Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

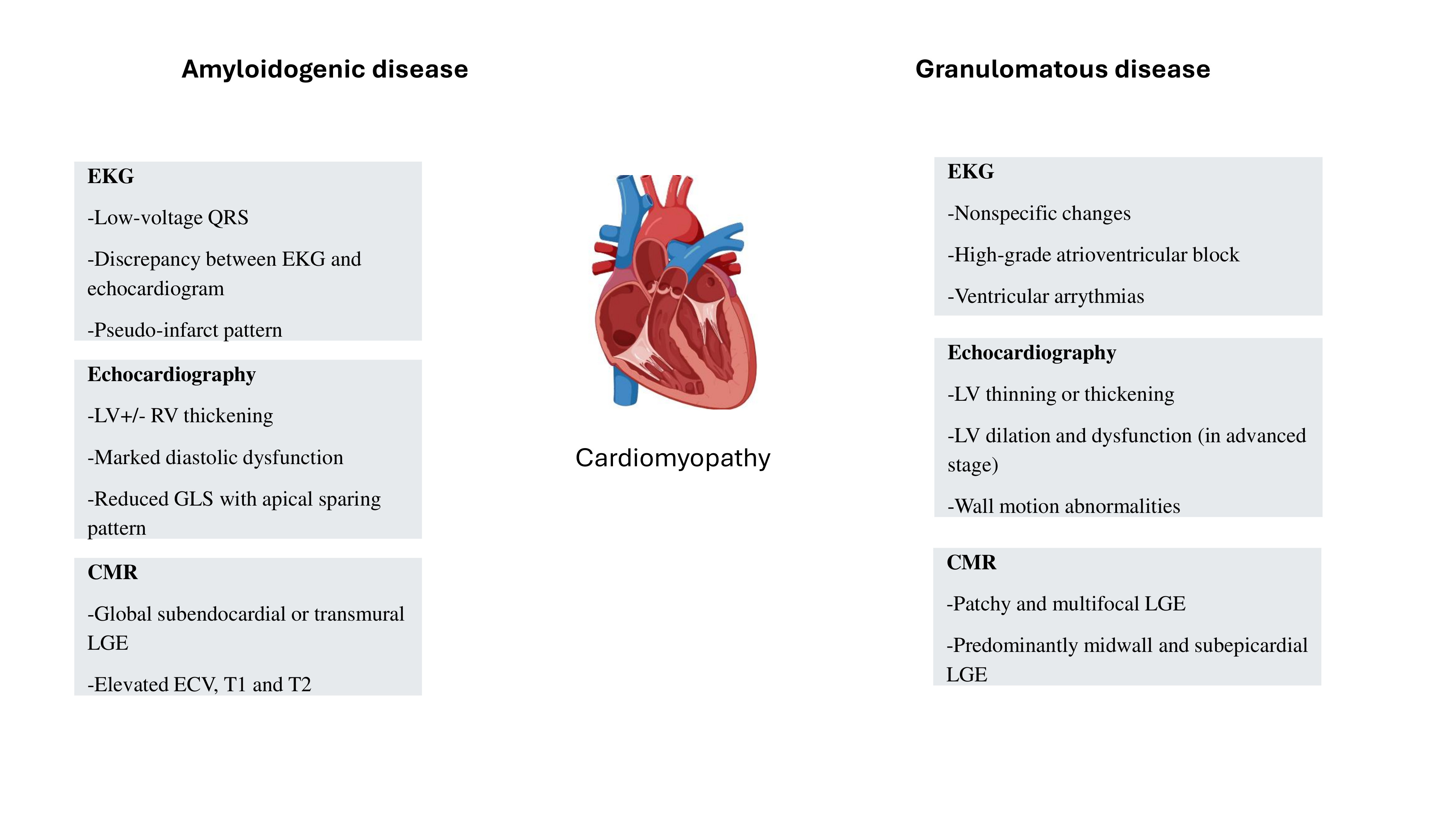

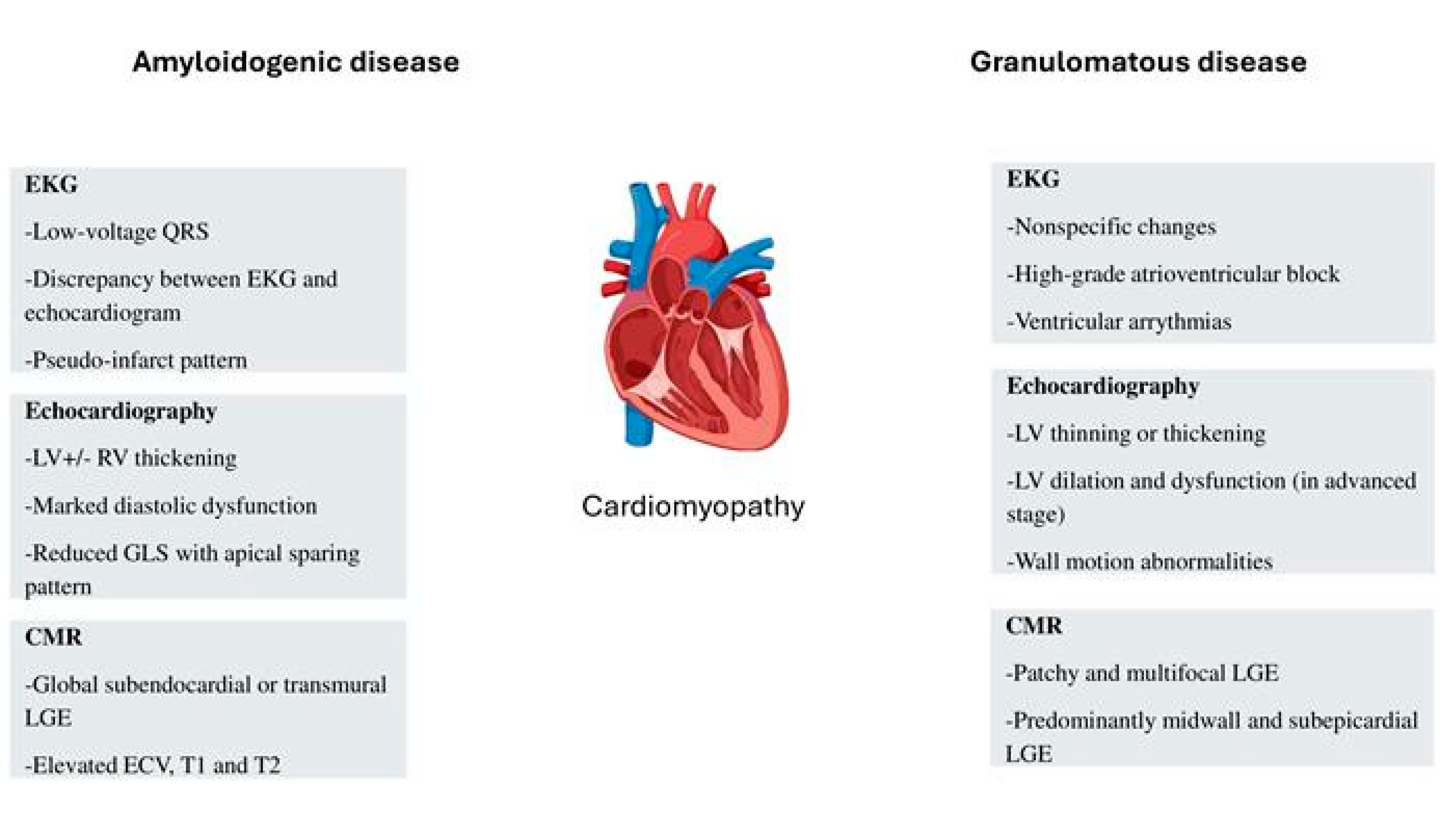

Clinical Characteristics in CA

Clinical Characteristics in CS

Echocardiographic Features in CA

Echocardiographic Features in CS

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in CA

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in CS

Nuclear Imaging with Bone-Avid Tracers

Positron Emission Tomography

Disease-Modifying Treatments

Therapies in ATTR

Therapies in AL

Therapies in CS

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masri A, Bukhari S, Eisele YS, Soman P. Molecular Imaging of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Nucl Med. 2020, 61, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari S, Khan SZ, Ghoweba M, Khan B, Bashir Z. Arrhythmias and Device Therapies in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir Z, Younus A, Dhillon S, Kasi A, Bukhari S. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cardiac amyloidosis. J Investig Med. 2024, 72, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S. Cardiac amyloidosis: state-of-the-art review. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2023, 20, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari S, Oliveros E, Parekh H, Farmakis D. Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari SB, Nieves A, Eisele R, Follansbee Y, Soman WP. Clinical Predictors of positive 99mTc-99m pyrophosphate scan in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure. J Nucl Med. 2020, 61, 659. [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum J, Jacobson DR, Tagoe C, Alexander A, Kitzman DW, Greenberg B, Thaneemit-Chen S, Lavori P. Transthyretin V122I in African Americans with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 47, 1724–1725.

- Bukhari SF, Brownell S, Eisele A, Soman YS. Race-specific phenotypic and genotypic comparison of patients with Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021, 77, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddington-Cruz M, Wixner J, Amass L, Kiszko J, Chapman D, Ando Y; THAOS investigators. Characteristics of Patients with Late- vs. Early-Onset Val30Met Transthyretin Amyloidosis from the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey (THAOS). Neurol Ther. 2021, 10, 753–766.

- Hewitt K, Starr N, Togher Z, Sulong S, Morris JP, Alexander M, Coyne M, Murphy K, Giblin G, Murphy SM, et al. Spectrum of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis due to T60A(p.Thr80Ala) variant in an Irish Amyloidosis Network. Open Heart. 2024, 11, e002906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hamed R, Bazarbachi AH, Bazarbachi A, Malard F, Harousseau JL, Mohty M. Comprehensive Review of AL amyloidosis: some practical recommendations. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palladini G, Milani P. Diagnosis and Treatment of AL Amyloidosis. Drugs. 2023, 83, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachtenberg BH, Hare JM. Inflammatory Cardiomyopathic Syndromes. Circ Res. 2017, 121, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, Rossman MD, Barnard J, Frederick M, Terrin ML, Weinberger SE, Moller DR, McLennan G, et al; ACCESS Research Group A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004, 170, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai K, Tachibana T, Takemura T, Matsui Y, Kitaichi M, Kawabata Y. Pathological studies on sarcoidosis autopsy. I. Epidemiological features of 320 cases in Japan. Acta Pathol Jpn.

- Birnie DH, Nery PB, Ha AC, Beanlands RS. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016, 68, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly JP, Hanna M, Sperry BW, Seitz WH Jr. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Potential Early, Red-Flag Sign of Amyloidosis. J Hand Surg Am. 2019, 44, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi L, Trimarchi G, Liotta P, Restelli D, Licordari R, Carciotto G, Francesco C, Crea P, Dattilo G, Micari A, et al. Electrocardiographic Patterns and Arrhythmias in Cardiac Amyloidosis: From Diagnosis to Therapeutic Management-A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani A, De Michieli L, Porcari A, Licchelli L, Sinigiani G, Tini G, Zampieri M, Sessarego E, Argirò A, Fumagalli C, et al. Low QRS Voltages in Cardiac Amyloidosis: Clinical Correlates and Prognostic Value. JACC CardioOncol. 2022, 4, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari SM, Shpilsky S, Nieves D, Bashir R, Soman Z. Development and validation of a diagnostic model and scoring system for transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. J Investig Med. 2021, 69, 1071–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari SM, Shpilsky S, Nieves D, Soman R. Amyloidosis prediction score: a clinical model for diagnosing Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Card Fail. 2020, 26, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari S, Barakat AF, Eisele YS, Nieves R, Jain S, Saba S, Follansbee WP, Brownell A, Soman P. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolic Risk in Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021, 143, 1335–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari S, Khan SZ, Bashir Z. Atrial Fibrillation, Thromboembolic Risk, and Anticoagulation in Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Review. J Card Fail. 2023, 29, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari S, Khan B. Prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias and role of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in cardiac amyloidosis. J Cardiol. 2023, 81, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari S, Kasi A, Khan B. Bradyarrhythmias in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Role of Pacemaker. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Michieli L, Cipriani A, Iliceto S, Dispenzieri A, Jaffe AS. Cardiac Troponin in Patients With Light Chain and Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis: JACC: CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2024, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willy K, Dechering DG, Reinke F, Bögeholz N, Frommeyer G, Eckardt L. The ECG in sarcoidosis - a marker of cardiac involvement? Current evidence and clinical implications. J Cardiol. 2021, 77, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts WC, McAllister HA Jr, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med. 1977, 63, 86–108.

- Nordenswan HK, Lehtonen J, Ekström K, Kandolin R, Simonen P, Mäyränpää M, Vihinen T, Miettinen H, Kaikkonen K, Haataja P, et al. Outcome of Cardiac Sarcoidosis Presenting With High-Grade Atrioventricular Block. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018, 11, e006145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy SAM, Chetrit M, Jankowski M, Desai M, Falk RH, Weiner RB, Klein AL, Phelan D, Grogan M: Practical Points for Echocardiography in Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2022, 35, A31–A40. [CrossRef]

- Dorbala S, Ando Y, Bokhari S, Dispenzieri A, Falk RH, Ferrari VA, Fontana M, Gheysens O, Gillmore JD, Glaudemans A et al: ASNC/AHA/ASE/EANM/HFSA/ISA/SCMR/SNMMI Expert Consensus Recommendations for Multimodality Imaging in Cardiac Amyloidosis: Part 2 of 2-Diagnostic Criteria and Appropriate Utilization. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging.

- Liang S, Liu Z, Li Q, He W, Huang H: Advance of echocardiography in cardiac amyloidosis. Heart Fail Rev, 1345.

- Bashir Z, Chen EW, Tori K, Ghosalkar D, Aurigemma GP, Dickey JB, Haines P: Insight into different phenotypic presentations of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2023, 79, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Minamisawa M, Inciardi RM, Claggett B, Cuddy SAM, Quarta CC, Shah AM, Dorbala S, Falk RH, Matsushita K, Kitzman DW et al: Left atrial structure and function of the amyloidogenic V122I transthyretin variant in elderly African Americans. Eur J Heart Fail 2021, 23, 1290–1295. [CrossRef]

- Monte IP, Faro DC, Trimarchi G, de Gaetano F, Campisi M, Losi V, Teresi L, Di Bella G, Tamburino C, de Gregorio C: Left Atrial Strain Imaging by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography: The Supportive Diagnostic Value in Cardiac Amyloidosis and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10.

- Bravo PE, Fujikura K, Kijewski MF, Jerosch-Herold M, Jacob S, El-Sady MS, Sticka W, Dubey S, Belanger A, Park MA et al: Relative Apical Sparing of Myocardial Longitudinal Strain Is Explained by Regional Differences in Total Amyloid Mass Rather Than the Proportion of Amyloid Deposits. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, 1165–1173.

- Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, Cooper JM, Culver DA, Duvernoy CS, Judson MA, Kron J, Mehta D, Cosedis Nielsen J, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014, 11, 1305–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh G, Laffin LJ, Beshai JF, Maffessanti F, Bonham CA, Patel AV, Yu Z, Addetia K, Mor-Avi V, Moss JD, et al. Prognosis of Myocardial Damage in Sarcoidosis Patients With Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: Risk Stratification Using Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016, 9, e003738. [Google Scholar]

- Nabeta T, Kitai T, Naruse Y, Taniguchi T, Yoshioka K, Tanaka H, Okumura T, Sato S, Baba Y, Kida K, et al. Risk stratification of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis: the ILLUMINATE-CS registry. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 3450–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanizawa K, Handa T, Nagai S, Yokomatsu T, Ueda S, Ikezoe K, Ogino S, Hirai T, Izumi T. Basal interventricular septum thinning and long-term left ventricular function in patients with sarcoidosis. Respir Investig. 2022, 60, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef G, Beanlands RS, Birnie DH, Nery PB. Cardiac sarcoidosis: applications of imaging in diagnosis and directing treatment. Heart. 2011, 97, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce E, Ninaber MK, Katsanos S, Debonnaire P, Kamperidis V, Bax JJ, Taube C, Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N. Subclinical left ventricular dysfunction by echocardiographic speckle-tracking strain analysis relates to outcome in sarcoidosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckberg G, Hoffman JI, Mahajan A, Saleh S, Coghlan C. Cardiac mechanics revisited: the relationship of cardiac architecture to ventricular function. Circulation. 2008, 118, 2571–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusano K, Ishibashi K, Noda T, Nakajima K, Nakasuka K, Terasaki S, Hattori Y, Nagayama T, Mori K, Takaya Y, et al. Prognosis and Outcomes of Clinically Diagnosed Cardiac Sarcoidosis Without Positive Endomyocardial Biopsy Findings. JACC Asia. 2021, 1, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperry BW, Ibrahim A, Negishi K, Negishi T, Patel P, Popović ZB, Culver D, Brunken R, Marwick TH, Tamarappoo B. Incremental Prognostic Value of Global Longitudinal Strain and 18F-Fludeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography in Patients With Systemic Sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2017, 119, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albakaa NK, Sato K, Iida N, Yamamoto M, Machino-Ohtsuka T, Ishizu T, Ieda M. Association between right ventricular longitudinal strain and cardiovascular events in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Cardiol. 2022, 80, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir Z, Musharraf M, Azam R, Bukhari S. Imaging modalities in cardiac amyloidosis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthals D, Chatzantonis G, Bietenbeck M, Meier C, Stalling P, Yilmaz A: CMR-based T1-mapping offers superior diagnostic value compared to longitudinal strain-based assessment of relative apical sparing in cardiac amyloidosis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 15521. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Li X, Feng J, Shen KN, Tian Z, Sun J, Mao YY, Cao J, Jin ZY, Li J et al: The prognostic value of T1 mapping and late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients with light chain amyloidosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2018, 20, 2. [CrossRef]

- Fontana M, Pica S, Reant P, Abdel-Gadir A, Treibel TA, Banypersad SM, Maestrini V, Barcella W, Rosmini S, Bulluck H et al: Prognostic Value of Late Gadolinium Enhancement Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circulation 2015, 132, 1570–1579. [CrossRef]

- Karamitsos TD, Piechnik SK, Banypersad SM, Fontana M, Ntusi NB, Ferreira VM, Whelan CJ, Myerson SG, Robson MD, Hawkins PN et al: Noncontrast T1 mapping for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013, 6, 488–497. [CrossRef]

- Banypersad SM, Fontana M, Maestrini V, Sado DM, Captur G, Petrie A, Piechnik SK, Whelan CJ, Herrey AS, Gillmore JD et al: T1 mapping and survival in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 244–251. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Naharro A, Kotecha T, Norrington K, Boldrini M, Rezk T, Quarta C, Treibel TA, Whelan CJ, Knight DS, Kellman P et al: Native T1 and Extracellular Volume in Transthyretin Amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, 810–819.

- Pan JA, Kerwin MJ, Salerno M: Native T1 Mapping, Extracellular Volume Mapping, and Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020, 13, 1299–1310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Naharro A, Abdel-Gadir A, Treibel TA, Zumbo G, Knight DS, Rosmini S, Lane T, Mahmood S, Sachchithanantham S, Whelan CJ et al: CMR-Verified Regression of Cardiac AL Amyloid After Chemotherapy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018, 11, 152–154. [CrossRef]

- Olausson E, Wertz J, Fridman Y, Bering P, Maanja M, Niklasson L, Wong TC, Fukui M, Cavalcante JL, Cater G, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis associates with incident ventricular arrhythmia in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2: 16, 2023.

- Kotecha T, Martinez-Naharro A, Treibel TA, Francis R, Nordin S, Abdel-Gadir A, Knight DS, Zumbo G, Rosmini S, Maestrini V et al: Myocardial Edema and Prognosis in Amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 71, 2919–2931.

- Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, van Geuns RJ, Dassen WR, Gorgels AP, Crijns HJ. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 45, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo L, Han Y, Mui D, Zhang Y, Chahal A, Schaller RD, Frankel DS, Marchlinski FE, Desjardins B, Nazarian S. Diagnostic Specificity of Basal Inferoseptal Triangular Late Gadolinium Enhancement for Identification of Cardiac Sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019, 12, 2574–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe E, Kimura F, Nakajima T, Hiroe M, Kasai Y, Nagata M, Kawana M, Hagiwara N. Late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac sarcoidosis: characteristic magnetic resonance findings and relationship with left ventricular function. J Thorac Imaging. 2013, 28, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulten E, Agarwal V, Cahill M, Cole G, Vita T, Parrish S, Bittencourt MS, Murthy VL, Kwong R, Di Carli MF, Blankstein R. Presence of Late Gadolinium Enhancement by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Among Patients With Suspected Cardiac Sarcoidosis Is Associated With Adverse Cardiovascular Prognosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016, 9, e005001. [Google Scholar]

- Crouser ED, Ono C, Tran T, He X, Raman SV. Improved detection of cardiac sarcoidosis using magnetic resonance with myocardial T2 mapping. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014, 189, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano Y, Tachi M, Tani H, Mizuno K, Kobayashi Y, Kumita S. T2-weighted cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of edema in myocardial diseases. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012, 2012, 194069. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari S, Bashir Z. Diagnostic Modalities in the Detection of Cardiac Amyloidosis. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmore JD, Maurer MS, Falk RH, Merlini G, Damy T, Dispenzieri A, Wechalekar AD, Berk JL, Quarta CC, Grogan M, et al. Nonbiopsy Diagnosis of Cardiac Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Circulation. 2016, 133, 2404–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini E, Guidalotti PL, Salvi F, Cooke RM, Pettinato C, Riva L, Leone O, Farsad M, Ciliberti P, Bacchi-Reggiani L, et al. Noninvasive etiologic diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis using 99mTc-3,3-diphosphono-1,2-propanodicarboxylic acid scintigraphy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 46, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari S, Masri A, Ahmad S, Eisele YS, Brownell A, Soman P. Discrepant Tc-99m PYP Planar grade and H/CL ratio: Which correlates better with diffuse tracer uptake on SPECT? Journal of Nuclear Medicine May 2020, 61, 1633. [Google Scholar]

- Masri A, Bukhari S, Ahmad S, Nieves R, Eisele YS, Follansbee W, Brownell A, Wong TC, Schelbert E, Soman P. Efficient 1-Hour Technetium-99 m Pyrophosphate Imaging Protocol for the Diagnosis of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020, 13, e010249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chareonthaitawee P, Beanlands RS, Chen W, Dorbala S, Miller EJ, Murthy VL, Birnie DH, Chen ES, Cooper LT, Tung RH, et al. Joint SNMMI-ASNC expert consensus document on the role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in cardiac sarcoid detection and therapy monitoring. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1741–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran S, Stewart GC, Lakdawala NK, Padera RF, Zhou W, Desai AS, Givertz MM, Mehra MR, Kwong RY, Hedgire SS, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Advanced Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019, 12, e008975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankstein R, Waller AH. Evaluation of Known or Suspected Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016, 9, e000867. [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001, 411, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O'Riordan WD, Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk JL, et al. Patisiran, an RNAi Therapeutic, for Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooke ST, Wang S, Vickers TA, Shen W, Liang XH. Cellular uptake and trafficking of antisense oligonucleotides. Nat Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson MD, Waddington-Cruz M, Berk JL, Polydefkis M, Dyck PJ, Wang AK, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Barroso FA, Merlini G, Obici L, et al. Inotersen Treatment for Patients with Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz M, Kristen AV, Grogan M, Witteles R, Damy T, et al; ATTR-ACT Study Investigators Tafamidis Treatment for Patients with Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, Sekijima Y, Zeldenrust SR, Yamashita T, Heneghan MA, Gorevic PD, Litchy WJ, Wiesman JF, et al; Diflunisal Trial Consortium Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013, 310, 2658–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim M, Saint Croix GR, Lacy S, Fattouh M, Barillas-Lara MI, Behrooz L, Mechanic O. The use of diflunisal for transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: a review. Heart Fail Rev. 2022, 27, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekijima Y, Tojo K, Morita H, Koyama J, Ikeda S. Safety and efficacy of long-term diflunisal administration in hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2015, 22, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasib Sidiqi M, Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis diagnosis and treatment algorithm 2021. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchtar E, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Kumar SK, Buadi FK, Leung N, Lacy MQ, Dingli D, Ailawadhi S, Bergsagel PL, et al. Treatment of AL Amyloidosis: Mayo Stratification of Myeloma and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) Consensus Statement 2020 Update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021, 96, 1546–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlini G, Lousada I, Ando Y, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Grogan M, Maurer MS, Sanchorawala V, Wechalekar A, Palladini G, et al. Rationale, application and clinical qualification for NT-proBNP as a surrogate end point in pivotal clinical trials in patients with AL amyloidosis. Leukemia. 2016, 30, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman RP, Valeyre D, Korsten P, Mathioudakis AG, Wuyts WA, Wells A, Rottoli P, Nunes H, Lower EE, Judson MA, et al. ERS clinical practice guidelines on treatment of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2021, 58, 2004079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada H, Soejima K. Management of Arrhythmias Associated with Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Korean Circ J. 2019, 49, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker MC, Sheth K, Witteles R, Genovese MC, Shoor S, Simard JF. TNF-alpha inhibition for the treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 50, 546–552, Erratum in: Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:1390.. [Google Scholar]

| Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis | Immunoglobulin light-chain cardiac amyloidosis | Cardiac sarcoidosis |

|---|---|---|

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Carpal tunnel syndrome | Mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes |

| Lumbar spinal stenosis | Lumbar spinal stenosis | Subcutaneous lymph nodes |

| Non-traumatic biceps tendon rupture | Non-traumatic biceps tendon rupture | Deep lymph nodes |

| Hip/knee replacement | Hip/knee replacement | Liver |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Peripheral neuropathy | Pulmonary |

| Orthostatic hypotension | Orthostatic hypotension | Spleen |

| Autonomic dysfunction | Autonomic dysfunction | Bone |

| Gastroparesis | Muscle | |

| Macroglossia | Skin | |

| Nephrotic syndrome | ||

| Hepatic amyloidosis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).