Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Notes and References

- Arrhenius, S. “On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground” Phil. Mag. J. Sci. 1896, 41, 237, For a more current perspective, see Hatfield, J. L.; Prueger, J. H.”Temperature extremes: Effect on plant growth and development” Weather and Climate Extremes, 2015, 10, 4. 10.1015/wace.2015.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. E. P.; Draper, N. R. Empirical Model Building and Response Surfaces; John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, 1987. “Essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful (p 424)…. the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful (p74)”.

- Revelle, R,; Suess,H, E, “Carbon Dioxide Exchange Between Atmosphere and Ocean and the Question of an Increase of Atmospheric CO2 during the Past Decades” Tellus IX 1957. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G. J.; Harrison, P. A. “The Effects of Climate Variability and Change on Grape Suitability in Europe” J. Wine Res. 1992, 3, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, H. R. “Climate Change and Viticulture: A European perspective on climatology, carbon dioxide and UV-B effects” Aust. J. Grape and Wine Res. 2000, 6, 2, and 18 Schultz, H. R. “Climate Change and Viticulture: Research Needs for Facing the Future” J. Wine Research, 19 2010, 21, 113 (DOI:10.1080/09571264.2919.530093). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.E.; Bradley, R.S; Hughes, M. K. “Global-scale temperature patterns and climate forcing over the past six centuries”. Nature 1998, 392, 779, and also see Mann, M.E.; Bradley,R.S; 23 Hughes, M. K. “Northern Hemisphere Temperatures During the Past Millennium: Inferences, 24 Uncertainties, and Limitations” Geophys. Res. Lett. 1999, 26, 759 (DOI: 10.1029/1999GL900070) as well as 25 Mann, M. E. “Beyond the hockey stick: Climate lessons from the Common Era” Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S. 26 2021, 118 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2112797118) with the time line updated to reflect current changes to the longer 27 term of “…at least the past two millennia and more tentatively, the past 20,000 y(ears)…”. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuine, I.; Yiou, P.; Viovy, N.; Seguin, B.; Daux, V.; Ladurie, E.L.R. ‘Grape ripening as a past climate indicator”. Nature 2004, 432, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M. A.; Diffenbaugh, N. S.; Jones, G. V.; Pal, J. S.; Giorgi, F. “Extreme Heat Reduces and Shifts United States Premium Wine Production in the 21st Century” Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S., 2006, 103, 11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Orduña, R. M. ”Climate change associated effects on grape and wine quality and production” Food Res. Internat. 2010, 43, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Lüscher, J.; Morales, F.; Sánchez-Diaz, M.; Delrot, S.; Aguirreolea, J.; Gomès, E. ; Pascual. I. “Climate change conditions (elevated CO2 and temperatures) and UV-B radiation affect grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Tempranillo) leaf carbon assimilation, altering fruit ripening rates” Plant Sci. 2015, 236, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Some efforts have been made in current wine growing regions in an attempt to estimate what might be done to ameliorate the effects of climate change. For example: (a) A variety of grapes in vineyards across Western Australia were examined for titratable acidity and anthocyanins over a two year period at the end of the decade ending in 2010. (i) Barnuud, N.N.; Zerihun, A.; Gibberd, M.; Bates, B. “Berry composition and climate: responses and empirical models” Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014. 58, 1207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-013-0715-2) and (ii) Barnuud, N.N.; Zerihun, A.; Mpelasoka, F.; Gibberd, M.; Bates, B. “Responses of grape berry anthocyanin and titratable acidity to the projected climate change across the Western Australian wine regions” Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 1279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-013-0724-1. The authors suggest more work might be needed since it’s not clear what should be done as the climate changes. (b) In Central Romania, Costea, M.; Lengyel, E.; Stegărus, D.; Rusan, N.; Tăuşan, I. “Assessment of climatic conditions as driving factors of wine aromatic compounds: a case study from Central Romania” Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 137, 239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007-4-018-2594-2. the belief that climate change will be worthwhile from short term measurements of esters, high (molecular weight) alcohols, volatile fatty acids, aldehydes and terpenes was expressed. (c) Along Lake Neuchatel, Switzerland where, in the decades beginning in 1970 “…the climate in the …vineyards changed from very cool or cool to temperate…” Comte, V.; Schneider, L.; Calanca, P.; Rebetez, M. “Effects of climate change on bioclimaic indices in vineyards along Lake Neuchatel, Switzerland” Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 147, 423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-021-03836-1. and changes in what is grown might be needed. (d) In other wine growing regions in Europe as outlined by Sgubin, G.; Swingedouw, D.; Mignot, J.; Gambetta, G. A.; Bois, B.; Loukos, H.; Noël, T.; Pierl, P.; de Cortázar-Atauri, I.G.; Oliat N.; van Leeuwen, C. “Non-linear loss of suitable wine regions over Europe in response to increasing global warming” Global Change Bio., 2022, 29, 808. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16493) (e) In Argentina it is anticipated that a significant southwestward and higher altitude displacement of winegrowing regions will be needed due to projected warmer climate conditions according to Cabré, F.; Nuñez, M. “Impact of climate change on viticulture in Argentina” Reg. Enverion. Change, 2020, 20, 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01607-8. 2014; 58, 1207. [CrossRef]

- Hannah,L. ; Roehrdanz, P. R.; Ikegami, M.; Shepard, A. V.; Shaw, R,; Tabor, G.; Zhi, L.; Marquet, P. A.; Hijmans, R. J. “Climate change, wine, and conservation” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. 2013, 110, 6907. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Egipto, R.; Aguiar, F.; Marques, P.; Nogales, A.; Madeira, M. “The role of soil temperature in Mediterranean vineyards in a climate change context” Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1145137, and Radolinski, J.; Vermec, M.; Wachter, H.; Birk, S.; Brűggemann, N.; Herndt, M.; Kahmen, A.; Nelson, D. B.; Kűbert, A.; Schaumberger, A.; Stumpp, C. Tisslnk, M. Werner, C.; Bahn, M. “Drought in a warmer, CO2-rich climate restricts grassland water use and soil water mixing” Science, 2025, 387, 290. 10.1126/science.ado0734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Schultz, H.R.; de Cortazar-Atauri, I. G.; Duchêne, E.; Ollat, N.; Pieri, P.; Bois, B.; Goutouly, J. P.; Quenol, H.; Touzard, J. M; Malheiro, A. C. ; Bavaresco, L; Delrot, S. “Why climate change will not dramatically decrease viticultural suitability in main wine-producing areas by 2050” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S. 2013, 110, E3051, and subsequently in van Leeuwen, C,; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Dibernet, M.; Duchêne, E.; Gowdy, M.; Marguerit, E.; Pieri, P.; Parker, A.; de Rességuier, L ;Ollat, N. “An Update on the Impact of Climate Change in Viticulture and Potential Adaptations” Agronomy, 2019, 9, 514. 10.3390/agronomy9090514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheben, A.; Yuan, Y.; Edwards, D. “Advances in genomics for adapting crops to climate change” Curr. Plant Bio. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delrot, S.; Grimplet, J.; Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Schwander, A.; Bert, P.-F.; Bavaraesco, L.; Costa, L. D.; Di Gaspero, G.; Duche, E.; Hausmann, L.; Malnoy, M.; Morgante, M.; Ollat, N.; Pecile, M.; Vezzulli, S. “Genetic and Genomic Approaches for Adaptation of Grapevine to Climate Change”. In: Kole, C. (ed) Genomic Designing of Climate-Smart Fruit Crops 2020 Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Mosedale, J. R.; Abernethy, K.; Smart, R. E.; Wilson, R. J.; Maclean, I.D. “Climate change impacts and adaptive strategies: lessons from the grapevine” Global Change Biology, 2016, 22,3814. 22. [CrossRef]

- Asproudi, A.; Ferrandino, A.; Bonello, F.; Vaudano, E.; Pollon, M.; Petrozziello, M. “Key norisoprenoid compounds in wines from early-harvested grapes in view of climate change” Food Chem. 2018, 268, 143. 268. [CrossRef]

- The following articles appeared sequentially in the New York times during 2019: (a) Asimov, E. The following articles appeared sequentially in the New York times during 2019: (a) Asimov, E. “Climate change will inevitably transform the way the world produces goods”, 14 October 2019 (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/14/dining/drinks/climate-change-wine.html); (b) Asimov, E. “In Oregon Wine Country, One Farmer’s Battle to Save the Soil”, 17 October 2019 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/17/dining/drinks/climate-change-regenerative-agriculture-wine.html); (c) Asimov, E. “Freshness in a Changed Climate:High Altitudes, Old Grapes” 24 October 2019 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/24/dining/familia-torres-wine-climate-change.html); (d) Asimov, E. “In Napa Valley, Winemakers Fight Climate Change on All Fronts” 31 October 2019 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/dining/drinks/napa-valley-wine-climate-change.html.

- ”The Wine Industry’s Climate Action Network” found at https://portoprotocol.com (last accessed January 2025).

- Fried, J S. ; Torn, M. S.; Mills, E. “The Impact of Climate Change on Wildfire Severity: A Regional Forecast for Northern California” Climate Change 2004, 64, 169. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B. j.; Mason J., A.; Todd, J. B.; Bosch, E. M.; Wotton, B. M.; Amiro, B. D.; Flannigan, M. D.; Hirsh, K. G.; Logan, K. A. ; Martell. D. L.; Skinner, W. R. “Large forest fires in Canada 1959-1997” J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, M. D.; van Wagner, C. E. “Climate change and wildfire in Canada” Can. J. For. Res. 1991, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The report can be found at https://www.awri.com.au › wp-content › uploads › 2003_AWRI_Annual_Report.pdf (last accessed January 2025).

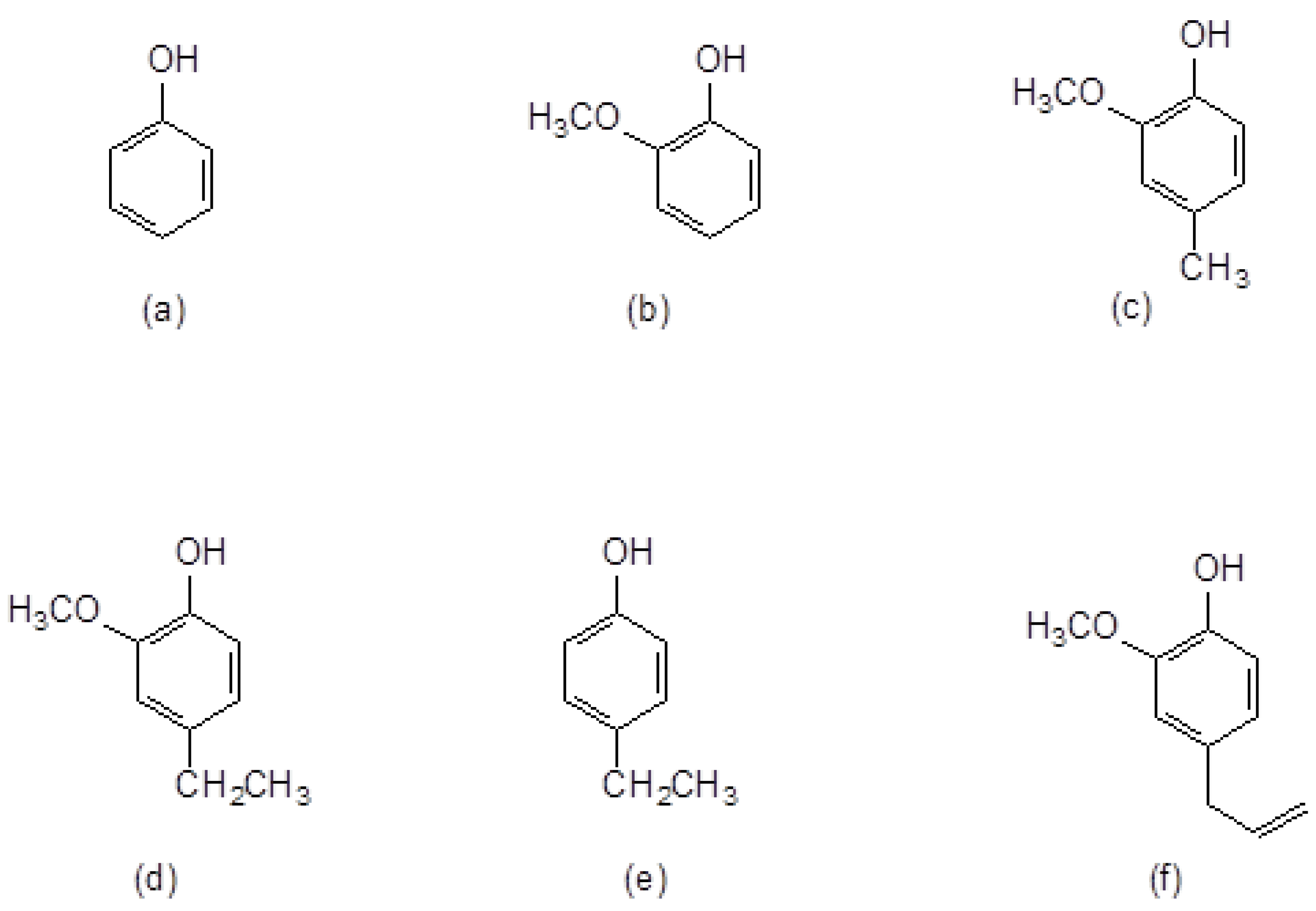

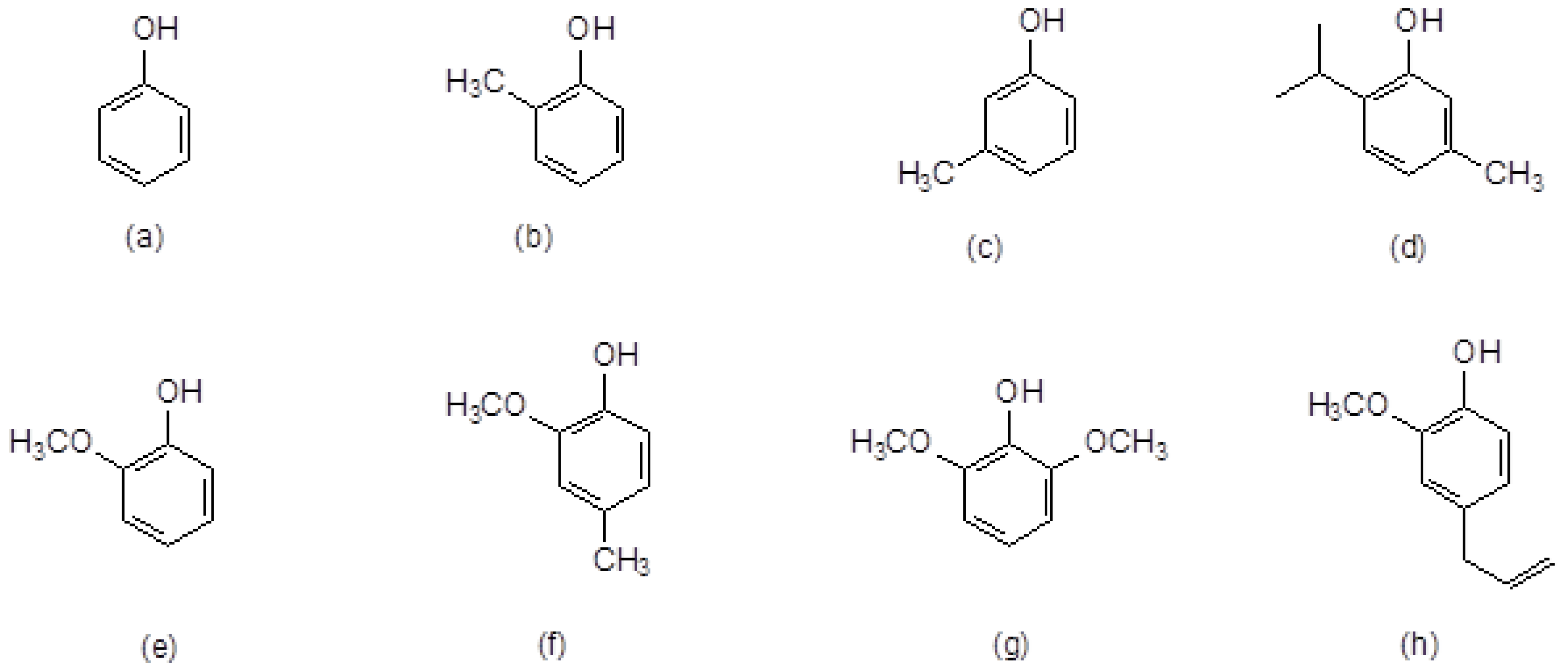

- Kennison, K. R.; Gibberd, M. R.; Pollnitz, A. P. ; Wilkinson, K. L. “Smoke-Derived Taint in wine: The Release of Smoke-Derived Volatile Phenol during Fermentation of Merlot Juice following Grapevine Exposure to Smoke.” J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7379. [CrossRef]

- Krstic, M. P.; Johnson, D. L.; Herderich, M. J. “Review of smoke-taint in wine: smoke-derived volatile phenols and their glycosidic metabolites in grapes and vines as biomarkers for smoke exposure and their role in the sensory perception of smoke-taint” Aust. J. Grape and Wine Res. 2015, 21, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

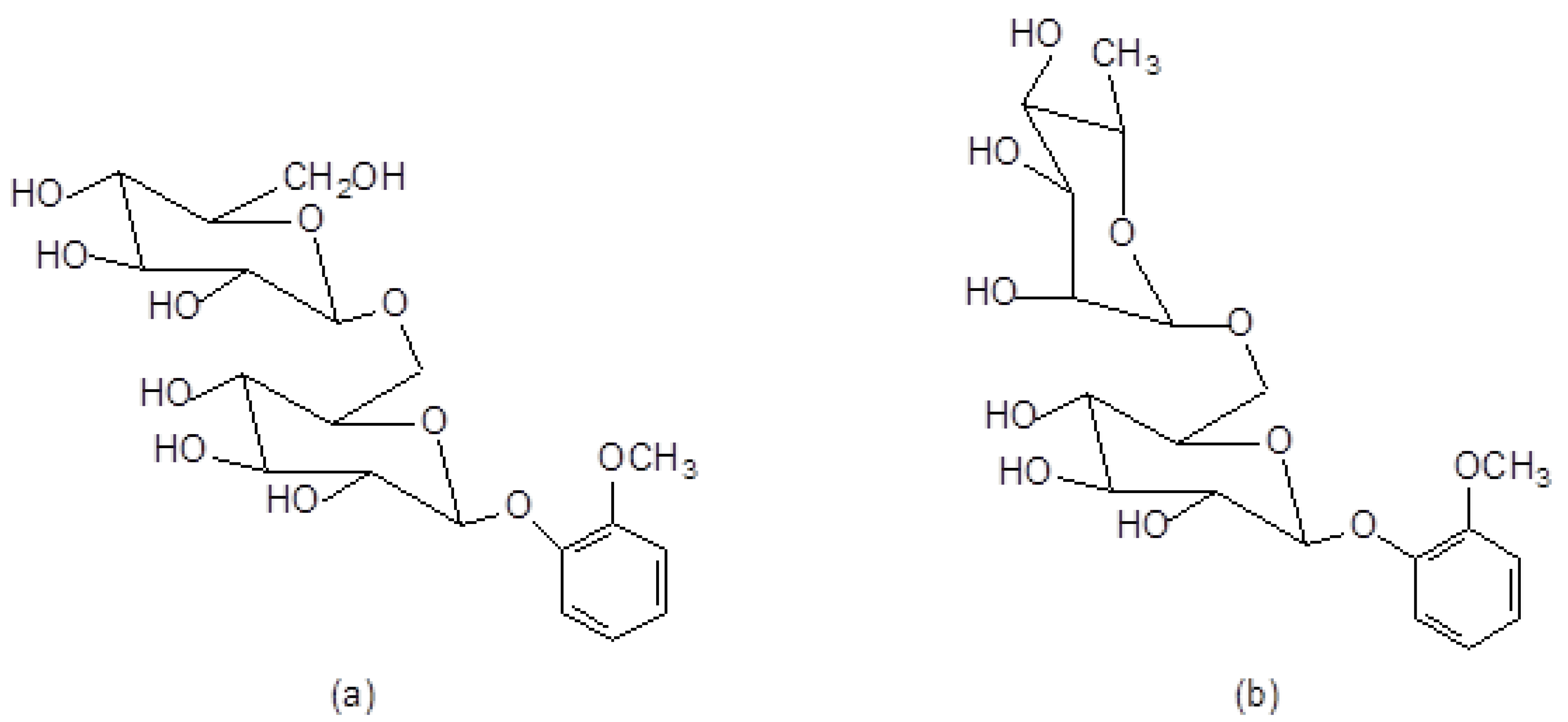

- Hayasaka, Y.; Parker, M.; Baldock, G.A.; Pardon, K.J.; Black, C. A.; Jeffery, D. W.; Herderich, M.J. “Assessing the impact of smoke exposure in grapes: development and validation of a HPLC-MS/MS method for the quantitative analysis of smoke derived phenolic glycosides in grapes and wine” J. Ag. Food Chem. 2012, 61, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noestheden, M.; Dennis, E. G.; Romero-Montalvo, E.; DiLabio, G. A.; Zandberg, W. F. “Detailed characterization of glycosylated sensory-active volatile phenols in smoke-exposed grapes and wine” Food Chem. 2018, 259, 247. 259. [CrossRef]

- Summerson, V.; Viejo, C. G.; Pang, A.; Torrico, D. D.; Funetes, S. “Review of the Effects of Grapevine Smoke Exposure and Technologies to Assess Smoke Contamination and Taint in Grapes and Wine. ” Beverages 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, P.; Dorenbach, P.; Amcerchan, G.; Keiffer, R. F.; Lizama-Chamu, I.; Ruthenburg, T.; McCauly, E. P.; McGourty, G. “Natural Product Phenolic Diglycosides Created from Wildfires, Defining Their Impact on California and Oregon Grapes and Wines” J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information on the Spotted Lanternfly is available from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant-pests-diseases/slf (last accessed 25). 20 January.

- Pierce’s Disease is a bacterial disease that affects grapevines and other plants. It's caused by the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa, which lives in the plant's water-conducting system. The disease is spread by sap-feeding insects, such as leafhoppers. The California Department of Food and Agriculture's Pierce's Disease and Glassy-winged Sharpshooter PD/GWSS Board) provides funding support to research and outreach projects focused on protecting vineyards, preventing the spread of pests and diseases, and delivering practical and sustainable solutions.

- Information on the glassy-winged sharpshooter is available from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) at www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/invertebrates/glassy-winged-sharpshooter (last accessed January 2025).

- Please see https://agrilifetoday.tamu.edu/2024/09/03/texas-wine-grape-growers-see-uptick-in-pierces-disease/ (last accessed January 2025).

- Current information on invasive species in the time of climate change and about which one should be aware can be found at https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/subject/climate-change (last accessed January 2025).

- Ruuskanen, S.; Buchs, B.; Nissinen, R.; Puigbò, P.; Rainio, M.; Saikkonen, K.; Helander, M. “Ecosystem consequences of herbicides: the role of the microbiome” Trends Eco. and Evo. 2023, 38, 35, and Anthony, M. A.; Bender, S. F.; van der Heijend, M. G. A. “Enumerating soil biodiversity”. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, 33, e2304663120. 10.1073/pnas.2304663120. [Google Scholar]

- Please see (a) Raza, M. M.; Bebber, D. P. “Climate change and plant pathogens” Curr. Opinoin Microbio. 2023, 70, 102233, and (b) Singh, B. K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J.E.; Liu, H.; Trivdei, P. “Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward” Nat. Rev. Microbio. 2023. 10.1038/s41579-023-00900-7. Additionally, although concerned with infectious diseases from which humans might suffer, it is important to realize that the plants may suffer from similar problems.as seen at the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic infectious Diseases (https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/topics-programs/climate-infectious-disease.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/what-we-do/climate-change-and-infectious-diseases/index.html) (last accessed January 2025) and Mora, C.; McKenzie, T.; Gaw, I.M; Dean, J.M.; von Hammerstein, H.; Knudson, T. A.; Setter, R. O. ; Smith, C. Z.; Webster, K M.; Patz, J. A.; Franklin, E. C. “Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 869. 10,1038/s51558-022-01426-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, F. R.; Pavlick, R.; Trolley, G. R.; Aggarwal, S.; Sousa, D.; Starr, C.; Forrestel, E. J. ; Bolton, S; del Mar Alsina, M.; Dokoozlian, N.; Gold, K. M. “Scalable early detection of grapevine virus infection with airborne imaging spectroscopy”. Phytopathology 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C. Remote sensing for Crops Spots Pests and Pathogens. ACS Central Science, 2023; 9, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).