Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

17 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Actigraphy

2.3. Complete Blood Count

2.4. Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ)

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Univariate Associations Between Circadian Parameters and Hematological Variables

| RBC | HGB | HCT | MCV | MCH | MCHC | RDW-CV | |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| MESOR | 0.098 | –0.024 | 0.024 | –0.081 | –0.137 | –0.023 | 0.088 |

| 24-h Amplitude | 0.190 | 0.176 | 0.146 | –0.079 | 0.010 | –0.007 | 0.051 |

| 24-h Acrophase | 0.088 | –0.153 | –0.086 | –0.069 | –0.274* | –0.024 | 0.226 |

| IV | 0.042 | 0.012 | 0.039 | 0.096 | –0.063 | 0.043 | 0.012 |

| IS | 0.111 | 0.116 | 0.120 | –0.021 | 0.013 | –0.135 | –0.104 |

| M10 | 0.132 | 0.052 | 0.055 | –0.142 | –0.094 | 0.023 | 0.076 |

| M10 Onset | 0.151 | –0.029 | 0.022 | –0.112 | –0.190 | –0.052 | 0.243 |

| L5 | –0.044 | –0.197 | –0.150 | –0.014 | –0.180 | –0.087 | 0.048 |

| L5 Onset | 0.069 | 0.005 | –0.011 | –0.093 | –0.058 | 0.039 | –0.051 |

| Relative Amplitude | 0.064 | 0.183 | 0.138 | –0.033 | 0.129 | 0.098 | –0.024 |

| Light Exposure (LE) / Blue Light Exposure (BLE) | |||||||

| LE MESOR | 0.161 | 0.189 | 0.199 | 0.118 | 0.030 | 0.084 | –0.049 |

| LE Amplitude | 0.128 | 0.248 | 0.234 | 0.157 | 0.137 | 0.084 | –0.084 |

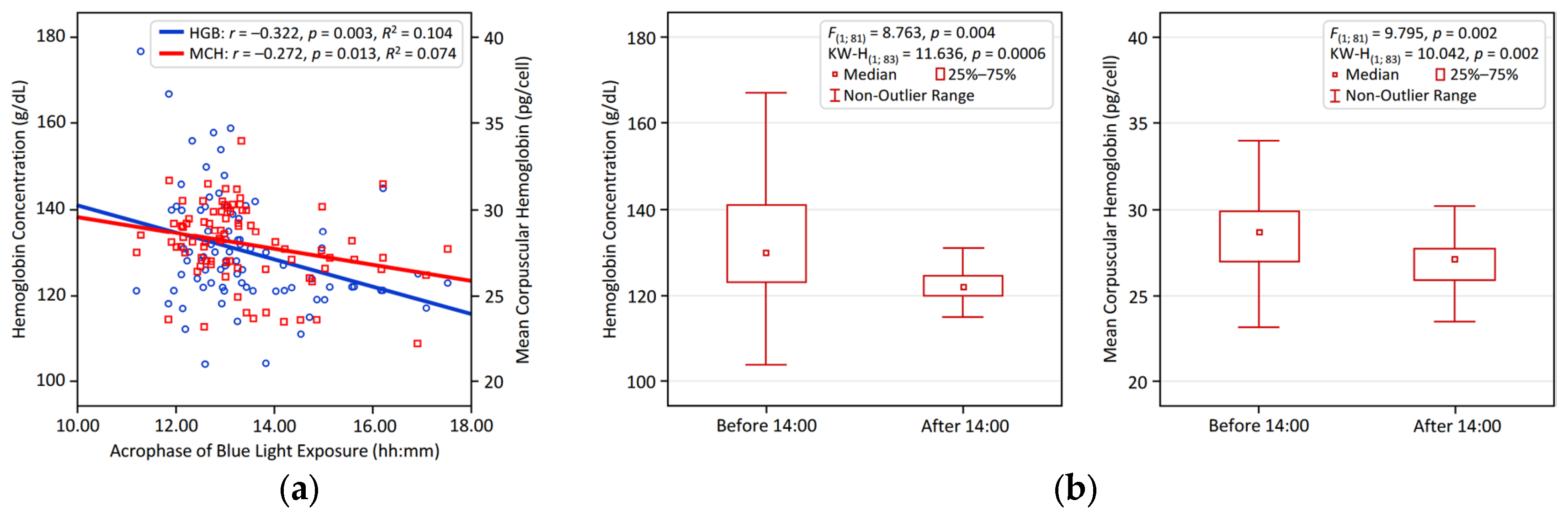

| LE Acrophase | –0.071 | –0.312* | –0.223 | –0.128 | –0.280* | –0.038 | 0.212 |

| BLE MESOR | 0.163 | 0.223 | 0.216 | 0.121 | 0.070 | 0.094 | –0.078 |

| BLE Amplitude | 0.155 | 0.279* | 0.253 | 0.143 | 0.148 | 0.095 | –0.114 |

| BLE Acrophase | –0.093 | –0.322* | –0.255 | –0.126 | –0.272* | –0.029 | 0.291* |

| BLE M10 | 0.155 | 0.244 | 0.223 | 0.122 | 0.103 | 0.105 | –0.089 |

| BLE M10 Onset | 0.029 | –0.162 | –0.111 | –0.229 | –0.202 | –0.001 | 0.077 |

| BLE L5 | 0.202 | 0.069 | 0.089 | –0.041 | –0.153 | –0.010 | 0.035 |

| BLE L5 Onset | 0.006 | –0.202 | –0.126 | –0.020 | –0.229 | –0.121 | 0.112 |

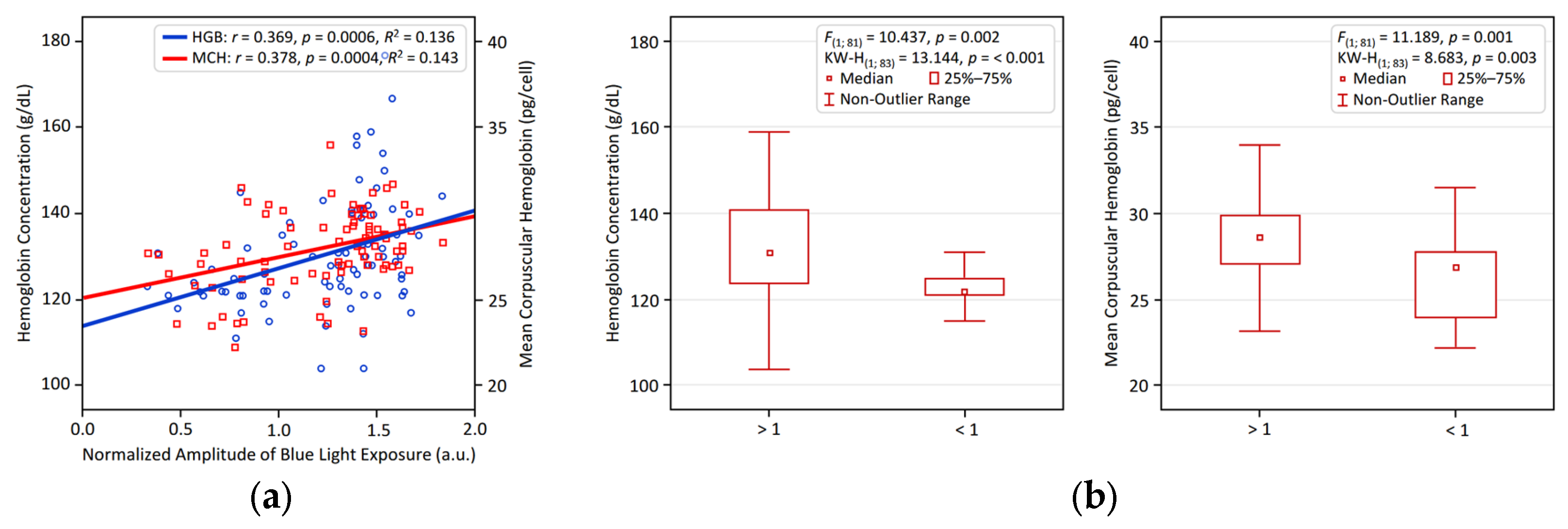

| BLE NA | 0.047 | 0.369* | 0.259 | 0.175 | 0.378* | 0.037 | –0.172 |

| Sleep | |||||||

| Bedtime | 0.045 | –0.225 | –0.154 | –0.133 | –0.314* | –0.063 | 0.184 |

| Wake time | 0.107 | –0.078 | 0.011 | –0.029 | –0.212 | –0.030 | 0.214 |

| Time in bed | 0.058 | 0.091 | 0.105 | 0.043 | 0.037 | 0.014 | 0.056 |

| Total sleep | 0.072 | 0.108 | 0.108 | 0.037 | 0.044 | 0.009 | 0.030 |

| Sleep efficacy | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.004 | –0.004 | 0.017 | –0.046 | –0.095 |

| WASO | –0.056 | –0.056 | 0.008 | 0.030 | –0.024 | 0.028 | 0.138 |

| Chronotype Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) Score | |||||||

| MEQ Score | –0.020 | 0.051 | 0.010 | 0.074 | 0.100 | –0.032 | –0.047 |

3.3. Multivariate Associations Between Circadian Parameters and Hematological Variables

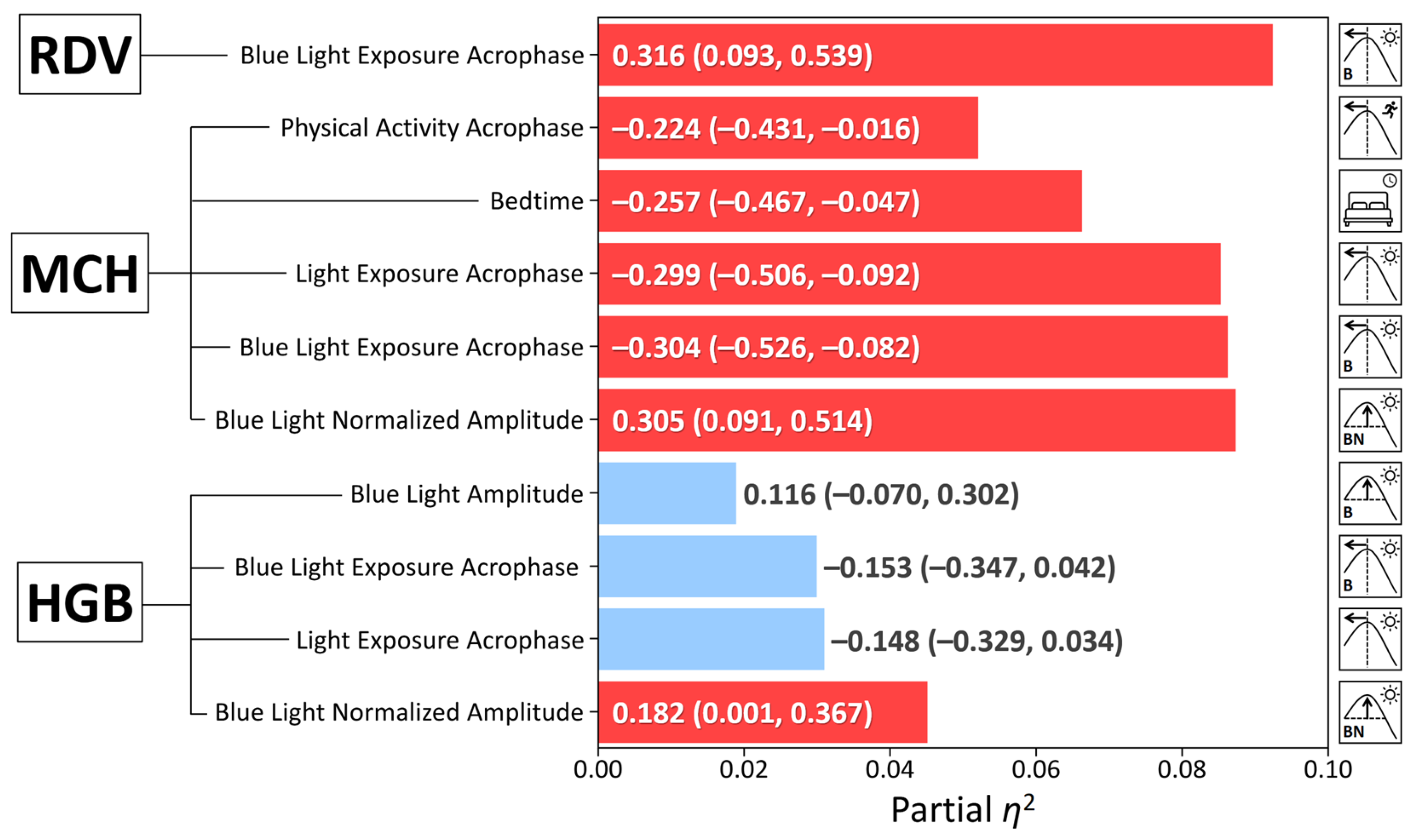

| Dependent Variable | Predictor | β (95% CI) | p-value | Partial η² |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | Sex | –0.491(–0.683, –0.299) | <0.001 | 0.247 |

| BLE NA | 0.206(0.012, 0.400) | 0.037 | 0.054 | |

| Age | 0.028 (–0.154, 0.209) | 0.763 | 0.001 | |

| Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin | BLE NA | 0.377(0.159, 0.595) | < 0.001 | 0.130 |

| Age | –0.174 (–0.378, 0.032) | 0.096 | 0.035 | |

| Sex | 0.060 (–0.156, 0.277) | 0.580 | 0.004 | |

| Red Cell Distribution Width – CV | BLE Acrophase | 0.316(0.093, 0.539) | 0.006 | 0.092 |

| Age | 0.205 (–0.005, 0.416) | 0.055 | 0.046 | |

| Sex | 0.023 (–0.245, 0.199) | 0.839 | < 0.001 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaparro, C.M.; Suchdev, P.S. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2019, 1450, 15–31. [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz-Góngora, V.; Villalpando, S.; Shamah-Levy, T. Overview of trends in anemia and iron deficiency in the Mexican population from 1999 to 2018-19. Food Nutr Bull 2024, 45, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Lucas, D.; Battista, M.; Frenette, P.S. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature 2008, 452, 442–447. [CrossRef]

- Laerum, O.D. The haematopoietic system. In Chronobiology and Chronomedicine: From Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms to Whole Body Interdigitating Networks; Cornelissen, G., Hirota, T., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: 2024; pp. 304–322.

- O’Neill, J.S.; Reddy, A.B. Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature 2011, 469, 498–503. [CrossRef]

- Beale, A.D.; Labeed, F.H.; Kitcatt, S.J.; O’Neill, J.S. Detecting circadian rhythms in human red blood cells by dielectrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2482, 255–264. [CrossRef]

- Beale, A.D.; Hayter, E.A.; Crosby, P.; Valekunja, U.K.; Edgar, R.S.; Chesham, J.E.; Maywood, E.S.; Labeed, F.H.; Reddy, A.B.; Wright, K.P. Jr; Lilley, K.S.; Bechtold, D.A.; Hastings, M.H.; O’Neill, J.S. Mechanisms and physiological function of daily haemoglobin oxidation rhythms in red blood cells. EMBO J 2023, 42, e114164. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Weinert, D.; Stefani, O.; Otsuka, K.; Borisenkov, M.; Cornelissen, G. Wearables in chronomedicine and interpretation of circadian health. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15, 327. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Stefani, O.; Cornelissen, G. Light hygiene for circadian health: a molecular perspective. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 39097. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Boldyreva, J.; Stefani, O.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Danilova, L.; Shigabaeva, A.; Cornelissen, G.; Weinert, D. Higher vulnerability to poor circadian light hygiene in individuals with a history of COVID-19. Chronobiol Int 2025, 42, 133–146. [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.A.; Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110.

- Gubin, D.; Danilenko, K.; Stefani, O.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Markov, A.; Petrov, I.; Voronin, K.; Mezhakova, M.; Borisenkov, M.; Shigabaeva, A.; Yuzhakova, N.; Lobkina, S.; Petrova, J.; Malyugina, O.; Weinert, D.; Cornelissen, G. Light environment of Arctic solstices is coupled with melatonin phase-amplitude changes and decline of metabolic health. J Pineal Res 2025a, 77, e70023. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Danilenko, K.; Stefani, O.; Markov, A.; Petrov, I.; Voronin, K.; Mezhakova, M.; Borisenkov, M.; Shigabaeva, A.; Boldyreva, J.; Petrova, J.; Alkhimova, L.; Weinert, D.; Cornelissen, G. Timing and amplitude of light exposure, not photoperiod, predict blood lipids in Arctic residents: a circadian light hypothesis. Biology (Basel) 2025D, 14, 799. [CrossRef]

- Gubin, D.; Kolomeichuk, S.; Danilenko, K.; Stefani, O.; Markov, A.; Petrov, I.; Voronin, K.; Mezhakova, M.; Borisenkov, M.; Shigabaeva, A.; Boldyreva, J.; Petrova, J.; Weinert, D.; Cornelissen, G. Light exposure, physical activity, and indigeneity modulate seasonal variation in NR1D1 (REV-ERBα) expression. Biology (Basel) 2025, 14, 231. [CrossRef]

- Sennels, H.P.; Jørgensen, H.L.; Hansen, A.L.; Goetze, J.P.; Fahrenkrug, J. Diurnal variation of hematology parameters in healthy young males: the Bispebjerg study of diurnal variations. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2011, 71, 532–541. [CrossRef]

- Hilderink, J.M.; Klinkenberg, L.J.J.; Aakre, K.M.; de Wit, N.C.J.; Henskens, Y.M.C.; van der Linden, N.; Bekers, O.; Rennenberg, R.J.M.W.; Koopmans, R.P.; Meex, S.J.R. Within-day biological variation and hour-to-hour reference change values for hematological parameters. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017, 55, 1013–1024. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, R.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Koike, N.; Umemura, Y.; Inokawa, H.; Ono, R.; Inoue, M.; Sasawaki, Y.; Grieten, T.; Okubo, N.; Ikoma, K.; Fujiwara, H.; Kubo, T.; Yagita, K. REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ function as key factors regulating mammalian circadian output. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10171. [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, S.; Stayrook, K.R.; Huang, P.; Rogers, P.M.; Nosie, A.K.; McClure, D.B.; Burris, L.L.; Khorasanizadeh, S.; Burris, T.P.; Rastinejad, F. Identification of heme as the ligand for the orphan nuclear receptors REV-ERBalpha and REV-ERBbeta. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2007, 14, 1207–1213. [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wu, N.; Lazar, M.A. Nuclear receptor Rev-erbalpha: a heme receptor that coordinates circadian rhythm and metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal 2010, 8, e001. [CrossRef]

- Simcox, J.A.; Mitchell, T.C.; Gao, Y.; Just, S.F.; Cooksey, R.; Cox, J.; Ajioka, R.; Jones, D.; Lee, S.H.; King, D.; Huang, J.; McClain, D.A. Dietary iron controls circadian hepatic glucose metabolism through heme synthesis. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1108–1119. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ren, Q.; Wang, X.; Bai, H.; Tian, D.; Gao, G.; Wang, F.; Yu, P.; Chang, Y.Z. Cellular iron depletion enhances behavioral rhythm by limiting brain Per1 expression in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14592. [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.; Silva, F.; Esteves, F.; Costa, S.; Slezakova, K.; Alves, M.; Pereira, M.; Teixeira, J.; Morais, S.; Fernandes, A.; Queiroga, F.; Vaz, J. The impact of sleep on haematological parameters in firefighters. Clocks Sleep 2024, 6, 291–311. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, M.; Qian, H.; Song, Q.; Liu, B. Sleep behaviors modify the association between hemoglobin concentration and respiratory infection: a prospective cohort analysis. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1638819. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Lin, W. Effects of exercise training on red blood cell production: implications for anemia. Acta Haematol 2012, 127, 156–164. [CrossRef]

- Caimi, G.; Carlisi, M.; Presti, R.L. Red blood cell distribution width, erythrocyte indices, and elongation index at baseline in a group of trained subjects. J Clin Med 2023, 13, 151. [CrossRef]

- Mairbäurl, H. Red blood cells in sports: effects of exercise and training on oxygen supply by red blood cells. Front Physiol 2013, 4, 332. [CrossRef]

- Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; van Assen, S. Exercise-induced anaemia: a forgotten cause of iron deficiency anaemia in young adults. Br J Gen Pract 2015, 65, 268–269. [CrossRef]

- Cichoń-Woźniak, J.; Dziewiecka, H.; Ostapiuk-Karolczuk, J.; Kasperska, A.; Gruszka, W.; Basta, P.; Skarpańska-Stejnborn, A. Effect of baseline ferritin levels on post-exercise iron metabolism in male elite youth rowers. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 23440. [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.K.; Park, J.; Cho, S.I. Association between depression, anemia and physical activity using isotemporal substitution analysis. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2236. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19.30 ± 1.51 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 21.76 ± 3.72 |

| Sex (male/female) | 23/62 |

| Red blood cells (RBC) (10¹²/L) | 4.68 ± 0.42 |

| Hemoglobin concentration (HGB) (g/dL) | 130.3 ± 12.9 |

| Hematocrit (HCT) (%) | 40.15 ± 3.52 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) (pg/cell) | 27.99 ± 2.22 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (fL) | 85.01 ± 9.87 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (g/D) | 321.9 ± 33.7 |

| Red cell distribution width – CV (RDW-CV) (%) | 13.12 ± 1.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).