1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a severe psychiatric condition characterized by one or more episodes of persistent low mood, lasting at least two weeks. These episodes are marked by significant changes in mood, a loss of interest or pleasure in activites, difficulties with concetration and decision-making, and alterations in sleep, appetite and energy levels [

41]. Depression, while sharing some characteristics with normal sadness and grief, is distinct due to its prolonged duration, often persisting long after the initial triggers have subsided, and its intensity, which is disproportionate to the underlying causes [

3]. Moreover, depression is linked to significant impairments in cognitive function, notably in learning and memory. Scientific research has demonstrated the detrimental effects of chronic stress on the central nervous system, particularly evident in structural changes observed within the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory formation [

46].

Depression is a challenging condition caused by the intricate interaction of biological, psychological, and environmental variables. Genetic susceptibility, neurotransmitter imbalances, hormonal changes, and anatomical abnormalities in brain areas such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex which all play a role in its biology. Psychologically, negative thought patterns, low self-esteem, and dysfunctional coping methods have a crucial role. Chronic stress, traumatic events, and a lack of social support are all significant environmental stressors. The interaction between genetic susceptibility and environmental stresses demonstrates how those with a genetic predisposition to depression may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of life's challenges. This complex interaction of elements eventually affects the disorder's development, severity, and progression [

3].

Numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated the potential of phytochemicals from herbal medicines, both pharmaceutical and nutraceutical, to alleviate depressive symptoms. However, the precise mechanisms through which these natural compounds influence the brain remain unclear [

23]. Unlike direct brain interventions or herbal medications, the gut microbiota can be more readily manipulated through dietary modifications, such as the use of prebiotics, probiotics, and antibiotics, as well as lifestyle adjustments [

38]. The composition of the gut microbiota is a dynamic entity influenced by various factors, including diet, age, sex, environmental exposures, and genetic predispositions [

49].

Research into gut-brain communication has revealed a sophisticated system that not only regulates digestive processes but also exerts significant influence on emotions, motivation, and higher-order cognitive functions. This intricate communication network is termed as "gut-brain axis" (GBA) [

9]. Accumulating evidence demonstrates the profound impact of gut bacteria on brain structure and function. For instance, animals raised in sterile environments, devoid of a gut microbiota, exhibit notable brain abnormalities [

38]. The GBA plays a pivotal role in maintaining overall bodily homeostasis and promoting optimal mental well-being [

36].

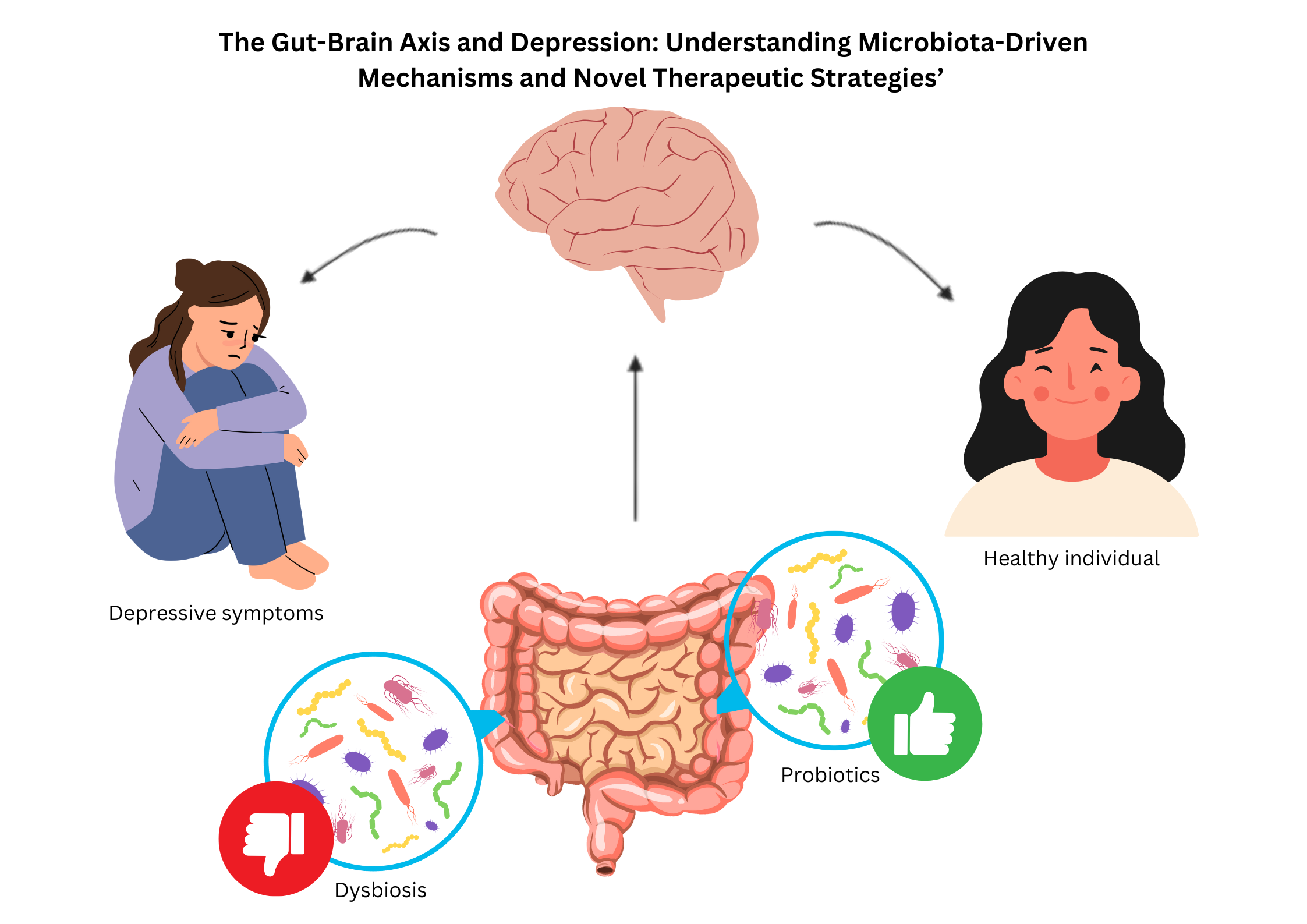

While research on MDD has traditionally focused on the central nervous system, emerging evidence highlights the crucial role of peripheral systems, particularly the gut microbiota, in influencing mental health. The GBA, a complex bidirectional communication network connecting the gut and brain, has emerged as a critical player in the development and progression of depression. Mounting evidence suggests that the gut microbiota can significantly impact various aspects of MDD through the "microbiota-gut-brain axis," demonstrating its profound influence on brain function and behavior [

58]. The gut-brain axis (GBA) not only maintains gastrointestinal balance but also influences emotions, cognitive processes, and motivation through complex interactions with the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems. Understanding these intricate relationships provides new avenues for exploring the gut microbiome's role in major depressive disorder (MDD) and developing innovative therapeutic approaches.

2. Gut Microbiota System

The gut microbiota significantly influences host physiology and pathology through its interactions with various organs, including hormone production and the regulation of bodily functions. The gut-brain axis, a complex bidirectional communication network connecting the gut and the central nervous system (CNS), facilitates this interaction through chemical, neurological, immune, and endocrine mechanisms [

49]. This interaction encompasses chemical, neural, immune, and endocrine pathways. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the gut microbiota, can lead to gastrointestinal disorders and disrupt host physiology by producing abnormal microbial metabolites that trigger a cascade of physiological responses [

49].

The gut microbiome is a diverse ecosystem within the human digestive system, comprising bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotic microorganisms. This intricate microbial community possesses a genetic repertoire significantly larger than the human genome, harboring an estimated 1,000 bacterial species and 7,000 strains. The dominant bacterial phyla within this ecosystem include

Firmicutes (such as

Lactobacillus,

Eubacterium, and

Clostridium) and

Bacteroidetes (such as

Bacteroides and

Prevotella), with five major phyla:

Bacteroidetes,

Firmicutes,

Actinobacteria,

Proteobacteria, and

Verrucomicrobia constituting the majority of the gut microbial population [

49].

The gut-brain axis, a complex communication network involving the gut microbiota, immune system, and CNS, plays a crucial role in mental health. Disturbances within this axis have been implicated in the development of depression [

16]. The gut microbiota influences brain function by stimulating the production of immune factors like cytokines and inflammatory mediators, impacting both the CNS and the enteric nervous system (ENS), often referred to as the "second brain" [

49]. The ENS communicates bidirectionally with the CNS, influencing mood and stress responses. Dysbiosis, an imbalance in the gut microbiota, can trigger inflammatory pathways and disrupt neurotransmitter synthesis, potentially contributing to the emergence of depressive symptoms [

21].

The research conducted by Kumar [

29] elucidates the alterations in bacterial genera associated with depression. Their findings reveal a reduction in several genera, including

Clostridia, Bacteroides, Candidatus saccharimonas, Alistipes, Roseburia, Coprococcus, Dialister, Fusicatenibacter, Butyricicoccus, Faecalibacterium, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, Dorea, Anaerostipes, and

Sphingobacterium. Simultaneously, an augmentation is observed in other genera, namely

Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Bifidobacterium, Oscilibacter, Streptococcus, Phascolarctobacterium, Parabacteroides, Holdemania, Bilophila, Oxalobacter, Pseudomonas, Parvimonas, Bulleidia, Peptostreptococcus, and

Gemella. Kumar [

29] further elucidate that

Firmicutes and

Actinobacteria exhibit more consistent patterns, with the former, along with

Bifidobacterium, typically experiencing a decline, whilst the latter tends to proliferate. Notably,

Bacteroides and

Clostridium emerge as the most ubiquitous and variable genera, with their abundance potentially fluctuating in individuals afflicted with depression, subject to contextual factors, study design, or specific species within these genera.

Table 1.

Summarize of the bacteria genera classification towards human and animal studies.

Table 1.

Summarize of the bacteria genera classification towards human and animal studies.

| Bacteria Genera |

Human Studies |

Animal Studies |

Remarks |

| Firmicutes |

↓ Decreased in most studies |

↓ Decreased in rodent models of depression |

Key SCFA producers (e.g., Faecalibacterium, Coprococcus) |

| ↓ Associated with gut dysbiosis and reduced SCFAs |

↓ Correlated with depressive-like behaviours in rodents |

| Bifidobacterium |

↓ Decreased in depression |

↓ Decreased in stress-induced models |

Serotonin modulation, probiotic supplementation improves mood |

| Actinobacteria |

↓ Decreased in some studies which usually decreased in Bifidobacterium too |

↑ Increased in certain conditions like high-fat diets and stress |

Contains beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium

|

| Bacteroides |

↓ Decreased in some cases, however it also ↑ increased in others |

↓ Decreased in high-stress or high-fat diet models |

Variable depending on species and inflammation |

| Clostridium |

↓ Decreased in beneficial species like Clostridium butyricum in SCFAs production leading to increased inflammation and gut-brain axis disruption |

↑ Increased in pathogenic species like Clostridium perfringens in dysbiotic conditions of stress-induced models. |

Loss of SCFA producers affects gut health which may worsen inflammation |

| Faecalibacterium |

↓ Decreased in depression |

↓ Reduced in stress models |

Major SCFA producer (anti-inflammatory) |

| Coprococcus |

↓ Depleted in participants with depression |

↓ Reduced in stress-induced animal models |

Butyrate producer with anti-inflammatory properties |

| Roseburia |

↓ Decreased in depression |

↓ Decreased in animal models with induced stress |

SCFA producer important for gut integrity |

| Dialister |

↓ Decreased in patients with major depressive disorder |

↓ Reduced in animal models with gut dysbiosis |

Associated with mood regulation |

| Lactobacillus |

↓ Decreased in depression |

↓ Reduced in rodent models of stress |

Produces neurotransmitters like Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) |

| Ruminococcus |

↓ Decreased in depressive patients |

↓ Reduced in animal models |

SCFA production and gut health |

| Alistipes |

↓ Decreased in individuals with depression |

↓ Reduced in stress-induced animal models. |

Associated with mental signs of depression |

| Prevotella |

↓ Decreased in most studies |

↓ Reduced in rodent models |

Associated with carbohydrate metabolism |

Furthermore, research has demonstrated that exposure to specific microbial strains can confer protection against stress-induced behavioral and systemic immunological alterations, providing strong support for the potential of microbe-based therapies in the treatment of stress-related disorders [

38].

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are metabolites produced by a healthy gut microbiota through the fermentation of dietary fibers and resistant starch [

47]. These SCFAs play a crucial role in immune modulation [

16]. Butyrate, in particular, is believed to influence the gut-brain axis, potentially by enhancing the production of colonic serotonin, a key neurotransmitter for mood and behavior regulation. Moreover, animal studies have demonstrated that butyrate may exhibit antidepressant-like effects by stimulating the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein essential for neuronal development and survival [

32].

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) play a crucial role in reducing inflammation, maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, and regulating central nervous system function. However, microbial imbalance, or dysbiosis, leads to decreased SCFA production, diminishing their anti-inflammatory effects and promoting inflammation. Research suggests that restoring SCFA levels through dietary interventions or probiotic supplementation can improve immunological function and alleviate depressive symptoms. These findings underscore the potential therapeutic value of modulating the gut microbiota in the treatment of depression [

16].

The gut-brain axis plays a crucial role in mental health, as disruptions in this communication pathway have been implicated in disorders such as depression and anxiety [

2]. Given the critical need for novel treatment and preventative strategies for mental health [

50], understanding the gut microbiota's influence on emotional and cognitive function, neurotransmitter synthesis, neuroinflammation, and gut barrier integrity is of paramount importance [

48]. This intricate relationship involves bidirectional communication between the gut and the brain, with key brain regions like the insula and anterior cingulate cortex playing a significant role in regulating gut function and psychological responses [

26]. Despite variations in gut microbiota composition observed across studies, all findings consistently demonstrate significant alterations in the gut microbiota of individuals with depression. This suggests that the gut microbiota may represent a novel target for the prevention and treatment of this disorder [

53]. A comprehensive understanding of how the gut microbiota influences various psychiatric conditions is crucial for developing innovative and effective therapeutic strategies, emphasizing the importance of an integrated approach to mental healthcare [

48].

The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the synthesis and regulation of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate, which are essential for neurological and immunological functions in the brain. This intricate microbial community exhibits significant complexity, with certain microbial species potentially promoting mental well-being while others may contribute to the development and progression of mental disorders [

53].

Studies have shown significant alterations in the gut microbiota composition of individuals with depression compared to healthy controls. Patients with depression exhibited reduced levels of

Dialister and

Coprococcus spp. and elevated levels of

Prevotella,

Klebsiella,

Streptococcus, and

Clostridium XI, along with lower levels of

Bacteroidetes. Animal studies corroborated these findings, as faecal microbiota transplants from depressed individuals induced depression-like behaviours in mice, whereas transplants from healthy rats prevented depression in susceptible rats. These results suggest that gut microbiota dysbiosis plays a crucial role in depression by affecting protein expression along the gut–brain axis. Although microbial composition varies across studies, specific families (e.g.

Paraprevotella-positive and

Streptococcaceae and

Gemella-negative) and genera (e.g.

Prevotella,

Klebsiella, and

Clostridium) have been associated with depression [

53].

3. Current Evidence Linking the Gut Microbiota to Depression

3.1. Microbiota Composition and Diversity

The human gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex ecosystem of billions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota, primarily comprising bacteria. This microbial community plays a crucial role in various physiological processes, including maintaining intestinal barrier function, regulating energy metabolism, defending against pathogens, and modulating the immune system [

40]. While overall diversity and phylum-level analyses may not reveal significant differences, studies comparing the gut microbiota of individuals with depression to healthy controls have identified specific bacterial taxa associated with this mental health condition [

22].

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is often associated with decreased microbial diversity, characterized by lower levels of beneficial bacteria such as

Bacteroides and

Faecalibacterium in individuals with depression. Studies have shown fluctuations in the relative abundance of

Bacteroides in individuals with depression, with medication-free individuals exhibiting higher levels, suggesting a potential link between this bacterium and depressive symptoms.

Faecalibacterium, a key producer of the anti-inflammatory SCFA butyrate, is significantly reduced in individuals with depression. This decline in beneficial microorganisms may contribute to the inflammatory processes observed in depression [

22]. Consistent findings across studies have revealed lower abundances of several beneficial bacterial genera, including

Butyricicoccus,

Coprococcus,

Faecalibacterium,

Fusicatenibacter,

Eubacterium ventriosum group,

Romboutsia, and

Subdoligranulum, in individuals with depression compared to healthy controls. Conversely, higher abundances of

Eggerthella,

Enterococcus,

Escherichia,

Flavonifractor,

Holdemania,

Lachnoclostridium,

Paraprevotella, Rothia, and

Streptococcus were observed in individuals with depression. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain these associations, primarily focusing on altered pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling along the gut-brain axis [

22].

Animal studies have demonstrated that the gut microbiota can significantly influence stress responses, anxiety-like behaviors, depression, and social interactions. Potential mechanisms underlying this gut-brain connection include neurological, immunological, and endocrine pathways. Microbes can synthesize various neuroactive compounds and modulate host neurotransmitter levels. Disruptions in the gut microbiota can lead to neurotransmitter imbalances, inflammation, and hyperactivity of the HPA axis, the primary stress response system [

25]. In study of 90 young adults in America, the gut microbiota of 43 patients with MDD were compared to 47 healthy controls. The findings revealed significant differences in the gut microbiota composition between the two groups at various taxonomic levels. At the phylum level, MDD patients exhibited lower levels of

Firmicutes and higher levels of

Bacteroidetes, with similar trends observed at the class (

Clostridia and

Bacteroidia) and order (

Clostridiales and

Bacteroidales) levels [

31].

3.2. Probiotics and Prebiotics

In adults, the gut microbiota, primarily residing in the colon, can weigh up to approximately 1 kilogram. The dominant phyla within this complex ecosystem include

Bacteroidetes and

Firmicutes, while

Actinobacteria,

Proteobacteria, and

Verrucomicrobia are present in smaller proportions. Additionally, the gut microbiome encompasses methanogenic archaea, eukaryotes (predominantly yeast), and numerous bacteriophages [

7]. Probiotic consumption can enhance the balance of the gut microbiota [

1]. These beneficial microorganisms can positively influence the immune system, a crucial factor in mood regulation. Depression and anxiety are often associated with dysregulated immune responses, characterized by increased inflammation. Probiotics may help mitigate this imbalance by stimulating anti-inflammatory responses and reducing the production of pro-inflammatory molecules [

42].

Prebiotics are non-digestible compounds, such as fructooligosaccharides, galacto-oligosaccharides, and xylooligosaccharides, that serve as food for gut microbes, thereby altering the gut microbiome composition in a manner that benefits the host [

1,

6]. They selectively stimulate the growth and/or activity of specific beneficial bacteria within the intestine, promoting improved host health [

5,

6] Several studies have demonstrated the potential of prebiotics to influence stress, anxiety, and depression, possibly through a reduction in perceived stress associated with changes in

Bifidobacterium spp. or other gut microbiota taxa [

5].

Synbiotics are formulated by combining probiotics and prebiotics in a synergistic manner [

1]. Towards my understanding, The primary objective of synbiotic supplementation is to enhance gut health by introducing beneficial bacteria (probiotics) and providing essential nutrients (prebiotics) to support their survival, growth, and activity within the digestive system.

Probiotic compositions typically include diverse strains of

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium. These bacteria have been shown to reduce inflammation and modulate immune responses by inhibiting the production of the cytokine IL-8 in human colon epithelial cells and decreasing intestinal permeability, thereby preventing endotoxemia [

1]. Prebiotics, such as dietary fiber, promote the growth of

Lactobacilli and

Bifidobacteria [

10]. Animal studies have demonstrated that supplementation with probiotic

Bifidobacterium infantis can alleviate experimentally induced stress and depression in rats, while a 28-day course of

Lactobacillus rhamnosus supplementation has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms in humans [

1]. A diet high in glucose, fructose, and sucrose can significantly alter the gut microbiota composition, characterized by a dramatic increase in

Bifidobacterium and a substantial decrease in

Bacteroides. Studies in mice fed a fructose-rich diet have shown significant increases in

Coprococcus,

Ruminococcus, and

Clostridium, while simultaneously observing a reduction in the

Clostridiaceae family [

17].

4. Mechanism of Action

4.1. Neuroimmune Modulation

Neuroinflammation, characterized by the activation of nerve cells within the central nervous system, leads to changes resembling neuronal degeneration [

20]. This intricate process involves complex interactions between the immune and neurological systems, primarily mediated by glial cells such as microglia and astrocytes [

28]. Neuroinflammation can be triggered by various factors, including infections, physical trauma, and the accumulation of abnormal proteins like amyloid-beta (Aβ) observed in neurodegenerative diseases [

57]. When activated, glial cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can exacerbate neuronal damage if the inflammatory response persists [

57]. Conversely, neuroimmune regulation, characterized by bidirectional communication between the nervous and immune systems, plays a crucial role in modulating both inflammatory responses and neuronal function. Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of neuroimmune regulation in controlling neuroinflammation by limiting excessive microglial activation, maintaining cytokine balance, and preserving the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [

28].

Current hypotheses suggest that probiotics exert their influence on the gut-brain axis by modulating inflammation, producing neurotransmitters, and enhancing gut barrier function. While some studies have shown promising effects on mood and anxiety, this area of research is still in its early stages [

42]. Neuroimmune modulation, a critical process involving complex bidirectional communication between the central nervous system, immune system, and endocrine system, influences various physiological and pathological conditions, including major depressive disorder, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and cancer [

33]. The gut-brain axis serves as a crucial communication pathway for neurological, hormonal, and immunological signals.

Gut microorganisms produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which regulate immune cells such as T-cells and microglia, influencing neuroinflammation. The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in maintaining immune homeostasis, influencing both innate and adaptive immune responses while balancing pathogen clearance and self-tolerance to prevent autoimmunity [49, 52]. These bacteria interact with the immune system and modulate neuroinflammation, a key factor in the pathophysiology of depression.

In the human host, the gut microbiota functions as a "superorganism," playing vital roles in food absorption, synthesizing beneficial compounds, protecting against infections, maintaining intestinal epithelial cell integrity, and modulating host immunity. In healthy individuals, the gut microbiota exists in a balanced state known as "eubiosis." However, during illness, this balance can be disrupted, leading to "dysbiosis," characterized by a decline in beneficial commensal bacteria, an increase in opportunistic pathogens, or a combination of both. Dysbiosis, characterized by alterations in the diversity and abundance of the gut microbial population, has been implicated in a range of human disorders. Studies in both humans and animals have demonstrated associations between gut dysbiosis and immune system dysregulation, abnormal brain protein aggregation, inflammation, and impaired neuronal and synaptic maturation [

49].

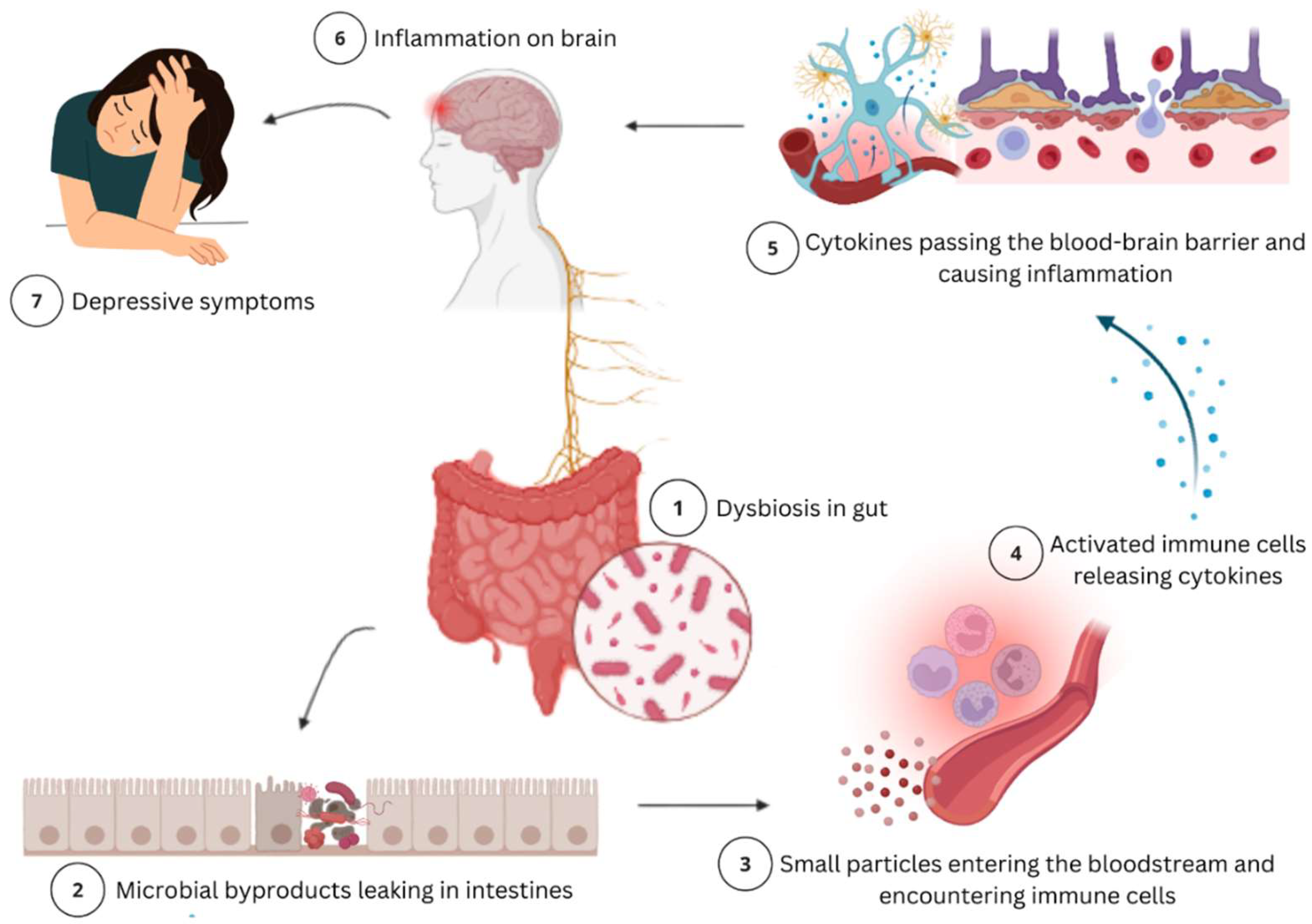

Immune signaling, directly influenced by gut microbiota composition and health, plays a critical role in gut-brain communication. Dysbiosis can compromise the intestinal barrier, allowing bacterial byproducts and inflammatory chemicals to enter the circulation. This triggers immune cells to produce cytokines, which can cross the blood-brain barrier, inducing neuroinflammation and contributing to neurological disorders [

12], including MDD [

18]. Chronic inflammation can disrupt neurotransmitter balance and contribute to the development of depressive symptoms [

16].

Circadian rhythm disruption can increase the risk of intestinal dysbiosis, potentially contributing to the development of various inflammatory and metabolic diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases [

49]. Chronic circadian disruption may impair neurogenesis in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for mood regulation that is frequently compromised in depression. Notably, individuals with depression often exhibit reduced hippocampal volume [

19].

Studies on the human microbiome suggest that the microbiota-gut-brain axis may contribute to mental disorders like depression through an inflammatory state associated with increased intestinal permeability. Research indicates that gut bacteria can influence brain function by modulating the behavior and severity of neurological diseases. This intricate communication system involves a complex bidirectional interaction of neurological, hormonal, metabolic, and immunological pathways [

44].

The gut-brain axis describes the bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system. Alterations in gut microbiota composition can significantly impact neuroinflammation, an emerging risk factor for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Individuals with inflammatory depression exhibit higher levels of Bacteroides and lower levels of Clostridium, which correlate with elevated levels of inflammatory markers [30, 56]. For instance, studies have shown that inflammatory cytokines released in response to dysbiosis can activate microglia within the CNS, leading to increased neuroinflammation and subsequent alterations in brain structure and function [20, 30].

Depressive symptoms can arise from elevated cytokine levels resulting from both peripheral chronic inflammation and central microglial activation. Peripheral stimuli, including inflammation, chronic stress, and infection, can activate microglia in the brain, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

20]. Neuroinflammation contributes to the pathophysiology of depression through various mechanisms, including increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production, activation of the HPA axis, glucocorticoid resistance, altered serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine synthesis and metabolism, increased neuronal apoptosis, and impaired neurogenesis and neuroplasticity [

20]. Individuals with inflammatory depression exhibit higher levels of Bacteroides and lower levels of Clostridium, which correlate with elevated levels of inflammatory markers [30, 56].

4.2. Neurotransmitter production

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that facilitate communication between neurons by transmitting signals across synapses, regulating functions such as movement, emotion, and memory. These chemical messengers can either excite or inhibit neural activity. Certain neurotransmitters participate in reciprocal interactions with the gut microbiota, with microbial control over precursor molecules influencing neurotransmitter production [

15]. The gut plays a significant role in neurotransmitter production, particularly serotonin, which is strongly associated with mood regulation [

42]. The gut microbiota can regulate neurotransmitter synthesis through various mechanisms, including the production of precursors, catalyzing synthesis through food metabolism, or a combination of these processes. Metabolites from certain bacterial species can act as signaling molecules, stimulating neurotransmitter production and release by enteroendocrine cells. For instance, metabolites from spore-forming bacteria can enhance serotonin production by upregulating the expression of the rate-limiting gene TPH1 in enterochromaffin cells [

15]. Probiotic supplementation may increase the gut's synthesis of serotonin and other neurotransmitters, which can subsequently interact with the brain via the vagus nerve, influencing mood and emotional regulation [

42].

Recent studies have shown that nearly 90% of serotonin is produced peripherally, primarily by enterochromaffin cells in the intestinal epithelium, and does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier. However, tryptophan, a serotonin precursor, can. Neurotransmitters such as glutamate, GABA, dopamine, and serotonin cannot directly cross the blood-brain barrier and must be synthesized within the brain from locally available precursors. These precursors, primarily amino acids like tyrosine and tryptophan, enter circulation, cross the blood-brain barrier, and are subsequently taken up by neurotransmitter-producing cells [

15].

Enterochromaffin cells in the digestive system utilize tryptophan from dietary proteins to synthesize serotonin, a process regulated by the bacterial kynurenine pathway [

15]. The kynurenine pathway is closely linked to the inflammatory model of depression. Inflammatory molecules, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), activate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), diverting tryptophan metabolism towards kynurenine production, thereby reducing serotonin synthesis and increasing neurotoxic effects [

44]. Dietary tryptophan, upon digestion, is released into the small intestine, where it can enter circulation for uptake by host cells, be converted to serotonin by enterochromaffin cells, or be metabolized through the kynurenine pathway [

34]. Gut microorganisms convert a small portion of unabsorbed tryptophan into indole derivatives, essential for bacterial communication and survival. Serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), is a monoamine neurotransmitter derived from tryptophan through a conversion catalyzed by tryptophan hydroxylase. It plays a crucial role in regulating various physiological functions, including mood, body temperature, pain perception, hunger, circadian rhythm, sexual behavior, memory, and stress response. Several bacterial species, including Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Klebsiella, and Escherichia coli, have been demonstrated to produce serotonin via tryptophan synthetase [

34].

4.3. Vagus Nerve Pathways

The vagal sensory pathway is crucial for gut-brain communication [

11]. The vagus nerve, a key component of this pathway, transmits signals originating from the gut and is implicated in various gastrointestinal, neurological, and immunological disorders [

54]. Vagal sensory neurons residing in the nodose ganglia possess branching axons. The vagus nerve, the longest cranial nerve, extends through the thorax and abdomen, innervating organs such as the heart, lungs, pancreas, liver, and stomach, enabling the detection of signals from these organs [

11].

The vagus nerve, a key component of the parasympathetic nervous system, is a mixed nerve predominantly composed of afferent (sensory) fibers (80%) and efferent (motor) fibers (20%) [

7]. Afferent fibers transmit sensory information from the stomach to the brain, including the status of internal organs and chemical and mechanical signals from the gut. These fibers connect to various brain regions, notably the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS), which acts as a processing center for this sensory information [

4]. This channel allows the brain to receive information about gut status, which can influence mood and behavior. Sensory information from the stomach is transmitted to the central nervous system (CNS) via afferent vagal fibers originating from the nodose ganglia and dorsal root ganglia (DRG), while gut-derived hormones, neurotransmitters, inflammatory signals, and immunological signals enter the brain through the circulatory system [

54].

Efferent pathways transmit signals from the brain to the stomach, controlling immunological responses, secretion, and motility. Efferent vagal fibers specifically convey signals from the brain to the stomach, regulating its activity, including glandular secretion and smooth muscle contraction [

8]. These signals can also influence gut microbiota composition and function, impacting cognition and mood, while contributing to homeostasis by adjusting digestive processes based on physiological needs [

4]. Efferent vagal pathways also modulate gut inflammatory responses, contributing to immune system regulation through mechanisms such as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway [

7].

The vagus nerve, through its interactions with both the CNS and the ENS, facilitates a dynamic feedback loop influenced by microbial activity. The gut microbiota can modulate vagal afferent signaling by producing compounds that stimulate these sensory pathways. This enables gut health to influence mental health through neurochemical communication [

7]. Furthermore, In response to signals received from the stomach via vagal afferents, the CNS can initiate appropriate responses through efferent pathways, such as adjusting digestive activities or regulating stress responses [8, 4].

Early research demonstrated a strong association between various neurological disorders and digestive issues in human patients, highlighting the critical role of the gut-brain axis not only in appetite regulation and intestinal immunity but also in cognitive function [

54]. Chronic early-life stress in rats can induce dysbiosis by altering intestinal permeability, potentially increasing susceptibility to visceral hypersensitivity in adulthood. Stress often suppresses vagal nerve activity while simultaneously activating the sympathetic nervous system through autonomic projections from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve and sympathetic preganglionic neurons of the spinal cord [

7]. Functional neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) influences the activity of various cortical and subcortical brain regions. The vagus nerve exhibits structural connections with several mood-regulating limbic and cortical brain areas, either directly or indirectly through the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS). Consequently, in chronic VNS therapy for depression, positron emission tomography (PET) scans revealed reduced resting brain activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), a brain region that projects to the amygdala and other emotion-regulating brain areas [

8].

Research has demonstrated that Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) can offer significant benefits to individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Longitudinal studies have shown that patients can experience gradual recovery over time, with some reporting long-term improvements following the initial treatment period [

37]. A large study involving 60 individuals indicated that approximately 40% responded favorably to VNS after 10 weeks of treatment, with sustained long-term benefits [45 Functional MRI studies have revealed alterations in brain activity associated with VNS treatment. These findings suggest that VNS may inhibit the activity of certain brain regions implicated in depression, contributing to its therapeutic efficacy [

37].

Figure 1.

The mechanism of action of gut-brain axis and its role in depression.

Figure 1.

The mechanism of action of gut-brain axis and its role in depression.

5. Demographic Differences in Gut Microbiota and Depression

Recent research has focused on the complex interplay between gut microbiota, sex, age, and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Given the significant sex-based differences in MDD incidence, growing evidence suggests that variations in gut microbiota composition may contribute to these disparities. Studies have consistently shown that MDD patients exhibit alterations in their gut microbiota composition, a condition known as dysbiosis. A comprehensive scoping review identified five studies that reported significant differences in both alpha and beta diversity of gut microbiota in male and female MDD patients compared to healthy controls [

39].

Studies have shown that certain bacterial groups are more prevalent in women than in men. For instance, women with MDD exhibit higher relative abundances of specific bacteria compared to men under similar conditions [

39]. Female patients may experience unique alterations in bacterial populations that correlate with the severity of their depressive symptoms, a phenomenon less frequently observed in men [24 Research has demonstrated that females with MDD exhibit higher levels of certain bacterial taxa, such as

Actinobacteria, while lower levels of

Bacteroidetes were observed in males with MDD [

14]. Correlation analyses revealed that specific bacterial taxa were associated with the severity of depression symptoms, with unique patterns observed between sexes. This suggests that sex-specific processes may influence how the gut microbiota impacts mood disorders [

39]. These findings highlight the importance of considering sex in the diagnosis and treatment of MDD. Microbial markers hold potential as diagnostic tools, emphasizing the need for sex-stratified analyses in understanding MDD pathogenesis [

39].

Research on age-related changes in the gut microbiota of MDD patients has revealed significant differences between young adults (18-29 years) and middle-aged individuals (30-59 years). Young MDD patients exhibited lower levels of

Firmicutes and higher levels of

Bacteroidetes, while the opposite trend was observed in middle-aged individuals [

13]. A study of young adults with depression found that several bacterial taxa, particularly

Neisseria spp. and

Prevotella nigrescens, were significantly more abundant in depressed participants compared to healthy controls [

51].

The oral microbiome composition also differed significantly, with 21 bacterial species exhibiting altered abundance, suggesting a complex interplay between the oral and gut microbiota in mental health [

51]. These findings suggest that alterations in the oral microbiota may contribute to the etiology of depression. The increased prevalence of certain taxa, such as

Neisseria and

Prevotella, may reflect underlying inflammatory processes or other mechanisms associated with mood disorders [

27].

Certain gut microbial alterations have been associated with gastrointestinal symptoms and depressed mood in the elderly population, particularly those experiencing late-life depression. While specific taxa potentially contributing to these symptoms have been identified, taxonomic changes are less well-defined compared to younger cohorts [

35]. Older adults exhibit distinct patterns of microbial diversity and abundance compared to younger individuals. For instance, levels of beneficial bacteria such as

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium decline with age, a factor linked to an increased risk of depression [

29]. The gut-brain axis is crucial for understanding how these bacteria influence mood disorders across all age groups. Younger individuals may exhibit more pronounced alterations in specific taxa due to lifestyle factors, while older individuals may be more significantly impacted by cumulative health issues and age-related changes in microbiota composition [

55].

Furthermore, studies have shown an association between BMI and gut microbiota composition. Individuals with higher BMI tend to exhibit lower microbial diversity, which may contribute to metabolic issues and alterations in gut-brain communication pathways [

17]. Additionally, ethnicity significantly influences dietary habits and lifestyle choices, key factors in shaping the gut microbiota. Research has identified distinct microbial profiles across different ethnic groups, reflecting variations in diet, environment, and genetics [

43]. Furthermore, the distinction between urban and rural living environments can significantly influence lifestyle factors such as diet, stress levels, and exposure to environmental bacteria, all of which contribute to shaping the gut microbiome. Urbanization has been associated with decreased intra-individual gut microbiota diversity and increased inter-individual variability [

43].

6. Limitation of Current Studies on the Gut-Brain Axis

While research into the interaction between gut microbiota and brain health continues to advance, several challenges hinder our complete understanding of this complex relationship. A major concern is the use of small sample sizes in human studies, which limits statistical power and the generalizability of findings. Furthermore, the significant heterogeneity in microbiota composition among individuals, influenced by factors such as diet, location, lifestyle, and genetics, poses a significant challenge in drawing broad conclusions regarding the gut-brain axis. This variability limits the identification of consistent microbial patterns associated with mental health disorders.

An additional limitation is the lack of standardization in the probiotic and prebiotic therapies employed across different studies. Variations in the type, dosage, and duration of treatments result in inconsistent findings, hindering the identification of optimal strategies for modulating the gut-brain axis. Furthermore, most studies have focused on correlational data rather than establishing causal relationships, and the specific mechanisms by which gut bacteria influence brain function and behavior remain largely elusive. To overcome these limitations, larger, well-controlled studies utilizing standardized methodologies, along with multidisciplinary collaboration between microbiologists, neurologists, and clinicians, are crucial to bridge the gap between research and clinical practice.

7. Future Directions and Clinical Translation

Advancing gut-brain axis research necessitates overcoming current obstacles and translating findings into meaningful therapeutic applications. A primary objective is to develop microbiome-based biomarkers for depression, with the potential to revolutionize diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. This endeavor is hindered by significant inter-individual heterogeneity in gut microbiota composition, compounded by the dynamic nature of the microbiome, which is influenced by factors such as diet, medications, and environmental conditions. Identifying persistent and reproducible microbial patterns associated with depression will require extensive longitudinal research and sophisticated bioinformatic techniques capable of integrating diverse biological data.

Another promising avenue involves the development of personalized therapies targeting individual gut dysbiosis patterns. Tailoring prebiotic, probiotic, or nutritional interventions to an individual's unique microbial profile and metabolic needs may enhance the efficacy of gut-based depression treatments. However, achieving this level of precision necessitates a deeper understanding of the causal relationships between specific microbial species, metabolites, and psychological outcomes. Advances in technologies such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and machine learning are crucial for realizing personalized gut-brain therapeutics.

To facilitate clinical adoption, it is crucial to address regulatory and ethical challenges surrounding microbiota-targeted therapeutics, including intervention standardization, long-term safety assessments, and equitable access to these novel treatments. By addressing research gaps and fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, the field can move closer to harnessing the gut-brain axis for innovative and personalized mental healthcare interventions.

8. Conclusions

The intricate interplay between the digestive system and the mind, mediated by the gut-brain axis, offers a promising avenue for understanding and treating Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Emerging research highlights the crucial role of intestinal bacteria in mental health, encompassing their involvement in neurotransmitter synthesis, immune system regulation, and maintaining intestinal barrier integrity. Microbial imbalance within the gut has consistently been linked to increased inflammation, altered neurotransmitter production, and HPA axis dysregulation, all of which contribute to the underlying pathophysiology of depression.

Novel, non-invasive treatment approaches targeting the gut microbiota, such as probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics, offer a promising strategy for mitigating depression symptoms. Mechanisms including short-chain fatty acid production, vagal nerve pathways, and neuroimmune regulation underscore the significance of the gut-brain axis in maintaining mental well-being. While significant progress has been made, further research is necessary to identify the precise microbial composition associated with depression and develop personalized therapies to restore microbial balance and enhance clinical outcomes. Integrating microbiome-based approaches into existing treatment regimens may lead to more comprehensive and effective depression care, potentially paving the way for novel mental health therapies.

Despite advancements, significant research gaps and limitations must be addressed to fully realize the therapeutic potential of the gut-brain axis. Developing microbiota-based biomarkers for depression remains challenging due to significant inter-individual variability in microbial composition influenced by factors such as diet, geography, genetics, and lifestyle. Identifying reliable microbial fingerprints requires extensive longitudinal studies and sophisticated bioinformatic approaches capable of integrating diverse datasets. Furthermore, the lack of standardized methodologies for probiotic and prebiotic therapies has resulted in inconsistent study findings, hindering efforts to determine their therapeutic efficacy. The future of gut-brain axis research lies in developing personalized therapies based on unique gut dysbiosis profiles. Precision medicine approaches utilizing advanced metagenomics and metabolomics may enable the tailoring of gut-targeted therapies to an individual's specific microbial composition and metabolic state. Furthermore, research should focus on elucidating the causal mechanisms underlying microbiota-depression linkages, rather than solely on correlations, to identify actionable treatment targets.

Combining gut microbiota research with conventional therapies will be crucial for enhancing therapeutic efficacy. Antidepressants, psychotherapy, and lifestyle modifications remain essential for depression management; however, their effectiveness varies significantly across individuals. Integrating these standard approaches with microbiota-targeted therapies may improve therapeutic outcomes, minimize treatment resistance, and potentially reduce reliance on pharmaceuticals, thereby mitigating adverse effects. By adopting a comprehensive approach that integrates microbiome research with existing treatment modalities, the field can pave the way for personalized multimodal approaches for effectively managing Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

To ensure clinical implementation, regulatory, safety, and ethical considerations must be addressed. Standardizing treatments, ensuring long-term safety, and enhancing accessibility are crucial steps towards integrating microbiome-based therapies into mainstream mental healthcare. By overcoming these challenges, future research may unveil transformative approaches for managing MDD through the gut-brain axis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.A. and M.D.C.R.; literature search, Z.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.A.; writing—review and editing, M.D.C.R., Z.M.H., C.M.N.C.M.N., N.S.; supervision, M.D.C.R.; project administration, M.D.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

In the preparation of this work, we utilized AI-assisted tools, including ChatGPT, PaperPal, GeminiAI, and QuillBot. These tools were employed to support the initial drafting and refinement of specific sections of the manuscript and to enhance academic language. All AI-generated content underwent rigourous review and extensive editing by the authors to guarantee accuracy, scientific rigour, and compliance with academic writing standards. The authors bear full responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript, including any portions generated by AI tools, and are accountable for any violations of publication ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDD |

Major depressive disorder |

| GBA |

Gut-brain axis |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| HPA |

Hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal |

| SCFA |

Short-chain fatty acid |

| ENS |

Enteric nervous system |

| BDNF |

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| BBB |

Blood-brain barrier |

| GABA |

Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IDO1 |

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 |

| 5-HT |

5-hydroxytryptamine |

| NTS |

Nucleus tractus solitarii |

| DRG |

Dorsal root ganglia |

| VNS |

Vagus nerve stimulation |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| vmPFC |

Ventromedial prefrontal cortex |

| TRD |

Treatment-resistant depression |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

References

- Alli, S. R. , Gorbovskaya, I., Liu, J. C. W., Kolla, N. J., Brown, L., & Müller, D. J. The gut microbiome in Depression and Potential benefit of prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics: A Systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, I. , Dey, S., Raut, A. J., Katta, S., & Sharma, P. Exploring the Gut-Brain Axis: a comprehensive review of interactions between the gut microbiota and the central nervous system. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research. [CrossRef]

- Belmaker, R. , & Agam, G. Major depressive disorder. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 358, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H. , Albaugh, V. L., & Neuhuber, W. L. Gut-brain communication and obesity: understanding functions of the vagus nerve. Journal of Clinical Investigation. [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A. , Campaniello, D., Speranza, B., Racioppo, A., Sinigaglia, M., & Corbo, M. R. An update on prebiotics and on their health effects. Foods 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindels, L. B. , Delzenne, N. M., Cani, P. D., & Walter, J. Towards a more comprehensive concept for prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2015, 12, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B. , Bazin, T., & Pellissier, S. The vagus nerve at the interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain axis. Frontiers in Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Breit, S. , Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G., & Hasler, G. Vagus nerve as modulator of the Brain–Gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M. , Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015, ). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih. 1 June 4367. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J. L. , Erickson, J. M., Lloyd, B. B., & Slavin, J. L. Health effects and sources of prebiotic dietary fiber. Current Developments in Nutrition 2018, 2, nzy005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y. , Li, R., & Bai, L. Vagal sensory pathway for the gut-brain communication. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 2023, 156, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P. R. The role of gut microbiota in health and disease: Implications for therapeutic interventions. Universal Research Reports 2024, 11, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , He, S., Fang, L., Wang, B., Bai, S., Xie, J., Zhou, C., Wang, W., & Xie, P. Age-specific differential changes on gut microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Aging 2020, 12, 2764–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. , Zheng, P., Liu, Y., Zhong, X., Wang, H., Guo, Y., & Xie, P. Sex differences in gut microbiota in patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2018, 14, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. , Xu, J., & Chen, Y. Regulation of neurotransmitters by the gut microbiota and effects on cognition in neurological disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J. , Hu, H., Ju, Y., Liu, J., Wang, M., Liu, B., & Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and depression: deep insight into biological mechanisms and potential applications. General Psychiatry 2024, 37, e101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J. F. , O’Riordan, K. J., Cowan, C. S. M., Sandhu, K. V., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Boehme, M., Codagnone, M. G., Cussotto, S., Fulling, C., Golubeva, A. V., Guzzetta, K. E., Jaggar, M., Long-Smith, C. M., Lyte, J. M., Martin, J. A., Molinero-Perez, A., Moloney, G., Morelli, E., Morillas, E.,... Dinan, T. G. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain axis. Physiological Reviews 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabboussi, N. , Debs, E., Bouji, M., Rafei, R., & Fares, N. Balancing the Mind: Toward a Complete Picture of the Interplay between Gut Microbiota, Inflammation and Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Research Bulletin 2024, 216, 111056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, M. , Verhoeve, S. I., Van Der Wee, N. J., Van Hemert, A. M., Vreugdenhil, E., & Coomans, C. P. The role of the circadian system in the etiology of depression. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2023, 153, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrensel, A. , Ünsalver, B. Ö., & Ceylan, M. E. Neuroinflammation, Gut-Brain axis and depression. Psychiatry Investigation 2019, 17, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. A. , Baker, G. B., & Dursun, S. M. (2021b). The relationship between the gut Microbiome-Immune System-Brain axis and major depressive disorder. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M. , Wang, J., Liu, P., Tu, H., Zhang, R., Zhang, Y., Sun, N., & Zhang, K. Gut microbiota composition in depressive disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Translational Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Hao, W. , Ma, Q., Wang, L., Yuan, N., Gan, H., He, L., Li, X., Huang, J., & Chen, J. Gut dysbiosis induces the development of depression-like behavior through abnormal synapse pruning in microglia-mediated by complement C3. Microbiome. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. , Li, Y., Wu, J., Zhang, H., Huang, Y., Tan, X., Wen, L., Zhou, X., Xie, P., Olasunkanmi, O. I., Zhou, J., Sun, Z., Liu, M., Zhang, G., Yang, J., Zheng, P., & Xie, P. Changes of gut microbiota reflect the severity of major depressive disorder: a cross sectional study. Translational Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. V. Gut microbiome composition and diversity are related to human personality traits. Human Microbiome Journal 2019, 15, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M. , & Fukudo, S. (2023). Gut–brain interactions. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 312–333). [CrossRef]

- Kerff, F. , Pasco, J. A., Williams, L. J., Jacka, F. N., Loughman, A., & Dawson, S. L. (2024). Associations between oral microbiota pathogens and elevated depressive and anxiety symptoms in men. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). [CrossRef]

- Kölliker-Frers, R. , Udovin, L., Otero-Losada, M., Kobiec, T., Herrera, M. I., Palacios, J., Razzitte, G., & Capani, F. Neuroinflammation: An integrating overview of Reactive-Neuroimmune cell interactions in health and disease. Mediators of Inflammation 2021, 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. , Pramanik, J., Goyal, N., Chauhan, D., Sivamaruthi, B. S., Prajapati, B. G., & Chaiyasut, C. Gut microbiota in Anxiety and Depression: Unveiling the relationships and management options. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. , Liu, Z., Wang, J., Wang, J., Gao, M., Zhang, Y., Yang, C., Zhang, A., Li, G., Li, X., Liu, S., Liu, L., Sun, N., & Zhang, K. Immunoregulatory role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory depression. Immunoregulatory role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory depression. Nature Communications 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. T. , Rowan-Nash, A. D., Sheehan, A. E., Walsh, R. F., Sanzari, C. M., Korry, B. J., & Belenky, P. Reductions in anti-inflammatory gut bacteria are associated with depression in a sample of young adults. Brain Behavior and Immunity 2020, 88, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuy-Aubert, V. , & Ravussin, Y. Short chain fatty acids: the messengers from down below. Frontiers in Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. I. , Sá, S. I., Carmo, H., Carvalho, F., & Silva, J. P. Pharmaceutical-mediated neuroimmune modulation in psychiatric/psychological adverse events. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2024, 135, 111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhanna, A. , Martini, N., Hmaydoosh, G., Hamwi, G., Jarjanazi, M., Zaifah, G., Kazzazo, R., Mohamad, A. H., & Alshehabi, Z. The correlation between gut microbiota and both neurotransmitters and mental disorders: A narrative review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyaho, K. , Sanada, K., Kurokawa, S., Tanaka, A., Tachibana, T., Ishii, C., Noda, Y., Nakajima, S., Fukuda, S., Mimura, M., Kishimoto, T., & Iwanami, A. The Potential Impact of Age on Gut Microbiota in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Secondary Analysis of the Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morys, J. , Małecki, A., & Nowacka-Chmielewska, M. Stress and the gut-brain axis: an inflammatory perspective. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. [CrossRef]

- Nahas, Z. , Teneback, C., Chae, J., Mu, Q., Molnar, C., Kozel, F. A., Walker, J., Anderson, B., Koola, J., Kose, S., Lomarev, M., Bohning, D. E., & George, M. S. Serial Vagus Nerve Stimulation Functional MRI in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007, 32, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhal, M. M. , Yassin, L. K., Alyaqoubi, R., Saeed, S., Alderei, A., Alhammadi, A., Alshehhi, M., Almehairbi, A., Houqani, S. A., BaniYas, S., Qanadilo, H., Ali, B. R., Shehab, S., Statsenko, Y., Meribout, S., Sadek, B., Akour, A., & Hamad, M. I. K. The Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and Neurological Disorders: A Comprehensive review. Life 2024, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemela, L. , Lamoury, G., Carroll, S., Morgia, M., Yeung, A., & Oh, B. Exploring gender differences in the relationship between gut microbiome and depression - a scoping review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H. , Jang, H., Kim, G., Zouiouich, S., Cho, S., Kim, H., Kim, J., Choe, J., Gunter, M. J., Ferrari, P., Scalbert, A., & Freisling, H. Taxonomic composition and diversity of the gut microbiota in relation to habitual dietary intake in Korean adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C. , Gold, S. M., Penninx, B. W., Pariante, C. M., Etkin, A., Fava, M., Mohr, D. C., & Schatzberg, A. F. Major depressive disorder. F. Major depressive disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmannia, M. , Poudineh, M., Mirzaei, R., Aalipour, M. A., Bonjar, A. H. S., Goudarzi, M., Kheradmand, A., Aslani, H. R., Sadeghian, M., Nasiri, M. J., & Sechi, L. A. Strain-specific effects of probiotics on depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Gut Pathogens 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. , Wu, J., Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Ren, J., Zhang, Z., Chen, B., Zhang, K., Zhu, B., Liu, W., Li, S., & Li, X. Lifestyle patterns influence the composition of the gut microbiome in a healthy Chinese population. Lifestyle patterns influence the composition of the gut microbiome in a healthy Chinese population. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Martínez, S. , Segura-Real, L., Gómez-García, A. P., Tesoro-Cruz, E., Constantino-Jonapa, L. A., Amedei, A., & Aguirre-García, M. M. Neuroinflammation, Microbiota-Gut-Brain axis, and Depression: the vicious circle. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience 2023, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackeim, H. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNSTM) for Treatment-Resistant Depression Efficacy, Side effects, and Predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001, 25, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardooi, A. R. , Reisi, P., & Yazdi, A. Protective effect of honey on learning and memory impairment, depression and neurodegeneration induced by chronic unpredictable mild stress. Physiology and Pharmacology 2020, 25, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y. P. , Bernardi, A., & Frozza, R. L. The role of Short-Chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in Gut-Brain communication. Frontiers in Endocrinology. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. , Vanlallawmzuali, N., Singh, A., Biswal, S., Zomuansangi, R., Lalbiaktluangi, C., Singh, B. P., Singh, P. K., Vellingiri, B., Iyer, M., Ram, H., Udey, B., & Yadav, M. K. Microbiota-Brain Axis: Exploring the role of gut microbiota in psychiatric disorders - A Comprehensive review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2024, 97, 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, H. , Arbab, S., Tian, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, C., Li, Q., & Li, K. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and host immune system and its response to traumatic injury. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and host immune system and its response to traumatic injury. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, T. R. X. RELATIONSHIP OF GUT MICROBIOTA AND MENTAL HEALTH: THE INFLUENCE OF THE GUT-BRAIN AXIS. International Journal of Health Science 2024, 4, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, B. , Lapsley, C., McDowell, A., Miliotis, G., McLafferty, M., O’Neill, S. M., Coleman, S., McGinnity, T. M., Bjourson, A. J., & Murray, E. K. Variations in the oral microbiome are associated with depression in young adults. K. Variations in the oral microbiome are associated with depression in young adults. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. , & Wu, E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R. , Li, J., Cheng, J., Zhou, D., Wu, S., Huang, S., Saimaiti, A., Yang, Z., Gan, R., & Li, H. The role of gut microbiota in anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders as well as the protective effects of dietary components. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. D. , Xu, Q. J., & Chang, R. B. Vagal sensory neurons and gut-brain signaling. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2020, 62, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. , Yun, Y., An, H., Zhao, W., Ma, T., Wang, Z., & Yang, F. Gut microbiome composition associated with major depressive disorder and sleep quality. Gut microbiome composition associated with major depressive disorder and sleep quality. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. , Liu, P., Liu, Z., Wang, J., Wang, J., Gao, M., Zhang, Y., Yang, C., Zhang, A., Li, G., Li, X., Liu, S., Liu, L., & Sun, N. (2023). Gut microbiota characteristics and its immunoregulatory role in inflammatory depression: joint clinical and animal data. Research Square (Research Square). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , Xiao, D., Mao, Q., & Xia, H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P. , Zeng, B., Zhou, C., Liu, M., Fang, Z., Xu, X., Zeng, L., Chen, J., Fan, S., Du, X., Zhang, X., Yang, D., Yang, Y., Meng, H., Li, W., Melgiri, N. D., Licinio, J., Wei, H., & Xie, P. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Molecular Psychiatry 2016, 21, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).