Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Job Crafting and Work Withdrawal Behaviors as a Result of Digitization-Oriented Job Demands

2.2. Resource Enrichment Pathways - The Mediating Role of Thriving at Work

2.3. Resource Loss Pathways - The Mediating Role of Workplace Anxiety

2.4. The Moderating Role of the Regulatory Focus

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

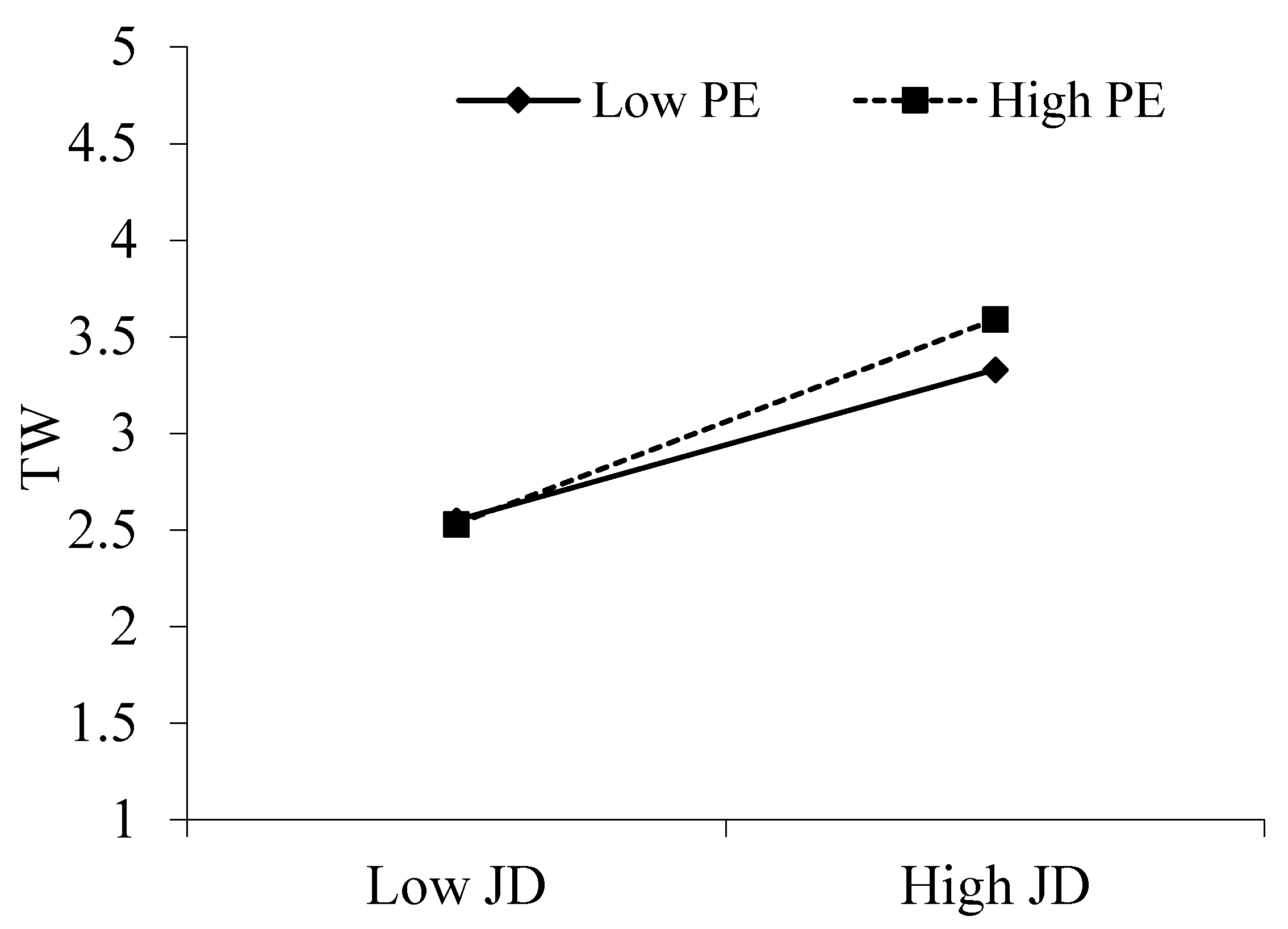

| Moderator: PO | JD→TW→JC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% Boot CI | |

| Indirect effect | 0.07** | 0.02 | [0.03, 0.15] |

| Direct effect | 0.41*** | 0.04 | [0.33, 0.48] |

| High(+PE) | 0.10*** | 0.03 | [0.04, 0.15] |

| Low(-PE) | 0.05** | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.09] |

| Index | 0.02** | 0.01 | [0.01, 0.04] |

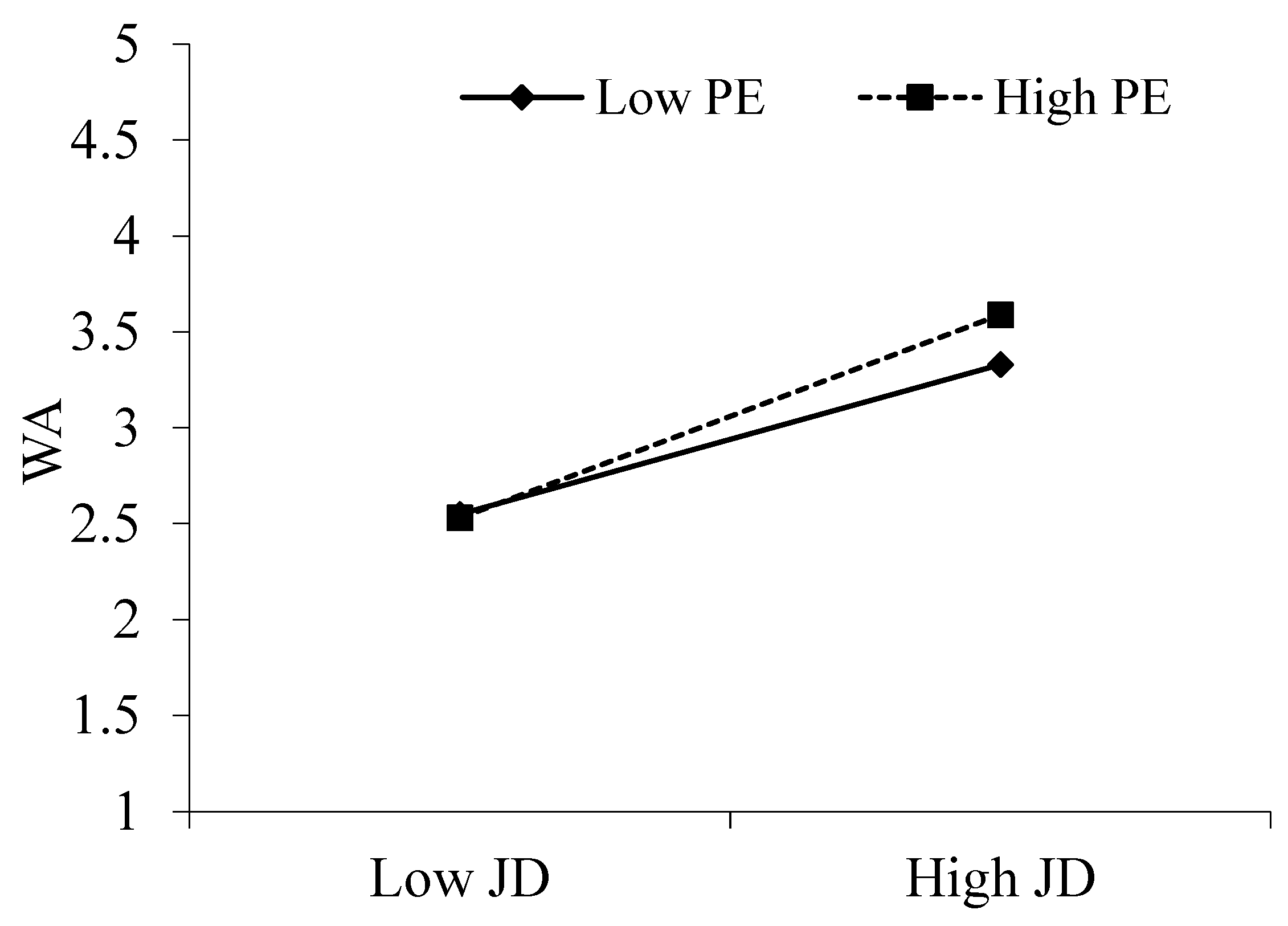

| Moderator: PE | JD→WA→WD | ||

| B | SE | 95% Boot CI | |

| Indirect effect | 0.14*** | 0.02 | [0.10, 0.20] |

| Direct effect | 0.30*** | 0.02 | [0.25, 0.34] |

| High(+PE) | 0.16*** | 0.02 | [0.11, 0.21] |

| Low(-PE) | 0.12*** | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.16] |

| Index | 0.02** | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.04] |

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Appendix A

- I must work in a timely and efficient manner to facilitate my organization's adaptation to the digital age.

- The volume of work required due to digital changes is considerable.

- The effort required to complete tasks related to digital-oriented changes is approximately double that which would otherwise be necessary.

- I am required to complete digitization-related tasks within a minimal timeframe.

- I consider the working environment to be less than ideal for meeting the demands of digitalization.

- I am responsible for dealing with a large backlog of work related to digital change.

- At work, I find myself learning often.

- I continue to learn more at work as time goes by.

- At work, I see myself continually improving.

- At work, I am learning.

- At work, I have developed a lot as a person.

- At work, I feel alive and vital.

- At work, I have energy and spirit.

- At work, I do feel very energetic.

- At work, I feel alert and awake.

- At work, I am looking forward to each new day.

- I am overwhelmed by thoughts of doing poorly at work.

- I worry that my work performance will be lower than others.

- I feel nervous and apprehensive about being unable to meet performance targets.

- I worry about not receiving a positive job performance evaluation.

- I often feel anxious that I cannot perform my job duties in the time allotted.

- I worry about whether others consider me to be a good employee for the job

- I worry that I will not be able to manage the demands of my job successfully.

- Even when I try as hard as possible, I still worry about whether my job performance will be good enough.

- I have absenteeism at work.

- I will talk about non-work topics with colleagues at work.

- I have left work for unnecessary reasons.

- I daydream at work.

- I spend work time on personal matters.

- I put less effort into my work than I should.

- I have thoughts of leaving my job.

- I want someone else to do my job.

- I have left work early without permission.

- I have taken lunch or breaks longer than allowed.

- I have taken supplies or equipment without permission.

- I have fallen asleep on the job.

- I will take it upon myself to introduce new methods and improve work procedures.

- I will change work procedures that I consider to be unproductive and of secondary importance

- I will seek to change my working methods to make myself more relaxed.

- I tend to rearrange the equipment in my work area by myself.

- I will organize special events at work (e.g., birthday celebrations for colleagues)

- I will bring my additional materials from home for the job.

- I get many things done at work

- I get my work done no matter what

- I can get much work done in a short period

- I am passionate about work activities that make me successful

- I strive to achieve work accomplishments

- I recognize how many tasks I can complete

- I comply with rules and regulations as much as possible.

- I prefer to do my work tasks correctly.

- I try to fulfill my obligations at work to the best of my ability.

- I pay attention to my job responsibilities.

- I try to fulfill my work obligations.

- I care about the details of my work.

References

- Chen:, N. : Zhao: X.; Wang, L. The Effect of Job Skill Demands under Artificial Intelligence Embeddedness on Employees’ Job Performance: A Moderated Double-Edged Sword Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghi, T.; Thu, N.; Huan, N.; Trung, N. Human Capital, Digital Transformation, and Firm Performance of Startups in Vietnam. Management 2022, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Fan, L. Working with AI: The Effect of Job Stress on Hotel Employees’ Work Engagement. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Huo, C. Enabling or Burdening?-The Double-Edged Sword Impact of Digital Transformation on Employee Resilience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 157, 108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, K.; Chu, F. The Two Faces of Artificial Intelligence (AI): Analyzing How AI Usage Shapes Employee Behaviors in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 122, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Grote, G. Automation, Algorithms, and beyond: Why Work Design Matters More than Ever in a Digital World. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 1171–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNuaimi, B.K.; Kumar Singh, S.; Ren, S.; Budhwar, P.; Vorobyev, D. Mastering Digital Transformation: The Nexus between Leadership, Agility, and Digital Strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Xu, Y.; Hussain, S. Understanding Employee Innovative Behavior and Thriving at Work: A Chinese Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Giancespro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Workload, Techno Overload, and Behavioral Stress during COVID-19 Emergency: The Role of Job Crafting in Remote Workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 655148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.M.; Koopman, J.; Mai, K.M.; De Cremer, D.; Zhang, J.H.; Reynders, P.; Ng, C.T.S.; Chen, I.-H. No Person Is an Island: Unpacking the Work and after-Work Consequences of Interacting with Artificial Intelligence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 1766–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; de Vries, J.D. Job Demands-Resources Theory and Self-Regulation: New Explanations and Remedies for Job Burnout. ANXIETY STRESS COPING 2021, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosse, J.G.; Hulin, C.L. Adaptation to Work: An Analysis of Employee Health, Withdrawal, and Change. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work Process and Quality of Care in Early Childhood Education: The Role of Job Crafting. Acad. Manage. J. 2009, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Su, D.; Smith, A.P.; Yang, L. Reducing Work Withdrawal Behaviors When Faced with Work Obstacles: A Three-Way Interaction Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Giovando, G. Digital Workplace and Organization Performance: Moderating Role of Digital Leadership Capability. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources and Disaster in Cultural Context: The Caravans and Passageways for Resources. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2012, 75, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gong, X.; Liu, Y. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Employees’ Innovation Behavior in the Context of Digital Transformation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1090961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K.; Chang, C.-H. “Daisy”; Johnson, R.E. Regulatory Focus and Work-Related Outcomes: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 998–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, V.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Hetty Van Emmerik, I.J. Regulatory Focus at Work: The Moderating Role of Regulatory Focus in the Job Demands-resources Model. Career Dev. Int. 2010, 15, 708–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, Y. Job Demands-Resources on Digital Gig Platforms and Counterproductive Work Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1378247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Weng, Q.; Zhu, L. How Different Forms of Job Crafting Relate to Job Satisfaction: The Role of Person-Job Fit and Age. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 11155–11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Wiesböck, F. Options for Formulating a Digital Transformation Strategy. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Gevers, J.M.P. Job Crafting and Extra-Role Behavior: The Role of Work Engagement and Flourishing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a Job on a Daily Basis: Contextual Correlates and the Link to Work Engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Reyes, J.; Acosta-Prado, J.C.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C. Relationship amongst Technology Use, Work Overload, and Psychological Detachment from Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. In ANNUAL REVIEW OF ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY AND ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR, VOL 5; Morgeson, F., Ed.; Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. Job Demands-Resources Theory in Times of Crises: New Propositions. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 13, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A Socially Embedded Model of Thriving at Work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nix, G.A.; Ryan, R.M.; Manly, J.B.; Deci, E.L. Revitalization through Self-Regulation: The Effects of Autonomous and Controlled Motivation on Happiness and Vitality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 35, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.S.; Dweck, C.S. Goals: An Approach to Motivation and Achievement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Bell, C.M. From Thriving to Task Focus: The Role of Needs-Supplies Fit and Task Complexity. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 28988–28998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Grote, G. Automation, Algorithms, and beyond: Why Work Design Matters More than Ever in a Digital World. Appl. Psychol.- Int. Rev.-Psychol. Appl.-Rev. Int. 2022, 71, 1171–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at Work: Toward Its Measurement, Construct Validation, and Theoretical Refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Gibson, C.B.; Spreitzer, G.M. To Thrive or Not to Thrive: Pathways for Sustaining Thriving at Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2022, 42, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.M.; Trougakos, J.P.; Cheng, B.H. Are Anxious Workers Less Productive Workers? It Depends on the Quality of Social Exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. The Effect of Job Skill Demands under Artificial Intelligence Embeddedness on Employees’ Job Performance: A Moderated Double-Edged Sword Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Qi Dong, J.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O. On the Future of Macroeconomic Models. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2018, 34, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.; Curtis, C.; Ryan, B. Examining the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Hotel Employees through Job Insecurity Perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar Kozanoglu, D.; Abedin, B. Understanding the Role of Employees in Digital Transformation: Conceptualization of Digital Literacy of Employees as a Multi-Dimensional Organizational Affordance. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 34, 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Quintana, T.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Araujo-Cabrera, Y.; Sanabria-Díaz, J.M. Do Job Insecurity, Anxiety and Depression Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic Influence Hotel Employees’ Self-Rated Task Performance? The Moderating Role of Employee Resilience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Hotel Service Providers’ Emotional Labor: The Antecedents and Effects on Burnout. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Cao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Miao, D. Reflections on Motivation: How Regulatory Focus Influences Self-Framing and Risky Decision Making. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 2927–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond Pleasure and Pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Promotion and Prevention: Regulatory Focus as a Motivational Principle. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier, 1998; Vol. 30, pp. 1–46 ISBN 978-0-12-015230-8.

- Friedman, R.S.; Förster, J. The Effects of Promotion and Prevention Cues on Creativity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Friedman, R.S.; Harlow, R.E.; Idson, L.C.; Ayduk, O.N.; Taylor, A. Achievement Orientations from Subjective Histories of Success: Promotion Pride versus Prevention Pride. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.D.; Smith, M.B.; Wallace, J.C.; Hill, A.D.; Baron, R.A. A Review of Multilevel Regulatory Focus in Organizations. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1501–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Brockner, J. The Interactive Effect of Positive Inequity and Regulatory Focus on Work Performance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 57, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job Demands, Perceptions of Effort-Reward Fairness and Innovative Work Behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.C.; Johnson, P.D.; Frazier, M.L. An Examination of the Factorial, Construct, and Predictive Validity and Utility of the Regulatory Focus at Work Scale. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 805–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.M.; Trougakos, J.P.; Cheng, B.H. Are Anxious Workers Less Productive Workers? It Depends on the Quality of Social Exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, W.E.; Simpson, D.D. Employee Substance Use and On-the-Job Behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work Process and Quality of Care in Early Childhood Education: The Role of Job Crafting. Acad. Manage. J. 2009, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, A.K.; Zo, H.; Eom, J.; Chiravuri, A. Identifying Organizations’ Dynamic Capabilities for Sustainable Digital Transformation: A Mixed Methods Study. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento, C.A.; Fay, D.; West, M.A. Workplace Duties or Opportunities? Challenge Stressors, Regulatory Focus, and Creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 121, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Code | Frequency | Percentage |

| Sex | Male | 1 | 456 | 52.2 |

| Female | 0 | 417 | 47.8 | |

| Education | College and below | 1 | 47 | 5.4 |

| Bachelor's Degree | 2 | 262 | 30.0 | |

| Master's degree | 3 | 564 | 64.6 | |

| Rank | Section Chief | 1 | 368 | 42.2 |

| Deputy Section | 2 | 291 | 33.3 | |

| Full Section | 3 | 214 | 24.5 |

| Model | Factors | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-factor model | JD; PO; PE; TW; WA; JC; WD | 2451.70 | 901 | 2.72 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 6-factor model | JD+PO; PE; TW; WA; JC; WD | 11642.85 | 1112 | 10.47 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| 5-factor model | JD+PO+PE; TW; WA; JC; WD | 15991.17 | 1117 | 14.32 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| 4-factor model | JD+PO+PE+TW; WA; JC; WD | 23544.73 | 1121 | 21.00 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| 3-factor model | JD+PO+PE+TW+WA; JC; WD | 26717.26 | 1124 | 23.77 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| 2-factor model | JD+PO+PE+TW+WA+JC; WD | 29345.35 | 1126 | 26.06 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| 1-factor model | JD+PO+PE+TW+WA+JC+WD | 31257.59 | 1127 | 27.74 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| 1. Gender (T1) | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Age (T1) | 0.07* | - | |||||||||

| 3. Education (T1) | 0.05 | 0.14** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Rank (T1) | -0.08* | -0.16** | -0.05 | - | |||||||

| 5. JD (T1) | -0.11** | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.76 | ||||||

| 6. PO (T1) | -0.16** | 0.09** | -0.01 | 0.06 | 0.35** | 0.86 | |||||

| 7. PE (T1) | -0.23** | 0.09** | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.21** | 0.36** | 0.80 | ||||

| 8. TW (T2) | -0.10** | 0.06 | -0.01 | 0.02 | 0.48** | 0.33** | -0.22** | 0.89 | |||

| 9. WA (T2) | -0.12** | 0.06 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.49** | -0.37** | 0.23** | -0.48** | 0.89 | ||

| 10. JC (T3) | -0.10** | 0.02 | -0.01 | -0.03 | 0.44** | 0.11** | -0.14** | 0.33** | -0.35** | 0.82 | |

| 11. WD (T3) | -0.17** | 0.04 | -0.04 | 0.04 | 0.56** | 0.40** | 0.27** | -0.52** | 0.57** | -0.62** | 0.73 |

| Mean | 0.48 | 40.53 | 2.59 | 1.82 | 3.83 | 2.57 | 2.55 | 3.64 | 3.64 | 3.73 | 3.83 |

| PE | 0.50 | 9.06 | 0.59 | 0.80 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.51 |

| Cronbach’s α | - | - | - | - | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| CR | - | - | - | - | 0.81 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.90 |

| AVE | - | - | - | - | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

| Variables | TW | JC | WA | WD | ||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| JD | 0.46*** | 0.03 | 0.41*** | 0.04 | 0.46*** | 0.03 | 0.30*** | 0.02 |

| PO | 0.08*** | 0.02 | ||||||

| JD×PO | 0.15*** | 0.03 | ||||||

| PE | 0.06** | 0.02 | ||||||

| JD×PE | 0.07** | 0.03 | ||||||

| TW | 0.16*** | 0.04 | ||||||

| WA | 0.30*** | 0.03 | ||||||

| Gender | -0.05 | 0.04 | -0.08 | 0.04 | -0.05 | 0.04 | -0.09** | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.05** | 0.02 |

| Type | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.05 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).