1. Introduction

Clarithromycin is a semi-synthetic macrolide with a broad-spectrum of antimicrobial activity. The impact of critical illness and the associated altered organ function on clarithromycin pharmacokinetics has not been described and dosing recommendations are identical in critically and non-critically ill populations. We know that the pharmacokinetics of many antibiotics are highly variable during critical illness [

1]. Suboptimal pharmacokinetic exposure of antimicrobials has been shown to be associated with treatment failure [

2,

3] and optimising exposure to antibiotics, most notably beta-lactams, has demonstrated improved clinical outcomes in critically-ill patients who have an infection [

3].

The pharmacokinetics of oral clarithromycin in clinically well individuals has been described [

4,

5,

6]. The only published study in a critical care setting studied enteral administration of clarithromycin via nasogastric tube. In this study Fish and Abraham found adequate absorption and results comparable to those found in studies of healthy volunteers or less seriously unwell patients [

7]. The study excluded patients with organ dysfunction (specifically renal, hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction). We aimed to address this knowledge gap with a pharmacokinetic study of clarithromycin in critically ill adults.

Macrolide antibiotics exert bacteriostatic action through inhibition of protein synthesis. Clarithromycin displays broad spectrum activity against both Gram negative and Gram positive organisms and against Mycobacteria. It is commonly used to treat infections of the respiratory tract, skin and throat. Clarithromycin is usually used to cover for atypical infection or as an alternative agent in penicillin allergy. Clarithromycin is often used via oral or enteral administration. The intravenous route may be used if the enteral route is unavailable, and intravenous administration may be used preferentially in severe illness or unreliable enteral absorption. The major metabolite of clarithromycin, 14-OH-clarithromycin, also possesses potent antibiotic activity [

4].

Macrolides display concentration- and time-dependent activity and various pharmacokinetic (PK) – pharmacodynamic (PD) targets have been associated with efficacy. For example, Kays and Denys reported fraction of time above the mean inhibitory concentration (MIC) as a measure of clarithromycin efficacy against clinical

Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates [

8] and Novelli et al. (2002) found the ratio of the peak concentration compared to the MIC (Cmax/MIC) to be the best predictor of successful clarithromycin treatment in a murine thigh and peritonitis model [

9].

Tessier et al. (2002), performed a separate murine model of pneumococcal pneumonia, testing various PKPD indices. This study suggested that the ratio of exposure in 24 hours compared to MIC (AUC

0-24/MIC), which accounts for both time and concentration, was the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic index that best predicted the activity of clarithromycin, although correlation was similar for Cmax/MIC. This study demonstrated that a total AUC

0-24/MIC for total clarithromycin (not accounting for protein binding) of greater than 100 was associated with bactericidal activity and positive outcomes [

10]. Clarithromycin is approximately 80% bound to plasma proteins at therapeutic levels [

11], although binding reduces with increasing concentrations [

4]. Clinical targets have been defined as a free AUC

0-24/MIC of 25-35[

12], with some studies requiring a more conservative target of free AUC

0-24/MIC of at least 100 [

13].

Common organisms associated with pneumonia which may be treated by clarithromycin have differing clinical breakpoints for macrolides according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST).

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcal groups A, B, C and G and

Moraxella catarrhalis all have a sensitive and resistant breakpoint of 0.25 mg/L to macrolide antibiotics. For Staphylococcus spp. (including

S. aureus), the sensitive and resistant breakpoint is 1 mg/L [

14]. EUCAST note that clinical evidence for macrolide efficacy against

Haemophilus influenzae is conflicting, due to high spontaneous cure rates, but recommend use of the epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF) of 32 mg/L if testing is required.

Legionella pneumophila is an important cause of pneumonia and may cause critical illness. However, EUCAST notes that there is no established reference method, nor any documentation of clinical outcome related to antimicrobial susceptibility testing and there are no clinical breakpoints available for this organism.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is also an important cause of pneumonia for which there are no available breakpoints. EUCAST does not have available breakpoints for

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, which causes pneumonia, but the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) have published antimicrobial susceptibility testing guidance for human Mycoplasma spp., with MIC above 1 mg/L considered resistant and below 0.5 mg/L considered sensitive for macrolides[

15]. Of note, the incidence of macrolide-resistant

Mycoplasma pneumonia is increasing globally, particularly in eastern Asia[

16] and macrolide resistant strains usually have MIC above 16 mg/L[

15].

Clarithromycin inhibits CYP3A4 enzymes and may interact with co-administered drugs by reducing metabolism via this pathway and increasing exposure. It has also been shown to autoinhibit its own metabolism, particularly at higher doses [

6].

Alongside describing pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin, we aimed to explore the extent to which antimicrobial PK-PD targets are met with current dosing recommendations and to explore whether autoinhibition impacts on drug exposure in critically ill populations. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing intravenous clarithromycin pharmacokinetics in critically unwell adults.

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

139 samples were taken from 22 participants. 18 samples were excluded from 5 participants due to being taken during periods of renal replacement therapy. 121 pharmacokinetic samples from 19 participants were included in the analysis. Participant characteristics are summarised in

Table 1.

12 participants had periods requiring intubation and ventilation, with 14 having periods where they were spontaneously breathing. 5 patients required periods of non-invasive ventilation. 12 participants received vasopressor support during the study. 12 participants had a blood plasma pH below the normal physiological range of 7.35-7.45 at some point during the study period.

Patients included in this analysis were receiving intravenous clarithromycin at a dose of 500 mg 12-hourly. Most participants contributed 8 samples to the analysis, however 4 participants contributed 4 or fewer samples and not all participants had peak concentrations measured. The raw data is shown in

Figure 1 by participant.

2.2. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

A 2-compartment model was found to provide the best fit with parameter estimates shown in

Table 2.

Addition of albumin, creatinine, presence of liver disease, sex, height and age to parameters did not provide any significant improvement in model fit. Inter-occasional variability was tested but there was no evidence of auto-inhibition in this cohort of patients.

2.3. Evaluation Methods

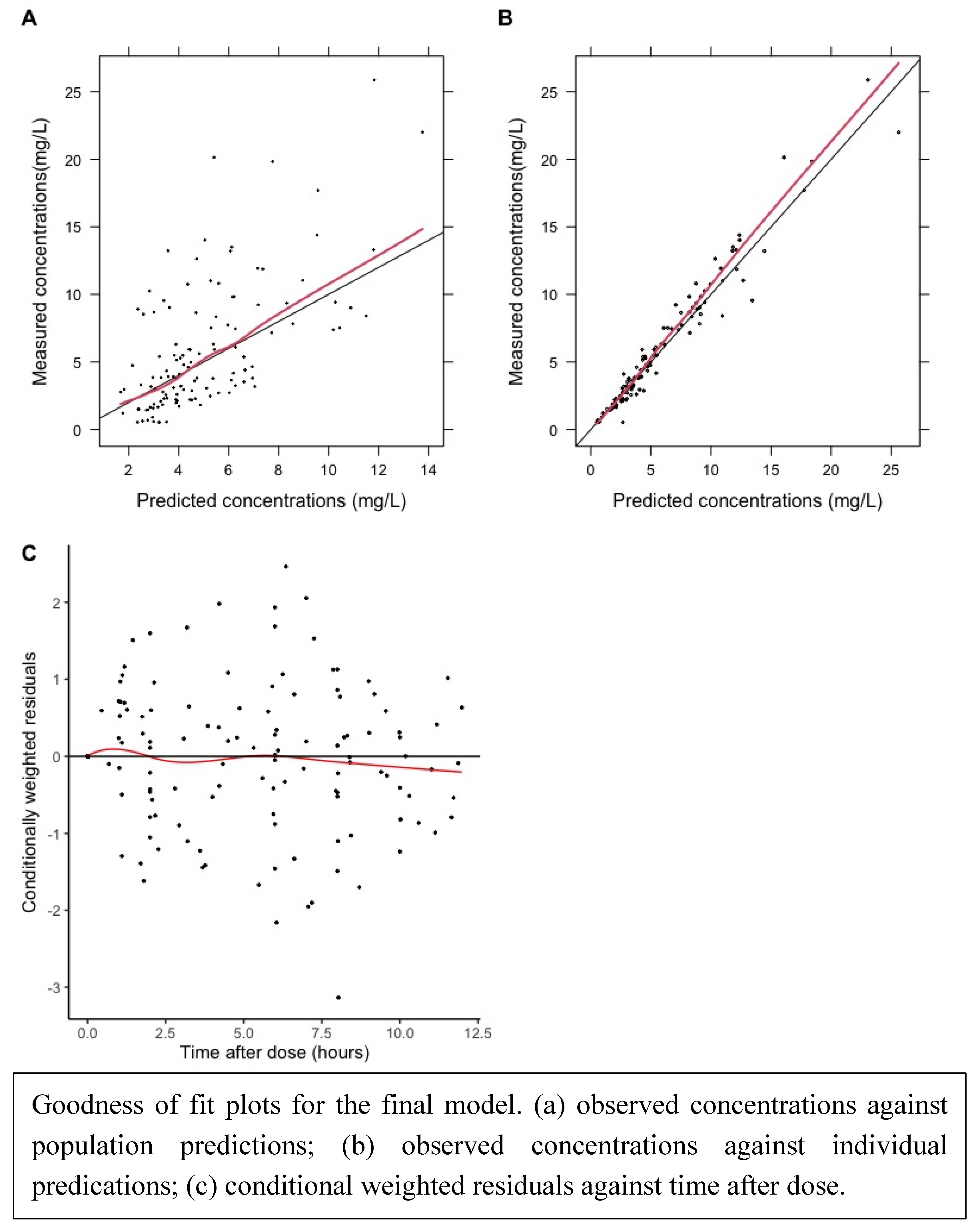

Goodness of fit plots and visual predictive curves demonstrated a reasonable fit of data.

Figure 2.

Goodness of fit plots.

Figure 2.

Goodness of fit plots.

Figure 3.

Visual Predictive Plot.

Figure 3.

Visual Predictive Plot.

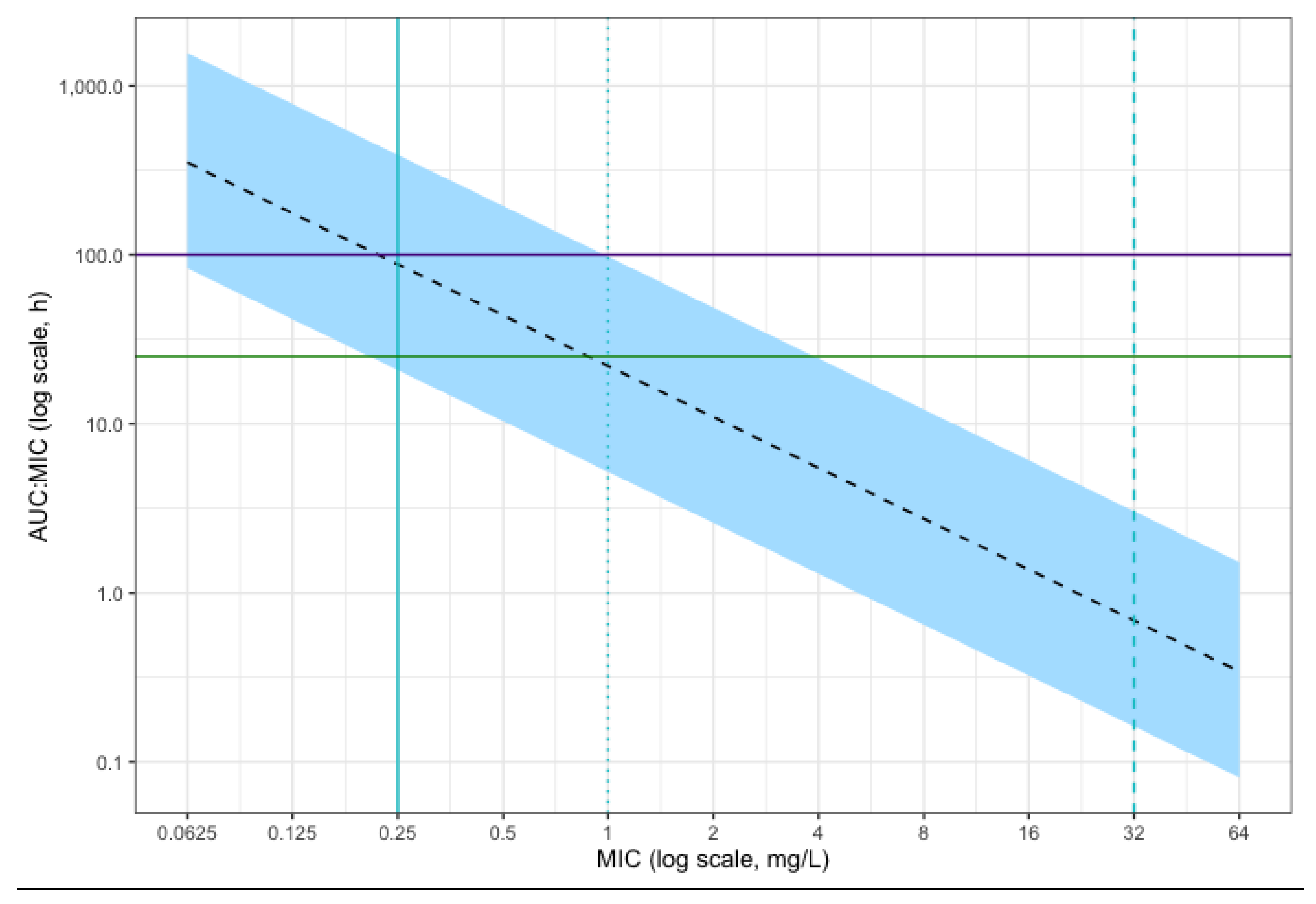

2.4. Simulations

Simulation of the 24 hour free AUC/MIC of 10,000 patients given a dose of intravenous clarithromycin of 500 mg twice daily is shown in

Figure 4. This suggested that the majority of simulated patients would achieve the conservative PKPD target of AUC

24/MIC above 100 for

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Moraxella catarrhalis and Streptococcal groups A, B, C and G isolates considered sensitive to macrolides. Target attainment is reduced for MICs approaching the resistant breakpoint for these organisms of 0.25 mg/L. All patients achieved the standard target of AUC

24/MIC > 25 for MIC below this resistant breakpoint.

At the higher MIC of 1 mg/L, the clinical breakpoint for Staphyloccocus spp. (including Staphylococcus aureus), less than 50% of simulated patients achieved the standard therapeutic target of AUC24/MIC > 25. For Mycoplasma pneumonia considered sensitive by CLSI methods (MIC below 0.5 mg/L), the majority of simulated patients achieved this target, but most patients did not achieve the higher target of AUC24/MIC > 100. For Haemophilus influenzae, Legionella pneumophila and Chlamydia pneumoniae there are no meaningful clinical breakpoints (the epidemiological cut-off of 32 mg/L is suggested as an alternative by EUCAST for H. influenzae, but the clinical utility of this is unclear). Therefore, meaningful target attainment cannot be estimated for these species.

3. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe intravenous clarithromycin PK in critically unwell adults. A 2-compartment model was found to provide the best fit to the data, supported by model evaluation methods which suggested a robust model fit.

Abduljalil et al. have previously demonstrated that autoinhibition of clarithromycin metabolism occurred within the first 48 hours of administration and modelled this using a separate inhibition compartment [

6]. We tested autoinhibition but did not find evidence of this effect in this population.

Median estimates for structural parameters are lower than previously reported values in the literature. Clearance of 8.2 L/h/70 kg is lower than previously reported estimates from oral models. Traunmüller et al. report separate parameters for healthy volunteers receiving different dosing regimens of 500 mg twice daily and 250 mg twice daily. The reported clearance for the standard regimen of 500 mg twice daily was 18.7 L/h [

5]. Fish and Abraham performed a study of clarithromycin administered via nasogastric tube in critical illness and found a clearance/bioavailability (CL/F) of 28.3 L/h on Day 1 and 27.5 L/h on Day 4 [

7]. Abduljalil et al. reported an apparent clearance of 60 L/h in healthy volunteers (bioavailability not measured/assumed) but this study also reported that autoinhibition reduced clearance to 10% of initial value (closer to our estimate) [

6]. Chu et al. examined clarithromycin PK in healthy volunteers and found a clearance/bioavailability of 46.8 L/h with a single 500 mg dose, reducing to 26.2 L/h by the 7th dose.

Volume of distribution at steady state in this study (86.3 L/70 kg) is lower than previously reported values [

5,

6,

7,

17]. Traunmüller et al. reported a volume of distribution of 126.5 L with no reference to bioavailability and with a dosing regimen of 500 mg twice daily[

5]. Fish and Abraham reported a volume of distribution of 176.3 L on Day 1 and 174.4 L on Day 4 [

7] and Abduljalil et al. reported a value of 172 L: both without reference to bioavailability. Chu et al. reported a volume of distribution with reference to bioavailability (V/f) of 306 L with a single 500 mg dose in healthy volunteers, reducing to 191 L at dose 7 [

17].

The findings demonstrate very high interindividual variability in structural parameters, particularly volume of the central compartment, with more than a 200-fold difference in parameter estimates between individual estimates from 3.1 to 766.4 L/70 kg. There was also a large range of clearance values between 2.1 L/hour/70 kg to 55.7 L/hour/ 70 kg. This high pharmacokinetic variability of antimicrobials in critical illness is in keeping with previous findings[

2].

Despite the highly variable PK, the probability of target attainment is high for the therapeutic target of AUC24/MIC > 25 for MIC of 0.25 mg/L and below (the resistant breakpoint for the majority of species with known clinical breakpoints and considered susceptible to macrolides). Above MIC of 0.25 mg/L, the probability of achieving this target decreases and less than 50% of simulated patients achieve this target at an MIC of 1 mg/L (the resistant breakpoint for Staphylococcal spp.). The majority of simulated patients also achieve a higher target of AUC24/MIC > 100 with MIC below 0.25 mg/L, but this probability reduces between MIC of 0.25 mg/L and 1 mg/L and no simulated patients achieve this target at the resistant breakpoint for Staphyloccal spp. of 1 mg/L. However, the rationale behind aiming for a higher target is unclear from available sources. Further study into PKPD targets for macrolide use in critical illness may be beneficial.

Importantly, clarithromycin is commonly used to cover the “atypical pathogens”: most commonly Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Of these, Legionella pneumophila and Chlamydia pneumoniae do not have known clinical breakpoints, and there is a lack of international consensus on antimicrobial susceptibility testing for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. PKPD target attainment for these organisms can therefore not be estimated.

Our findings can be compared to the study by Fish and Abraham (1999). This was a study of clarithromycin PK when administered via nasogastric tube in critically unwell patients [

7]. The APACHE II scores for disease severity are comparable between the two studies: Fish et al. studied a population with a median APACHE II of 19 and a range of 14 to 24; and our sample of patients had a median APACHE II of 20; range 0-28. However, this study examined oral clarithromycin in patients who were suitable for IV to oral switch and had no evidence of organ dysfunction, in particular renal, hepatic or GI dysfunction. In comparison, the majority of our participants were receiving vasopressor support during the study and there was significant variation in renal function and evidence of hepatic dysfunction in the population we studied. Therefore, the patients studied by Fish et al. could be considered to have a very different phenotype of critical illness compared to the patient population examined in our study. Fish et al. found limited intrapatient and interpatient variability of clarithromycin PK. In comparison, our findings show substantial variability between structural PK parameters for individuals. Fish et al. found no significant difference in secondary PK parameters between Day 1 and Day 4 of their study. Similarly, we found no evidence of interoccasional variability in our study.

This study has a number of limitations. There was relatively high uncertainty on parameter estimates in our model and a larger dataset may be more informative. We did not measure the metabolite 14-OH-clarithromycin which possesses antimicrobial activity. However, Abduljalil et al. (2019) have previously noted that AUC of clarithromycin is approximately three times as high as its metabolite, the majority of the antibiotic activity is likely to be derived from clarithromycin[

6]. As clarithromycin exposure significantly exceeded the target range in many patients, clarithromycin toxicity may have been a concern, which this study did not assess or model for. This study did not assess pharmacodynamic data, which would be necessary to clarify the PKPD target for clarithromycin in critical illness.

Our study suggests that, despite high interindividual pharmacokinetic variability, PKPD target attainment for clarithromycin in critically unwell patients is reasonable for most target organisms with known clinical breakpoints. When treating organisms with higher MIC, even if considered sensitive with known breakpoints, higher PKPD targets may not be achieved. Although the clinical breakpoints for many important pathogens that clarithromycin is commonly used to cover are not known, this investigation does illustrate the pharmacokinetic profile expected in critically unwell patients. The clinical utility for these “atypical” pathogens will emerge as understanding of these organisms develops.

Clarity over clinical breakpoints for relevant organisms, PKPD targets and correlation with treatment success is needed to define optimal clarithromycin dosing.

4. Materials and Methods

Participants were enrolled in the ABDose study. The methods for this study have been previously described in detail [

18,

19]. Briefly, adults who were receiving intravenous clarithromycin were recruited from the critical care unit of St. George’s Hospital in London, United Kingdom. Exclusion criteria included previous enrolment in the ABDose study, treatment withdrawal for palliation or expected prognosis of less than 48 hours from enrolment. Informed consent, or next of kin assent in cases of temporary incapacity due to critical illness, was obtained. In cases of assent, informed consent was obtained once participants regained capacity. Ethical approval was given by the national research ethics committee London (REC reference 14/LO/1999) and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was sponsored by the St George’s University of London (Joint research office reference 14.0195).

Data was collected from clinical notes, including baseline demographic data and clinic information. Drug administration data was collected from electronic prescriptions and infusion pumps to ensure accuracy in administration times. Clarithromycin is usually given as an infusion over 1-2 hours in local clinical practice. Sampling was based on the indicative schedule in

Table 3, but a pragmatic and opportunistic strategy was employed, timing samples with clinical collection as far as possible. A maximum of 8 samples was taken from any 1 participant. Blood samples were taken from radial arterial lines, placed immediately upon ice and plasma separated by centrifugation. Samples were stored at -80 °C and batch analysis of total drug concentrations were performed by Analytical Services International LTD., using tandem ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, which has previously been described [

20].

Population pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using a non-linear mixed effects approach through the NONMEM

® modelling software (version 7.5.1, Dublin, Ireland) [

21] operating with GForTran via Homebrew (version 13.2.0). Weight was added

a priori with an allometric exponent of 0.75 for clearance parameters and 1 for compartment volumes, as previously described [

22]. Inter-individual variability was modelled assuming log-normally distributed parameters. Periods during which time participants were receiving renal replacement therapy were excluded from the analysis. 1- 2- and 3- compartment models were tested, followed by covariate analysis and addition of inter-occasion variability.

Models were evaluated and selected using a combination of biological plausibility, numerical and visualisation methods. Minimisation of the NONMEM objective function (OFV) required nested models with one additional parameter to show a minimum reduction of 3.84 for a significant improvement in model fit for p<0.05 level. Diagnostic plots were produced using R version 4.2.3 with packages xpose4[

23] and Perl-speaks NONMEM (version 5.3.1)[

24]. Simulations of 10,000 patients receiving intravenous clarithromycin at the World Health Organisation[

25] and Infectious Diseases Society of America[

26] recommended dose of 500 mg 12-hourly were performed based on the final pharmacokinetic model and using estimated protein binding of 80% to demonstrate predicted target attainment [

11]. The R code for simulations is available in the Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Supplementary Code S1: Simulation code.r

Author Contributions

D.O.L., K.K., E.H.B., C.I.S.B., I.O., B.J.P., A.J., A.R., M.S. and J.F.S. were involved in the conceptualisation and methodology of the clinical elements of the study. All authors contributed to the design of the pharmacokinetic analysis. R.V.S., D.O.L. and J.F.S. undertook the formal statistical analysis and pharmacokinetic modelling. All authors: R.V.S., D.O.L., K.K., E.H.B., C.I.S.B., I.O., H.C.B., B.J.P., A.J., A.R., M.S. and J.F.S. have reviewed the results and contributed to the authorship of the study manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (UKCRN ID 18318). C.I.S.B. received salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR ACF-2016-18-016) and from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration under grant agreement No. 261060 (Global Research in Paediatrics—GRiP Network of Excellence) as a Clinical Research Fellow. J.F.S. and C.I.S.B. were supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust and University College London; the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. J.F.S. was supported by a UK Medical Research Council fellowship (MR/M008665/1). K.K. received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement No. 608765 and from Estonian Research Council grant agreement PUTJD22. Laboratory work carried out by K.K. was supported by Analytical Services International. R.V.S. received salary support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR ACL-2019-16-001). R.V.S. and D.O.L. were supported by the Wellcome Trust (Institutional Strategic Support Fund-204809/Z/16/Z). No other support was received for this work outside of the authors’ affiliated institutions. The study was sponsored by St. George’s University of London (Joint research office (JRO) reference 14.0195).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was provided by the national research ethics (REC) committee London (REC reference 14/LO/1999).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data is unfortunately unavailable as permission for open publication of pseudoanonymised data was not sought at time of consent of participants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and their families for taking part in this study. We are grateful to the following members of the research team and students at St. George’s, University of London and St. George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for their help in enrolling patients and sample collection: Michael Tumilty, Helen Farrah, Veronica Barnes, Johannes Mellinghoff, Christine Ryan, Joao Macedo, Naomi Hayward, Vana Wardley, Grace Li, and Joanna Ashby

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roberts, J.A.; Lipman, J. Pharmacokinetic issues for antibiotics in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med 2009, 37, 840-851; quiz 859. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Paul, S.K.; Akova, M.; Bassetti, M.; De Waele, J.J.; Dimopoulos, G.; Kaukonen, K.M.; Koulenti, D.; Martin, C.; Montravers, P.; et al. DALI: defining antibiotic levels in intensive care unit patients: are current β-lactam antibiotic doses sufficient for critically ill patients? Clin Infect Dis 2014, 58, 1072-1083. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Hammond, N.E.; Brett, S.J.; Cotta, M.O.; De Waele, J.J.; Devaux, A.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Dulhunty, J.M.; Elkady, H.; Eriksson, L.; et al. Prolonged vs Intermittent Infusions of β-Lactam Antibiotics in Adults With Sepsis or Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2024. [CrossRef]

- Davey, P.G. The pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin and its 14-OH metabolite. J Hosp Infect 1991, 19 Suppl A, 29-37. [CrossRef]

- Traunmüller, F.; Zeitlinger, M.; Zeleny, P.; Müller, M.; Joukhadar, C. Pharmacokinetics of single- and multiple-dose oral clarithromycin in soft tissues determined by microdialysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 3185-3189. [CrossRef]

- Abduljalil, K.; Kinzig, M.; Bulitta, J.; Horkovics-Kovats, S.; Sörgel, F.; Rodamer, M.; Fuhr, U. Modeling the autoinhibition of clarithromycin metabolism during repeated oral administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 2892-2901. [CrossRef]

- Fish, D.N.; Abraham, E. Pharmacokinetics of a clarithromycin suspension administered via nasogastric tube to seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43, 1277-1280. [CrossRef]

- Kays, M.B.; Denys, G.A. In vitro activity and pharmacodynamics of azithromycin and clarithromycin against Streptococcus pneumoniae based on serum and intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics. Clin Ther 2001, 23, 413-424. [CrossRef]

- Novelli, A.; Fallani, S.; Cassetta, M.I.; Arrigucci, S.; Mazzei, T. In vivo pharmacodynamic evaluation of clarithromycin in comparison to erythromycin. J Chemother 2002, 14, 584-590. [CrossRef]

- Tessier, P.R.; Kim, M.K.; Zhou, W.; Xuan, D.; Li, C.; Ye, M.; Nightingale, C.H.; Nicolau, D.P. Pharmacodynamic assessment of clarithromycin in a murine model of pneumococcal pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 1425-1434. [CrossRef]

- Compendium, E.M. Summary of Product Characteristics: Clarithromycin 125 mg/5ml suspension. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/515/smpc (accessed on 4/6/2024).

- Anon, J.B.; Jacobs, M.R.; Poole, M.D.; Ambrose, P.G.; Benninger, M.S.; Hadley, J.A.; Craig, W.A.; Partnership, S.A.A.H. Antimicrobial treatment guidelines for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004, 130, 1-45. [CrossRef]

- Noreddin, A.M.; El-Khatib, W.F.; Aolie, J.; Salem, A.H.; Zhanel, G.G. Pharmacodynamic target attainment potential of azithromycin, clarithromycin, and telithromycin in serum and epithelial lining fluid of community-acquired pneumonia patients with penicillin-susceptible, intermediate, and resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Int J Infect Dis 2009, 13, 483-487. [CrossRef]

- Testing., T.E.C.o.A.S. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 14.0. 2024.

- Waites, K.B.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for human mycoplasmas : approved guideline. CLSI document, 2011, 1 online resource (1 PDF file (viii, 37 pages)).

- Wang, G.; Wu, P.; Tang, R.; Zhang, W. Global prevalence of resistance to macrolides in Mycoplasma pneumoniae: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022, 77, 2353-2363. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Wilson, D.S.; Deaton, R.L.; Mackenthun, A.V.; Eason, C.N.; Cavanaugh, J.H. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin, a new macrolide antimicrobial. J Clin Pharmacol 1993, 33, 719-726. [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, D.O.; Kipper, K.; Baker, E.H.; Barker, C.I.S.; Oldfield, I.; Philips, B.J.; Johnston, A.; Rhodes, A.; Sharland, M.; Standing, J.F. β-Lactam antimicrobial pharmacokinetics and target attainment in critically ill patients aged 1 day to 90 years: the ABDose study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020, 75, 3625-3634. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.V.; Kipper, K.; Baker, E.H.; Barker, C.I.S.; Oldfield, I.; Philips, B.J.; Johnston, A.; Lipman, J.; Rhodes, A.; Basarab, M.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetic Study of Benzylpenicillin in Critically Unwell Adults. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kipper, K.; Barker, C.I.S.; Standing, J.F.; Sharland, M.; Johnston, A. Development of a Novel Multipenicillin Assay and Assessment of the Impact of Analyte Degradation: Lessons for Scavenged Sampling in Antimicrobial Pharmacokinetic Study Design. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62. [CrossRef]

- Beal, S.; Sheine, L.B.; Boeckmann, A.; Bauer, R.J. NONMEM user’s guides (1989–2011). 2011.

- Lonsdale, D.O.; Baker, E.H.; Kipper, K.; Barker, C.; Philips, B.; Rhodes, A.; Sharland, M.; Standing, J.F. Scaling beta-lactam antimicrobial pharmacokinetics from early life to old age. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2019, 85, 316-346. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, E.N.; Karlsson, M.O. Xpose--an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 1999, 58, 51-64. [CrossRef]

- Keizer, R.J.; Karlsson, M.O.; Hooker, A. Modeling and Simulation Workbench for NONMEM: Tutorial on Pirana, PsN, and Xpose. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 2013, 2, e50. [CrossRef]

- WorldHealthOrganisation. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book. 2022.

- Metlay, J.P.; Waterer, G.W.; Long, A.C.; Anzueto, A.; Brozek, J.; Crothers, K.; Cooley, L.A.; Dean, N.C.; Fine, M.J.; Flanders, S.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019, 200, e45-e67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).