Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

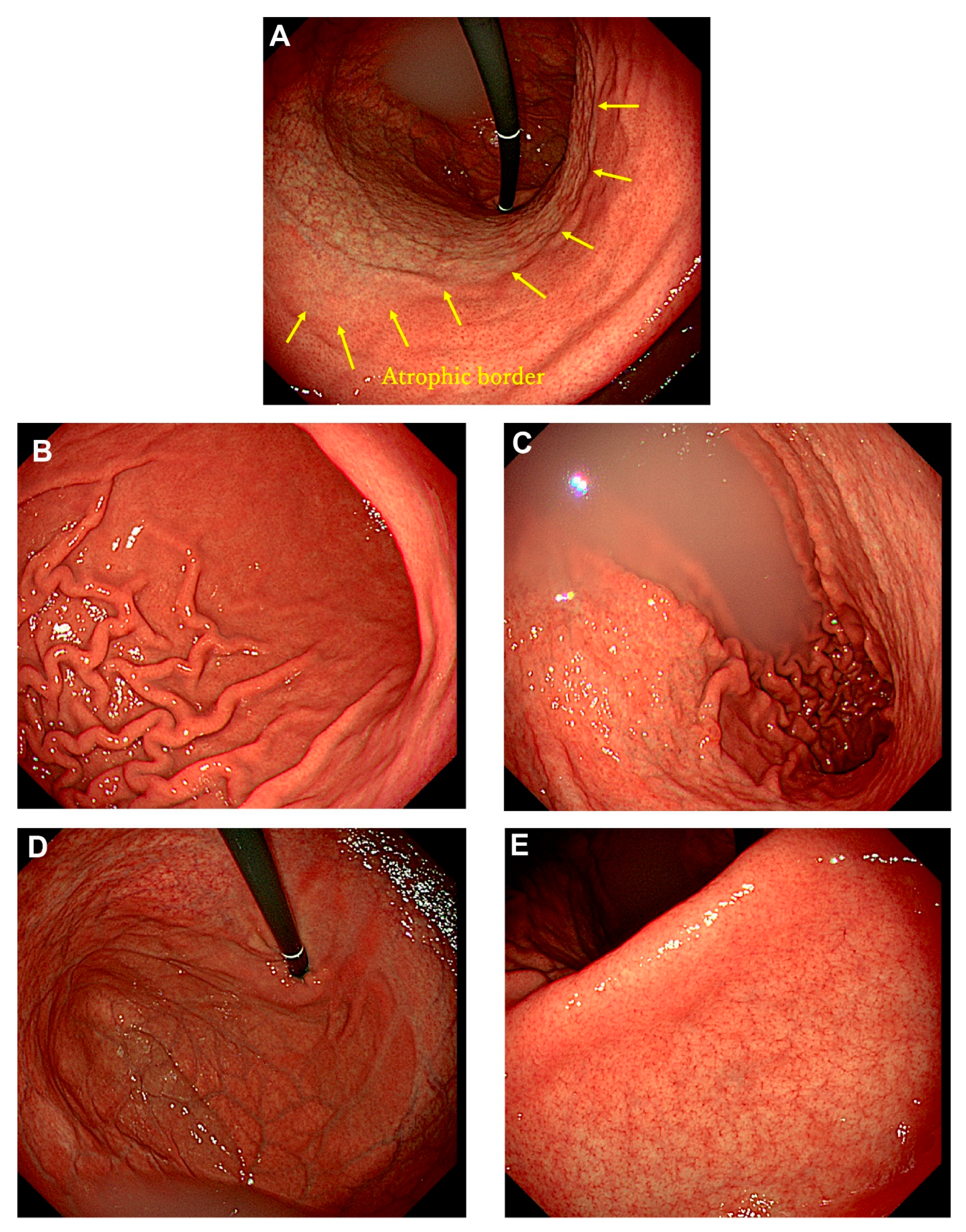

Autoimmune gastritis, traditionally called type A gastritis, is characterized by cor-pus-predominant atrophic gastritis caused by autoimmune mechanisms. Most cases are diagnosed in middle-aged or elderly individuals, as complications such as pernicious anemia and impaired absorption of iron and vitamin B12 typically manifest in advanced stages. Additionally, patients with autoimmune gastritis are often asymptomatic, making reports of early-stage endoscopic findings exceedingly rare. A 22-year-old male presented to our hospital with complaints of epigastric pain and lower back pain. He had undergone eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection at another hospital three months prior to presentation. A urea breath test confirmed the successful eradication of H. pylori. Endoscopic examination revealed extensive, sharply demarcated mucosal atrophy extending orally from the middle of the gastric body, while the gastric antrum showed no evidence of atrophy or intestinal metaplasia. Laboratory tests revealed a mild elevation of anti-parietal cell antibody levels by a factor of 10 (reference range: 0–9), whereas serum gastrin and vitamin B12 levels remained within normal limits. Iron metabolism parameters were also normal. This report presents a rare case of early-stage autoimmune gastritis with distinctive endoscopic findings in a young male.

Keywords:

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strickland, R. G.; Mackay, I. R., A reappraisal of the nature and significance of chronic atrophic gastritis. Am J Dig Dis 1973; 18(5): 426-40. [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. N.; Appelman, H. D., Autoimmune Gastritis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019; 143(11): 1327-1331. [CrossRef]

- Kamada, T.; Watanabe, H.; Furuta, T.; Terao, S.; Maruyama, Y.; Kawachi, H.; Kushima, R.; Chiba, T.; Haruma, K., Diagnostic criteria and endoscopic and histological findings of autoimmune gastritis in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2023; 58(3): 185-195. [CrossRef]

- Ayaki, M.; Aoki, R.; Matsunaga, T.; Manabe, N.; Fujita, M.; Kamada, T.; Kobara, H.; Masaki, T.; Haruma, K., Endoscopic and Upper Gastrointestinal Barium X-ray Radiography Images of Early-stage Autoimmune Gastritis: A Report of Two Cases. Intern Med 2021; 60(11): 1691-1696. [CrossRef]

- Kishino, M.; Nonaka, K., Endoscopic Features of Autoimmune Gastritis: Focus on Typical Images and Early Images. J Clin Med 2022; 11(12). [CrossRef]

- Kotera, T.; Ayaki, M.; Sumi, N.; Aoki, R.; Mabe, K.; Inoue, K.; Manabe, N.; Kamada, T.; Kushima, R.; Haruma, K., Characteristic endoscopic findings in early-stage autoimmune gastritis. Endosc Int Open 2024; 12(3): E332-E338. [CrossRef]

- Yagi, K.; Aruga, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Sekine, A., Regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC): a characteristic endoscopic feature of Helicobacter pylori-negative normal stomach and its relationship with esophago-gastric adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2005; 40(5): 443-52. [CrossRef]

- Lenti, M. V.; Miceli, E.; Vanoli, A.; Klersy, C.; Corazza, G. R.; Di Sabatino, A., Time course and risk factors of evolution from potential to overt autoimmune gastritis. Dig Liver Dis 2022; 54(5): 642-644. [CrossRef]

- Krzewska, A.; Ben-Skowronek, I., Effect of Associated Autoimmune Diseases on Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Incidence and Metabolic Control in Children and Adolescents. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 6219730. [CrossRef]

- Mitsinikos, T.; Shillingford, N.; Cynamon, H.; Bhardwaj, V., Autoimmune Gastritis in Pediatrics: A Review of 3 Cases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2020; 70(2): 252-257. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, C.; Otani, K.; Tamoto, M.; Yoshida, H.; Nadatani, Y.; Ominami, M.; Fukunaga, S.; Hosomi, S.; Kamata, N.; Tanaka, F., et al., Efficacy evaluation of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy screening for secondary prevention of gastric cancer using the standardized detection ratio during a medical check-up in Japan. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2024; 74(3): 253-260. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Y.; Forman, D.; Waskito, L. A.; Yamaoka, Y.; Crabtree, J. E., Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and CagA-Positive Infections and Global Variations in Gastric Cancer. Toxins (Basel) 2018; 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Kotera, T.; Yoshioka, U.; Takemoto, T.; Kushima, R.; Haruma, K., Evolving Autoimmune Gastritis Initially Hidden by Active Helicobacter pylori Gastritis. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2022; 16(1): 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Iwata, E.; Sugimoto, M.; Akimoto, Y.; Hamada, M.; Niikura, R.; Nagata, N.; Yanagisawa, K.; Itoi, T.; Kawai, T., Long-term endoscopic gastric mucosal changes up to 20 years after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Sci Rep 2024; 14(1): 13003. [CrossRef]

- Ihara, T.; Ihara, N.; Kushima, R.; Haruma, K., Rapid Progression of Autoimmune Gastritis after Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy. Intern Med 2023; 62(11): 1603-1609. [CrossRef]

- Furuta, T.; Baba, S.; Yamade, M.; Uotani, T.; Kagami, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tani, S.; Hamaya, Y.; Iwaizumi, M.; Osawa, S., et al., High incidence of autoimmune gastritis in patients misdiagnosed with two or more failures of H. pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48(3): 370-377. [CrossRef]

- Ihara, T.; Kushima, R.; Haruma, K., Enhanced activity of autoimmune gastritis following Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Clin J Gastroenterol 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sumi, N.; Haruma, K.; Inoue, K.; Hisamoto, N.; Mabe, K.; Sasai, T.; Ichiba, T.; Ayaki, M.; Manabe, N.; Takao, T., A case of nodular gastritis progression to autoimmune gastritis after 10 years of Helicobacter pylori eradication. Clin J Gastroenterol 2024; 17(2): 216-221. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).