1. Introduction

Hemodynamic coherence is the balance that must be preserved between the macrocirculation and microcirculation to maintain tissue perfusion. Although the term was first mentioned in 1850, its characteristics both in healthy states and disease are largely unknown. This is primarily due to the complex mechanisms required to maintain homeostasis over a very wide range of oxygen concentrations and/or perfusion changes, as well as due to the heterogeneity of critical illness. Most clinicians are currently blind to what is happening in the microcirculation of organs and limit hemodynamic resuscitation to an optimization of systemic hemodynamics [

1]. Nevertheless, relying purely on macrohemodynamic targets may fail to improve microvascular perfusion and even prove deleterious.

Videomicroscopy allows for direct, noninvasive, real-time visualization of capillary networks, facilitating reliable assessment and immediate quantitative analysis of the microcirculation at the patient's bedside. Specifically, direct observation of the sublingual area may provide an excellent window to investigate the microcirculation and a unique insight into the underlying hemodynamic coherence, while the use of automatic analysis may eliminate observer bias. This is particularly important because sublingual microcirculation reflects visceral microcirculation and its assessment may facilitate the implementation of individualized, physiology-guided treatment strategies.

Capillary tortuosity is a morphologic variant of microcirculatory vessels. Although it is not clear how tortuous vessels form, they are thought to result from physiological and pathological phenomena associated with microvascular adaptation including increased cytokine and growth factor signaling, changes in flow dynamics, changes in extracellular matrix composition, decreased mural cell coverage, and in response to endurance training [

2,

3,

4]. It is plausible, though, that the behavior of these vessels plays a central role in processes associated with blood distribution and oxygen transport to tissue. Nevertheless, the effects of microvascular tortuosity are generally not considered as an important hemodynamic quantity in health and disease.

In the present study, we investigated the role of sublingual capillary tortuosity in the hemodynamic coherence of anesthetized individuals with steady-state physiology and patients with septic shock.

2. Materials and Methods

This was an ancillary analysis of two prospective cohorts [

5,

6]. We included patients undergoing elective major non-cardiac surgery and surgical patients with septic shock. The underlying studies were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and relevant regulatory requirements. The original protocol (NCT03851965) was approved by the UHL Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 60580, 11 December 2018). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study or their next-of-kin. This work is reported according to STROCSS criteria [

7].

2.1. Study Objectives

The primary objective was to characterize sublingual microvascular tortuosity in steady-state physiology and septic shock. Our secondary objective was to investigate the association of sublingual tortuosity with (1) macrohemodynamic, (2) microhemodynamic, and (3) tissue oxygenation parameters.

2.2. Patients with Steady-State Physiology

We considered adults fulfilling the following criteria: patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I; sinus rhythm in electrocardiogram; and no evidence of structural heart disease confirmed by preoperative echocardiography [

5]. Before anesthesia induction, all patients received 5 mL kg

−1 of a balanced crystalloid solution to compensate for preoperative fasting and vasodilation associated with general anesthetics. Anesthesia was induced in the supine position and included midazolam 0.15–0.35 mg kg

−1, fentanyl 1 μg kg

−1, ketamine 0.2 mg kg

−1, propofol 1.5–2 mg kg

−1, rocuronium 0.6 mg kg

−1, and a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.7. All patients were mechanically ventilated using a lung-protective strategy with tidal volume of 7 mL kg

−1, positive end-expiratory pressure of 6–8 cmH

2O, and plateau pressure < 30 cmH

2O.

General anesthesia was maintained by inhalation of desflurane at an initial 1.0 minimal alveolar concentration. Thereafter, depth of anesthesia was adjusted to maintain Bispectral Index (BIS, Covidien, France) between 40 and 60. Intraoperative fraction of inspired oxygen was also adjusted to maintain an arterial oxygen partial pressure of 80–100 mmHg. Normocapnia, normothermia (37 °C), and normoglycemia were maintained during the perioperative period.

2.3. Patients with Septic Shock

We included adult patients with septic shock requiring emergency abdominal surgery. Septic shock was defined as circulatory and cellular/metabolic dysfunction that persisted despite adequate fluid resuscitation and required the administration of vasopressors [

6,

8]. Before induction of anesthesia, all patients with a central venous pressure (CVP) < 4 mmHg received 7 mL kg

−1 of a balanced crystalloid solution. Vasopressor dose was titrated to maintain an individualized mean arterial pressure (MAP) level (in all cases > 65 mmHg) based on the patient preadmission levels and tissue perfusion via clinical decision. Anesthesia was induced using regimens that contained fentanyl, ketamine, propofol, rocuronium, and a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.7 and maintained by inhalation of desflurane at an initial 1.0 minimal alveolar concentration. The depth of anesthesia was then adjusted to maintain BIS between 40 and 60. All patients were ventilated using a lung-protective strategy. Normoxemia, normocapnia, normothermia, and normoglycemia were also maintained during the perioperative period.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Macrohemodynamics

The radial artery was cannulated and connected to a FloTrac/EV1000 clinical platform (Edwards Life Sciences, Irvine, CA, USA) to directly measure MAP, cardiac output, cardiac index, stroke volume, stroke volume variation, and systemic vascular resistance. The internal jugular vein was cannulated with a triple-lumen central venous catheter that was connected to a pressure transducer to measure CVP and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO

2). Mean circulatory filling pressure analogue and related values were calculated as previously described [

9]. Cardiac power output [CPO = (CO × MAP) / 451] and power [Power = CO × (MAP – CVP) × 0.0022] were also calculated; these parameters represent the rate of energy input the systemic vasculature receives from the heart at the level of the aortic root to maintain the perfusion of the vital organs in shock states [

10]. Before making study measurements, we confirmed that transducers were correctly leveled and zeroed, while the systems’ dynamic response was confirmed with fast-flush tests. Artifacts were detected and removed when documented, and when measurements were out-of-range or systolic and diastolic pressure were similar or abruptly changed (≥40 mmHg decrease or increase within 2 min before and after measurement).

2.4.2. Sublingual Microcirculation

Sublingual microcirculation was monitored using sidestream dark field (SDF+) imaging (Microscan; Microvision Medical BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), in accordance with the guidelines on the assessment of sublingual microcirculation of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine [

11]. In both groups, microcirculation was assessed 30 minutes after induction of general anesthesia before surgical incision. In patients with septic shock, microcirculation was assessed after normalization of macrohemodynamics.

At each measurement point, we recorded sublingual microcirculation videos from at least five sites. To optimize video quality, we tried to avoid pressure and movement artefacts, optimized focus and illumination, and cleaned saliva and/or blood from the sublingual mucosa. The process of video acquisition was further mediated by a validated automatic algorithm software [AVA 4.3C (Microvision Medical, Amsterdam, the Netherlands)] to ensure adequate brightness, focus, and stability. Before sublingual perfusion analysis, all videos were evaluated by two experienced raters blinded to all patient data, according to a modified microcirculation image quality score (MIQS) [

12]. The best three videos from each recording were analyzed offline by a blinded investigator and with the AVA4.3C Research Software [

11,

13].

We analyzed the De Backer score (in mm-1; it equals the number of crossings of the capillary web × 21), the Consensus Proportion of Perfused Vessels (Consensus PPV; it is a ratio of perfused capillaries from all visible capillaries given as a percentage), the Consensus PPV (small) (i.e., the PPV of vessels of a diameter ≤25 μm), and the Microvascular Flow Index (MFI). To assess the latter, the screen is divided into four quadrants and a score between 0 and 3 reflecting the average red blood cell (RBC) velocity is given per quadrant. Thereafter, MFI is calculated as the mean MFI averaged over the four quadrants.

Vessel diameter, vessel length, and RBC velocity were determined with the latest version of AVA software using a modified optical flow-based algorithm; the method uses per video frame data to measure the overall velocity per vessel segment. Sublingual tortuosity was assessed with the Capillary Tortuosity Score (CTS), a microvascular score with a good inter- and intraobserver variability, that morphologically assesses microvascular architecture based on the number of twists per capillary existing in the field of view [

14]. The number of twists among the majority of the capillaries defines the score and varies from pinhead twists to four twists (Score 0: no twists; Score 1: one twist; Score 2: two twists; Score 3: three twists; Score 4: four twists) [

14].

2.4.3. Determination of Capillary Shear Stress

The capillary network (pre-capillary arterioles, capillary bed, post-capillary venules) is characterized by a high degree of structural heterogeneity and an asymmetric and irregular distribution in the vasculature [

15,

16]. As microvascular flow is controlled by viscous forces, microvascular shear stress, i.e., the tangential force of the flowing blood on the endothelial surface of the blood vessel, was estimated using the force balance equation τ

w = (ΔP × d) / 4L, where d and L are the diameter and length of a microvessel, respectively, and ΔP is the pressure difference across the capillary [

17]. Based on previous studies from our group [

5], a ΔP of 0.1 Pa and 0.02 Pa were used for the steady-state and septic shock group, respectively.

2.4.4. Oxygen Transport and Transitions of Metabolism

Alveolar-to-arterial oxygen Gradient (A-a O2 Gradient), expected A-a O2 Gradient for age, arterial oxygen content [CaO2 = (0.0138 × Hb x SaO2) + (0.0031 × PaO2)], venous oxygen content [CvO2 = (0.0138 × Hb × ScvO2) + (0.0031 × PcvO2)], venous-arterial oxygen content difference (Cv-aO2), oxygen delivery (DO2 = CaO2 × CO × 10), and oxygen consumption (VO2 = C(a - v)O2 × CO × 10) were monitored. Oxygen extraction ratio was calculated as the ratio of VO2 to DO2 using the formula O2ER = VO2 / DO2 = (SaO2 – ScvO2) / SaO2.

Microcirculatory oxygen transport was also quantified by calculating convective oxygen flow (Q

CO

2) using the equation Q

CO

2=

πd

2/4 × V

RBC × [Hb] × SO

2 × C

Hb, which can be used regardless of the underlying hematocrit [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In this equation, d is the microvessel diameter, V

RBC is the average RBC velocity, SO

2 is the hemoglobin oxygen saturation in microvessels, and C

Hb is the oxygen binding capacity of hemoglobin (1.34 ml O

2 gHb

-1; reduced from the stoichiometrically expected 1.39 by the usual presence of 1-2% methemoglobin plus 1-2% COHb) [

18,

22,

23]. Sublingual SO

2 was set at 0.47 based on previous studies and the described dynamic balance between oxygen supply and consumption in healthy states and conditions of septic shock [

18,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Determination of hemoglobin concentration was based on the volumetric relationship between the RBCs and the plasma, when blood is streaming through microvessels of different diameter (

Table 1) [

27,

29].

Transitions from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism were monitored using oxygen debt (OXD). The latter can be calculated at the bedside using the formula described by Dunham et al., which involves the relationship between lactate and base excess [OXD = 6.322 (Lactate) – 2.311 (BE) – 9.013] [

30] and demonstrates alterations in DO

2 / VO

2 with a solid physiological basis [

31,

32]. A negative OXD value indicates normal physiology with aerobic metabolism and adequate physiological reserves, while a positive OXD value indicates an underlying state of oxygen deficiency and anaerobic metabolism.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R v4.4 software. Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (standard deviation; SD). The Mann-Whitney test was employed to assess the statistical significance of the differences in CTS between groups. Spearman’s method was used to estimate the strength of the correlations between CTS and the various microcirculation parameters. In order to adjust for the presence of multiple comparisons, the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction was utilized. p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

In total, 33 anesthetized individuals were included in the analysis (steady-state, n = 20; septic shock, n = 13) [

5,

6]. A statistically significant difference was observed in age (p<0.001), sex (p=0.009), ASA score (p<0.001), BMI (p=0.002), and anesthesia parameters between the two groups (

Table 2).

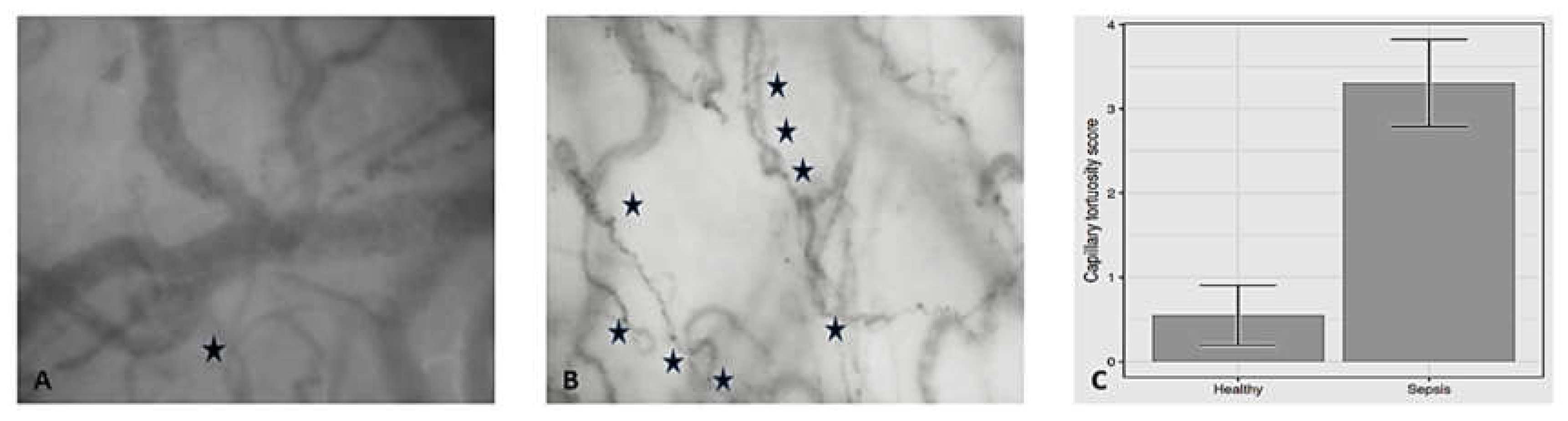

Intraoperative hemodynamic variables are presented in

Table 3. A significant difference was observed in heart rate (p<0.001), stroke volume (p=0.001), stroke volume variation (p<0.001), systemic vascular resistance (p<0.001), CVP (p<0.001), mean circulatory filling pressure analogue (p<0.001), Consensus PPV (p<0.001), Consensus PPV (small) (p<0.001), MFI (p<0.001), vessel diameter (p<0.001), vessel length (p<0.001), τ

w (p

<0.001), and CTS (p<0.001) between the two groups (

Figure 1).

Intraoperative oxygen transport and metabolic variables are presented in

Table 4. A significant difference was observed in venous-arterial carbon dioxide difference (p<0.001), bicarbonate (p=0.003), hemoglobin (p<0.001), lactate (p<0.001), A-a O

2 Gradient (p<0.001), peripheral oxygen saturation (p=0.001), arterial oxygen saturation (p<0.001), ScvO

2 (p=0.015), O

2ER (p=0.001), CaO

2 (p<0.001), CvO

2 (p<0.001), Cv-aO

2 (p<0.001), DO

2 (p<0.001), VO

2 (p<0.001), Q

CO

2 (p<0.001), and OXD (p=0.002) between the two groups.

3.1. Capillary Tortuosity in Individuals with Steady-State Physiology

Mean (SD) CTS was 0.55 (0.76). In this group, CTS was significantly associated with DAP (r = –0.471, p=0.036), Consensus PPV (small) (r = –0.458, p=0.042), arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (r = 0.512, p=0.021), base deficit (r = – 0.463, p=0.04), hemoglobin (r = – 0.459, p=0.042), expected A-a O

2 Gradient for age (r = – 0.685, p=0.001), and CaO

2 (r = – 0.474, p=0.035) (

Table 5 and

Table 6).

3.2. Capillary Tortuosity in Patients with Septic Shock

Mean (SD) CTS was 3.31 (0.86). In this group, CTS was significantly associated with A-a O

2 Gradient (r = 0.658, p=0.015) and OXD (r = –0.769, p=0.002) (

Table 7 and

Table 8).

3.3. Association of Capillary Tortuosity with Hemodynamic and Oxygen Transport/Metabolic Variables in the Entire Study Sample

The Spearman’s method was used to estimate the strength of the association between CTS and the assessed hemodynamic and oxygen changes/metabolic variables using the entire study sample (N=33). Capillary Tortuosity Score was significantly associated with several hemodynamic and oxygen transport/metabolic variables (

Table S1).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate sublingual capillary tortuosity and its role in hemodynamic coherence in anesthetized individuals with steady-state physiology and patients with septic shock. Sublingual tortuosity was essentially absent in individuals with steady-state physiology. In contrast, sublingual CTS was significantly increased in patients with septic shock and associated with A-a O2 Gradient and OXD. Significant differences were also observed in several macrohemodynamic and oxygen transport/metabolic variables between the two groups. Patients with septic shock were characterized by significant microvascular impairment and lower τw compared to those with steady-state physiology.

Tortuous capillaries have been observed in skeletal muscles, myocardium, and other organs of humans and animals [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Although their clinical significance remains vague, the dynamics and behavior of blood flowing through these vessels may play a central role in various physiological processes such as embryonic development, tissue oxygenation, muscle contraction, new vessel sprouting, and microvascular blood distribution [

37,

44]. Clinical observations have also linked tortuous vessels to various pathological conditions (e.g., atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, coronary disease), while the evidence for others (e.g., hypertension) are contradictory [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47].

A crucial aspect of sepsis involves cardiovascular/circulatory dysfunction and increases in oxygen demand. The pathophysiology of impaired oxygen transport and extraction is complex and includes microvascular injury, abnormal distribution of blood flow, and increases in the diffusion gradient for oxygen from the capillaries to the mitochondria. Furthermore, in hypoxic conditions, RBCs lose their ability to release vasodilators and cannot contribute to the autoregulation of microvascular blood flow and DO

2 [

48,

49,

50]. The aforementioned phenomena contribute to the emergence of two of the most striking manifestations of sepsis, i.e., loss of functional capillary density and microvascular heterogeneity. These structural changes are evident in several tissues and organs including the liver, skeletal muscle, intestinal villi, diaphragm, and the sublingual microcirculation [

29,

48].

In the present study, sublingual microvascular tortuosity was essentially absent in individuals with steady-state physiology. In contrast, it was significantly increased and associated with A-a O

2 Gradient and OXD in patients with septic shock. Although the underlying pathogenic mechanisms remain unknown, sepsis-induced mechanical instability and remodeling and the increase in the curvature and intraluminal pressures of collateral vessels bridging adjacent regions may enhance vessel tortuosity [

3,

45]. Apparently, the negative correlation between OXD and CTS in this group is due to resuscitation efforts. Indeed, all patients were macrohemodynamically optimized prior to assessing the microcirculation, which improved lactate and base excess levels and, therefore, OXD in some patients [

51,

52].

The low sublingual τ

w in patients with septic shock, despite the macrohemodynamic optimization and their increased CTS, is intriguing enough and merits additional discussion and consideration. Shear stress may be lower in tortuous microvessels relative to normal capillaries downstream of altered vessel morphology [

3]. It is important to remember, though, that the wall shear stress spatial patterns caused by tortuosity are distinct and must be assessed according to the evaluation region [

44]. Our findings, in conjunction with previous studies [

3,

4,

44,

53,

54,

55,

56], indicate microvascular tortuosity as an adaptive and compensatory mechanism to improve both the convective delivery to the capillary bed and the diffusive transport from RBCs to mitochondria, maintaining aerobic metabolism in the early stages of sepsis and -presumably- when DO

2 approaches its critical threshold (maximum O

2ER). Tortuous vessels may function as collateral channels with lower RBC velocities to reduce the rate of capillary oxygen transport, while enhancing local oxygen diffusion to surrounding tissue [

44,

57,

58,

59].

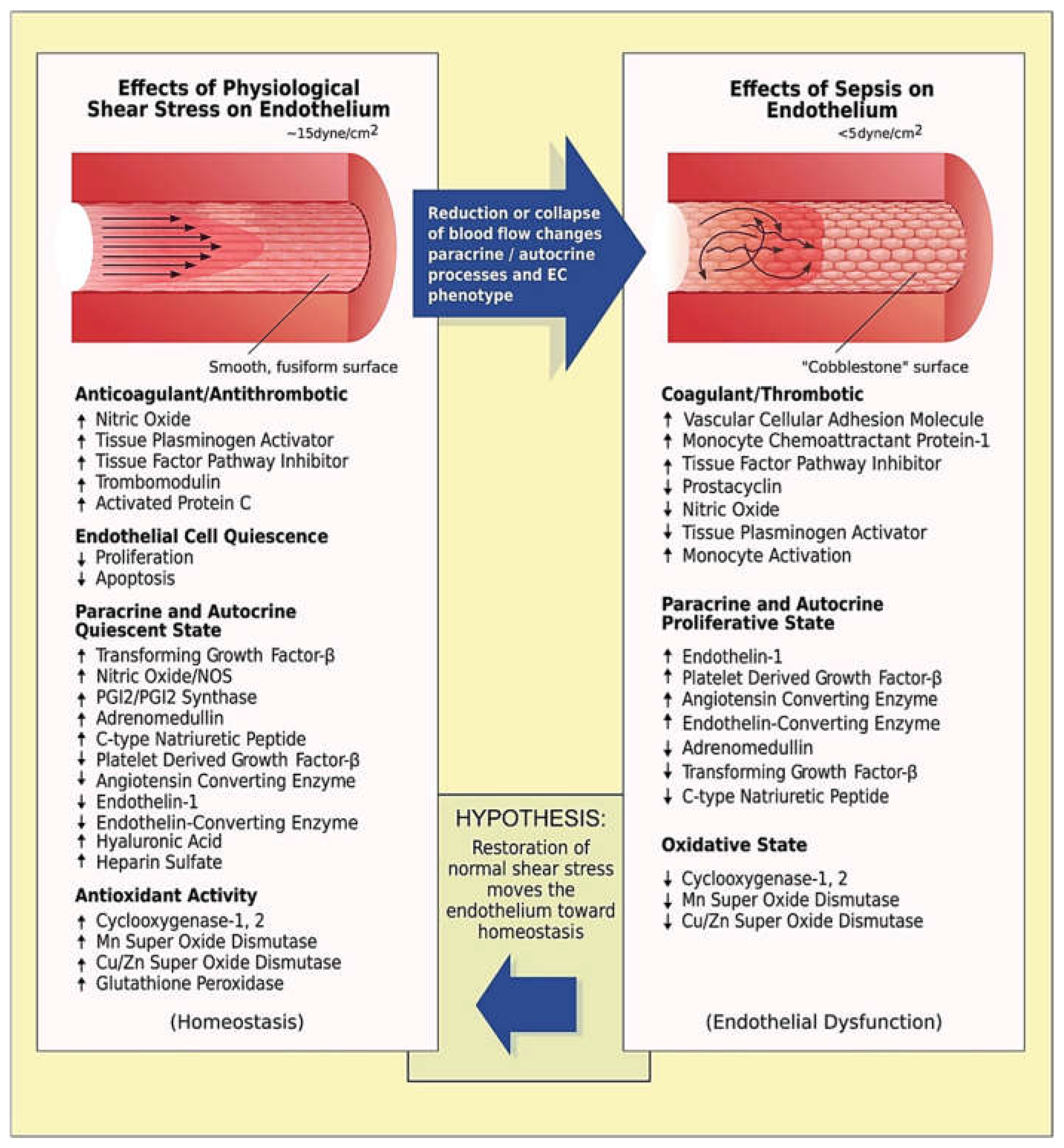

In later stages of sepsis, capillary tortuosity may turn into a maladaptive response depending on the (heterogenous) immune dysregulation and the evolution of critical illness. In patients with severe disease, augmenting tortuosity may increase lumen and wall shear stress [

45,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65] in an attempt to compensate for the effects of impaired blood flow on vascular endothelium (

Figure 2) [

66]. However, this may not be sufficient to prevent the emergence of hemodynamic incoherence (mainly type 1 and/or type 3 microcirculatory alterations) and the exacerbation of the Fåhræus and Fåhræus–Lindqvist effects [

5,

45,

67,

68]. Tissue hypoperfusion can be further aggravated by the impairment of RBC membrane deformability and shape recovery; in septic conditions, RBCs become less deformable and more easily aggregate with endothelial cells, thus compromising blood flow [

48,

69,

70,

71]. However, since many tissues function physiologically at levels equivalent to an atmosphere of 5% oxygen, and some at levels as low as 1% oxygen [

72,

73], the role of microvascular tortuosity as a physiological response to sepsis appear to be extremely important and should be clarified in subsequent studies.

A number of limitations must be acknowledged. Although the present physiological study includes a relatively small sample size, data collection and analyses were conducted by blinded investigators, minimizing inter-observer bias and increasing the credibility of study conclusions. At each measurement point, we recorded sublingual microcirculation videos from at least five sites and followed the guidelines on the assessment of sublingual microcirculation of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine [

11]. Another limitation is the difference in age and comorbidities between the two groups; thus, the results of the present analysis may be different in other patient populations. In addition, anesthesia can lower resting metabolic rate and reduce global VO

2 and has been associated with a reduction in the ability of tissues to extract oxygen. However, we used desflurane for maintenance of anesthesia because it produces mild and stable effects on the microcirculation compared to other agents [

5,

6]. We also maintained normoxia, normocapnia, normoglycemia, and normothermia to minimize the iatrogenic effects on microvascular perfusion [

74,

75,

76]. All septic shock patients were macrohemodynamically optimized prior to assessing the microcirculation, which improved lactate and base excess levels and, therefore, OXD in some of them. Finally, the pulsatile nature and occasional turbulence of blood flow, the tapered cross-section and distensibility of blood vessels, and the non-Newtonian behavior of blood may limit the accuracy of τ

w estimation [

77].

5. Conclusions

Sublingual tortuosity was essentially absent in individuals with steady-state physiology. In contrast, sublingual CTS was significantly increased and associated with A-a O2 Gradient and OXD in patients with septic shock. While important hemodynamic quantities have been extensively studied over many decades, capillary tortuosity has generally not been considered as a determinant of hemodynamic coherence in health and disease. The present analysis provides interesting insights into the aforementioned relationship. Overall, the increase in sublingual tortuosity appears to be a physiological adaptive response to sepsis-induced microvascular dysfunction and tissue hypoxia. The patterns identified here emphasize the need for a physiological basis for understanding the impact of tortuous morphologies in sepsis and other pathological conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Table S1: Association of Capillary Tortuosity Score with demographic, hemodynamic, and metabolic variables in the full study sample.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.; methodology, A.C.; software, A.C. and N.P.; validation, A.C. and N.P.; formal analysis, N.P.; investigation, A.C.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.C. and N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.C., N.P., K.K., A.D., A.G., S.K., G.K., F.K., A.P., and P.T.; visualization, A.C., N.P., K.K., A.D., A.G., S.K., G.K., F.K., A.P., and P.T.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The underlying studies were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and relevant regulatory requirements. The original protocol (NCT03851965) was approved by the UHL Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 60580, 11 December 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study or their next-of-kin.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request after publication through a collaborative process. Researchers should provide a methodically sound proposal with specific objectives in an approval proposal. Please contact the corresponding author for additional information.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Z. Hossain, medical software engineer at Microvision Medical (Amsterdam, The Netherlands), who provided technical expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duranteau, J.; De Backer, D.; Donadello, K.; Shapiro, N.I.; Hutchings, S.D.; Rovas, A.; Legrand, M.; Harrois, A.; Ince, C. The future of intensive care: the study of the microcirculation will help to guide our therapies. Crit. Care. 2023, 27, 190. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.A.; Chang, S.H.; Dvorak, A.M.; Dvorak, H.F. Why are tumour blood vessels abnormal and why is it important to know? Br. J. Cancer. 2009, 100, 865-869. [CrossRef]

- Chong, D.C.; Yu, Z.; Brighton, H.E.; Bear, J.E.; Bautch, V.L. Tortuous Microvessels Contribute to Wound Healing via Sprouting Angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1903-1912. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.; Nielsen, N.D. Oxygen delivery and consumption: a macrocirculatory perspective. Crit. Care. Clin. 2010, 26, 239-253. [CrossRef]

- Chalkias, A.; Xenos, M. Relationship of Effective Circulating Volume with Sublingual Red Blood Cell Velocity and Microvessel Pressure Difference: A Clinical Investigation and Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4885. [CrossRef]

- Chalkias, A.; Laou, E.; Mermiri, M.; Michou, A.; Ntalarizou, N.; Koutsona, S.; Chasiotis, G.; Garoufalis, G.; Agorogiannis, V.; Kyriakaki, A.; Papagiannakis, N. Microcirculation-guided treatment improves tissue perfusion and hemodynamic coherence in surgical patients with septic shock. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2022, 48, 4699–4711. [CrossRef]

- Agha, R.; Abdall-Razak, A.; Crossley, E.; Dowlut, N.; Iosifidis, C.; Mathew, G.; STROCSS Group. STROCSS 2019 Guideline: Strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2019, 72, 156-165. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; Rochwerg, B.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Angus, D.C.; Annane, D.; Beale, R.J.; Bellinghan, G.J.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.; De Backer, D.P.; French, C.J.; Fujishima, S.; Gerlach, H.; Hidalgo, J.L.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Jones, A.E.; Karnad, D.R.; Kleinpell, R.M.; Koh, Y.; Lisboa, T.C.; Machado, F.R.; Marini, J.J.; Marshall, J.C.; Mazuski, J.E.; McIntyre, L.A.; McLean, A.S.; Mehta, S.; Moreno, R.P.; Myburgh, J.; Navalesi, P.; Nishida, O.; Osborn, T.M.; Perner, A.; Plunkett, C.M.; Ranieri, M.; Schorr, C.A.; Seckel, M.A.; Seymour, C.W.; Shieh, L.; Shukri, K.A.; Simpson, S.Q.; Singer, M.; Thompson, B.T.; Townsend, S.R.; Van der Poll, T.; Vincent, J.L.; Wiersinga, W.J.; Zimmerman, J.L.; Dellinger, R.P. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive. Care. Med. 2017, 43, 304–377. [CrossRef]

- Laou, E.; Papagiannakis, N.; Sarchosi, S.; Kleisiaris, K.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Syngelou, V.; Kakagianni, M.; Christopoulos, A.; Ntalarizou, N.; Chalkias, A. The use of mean circulatory filling pressure analogue for monitoring hemodynamic coherence: A post-hoc analysis of the SPARSE data and proof-of-concept study. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2023, 84, 19-32. [CrossRef]

- Fincke, R.; Hochman, J.S.; Lowe, A.M.; Menon, V.; Slater, J.N.; Webb, J.G.; LeJemtel, T.H.; Cotter, G.; SHOCK Investigators. Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: a report from the SHOCK trial registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 340-348. [CrossRef]

- Ince, C.; Boerma, E.C.; Cecconi, M.; De Backer, D.; Shapiro, N.I.; Duranteau, J.; Pinsky, M.R.; Artigas, A.; Teboul, J.L.; Reiss, I.K.M.; Aldecoa, C.; Hutchings, S.D.; Donati, A.; Maggiorini, M.; Taccone, F.S.; Hernandez, G.; Payen, D.; Tibboel, D.; Martin, D.S.; Zarbock, A.; Monnet, X.; Dubin, A.; Bakker, J.; Vincent, J.L.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; Cardiovascular Dynamics Section of the ESICM. Second consensus on the assessment of sublingual microcirculation in critically ill patients: results from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive. Care. Med. 2018, 44, 281-299. [CrossRef]

- Massey, M.J.; Larochelle, E.; Najarro, G.; Karmacharla, A.; Arnold, R.; Trzeciak, S.; Angus, D.C.; Shapiro, N.I. The microcirculation image quality score: development and preliminary evaluation of a proposed approach to grading quality of image acquisition for bedside videomicroscopy. J. Crit. Care. 2013, 28, 913-917. [CrossRef]

- Dobbe, J.G.; Streekstra, G.J.; Atasever, B.; van Zijderveld, R.; Ince, C. Measurement of functional microcirculatory geometry and velocity distributions using automated image analysis. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2008, 46, 659-670. [CrossRef]

- Djaberi, R.; Schuijf, J.D.; de Koning, E.J.; Wijewickrama, D.C.; Pereira, A.M.; Smit, J.W.; Kroft, L.J.; Roos, A.d.; Bax, J.J.; Rabelink, T.J.; Jukema, J.W. Non-invasive assessment of microcirculation by sidestream dark field imaging as a marker of coronary artery disease in diabetes. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2013, 10, 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.K.; Balaratnasingam, C.; Cringle, S.J.; McAllister, I.L.; Provis, J.; Yu, D.Y. Microstructure and network organization of the microvasculature in the human macula. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 6735-6743. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.I.; Cho, D.J. Hemorheology and microvascular disorders. Korean. Circ. J. 2011, 41, 287-295. [CrossRef]

- Munson, B.R.; Young, D.F.; Okiishi, T.H.; Huebsch, W.W. Fundamentals of Fluid Mechanics. 6th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

- Pittman, R.N. Oxygen gradients in the microcirculation. Acta. Physiol. (Oxf). 2011, 202, 311-322. [CrossRef]

- Swain, D.P.; Pittman, R.N. Oxygen exchange in the microcirculation of hamster retractor muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1989, 256, H247-255. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Pittman, R.N. Effect of hemodilution on oxygen transport in arteriolar networks of hamster striated muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1988, 254, H331-339. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Pittman, R.N. Influence of hemoconcentration on arteriolar oxygen transport in hamster striated muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1990, 259, H1694-1702. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.C.; Wayland, H. Regulation of blood flow in single capillaries. Am. J. Physiol. 1967, 212, 1405-1415. [CrossRef]

- Wayland, H.; Johnson, P.C. Erythrocyte velocity measurement in microvessels by a two-slit photometric method. J. Appl. Physiol. 1967, 22, 333-337. [CrossRef]

- Awan, Z.A.; Häggblad, E.; Wester, T.; Kvernebo, M.S.; Halvorsen, P.S.; Kvernebo, K. Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy: Systemic and microvascular oxygen saturation is linearly correlated and hypoxia leads to increased spatial heterogeneity of microvascular saturation. Microvasc. Res. 2011, 81, 245-251. [CrossRef]

- Torres Filho, I.; Nguyen, N.M.; Jivani, R.; Terner, J.; Romfh, P.; Vakhshoori, D.; Ward, K.R. Oxygen saturation monitoring using resonance Raman spectroscopy. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 201, 425-431. [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, H.H.; Usami, S.; Chien, S.; Pittman, R.N. Hematocrit determination in small bore tubes by differential spectrophotometry. Microvasc. Res. 1982, 24, 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Fåhræus, R. The suspension stability of blood. Physiol. Rev. 1929, 9, 241-274. [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.; Fasano, A.; Rosso, F. A theoretical model for the Fahraeus effect in medium-large microvessels. J. Theor. Biol. 2023, 558, 111355. [CrossRef]

- Archontakis-Barakakis, P.; Mavridis, T.; Chlorogiannis, D-D.; Barakakis, G.; Laou, E.; Sessler, D.I.; Gkiokas, G.; Chalkias, A. Intestinal oxygen utilisation and cellular adaptation during intestinal ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70136. [CrossRef]

- Dunham, C.M.; Siegel, J.H.; Weireter, L.; Fabian, M.; Goodarzi, S.; Guadalupi, P.; Gettings, L.; Linberg, S.E.; Vary, T.C. Oxygen debt and metabolic acidemia as quantitative predictors of mortality and the severity of the ischemic insult in hemorrhagic shock. Crit. Care. Med. 1991, 19, 231-243. [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, W.C.; Appel, P.L.; Kram, H.B. Tissue oxygen debt as a determinant of lethal and nonlethal postoperative organ failure. Crit. Care. Med. 1988, 16, 1117-1120. [CrossRef]

- Papagiannakis, N.; Ragias, D.; Ntalarizou, N.; Laou, E.; Kyriakaki, A.; Mavridis, T.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Sakellakis, M.; Chalkias, A. Transitions from Aerobic to Anaerobic Metabolism and Oxygen Debt during Elective Major and Emergency Non-Cardiac Surgery. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 1754. [CrossRef]

- Weibel, J.; Fields, W.S. Tortuosity, coiling, and kinking of the internal carotid artery. I. Etiology and radiographic anatomy. Neurology. 1965, 15, 7-18. [CrossRef]

- Schep, G.; Kaandorp, D.W.; Bender, M.H.; Weerdenburg, H.; van Engeland, S.; Wijn, P.F. Magnetic resonance angiography used to detect kinking in the iliac arteries in endurance athletes with claudication. Physiol. Meas. 2001, 22, 475-487. [CrossRef]

- Helisch, A.; Schaper, W. Arteriogenesis: the development and growth of collateral arteries. Microcirculation. 2003, 10, 83-97. [CrossRef]

- Batra, S.; Rakusan, K. Capillary length, tortuosity, and spacing in rat myocardium during cardiac cycle. Am. J. Physiol. 1992, 263, H1369-1376. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu-Costello, O.; Potter, R.F.; Ellis, C.G.; Groom, A.C. Capillary configuration and fiber shortening in muscles of the rat hindlimb: correlation between corrosion casts and stereological measurements. Microvasc. Res. 1988, 36, 40-55. [CrossRef]

- Pries, A.R.; Secomb, T.W. Structural adaptation of microvascular networks and development of hypertension. Microcirculation. 2002, 9, 305-314. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, P.M.; Marshburn, T.H.; Maultsby, S.J.; Lynch, C.D.; Smith, T.L.; Dusseau, J.W. Long-term microvascular response to hydralazine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1988, 12, 74-79. [CrossRef]

- Miodoński, A.J.; Litwin, J.A. Microvascular architecture of the human urinary bladder wall: a corrosion casting study. Anat. Rec. 1999, 254, 375-381.

- Owen, C.G.; Newsom, R.S.; Rudnicka, A.R.; Barman, S.A.; Woodward, E.G.; Ellis, T.J. Diabetes and the tortuosity of vessels of the bulbar conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 2008, 115, e27-32. [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T.; Bhutto, I.A. Retinal vascular changes and systemic diseases: corrosion cast demonstration. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 2001, 106, 237-244.

- Zebic Mihic, P.; Saric, S.; Bilic Curcic, I.; Mihaljevic, I.; Juric, I. The Association of Severe Coronary Tortuosity and Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023, 59, 1619. [CrossRef]

- Pittman, R.N. Oxygen transport in the microcirculation and its regulation. Microcirculation. 2013, 20, 117-137. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.C. Twisted blood vessels: symptoms, etiology and biomechanical mechanisms. J. Vasc. Res. 2012, 49, 185-197. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, G.M.; Miner, M.M.; Bulkley, B.H. Tortuosity as an index of the age and diameter increase of coronary collateral vessels in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1978, 41, 210-215. [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, U.; Scherillo, G.; Casaburi, C.; Di Martino, M.; Di Gianni, A.; Serpico, R.; Fazio, S.; Saccà, L. Prospective evaluation of hypertensive patients with carotid kinking and coiling: an ultrasonographic 7-year study. Angiology. 2003, 54, 169-175. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.M.; Sharpe, M.D.; Ellis, C.G. Bench-to-bedside review: microvascular dysfunction in sepsis--hemodynamics, oxygen transport, and nitric oxide. Crit. Care. 2003, 7, 359-373. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.M.; Sharpe, M.D.; Jagger, J.E.; Ellis, C.G. Sepsis impairs microvascular autoregulation and delays capillary response within hypoxic capillaries. Crit. Care. 2015, 19, 389. [CrossRef]

- Singel, D.J.; Stamler, J.S. Chemical physiology of blood flow regulation by red blood cells: the role of nitric oxide and S-nitrosohemoglobin. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005, 67, 99-145.

- Khosravani-Rudpishi, M.; Joharimoghadam, A.; Rayzan, E. The significant coronary tortuosity and atherosclerotic coronary artery disease; What is the relation? J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 2018, 10, 209-213. [CrossRef]

- Raia L, Zafrani L. Endothelial Activation and Microcirculatory Disorders in Sepsis. Front. Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9, 907992. [CrossRef]

- Lundby, C.; Montero, D. CrossTalk opposing view: Diffusion limitation of O2 from microvessels into muscle does not contribute to the limitation of V̇O2 max. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 3759-3761. [CrossRef]

- Willi, C.E.; Abdelazim, H.; Chappell, J.C. Evaluating cell viability, capillary perfusion, and collateral tortuosity in an ex vivo mouse intestine fluidics model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1008481. [CrossRef]

- Chappell, J.C.; Song, J.; Klibanov, A.L.; Price, R.J. Ultrasonic microbubble destruction stimulates therapeutic arteriogenesis via the CD18-dependent recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1117-1122. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Munn, L.L. Fluid forces control endothelial sprouting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011, 108, 15342-15347. [CrossRef]

- Subramanyan, R.; Narayan, R.; Maskeri, S.A. Familial arterial tortuosity syndrome. Indian. Heart. J. 2007, 59, 178-180.

- Valeanu, L.; Bubenek-Turconi, S.I.; Ginghina, C.; Balan, C. Hemodynamic Monitoring in Sepsis-A Conceptual Framework of Macro- and Microcirculatory Alterations. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11, 1559. [CrossRef]

- Rovas, A.; Sackarnd, J.; Rossaint, J.; Kampmeier, S.; Pavenstädt, H.; Vink, H.; Kümpers, P. Identification of novel sublingual parameters to analyze and diagnose microvascular dysfunction in sepsis: the NOSTRADAMUS study. Crit. Care. 2021, 25, 112. [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Mori, N.; Mugikura, S.; Ohta, M.; Anzai, H. The influence of blood velocity and vessel geometric parameters on wall shear stress. Med. Eng. Phys. 2024, 124, 104112. [CrossRef]

- Kahe, F.; Sharfaei, S.; Pitliya, A.; Jafarizade, M.; Seifirad, S.; Habibi, S.; Chi, G. Coronary artery tortuosity: a narrative review. Coron. Artery. Dis. 2020, 31, 187-192. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.D.; Jaffa, A.J.; Timor, I.E.; Elad, D. Hemodynamic analysis of arterial blood flow in the coiled umbilical cord. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 258-268. [CrossRef]

- Wood, N.B.; Zhao, S.Z.; Zambanini, A.; Jackson, M.; Gedroyc, W.; Thom, S.A.; Hughes, A.D.; Xu, X.Y. Curvature and tortuosity of the superficial femoral artery: a possible risk factor for peripheral arterial disease. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 1412-1418. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, A.K.; Guo, X.L.; Wu, S.G.; Zeng, Y.J.; Xu, X.H. Numerical study of nonlinear pulsatile flow in S-shaped curved arteries. Med. Eng. Phys. 2004, 26, 545-552. [CrossRef]

- Datir, P.; Lee, A.Y.; Lamm, S.D.; Han, H.C. Effects of geometric variations on the buckling of arteries. Int. J. Appl. Mech. 2011, 3, 385-406. [CrossRef]

- Lupu, F.; Kinasewitz, G.; Dormer, K. The role of endothelial shear stress on haemodynamics, inflammation, coagulation and glycocalyx during sepsis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 12258-12271. [CrossRef]

- Pereira Duque Estrada, A.; de Oliveira Lopes, R.; Villacorta Junior, H. Coronary tortuosity and its role in myocardial ischemia in patients with no coronary obstructions. International. Journal. of. Cardiovascular. Sciences. 2017, 30, 163-170. [CrossRef]

- Chalkias, A. Shear Stress and Endothelial Mechanotransduction in Trauma Patients with Hemorrhagic Shock: Hidden Coagulopathy Pathways and Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17522. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, R.M.; Jagger, J.E.; Sharpe, M.D.; Ellsworth, M.L.; Mehta, S.; Ellis, C.G. Erythrocyte deformability is a nitric oxide-mediated factor in decreased capillary density during sepsis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2001, 280, H2848-2856. [CrossRef]

- Condon, M.R.; Kim, J.E.; Deitch, E.A.; Machiedo, G.W.; Spolarics, Z. Appearance of an erythrocyte population with decreased deformability and hemoglobin content following sepsis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2003, 284, H2177-2184. [CrossRef]

- Eichelbrönner, O.; Sielenkämper, A.; Cepinskas, G.; Sibbald, W.J.; Chin-Yee, I.H. Endotoxin promotes adhesion of human erythrocytes to human vascular endothelial cells under conditions of flow. Crit. Care. Med. 2000, 28, 1865-1870. [CrossRef]

- Keeley, T.P.; Mann, G.E. Defining Physiological Normoxia for Improved Translation of Cell Physiology to Animal Models and Humans. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 161-234. [CrossRef]

- Schödel, J.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Mechanisms of hypoxia signalling: New implications for nephrology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 641-659. [CrossRef]

- Milstein, D.M.; Helmers, R.; Hackmann, S.; Belterman, C.N.; van Hulst, R.A.; de Lange, J. Sublingual microvascular perfusion is altered during normobaric and hyperbaric hyperoxia. Microvasc. Res. 2016, 105, 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Schwarte, L.A.; Schober, P.; Loer, S.A. Benefits and harms of increased inspiratory oxygen concentrations. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 32, 783-791. [CrossRef]

- Orbegozo Cortés, D.; Puflea, F.; Donadello, K.; Taccone, F.S.; Gottin, L.; Creteur, J.; Vincent, J.L.; De Backer, D. Normobaric hyperoxia alters the microcirculation in healthy volunteers. Microvasc. Res. 2015, 98, 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Katritsis, D.; Kaiktsis, L.; Chaniotis, A.; Pantos, J.; Efstathopoulos, E.P.; Marmarelis, V. Wall shear stress: theoretical considerations and methods of measurement. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2007, 49, 307-329. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).