1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) computation is undergoing a transformative shift, with a significant movement towards edge computing. By 2025, it is projected that 75% of enterprises will adopt edge-based computation to leverage its advantages in latency reduction and localized processing [

1]. With billions of devices connected to the internet through various protocols, the volume of generated and transmitted data has grown exponentially. However, this proliferation of internet-connected devices has escalated concerns about system integrity and data security. Consequently, real-time learning of network packets for intrusion detection has become essential for ensuring uninterrupted and secure network operations [

2].

Network intrusion detection systems are broadly categorized into two types: (i) signature-based systems and (ii) anomaly-based systems [

3]. Signature-based systems detect threats by comparing incoming packets against a database of known signatures using state machine algorithms such as Snort, Sagan, and Suricata [

4]. However, these systems are ineffective against unknown or zero-day attacks. In contrast, anomaly-based systems evaluate the similarity between incoming packets and previously known packets to identify potential threats. These systems employ statistical models, finite state machines, or Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [

5]. ANNs are particularly effective due to their ability to dynamically adapt to new knowledge by adjusting synaptic parameters, making them a robust tool for anomaly detection in dynamic network environments.

ANNs are further classified based on their training methodologies, such as supervised and unsupervised learning [

6]. Supervised neural networks, like Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), require labeled data and excel at classifying known patterns. However, their reliance on labeled data limits their suitability for real-time training, where data labels may not be readily available. In contrast, unsupervised neural networks do not require labeled data, making them ideal for real-time and adaptive applications.

Traditionally, training ANN architectures demands high-power computing platforms, such as GPUs in data centers, which come with substantial memory and energy requirements [

7]. Transferring data to these centralized facilities for training introduces latency, memory overhead, and high power consumption, all of which are significant challenges in the edge AI paradigm. Additionally, deploying GPU-based training systems on resource-constrained edge or IoT devices is impractical.

As edge computing becomes increasingly prevalent, the security of edge devices has emerged as a critical concern. To address these challenges, there is a pressing need for AI training platforms capable of performing real-time data processing and online learning directly on local devices. These platforms enable personalized and secure applications while reducing reliance on centralized, energy-intensive facilities [

8].

Low-power AI neural network accelerators present a promising solution to these challenges. However, most commercially available AI accelerators are designed for inference tasks only, limiting their applicability for on-device training [

9]. Furthermore, CMOS technology is nearing its physical and performance limits, with Von Neumann computing architectures facing bottlenecks due to Moore’s law, the memory wall, and the heat wall [

10]. Non-Von Neumann computing paradigms, such as neuromorphic on-chip learning, offer a viable alternative for implementing neural network systems with on-device training capabilities. In this paradigm, data is processed and stored in the same location, eliminating the need for extensive data movement. This approach, known as Processing-In-Memory (PIM), significantly enhances computational efficiency [

10].

Among emerging technologies, memristors have garnered significant attention as a fundamental building block for neuromorphic computing systems. Memristors are nanoscale, non-volatile memory devices that enable non-Von Neumann computing and on-chip learning without off-chip memory access [

10,

11]. These devices, fabricated in crossbar architectures, perform multiply-accumulate operations—a dominant function in neural networks—efficiently and in parallel within the analog domain [

11]. The small feature size of memristors enables the development of high-density neuromorphic systems with exceptional computational efficiency [

10].

This article focuses on the design and implementation of a neural network-based intrusion and anomaly detection system. The key contributions are as follows:

Development of an ultra low-power memristor-based unsupervised on-chip and online learning system for edge security applications.

Resolution of circuit challenges for implementing online threshold computation to support real-time learning.

Design and simulation of a Euclidean Distance computation circuit, integrated into the memristor-based neuromorphic system for unsupervised online training.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the dataset used in the experiment.

Section 3 discusses the unsupervised learning approach for anomaly detection.

Section 4 details the memristor-based implementation for the on-chip and online learning system.

Section 5 provides an overview of related works, while

Section 6 elaborates on the memristor-based online learning system.

Section 7 explains the threshold computing circuits, and

Section 8 presents SPICE simulation results for these circuits.

Section 9 showcases the results and analysis of online learning. Finally,

Section 10 concludes the paper.

2. Network Dataset

NSL-KDD dataset is a popular benchmark for validating machine learning and neural network models [

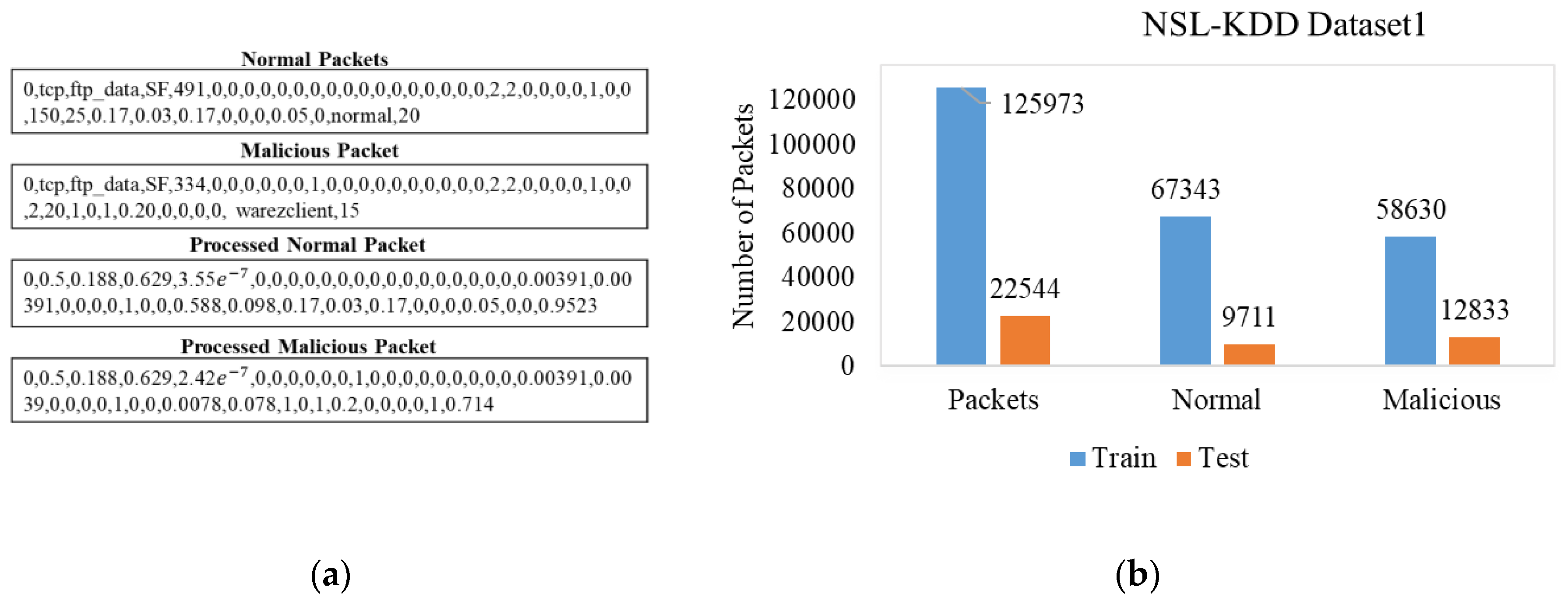

12]. The dataset has one normal class and four malicious classes (DoS, Probe, R2L, and U2R). The dataset is separated into training and testing categories, and they contain 125673 and 22544 packets, respectively. A sample of normal and malicious network data packets is presented in

Figure 1a. Both datasets consist of normal and malicious packages. Nevertheless, the test dataset contains 17 more malicious data types that are not present in the training dataset. The distribution of normal and malicious packets with their variants is presented in

Figure 1b.

These new categories remain unknown datatypes to supervised learning networks as they were not present in the training session. However, the anomaly detection system can handle these unknown categories as a zero-day attack by comparing the sequence with normal or known packets.

Each packet has 43 attributes with binary, alphanumeric, and nominal values. The nominal attributes are the protocol, service, flag, and attach types and occupied 2

nd to 4

th and 42

nd positions. At first, the nominal values are replaced with integers and then normalized the attributes to bound between 0 and 1. Examples of network packets before and after normalizations are presented in

Figure 1a.

3. Unsupervised Learning

An unsupervised neural network learns the input feature space without knowing the identity or label of the sample. The purpose of unsupervised learning is to learn the underlying structure of the dataset and cluster that data according to the similarity measures.

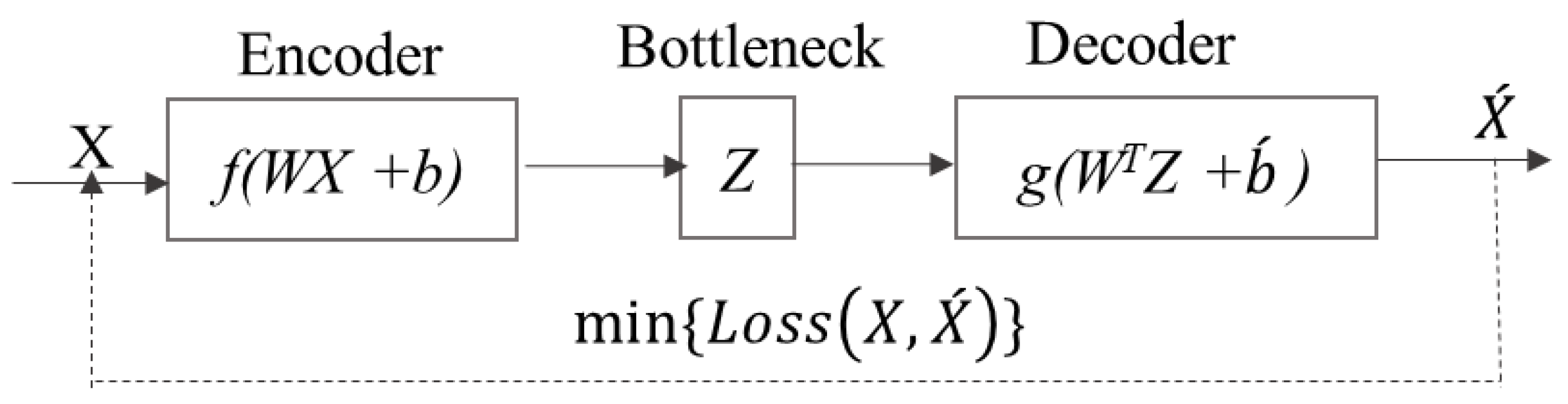

The conceptual diagram of a simples vanilla autoencoder is presented in

Figure 2. In

Figure 2, X is the input feature space fed to the input layer. The encoder section learns to compress the sample into lower-dimensional latent feature space at the Z bottleneck layer. On the other hand, the decoder section learns to regenerate the input feature space at the output,

. Once the AE is trained, it becomes a very efficient machine to regenerate the known classes and discriminate with the unknown inputs [

13].

The encoder and decoder transformation of an AE can be denoted by

and

,

and

. For instance, if we consider the simplest vanilla autoencoder [

14] with a single hidden layer (

Z) with input and output layers as in

Figure 2. The mathematical expression for the layer-wise signal propagation can be expressed as in Eq. (1-2).

Here,

b's are biasing to the neuron,

f is the activation function, and

n's are the number of neurons in any layer. The inputs,

and,

are the elements in latent space

The model is trained by backpropagation of error [

14] to minimize the reconstruction error or loss function,

. The same technique can be applied for layer wise computation for autoencoders with multiple hidden layers as presented in

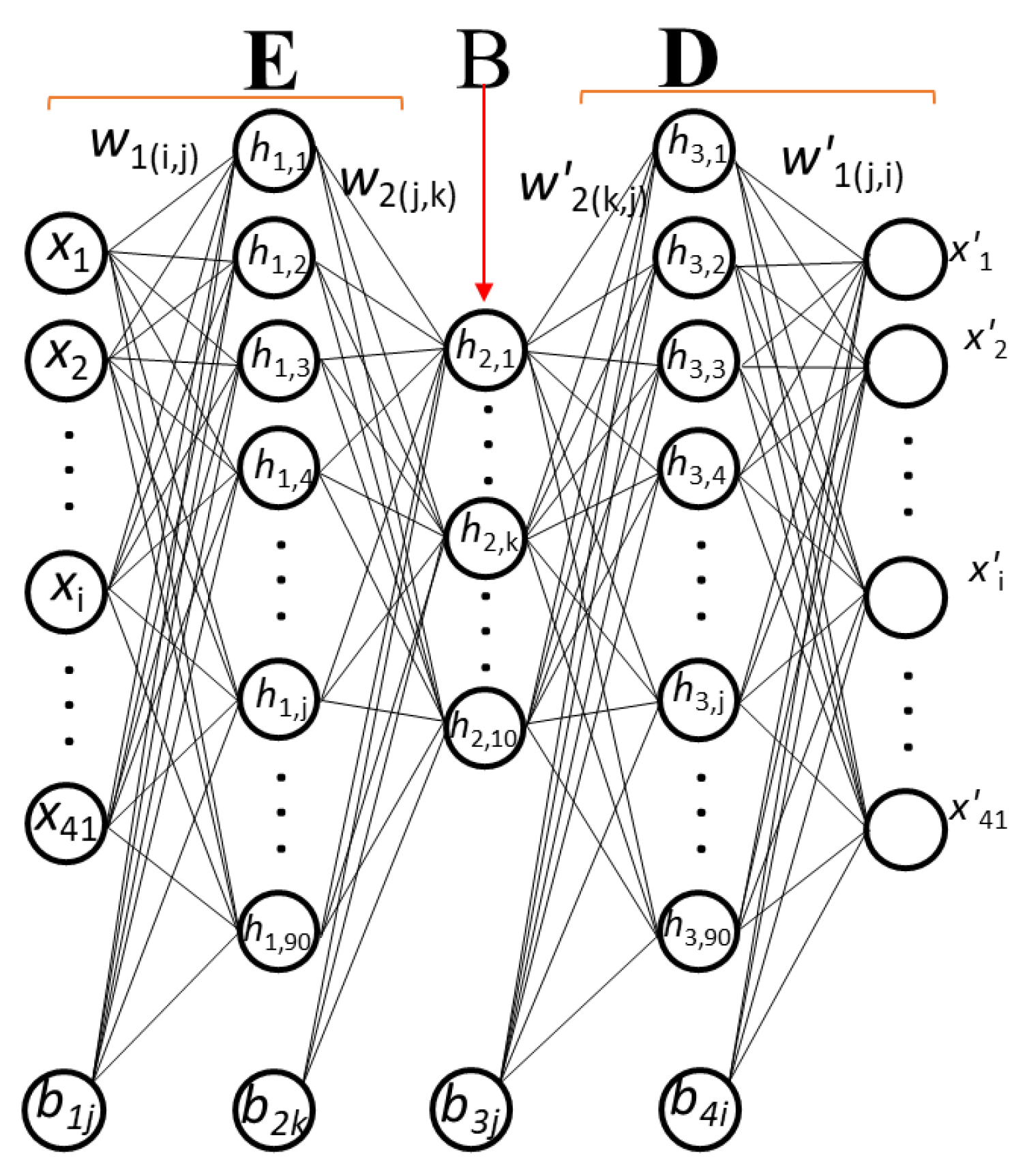

Figure 3. Eq. (3-6) represent system of equations for layer-wise implementation.

4. Memristor Implementation

4.1. Memristor Neuron Circuit

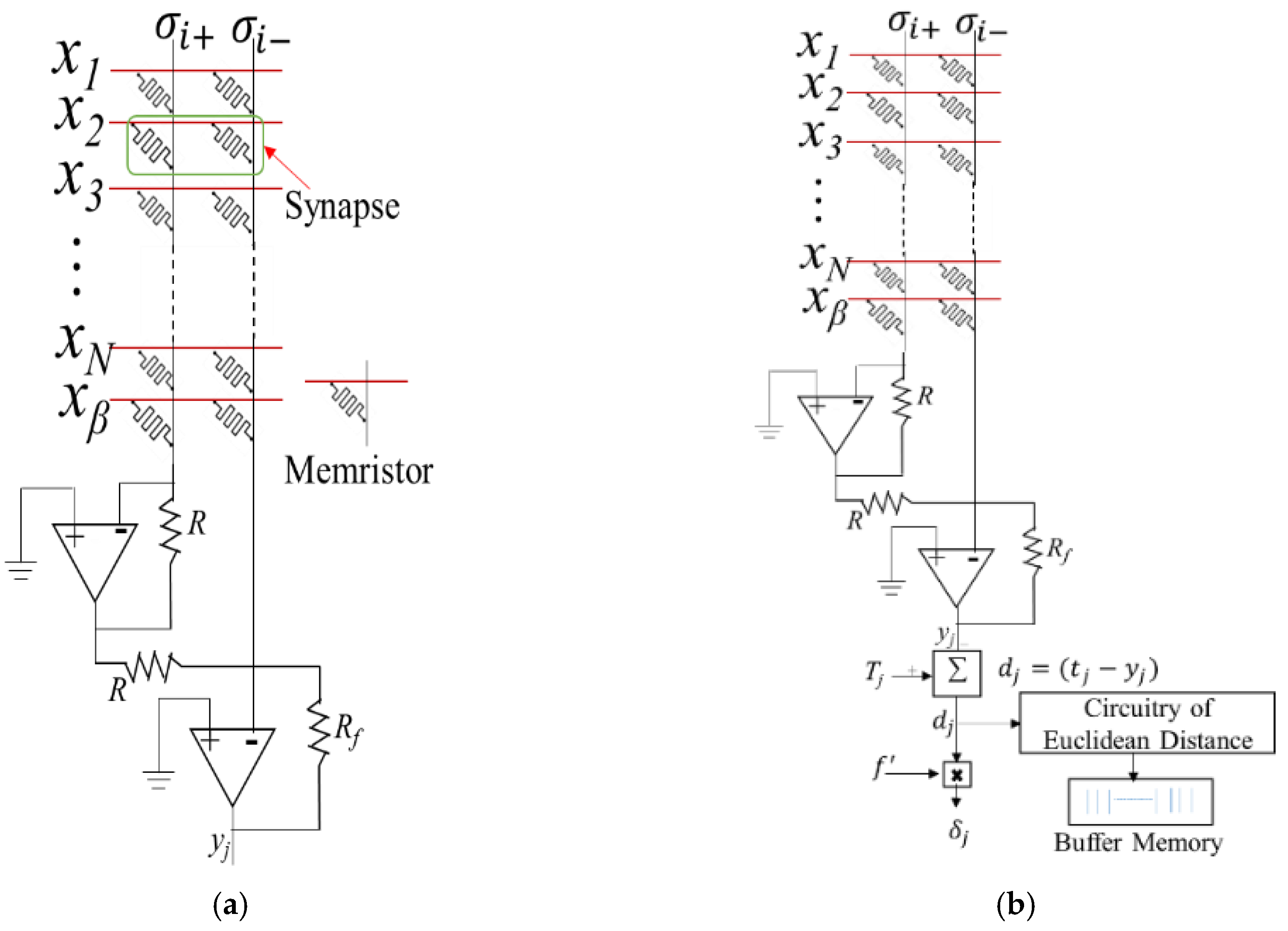

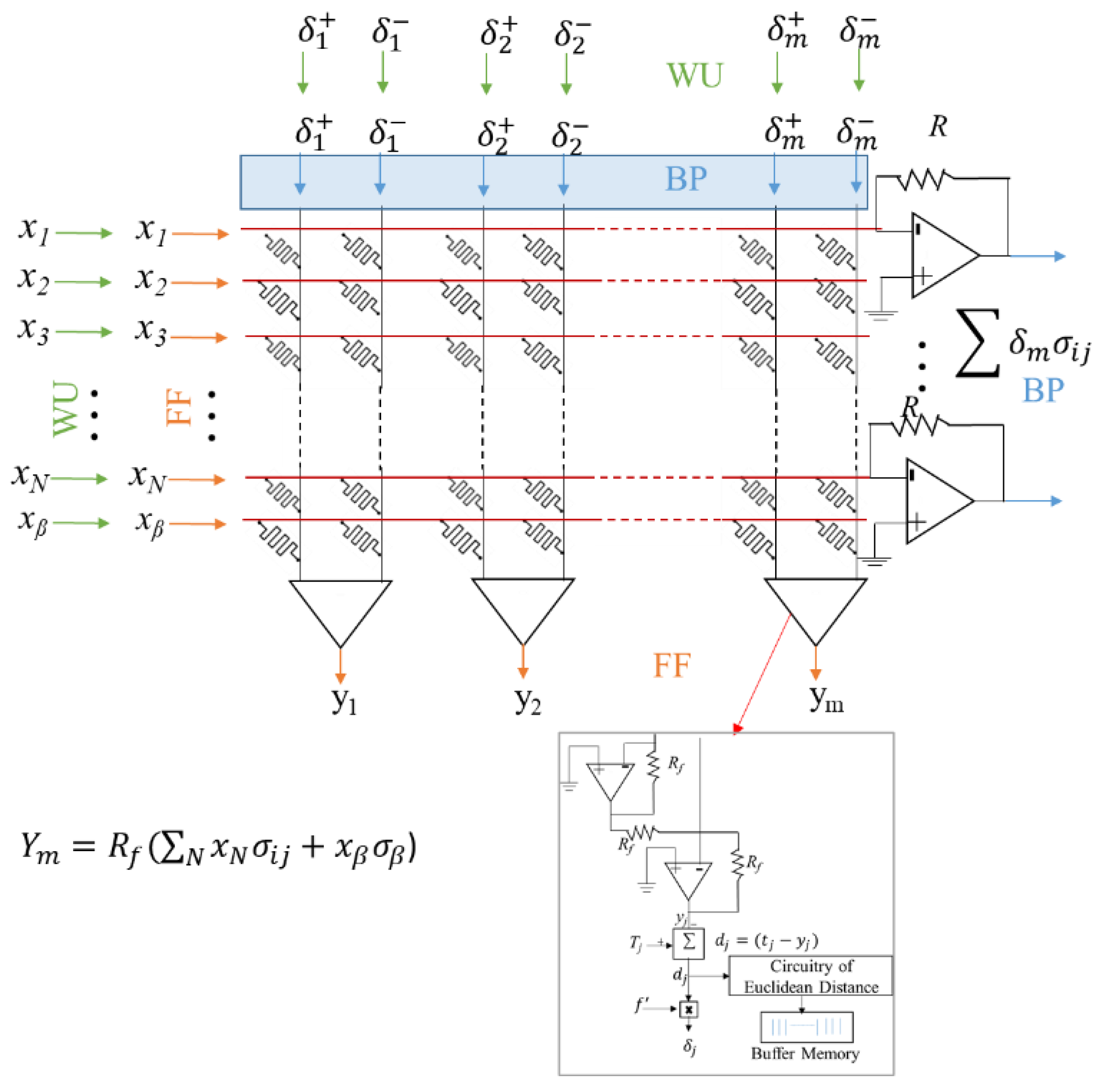

Figure 4 (a, b) presents a memristor-based neuron circuit consisting of

N inputs (

X) and one bias (

β). The output neuron is connected to the error generation circuits (see

Figure 4(b)). The Euclidean distance computing circuitry is implemented for online learning experiments to compute the threshold in real time. In the neuron circuit, the synaptic element is represented by a pair of memristor devices along the row, as presented in

Figure 4. The synaptic weight can be negative (

) or positive (

) based on the magnitude of the conductance of memristor pairs. The synapse receives the inputs as an analog voltage pulse, multiplies with the synaptic conductance, and gives a resultant current that flows along the common column. The total current is sensed at the bottom of the neuron circuit as in Eq. 7, and the output voltage from the op-amp circuits is the resultant voltage

Ym. The neuron circuit creates approximated sigmoid activation (Eq.9) in op-amp circuits where the power rail of the op-amp is connected to

VDD=1 V and

VSS=0 V.

4.2. Crossbar Training

The memristor-based crossbar circuit is trained in the full analog domain. The forward propagation is performed the same way the inference is computed in multilayered neural networks. The training samples are applied to the input nodes of the neural networks, and it produces vector-matrix multiplication and gives a neuronal sum at the output nodes. An error backpropagation process [

15,

16] is utilized in the training process.

For training the autoencoder circuits, transposable arrays are designed where the input can be applied from row-wise and column-wise. The error (

) is generated from the error generation circuit for each input sample, as shown in

Figure 5. The error is backpropagated to the same crossbar circuit but from the transposed direction and produce a resulted sum

.

The amount is multiplied with the derivation of neuron activation to compute the layer error gradient. The weight update of the neuron is performed by based on the product of activation and error gradient (

) of each layer. For weight update, pulses are produced with varible heights and widths. The height is modulated by the input activations and the widht is shaped by the product of learning rate and error gradient (

) as discussed in [

10]. The detailed training steps are presented as pictorial form in

Figure 5 with a transposable crossbar array circuits and peripheral details. The Euclidean distance computing module is necessary for determining the anomalies in the computer networks. This module is embedded in the online learning process to calculate the threshold. Analog computations are severely affected by noise from different pieces of analog circuits, such as ADC/DAC, Op-Amps and the memristor array. The noise is introduced in the circuit simulation during weight updates as described in Eq. 10, where

is weight update amount and

is random noise.

5. Online Learning and Related Works

5.1. Online Learning Memristor Neuron Circuit

Online learning, akin to continual lifelong learning [

17], addresses the challenge of sequential data streams, in contrast to the batch learning approach commonly used in deep learning training. In online learning, the system learns from a continuous sequence of incoming data without requiring pre-trained knowledge or a fixed dataset. As new samples arrive, the network updates its parameters in real time. However, a major drawback of this approach is catastrophic forgetting [

18], where the model tends to forget previously learned information when new data is introduced. This phenomenon significantly reduces model performance, as older knowledge is overwritten by new data.

State-of-the-art deep learning algorithms have demonstrated superior performance in classification tasks, especially in large-scale data processing. However, these algorithms assume that all possible data types are included in the training set. When trained sequentially, the model experiences a decline in accuracy due to catastrophic forgetting. To mitigate this issue, an effective learning system must possess the ability to acquire new knowledge while preserving previously learned information, thus overcoming the challenge of catastrophic forgetting

5.2. Related Works on Online Learning

Real-world computational units often encounter continuous streams of information, necessitating real-time learning systems capable of handling dynamic data distributions and learning multiple tasks. Various machine learning and deep learning algorithms have been proposed for online learning applications. This section highlights some relevant systems.

Continuous and lifelong learning, a key area in online learning, has been an active research frontier for decades, with numerous algorithms developed for this purpose [

19]. S. A. Rebuffi et al. introduced the iCARL algorithm, a supervised lifelong online learning approach that can identify new categories and incrementally learn classes, though it requires storing samples of all classes for fine-tuning [

20]. M. Pratama et al. proposed the evolving denoising autoencoder (DEVDAN) for online incremental learning on non-stationary data streams, which adapts by generating, pruning, and learning hidden nodes on the fly [

21]. S. S. Sarwar et al. presented a deep CNN (DCNN) for incremental learning, addressing catastrophic forgetting by partially sharing trained knowledge and using new branches for new classes [

22]. Hierarchical temporal memory (HTM) has been applied for online learning and anomaly detection in various domains, including 3D printing and video anomaly detection [

23,

24]. Extreme learning machines (ELM) and Adaptive Resonance Theory (ART) algorithms have been explored for dynamic modeling, anomaly detection, and intrusion detection [

26,

27,

28,

30,

31].

While most of these systems are implemented in software, there are a few hardware implementations of online learning algorithms with emerging resistive memory devices. ELM has been implemented in both spiking [

33] and non-spiking [

34] neuromorphic systems, and ART in FPGA [

35] and memristor-based systems [

30]. Autoencoders have been implemented in FPGA for unsupervised learning, such as detecting new physical phenomena in the large hadron collider [

36]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no one has previously implemented unsupervised autoencoders in memristor neuromorphic systems for online learning and anomaly detection. This work presents such an implementation, detailing the supporting circuits for online threshold computation and neural network optimization [

37,

38].

5.3. Online Learning Systems

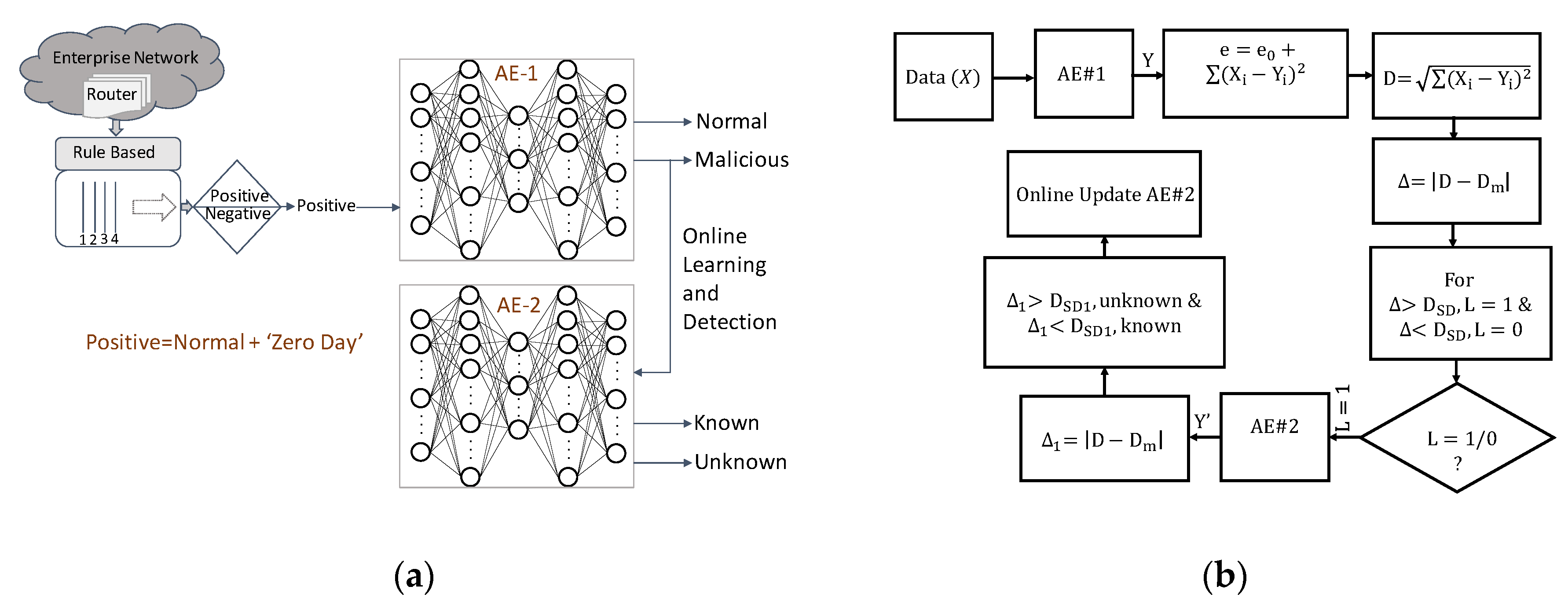

The online learning system in this study is presented in

Figure 6a with conceptual diagram. The system is developed as a complementary of the existing rule-based IDS system. AE-1 is a pretrained autoencoder that is trained on normal packets. AE-2 is implemented to learn only on malicious packets. The malicious packets are coming from AE-1 in real-time.

6. Memristor Based Online Learning Systems

Unsupervised autoencoders are implemented in memristor based neuromorphic architecture for anomaly detection applications. The system has two main parts, pretrained section, and the online learning section. In pretrained section, the pretrained autoencoder detects potential malicious packets and directs them to the second autoencoder where the AE-2 learns on the malicious packets only. The flowchart of the online learning system is presented in

Figure 6b. While learning about the malicious packets, the system can identify any new potential threat to the network, known as the zero-day attack, which is yet unfamiliar or an anomaly. However, with the repetitive appearance of the unknown packets become familiar to the network and become part of the known malicious packets to the system.

For online anomaly detection, the system needs to compute Euclidean distance for every network packet coming to AE-2. The ED is computed between the input and output feature vector of the network packets to determine the threshold for detecting the known or unfamiliar malicious packets. Online learning is taking place on edge devices, so there is no high-power floating processor to compute ED. In this work, we have proposed a detailed circuitry for computing ED in real-time for optimizing the network and computing the threshold.

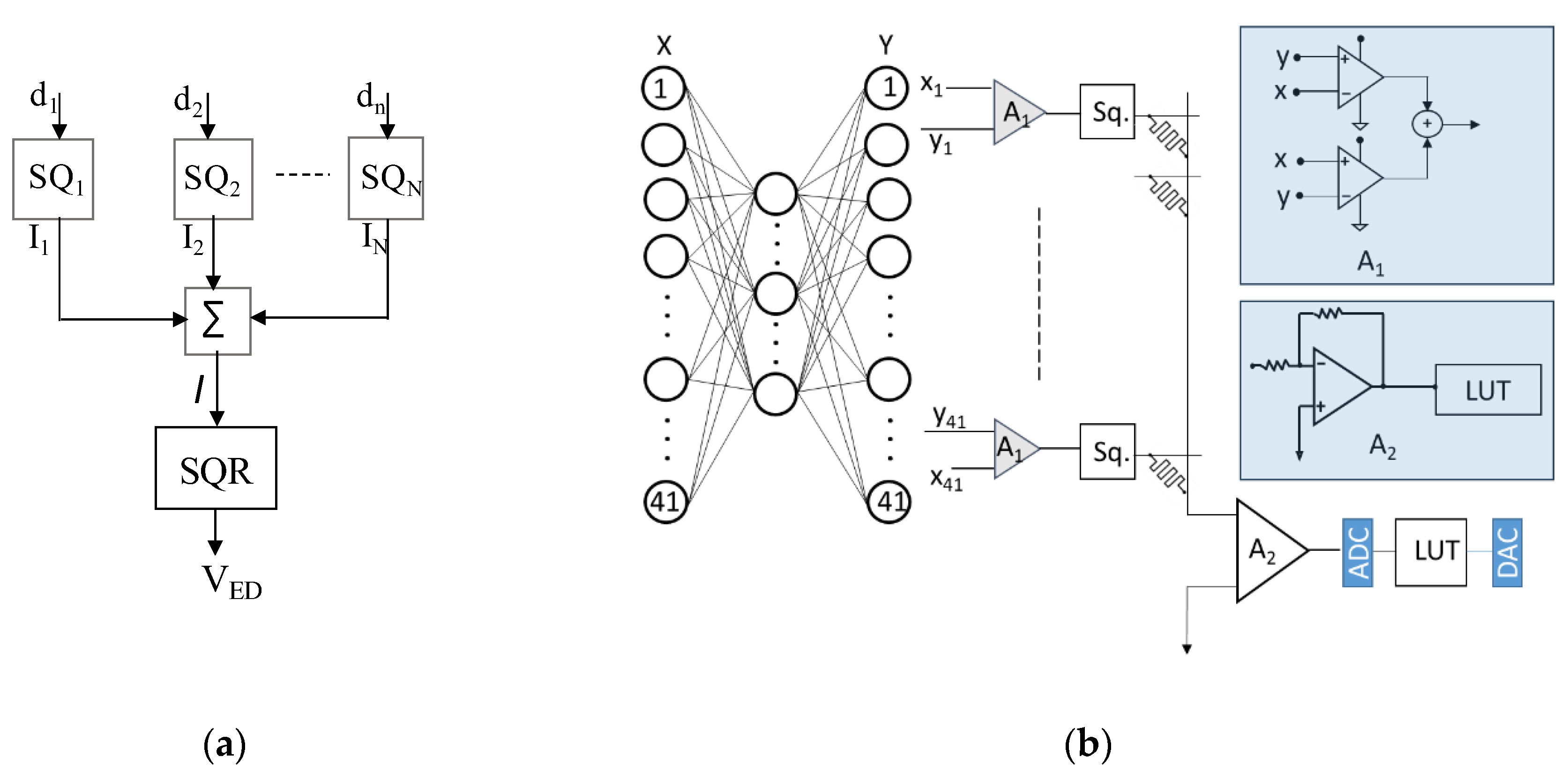

In online learning, the system needs to update the threshold for network anomaly detection as it continuously learns and optimizes the network parameters for detecting the newly learned packets and the unknown packets. The threshold is computed using a series of analog squaring circuits that able to compute reconstruction error at in a single shot. The block diagram of the Euclidean distance computing block is presented in

Figure 7a. The differences between the input vector and generated output vector are

d1, d2, ……, dn fed into the analog squaring circuit. A summing amplifier accumulates the output currents of the squaring circuits. The output of the summing amplifier is digitized through an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and stored as the equivalent Euclidean distance in Look Up Table (LUT), a peripheral memory module. After each learning cycle, the stored data is used to compute the threshold as the standard deviation in the digital system and then converted the result into an analog equivalent voltage signal for anomaly detection as described in

Figure 7b.

7. Analog Threshold Computing

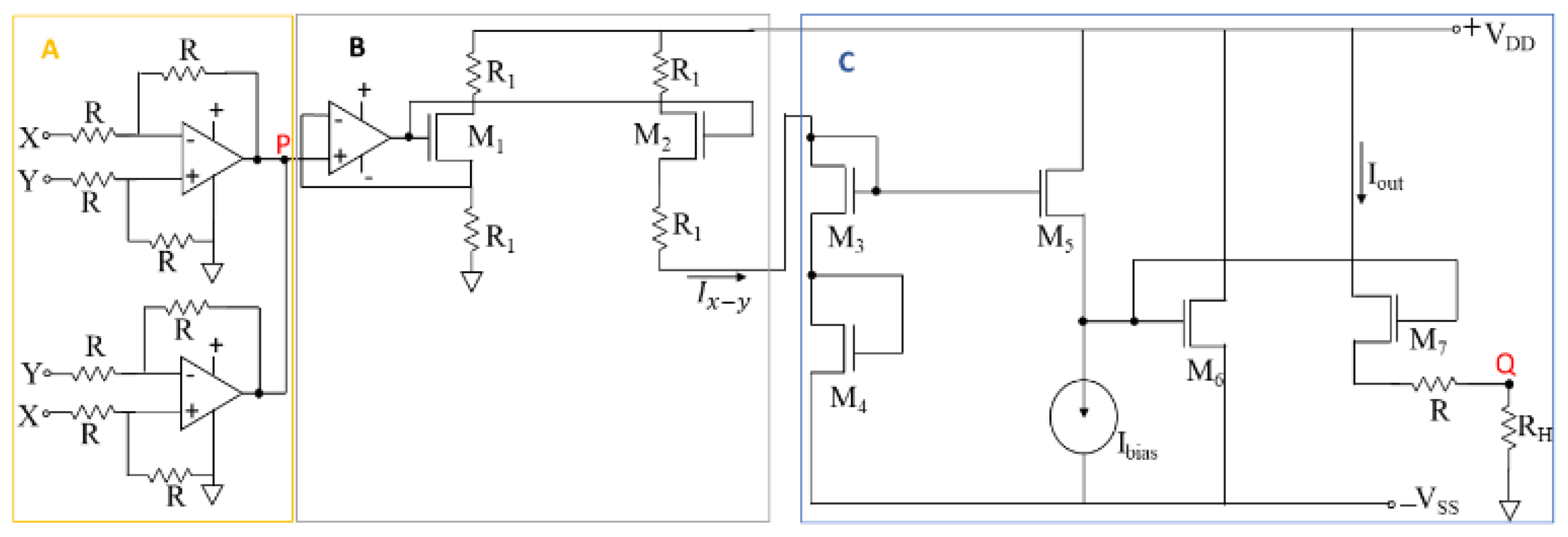

The analog squaring circuits are integral to computing the training error as the Euclidean distance for online training. Each incoming sample’s distance is digitized using a low-precision ADC, stored in peripheral memory, and periodically used to update the anomaly detection threshold. The distance computing circuit, shown in Figure 8, is divided into three main components: (A) differential voltage computation, (B) voltage-to-current conversion, and (C) the squaring section.

Section A computes the absolute L1 norm (Manhattan distance) between the input and output vectors of the autoencoder circuit, providing the result at node P. Section B converts the input voltage Vp into a proportional current. Section C calculates the square of the Manhattan distance using the current input (Ix-y).

In the online training of the NSL-KDD network packet dataset, the system requires 41 squaring circuits to efficiently perform training and anomaly detection. The system can also employ time-multiplexing techniques for enhanced functionality. All 41 squaring circuits compute the Euclidean distance simultaneously. After computation, the output current is passed through transistor M7, where the current Iout generates a voltage drop at the output node Q. The voltage outputs from all squaring circuits are then accumulated using a summing amplifier and stored in a look-up table (LUT). The square root of the accumulated voltage values is used to determine the actual Euclidean distance.

The circuit presented in

Figure 8 is implemented in SPICE simulation with actual device parameters to get the realistic characteristics of the training and anomaly detection performance.

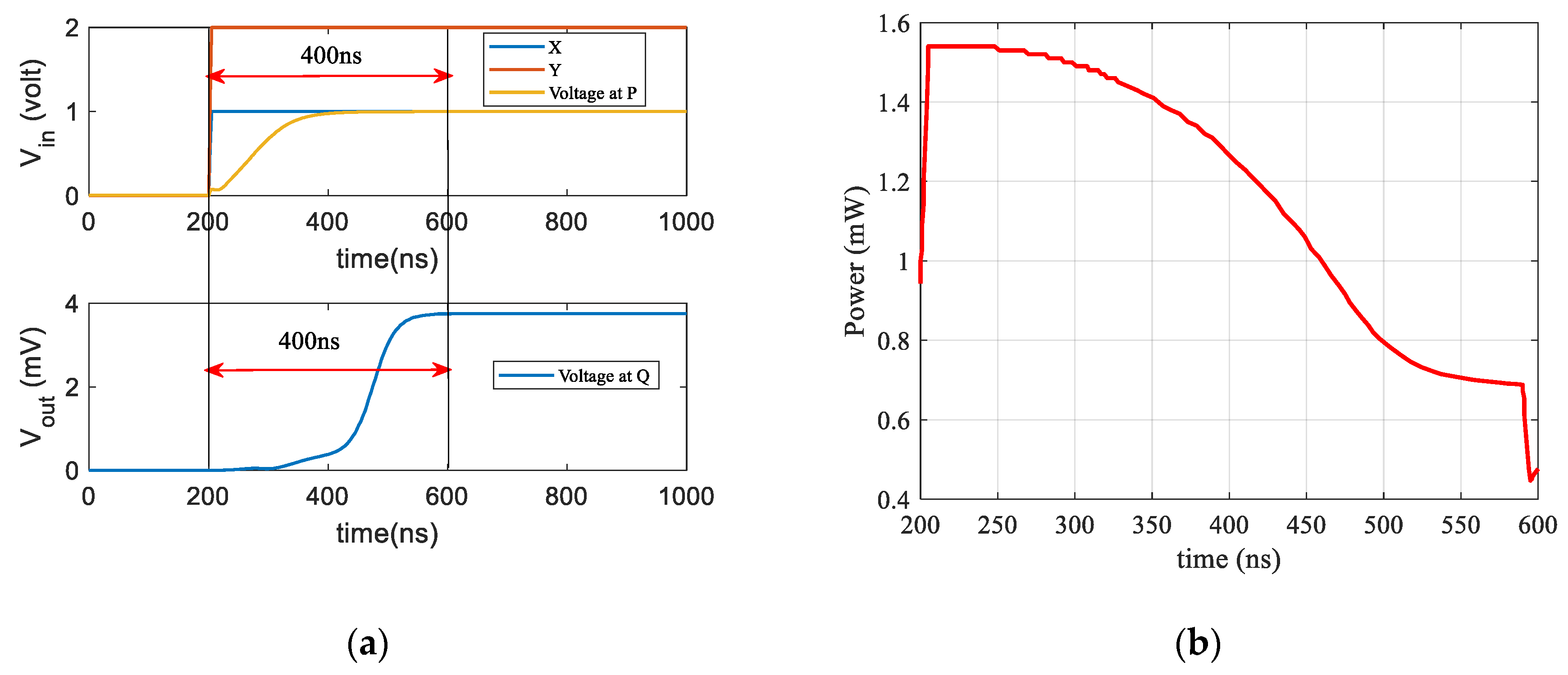

Figure 9a presents the SPICE simulation for the switching time of analog squaring circuits implemented for computing the reconstruction error of autoencoder. The graph shows two inputs (X, Y) applied at the differential circuit in

Figure 9a, and the differential voltage at node P. The timing for executing this circuit operation is 400ns, considered as the switching time. The switching time is required for the transistors in

Figure 9a to develop the maximum output voltage level at node

Q, while the input voltage is applied to the differential circuits. To compute the reconstruction error of the NSL-KDD network packets needs 41 of these circuits, thus total energy consumption can be computed accordingly as shown in Eq. (11).

The power consumption of error computing circuit is presented in

Figure 9b over the simulated switching time. To compute the total energy consumption, the area under the curve in

Figure 9b is computed by the integration over time t

2 to t

1 and the computed energy consumption is 20.2 nJ for computing the reconstruction error of an NSL-KDD packet.

8. Simulation of Online Threshold Computing Circuit

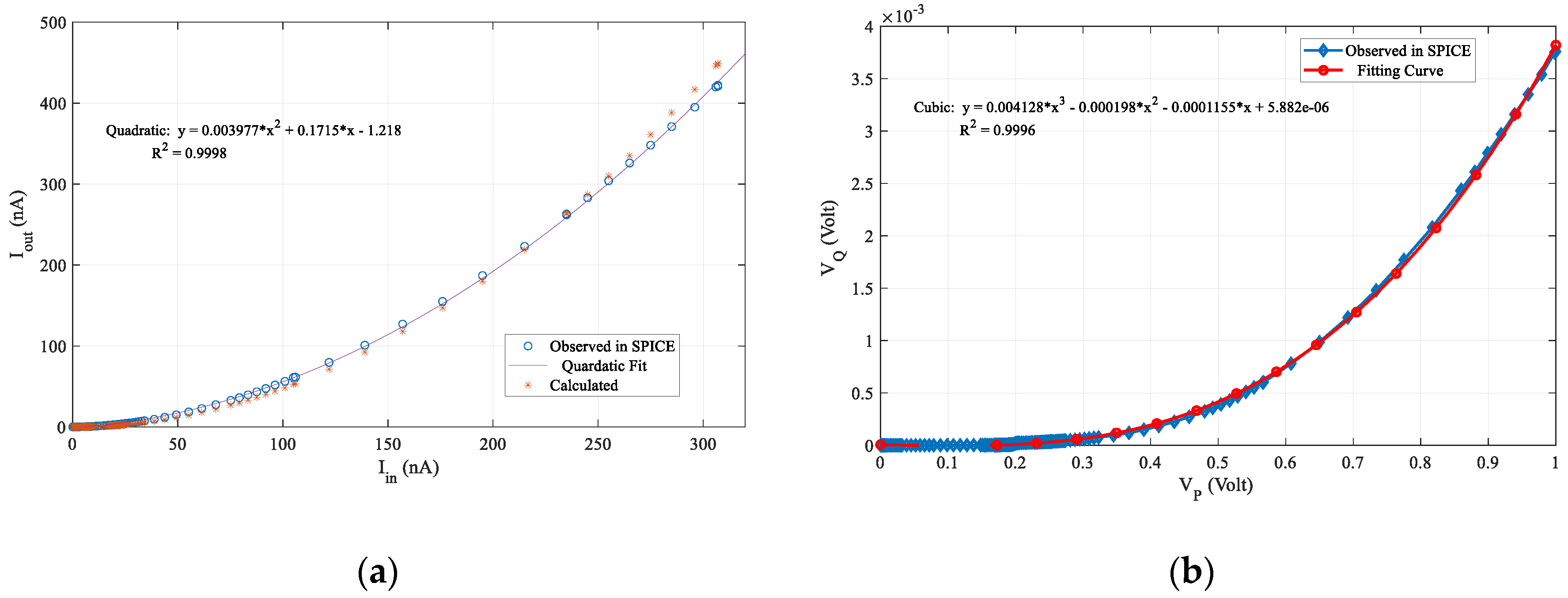

The squaring circuit is the main computing component online learning and anomaly detection. The actual circuit is implemented in the LTSpice and simulated with realistic circuit parameters by using actual device parameters. For this implementation, the ASU 90nm transistor model has been utilized as a well establish hardware preference. For differential calculations, ideal op-amp devices are considered for simplicity. The simulation results of

Figure 8 are presented in

Figure 10a & 10b.

The output current is the resulted mirror current flowing through M7 and that is a squared value normalized by the bias current (

Ibias). The simulated result is compared to the theoretical fitting relation (

) [

39], and follows the quadratic fit. The output voltage is measured at node Q (

Figure 10b) and fitting parameters of the output voltage is utilized in the MATLAB simulation to estimate the threshold for anomaly detection. All the parameters for circuit simulation are presented in

Table 1. The W and L are the width and length of the transistor and given in

µm. 9. Results and Discussion

The proposed online learning and anomaly detection system is highly dependent on the threshold computing system. This work implemented an analog threshold computing system with a low precision and power efficient ADC [

40] for data conversion.

9.1. Crossbar Traainnig Analysis

The crossbar training is performed in completely analog domain without using any data conversion units attached with crossbar circuits. The crossbars layers are connected toe-to-toe style. The crossbar training procedure is discussed in section III(B). This section discusses the training results and performance of AE on intrusion detection. The circuit parameters for training are presented in

Table 2. The realistic SPICE model was utilized for memristor device circuit simulation [

45].

9.2. Pretrained AE

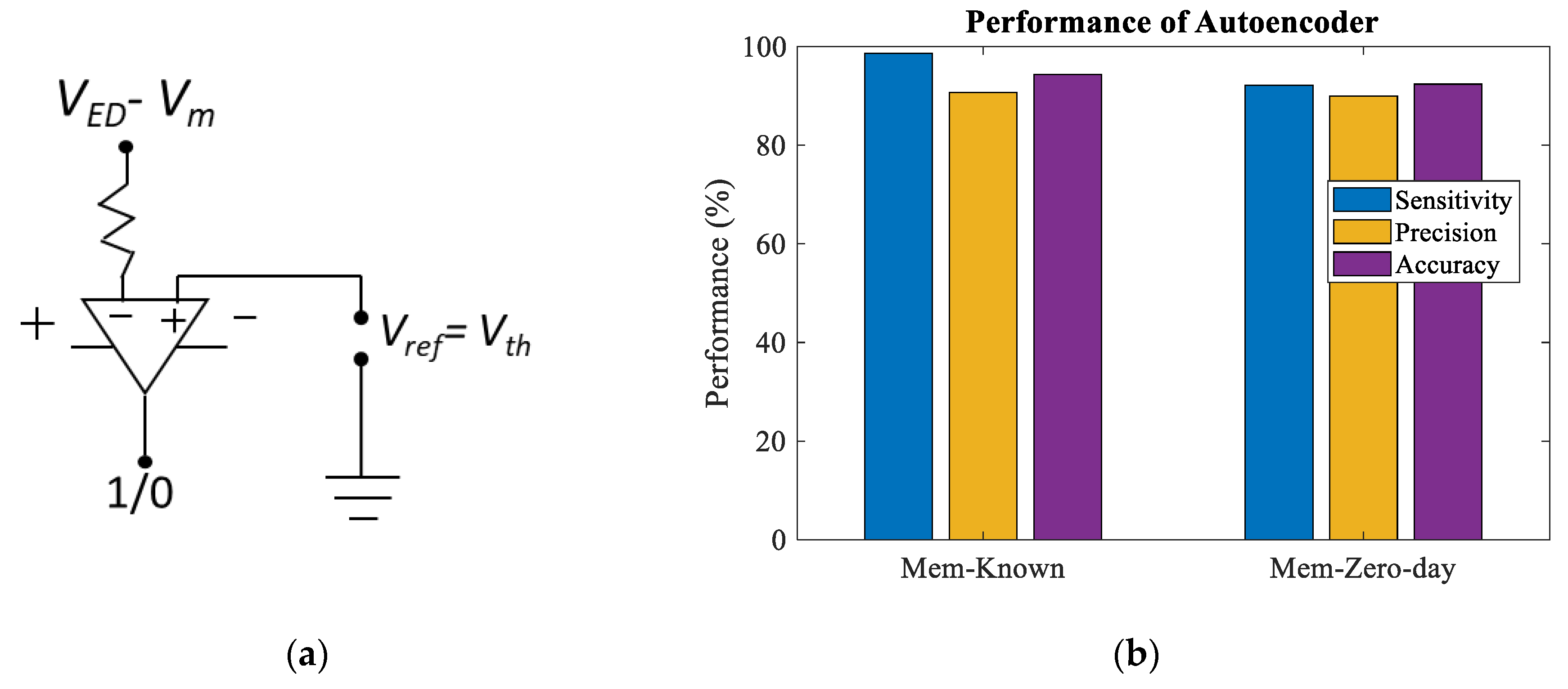

The pretraining of AE-1 in

Figure 6a is performed on-chip and the threshold is computed in floating. For AE based intrusion detection,

is used as the reference or threshold voltage in the comparator circuit to find known/anomalies among the incoming packets. If the amount of

VED - Vm>

Vth , then the system identifies the incoming packet as an unknown and labels it as

1. Otherwise, the packet is labeled as known or

0. The comparator op-amp is biased with

1 and

0 voltage supply.

Figure 11a is a comparator circuit to detect the incoming packets as normal or malicious.

Figure 11b presents the intrusion detection accuracy, sensitivity, and precision of memristor based AE-1, while the baseline software accuracy is 95.86% and 93.54% respectively for known and unknown network packets. AEs performs better than supervised model for zero-day attack identification with anomaly-based intrusion detection which can be refer to our previous works [

38].

9.3. Online Training Analysis

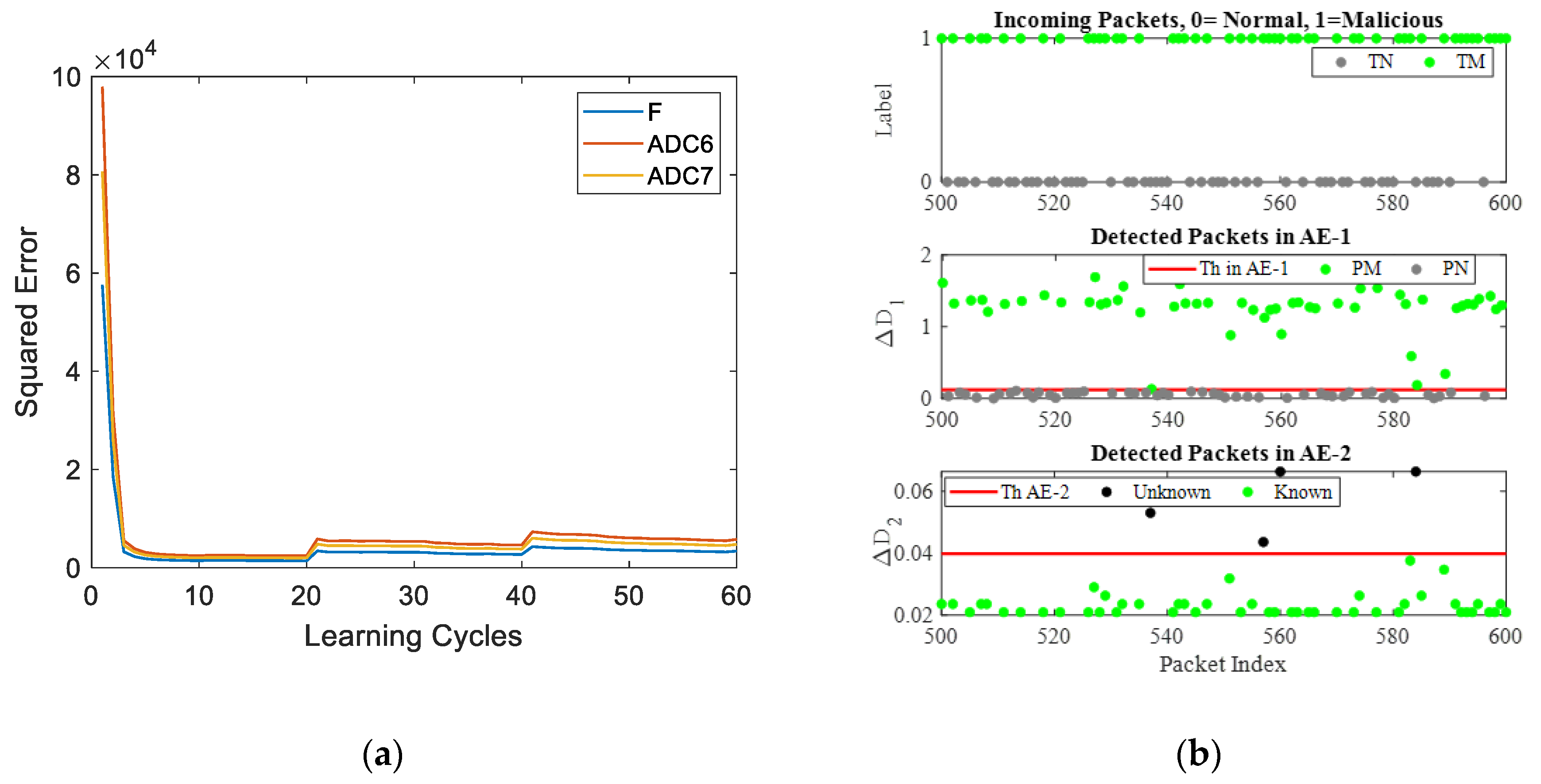

The training process of AE-2 (

Figure 6a) operates in real-time without relying on a floating-point processor. Various test datasets, including subsets of the NSL-KDD dataset, were used for online learning experiments. For instance, in Set-1, Normal and Probe packets were sent to the system, and AE-2 was instructed to learn only the Probe packets since AE-1 identified them as potential threats. Online training of AE-2 is illustrated in

Figure 12a.

When new malicious packets, such as those in Set-2, breached the rule-based IDS, AE-1 flagged and routed them to AE-2 for further learning. AE-2 identified these Zero-day attacks by flagging the unknown packets, leading to a temporary increase in anomalous packets and training error (

Figure 12a). However, with subsequent learning cycles, the system adapted, reducing anomalies and training errors as the packets became familiar. Pretraining of AE-1 (

Figure 6a) was performed on-chip, with the threshold V

th computed in floating-point for reference in AE-based intrusion detection.

Figure 12b illustrates network packet detection at different stages of the intrusion and anomaly detection system. While incoming packets are unlabeled, labels 0 (True Normal) and 1 (True Malicious) are used to assess detection accuracy. Pretrained AE-1, recognizing only normal packets, achieves over 93.5% accuracy in distinguishing normal (PN) and malicious (PM) packets, with the threshold marked by the red line. The lower part of

Figure 13b shows AE-2’s online anomaly detection, where its threshold is computed in real-time using analog-digital hybrid CMOS circuits (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

The online threshold is updated after each learning cycle, with the system storing the Euclidean distance as a digital equivalent in a LUT. While neural network computations occur entirely in the analog domain (

Figure 5), an ADC is used solely for converting the AE's generative error to compute thresholds. Training is online, learning sequentially from individual samples without batch processing.

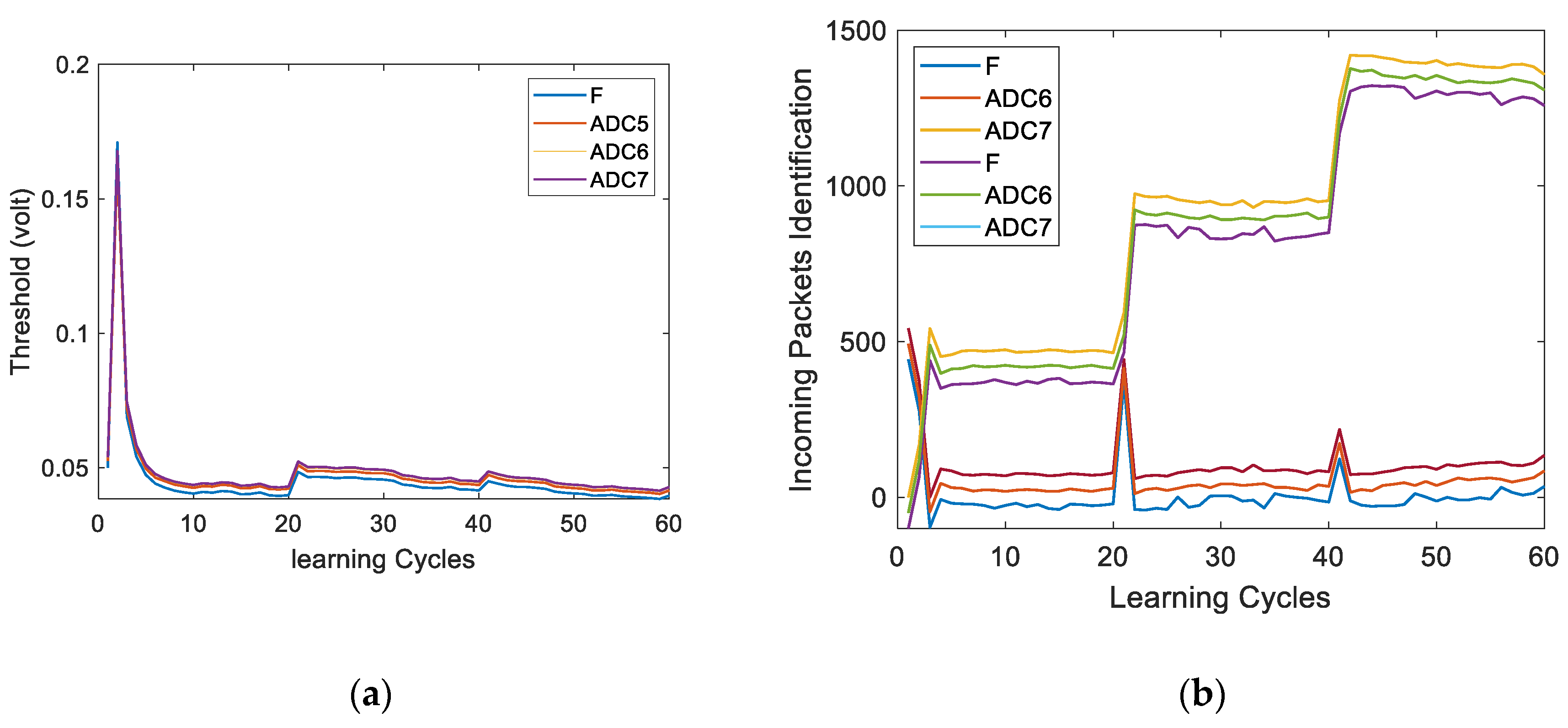

Figure 13a compares the floating-point threshold with those obtained using ADCs of various bit widths.

Figure 13b illustrates AE-2's online incremental learning and real-time anomaly detection. Initially, AE-2's parameters are random, and Testset-1 (containing normal and Probe packets) is processed. AE-1 identifies and forwards malicious packets to AE-2 for learning. At first, anomalies exceed 500 as AE-2 lacks knowledge of Probe packets. Over time, AE-2 learns, increasing known packets and reducing anomalies. At learning cycle 20, DoS packets cause a spike in anomalies, but subsequent cycles show adaptation, with anomalies decreasing as AE-2 becomes familiar. This iterative process enables the system to continuously learn and detect new malicious packets.

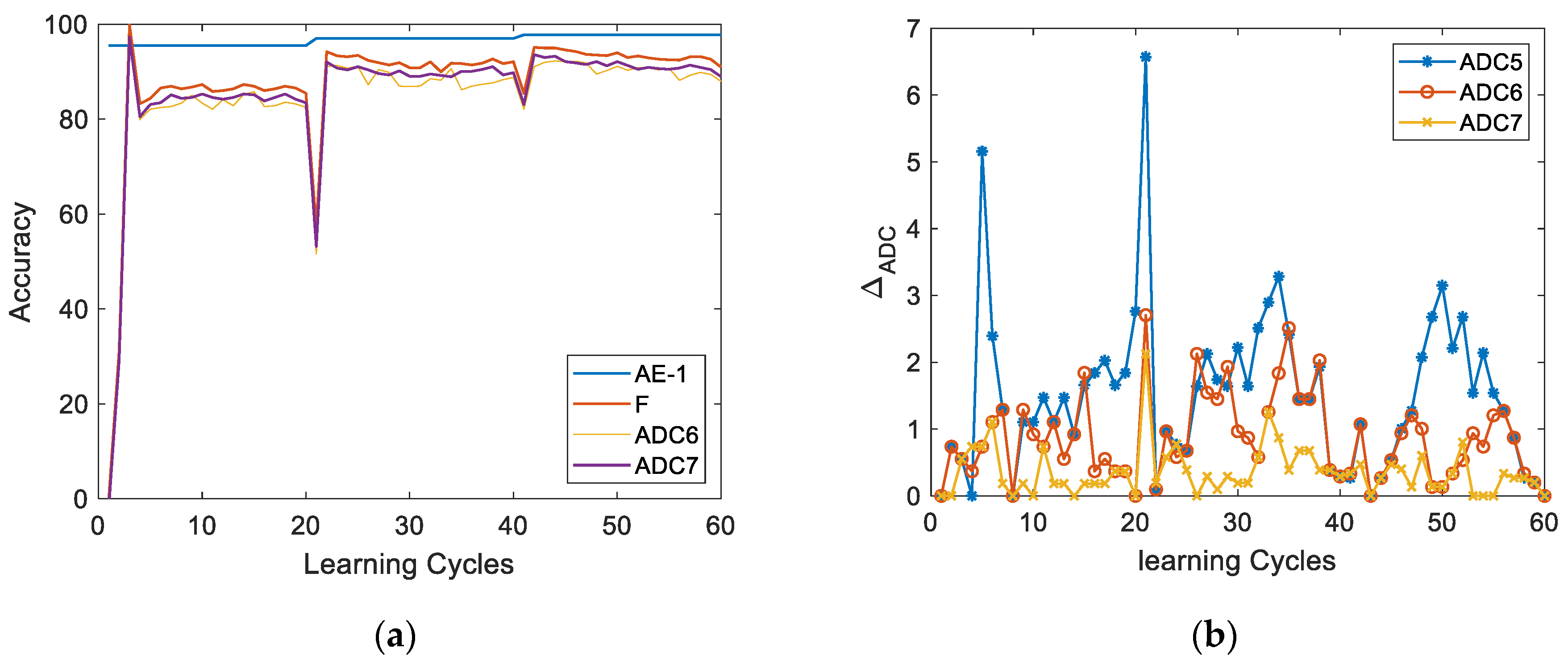

During online learning, AE-1 and AE-2 detect intrusions and anomalies, with detection accuracy shown in

Figure 14a. AE-1's accuracy remains steady until new intrusions occur, while AE-2 starts at zero and improves over training cycles. At cycle 19, AE-1’s accuracy rises slightly as it identifies unknown attacks, while AE-2's accuracy drops temporarily due to new anomalies. Over time, AE-2 adapts, and accuracy stabilizes until further anomalies appear.

The ADC resolution significantly impacts threshold computation in anomaly detection systems. While

Figure 14a shows minimal difference in anomaly detection performance between floating-point and low-precision threshold computation,

Figure 14b highlights a noticeable accuracy drop with a 5-bit ADC. However, using a 6-bit or 7-bit ADC provides a balanced trade-off, making them suitable options for developing online learning and anomaly detection systems in edge security applications.

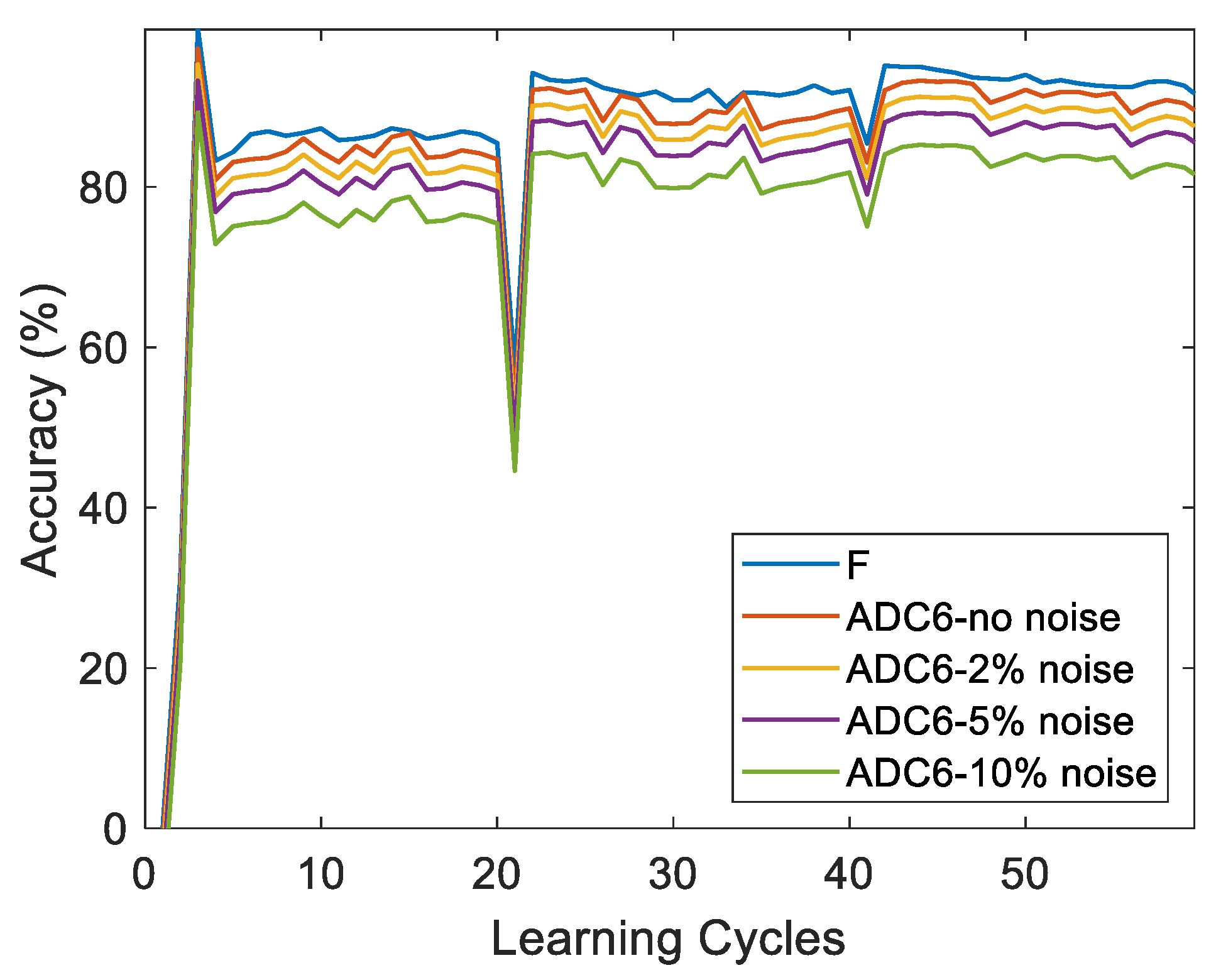

Memristor-based analog computing systems are often affected by device variability and circuit noise from analog sources.

Figure 15 demonstrates the system's performance under varying levels of noise, showing a clear decline in accuracy as noise increases. The random noise in the system is scaled relative to the minimum conductivity, highlighting the impact of analog noise on system reliability.

9.4. System Energy, Power and Performance Analysis

The anomaly detection system was benchmarked against a low-power commercial edge processor, the ASUS Tinkerboard, which features a Rockchip AI processor (RK3288), ARM Mali-T764 GPU, and 2 GB DDR3 RAM. Using 2000 NSL-KDD packets, the Tinkerboard required 1.8 seconds for detection, whereas the memristor-based system completed the task in just 0.0023 seconds—three orders of magnitude faster. The memristor system demonstrated 184,000× higher energy efficiency, achieving 16.1 GOPS and 783 GOPS/W, compared to the Tinkerboard’s 20 MOPS and 4.12 MOPS/W.

Table 3 compares numerical results for both systems. Other NSL-KDD dataset-based systems using floating-point processors and machine learning algorithms typically achieve performance ranging from kilo to mega operations per second [

42,

43,

44].

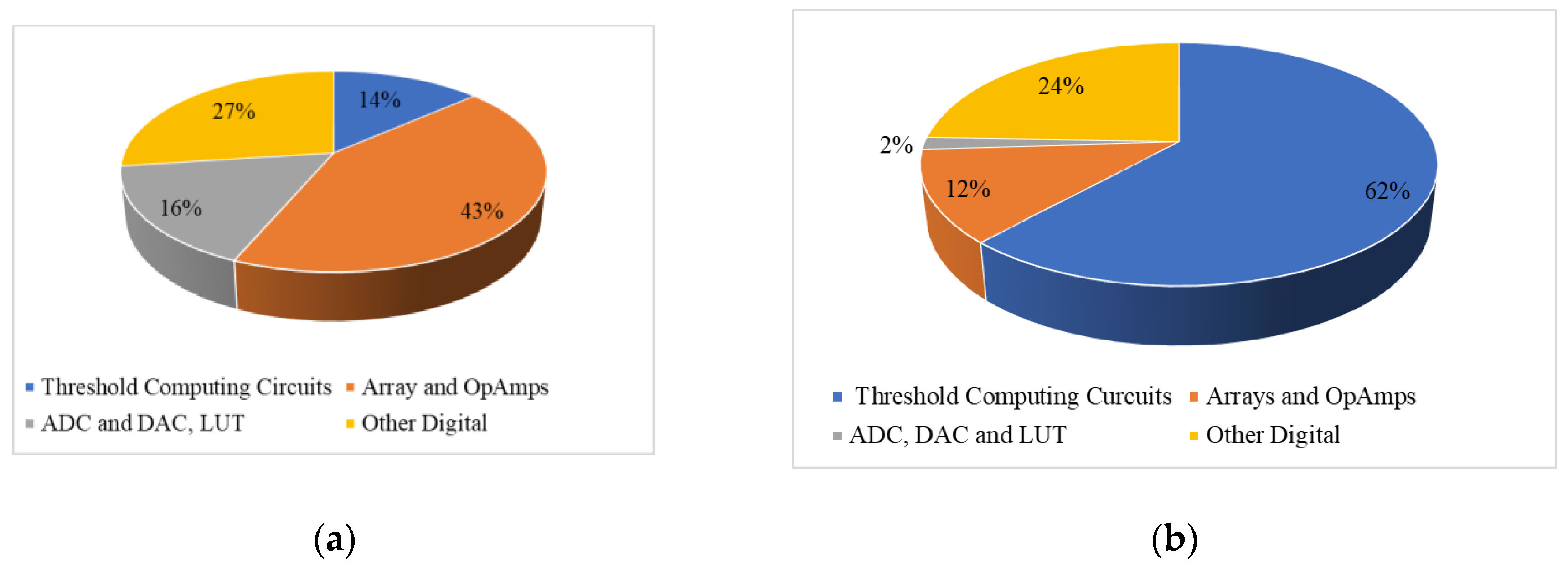

Figure 16a,b provide a breakdown of chip area and energy consumption for anomaly detection operations. During forward propagation, crossbar arrays and op-amps occupy the largest portion of the chip area (60%) if only one autoencoder is used. When two autoencoders are stacked, they occupy less area, allowing ADCs, DACs, and LUTs to take up 16%, and other digital circuits, including weight update and control units, to occupy 27%. Implementing ADC/DAC modules beneath the autoencoder circuits can significantly reduce chip footprint.

Energy analysis shows that threshold computing circuits account for 62% of energy usage during forward propagation. Differential and squaring circuits consume 20.2 nJ (0.493 nJ per circuit), while ADC/DAC modules, which are only used for reconstruction error and error gradient conversion, consume minimal energy. This energy-efficient design highlights the advantages of the memristor-based system over conventional processors.

10. Conclusions

In conclusion, a memristor-based on-chip system has been developed for online anomaly detection in edge devices, showcasing its potential for energy-efficient and real-time network security applications. The system integrates analog training circuits for unsupervised neural networks with a Euclidean distance computation unit for reconstruction error calculations, enabling effective detection of zero-day attacks. Compared to commercially available edge devices, this system offers significantly lower energy consumption while achieving impressive performance metrics of 16.1 GOPS and 783 GOPS/W, consuming just 20.5 mW during anomaly detection. These results highlight the system's viability for scalable and efficient edge security solutions.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation under the grant 1718633.

References

- IBM. Edge computing acts on data at the source. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/cloud/what-is-edge-computing (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Rai, A. Why real-time data monitoring is essential in preventing security threats. Available online: https://www.lepide.com/blog/why-real-time-data-monitoring-is-essential-in-preventing-security-threats/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Bhavsar, M.; Roy, K.; Kelly, J.; Olusola, O. Anomaly based intrusion detection system for IoT application. Discover Internet of Things 2023, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarpelão, B. B.; Miani, R. S.; Kawakani, C.T.; de Alvarenga, S .C. A survey of intrusion detection in Internet of Things. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2017, 84, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thudumu, S.; Branch, P.; Jin, J.; Singh, J. A comprehensive survey of anomaly detection techniques for high dimensional big data. Jornal of Big Data 2020, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, T.; Aditya Sai, G.; Mahalaxmi, R. A comprehensive survey of techniques, applications, and challenges in deep learning: A revolution in machine learning. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2022, 7, 286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Naumov, M.; Kim, J.; Mudigere, D.; Sridharan, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Yilmaz, S.; Kim, C.; Yuen, H.; Ozdal, M.; Nair, K. Deep learning training in facebook data centers: Design of scale-up and scale-out systems. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.09518. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Zhu, L.; Chen, W.M.; Wang, W.C.; Gan, C.; Han, S. On-device training under 256kb memory. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 22941–22954. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Peng, X.; Yu, S. MLP+ NeuroSimV3. 0: Improving on-chip learning performance with device to algorithm optimizations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neuromorphic Systems; 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian, A.; Le Gallo, M.; Khaddam-Aljameh, R., E. Eleftherious. Memory devices and applications for in-memory computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Tang, H.; Wu, J.; Song, W.; Zhang, M.; Yin, W.; Zhuo, Y.; Kiani, F.; Chen, B.; Jiang, X.; et al. Memristor devices denoised to achieve thousands of conductance levels. NATURE 2023, 615, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NSL-KDD dataset, https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/nsl.html.

- Takiddin, A.; Ismail, M.; Zafar, U.; Serpedin, E. Deep autoencoder-based anomaly detection of electricity theft cyberattacks in smart grids. IEEE Systems Journal 2022, 16, 4106–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenson, P.; Draxler, F.; Rousselot, A.; Hummerich, S.; Zimmerman, L.; Köthe, U. Maximum Likelihood Training of Autoencoders. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.01843. [Google Scholar]

- Krestinskaya, O.; Salama, K.N.; James, A. P. Learning in memristive neural network architectures using analog backpropagation circuits. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2018, 66, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Ambrogio, S.; Narayanan, P.; Shelby, B.; Mackin, C.; Burr, G. Analog memory-based techniques for accelerating the training of fully-connected deep neural networks. In SPIE Advanced Lithography; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, T.L.; Kanan, C. Lifelong machine learning with deep streaming linear discriminant analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops; 2020; pp. 220–221. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Feng, Y. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting beyond continual learning: Balanced training for neural machine translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.03910. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri, Z.; Liu, B. Lifelong Machine Learning; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rebuffi, S.-A.; Kolesnikov, A.; Sperl, G.; Lampert, C.H. iCaRL: Incremental Classifier and Representation Learning. 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 2017; pp. 5533–5542. [Google Scholar]

- Ashfahani, A.; Pratama, M.; Lughofer, E.; Ong, Y. S. DEVDAN: Deep evolving denoising autoencoder. Neurocomputing 2020, 390, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, S.S.; Ankit, A.; Roy, K. Incremental Learning in Deep Convolutional Neural Networks Using Partial Network Sharing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 4615–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malawade, A.V.; Costa, N.D.; Muthirayan, D.; Khargonekar, P.P.; Al Faruque, M.A. Neuroscience-Inspired Algorithms for the Predictive Maintenance of Manufacturing Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 17, 7980–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monakhov, V.; Thambawita, V.; Halvorsen, P.; Riegler, M.A. GridHTM: Grid-Based Hierarchical Temporal Memory for Anomaly Detection in Videos. Sensors 2023, 23, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faezi, S.; Yasaei, R.; Barua, A.; Al Faruque, M.A. Brain-inspired golden chip free hardware trojan detection. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, 16, 2697–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Y.D. A review on extreme learning machine. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 41611–41660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, W. Adaptive online sequential extreme learning machine for dynamic modeling. Soft Computing 2021, 25, 2177–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tu, S.; Zhao, W.; Shi, C. A novel energy-based online sequential extreme learning machine to detect anomalies over real-time data streams. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadr, M.A.A.; Tiun, S.; Ayob, M.; Al-Dhief, F.T.; Abdali, T.-A.N.; Abbas, A.F. Extreme Learning Machine for Automatic Language Identification Utilizing Emotion Speech Data. 2021 International Conference on Electrical, Communication, and Computer Engineering (ICECCE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S.; Yakopcic, C.; Subramanyam, G.; Taha, T.M. Memristor based neuromorphic adaptive resonance theory for one-shot online learning and network intrusion detection. International Conference on Neuromorphic Systems, 2020 (ICONS 2020). Article No. 25. pp.1-8. July 2020.

- Jones, C.B.; Carter, C.; Thomas, Z. Intrusion Detection & Response using an Unsupervised Artificial Neural Network on a Single Board Computer for Building Control Resilience. 2018 Resilience Week (RWS), Denver, CO, USA, 2018; pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Sachdeva, N. Cyberbullying checker: Online bully content detection using Hybrid Supervised Learning. In International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Smart Communication: Proceedings of ICSC 2019; Springer Singapore, 2020; pp. 371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Lai, C.S.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, D.; Gao, M.; Duan, S. Neuromorphic extreme learning machines with bimodal memristive synapses. Neurocomputing 2021, 453, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Cheng, H.; Wei, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, H. Memristive neural networks: A neuromorphic paradigm for extreme learning machine. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2019, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureneva, O.I.; Prasad, M.S.; Verma, S. FPGA-based Hardware Implementation of the ART-1 classifier. In 2023 XXVI International Conference on Soft Computing and Measurements (SCM); Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation, 2023; pp. 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Govorkova, E.; Puljak, E.; Aarrestad, T.; James, T.; Loncar, V.; Pierini, M.; Pol, A.A.; Ghielmetti, N.; Graczyk, M.; Summers, S.; Ngadiuba, J. Autoencoders on field-programmable gate arrays for real-time, unsupervised new physics detection at 40 MHz at the Large Hadron Collider. Nature Machine Intelligence 2022, 4, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Fernando, B.R.; Jaoudi, Y.; Yakopcic, C.; Hasan, R.; Taha, T.M.; Subramanyam, G. Memristor based autoencoder for unsupervised real-time network intrusion and anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neuromorphic Systems, July 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S.; Yakopcic, C.; Taha, T.M. University of Dayton. Unsupervised learning of memristor crossbar neuromorphic processing systyems. U.S. Patent Application 17/384,306, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nag, A.; Paily, R.P. Low power squaring and square root circuits using subthreshold MOS transistors. 2009 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electronic and Photonic Devices & Systems, Varanasi, India, 2009; pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Li, W.; Huang, S.; Cosemans, S.; Catthoor, F.; Yu, S. Analog-to-Digital Converter Design Exploration for Compute-in-Memory Accelerators. IEEE Design & Test 2022, 39, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- ASUS. Tinkerboard, https://tinker-board.asus.com/product/tinker-board.html.

- Suleiman, M.F.; Issac, B. Performance Comparison of Intrusion Detection Machine Learning Classifiers on Benchmark and New Datasets. 2018 28th International Conference on Computer Theory and Applications (ICCTA), Alexandria, Egypt, 2018; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, D.; Mohanraj, V.; Suresh, Y.; Senthilkumar, J. Retracted: An efficient stacking model with SRPF classifier technique for intrusion detection system. International Journal of Communication Systems 2021, 34, e4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamolia, V.; Melnyk, V.; Zhezhnych, P.; Shilinh, A. Intrusion detection in computer networks using latent space representation and machine learning. International Journal of Computing 2020, 19, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakopcic, C.; Taha, T.M.; Subramanyam, G.; Pino, R.E. Memristor SPICE model and crossbar simulation based on devices with nanosecond switching time. The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Dallas, TX, USA, 2013; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, R.; Taha, T.M.; Yakopcic, C. On-chip training of memristor based deep neural networks. 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 2017; pp. 3527–3534. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

NSL-KDD dataset: (a) Normal and malicious packets in raw and normalized format; (b) distribution of normal and malicious packets in training and test dtaset.

Figure 1.

NSL-KDD dataset: (a) Normal and malicious packets in raw and normalized format; (b) distribution of normal and malicious packets in training and test dtaset.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of a autoencoder learning network.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of a autoencoder learning network.

Figure 3.

Neural Network model of the autoencoder with the layer size.

Figure 3.

Neural Network model of the autoencoder with the layer size.

Figure 4.

Single Neuron, (a) Input and hidden layers, (b) Output layer.

Figure 4.

Single Neuron, (a) Input and hidden layers, (b) Output layer.

Figure 5.

A Crossbar circuit representing the ANN outputs layer with inputs and corresponding outputs, error generation circuit, and Euclidean distance computation circuitry.

Figure 5.

A Crossbar circuit representing the ANN outputs layer with inputs and corresponding outputs, error generation circuit, and Euclidean distance computation circuitry.

Figure 6.

(a) The online learning and anomaly detection system, (b) Flowchart of online learning and anomaly detection systems.

Figure 6.

(a) The online learning and anomaly detection system, (b) Flowchart of online learning and anomaly detection systems.

Figure 7.

(a) Block diagram of circuitry that is implemented for online Euclidean distance computation for anomaly detection, (b) Block diagram of Euclidean distance calculation circuit.

Figure 7.

(a) Block diagram of circuitry that is implemented for online Euclidean distance computation for anomaly detection, (b) Block diagram of Euclidean distance calculation circuit.

Figure 8.

Threshold computing circuit, section A gives a non-negative output voltage from the difference of input and output vector of autoencoder, section B converts voltage into current Ix-y, section C square the incoming current and the output voltage sensed in the load resistance RH. The SPICE simulation utilized device parameters for 90nm technology, other parameters are R=1kΩ, R1=1.5megΩ, RH=10kΩ.

Figure 8.

Threshold computing circuit, section A gives a non-negative output voltage from the difference of input and output vector of autoencoder, section B converts voltage into current Ix-y, section C square the incoming current and the output voltage sensed in the load resistance RH. The SPICE simulation utilized device parameters for 90nm technology, other parameters are R=1kΩ, R1=1.5megΩ, RH=10kΩ.

Figure 9.

(a) Switching timing and input-output voltage measurement in proposed circuit (

Figure 8), (b) Power consumption over time of ED computing circuit.

Figure 9.

(a) Switching timing and input-output voltage measurement in proposed circuit (

Figure 8), (b) Power consumption over time of ED computing circuit.

Figure 10.

(a) Measured current and estimated current flowing in the output squaring circuit, (b) Measured voltage and estimated voltage at the output node.

Figure 10.

(a) Measured current and estimated current flowing in the output squaring circuit, (b) Measured voltage and estimated voltage at the output node.

Figure 11.

(a) The comparator circuit for identifying the known anomalies of incoming packets; (b) Performance score of autoencoder AE-1 for known and zero-day attacks offline.

Figure 11.

(a) The comparator circuit for identifying the known anomalies of incoming packets; (b) Performance score of autoencoder AE-1 for known and zero-day attacks offline.

Figure 12.

(a) Online training error. Error increases once anomalies are encountered in the system and decreases with successive learning cycles. (b) An excerpt from the incoming normal and malicious packets and the predicted normal and malicious packets.

Figure 12.

(a) Online training error. Error increases once anomalies are encountered in the system and decreases with successive learning cycles. (b) An excerpt from the incoming normal and malicious packets and the predicted normal and malicious packets.

Figure 13.

(a) Threshold optimization during the online training process, (b) Anomaly detection and incremental learning on malicious packets in real-time.

Figure 13.

(a) Threshold optimization during the online training process, (b) Anomaly detection and incremental learning on malicious packets in real-time.

Figure 14.

(a) Anomaly detection accuracy during online training. Accuracy is computed after each learning cycle, (b) Accuracy variations utilizing ED circuits compared to the floating-point threshold computing.

Figure 14.

(a) Anomaly detection accuracy during online training. Accuracy is computed after each learning cycle, (b) Accuracy variations utilizing ED circuits compared to the floating-point threshold computing.

Figure 15.

Experiment of online learning with noise. The noise level is scale as relative to the minimum conductivity of the memristor devices.

Figure 15.

Experiment of online learning with noise. The noise level is scale as relative to the minimum conductivity of the memristor devices.

Figure 16.

(a) Breakdown of (a) area occupancy, and (b) energy of various circuit elements in memristor based anomaly detection and online learning systems.

Figure 16.

(a) Breakdown of (a) area occupancy, and (b) energy of various circuit elements in memristor based anomaly detection and online learning systems.

Table 1.

Parameters for threshold computing circuit simulation.

Table 1.

Parameters for threshold computing circuit simulation.

| Parameter |

Magnitude |

Unit |

| R |

1000 |

Ohm |

| R1 |

1.50×106

|

Ohm |

| M1 |

1.99/0.65 |

W/L |

| M2 |

1.99/0.65 |

W/L |

| M3 |

0.2/0.16 |

W/L |

| M4 |

0.24/0.18 |

W/L |

| M5 |

1.28/0.65 |

W/L |

| M6 |

1.85/0.65 |

W/L |

| M7 |

1.85/0.65 |

W/L |

| Vbias |

0.4 |

volt |

| Ibias |

210 |

nA |

| RH |

10000 |

Ohm |

Table 2.

Parameters for memristor circuit simulation.

Table 2.

Parameters for memristor circuit simulation.

| Parameter |

Magnitude |

Unit |

| Cycle time |

2×10-9

|

sec |

| Max training pulse duration |

5×10-9

|

sec |

| Roff

|

10 |

MΩ |

| Ron

|

50 |

KΩ |

| Ravg

|

5.025 |

MΩ |

| Wire Resistance |

5 |

Ω |

| Vmem

|

1.3 |

V |

| Pmem

|

0.336 |

µW |

| Op-Amp power |

3µ |

W |

| Max read voltage |

1.3 |

V |

| Feature size, F |

45 |

nm |

| Transistor size |

50 |

F2

|

| Memristor Area |

10000 |

nm2

|

| Cycle time |

2 |

ns |

| Crossbar processing time |

50 |

ns |

Table 3.

Hardware Performance Analysis.

Table 3.

Hardware Performance Analysis.

| Parameters |

TinkerBoard |

Memristor System |

| Test Sample |

2000 |

2000 |

| Time (sec) |

1.807563 |

2.3×10-3

|

| Time/Sample |

9.04×10-4

|

1.17×10-6

|

| Speedup |

1 |

774 |

| Energy (joule) |

4.52×10-3

|

2.08×10-7

|

| Power (W) |

5 |

0.0205 |

| Performance (OPS) |

20×106

|

16.1×109

|

| Energy Efficiency (OPS/W) |

4.12×106

|

7.83×1011

|

| Area (mm2) |

--- |

4.43×10-3

|

| Test Sample |

2000 |

2000 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).