants had never sought mental health professional help in person, while 85.5% reported mental health impacts due to work. Furthermore, 77.8% of healthcare workers within the network agreed that videoconferencing is a useful tool for mental health support.

Regarding videoconferencing, 82.9% of workers had previously used videoconference services, and 95.6% owned suitable devices for conducting them. Although 17.7% did not agree that their internet connection was strong enough for videoconferencing, most professionals preferred smartphones (47.3%) and computers (29.8%) as devices for conducting video consultations.

In terms of psychological or psychiatric support, 89.1% of workers stated they could attend a first video consultation, 88.0% could discuss their problems, 94.9% believed they could receive help for a psychological issue during a video consultation, and 86.9% could accept a medication prescription via video consultation.

Concerning the doctor-patient relationship, 86.9% of workers would feel comfortable doing a mental health video consultation. However, 51.3% were neutral or disagreed that a psychologist or psychiatrist could provide the same quality of care as in-person consultations. Additionally, only 56.0% agreed that video consultations are secure and respect privacy and confidentiality. Furthermore, 53.1% believed video consultations would allow for better personal and professional organization compared to in-person consultations. Full results are provided in

Appendix A (

Table A2).

3.1.2. Comparison of Factors Influencing Telemedicine Adoption Between Headquarters and Partner Units

Regarding health units, the main facility accounted for 40.7% of participants (n=112), representing 6% of the total workforce (n=1941), a smaller proportion compared to partner units, which accounted for 59.3% (n=163), representing 21% of total workers in partner facilities (n=780) (

Appendix A,

Table A1).

Bivariate and multivariate analyses revealed similar results across six variables with statistically significant associations within the professional group (

Appendix A –

Table A3 and

Table A4).

Workers from the main facility were four times more likely to have conducted video consultations than those from partner units [Exp(B) = 4.776; 95% CI = 1.498 - 15.374; p = 0.008] (Q9). Additionally, workers were eight times more likely to have access to materials/devices for conducting video consultations at the main facility compared to partner units [Exp(B) = 8.364; 95% CI = 1.061 - 65.947; p = 0.044] (Q10).

In terms of perceived ease of access to in-person mental health care, workers from the main facility were less likely to report such ease compared to those from partner units [Exp(B) = 0.449; 95% CI = 0.260 - 0.775; p = 0.004].

The perception of being able to speak spontaneously with a mental health professional during a video consultation was lower among workers from the main facility compared to partner units [Exp(B) = 0.446; 95% CI = 0.260 - 0.765; p = 0.003] (Q23). Regarding the perception of security and respect for privacy during video consultations, workers from the main facility reported lower perceptions compared to partner units [Exp(B) = 0.473; 95% CI = 0.284 - 0.790; p = 0.004] (Q26).

Regarding the preferred frequency for conducting video consultations, workers from the main facility were three times more likely to choose the category “Annually, with additional sessions as needed” compared to those from partner units [Exp(B) = 2.726; 95% CI = 1.073 - 6.923; p = 0.035] (Q14,

Appendix A Table A5). Validation results of the regression models presented significant values, with modest predictive capacity for variability in dependent variables (

Appendix A Table A6).

3.1.3. Complementary Results

Complementary results revealed other statistically significant findings relevant to the research (

Appendix A Table A7). Women (93.2%) were three times more likely than men (79.6%) to report that their mental health was impacted by work [Exp(B) = 3.522; 95% CI = 1.557 - 7.970; p = 0.002] (Q15). Gender was significantly associated with the preference for video consultation frequency (p=0.020), where women were twice as likely to choose the category “As requested by workers at any time of the year” [Exp(B) = 2.288; 95% CI = 1.140 - 4.953] (Q14).

Among age extremes, workers aged 18-34 years (91.6%) were 11 times more likely than those aged 50 years or older (50.0%) to report they could discuss their problems during a video consultation [Exp(B) = 11.032; 95% CI = 3.094 - 39.335; p < 0.001] (Q17). Similarly, workers aged 18-34 years (91.0%) reported they could discuss themselves during a video consultation seven times more likely than workers aged 50 years or older (58.3%) [Exp(B) = 7.841; 95% CI = 2.071 - 27.025; p = 0.002] (Q19).

Administrative professionals (94.4%) were three times more likely to feel comfortable conducting a mental health video consultation compared to clinical professionals (84.2%) [Exp(B) = 3.180; 95% CI = 1.083 - 9.337; p = 0.035] (Q8). Furthermore, administrative professionals (84.7%) also were more likely to feel comfortable with the technology for conducting video consultations than clinical professionals (66.0%) [Exp(B) = 2.859; 95% CI = 1.412 - 5.790; p = 0.004] (Q27).

3.2. Qualitative Method

3.2.1. Sample Characterization

From the interviewed mental health professionals (n=5), three were psychologists and two were psychiatrists, with an average age of 47 years and an average of 23 years of work experience within the healthcare network (

Appendix B,

Table A8).

3.2.2. Qualitative Data

The deductive qualitative analysis identified three themes based on the predetermined structure of the interview, related to the perception, ease, and intention of using telemedicine in the form of video consultations. An additional relevant theme emerged outside the interview guide questions, related to perceptions of mental health in Angola as a barrier to telemedicine adoption.

Perceptions of Psychologists and Psychiatrists About Telemedicine

Video consultations were viewed as a practice that could be adapted and structured within the private healthcare network, seen as innovative and beneficial. One interviewee emphasized that the confidential nature of video consultations could enhance adherence and ensure privacy. Among the five interviewees, four already had private experience with video consultations, frequently conducting them with patients from Portuguese-speaking African countries (PALOP), both within and outside Luanda.

Professionals identified several advantages of using video consultations for themselves as providers, including flexibility to consult both at healthcare facilities and at home. The possibility of remote interventions, extended consultation periods, optimized idle time, time management, and the ability to record consultations for later analysis were highlighted as positive aspects.

The interviewees considered that video consultations reduce workers’ exposure, potentially eliminating the fear of attending consultations. Additionally, cost reduction, particularly associated with travel, was noted as an important benefit.

Another identified aspect was the potential to expand care coverage within the healthcare network, promoting self-management of mental health and offering the choice between in-person and telemedicine formats, especially for workers outside the country’s capital (Luanda).

Challenges associated with video consultations included several aspects of technological infrastructure. All interviewees highlighted internet quality as a difficulty that could limit consultation effectiveness. Additionally, the need to protect clinical and administrative data to ensure confidentiality was mentioned.

Other challenges included the quality and access to electronic devices, and interruptions in the patient’s environment. Moreover, lack of familiarity with technology among some users and the need to raise awareness about video consultations were noted as significant obstacles.

Providers perceived video consultations as more demanding than in-person consultations, requiring greater clarity, attention, and the ability to engage the patient. Limitations in observing patients’ non-verbal language were noted. However, it was considered that the dialogic nature of mental health specialties makes clinical assessment more feasible.

Perceptions of Telemedicine Ease of Use

Interviewees did not find video consultations difficult, given their familiarity with videoconferencing tools. They showed a clear openness and willingness to learn new platforms and acquire new skills.

The computer was considered the preferred device, offering greater comfort, enabling observation of the patient’s environment, and avoiding distractions common with mobile phones, making consultations more focused and effective. However, one interviewee also considered mobile phone use as valid.

Professionals recognized the importance of quick training sessions for themselves and staff, focusing on familiarization with software and clarifying the need and advantages of video consultations. However, one interviewee deemed training on software use unnecessary but considered it crucial to clarify the prerequisites for video consultations to align expectations and processes.

Intention to Use Telemedicine

Providers demonstrated a clear intention to adopt telemedicine in the form of video consultations. They perceived that integrating telemedicine into the mental health department’s activities would result in greater efficiency without requiring the creation of a new service. This efficiency would also depend on robust organization of care processes and effective agenda management.

Mental health support via telemedicine was viewed as a way to enhance client satisfaction, improve employee health, and increase efficiency by reducing time spent on administrative tasks. Interviewees concluded that the doctor-patient relationship would not be compromised in video consultations, emphasizing the importance of confidentiality to ensure workers’ adherence. Interactions should adhere to legal, ethical, and deontological standards to ensure security and privacy.

Regarding factors influencing professionals’ decisions to adopt video consultations, interviewees demonstrated a high readiness to provide care and assist patients without access to mental health services. Other influencing factors included the possibility of consulting from home for convenience and extending work schedules.

Financial motivation, linked to increased patient numbers, was considered a factor influencing video consultation adoption, along with clear payment policies and good financial management. One professional emphasized that payment should be based on the time allocated and that the risk of cancellation should be borne by patients for efficient cancellation management.

Implementing telemedicine was perceived as beneficial for supporting mental health within the network, addressing unmet needs, and enabling potential expansion to other regions or networks. Many professionals believed video consultations should have been implemented already. Professionals highlighted several actions necessary for integrating video consultations into the network, such as demonstrating the losses from not integrating telemedicine to support workers’ mental health, preparing and educating workers on its importance, and formalizing a robust proposal for the management board.

Additionally, other actions explored by professionals for implementing video consultations included creating a user-friendly platform, promoting and publicizing the service, training data managers, and efficient service management. Investment in technological infrastructure was seen as a priority to ensure the suitability of video consultation practices.

The ideal frequency for video consultations was perceived as multifactorial, depending on various factors such as specialist availability, workload distribution, patient demand, and clinical conditions.

Perceptions of Mental Health in Angola

General perceptions of mental health in Angola may influence telemedicine adoption. Professionals noted that there is no culture of seeking help, with mental health being poorly recognized by the general population, which could act as a barrier to adopting video consultations for mental health support.

In the hospital context, mental health was perceived by interviewees as an element directly influencing workers’ functionality. Professionals emphasized that a hospital worker without mental health would be unable to provide adequate care, potentially resulting in medical errors or presenteeism, compromising care quality highlighting the need for mental health support for professionals.

However, another interviewee noted that beyond the lack of recognition of mental health needs, fear of criticism prevents professionals from seeking mental health care. This perception could affect adherence to video consultations.

Video consultations could impact workers’ productivity. One professional suggested that a mentally healthy worker is more productive, and failing to invest in workers’ mental health could lead to potential institutional losses. All relevant interview segments are provided in Supplementary Material S2.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Quantitative Results

In this study, the main factors influencing the predisposition to adopt telemedicine as a tool to support mental health among workers in the private healthcare network are workers’ mental health status, previous consultation experiences, perceptions of access to in-person consultations, perceptions of video consultations, and the doctor-patient relationship. These factors are influenced by worker gender, healthcare unit, age group, and professional category.

Most workers had never sought help from a mental health professional in person, despite reporting work-related mental health impacts. Literature identifies various barriers to seeking mental health care, such as fear of discrimination, perceived lack of need for mental health care, confidentiality concerns, and potential career impacts [

58,

59,

60].

Workers at the main facility reported less ease of access to in-person mental health consultations compared to those from partner units, potentially due to the current requirement for preliminary medical evaluation. This highlights the need for a specific mental health support program within the network.

In this study, women were more likely to report mental health impacts compared to men. This finding aligns with literature indicating greater mental health impacts among female healthcare professionals during the pandemic (5,15,61). Although this study did not assess the mental health status or its impacts among professionals, this information is critical for tailoring interventions within the healthcare network, given women’s potentially differing needs.

Younger workers (18-34 years) were more likely to discuss themselves during a video consultation compared to those aged 50 years or older, suggesting that younger individuals are more comfortable with technology. Strategies to engage older workers should be developed.

Overall, workers had positive perceptions of mental health support via video consultations. They believed they could discuss their problems, receive help for psychological issues, accept a medication prescription, and have a first video consultation. These findings demonstrate professionals’ openness to conducting mental health video consultations. However, half of the professionals were neutral or disagreed that psychologists or psychiatrists could provide the same quality of care through video consultations as in-person consultations, indicating concerns about the efficacy of this care format.

Although professionals perceived that conducting mental health video consultations could be comfortable, concerns regarding security, privacy, and confidentiality remained. Similar concerns were reflected in the study by Cormi et al. (2021) [

62], conducted in a different geographical and organizational context.

The findings of this study suggest that a telemedicine implementation model must consider factors influencing adoption and significant differences between the main facility and partner units. It is essential to sensitize workers and demonstrate the importance of video consultations

Administrative staff, compared to clinical staff, were more likely to feel comfortable conducting mental health video consultations if experiencing psychological issues and felt more at ease with technology. Cormi et al. (2021) [

62] identified that clinical staff perceived remote support less favorably, aligning with this study’s findings. These results suggest that administrative workers within the network may be more receptive to remote mental health support, which highlights the need to involve clinical professionals.

Video consultations in mental health should meet technological standards outlined by the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) [

63]. Challenges such as inadequate home internet and limited access to devices, particularly in partner units, were identified. Mitigation strategies include pre-assessing home conditions, using audio calls during interruptions, or equipping health units with dedicated teleconsultation rooms [

63].

The preference for mobile phones as the primary device for video consultations was notable and aligns with a study conducted in a private institution in Kenya [

64], likely due to the accessibility and portability of these devices. Workers also expressed a preference for conducting video consultations on an annual basis, with additional sessions as needed. These preferences indicate a demand for structured and flexible telemedicine programs tailored to individual needs and organizational contexts.

4.2. Discussion of Qualitative Results

This study aimed to explore the perceptions of mental health professionals regarding telemedicine and its adoption as a support tool for the mental health of workers within a private healthcare network. The findings revealed that several factors influence the adoption of telemedicine.

4.2.1. Perceptions of Psychologists and Psychiatrists on the Use of Telemedicine

The advantages of telemedicine identified in this study align with the literature, particularly in improving access to care for individuals facing mobility limitations [

65]. Telemedicine has also been shown to enhance patient engagement, satisfaction, and adherence, while promoting continuity in the therapeutic process [

66,

67]. Additionally, it offers greater comfort and flexibility compared to in-person consultations [

68,

69].

Professionals in this study viewed telemedicine as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for in-person care. This perspective supports a hybrid care model, as highlighted by Moeller et al. (2022) [

67] and Uscher-Pines et al. (2022) [

66], where video consultations expand care options and improve overall quality. However, prior experience with telemedicine appears to influence perceptions, as evidenced by Hoffmann et al. (2020) [

70], where professionals with no prior experience viewed telemedicine as suitable only for initial consultations or diagnostics.

Confidentiality and privacy were identified as key advantages of telemedicine, particularly in reducing exposure to coworkers. However, professionals acknowledged challenges related to maintaining privacy in home environments, an issue also noted in other studies (64,69,71). These findings highlight the need to inform employees of the basic principles for conducting consultations to minimize these challenges and need for designated teleconsultation rooms in healthcare facilities to ensure safety and comfort, as recommended by the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) [

63,

72].

Telemedicine was also perceived as effective in supporting mental health self-management, enabling continuity in care without compromising the doctor-patient relationship. These findings align with studies from South Africa, where telemedicine facilitated both brief interventions and longer therapeutic sessions [

71]. Additionally, telemedicine was noted to increase patients’ comfort in discussing sensitive topics [

73], and studies suggest that therapeutic relationships can be maintained effectively in virtual formats [

74].

Regarding the challenges, one of the most central issues was the reduced ability to observe patients’ non-verbal language, a concern consistent with the literature (64,65,69,70,73,75). However, “empathic accuracy” (the ability to perceive how the patient feels) and the “therapeutic alliance” (the establishment of a trustworthy and collaborative relationship) are not significantly affected in the telepsychiatry format [

74] which justifies the development of strategies to focus on verbal language during the therapeutic process to establish a satisfactory doctor-patient relationship.

Professionals also highlighted the increased mental effort required during video consultations, consistent with findings from Goldschmidt et al. (2021) [

71] and Buckman et al. (2021) [

68]. The telemedicine model, while convenient, can be more exhausting than in-person care, underscoring the need for adequate workload management.

Technical challenges identified in this study, including the need for secure, user-friendly platforms and data protection, align with findings from other studies (65,67,69). The WPA [

63,

76] emphasizes prerequisites such as interoperability, compatibility, patient safety, and data security, which must be addressed to ensure successful telemedicine implementation within the network.

Internet quality was identified as a challenge for delivering care via video consultations, especially in peripheral regions of Angola. This challenge was also identified in Kenya [

64], and South Africa, where access and costs hindered internet use, particularly in underserved populations [

71]. Even in London, the quality of the internet connection and the lack of suitable devices were barriers highlighted by Buckman et al. 2021 [

68], despite being a completely different context. Utilizing available resources and adapting specific rooms in partner units could mitigate challenges faced by workers, such as connectivity issues or inadequate devices.

4.2.2. Perceptions of the Ease of Using Telemedicine

Professionals perceived video conferencing tools as easy to use, which positively influenced their high intention to use them. In the study by Knott et al. 2020 [

72], professionals who considered video conferencing technologies difficult demonstrated a greater tendency to highlight limitations rather than benefits, adopting a more resistant attitude toward telemedicine compared to those who found the tools easy to use. This finding reinforces the conclusion that the perception of the ease of video consultations can influence professionals’ adoption.

The computer was the preferred device for most professionals due to its broader visual coverage and lower risk of interruptions from notifications, unlike mobile phones. In contrast, in Kenya, mobile phones were preferred, possibly due to the experience with more user-friendly platforms [

64]. Additionally, the ability to study the patient’s home environment, providing additional information, is an advantage identified in agreement with the literature (65,75,77).

Professionals emphasized the importance of training, both for themselves and for employees receiving care via telemedicine. Training is widely supported in the literature as essential for developing technical competence and ensuring effective use of telemedicine technologies [

76]. A lack of exposure to telemedicine during undergraduate education may create barriers, as noted by Knott et al. (2020) [

72]. However, well-designed training programs can address these challenges, shaping positive attitudes toward telemedicine adoption.

In the literature, the perceptions of training activities are explored as opportunities for professionals to familiarize themselves with video consultations [

70] as well as to optimize care through training focused on resolving issues that may arise during sessions, video tutorials to learn the functions of video platforms, and practical usage simulations [

68]. In the study by Lipschitz et al. 2022 [

69], professionals identified the need to receive a best practices manual that would provide technical, legal, and ethical standards for using telemedicine. Conversely, in the study by Moeller et al. 2022 [

67], it was concluded that in scenarios of high workload, training may be seen as a burden and negatively influence the perception of telemedicine adoption. These findings reinforce the importance of training activities in telemedicine for both providers and employees within the healthcare network.

Training opportunities, as highlighted in the literature, should include tutorials for platform functionality, simulations for practical application, and troubleshooting strategies [

68,

70]. Lipschitz et al. (2022) [

69] noted the value of best practice manuals outlining technical, legal, and ethical standards. However, Moeller et al. (2022) [

67] emphasized that in scenarios of high workload, training may be perceived as a burden, potentially negatively influencing professionals’ attitudes toward telemedicine adoption. These findings reinforce the importance of tailoring training programs to the specific needs of healthcare professionals, ensuring both providers and employees can fully benefit from telemedicine.

4.2.3. Intention to Use Telemedicine

All professionals in this study demonstrated a strong intention to conduct video consultations within the healthcare network, with key factors influencing this decision, such as the feasibility of the project. Uscher-Pines et al. (2020) [

65] similarly observed that while professionals utilized video consultations during the pandemic, many preferred returning to in-person care due to uncertainties about the long-term viability of telemedicine. This finding underscores the importance of institutional strategies to ensure the sustainability of telemedicine, which is critical for professional adherence.

Financial policies were another significant factor influencing adoption. In the USA, unclear finance policies created perceptions that hindered the continuity of telemedicine [

65]. Similarly, Lipschitz et al. (2022) [

69] identified funding barriers imposed by insurers as a challenge. In Denmark, professionals received financial incentives to encourage the use of video consultations, but these alone were insufficient for long-term adoption [

67]. Some professionals in this study suggested that payment should still apply if patients fail to attend consultations, a view echoed in a German study [

70], highlighting the importance of financial incentives for adoption and continuity.

Institutional support also plays a crucial role in professionals’ willingness to adopt telemedicine. Effective service management, including hospital and ICT support, along with immediate technical assistance during video consultations, significantly impacts adoption, as highlighted in previous studies [

67,

75].

Professionals perceive the ideal frequency of video consultations as multifactorial, guided by the patient’s clinical condition, with a higher frequency in psychology than in psychiatry. In the literature, frequency is also viewed as multifactorial, considering that not all clinical cases are suitable for telemedicine. However, removing access barriers generally results in more frequent and patient-centered sessions (66,67,69,75).

Professionals emphasized that video consultations must uphold privacy, ethical, and deontological standards, supported by informed consent. This aligns with the “Telepsychiatry Global Guidelines,” which underline the importance of privacy, confidentiality, and ethical compliance in telepsychiatry [

63,

76].

4.2.4. Perceptions of Mental Health in Angola

In Angola, the social constructs surrounding mental health represent, in part, a significant barrier to accessing mental health care, which can negatively impact the adoption of video consultations. In the context of telepsychiatry, it is essential that mental health professionals provide culturally competent care [

63], tailored to the country’s cultural diversity.

In the present study, it was identified that fear of criticism from colleagues is a factor that discourages employees from seeking mental health care. Although there are circuits in place at the main facility, it is necessary to expand coverage to partner units. Telemedicine was considered an effective solution in this context.

Respondents indicated that mental disorders directly affect the productivity of healthcare professionals, leading to presenteeism, medical errors, and financial losses for the Angolan healthcare network. Despite the barriers to adopting telemedicine, they highlighted essential actions for its implementation in supporting mental health and expressed an optimistic perspective on the benefits and the crucial role of telemedicine in the future.

Raising workers’ awareness about the importance of self-management of their mental health and its implications across various domains of their lives is a crucial step in managing network most valuable asset: its human capital.

4.3. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its observational, cross-sectional, and descriptive nature does not allow causality inference. Additionally, its external validity is limited since results were based on the private healthcare context in Angola and may not generalize to public or international healthcare settings. While offering valuable insights for low- to middle-income countries, findings should be cautiously compared.

Another limitation concerns the consideration of costs as a factor influencing the adoption of telemedicine. In the network, the costs associated with workers’ healthcare are subsidized, with a relatively low percentage. This aspect was not the subject of study.

The topic of telemedicine as a support tool for the mental health of healthcare professionals represents a gap in the literature, with no previous studies available, which limits the discussion of the results within a broader body of literature.

Structured questionnaires can limit data collection since their standardized and predetermined nature restricts the exploration of unexpected insights. Finally, only telemedicine in the form of video consultations was explored; no analysis was conducted on the format of audio calls.

4.4. Telemedicine-Based Mental Health Model and Operational Circuit

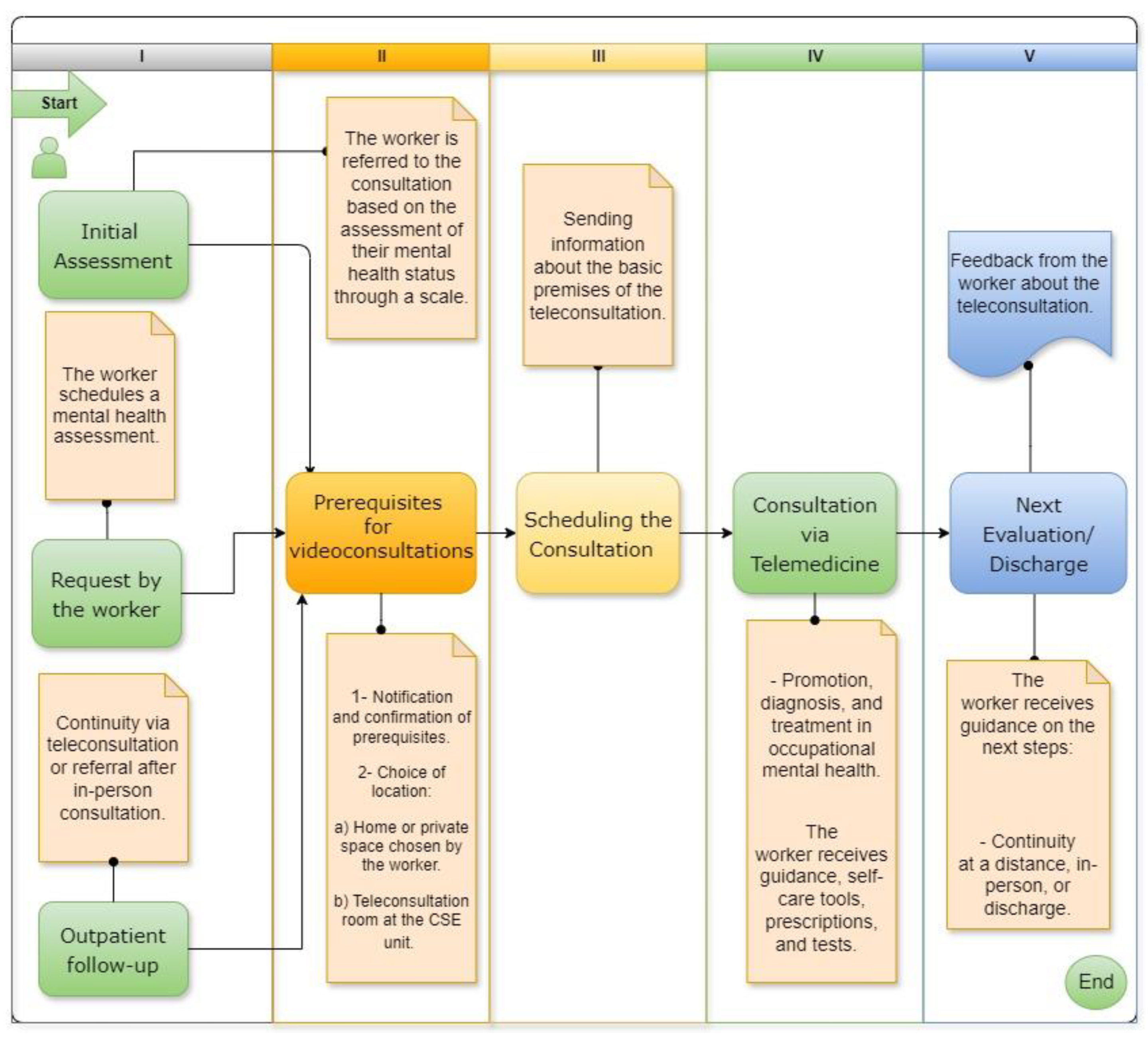

Based on the results obtained in the study, six pillars were developed for a telemedicine model tailored to the perceptions of healthcare workers, each with its own objectives and strategies. These pillars are: Monitoring occupational well-being; Network access and coverage; Privacy and confidentiality; Quality and effectiveness of care; Training and awareness; and Technical and logistical support (

Figure 1).

Additionally, an operational circuit with five stages was created (

Figure 2). The initial stages, corresponding to the entry point and confirmation of prerequisites for video consultations, can be conducted through a more conventional triage process or by utilizing artificial intelligence in an online portal to better guide workers to video consultations. Following this, the worker schedules the video consultation and receives information about the basic premises of teleconsultations. During the video consultation, activities such as promotion, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and outpatient follow-up for occupational mental health are conducted. Finally, the worker provides a report on the teleconsultation.

5. Conclusions

This study identified and explored the key factors influencing the predisposition to adopt telemedicine as a tool to support the mental health of workers within a private healthcare network in Angola.

The mixed-methods approach included questionnaires administered to workers (n=275) and structured interviews with mental health professionals (n=5). The findings indicate that mental health policies in the network should focus on the well-being of its human capital. The impact on mental health and the low demand for care, in a context of scarcity of mental health professionals, underscore the need for implementing networked resources. Telemedicine may emerge as a viable solution for promoting, preventing, diagnosing, treating, and providing outpatient follow-up in a hybrid care delivery model.

The majority of workers demonstrated a positive perception of telemedicine, although administrative professionals felt more comfortable with its use compared to clinical professionals. Therefore, mental health interventions within the network should be culturally adapted and adjusted for gender, age, professional category, and healthcare unit differences.

The study highlighted the necessity of creating policies regarding privacy, confidentiality, and data protection, particularly in telemedicine, and fostering an organizational culture that normalizes mental health through awareness-raising strategies for professionals.

Telemedicine was seen as a tool that facilitates self-management of mental health, offers continuous support, and allows broader coverage. However, its implementation requires overcoming technological challenges such as internet quality, the use of appropriate equipment, and the need for a user-friendly platform.

In this study, various factors influence the adoption of telemedicine by workers; for providers, the key factors include ease of technology use, project feasibility, management support, payment policies, and the compliance of consultations with legal, ethical, and deontological standards.

Strengthening the mental well-being of professionals can lead to benefits not only for patients but also for the institution, resulting in increased productivity, satisfaction, quality of care, and reduced absenteeism, presenteeism, turnover, and medical errors.

The results of this study provide a solid foundation for the development of policies that integrate digital transformation into the mental health support program for workers. This study makes a significant contribution to addressing the gap in the literature on the mental health of healthcare professionals in Africa and the development of mental health strategies.

Further studies are needed to assess the psychosocial risk of professionals in the network and analyze the actual mental health status of workers, identifying the most frequent mental disorders and their predictors, such as gender, age, years of service, healthcare unit, and professional category.

Telemedicine can be a viable tool to support the mental health of workers. However, it is first necessary to establish the foundations of occupational mental health within the network and then develop a pilot project that incorporates digital transformation as a way to generate value.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by E.S and T.M. contributed to all processes, reviewing the cultural adaptation of the data collection instrument, critical analysis of the results, discussion, and the telemedicine model. The first draft of the manuscript was written by E.S., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. T.M. provided critical edits. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following approval from the chairman of the management board and the Ethics Committee, which issued favorable opinions for the study. Additionally, permission was obtained from the management of partner units. All participants provided signed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and verbal consent was obtained for the recording of interviews. These measures ensured full compliance with ethical guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in this study was voluntary and anonymous. Survey participants provided prior consent through the Google Forms questionnaire, acknowledging that the collected data would be used exclusively for scientific purposes. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, a signed consent form was obtained from all interview participants. Additionally, for the interviews, verbal consent was specifically provided for the recording of the sessions, with the understanding that the recordings would be transcribed for data analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the workers at Sagrada Esperança Clinic who participated in this study, as well as all the members of the clinic’s administrative chain who authorized and contributed to making this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Characterization of the Participants.

Table A1.

Characterization of the Participants.

| Sample Characterization (n=275) |

Category |

Count |

% of Column N |

| Participant Gender |

Male |

157 |

57.1% |

| Female |

118 |

42.9% |

| Subtotal |

275 |

100% |

| Age Group |

18–24 years |

12 |

4.4% |

| 25–34 years |

143 |

52.0% |

| 35–49 years |

108 |

39.3% |

| 50–60 years |

8 |

2.9% |

| Over 60 years |

4 |

1.5% |

| Subtotal |

275 |

100% |

| Participant Professional Category |

Physician |

79 |

28.7% |

| Nurse |

63 |

22.9% |

| Technician |

61 |

22.2% |

| Receptionists and Administrative Staff |

72 |

26.2% |

| Subtotal |

275 |

100% |

| Work Experience in the network |

Less than 1 year |

15 |

5.5% |

| 1 to 3 years |

57 |

20.7% |

| Over 3 years |

203 |

73.8% |

| Subtotal |

275 |

100% |

| Healthcare Unit |

Main Facility |

112 |

40.7% |

| Partner units |

163 |

59.3% |

| Subtotal |

275 |

100% |

Table A2.

Factors Influencing the Adoption of Telemedicine.

Table A2.

Factors Influencing the Adoption of Telemedicine.

| Survey Results: “Telepsy For Everyone” Applied in a Healthcare Network in Angola, 2024 |

Category |

Count |

% of Column N |

| Q6. Have you ever sought help from a mental health professional for psychological or psychiatric reasons, in-person for yourself? |

Yes |

45 |

16.4% |

| |

No |

230 |

83.6% |

| Q7. Have you ever used services like Zoom, Skype, Teams, WhatsApp, Messenger, among others, for videoconferencing? |

Yes |

228 |

82.9% |

| |

No |

47 |

17.1% |

| Q8. If you had a psychological problem, would you feel comfortable doing a videoconference with a mental health professional? |

Yes |

239 |

86.9% |

| |

No |

36 |

13.1% |

| Q9. Have you ever had a videoconference with a health professional as the patient? |

Yes |

16 |

5.8% |

| |

No |

259 |

94.2% |

| Q10. Do you have a device that allows you to conduct a videoconference (smartphone, computer, tablet, etc.)? |

Yes |

263 |

95.6% |

| |

No |

12 |

4.4% |

| Q11. Is your internet connection strong enough to conduct a videoconference (on your phone or at home)? |

Yes |

228 |

82.9% |

| |

No |

47 |

17.1% |

| Q12. Do you have a space where you can be calm and talk freely for at least 30 minutes during a videoconference? |

Yes |

260 |

94.5% |

| |

No |

15 |

5.5% |

| Q13. Which of the following devices would you preferably choose to conduct videoconferences? (Please check your preferred options) |

Smartphone |

130 |

47.3% |

| |

Computer |

82 |

29.8% |

| |

Computer, Tablet |

2 |

0.7% |

| |

Tablet |

19 |

6.9% |

| |

Smartphone, Tablet |

3 |

1.1% |

| |

Smartphone, Computer |

27 |

9.8% |

| |

Smartphone, Computer,Tablet |

12 |

4.4% |

| Q14. What frequency do you consider appropriate for psychology/psychiatry videoconferences at your unit? (Please select only one option) |

Annually, during workers’ health check-ups |

57 |

20.7% |

| |

Annually, with additional sessions as needed |

37 |

13.5% |

| |

Quarterly |

36 |

13.1% |

| |

Semiannually |

34 |

12.4% |

| |

As requested by workers, at any time of the year |

111 |

40.4% |

| Q15. Have you ever felt an impact on your mental health due to your work? (Including stress, insomnia, anxiety, burnout, etc.) |

Yes |

235 |

85.5% |

| |

No |

40 |

14.5% |

| Q16. If faced with a psychological problem, I think videoconferencing would be: |

Easier than an in-person consultation |

104 |

37.8% |

| |

Equivalent to an in-person consultation |

86 |

31.3% |

| |

More difficult than an in-person consultation |

52 |

18.9% |

| |

I would not do a videoconference for a psychological problem |

33 |

12.0% |

| Q17. During a videoconference, I could talk about my problems: |

Yes, I could |

242 |

88.0% |

| |

No, I could not |

33 |

12.0% |

| Q18. During a videoconference, I could do a first consultation: |

Yes, I could |

245 |

89.1% |

| |

No, I could not |

30 |

10.9% |

| Q19. During a videoconference, I could talk about myself: |

Yes, I could |

244 |

88.7% |

| |

No, I could not |

31 |

11.3% |

| Q20. During a videoconference, I could receive help for a psychological problem: |

Yes, I could |

261 |

94.9% |

| |

No, I could not |

14 |

5.1% |

| Q21. During a videoconference, I could accept a medication prescription: |

Yes, I could |

239 |

86.9% |

| |

No, I could not |

36 |

13.1% |

| Q22. I have easy access to in-person psychological and/or psychiatric care at the clinic: (Indicate your level of agreement with this statement) |

Agree |

95 |

34.5% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

180 |

65.5% |

| Q23. During a videoconference, I think I can spontaneously talk to my psychiatrist or psychologist about what worries me, even if they don’t ask: |

Agree |

186 |

67.6% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

89 |

32.4% |

| Q24. With videoconferencing, I think my psychiatrist or psychologist is capable of offering me the same quality of care they would offer in-person: |

Agree |

134 |

48.7% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

141 |

51.3% |

| Q25. During a videoconference, I think the doctor-patient relationship with a psychiatrist or psychologist would be satisfactory for me: |

Agree |

167 |

60.7% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

108 |

39.3% |

| Q26. Videoconferences are safe and respect my privacy and medical confidentiality: |

Agree |

154 |

56.0% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

121 |

44.0% |

| Q27. I feel sufficiently comfortable with the technology to do a videoconference: |

Agree |

195 |

70.9% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

80 |

29.1% |

| Q28. Considering my personal and professional limitations, a psychiatry or psychology videoconference would allow me to organize myself more easily compared to an in-person consultation: |

Agree |

146 |

53.1% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

129 |

46.9% |

| Q29. I think psychiatry videoconferencing is a useful tool for addressing workers’ mental health in my unit: |

Agree |

214 |

77.8% |

| |

Disagree/Neutral |

61 |

22.2% |

Table A3.

Bivariate Analysis: Chi-Square with Risk Estimate.

Table A3.

Bivariate Analysis: Chi-Square with Risk Estimate.

| Question No. |

Category |

Relative Frequency (Yes) |

X² (Pearson’s Chi-Square) |

df |

P-Value |

OR |

95% CI |

| Q9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

10.7% |

8.266 |

1 |

0.004 |

4.770 |

[1.497 - 15.199] |

| |

Partner units |

2.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

99.1% |

5.454 |

1 |

0.02 |

8.033 |

[1.022 - 63.132] |

| |

Partner units |

93.3% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

23,2% (*) |

18.291 |

4 |

0.001 |

N/A |

N/A |

| |

Partner units |

6,7% (*) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

26.8% |

5.032 |

1 |

0.025 |

0.552 |

[0.327 - 0.930] |

| |

Partner units |

39.9% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

58.9% |

6.545 |

1 |

0.011 |

0.514 |

[0.308 - 0.859] |

| |

Partner units |

73.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

47.3% |

5.776 |

1 |

0.016 |

0.551 |

[0.339 - 0.898] |

| |

Partner units |

62.0% |

|

|

|

|

|

Table A4.

Multivariate Analysis: Binary Logistic Regression.

Table A4.

Multivariate Analysis: Binary Logistic Regression.

| Question No. |

Category |

Coefficient B |

S.E |

Wald |

Sig |

Exp(B) |

95% CI (Exp(B) |

| Q9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

1.156 |

0.59 |

6.982 |

0.008 |

4.776 |

[1,498 - 15,374] |

| |

Constant |

-3.670 |

0.55 |

44.641 |

<0,001 |

0.025 |

|

| Q10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

2.124 |

1.05 |

4.064 |

0.044 |

8.364 |

[1,061 - 65,947] |

| |

Constant |

2.892 |

0.47 |

41.171 |

<0,001 |

19.723 |

|

| Q22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

-0.800 |

0.28 |

8.263 |

0.004 |

0.449 |

[0,260 - 0,775] |

| |

Work experience >3 years |

1.015 |

0.33 |

9.44 |

0.002 |

2.758 |

[1,444 - 5,269] |

| |

Constant |

-1.105 |

0.29 |

14.69 |

<0,001 |

0.331 |

|

| Q23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

-0.807 |

0.28 |

8.606 |

0.003 |

0.446 |

[0,260 - 0,765] |

| |

Work experience >3 years |

0.619 |

0.3 |

4.17 |

0.041 |

1.857 |

[1,025 - 3,363] |

| |

Constant |

0.640 |

0.25 |

6.356 |

0.012 |

1.896 |

|

| Q26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Main facility |

-0.748 |

0.26 |

8.213 |

0.004 |

0.473 |

[0,284 - 0,790] |

| |

Work experience >3 years |

0.686 |

0.29 |

5.572 |

0.018 |

1.985 |

[1,123 - 3,507] |

| |

Constant |

0.049 |

0.25 |

0.04 |

0.841 |

1.05 |

|

Table A5.

Q14 Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis: Chi-Square and Multinomial Logistic Regression.

Table A5.

Q14 Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis: Chi-Square and Multinomial Logistic Regression.

| Question No. 14 |

Category |

Variables |

Relative Frequency |

Coefficient B |

S.E |

Wald |

Sig |

Exp (B) |

95% CI of Exp(B) |

Model Fit Sig (Final) |

Pearson |

Deviation |

Nagelkerke R² (Sig) |

ROC Curve (AUC) |

| |

Healthcare Unit |

Main facility |

23.2% |

1.003 |

0.47 |

4.45 |

0.035 |

2.726 |

[1.073 - 6.923] |

0.006 |

0.511 |

0.196 |

0.159 |

0.491 |

| Option 2* |

|

Partner units |

6.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Gender |

Female |

18.6% |

1.191 |

0.46 |

6.67 |

0.010 |

3.292 |

[1.333 - 8.133] |

|

|

|

|

0.594 |

| |

|

Male |

9.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Option 5** |

Gender |

Female |

44.9% |

0.828 |

0.36 |

5.42 |

0.020 |

2.288 |

[1.140 - 4.593] |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Male |

36.9% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A6.

Validation Results of the Regression Models.

Table A6.

Validation Results of the Regression Models.

| Question No. |

Omnibus Test (Model Chi-Square) |

Omnibus Test (Model Sig) |

Nagelkerke R² (Sig) |

Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (Sig) |

Overall Accuracy |

ROC Curve (AUC) |

| Q8 Clinicians vs. Administrative Staff |

5.887 |

0.053 |

0.039 |

0.397 |

86.9% |

0.587 |

| Q9 Healthcare Unit |

8.235 |

0.016 |

0.082 |

0.899 |

94.2% |

0.318 |

| Q10 Healthcare Unit |

8.129 |

0.017 |

0.097 |

0.726 |

95.6% |

0.331 |

| Q15 Gender |

10.83 |

0.004 |

0.068 |

0.112 |

85.5% |

0.366 |

| Q17 Age Group |

12.43 |

0.002 |

0.141 |

0.964 |

88.6% |

0.374 |

| Q18 Gender |

5.925 |

0.052 |

0.043 |

0.341 |

81.1% |

0.596 |

| Q19 Age Group |

8.465 |

0.015 |

0.097 |

0.658 |

88.6% |

0.411 |

| Q22 |

15.483 |

<0,001 |

0.076 |

0.205 |

65.5% |

|

| Healthcare Unit |

|

|

|

|

|

0.57 |

| Work Experience >3 years |

|

|

|

|

|

0.429 |

| Q23 |

10.64 |

0.005 |

0.053 |

0.909 |

67.6% |

|

| Healthcare Unit |

|

|

|

|

|

0.581 |

| Work Experience >3 years |

|

|

|

|

|

0.461 |

| Q26 |

11.427 |

0.003 |

0.055 |

0.902 |

58.2% |

|

| Healthcare Unit |

|

|

|

|

|

0.572 |

| Work Experience >3 years |

|

|

|

|

|

0.453 |

| Q27 Clinicians vs. Administrative Staff |

10.683 |

0.005 |

0.054 |

0.351 |

70.9% |

0.588 |

Table A7.

Complementary Analysis: Chi-Square and Binary Logistic Regression.

Table A7.

Complementary Analysis: Chi-Square and Binary Logistic Regression.

| Question No. |

Category |

Relative Frequency (Yes) |

X² (Pearson's Chi-Square) |

df |

P-Value of the Chi-Square |

Regression Exp(B) |

95% CI (Exp(B)) |

| Q8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Professional Group: Administrative |

94.4% |

4.868 |

1 |

0.035 |

3.180 |

1.083-9.337 |

| |

Professional Group: Clinical |

84.2% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Female |

93.2% |

10.028 |

1 |

0.002 |

3.522 |

1.557 - 7.970 |

| |

Male |

79.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q17 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Age Group: 18-34 |

91.6% |

19.128 |

1 |

<0,001 |

11.032 |

3.094 - 39.335 |

| |

Age Group: ≥ 50 |

50.0% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Male |

92.4% |

4.015 |

1 |

0.045 |

2.135 |

1.003 - 4.714 |

| |

Female |

84.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Age Group: 18-34 |

91.0% |

11.764 |

1 |

0.002 |

7.841 |

2.071 - 27.025 |

| |

Age Group: ≥ 50 |

58.3% |

|

|

|

|

|

| Q27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Professional Group: Administrative |

84.7% |

9.022 |

1 |

0.004 |

2.859 |

1.412 - 5.790 |

| |

Professional Group: Clinical |

66.0% |

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

Table A8.

Characterization of Interview Participants.

Table A8.

Characterization of Interview Participants.

| Participant |

Specialty |

Average Age |

Average Work Experience in the Network |

| 1st Interviewee |

Psychologist |

|

|

| 2nd Interviewee |

Psychiatrist |

|

|

| 3rd Interviewee |

Psychiatrist |

42.1 |

23 years |

| 4th Interviewee |

Psychologist |

|

|

| 5th Interviewee |

Psychologist |

|

|

References

- Galderisi, S.; Heinz, A.; Kastrup, M.; Beezhold, J.; Sartorius, N. Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry [Internet]. 2015, 14, 231–232, Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4471980/ [cited 2023 Oct 5]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: New propositions. Organizational Psychology Review. 2023, 13, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.E.C.; Ling, M.; Boyd, L.; Olsson, C.; Sheen, J. The prevalence of probable mental health disorders among hospital healthcare workers during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadri, N.S.; Sultan, A.; Ali, S.I.; Yousif, M.; Moussa, A.; Abdo, E.F.; et al. COVID-19 in Africa: Survey Analysis of Impact on Health-Care Workers. Am J Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 2021, 104, 2169–2175, Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33886500/ [cited 2024 Mar 2]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oamen, B.R.; Jordan, P.; Iwu-Jaja, C. The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers in Africa: a scoping review. PAMJ-OH 2023, 12, 1–8, Available from: https://www.one-health.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/12/7/full [cited 2024 Apr 6]. [Google Scholar]

- Olashore, A.; Akanni, O.; Fela-Thomas, A.; Khutsafalo, K. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on health-care workers in African Countries: A systematic review. Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguga, F.; Kwobah, E.K.; Mwangi, A.; Patel, K.; Mwogi, T.; Kiptoo, R.; et al. Harmful Alcohol Use Among Healthcare Workers at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Kenya. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirigia, J.M.; Barry, S.P. Health challenges in Africa and the way forward. In: Efficiency of Health System Units in Africa: A Data Envelopment Analysis. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleribe, O.O.; Momoh, J.; Uzochukwu, B.S.C.; Mbofana, F.; Adebiyi, A.; Barbera, T.; et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int J Gen Med. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchasi, G.; Okonji, O.C.; Jena, R.; Ahmad, S.; Soomro, U.; Kolawole, B.O.; et al. Challenges faced by African healthcare workers during the third wave of the pandemic. Health Sci Rep [Internet]. 2022, 5. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9576111/ [cited 2024 Mar 2]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moitra, M.; Rahman, M.; Collins, P.Y.; Gohar, F.; Weaver, M.; Kinuthia, J.; et al. Mental Health Consequences for Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review to Draw Lessons for LMICs. Front Psychiatry. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olude, O.A.; Odeyemi, K.; Kanma-Okafor, O.J.; Badru, O.A.; Bashir, S.A.; Olusegun, J.O.; et al. Mental health status of doctors and nurses in a Nigerian tertiary hospital: A COVID-19 experience. South African Journal of Psychiatry. 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, M.C.; Heunis, J.C.; Kigozi, N.G. Post-Traumatic Stress and Coping Strategies of South African Nurses during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021, 18. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8345364/ [cited 2024 Apr 7]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]