1. Introduction

Aminoglycosides are broad-spectrum antibiotics that, alone or in combination with other types, are used to treat numerous infections, many of them life-threatening, caused by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial pathogens [

1,

2]. Although there was a period when the use of these antimicrobials diminished in favor of other classes with lower toxicity, increased multidrug resistance has renewed interest in aminoglycosides [

3]. In particular, amikacin, a semisynthetic derivative of kanamycin A, has been successfully used in multiple treatments due to its refractory nature to most aminoglycoside modifying enzymes [

4]. Unfortunately, amikacin is not resistant to the action of aminoglycoside 6′-

N-acetyltransferases type I [AAC(6′)-I], which cause resistance in many bacteria [

5]. Of these enzymes, AAC(6′)-Ib is the most often found in Gram-negative clinical strains [

6]. The

aac(6′)-Ib gene is found in many mobile genetic environments, making it highly mobile and capable of residing in plasmids of different classes and chromosomes [

7]. Its ubiquity within Gram-negative pathogens drove efforts to develop compounds that interfere with the acetylating reactions or the enzyme’s expression [

1,

8,

9]. Recent advances in understanding the resistance mediated by AAC(6′)-Ib indicate that, at least in those cases where the gene is located in high copy number plasmids, the number of molecules synthesized is much higher than needed to achieve clinical resistance [

10]. It is, therefore, critical that compounds designed or identified to reduce resistance to susceptibility levels have potent inhibitory activity.

Recent research showed that divalent cations, in combination with ionophores or the monovalent Ag

+1, interfere with the AAC(6′)-Ib-mediated enzymatic inactivation by a mechanism still unknown. These findings expanded the possibilities of finding adjuvant inhibitors that, in combination with amikacin, can successfully treat resistant infections [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This article describes the inhibition of AAC(6′)-Ib-mediated amikacin resistance by Cd

2+ in combination with sodium pyrithione (NaPT).

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Cd2+ on AAC(6′)-Ib-Mediated Acetylation of Amikacin

The finding that some divalent cations act as inhibitors of AAC(

6′)-Ib-catalyzed acetylation of aminoglycosides prompted us to test other metal ions. We found that Cd

2+ reduced the acetylation of aminoglycosides by AAC(

6′)-Ib (

Table 1). Mg

2+, which, along with other cations, was shown not to interfere with or enhance enzymatic acetylation [

14], was included in the assay as negative control.

2.2. Effect of Cd2+ and Pyrithione on Amikacin-Resistant Bacteria Harboring aac(6′)-Ib

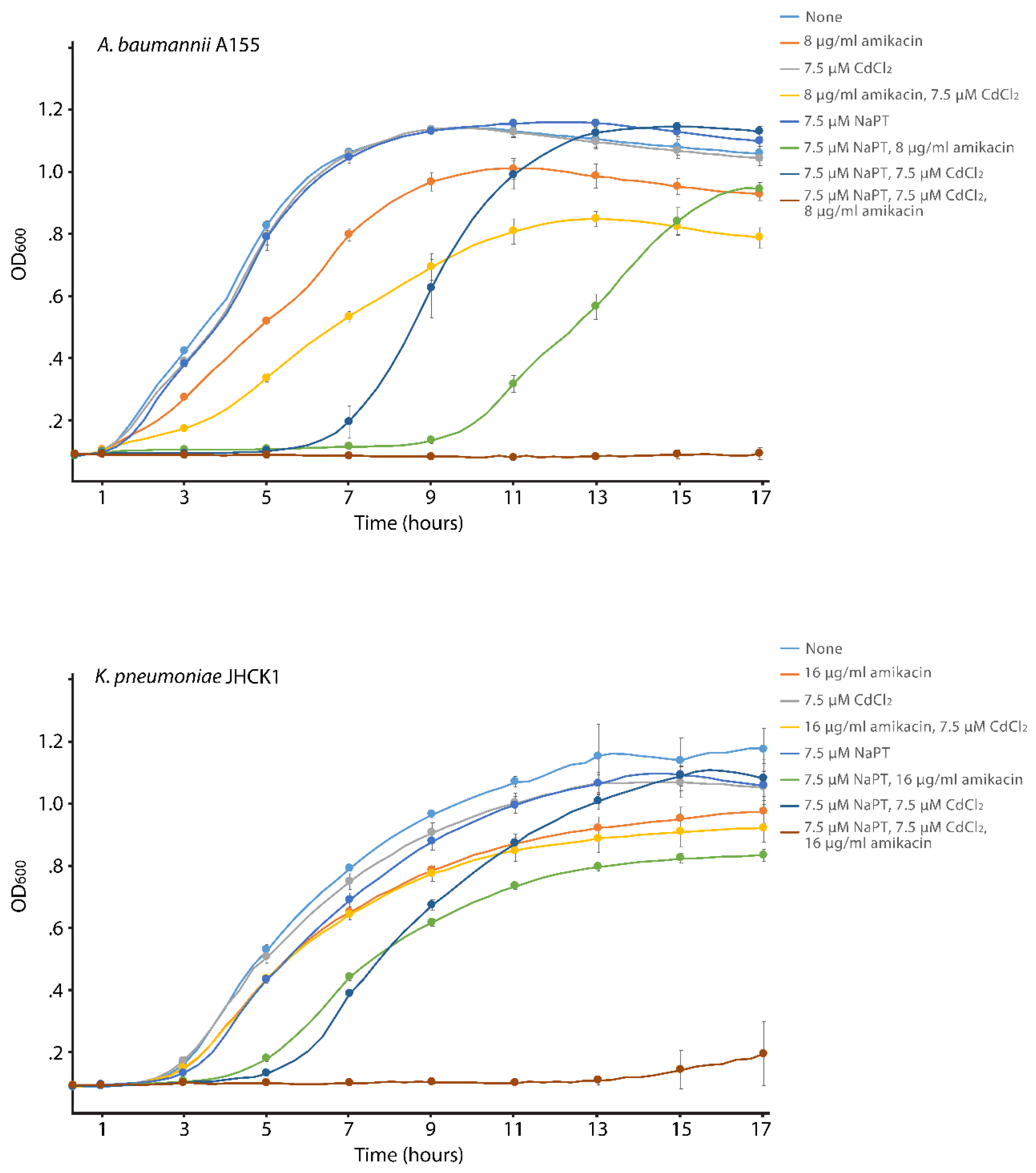

We carried out cultures with different supplements to determine if the effect of Cd

2+ on the enzymatic reaction catalyzed by AAC(

6′)-Ib reduces resistance in bacterial cells growing in broth. The assays were carried out using K. pneumoniae JHCK1 and A. baumannii A155. Both clinical strains naturally harbor aac(6′)-Ib, the latter within the chromosome and the former in a plasmid, pJHCMW1, whose copy number is ~25, when measured in E. coli [

19].

Figure 1 shows that amikacin has minimal effect on the growth of both strains, and addition of CdCl

2 only marginally enhanced the action of amikacin. On the other hand, when the growth medium was supplemented with amikacin, CdCl

2, and NaPT, growth was completely abolished. Inspection of the A. baumannii A155 growth curves indicates that NaPT influences growth, but it is mainly limited to the extension of the lag phase and not the final cell density after 17 h incubation. The same but significantly reduced effect can be seen in the K. pneumoniae JHCK1 growth curves when NaPT is present. Extension of the lag phase in the presence of PT on various bacteria has been documented before [

20]. The results described in this section show that 7.5 μM Cd

2+ in the presence of the ionophore pyrithione reverses the chromosome- and plasmid-mediated resistance to amikacin in A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae clinical strains.

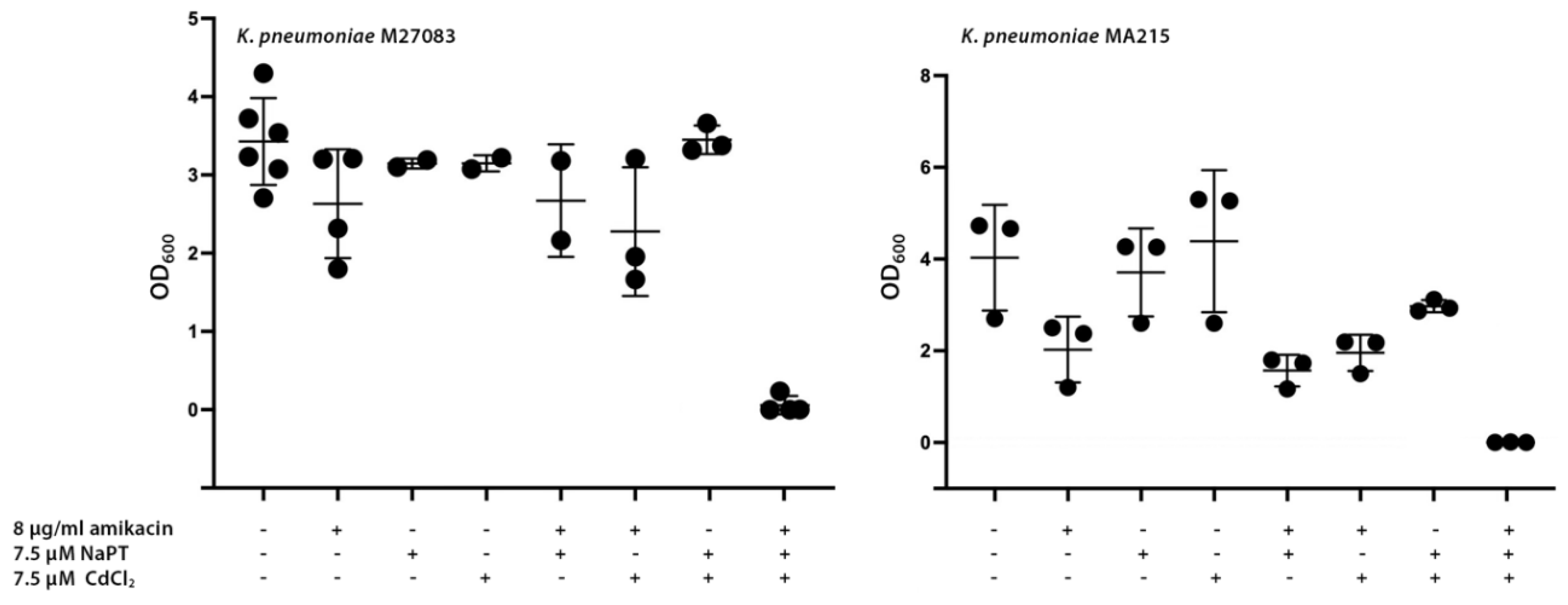

2.3. Effect of Cd2+ and Pyrithione with aac(6′)-Ib-Mediated Resistance to Amikacin in Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Harboring Carbapenemases

Among the various types of β-lactam antibiotics, carbapenems have the broadest spectrum and greatest potency against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. These characteristics make carbapenems a crucial tool in combating life-threatening, multiresistant infections. Consequently, they are reserved as last-resort treatment options when other therapies have failed [

21]. Unfortunately, the rise of several carbapenemases threatens our ability to treat many infections, leading to increased morbidity and mortality [

22]. Carbapenemases are rapidly spreading among Enterobacterales, exacerbating the already severe problem of multidrug-resistant nosocomial infections [

22]. A significant example of this crisis is the emergence of carbapenem-resistant

K. pneumoniae (CRKP) strains, which have such a high impact that they have been placed at the top of the World Health Organization’s priority list [

23,

24]. We selected two CRKP strains, M27083 and MA215, resistant to amikacin and harboring the

aac(6′)-Ib gene to determine if the combination of Cd

2+ and pyrithione induces phenotypic conversion to susceptibility.

Figure 2 shows that addition of amikacin did not preclude significant growth, although strain MA215 showed slightly lower amikacin resistance levels than strain M27083. In both cases, adding Cd

2+ or NaPT to the cultures containing amikacin did not affect growth. However, when both compounds were present, growth was completely abolished, suggesting that the formation of the complex between Cd

2+ and PT facilitated the internalization of the cation, allowing inhibition of acetylation at levels sufficient to observe conversion to susceptibility at the amikacin concentration utilized. Supplementing the medium with Cd

2+, NaPT, or both compounds, without adding amikacin, resulted in heavy bacterial growth.

3. Discussion

The ongoing antibiotic resistance crisis ranks among modern medicine’s most significant challenges [

23,

25]. Unfortunately, the optimistic view that we were on the verge of defeating bacterial infections, prevalent decades ago, never crystallized. The current rise and dissemination of multidrug-resistant pathogens threaten to undermine much of the progress made in treating infectious diseases. In the past, a robust pipeline of new antibiotics ensured that when resistance to existing drugs became critical, there was always a new one to control infections. However, a combination of scientific challenges and economic considerations has slowed the pace of discovery of new antimicrobials, allowing rapidly evolving bacteria to outpace our efforts [

26]. Some bacteria now resist most or all available antibiotics, creating a dangerous gap in medicine’s ability to combat life-threatening infections. It is, therefore, imperative to complement antibiotic discovery with innovative approaches such as alternative therapeutic strategies, repurposing of existing compounds, or agents that can overcome resistance to antibiotics currently in use [

23].

Aminoglycoside antibiotics, alone or in combination with other antimicrobials, are effective in treating numerous infections caused by Gram-negative aerobic bacilli, staphylococci, and other Gram-positives [

6]. The most common mechanism of resistance to aminoglycosides is their enzymatic modification [

6]. To date, more than one hundred aminoglycoside modifying enzymes have been described. Among them, AAC(6′)-Ib stands out for its ubiquity among Gram-negative pathogens and its effectiveness in conferring resistance to numerous aminoglycosides. AAC(6′)-Ib is the most prevalent enzyme that causes resistance to the semisynthetic aminoglycoside amikacin [

7]. This antibiotic has been instrumental in controlling numerous otherwise multidrug-resistant infections. Finding strategies to overcome resistance mediated by AAC(6′)-Ib would extend the effective lifespan of amikacin and permit its continued use. A promising and recent finding in the quest for alternatives to overcome the action of AAC(6′)-Ib is the ability of some cations to interfere with the acetylation reaction. Cations with inhibitory properties include Zn

2+, Cu

2+, and Ag

1+; the divalent ones are active in growing bacterial cells when combined with an ionophore such as pyrithione [

12,

13,

14,

17]. The quest for improvement and refinement of methods that can overcome amikacin resistance resulted in the identification of Cd

2+ as another cation that interferes with inactivation by enzymatic acetylation. The results presented in this article demonstrate that, in addition to its in vitro activity, low μM concentrations of Cd

2+ complexed to pyrithione completely stopped growth of AAC(6′)-Ib-harboring

A. baumannii and

K. pneumoniae clinical isolates. Furthermore, the growth of two CRKP strains was controlled by amikacin in the presence of pyrithione and Cd

2+. This work adds to the battery of potential inhibitors of inactivation of amikacin that can be developed, alone or combined with other inhibitors, as adjuvants to be administered along with amikacin to treat the most severe multidrug resistant infections. While the mechanism by which cations inhibit acetylation remains to be elucidated, an attractive hypothesis is that the cation titrates the substrate aminoglycoside by forming coordination complexes. This process has been described to occur between aminoglycosides and several metal ions [

27].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains

A. baumannii A155 was isolated from a urinary sample. It is a multidrug resistant strain belonging to the clonal complex 109 [

28].

K. pneumoniae JHCK1 is a multidrug resistant strain isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of a neonate [

29].

K. pneumoniae M27083 is a multidrug resistant strain that harbors two carbapenemase-coding genes,

blaNDM-1 and

blaKPC-2 [

30]. It was isolated from mini-bronchoalveolar lavage (mini-BAL) carried out on a male patient with COVID-19.

K. pneumoniae MA215 is a multidrug resistant strain that includes

blaKPC-162, isolated from a rectal screening of a female patient [

31]. All four strains were isolated in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and harbor

aac(6′)-Ib.

4.2. Acetyltransferase Assays

Acetyltransferase activity was assessed using the phosphocellulose paper binding assay [

32], as previously described [

33,

34]. Briefly, 120 μg of protein from a soluble extract obtained from sonically disrupted

E. coli TOP10(pJHCMW1) cells were added to a reaction mixture containing 200 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4 buffer, 167 μM antibiotic, 1 mM cadmium or magnesium chloride, and 0.03 μCi of [acetyl-1-

14C]-acetyl-coenzyme A (specific activity 60 μCi/μmol) in a final volume of 30 μl. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 20 minutes, and 20 μl were spotted on phosphocellulose paper strips. The unreacted radioactive substrate was washed once by submersion in 80 °C water, followed by three washes with room temperature water. After drying, the radioactivity corresponding to the acetylated antibiotic was determined.

4.3. Growth Inhibition Assays

Bacteria were routinely cultured in Lennox L broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl), and 2% agar was added in the case of solid medium. Inhibition of bacterial growth was determined in Mueller-Hinton broth at 37°C with shaking in microtiter plates. The OD

600 of the cultures containing the specified additions was determined every two hours for 17 h incubation at 37°C using the BioTek Synergy 2 microplate reader as described before [

14]. In the case of the assays using the CRKP, the OD

600 was measured after 20 h. Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (P < 0.05). The analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

Only inhibitors of β-lactamases have reached the market to be used in combination with β-lactams [

35]. The success in extending these antibiotics’ usability demonstrates the strategy’s viability. Unfortunately, no resistance inhibitors for other antibiotic classes have been successfully developed. On the other hand, the recent discovery that various cations inhibit the resistance mediated by AAC(6′)-Ib is encouraging and offers a potential path for the continued use of amikacin and other aminoglycosides for hard-to-treat multidrug-resistant infections. The results described in this article expand the armamentarium of cations that can be developed into adjuvants to amikacin and other aminoglycosides.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.J.M., D.N., and M.E.T.; methodology, A.J.M., D.N., T.T., V.J., M.S.R. and M.E.T.; formal analysis, A.J.M., V.J., M.S.R., and M.E.T.; investigation, A.J.M., D.N., K.B., O.A., J.S., T.T., C.D.M., V.J., M.S.R. and M.E.T.; resources, F.P., V.J., M.S.R., and M.E.T.; data curation, A.J.M., M.S.R., and M.E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.T.; writing—review and editing, A.J.M., V.J., M.S.R., M.E.T.; supervision, M.E.T.; funding acquisition, M.S.R. and M.E.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Public Health Service Grants 2R15AI047115 (M.E.T.) and SC3GM125556 (M.S.R.) from the National Institute of Health. T.T. and A.J.M. were partially supported by grant LA Basin Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Training Program (MHRT) T37MD001368 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAC(6′)-Ib |

aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib |

| CRKP |

carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae

|

References

- Lang, M.; Carvalho, A.; Baharoglu, Z.; Mazel, D. Aminoglycoside uptake, stress, and potentiation in Gram-negative bacteria: new therapies with old molecules. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2023, 87, e0003622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, K.M.; Serio, A.W.; Kane, T.R.; Connolly, L.E. Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottger, E.C.; Crich, D. Aminoglycosides: time for the resurrection of a neglected class of antibacterials? ACS Infect Dis 2020, 6, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Amikacin: uses, resistance, and prospects for inhibition. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmasky, M.E. Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes: characteristics, localization, and dissemination. In Enzyme-Mediated Resistance to Antibiotics: Mechanisms, Dissemination, and Prospects for Inhibition, Bonomo, R.A.; Tolmasky, M.E., Eds. ASM Press: Washington, DC, 2007; pp 35-52.

- Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat 2010, 13, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M.S.; Nikolaidis, N.; Tolmasky, M.E. Rise and dissemination of aminoglycoside resistance: the aac(6′)-Ib paradigm. Front Microbiol 2013, 4, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labby, K.J.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Strategies to overcome the action of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes for treating resistant bacterial infections. Future Med Chem 2013, 5, 1285–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmasky, M.E. Strategies to prolong the useful life of existing antibiotics and help overcoming the antibiotic resistance crisis In Frontiers in Clinical Drug Research-Anti Infectives, Atta-ur-Rhaman, Ed. Bentham Books: Sharjah, UAE, 2017; Vol. 1, pp 1-27.

- d’Acoz, O.D.; Hue, F.; Ye, T.; Wang, L.; Leroux, M.; Rajngewerc, L.; Tran, T.; Phan, K.; Ramirez, M.S.; Reisner, W.; et al. Dynamics and quantitative contribution of the aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib] to amikacin resistance. mSphere 2024.

- Chiem, K.; Fuentes, B.A.; Lin, D.L.; Tran, T.; Jackson, A.; Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Inhibition of aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib-mediated amikacin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae by zinc and copper pyrithione. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 5851–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiem, K.; Hue, F.; Magallon, J.; Tolmasky, M.E. Inhibition of aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib-mediated amikacin resistance by zinc complexed with clioquinol, an ionophore active against tumors and neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018, 51, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Green, K.D.; Johnson, B.R.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Inhibition of aminoglycoside acetyltransferase resistance enzymes by metal salts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 4148–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.L.; Tran, T.; Alam, J.Y.; Herron, S.R.; Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Inhibition of aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib by zinc: reversal of amikacin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli by a zinc ionophore. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 4238–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallon, J.; Chiem, K.; Tran, T.; Ramirez, M.S.; Jimenez, V.; Tolmasky, M.E. Restoration of susceptibility to amikacin by 8-hydroxyquinoline analogs complexed to zinc. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallon, J.; Vu, P.; Reeves, C.; Kwan, S.; Phan, K.; Oakley-Havens, C.; Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Amikacin in combination with zinc pyrithione prevents growth of a carbapenem-resistant/multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021, 58, 106442.

- Reeves, C.M.; Magallon, J.; Rocha, K.; Tran, T.; Phan, K.; Vu, P.; Yi, Y.; Oakley-Havens, C.L.; Cedano, J.; Jimenez, V.; et al. Aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase type Ib [AAC(6′)-Ib]-mediated aminoglycoside resistance: phenotypic conversion to susceptibility by silver ions. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, D.; Magana, A.J.; Tran, T.; Sklenicka, J.; Phan, K.; Eykholt, B.; Jimenez, V.; Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Inhibition of enzymatic acetylation-mediated resistance to plazomicin by silver ions. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Lamothe, R.; Tran, T.; Meas, D.; Lee, L.; Li, A.M.; Sherratt, D.J.; Tolmasky, M.E. High-copy bacterial plasmids diffuse in the nucleoid-free space, replicate stochastically and are randomly partitioned at cell division. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattar, M.M.; Salt, W.G.; Stretton, R.J. The influence of pyrithione on the growth of micro-organisms. J Appl Bacteriol 1988, 64, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Endimiani, A.; Taracila, M.A.; Bonomo, R.A. Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011, 55, 4943–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomo, R.A.; Burd, E.M.; Conly, J.; Limbago, B.M.; Poirel, L.; Segre, J.A.; Westblade, L.F. Carbapenemase-producing organisms: a global scourge. Clin Infect Dis 2018, 66, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

World-Health-Organization. WHO bacterial priority pathogens list, 2024: bacterial pathogens of public health importance to guide research, development and strategies to prevent and control antimicrobial resistance.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024.

- Chen, T.A.; Chuang, Y.T.; Lin, C.H. A decade-long review of the virulence, resistance, and epidemiological risks of Klebsiella pneumoniae in ICUs. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, H.W. Bad bugs, no drugs 2002-2020: progress, challenges, and call to action. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2020, 131, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brussow, H. The antibiotic resistance crisis and the development of new antibiotics. Microb Biotechnol 2024, 17, e14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozłowski, H.; Kowalik-Jankowska, T.; Jeżowska-Bojczuk, M. Chemical and biological aspects of Cu2+ interactions with peptides and aminoglycosides. Coord Chem Rev 2005, 249, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivett, B.A.; Fiester, S.E.; Ream, D.C.; Centron, D.; Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E.; Actis, L.A. Draft genome of the multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain A155 clinical isolate. Genome Announc 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M.S.; Xie, G.; Marshall, S.H.; Hujer, K.M.; Chain, P.S.; Bonomo, R.A.; Tolmasky, M.E. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates: a zone of high heterogeneity (HHZ) as a tool for epidemiological studies. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, E254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magana, A.J.; Ngo, D.; Faccone, D.; Gomez, S.; Corso, A.; Pasteran, F.; Ramirez, M.S.; Tolmasky, M.E. Amikacin, in combination with cations, prevents growth of a carbapenem-resistant/multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strain isolated from a patient with COVID-19. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2025, 40, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, S.; Martino, F.; Sanz, M.; Escalante, J.; Mendieta, J.; Lucero, C.; Ceriana, P.; Pasteran, F.; Corso, A.; Ramirez, M.S.; et al. Emerging resistance to novel beta-lactam beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations in Klebsiella pneumoniae bearing KPC variants. J Antimicrob Chemother 2025, submitted for publication.

- Haas, M.J.; Dowding, J.E. Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Methods Enzymol 1975, 43, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tolmasky, M.E.; Roberts, M.; Woloj, M.; Crosa, J.H. Molecular cloning of amikacin resistance determinants from a Klebsiella pneumoniae plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1986, 30, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woloj, M.; Tolmasky, M.E.; Roberts, M.C.; Crosa, J.H. Plasmid-encoded amikacin resistance in multiresistant strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from neonates with meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1986, 29, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojica, M.F.; Rossi, M.A.; Vila, A.J.; Bonomo, R.A. The urgent need for metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitors: an unattended global threat. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, e28–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).