1. Introduction

Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D members 1 and 2 (NR1D1 / NR1D2), also known as REV-ERBɑ and REV-ERBβ, were named for their unique genomic organization, encoded by the opposite DNA strand of the ERBA gene, which encodes the thyroid hormone receptor-α. Unlike many nuclear receptors that function as obligate heterodimers, REV-ERBs typically operate as monomers recognizing a specific half-site sequence [

1]. REV-ERBɑ and REV-ERBβ act as transcriptional repressors through two distinct mechanisms: they compete with RORs for binding to RORE-containing enhancers and recruit NCoR complexes that include the epigenomic modulator histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) to actively repress transcription [

2]. Both receptors exhibit overlapping expression patterns and circadian rhythms, highlighting their significant and coordinated roles in regulating transcription. The genes encoding both REV-ERBs exhibit strong circadian rhythmicity in various mammalian tissues [

2,

3,

4], with peak expression during the light phase in laboratory animals [

3,

5], and is expected to have peak early in the morning with nadir in the evening in human blood cells [

6,

7]. REV-ERBs modulate the rhythmic expression of several core clock genes, including Bmal1, Npas2, Clock, and Cry1, reviewed in [

2,

8]. Knocking down both REV-ERBs profoundly alters the circadian free-running period and also impairs lipid metabolism [

3,

9]. Beyond their role in the core clock loop, REV-ERBs directly regulate circadian-controlled genes (CCGs), facilitating tissue-specific modulation of the circadian transcriptome, reviewed in [

2,

8]. Rev-erbα abundance is regulated by the molecular clock, but it can be influenced by environmental factors like light and food, depending on the tissue. Its activity can also be affected by its ligand (heme), circadian fluctuations, and conditions that alter its levels, such as cold exposure and glucocorticoids [

5]. Consequently, Rev-erbα represses genes in a tissue-specific manner, resulting in distinct functions across different cell types.

Circadian disruption, such as that experienced in shift work, can lead to metabolic diseases due to a mismatch between internal biological clocks and environmental cues. While the SCN REV-ERB nuclear receptors are not essential for maintaining rhythmicity, they do influence the length of the free-running period. This property is illustrated by studies showing that mice lacking these receptors exhibited shortened rhythms and increased weight gain on an obesogenic diet, a condition that improved when environmental lighting was aligned with their altered 21-hour clock [

11]. The whole-brain knockout of REV-ERBα affects not only the circadian locomotor activity rhythm but it can be essential even for the circadian rhythmicity of food intake and food-anticipatory behavior [

12]. Furthermore, REV-ERBɑ may mediate light-dependent changes in mood via serotonin modulation [

13,

14]. The mononuclear expression of Rev-erbs is also integrated into a BodyTime assay that aims to determine the internal circadian time in humans using a single morning blood sample [

15].

However, the expression of REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ has been much less studied in humans compared to experimental laboratory rodents, which are primarily nocturnal, in contrast to diurnal humans. It remains largely unknown whether the expression of REV-ERBs is influenced by the challenging environmental light conditions at high Arctic latitudes and whether differences exist between adapted native populations of these regions and non-native newcomers. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the expression of the major REV-ERBα by analyzing the relative abundance of rev-erbα mRNA in blood mononuclear cells from both Arctic native and non-native residents during equinoxes and solstices, as part of the broader Light Arctic project.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tyumen State Medical University (Protocol No. 101, September 13, 2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, as published previously [

16,

17].

2.1. Subjects and Data Collection

Situated at latitudes 65°58′ - 66°53 N, longitude 66°60′ - 76°63′ E, 29 Arctic residents (age range 18-52, mean age 39.3 years, 82.8% women, 27.6% Arctic natives) provided seven-day actigraphy records and morning blood samples in each season during spring / autumn equinoxes, and winter / summer solstices, as previously described [

16,

17].

2.2. NR1D1 (REV-ERBɑ) Expression

All blood samples were collected at 08:00 during weekends closest to the winter and summer solstices and to the spring and autumn equinoxes, as described elsewhere [

16,

17]. To keep the genetic material intact during transportation, RNA in patient blood samples was preserved using Blood RNA Stabilizer reagent from Inogen (St. Petersburg, Russia). Total RNA was isolated using PureZol reagent (Bio-Rad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and integrity was controlled via denaturing gel electrophoresis in 2.5% agarose. Synthesis of the first strand of cDNA was performed using the MMLV Kit from Eurogen (Moscow, Russia) according to the company’s instructions. At least 100 ng of total RNA was used into the cDNA synthesis reaction. NR1D1 (REV-ERBα) expression was determined by real-time PCR on a CFX96 Nucleic Acid Amplification Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc, USA). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was used as a reference gene. The primer sequences for real-time PCR were as follows NR1D1 forward 5’- CCATCGTCCGCATCAATCAATCG- 3’; NR1D1 reverse 5’- GCATCTCAGCAAGCAGCATCCG-3’; GAPDH forward 5’-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3’; GAPDH reverse 5’-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3’. Data from qPCR results were analyzed by the CFX Manager 3.1 software (Bio-Rad, USA). The relative level of gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq formula [

18].

2.3. Actigraphy

A seven-day actigraphy protocol using the ActTrust 2 device (Condor Instruments, São Paulo, Brazil) followed the methodology outlined in previous studies [

16,

17,

19,

20]. The ActTrust 2 recorded various metrics at one-minute intervals, including motor activity (Proportional Integrative Mode, PIM), wrist skin temperature (wT), and light intensity (lux). Additionally, it measured infrared, red, green, blue, and ultraviolet A (UVA) and B (UVB) light intensities (in μw/cm²). Parametric endpoints such as MESOR (M), 24-hour amplitude (24h-A), and acrophase were computed for PIM, wT, light exposure (LE), and blue light exposure (BLE). Non-parametric endpoints such as activity during the peak 10-hour period (M10), M10 onset, the least active 5-hour period (L5), L5 onset, inter-daily stability (IS), intra-daily variability (IV), relative amplitude (RA = (M10-L5)/(M10+L5)), and the circadian function index (CFI) were estimated for PIM and BLE using the ActStudio software (Condor Instruments, São Paulo, Brazil). Sleep parameters such as bedtime, wake time, time in bed, total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep latency, and wake after sleep onset (WASO) were calculated along with their standard deviations (SD) using the same software.

2.4. Data and Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Libre Office Calc, STATISTICA 6, and IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0. Not all 29 participants provided blood samples in all seasons. To ensure reliability of the results, we first assessed the normality of each variable’s distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk W-test and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Based on the test outcome, we used either the parametric Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney’s U-test, or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis H-test to compare variables across different seasons and populations. Tukey’s Honestly Significant Test (HST) was used as post-hoc analysis for between-season differences. Additionally, we applied multivariable ANCOVA with sigma-restricted parameterization to identify the most significant actigraphy-derived predictors while controlling for potential confounding factors, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and population. Amplitude (a measure of half the extent of predictable variation within a 24-h cycle), acrophase (a measure of the time of overall high values in a cycle), and MESOR (Midline Estimating Statistic Of Rhythm, or a rhythm-adjusted mean) values were estimated by cosinor analysis [

21].

3. Results

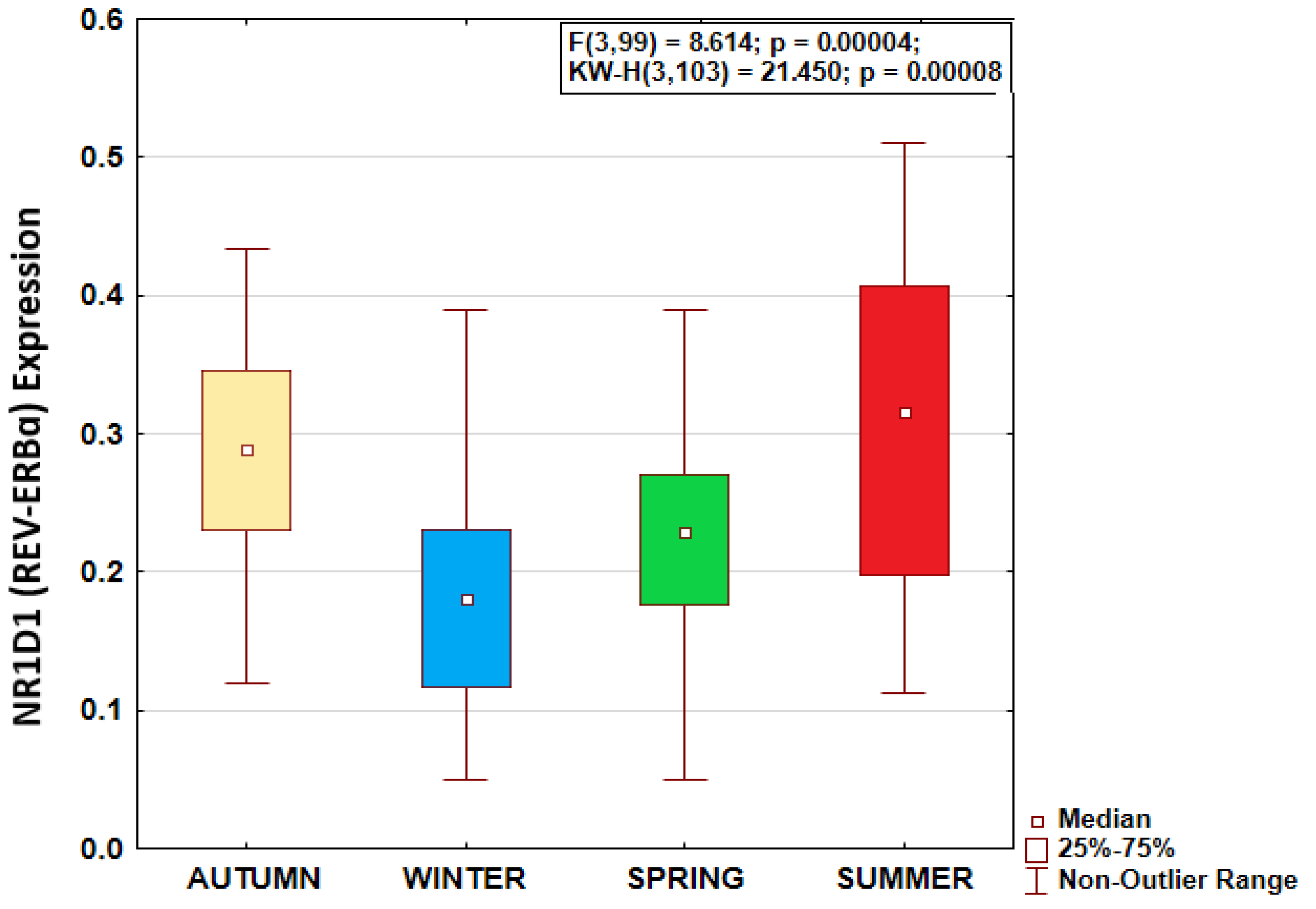

NR1D1 expression data were normally distributed in each season (Shapiro-Wilk’s W>0.935; p>0.115). Season greatly affected REV-ERBα expression, as shown by ANOVA, with highest expression during summer solstice and lowest expression during winter solstice (F(3,99) = 8.614; p=0.00004) (

Figure 1). Tukey HST validated REV-ERBα expression to be higher during summer solstice than winter solstice (p=0.0002) and spring equinox (p=0.044), and higher during autumn equinox than during winter solstice (p=0.0011). Age, sex, and BMI were not significantly associated with REV-ERBα expression or its seasonal pattern (

Table 1). Overall, REV-ERBα expression was significantly higher in native individuals indigenous to the high Arctic latitudes than in newcomers (F(1,101) = 5.769; p = 0.018), both populations showing a similar seasonal pattern of REV-ERBα expression (

Figure 2).

REV-ERBα expression was associated with actigraphy-derived measures both across and within seasons.

Supplemental Tables S1–S3 show seasonal changes in the MESOR of light exposure and in the MESOR and phase of physical activity.

Supplemental Table S4 displays the correlation matrix documenting associations between REV-ERBα expression and variables recorded by actigraphy. Overall measures of daytime light and blue light exposure, such as M, 24-h A, and M10, and measures of physical activity (M, 24-h A, and M10) consistently demonstrated stronger associations with REV-ERBα expression compared to indices of sleep or wrist temperature. REV-ERBα expression was also significantly associated with the circadian phase of light exposure. Inter-individual differences in NR1D1 expression within distinct seasons were more closely linked to physical activity (lower correlation in winter (r=0.323, p=0.087) and higher at summer (r=0.566, p=0.008)) than to light exposure. While light exposure did not correlate with REV-ERBα expression in winter when light availability is lowest (r=0.052, p=0.791 for LE MESOR), it correlated in summer when light is abundant (r=0.480, p=0.038 after correcting for two outliers). Seasonal changes in REV-ERBα expression were closely coupled with the amount and timing of LE.

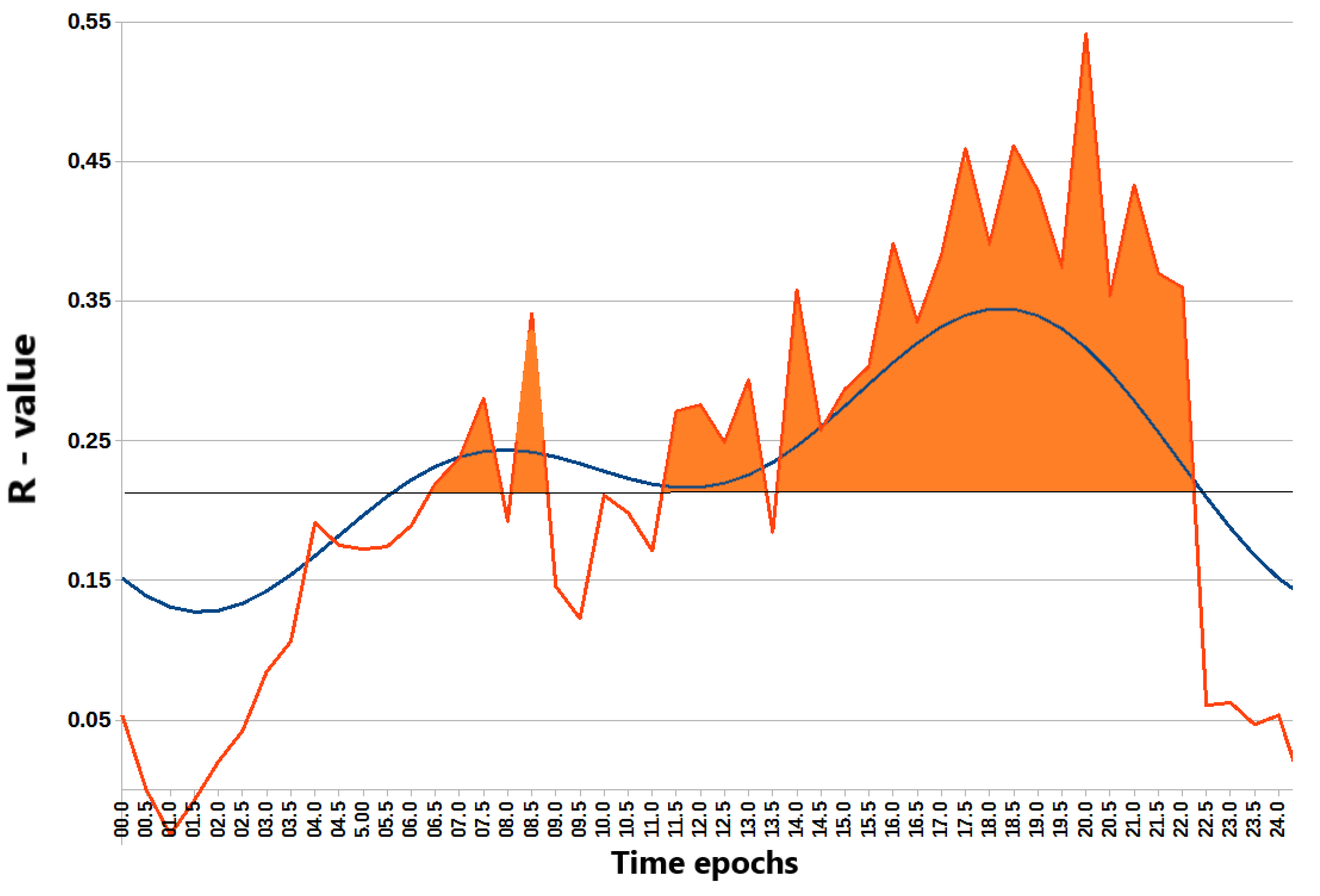

To further elucidate the relationship between the timing of light exposure and REV-ERBα expression, NR1D1 expression was correlated with the average light exposure in consecutive 30-minute epochs across participants, yielding 48 correlation coefficients. Results revealed time windows when light exposure correlated most strongly with REV-ERBα expression (

Figure 3). The strongest correlations were observed in the early morning and even more prominently after noon. A 2-component model, incorporating both 24-hour and 12-hour harmonics, approximates well the correlation pattern (F=34.4, p<0.00001), validating two significant peaks: a minor morning peak at 07:18 and a major evening peak at 19:31. These findings suggest a complex rhythmic relationship between light exposure and REV-ERBα expression, with distinct morning and evening peaks. Interestingly, a similar approach used to search for epochs of strongest correlation between physical activity and REV-ERBα expression only found the 12-hour harmonic to be significant (F=10.5; p=0.0002), accounting for two daily peaks, in the morning at 07:26 and in the evening at 19:26,

Supplemental Figure S1. While the evening peak predicted by the model closely matches the actual peak, the first peak predicted by the model precedes the actual peak observed at 12:30.

Three advanced general regression models using sigma-restricted parameterization examined factors affecting REV-ERBα expression. To avoid over-representation of seasons with similar light conditions (spring and autumn), we categorized the data into three distinct seasons: winter, spring, and summer, omitting data from autumn,

Table 1. In the first model, we included the MESOR of light exposure along with age, sex, BMI, and population, as well as the 24-hour phase of light exposure. Acrophases of light exposure were in narrow range with 95% confidence interval within 60 minutes (

Supplemental Table S2) justifying their consideration in a linear analysis. This model revealed that the MESOR and phase of light exposure and population were significant predictors of REV-ERBα expression. The MESOR of light exposure accounted for the largest portion of variability in REV-ERBα expression, achieving an observed power of 0.974. The second model considered the MESOR of physical activity, which emerged as another significant predictor of NR1D1 expression alongside the MESOR and acrophase of light exposure. In the third model, we replaced light exposure with seasonality, given their close relationship. This model reaffirmed that the phase of light exposure and the MESOR of physical activity were significant predictors of NR1D1 expression.

4. Discussion

The current study examined seasonal and indigeneity aspects of the REV-ERBα (NR1D1) expression in human blood mononuclear cells under drastically varying seasonal light conditions of the Arctic region. Our findings indicate that REV-ERBα exhibits significant seasonality, with peak expression during the summer solstice and lowest expression during the winter solstice in both Arctic native and non-native residents, while overall expression in native Arctic residents is higher than in newcomers, particularly at summer solstice. Our data also show that daytime light exposure is a strong predictor of REV-ERBα expression, suggesting that environmental light conditions significantly affect this regulatory mechanism. The observed seasonal variation highlights the dynamic nature of REV-ERBα expression, likely reflecting adaptations to changing photoperiods characteristic of high-latitude environments. Our results add novel human data that are in line with the previous finding showing photoperiodic changes in Rev-erbɑ expression in hamster tissues with lower expression and delayed phase in short photoperiods [

22,

23,

24] similar to ambient light conditions in the Arctic winter [

16,

17]. It was hypothesized that REV-ERBα may interact with melanopsin to regulate the sensitivity of the rod-mediated intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell (ipRGC) pathway, thereby coordinating activity in response to ambient blue light exposure [

25].

As light exposure only correlated weakly with REV-ERBα expression in some seasons, results from the three advanced general regression models suggest that the pronounced yearly rhythm in REV-ERBα expression might be driven by the amount and timing of light exposure. Amount of daylight exposure, sufficient enough to boost REV-ERBα expression may be required, alternatively, other factors may account for the variation in the morning REV-ERBα expression, including phasic differences in circadian rhythm of REV-ERBα expression. While individuals vary significantly in their sensitivity to light, there was no clear pattern in the response of melatonin to seasonal changes across individuals. However, seasonal variations of dim light melatonin onset and 24-hour acrophase of melatonin [

17] were similar to those in REV-ERBα expression observed herein, suggesting that REV-ERBα expression responds in a similar way as melatonin to seasonal changes, with overall light exposure and its timing likely influencing these fluctuations. Additionally, physical activity appears to contribute to individual differences in response to seasonal changes in REV-ERBα expression.

Given that REV-ERBα expression in our study was assessed during or soon after expected peak of its expression [

3,

6,

7], one may suggest that likewise circadian awakening response of cortisol can in part be response to “activity-related demands” [

26], it can also be applied to explaining specific to REV-ERBα morning expression. Furthermore, it can be noted that not only circadian peak of cortisol can be close to peak of REV-ERBα expression is human blood cells, cortisol also had summer solstice peak in this very cohort, as previously reported [

17].

Overall seasonal patterns of REV-ERBα expression were similar between native and non-native residents, yet subtle differences in expression levels suggest that long-term adaptation to extreme light conditions may affect the circadian system’s sensitivity to environmental cues. Further exploration of genetic and epigenetic variations could provide deeper insights into these adaptive mechanisms. Synthetic REV-ERB agonists have been investigated for their potential to synchronize circadian rhythms and modulate metabolic processes, resulting in improved cardiovascular health and reduced obesity through enhanced energy expenditure and metabolic gene expression [

27]. Given the established connection between REV-ERBα and metabolic health [

9,

11], our findings underscore the implications of circadian disruption—often linked to metabolic disorders—in challenging light environments. Additionally, animal studies indicate that light exposure can enhance the leukocyte immune response, mediated by REV-ERBα. For instance, daytime exposure to blue light significantly improved immune function and survival rates during infections by entraining circadian rhythms, shifting the autonomic balance toward parasympathetic dominance, and activating the REV-ERBα protein [

28]. This activation ultimately enhances pathogen clearance and reduces inflammation, including in the brain [

29,

30,

31]. Thus, REV-ERBα activation may play a crucial role in protecting the organism against neurodegenerative diseases [

32,

33], cancer [

34] and in preventing cardiac [

35,

36], hepatic [

37] and pulmonary fibrosis [

38,

39].

Results obtained in this study suggest that timed physical activity and light exposure may act in tandem to facilitate REV-ERBα expression that may help to maintain robust circadian rhythmicity and withstand disruptive challenges [

40]. Together, these findings highlight the need for further research to clarify the interactions among timed physical activity, seasonal variations in light exposure, and REV-ERBα expression. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for exploring how optimizing daytime light exposure may help mitigate the negative effects associated with circadian disruptions, poor light hygiene, and the heightened risk of inflammatory and metabolic disorders.

Study limitations. While our study provides valuable insights into the seasonal and environmental influences on REV-ERBα expression, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, the focus on a single time point (08:00) of REV-ERBα determination, which is expected to be close to average time of its acrophase, precludes a comprehensive understanding of daily oscillations in REV-ERBα expression and how its circadian pattern may differ across seasons beyond its mean value. As this study assessed REV-ERBɑ expression only during one point in time, both differences in average 24-h expression or changes in 24-h amplitude and/or phase that is expected to be advanced in the longer photoperiod of the summer solstice, could contribute to seasonal changes revealed in this study. Future studies should incorporate multiple sampling times throughout the day to capture the full circadian profile of REV-ERBα. Additionally, exploring the expression of other key circadian regulators, such as REV-ERBβ, would provide a more complete picture of the circadian machinery’s response to environmental challenges. Longitudinal studies tracking individuals over extended periods could also shed light on inter-individual variability and the long-term consequences of circadian misalignment. Our study underscores the importance of considering environmental factors, particularly light exposure, in understanding the dynamics of REV-ERBα expression and its implications for circadian rhythm regulation and metabolic health. These findings lay the groundwork for future investigations aimed at developing targeted interventions to mitigate the negative effects of circadian disruption in extreme environments.

5. Conclusions

Overall, our findings reveal a clear seasonal pattern in REV-ERBα expression, with levels surging to a peak during the summer solstice and dropping to a nadir during the winter solstice, independently of sex, age, or indigeneity that could be closely coupled with seasonal changes in the abundance of daylight. Light received after noon may is most closely coupled with REV-ERBα expression. Natives have higher REV-ERBα morning expression overall and at summer solstice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Chart of r-values from a linear regression of NR1D1 (REV-ERBɑ) expression with physical activity; Table S1: Supplemental Table S1. Light exposure MESOR characteristics by season; Table S2: Supplemental Table S2. Light exposure phase characteristics by season; Table S3: Supplemental Table S3. No evidence for seasonal differences in MESOR of physical activity; Table S4: Supplemental Table S4. Correlation matrix for associations between NR1D1 (REV-ERBɑ) expression with variables monitored by actigraphy.

Author Contributions

DG: SK designed the study. DG, KD, OS, SK, MB, GC, DW developed methods. DG, AM, KV, MM collected data. SK, DG, AS, OS, KV, GC, SK, JB, JV, and DW analysed and interpreted the data. DG, OS, SK, MB, GC and DW prepared the manuscript. DG, IP acquired funding. DG, KD, OS, AM, IP supervised project. Approve the final version of the manuscript: all authors.

Funding

The study was supported by the West-Siberian Science and Education Center, Government of Tyumen District, Decree of 20.11.2020, No. 928-rp. The study was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (government topic FMEN 2022-0009). The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research. The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This cross-sectional study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tyumen State Medical University (Protocol No. 101, September 13, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all participants of this study and medical personal at Aksarka Boarding School, Salekhard, and Urengoy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Kojetin, D.J.; Burris, T.P. REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 13,197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlanmerini, M.; Lazar, M.A. The REV-ERB Nuclear Receptors: Timekeepers for the Core Clock Period and Metabolism. Endocrinology. 2023, 164, bqad069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Zhao, X.; Hatori, M.; Yu, R.T.; Barish, G.D.; Lam, M.T.; Chong, L.W.; DiTacchio, L.; Atkins, A.R.; Glass, C.K.; Liddle, C.; Auwerx, J.; Downes, M.; Panda, S.; Evans, R.M. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-α and REV-ERB-β. Nature. 2012, 485, 485,123–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Downes, M.; Yu, R.T.; Bookout, A.L.; He, W.; Straume, M.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Evans, R.M. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006, 126, 126,801–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Feng, D.; Emmett, M.J.; Everett, L.J.; Loro, E.; Briggs, E.R.; Bugge, A.; Hou, C.; Ferrara, C.; Seale, P.; Pryma, D.A.; Khurana, T.S.; Lazar, M.A. The nuclear receptor Rev-erbα controls circadian thermogenic plasticity. Nature. 2013, 503, 503,410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi., J.; Tong, R.; Zhou, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Lu, D.; Meng, G.; Hu, L.; Yuan, A.; Lu, X.; Pu, J. Shi. J.; Tong, R.; Zhou, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, G.; Lu, D.; Meng, G.; Hu, L.; Yuan, A.; Lu, X.; Pu, J. Circadian nuclear receptor Rev-erbα is expressed by platelets and potentiates platelet activation and thrombus formation. Eur Heart J, 2317; 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teppan., J.; Schwanzer, J.; Rittchen, S.; Bärnthaler, T.; Lindemann, J.; Nayak, B.; Reiter, B.; Luschnig, P.; Farzi, A.; Heinemann, A.; Sturm, E. Teppan. J.; Schwanzer, J.; Rittchen, S.; Bärnthaler, T.; Lindemann, J.; Nayak, B.; Reiter, B.; Luschnig, P.; Farzi, A.; Heinemann, A.;, Sturm, E. The disrupted molecular circadian clock of monocytes and macrophages in allergic inflammation. Front Immunol. 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.G. [Molecular basis of circadian rhythms and principles of circadian disruption]. Usp Fiziol Nauk.

- Bugge, A.; Feng, D.; Everett, L.J.; Briggs, E.R.; Mullican, S.E.; Wang, F.; Jager, J.; Lazar, M.A. Rev-erbα and Rev-erbβ coordinately protect the circadian clock and normal metabolic function. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 26,657–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Lazar, M.A. Rev-erbα and the circadian transcriptional regulation of metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab, 1: 17 Suppl 1(0 1). [CrossRef]

- Adlanmerini, M.; Krusen, B.M.; Nguyen, H.C.B.; Teng, C.W.; Woodie, L.N.; Tackenberg, M.C.; Geisler, C.E.; Gaisinsky, J.; Peed, L.C.; Carpenter, B.J.; Hayes, M.R.; Lazar, M.A. REV-ERB nuclear receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus control circadian period and restrict diet-induced obesity. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eabh2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delezie, J.; Dumont, S.; Sandu, C.; Reibel, S.; Pevet, P.; Challet, E. Rev-erbα in the brain is essential for circadian food entrainment. Sci Rep, 2: 6, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Le, H.T.; Thein, Z.L.; Ihara, H.; Sato, F.; Nakao, T.; Kohsaka, A. Deficiency of the circadian clock gene Rev-erbα induces mood disorder-like behaviours and dysregulation of the serotonergic system in mice. Physiol Behav. 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Choi, M.; Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Choe, Y.; Geum, D.; Yu, S.W.; Choi, J.W.; Moon, C.; Choe, H.K.; Son, G.H; Kim, K. Role of the circadian nuclear receptor REV-ERBα in dorsal raphe serotonin synthesis in mood regulation. Commun Biol. 2024, 7, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenbrink, N.; Ananthasubramaniam, B.; Münch, M.; Koller, B.; Maier, B.; Weschke, C.; Bes, F.; de Zeeuw, J.; Nowozin, C.; Wahnschaffe, A.; Wisniewski, S.; Zaleska, M.; Bartok, O.; Ashwal-Fluss, R.; Lammert, H.; Herzel, H.; Hummel, M.; Kadener, S.; Kunz, D.; Kramer, A. High-accuracy determination of internal circadian time from a single blood sample. J Clin Invest. 2018, 128, 128,3826–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Danilenko, K.; Stefani, O.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Markov, A.; Petrov, I.; Voronin, K.; Mezhakova, M.; Borisenkov, M.; Shigabaeva, A.; Yuzhakova, N.; Lobkina, S.; Weinert, D.; & Cornelissen, G. ; & Cornelissen, G. (Blue Light and Temperature Actigraphy Measures Predicting Metabolic Health Are Linked to Melatonin Receptor Polymorphism. Biology. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Danilenko, K.; Stefani, O.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Markov, A.; Petrov, I.; Voronin, K.; Mezhakova, M.; Borisenkov, M.; Shigabaeva, A.; Yuzhakova, N.; Lobkina, S.; Petrova, J.; Malyugina, O.; Weinert, D.; Cornelissen, G. Light Environment of Arctic Solstices is Coupled With Melatonin Phase-Amplitude Changes and Decline of Metabolic Health. J Pineal Res. 2025, 77, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak., K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Livak. K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods, 25. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Boldyreva, J.; Stefani, O.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Danilova, L.; Markov, A.; … Weinert, D. Light exposure predicts COVID-19 negative status in young adults. Biological Rhythm Research. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Boldyreva, J.; Stefani, O.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Danilova, L.; Shigabaeva, A.; Cornelissen, G.; Weinert, D. Higher vulnerability to poor circadian light hygiene in individuals with a history of COVID-19. Chronobiol Int, 1: Jan. [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G. Cosinor-based rhythmometry. Theor Biol Med Model. 2014 Apr 11;11:16. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.D.; Ebling, F.J.; Hazlerigg, D.G. Photoperiod regulates multiple gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei and pars tuberalis of the Siberian hamster (Phodopus sungorus). Eur J Neurosci. 2005, 21, 21,2967–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournier, B.B.; Dardente, H.; Simonneaux, V.; Vivien-Roels, B.; Pévet, P.; Masson-Pévet, M.; Vuillez, P. Seasonal variations of clock gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei and pars tuberalis of the European hamster (Cricetus cricetus). Eur J Neurosci. 2007, 25, 25,1529–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcu, A.; Riddle, M.; Dulcis, D.; Welsh, D.K. Photoperiod-Induced Neuroplasticity in the Circadian System. Neural Plast, 5: 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Hmyed Hakkari, O.; Acar, N.; Savier, E.; Spinnhirny, P.; Bennis, M.; Felder-Schmittbuhl, M.P.; Mendoza, J.; Hicks, D. Rev-Erbα modulates retinal visual processing and behavioral responses to light. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 30,3690–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalder, T.; Oster, H.; Abelson, J.L.; Huthsteiner, K.; Klucken, T.; Clow, A. The Cortisol Awakening Response: Regulation and Functional Significance. Endocr Rev. 2025, 46, 46,43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, L.A.; Wang, Y.; Banerjee, S.; Hughes, T.; Kojetin, D.J.; Lundasen, T.; Shin, Y.; Liu, J.; Cameron, M.D.; Noel, R.; Yoo, S.H.; Takahashi, J.S.; Butler, A.A.; Kamenecka, T.M.; Burris, T.P. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by synthetic REV-ERB agonists. Nature. 2012, 485, 485,62–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griepentrog, J.E.; Zhang, X.; Lewis, A.J.; Gianfrate, G.; Labiner, H.E.; Zou, B.; Xiong, Z.; Lee, J.S.; Rosengart, M.R. Frontline Science: Rev-Erbα links blue light with enhanced bacterial clearance and improved survival in murine Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. J Leukoc Biol. 2020, 107, 107,11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P.; Dimitry, J.M.; Sheehan, P.W.; Lananna, B.V.; Guo, C.; Robinette, M.L.; Hayes, M.E.; Cedeño, M.R.; Nadarajah, C.J.; Ezerskiy, L.A.; Colonna, M.; Zhang, J.; Bauer, A.Q.; Burris, T.P.; Musiek, E.S. Circadian clock protein Rev-erbα regulates neuroinflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 116,5102–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Chi, X.; Sun, Y.; Han, C.; Wan, F.; Hu, J.; Yin, S.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zou, W.; Xiong, N.; Huang, J.; Xia, Y.; Wang, T. The circadian clock protein Rev-erbα provides neuroprotection and attenuates neuroinflammation against Parkinson’s disease via the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome. J Neuroinflammation. 2022, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Dimitry, J.M.; Song, J.H.; Son, M.; Sheehan, P.W.; King, M.W.; Travis Tabor, G.; Goo, Y.A.; Lazar, M.A.; Petrucelli, L.; Musiek, E.S. Microglial REV-ERBα regulates inflammation and lipid droplet formation to drive tauopathy in male mice. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, B.; Lee, J.W.; Hwang, S.; An, H.K.; Chung, K.M.; Park, Y.; Hong, J.; Kim, K.; Kim, E.K.; Choe, H.K; Yu, S.W. Presenilin 2 N141I mutation induces hyperactive immune response through the epigenetic repression of REV-ERBα. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhi, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, D. REV-ERBα Mitigates Astrocyte Activation and Protects Dopaminergic Neurons from Damage. J Mol Neurosci. 2024, 74, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ka NL, Park MK, Kim SS, Jeon Y, Hwang S, Kim SM, Lim GY, Lee H, Lee MO. NR1D1 Stimulates Antitumor Immune Responses in Breast Cancer by Activating cGAS-STING Signaling. Cancer Res, 3045; 83. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Tien, C.L.; Chan, R.E.; Sugi, K.; Fu, C.; Griffin, A.C.; Shen, Y.; Burris, T.P.; Liao, X.; Jain, M.K. REV-ERBα ameliorates heart failure through transcription repression. JCI Insight. 2017, 2, e95177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Song, S.; Qi, L.; Tien, C.L.; Li, H.; Xu, W.; Mathuram, T.L.; Burris, T.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L. REV-ERB is essential in cardiac fibroblasts homeostasis. Front Pharmacol. 8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Tsuchiya H, Zhang Y, Lee S, Liu C, Huang Y, Vargas GM, Wang L. REV-ERBα Activates C/EBP Homologous Protein to Control Small Heterodimer Partner-Mediated Oscillation of Alcoholic Fatty Liver. Am J Pathol. 2909. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.S.; Meijer, P.; Nazgiewicz, A.; Anderson, S.G.; Borthwick, L.A.; Bagnall, J.; Kitchen, G.B; Lodyga, M. ; Begley. N.; Venkateswaran, R.V.; Shah, R.; Mercer, P.F.; Durrington, H.J.; Henderson, N.C.; Piper-Hanley, K.; Fisher, A.J.; Chambers, R.C.; Bechtold, D.A.; Gibbs, J.E.; Loudon, A.S.; Rutter, M.K.; Hinz, B.; Ray, D.W.; Blaikley, J.F. The circadian clock protein REVERBα inhibits pulmonary fibrosis development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang., Q.; Sundar, I.K.; Lucas, J.H.; Park, J.G.; Nogales, A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Rahman, I. Wang. Q.; Sundar, I.K.; Lucas, J.H.; Park, J.G.; Nogales, A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Rahman, I. Circadian clock molecule REV-ERBα regulates lung fibrotic progression through collagen stabilization. Nat Commun, 1295; 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, D.; Gubin, D. The Impact of Physical Activity on the Circadian System: Benefits for Health, Performance and Wellbeing. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12, 9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).