Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

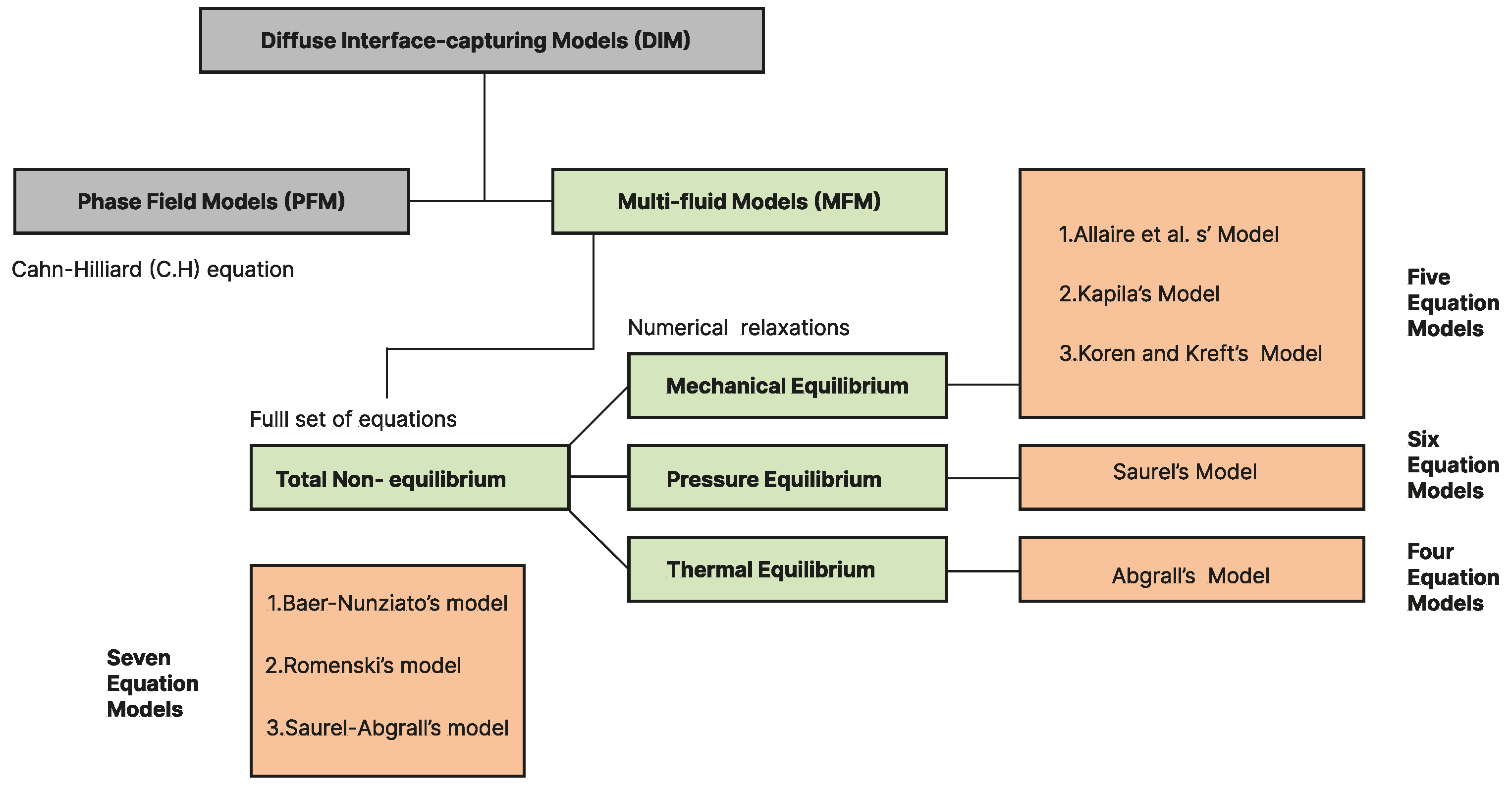

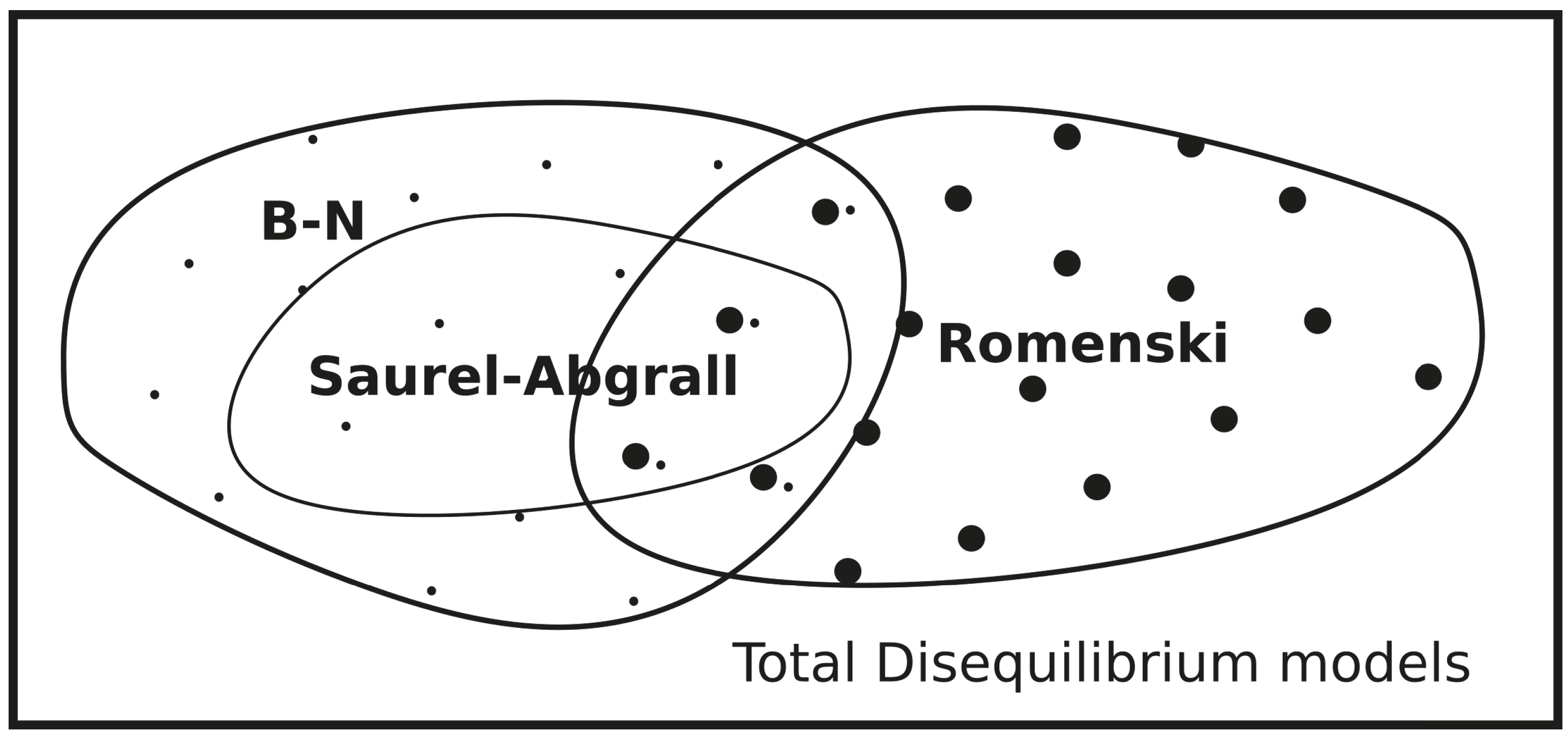

2. Total Non-Equilibrium Models

2.1. Baer-Nunziato Non-Equilibrium Model

2.1.1. Volume Advection

2.1.2. Mass Conservation

2.1.3. Momentum Conservation

2.1.4. Energy Balance

- Velocity Relaxation (u-Relaxation): As the relaxation coefficient tends to infinity, momentum transfer between phases leads to velocity equilibrium ().

- Pressure Relaxation (p-Relaxation): With approaching infinity, volume transfer occurs between phases, resulting in pressure equilibrium ().

- Thermal Relaxation (T-Relaxation): As tends to infinity, heat exchange between phases establishes thermal equilibrium ().

- Chemical Relaxation (-Relaxation): As approaches infinity, mass transfer between phases ensures chemical equilibrium.

2.2. Saurel-Abgrall Non-Equilibrium Model

2.2.1. Volume Advection:

2.2.2. Mass Conservation:

2.2.3. Momentum Conservation:

2.2.4. Energy Balance:

2.3. Romenski Seven-Equation Model

3. Mechanical Equilibrium Model

4. Velocity Equilibrium or Pressure-Disequilibrium Model

5. Thermal and Mechanical Equilibrium Model by Abgrall et al.

6. Choice of Equation of State (EoS)

6.1. Ideal Gas EoS

6.2. Tait’s EoS

6.3. Van der Waals Gas EoS

6.4. Stiffened Gas EoS

6.5. Noble Abel Stiffened Gas (NASG) EoS

6.6. Mie-Grüneisen EoS

| EoS | Used in | Equations |

| Ideal gas | [48] | |

| Tait | [3,4,57,58] | |

| Van der Waals | [58,64] | |

| Stiffened Gas | [52,54,55,56,65,66,67] | |

| NASG | [60,61,62,63,64,68,68] | |

| Mie–Gruneisen | [69,70,71,72] |

7. High-Order Methods for Diffuse Interface-Capturing Models

| High-Order Method | Framework | Literature |

| DG | Finite Element | [67,73,104] |

| ADER-DG | Finite Element | [75] |

| WENO | Finite Volume/Finite Difference | [53,54,91,105,106,107] |

| WENO-Z, WENO-JS | Finite Volume/Finite Difference | [52,76,77] |

| CWENO | Finite Volume/Finite Difference | [65,66] |

| TENO | Finite Volume/Finite Difference | [78] |

| MOOD | Finite Volume/Finite Difference | [79] |

| MUSCL | Finite Volume/Finite Difference | [52,80,81,83,84,85,108,109] |

| WENO-DG, MUSCL-DG | Hybrid DG-FV | [86,87,110] |

8. Methods for Minimizing Numerical Smearing in Compressible Multiphase Flow

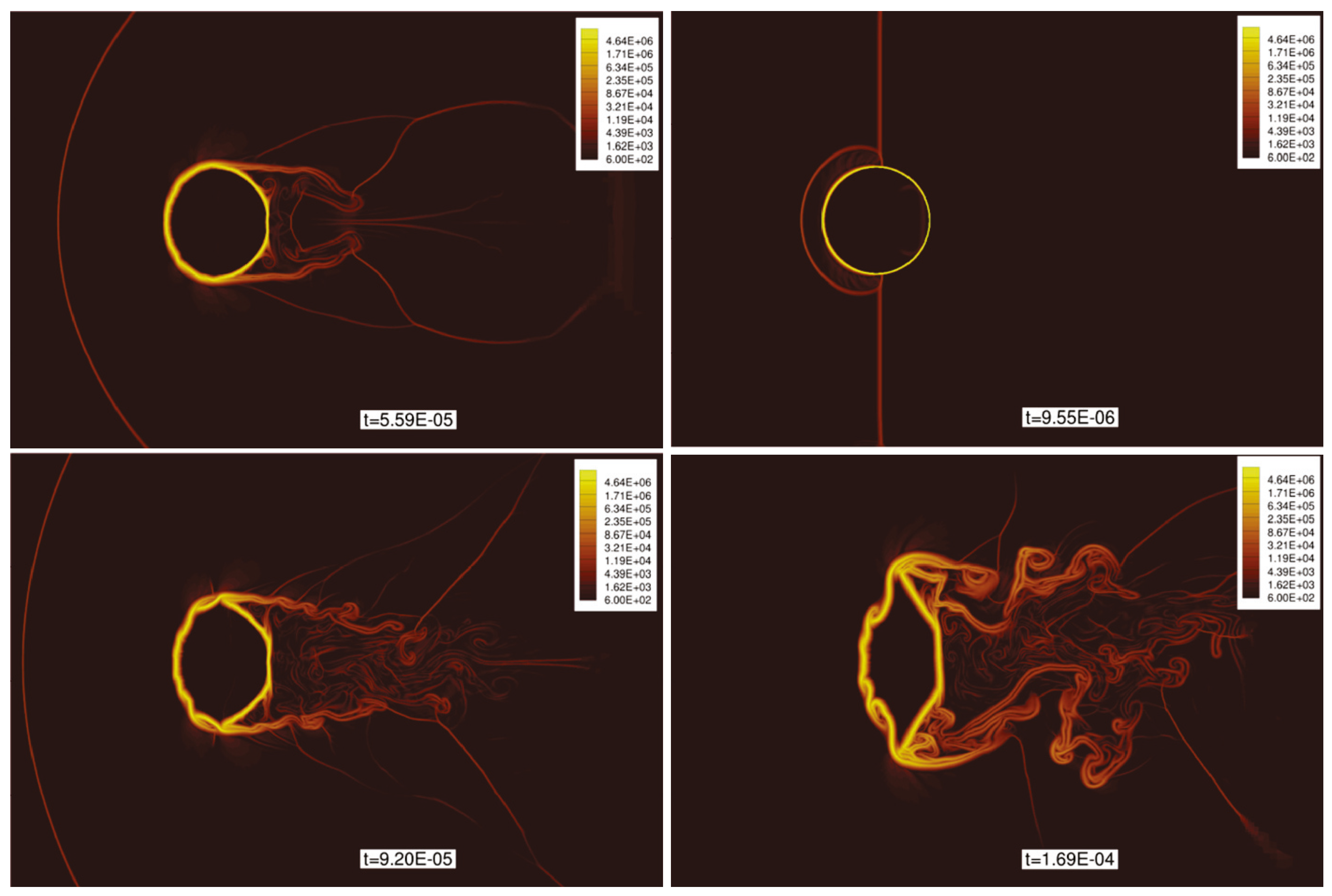

8.1. Anti-Diffusion Interface Sharpening (ADIS) Technique

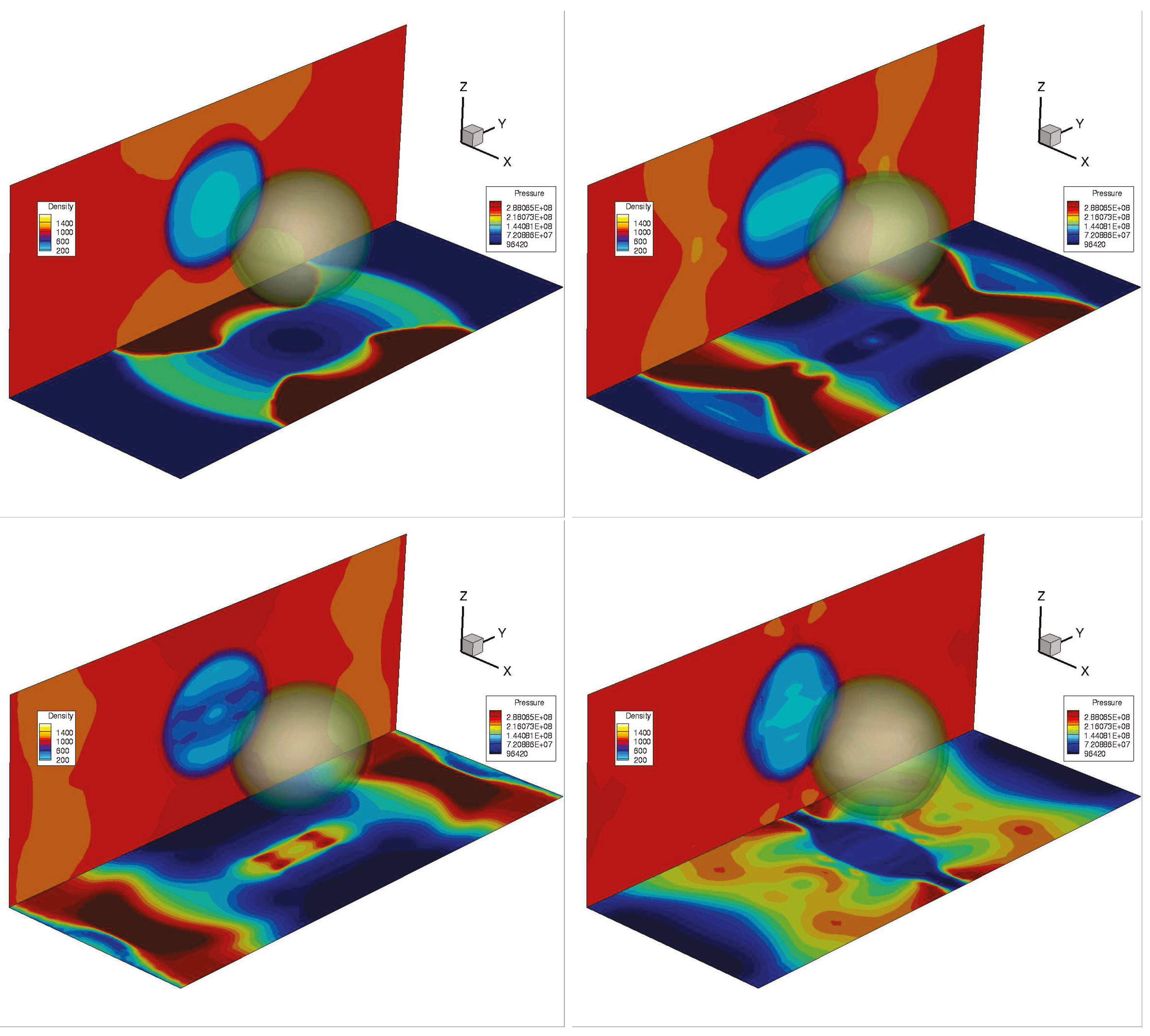

8.2. THINC Interface Sharpening Technique

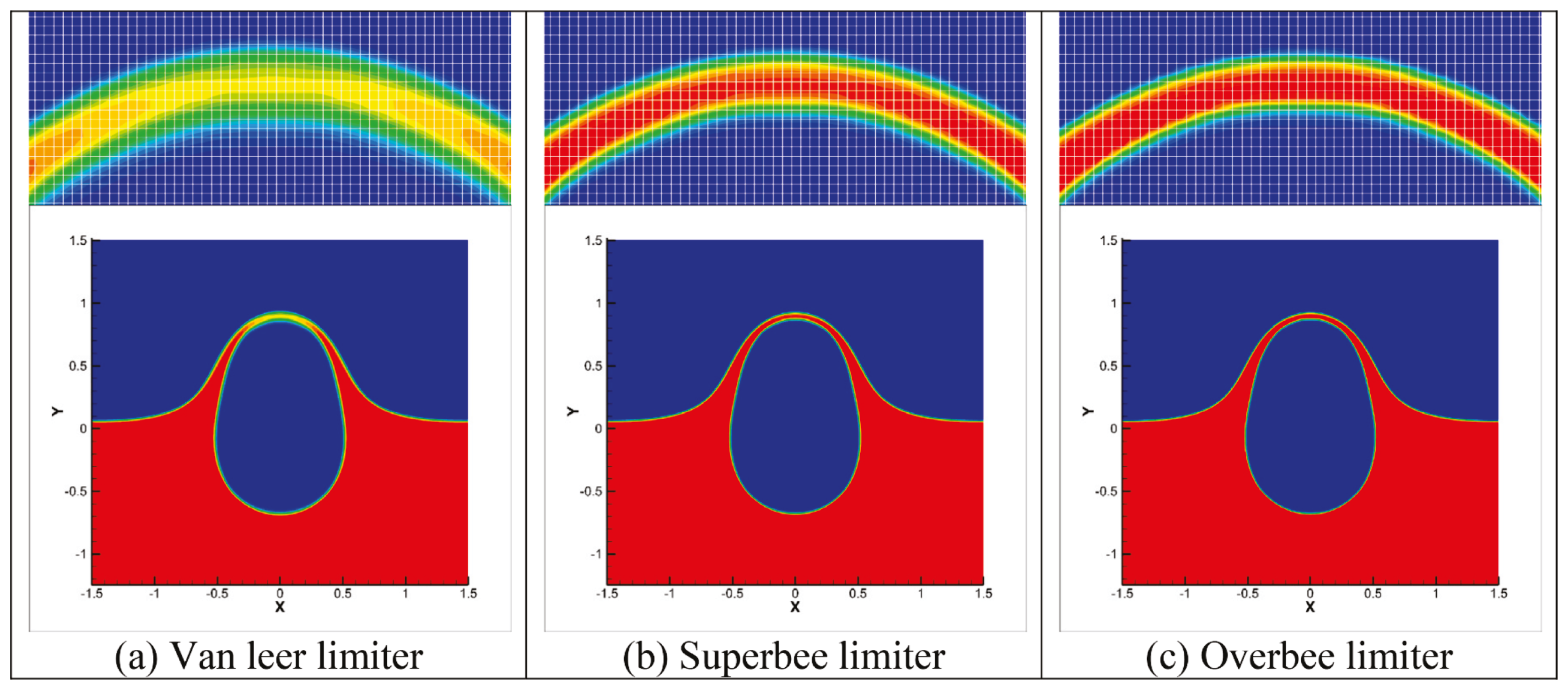

8.3. Limiter Techniques (e.g., TVD, BVD)

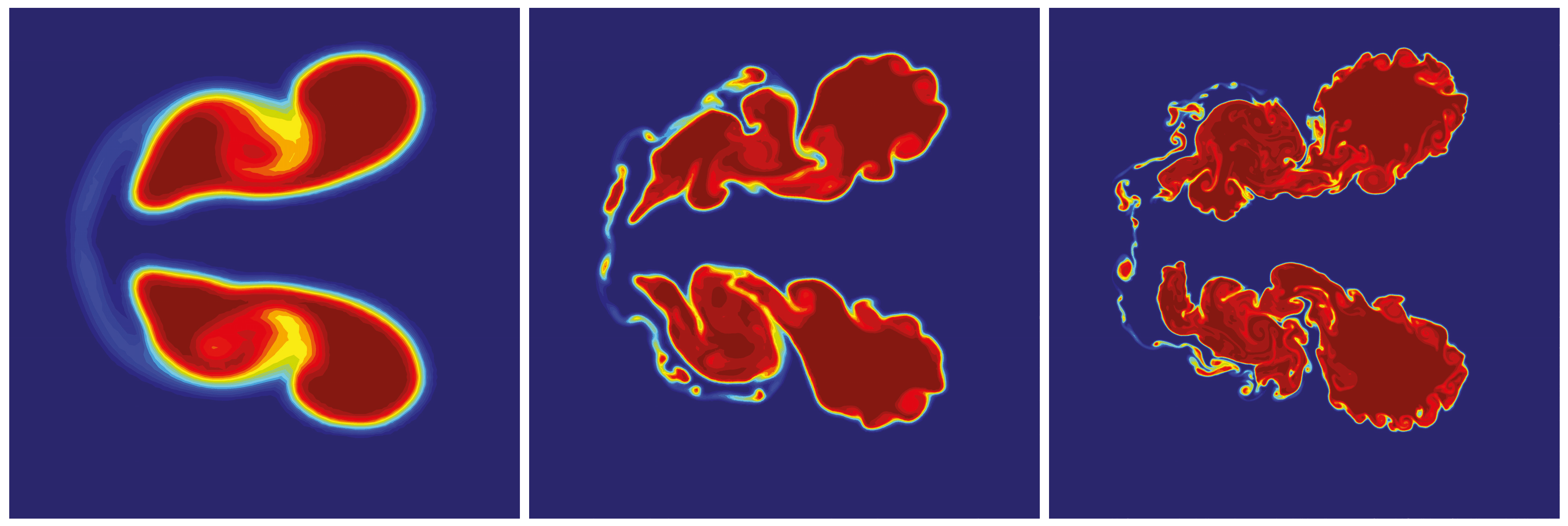

8.4. Interface Compression Technique

| Methods | 5-eqn. DIM | 6-eqn. DIM | 7-eqn. DIM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-diffusion | U [51,111] | U [111,113] | NYU |

| THINC | U [58,64,114,117,118] | U [115] | NYU |

| Limiter Techniques (e.g., TVD, BVD) | U [55,88,119,120] | NYU | NYU |

| Interface Compression | U [81,82,121,122] | NYU | NYU |

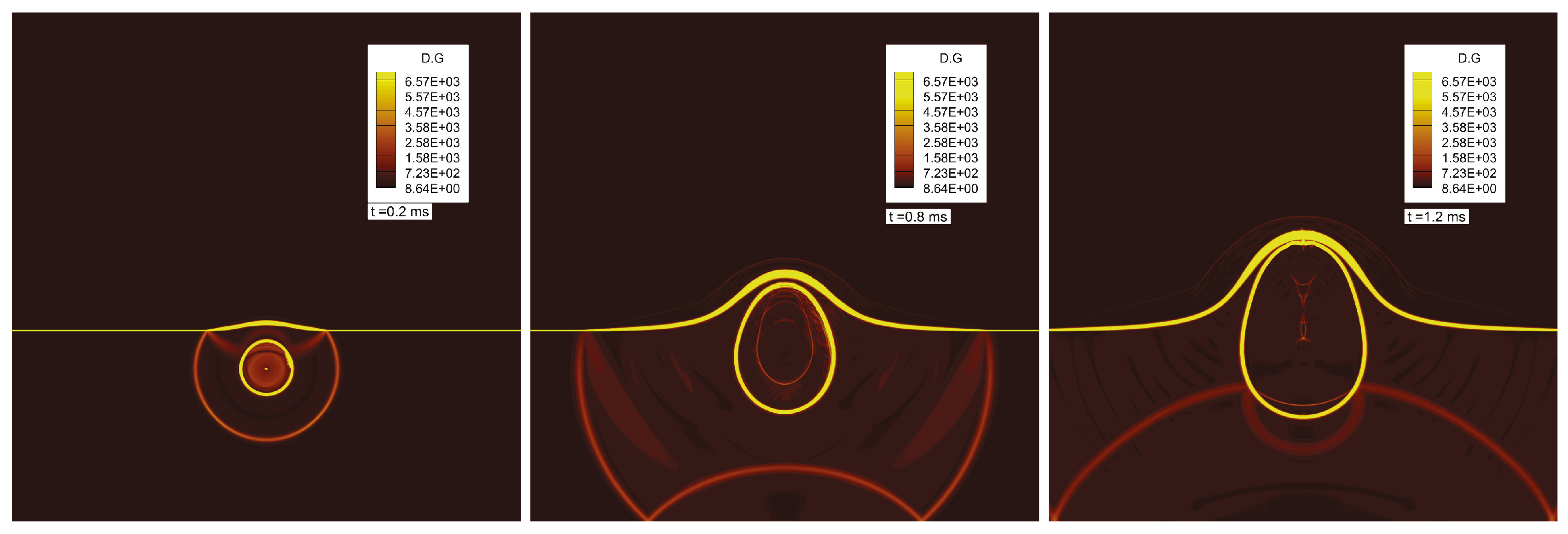

9. Selected Test Cases Used for Verification and Validation of DIM Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIM | Diffuse Interface Models |

| DG | Discontinuous Galerkin |

| PFM | Phase Field Models |

| MFM | Multi-Fluid Models |

| WENO | Weighted Essentially Non-Oscillatory scheme |

| CWENO | Central Weighted Essentially Non-Oscillatory scheme |

| TENO | Targeted Essentially Non-oscillatory scheme |

| MOOD | Multidimensional Optimal Order Detection |

| FV | Finite Volume |

| FD | Finite Difference |

| DG | Discontinuous Galerkin (DG) |

References

- Tryggvason, G.; Bunner, B.; Esmaeeli, A.; Juric, D.; Al-Rawahi, N.; Tauber, W.; Han, J.; Nas, S.; Jan, Y.J. A Front-Tracking Method for the Computations of Multiphase Flow. Journal of Computational Physics 2001, 169, 708–759. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, N.V.; Schmidt, A.A. Multiphase phenomena in underwater explosion. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 2015, 60, 367–373. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Khoo, B.; Xie, W. Isentropic one-fluid modelling of unsteady cavitating flow. Journal of Computational Physics 2004, 201, 80–108. [CrossRef]

- Wenfeng, X. A numerical simulation of underwater shock-cavitation-structure interaction. PhD Thesis 2005, 53, 1–207.

- Baer, M.; Nunziato, J. A two-phase mixture theory for the deflagration-to-detonation transition (ddt) in reactive granular materials. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 1986, 12, 861–889. [CrossRef]

- Kapila, A.K.; Menikoff, R.; Bdzil, J.B.; Son, S.F.; Stewart, D.S. Two-phase modeling of deflagration-to-detonation transition in granular materials: Reduced equations. Physics of Fluids 2001, 13, 3002–3024. [CrossRef]

- Allaire, G.; Clerc, S.; Kokh, S. A five-equation model for the simulation of interfaces between compressible fluids. Journal of Computational Physics 2002, 181, 577–616. [CrossRef]

- Saurel, R.; Abgrall, R. Simple method for compressible multifluid flows. SIAM Journal of Scientific Computing 1999, 21, 1115–1145. [CrossRef]

- Murrone, A.; Guillard, H. A five equation reduced model for compressible two phase flow problems. Journal of Computational Physics 2005, 202, 664–698.

- Rémi, A.; Paola, B.; Barbara, R. On the simulation of multicomponent and multiphase compressible flows. Computers and Fluids 2020, 64, 43–63. [CrossRef]

- E., R. Multiphase flow modeling based on the hyperbolic thermodynamically compatible systems theory. AIP Conference Proceedings 2015, 1648. [CrossRef]

- Lamorgese, A.G.; Molin, D.; Mauri, R. Phase Field Approach to Multiphase Flow Modeling. Milan Journal of Mathematics 2011, 79, 597–642. [CrossRef]

- Gaydos, J. The Laplace equation of capillarity. In Drops and bubbles in interfacial research; MÖbius, D.; Miller, R., Eds.; Elsevier, 1998; Vol. 6, Studies in Interface Science, pp. 1–59. [CrossRef]

- S.D.Poisson. Nouvelle the´orie de l’action capillaire. Bachelier P´ere et Fils, Paris 1831, pp. 1–306.

- Clerk-Maxwell, J. On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances. In Conferences Held in Connection with the Special Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus, 1876: Physics and Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2015; pp. 145–163.

- Gibbs, J.W. On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances; Vol. v.3 (1874-1878), New Haven, Published by the Academy, 1866-, 1874; pp. 108–248. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/7541.

- Anderson, D.M.; McFadden, G.B.; Wheeler, A.A. Diffuse-Interface methods in fluid mechanics. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 1998, 30, 139–165. [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. XVI. On the instability of a cylinder of viscous liquid under capillary force. Philosophical Magazine Series 1 1892, 34, 145–154.

- Rowlinson, J. Translation of J. D. van der Waals’ “The thermodynamik theory of capillarity under the hypothesis of a continuous variation of density. Journal of Statistical Physics 1979, 20, 197–200. [CrossRef]

- Cahn, J.W.; Hilliard, J.E. Free Energy of a Nonuniform System. III. Nucleation in a Two-Component Incompressible Fluid. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1959, 31, 688–699. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M. A theory of nucleation for solid metallic solutions. D.Se. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge 1956, pp. 1–136.

- Domb, C.; Green, M.; Lebowitz, J. Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena; Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena, Academic Press, 1972.

- Andrea G. Lamorgese, D.M.; Mauri, R. Diffuse Interface (D.I.) Model for Multiphase Flows; Springer Vienna, 2012; pp. 1–72. [CrossRef]

- Siggia, E.D. Late stages of spinodal decomposition in binary mixtures. Phys. Rev. A 1979, 20, 595–605. [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.C.; Halperin, B.I. Theory of dynamic critical phenomena. Reviews of Modern Physics 1977, 49, 435–479. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. A review on the Cahn–Hilliard equation: classical results and recent advances in dynamic boundary conditions. Electronic Research Archive 2022, 30, 2788–2832. [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Feng, X. Chapter 5 - The phase field method for geometric moving interfaces and their numerical approximations. In Geometric Partial Differential Equations - Part I; Bonito, A.; Nochetto, R.H., Eds.; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 21, Handbook of Numerical Analysis, pp. 425–508. [CrossRef]

- Hirt, C.; Nichols, B. Volume of fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries. Journal of Computational Physics 1981, 39, 201–225. [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S. The Method of Volume Averaging; Kluwer Academic, 1999; pp. 1–218. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M.; Mishima, K. Two-fluid model and hydrodynamic constitutive relations. Nuclear Engineering and Design 1984, 82, 107–126. [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.; Saurel, R.; Petitpas, F.; Daniel, E.; Métayer, O.; Gavrilyuk, S.; Dovetta, N. Progress in the Development of Compressible, Multiphase Flow Modeling Capability for Nuclear Reactor Flow Applications. Idaho National Laboratory 2008, pp. 1–215. [CrossRef]

- Dobran, F. Theory of Structured Multiphase Mixtures; Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 1–225. [CrossRef]

- Murrone, A.; Guillard, H. A five equation reduced model for compressible two phase flow problems. Journal of Computational Physics 2005, 202, 664–698.

- Drew, Donald A.and Passman, S.L. Ensemble Averaging. In: Theory of Multicomponent Fluids. Applied Mathematical Sciences 1999, pp. 92–104. [CrossRef]

- Romenski, E.; Toro, E. Compressible two-phase flows: two-pressure models and numerical methods. Comput. Fluid Dyn. J. 2004, 13, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Lund, H. A Hierarchy of Relaxation Models for Two-Phase Flow. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 2012, 72, 1713–1741. [CrossRef]

- FLåtten, T.; Lund, H. Relaxation two-phase flow models and the subcharacteristic condition. Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 2011, 21, 2379–2407. [CrossRef]

- Andrianov, N. Analytical and numerical investigation of two-phase flows. PhD thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Andrianov, N.; Saurel, R.; Warnecke, G. A Simple Method for Compressible Multiphase Mixtures and Interfaces. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2003, 41, 109 – 131. [CrossRef]

- Zein, A.; Hantke, M.; Warnecke, G. Modeling phase transition for compressible two-phase flows applied to metastable liquids. Journal of Computational Physics 2010, 229, 2964–2998. [CrossRef]

- Furfaro, D.; Saurel, R. A simple HLLC-type Riemann solver for compressible non-equilibrium two-phase flows. Computers & Fluids 2015, 111, 159–178. [CrossRef]

- Ambroso, A.; Chalons, C.; Raviart, P.A. A Godunov-type method for the seven-equation model of compressible two-phase flow. Computers and Fluids 2012, 54, 67–91. [CrossRef]

- Coquel, F.; Gallouët, T.; Hérard, J.M.; Seguin, N. Closure laws for a two-fluid two-pressure model. Comptes Rendus Mathematique 2002, 334, 927–932. [CrossRef]

- Zein, A. Numerical methods for multiphase mixture conservation laws with phase transition. PhD thesis, Otto-von-Guericke-Universit¨at Magdeburg, 2010.

- Thein, F.; Romenski, E.; Dumbser, M. Exact and Numerical Solutions of the Riemann Problem for a Conservative Model of Compressible Two-Phase Flows. Journal of Scientific Computing 2022, 93, 1–60. [CrossRef]

- Romenski, E.; Reshetova, G.; Peshkov, I. Thermodynamically compatible hyperbolic model of a compressible multiphase flow in a deformable porous medium and its application to wavefields modeling. AIP Conference Proceedings 2021, 2448, 2–19. [CrossRef]

- Saurel, R.; Pantano, C. Diffuse-Interface Capturing Methods for Compressible Two-Phase Flows. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2018, 50, 105–130. [CrossRef]

- Saurel, R.; Lemetayer, O. A multiphase model for compressible flows with interfaces, shocks, detonation waves and cavitation. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2001, 431, 239–271. [CrossRef]

- Demou, A.D.; Scapin, N.; Pelanti, M.; Brandt, L. A pressure-based diffuse interface method for low-Mach multiphase flows with mass transfer. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 448, 110730. [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, E. On the treatment of contact discontinuities using WENO schemes. Journal of Computational Physics 2011, 230, 8665–8668. [CrossRef]

- Shyue, K.M. An Anti-Diffusion based Eulerian Interface-Sharpening Algorithm for Compressible Two-Phase Flow with Cavitation. Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Cavitation 2012, 268, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Daramizadeh, A.; Ansari, M.R. Numerical simulation of underwater explosion near air-water free surface using a five-equation reduced model. Ocean Engineering 2015, 110, 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Schmidmayer, K.; Bryngelson, S.H.; Colonius, T. An assessment of multicomponent flow models and interface capturing schemes for spherical bubble dynamics. Journal of Computational Physics 2020, 402, 109080. [CrossRef]

- Coralic, V.; Colonius, T. Finite-volume WENO scheme for viscous compressible multicomponent flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2014, 274, 95–121. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A simple and effective five-equation two-phase numerical model for liquid-vapor phase transition in cavitating flows. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 2020, 132, 1–47. [CrossRef]

- Haimovich, O.; Frankel, S.H. Numerical simulations of compressible multicomponent and multiphase flow using a high-order targeted ENO (TENO) finite-volume method. Computers and Fluids 2017, 146, 105–116. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Young, Y.; Liu, T.; Khoo, B. Dynamic response of deformable structures subjected to shock load and cavitation reload. Computational Mechanics 2007, 40, 667–681. [CrossRef]

- Jolgam, S.; Ballil, A.; Nowakowski, A.; Nicolleau, F. On Equations of State for Simulations of Multiphase Flows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, 2012, Vol. 3, pp. 1–6.

- Harlow, F.H.; Amsden, A.A. Numerical calculation of almost incompressible flow. Journal of Computational Physics 1968, 3, 80–93. [CrossRef]

- Le Métayer, O.; Saurel, R. The Noble-Abel Stiffened-Gas equation of state. Physics of Fluids 2016, 28, 046102. [CrossRef]

- Radulescu, M.I. On the Noble-Abel stiffened-gas equation of state. Physics of Fluids 2019, 31, 111702. [CrossRef]

- Péden, B.; Carmona, J.; Boivin, P.; Schmitt, T.; Cuenot, B.; Odier, N. Numerical assessment of Diffuse-Interface method for air-assisted liquid sheet simulation. Computers & Fluids 2023, 266, 106022. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.L.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, H.G. Homogeneous mixture model simulation of compressible multi-phase flows at all Mach number. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 2021, 143, 103745. [CrossRef]

- S.Richard.; B.Pierre.; Olivier, L. A general formulation for cavitating, boiling and evaporating flows. Computers & Fluids 2016, 128, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsanis, P.; Adebayo, E.; Merino, A.; Arjona, A.; Skote, M. CWENO Finite-Volume Interface Capturing Schemes for Multicomponent Flows Using Unstructured Meshes. Journal of Scientific Computing 2021, 89. [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, E.; Tsoutsanis, P.; Jenkins, K. IMPLEMENTATION OF CWENO SCHEMES FOR COMPRESSIBLE MULTICOMPONENT/MULTIPHASE FLOW USING INTERFACE CAPTURING MODELS. 8th European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, Y.; Ma, S.; Qihang, H.; Zhang, A.M. A γ-based compressible multiphase model with cavitation based on discontinuous Galerkin method. Physics of Fluids 2025, 37. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, H.; Sheng, Z.; Hao, Y.; Liu, J. Numerical research on the cavitation effect induced by underwater multi-point explosion near free surface. AIP Advances 2023, 13, 015021. [CrossRef]

- Price, M.A.; Nguyen, V.T.; Hassan, O.; Morgan, K. A method for compressible multimaterial flows with condensed phase explosive detonation and airblast on unstructured grids. Computers and Fluids 2015, 111, 76–90. [CrossRef]

- Shyue, K.M. A Fluid-Mixture Type Algorithm for Compressible Multicomponent Flow with van der Waals Equation of State. Journal of Computational Physics 1999, 156, 43–88. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zong, Z.; Sun, L. A Mie-Grüneisen mixture Eulerian model for underwater explosion. Engineering Computations 2014, 31, 425–452.

- Shyue, K.M. A Fluid-Mixture Type Algorithm for Compressible Multicomponent Flow with Mie–Grüneisen Equation of State. Journal of Computational Physics 2001, 171, 678–707. [CrossRef]

- Franquet, E.; Perrier, V. Runge-Kutta discontinuous Galerkin method for the approximation of Baer and Nunziato type multiphase models. Journal of Computational Physics 2012, 231, 4096–4141. [CrossRef]

- Rhebergen, S.; Bokhove, O.; van der Vegt, J.J. Discontinuous Galerkin finite element methods for hyperbolic nonconservative partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2008, 227, 1887–1922. [CrossRef]

- Chiocchetti, S.; Peshkov, I.; Gavrilyuk, S.; Dumbser, M. High order ADER schemes and GLM curl cleaning for a first order hyperbolic formulation of compressible flow with surface tension. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 426, 109898. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Daramizadeh, A. Numerical simulation of compressible two-phase flow using a diffuse interface method. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow 2013, 42, 209–223. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shu, C. A fifth-order high-resolution shock-capturing scheme based on WENO-Z finite difference method. Physics of Fluids 2019, 33, 056104.

- Li, Q.; Lv, Y.; Fu, L. A high-order diffuse-interface method with TENO-THINC scheme for compressible multiphase flows. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 2024, 173, 104732. [CrossRef]

- Farmakis, P.; Tsoutsanis, P.; Nogueira, X. WENO schemes on unstructured meshes using a relaxed a posteriori MOOD limiting approach. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2020, 363. [CrossRef]

- Schmidmayer, K.; Petitpas, F.; Le Martelot, S.; Daniel, E. ECOGEN: An open-source tool for multiphase, compressible, multiphysics flows. Computer Physics Communications 2019, 251, 107093. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K.; Pantano, C.; Freund, J.B. An interface capturing method for the simulation of multi-phase compressible flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2010, 229, 7411–7439. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K. Nonlinear preconditioning for efficient and accurate interface capturing in simulation of multicomponent compressible flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2014, 276, 508–540. [CrossRef]

- Shyue, K.M.; Xiao, F. An Eulerian Interface Sharpening Algorithm for Compressible Two-phase Flow: The Algebraic THINC Approach. Journal of Computational Physics 2014, 268, 326–354. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Deng, X.; Xie, B.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, F. Low-dissipation BVD schemes for single and multi-phase compressible flows on unstructured grids. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 428, 110088. [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, C.; Pierre, B.; Richard, S. A simple and fast phase transition relaxation solver for compressible multicomponent two-phase flows. Computers & Fluids 2017, 150, 31–45. [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, V.; Skote, M.; Tsoutsanis, P. High-order hybrid DG-FV framework for compressible multi-fluid problems on unstructured meshes. Journal of Computational Physics 2024, 502, 112819. [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, V.; Yuan, D.; Jenkins, K.; Skote, M.; Tsoutsanis, P. Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin-Finite Volume Techniques for Compressible Flows on Unstructured Meshes. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 473, 111755. [CrossRef]

- Chiapolino, A.; Saurel, R.; Nkonga, B. Sharpening diffuse interfaces with compressible fluids on unstructured meshes. Journal of Computational Physics 2017, 340, 389–417. [CrossRef]

- Pandare, A.; Luo, H.; Bakosi, J. An enhanced AUSM+-up scheme for high-speed compressible two-phase flows on hybrid grids. Shock Waves 2018. [CrossRef]

- Faucher, V.; Bulik, M.; Galon, P. Updated VOFIRE Algorithm For Fast Fluid–structure Transient Dynamics with Multi-component Stiffened Gas Flows Implementing Anti-dissipation on Unstructured grids. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2017, 74, 64–89. [CrossRef]

- Dumbser, M. Recent advances in high-order WENO finite volume methods for compressible multiphase flows. AIP Conference Proceedings 2013, 1558, 18–22. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Roe. Approximate Riemann Solvers, Parameter Vectors, and Difference Schemes. Journal of Computational Physics 1981, 43, 357–372.

- Harten, A. High Resolution Schemes for Hyperbolic Conservation Laws. Journal for Computational Physics 1982, 49, 357–393. [CrossRef]

- Toro, E.F. Riemann Solvers and Numerical Methods for Fluid Dynamics—A Practical Introduction. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 1999, 2nd Edition, 624. [CrossRef]

- Arabi, S.; Trépanier, J.Y.; Camarero, R. A simple extension of Roe’s scheme for multi-component real gas flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 388, 178–194. [CrossRef]

- Kong, C. Comparison of Approximate Riemann Solvers. PhD thesis, University of Reading, 2011.

- Tokareva, S.A.; Toro, E.F. A flux splitting method for the Baer–Nunziato equations of compressible two-phase flow. Journal of Computational Physics 2016, 323, 45–74. [CrossRef]

- Lochon, H.; Daude, F.; Galon, P.; Hérard, J. HLLC-type Riemann solver with approximated two-phase contact for the computation of the Baer-Nunziato two-fluid model. Journal of Computational Physics 2016, pp. 733–762. [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, M.; Kapila, A.; Schwendeman, D. An HLLC-type Riemann solver and high-resolution Godunov method for a two-phase model of reactive flow with general equations of state. Journal of Computational Physics 2020, 405, 109180. [CrossRef]

- Andrianov, N.; Warnecke, G. The Riemann problem for the Baer-Nuziato two-phase flow model. Journal of Computational Physics 2004, 195, 434–464. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Luo, K.H.; Kang, Q.J.; He, Y.L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Q. Lattice Boltzmann methods for multiphase flow and phase-change heat transfer. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2016, 52, 62–105. [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Toro, E.; Castro, C. A Path-conservative Method for a Five-equation Model of Two-phase Flow with an HLLC-type Riemann Solver. Computers Fluids 2011, 46, 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Deledicque, V.; Papalexandris, M.V. An exact Riemann solver for compressible two-phase flow models containing non-conservative products. Journal of Computational Physics 2007, 222, 217–245. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Green, C.D. A Quasi-Conservative Discontinuous Galerkin Method for Multi-component Flows Using the Non-oscillatory Kinetic Flux. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 403, 56–78.

- Zhang, W.; Qiu, J. A Quasi-Conservative Alternative WENO Finite Difference Scheme for Solving Compressible Multicomponent Flows. Journal of Scientific Computing 2024, 98, 45. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Freund, J.B.; Pantano, C. A diffuse interface model with immiscibility preservation. Journal of Computational Physics 2013, 252, 290–309. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Doe, A.B. High Order Finite Difference Alternative WENO Scheme for Multi-Component Compressible Flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2021, 402, 123–145. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Inaba, S.; Xie, B.; Shyue, K.M.; Xiao, F. Implementation of BVD (boundary variation diminishing) algorithm in simulations of compressible multiphase flows. Computational Physics 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A simple and effective five-equation two-phase numerical model for liquid-vapor phase transition in cavitating flows. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 2020, 132, 103417. [CrossRef]

- Pandare, A.K.; Waltz, J.; Bakosi, J. A reconstructed discontinuous Galerkin method for multi-material hydrodynamics with sharp interfaces. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 2020, 92, 874–898.

- Kokh, S.; Lagoutière, F. An anti-diffusive numerical scheme for the simulation of interfaces between compressible fluids by means of a five-equation model. Journal of Computational Physics 2010, 229, 2773–2809. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Inaba, S.; Xie, B.; Shyue, K.M.; Xiao, F. High fidelity discontinuity-resolving reconstruction for compressible multiphase flows with moving interfaces. Journal of Computational Physics 2018, 371, 945–966. [CrossRef]

- So, K.; Hu, X.; Adams, N. Anti-diffusion interface sharpening technique for two-phase compressible flow simulations. Journal of Computational Physics 2012, 231, 4304–4323. [CrossRef]

- Taku, N.; Keiichi, K.; Kozo, F. A simple interface sharpening technique with a hyperbolic tangent function applied to compressible two-fluid modeling. Journal of Computational Physics 2014, 258, 95–117. [CrossRef]

- Lingquan, L.; Rainald, L.; Aditya, K.P.; L., H. A vertex-centered finite volume method with interface sharpening technique for compressible two-phase flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2022, 460, 111194. [CrossRef]

- Pandare, A.K.; Waltz, J.; Bakosi, J. Multi-material hydrodynamics with algebraic sharp interface capturing. Computers & Fluids 2021, 215, 104804. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Rong, J.; Zhang, S. An interface sharpening technique for the simulation of underwater explosions. Ocean Engineering 2022, 266, 112922. [CrossRef]

- Majidi, S.; Afshari, A. An adaptive interface sharpening methodology for compressible multiphase flows. Computers and Mathematics with Applications 2016, 72, 2660–2684. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Phan, T.H.; Duy, T.N.; Kim, D.H.; Park, W.G. Fully compressible multiphase model for computation of compressible fluid flows with large density ratio and the presence of shock waves. Computers & Fluids 2022, 237, 105325. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.H.; Causon, D.M.; Qian, L.; Gu, H.B.; Mingham, C.G.; Martínez Ferrer, P. A GPU based compressible multiphase hydrocode for modelling violent hydrodynamic impact problems. Computers and Fluids 2015, 120, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Phan, T.H.; Park, W.G. Numerical modeling of multiphase compressible flows with the presence of shock waves using an interface-sharpening five-equation model. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 2021, 135, 103542. [CrossRef]

- Suhas, S.; Ali, M.; Parviz, M. A conservative diffuse-interface method for compressible two-phase flows. Journal of Computational Physics 2020, 418, 109606. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.F.; Liu, T.G.; Khoo, B.C. The simulation of cavitating flows induced by underwater shock and free surface interaction. Applied Numerical Mathematics 2007, 57, 734–745. [CrossRef]

- Ghidaglia, J.M.; Mrabet, A.A. A regularized stiffened-gas equation of state. Journal of Applied Analysis & Computation 2018, 8, 675–689. [CrossRef]

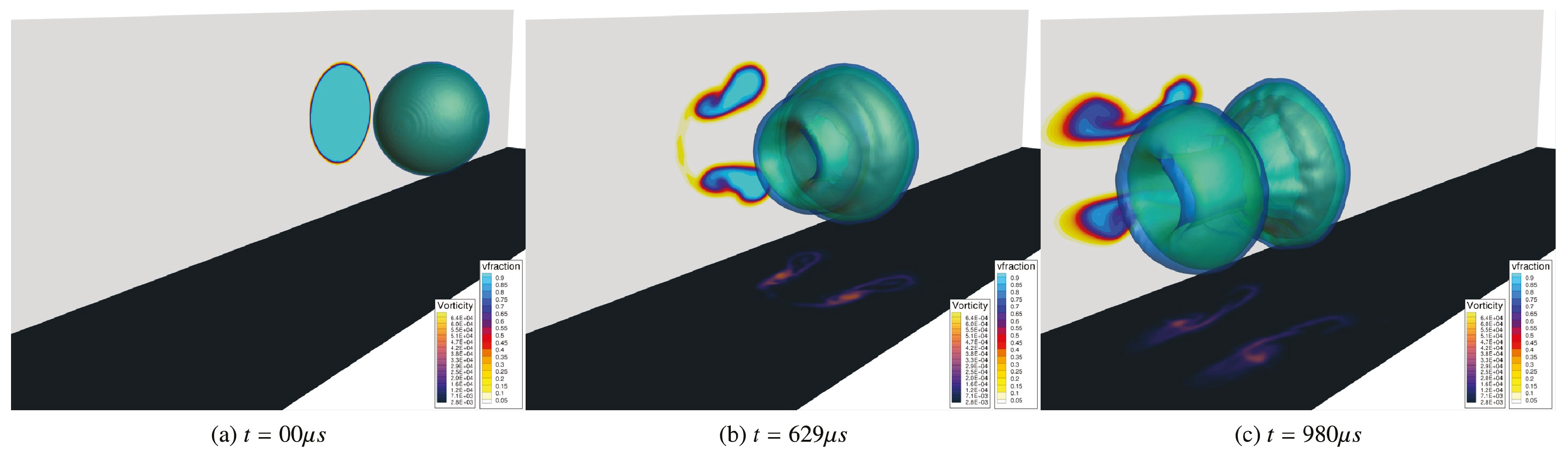

- Adebayo, E.M.; Tsoutsanis, P.; Jenkins, K.W. Application of Central-Weighted Essentially Non-Oscillatory Finite-Volume Interface-Capturing Schemes for Modeling Cavitation Induced by an Underwater Explosion. Fluids 2024, 9.

- Tsoutsanis, P.; Machavolu, S.S.P.K.; Farmakis, P. A relaxed a posteriori MOOD algorithm for multicomponent compressible flows using high-order finite-volume methods on unstructured meshes. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2023, 437, 127544. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Huang, D. A Second-Order Accurate Capturing Scheme for 1D Inviscid Flows of Gas and Water with Vacuum Zones. Journal of Computational Physics 1996, 128, 301–318. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Rutland, C.; Corradini, M. A fully compressible, two-dimensional model of small, high-speed, cavitating nozzles. Atomization and Sprays 1999, 9, 255–276. [CrossRef]

- Le Martelot, S.; Saurel, R.; Nkonga, B. Towards the direct numerical simulation of nucleate boiling flows. International Journal of Multiphase Flow 2014, 66, 62–78. [CrossRef]

- Pelanti, M.; Shyue, K.M. A mixture-energy-consistent six-equation two-phase numerical model for fluids with interfaces, cavitation and evaporation waves. Journal of Computational Physics 2014, 259, 331–357. [CrossRef]

- Saurel, R.; Petitpas, F.; Abgrall, R. Modelling phase transition in metastable liquids: application to cavitating and flashing flows. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2008, 607, 313–350. [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.F.; Sturtevant, B. Interaction of weak shock waves with cylindrical and spherical gas inhomogeneities. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1987, 181, 41–76. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Deiterding, R.; Pan, J.; Ren, Y.X. Consistent high resolution interface-capturing finite volume method for compressible multi-material flows. Computers & Fluids 2020, 202, 104518. [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, E.; Colonius, T. Implementation of WENO schemes in compressible multicomponent flow problems. Journal of Computational Physics 2006, 219, 715–732. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).