Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

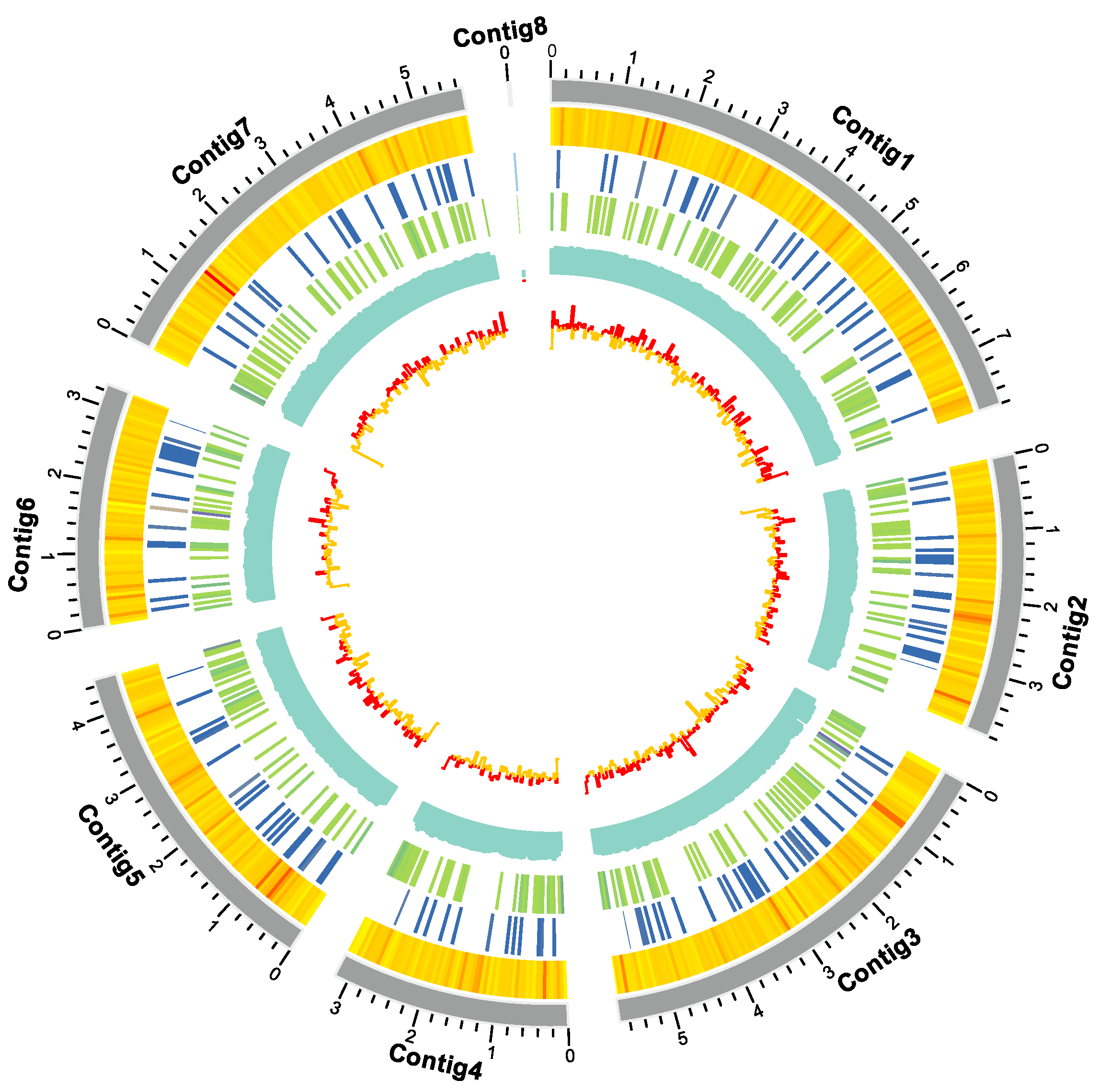

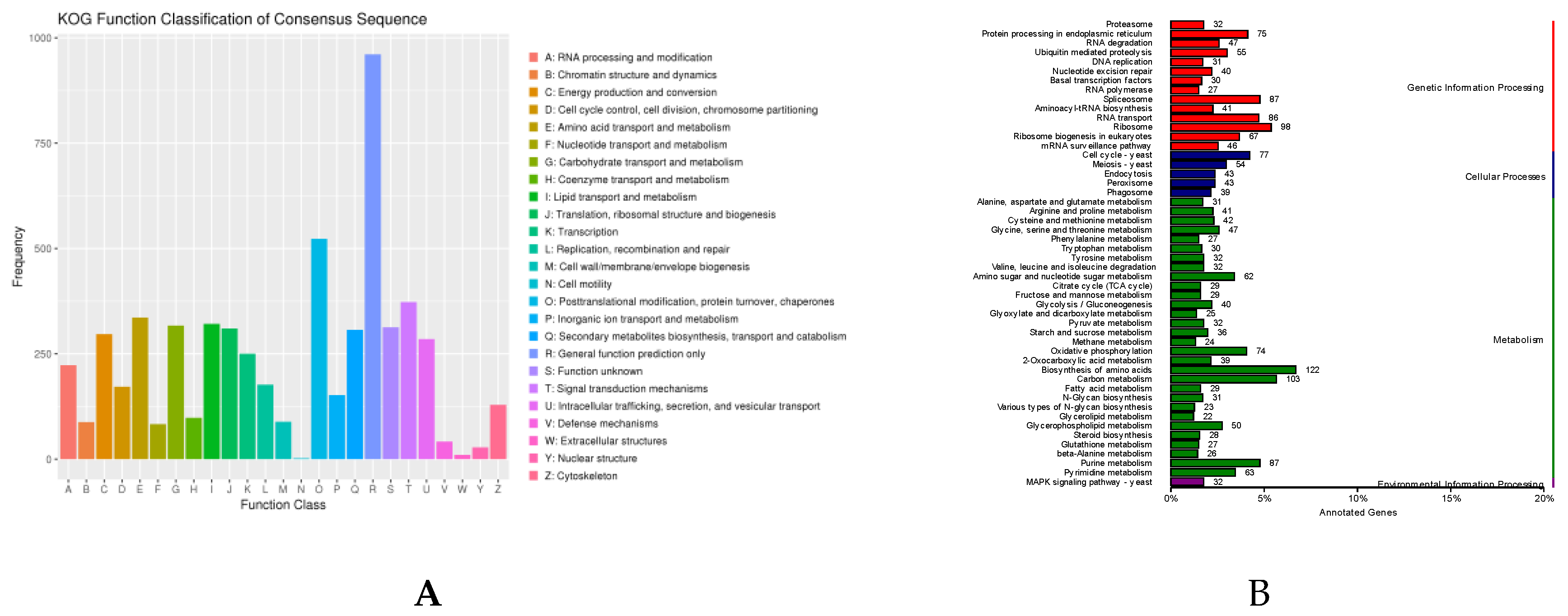

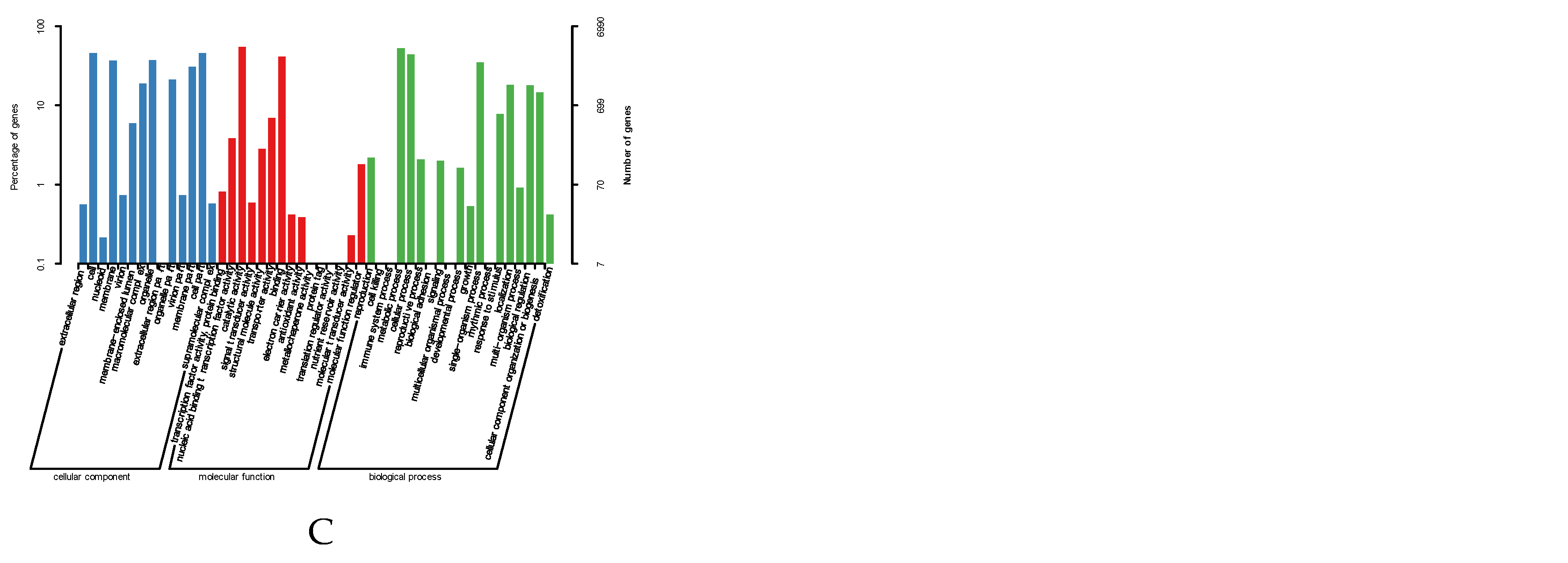

2.1. Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

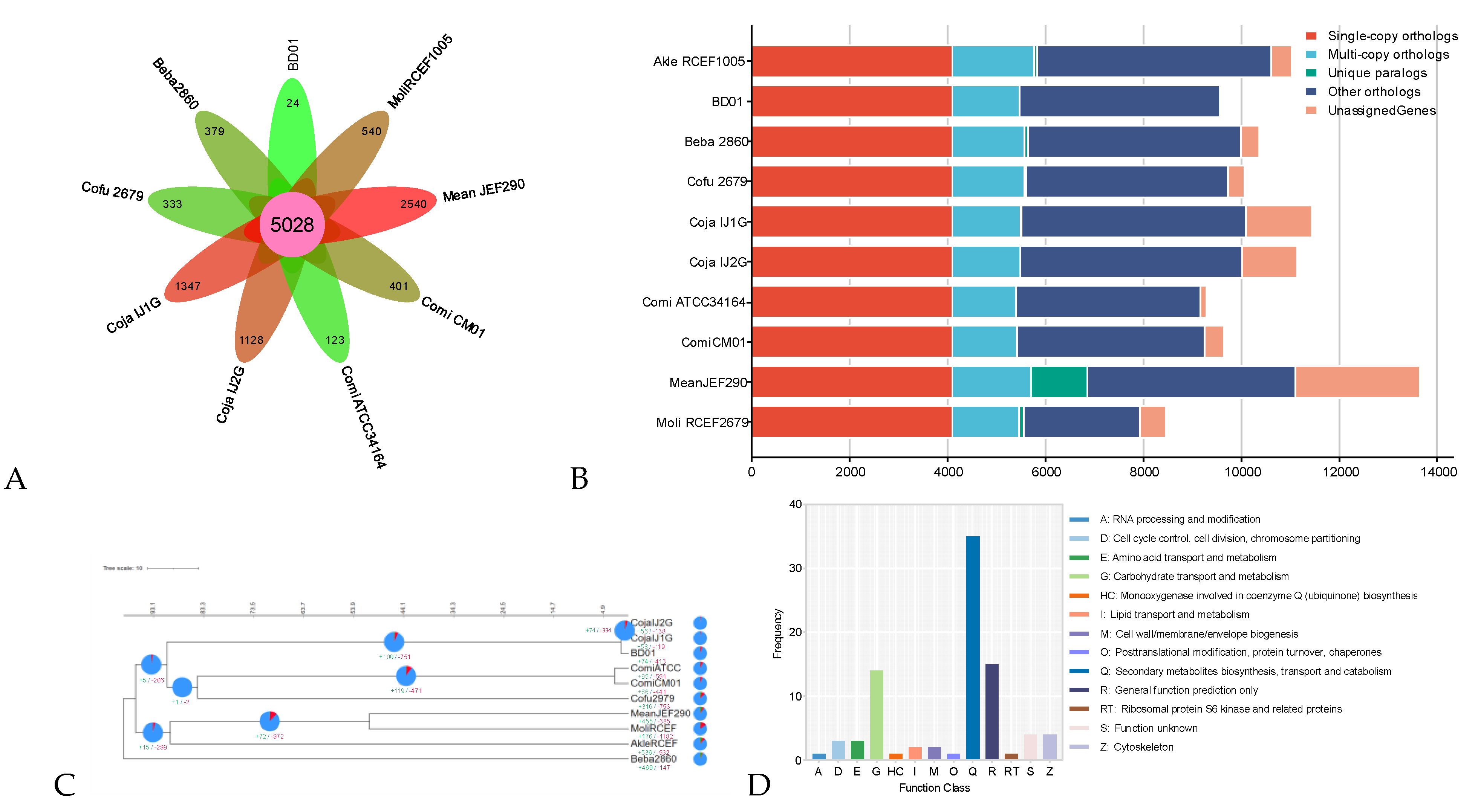

2.2. Comparative Genomic Analysis

2.3. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of GH18 Genes in Cordyceps javanica Bd01

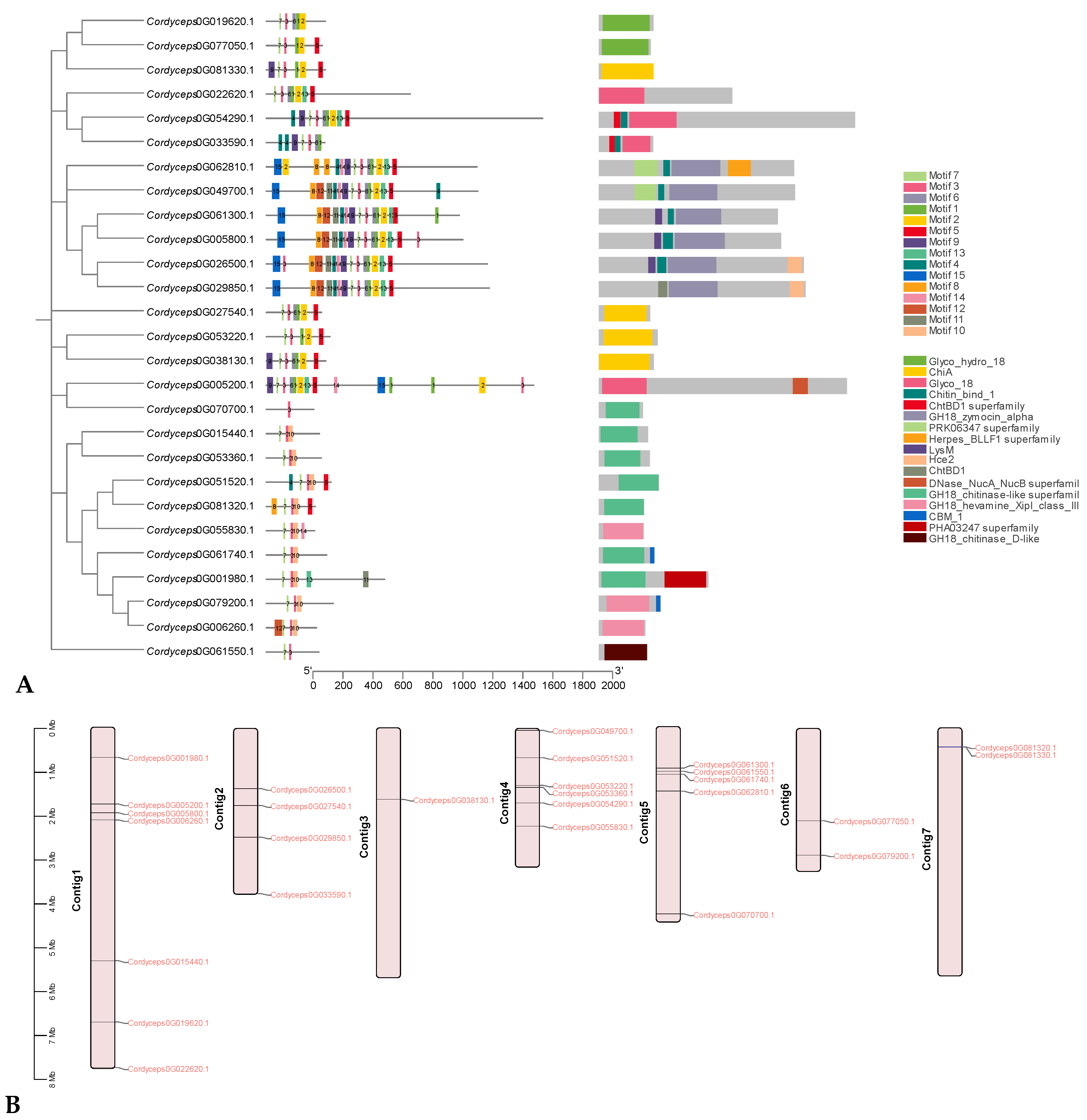

2.4. Conserved Motif and Chromosomal Location of GH18 Genes in Cordyceps javanica Bd01

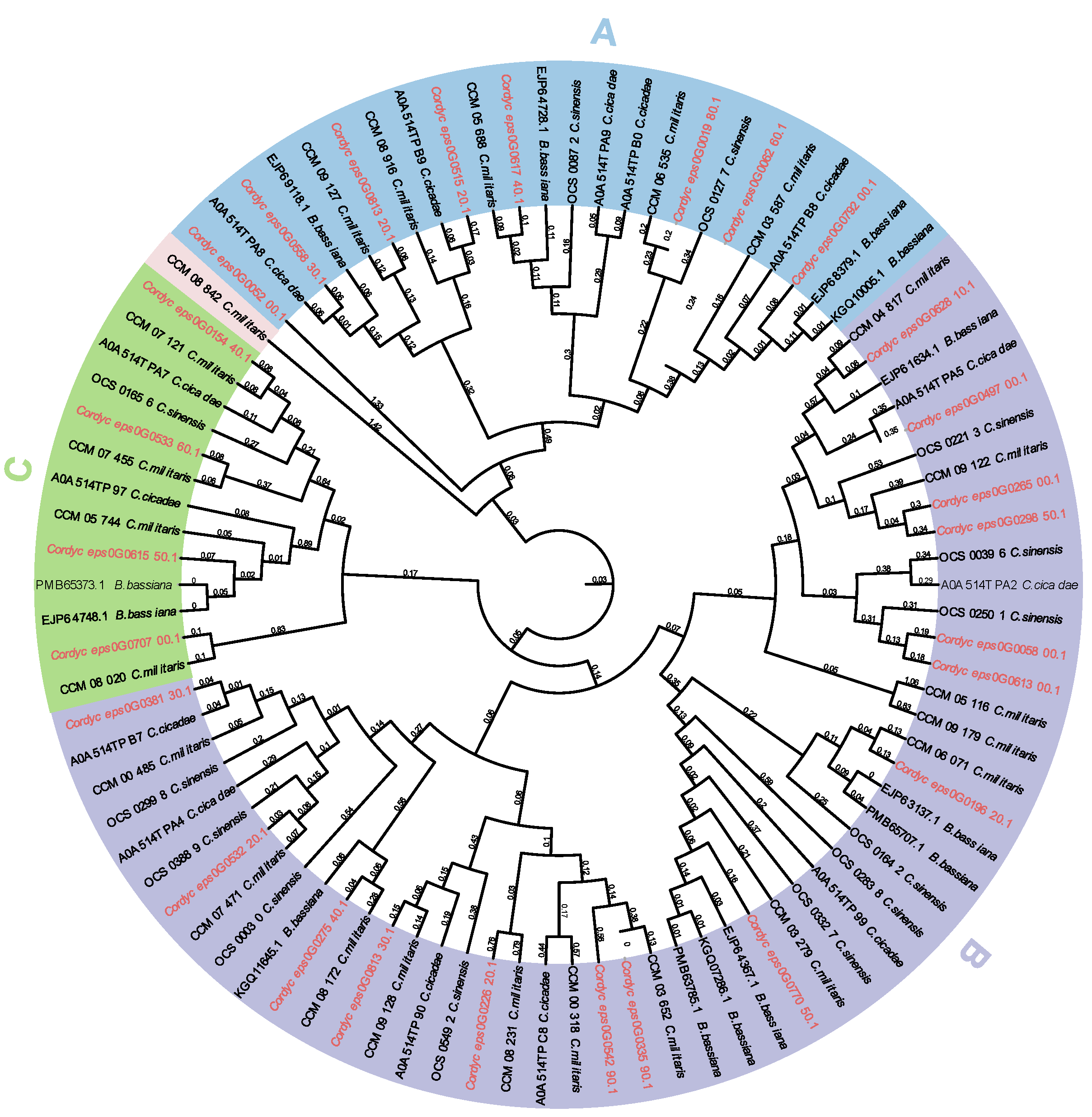

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of GH18 Family Proteins

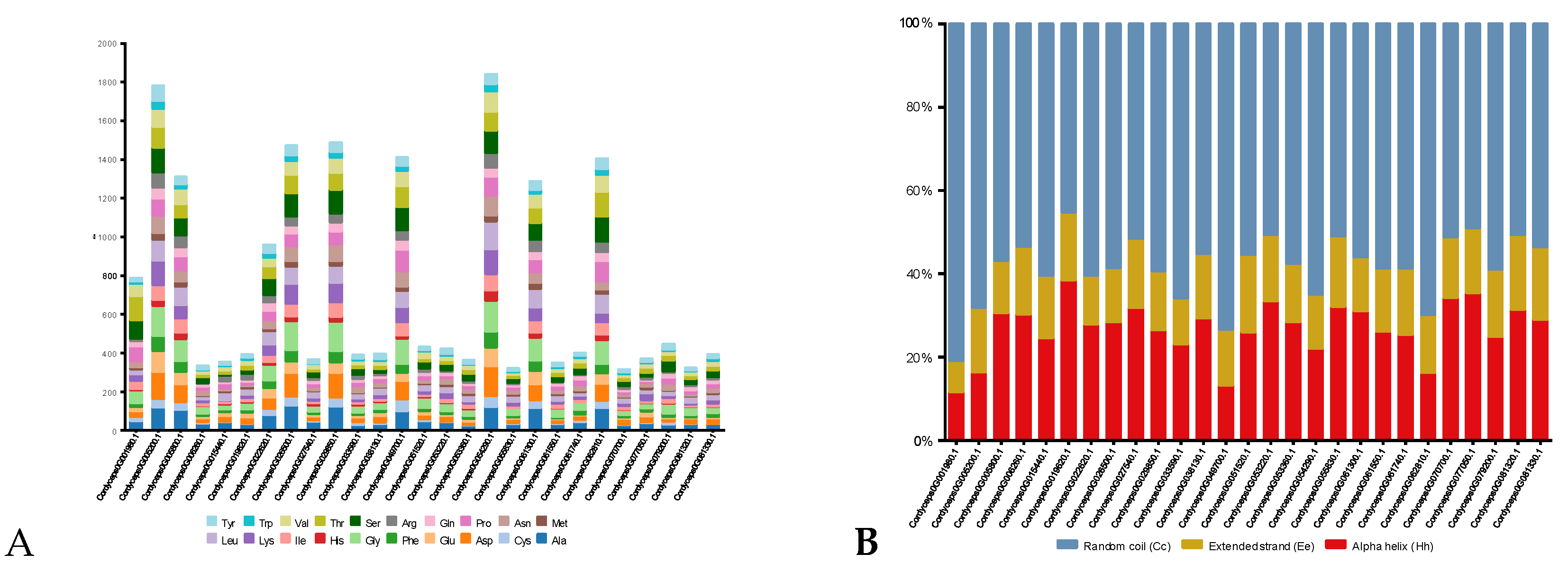

2.6. Characterisation of Physicochemical Properties

2.7. Secondary and Tertiary Structure Analysis

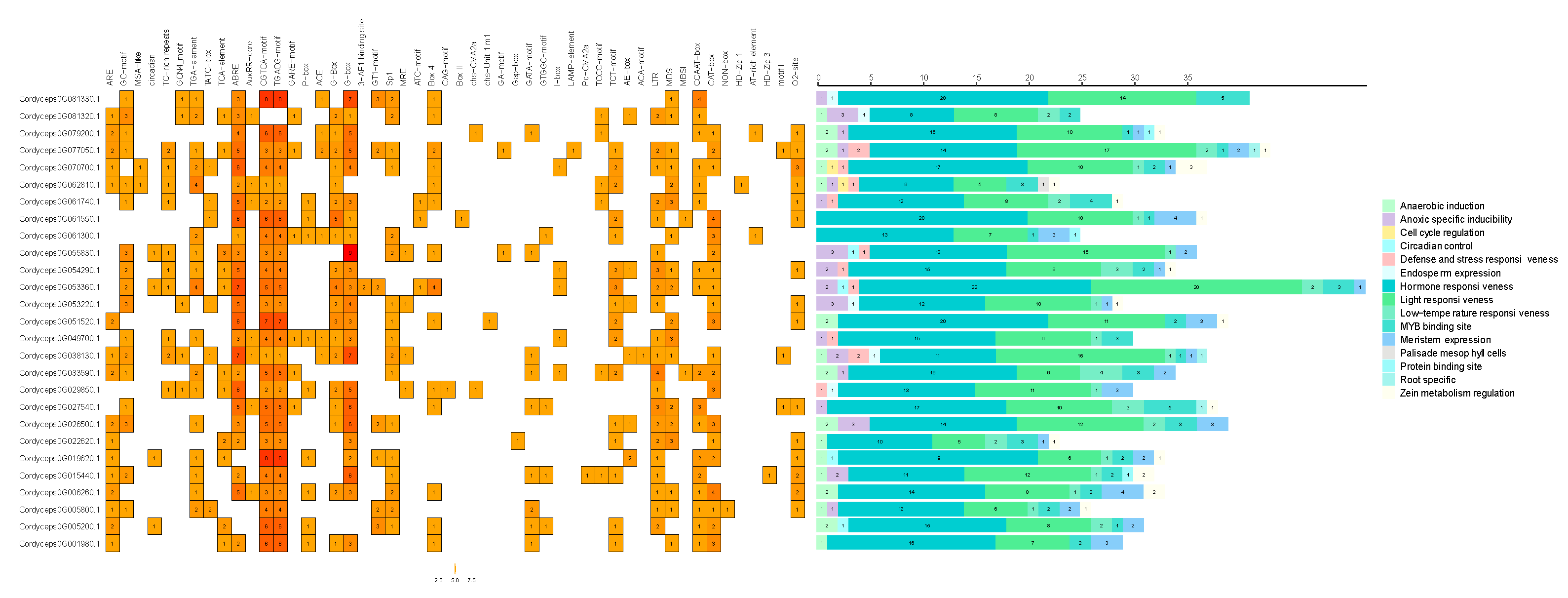

2.8. Analysis of cis-Regulatory Elements in the GH18 Gene Family of Cordyceps javanica Bd01

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Culture of C. javanica Bd01

4.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

4.3. Genome Assembly and Annotation

4.4. Orthologous and Phylogenomic Analysis

4.5. Identification and Characterization of GH18 Gene Family in C. javanica Bd01

4.6. Conserved domain, Conserved Motif Analyses, and Chromosomal Location

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luangsa-Ard, J.J.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Manoch, L.; Samson, R.A. On the Relationships of Paecilomyces Sect. Isarioidea Species1. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallou, A.; Serna-Domínguez, M.G.; Berlanga-Padilla, A.M.; Ayala-Zermeño, M.A.; Mellín-Rosas, M.A.; Montesinos-Matías, R.; Arredondo-Bernal, H.C. Species Clarification of Isaria Isolates Used as Biocontrol Agents against Diaphorina Citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) in Mexico. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Han, J.H.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, S.Y. Effects of Culture Conditions on Conidial Production of the Sweet Potato Whitefly Pathogenic Fungus Isaria Javanica. Mycoscience 2016, 57, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.R.; Lin, Y.; Lv, B.K. Evaluation of Isaria javanica WH-EP-1 for the control of Bemisiaargentifolii biotype B. Compendium of Research on Agricultural Improvement in Hualien District 2019, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, W.A.; Assaf, L.H.; Abdullah, S.K. Occurrence of Entomopathogenic and Other Opportunistic Fungi in Soil Collected from Insect Hibernation Sites and Evaluation of Their Entomopathogenic Potential. Bull. Iraq Nat. Hist. Mus. (P-ISSN: 1017-8678 E-ISSN: 2311-9799) 2012, 12, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Min, C. Wettable Powder Development of Isaria Javanica for Control of the Lesser Green Leafhopper, Empoasca Vitis. J. Biol. Control 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.E.; Kim, J.C.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, M.R.; Kim, S.; Li, D.; Baek, S.; Han, J.H.; Kim, J.J.; Koo, K.B.; et al. Solid Cultures of Thrips-Pathogenic Fungi Isaria Javanica Strains for Enhanced Conidial Productivity and Thermotolerance. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2018, 21, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, S.; Yin, F.; Cai, S.; Zhong, G.; Ren, S. Diversity and Virulence of Soil-Dwelling Fungi Isaria Spp. and Paecilomyces Spp. against Solenopsis Invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Biocontrol Science and Technology 2011, 21, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.S.; Svedese, V.M.; Portela, A.P. a. S.; Albuquerque, A.C.; Luna-Alves Lima, E.A. Virulência e Aspectos Biológicos de Isaria Javanica (Frieder & Bally) Samson & Hywell-Jones Sobre Coptotermes Gestroi (Wasmann) (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae). Arq, Inst, Biol, (Online), 2011, 565–572.

- Cabanillas, H.E.; Jones, W.A. Effects of Temperature and Culture Media on Vegetative Growth of an Entomopathogenic Fungus Isaria Sp. (Hypocreales: Clavicipitaceae) Naturally Affecting the Whitefly, Bemisia Tabaci in Texas. Mycopathologia 2009, 167, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, M.; Takatsuka, J. Isaria Javanica (Anamorphic Cordycipitaceae) Isolated from Gypsy Moth Larvae, Lymantria Dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae), in Japan. Appl. Entomol. Zool. - APPL ENTOMOL ZOOL 2010, 45, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Keyhani, N.O. Action on the Surface: Entomopathogenic Fungi versus the Insect Cuticle. Insects 2013, 4, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Gao, T.; Huang, Y.; Ren, S.; Keyhani, N.O. The Ifchit1 Chitinase Gene Acts as a Critical Virulence Factor in the Insect Pathogenic Fungus Isaria Fumosorosea. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5491–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Keyhani, N.O. Molecular Genetics of Beauveria Bassiana Infection of Insects. Adv Genet 2016, 94, 165–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero-Jiménez, C.A.; Wiegers, H.; Zwaan, B.J.; Koenraadt, C.J.M.; van Kan, J.A.L. Genes Involved in Virulence of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria Bassiana. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 133, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S. Insect Pathogenic Fungi: Genomics, Molecular Interactions, and Genetic Improvements. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elad, Y.; Chet, I.; Henis, Y. Degradation of Plant Pathogenic Fungi by Trichoderma Harzianum. Can. J. Microbiol. 1982, 28, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, J.; Chet, I. The Role of Recognition in the Induction of Specific Chitinases during Mycoparasitism by Trichoderma Harzianum. Microbiology 1995, 141, 2823–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.J. Fungal Cell Wall Chitinases and Glucanases. Microbiology 2004, 150, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonfa, T.G.; Negessa, A.K.; Bulto, A.O. Isolation, Screening, and Identification of Chitinase-Producing Bacterial Strains from Riverbank Soils at Ambo, Western Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrissat, B.; Bairoch, A. New Families in the Classification of Glycosyl Hydrolases Based on Amino Acid Sequence Similarities. Biochem J 1993, 293 ( Pt 3) Pt 3, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawase, T.; Saito, A.; Sato, T.; Kanai, R.; Fujii, T.; Nikaidou, N.; Miyashita, K.; Watanabe, T. Distribution and Phylogenetic Analysis of Family 19 Chitinases in Actinobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidl, V. Chitinases of Filamentous Fungi: A Large Group of Diverse Proteins with Multiple Physiological Functions. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2008, 22, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, L.; Zach, S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V. Fungal Chitinases: Diversity, Mechanistic Properties and Biotechnological Potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrangi, S.; Faramarzi, M.A. From Bacteria to Human: A Journey into the World of Chitinases. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1786–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stals, I.; Samyn, B.; Sergeant, K.; White, T.; Hoorelbeke, K.; Coorevits, A.; Devreese, B.; Claeyssens, M.; Piens, K. Identification of a Gene Coding for a Deglycosylating Enzyme in Hypocrea Jecorina. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2010, 303, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelepis, G.; Hosomi, A.; Hossain, T.J.; Hirayama, H.; Dubey, M.; Jensen, D.F.; Suzuki, T.; Karlsson, M. Endo-β-N-Acetylglucosamidases (ENGases) in the Fungus Trichoderma Atroviride: Possible Involvement of the Filamentous Fungi-Specific Cytosolic ENGase in the ERAD Process. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 449, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldo, J.T.; Junges, A.; do Amaral, K.B.; Staats, C.C.; Vainstein, M.H.; Schrank, A. Endochitinase CHI2 of the Biocontrol Fungus Metarhizium Anisopliae Affects Its Virulence toward the Cotton Stainer Bug Dysdercus Peruvianus. Curr. Genet. 2009, 55, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, C.C.; Kmetzsch, L.; Lubeck, I.; Junges, A.; Vainstein, M.H.; Schrank, A. Metarhizium Anisopliae Chitinase CHIT30 Is Involved in Heat-Shock Stress and Contributes to Virulence against Dysdercus Peruvianus. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Leng, B.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, K.; Ma, J.; Fan, Y.; Feng, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, Y. Cloning of Beauveria Bassiana Chitinase Gene Bbchit1 and Its Application to Improve Fungal Strain Virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Wang, Z.; Meng, X.; Xie, L.; Huang, B. Cloning and Expression Analysis of the Chitinase Gene Ifu-Chit2 from Isaria Fumosorosea. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2015, 38, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Gao, T.; Huang, Y.; Ren, S.; Keyhani, N.O. The Ifchit1 Chitinase Gene Acts as a Critical Virulence Factor in the Insect Pathogenic Fungus Isaria Fumosorosea. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5491–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gao, T.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z. Effect of Ifchit1 Gene of Isaria Fumosorosea on Mortality, Oviposition and Oxidase Activities of Bemisia Tabaci. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hussain, M.; Wu, M.; Shi, C.; Li, S.; Ji, Y.; Hussain, S.; Qin, D.; Xiao, C.; Wu, G. Whole-Genome Sequencing of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Fusarium Solani KMZW-1 and Its Efficacy against Bactrocera Dorsalis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 11593–11612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Luo, F.; Cen, K.; Xiao, G.; Yin, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Zhan, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C. Omics Data Reveal the Unusual Asexual-Fruiting Nature and Secondary Metabolic Potentials of the Medicinal Fungus Cordyceps Cicadae. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitreva, M.; Jasmer, D.P.; Zarlenga, D.S.; Wang, Z.; Abubucker, S.; Martin, J.; Taylor, C.M.; Yin, Y.; Fulton, L.; Minx, P.; et al. The Draft Genome of the Parasitic Nematode Trichinella Spiralis. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V. Self versus Non-Self: Fungal Cell Wall Degradation in Trichoderma. Microbiology 2012, 158, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpure, A.; Choudhary, B.; Gupta, R.K. Chitinases: In Agriculture and Human Healthcare. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014, 34, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berini, F.; Katz, C.; Gruzdev, N.; Casartelli, M.; Tettamanti, G.; Marinelli, F. Microbial and Viral Chitinases: Attractive Biopesticides for Integrated Pest Management. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 818–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, L.; Zach, S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V. Fungal Chitinases: Diversity, Mechanistic Properties and Biotechnological Potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldo, J.T.; Junges, A.; do Amaral, K.B.; Staats, C.C.; Vainstein, M.H.; Schrank, A. Endochitinase CHI2 of the Biocontrol Fungus Metarhizium Anisopliae Affects Its Virulence toward the Cotton Stainer Bug Dysdercus Peruvianus. Curr Genet 2009, 55, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsolio, C.; Benhamou, N.; Haran, S.; Cortés, C.; Gutiérrez, A.; Chet, I.; Herrera-Estrella, A. Role of the Trichoderma Harzianum Endochitinase Gene, Ech42, in Mycoparasitism. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999, 65, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.L.; Donzelli, B.; Scala, F.; Mach, R.; Harman, G.E.; Kubicek, C.P.; Del Sorbo, G.; Lorito, M. Disruption of the Ech42 (Endochitinase-Encoding) Gene Affects Biocontrol Activity in Trichoderma Harzianum P1. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1999, 12, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S.; Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Matarese, F.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Kubicek, C.P.; Seidl-Seiboth, V. Analysis of Subgroup C of Fungal Chitinases Containing Chitin-Binding and LysM Modules in the Mycoparasite Trichoderma Atroviride. Glycobiology 2011, 21, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, S.; Kubicek, C.P.; Seidl-Seiboth, V. Differential Regulation of Orthologous Chitinase Genes in Mycoparasitic Trichoderma Species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 7217–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Xiao, G.; Zheng, P.; Cen, K.; Zhan, S.; Wang, C. Divergent and Convergent Evolution of Fungal Pathogenicity. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 1374–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, V.; Huemer, B.; Seiboth, B.; Kubicek, C.P. A Complete Survey of Trichoderma Chitinases Reveals Three Distinct Subgroups of Family 18 Chitinases. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 5923–5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junges, Â.; Boldo, J.T.; Souza, B.K.; Guedes, R.L.M.; Sbaraini, N.; Kmetzsch, L.; Thompson, C.E.; Staats, C.C.; de Almeida, L.G.P.; de Vasconcelos, A.T.R.; et al. Genomic Analyses and Transcriptional Profiles of the Glycoside Hydrolase Family 18 Genes of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium Anisopliae. PLOS One 2014, 9, e107864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havukkala, I.; Mitamura, C.; Hara, S.; Hirayae, K.; Nishizawa, Y.; Hibi, T. Induction and Purification of Beauveria Bassiana Chitinolytic Enzymes. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 1993, 61, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Leng, B.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, K.; Ma, J.; Fan, Y.; Feng, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, Y. Cloning of Beauveria Bassiana Chitinase Gene Bbchit1 and Its Application to Improve Fungal Strain Virulence. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requião, R.D.; Fernandes, L.; de Souza, H.J.A.; Rossetto, S.; Domitrovic, T.; Palhano, F.L. Protein Charge Distribution in Proteomes and Its Impact on Translation. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59259-890-8. [Google Scholar]

- Idicula-Thomas, S.; Balaji, P.V. Understanding the Relationship between the Primary Structure of Proteins and Their Amyloidogenic Propensity: Clues from Inclusion Body Formation. Protein eng. des. sel.: PEDS 2005, 18, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohel, V.; Naseby, D.C. Thermalstabilization of Chitinolytic Enzymes of Pantoea Dispersa. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007, 35, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouripur, G.C.; Kaliwal, R.B.; Kaliwal, B.B. In Silico Characterization of Beta-Galactosidase Using Computational Tools. J. Bioinform. Seq. Anal. 2016, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minetoki, T.; Tsuboi, H.; Koda, A. Development of High Expression System with the Improved Promoter Using the Cis-Acting Element in Aspergillus Species.; 2003. 1 November.

- Sakekar, A.A.; Gaikwad, S.R.; Punekar, N.S. Protein Expression and Secretion by Filamentous Fungi. J. Biosci. 2021, 46, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Choi, J.L.; Costa, M.A.; An, G. Identification of G-Box Sequence as an Essential Element for Methyl Jasmonate Response of Potato Proteinase Inhibitor II Promoter. Plant Physiol. 1992, 99, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkens, A.E.; Schindler, U.; Cashmore, A.R. The G-Box: A Ubiquitous Regulatory DNA Element in Plants Bound by the GBF Family of bZIP Proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995, 20, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.J.; et al. Identification, culture, and pathogenicity of an entomopathogenic fungus from the larvae of Xylotrechus quadripes. Science of Western Forestry 2022, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallou, A.; Serna-Domínguez, M.G.; Berlanga-Padilla, A.M.; Ayala-Zermeño, M.A.; Mellín-Rosas, M.A.; Montesinos-Matías, R.; Arredondo-Bernal, H.C. Species Clarification of Isaria Isolates Used as Biocontrol Agents against Diaphorina Citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) in Mexico. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu-chu, H. Integrated Nr Database in Protein Annotation System and Its Localization. Comput. Eng. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann, B.; Bairoch, A.; Apweiler, R.; Blatter, M.-C.; Estreicher, A.; Gasteiger, E.; Martin, M.J.; Michoud, K.; O’Donovan, C.; Phan, I.; et al. The SWISS-PROT Protein Knowledgebase and Its Supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG Resource for Deciphering the Genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatusov, R.L.; Galperin, M.Y.; Natale, D.A.; Koonin, E.V. The COG Database: A Tool for Genome-Scale Analysis of Protein Functions and Evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conesa, A.; Götz, S.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Talón, M.; Robles, M. Blast2GO: A Universal Tool for Annotation, Visualization and Analysis in Functional Genomics Research. Bioinform. (Oxf. Engl.) 2005, 21, 3674–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Profile Hidden Markov Models. Bioinform. (Oxf. Engl.) 1998, 14, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.D.; Coggill, P.; Eberhardt, R.Y.; Eddy, S.R.; Mistry, J.; Mitchell, A.L.; Potter, S.C.; Punta, M.; Qureshi, M.; Sangrador-Vegas, A.; et al. The Pfam Protein Families Database: Towards a More Sustainable Future. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, D279–D285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic Orthology Inference for Comparative Genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Muscle5: High-Accuracy Alignment Ensembles Enable Unbiased Assessments of Sequence Homology and Phylogeny. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castresana, J. Selection of Conserved Blocks from Multiple Alignments for Their Use in Phylogenetic Analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.; Andreeva, A.; Florentino, L.C.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Hobbs, E.; Pinto, B.L.; Orr, A.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Ponamareva, I.; et al. InterPro: The Protein Sequence Classification Resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, D444–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent Updates, New Developments and Status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The Conserved Domain Database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D265–D268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J. M., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2005; ISBN 978-1-58829-343-5. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.-J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein Localization Predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The Conserved Domain Database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Andreeva, A.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Llinares-López, F.; Meng-Papaxanthos, L.; et al. The Pfam Protein Families Database: Embracing AI/ML. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 53, D523–D534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Cordyceps javanica Bd01 |

|---|---|

| Coverage (fold) | 229.59X |

| No. of all sequence | 698,137 |

| Bases in all sequence (bp) | 7,808,156,751 |

| Largest length (bp) | 193,316 |

| N50 Len (bp) | 18,161 |

| N90 Len (bp) | 4,902 |

| G+C content | 53.18 |

| No. of all contigs | 8 |

| Contig Length (bp) | 34,008,118 |

| No. of large contigs (> 1000 bp) | 8 |

| Bases in large contigs (bp) | 34,008,118 |

| Contig N50 (bp) | 5,679,179 |

| Contig N90 (bp) | 3,285,737 |

| Gene num | 9,590 |

| Gene total length (bp) | 17,091,976 |

| Gene average length (bp) | 1,782.27 |

| ExonLen (bp) | 15,026,841 |

| AveExonLen (bp) | 568.12 |

| ExonNum | 26,450 |

| AveExonNum | 2.76 |

| rRNA | 43 |

| tRNA | 131 |

| Gene name | Number of amino acids | Molecular weight (kDa) | Total number of negatively charged residues (Asp+Glu) | Total number of positively charged residues (Arg+Lys) | pI | Instability index | Aliphatic Index | GRAVY | subcellular localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cordyceps0G001980.1 | 787 | 81.41 | 49 | 47 | 7.92 | 39.67 | 63.52 | -0.206 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G005200.1 | 1782 | 19.91 | 249 | 206 | 5.33 | 40.35 | 62.25 | -0.604 | nucl |

| Cordyceps0G005800.1 | 1310 | 14.35 | 157 | 126 | 5.55 | 44.52 | 76.86 | -0.268 | plas |

| Cordyceps0G006260.1 | 333 | 35.07 | 29 | 17 | 4.52 | 33.17 | 68.68 | -0.186 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G015440.1 | 353 | 38.95 | 50 | 31 | 4.73 | 43.44 | 89.41 | -0.194 | mito |

| Cordyceps0G019620.1 | 392 | 43.82 | 57 | 43 | 5.03 | 48.63 | 78.65 | -0.329 | mito |

| Cordyceps0G022620.1 | 958 | 10.54 | 107 | 92 | 5.58 | 45.09 | 64.73 | -0.421 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G026500.1 | 1473 | 15.9 | 180 | 148 | 5.39 | 28.36 | 63.65 | -0.443 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G027540.1 | 367 | 39.06 | 33 | 28 | 6.11 | 46.74 | 83.32 | -0.126 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G029850.1 | 1486 | 16.06 | 182 | 143 | 5.2 | 30.46 | 67.27 | -0.412 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G033590.1 | 389 | 42.6 | 36 | 32 | 6.2 | 33.37 | 64.73 | -0.456 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G038130.1 | 395 | 44.06 | 54 | 33 | 4.72 | 37.83 | 67.72 | -0.508 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G049700.1 | 1409 | 15.1 | 138 | 125 | 5.83 | 43.01 | 65.44 | -0.376 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G051520.1 | 430 | 45.22 | 45 | 36 | 5.44 | 30.03 | 73.35 | -0.231 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G053220.1 | 423 | 46.19 | 39 | 38 | 6.53 | 26.44 | 73.22 | -0.319 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G053360.1 | 365 | 39.84 | 31 | 25 | 5.74 | 38.65 | 80.47 | -0.147 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G054290.1 | 1842 | 20.43 | 251 | 204 | 5.63 | 36.42 | 72.49 | -0.461 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G055830.1 | 320 | 34.08 | 29 | 30 | 7.53 | 24.01 | 76.34 | -0.218 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G061300.1 | 1286 | 14.03 | 150 | 127 | 5.68 | 43.02 | 73.79 | -0.265 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G061550.1 | 348 | 36.71 | 24 | 23 | 6.12 | 31.95 | 84.45 | 0.009 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G061740.1 | 401 | 42.25 | 28 | 24 | 4.94 | 36.66 | 59.48 | -0.183 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G062810.1 | 1404 | 15.14 | 140 | 104 | 5.3 | 41.7 | 70.89 | -0.236 | mito |

| Cordyceps0G070700.1 | 315 | 34.54 | 35 | 32 | 5.69 | 28.53 | 78.44 | -0.320 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G077050.1 | 372 | 41.41 | 52 | 47 | 5.63 | 33.53 | 64.87 | -0.483 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G079200.1 | 445 | 46.94 | 24 | 23 | 6.29 | 41.27 | 61.21 | -0.290 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G081320.1 | 324 | 33.98 | 31 | 19 | 4.4 | 37.51 | 80.46 | -0.108 | extr |

| Cordyceps0G081330.1 | 392 | 43.13 | 34 | 31 | 5.5 | 35.96 | 73.67 | -0.246 | extr |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).