Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

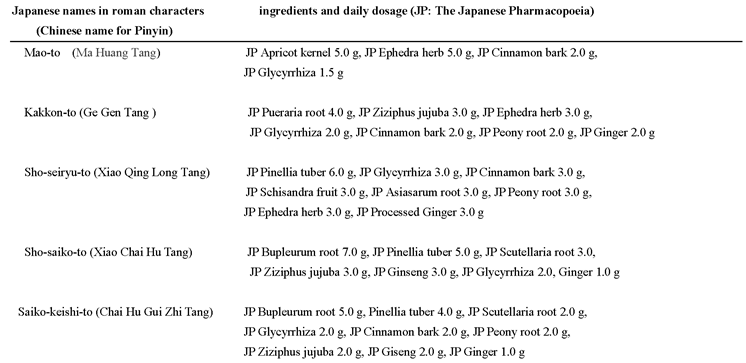

The main classes of antiviral drugs used to treat influenza are M2 inhibitors (e.g., amantadine), neuraminidase inhibitors (e.g., oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir), and cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitors (e.g., baloxavir marboxil). Amantadine, a pioneering antiviral drug, was globally used for treating influenza. However, influenza A viruses have developed resistance to amantadine. Neuraminidase inhibitors are also at a risk of developing resistance. Combination treatments including these drugs have been successfully administered as new therapeutic approaches for addressing the issue of resistance. Kampo medicine, which is based on traditional Chinese medicine, is traditional Japanese medicine with unique theories and therapeutic methods. Kampo medicines including Mao-to, Kakkon-to, Sho-seiryu-to, Sho-saiko-to, and Saiko-keishi-to have been empirically used for treating influenza. Kampo medicines are mainly composed of organic plant-based ingredients. The ingredients used to make Kampo medicine include Ephedra herb, Ziziphus jujuba, Glycyrrhiza, Bupleurum root, and others, the extracts of which have demonstrated anti-influenza and/or anti-inflammatory activities. Recently, minocycline, a tetracycline, was also observed to exert anti-influenza virus activities. Multidrug treatment is more effective compared with single-drug treatment because of the synergistic effects of the different mechanisms of actions of the drugs involved. Therefore, we propose the combination of Kampo medicine and minocycline for treating influenza as an alternative to the above-mentioned conventional drugs and hope that this might resolve the issue of conventional drug-resistant influenza.

Keywords:

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang J, Shen B, Yue L, Xu H, Chen L, Qian D, Dong W, Hu Y. The Global Trend of Drug Resistant Sites in Influenza A Virus Neuraminidase Protein from 2011 to 2020. Microorganisms. 2024 Oct 12;12(10):2056. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen JT, Hoopes JD, Smee DF, Prichard MN, Driebe EM, Engelthaler DM, Le MH, Keim PS, Spence RP, Went GT 2009. Triple Combination of Oseltamivir, Amantadine, and Ribavirin Displays Synergistic Activity against Multiple Influenza Virus Strains In Vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53. [CrossRef]

- Smee DF, Wong M, Bailey KW, Tarbed EB, Morrey JD, Furuta. 2010. Effect of the Combination of Favipiravir (T-705) and Oseltamivir on Influenza A Virus Infections in Mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54. [CrossRef]

- Yuan C, Guan Y. Efficacy and safety of Lianhua Qingwen as an adjuvant treatment for influenza in Chinese patients: A meta-analysis. Medicine. 2024 Jan 19;103(3):e36986.

- Naito T. Common Cold and Influenza. Juntendo Med. 2012 Oct 31;58(5):397-402.

- Watanabe K. Drug-Repositioning Approach for the Discovery of Anti-Influenza Virus Activity of Japanese Herbal (Kampo) Medicines In Vitro: Potent High Activity of Daio-Kanzo-To. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;2018(1):6058181.

- Yaegashi H. Efficacy of Co-administration of Maoto and Shosaikoto, a Japanese traditional herbal medicine (Kampo medicine), for the treatment of influenza A infection, in comparison to oseltamivir. Jpn J Complement Altern Med. 2010;1:59-62.

- Wei W, Du H, Shao C, Zhou H, Lu Y, Yu L, Wan H, He Y. Screening of antiviral components of Ma Huang Tang and investigation on the ephedra alkaloids efficacy on influenza virus type A. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2019 Sep 10;10:961.

- Wei X, Lan Y, Nong Z, Li C, Feng Z, Mei X, Zhai Y, Zou M. Ursolic acid represses influenza A virus-triggered inflammation and oxidative stress in A549 cells by modulating the miR-34c-5p/TLR5 axis. Cytokine. 2022 Sep 1;157:155947.

- Hong EH, Song JH, Kang KB, Sung SH, Ko HJ, Yang H. Anti-influenza activity of betulinic acid from Zizyphus jujuba on influenza A/PR/8 virus. Biomolecules & therapeutics. 2015 Jul;23(4):345.

- Wolkerstorfer A, Kurz H, Bachhofner N, Szolar OH. Glycyrrhizin inhibits influenza A virus uptake into the cell. Antiviral research. 2009 Aug 1;83(2):171-8.

- Michaelis M, Geiler J, Naczk P, Sithisarn P, Leutz A, Doerr HW, Cinatl Jr J. Glycyrrhizin exerts antioxidative effects in H5N1 influenza A virus-infected cells and inhibits virus replication and pro-inflammatory gene expression. PloS one. 2011 May 17;6(5):e19705.

- Kim S, Kim Y, Kim JW, Hwang YB, Kim SH, Jang YH. Antiviral Activity of Plant-derived Natural Products against Influenza Viruses. Journal of Life Science. 2022;32(5):375-90.

- Nimmerjahn F, Dudziak D, Dirmeier U, Hobom G, Riedel A, Schlee M, Staudt LM, Rosenwald A, Behrends U, Bornkamm GW, Mautner J. Active NF-kappaB signalling is a prerequisite for influenza virus infection. J Gen Virol. 2004 Aug;85(Pt 8):2347-2356. [CrossRef]

- Seong RK, Kim JA, Shin OS. Wogonin, a flavonoid isolated from Scutellaria baicalensis, has anti-viral activities against influenza infection via modulation of AMPK pathways. Acta Virol. 2018 Jan 1;62(1):78-85.

- Yoo DG, Kim MC, Park MK, Song JM, Quan FS, Park KM, Cho YK, Kang SM. Protective effect of Korean red ginseng extract on the infections by H1N1 and H3N2 influenza viruses in mice. Journal of medicinal food. 2012 Oct 1;15(10):855-62.

- Li J, Yang X, Huang L. Anti-Influenza virus activity and constituents characterization of Paeonia delavayi extracts. Molecules. 2016 Aug 26;21(9):1133.

- Saha P, Saha R, Datta Chaudhuri R, Sarkar R, Sarkar M, Koley H, Chawla-Sarkar M. Unveiling the Antiviral Potential of Minocycline: Modulation of Nuclear Export of Viral Ribonuclear Proteins during Influenza Virus Infection. Viruses. 2024 Aug 18;16(8):1317.

- Ohe M, Shida H, Yamamoto J, Seki M, Furuya K, Nishio S. COVID-19 Treated with Minocycline and Saiko-keishi-to: A Case Report. Intern Med J. 2024 Feb 1; 31(1).

- Ohe M, Shida H, Yamamoto J, Seki M, Furuya K. Successful treatment with minocycline and Saiko-keishi-to for COVID-19. J CLIN EXP INVEST. 2023; 14(2): em00815. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).