Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A discussion of the dataset required for ANN training through seeding performance experiments;

- An explanation of using backpropagation neural network (BPNN) to establish a predictive model of seeding performance from the input physical properties of seeds (geometric mean diameter, sphericity, thousand-grain weight, and kernel density), operational parameters (vacuum pressure and drum rotational speed), and structural parameters (suction hole diameter), producing seeding performance indices (missing index and reseeding index);

- A description of optimization method of the combination of the BPNN predictive model and MOPSO algorithm (BPNN-MOPSO) to search for optimal device parameters, with the lowest missing and reseeding indexes as the optimization objectives.

2. Materials and Methods

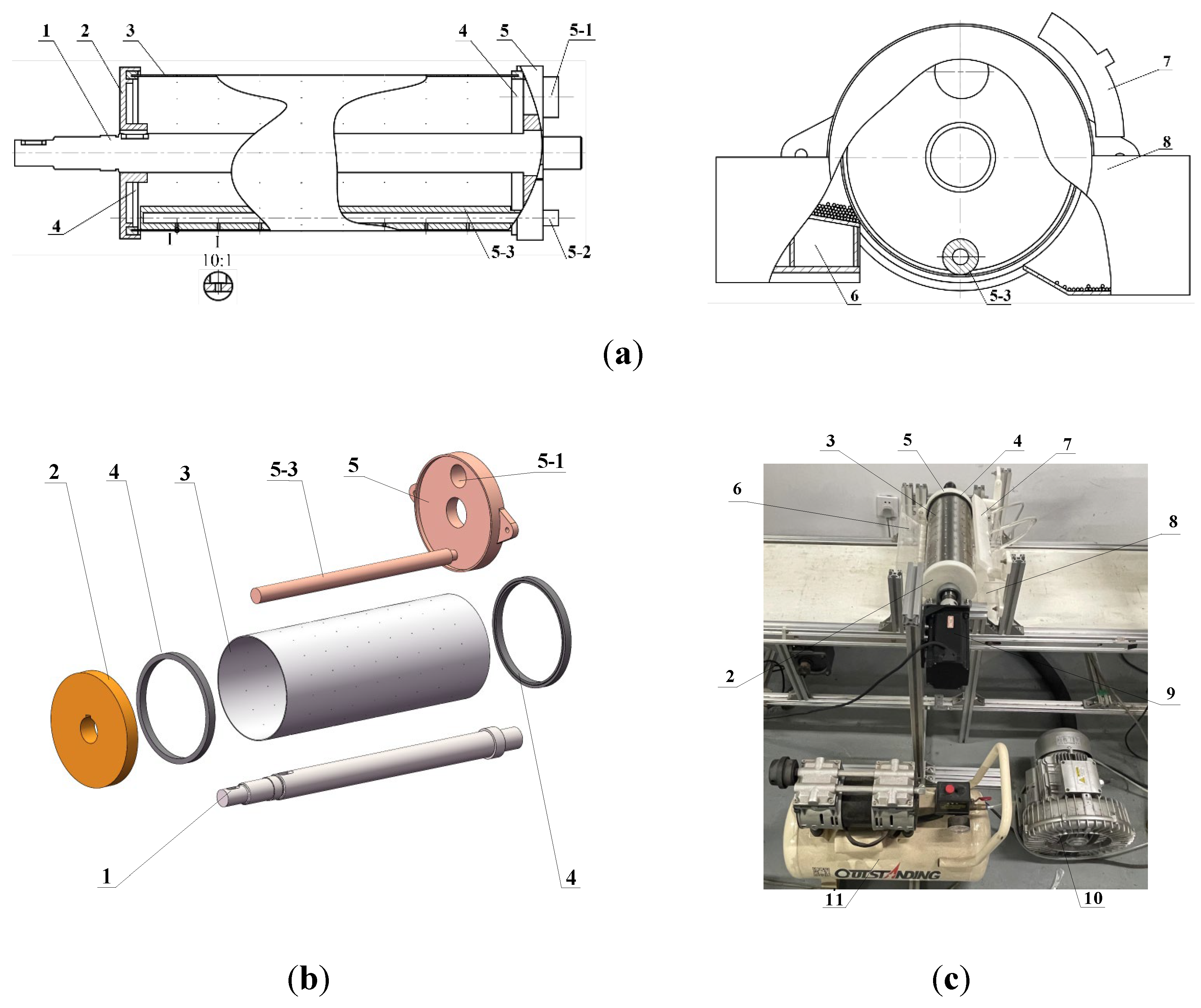

2.1. Overall Structure and Working Principle

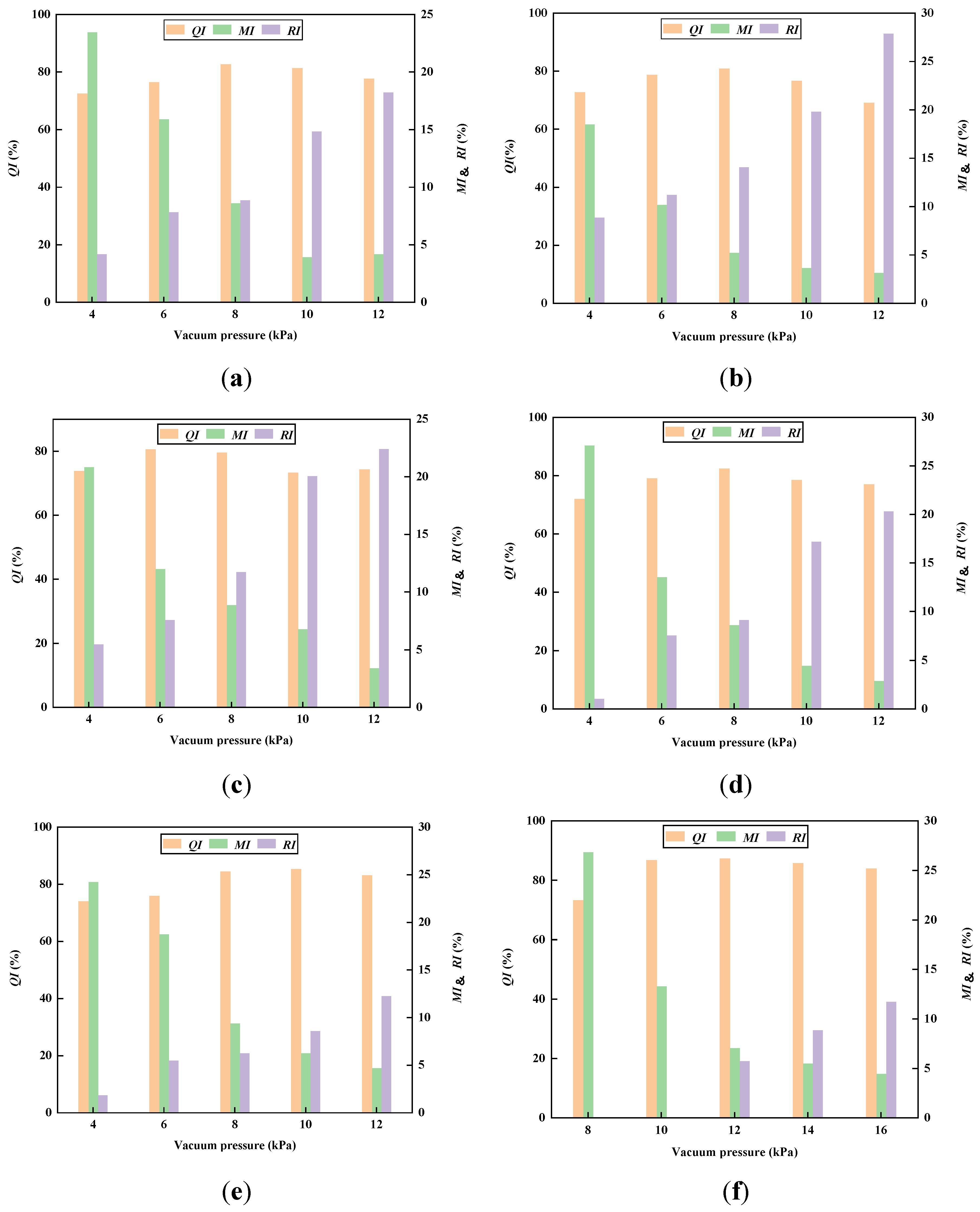

2.2. Influencing Factors and Seeding Performance Indices

2.3. Value Range of Factors

2.4. Orthogonal Experiments

2.5. Predictive Model Using Backpropagation Neural Network

2.5.1. Seeding Performance Dataset

2.5.2. Backpropagation Neural Network

2.5.3. Evaluation Indices for Network Performance

2.5.4. Establishment of BPNN Predictive model

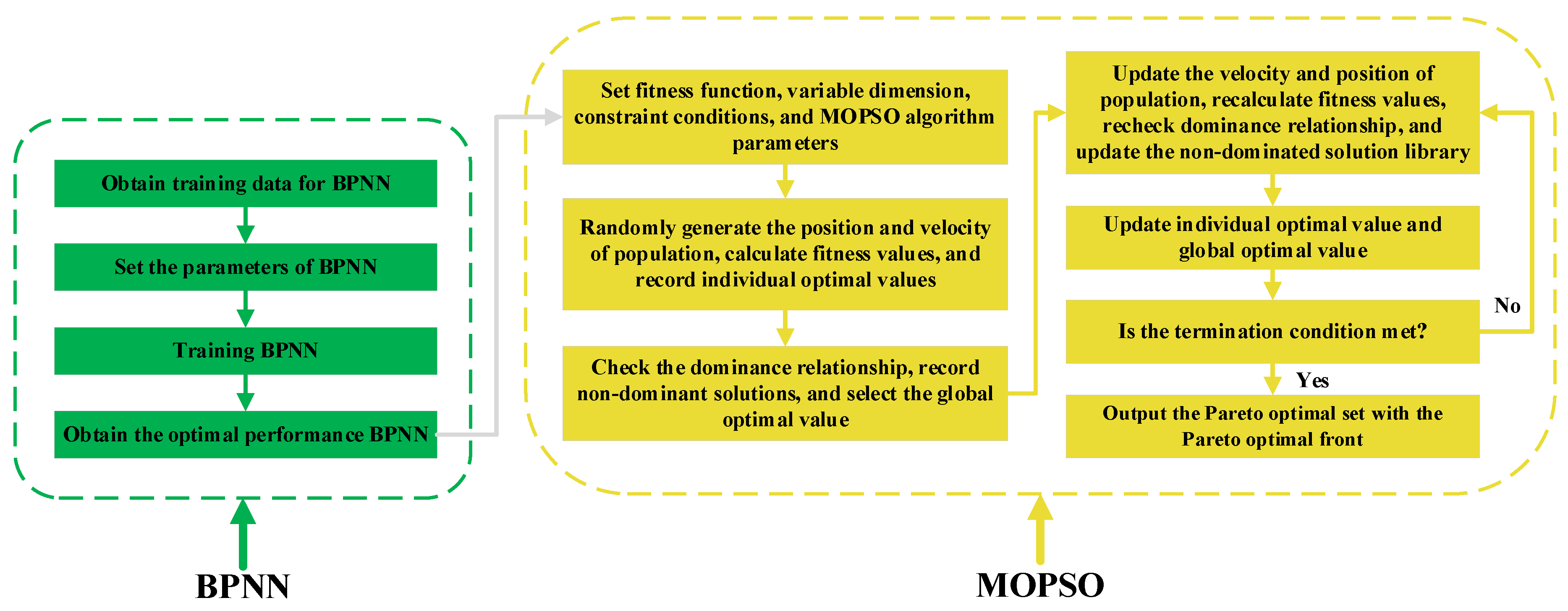

2.6. BPNN-MOPSO Parameter Optimization of the Seed Metering Device

2.6.1. Principle and Flow of the MOPSO Algorithm

- Define a fitness function based on optimization objectives, determine the dimensions and constraints for each input variable, and set MOPSO algorithm parameters;

- Randomly generate position and velocity vectors for the initial population; then, calculate and record the fitness value of each particle as the individual optimal value;

- Based on Pareto dominance, check the dominance relationship of all particles, record all non-dominated solutions, and select one as the global optimal value;

- Update the velocity and position vectors of the population, recalculate each particle’s fitness value, recheck the domination relationship, and update the non-domination solution library;

- Update individual and global optimal values;

- Check whether the maximum number of iterations is reached. If so, the algorithm terminates; otherwise, return to Step 4;

- Output the Pareto optimal set and the Pareto optimal front.

2.6.2. Settings of the MOPSO Algorithm Parameters

2.6.3. Mathematical Model for the Multi-objective Optimization Problem

2.6.4. Scoring Method for Solutions

2.6.5. Process of BPNN-MOPSO

3. Results and Discussion

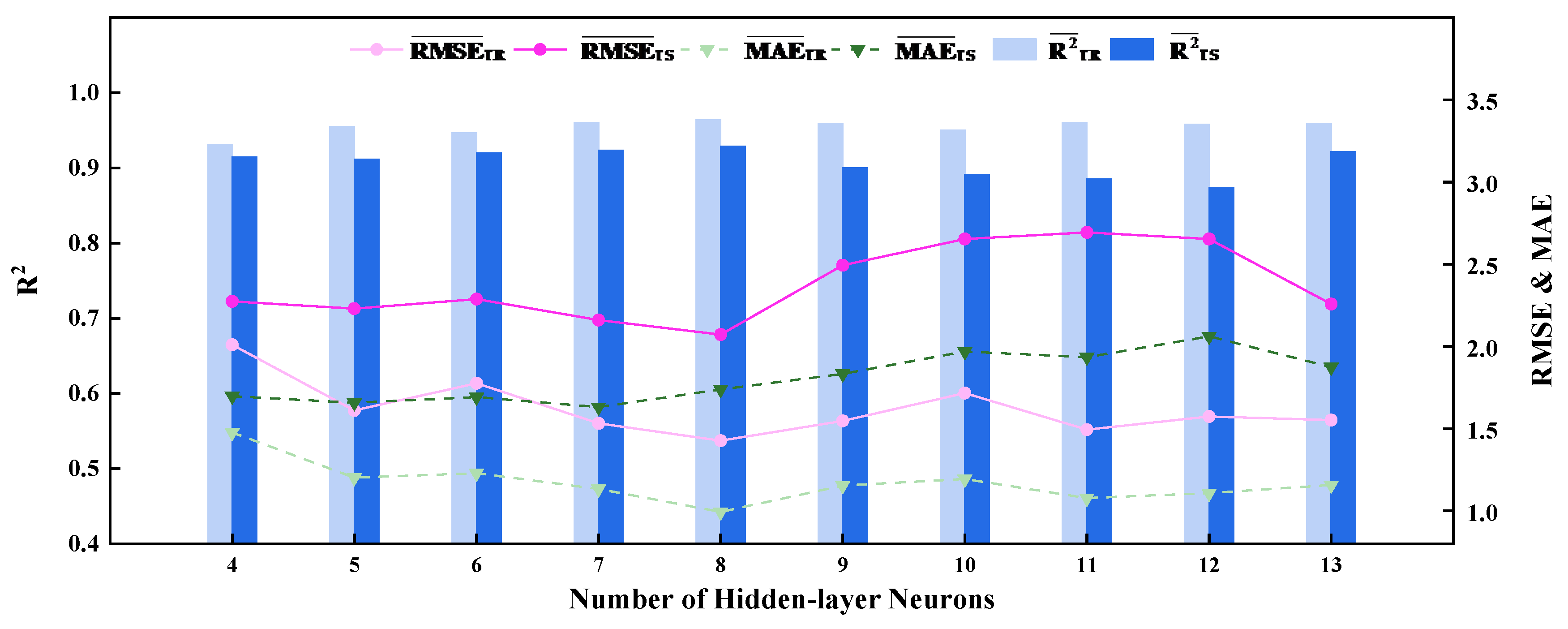

3.1. Determination of the Number of Hidden-Layer Neurons

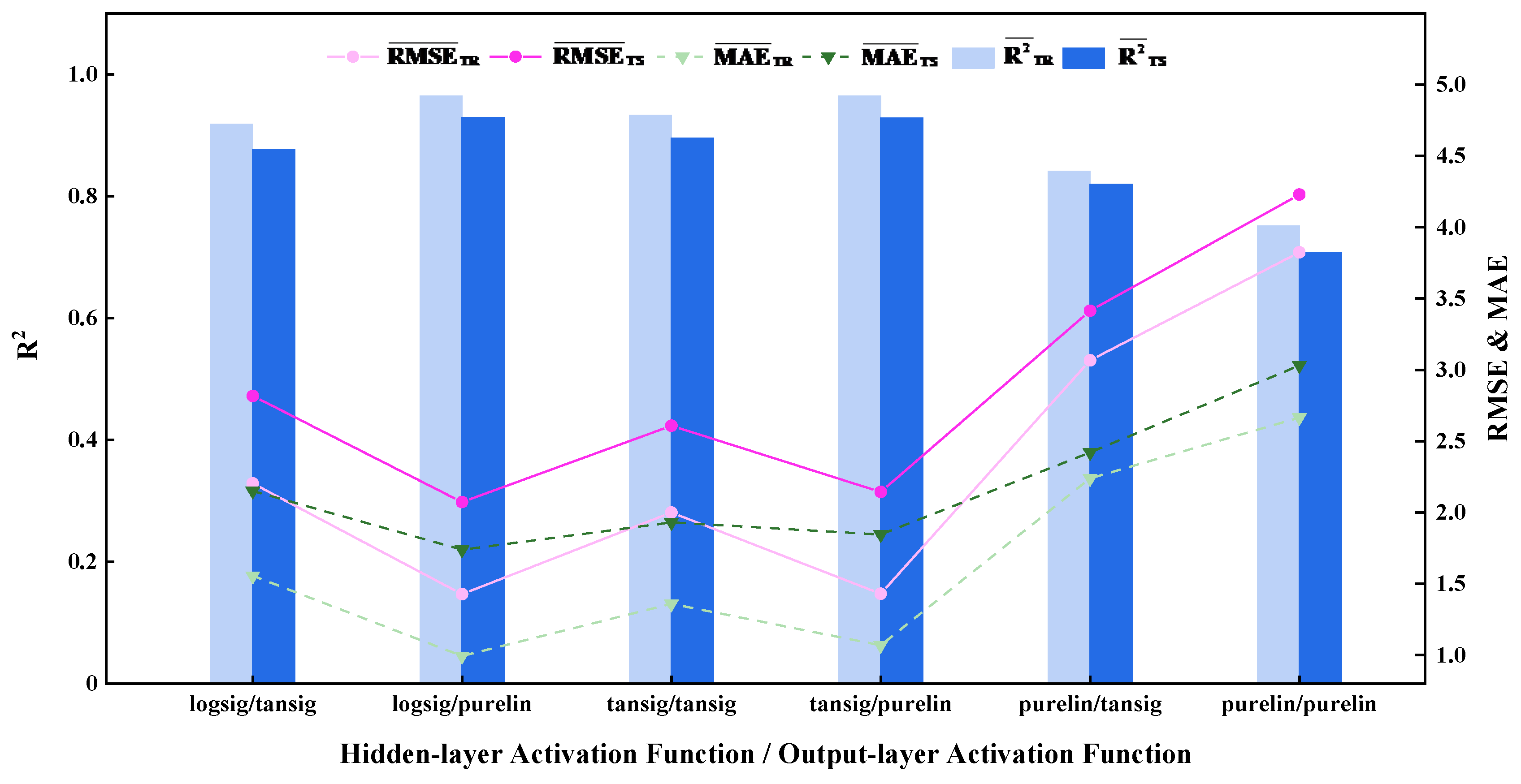

3.2. Determination of the Activation Functions for the Hidden and Output Layers

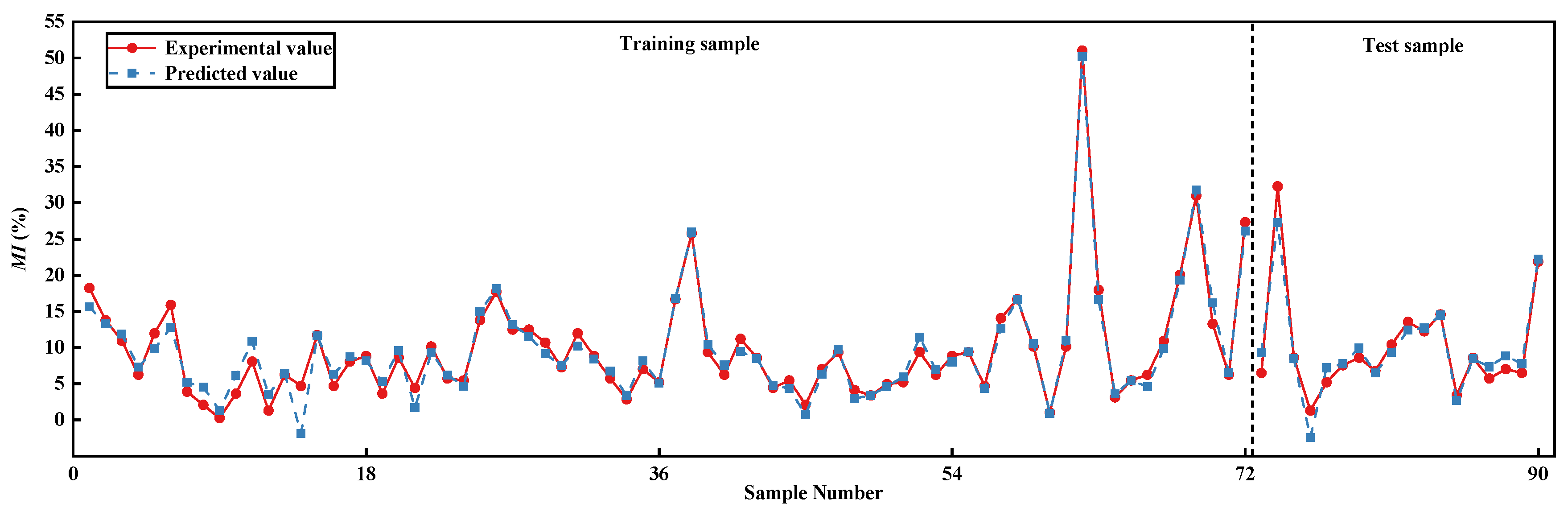

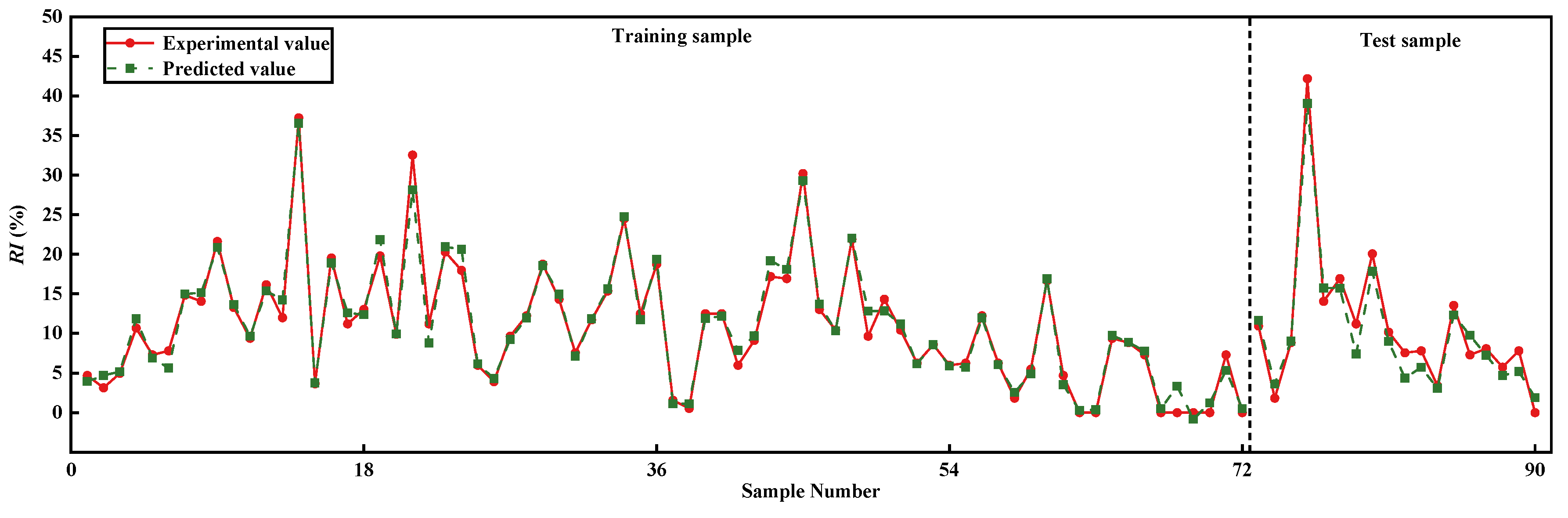

3.3. Determination of the Optimal BPNN Performance

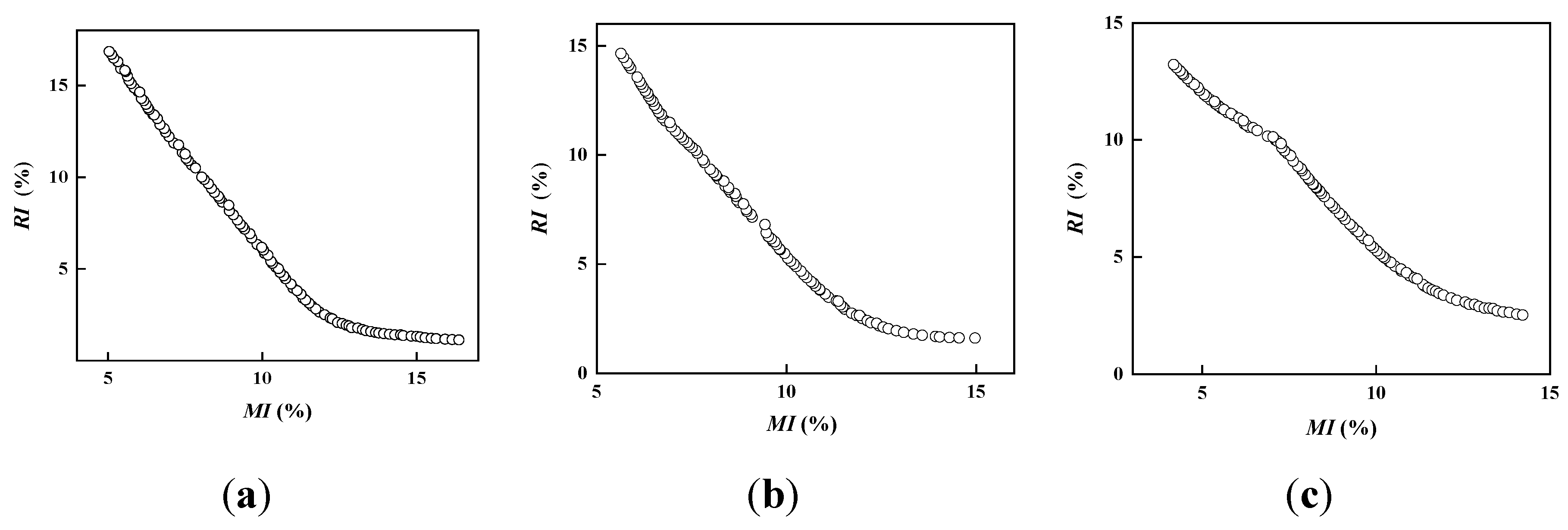

3.4. Verification of Optimization Capability of BPNN-MOPSO

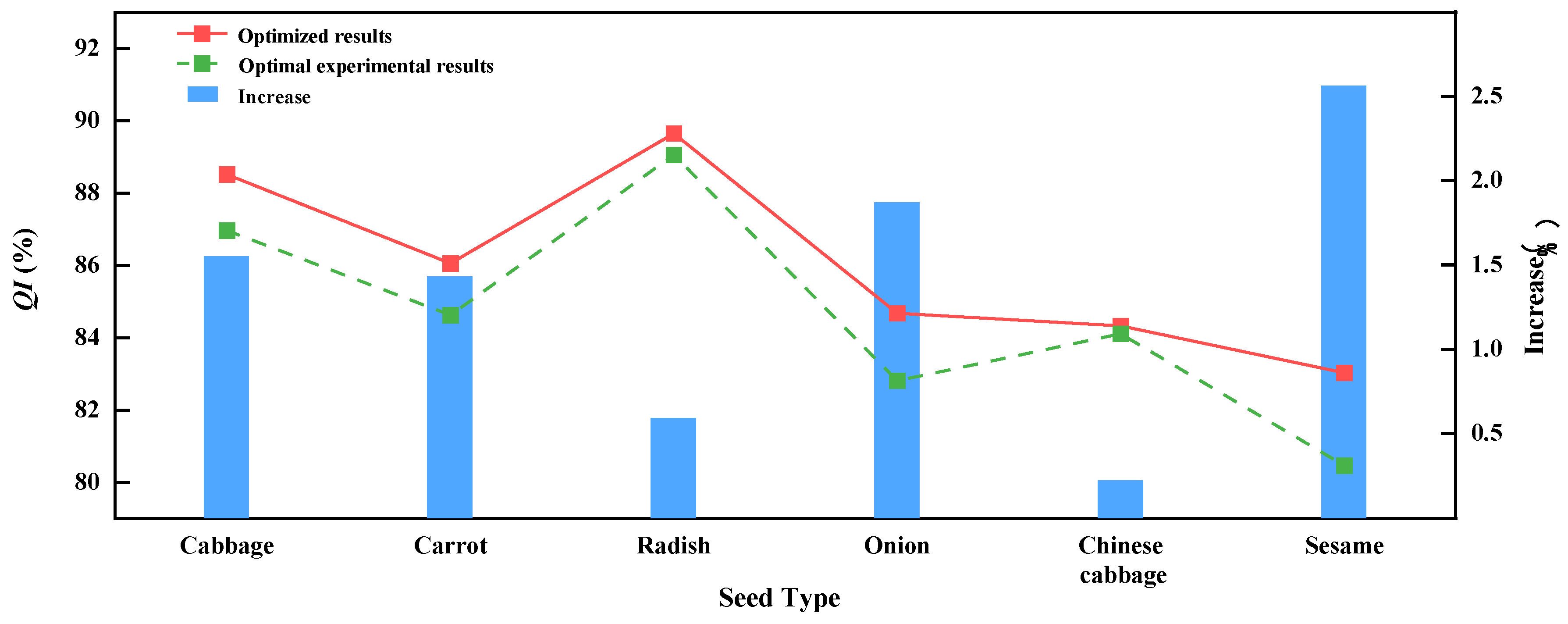

3.5. BPNN-MOPSO Optimization Results and Experimental Verification

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.T.; Li, T.H.; Wang, H.F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Design and parameter optimization of pneumatic cylinder ridge three-row close-planting seed-metering device for soybean. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2018, 34, 16–24.

- He, X.; Cao, X.M.; Peng, Z.; Wan, Y.K.; Lin, J.J.; Zang, Y.; Zhang, G.Z. DEM-CFD Coupling Simulation and Optimization of Rice Seed Particles Seeding a Hill in Double Cavity Pneumatic Seed Metering Device. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 224, 109075. [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zheng, X.S.; Wang, D.W.; Hou, J.L.; Zhao, Z. Design and Experiment of Precision Seed Metering Device with Pneumatic Assisted Seed-filling for Peanut. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2024, 55, 64–74.

- Liao, Y.T.; Liu, J.C.; Liao, Q.X.; Zheng, J.; Li, T.; Jiang, S. Design and Test of Positive and Negative Pressure Combination Roller Type Precision Seed-metering Device for Rapeseed. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2024, 55, 63–76.

- Karayel, D.; Güngör, O.; Šarauskis, E. Estimation of Optimum Vacuum Pressure of Air-Suction Seed-Metering Device of Precision Seeders Using Artificial Neural Network Models. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1600. [CrossRef]

- Abdolahzare, Z.; Mehdizadeh, S.A. Nonlinear Mathematical Modeling of Seed Spacing Uniformity of a Pneumatic Planter Using Genetic Programming and Image Processing. Neural Comput & Applic 2018, 29, 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Qin, N.; Wang, K.Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, D.W.; Qiao, J.Y. Effect of Mechanical Compaction on Soybean Yield Based on Machine Learning. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery 2023, 54, 139–147.

- Chen, S.M.; Li, X.L.; Yang, Q.L.; Wu, L.F.; Xiong, K.; Liu, X.G. Estimation of reference evapotranspiration in shading facility using machine learning. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2022, 38, 108–116.

- Zhang, Y.F.; Pan, Z.Q.; Chen, D.J. Estimation of Cropland Nitrogen Runoff Loss Loads in the Yangtze River Basin Based on the Machine Learning Approaches. Environmental Science 2023, 44, 3913–3922. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.W.; Yang, S.H.; Liu, Z.Y.; Xu, J.Z.; Pang, Q.Q.; Using Machine Learning to Predict Water level in the Drainage Sluice Stations Following Rainfalls. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage 2022, 41, 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Na, X.Y.; Zhao, C.Y.; Sun, S.M.; Zhang, Z.G. Performance test and forecast analysis for air suction seed metering device. Journal of Hunan Agricultural University (Natural Sciences) 2015, 41, 440–442.

- Anantachar, M.; Kumar, P.G.V.; Guruswamy, T. Neural Network Prediction of Performance Parameters of an Inclined Plate Seed Metering Device and Its Reverse Mapping for the Determination of Optimum Design and Operational Parameters. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2010, 72, 87-98. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.M.; Pareek, C.M.; Machavaram, R. Optimizing the Aeration Performance of a Perforated Pooled Circular Stepped Cascade Aerator Using Hybrid ANN-PSO Technique. Information Processing in Agriculture 2022, 9, 533-546. [CrossRef]

- Pareek, C.M.; Tewari, V.K.; Machavaram, R. Multi-Objective Optimization of Seeding Performance of a Pneumatic Precision Seed Metering Device Using Integrated ANN-MOPSO Approach. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 117, 105559. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Study on WC-10Co-4Cr Coating Prediction Model and Multi-objective Optimization by High Velocity Oxy-Fuel spraying Based on Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2023.

- Ke, S.D. Research on virtual prototype of pneumatic drum seed metering device based on seed characteristics. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou, China, 2022.

- Du, Y.; Li, X.H.; Cao, L.M.; Yang, J. One-Step Solvothermal Synthesis of MoS2@Ti Cathode for Electrochemical Reduction of Hg2+ and Predicting BP Neural Network Model. Separation and Purification Technology 2024, 331, 125654. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zeng, X.G.; Kou, H.Q.; Chen, H.Y. A Kind of Numerical Model Combined with Genetic Algorithm and Back Propagation Neural Network for Creep-Fatigue Life Prediction and Optimization of Double-Layered Annulus Metal Hydride Reactor and Verification of ASME-NH Code. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 1251–1263. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F.; He, X.; Huang, H.Y.; Yang, J.X.; Dai, J.J.; Shi, X.C.; Xue, F.J.; Rabczuk, T. Predicting Gas Flow Rate in Fractured Shale Reservoirs Using Discrete Fracture Model and GA-BP Neural Network Method. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements 2024, 159, 315–330. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.W.; Huang, Y.Q.; Li, Z.Y.; Li, J.R.; Jiang, C.; Chen, Y.R. Performance Prediction and Optimization of Lateral Exhaust Hood Based on Back Propagation Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 113, 105696. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, X.S.; Pu, J.; Jiao, S.S. Kinetic Analysis and Back Propagation Neural Network Model for Shelf-Life Estimation of Stabilized Rice Bran. Journal of Food Engineering 2024, 380, 112168. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.H.; Wang, S.C.; Liu, G. Creep–Fatigue Life Prediction of a Titanium Alloy Deep-Sea Submersible Using a Continuum Damage Mechanics-Informed BP Neural Network Model. Ocean Engineering 2024, 311, 118826. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H. Prediction of Seawater Desalination Reverse Osmosis Membrane Contamination Based on BP Neural Network Model. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2023.

- Lyu, B.N. Research on design and performance prediction of composite recycled powder mortar based on artificial neural network. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2023.

- Yao, S.C.; Li, D.W. Neural network and deep learning: simulation and realization based on MATLAB, 1st ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 118.

- Fan, X.Y.; Lyu, S.T.; Xia, C.D.; Ge, D.D.; Liu, C.C.; Lu, W.W. Strength Prediction of Asphalt Mixture under Interactive Conditions Based on BPNN and SVM. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024, 21, e03489. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Kuang, C.W.; Chen, Y.X. Prediction Model of Soil Moisture in Hainan Island Based on Meteorological Factors. Chinese Journal of Tropical Agriculture 2023, 43, 84-89.

- Yao, X.W.; Zhang, L.Y.; Xu, K.L.; Qi, Y. Study on neural network-based prediction model for biomass ash softening temperature. Journal of Safety and Environment 2024, 24, 3801–3808.

- Li, A.L.; Zhao, Y.M.; Cui, G.M.; Study on Temperature Prediction Model of Blast Furnace Hot Metal Based on Data Preprocessing and Intelligent Optimization. FOUNDRY TECHNOLOGY 2015, 36, 450–454.

- Lin, X.Z.; Wang, H.; Guo, L.L.; Yan, D.M.; Li, L.J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J. Prediction Model of Laser 3D Projection Galvanometer Deflection Voltage Based on PROA-BP. ACTA PHOTONICA SINICA 2024, 53, 56–68.

- Li, J. Study on reliability evaluation of artillery servo system based on particle swarm optimization algorithm. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Technological University, Xi’an, China, 2023.

- Xu, J.H. Research on ship personnel evacuation time prediction model based on neural network. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Ocean University, Dalian, China, 2024.

- Wang, Y.J. Research on grinding roughness value prediction method based on improved GA-BP. Master’s Thesis, Hebei Normal University of Science & Technology, Qinghuangdao, China, 2024.

| Seed Type | Vacuum Pressure (kPa) | Rotational Speed (rpm) | Hole Diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese cabbage | 6–10 | 10–14 | 0.6–1.0 |

| Carrot | |||

| Sesame | |||

| Onion | |||

| Cabbage | 8–12 | ||

| Radish | 10–14 |

| Factor | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Hole diameter (mm) |

0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| Vacuum pressure (kPa) |

6/8/10 | 8/10/12 | 10/12/14 |

| Rotational speed (rpm) |

10 | 12 | 14 |

| Seed Type | Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese cabbage | 0.6 | 6 | 10 | 18.23 | 4.69 | 77.08 |

| 6 | 14 | 32.29 | 1.82 | 65.89 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 13.80 | 3.13 | 83.07 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 10.94 | 4.95 | 84.11 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 6.51 | 10.94 | 82.55 | ||

| 0.8 | 8 | 10 | 6.25 | 10.68 | 83.07 | |

| 8 | 14 | 11.98 | 7.29 | 80.73 | ||

| 6 | 12 | 15.89 | 7.81 | 76.30 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 8.59 | 8.85 | 82.55 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 3.91 | 14.84 | 81.25 | ||

| 1.0 | 8 | 12 | 2.08 | 14.06 | 83.86 | |

| 10 | 10 | 0.26 | 21.61 | 78.13 | ||

| 6 | 10 | 3.65 | 13.28 | 83.07 | ||

| 6 | 14 | 8.07 | 9.38 | 82.55 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 1.30 | 16.15 | 82.55 |

| Seed Type | Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carrot | 0.6 | 6 | 10 | 8.59 | 9.89 | 81.52 |

| 6 | 14 | 11.72 | 3.65 | 84.63 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 8.07 | 11.20 | 80.73 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 7.55 | 16.93 | 75.52 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 5.73 | 20.31 | 73.96 | ||

| 0.8 | 8 | 10 | 4.69 | 19.53 | 75.78 | |

| 8 | 14 | 8.85 | 13.02 | 78.13 | ||

| 6 | 12 | 10.16 | 11.20 | 78.64 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 5.21 | 14.06 | 80.73 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 3.65 | 19.79 | 76.56 | ||

| 1.0 | 8 | 12 | 4.43 | 32.55 | 63.02 | |

| 10 | 10 | 1.30 | 42.19 | 56.51 | ||

| 6 | 10 | 5.47 | 17.97 | 76.56 | ||

| 6 | 14 | 6.25 | 11.98 | 81.77 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 4.69 | 37.24 | 58.07 |

| Seed Type | Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sesame | 0.6 | 6 | 10 | 13.80 | 5.99 | 80.21 |

| 6 | 14 | 17.71 | 3.91 | 78.39 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 12.50 | 9.64 | 77.86 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 12.50 | 12.24 | 75.26 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 10.68 | 18.75 | 70.57 | ||

| 0.8 | 8 | 10 | 7.29 | 14.32 | 78.39 | |

| 8 | 14 | 10.42 | 10.16 | 79.42 | ||

| 6 | 12 | 11.98 | 7.55 | 80.47 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 8.85 | 11.72 | 79.43 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 6.77 | 20.05 | 73.18 | ||

| 1.0 | 8 | 12 | 5.73 | 15.36 | 78.91 | |

| 10 | 10 | 2.86 | 24.48 | 72.66 | ||

| 6 | 10 | 7.03 | 12.50 | 80.47 | ||

| 6 | 14 | 8.59 | 11.20 | 80.21 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 5.21 | 18.75 | 76.04 |

| Seed Type | Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onion | 0.6 | 6 | 10 | 16.67 | 1.56 | 81.77 |

| 6 | 14 | 25.78 | 0.52 | 73.70 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 14.58 | 3.39 | 82.03 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 12.24 | 7.81 | 79.95 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 9.38 | 12.50 | 78.13 | ||

| 0.8 | 8 | 10 | 6.25 | 12.50 | 81.25 | |

| 8 | 14 | 11.20 | 5.99 | 82.81 | ||

| 6 | 12 | 13.54 | 7.55 | 78.91 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 8.59 | 9.11 | 82.29 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 4.43 | 17.19 | 78.39 | ||

| 1.0 | 8 | 12 | 5.47 | 16.93 | 77.60 | |

| 10 | 10 | 2.08 | 30.21 | 67.71 | ||

| 6 | 10 | 7.03 | 13.02 | 79.95 | ||

| 6 | 14 | 9.38 | 10.42 | 80.21 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 4.17 | 21.88 | 73.96 |

| Seed Type | Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabbage | 0.6 | 12 | 14 | 10.16 | 5.47 | 84.37 |

| 10 | 12 | 9.38 | 6.25 | 84.37 | ||

| 8 | 10 | 14.06 | 6.25 | 79.69 | ||

| 8 | 14 | 16.67 | 1.82 | 81.51 | ||

| 12 | 10 | 8.59 | 7.29 | 84.12 | ||

| 0.8 | 10 | 10 | 5.21 | 10.42 | 84.37 | |

| 10 | 14 | 8.85 | 5.99 | 85.16 | ||

| 8 | 12 | 9.38 | 6.25 | 84.37 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 6.25 | 8.59 | 85.16 | ||

| 12 | 12 | 4.69 | 12.24 | 83.07 | ||

| 1.0 | 8 | 14 | 5.73 | 8.07 | 86.20 | |

| 8 | 10 | 4.95 | 14.32 | 80.73 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 3.39 | 9.64 | 86.97 | ||

| 12 | 14 | 3.39 | 13.54 | 83.07 | ||

| 12 | 10 | 1.04 | 16.67 | 82.29 |

| Seed Type | Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radish | 0.6 | 12 | 12 | 27.34 | 0.00 | 72.66 |

| 10 | 14 | 51.04 | 0.00 | 48.96 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 30.99 | 0.00 | 69.01 | ||

| 14 | 10 | 20.05 | 0.00 | 79.95 | ||

| 14 | 14 | 21.88 | 0.00 | 78.12 | ||

| 0.8 | 12 | 10 | 6.51 | 7.81 | 85.68 | |

| 12 | 14 | 10.16 | 4.69 | 85.15 | ||

| 10 | 12 | 13.28 | 0.00 | 86.72 | ||

| 12 | 12 | 7.03 | 5.73 | 87.24 | ||

| 14 | 12 | 5.47 | 8.85 | 85.68 | ||

| 1.0 | 14 | 14 | 6.25 | 7.29 | 86.46 | |

| 14 | 10 | 3.13 | 9.38 | 87.49 | ||

| 12 | 12 | 6.25 | 7.29 | 86.46 | ||

| 10 | 10 | 10.94 | 0.00 | 89.06 | ||

| 10 | 14 | 17.97 | 0.00 | 82.03 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Population size | 100 |

| Non-dominated solution library size | 100 |

| No. of iterations | 200 |

| Individual learning coefficient | 1.5 |

| Global learning coefficient | 1.5 |

| Number of grids per dimension | 40 |

| Inertia weight | Max: 0.9 |

| Min: 0.4 |

| Seed Type | Geometric Mean Diameter (mm) |

Sphericity (%) |

Thousand-Grain Weight (g) |

Kernel Density (g·cm-3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese cabbage | 1.73±0.11 | 89.27±2.96 | 3.13±0.10 | 0.977±0.026 |

| Carrot | 1.56±0.17 | 46.10±5.19 | 1.84±0.07 | 1.155±0.016 |

| Sesame | 1.71±0.10 | 55.34±2.43 | 3.06±0.07 | 0.930±0.027 |

| Onion | 2.04±0.11 | 68.99±4.69 | 3.28±0.02 | 1.131±0.014 |

| Cabbage | 1.75±0.13 | 86.25±5.73 | 3.64±0.16 | 0.940±0.021 |

| Radish | 2.62±0.19 | 76.25±3.64 | 11.27±0.44 | 1.042±0.014 |

| No. | Geometric Mean Diameter (mm) |

Sphericity (%) |

Thousand-Grain Weight (g) |

Kernel Density (g·cm-3) |

Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) | Rotational Speed (rpm) | Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.73 | 89.27 | 3.13 | 0.977 | 0.6 | 10 | 10 | 6.51 | 10.94 |

| 2 | 1.73 | 89.27 | 3.13 | 0.977 | 0.6 | 6 | 14 | 32.29 | 1.82 |

| 3 | 1.73 | 89.27 | 3.13 | 0.977 | 0.8 | 8 | 12 | 8.59 | 8.85 |

| 4 | 1.56 | 46.10 | 1.84 | 1.155 | 1.0 | 10 | 10 | 1.30 | 42.19 |

| 5 | 1.56 | 46.10 | 1.84 | 1.155 | 0.8 | 8 | 12 | 5.21 | 14.06 |

| 6 | 1.56 | 46.10 | 1.84 | 1.155 | 0.6 | 10 | 14 | 7.55 | 16.93 |

| 7 | 1.71 | 55.34 | 3.06 | 0.930 | 1.0 | 6 | 14 | 8.59 | 11.20 |

| 8 | 1.71 | 55.34 | 3.06 | 0.930 | 0.8 | 10 | 12 | 6.77 | 20.05 |

| 9 | 1.71 | 55.34 | 3.06 | 0.930 | 0.8 | 8 | 14 | 10.42 | 10.16 |

| 10 | 2.04 | 68.99 | 3.28 | 1.131 | 0.8 | 6 | 12 | 13.54 | 7.55 |

| 11 | 2.04 | 68.99 | 3.28 | 1.131 | 0.6 | 10 | 14 | 12.24 | 7.81 |

| 12 | 2.04 | 68.99 | 3.28 | 1.131 | 0.6 | 8 | 12 | 14.58 | 3.39 |

| 13 | 1.75 | 86.25 | 3.64 | 0.940 | 1.0 | 12 | 14 | 3.39 | 13.54 |

| 14 | 1.75 | 86.25 | 3.64 | 0.940 | 0.6 | 12 | 10 | 8.59 | 7.29 |

| 15 | 1.75 | 86.25 | 3.64 | 0.940 | 1.0 | 8 | 14 | 5.73 | 8.07 |

| 16 | 2.62 | 76.25 | 11.27 | 1.042 | 0.8 | 12 | 12 | 7.03 | 5.73 |

| 17 | 2.62 | 76.25 | 11.27 | 1.042 | 0.8 | 12 | 10 | 6.51 | 7.81 |

| 18 | 2.62 | 76.25 | 11.27 | 1.042 | 0.6 | 14 | 14 | 21.88 | 0.00 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Maximum no. of iterations | 1000 |

| Target error | 1×10-4 |

| Learning rate | 0.01 |

| Training algorithm | Levenberg-Marquardt |

| Seed Type | x2 | x3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e | f | g | h | |

| Cabbage | 8 | 12 | 10 | 18 |

| Carrot | 4 | 8 | 14 | |

| Radish | 10 | 16 | ||

| Tomato | 4 | 10 | ||

| Chinese cabbage | 6 | |||

| Sesame | ||||

| Onion | ||||

| Bok choi | ||||

| Pepper | 18 | |||

| No. of Hidden-layer Neurons |

Average Value of Network Performance Indices for Two Outputs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Indices for the Training Set | Performance Indices for the Test Set | |||||

| 4 | 2.0104 | 1.4775 | 0.9313 | 2.2744 | 1.6981 | 0.9141 |

| 5 | 1.6113 | 1.2020 | 0.9549 | 2.2306 | 1.6582 | 0.9112 |

| 6 | 1.7768 | 1.2297 | 0.9466 | 2.2881 | 1.6919 | 0.9196 |

| 7 | 1.5325 | 1.1333 | 0.9601 | 2.1607 | 1.6319 | 0.9231 |

| 8 | 1.4273 | 0.9935 | 0.9641 | 2.0728 | 1.7391 | 0.9290 |

| 9 | 1.5477 | 1.1539 | 0.9593 | 2.4943 | 1.8335 | 0.9004 |

| 10 | 1.7167 | 1.1945 | 0.9500 | 2.6538 | 1.9693 | 0.8913 |

| 11 | 1.4944 | 1.0783 | 0.9602 | 2.6942 | 1.9353 | 0.8850 |

| 12 | 1.5744 | 1.1079 | 0.9579 | 2.6539 | 2.0620 | 0.8738 |

| 13 | 1.5520 | 1.1576 | 0.9591 | 2.2583 | 1.8748 | 0.9218 |

| Hidden-Layer Activation Function |

Output-Layer Activation Function |

Average Value of Network Performance Indices for Two Outputs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Indices for the Training Set | Performance Indices for the Test Set | ||||||

| Logsig | Tansig | 2.2038 | 1.5565 | 0.9179 | 2.8172 | 2.1504 | 0.8766 |

| Logsig | Purelin | 1.4273 | 0.9935 | 0.9641 | 2.0728 | 1.7391 | 0.9290 |

| Tansig | Tansig | 2.0002 | 1.3602 | 0.9323 | 2.6083 | 1.9306 | 0.8949 |

| Tansig | Purelin | 1.4303 | 1.0685 | 0.9646 | 2.1444 | 1.8452 | 0.9281 |

| Purelin | Tansig | 3.0668 | 2.2387 | 0.8409 | 3.4141 | 2.4209 | 0.8192 |

| Purelin | Purelin | 3.8248 | 2.6658 | 0.7512 | 4.2289 | 3.0312 | 0.7071 |

| Network | Output | Dataset | Performance Indices | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPNN (7-8-2) |

Missing index | Training set | 1.4883 | 1.0937 | 0.9627 |

| Test set | 1.8807 | 1.3440 | 0.9287 | ||

| Reseeding index | Training set | 1.2064 | 0.8436 | 0.9753 | |

| Test set | 2.0178 | 1.7559 | 0.9497 | ||

| Connection Weight Between Input and Hidden Layers W1 |

Connection Weight between Hidden and Output Layers (Transposition) W2T |

Hidden-layer Bias bh |

Output- layer Bias bo |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2.7320 | −1.3529 | −0.6447 | 0.5044 | 0.7261 | 3.9120 | −0.9372 | −2.1289 | −0.5536 | 6.0500 | 3.1567 |

| 2.2852 | 2.0053 | −1.2572 | 0.5124 | 3.9060 | 0.9832 | 0.1191 | 0.5815 | −1.7001 | −4.0843 | −2.1084 |

| −2.3290 | 0.2466 | 0.3522 | 0.8968 | 4.4255 | 0.5757 | −0.0804 | −1.4565 | 0.3460 | 6.4274 | |

| −1.6748 | −0.3326 | 0.8352 | 0.3386 | 0.3735 | 2.1485 | −0.5065 | −0.2870 | 1.3906 | 0.0285 | |

| 0.4245 | 0.2209 | 4.0421 | −0.1324 | −0.7695 | −2.7666 | −1.7444 | 0.0490 | −0.2990 | −3.8582 | |

| −0.1538 | −1.4328 | 1.3190 | −2.7081 | −0.5418 | −1.2597 | −0.6917 | −0.0582 | 0.2649 | −0.5468 | |

| 0.5534 | 1.7438 | −0.7404 | 1.0796 | 2.8059 | 1.2724 | 0.0536 | −0.8076 | 2.3069 | −2.5635 | |

| 1.8411 | −1.7465 | −3.2982 | 2.4162 | −0.7691 | −1.9419 | 0.2147 | −0.0975 | 1.2290 | 3.1703 | |

| Seed Type | Optimal Result |

Parameter | Indices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hole Diameter (mm) |

Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

||

| Cabbage | Experiment | 1.00 | 10.0 | 12 | 3.39 | 9.64 | 86.97 |

| Optimization | 1.00 | 11.6 | 18 | 5.20 | 6.28 | 88.52 | |

| Carrot | Experiment | 0.60 | 6.0 | 14 | 11.72 | 3.65 | 84.63 |

| Optimization | 0.77 | 4.3 | 14 | 11.70 | 2.24 | 86.06 | |

| Radish | Experiment | 1.00 | 10.0 | 10 | 10.94 | 0.00 | 89.06 |

| Optimization | 0.98 | 10.6 | 10 | 8.76 | 1.59 | 89.65 | |

| Onion | Experiment | 0.80 | 8.0 | 14 | 11.20 | 5.99 | 82.81 |

| Optimization | 0.71 | 6.2 | 10 | 11.96 | 3.36 | 84.68 | |

| Chinese cabbage | Experiment | 0.60 | 10.0 | 14 | 10.94 | 4.95 | 84.11 |

| Optimization | 0.70 | 9.0 | 14 | 10.48 | 5.19 | 84.33 | |

| Sesame | Experiment | 1.00 | 6.0 | 10 | 7.03 | 12.50 | 80.47 |

| Optimization | 0.85 | 6.3 | 14 | 10.52 | 6.46 | 83.03 | |

| Seed Type | Geometric Mean Diameter (mm) |

Sphericity (%) |

Thousand-Grain Weight (g) |

Kernel Density (g·cm-3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato | 1.78±0.13 | 52.33±4.17 | 3.02±0.06 | 1.147±0.058 |

| Pepper | 2.19±0.21 | 54.60±3.77 | 5.47±0.05 | 0.937±0.054 |

| Bok choi | 1.60±0.10 | 93.14±2.79 | 2.60±0.05 | 0.975±0.039 |

| Seed Type | Parameter | Indices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hole Diameter (mm) | Vacuum Pressure (kPa) |

Rotational Speed (rpm) |

Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|

| Tomato | 0.75 | 5.6 | 13.7 | 11.85 | 2.66 | 85.50 |

| Pepper | 1.00 | 10.4 | 18.0 | 11.54 | 2.94 | 85.52 |

| Bok choi | 0.67 | 8.6 | 14.0 | 10.72 | 4.41 | 84.87 |

| Seed Type | Missing Index (%) |

Reseeding Index (%) |

Qualified Index (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato | Predicted value | 11.85 | 2.66 | 85.50 |

| Experimental value | 11.19 | 2.08 | 86.73 | |

| Absolute error | 0.66 | 0.58 | 1.23 | |

| Pepper | Predicted value | 11.54 | 2.94 | 85.52 |

| Experimental value | 8.85 | 3.65 | 87.50 | |

| Absolute error | 2.69 | 0.71 | 1.98 | |

| Bok choi | Predicted value | 10.72 | 4.41 | 84.87 |

| Experimental value | 9.11 | 5.21 | 85.68 | |

| Absolute error | 1.61 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).